User login

We believe that patients, families, and other stakeholders can provide meaningful contributions throughout the research process. Involvement of a diverse group of stakeholders is also encouraged by the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), which emphasizes research focused on patient‐ and family‐centered outcomes.[1] Patient and family engagement in healthcare, however, has generally focused on children and adults with chronic conditions.[1, 2] Engagement of families of children with serious acute illnesses is infrequent, and no studies have documented the feasibility or acceptability of different methods of family engagement.[3] Furthermore, stakeholders, such as nurses, may participate in study execution but rarely receive opportunities to inform the research process. In this Perspective, we describe our experiences with family engagement using a novel approach of serial, focused, short‐term engagement of stakeholders.

PRESTUDY WORK

In 2012, our institution introduced a nurse‐led transitional home‐visit program, an approach associated with reduced healthcare utilization in adults.[4] Patients hospitalized for acute illness received a 1‐time transitional home visit 24 to 72 hours after hospital discharge. We formed a multidisciplinary team, consisting of physicians, nurse scientists, home healthcare (HHC) nursing staff, patient families, and research staff to design a mixed‐methods study of the transitional home visit, which was funded by PCORI in 2014. This study, the Hospital‐to‐Home Outcomes (H2O) study, has 3 aims: (1) identify barriers to successful transitions home and outcomes of such transitions that are meaningful to families, (2) optimize the transitional home visits to address family‐identified barriers and outcomes, and (3) determine the efficacy of transitional home visits through a randomized control trial.

Two parents joined the study team during study development. Both had children hospitalized for acute illnesses, received a transitional home visit, and participated in a pilot focus group to provide insight into barriers families encounter during care transitions. These parents made valuable contributions, including recommending strategies for patient enrollment and retention. They also committed to participating in regularly scheduled study meetings and ad hoc discussions. However, feedback from the pilot focus group also highlighted a potential research engagement challenge; specifically, once the acute illness resolved, many families were primarily focused on the return to their normal routine and may not be easily engaged in research.

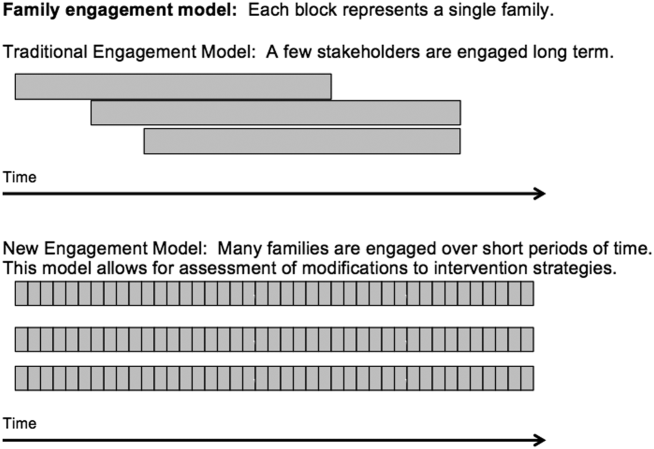

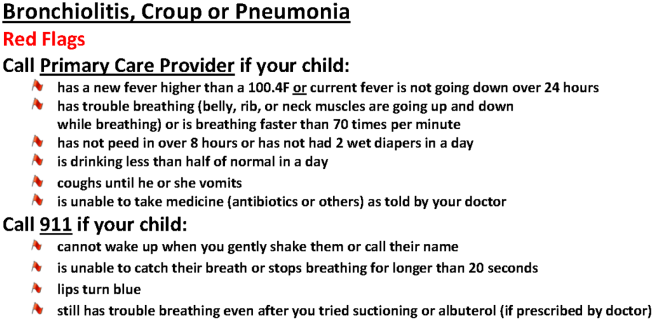

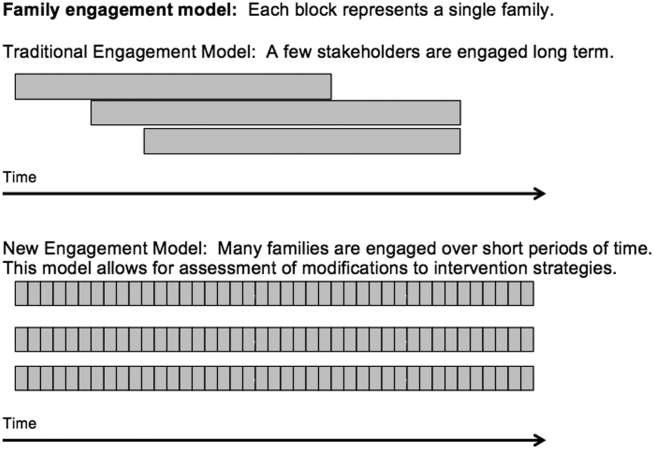

Based on family input, we included several mechanisms to engage caregivers of children with acute illness in the study design of H2O. Each design element allowed families and other stakeholders to contribute via short‐term focused approaches (eg, focus groups, phone surveys). These short‐term interactions drove iterative changes in study processes and approaches, including how to measure outcomes important to families. Rather than a small group of stakeholders making a series of recommendations over a long period of time, we had dozens of individual stakeholders make a few recommendations apiece that were quickly implemented and subsequently tested via feedback from the next few stakeholders (Figure 1).

PATIENT AND STAKEHOLDER ENGAGEMENT IN THE H2O STUDY

Having the short‐term, focused engagement strategy built into the study proved beneficial, when the 2 parents who were part of the initial design team and had planned to participate longitudinally were no longer able to participate. Over time, their circumstances changed. One parent moved out of the area to pursue a professional opportunity, and the second parent became increasingly difficult to reach and unable to join planned study meetings, a situation anticipated by the pilot focus group participants. These 2 instances illustrate challenges with long‐term engagement of families in research when the potential primary driver of their engagement, their child's acute illness, has resolved.

Short‐Term Focused Engagement Via Focus Groups With Parents/Caregivers

The first aim of the H2O study used 15 focus groups and semistructured interviews with parents/caregivers of recently discharged patients to identify barriers to and metrics of successful transitions of care from the hospital to home. The focus group question guide was developed by the research team and adapted as the focus groups progressed to incorporate new issues raised by participants. Analysis of focus group data revealed opportunities to improve the transitional home visit and identified outcomes important to families, including the need for emotional reassurance in the immediate period after discharge and the impact on family finances.

Short‐Term Focused Engagement Via Phone Calls With Parents/Caregivers

To continuously improve study processes and the transitional home visit during the second aim of H2O, we relied on short‐term focused engagement from 2 stakeholder groups, families and field nurses. We completed 107 phone calls with families who received a transitional home visit during the visit optimization period. These calls, completed 3 to 7 days after the visit, assessed parental perceptions of the effect of recent visit modifications through a standardized survey documented in an electronic database. These data were utilized in plan‐do‐study‐act cycles,[5] every 1 to 2 weeks, to determine if additional modifications to the visits were necessary. A cycle ended when the calls no longer provided new information. The questions asked on the calls also changed over time as different interventions were tested.

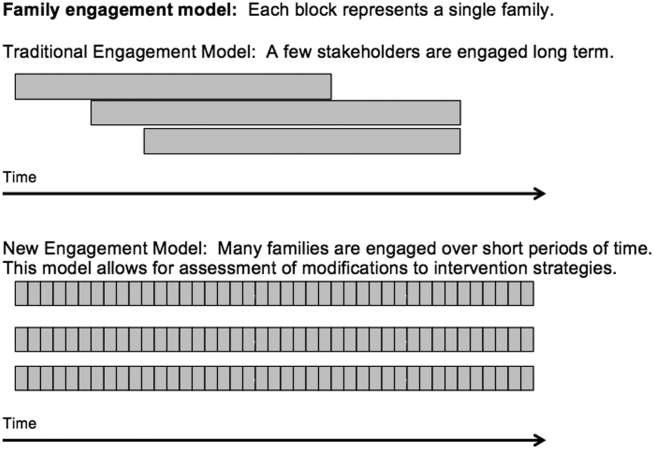

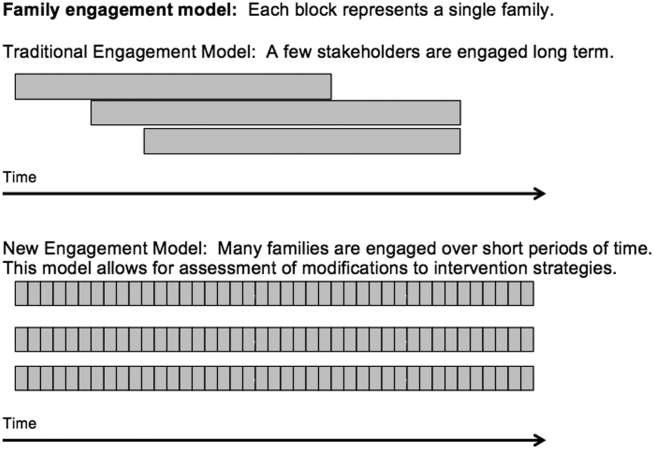

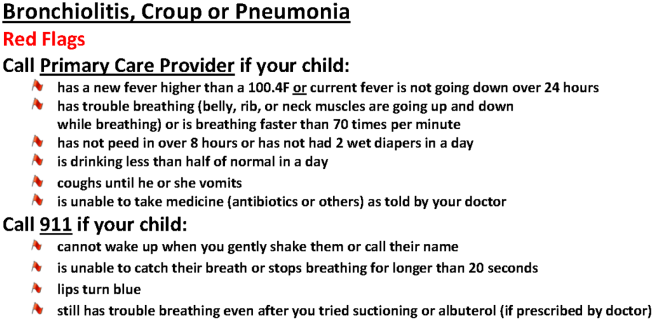

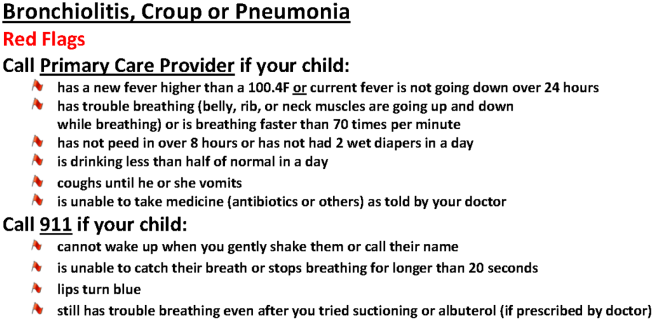

As an example, in aim 1, families highlighted the lack of clarity of discharge instructions, particularly regarding when and why to return for medical care. Thus, we developed condition‐specific red flag reminder cards to be shared at transitional home visits to help families remember and recognize concerning signs and symptoms and understand when additional evaluation may be warranted (Figure 2). Families in postvisit calls endorsed the concept of red flags, but sometimes preferred electronic rather than paper versions of the red flag cards to facilitate sharing with family members. Thus, we tested and refined texting the red flag information to families. Subsequent calls strongly supported this practice, so we will continue to use it during the third aim, the randomized trial of the transitional home visit.

The remaining calls (N=72) were completed 14 days after the visit to mirror the time frame for follow‐up calls in the planned randomized trial. These calls allowed us to test measurement of family‐identified outcomes and determine their usability in the trial. We used family feedback to shorten the survey and reorder questions. We also used feedback from these calls to develop an optimal call‐back strategy to maximize family contacts.

Short‐Term Focused Engagement Via Discussions With Nurses

We also incorporated feedback from HHC nurses on 60 visits to ensure that the visit modifications were feasible to implement. HHC nurse feedback, which aligned with aim 1 data from families, highlighted the potential benefits of standardizing the transitional home visit to be more condition specific. The nurses also provided ongoing ad hoc feedback on other changes to the transitional home visit, which indicated both when tests were successful and when they were challenging to implement. The study team wanted to ensure that the nurses performing the visits were involved in the modification process.

ONGOING H2O WORK AND CONCLUSION

The third aim, with ongoing patient enrollment, involves a randomized trial to determine the efficacy of the revised transitional home visit compared with standard of care as measured by subsequent healthcare utilization and outcomes suggested in aim 1 and refined during aim 2, such as parental coping, stress, and confidence in care. We have engaged 1 parent to provide longitudinal feedback during regularly scheduled meetings.

We believe that our short‐term, focused engagement strategies have allowed integration of the invaluable perspective of families and other stakeholders into our research questions, intervention design, outcome measurement, and study execution. Our approach combined short‐term engagement from many stakeholders, blending qualitative techniques with rapid‐cycle implementation methods to quickly react to stakeholder input. Given the challenge of sustaining longitudinal engagement of families in research focused on acute care questions, and the tendency for many families interested in such engagement to be well versed in the care system due to chronic conditions, we propose this short‐term focused approach to include the unique viewpoints of families and patients whose care experience is confined to an acute period. Similarly, we propose that such an approach can efficiently include and rapidly react to input from other hard‐to‐engage key stakeholders such as field nurses.

Disclosures

This work was supported by the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute(HIS‐1306‐0081, SSS). The Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute had no role in the design, preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript or in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose. The authors report no potential conflicts of interest. The H2O study team members include the following: Katherine A. Auger, MD, MSc, JoAnne Bachus, BSN, Andrew F. Beck, MD, MPH, Monica L. Borell, BSN, Stephanie A. Brunswick, BS, Lenisa Chang, MA, PhD, Jennifer M. Gold, BSN, Judy A. Heilman, RN, Joseph A. Jabour, BS, Jane C. Khoury, PhD, Margo J. Moore, BSN, CCRP, Rita H. Pickler, PNP, PhD, Susan N. Sherman, DPA, Lauren G. Solan, MD, MEd, Angela M. Statile, MD, MEd, Heidi J. Sucharew, PhD, Karen P. Sullivan, BSN, Heather L. Tubbs‐Cooley, RN, PhD, Susan Wade‐Murphy, MSN, and Christine M. White, MD, MAT.

- , , , et al. Conceptual and practical foundations of patient engagement in research at the patient‐centered outcomes research institute. Qual Life Res. 2015;24(5):1033–1041.

- , . A review of parent participation engagement in child and family mental health treatment. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2015;18(2):133–150.

- , , , et al. Patient engagement in research: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:89.

- , , , . Pediatric hospital discharge interventions to reduce subsequent utilization: a systematic review. J Hosp Med. 2014;9:251–260.

- , , , , , . The Improvement Guide: A Practical Approach to Enhancing Organizational Performance. 2nd ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey‐Bass; 2009.

We believe that patients, families, and other stakeholders can provide meaningful contributions throughout the research process. Involvement of a diverse group of stakeholders is also encouraged by the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), which emphasizes research focused on patient‐ and family‐centered outcomes.[1] Patient and family engagement in healthcare, however, has generally focused on children and adults with chronic conditions.[1, 2] Engagement of families of children with serious acute illnesses is infrequent, and no studies have documented the feasibility or acceptability of different methods of family engagement.[3] Furthermore, stakeholders, such as nurses, may participate in study execution but rarely receive opportunities to inform the research process. In this Perspective, we describe our experiences with family engagement using a novel approach of serial, focused, short‐term engagement of stakeholders.

PRESTUDY WORK

In 2012, our institution introduced a nurse‐led transitional home‐visit program, an approach associated with reduced healthcare utilization in adults.[4] Patients hospitalized for acute illness received a 1‐time transitional home visit 24 to 72 hours after hospital discharge. We formed a multidisciplinary team, consisting of physicians, nurse scientists, home healthcare (HHC) nursing staff, patient families, and research staff to design a mixed‐methods study of the transitional home visit, which was funded by PCORI in 2014. This study, the Hospital‐to‐Home Outcomes (H2O) study, has 3 aims: (1) identify barriers to successful transitions home and outcomes of such transitions that are meaningful to families, (2) optimize the transitional home visits to address family‐identified barriers and outcomes, and (3) determine the efficacy of transitional home visits through a randomized control trial.

Two parents joined the study team during study development. Both had children hospitalized for acute illnesses, received a transitional home visit, and participated in a pilot focus group to provide insight into barriers families encounter during care transitions. These parents made valuable contributions, including recommending strategies for patient enrollment and retention. They also committed to participating in regularly scheduled study meetings and ad hoc discussions. However, feedback from the pilot focus group also highlighted a potential research engagement challenge; specifically, once the acute illness resolved, many families were primarily focused on the return to their normal routine and may not be easily engaged in research.

Based on family input, we included several mechanisms to engage caregivers of children with acute illness in the study design of H2O. Each design element allowed families and other stakeholders to contribute via short‐term focused approaches (eg, focus groups, phone surveys). These short‐term interactions drove iterative changes in study processes and approaches, including how to measure outcomes important to families. Rather than a small group of stakeholders making a series of recommendations over a long period of time, we had dozens of individual stakeholders make a few recommendations apiece that were quickly implemented and subsequently tested via feedback from the next few stakeholders (Figure 1).

PATIENT AND STAKEHOLDER ENGAGEMENT IN THE H2O STUDY

Having the short‐term, focused engagement strategy built into the study proved beneficial, when the 2 parents who were part of the initial design team and had planned to participate longitudinally were no longer able to participate. Over time, their circumstances changed. One parent moved out of the area to pursue a professional opportunity, and the second parent became increasingly difficult to reach and unable to join planned study meetings, a situation anticipated by the pilot focus group participants. These 2 instances illustrate challenges with long‐term engagement of families in research when the potential primary driver of their engagement, their child's acute illness, has resolved.

Short‐Term Focused Engagement Via Focus Groups With Parents/Caregivers

The first aim of the H2O study used 15 focus groups and semistructured interviews with parents/caregivers of recently discharged patients to identify barriers to and metrics of successful transitions of care from the hospital to home. The focus group question guide was developed by the research team and adapted as the focus groups progressed to incorporate new issues raised by participants. Analysis of focus group data revealed opportunities to improve the transitional home visit and identified outcomes important to families, including the need for emotional reassurance in the immediate period after discharge and the impact on family finances.

Short‐Term Focused Engagement Via Phone Calls With Parents/Caregivers

To continuously improve study processes and the transitional home visit during the second aim of H2O, we relied on short‐term focused engagement from 2 stakeholder groups, families and field nurses. We completed 107 phone calls with families who received a transitional home visit during the visit optimization period. These calls, completed 3 to 7 days after the visit, assessed parental perceptions of the effect of recent visit modifications through a standardized survey documented in an electronic database. These data were utilized in plan‐do‐study‐act cycles,[5] every 1 to 2 weeks, to determine if additional modifications to the visits were necessary. A cycle ended when the calls no longer provided new information. The questions asked on the calls also changed over time as different interventions were tested.

As an example, in aim 1, families highlighted the lack of clarity of discharge instructions, particularly regarding when and why to return for medical care. Thus, we developed condition‐specific red flag reminder cards to be shared at transitional home visits to help families remember and recognize concerning signs and symptoms and understand when additional evaluation may be warranted (Figure 2). Families in postvisit calls endorsed the concept of red flags, but sometimes preferred electronic rather than paper versions of the red flag cards to facilitate sharing with family members. Thus, we tested and refined texting the red flag information to families. Subsequent calls strongly supported this practice, so we will continue to use it during the third aim, the randomized trial of the transitional home visit.

The remaining calls (N=72) were completed 14 days after the visit to mirror the time frame for follow‐up calls in the planned randomized trial. These calls allowed us to test measurement of family‐identified outcomes and determine their usability in the trial. We used family feedback to shorten the survey and reorder questions. We also used feedback from these calls to develop an optimal call‐back strategy to maximize family contacts.

Short‐Term Focused Engagement Via Discussions With Nurses

We also incorporated feedback from HHC nurses on 60 visits to ensure that the visit modifications were feasible to implement. HHC nurse feedback, which aligned with aim 1 data from families, highlighted the potential benefits of standardizing the transitional home visit to be more condition specific. The nurses also provided ongoing ad hoc feedback on other changes to the transitional home visit, which indicated both when tests were successful and when they were challenging to implement. The study team wanted to ensure that the nurses performing the visits were involved in the modification process.

ONGOING H2O WORK AND CONCLUSION

The third aim, with ongoing patient enrollment, involves a randomized trial to determine the efficacy of the revised transitional home visit compared with standard of care as measured by subsequent healthcare utilization and outcomes suggested in aim 1 and refined during aim 2, such as parental coping, stress, and confidence in care. We have engaged 1 parent to provide longitudinal feedback during regularly scheduled meetings.

We believe that our short‐term, focused engagement strategies have allowed integration of the invaluable perspective of families and other stakeholders into our research questions, intervention design, outcome measurement, and study execution. Our approach combined short‐term engagement from many stakeholders, blending qualitative techniques with rapid‐cycle implementation methods to quickly react to stakeholder input. Given the challenge of sustaining longitudinal engagement of families in research focused on acute care questions, and the tendency for many families interested in such engagement to be well versed in the care system due to chronic conditions, we propose this short‐term focused approach to include the unique viewpoints of families and patients whose care experience is confined to an acute period. Similarly, we propose that such an approach can efficiently include and rapidly react to input from other hard‐to‐engage key stakeholders such as field nurses.

Disclosures

This work was supported by the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute(HIS‐1306‐0081, SSS). The Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute had no role in the design, preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript or in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose. The authors report no potential conflicts of interest. The H2O study team members include the following: Katherine A. Auger, MD, MSc, JoAnne Bachus, BSN, Andrew F. Beck, MD, MPH, Monica L. Borell, BSN, Stephanie A. Brunswick, BS, Lenisa Chang, MA, PhD, Jennifer M. Gold, BSN, Judy A. Heilman, RN, Joseph A. Jabour, BS, Jane C. Khoury, PhD, Margo J. Moore, BSN, CCRP, Rita H. Pickler, PNP, PhD, Susan N. Sherman, DPA, Lauren G. Solan, MD, MEd, Angela M. Statile, MD, MEd, Heidi J. Sucharew, PhD, Karen P. Sullivan, BSN, Heather L. Tubbs‐Cooley, RN, PhD, Susan Wade‐Murphy, MSN, and Christine M. White, MD, MAT.

We believe that patients, families, and other stakeholders can provide meaningful contributions throughout the research process. Involvement of a diverse group of stakeholders is also encouraged by the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), which emphasizes research focused on patient‐ and family‐centered outcomes.[1] Patient and family engagement in healthcare, however, has generally focused on children and adults with chronic conditions.[1, 2] Engagement of families of children with serious acute illnesses is infrequent, and no studies have documented the feasibility or acceptability of different methods of family engagement.[3] Furthermore, stakeholders, such as nurses, may participate in study execution but rarely receive opportunities to inform the research process. In this Perspective, we describe our experiences with family engagement using a novel approach of serial, focused, short‐term engagement of stakeholders.

PRESTUDY WORK

In 2012, our institution introduced a nurse‐led transitional home‐visit program, an approach associated with reduced healthcare utilization in adults.[4] Patients hospitalized for acute illness received a 1‐time transitional home visit 24 to 72 hours after hospital discharge. We formed a multidisciplinary team, consisting of physicians, nurse scientists, home healthcare (HHC) nursing staff, patient families, and research staff to design a mixed‐methods study of the transitional home visit, which was funded by PCORI in 2014. This study, the Hospital‐to‐Home Outcomes (H2O) study, has 3 aims: (1) identify barriers to successful transitions home and outcomes of such transitions that are meaningful to families, (2) optimize the transitional home visits to address family‐identified barriers and outcomes, and (3) determine the efficacy of transitional home visits through a randomized control trial.

Two parents joined the study team during study development. Both had children hospitalized for acute illnesses, received a transitional home visit, and participated in a pilot focus group to provide insight into barriers families encounter during care transitions. These parents made valuable contributions, including recommending strategies for patient enrollment and retention. They also committed to participating in regularly scheduled study meetings and ad hoc discussions. However, feedback from the pilot focus group also highlighted a potential research engagement challenge; specifically, once the acute illness resolved, many families were primarily focused on the return to their normal routine and may not be easily engaged in research.

Based on family input, we included several mechanisms to engage caregivers of children with acute illness in the study design of H2O. Each design element allowed families and other stakeholders to contribute via short‐term focused approaches (eg, focus groups, phone surveys). These short‐term interactions drove iterative changes in study processes and approaches, including how to measure outcomes important to families. Rather than a small group of stakeholders making a series of recommendations over a long period of time, we had dozens of individual stakeholders make a few recommendations apiece that were quickly implemented and subsequently tested via feedback from the next few stakeholders (Figure 1).

PATIENT AND STAKEHOLDER ENGAGEMENT IN THE H2O STUDY

Having the short‐term, focused engagement strategy built into the study proved beneficial, when the 2 parents who were part of the initial design team and had planned to participate longitudinally were no longer able to participate. Over time, their circumstances changed. One parent moved out of the area to pursue a professional opportunity, and the second parent became increasingly difficult to reach and unable to join planned study meetings, a situation anticipated by the pilot focus group participants. These 2 instances illustrate challenges with long‐term engagement of families in research when the potential primary driver of their engagement, their child's acute illness, has resolved.

Short‐Term Focused Engagement Via Focus Groups With Parents/Caregivers

The first aim of the H2O study used 15 focus groups and semistructured interviews with parents/caregivers of recently discharged patients to identify barriers to and metrics of successful transitions of care from the hospital to home. The focus group question guide was developed by the research team and adapted as the focus groups progressed to incorporate new issues raised by participants. Analysis of focus group data revealed opportunities to improve the transitional home visit and identified outcomes important to families, including the need for emotional reassurance in the immediate period after discharge and the impact on family finances.

Short‐Term Focused Engagement Via Phone Calls With Parents/Caregivers

To continuously improve study processes and the transitional home visit during the second aim of H2O, we relied on short‐term focused engagement from 2 stakeholder groups, families and field nurses. We completed 107 phone calls with families who received a transitional home visit during the visit optimization period. These calls, completed 3 to 7 days after the visit, assessed parental perceptions of the effect of recent visit modifications through a standardized survey documented in an electronic database. These data were utilized in plan‐do‐study‐act cycles,[5] every 1 to 2 weeks, to determine if additional modifications to the visits were necessary. A cycle ended when the calls no longer provided new information. The questions asked on the calls also changed over time as different interventions were tested.

As an example, in aim 1, families highlighted the lack of clarity of discharge instructions, particularly regarding when and why to return for medical care. Thus, we developed condition‐specific red flag reminder cards to be shared at transitional home visits to help families remember and recognize concerning signs and symptoms and understand when additional evaluation may be warranted (Figure 2). Families in postvisit calls endorsed the concept of red flags, but sometimes preferred electronic rather than paper versions of the red flag cards to facilitate sharing with family members. Thus, we tested and refined texting the red flag information to families. Subsequent calls strongly supported this practice, so we will continue to use it during the third aim, the randomized trial of the transitional home visit.

The remaining calls (N=72) were completed 14 days after the visit to mirror the time frame for follow‐up calls in the planned randomized trial. These calls allowed us to test measurement of family‐identified outcomes and determine their usability in the trial. We used family feedback to shorten the survey and reorder questions. We also used feedback from these calls to develop an optimal call‐back strategy to maximize family contacts.

Short‐Term Focused Engagement Via Discussions With Nurses

We also incorporated feedback from HHC nurses on 60 visits to ensure that the visit modifications were feasible to implement. HHC nurse feedback, which aligned with aim 1 data from families, highlighted the potential benefits of standardizing the transitional home visit to be more condition specific. The nurses also provided ongoing ad hoc feedback on other changes to the transitional home visit, which indicated both when tests were successful and when they were challenging to implement. The study team wanted to ensure that the nurses performing the visits were involved in the modification process.

ONGOING H2O WORK AND CONCLUSION

The third aim, with ongoing patient enrollment, involves a randomized trial to determine the efficacy of the revised transitional home visit compared with standard of care as measured by subsequent healthcare utilization and outcomes suggested in aim 1 and refined during aim 2, such as parental coping, stress, and confidence in care. We have engaged 1 parent to provide longitudinal feedback during regularly scheduled meetings.

We believe that our short‐term, focused engagement strategies have allowed integration of the invaluable perspective of families and other stakeholders into our research questions, intervention design, outcome measurement, and study execution. Our approach combined short‐term engagement from many stakeholders, blending qualitative techniques with rapid‐cycle implementation methods to quickly react to stakeholder input. Given the challenge of sustaining longitudinal engagement of families in research focused on acute care questions, and the tendency for many families interested in such engagement to be well versed in the care system due to chronic conditions, we propose this short‐term focused approach to include the unique viewpoints of families and patients whose care experience is confined to an acute period. Similarly, we propose that such an approach can efficiently include and rapidly react to input from other hard‐to‐engage key stakeholders such as field nurses.

Disclosures

This work was supported by the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute(HIS‐1306‐0081, SSS). The Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute had no role in the design, preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript or in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose. The authors report no potential conflicts of interest. The H2O study team members include the following: Katherine A. Auger, MD, MSc, JoAnne Bachus, BSN, Andrew F. Beck, MD, MPH, Monica L. Borell, BSN, Stephanie A. Brunswick, BS, Lenisa Chang, MA, PhD, Jennifer M. Gold, BSN, Judy A. Heilman, RN, Joseph A. Jabour, BS, Jane C. Khoury, PhD, Margo J. Moore, BSN, CCRP, Rita H. Pickler, PNP, PhD, Susan N. Sherman, DPA, Lauren G. Solan, MD, MEd, Angela M. Statile, MD, MEd, Heidi J. Sucharew, PhD, Karen P. Sullivan, BSN, Heather L. Tubbs‐Cooley, RN, PhD, Susan Wade‐Murphy, MSN, and Christine M. White, MD, MAT.

- , , , et al. Conceptual and practical foundations of patient engagement in research at the patient‐centered outcomes research institute. Qual Life Res. 2015;24(5):1033–1041.

- , . A review of parent participation engagement in child and family mental health treatment. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2015;18(2):133–150.

- , , , et al. Patient engagement in research: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:89.

- , , , . Pediatric hospital discharge interventions to reduce subsequent utilization: a systematic review. J Hosp Med. 2014;9:251–260.

- , , , , , . The Improvement Guide: A Practical Approach to Enhancing Organizational Performance. 2nd ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey‐Bass; 2009.

- , , , et al. Conceptual and practical foundations of patient engagement in research at the patient‐centered outcomes research institute. Qual Life Res. 2015;24(5):1033–1041.

- , . A review of parent participation engagement in child and family mental health treatment. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2015;18(2):133–150.

- , , , et al. Patient engagement in research: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:89.

- , , , . Pediatric hospital discharge interventions to reduce subsequent utilization: a systematic review. J Hosp Med. 2014;9:251–260.

- , , , , , . The Improvement Guide: A Practical Approach to Enhancing Organizational Performance. 2nd ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey‐Bass; 2009.