User login

Roy PM, Colombet I, Durieux P, et al. Systemic review and meta-analysis of strategies for the diagnosis of suspected pulmonary embolism. BMJ.2005;331:259.

Background: Despite technological advances, the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism remains challenging. A large number of diagnostic tests and strategies have been evaluated and yet the test characteristics of each and their practical use remain unclear.

Methods: Pierre-Marie Roy, MD and colleagues carried out a systematic review and meta-analysis to define the likelihood ratios (LRs) for different diagnostic modalities for pulmonary embolism and provide a simple, evidence-based diagnostic algorithm.

The authors performed a literature search from 1990-2003 identifying all articles that evaluated tests or strategies aimed at diagnosing pulmonary embolism. They only selected papers which were prospective, in which participants were recruited consecutively, and which pulmonary angiography was the reference standard for strategies to confirm pulmonary embolism and clinical follow-up or angiography were used for exclusion strategies.

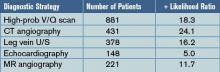

Results: Forty-eight articles (11,004 patients) met the inclusion criteria and examined ventilation/perfusion (V/Q) lung scanning, computed tomography (CT) angiography, leg vein ultrasound (U/S), echocardiography, magnetic resonance (MR) angiography, and the D-dimer test. For the studies done to evaluate tests to confirm the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism, pooled positive likelihood ratios (+LRs) were calculated and were:

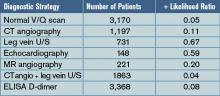

For the studies evaluating tests to exclude the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism, pooled negative likelihood ratios (-LR) were calculated and were:

Discussion: With the pooled positive and negative LRs, Roy and colleagues created a diagnostic algorithm, based on initial pretest probabilities, to help “rule in” and “rule out” the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism. Consistent with prior studies, a calculated post-test probability of >85% confirmed the diagnosis while a post-test probability <5% excluded PE.

In patients with a low or moderate pretest probability, pulmonary embolism is adequately excluded in patients with either 1) negative D-dimers or 2) a normal V/Q scan or 3) a negative CT angiogram in combination with a normal venous ultrasound. In patients with moderate or high pre-test probability, pulmonary embolism is confirmed by either 1) a high-probability V/Q scan or 2) a positive CT angiogram or 3) a positive venous ultrasound. Low-probability V/Q scanning, CT angiogram alone, and MR angiography have higher negative likelihood ratios and can only exclude PE in patients with low pre-test probability.

Many hospitalists are using CT angiography as their sole diagnostic test for pulmonary embolism. Based on the systematic review and meta-analysis by Roy and colleagues, we should proceed with caution as, in some patient populations, a positive or negative “spiral CT” does not adequately confirm or exclude the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism. For those that employ V/Q scanning, MR angiography, or D-dimers, the study also helps define how best to use these tests.

Safdar N, Maki DG. Risk of catheter-related bloodstream infection with peripherally inserted central venous catheters used in hospitalized patients. Chest. 2005;128:489.

Background: In recent years, peripherally inserted central catheters (PICCs) have become more popular, initially for long-term outpatient intravenous therapy but also for inpatient venous access. Traditionally, it was assumed that PICC lines have a lower rate of catheter-related bloodstream infection than conventional central venous catheters (CVCs) placed in the internal jugular, subclavian, or femoral veins.

Methods: One academic medical center prospectively studied the rate of catheter-related bloodstream infection in PICC lines used exclusively in hospitalized patients as part of two trials assessing efficacy of different skin antiseptics. PICC-related bloodstream infection was confirmed when organisms isolated from positive blood cultures matched (by DNA subtyping) organisms isolated from culturing the PICC line at the time of removal. The authors also performed a systematic review of the literature to provide overall estimates of PICC-related bloodstream infection in hospitalized patients.

Results: A total of 115 patients received 251 PICC lines during the study period and the mean duration of catheterization was 11.3 days. More than 40% of the patients were in the intensive care unit (ICU) and most had risk factors for the development of bloodstream infection, including urinary catheterization, mechanical ventilation, prior antibiotic use, and low albumin. Six cases (2.4%) of PICC-related bloodstream infection were confirmed, four with coagulase-negative staphylococcus, one with S. aureus, and one with Klebsiella pneumoniae, a rate of 2.1 per 1,000 catheter-days. In their systematic review, the authors identified 14 studies evaluating the rate of PICC-related bloodstream infection in hospitalized patients; the pooled rate was 1.9 per 1,000 catheter-days.

Discussion: In a small but methodologically sound prospective study and systematic review, Safdar and Maki found a surprisingly high rate of PICC-related bloodstream infection in hospitalized patients. Their calculated rate of 2.1 cases per 1,000 catheter-days is five times the rate seen in PICCs used exclusively in outpatients (0.4 per 1,000 catheter-days). More strikingly, 2.1 cases per 1,000 catheter-days is similar to the rate of catheter-related bloodstream infection in conventional central venous catheters placed in the subclavian or internal jugular veins (two to five per 1,000 catheter-days). Unfortunately, the study didn’t assess the rate of mechanical complications associated with PICC lines or correlate the risk of infection with duration of catheterization.

Hospitalists should be aware that PICC lines likely have the same infection risk as subclavian and internal jugular lines in hospitalized patients and a much higher rate of infection than PICC lines in outpatients. The higher-than-expected rates are likely related to the increased prevalence of risk factors for bloodstream infection in hospitalized patients. Thus, the decision to use PICC lines in hospitalized patients should be made based on factors other than presumed lower infection risk.

Uchino S, Kellum JA, Bellomo R, et al. Acute renal failure in critically ill patients. A multinational, multicenter study. JAMA. 2005;294:813.

Background: Acute renal failure in critically ill patients is believed common and is associated with a high mortality. The exact prevalence and the calculated risk of death have not been clearly defined across populations.

Methods: A multinational group of investigators conducted a massive prospective observational study of ICU patients who developed renal failure after ICU admission. The study encompassed 54 hospitals in 23 countries with a total of 29,269 admissions over the 14-month study period. Note, acute renal failure was defined as either oliguria (urine output <200cc/12 hours) or BUN >84mg/dL.

Results: Of all ICU patients studied, 5.7% developed acute renal failure after admission and 4.7% of patients received renal replacement therapy (most often continuous replacement). The most common contributing factor to the development of acute renal failure was septic shock (48%), followed by major surgery (34%) and cardiogenic shock (26%). Up to 19% of the cases of acute renal failure were estimated to be drug-related. The in-hospital mortality for critically ill patients with acute renal failure was 60%, which was substantially higher than the mortality estimated by other physiologic scoring systems (45% mortality according to SAPS II). Of those who survived to hospital discharge, only 14% required ongoing hemodialysis.

Discussion: This large, multinational, multicenter prospective observational study helps better define the prevalence and characteristic of acute renal failure that develops in critically ill patients. Overall, acute renal failure in the ICU setting is relatively uncommon, is most often caused by septic shock, and typically does require renal replacement therapy. There was a surprisingly high rate of acute renal failure thought to be secondary to medication or drug effect (19%).

The mortality in patients who develop renal failure in the ICU is high but, surprisingly, if patients survive, they are unlikely to need long-term hemodialysis. The study is limited in that it was not randomized and outcomes associated with particular interventions could not be determined. Yet, the data adds to our understanding of acute renal failure in the ICU and knowledge of the prevalence and expected outcomes could potentially help with prognosis and end-of-life discussions in the intensive care unit.

Roy CL, Poon EG, Karson AS, et al. Patient safety concerns arising from test results that return after hospital discharge. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:121.

Background: Adequate communication between hospitalists and outpatient providers is essential to patient safety as well as patient and physician satisfaction. It is estimated that more than half of all preventable adverse events occurring soon after hospital discharge have been related to poor communication among providers. With increasing pressure to limit inpatient length of stay, patients are often discharged with numerous laboratory or radiologic test results pending.

Methods: Roy and colleagues at a tertiary care academic medical center prospectively determined the prevalence and characteristics of tests pending at discharge and assessed physician awareness as well as satisfaction. All patients discharged from two hospitalist services over four months in 2004 were followed. Researchers identified all pending test results for these patients and all abnormal tests were reviewed by study physicians and judged to be “potentially actionable” or not (if it could change the management of the patient by requiring a new treatment or diagnostic test, change in a treatment, scheduling of an earlier follow-up, etc).

Results: Of the 2,644 patients discharged, 1,095 (41%) had laboratory or radiographic tests pending. Approximately 43% of all pending tests were abnormal and ~10% of the pending tests were judged by physician-reviewers to be potentially actionable. Examples include a TSH that returned as <0.01 mU/mL after discharge in a patient with new atrial fibrillation, or a urine culture that grew an organism resistant to the antibiotics given at discharge. Of note, outpatient physicians were unaware of two-thirds of the “potentially actionable” results. Finally, when surveyed, the majority of inpatient physicians were concerned about appropriate follow-up of tests and dissatisfied with the system used.

Discussion: Roy and his coauthors attempted to quantify the prevalence of potentially actionable laboratory tests available after discharge and published rather striking findings. Up to half of all patients have some tests pending at discharge and up to 10% of these require some physician action. More frighteningly, outpatient MDs are generally unaware of these tests creating a huge gap in patient safety in the transition back to outpatient care.

How can we do this better? SHM and the Society for General Internal Medicine have convened a Continuity of Care Task Force and found poor communication with outpatient providers was a common and potentially dangerous problem. They outlined the best practices for the discharge of patients to ensure safety as well as maximize patient and physician satisfaction. Their recommendations are available on the SHM Web site. All hospitalists and institutions should be aware of the potential for missed results and put systems in place, electronic and otherwise, to create an appropriate safety net for our discharged patients.

Sharma R, Loomis W, Brown RB. Impact of mandatory inpatient infectious disease consultation on outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy. Am J Med Sci. 2005;330(2):60.

Background: As the pressure to limit healthcare costs by reducing inpatient length of stay has increased, the use of outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy has grown. When employed appropriately, home intravenous antibiotic therapy has consistently resulted in cost savings without compromising patient outcomes. As with other healthcare advances, there is some fear that outpatient parenteral antibiotic treatment will be overused or misused, limiting the cost savings or putting patients at risk.

Methods: A single academic medical center instituted mandatory infectious disease consultation on all patients referred to discharge coordinators with plans for outpatient IV antibiotic treatment. The infectious disease consultants helped to determine the need for outpatient parenteral therapy and antibiotic choice. All patients were followed for 30 days.

Results: Over the one-year study period, 44 cases received mandatory infectious disease consultation. Thirty-nine (89%) of these had some change in antibiotic regimen after the consultation. Seventeen patients (39%) were switched to oral antibiotics, 13 (30%) had a change in infectious disease antibiotic, and 5 (11%) had a change in antibiotic dose.

Skin and skin structure and intra-abdominal infections were the most common diagnoses for which antibiotics were changed; a typical change was from intravenous piperacillin/tazobactam to an oral fluoroquinolone plus oral anaerobic coverage. At 30-day follow-up, 98% of patients finished their courses without relapse or complication. The overall costs savings was $27,500 or $1,550 per patient consulted upon.

Discussion: Although from a small, nonrandomized, single-institution study, the results are impressive. Mandatory infectious disease consultation prior to discharge for patients scheduled to received outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy resulted in substantial cost savings, and streamlined and more appropriate antibiotic regimens without any adverse impact on outcomes. Hospitalists should take two things away from this study: 1) consider consulting infection disease specialists on all patients who might be candidates for home IV antibiotics and 2) be aware that many skin and skin tissue and intra-abdominal infections can often be treated with oral therapy. TH

Roy PM, Colombet I, Durieux P, et al. Systemic review and meta-analysis of strategies for the diagnosis of suspected pulmonary embolism. BMJ.2005;331:259.

Background: Despite technological advances, the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism remains challenging. A large number of diagnostic tests and strategies have been evaluated and yet the test characteristics of each and their practical use remain unclear.

Methods: Pierre-Marie Roy, MD and colleagues carried out a systematic review and meta-analysis to define the likelihood ratios (LRs) for different diagnostic modalities for pulmonary embolism and provide a simple, evidence-based diagnostic algorithm.

The authors performed a literature search from 1990-2003 identifying all articles that evaluated tests or strategies aimed at diagnosing pulmonary embolism. They only selected papers which were prospective, in which participants were recruited consecutively, and which pulmonary angiography was the reference standard for strategies to confirm pulmonary embolism and clinical follow-up or angiography were used for exclusion strategies.

Results: Forty-eight articles (11,004 patients) met the inclusion criteria and examined ventilation/perfusion (V/Q) lung scanning, computed tomography (CT) angiography, leg vein ultrasound (U/S), echocardiography, magnetic resonance (MR) angiography, and the D-dimer test. For the studies done to evaluate tests to confirm the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism, pooled positive likelihood ratios (+LRs) were calculated and were:

For the studies evaluating tests to exclude the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism, pooled negative likelihood ratios (-LR) were calculated and were:

Discussion: With the pooled positive and negative LRs, Roy and colleagues created a diagnostic algorithm, based on initial pretest probabilities, to help “rule in” and “rule out” the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism. Consistent with prior studies, a calculated post-test probability of >85% confirmed the diagnosis while a post-test probability <5% excluded PE.

In patients with a low or moderate pretest probability, pulmonary embolism is adequately excluded in patients with either 1) negative D-dimers or 2) a normal V/Q scan or 3) a negative CT angiogram in combination with a normal venous ultrasound. In patients with moderate or high pre-test probability, pulmonary embolism is confirmed by either 1) a high-probability V/Q scan or 2) a positive CT angiogram or 3) a positive venous ultrasound. Low-probability V/Q scanning, CT angiogram alone, and MR angiography have higher negative likelihood ratios and can only exclude PE in patients with low pre-test probability.

Many hospitalists are using CT angiography as their sole diagnostic test for pulmonary embolism. Based on the systematic review and meta-analysis by Roy and colleagues, we should proceed with caution as, in some patient populations, a positive or negative “spiral CT” does not adequately confirm or exclude the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism. For those that employ V/Q scanning, MR angiography, or D-dimers, the study also helps define how best to use these tests.

Safdar N, Maki DG. Risk of catheter-related bloodstream infection with peripherally inserted central venous catheters used in hospitalized patients. Chest. 2005;128:489.

Background: In recent years, peripherally inserted central catheters (PICCs) have become more popular, initially for long-term outpatient intravenous therapy but also for inpatient venous access. Traditionally, it was assumed that PICC lines have a lower rate of catheter-related bloodstream infection than conventional central venous catheters (CVCs) placed in the internal jugular, subclavian, or femoral veins.

Methods: One academic medical center prospectively studied the rate of catheter-related bloodstream infection in PICC lines used exclusively in hospitalized patients as part of two trials assessing efficacy of different skin antiseptics. PICC-related bloodstream infection was confirmed when organisms isolated from positive blood cultures matched (by DNA subtyping) organisms isolated from culturing the PICC line at the time of removal. The authors also performed a systematic review of the literature to provide overall estimates of PICC-related bloodstream infection in hospitalized patients.

Results: A total of 115 patients received 251 PICC lines during the study period and the mean duration of catheterization was 11.3 days. More than 40% of the patients were in the intensive care unit (ICU) and most had risk factors for the development of bloodstream infection, including urinary catheterization, mechanical ventilation, prior antibiotic use, and low albumin. Six cases (2.4%) of PICC-related bloodstream infection were confirmed, four with coagulase-negative staphylococcus, one with S. aureus, and one with Klebsiella pneumoniae, a rate of 2.1 per 1,000 catheter-days. In their systematic review, the authors identified 14 studies evaluating the rate of PICC-related bloodstream infection in hospitalized patients; the pooled rate was 1.9 per 1,000 catheter-days.

Discussion: In a small but methodologically sound prospective study and systematic review, Safdar and Maki found a surprisingly high rate of PICC-related bloodstream infection in hospitalized patients. Their calculated rate of 2.1 cases per 1,000 catheter-days is five times the rate seen in PICCs used exclusively in outpatients (0.4 per 1,000 catheter-days). More strikingly, 2.1 cases per 1,000 catheter-days is similar to the rate of catheter-related bloodstream infection in conventional central venous catheters placed in the subclavian or internal jugular veins (two to five per 1,000 catheter-days). Unfortunately, the study didn’t assess the rate of mechanical complications associated with PICC lines or correlate the risk of infection with duration of catheterization.

Hospitalists should be aware that PICC lines likely have the same infection risk as subclavian and internal jugular lines in hospitalized patients and a much higher rate of infection than PICC lines in outpatients. The higher-than-expected rates are likely related to the increased prevalence of risk factors for bloodstream infection in hospitalized patients. Thus, the decision to use PICC lines in hospitalized patients should be made based on factors other than presumed lower infection risk.

Uchino S, Kellum JA, Bellomo R, et al. Acute renal failure in critically ill patients. A multinational, multicenter study. JAMA. 2005;294:813.

Background: Acute renal failure in critically ill patients is believed common and is associated with a high mortality. The exact prevalence and the calculated risk of death have not been clearly defined across populations.

Methods: A multinational group of investigators conducted a massive prospective observational study of ICU patients who developed renal failure after ICU admission. The study encompassed 54 hospitals in 23 countries with a total of 29,269 admissions over the 14-month study period. Note, acute renal failure was defined as either oliguria (urine output <200cc/12 hours) or BUN >84mg/dL.

Results: Of all ICU patients studied, 5.7% developed acute renal failure after admission and 4.7% of patients received renal replacement therapy (most often continuous replacement). The most common contributing factor to the development of acute renal failure was septic shock (48%), followed by major surgery (34%) and cardiogenic shock (26%). Up to 19% of the cases of acute renal failure were estimated to be drug-related. The in-hospital mortality for critically ill patients with acute renal failure was 60%, which was substantially higher than the mortality estimated by other physiologic scoring systems (45% mortality according to SAPS II). Of those who survived to hospital discharge, only 14% required ongoing hemodialysis.

Discussion: This large, multinational, multicenter prospective observational study helps better define the prevalence and characteristic of acute renal failure that develops in critically ill patients. Overall, acute renal failure in the ICU setting is relatively uncommon, is most often caused by septic shock, and typically does require renal replacement therapy. There was a surprisingly high rate of acute renal failure thought to be secondary to medication or drug effect (19%).

The mortality in patients who develop renal failure in the ICU is high but, surprisingly, if patients survive, they are unlikely to need long-term hemodialysis. The study is limited in that it was not randomized and outcomes associated with particular interventions could not be determined. Yet, the data adds to our understanding of acute renal failure in the ICU and knowledge of the prevalence and expected outcomes could potentially help with prognosis and end-of-life discussions in the intensive care unit.

Roy CL, Poon EG, Karson AS, et al. Patient safety concerns arising from test results that return after hospital discharge. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:121.

Background: Adequate communication between hospitalists and outpatient providers is essential to patient safety as well as patient and physician satisfaction. It is estimated that more than half of all preventable adverse events occurring soon after hospital discharge have been related to poor communication among providers. With increasing pressure to limit inpatient length of stay, patients are often discharged with numerous laboratory or radiologic test results pending.

Methods: Roy and colleagues at a tertiary care academic medical center prospectively determined the prevalence and characteristics of tests pending at discharge and assessed physician awareness as well as satisfaction. All patients discharged from two hospitalist services over four months in 2004 were followed. Researchers identified all pending test results for these patients and all abnormal tests were reviewed by study physicians and judged to be “potentially actionable” or not (if it could change the management of the patient by requiring a new treatment or diagnostic test, change in a treatment, scheduling of an earlier follow-up, etc).

Results: Of the 2,644 patients discharged, 1,095 (41%) had laboratory or radiographic tests pending. Approximately 43% of all pending tests were abnormal and ~10% of the pending tests were judged by physician-reviewers to be potentially actionable. Examples include a TSH that returned as <0.01 mU/mL after discharge in a patient with new atrial fibrillation, or a urine culture that grew an organism resistant to the antibiotics given at discharge. Of note, outpatient physicians were unaware of two-thirds of the “potentially actionable” results. Finally, when surveyed, the majority of inpatient physicians were concerned about appropriate follow-up of tests and dissatisfied with the system used.

Discussion: Roy and his coauthors attempted to quantify the prevalence of potentially actionable laboratory tests available after discharge and published rather striking findings. Up to half of all patients have some tests pending at discharge and up to 10% of these require some physician action. More frighteningly, outpatient MDs are generally unaware of these tests creating a huge gap in patient safety in the transition back to outpatient care.

How can we do this better? SHM and the Society for General Internal Medicine have convened a Continuity of Care Task Force and found poor communication with outpatient providers was a common and potentially dangerous problem. They outlined the best practices for the discharge of patients to ensure safety as well as maximize patient and physician satisfaction. Their recommendations are available on the SHM Web site. All hospitalists and institutions should be aware of the potential for missed results and put systems in place, electronic and otherwise, to create an appropriate safety net for our discharged patients.

Sharma R, Loomis W, Brown RB. Impact of mandatory inpatient infectious disease consultation on outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy. Am J Med Sci. 2005;330(2):60.

Background: As the pressure to limit healthcare costs by reducing inpatient length of stay has increased, the use of outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy has grown. When employed appropriately, home intravenous antibiotic therapy has consistently resulted in cost savings without compromising patient outcomes. As with other healthcare advances, there is some fear that outpatient parenteral antibiotic treatment will be overused or misused, limiting the cost savings or putting patients at risk.

Methods: A single academic medical center instituted mandatory infectious disease consultation on all patients referred to discharge coordinators with plans for outpatient IV antibiotic treatment. The infectious disease consultants helped to determine the need for outpatient parenteral therapy and antibiotic choice. All patients were followed for 30 days.

Results: Over the one-year study period, 44 cases received mandatory infectious disease consultation. Thirty-nine (89%) of these had some change in antibiotic regimen after the consultation. Seventeen patients (39%) were switched to oral antibiotics, 13 (30%) had a change in infectious disease antibiotic, and 5 (11%) had a change in antibiotic dose.

Skin and skin structure and intra-abdominal infections were the most common diagnoses for which antibiotics were changed; a typical change was from intravenous piperacillin/tazobactam to an oral fluoroquinolone plus oral anaerobic coverage. At 30-day follow-up, 98% of patients finished their courses without relapse or complication. The overall costs savings was $27,500 or $1,550 per patient consulted upon.

Discussion: Although from a small, nonrandomized, single-institution study, the results are impressive. Mandatory infectious disease consultation prior to discharge for patients scheduled to received outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy resulted in substantial cost savings, and streamlined and more appropriate antibiotic regimens without any adverse impact on outcomes. Hospitalists should take two things away from this study: 1) consider consulting infection disease specialists on all patients who might be candidates for home IV antibiotics and 2) be aware that many skin and skin tissue and intra-abdominal infections can often be treated with oral therapy. TH

Roy PM, Colombet I, Durieux P, et al. Systemic review and meta-analysis of strategies for the diagnosis of suspected pulmonary embolism. BMJ.2005;331:259.

Background: Despite technological advances, the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism remains challenging. A large number of diagnostic tests and strategies have been evaluated and yet the test characteristics of each and their practical use remain unclear.

Methods: Pierre-Marie Roy, MD and colleagues carried out a systematic review and meta-analysis to define the likelihood ratios (LRs) for different diagnostic modalities for pulmonary embolism and provide a simple, evidence-based diagnostic algorithm.

The authors performed a literature search from 1990-2003 identifying all articles that evaluated tests or strategies aimed at diagnosing pulmonary embolism. They only selected papers which were prospective, in which participants were recruited consecutively, and which pulmonary angiography was the reference standard for strategies to confirm pulmonary embolism and clinical follow-up or angiography were used for exclusion strategies.

Results: Forty-eight articles (11,004 patients) met the inclusion criteria and examined ventilation/perfusion (V/Q) lung scanning, computed tomography (CT) angiography, leg vein ultrasound (U/S), echocardiography, magnetic resonance (MR) angiography, and the D-dimer test. For the studies done to evaluate tests to confirm the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism, pooled positive likelihood ratios (+LRs) were calculated and were:

For the studies evaluating tests to exclude the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism, pooled negative likelihood ratios (-LR) were calculated and were:

Discussion: With the pooled positive and negative LRs, Roy and colleagues created a diagnostic algorithm, based on initial pretest probabilities, to help “rule in” and “rule out” the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism. Consistent with prior studies, a calculated post-test probability of >85% confirmed the diagnosis while a post-test probability <5% excluded PE.

In patients with a low or moderate pretest probability, pulmonary embolism is adequately excluded in patients with either 1) negative D-dimers or 2) a normal V/Q scan or 3) a negative CT angiogram in combination with a normal venous ultrasound. In patients with moderate or high pre-test probability, pulmonary embolism is confirmed by either 1) a high-probability V/Q scan or 2) a positive CT angiogram or 3) a positive venous ultrasound. Low-probability V/Q scanning, CT angiogram alone, and MR angiography have higher negative likelihood ratios and can only exclude PE in patients with low pre-test probability.

Many hospitalists are using CT angiography as their sole diagnostic test for pulmonary embolism. Based on the systematic review and meta-analysis by Roy and colleagues, we should proceed with caution as, in some patient populations, a positive or negative “spiral CT” does not adequately confirm or exclude the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism. For those that employ V/Q scanning, MR angiography, or D-dimers, the study also helps define how best to use these tests.

Safdar N, Maki DG. Risk of catheter-related bloodstream infection with peripherally inserted central venous catheters used in hospitalized patients. Chest. 2005;128:489.

Background: In recent years, peripherally inserted central catheters (PICCs) have become more popular, initially for long-term outpatient intravenous therapy but also for inpatient venous access. Traditionally, it was assumed that PICC lines have a lower rate of catheter-related bloodstream infection than conventional central venous catheters (CVCs) placed in the internal jugular, subclavian, or femoral veins.

Methods: One academic medical center prospectively studied the rate of catheter-related bloodstream infection in PICC lines used exclusively in hospitalized patients as part of two trials assessing efficacy of different skin antiseptics. PICC-related bloodstream infection was confirmed when organisms isolated from positive blood cultures matched (by DNA subtyping) organisms isolated from culturing the PICC line at the time of removal. The authors also performed a systematic review of the literature to provide overall estimates of PICC-related bloodstream infection in hospitalized patients.

Results: A total of 115 patients received 251 PICC lines during the study period and the mean duration of catheterization was 11.3 days. More than 40% of the patients were in the intensive care unit (ICU) and most had risk factors for the development of bloodstream infection, including urinary catheterization, mechanical ventilation, prior antibiotic use, and low albumin. Six cases (2.4%) of PICC-related bloodstream infection were confirmed, four with coagulase-negative staphylococcus, one with S. aureus, and one with Klebsiella pneumoniae, a rate of 2.1 per 1,000 catheter-days. In their systematic review, the authors identified 14 studies evaluating the rate of PICC-related bloodstream infection in hospitalized patients; the pooled rate was 1.9 per 1,000 catheter-days.

Discussion: In a small but methodologically sound prospective study and systematic review, Safdar and Maki found a surprisingly high rate of PICC-related bloodstream infection in hospitalized patients. Their calculated rate of 2.1 cases per 1,000 catheter-days is five times the rate seen in PICCs used exclusively in outpatients (0.4 per 1,000 catheter-days). More strikingly, 2.1 cases per 1,000 catheter-days is similar to the rate of catheter-related bloodstream infection in conventional central venous catheters placed in the subclavian or internal jugular veins (two to five per 1,000 catheter-days). Unfortunately, the study didn’t assess the rate of mechanical complications associated with PICC lines or correlate the risk of infection with duration of catheterization.

Hospitalists should be aware that PICC lines likely have the same infection risk as subclavian and internal jugular lines in hospitalized patients and a much higher rate of infection than PICC lines in outpatients. The higher-than-expected rates are likely related to the increased prevalence of risk factors for bloodstream infection in hospitalized patients. Thus, the decision to use PICC lines in hospitalized patients should be made based on factors other than presumed lower infection risk.

Uchino S, Kellum JA, Bellomo R, et al. Acute renal failure in critically ill patients. A multinational, multicenter study. JAMA. 2005;294:813.

Background: Acute renal failure in critically ill patients is believed common and is associated with a high mortality. The exact prevalence and the calculated risk of death have not been clearly defined across populations.

Methods: A multinational group of investigators conducted a massive prospective observational study of ICU patients who developed renal failure after ICU admission. The study encompassed 54 hospitals in 23 countries with a total of 29,269 admissions over the 14-month study period. Note, acute renal failure was defined as either oliguria (urine output <200cc/12 hours) or BUN >84mg/dL.

Results: Of all ICU patients studied, 5.7% developed acute renal failure after admission and 4.7% of patients received renal replacement therapy (most often continuous replacement). The most common contributing factor to the development of acute renal failure was septic shock (48%), followed by major surgery (34%) and cardiogenic shock (26%). Up to 19% of the cases of acute renal failure were estimated to be drug-related. The in-hospital mortality for critically ill patients with acute renal failure was 60%, which was substantially higher than the mortality estimated by other physiologic scoring systems (45% mortality according to SAPS II). Of those who survived to hospital discharge, only 14% required ongoing hemodialysis.

Discussion: This large, multinational, multicenter prospective observational study helps better define the prevalence and characteristic of acute renal failure that develops in critically ill patients. Overall, acute renal failure in the ICU setting is relatively uncommon, is most often caused by septic shock, and typically does require renal replacement therapy. There was a surprisingly high rate of acute renal failure thought to be secondary to medication or drug effect (19%).

The mortality in patients who develop renal failure in the ICU is high but, surprisingly, if patients survive, they are unlikely to need long-term hemodialysis. The study is limited in that it was not randomized and outcomes associated with particular interventions could not be determined. Yet, the data adds to our understanding of acute renal failure in the ICU and knowledge of the prevalence and expected outcomes could potentially help with prognosis and end-of-life discussions in the intensive care unit.

Roy CL, Poon EG, Karson AS, et al. Patient safety concerns arising from test results that return after hospital discharge. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:121.

Background: Adequate communication between hospitalists and outpatient providers is essential to patient safety as well as patient and physician satisfaction. It is estimated that more than half of all preventable adverse events occurring soon after hospital discharge have been related to poor communication among providers. With increasing pressure to limit inpatient length of stay, patients are often discharged with numerous laboratory or radiologic test results pending.

Methods: Roy and colleagues at a tertiary care academic medical center prospectively determined the prevalence and characteristics of tests pending at discharge and assessed physician awareness as well as satisfaction. All patients discharged from two hospitalist services over four months in 2004 were followed. Researchers identified all pending test results for these patients and all abnormal tests were reviewed by study physicians and judged to be “potentially actionable” or not (if it could change the management of the patient by requiring a new treatment or diagnostic test, change in a treatment, scheduling of an earlier follow-up, etc).

Results: Of the 2,644 patients discharged, 1,095 (41%) had laboratory or radiographic tests pending. Approximately 43% of all pending tests were abnormal and ~10% of the pending tests were judged by physician-reviewers to be potentially actionable. Examples include a TSH that returned as <0.01 mU/mL after discharge in a patient with new atrial fibrillation, or a urine culture that grew an organism resistant to the antibiotics given at discharge. Of note, outpatient physicians were unaware of two-thirds of the “potentially actionable” results. Finally, when surveyed, the majority of inpatient physicians were concerned about appropriate follow-up of tests and dissatisfied with the system used.

Discussion: Roy and his coauthors attempted to quantify the prevalence of potentially actionable laboratory tests available after discharge and published rather striking findings. Up to half of all patients have some tests pending at discharge and up to 10% of these require some physician action. More frighteningly, outpatient MDs are generally unaware of these tests creating a huge gap in patient safety in the transition back to outpatient care.

How can we do this better? SHM and the Society for General Internal Medicine have convened a Continuity of Care Task Force and found poor communication with outpatient providers was a common and potentially dangerous problem. They outlined the best practices for the discharge of patients to ensure safety as well as maximize patient and physician satisfaction. Their recommendations are available on the SHM Web site. All hospitalists and institutions should be aware of the potential for missed results and put systems in place, electronic and otherwise, to create an appropriate safety net for our discharged patients.

Sharma R, Loomis W, Brown RB. Impact of mandatory inpatient infectious disease consultation on outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy. Am J Med Sci. 2005;330(2):60.

Background: As the pressure to limit healthcare costs by reducing inpatient length of stay has increased, the use of outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy has grown. When employed appropriately, home intravenous antibiotic therapy has consistently resulted in cost savings without compromising patient outcomes. As with other healthcare advances, there is some fear that outpatient parenteral antibiotic treatment will be overused or misused, limiting the cost savings or putting patients at risk.

Methods: A single academic medical center instituted mandatory infectious disease consultation on all patients referred to discharge coordinators with plans for outpatient IV antibiotic treatment. The infectious disease consultants helped to determine the need for outpatient parenteral therapy and antibiotic choice. All patients were followed for 30 days.

Results: Over the one-year study period, 44 cases received mandatory infectious disease consultation. Thirty-nine (89%) of these had some change in antibiotic regimen after the consultation. Seventeen patients (39%) were switched to oral antibiotics, 13 (30%) had a change in infectious disease antibiotic, and 5 (11%) had a change in antibiotic dose.

Skin and skin structure and intra-abdominal infections were the most common diagnoses for which antibiotics were changed; a typical change was from intravenous piperacillin/tazobactam to an oral fluoroquinolone plus oral anaerobic coverage. At 30-day follow-up, 98% of patients finished their courses without relapse or complication. The overall costs savings was $27,500 or $1,550 per patient consulted upon.

Discussion: Although from a small, nonrandomized, single-institution study, the results are impressive. Mandatory infectious disease consultation prior to discharge for patients scheduled to received outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy resulted in substantial cost savings, and streamlined and more appropriate antibiotic regimens without any adverse impact on outcomes. Hospitalists should take two things away from this study: 1) consider consulting infection disease specialists on all patients who might be candidates for home IV antibiotics and 2) be aware that many skin and skin tissue and intra-abdominal infections can often be treated with oral therapy. TH