User login

Mr. J, age 23, presents to an outpatient mental health clinic for treatment of anxiety. He has no psychiatric history, is dressed neatly, and recently finished graduate school with a degree in accounting. Mr. J is reserved during the initial psychiatric evaluation and provides only basic facts about his developmental history.

Mr. J comes from a middle-class household with no history of trauma or substance use. He does not report any symptoms consistent with anxiety, but discloses a history of sexual preoccupations. Mr. J says that during adolescence he developed a predilection for observing others engage in sexual activity. In his late teens, he began following couples to their homes in the hope of witnessing sexual intimacy. In the rare instance that his voyeuristic fantasy comes to fruition, he masturbates and achieves sexual gratification he is incapable of experiencing otherwise. Mr. J notes that he has not yet been caught, but he expresses concern and embarrassment related to his actions. He concludes by noting that he seeks help because the frequency of this behavior has steadily increased.

How would you treat Mr. J? Where does the line exist between a normophilic sexual interest, fantasy or urge, and a paraphilia? Does Mr. J qualify as a sexually violent predator?

From The Rocky Horror Picture Show to Fifty Shades of Grey, sensationalized portrayals of sexual deviancy have long been present in popular culture. The continued popularity of serial killers years after their crimes seems in part related to the extreme sexual torture their victims often endure. However, a sexual offense does not always qualify as a paraphilic disorder.1 In fact, many individuals with paraphilic disorders never engage in illegal activity. Additionally, experiencing sexually deviant thoughts alone does not qualify as a paraphilic disorder.1

A thorough psychiatric evaluation should include a discussion of the patient’s sexual history, including the potential of sexual dysfunction and abnormal desires or behaviors. Most individuals with sexual dysfunction do not have a paraphilic disorder.2 DSM-5 and ICD-11 classify sexual dysfunction and paraphilic disorders in different categories. However, previous editions grouped them together under sexual and gender identity disorders. Individuals with paraphilic disorders may not originally present to the outpatient setting for a paraphilic disorder, but instead may first seek treatment for a more common comorbid disorder, such as a mood disorder, personality disorder, or substance use disorder.3

Diagnostically speaking, if individuals do not experience distress or issues with functionality and lack legal charges (suggesting that they have not violated the rights of others), they are categorized as having an atypical sexual interest but do not necessarily meet the criteria for a disorder.4 This article provides an overview of paraphilic disorders as well as forensic considerations when examining individuals with sexually deviant behaviors.

Overview of paraphilic disorders

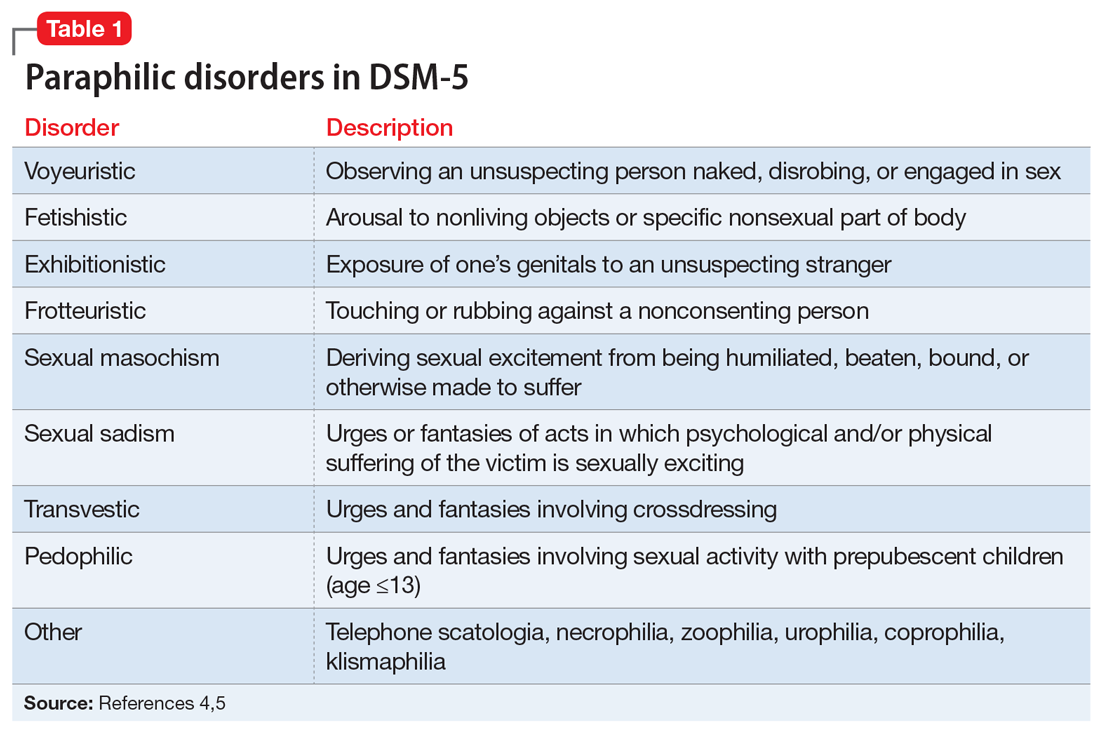

DSM-5 characterizes a paraphilic disorder as “recurrent, intense sexually arousing fantasies, sexual urges, or behaviors generally involving nonhuman objects or nonconsenting partners for at least 6 months. The individual must have acted on the thought and/or it caused clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning.” DSM-5 outlines 9 categories of paraphilic disorders, which are described in Table 1.4,5

Continue to: Paraphilic disorders are more common...

Paraphilic disorders are more common in men than in women; the 2 most prevalent are voyeuristic disorder and frotteuristic disorder.6 The incidence of paraphilias in the general outpatient setting varies by disorder. Approximately 45% of individuals with pedophilic disorder seek treatment, whereas only 1% of individuals with zoophilia seek treatment.6 The incidence of paraphilic acts also varies drastically; individuals with exhibitionistic disorder engaged in an average of 50 acts vs only 3 for individuals with sexual sadism.6 Not all individuals with paraphilic disorders commit crimes. Approximately 58% of sexual offenders meet the criteria for a paraphilic disorder, but antisocial personality disorder is a far more common diagnosis.7

Sexual psychopath statutes: Phase 1

In 1937, Michigan became the first state to enact sexual psychopath statutes, allowing for indeterminate sentencing and the civil commitment/treatment of sex offenders with repeated convictions. By the 1970s, more than 30 states had enacted similar statutes. It was not until 1967, in Specht v Patterson,8 that the United States Supreme Court unanimously ruled that the Fourteenth Amendment Due Process Clause was violated when Francis Eddie Specht faced life in prison following his conviction for indecent liberties under the Colorado Sex Offenders Act.

Specht was convicted in 1959 for indecent liberties after pleading guilty to enticing a child younger than age 16 into an office and engaging in sexual activities with them. At the time of Specht’s conviction, the crime of indecent liberties carried a punishment of 10 years. However, Specht was sentenced under the Sexual Offenders Act, which allowed for an indeterminate sentence of 1 day to life in prison. The Supreme Court noted that Specht was denied the right to be present with counsel, to confront the evidence against him, to cross-examine witnesses, and to offer his own evidence, which was a violation of his constitutionally guaranteed Fourteenth Amendment right to Procedural Due Process. The decision led most states to repeal early sexual psychopath statutes.8

Sexually violent predator laws: Phase 2

After early sexual psychopath statutes were repealed, many states pushed to update sex offender laws in response to the Earl Shriner case.9 In 1989, Shriner was released from prison after serving a 10-year sentence for sexually assaulting 2 teenage girls. At the time, he did not meet the criteria for civil commitment in the state of Washington. On the day he was released, Shriner cut off a young boy’s penis and left him to die. Washington subsequently became the first of many states to enact sexually violent predator (SVP) laws. Table 210 shows states and districts that have SVP civil commitment laws.

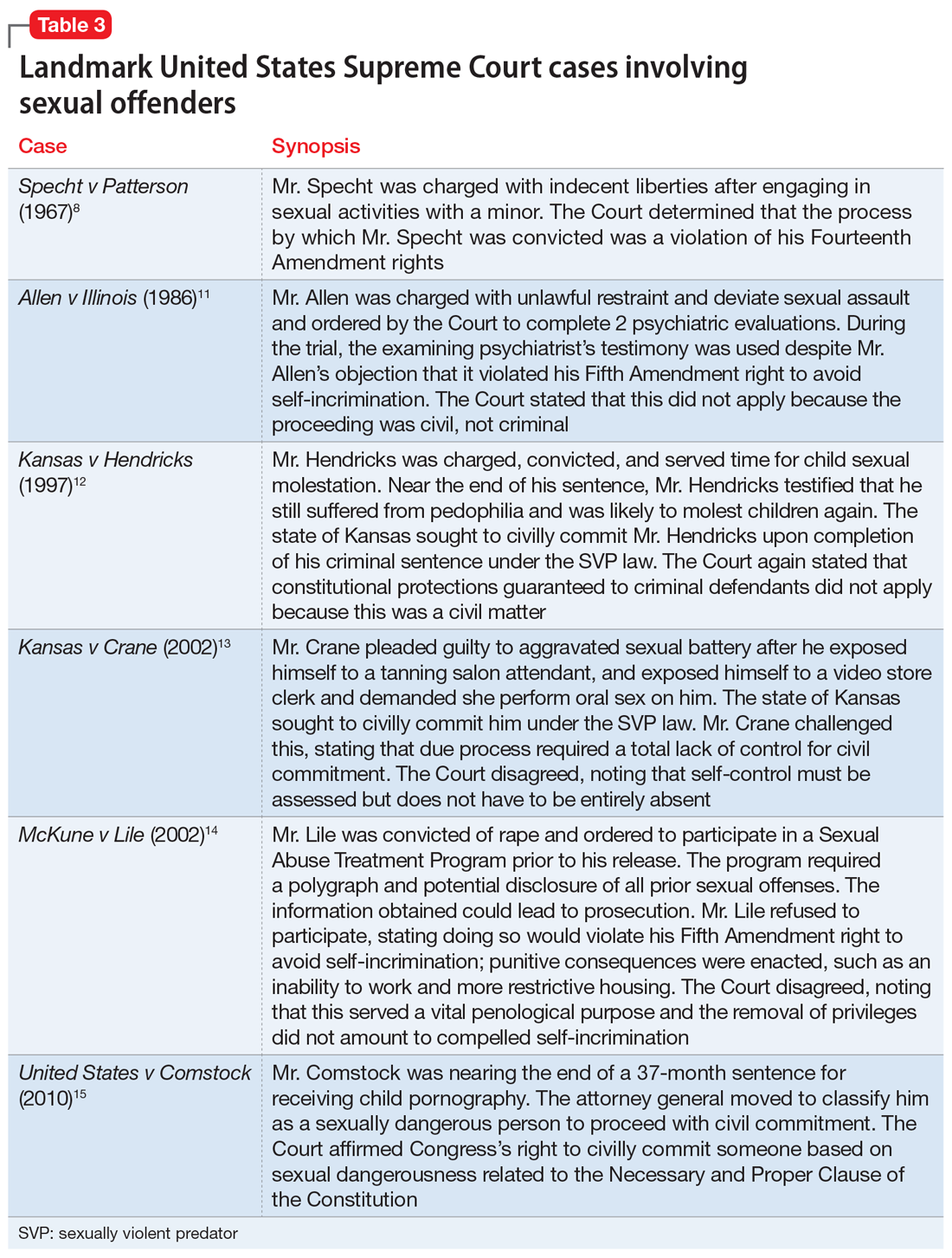

A series of United States Supreme Court cases solidified current sexual offender civil commitment laws (Table 38,11-15).

Continue to: Allen v Illinois

Allen v Illinois (1986).11 The Court ruled that forcing an individual to participate in a psychiatric evaluation prior to a sexually dangerous person’s commitment hearing did not violate the individual’s Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination because the purpose of the evaluation was to provide treatment, not punishment.

Kansas v Hendricks (1997).12 The Court upheld that the Kansas Sexually Violent Predator Act was constitutional and noted that the use of the broad term “mental abnormality” (in lieu of the more specific term “mental illness”) does not violate an individual’s Fourteenth Amendment right to substantive due process. Additionally, the Court opined that the constitutional ban on double jeopardy and ex post facto lawmaking does not apply because the procedures are civil, not criminal.

Kansas v Crane (2002).13 The Court upheld the Kansas Sexually Violent Predator Act, stating that mental illness and dangerousness are essential elements to meet the criteria for civil commitment. The Court added that proof of partial (not total) “volitional impairment” is all that is required to meet the threshold of sexual dangerousness.

McKune v Lile (2002).14 The Court ruled that a policy requiring participation in polygraph testing, which would lead to the disclosure of sexual crimes (even those that have not been prosecuted), does not violate an individual’s Fifth Amendment rights because it serves a vital penological purpose.

Adam Walsh Child Protection and Safety Act of 200616; United States v Comstock (2010).15 This act and subsequent case reinforced the federal government’s right to civilly commit sexually dangerous persons approaching the end of their prison sentences.

Continue to: What is requiried for civil commitment?

What is required for civil commitment?

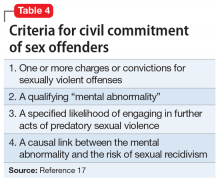

SVP laws require 4 conditions to be met for the civil commitment of sexual offenders (Table 417). In criteria 1, “charges” is a key word, because this allows individuals found Not Guilty by Reason of Insanity or Incompetent to Stand Trial to be civilly committed. Criteria 2 defines “mental abnormality” as a “congenital or acquired condition affecting the emotional or volitional capacity which predisposes the person to commit criminal sexual acts in a degree constituting such person a menace to the health and safety of others.”18 This is a broad definition, and allows individuals with personality disorders to be civilly committed (although most sexual offenders are committed for having a paraphilic disorder). To determine risk, various actuarial instruments are used to assess for sexually violent recidivism, including (but not limited to) the Static-99R, Sexual Violence Risk-20, and the Sex Offender Risk Appraisal Guide.19

Although the percentages vary, sex offenders rarely are civilly committed following their criminal sentence. In California, approximately 1.5% of sex offenders are civilly committed.17 The standard of proof for civil commitment varies by state between “clear and convincing evidence” and “beyond a reasonable doubt.” As sex offenders approach the end of their sentence, sexually violent offenders are identified to the general population and referred for a psychiatric evaluation. If the individual meets the 4 criteria for commitment (Table 417), their case is sent to the prosecuting attorney’s office. If accepted, the court holds a probable cause hearing, followed by a full trial.

Pornography and sex offenders

Pornography has long been considered a risk factor for sexual offending, and the role of pornography in influencing sexual behavior has drawn recent interest in research towards predicting future offenses. However, a 2019 systematic review by Mellor et al20 on the relationship between pornography and sexual offending suggested that early exposure to pornography is not a risk factor for sexual offending, nor is the risk of offending increased shortly after pornography exposure. Additionally, pornography use did not predict recidivism in low-risk sexual offenders, but did in high-risk offenders.

The use of child pornography presents a set of new risk factors. Prohibited by federal and state law, child pornography is defined under Section 2256 of Title 18, United States Code, as any visual depiction of sexually explicit conduct involving a minor (someone <age 18). Visual depictions include photographs, videos, digital or computer-generated images indistinguishable from an actual minor, and images created to depict a minor. The law does not require an image of a child engaging in sexual activity for the image to be characterized as child pornography. Offenders are also commonly charged with the distribution of child pornography. A conviction of child pornography possession carries a 15- to 30-year sentence, and distribution carries a 5- to 20-year sentence.21 The individual must also file for the sex offender registry, which may restrict their employment and place of residency.

It is unclear what percentage of individuals charged with child pornography have a history of prior sexual offenses. Numerous studies suggest there is a low risk of online offenders without prior offenses becoming contact offenders. Characteristics of online-only offenders include being White, a single male, age 20 to 30, well-educated, and employed, and having antisocial traits and a history of sexual deviancy.22 Contact offenders tend to be married with easy access to children, unemployed, uneducated, and to have a history of mental illness or criminal offenses.22

Continue to: Recidivism and treatment

Recidivism and treatment

The recidivism rate among sexual offenders averages 13.7% at 3- to 6-year follow-up,although rates vary by type of sexual offense.23 Individuals who committed rape have the highest rate of recidivism, while those who engaged in incest have the lowest. Three key points about sexual offender recidivism are:

- it declines over time and with increased age.

- sexual offenders are more like to commit a nonsexual offense than a sexual offense.

- sexual offenders who have undergone treatment are 26.3% less likely to reoffend.23

Although there is no standard of treatment, current interventions include external control, reduction of sexual drive, treatment of comorbid conditions, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), and dynamic psychotherapy. External control relies on an outside entity that affects the individual’s behavior. For sexually deviant behaviors, simply making the act illegal or involving the law may inhibit many individuals from acting on a thought. Additional external control may include pharmacotherapy, which ranges from nonhormonal options such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) to hormonal options. Therapy tends to focus on social skills training, sex education, cognitive restructuring, and identifying triggers, as well as victim empathy. The best indicators for successful treatment include an absence of comorbidities, increased age, and adult interpersonal relationships.24

Treatment choice may be predicated on the severity of the paraphilia. Psychotherapy alone is recommended for individuals able to maintain functioning if it does not affect their conventional sexual activity. Common treatment for low-risk individuals is psychotherapy and an SSRI. As risk increases, so does treatment with pharmacologic agents. Beyond SSRIs, moderate offenders may be treated with an SSRI and a low-dose antiandrogen. This is escalated in high-risk violent offenders to long-acting gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogs and synthetic steroidal analogs.25

An evolving class of disorders

With the evolution and accessibility of pornography, uncommon sexual practices have become more common, gaining notoriety and increased social acceptance. As a result, mental health professionals may be tasked with evaluating patients for possible paraphilic disorders. A common misconception is that individuals with sexually deviant thoughts, sexual offenders, and patients with paraphilic disorders are all the same. However, more commonly, sexual offenders do not have a paraphilic disorder. In the case of SVPs, outside of imprisonment, civil commitment remains a consideration for possible treatment. To meet the threshold of civil commitment, a sexual offender must have a “mental abnormality,” which is most commonly a paraphilic disorder. The treatment of paraphilic disorders remains a difficult task and includes a mixture of psychotherapy and medication options.

CASE CONTINUED

Mr. J begins weekly CBT to gain control of his voyeuristic fantasies without impacting his conventional sexual activity and desire. He responds well to treatment, and after 18 months, begins a typical sexual relationship with a woman. Although his voyeuristic thoughts remain, the urge to act on the thoughts decreases as Mr. J develops coping mechanisms. He does not require pharmacologic treatment.

Bottom Line

Individuals with paraphilic disorders are too often portrayed as sexual deviants or criminals. Psychiatrists must review each case with careful consideration of individual risk factors, such as the patient’s sexual history, to evaluate potential treatment options while determining if they pose a threat to the public.

Related Resources

- Sorrentino R, Abramowitz J. Minor-attracted persons: a neglected population. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(7):21-27. doi:10.12788/cp.0149

- Berlin FS. Paraphilic disorders: a better understanding. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(4):22-26,28.

1. Federoff JP. The paraphilias. In: Gelder MG, Andreasen NC, López-Ibor JJ Jr, Geddes JR, eds. New Oxford Textbook of Psychiatry. 2nd ed. Oxford University Press; 2012:832-842.

2. Grubin D. Medical models and interventions in sexual deviance. In: Laws R, O’Donohue WT, eds. Sexual Deviance: Theory, Assessment and Treatment. 2nd ed. Guilford Press; 2008:594-610.

3. Guidry LL, Saleh FM. Clinical considerations of paraphilic sex offenders with comorbid psychiatric conditions. Sex Addict Compulsivity. 2004;11(1-2):21-34.

4. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

5. Balon R. Paraphilic disorders. In: Roberts LW, Hales RE, Yudofsky SC, eds. The American Psychiatric Association Publishing Textbook of Psychiatry. 7th ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2019:749-770.

6. Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P. Paraphilic disorders. Kaplan and Sadock’s Synopsis of Psychiatry. 11th ed. Wolters Kluwer; 2015:593-599.

7. First MB, Halon RL. Use of DSM paraphilia diagnosis in sexually violent predator commitment cases. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2008;36(4):443-454.

8. Specht v Patterson, 386 US 605 (1967).

9. Ra EP. The civil confinement of sexual predators: a delicate balance. J Civ Rts Econ Dev. 2007;22(1):335-372.

10. Felthous AR, Ko J. Sexually violent predator law in the United States. East Asian Arch Psychiatry. 2018;28(4):159-173.

11. Allen v Illinois, 478 US 364 (1986).

12. Kansas v Hendricks, 521 US 346 (1997).

13. Kansas v Crane, 534 US 407 (2002).

14. McKune v Lile, 536 US 24 (2002).

15. United States v Comstock, 560 US 126 (2010).

16. Adam Walsh Child Protection and Safety Act of 2006, HR 4472, 109th Cong (2006). Accessed April 25, 2022. https://www.congress.gov/bill/109th-congress/house-bill/4472

17. Tucker DE, Brakel SJ. Sexually violent predator laws. In: Rosner R, Scott C, eds. Principles and Practice of Forensic Psychiatry. 3rd ed. CRC Press; 2017:823-831.

18. Wash. Rev. Code. Ann. §71.09.020(8)

19. Bradford J, de Amorim Levin GV, Booth BD, et al. Forensic assessment of sex offenders. In: Gold LH, Frierson RL, eds. The American Psychiatric Association Publishing Textbook of Forensic Psychiatry. 3rd ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2017:382-397.

20. Mellor E, Duff S. The use of pornography and the relationship between pornography exposure and sexual offending in males: a systematic review. Aggress Violent Beh. 2019;46:116-126.

21. Failure To Register, 18 USC § 2250 (2012). Accessed April 25, 2022. https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/USCODE-2011-title18/USCODE-2011-title18-partI-chap109B-sec2250

22. Hirschtritt ME, Tucker D, Binder RL. Risk assessment of online child sexual exploitation offenders. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2019;47(2):155-164.

23. Blasko BL. Overview of sexual offender typologies, recidivism, and treatment. In: Jeglic EL, Calkins C, eds. Sexual Violence: Evidence Based Policy and Prevention. Springer; 2016:11-29.

24. Thibaut F, Cosyns P, Fedoroff JP, et al; WFSBP Task Force on Paraphilias. The World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) 2020 guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of paraphilic disorders. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2020;21(6):412-490.

25. Holoyda B. Paraphilias: from diagnosis to treatment. Psychiatric Times. 2019;36(12).

Mr. J, age 23, presents to an outpatient mental health clinic for treatment of anxiety. He has no psychiatric history, is dressed neatly, and recently finished graduate school with a degree in accounting. Mr. J is reserved during the initial psychiatric evaluation and provides only basic facts about his developmental history.

Mr. J comes from a middle-class household with no history of trauma or substance use. He does not report any symptoms consistent with anxiety, but discloses a history of sexual preoccupations. Mr. J says that during adolescence he developed a predilection for observing others engage in sexual activity. In his late teens, he began following couples to their homes in the hope of witnessing sexual intimacy. In the rare instance that his voyeuristic fantasy comes to fruition, he masturbates and achieves sexual gratification he is incapable of experiencing otherwise. Mr. J notes that he has not yet been caught, but he expresses concern and embarrassment related to his actions. He concludes by noting that he seeks help because the frequency of this behavior has steadily increased.

How would you treat Mr. J? Where does the line exist between a normophilic sexual interest, fantasy or urge, and a paraphilia? Does Mr. J qualify as a sexually violent predator?

From The Rocky Horror Picture Show to Fifty Shades of Grey, sensationalized portrayals of sexual deviancy have long been present in popular culture. The continued popularity of serial killers years after their crimes seems in part related to the extreme sexual torture their victims often endure. However, a sexual offense does not always qualify as a paraphilic disorder.1 In fact, many individuals with paraphilic disorders never engage in illegal activity. Additionally, experiencing sexually deviant thoughts alone does not qualify as a paraphilic disorder.1

A thorough psychiatric evaluation should include a discussion of the patient’s sexual history, including the potential of sexual dysfunction and abnormal desires or behaviors. Most individuals with sexual dysfunction do not have a paraphilic disorder.2 DSM-5 and ICD-11 classify sexual dysfunction and paraphilic disorders in different categories. However, previous editions grouped them together under sexual and gender identity disorders. Individuals with paraphilic disorders may not originally present to the outpatient setting for a paraphilic disorder, but instead may first seek treatment for a more common comorbid disorder, such as a mood disorder, personality disorder, or substance use disorder.3

Diagnostically speaking, if individuals do not experience distress or issues with functionality and lack legal charges (suggesting that they have not violated the rights of others), they are categorized as having an atypical sexual interest but do not necessarily meet the criteria for a disorder.4 This article provides an overview of paraphilic disorders as well as forensic considerations when examining individuals with sexually deviant behaviors.

Overview of paraphilic disorders

DSM-5 characterizes a paraphilic disorder as “recurrent, intense sexually arousing fantasies, sexual urges, or behaviors generally involving nonhuman objects or nonconsenting partners for at least 6 months. The individual must have acted on the thought and/or it caused clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning.” DSM-5 outlines 9 categories of paraphilic disorders, which are described in Table 1.4,5

Continue to: Paraphilic disorders are more common...

Paraphilic disorders are more common in men than in women; the 2 most prevalent are voyeuristic disorder and frotteuristic disorder.6 The incidence of paraphilias in the general outpatient setting varies by disorder. Approximately 45% of individuals with pedophilic disorder seek treatment, whereas only 1% of individuals with zoophilia seek treatment.6 The incidence of paraphilic acts also varies drastically; individuals with exhibitionistic disorder engaged in an average of 50 acts vs only 3 for individuals with sexual sadism.6 Not all individuals with paraphilic disorders commit crimes. Approximately 58% of sexual offenders meet the criteria for a paraphilic disorder, but antisocial personality disorder is a far more common diagnosis.7

Sexual psychopath statutes: Phase 1

In 1937, Michigan became the first state to enact sexual psychopath statutes, allowing for indeterminate sentencing and the civil commitment/treatment of sex offenders with repeated convictions. By the 1970s, more than 30 states had enacted similar statutes. It was not until 1967, in Specht v Patterson,8 that the United States Supreme Court unanimously ruled that the Fourteenth Amendment Due Process Clause was violated when Francis Eddie Specht faced life in prison following his conviction for indecent liberties under the Colorado Sex Offenders Act.

Specht was convicted in 1959 for indecent liberties after pleading guilty to enticing a child younger than age 16 into an office and engaging in sexual activities with them. At the time of Specht’s conviction, the crime of indecent liberties carried a punishment of 10 years. However, Specht was sentenced under the Sexual Offenders Act, which allowed for an indeterminate sentence of 1 day to life in prison. The Supreme Court noted that Specht was denied the right to be present with counsel, to confront the evidence against him, to cross-examine witnesses, and to offer his own evidence, which was a violation of his constitutionally guaranteed Fourteenth Amendment right to Procedural Due Process. The decision led most states to repeal early sexual psychopath statutes.8

Sexually violent predator laws: Phase 2

After early sexual psychopath statutes were repealed, many states pushed to update sex offender laws in response to the Earl Shriner case.9 In 1989, Shriner was released from prison after serving a 10-year sentence for sexually assaulting 2 teenage girls. At the time, he did not meet the criteria for civil commitment in the state of Washington. On the day he was released, Shriner cut off a young boy’s penis and left him to die. Washington subsequently became the first of many states to enact sexually violent predator (SVP) laws. Table 210 shows states and districts that have SVP civil commitment laws.

A series of United States Supreme Court cases solidified current sexual offender civil commitment laws (Table 38,11-15).

Continue to: Allen v Illinois

Allen v Illinois (1986).11 The Court ruled that forcing an individual to participate in a psychiatric evaluation prior to a sexually dangerous person’s commitment hearing did not violate the individual’s Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination because the purpose of the evaluation was to provide treatment, not punishment.

Kansas v Hendricks (1997).12 The Court upheld that the Kansas Sexually Violent Predator Act was constitutional and noted that the use of the broad term “mental abnormality” (in lieu of the more specific term “mental illness”) does not violate an individual’s Fourteenth Amendment right to substantive due process. Additionally, the Court opined that the constitutional ban on double jeopardy and ex post facto lawmaking does not apply because the procedures are civil, not criminal.

Kansas v Crane (2002).13 The Court upheld the Kansas Sexually Violent Predator Act, stating that mental illness and dangerousness are essential elements to meet the criteria for civil commitment. The Court added that proof of partial (not total) “volitional impairment” is all that is required to meet the threshold of sexual dangerousness.

McKune v Lile (2002).14 The Court ruled that a policy requiring participation in polygraph testing, which would lead to the disclosure of sexual crimes (even those that have not been prosecuted), does not violate an individual’s Fifth Amendment rights because it serves a vital penological purpose.

Adam Walsh Child Protection and Safety Act of 200616; United States v Comstock (2010).15 This act and subsequent case reinforced the federal government’s right to civilly commit sexually dangerous persons approaching the end of their prison sentences.

Continue to: What is requiried for civil commitment?

What is required for civil commitment?

SVP laws require 4 conditions to be met for the civil commitment of sexual offenders (Table 417). In criteria 1, “charges” is a key word, because this allows individuals found Not Guilty by Reason of Insanity or Incompetent to Stand Trial to be civilly committed. Criteria 2 defines “mental abnormality” as a “congenital or acquired condition affecting the emotional or volitional capacity which predisposes the person to commit criminal sexual acts in a degree constituting such person a menace to the health and safety of others.”18 This is a broad definition, and allows individuals with personality disorders to be civilly committed (although most sexual offenders are committed for having a paraphilic disorder). To determine risk, various actuarial instruments are used to assess for sexually violent recidivism, including (but not limited to) the Static-99R, Sexual Violence Risk-20, and the Sex Offender Risk Appraisal Guide.19

Although the percentages vary, sex offenders rarely are civilly committed following their criminal sentence. In California, approximately 1.5% of sex offenders are civilly committed.17 The standard of proof for civil commitment varies by state between “clear and convincing evidence” and “beyond a reasonable doubt.” As sex offenders approach the end of their sentence, sexually violent offenders are identified to the general population and referred for a psychiatric evaluation. If the individual meets the 4 criteria for commitment (Table 417), their case is sent to the prosecuting attorney’s office. If accepted, the court holds a probable cause hearing, followed by a full trial.

Pornography and sex offenders

Pornography has long been considered a risk factor for sexual offending, and the role of pornography in influencing sexual behavior has drawn recent interest in research towards predicting future offenses. However, a 2019 systematic review by Mellor et al20 on the relationship between pornography and sexual offending suggested that early exposure to pornography is not a risk factor for sexual offending, nor is the risk of offending increased shortly after pornography exposure. Additionally, pornography use did not predict recidivism in low-risk sexual offenders, but did in high-risk offenders.

The use of child pornography presents a set of new risk factors. Prohibited by federal and state law, child pornography is defined under Section 2256 of Title 18, United States Code, as any visual depiction of sexually explicit conduct involving a minor (someone <age 18). Visual depictions include photographs, videos, digital or computer-generated images indistinguishable from an actual minor, and images created to depict a minor. The law does not require an image of a child engaging in sexual activity for the image to be characterized as child pornography. Offenders are also commonly charged with the distribution of child pornography. A conviction of child pornography possession carries a 15- to 30-year sentence, and distribution carries a 5- to 20-year sentence.21 The individual must also file for the sex offender registry, which may restrict their employment and place of residency.

It is unclear what percentage of individuals charged with child pornography have a history of prior sexual offenses. Numerous studies suggest there is a low risk of online offenders without prior offenses becoming contact offenders. Characteristics of online-only offenders include being White, a single male, age 20 to 30, well-educated, and employed, and having antisocial traits and a history of sexual deviancy.22 Contact offenders tend to be married with easy access to children, unemployed, uneducated, and to have a history of mental illness or criminal offenses.22

Continue to: Recidivism and treatment

Recidivism and treatment

The recidivism rate among sexual offenders averages 13.7% at 3- to 6-year follow-up,although rates vary by type of sexual offense.23 Individuals who committed rape have the highest rate of recidivism, while those who engaged in incest have the lowest. Three key points about sexual offender recidivism are:

- it declines over time and with increased age.

- sexual offenders are more like to commit a nonsexual offense than a sexual offense.

- sexual offenders who have undergone treatment are 26.3% less likely to reoffend.23

Although there is no standard of treatment, current interventions include external control, reduction of sexual drive, treatment of comorbid conditions, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), and dynamic psychotherapy. External control relies on an outside entity that affects the individual’s behavior. For sexually deviant behaviors, simply making the act illegal or involving the law may inhibit many individuals from acting on a thought. Additional external control may include pharmacotherapy, which ranges from nonhormonal options such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) to hormonal options. Therapy tends to focus on social skills training, sex education, cognitive restructuring, and identifying triggers, as well as victim empathy. The best indicators for successful treatment include an absence of comorbidities, increased age, and adult interpersonal relationships.24

Treatment choice may be predicated on the severity of the paraphilia. Psychotherapy alone is recommended for individuals able to maintain functioning if it does not affect their conventional sexual activity. Common treatment for low-risk individuals is psychotherapy and an SSRI. As risk increases, so does treatment with pharmacologic agents. Beyond SSRIs, moderate offenders may be treated with an SSRI and a low-dose antiandrogen. This is escalated in high-risk violent offenders to long-acting gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogs and synthetic steroidal analogs.25

An evolving class of disorders

With the evolution and accessibility of pornography, uncommon sexual practices have become more common, gaining notoriety and increased social acceptance. As a result, mental health professionals may be tasked with evaluating patients for possible paraphilic disorders. A common misconception is that individuals with sexually deviant thoughts, sexual offenders, and patients with paraphilic disorders are all the same. However, more commonly, sexual offenders do not have a paraphilic disorder. In the case of SVPs, outside of imprisonment, civil commitment remains a consideration for possible treatment. To meet the threshold of civil commitment, a sexual offender must have a “mental abnormality,” which is most commonly a paraphilic disorder. The treatment of paraphilic disorders remains a difficult task and includes a mixture of psychotherapy and medication options.

CASE CONTINUED

Mr. J begins weekly CBT to gain control of his voyeuristic fantasies without impacting his conventional sexual activity and desire. He responds well to treatment, and after 18 months, begins a typical sexual relationship with a woman. Although his voyeuristic thoughts remain, the urge to act on the thoughts decreases as Mr. J develops coping mechanisms. He does not require pharmacologic treatment.

Bottom Line

Individuals with paraphilic disorders are too often portrayed as sexual deviants or criminals. Psychiatrists must review each case with careful consideration of individual risk factors, such as the patient’s sexual history, to evaluate potential treatment options while determining if they pose a threat to the public.

Related Resources

- Sorrentino R, Abramowitz J. Minor-attracted persons: a neglected population. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(7):21-27. doi:10.12788/cp.0149

- Berlin FS. Paraphilic disorders: a better understanding. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(4):22-26,28.

Mr. J, age 23, presents to an outpatient mental health clinic for treatment of anxiety. He has no psychiatric history, is dressed neatly, and recently finished graduate school with a degree in accounting. Mr. J is reserved during the initial psychiatric evaluation and provides only basic facts about his developmental history.

Mr. J comes from a middle-class household with no history of trauma or substance use. He does not report any symptoms consistent with anxiety, but discloses a history of sexual preoccupations. Mr. J says that during adolescence he developed a predilection for observing others engage in sexual activity. In his late teens, he began following couples to their homes in the hope of witnessing sexual intimacy. In the rare instance that his voyeuristic fantasy comes to fruition, he masturbates and achieves sexual gratification he is incapable of experiencing otherwise. Mr. J notes that he has not yet been caught, but he expresses concern and embarrassment related to his actions. He concludes by noting that he seeks help because the frequency of this behavior has steadily increased.

How would you treat Mr. J? Where does the line exist between a normophilic sexual interest, fantasy or urge, and a paraphilia? Does Mr. J qualify as a sexually violent predator?

From The Rocky Horror Picture Show to Fifty Shades of Grey, sensationalized portrayals of sexual deviancy have long been present in popular culture. The continued popularity of serial killers years after their crimes seems in part related to the extreme sexual torture their victims often endure. However, a sexual offense does not always qualify as a paraphilic disorder.1 In fact, many individuals with paraphilic disorders never engage in illegal activity. Additionally, experiencing sexually deviant thoughts alone does not qualify as a paraphilic disorder.1

A thorough psychiatric evaluation should include a discussion of the patient’s sexual history, including the potential of sexual dysfunction and abnormal desires or behaviors. Most individuals with sexual dysfunction do not have a paraphilic disorder.2 DSM-5 and ICD-11 classify sexual dysfunction and paraphilic disorders in different categories. However, previous editions grouped them together under sexual and gender identity disorders. Individuals with paraphilic disorders may not originally present to the outpatient setting for a paraphilic disorder, but instead may first seek treatment for a more common comorbid disorder, such as a mood disorder, personality disorder, or substance use disorder.3

Diagnostically speaking, if individuals do not experience distress or issues with functionality and lack legal charges (suggesting that they have not violated the rights of others), they are categorized as having an atypical sexual interest but do not necessarily meet the criteria for a disorder.4 This article provides an overview of paraphilic disorders as well as forensic considerations when examining individuals with sexually deviant behaviors.

Overview of paraphilic disorders

DSM-5 characterizes a paraphilic disorder as “recurrent, intense sexually arousing fantasies, sexual urges, or behaviors generally involving nonhuman objects or nonconsenting partners for at least 6 months. The individual must have acted on the thought and/or it caused clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning.” DSM-5 outlines 9 categories of paraphilic disorders, which are described in Table 1.4,5

Continue to: Paraphilic disorders are more common...

Paraphilic disorders are more common in men than in women; the 2 most prevalent are voyeuristic disorder and frotteuristic disorder.6 The incidence of paraphilias in the general outpatient setting varies by disorder. Approximately 45% of individuals with pedophilic disorder seek treatment, whereas only 1% of individuals with zoophilia seek treatment.6 The incidence of paraphilic acts also varies drastically; individuals with exhibitionistic disorder engaged in an average of 50 acts vs only 3 for individuals with sexual sadism.6 Not all individuals with paraphilic disorders commit crimes. Approximately 58% of sexual offenders meet the criteria for a paraphilic disorder, but antisocial personality disorder is a far more common diagnosis.7

Sexual psychopath statutes: Phase 1

In 1937, Michigan became the first state to enact sexual psychopath statutes, allowing for indeterminate sentencing and the civil commitment/treatment of sex offenders with repeated convictions. By the 1970s, more than 30 states had enacted similar statutes. It was not until 1967, in Specht v Patterson,8 that the United States Supreme Court unanimously ruled that the Fourteenth Amendment Due Process Clause was violated when Francis Eddie Specht faced life in prison following his conviction for indecent liberties under the Colorado Sex Offenders Act.

Specht was convicted in 1959 for indecent liberties after pleading guilty to enticing a child younger than age 16 into an office and engaging in sexual activities with them. At the time of Specht’s conviction, the crime of indecent liberties carried a punishment of 10 years. However, Specht was sentenced under the Sexual Offenders Act, which allowed for an indeterminate sentence of 1 day to life in prison. The Supreme Court noted that Specht was denied the right to be present with counsel, to confront the evidence against him, to cross-examine witnesses, and to offer his own evidence, which was a violation of his constitutionally guaranteed Fourteenth Amendment right to Procedural Due Process. The decision led most states to repeal early sexual psychopath statutes.8

Sexually violent predator laws: Phase 2

After early sexual psychopath statutes were repealed, many states pushed to update sex offender laws in response to the Earl Shriner case.9 In 1989, Shriner was released from prison after serving a 10-year sentence for sexually assaulting 2 teenage girls. At the time, he did not meet the criteria for civil commitment in the state of Washington. On the day he was released, Shriner cut off a young boy’s penis and left him to die. Washington subsequently became the first of many states to enact sexually violent predator (SVP) laws. Table 210 shows states and districts that have SVP civil commitment laws.

A series of United States Supreme Court cases solidified current sexual offender civil commitment laws (Table 38,11-15).

Continue to: Allen v Illinois

Allen v Illinois (1986).11 The Court ruled that forcing an individual to participate in a psychiatric evaluation prior to a sexually dangerous person’s commitment hearing did not violate the individual’s Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination because the purpose of the evaluation was to provide treatment, not punishment.

Kansas v Hendricks (1997).12 The Court upheld that the Kansas Sexually Violent Predator Act was constitutional and noted that the use of the broad term “mental abnormality” (in lieu of the more specific term “mental illness”) does not violate an individual’s Fourteenth Amendment right to substantive due process. Additionally, the Court opined that the constitutional ban on double jeopardy and ex post facto lawmaking does not apply because the procedures are civil, not criminal.

Kansas v Crane (2002).13 The Court upheld the Kansas Sexually Violent Predator Act, stating that mental illness and dangerousness are essential elements to meet the criteria for civil commitment. The Court added that proof of partial (not total) “volitional impairment” is all that is required to meet the threshold of sexual dangerousness.

McKune v Lile (2002).14 The Court ruled that a policy requiring participation in polygraph testing, which would lead to the disclosure of sexual crimes (even those that have not been prosecuted), does not violate an individual’s Fifth Amendment rights because it serves a vital penological purpose.

Adam Walsh Child Protection and Safety Act of 200616; United States v Comstock (2010).15 This act and subsequent case reinforced the federal government’s right to civilly commit sexually dangerous persons approaching the end of their prison sentences.

Continue to: What is requiried for civil commitment?

What is required for civil commitment?

SVP laws require 4 conditions to be met for the civil commitment of sexual offenders (Table 417). In criteria 1, “charges” is a key word, because this allows individuals found Not Guilty by Reason of Insanity or Incompetent to Stand Trial to be civilly committed. Criteria 2 defines “mental abnormality” as a “congenital or acquired condition affecting the emotional or volitional capacity which predisposes the person to commit criminal sexual acts in a degree constituting such person a menace to the health and safety of others.”18 This is a broad definition, and allows individuals with personality disorders to be civilly committed (although most sexual offenders are committed for having a paraphilic disorder). To determine risk, various actuarial instruments are used to assess for sexually violent recidivism, including (but not limited to) the Static-99R, Sexual Violence Risk-20, and the Sex Offender Risk Appraisal Guide.19

Although the percentages vary, sex offenders rarely are civilly committed following their criminal sentence. In California, approximately 1.5% of sex offenders are civilly committed.17 The standard of proof for civil commitment varies by state between “clear and convincing evidence” and “beyond a reasonable doubt.” As sex offenders approach the end of their sentence, sexually violent offenders are identified to the general population and referred for a psychiatric evaluation. If the individual meets the 4 criteria for commitment (Table 417), their case is sent to the prosecuting attorney’s office. If accepted, the court holds a probable cause hearing, followed by a full trial.

Pornography and sex offenders

Pornography has long been considered a risk factor for sexual offending, and the role of pornography in influencing sexual behavior has drawn recent interest in research towards predicting future offenses. However, a 2019 systematic review by Mellor et al20 on the relationship between pornography and sexual offending suggested that early exposure to pornography is not a risk factor for sexual offending, nor is the risk of offending increased shortly after pornography exposure. Additionally, pornography use did not predict recidivism in low-risk sexual offenders, but did in high-risk offenders.

The use of child pornography presents a set of new risk factors. Prohibited by federal and state law, child pornography is defined under Section 2256 of Title 18, United States Code, as any visual depiction of sexually explicit conduct involving a minor (someone <age 18). Visual depictions include photographs, videos, digital or computer-generated images indistinguishable from an actual minor, and images created to depict a minor. The law does not require an image of a child engaging in sexual activity for the image to be characterized as child pornography. Offenders are also commonly charged with the distribution of child pornography. A conviction of child pornography possession carries a 15- to 30-year sentence, and distribution carries a 5- to 20-year sentence.21 The individual must also file for the sex offender registry, which may restrict their employment and place of residency.

It is unclear what percentage of individuals charged with child pornography have a history of prior sexual offenses. Numerous studies suggest there is a low risk of online offenders without prior offenses becoming contact offenders. Characteristics of online-only offenders include being White, a single male, age 20 to 30, well-educated, and employed, and having antisocial traits and a history of sexual deviancy.22 Contact offenders tend to be married with easy access to children, unemployed, uneducated, and to have a history of mental illness or criminal offenses.22

Continue to: Recidivism and treatment

Recidivism and treatment

The recidivism rate among sexual offenders averages 13.7% at 3- to 6-year follow-up,although rates vary by type of sexual offense.23 Individuals who committed rape have the highest rate of recidivism, while those who engaged in incest have the lowest. Three key points about sexual offender recidivism are:

- it declines over time and with increased age.

- sexual offenders are more like to commit a nonsexual offense than a sexual offense.

- sexual offenders who have undergone treatment are 26.3% less likely to reoffend.23

Although there is no standard of treatment, current interventions include external control, reduction of sexual drive, treatment of comorbid conditions, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), and dynamic psychotherapy. External control relies on an outside entity that affects the individual’s behavior. For sexually deviant behaviors, simply making the act illegal or involving the law may inhibit many individuals from acting on a thought. Additional external control may include pharmacotherapy, which ranges from nonhormonal options such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) to hormonal options. Therapy tends to focus on social skills training, sex education, cognitive restructuring, and identifying triggers, as well as victim empathy. The best indicators for successful treatment include an absence of comorbidities, increased age, and adult interpersonal relationships.24

Treatment choice may be predicated on the severity of the paraphilia. Psychotherapy alone is recommended for individuals able to maintain functioning if it does not affect their conventional sexual activity. Common treatment for low-risk individuals is psychotherapy and an SSRI. As risk increases, so does treatment with pharmacologic agents. Beyond SSRIs, moderate offenders may be treated with an SSRI and a low-dose antiandrogen. This is escalated in high-risk violent offenders to long-acting gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogs and synthetic steroidal analogs.25

An evolving class of disorders

With the evolution and accessibility of pornography, uncommon sexual practices have become more common, gaining notoriety and increased social acceptance. As a result, mental health professionals may be tasked with evaluating patients for possible paraphilic disorders. A common misconception is that individuals with sexually deviant thoughts, sexual offenders, and patients with paraphilic disorders are all the same. However, more commonly, sexual offenders do not have a paraphilic disorder. In the case of SVPs, outside of imprisonment, civil commitment remains a consideration for possible treatment. To meet the threshold of civil commitment, a sexual offender must have a “mental abnormality,” which is most commonly a paraphilic disorder. The treatment of paraphilic disorders remains a difficult task and includes a mixture of psychotherapy and medication options.

CASE CONTINUED

Mr. J begins weekly CBT to gain control of his voyeuristic fantasies without impacting his conventional sexual activity and desire. He responds well to treatment, and after 18 months, begins a typical sexual relationship with a woman. Although his voyeuristic thoughts remain, the urge to act on the thoughts decreases as Mr. J develops coping mechanisms. He does not require pharmacologic treatment.

Bottom Line

Individuals with paraphilic disorders are too often portrayed as sexual deviants or criminals. Psychiatrists must review each case with careful consideration of individual risk factors, such as the patient’s sexual history, to evaluate potential treatment options while determining if they pose a threat to the public.

Related Resources

- Sorrentino R, Abramowitz J. Minor-attracted persons: a neglected population. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(7):21-27. doi:10.12788/cp.0149

- Berlin FS. Paraphilic disorders: a better understanding. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(4):22-26,28.

1. Federoff JP. The paraphilias. In: Gelder MG, Andreasen NC, López-Ibor JJ Jr, Geddes JR, eds. New Oxford Textbook of Psychiatry. 2nd ed. Oxford University Press; 2012:832-842.

2. Grubin D. Medical models and interventions in sexual deviance. In: Laws R, O’Donohue WT, eds. Sexual Deviance: Theory, Assessment and Treatment. 2nd ed. Guilford Press; 2008:594-610.

3. Guidry LL, Saleh FM. Clinical considerations of paraphilic sex offenders with comorbid psychiatric conditions. Sex Addict Compulsivity. 2004;11(1-2):21-34.

4. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

5. Balon R. Paraphilic disorders. In: Roberts LW, Hales RE, Yudofsky SC, eds. The American Psychiatric Association Publishing Textbook of Psychiatry. 7th ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2019:749-770.

6. Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P. Paraphilic disorders. Kaplan and Sadock’s Synopsis of Psychiatry. 11th ed. Wolters Kluwer; 2015:593-599.

7. First MB, Halon RL. Use of DSM paraphilia diagnosis in sexually violent predator commitment cases. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2008;36(4):443-454.

8. Specht v Patterson, 386 US 605 (1967).

9. Ra EP. The civil confinement of sexual predators: a delicate balance. J Civ Rts Econ Dev. 2007;22(1):335-372.

10. Felthous AR, Ko J. Sexually violent predator law in the United States. East Asian Arch Psychiatry. 2018;28(4):159-173.

11. Allen v Illinois, 478 US 364 (1986).

12. Kansas v Hendricks, 521 US 346 (1997).

13. Kansas v Crane, 534 US 407 (2002).

14. McKune v Lile, 536 US 24 (2002).

15. United States v Comstock, 560 US 126 (2010).

16. Adam Walsh Child Protection and Safety Act of 2006, HR 4472, 109th Cong (2006). Accessed April 25, 2022. https://www.congress.gov/bill/109th-congress/house-bill/4472

17. Tucker DE, Brakel SJ. Sexually violent predator laws. In: Rosner R, Scott C, eds. Principles and Practice of Forensic Psychiatry. 3rd ed. CRC Press; 2017:823-831.

18. Wash. Rev. Code. Ann. §71.09.020(8)

19. Bradford J, de Amorim Levin GV, Booth BD, et al. Forensic assessment of sex offenders. In: Gold LH, Frierson RL, eds. The American Psychiatric Association Publishing Textbook of Forensic Psychiatry. 3rd ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2017:382-397.

20. Mellor E, Duff S. The use of pornography and the relationship between pornography exposure and sexual offending in males: a systematic review. Aggress Violent Beh. 2019;46:116-126.

21. Failure To Register, 18 USC § 2250 (2012). Accessed April 25, 2022. https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/USCODE-2011-title18/USCODE-2011-title18-partI-chap109B-sec2250

22. Hirschtritt ME, Tucker D, Binder RL. Risk assessment of online child sexual exploitation offenders. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2019;47(2):155-164.

23. Blasko BL. Overview of sexual offender typologies, recidivism, and treatment. In: Jeglic EL, Calkins C, eds. Sexual Violence: Evidence Based Policy and Prevention. Springer; 2016:11-29.

24. Thibaut F, Cosyns P, Fedoroff JP, et al; WFSBP Task Force on Paraphilias. The World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) 2020 guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of paraphilic disorders. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2020;21(6):412-490.

25. Holoyda B. Paraphilias: from diagnosis to treatment. Psychiatric Times. 2019;36(12).

1. Federoff JP. The paraphilias. In: Gelder MG, Andreasen NC, López-Ibor JJ Jr, Geddes JR, eds. New Oxford Textbook of Psychiatry. 2nd ed. Oxford University Press; 2012:832-842.

2. Grubin D. Medical models and interventions in sexual deviance. In: Laws R, O’Donohue WT, eds. Sexual Deviance: Theory, Assessment and Treatment. 2nd ed. Guilford Press; 2008:594-610.

3. Guidry LL, Saleh FM. Clinical considerations of paraphilic sex offenders with comorbid psychiatric conditions. Sex Addict Compulsivity. 2004;11(1-2):21-34.

4. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

5. Balon R. Paraphilic disorders. In: Roberts LW, Hales RE, Yudofsky SC, eds. The American Psychiatric Association Publishing Textbook of Psychiatry. 7th ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2019:749-770.

6. Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P. Paraphilic disorders. Kaplan and Sadock’s Synopsis of Psychiatry. 11th ed. Wolters Kluwer; 2015:593-599.

7. First MB, Halon RL. Use of DSM paraphilia diagnosis in sexually violent predator commitment cases. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2008;36(4):443-454.

8. Specht v Patterson, 386 US 605 (1967).

9. Ra EP. The civil confinement of sexual predators: a delicate balance. J Civ Rts Econ Dev. 2007;22(1):335-372.

10. Felthous AR, Ko J. Sexually violent predator law in the United States. East Asian Arch Psychiatry. 2018;28(4):159-173.

11. Allen v Illinois, 478 US 364 (1986).

12. Kansas v Hendricks, 521 US 346 (1997).

13. Kansas v Crane, 534 US 407 (2002).

14. McKune v Lile, 536 US 24 (2002).

15. United States v Comstock, 560 US 126 (2010).

16. Adam Walsh Child Protection and Safety Act of 2006, HR 4472, 109th Cong (2006). Accessed April 25, 2022. https://www.congress.gov/bill/109th-congress/house-bill/4472

17. Tucker DE, Brakel SJ. Sexually violent predator laws. In: Rosner R, Scott C, eds. Principles and Practice of Forensic Psychiatry. 3rd ed. CRC Press; 2017:823-831.

18. Wash. Rev. Code. Ann. §71.09.020(8)

19. Bradford J, de Amorim Levin GV, Booth BD, et al. Forensic assessment of sex offenders. In: Gold LH, Frierson RL, eds. The American Psychiatric Association Publishing Textbook of Forensic Psychiatry. 3rd ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2017:382-397.

20. Mellor E, Duff S. The use of pornography and the relationship between pornography exposure and sexual offending in males: a systematic review. Aggress Violent Beh. 2019;46:116-126.

21. Failure To Register, 18 USC § 2250 (2012). Accessed April 25, 2022. https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/USCODE-2011-title18/USCODE-2011-title18-partI-chap109B-sec2250

22. Hirschtritt ME, Tucker D, Binder RL. Risk assessment of online child sexual exploitation offenders. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2019;47(2):155-164.

23. Blasko BL. Overview of sexual offender typologies, recidivism, and treatment. In: Jeglic EL, Calkins C, eds. Sexual Violence: Evidence Based Policy and Prevention. Springer; 2016:11-29.

24. Thibaut F, Cosyns P, Fedoroff JP, et al; WFSBP Task Force on Paraphilias. The World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) 2020 guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of paraphilic disorders. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2020;21(6):412-490.

25. Holoyda B. Paraphilias: from diagnosis to treatment. Psychiatric Times. 2019;36(12).