User login

Code nearly all visits at the highest level” was the entire orientation I got to CPT coding when I first started practice as a hospitalist in the 1980s.

I couldn’t believe this advice, which came from another physician, was sound—and it isn’t. So I tried to learn a little more about the subject on my own. After a year or so of somewhat futile self-education in coding, I decided I could never learn the very confusing rules and chose to do nearly the opposite of the “code all visits high” strategy: I coded nearly all visits at very low levels.

While some hospitalists are experts at proper CPT coding, I think a lot (the majority?) feel uneasy and do what I tended to do years ago: They “downcode” many visits, believing this will provide a margin of safety against being audited and accused of “upcoding.” The problem with this approach is that it can cost your practice significant professional fee revenue. And according to the letter of the law, downcoding is just as illegal as upcoding. (Though I haven’t seen any newspaper headlines about Medicare creating teams of auditors to stamp out illegal downcoding.)

Strategies to Improve

If you’re like many hospitalists and feel uneasy about how accurately you’re choosing CPT codes, I have a few suggestions.

First, SHM has a new course on CPT coding designed specifically for hospitalists. The next meetings are Oct. 3 in San Francisco and April 3, 2008, in San Diego as a precourse to SHM’s Annual Meeting 2008. The previous versions of the course have received high praise.

There are also a number of strategies your hospitalist group can use to help ensure proper coding stays on each doctor’s mind. Some organizations have an internal coding expert who might regularly review each doctor’s coding and provide education to address problem areas. Whether you have such an internal expert or not, you should probably have an annual audit by an external certified coder—someone who has no financial connection to your institution.

In addition to external resources, I think every group should create a monthly or quarterly report that allows each doctor to see his or her own pattern of coding compared with that of everyone else in the group. This will be most valuable if everyone’s name remains visible to everyone else. It should then be easy for me to tell that I code discharges at the low level far more often than the group average. I should be able to see that my partner Jane codes half of initial consult visits at the highest level and I code most of them much lower.

It would be unusual that this information would lead to strife and dissent within the group. If it does, you probably have significant cultural and interpersonal problems within your group. It will usually lead to the doctors talking about their patterns of documenting and coding among themselves—which goes a long way to keep the issue on everyone’s mind.

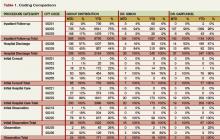

One format for such a report is on p. 61. CPT codes are grouped by category on the left side. The next set of columns is labeled “group distribution” and shows the month-to-date (MTD) and running 12-month (YTD) distribution of codes for all doctors in the group. Specific data for two doctors in the group is to the right of the group distribution. Note that there are more than 10 doctors in this hypothetical group, but I have shown only two of them because of space limitations.

When reviewing this table, Dr. Simon may get a little uncomfortable because she codes only 2% of follow-up visits at the highest level, but the group as a whole uses the highest code 17% of the time. And, she codes 88% of discharges at the high level, compared with 44% for the group as a whole. She is also out of step with her partners in highest initial consult and the middle initial observation codes. This information will probably make her receptive to peer-to-peer learning from her partners and may motivate her to review some of the coding rules.

Dr. Simon and Dr. Garfunkel are out of step with the group in how often they use the code for the middle level initial observation visit. This group needs to investigate whether these two doctors are coding these visits correctly, and everyone else is in error, or vice versa.

It is important to point out that the goal of the report isn’t to get each doctor to simply mirror the distribution of the group’s overall coding pattern. There might be cases in which the outlier doctor is coding correctly and everyone else is wrong. So the group average can’t be accepted as correct, and any significant discrepancies between one or two doctors and the group as a whole should be reviewed and discussed.

While a coding comparison table like this isn’t enough to ensure proper coding, it is a useful tool for highlighting the areas most in need of attention. I know of cases in which hospitalists who practiced together for several years had no idea their coding patterns were so dramatically different until they created a report like this. TH

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988 and is co-founder and past president of SHM. He is a principal in Nelson/Flores Associates, a national hospitalist practice management consulting firm. This column represents his views and is not intended to reflect an official position of SHM.

Code nearly all visits at the highest level” was the entire orientation I got to CPT coding when I first started practice as a hospitalist in the 1980s.

I couldn’t believe this advice, which came from another physician, was sound—and it isn’t. So I tried to learn a little more about the subject on my own. After a year or so of somewhat futile self-education in coding, I decided I could never learn the very confusing rules and chose to do nearly the opposite of the “code all visits high” strategy: I coded nearly all visits at very low levels.

While some hospitalists are experts at proper CPT coding, I think a lot (the majority?) feel uneasy and do what I tended to do years ago: They “downcode” many visits, believing this will provide a margin of safety against being audited and accused of “upcoding.” The problem with this approach is that it can cost your practice significant professional fee revenue. And according to the letter of the law, downcoding is just as illegal as upcoding. (Though I haven’t seen any newspaper headlines about Medicare creating teams of auditors to stamp out illegal downcoding.)

Strategies to Improve

If you’re like many hospitalists and feel uneasy about how accurately you’re choosing CPT codes, I have a few suggestions.

First, SHM has a new course on CPT coding designed specifically for hospitalists. The next meetings are Oct. 3 in San Francisco and April 3, 2008, in San Diego as a precourse to SHM’s Annual Meeting 2008. The previous versions of the course have received high praise.

There are also a number of strategies your hospitalist group can use to help ensure proper coding stays on each doctor’s mind. Some organizations have an internal coding expert who might regularly review each doctor’s coding and provide education to address problem areas. Whether you have such an internal expert or not, you should probably have an annual audit by an external certified coder—someone who has no financial connection to your institution.

In addition to external resources, I think every group should create a monthly or quarterly report that allows each doctor to see his or her own pattern of coding compared with that of everyone else in the group. This will be most valuable if everyone’s name remains visible to everyone else. It should then be easy for me to tell that I code discharges at the low level far more often than the group average. I should be able to see that my partner Jane codes half of initial consult visits at the highest level and I code most of them much lower.

It would be unusual that this information would lead to strife and dissent within the group. If it does, you probably have significant cultural and interpersonal problems within your group. It will usually lead to the doctors talking about their patterns of documenting and coding among themselves—which goes a long way to keep the issue on everyone’s mind.

One format for such a report is on p. 61. CPT codes are grouped by category on the left side. The next set of columns is labeled “group distribution” and shows the month-to-date (MTD) and running 12-month (YTD) distribution of codes for all doctors in the group. Specific data for two doctors in the group is to the right of the group distribution. Note that there are more than 10 doctors in this hypothetical group, but I have shown only two of them because of space limitations.

When reviewing this table, Dr. Simon may get a little uncomfortable because she codes only 2% of follow-up visits at the highest level, but the group as a whole uses the highest code 17% of the time. And, she codes 88% of discharges at the high level, compared with 44% for the group as a whole. She is also out of step with her partners in highest initial consult and the middle initial observation codes. This information will probably make her receptive to peer-to-peer learning from her partners and may motivate her to review some of the coding rules.

Dr. Simon and Dr. Garfunkel are out of step with the group in how often they use the code for the middle level initial observation visit. This group needs to investigate whether these two doctors are coding these visits correctly, and everyone else is in error, or vice versa.

It is important to point out that the goal of the report isn’t to get each doctor to simply mirror the distribution of the group’s overall coding pattern. There might be cases in which the outlier doctor is coding correctly and everyone else is wrong. So the group average can’t be accepted as correct, and any significant discrepancies between one or two doctors and the group as a whole should be reviewed and discussed.

While a coding comparison table like this isn’t enough to ensure proper coding, it is a useful tool for highlighting the areas most in need of attention. I know of cases in which hospitalists who practiced together for several years had no idea their coding patterns were so dramatically different until they created a report like this. TH

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988 and is co-founder and past president of SHM. He is a principal in Nelson/Flores Associates, a national hospitalist practice management consulting firm. This column represents his views and is not intended to reflect an official position of SHM.

Code nearly all visits at the highest level” was the entire orientation I got to CPT coding when I first started practice as a hospitalist in the 1980s.

I couldn’t believe this advice, which came from another physician, was sound—and it isn’t. So I tried to learn a little more about the subject on my own. After a year or so of somewhat futile self-education in coding, I decided I could never learn the very confusing rules and chose to do nearly the opposite of the “code all visits high” strategy: I coded nearly all visits at very low levels.

While some hospitalists are experts at proper CPT coding, I think a lot (the majority?) feel uneasy and do what I tended to do years ago: They “downcode” many visits, believing this will provide a margin of safety against being audited and accused of “upcoding.” The problem with this approach is that it can cost your practice significant professional fee revenue. And according to the letter of the law, downcoding is just as illegal as upcoding. (Though I haven’t seen any newspaper headlines about Medicare creating teams of auditors to stamp out illegal downcoding.)

Strategies to Improve

If you’re like many hospitalists and feel uneasy about how accurately you’re choosing CPT codes, I have a few suggestions.

First, SHM has a new course on CPT coding designed specifically for hospitalists. The next meetings are Oct. 3 in San Francisco and April 3, 2008, in San Diego as a precourse to SHM’s Annual Meeting 2008. The previous versions of the course have received high praise.

There are also a number of strategies your hospitalist group can use to help ensure proper coding stays on each doctor’s mind. Some organizations have an internal coding expert who might regularly review each doctor’s coding and provide education to address problem areas. Whether you have such an internal expert or not, you should probably have an annual audit by an external certified coder—someone who has no financial connection to your institution.

In addition to external resources, I think every group should create a monthly or quarterly report that allows each doctor to see his or her own pattern of coding compared with that of everyone else in the group. This will be most valuable if everyone’s name remains visible to everyone else. It should then be easy for me to tell that I code discharges at the low level far more often than the group average. I should be able to see that my partner Jane codes half of initial consult visits at the highest level and I code most of them much lower.

It would be unusual that this information would lead to strife and dissent within the group. If it does, you probably have significant cultural and interpersonal problems within your group. It will usually lead to the doctors talking about their patterns of documenting and coding among themselves—which goes a long way to keep the issue on everyone’s mind.

One format for such a report is on p. 61. CPT codes are grouped by category on the left side. The next set of columns is labeled “group distribution” and shows the month-to-date (MTD) and running 12-month (YTD) distribution of codes for all doctors in the group. Specific data for two doctors in the group is to the right of the group distribution. Note that there are more than 10 doctors in this hypothetical group, but I have shown only two of them because of space limitations.

When reviewing this table, Dr. Simon may get a little uncomfortable because she codes only 2% of follow-up visits at the highest level, but the group as a whole uses the highest code 17% of the time. And, she codes 88% of discharges at the high level, compared with 44% for the group as a whole. She is also out of step with her partners in highest initial consult and the middle initial observation codes. This information will probably make her receptive to peer-to-peer learning from her partners and may motivate her to review some of the coding rules.

Dr. Simon and Dr. Garfunkel are out of step with the group in how often they use the code for the middle level initial observation visit. This group needs to investigate whether these two doctors are coding these visits correctly, and everyone else is in error, or vice versa.

It is important to point out that the goal of the report isn’t to get each doctor to simply mirror the distribution of the group’s overall coding pattern. There might be cases in which the outlier doctor is coding correctly and everyone else is wrong. So the group average can’t be accepted as correct, and any significant discrepancies between one or two doctors and the group as a whole should be reviewed and discussed.

While a coding comparison table like this isn’t enough to ensure proper coding, it is a useful tool for highlighting the areas most in need of attention. I know of cases in which hospitalists who practiced together for several years had no idea their coding patterns were so dramatically different until they created a report like this. TH

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988 and is co-founder and past president of SHM. He is a principal in Nelson/Flores Associates, a national hospitalist practice management consulting firm. This column represents his views and is not intended to reflect an official position of SHM.