User login

In the flourishing metropolitan area of Atlanta, hospitalists and community-based physicians at Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta thrive within their niches, riding waves of opportunity fueled by the region’s burgeoning population. Jay Berkelhamer, MD, senior vice president of medical affairs at Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta calls his city “one of the most dynamic growth centers in the United States. Within 10 years we are estimated to have at least 150,000 more kids in Atlanta, leading to even greater opportunities for hospitalists and private practice primary care and specialty pediatricians.”

Two Hospitals, One system

Children’s Hospital of Atlanta’s hospitalist program is, in fact, two separate programs: one at Egleston, the other at Scottish Rite. The parent organization links the two and manages each hospital’s mission, structure, hiring, compensation, and outcomes.

—David Hall, MD

The six Egleston full-time equivalent hospitalists, or “cat herders,” as Corinne Taylor, MD, Egleston’s chief of medical affairs, describes them, are employees of Emory University Medical School. Most Egleston hospitalists are parents of young children and work four days a week, allowing them a balance of career and family life. Employed by the medical school and working at an academic medical center, they receive a salary, benefits, and other support services. Side by side with interns and residents, Egleston’s hospitalists see Atlanta’s sickest, frailest, and most at-risk children: the uninsured, underinsured immigrant and local population.

At Egleston the pediatric hospitalists are like their counterparts who treat adult patients in other settings. They deal with many patients with chronic conditions that lead to repeat hospitalizations.

“We see lots of ex-preemies with multiple problems such as asthma, seizures, cerebral palsy, and gastric problems,” says Dr. Taylor. “Some are ventilator-dependent and need lots of care.”

She relishes the clinical discipline that being a hospitalist at an academic medical center presents. “I do my homework every day and enjoy the stimulation of teaching our house officers,” explains Dr. Taylor. “Working with adult learners on the chronic conditions we manage and the cases with puzzling symptoms is exciting.”

Dr. Taylor’s boss is this hospitalist program’s founder, Joseph Snitzer, MD (see “Joseph Snitzer, MD: A hospital medicine pioneer”). Being hospital-based frees Dr. Snitzer to observe an endless parade of clinical challenges, including complex rheumatology cases, lupus, tumors, infected shunts, seizures, exotic infections, oncology diagnoses, and more.

“People call us from rural hospitals and private practices for help with diagnoses,” explains Dr. Snitzer. “We’re not smarter than anyone else. We just see a lot more than most other physicians.”

Scottish Rite

Across town at Scottish Rite, a nonprofit hospital, the hospitalists cope with the demands of a steady influx of new Atlantans. David Hall, MD, is Scottish Rite’s medical director. He was a former Egleston hospitalist and a private practitioner for 10 years in Baltimore before he relocated to Atlanta.

“We don’t have house officers, and there is a resident on call only one night a week,” says Dr. Hall. “Pediatricians in the community need to have their patients admitted 24/7, and we also have to admit from the emergency department at night. With our hospitalists taking calls at night and working all the next day, sometimes they would be on for 36 hours straight. As our service has grown, we’ve realized that this model was not sustainable.”

To reduce the burnout from their growing patient loads, the hospitalists changed their model. As of August 1, 2005, hospitalists at Scottish Rite began working either eight- or 12-hour shifts.

“Until we gain some experience with the shift system, we know we will struggle with continuity and handoffs,” adds Dr. Hall. Scottish Rite is also increasing its complement of moonlighting private practice pediatricians who want to keep their hospital skills current by covering the heavy workload.

Dr. Hall says recruiting new hospitalists isn’t a problem. Many local physicians want to do this work—especially right after residency. Comparing being a hospitalist with his 10 years in private practice, he says, “In my office practice I’d be sitting 20 feet away from a colleague, and there wasn’t much interaction. Now I’m learning something new every day and discussing interesting patients with other doctors. Building these ongoing relationships is great.”

Benefits, Culture, and More

The compensation and benefits packages at Egleston and Scottish Rite reflect that they are two separate hospitals in one system. Egleston’s hospitalists are employed by the medical school and receive a straight salary, with no incentive or at risk components. Scottish Rite’s hospitalists are hospital employees and have 20% of their salary at risk with productivity, quality improvement, and patient satisfaction incentives.

Although the different compensation systems may lead to discrepancies in pay, Dr. Berkelhamer explains that the policy of Children’s Hospital of Atlanta is to offer market-based salaries to all hospitalists. “Part of my job is to ensure that Dr. Snitzer and Dr. Hall are empowered to hire the physicians they want,” he says.

The hospitals have different corporate cultures as well. “The Scottish Rite group is very comfortable with lots of hands-on work while those at Egleston like to spend more time teaching,” says Dr. Berkelhamer.

Dr. Taylor, who trained with Dr. Snitzer and had a private practice in Atlanta for five years before becoming a full-time Egleston hospitalist in 1993, also acknowledges the different cultures at Egleston and Scottish Rite.

“We are two hospitals that come to the table and work together,” she observes. “Although we are in separate locations and may approach things differently, we practice the same type of medicine.”

Dr. Berkelhamer, who works with both sets of hospitalists, reinforces the observation that their clinical practices are consistent: “Surveys on patient and community physician satisfaction are the same, as are outcomes and productivity data.”

Special Issues for Both Hospitals

As part of a growing medical specialty in a dynamic region of the country, hospitalists at Children’s Hospital of Atlanta must confront a number of issues—some unique to them, others that reflect national trends. With different compensation and productivity systems, the two sets of hospitalists must collaborate to practice one brand of medicine.

An important formal step in their collaboration is the computerized medical and order entry system scheduled for spring 2006 implementation. The hospitalists are working together to develop clinical pathways and standardized orders based on their culling through best practices and evidence-based medicine guidelines. A newly appointed chief quality officer will keep the project on track.

Atlanta’s growth presents other issues for the hospitalists. With a constant influx of new community-based pediatricians Dr. Taylor finds that the hospitalists sometimes have trouble communicating with them to coordinate care.

“There are now at least 1,000 primary care and subspecialty pediatricians in Atlanta,” she says. “Trying to build trust and to track personal preferences with so many doctors is difficult. Fortunately we have electronic medical records so we can share important data with them.”

The hospitals’ social workers and case managers represent added glue to hold the communication together. Another of Atlanta’s challenges: It has only two medical schools from which to draw local hospitalists and other pediatricians, Emory University and the smaller Morehouse University. While not insurmountable, it means that most pediatricians practicing in the area must relocate to Atlanta.

What the Future Holds

And then there are issues that transcend Atlanta. Dr. Snitzer feels the national movement for hospitalists to become a specialty will happen sooner rather than later. In line with that movement, Children’s Hospital of Atlanta will have its first hospitalist fellowship in 2007. (For more information on pediatric hospital medicine fellowships, see “Pediatric Fellowship Offered,” below.)

For Dr. Hall, hospitalist compensation in a boomtown rankles. “People can’t really make money being hospitalists,” he explains. “Most need some subsidy to keep the programs going.”

The pay issues are being addressed, albeit slowly. Dr. Hall is encouraged by the campaign of pediatric intensivists to have coding and payment upgrades; he sees it as a template for higher hospitalist reimbursement schedules. “We only get paid for one visit a day, but we often see a patient several times a day,” he says. “Reimbursement should reflect what we really do.”

Both hospitals will have new buildings, each with 250 beds, more surgical suites, and expanded emergency departments by early 2007. That should lead to more hospitalist hiring—not surprising for a hospital that pioneered having inpatient physicians more than 20 years ago. TH

Writer Marlene Piturro is based in New York.

PEDIATRIC SPECIAL SECTION:

NEWS

Pediatric Fellowship Offered

Children’s Hospitalists of San Diego offers program

The Pediatric Hospitalist program at Children’s Hospital and Health Center of San Diego (CHHC) began in 1978. The current hospitalists are employed by Children’s Specialists of San Diego (CSSD), a 180-member pediatric-only specialty medical group. Inpatient care is provided for 75% of all general pediatric patients at the 233-bed tertiary care CHHC. Program consultation is offered at nearby Palomar Medical Center, a 23-bed unit within a larger 319-bed community hospital with a trauma center.

The hospitalists are the primary teaching faculty for the house staff and medical students who come from the University of California San Diego (UCSD), Balboa Naval Hospital, Pendleton Naval Medical Center, and Scripps Family Medicine. All hospitalists are board-certified pediatricians and have additional degrees or postresidency training, such as chief residency or fellowship experience.

Hospitalists fulfill many leadership roles in the hospital and community when not on service. A detailed list is available in a previous issue of The Hospitalist (Nov/Dec 2004;8(6):59-60). Current research includes an Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) safety grant on medication errors, a bronchiolitis clinical trial, juvenile justice research on hepatitis B, a Hispanic cultural competency grant from the California Endowment, spiratory syncytial virus immunoprophylaxis outcomes in a managed population, and primary care perceptions of pediatric dentistry. Thus the hospitalist program has a long history of strong commitment to children and the core aspects of pediatric hospital medicine.

The Fellowship

The CSSD Pediatric Hospitalist Fellowship Program goal is to train highly motivated pediatricians for careers in academic and clinical hospital medicine. Over a two-year period instruction is provided in clinical, advocacy, administrative, teaching, and research aspects of pediatric hospital medicine. Clinical education emphasizes inpatient acute care, including intensive care and emergency transport at the busy main campus at CHHC. Outpatient clinical care offers experiences in adolescent juvenile hall medicine, hospice, and child protection. The diverse clinical exposure, teaching from local and national leaders, and volume of patients ensure graduates of this program are well prepared for any clinical hospitalist position.

The staff gains administrative experience via both hospital and medical group quality improvement activities. This work is directed by the medical director for CSSD and the physician advisor for quality management for CHHC, both of whom are CSSD pediatric hospitalists. Skills in process improvement, continuous quality improvement, risk management, organizational management and leadership are honed during the fellowship. Opportunity exists to take courses through the American College of Physician Executives if the trainee desires a future in administrative hospitalist medicine.

Academics and teaching are a core value of the pediatric hospitalist service. The fellow participates in the monthly division journal club and internal case review. Daily teaching while on the clinical service includes bedside rounds, management rounds, and attending rounds. Pediatric hospitalists are the primary inpatient teaching staff and as such have a significant responsibility for daily house staff education. The fellow participates in noon conferences and other educational venues under the guidance of the director of inpatient teaching (also a pediatric hospitalist).

Advocacy skills are learned through experiences in the juvenile hall system, Center for Child Protection, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), and at the local and state level for children’s services funding. Under the leadership of the medical directors for the Center for Child Protection and the A.B. and Jessie Polinsky Center for Abused Children, the fellow participates in case review and observes expert child abuse testimony in court. Discussions with legislators in Sacramento focus upon protection of the California Children’s Services system, which supports critically ill state-funded children. The fellow learns AAP local and national structure, participating in conferences and chapter events.

Research is expected during this two-year fellowship program. Formal clinical research training is part of the first year curriculum of UCSD’s Clinical Research Enhancement through Supplemental Training (CREST) program. The first year of this two-year CREST program includes weekly classes covering epidemiology, patient-oriented research, health services research, and informatics. Those dedicated to completion of a master’s degree during the two-year program may integrate this training with a more intense curriculum schedule. A research project and mentor is chosen after the first quarter of the first year. Research may be in any area of pediatric hospitalist medicine. Research is presented at either Pediatric Academic Societies, Society of Hospital Medicine, or other similar forum upon completion.

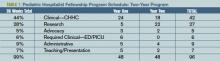

The schedule is flexible, but follows the template. (See Table 1, p. 30: “Pediatric Hospitalist Fellowship Program Schedule.”)

One fellowship position is offered every year, with application submissions accepted through Dec. 1, interviews granted Dec. 15-Feb. 1 and final selection by Feb. 15. You can obtain an application from the CSSD Web site “Fellowships” page (http://childrensspecialists. com/body.cfm?id=580) or by e-mailing Fellowship Coordinator Susan Stafford at sstafford@chsd.org.

PEDIATRIC SPECIAL SECTION:

IN THE LITERATURE

Retrospective Study Attempts Criteria for Diagnosing MAS

Reviews by Julia Simmons, MD

Ravelli A, Magni-Manzoni S, Pistorio A, et al. Preliminary diagnostic guidelines for macrophage activation syndrome complicating systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J Pediatr. 2005;146(5):598-604.

Macrophage activating syndrome (MAS) is a complication of connective tissue disorders, most often associated with active systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis (S-JIA). It is a rare disorder and the exact incidence is unknown. It is characterized by uncontrolled activation and proliferation of T-lymphocytes and macrophages. If not recognized and treated aggressively, MAS can be life threatening.

In this article, the authors’ purpose was to review the available clinical, laboratory, and histopathologic data in patients with active S-JIA and in those with active S-JIA complicated by MAS. The goal was to develop criteria to diagnose MAS.

The retrospective study was designed using the classification, criteria approach. The index cases included patients with MAS complicating S-JIA. The “confusable” condition was active S-JIA. There were 74 patients in the index cases. Seventeen of the cases were observed at the authors’ institution. These patients were diagnosed with S-JIA using the International League of Association for Rheumatology criteria. They were identified using a database search. Fifty-seven of the cases were obtained from a Medline search. Of these 74 patients, eight were disqualified because they did not meet the definition of S-JIA, and 11 were excluded because of insufficient data. The control group contained 37 patients observed at the authors’ sites. The sensitivity rate, specificity rate, area under receiver operating characteristic curve, and diagnostic odds ratio were applied to the data to differentiate MAS complicating S-JIA from S-JIA.

The study results found hemorrhages and central nervous dysfunction were the strongest clinical discriminating factors. The strongest laboratory discriminators included thrombocytopenia, leukopenia, elevated aspartate aminotransferase, and hypofibrinogenemia. Histopathological criterion included evidence of macrophage hemophagocytosis in the bone marrow aspirate. Other useful discriminators included hypertriglyceridemia, elevated ferritin, hepatomegaly, hand hyponatremia. Final guidelines were developed after analyzing the statistics and determining the clinical importance: “The diagnosis of MAS requires the presence of any two or more laboratory criteria or of any two or three or more clinical and/or laboratory criteria. A bone marrow aspirate for the demonstration of hemophagocytosis may be required only in doubtful cases.”

In summary, MAS complicating S-JIA is a disorder without concrete diagnostic criteria. The authors have performed preliminary studies to diagnose MAS. They appropriately recognized the need for prospective larger clinical studies.

HNL Helps Distinguish Infections

Fjaertoft G, Foucard T, Xu S, et al. Human neutrophil lipocalin (HNL) as a diagnostic tool in children with acute infections: a study of the kinetics. Acta Pediatrica costarricense. 2005;94:661-666.

In pediatrics, the clinician is often faced with the diagnostic challenge of differentiating a bacterial infectious process from a viral infection. History, physical exam, and laboratory data make the distinction. In this article, the authors’ purpose was to assess the kinetics of HNL with viral and bacterial infections. Further, they assess the response of HNL when the infection is treated with antibiotics. The response of HNL is compared with that of C-reactive protein.

In the study, 92 patients with a median age of 26 months were hospitalized because they required systemic antibiotics or because of the severity of their medical condition. Upon admission and on hospital days one, two, and three, the C-reactive protein, white blood cell count with differential, and HNL were measured. The patients were retrospectively classified into five groups: true bacterial infection (n=28), true viral infection (n=4), suspected bacterial infection (n=18), suspected viral (n=34), and other.

A true bacterial infection required bacterial isolation from blood, urine, or cerebrospinal fluid culture, or radiographic demonstration of pneumonia. Patients were classified as having a suspected bacterial infection if they had a nonspecific diagnosis, but an elevated C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate. A true viral infection required isolation of a virus. If a patient did not meet any of the above criteria, the person was classified as having a suspected viral infection. Those patients in the “other” group were diagnosed with Kawasaki disease, Borrelia meningitis, and one undiagnosed patient. The patients were classified using history, exam, and laboratory values including white blood cell count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, and cultures. HNL values were not used in the classification.

The results demonstrated that both C-reactive protein and HNL are elevated with true bacterial infections compared with viral illnesses. Neither C-reactive protein nor HNL were significantly different in true bacterial infections versus suspected bacterial infections. The optimal cut-off for C-reactive protein was 59 mg/L with 93% sensitivity and 68% specificity. The optimal cutoff for HNL was 217 micrograms/L with 90% sensitivity and 74% specificity. In patients with true bacterial infections, HNL was highest at admission and decreased one day after admission. In contrast, the C-reactive protein values were similar on the day of admission and on hospital day one. C-reactive protein decreased significantly on days two and three of hospitalization. After hospital day one, HNL was elevated in only 11% of patients with true bacterial infection in contrast to 83% patients with elevated C-reactive protein.

In summary, HNL may be a useful marker to distinguish bacterial and viral illnesses. In comparison with C-reactive protein, it normalizes more rapidly after appropriate antibiotic therapy is initiated. In the future, HNL may be a useful marker in monitoring the response to antibiotic therapy.

CEDKA in Peds

Lawrence SE, Cummings EA, Gaboury I, et al. Population-based study of incidence and risk factors for cerebral edema in pediatric diabetic ketoacidosis. . 2005;146:688-692.

New onset insulin dependent diabetes mellitus is complicated by diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) in 15% to 67% of patients. The incidence of cerebral edema in diabetic ketoacidosis (CEDKA) has been reported as 0.4-3.1. In the article, the authors seek to determine the incidence, outcome, and risk factors for cerebral edema in DKA in patients younger than 16.

The study was case-controlled with an active Canadian surveillance study. The authors surveyed pediatricians for a two-year period. During this time in Canada, all physicians were requested to submit reports monthly on patients with CEDKA younger than 16.

Thirteen cases were identified and the incidence of CEDKA was 0.51%. Overall mortality from cerebral edema was 0.15%. Increased blood urea nitrogen, degree of dehydration, hyperglycemia, and lower initial bicarbonate were associated with CEDKA. TH

In the flourishing metropolitan area of Atlanta, hospitalists and community-based physicians at Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta thrive within their niches, riding waves of opportunity fueled by the region’s burgeoning population. Jay Berkelhamer, MD, senior vice president of medical affairs at Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta calls his city “one of the most dynamic growth centers in the United States. Within 10 years we are estimated to have at least 150,000 more kids in Atlanta, leading to even greater opportunities for hospitalists and private practice primary care and specialty pediatricians.”

Two Hospitals, One system

Children’s Hospital of Atlanta’s hospitalist program is, in fact, two separate programs: one at Egleston, the other at Scottish Rite. The parent organization links the two and manages each hospital’s mission, structure, hiring, compensation, and outcomes.

—David Hall, MD

The six Egleston full-time equivalent hospitalists, or “cat herders,” as Corinne Taylor, MD, Egleston’s chief of medical affairs, describes them, are employees of Emory University Medical School. Most Egleston hospitalists are parents of young children and work four days a week, allowing them a balance of career and family life. Employed by the medical school and working at an academic medical center, they receive a salary, benefits, and other support services. Side by side with interns and residents, Egleston’s hospitalists see Atlanta’s sickest, frailest, and most at-risk children: the uninsured, underinsured immigrant and local population.

At Egleston the pediatric hospitalists are like their counterparts who treat adult patients in other settings. They deal with many patients with chronic conditions that lead to repeat hospitalizations.

“We see lots of ex-preemies with multiple problems such as asthma, seizures, cerebral palsy, and gastric problems,” says Dr. Taylor. “Some are ventilator-dependent and need lots of care.”

She relishes the clinical discipline that being a hospitalist at an academic medical center presents. “I do my homework every day and enjoy the stimulation of teaching our house officers,” explains Dr. Taylor. “Working with adult learners on the chronic conditions we manage and the cases with puzzling symptoms is exciting.”

Dr. Taylor’s boss is this hospitalist program’s founder, Joseph Snitzer, MD (see “Joseph Snitzer, MD: A hospital medicine pioneer”). Being hospital-based frees Dr. Snitzer to observe an endless parade of clinical challenges, including complex rheumatology cases, lupus, tumors, infected shunts, seizures, exotic infections, oncology diagnoses, and more.

“People call us from rural hospitals and private practices for help with diagnoses,” explains Dr. Snitzer. “We’re not smarter than anyone else. We just see a lot more than most other physicians.”

Scottish Rite

Across town at Scottish Rite, a nonprofit hospital, the hospitalists cope with the demands of a steady influx of new Atlantans. David Hall, MD, is Scottish Rite’s medical director. He was a former Egleston hospitalist and a private practitioner for 10 years in Baltimore before he relocated to Atlanta.

“We don’t have house officers, and there is a resident on call only one night a week,” says Dr. Hall. “Pediatricians in the community need to have their patients admitted 24/7, and we also have to admit from the emergency department at night. With our hospitalists taking calls at night and working all the next day, sometimes they would be on for 36 hours straight. As our service has grown, we’ve realized that this model was not sustainable.”

To reduce the burnout from their growing patient loads, the hospitalists changed their model. As of August 1, 2005, hospitalists at Scottish Rite began working either eight- or 12-hour shifts.

“Until we gain some experience with the shift system, we know we will struggle with continuity and handoffs,” adds Dr. Hall. Scottish Rite is also increasing its complement of moonlighting private practice pediatricians who want to keep their hospital skills current by covering the heavy workload.

Dr. Hall says recruiting new hospitalists isn’t a problem. Many local physicians want to do this work—especially right after residency. Comparing being a hospitalist with his 10 years in private practice, he says, “In my office practice I’d be sitting 20 feet away from a colleague, and there wasn’t much interaction. Now I’m learning something new every day and discussing interesting patients with other doctors. Building these ongoing relationships is great.”

Benefits, Culture, and More

The compensation and benefits packages at Egleston and Scottish Rite reflect that they are two separate hospitals in one system. Egleston’s hospitalists are employed by the medical school and receive a straight salary, with no incentive or at risk components. Scottish Rite’s hospitalists are hospital employees and have 20% of their salary at risk with productivity, quality improvement, and patient satisfaction incentives.

Although the different compensation systems may lead to discrepancies in pay, Dr. Berkelhamer explains that the policy of Children’s Hospital of Atlanta is to offer market-based salaries to all hospitalists. “Part of my job is to ensure that Dr. Snitzer and Dr. Hall are empowered to hire the physicians they want,” he says.

The hospitals have different corporate cultures as well. “The Scottish Rite group is very comfortable with lots of hands-on work while those at Egleston like to spend more time teaching,” says Dr. Berkelhamer.

Dr. Taylor, who trained with Dr. Snitzer and had a private practice in Atlanta for five years before becoming a full-time Egleston hospitalist in 1993, also acknowledges the different cultures at Egleston and Scottish Rite.

“We are two hospitals that come to the table and work together,” she observes. “Although we are in separate locations and may approach things differently, we practice the same type of medicine.”

Dr. Berkelhamer, who works with both sets of hospitalists, reinforces the observation that their clinical practices are consistent: “Surveys on patient and community physician satisfaction are the same, as are outcomes and productivity data.”

Special Issues for Both Hospitals

As part of a growing medical specialty in a dynamic region of the country, hospitalists at Children’s Hospital of Atlanta must confront a number of issues—some unique to them, others that reflect national trends. With different compensation and productivity systems, the two sets of hospitalists must collaborate to practice one brand of medicine.

An important formal step in their collaboration is the computerized medical and order entry system scheduled for spring 2006 implementation. The hospitalists are working together to develop clinical pathways and standardized orders based on their culling through best practices and evidence-based medicine guidelines. A newly appointed chief quality officer will keep the project on track.

Atlanta’s growth presents other issues for the hospitalists. With a constant influx of new community-based pediatricians Dr. Taylor finds that the hospitalists sometimes have trouble communicating with them to coordinate care.

“There are now at least 1,000 primary care and subspecialty pediatricians in Atlanta,” she says. “Trying to build trust and to track personal preferences with so many doctors is difficult. Fortunately we have electronic medical records so we can share important data with them.”

The hospitals’ social workers and case managers represent added glue to hold the communication together. Another of Atlanta’s challenges: It has only two medical schools from which to draw local hospitalists and other pediatricians, Emory University and the smaller Morehouse University. While not insurmountable, it means that most pediatricians practicing in the area must relocate to Atlanta.

What the Future Holds

And then there are issues that transcend Atlanta. Dr. Snitzer feels the national movement for hospitalists to become a specialty will happen sooner rather than later. In line with that movement, Children’s Hospital of Atlanta will have its first hospitalist fellowship in 2007. (For more information on pediatric hospital medicine fellowships, see “Pediatric Fellowship Offered,” below.)

For Dr. Hall, hospitalist compensation in a boomtown rankles. “People can’t really make money being hospitalists,” he explains. “Most need some subsidy to keep the programs going.”

The pay issues are being addressed, albeit slowly. Dr. Hall is encouraged by the campaign of pediatric intensivists to have coding and payment upgrades; he sees it as a template for higher hospitalist reimbursement schedules. “We only get paid for one visit a day, but we often see a patient several times a day,” he says. “Reimbursement should reflect what we really do.”

Both hospitals will have new buildings, each with 250 beds, more surgical suites, and expanded emergency departments by early 2007. That should lead to more hospitalist hiring—not surprising for a hospital that pioneered having inpatient physicians more than 20 years ago. TH

Writer Marlene Piturro is based in New York.

PEDIATRIC SPECIAL SECTION:

NEWS

Pediatric Fellowship Offered

Children’s Hospitalists of San Diego offers program

The Pediatric Hospitalist program at Children’s Hospital and Health Center of San Diego (CHHC) began in 1978. The current hospitalists are employed by Children’s Specialists of San Diego (CSSD), a 180-member pediatric-only specialty medical group. Inpatient care is provided for 75% of all general pediatric patients at the 233-bed tertiary care CHHC. Program consultation is offered at nearby Palomar Medical Center, a 23-bed unit within a larger 319-bed community hospital with a trauma center.

The hospitalists are the primary teaching faculty for the house staff and medical students who come from the University of California San Diego (UCSD), Balboa Naval Hospital, Pendleton Naval Medical Center, and Scripps Family Medicine. All hospitalists are board-certified pediatricians and have additional degrees or postresidency training, such as chief residency or fellowship experience.

Hospitalists fulfill many leadership roles in the hospital and community when not on service. A detailed list is available in a previous issue of The Hospitalist (Nov/Dec 2004;8(6):59-60). Current research includes an Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) safety grant on medication errors, a bronchiolitis clinical trial, juvenile justice research on hepatitis B, a Hispanic cultural competency grant from the California Endowment, spiratory syncytial virus immunoprophylaxis outcomes in a managed population, and primary care perceptions of pediatric dentistry. Thus the hospitalist program has a long history of strong commitment to children and the core aspects of pediatric hospital medicine.

The Fellowship

The CSSD Pediatric Hospitalist Fellowship Program goal is to train highly motivated pediatricians for careers in academic and clinical hospital medicine. Over a two-year period instruction is provided in clinical, advocacy, administrative, teaching, and research aspects of pediatric hospital medicine. Clinical education emphasizes inpatient acute care, including intensive care and emergency transport at the busy main campus at CHHC. Outpatient clinical care offers experiences in adolescent juvenile hall medicine, hospice, and child protection. The diverse clinical exposure, teaching from local and national leaders, and volume of patients ensure graduates of this program are well prepared for any clinical hospitalist position.

The staff gains administrative experience via both hospital and medical group quality improvement activities. This work is directed by the medical director for CSSD and the physician advisor for quality management for CHHC, both of whom are CSSD pediatric hospitalists. Skills in process improvement, continuous quality improvement, risk management, organizational management and leadership are honed during the fellowship. Opportunity exists to take courses through the American College of Physician Executives if the trainee desires a future in administrative hospitalist medicine.

Academics and teaching are a core value of the pediatric hospitalist service. The fellow participates in the monthly division journal club and internal case review. Daily teaching while on the clinical service includes bedside rounds, management rounds, and attending rounds. Pediatric hospitalists are the primary inpatient teaching staff and as such have a significant responsibility for daily house staff education. The fellow participates in noon conferences and other educational venues under the guidance of the director of inpatient teaching (also a pediatric hospitalist).

Advocacy skills are learned through experiences in the juvenile hall system, Center for Child Protection, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), and at the local and state level for children’s services funding. Under the leadership of the medical directors for the Center for Child Protection and the A.B. and Jessie Polinsky Center for Abused Children, the fellow participates in case review and observes expert child abuse testimony in court. Discussions with legislators in Sacramento focus upon protection of the California Children’s Services system, which supports critically ill state-funded children. The fellow learns AAP local and national structure, participating in conferences and chapter events.

Research is expected during this two-year fellowship program. Formal clinical research training is part of the first year curriculum of UCSD’s Clinical Research Enhancement through Supplemental Training (CREST) program. The first year of this two-year CREST program includes weekly classes covering epidemiology, patient-oriented research, health services research, and informatics. Those dedicated to completion of a master’s degree during the two-year program may integrate this training with a more intense curriculum schedule. A research project and mentor is chosen after the first quarter of the first year. Research may be in any area of pediatric hospitalist medicine. Research is presented at either Pediatric Academic Societies, Society of Hospital Medicine, or other similar forum upon completion.

The schedule is flexible, but follows the template. (See Table 1, p. 30: “Pediatric Hospitalist Fellowship Program Schedule.”)

One fellowship position is offered every year, with application submissions accepted through Dec. 1, interviews granted Dec. 15-Feb. 1 and final selection by Feb. 15. You can obtain an application from the CSSD Web site “Fellowships” page (http://childrensspecialists. com/body.cfm?id=580) or by e-mailing Fellowship Coordinator Susan Stafford at sstafford@chsd.org.

PEDIATRIC SPECIAL SECTION:

IN THE LITERATURE

Retrospective Study Attempts Criteria for Diagnosing MAS

Reviews by Julia Simmons, MD

Ravelli A, Magni-Manzoni S, Pistorio A, et al. Preliminary diagnostic guidelines for macrophage activation syndrome complicating systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J Pediatr. 2005;146(5):598-604.

Macrophage activating syndrome (MAS) is a complication of connective tissue disorders, most often associated with active systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis (S-JIA). It is a rare disorder and the exact incidence is unknown. It is characterized by uncontrolled activation and proliferation of T-lymphocytes and macrophages. If not recognized and treated aggressively, MAS can be life threatening.

In this article, the authors’ purpose was to review the available clinical, laboratory, and histopathologic data in patients with active S-JIA and in those with active S-JIA complicated by MAS. The goal was to develop criteria to diagnose MAS.

The retrospective study was designed using the classification, criteria approach. The index cases included patients with MAS complicating S-JIA. The “confusable” condition was active S-JIA. There were 74 patients in the index cases. Seventeen of the cases were observed at the authors’ institution. These patients were diagnosed with S-JIA using the International League of Association for Rheumatology criteria. They were identified using a database search. Fifty-seven of the cases were obtained from a Medline search. Of these 74 patients, eight were disqualified because they did not meet the definition of S-JIA, and 11 were excluded because of insufficient data. The control group contained 37 patients observed at the authors’ sites. The sensitivity rate, specificity rate, area under receiver operating characteristic curve, and diagnostic odds ratio were applied to the data to differentiate MAS complicating S-JIA from S-JIA.

The study results found hemorrhages and central nervous dysfunction were the strongest clinical discriminating factors. The strongest laboratory discriminators included thrombocytopenia, leukopenia, elevated aspartate aminotransferase, and hypofibrinogenemia. Histopathological criterion included evidence of macrophage hemophagocytosis in the bone marrow aspirate. Other useful discriminators included hypertriglyceridemia, elevated ferritin, hepatomegaly, hand hyponatremia. Final guidelines were developed after analyzing the statistics and determining the clinical importance: “The diagnosis of MAS requires the presence of any two or more laboratory criteria or of any two or three or more clinical and/or laboratory criteria. A bone marrow aspirate for the demonstration of hemophagocytosis may be required only in doubtful cases.”

In summary, MAS complicating S-JIA is a disorder without concrete diagnostic criteria. The authors have performed preliminary studies to diagnose MAS. They appropriately recognized the need for prospective larger clinical studies.

HNL Helps Distinguish Infections

Fjaertoft G, Foucard T, Xu S, et al. Human neutrophil lipocalin (HNL) as a diagnostic tool in children with acute infections: a study of the kinetics. Acta Pediatrica costarricense. 2005;94:661-666.

In pediatrics, the clinician is often faced with the diagnostic challenge of differentiating a bacterial infectious process from a viral infection. History, physical exam, and laboratory data make the distinction. In this article, the authors’ purpose was to assess the kinetics of HNL with viral and bacterial infections. Further, they assess the response of HNL when the infection is treated with antibiotics. The response of HNL is compared with that of C-reactive protein.

In the study, 92 patients with a median age of 26 months were hospitalized because they required systemic antibiotics or because of the severity of their medical condition. Upon admission and on hospital days one, two, and three, the C-reactive protein, white blood cell count with differential, and HNL were measured. The patients were retrospectively classified into five groups: true bacterial infection (n=28), true viral infection (n=4), suspected bacterial infection (n=18), suspected viral (n=34), and other.

A true bacterial infection required bacterial isolation from blood, urine, or cerebrospinal fluid culture, or radiographic demonstration of pneumonia. Patients were classified as having a suspected bacterial infection if they had a nonspecific diagnosis, but an elevated C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate. A true viral infection required isolation of a virus. If a patient did not meet any of the above criteria, the person was classified as having a suspected viral infection. Those patients in the “other” group were diagnosed with Kawasaki disease, Borrelia meningitis, and one undiagnosed patient. The patients were classified using history, exam, and laboratory values including white blood cell count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, and cultures. HNL values were not used in the classification.

The results demonstrated that both C-reactive protein and HNL are elevated with true bacterial infections compared with viral illnesses. Neither C-reactive protein nor HNL were significantly different in true bacterial infections versus suspected bacterial infections. The optimal cut-off for C-reactive protein was 59 mg/L with 93% sensitivity and 68% specificity. The optimal cutoff for HNL was 217 micrograms/L with 90% sensitivity and 74% specificity. In patients with true bacterial infections, HNL was highest at admission and decreased one day after admission. In contrast, the C-reactive protein values were similar on the day of admission and on hospital day one. C-reactive protein decreased significantly on days two and three of hospitalization. After hospital day one, HNL was elevated in only 11% of patients with true bacterial infection in contrast to 83% patients with elevated C-reactive protein.

In summary, HNL may be a useful marker to distinguish bacterial and viral illnesses. In comparison with C-reactive protein, it normalizes more rapidly after appropriate antibiotic therapy is initiated. In the future, HNL may be a useful marker in monitoring the response to antibiotic therapy.

CEDKA in Peds

Lawrence SE, Cummings EA, Gaboury I, et al. Population-based study of incidence and risk factors for cerebral edema in pediatric diabetic ketoacidosis. . 2005;146:688-692.

New onset insulin dependent diabetes mellitus is complicated by diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) in 15% to 67% of patients. The incidence of cerebral edema in diabetic ketoacidosis (CEDKA) has been reported as 0.4-3.1. In the article, the authors seek to determine the incidence, outcome, and risk factors for cerebral edema in DKA in patients younger than 16.

The study was case-controlled with an active Canadian surveillance study. The authors surveyed pediatricians for a two-year period. During this time in Canada, all physicians were requested to submit reports monthly on patients with CEDKA younger than 16.

Thirteen cases were identified and the incidence of CEDKA was 0.51%. Overall mortality from cerebral edema was 0.15%. Increased blood urea nitrogen, degree of dehydration, hyperglycemia, and lower initial bicarbonate were associated with CEDKA. TH

In the flourishing metropolitan area of Atlanta, hospitalists and community-based physicians at Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta thrive within their niches, riding waves of opportunity fueled by the region’s burgeoning population. Jay Berkelhamer, MD, senior vice president of medical affairs at Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta calls his city “one of the most dynamic growth centers in the United States. Within 10 years we are estimated to have at least 150,000 more kids in Atlanta, leading to even greater opportunities for hospitalists and private practice primary care and specialty pediatricians.”

Two Hospitals, One system

Children’s Hospital of Atlanta’s hospitalist program is, in fact, two separate programs: one at Egleston, the other at Scottish Rite. The parent organization links the two and manages each hospital’s mission, structure, hiring, compensation, and outcomes.

—David Hall, MD

The six Egleston full-time equivalent hospitalists, or “cat herders,” as Corinne Taylor, MD, Egleston’s chief of medical affairs, describes them, are employees of Emory University Medical School. Most Egleston hospitalists are parents of young children and work four days a week, allowing them a balance of career and family life. Employed by the medical school and working at an academic medical center, they receive a salary, benefits, and other support services. Side by side with interns and residents, Egleston’s hospitalists see Atlanta’s sickest, frailest, and most at-risk children: the uninsured, underinsured immigrant and local population.

At Egleston the pediatric hospitalists are like their counterparts who treat adult patients in other settings. They deal with many patients with chronic conditions that lead to repeat hospitalizations.

“We see lots of ex-preemies with multiple problems such as asthma, seizures, cerebral palsy, and gastric problems,” says Dr. Taylor. “Some are ventilator-dependent and need lots of care.”

She relishes the clinical discipline that being a hospitalist at an academic medical center presents. “I do my homework every day and enjoy the stimulation of teaching our house officers,” explains Dr. Taylor. “Working with adult learners on the chronic conditions we manage and the cases with puzzling symptoms is exciting.”

Dr. Taylor’s boss is this hospitalist program’s founder, Joseph Snitzer, MD (see “Joseph Snitzer, MD: A hospital medicine pioneer”). Being hospital-based frees Dr. Snitzer to observe an endless parade of clinical challenges, including complex rheumatology cases, lupus, tumors, infected shunts, seizures, exotic infections, oncology diagnoses, and more.

“People call us from rural hospitals and private practices for help with diagnoses,” explains Dr. Snitzer. “We’re not smarter than anyone else. We just see a lot more than most other physicians.”

Scottish Rite

Across town at Scottish Rite, a nonprofit hospital, the hospitalists cope with the demands of a steady influx of new Atlantans. David Hall, MD, is Scottish Rite’s medical director. He was a former Egleston hospitalist and a private practitioner for 10 years in Baltimore before he relocated to Atlanta.

“We don’t have house officers, and there is a resident on call only one night a week,” says Dr. Hall. “Pediatricians in the community need to have their patients admitted 24/7, and we also have to admit from the emergency department at night. With our hospitalists taking calls at night and working all the next day, sometimes they would be on for 36 hours straight. As our service has grown, we’ve realized that this model was not sustainable.”

To reduce the burnout from their growing patient loads, the hospitalists changed their model. As of August 1, 2005, hospitalists at Scottish Rite began working either eight- or 12-hour shifts.

“Until we gain some experience with the shift system, we know we will struggle with continuity and handoffs,” adds Dr. Hall. Scottish Rite is also increasing its complement of moonlighting private practice pediatricians who want to keep their hospital skills current by covering the heavy workload.

Dr. Hall says recruiting new hospitalists isn’t a problem. Many local physicians want to do this work—especially right after residency. Comparing being a hospitalist with his 10 years in private practice, he says, “In my office practice I’d be sitting 20 feet away from a colleague, and there wasn’t much interaction. Now I’m learning something new every day and discussing interesting patients with other doctors. Building these ongoing relationships is great.”

Benefits, Culture, and More

The compensation and benefits packages at Egleston and Scottish Rite reflect that they are two separate hospitals in one system. Egleston’s hospitalists are employed by the medical school and receive a straight salary, with no incentive or at risk components. Scottish Rite’s hospitalists are hospital employees and have 20% of their salary at risk with productivity, quality improvement, and patient satisfaction incentives.

Although the different compensation systems may lead to discrepancies in pay, Dr. Berkelhamer explains that the policy of Children’s Hospital of Atlanta is to offer market-based salaries to all hospitalists. “Part of my job is to ensure that Dr. Snitzer and Dr. Hall are empowered to hire the physicians they want,” he says.

The hospitals have different corporate cultures as well. “The Scottish Rite group is very comfortable with lots of hands-on work while those at Egleston like to spend more time teaching,” says Dr. Berkelhamer.

Dr. Taylor, who trained with Dr. Snitzer and had a private practice in Atlanta for five years before becoming a full-time Egleston hospitalist in 1993, also acknowledges the different cultures at Egleston and Scottish Rite.

“We are two hospitals that come to the table and work together,” she observes. “Although we are in separate locations and may approach things differently, we practice the same type of medicine.”

Dr. Berkelhamer, who works with both sets of hospitalists, reinforces the observation that their clinical practices are consistent: “Surveys on patient and community physician satisfaction are the same, as are outcomes and productivity data.”

Special Issues for Both Hospitals

As part of a growing medical specialty in a dynamic region of the country, hospitalists at Children’s Hospital of Atlanta must confront a number of issues—some unique to them, others that reflect national trends. With different compensation and productivity systems, the two sets of hospitalists must collaborate to practice one brand of medicine.

An important formal step in their collaboration is the computerized medical and order entry system scheduled for spring 2006 implementation. The hospitalists are working together to develop clinical pathways and standardized orders based on their culling through best practices and evidence-based medicine guidelines. A newly appointed chief quality officer will keep the project on track.

Atlanta’s growth presents other issues for the hospitalists. With a constant influx of new community-based pediatricians Dr. Taylor finds that the hospitalists sometimes have trouble communicating with them to coordinate care.

“There are now at least 1,000 primary care and subspecialty pediatricians in Atlanta,” she says. “Trying to build trust and to track personal preferences with so many doctors is difficult. Fortunately we have electronic medical records so we can share important data with them.”

The hospitals’ social workers and case managers represent added glue to hold the communication together. Another of Atlanta’s challenges: It has only two medical schools from which to draw local hospitalists and other pediatricians, Emory University and the smaller Morehouse University. While not insurmountable, it means that most pediatricians practicing in the area must relocate to Atlanta.

What the Future Holds

And then there are issues that transcend Atlanta. Dr. Snitzer feels the national movement for hospitalists to become a specialty will happen sooner rather than later. In line with that movement, Children’s Hospital of Atlanta will have its first hospitalist fellowship in 2007. (For more information on pediatric hospital medicine fellowships, see “Pediatric Fellowship Offered,” below.)

For Dr. Hall, hospitalist compensation in a boomtown rankles. “People can’t really make money being hospitalists,” he explains. “Most need some subsidy to keep the programs going.”

The pay issues are being addressed, albeit slowly. Dr. Hall is encouraged by the campaign of pediatric intensivists to have coding and payment upgrades; he sees it as a template for higher hospitalist reimbursement schedules. “We only get paid for one visit a day, but we often see a patient several times a day,” he says. “Reimbursement should reflect what we really do.”

Both hospitals will have new buildings, each with 250 beds, more surgical suites, and expanded emergency departments by early 2007. That should lead to more hospitalist hiring—not surprising for a hospital that pioneered having inpatient physicians more than 20 years ago. TH

Writer Marlene Piturro is based in New York.

PEDIATRIC SPECIAL SECTION:

NEWS

Pediatric Fellowship Offered

Children’s Hospitalists of San Diego offers program

The Pediatric Hospitalist program at Children’s Hospital and Health Center of San Diego (CHHC) began in 1978. The current hospitalists are employed by Children’s Specialists of San Diego (CSSD), a 180-member pediatric-only specialty medical group. Inpatient care is provided for 75% of all general pediatric patients at the 233-bed tertiary care CHHC. Program consultation is offered at nearby Palomar Medical Center, a 23-bed unit within a larger 319-bed community hospital with a trauma center.

The hospitalists are the primary teaching faculty for the house staff and medical students who come from the University of California San Diego (UCSD), Balboa Naval Hospital, Pendleton Naval Medical Center, and Scripps Family Medicine. All hospitalists are board-certified pediatricians and have additional degrees or postresidency training, such as chief residency or fellowship experience.

Hospitalists fulfill many leadership roles in the hospital and community when not on service. A detailed list is available in a previous issue of The Hospitalist (Nov/Dec 2004;8(6):59-60). Current research includes an Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) safety grant on medication errors, a bronchiolitis clinical trial, juvenile justice research on hepatitis B, a Hispanic cultural competency grant from the California Endowment, spiratory syncytial virus immunoprophylaxis outcomes in a managed population, and primary care perceptions of pediatric dentistry. Thus the hospitalist program has a long history of strong commitment to children and the core aspects of pediatric hospital medicine.

The Fellowship

The CSSD Pediatric Hospitalist Fellowship Program goal is to train highly motivated pediatricians for careers in academic and clinical hospital medicine. Over a two-year period instruction is provided in clinical, advocacy, administrative, teaching, and research aspects of pediatric hospital medicine. Clinical education emphasizes inpatient acute care, including intensive care and emergency transport at the busy main campus at CHHC. Outpatient clinical care offers experiences in adolescent juvenile hall medicine, hospice, and child protection. The diverse clinical exposure, teaching from local and national leaders, and volume of patients ensure graduates of this program are well prepared for any clinical hospitalist position.

The staff gains administrative experience via both hospital and medical group quality improvement activities. This work is directed by the medical director for CSSD and the physician advisor for quality management for CHHC, both of whom are CSSD pediatric hospitalists. Skills in process improvement, continuous quality improvement, risk management, organizational management and leadership are honed during the fellowship. Opportunity exists to take courses through the American College of Physician Executives if the trainee desires a future in administrative hospitalist medicine.

Academics and teaching are a core value of the pediatric hospitalist service. The fellow participates in the monthly division journal club and internal case review. Daily teaching while on the clinical service includes bedside rounds, management rounds, and attending rounds. Pediatric hospitalists are the primary inpatient teaching staff and as such have a significant responsibility for daily house staff education. The fellow participates in noon conferences and other educational venues under the guidance of the director of inpatient teaching (also a pediatric hospitalist).

Advocacy skills are learned through experiences in the juvenile hall system, Center for Child Protection, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), and at the local and state level for children’s services funding. Under the leadership of the medical directors for the Center for Child Protection and the A.B. and Jessie Polinsky Center for Abused Children, the fellow participates in case review and observes expert child abuse testimony in court. Discussions with legislators in Sacramento focus upon protection of the California Children’s Services system, which supports critically ill state-funded children. The fellow learns AAP local and national structure, participating in conferences and chapter events.

Research is expected during this two-year fellowship program. Formal clinical research training is part of the first year curriculum of UCSD’s Clinical Research Enhancement through Supplemental Training (CREST) program. The first year of this two-year CREST program includes weekly classes covering epidemiology, patient-oriented research, health services research, and informatics. Those dedicated to completion of a master’s degree during the two-year program may integrate this training with a more intense curriculum schedule. A research project and mentor is chosen after the first quarter of the first year. Research may be in any area of pediatric hospitalist medicine. Research is presented at either Pediatric Academic Societies, Society of Hospital Medicine, or other similar forum upon completion.

The schedule is flexible, but follows the template. (See Table 1, p. 30: “Pediatric Hospitalist Fellowship Program Schedule.”)

One fellowship position is offered every year, with application submissions accepted through Dec. 1, interviews granted Dec. 15-Feb. 1 and final selection by Feb. 15. You can obtain an application from the CSSD Web site “Fellowships” page (http://childrensspecialists. com/body.cfm?id=580) or by e-mailing Fellowship Coordinator Susan Stafford at sstafford@chsd.org.

PEDIATRIC SPECIAL SECTION:

IN THE LITERATURE

Retrospective Study Attempts Criteria for Diagnosing MAS

Reviews by Julia Simmons, MD

Ravelli A, Magni-Manzoni S, Pistorio A, et al. Preliminary diagnostic guidelines for macrophage activation syndrome complicating systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J Pediatr. 2005;146(5):598-604.

Macrophage activating syndrome (MAS) is a complication of connective tissue disorders, most often associated with active systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis (S-JIA). It is a rare disorder and the exact incidence is unknown. It is characterized by uncontrolled activation and proliferation of T-lymphocytes and macrophages. If not recognized and treated aggressively, MAS can be life threatening.

In this article, the authors’ purpose was to review the available clinical, laboratory, and histopathologic data in patients with active S-JIA and in those with active S-JIA complicated by MAS. The goal was to develop criteria to diagnose MAS.

The retrospective study was designed using the classification, criteria approach. The index cases included patients with MAS complicating S-JIA. The “confusable” condition was active S-JIA. There were 74 patients in the index cases. Seventeen of the cases were observed at the authors’ institution. These patients were diagnosed with S-JIA using the International League of Association for Rheumatology criteria. They were identified using a database search. Fifty-seven of the cases were obtained from a Medline search. Of these 74 patients, eight were disqualified because they did not meet the definition of S-JIA, and 11 were excluded because of insufficient data. The control group contained 37 patients observed at the authors’ sites. The sensitivity rate, specificity rate, area under receiver operating characteristic curve, and diagnostic odds ratio were applied to the data to differentiate MAS complicating S-JIA from S-JIA.

The study results found hemorrhages and central nervous dysfunction were the strongest clinical discriminating factors. The strongest laboratory discriminators included thrombocytopenia, leukopenia, elevated aspartate aminotransferase, and hypofibrinogenemia. Histopathological criterion included evidence of macrophage hemophagocytosis in the bone marrow aspirate. Other useful discriminators included hypertriglyceridemia, elevated ferritin, hepatomegaly, hand hyponatremia. Final guidelines were developed after analyzing the statistics and determining the clinical importance: “The diagnosis of MAS requires the presence of any two or more laboratory criteria or of any two or three or more clinical and/or laboratory criteria. A bone marrow aspirate for the demonstration of hemophagocytosis may be required only in doubtful cases.”

In summary, MAS complicating S-JIA is a disorder without concrete diagnostic criteria. The authors have performed preliminary studies to diagnose MAS. They appropriately recognized the need for prospective larger clinical studies.

HNL Helps Distinguish Infections

Fjaertoft G, Foucard T, Xu S, et al. Human neutrophil lipocalin (HNL) as a diagnostic tool in children with acute infections: a study of the kinetics. Acta Pediatrica costarricense. 2005;94:661-666.

In pediatrics, the clinician is often faced with the diagnostic challenge of differentiating a bacterial infectious process from a viral infection. History, physical exam, and laboratory data make the distinction. In this article, the authors’ purpose was to assess the kinetics of HNL with viral and bacterial infections. Further, they assess the response of HNL when the infection is treated with antibiotics. The response of HNL is compared with that of C-reactive protein.

In the study, 92 patients with a median age of 26 months were hospitalized because they required systemic antibiotics or because of the severity of their medical condition. Upon admission and on hospital days one, two, and three, the C-reactive protein, white blood cell count with differential, and HNL were measured. The patients were retrospectively classified into five groups: true bacterial infection (n=28), true viral infection (n=4), suspected bacterial infection (n=18), suspected viral (n=34), and other.

A true bacterial infection required bacterial isolation from blood, urine, or cerebrospinal fluid culture, or radiographic demonstration of pneumonia. Patients were classified as having a suspected bacterial infection if they had a nonspecific diagnosis, but an elevated C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate. A true viral infection required isolation of a virus. If a patient did not meet any of the above criteria, the person was classified as having a suspected viral infection. Those patients in the “other” group were diagnosed with Kawasaki disease, Borrelia meningitis, and one undiagnosed patient. The patients were classified using history, exam, and laboratory values including white blood cell count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, and cultures. HNL values were not used in the classification.

The results demonstrated that both C-reactive protein and HNL are elevated with true bacterial infections compared with viral illnesses. Neither C-reactive protein nor HNL were significantly different in true bacterial infections versus suspected bacterial infections. The optimal cut-off for C-reactive protein was 59 mg/L with 93% sensitivity and 68% specificity. The optimal cutoff for HNL was 217 micrograms/L with 90% sensitivity and 74% specificity. In patients with true bacterial infections, HNL was highest at admission and decreased one day after admission. In contrast, the C-reactive protein values were similar on the day of admission and on hospital day one. C-reactive protein decreased significantly on days two and three of hospitalization. After hospital day one, HNL was elevated in only 11% of patients with true bacterial infection in contrast to 83% patients with elevated C-reactive protein.

In summary, HNL may be a useful marker to distinguish bacterial and viral illnesses. In comparison with C-reactive protein, it normalizes more rapidly after appropriate antibiotic therapy is initiated. In the future, HNL may be a useful marker in monitoring the response to antibiotic therapy.

CEDKA in Peds

Lawrence SE, Cummings EA, Gaboury I, et al. Population-based study of incidence and risk factors for cerebral edema in pediatric diabetic ketoacidosis. . 2005;146:688-692.

New onset insulin dependent diabetes mellitus is complicated by diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) in 15% to 67% of patients. The incidence of cerebral edema in diabetic ketoacidosis (CEDKA) has been reported as 0.4-3.1. In the article, the authors seek to determine the incidence, outcome, and risk factors for cerebral edema in DKA in patients younger than 16.

The study was case-controlled with an active Canadian surveillance study. The authors surveyed pediatricians for a two-year period. During this time in Canada, all physicians were requested to submit reports monthly on patients with CEDKA younger than 16.

Thirteen cases were identified and the incidence of CEDKA was 0.51%. Overall mortality from cerebral edema was 0.15%. Increased blood urea nitrogen, degree of dehydration, hyperglycemia, and lower initial bicarbonate were associated with CEDKA. TH