User login

A 34-year-old woman with no significant past medical history presented as a new patient to our family medicine clinic with 2 weeks of intermittent lower abdominal and pelvic pain. She was sexually active with 1 partner and denied abnormal vaginal discharge or bleeding. She mentioned she’d had an intrauterine contraceptive device (IUD) placed a few weeks ago. The patient was afebrile, and her pelvic examination was unremarkable.

Physical examination showed mild tenderness to palpation over the lower abdomen without rebound tenderness or guarding. A complete metabolic panel revealed no significant abnormalities, and her human chorionic gonadotropin levels were normal.

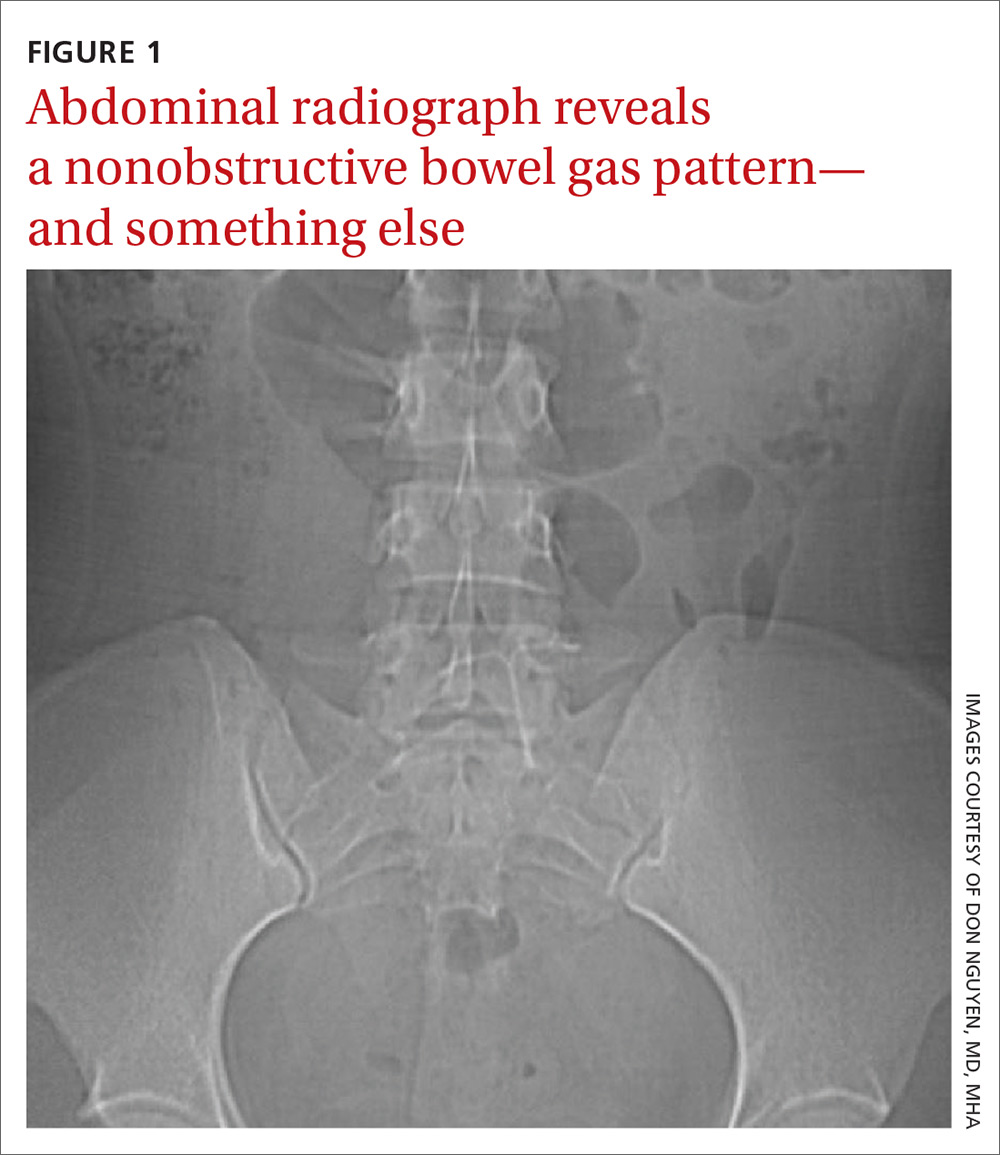

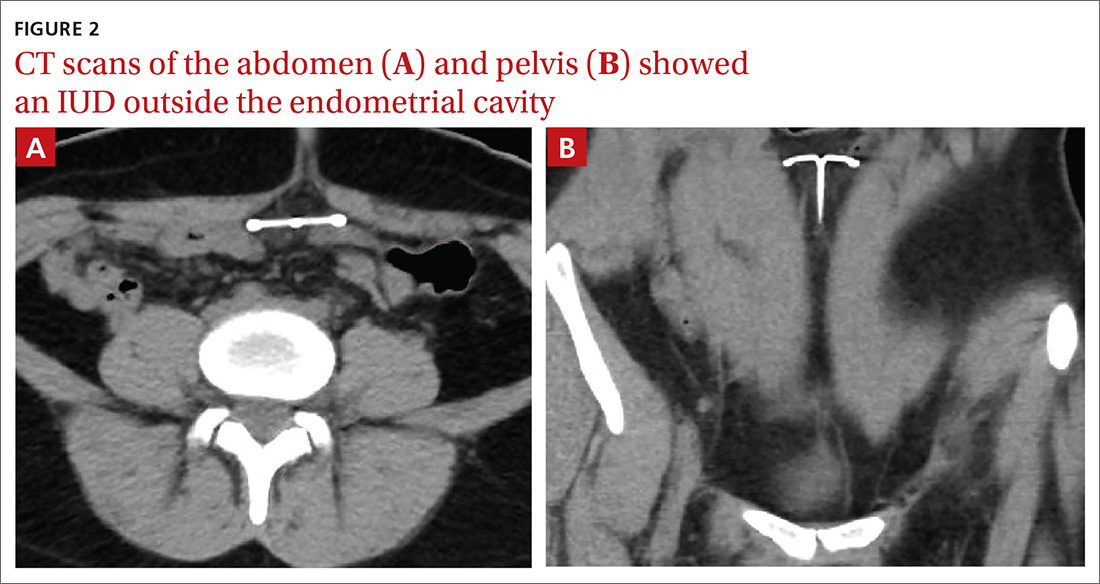

Findings from the physical exam and her clinical history prompted the need for imaging. An abdominal radiograph (FIGURE 1) and noncontrast computed tomography (FIGURES 2A and 2B) were subsequently ordered.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Intra-abdominal IUD migration

The abdominal radiograph revealed a nonobstructive bowel gas pattern with an IUD overlaying the central lower abdomen and pelvis at the L5-S1 level (FIGURE 1). Computed tomography (CT) of her abdomen and pelvis showed that the IUD was outside the endometrial cavity (FIGURES 2A and 2B). There was no evidence of pneumoperitoneum or bowel perforation. Based on the work-up and imaging, the patient’s pain was due to intra-abdominal IUD malpositioning.

Diagnostic criteria for IUD malpositioning include device migration into 1 of several locations, such as the lower uterine segment or cervix. IUD malpositioning can involve the rotation or protrusion of the device into or through the myometrium. On imaging, a well-positioned IUD should have a straight stem contained within the endometrial cavity, with the arms of the IUD extending laterally at the uterine fundus.

For our patient, an abdominal radiograph showed that her IUD was superiorly displaced outside the expected region of the endometrial cavity. CT helped to confirm this.

Complications with IUDs are few

Using an IUD is an increasingly popular method of contraception because it is effective and generally well tolerated, with minimal adverse effects or complications. In a multicenter retrospective chart review of 2138 patients who had IUDs, Aoun et al found that serious complications included pelvic inflammatory disease (2%), IUD expulsion (6%), and pregnancy (1%).1 In a retrospective cohort study examining complications among 90,489 women with IUDs, Berenson et al found ectopic pregnancy and uterine perforation affected < 1%.2

A less serious complication is IUD malpositioning. Although it does seem to occur more often than other, more serious complications, the exact incidence is unknown. In a retrospective case-control study, Braaten et al reported the rate for IUD malpositioning was 10.4% among 182 women.3 Malpositioned IUDs may be more likely to occur in those with suspected adenomyosis.3 In a study by de Kroon et al, the estimated prevalence rate for an abnormal IUD position ranged from 4% to 7.7% among 195 patients.4

Continue to: The clinical presentation of IUD migration

The clinical presentation of IUD migration

Identification of a malpositioned IUD is needed to avoid the possible increased risk for uterine perforation, IUD expulsion, or pregnancy.5

IUDs that have perforated the uterus float freely in the pelvis or abdomen and can result in injury to adjacent structures as well as peritonitis, fistulas, and hemorrhage.5-7 In addition, adhesion formation over the IUD can lead to intestinal obstruction, infertility, and chronic pain.6

Common symptoms of IUD malpositioning include abdominal or pelvic pain and abnormal bleeding, although many patients may be asymptomatic.8 In a retrospective study of 167 patients with IUDs who underwent pelvic ultrasound, 28 patients were found to have an IUD in an abnormal position.8 Rates of bleeding and pain were higher in patients with malpositioned IUDs (35.7% and 39.3%, respectively) than in those with a normally positioned IUD (15.1% and 19.4%, respectively).8

The differential Dx includes endometriosis and fibroids

IUD malpositioning can be distinguished from other diagnoses that cause pelvic pain and have similar presentations—including endometriosis, ectopic pregnancy, and fibroids—through imaging study findings, clinical history, and presentation.

Other conditions that may need to be ruled out include pelvic inflammatory disease, acute appendicitis, and ovarian cysts.9 A thorough history and physical examination can help rule out these conditions by organ system, and laboratory and imaging studies can help to confirm the diagnosis.

Continue to: Which imaging tool to use, and when

Which imaging tool to use, and when

Assessment of intrauterine contraception placement requires evaluation of the uterine cavity; gynecologic examination alone is not sufficient to fully evaluate for IUD position. Certain imaging studies are particularly helpful for revealing possible IUD migration.

Ultrasound—a widely available, radiation-free modality—is the first-line imaging tool for evaluation of an IUD’s position.10 In addition, ultrasound can provide effective evaluation of other pelvic structures, which is helpful in identifying or eliminating other causes of pain or abnormal bleeding.

Conventional radiography. If the IUD is not visualized on ultrasound, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends radiography to determine if the IUD has been expelled or has migrated to an extra-uterine position.6

CT may be best suited for the evaluation of more severe complications of IUD malpositioning, including visceral perforation, abscess formation, or bowel obstruction. CT should be considered if the patient’s clinical presentation is suspicious for a more serious intra-abdominal pathology.

Management depends on the IUD’s position

For patients whose IUD has an uncertain position or nonvisualized intravaginal strings, ACOG’s first-line recommendations include ruling out pregnancy, using an alternative method for contraception, and ordering pelvic ultrasonography.6 ACOG recommendations for the management of IUD malpositioning depend on the device’s location and the patient’s symptomatology.

Continue to: Management of low-lying IUDs

Management of low-lying IUDs is complex. An IUD that is malpositioned in the cervix is considered partially expelled and should be completely removed.6 For asymptomatic patients with an IUD located in the lower uterine segment and above the internal cervical os, there should be strong consideration given to leaving the IUD in place because removal is associated with higher rates of pregnancy given the low rates of initiation of effective contraception following removal.6

IUD malpositioning in the peritoneal cavity requires surgical intervention. Although ACOG’s first-line recommendation is laparoscopic intervention, laparotomy can be considered if laparoscopy does not result in the removal of the IUD or the patient has more severe complications (sepsis or bowel perforation).6 At the time of IUD removal, the clinician should also discuss and/or prescribe interim contraception.

Treatment for our patient included uncomplicated laparoscopic surgical removal of the intra-abdominal IUD. The patient’s symptoms went away following the procedure, and she was subsequently switched to an oral contraceptive.

1. Aoun J, Dines VA, Stovall DW, et al. Effects of age, parity, and device type on complications and discontinuation of intrauterine devices. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:585-592.

2. Berenson AB, Tan A, Hirth JM, et al. Complications and continuation of intrauterine device use among commercially insured teenagers. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121:951-958.

3. Braaten KP, Benson CB, Maurer R, et al. Malpositioned intrauterine contraceptive devices: risk factors, outcomes, and future pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118:1014-1020.

4. de Kroon CD, van Houwelingen JC, Trimbos JB, et al. The value of transvaginal ultrasound to monitor the position of an intrauterine device after insertion. A technology assessment study. Hum Reprod. 2003;18:2323-2327.

5. Thonneau P, Almont T, de La Rochebrochard E, et al. Risk factors for IUD failure: results of a large multicentre case-control study. Hum Reprod. 2006;21:2612-2616.

6. ACOG Committee on Gynecologic Practice. Committee Opinion No 672: clinical challenges of long-acting reversible contraceptive methods. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:e69-e77.

7. Heinemann K, Reed S, Moehner S, et al. Risk of uterine perforation with levonorgestrel-releasing and copper intrauterine devices in the European Active Surveillance Study on Intrauterine Devices. Contraception. 2015;91:274-279.

8. Benacerraf BR, Shipp TD, Bromley B. Three-dimensional ultrasound detection of abnormally located intrauterine contraceptive devices which are a source of pelvic pain and abnormal bleeding. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2009;34:110-115.

9. Bhavasr AK, Felner EJ, Shorma T. Common questions about the evaluation of acute pelvic pain. Am Fam Physician. 2016;93:41-48.

10. Peri N, Graham D, Levine D. Imaging of intrauterine contraceptive devices. J Ultrasound Med. 2007;26:1389-1401.

A 34-year-old woman with no significant past medical history presented as a new patient to our family medicine clinic with 2 weeks of intermittent lower abdominal and pelvic pain. She was sexually active with 1 partner and denied abnormal vaginal discharge or bleeding. She mentioned she’d had an intrauterine contraceptive device (IUD) placed a few weeks ago. The patient was afebrile, and her pelvic examination was unremarkable.

Physical examination showed mild tenderness to palpation over the lower abdomen without rebound tenderness or guarding. A complete metabolic panel revealed no significant abnormalities, and her human chorionic gonadotropin levels were normal.

Findings from the physical exam and her clinical history prompted the need for imaging. An abdominal radiograph (FIGURE 1) and noncontrast computed tomography (FIGURES 2A and 2B) were subsequently ordered.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Intra-abdominal IUD migration

The abdominal radiograph revealed a nonobstructive bowel gas pattern with an IUD overlaying the central lower abdomen and pelvis at the L5-S1 level (FIGURE 1). Computed tomography (CT) of her abdomen and pelvis showed that the IUD was outside the endometrial cavity (FIGURES 2A and 2B). There was no evidence of pneumoperitoneum or bowel perforation. Based on the work-up and imaging, the patient’s pain was due to intra-abdominal IUD malpositioning.

Diagnostic criteria for IUD malpositioning include device migration into 1 of several locations, such as the lower uterine segment or cervix. IUD malpositioning can involve the rotation or protrusion of the device into or through the myometrium. On imaging, a well-positioned IUD should have a straight stem contained within the endometrial cavity, with the arms of the IUD extending laterally at the uterine fundus.

For our patient, an abdominal radiograph showed that her IUD was superiorly displaced outside the expected region of the endometrial cavity. CT helped to confirm this.

Complications with IUDs are few

Using an IUD is an increasingly popular method of contraception because it is effective and generally well tolerated, with minimal adverse effects or complications. In a multicenter retrospective chart review of 2138 patients who had IUDs, Aoun et al found that serious complications included pelvic inflammatory disease (2%), IUD expulsion (6%), and pregnancy (1%).1 In a retrospective cohort study examining complications among 90,489 women with IUDs, Berenson et al found ectopic pregnancy and uterine perforation affected < 1%.2

A less serious complication is IUD malpositioning. Although it does seem to occur more often than other, more serious complications, the exact incidence is unknown. In a retrospective case-control study, Braaten et al reported the rate for IUD malpositioning was 10.4% among 182 women.3 Malpositioned IUDs may be more likely to occur in those with suspected adenomyosis.3 In a study by de Kroon et al, the estimated prevalence rate for an abnormal IUD position ranged from 4% to 7.7% among 195 patients.4

Continue to: The clinical presentation of IUD migration

The clinical presentation of IUD migration

Identification of a malpositioned IUD is needed to avoid the possible increased risk for uterine perforation, IUD expulsion, or pregnancy.5

IUDs that have perforated the uterus float freely in the pelvis or abdomen and can result in injury to adjacent structures as well as peritonitis, fistulas, and hemorrhage.5-7 In addition, adhesion formation over the IUD can lead to intestinal obstruction, infertility, and chronic pain.6

Common symptoms of IUD malpositioning include abdominal or pelvic pain and abnormal bleeding, although many patients may be asymptomatic.8 In a retrospective study of 167 patients with IUDs who underwent pelvic ultrasound, 28 patients were found to have an IUD in an abnormal position.8 Rates of bleeding and pain were higher in patients with malpositioned IUDs (35.7% and 39.3%, respectively) than in those with a normally positioned IUD (15.1% and 19.4%, respectively).8

The differential Dx includes endometriosis and fibroids

IUD malpositioning can be distinguished from other diagnoses that cause pelvic pain and have similar presentations—including endometriosis, ectopic pregnancy, and fibroids—through imaging study findings, clinical history, and presentation.

Other conditions that may need to be ruled out include pelvic inflammatory disease, acute appendicitis, and ovarian cysts.9 A thorough history and physical examination can help rule out these conditions by organ system, and laboratory and imaging studies can help to confirm the diagnosis.

Continue to: Which imaging tool to use, and when

Which imaging tool to use, and when

Assessment of intrauterine contraception placement requires evaluation of the uterine cavity; gynecologic examination alone is not sufficient to fully evaluate for IUD position. Certain imaging studies are particularly helpful for revealing possible IUD migration.

Ultrasound—a widely available, radiation-free modality—is the first-line imaging tool for evaluation of an IUD’s position.10 In addition, ultrasound can provide effective evaluation of other pelvic structures, which is helpful in identifying or eliminating other causes of pain or abnormal bleeding.

Conventional radiography. If the IUD is not visualized on ultrasound, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends radiography to determine if the IUD has been expelled or has migrated to an extra-uterine position.6

CT may be best suited for the evaluation of more severe complications of IUD malpositioning, including visceral perforation, abscess formation, or bowel obstruction. CT should be considered if the patient’s clinical presentation is suspicious for a more serious intra-abdominal pathology.

Management depends on the IUD’s position

For patients whose IUD has an uncertain position or nonvisualized intravaginal strings, ACOG’s first-line recommendations include ruling out pregnancy, using an alternative method for contraception, and ordering pelvic ultrasonography.6 ACOG recommendations for the management of IUD malpositioning depend on the device’s location and the patient’s symptomatology.

Continue to: Management of low-lying IUDs

Management of low-lying IUDs is complex. An IUD that is malpositioned in the cervix is considered partially expelled and should be completely removed.6 For asymptomatic patients with an IUD located in the lower uterine segment and above the internal cervical os, there should be strong consideration given to leaving the IUD in place because removal is associated with higher rates of pregnancy given the low rates of initiation of effective contraception following removal.6

IUD malpositioning in the peritoneal cavity requires surgical intervention. Although ACOG’s first-line recommendation is laparoscopic intervention, laparotomy can be considered if laparoscopy does not result in the removal of the IUD or the patient has more severe complications (sepsis or bowel perforation).6 At the time of IUD removal, the clinician should also discuss and/or prescribe interim contraception.

Treatment for our patient included uncomplicated laparoscopic surgical removal of the intra-abdominal IUD. The patient’s symptoms went away following the procedure, and she was subsequently switched to an oral contraceptive.

A 34-year-old woman with no significant past medical history presented as a new patient to our family medicine clinic with 2 weeks of intermittent lower abdominal and pelvic pain. She was sexually active with 1 partner and denied abnormal vaginal discharge or bleeding. She mentioned she’d had an intrauterine contraceptive device (IUD) placed a few weeks ago. The patient was afebrile, and her pelvic examination was unremarkable.

Physical examination showed mild tenderness to palpation over the lower abdomen without rebound tenderness or guarding. A complete metabolic panel revealed no significant abnormalities, and her human chorionic gonadotropin levels were normal.

Findings from the physical exam and her clinical history prompted the need for imaging. An abdominal radiograph (FIGURE 1) and noncontrast computed tomography (FIGURES 2A and 2B) were subsequently ordered.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Intra-abdominal IUD migration

The abdominal radiograph revealed a nonobstructive bowel gas pattern with an IUD overlaying the central lower abdomen and pelvis at the L5-S1 level (FIGURE 1). Computed tomography (CT) of her abdomen and pelvis showed that the IUD was outside the endometrial cavity (FIGURES 2A and 2B). There was no evidence of pneumoperitoneum or bowel perforation. Based on the work-up and imaging, the patient’s pain was due to intra-abdominal IUD malpositioning.

Diagnostic criteria for IUD malpositioning include device migration into 1 of several locations, such as the lower uterine segment or cervix. IUD malpositioning can involve the rotation or protrusion of the device into or through the myometrium. On imaging, a well-positioned IUD should have a straight stem contained within the endometrial cavity, with the arms of the IUD extending laterally at the uterine fundus.

For our patient, an abdominal radiograph showed that her IUD was superiorly displaced outside the expected region of the endometrial cavity. CT helped to confirm this.

Complications with IUDs are few

Using an IUD is an increasingly popular method of contraception because it is effective and generally well tolerated, with minimal adverse effects or complications. In a multicenter retrospective chart review of 2138 patients who had IUDs, Aoun et al found that serious complications included pelvic inflammatory disease (2%), IUD expulsion (6%), and pregnancy (1%).1 In a retrospective cohort study examining complications among 90,489 women with IUDs, Berenson et al found ectopic pregnancy and uterine perforation affected < 1%.2

A less serious complication is IUD malpositioning. Although it does seem to occur more often than other, more serious complications, the exact incidence is unknown. In a retrospective case-control study, Braaten et al reported the rate for IUD malpositioning was 10.4% among 182 women.3 Malpositioned IUDs may be more likely to occur in those with suspected adenomyosis.3 In a study by de Kroon et al, the estimated prevalence rate for an abnormal IUD position ranged from 4% to 7.7% among 195 patients.4

Continue to: The clinical presentation of IUD migration

The clinical presentation of IUD migration

Identification of a malpositioned IUD is needed to avoid the possible increased risk for uterine perforation, IUD expulsion, or pregnancy.5

IUDs that have perforated the uterus float freely in the pelvis or abdomen and can result in injury to adjacent structures as well as peritonitis, fistulas, and hemorrhage.5-7 In addition, adhesion formation over the IUD can lead to intestinal obstruction, infertility, and chronic pain.6

Common symptoms of IUD malpositioning include abdominal or pelvic pain and abnormal bleeding, although many patients may be asymptomatic.8 In a retrospective study of 167 patients with IUDs who underwent pelvic ultrasound, 28 patients were found to have an IUD in an abnormal position.8 Rates of bleeding and pain were higher in patients with malpositioned IUDs (35.7% and 39.3%, respectively) than in those with a normally positioned IUD (15.1% and 19.4%, respectively).8

The differential Dx includes endometriosis and fibroids

IUD malpositioning can be distinguished from other diagnoses that cause pelvic pain and have similar presentations—including endometriosis, ectopic pregnancy, and fibroids—through imaging study findings, clinical history, and presentation.

Other conditions that may need to be ruled out include pelvic inflammatory disease, acute appendicitis, and ovarian cysts.9 A thorough history and physical examination can help rule out these conditions by organ system, and laboratory and imaging studies can help to confirm the diagnosis.

Continue to: Which imaging tool to use, and when

Which imaging tool to use, and when

Assessment of intrauterine contraception placement requires evaluation of the uterine cavity; gynecologic examination alone is not sufficient to fully evaluate for IUD position. Certain imaging studies are particularly helpful for revealing possible IUD migration.

Ultrasound—a widely available, radiation-free modality—is the first-line imaging tool for evaluation of an IUD’s position.10 In addition, ultrasound can provide effective evaluation of other pelvic structures, which is helpful in identifying or eliminating other causes of pain or abnormal bleeding.

Conventional radiography. If the IUD is not visualized on ultrasound, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends radiography to determine if the IUD has been expelled or has migrated to an extra-uterine position.6

CT may be best suited for the evaluation of more severe complications of IUD malpositioning, including visceral perforation, abscess formation, or bowel obstruction. CT should be considered if the patient’s clinical presentation is suspicious for a more serious intra-abdominal pathology.

Management depends on the IUD’s position

For patients whose IUD has an uncertain position or nonvisualized intravaginal strings, ACOG’s first-line recommendations include ruling out pregnancy, using an alternative method for contraception, and ordering pelvic ultrasonography.6 ACOG recommendations for the management of IUD malpositioning depend on the device’s location and the patient’s symptomatology.

Continue to: Management of low-lying IUDs

Management of low-lying IUDs is complex. An IUD that is malpositioned in the cervix is considered partially expelled and should be completely removed.6 For asymptomatic patients with an IUD located in the lower uterine segment and above the internal cervical os, there should be strong consideration given to leaving the IUD in place because removal is associated with higher rates of pregnancy given the low rates of initiation of effective contraception following removal.6

IUD malpositioning in the peritoneal cavity requires surgical intervention. Although ACOG’s first-line recommendation is laparoscopic intervention, laparotomy can be considered if laparoscopy does not result in the removal of the IUD or the patient has more severe complications (sepsis or bowel perforation).6 At the time of IUD removal, the clinician should also discuss and/or prescribe interim contraception.

Treatment for our patient included uncomplicated laparoscopic surgical removal of the intra-abdominal IUD. The patient’s symptoms went away following the procedure, and she was subsequently switched to an oral contraceptive.

1. Aoun J, Dines VA, Stovall DW, et al. Effects of age, parity, and device type on complications and discontinuation of intrauterine devices. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:585-592.

2. Berenson AB, Tan A, Hirth JM, et al. Complications and continuation of intrauterine device use among commercially insured teenagers. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121:951-958.

3. Braaten KP, Benson CB, Maurer R, et al. Malpositioned intrauterine contraceptive devices: risk factors, outcomes, and future pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118:1014-1020.

4. de Kroon CD, van Houwelingen JC, Trimbos JB, et al. The value of transvaginal ultrasound to monitor the position of an intrauterine device after insertion. A technology assessment study. Hum Reprod. 2003;18:2323-2327.

5. Thonneau P, Almont T, de La Rochebrochard E, et al. Risk factors for IUD failure: results of a large multicentre case-control study. Hum Reprod. 2006;21:2612-2616.

6. ACOG Committee on Gynecologic Practice. Committee Opinion No 672: clinical challenges of long-acting reversible contraceptive methods. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:e69-e77.

7. Heinemann K, Reed S, Moehner S, et al. Risk of uterine perforation with levonorgestrel-releasing and copper intrauterine devices in the European Active Surveillance Study on Intrauterine Devices. Contraception. 2015;91:274-279.

8. Benacerraf BR, Shipp TD, Bromley B. Three-dimensional ultrasound detection of abnormally located intrauterine contraceptive devices which are a source of pelvic pain and abnormal bleeding. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2009;34:110-115.

9. Bhavasr AK, Felner EJ, Shorma T. Common questions about the evaluation of acute pelvic pain. Am Fam Physician. 2016;93:41-48.

10. Peri N, Graham D, Levine D. Imaging of intrauterine contraceptive devices. J Ultrasound Med. 2007;26:1389-1401.

1. Aoun J, Dines VA, Stovall DW, et al. Effects of age, parity, and device type on complications and discontinuation of intrauterine devices. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:585-592.

2. Berenson AB, Tan A, Hirth JM, et al. Complications and continuation of intrauterine device use among commercially insured teenagers. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121:951-958.

3. Braaten KP, Benson CB, Maurer R, et al. Malpositioned intrauterine contraceptive devices: risk factors, outcomes, and future pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118:1014-1020.

4. de Kroon CD, van Houwelingen JC, Trimbos JB, et al. The value of transvaginal ultrasound to monitor the position of an intrauterine device after insertion. A technology assessment study. Hum Reprod. 2003;18:2323-2327.

5. Thonneau P, Almont T, de La Rochebrochard E, et al. Risk factors for IUD failure: results of a large multicentre case-control study. Hum Reprod. 2006;21:2612-2616.

6. ACOG Committee on Gynecologic Practice. Committee Opinion No 672: clinical challenges of long-acting reversible contraceptive methods. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:e69-e77.

7. Heinemann K, Reed S, Moehner S, et al. Risk of uterine perforation with levonorgestrel-releasing and copper intrauterine devices in the European Active Surveillance Study on Intrauterine Devices. Contraception. 2015;91:274-279.

8. Benacerraf BR, Shipp TD, Bromley B. Three-dimensional ultrasound detection of abnormally located intrauterine contraceptive devices which are a source of pelvic pain and abnormal bleeding. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2009;34:110-115.

9. Bhavasr AK, Felner EJ, Shorma T. Common questions about the evaluation of acute pelvic pain. Am Fam Physician. 2016;93:41-48.

10. Peri N, Graham D, Levine D. Imaging of intrauterine contraceptive devices. J Ultrasound Med. 2007;26:1389-1401.