User login

What can you do with a quarter of a million dollars? In some places, that amount can buy a home that can shelter a family for decades. In other places, it is enough to pay annual malpractice insurance premiums for physicians practicing in high-risk specialties—with a little left over.

But if you wanted to use that money for an enduring healthcare project that would provide the most good for the most people, how would you do it? Hospitalists can look to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) for stellar examples of well-invested dollars with excellent return.

AHRQ Funding

With a staff of approximately 300, the tiny AHRQ is the lead federal agency charged with improving the quality, safety, efficiency, and effectiveness of healthcare for all Americans. It creates a priority research agenda annually, and funds studies in areas where improvement is deemed most needed. These include patient safety, data development, pharmaceutical outcomes, and other areas described on its Web site (www.ahrq.gov/).

In 2005, AHRQ announced its Partnerships in Implementing Patient Safety (PIPS) and committed up to $9 million in total costs to fund new grants of less than $300,000 per year, lasting two years. AHRQ indicated that eligible safe practice intervention projects would be required to include “tool kits,” and a comprehensive implementation tool kit to help others overcome barriers and allay adoption concerns. AHRQ’s goal was and is to disseminate funded projects’ perfected tools widely for adaptation and/or adoption by diverse healthcare settings.

AHRQ asked that principal investigators (PIs) be experienced senior level individuals familiar with implementing change in healthcare settings. Their expectation was that PIs would devote at least 15% of their time to the project for its duration. Thus the competitive challenge to potential PIs was great:

- Select a worthy project from among the endless areas where healthcare needs improvement, and then plan specific, realistic, achievable interventions that could create measurable improvement over two years;

- Implement the program; and

- Develop a plan and tools so basic and user-friendly that they could feasibly be applied in not just the local practice setting, but in other healthcare settings.

Although the size and duration of the awards varied, many of the 17 projects they funded received slightly more than a quarter of a million dollars. Among the funded projects, two boast hospitalists as their PIs and address areas of obvious concern in most healthcare settings. Greg Maynard, MD, MS, at the University of California, San Diego, was funded to implement a venous thromboembolism (VTE) intervention program. And Mark V. Williams, MD, FACP, professor of medicine, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, and editor of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, was funded to implement a discharge bundle of patient safety interventions respectively.

Stalking the Silent Killer

Dr. Maynard’s project, “Optimal Prevention of Hospital Acquired Venous Thromboembolism,” focuses on eliminating preventable hospital-acquired VTE at an academic healthcare facility that has a large population of Hispanic patients.

The project’s timeliness and utility is clear: Although the exact incidence of VTE is unknown, experts estimate that approximately 260,000 are clinically recognized annually in acutely hospitalized patients.1 Pulmonary embolism (PE) resulting from deep vein thrombosis (DVT) is the most common cause of preventable hospital death, the majority of hospitalized patients with risk factors for DVT receive no prophylaxis, and the rate of fatal PE more than doubles between age 50 and 80.2,3 The problem is easily recognizable, but “Getting people to do what they need to do to prevent VTE can be hard,” says Dr. Maynard.

This project was carefully planned. It used a rigorous quality improvement process, involving all appropriate clinicians, nurses, managers, and technical support personnel.

Dr. Maynard and his team anticipated roadblocks and negotiated in advance to reduce their effects. They accepted that when patients are hospitalized, things frequently happen that cause physicians to stop VTE prophylaxis: A hemoglobin or platelet count may fall, the patient may have difficulty taking the drug, or the patient’s status may change abruptly. Or the prophylaxis might be accidentally discontinued—perhaps when a patient is transferred.

The team also looked at other institutions’ solutions. Then, using a basic understanding of the ways in which their process was missing VTE prophylaxis opportunities, they built interventions.

This team considered logistics carefully because it was clear that the only intervention that could decrease risk would have to be repetitive in nature. “The process we ultimately selected is very, very quick, yet valid,” says Dr. Maynard, while acknowledging that presenting any intervention repeatedly has the potential to interfere with care. “Other models require the physician to use math and add points. This one does not, and takes only seconds.”

Beginning April 19, 2006, the University of California, San Diego (UCSD) will introduce an intervention that presents a VTE risk assessment screen on every patient who is admitted. This process inquires about the need for prophylaxis every three days for the duration of hospitalization, and physicians cannot skip the screen. If risk factors are present and bleeding risk is not, the screen presents appropriate VTE options.

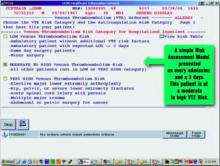

For example, the system will suggest enoxaparin 40 mg daily, enoxaparin 30 mg twice daily, or appropriately dosed warfarin for a high-risk orthopedic surgery patient who has no bleeding risk. Every three days, the process repeats itself, making explicit decisions or suggestions about appropriate prophylaxis. (Figure 1, below, shows a sample screen for a patient with moderately high risk.

Much evidence about VTE is still being gathered. For example, opinions vary about when to start prophylaxis or how long to continue it. Dr. Maynard and his team also addressed real versus relative contraindications—another area of debate among clinicians. Many clinicians are uncertain about how soon after surgery to restart VTE prophylaxis. After orthopedic spine surgery, for example, some might start it on day five, while others may not restart prophylaxis even after day 10. At UCSD, clinical stakeholders in the process came to consensus, and now all restart by day seven.

The tool kit UCSD is developing recognizes that every institution is unique. Those that choose to implement a similar program must identify their baseline rate of VTE and monitor change over time to determine if progress is being made. Every institution must define adequate VTE prophylaxis and tailor the tools appropriately.

Wait? No Need

One compelling aspect of Dr. Maynard’s project is that some of UCSD’s VTE tools are already available on the SHM Web site in the “VTE Resource Room.” With or without AHRQ funding, UCSD planned to develop and implement a VTE awareness program. UCSD’s grant department provided the support Dr. Maynard and his colleagues needed to apply for the AHRQ funding, and Dr. Maynard says the funding they received helped UCSD “disseminate the program better and to carry it out with more rigor.”

UCSD worked with SHM to develop the tool kit. In return, SHM is providing and promoting the VTE tool kit at no charge to interested parties. Additionally, SHM recently received funding via an unrestricted sponsorship to create a mentored implementation project for the “VTE Resource Room.” Interested institutions will be mentored by UCSD staff who have experience with the tool kit.

Over time, Dr. Maynard will measure the effects of the intervention to ensure it is working. In addition to creating a malleable tool kit, UCSD research hospitalists will examine race, gender, and age to determine the effects of these on the likelihood of getting adequate prophylaxis.

Hospital Patient Safe-D(ischarge)

Dr. Williams and his colleagues at Emory University and the University of Ottawa received funding for “Hospital Patient Safe-D(ischarge): A Discharge Bundle for Patients,” a program that builds on previous AHRQ funding. This intervention implements a “discharge bundle” of patient safety interventions to improve patient transition from the hospital to home or another healthcare setting.

“We hope that every patient will undergo discharge, and of course the majority do, but the discharge process has almost been treated as an afterthought,” explains Dr. Williams. “Doctors spend a lot of time on diagnosis and treatment, but not on discharge. This process of transition from total care with a call button, lots of nursing attention, daily visits from the doctor, and delivered meals to greater independence, has not been well researched.”

What little research exists tends to indicate that discharge processes are very heterogeneous.

So far, Dr. Williams’ team’s examination of the process has produced only one surprise: The team has discovered that the discharge process is even more capricious than they suspected. As patients prepare to leave the hospital, what could and should be an orderly process that educates and prepares patients to assume responsibility for their own care in a new and better way is often interrupted or disjointed.

Preparing patients for discharge once fell to the nursing staff. As nursing faces staffing shortages and expanded roles, the discharge process often belongs to everyone and to no one. That physicians’ discharge visits pay much less than the time required to do it well also complicates the problem. The researchers were not surprised, however, to learn that many patients do not know their diagnosis or treatment plan as discharge is imminent. Their goal is to develop a consistent, comprehensive discharge process that will be a national model.

Here again, the precepts of continuous quality improvement are apparent. Dr. Williams’ team’s effort represents collaboration among physicians, pharmacists, nurses, and patients; involves SHM and several other professional organizations; and calls upon an advisory committee consisting of nationally recognized patient care and safety experts.

The discharge bundle of patient safety interventions—a concept advocated by the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations and other quality-promoting groups—adds a post-discharge continuity check to medication reconciliation and patient-centered education at discharge.

The four project phases—implement, evaluate, develop a tool, and disseminate the discharge bundle—overlap and ensure success.

Dr. Williams believes that the group of patients most likely to benefit from this intervention is the elderly. “The elderly bear the greatest burden of chronic disease and typically have several concurrent health problems,” he says.

Educating elders at the time of discharge should decrease the medication error rate and improve adherence to other treatments and recommended lifestyle changes. To gauge the appropriateness of the discharge bundle, John Banja, PhD, an expert in communication and safety, observes the discharge process directly. All communications must be patient-centered, and thus presented in a manner that patients will understand and appreciate. Banja relies on his background in patient safety and disability/rehabilitation to assess the discharge process.

Initial enrollment in this study seems successful. More than 50 patients have consented to participate, but Banja projects a need for 200 to complete the entire process. Recently, the team increased its planned maximum accrual to 300 to increase the statistical power of their findings. The participants like the program because most of them find discharge somewhat discomforting. Patients know they have knowledge gaps and appreciate clinicians’ efforts to fill those gaps seamlessly. A small investment of time can prevent problems after discharge.

Added Value

Clearly, the findings from these AHRQ-funded studies have the potential to reduce morbidity and mortality in a logarithmic manner as other institutions adapt these new tool kits. Dr. Williams indicates that recipients of PIPS funding receive more than just funding and the satisfaction of creating tools that will help all Americans.

“The AHRQ sponsors quarterly conference calls for all participants, regardless of their research topic, and an annual meeting in June to bring all investigators together,” he says.

The opportunity to learn how others address problems, plan interventions, and tackle hurdles proves invaluable. In addition, being privy to interim study results or learning how others handle research dilemmas helps hospitalists expand their skill sets.

Listening to Drs. Maynard and Williams is a not-so-subtle reminder that every hospital needs a well-structured quality improvement plan, and that hospitalists are essential in the plan’s success. Every hospitalist needs an understanding of the precepts these PIs used to earn this well-deserved funding: interdisciplinary and professional organization collaboration, good communication, realistic planning, managing change by measuring, and above all, sharing success. TH

Jeannette Yeznach Wick, RPh, MBA, FASCP, is a freelance medical writer based in Arlington, Va.

References

- Anderson FA Jr, Wheeler HB, Goldberg RJ, et al. A population-based perspective of the hospital incidence and case-fatality rates of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. The Worcester DVT Study. Arch Intern Med. 1991 May;151(5):933-938.

- Clagett GP, Anderson FA Jr, Heit J, et al. Prevention of venous thromboembolism. Chest. 1995 Oct;108(4 Suppl):312S-334S.

- Geerts WH, Heit JA, Clagett GP, et al. Prevention of venous thromboembolism. Chest. 2001;119(1 Suppl):132S-175S.

What can you do with a quarter of a million dollars? In some places, that amount can buy a home that can shelter a family for decades. In other places, it is enough to pay annual malpractice insurance premiums for physicians practicing in high-risk specialties—with a little left over.

But if you wanted to use that money for an enduring healthcare project that would provide the most good for the most people, how would you do it? Hospitalists can look to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) for stellar examples of well-invested dollars with excellent return.

AHRQ Funding

With a staff of approximately 300, the tiny AHRQ is the lead federal agency charged with improving the quality, safety, efficiency, and effectiveness of healthcare for all Americans. It creates a priority research agenda annually, and funds studies in areas where improvement is deemed most needed. These include patient safety, data development, pharmaceutical outcomes, and other areas described on its Web site (www.ahrq.gov/).

In 2005, AHRQ announced its Partnerships in Implementing Patient Safety (PIPS) and committed up to $9 million in total costs to fund new grants of less than $300,000 per year, lasting two years. AHRQ indicated that eligible safe practice intervention projects would be required to include “tool kits,” and a comprehensive implementation tool kit to help others overcome barriers and allay adoption concerns. AHRQ’s goal was and is to disseminate funded projects’ perfected tools widely for adaptation and/or adoption by diverse healthcare settings.

AHRQ asked that principal investigators (PIs) be experienced senior level individuals familiar with implementing change in healthcare settings. Their expectation was that PIs would devote at least 15% of their time to the project for its duration. Thus the competitive challenge to potential PIs was great:

- Select a worthy project from among the endless areas where healthcare needs improvement, and then plan specific, realistic, achievable interventions that could create measurable improvement over two years;

- Implement the program; and

- Develop a plan and tools so basic and user-friendly that they could feasibly be applied in not just the local practice setting, but in other healthcare settings.

Although the size and duration of the awards varied, many of the 17 projects they funded received slightly more than a quarter of a million dollars. Among the funded projects, two boast hospitalists as their PIs and address areas of obvious concern in most healthcare settings. Greg Maynard, MD, MS, at the University of California, San Diego, was funded to implement a venous thromboembolism (VTE) intervention program. And Mark V. Williams, MD, FACP, professor of medicine, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, and editor of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, was funded to implement a discharge bundle of patient safety interventions respectively.

Stalking the Silent Killer

Dr. Maynard’s project, “Optimal Prevention of Hospital Acquired Venous Thromboembolism,” focuses on eliminating preventable hospital-acquired VTE at an academic healthcare facility that has a large population of Hispanic patients.

The project’s timeliness and utility is clear: Although the exact incidence of VTE is unknown, experts estimate that approximately 260,000 are clinically recognized annually in acutely hospitalized patients.1 Pulmonary embolism (PE) resulting from deep vein thrombosis (DVT) is the most common cause of preventable hospital death, the majority of hospitalized patients with risk factors for DVT receive no prophylaxis, and the rate of fatal PE more than doubles between age 50 and 80.2,3 The problem is easily recognizable, but “Getting people to do what they need to do to prevent VTE can be hard,” says Dr. Maynard.

This project was carefully planned. It used a rigorous quality improvement process, involving all appropriate clinicians, nurses, managers, and technical support personnel.

Dr. Maynard and his team anticipated roadblocks and negotiated in advance to reduce their effects. They accepted that when patients are hospitalized, things frequently happen that cause physicians to stop VTE prophylaxis: A hemoglobin or platelet count may fall, the patient may have difficulty taking the drug, or the patient’s status may change abruptly. Or the prophylaxis might be accidentally discontinued—perhaps when a patient is transferred.

The team also looked at other institutions’ solutions. Then, using a basic understanding of the ways in which their process was missing VTE prophylaxis opportunities, they built interventions.

This team considered logistics carefully because it was clear that the only intervention that could decrease risk would have to be repetitive in nature. “The process we ultimately selected is very, very quick, yet valid,” says Dr. Maynard, while acknowledging that presenting any intervention repeatedly has the potential to interfere with care. “Other models require the physician to use math and add points. This one does not, and takes only seconds.”

Beginning April 19, 2006, the University of California, San Diego (UCSD) will introduce an intervention that presents a VTE risk assessment screen on every patient who is admitted. This process inquires about the need for prophylaxis every three days for the duration of hospitalization, and physicians cannot skip the screen. If risk factors are present and bleeding risk is not, the screen presents appropriate VTE options.

For example, the system will suggest enoxaparin 40 mg daily, enoxaparin 30 mg twice daily, or appropriately dosed warfarin for a high-risk orthopedic surgery patient who has no bleeding risk. Every three days, the process repeats itself, making explicit decisions or suggestions about appropriate prophylaxis. (Figure 1, below, shows a sample screen for a patient with moderately high risk.

Much evidence about VTE is still being gathered. For example, opinions vary about when to start prophylaxis or how long to continue it. Dr. Maynard and his team also addressed real versus relative contraindications—another area of debate among clinicians. Many clinicians are uncertain about how soon after surgery to restart VTE prophylaxis. After orthopedic spine surgery, for example, some might start it on day five, while others may not restart prophylaxis even after day 10. At UCSD, clinical stakeholders in the process came to consensus, and now all restart by day seven.

The tool kit UCSD is developing recognizes that every institution is unique. Those that choose to implement a similar program must identify their baseline rate of VTE and monitor change over time to determine if progress is being made. Every institution must define adequate VTE prophylaxis and tailor the tools appropriately.

Wait? No Need

One compelling aspect of Dr. Maynard’s project is that some of UCSD’s VTE tools are already available on the SHM Web site in the “VTE Resource Room.” With or without AHRQ funding, UCSD planned to develop and implement a VTE awareness program. UCSD’s grant department provided the support Dr. Maynard and his colleagues needed to apply for the AHRQ funding, and Dr. Maynard says the funding they received helped UCSD “disseminate the program better and to carry it out with more rigor.”

UCSD worked with SHM to develop the tool kit. In return, SHM is providing and promoting the VTE tool kit at no charge to interested parties. Additionally, SHM recently received funding via an unrestricted sponsorship to create a mentored implementation project for the “VTE Resource Room.” Interested institutions will be mentored by UCSD staff who have experience with the tool kit.

Over time, Dr. Maynard will measure the effects of the intervention to ensure it is working. In addition to creating a malleable tool kit, UCSD research hospitalists will examine race, gender, and age to determine the effects of these on the likelihood of getting adequate prophylaxis.

Hospital Patient Safe-D(ischarge)

Dr. Williams and his colleagues at Emory University and the University of Ottawa received funding for “Hospital Patient Safe-D(ischarge): A Discharge Bundle for Patients,” a program that builds on previous AHRQ funding. This intervention implements a “discharge bundle” of patient safety interventions to improve patient transition from the hospital to home or another healthcare setting.

“We hope that every patient will undergo discharge, and of course the majority do, but the discharge process has almost been treated as an afterthought,” explains Dr. Williams. “Doctors spend a lot of time on diagnosis and treatment, but not on discharge. This process of transition from total care with a call button, lots of nursing attention, daily visits from the doctor, and delivered meals to greater independence, has not been well researched.”

What little research exists tends to indicate that discharge processes are very heterogeneous.

So far, Dr. Williams’ team’s examination of the process has produced only one surprise: The team has discovered that the discharge process is even more capricious than they suspected. As patients prepare to leave the hospital, what could and should be an orderly process that educates and prepares patients to assume responsibility for their own care in a new and better way is often interrupted or disjointed.

Preparing patients for discharge once fell to the nursing staff. As nursing faces staffing shortages and expanded roles, the discharge process often belongs to everyone and to no one. That physicians’ discharge visits pay much less than the time required to do it well also complicates the problem. The researchers were not surprised, however, to learn that many patients do not know their diagnosis or treatment plan as discharge is imminent. Their goal is to develop a consistent, comprehensive discharge process that will be a national model.

Here again, the precepts of continuous quality improvement are apparent. Dr. Williams’ team’s effort represents collaboration among physicians, pharmacists, nurses, and patients; involves SHM and several other professional organizations; and calls upon an advisory committee consisting of nationally recognized patient care and safety experts.

The discharge bundle of patient safety interventions—a concept advocated by the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations and other quality-promoting groups—adds a post-discharge continuity check to medication reconciliation and patient-centered education at discharge.

The four project phases—implement, evaluate, develop a tool, and disseminate the discharge bundle—overlap and ensure success.

Dr. Williams believes that the group of patients most likely to benefit from this intervention is the elderly. “The elderly bear the greatest burden of chronic disease and typically have several concurrent health problems,” he says.

Educating elders at the time of discharge should decrease the medication error rate and improve adherence to other treatments and recommended lifestyle changes. To gauge the appropriateness of the discharge bundle, John Banja, PhD, an expert in communication and safety, observes the discharge process directly. All communications must be patient-centered, and thus presented in a manner that patients will understand and appreciate. Banja relies on his background in patient safety and disability/rehabilitation to assess the discharge process.

Initial enrollment in this study seems successful. More than 50 patients have consented to participate, but Banja projects a need for 200 to complete the entire process. Recently, the team increased its planned maximum accrual to 300 to increase the statistical power of their findings. The participants like the program because most of them find discharge somewhat discomforting. Patients know they have knowledge gaps and appreciate clinicians’ efforts to fill those gaps seamlessly. A small investment of time can prevent problems after discharge.

Added Value

Clearly, the findings from these AHRQ-funded studies have the potential to reduce morbidity and mortality in a logarithmic manner as other institutions adapt these new tool kits. Dr. Williams indicates that recipients of PIPS funding receive more than just funding and the satisfaction of creating tools that will help all Americans.

“The AHRQ sponsors quarterly conference calls for all participants, regardless of their research topic, and an annual meeting in June to bring all investigators together,” he says.

The opportunity to learn how others address problems, plan interventions, and tackle hurdles proves invaluable. In addition, being privy to interim study results or learning how others handle research dilemmas helps hospitalists expand their skill sets.

Listening to Drs. Maynard and Williams is a not-so-subtle reminder that every hospital needs a well-structured quality improvement plan, and that hospitalists are essential in the plan’s success. Every hospitalist needs an understanding of the precepts these PIs used to earn this well-deserved funding: interdisciplinary and professional organization collaboration, good communication, realistic planning, managing change by measuring, and above all, sharing success. TH

Jeannette Yeznach Wick, RPh, MBA, FASCP, is a freelance medical writer based in Arlington, Va.

References

- Anderson FA Jr, Wheeler HB, Goldberg RJ, et al. A population-based perspective of the hospital incidence and case-fatality rates of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. The Worcester DVT Study. Arch Intern Med. 1991 May;151(5):933-938.

- Clagett GP, Anderson FA Jr, Heit J, et al. Prevention of venous thromboembolism. Chest. 1995 Oct;108(4 Suppl):312S-334S.

- Geerts WH, Heit JA, Clagett GP, et al. Prevention of venous thromboembolism. Chest. 2001;119(1 Suppl):132S-175S.

What can you do with a quarter of a million dollars? In some places, that amount can buy a home that can shelter a family for decades. In other places, it is enough to pay annual malpractice insurance premiums for physicians practicing in high-risk specialties—with a little left over.

But if you wanted to use that money for an enduring healthcare project that would provide the most good for the most people, how would you do it? Hospitalists can look to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) for stellar examples of well-invested dollars with excellent return.

AHRQ Funding

With a staff of approximately 300, the tiny AHRQ is the lead federal agency charged with improving the quality, safety, efficiency, and effectiveness of healthcare for all Americans. It creates a priority research agenda annually, and funds studies in areas where improvement is deemed most needed. These include patient safety, data development, pharmaceutical outcomes, and other areas described on its Web site (www.ahrq.gov/).

In 2005, AHRQ announced its Partnerships in Implementing Patient Safety (PIPS) and committed up to $9 million in total costs to fund new grants of less than $300,000 per year, lasting two years. AHRQ indicated that eligible safe practice intervention projects would be required to include “tool kits,” and a comprehensive implementation tool kit to help others overcome barriers and allay adoption concerns. AHRQ’s goal was and is to disseminate funded projects’ perfected tools widely for adaptation and/or adoption by diverse healthcare settings.

AHRQ asked that principal investigators (PIs) be experienced senior level individuals familiar with implementing change in healthcare settings. Their expectation was that PIs would devote at least 15% of their time to the project for its duration. Thus the competitive challenge to potential PIs was great:

- Select a worthy project from among the endless areas where healthcare needs improvement, and then plan specific, realistic, achievable interventions that could create measurable improvement over two years;

- Implement the program; and

- Develop a plan and tools so basic and user-friendly that they could feasibly be applied in not just the local practice setting, but in other healthcare settings.

Although the size and duration of the awards varied, many of the 17 projects they funded received slightly more than a quarter of a million dollars. Among the funded projects, two boast hospitalists as their PIs and address areas of obvious concern in most healthcare settings. Greg Maynard, MD, MS, at the University of California, San Diego, was funded to implement a venous thromboembolism (VTE) intervention program. And Mark V. Williams, MD, FACP, professor of medicine, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, and editor of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, was funded to implement a discharge bundle of patient safety interventions respectively.

Stalking the Silent Killer

Dr. Maynard’s project, “Optimal Prevention of Hospital Acquired Venous Thromboembolism,” focuses on eliminating preventable hospital-acquired VTE at an academic healthcare facility that has a large population of Hispanic patients.

The project’s timeliness and utility is clear: Although the exact incidence of VTE is unknown, experts estimate that approximately 260,000 are clinically recognized annually in acutely hospitalized patients.1 Pulmonary embolism (PE) resulting from deep vein thrombosis (DVT) is the most common cause of preventable hospital death, the majority of hospitalized patients with risk factors for DVT receive no prophylaxis, and the rate of fatal PE more than doubles between age 50 and 80.2,3 The problem is easily recognizable, but “Getting people to do what they need to do to prevent VTE can be hard,” says Dr. Maynard.

This project was carefully planned. It used a rigorous quality improvement process, involving all appropriate clinicians, nurses, managers, and technical support personnel.

Dr. Maynard and his team anticipated roadblocks and negotiated in advance to reduce their effects. They accepted that when patients are hospitalized, things frequently happen that cause physicians to stop VTE prophylaxis: A hemoglobin or platelet count may fall, the patient may have difficulty taking the drug, or the patient’s status may change abruptly. Or the prophylaxis might be accidentally discontinued—perhaps when a patient is transferred.

The team also looked at other institutions’ solutions. Then, using a basic understanding of the ways in which their process was missing VTE prophylaxis opportunities, they built interventions.

This team considered logistics carefully because it was clear that the only intervention that could decrease risk would have to be repetitive in nature. “The process we ultimately selected is very, very quick, yet valid,” says Dr. Maynard, while acknowledging that presenting any intervention repeatedly has the potential to interfere with care. “Other models require the physician to use math and add points. This one does not, and takes only seconds.”

Beginning April 19, 2006, the University of California, San Diego (UCSD) will introduce an intervention that presents a VTE risk assessment screen on every patient who is admitted. This process inquires about the need for prophylaxis every three days for the duration of hospitalization, and physicians cannot skip the screen. If risk factors are present and bleeding risk is not, the screen presents appropriate VTE options.

For example, the system will suggest enoxaparin 40 mg daily, enoxaparin 30 mg twice daily, or appropriately dosed warfarin for a high-risk orthopedic surgery patient who has no bleeding risk. Every three days, the process repeats itself, making explicit decisions or suggestions about appropriate prophylaxis. (Figure 1, below, shows a sample screen for a patient with moderately high risk.

Much evidence about VTE is still being gathered. For example, opinions vary about when to start prophylaxis or how long to continue it. Dr. Maynard and his team also addressed real versus relative contraindications—another area of debate among clinicians. Many clinicians are uncertain about how soon after surgery to restart VTE prophylaxis. After orthopedic spine surgery, for example, some might start it on day five, while others may not restart prophylaxis even after day 10. At UCSD, clinical stakeholders in the process came to consensus, and now all restart by day seven.

The tool kit UCSD is developing recognizes that every institution is unique. Those that choose to implement a similar program must identify their baseline rate of VTE and monitor change over time to determine if progress is being made. Every institution must define adequate VTE prophylaxis and tailor the tools appropriately.

Wait? No Need

One compelling aspect of Dr. Maynard’s project is that some of UCSD’s VTE tools are already available on the SHM Web site in the “VTE Resource Room.” With or without AHRQ funding, UCSD planned to develop and implement a VTE awareness program. UCSD’s grant department provided the support Dr. Maynard and his colleagues needed to apply for the AHRQ funding, and Dr. Maynard says the funding they received helped UCSD “disseminate the program better and to carry it out with more rigor.”

UCSD worked with SHM to develop the tool kit. In return, SHM is providing and promoting the VTE tool kit at no charge to interested parties. Additionally, SHM recently received funding via an unrestricted sponsorship to create a mentored implementation project for the “VTE Resource Room.” Interested institutions will be mentored by UCSD staff who have experience with the tool kit.

Over time, Dr. Maynard will measure the effects of the intervention to ensure it is working. In addition to creating a malleable tool kit, UCSD research hospitalists will examine race, gender, and age to determine the effects of these on the likelihood of getting adequate prophylaxis.

Hospital Patient Safe-D(ischarge)

Dr. Williams and his colleagues at Emory University and the University of Ottawa received funding for “Hospital Patient Safe-D(ischarge): A Discharge Bundle for Patients,” a program that builds on previous AHRQ funding. This intervention implements a “discharge bundle” of patient safety interventions to improve patient transition from the hospital to home or another healthcare setting.

“We hope that every patient will undergo discharge, and of course the majority do, but the discharge process has almost been treated as an afterthought,” explains Dr. Williams. “Doctors spend a lot of time on diagnosis and treatment, but not on discharge. This process of transition from total care with a call button, lots of nursing attention, daily visits from the doctor, and delivered meals to greater independence, has not been well researched.”

What little research exists tends to indicate that discharge processes are very heterogeneous.

So far, Dr. Williams’ team’s examination of the process has produced only one surprise: The team has discovered that the discharge process is even more capricious than they suspected. As patients prepare to leave the hospital, what could and should be an orderly process that educates and prepares patients to assume responsibility for their own care in a new and better way is often interrupted or disjointed.

Preparing patients for discharge once fell to the nursing staff. As nursing faces staffing shortages and expanded roles, the discharge process often belongs to everyone and to no one. That physicians’ discharge visits pay much less than the time required to do it well also complicates the problem. The researchers were not surprised, however, to learn that many patients do not know their diagnosis or treatment plan as discharge is imminent. Their goal is to develop a consistent, comprehensive discharge process that will be a national model.

Here again, the precepts of continuous quality improvement are apparent. Dr. Williams’ team’s effort represents collaboration among physicians, pharmacists, nurses, and patients; involves SHM and several other professional organizations; and calls upon an advisory committee consisting of nationally recognized patient care and safety experts.

The discharge bundle of patient safety interventions—a concept advocated by the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations and other quality-promoting groups—adds a post-discharge continuity check to medication reconciliation and patient-centered education at discharge.

The four project phases—implement, evaluate, develop a tool, and disseminate the discharge bundle—overlap and ensure success.

Dr. Williams believes that the group of patients most likely to benefit from this intervention is the elderly. “The elderly bear the greatest burden of chronic disease and typically have several concurrent health problems,” he says.

Educating elders at the time of discharge should decrease the medication error rate and improve adherence to other treatments and recommended lifestyle changes. To gauge the appropriateness of the discharge bundle, John Banja, PhD, an expert in communication and safety, observes the discharge process directly. All communications must be patient-centered, and thus presented in a manner that patients will understand and appreciate. Banja relies on his background in patient safety and disability/rehabilitation to assess the discharge process.

Initial enrollment in this study seems successful. More than 50 patients have consented to participate, but Banja projects a need for 200 to complete the entire process. Recently, the team increased its planned maximum accrual to 300 to increase the statistical power of their findings. The participants like the program because most of them find discharge somewhat discomforting. Patients know they have knowledge gaps and appreciate clinicians’ efforts to fill those gaps seamlessly. A small investment of time can prevent problems after discharge.

Added Value

Clearly, the findings from these AHRQ-funded studies have the potential to reduce morbidity and mortality in a logarithmic manner as other institutions adapt these new tool kits. Dr. Williams indicates that recipients of PIPS funding receive more than just funding and the satisfaction of creating tools that will help all Americans.

“The AHRQ sponsors quarterly conference calls for all participants, regardless of their research topic, and an annual meeting in June to bring all investigators together,” he says.

The opportunity to learn how others address problems, plan interventions, and tackle hurdles proves invaluable. In addition, being privy to interim study results or learning how others handle research dilemmas helps hospitalists expand their skill sets.

Listening to Drs. Maynard and Williams is a not-so-subtle reminder that every hospital needs a well-structured quality improvement plan, and that hospitalists are essential in the plan’s success. Every hospitalist needs an understanding of the precepts these PIs used to earn this well-deserved funding: interdisciplinary and professional organization collaboration, good communication, realistic planning, managing change by measuring, and above all, sharing success. TH

Jeannette Yeznach Wick, RPh, MBA, FASCP, is a freelance medical writer based in Arlington, Va.

References

- Anderson FA Jr, Wheeler HB, Goldberg RJ, et al. A population-based perspective of the hospital incidence and case-fatality rates of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. The Worcester DVT Study. Arch Intern Med. 1991 May;151(5):933-938.

- Clagett GP, Anderson FA Jr, Heit J, et al. Prevention of venous thromboembolism. Chest. 1995 Oct;108(4 Suppl):312S-334S.

- Geerts WH, Heit JA, Clagett GP, et al. Prevention of venous thromboembolism. Chest. 2001;119(1 Suppl):132S-175S.