User login

Continuity Conundrum

Editor’s note: Third of a three-part series.

In the two monthly columns preceding this one, I’ve provided an overview of some ways hospitalist groups distribute new referrals among the providers. This month, I’ll review things that cause some groups to make exceptions to their typical method of distributing patients, and turn from how patients are distributed over 24 hours to thoughts about how they might be assigned over the course of consecutive days worked by a doctor.

Equitable Exceptions

There are a number of reasons groups decide to depart from their typical method of assigning patients. These include:

- “Bouncebacks”;

- One hospitalist is at the cap, others aren’t;

- Consult requested of a specific hospitalist;

- Hospitalists with unique skills (e.g., ICU expertise); and

- A patient “fires” the hospitalist.

There isn’t a standard “hospitalist way” of dealing with these issues, and each group will need to work out its own system. The most common of these issues is “bouncebacks.” Every group should try to have patients readmitted within three or four days of discharge go back to the discharging hospitalist. However, this proves difficult in many cases for several reasons, most commonly because the original discharging doctor might not be working when the patient returns.

The Alpha & Omega

Nearly every hospitalist practice makes some effort to maximize continuity between a single hospitalist and patient over the course of a hospital stay. But the effect of the method of patient assignment on continuity often is overlooked.

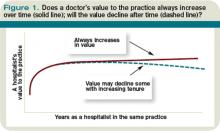

A reasonable way to think about or measure continuity is to estimate the portion of patients seen by the group that see the same hospitalist for each daytime visit over the course of their stay. (Assume that in most HM groups the same hospitalist can’t make both day and night visits over the course of the hospital stay. So, just for simplicity, I’ve intentionally left night visits, including an initial admission visit at night, out of the continuity calculation.) Plug the numbers for your practice into the formula (see Figure 1, right) and see what you get.

If a hospitalist always works seven consecutive day shifts (e.g., a seven-on/seven-off schedule) and the hospitalist’s patients have an average LOS of 4.2 days, then 54% of patients will see the same hospitalist for all daytime visits, and 46% will experience at least one handoff. (To keep things simple, I’m ignoring the effect on continuity of patients being admitted by an “admitter” or nocturnist who doesn’t see the patient subsequently.)

Changing the number of consecutive day shifts a hospitalist works has the most significant impact on continuity, but just how many consecutive days can one work routinely before fatigue and burnout—not too mention increased errors and decreased patient satisfaction—become a problem? (Many hospitalists make the mistake of trying to stuff what might be a reasonable annual workload into the smallest number of shifts possible with the goal of maximizing the number of days off. That means each worked day will be very busy, making it really hard to work many consecutive days. But you always have the option of titrating out that same annual workload over more days so that each day is less busy and it becomes easier to work more consecutive days.)

An often-overlooked way to improve continuity without having to work more consecutive day shifts is to have a hospitalist who is early in their series of worked days take on more new admissions and consults, and perhaps exempt that doctor from taking on new referrals for the last day or two he or she is on service. Eric Howell, MD, FHM, an SHM board member, calls this method “slam and dwindle.” This has been the approach I’ve experienced my whole career, and it is hard for me to imagine doing it any other way.

Here’s how it might work: Let’s say Dr. Petty always works seven consecutive day shifts, and on the first day he picks up a list of patients remaining from the doctor he’s replacing. To keep things simple, let’s assume he’s not in a large group, and during his first day of seven days on service he accepts and “keeps” all new referrals to the practice. On each successive day, he might assume the care of some new patients, but none on days six and seven. This means he takes on a disproportionately large number of new referrals at the beginning of his consecutive worked days, or “front-loads” new referrals. And because many of these patients will discharge before the end of his seven days and he takes on no new patients on days six and seven, his census will drop a lot before he rotates off, which in turn means there will be few patients who will have to get to know a new doctor on the first day Dr. Petty starts his seven-off schedule.

This system of patient distribution means continuity improved without requiring Dr. Petty to work more consecutive day shifts. Even though he works seven consecutive days and his average (or median) LOS is 4.2, as in the example above, his continuity will be much better than 54%. In fact, as many as 70% to 80% of Dr. Petty’s patients will see him for every daytime visit during their stay.

Other benefits of assigning more patients early and none late in a series of worked days are that on his last day of service, he will have more time to “tee up” patients for the next doctor, including preparing for patients anticipated to discharge the next day (e.g., dictate discharge summary, complete paperwork, etc.), and might be able to wrap up a little earlier that day. And when rotating back on service, he will pick up a small list of patients left by Dr. Tench, maybe fewer than eight, rather than the group’s average daily load of 15 patients per doctor, so he will have the capacity to admit a lot of patients that day.

I think there are three main reasons this isn’t a more common approach:

- Many HM groups just haven’t considered it.

- HM groups might have a schedule that has all doctors rotate off/on the same days each week. For example, all doctors rotate off on Tuesdays and are replaced by new doctors on Wednesday. That makes it impossible to exempt a doctor from taking on new referrals on the last day of service because all of the group’s doctors have their last day on Tuesday. These groups could stagger the day each doctor rotates off—one on Monday, one on Tuesday, and so on.

- Every doctor is so busy each day that it wouldn’t be feasible to exempt any individual doctor from taking on new patients, even if they are off the next day.

Despite the difficulties implementing a system of front-loading new referrals, I think most hospitalists would find that they like it. Because it reduces handoffs, it reduces, at least modestly, the group’s overall workload and probably benefits the group’s quality and patient satisfaction. TH

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988 and is co-founder and past president of SHM. He is a principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants, a national hospitalist practice management consulting firm (www.nelsonflores.com). He is also course co-director and faculty for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. This column represents his views and is not intended to reflect an official position of SHM.

Editor’s note: Third of a three-part series.

In the two monthly columns preceding this one, I’ve provided an overview of some ways hospitalist groups distribute new referrals among the providers. This month, I’ll review things that cause some groups to make exceptions to their typical method of distributing patients, and turn from how patients are distributed over 24 hours to thoughts about how they might be assigned over the course of consecutive days worked by a doctor.

Equitable Exceptions

There are a number of reasons groups decide to depart from their typical method of assigning patients. These include:

- “Bouncebacks”;

- One hospitalist is at the cap, others aren’t;

- Consult requested of a specific hospitalist;

- Hospitalists with unique skills (e.g., ICU expertise); and

- A patient “fires” the hospitalist.

There isn’t a standard “hospitalist way” of dealing with these issues, and each group will need to work out its own system. The most common of these issues is “bouncebacks.” Every group should try to have patients readmitted within three or four days of discharge go back to the discharging hospitalist. However, this proves difficult in many cases for several reasons, most commonly because the original discharging doctor might not be working when the patient returns.

The Alpha & Omega

Nearly every hospitalist practice makes some effort to maximize continuity between a single hospitalist and patient over the course of a hospital stay. But the effect of the method of patient assignment on continuity often is overlooked.

A reasonable way to think about or measure continuity is to estimate the portion of patients seen by the group that see the same hospitalist for each daytime visit over the course of their stay. (Assume that in most HM groups the same hospitalist can’t make both day and night visits over the course of the hospital stay. So, just for simplicity, I’ve intentionally left night visits, including an initial admission visit at night, out of the continuity calculation.) Plug the numbers for your practice into the formula (see Figure 1, right) and see what you get.

If a hospitalist always works seven consecutive day shifts (e.g., a seven-on/seven-off schedule) and the hospitalist’s patients have an average LOS of 4.2 days, then 54% of patients will see the same hospitalist for all daytime visits, and 46% will experience at least one handoff. (To keep things simple, I’m ignoring the effect on continuity of patients being admitted by an “admitter” or nocturnist who doesn’t see the patient subsequently.)

Changing the number of consecutive day shifts a hospitalist works has the most significant impact on continuity, but just how many consecutive days can one work routinely before fatigue and burnout—not too mention increased errors and decreased patient satisfaction—become a problem? (Many hospitalists make the mistake of trying to stuff what might be a reasonable annual workload into the smallest number of shifts possible with the goal of maximizing the number of days off. That means each worked day will be very busy, making it really hard to work many consecutive days. But you always have the option of titrating out that same annual workload over more days so that each day is less busy and it becomes easier to work more consecutive days.)

An often-overlooked way to improve continuity without having to work more consecutive day shifts is to have a hospitalist who is early in their series of worked days take on more new admissions and consults, and perhaps exempt that doctor from taking on new referrals for the last day or two he or she is on service. Eric Howell, MD, FHM, an SHM board member, calls this method “slam and dwindle.” This has been the approach I’ve experienced my whole career, and it is hard for me to imagine doing it any other way.

Here’s how it might work: Let’s say Dr. Petty always works seven consecutive day shifts, and on the first day he picks up a list of patients remaining from the doctor he’s replacing. To keep things simple, let’s assume he’s not in a large group, and during his first day of seven days on service he accepts and “keeps” all new referrals to the practice. On each successive day, he might assume the care of some new patients, but none on days six and seven. This means he takes on a disproportionately large number of new referrals at the beginning of his consecutive worked days, or “front-loads” new referrals. And because many of these patients will discharge before the end of his seven days and he takes on no new patients on days six and seven, his census will drop a lot before he rotates off, which in turn means there will be few patients who will have to get to know a new doctor on the first day Dr. Petty starts his seven-off schedule.

This system of patient distribution means continuity improved without requiring Dr. Petty to work more consecutive day shifts. Even though he works seven consecutive days and his average (or median) LOS is 4.2, as in the example above, his continuity will be much better than 54%. In fact, as many as 70% to 80% of Dr. Petty’s patients will see him for every daytime visit during their stay.

Other benefits of assigning more patients early and none late in a series of worked days are that on his last day of service, he will have more time to “tee up” patients for the next doctor, including preparing for patients anticipated to discharge the next day (e.g., dictate discharge summary, complete paperwork, etc.), and might be able to wrap up a little earlier that day. And when rotating back on service, he will pick up a small list of patients left by Dr. Tench, maybe fewer than eight, rather than the group’s average daily load of 15 patients per doctor, so he will have the capacity to admit a lot of patients that day.

I think there are three main reasons this isn’t a more common approach:

- Many HM groups just haven’t considered it.

- HM groups might have a schedule that has all doctors rotate off/on the same days each week. For example, all doctors rotate off on Tuesdays and are replaced by new doctors on Wednesday. That makes it impossible to exempt a doctor from taking on new referrals on the last day of service because all of the group’s doctors have their last day on Tuesday. These groups could stagger the day each doctor rotates off—one on Monday, one on Tuesday, and so on.

- Every doctor is so busy each day that it wouldn’t be feasible to exempt any individual doctor from taking on new patients, even if they are off the next day.

Despite the difficulties implementing a system of front-loading new referrals, I think most hospitalists would find that they like it. Because it reduces handoffs, it reduces, at least modestly, the group’s overall workload and probably benefits the group’s quality and patient satisfaction. TH

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988 and is co-founder and past president of SHM. He is a principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants, a national hospitalist practice management consulting firm (www.nelsonflores.com). He is also course co-director and faculty for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. This column represents his views and is not intended to reflect an official position of SHM.

Editor’s note: Third of a three-part series.

In the two monthly columns preceding this one, I’ve provided an overview of some ways hospitalist groups distribute new referrals among the providers. This month, I’ll review things that cause some groups to make exceptions to their typical method of distributing patients, and turn from how patients are distributed over 24 hours to thoughts about how they might be assigned over the course of consecutive days worked by a doctor.

Equitable Exceptions

There are a number of reasons groups decide to depart from their typical method of assigning patients. These include:

- “Bouncebacks”;

- One hospitalist is at the cap, others aren’t;

- Consult requested of a specific hospitalist;

- Hospitalists with unique skills (e.g., ICU expertise); and

- A patient “fires” the hospitalist.

There isn’t a standard “hospitalist way” of dealing with these issues, and each group will need to work out its own system. The most common of these issues is “bouncebacks.” Every group should try to have patients readmitted within three or four days of discharge go back to the discharging hospitalist. However, this proves difficult in many cases for several reasons, most commonly because the original discharging doctor might not be working when the patient returns.

The Alpha & Omega

Nearly every hospitalist practice makes some effort to maximize continuity between a single hospitalist and patient over the course of a hospital stay. But the effect of the method of patient assignment on continuity often is overlooked.

A reasonable way to think about or measure continuity is to estimate the portion of patients seen by the group that see the same hospitalist for each daytime visit over the course of their stay. (Assume that in most HM groups the same hospitalist can’t make both day and night visits over the course of the hospital stay. So, just for simplicity, I’ve intentionally left night visits, including an initial admission visit at night, out of the continuity calculation.) Plug the numbers for your practice into the formula (see Figure 1, right) and see what you get.

If a hospitalist always works seven consecutive day shifts (e.g., a seven-on/seven-off schedule) and the hospitalist’s patients have an average LOS of 4.2 days, then 54% of patients will see the same hospitalist for all daytime visits, and 46% will experience at least one handoff. (To keep things simple, I’m ignoring the effect on continuity of patients being admitted by an “admitter” or nocturnist who doesn’t see the patient subsequently.)

Changing the number of consecutive day shifts a hospitalist works has the most significant impact on continuity, but just how many consecutive days can one work routinely before fatigue and burnout—not too mention increased errors and decreased patient satisfaction—become a problem? (Many hospitalists make the mistake of trying to stuff what might be a reasonable annual workload into the smallest number of shifts possible with the goal of maximizing the number of days off. That means each worked day will be very busy, making it really hard to work many consecutive days. But you always have the option of titrating out that same annual workload over more days so that each day is less busy and it becomes easier to work more consecutive days.)

An often-overlooked way to improve continuity without having to work more consecutive day shifts is to have a hospitalist who is early in their series of worked days take on more new admissions and consults, and perhaps exempt that doctor from taking on new referrals for the last day or two he or she is on service. Eric Howell, MD, FHM, an SHM board member, calls this method “slam and dwindle.” This has been the approach I’ve experienced my whole career, and it is hard for me to imagine doing it any other way.

Here’s how it might work: Let’s say Dr. Petty always works seven consecutive day shifts, and on the first day he picks up a list of patients remaining from the doctor he’s replacing. To keep things simple, let’s assume he’s not in a large group, and during his first day of seven days on service he accepts and “keeps” all new referrals to the practice. On each successive day, he might assume the care of some new patients, but none on days six and seven. This means he takes on a disproportionately large number of new referrals at the beginning of his consecutive worked days, or “front-loads” new referrals. And because many of these patients will discharge before the end of his seven days and he takes on no new patients on days six and seven, his census will drop a lot before he rotates off, which in turn means there will be few patients who will have to get to know a new doctor on the first day Dr. Petty starts his seven-off schedule.

This system of patient distribution means continuity improved without requiring Dr. Petty to work more consecutive day shifts. Even though he works seven consecutive days and his average (or median) LOS is 4.2, as in the example above, his continuity will be much better than 54%. In fact, as many as 70% to 80% of Dr. Petty’s patients will see him for every daytime visit during their stay.

Other benefits of assigning more patients early and none late in a series of worked days are that on his last day of service, he will have more time to “tee up” patients for the next doctor, including preparing for patients anticipated to discharge the next day (e.g., dictate discharge summary, complete paperwork, etc.), and might be able to wrap up a little earlier that day. And when rotating back on service, he will pick up a small list of patients left by Dr. Tench, maybe fewer than eight, rather than the group’s average daily load of 15 patients per doctor, so he will have the capacity to admit a lot of patients that day.

I think there are three main reasons this isn’t a more common approach:

- Many HM groups just haven’t considered it.

- HM groups might have a schedule that has all doctors rotate off/on the same days each week. For example, all doctors rotate off on Tuesdays and are replaced by new doctors on Wednesday. That makes it impossible to exempt a doctor from taking on new referrals on the last day of service because all of the group’s doctors have their last day on Tuesday. These groups could stagger the day each doctor rotates off—one on Monday, one on Tuesday, and so on.

- Every doctor is so busy each day that it wouldn’t be feasible to exempt any individual doctor from taking on new patients, even if they are off the next day.

Despite the difficulties implementing a system of front-loading new referrals, I think most hospitalists would find that they like it. Because it reduces handoffs, it reduces, at least modestly, the group’s overall workload and probably benefits the group’s quality and patient satisfaction. TH

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988 and is co-founder and past president of SHM. He is a principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants, a national hospitalist practice management consulting firm (www.nelsonflores.com). He is also course co-director and faculty for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. This column represents his views and is not intended to reflect an official position of SHM.

New Referral Distribution

Editor’s note: Second of a three-part series.

As I mentioned last month, there isn’t a proven best method to use when distributing new referrals among your group’s providers. The popular methods fall along a continuum of being focused on daily, or continuous, leveling of patient loads between providers (“load leveling”) at one end; at the other end of the continuum is having a doctor be “on” for all new referrals for a predetermined time period, and accepting that patient volumes might be uneven day to day but tend to even out over long periods.

There might not be any reason to change your group’s approach to patient assignment, but you should always be thinking about how your own methods might be changed or improved. I have shared (“Bigger Isn’t Always Better,” June 2009, p. 46) my concern that some groups invest far too much time in a morning load-leveling and handoff conference. Make sure your group is using only as much time as needed.

Air-Traffic Controllers

Many large groups (e.g., more than 15 full-time equivalents) that assign patients to providers in sequence, like dealing a deck of cards, have a designated provider who holds the triage pager and serves as “air-traffic controller.” This person typically takes incoming calls about all new referrals, jots down the relevant clinical data, keeps track of which hospitalist is due to take the next patient, pages that person, and repeats the clinical information. As I’ve written before (“How to Hire and Use Clerical Staff,” June 2007, p. 73), many practices have found that during business hours, they can hand this role to a clerical person who simply takes down the name and phone number of the doctor making the referral, then pages that information to the hospitalist due to get the next patient. The hospitalist then calls and speaks directly with the referring doctor.

Small- to medium-sized groups can eliminate entirely the need for any such “air-traffic control” function if they assign all new referrals to a single doctor for specified periods of time. For example, from 7 a.m. to 3 p.m. today, all new referrals go to Dr. Glass, and from 3 p.m. to 11 p.m., they go to Dr. Cage.

Admitter-Rounder Duties

Many—maybe most?—large groups separate daytime admitter and rounder functions so that on any given day, a hospitalist does one but not both. The principal advantages of this approach are reducing the stress on, and possibly increasing the efficiency of, rounding doctors by shielding them from the unpredictable and time-consuming interruption of needing to admit a new patient. And a daytime doctor who only does admissions might be able to start seeing a patient in the ED more quickly than one who is busy making rounds.

Any increased availability of admitters to the ED could be offset by their lack of surge capacity leading to a bottleneck in ED throughput when there are many patients to admit at the same time and a limited number of admitters (often only one). Such a bottleneck would be much less likely if all daytime doctors (i.e., the rounders) were available to see admissions rather than just admitters.

Continuity of care suffers when a group has separate admitters and rounders, because no patients will be seen by the same doctor on the day of admission and the day following. This method requires a handoff from the day of admission to the next day. Such a handoff might be unavoidable for patients admitted during the night, but this doesn’t have to occur when patients are admitted during the daytime.

Who’s Seeing this Patient?

It seems to make sense to wait until each morning to distribute patients. That allows the practice to know just how many new patients there are, and they can be distributed according to complexity and whether a hospitalist has formed a previous relationship with that patient. But it means that no one at the hospital will know which hospitalist is caring for the patient until later in the morning. For example, if the radiologist is over-reading a study done during the night and finds something worthy of a phone call to the hospitalist, no one is sure who should get the call. A patient might develop hypoglycemia shortly after the hospitalist night shift is over, but the nurse doesn’t know which hospitalist to call.

And, perhaps most importantly, if patients aren’t distributed until the start of the day shift, the night hospitalist can’t tell the patient and family which hospitalist to expect the next morning. To test the significance of this issue, I conducted an experiment while working our group’s late-evening admitter shift. I concluded my visit with each admitted patient by explaining, “I am on-call for our group tonight, so I will be off recovering tomorrow. Therefore, I won’t see you again, but one of my partners will take over in the morning. Do you have any questions for me?” Every patient I admitted had the same question. “What is that doctor’s name?”

How does your group answer a patient who asks which hospitalist will be in the next day? If your method is load-leveling in the morning, then the best answer your night admitting doctor can give is probably to say: “I don’t know which of my partners will be in. There are several working tomorrow, and at the start of the day, they will divide up the patients who come in tonight depending on how busy each of them is. But all the doctors in our group are terrific and will take good care of you.”

I’m told the same thing when I get my hair cut: You’ll get whichever “hair artist” is up next. I put up with it at the hair place because it costs less than $15. But I still find it a little irritating. I’m sure all the barbers aren’t equally skilled or diligent, and I want the best one. (Maybe I shouldn’t care since there isn’t much that can be done with my hair.) I’m pretty sure patients feel the same way about which doctor they get. The public is convinced there is a wide variety in the quality of doctors, and they want a good one. If you have to tell them theirs is being assigned by lottery, they won’t be as happy than if you can provide the name and a little information about the doctor they can expect to see the next day.

When the patients I admit late last evening ask who would see them the next day, I’m glad when I can provide a name and a little more information. I say something like, “I won’t see you after tonight, but my partner, Dr. Shawn Lee, will be instead. That means you’re getting an upgrade! Not only is he a really nice guy, he’s voted one of Seattle’s best doctors every year. He’ll do a great job for you.”

To make this communication effective, the night doctor has to know which hospitalist takes over the next morning and has a list indicating which day doctor will get the first, second, third new patient, and so on, admitted during the night. This is possible if patients are assigned by a predetermined algorithm, or if the day doctors have their load-leveling meeting at the end of each day shift, rather than in the morning, to create a list telling the night doctor which day hospitalist he should admit the first and subsequent patents to. That way, the night doctor can write in the admitting orders at 1 a.m. “admit to Dr. X.” This eliminates confusion on the part of other hospital staff who need to know who to call about a patient after the start of the day shift.

Next month I will look at special circumstances, and some pros and cons of having an individual hospitalist take on the care of more patients at the beginning of consecutive day shifts, and exempting them from taking on new patients on the last day or two before rotating off. TH

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988 and is co-founder and past president of SHM. He is a principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants, a national hospitalist practice management consulting firm (www.nelsonflores.com). He is also course co-director and faculty for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. This column represents his views and is not intended to reflect an official position of SHM.

Editor’s note: Second of a three-part series.

As I mentioned last month, there isn’t a proven best method to use when distributing new referrals among your group’s providers. The popular methods fall along a continuum of being focused on daily, or continuous, leveling of patient loads between providers (“load leveling”) at one end; at the other end of the continuum is having a doctor be “on” for all new referrals for a predetermined time period, and accepting that patient volumes might be uneven day to day but tend to even out over long periods.

There might not be any reason to change your group’s approach to patient assignment, but you should always be thinking about how your own methods might be changed or improved. I have shared (“Bigger Isn’t Always Better,” June 2009, p. 46) my concern that some groups invest far too much time in a morning load-leveling and handoff conference. Make sure your group is using only as much time as needed.

Air-Traffic Controllers

Many large groups (e.g., more than 15 full-time equivalents) that assign patients to providers in sequence, like dealing a deck of cards, have a designated provider who holds the triage pager and serves as “air-traffic controller.” This person typically takes incoming calls about all new referrals, jots down the relevant clinical data, keeps track of which hospitalist is due to take the next patient, pages that person, and repeats the clinical information. As I’ve written before (“How to Hire and Use Clerical Staff,” June 2007, p. 73), many practices have found that during business hours, they can hand this role to a clerical person who simply takes down the name and phone number of the doctor making the referral, then pages that information to the hospitalist due to get the next patient. The hospitalist then calls and speaks directly with the referring doctor.

Small- to medium-sized groups can eliminate entirely the need for any such “air-traffic control” function if they assign all new referrals to a single doctor for specified periods of time. For example, from 7 a.m. to 3 p.m. today, all new referrals go to Dr. Glass, and from 3 p.m. to 11 p.m., they go to Dr. Cage.

Admitter-Rounder Duties

Many—maybe most?—large groups separate daytime admitter and rounder functions so that on any given day, a hospitalist does one but not both. The principal advantages of this approach are reducing the stress on, and possibly increasing the efficiency of, rounding doctors by shielding them from the unpredictable and time-consuming interruption of needing to admit a new patient. And a daytime doctor who only does admissions might be able to start seeing a patient in the ED more quickly than one who is busy making rounds.

Any increased availability of admitters to the ED could be offset by their lack of surge capacity leading to a bottleneck in ED throughput when there are many patients to admit at the same time and a limited number of admitters (often only one). Such a bottleneck would be much less likely if all daytime doctors (i.e., the rounders) were available to see admissions rather than just admitters.

Continuity of care suffers when a group has separate admitters and rounders, because no patients will be seen by the same doctor on the day of admission and the day following. This method requires a handoff from the day of admission to the next day. Such a handoff might be unavoidable for patients admitted during the night, but this doesn’t have to occur when patients are admitted during the daytime.

Who’s Seeing this Patient?

It seems to make sense to wait until each morning to distribute patients. That allows the practice to know just how many new patients there are, and they can be distributed according to complexity and whether a hospitalist has formed a previous relationship with that patient. But it means that no one at the hospital will know which hospitalist is caring for the patient until later in the morning. For example, if the radiologist is over-reading a study done during the night and finds something worthy of a phone call to the hospitalist, no one is sure who should get the call. A patient might develop hypoglycemia shortly after the hospitalist night shift is over, but the nurse doesn’t know which hospitalist to call.

And, perhaps most importantly, if patients aren’t distributed until the start of the day shift, the night hospitalist can’t tell the patient and family which hospitalist to expect the next morning. To test the significance of this issue, I conducted an experiment while working our group’s late-evening admitter shift. I concluded my visit with each admitted patient by explaining, “I am on-call for our group tonight, so I will be off recovering tomorrow. Therefore, I won’t see you again, but one of my partners will take over in the morning. Do you have any questions for me?” Every patient I admitted had the same question. “What is that doctor’s name?”

How does your group answer a patient who asks which hospitalist will be in the next day? If your method is load-leveling in the morning, then the best answer your night admitting doctor can give is probably to say: “I don’t know which of my partners will be in. There are several working tomorrow, and at the start of the day, they will divide up the patients who come in tonight depending on how busy each of them is. But all the doctors in our group are terrific and will take good care of you.”

I’m told the same thing when I get my hair cut: You’ll get whichever “hair artist” is up next. I put up with it at the hair place because it costs less than $15. But I still find it a little irritating. I’m sure all the barbers aren’t equally skilled or diligent, and I want the best one. (Maybe I shouldn’t care since there isn’t much that can be done with my hair.) I’m pretty sure patients feel the same way about which doctor they get. The public is convinced there is a wide variety in the quality of doctors, and they want a good one. If you have to tell them theirs is being assigned by lottery, they won’t be as happy than if you can provide the name and a little information about the doctor they can expect to see the next day.

When the patients I admit late last evening ask who would see them the next day, I’m glad when I can provide a name and a little more information. I say something like, “I won’t see you after tonight, but my partner, Dr. Shawn Lee, will be instead. That means you’re getting an upgrade! Not only is he a really nice guy, he’s voted one of Seattle’s best doctors every year. He’ll do a great job for you.”

To make this communication effective, the night doctor has to know which hospitalist takes over the next morning and has a list indicating which day doctor will get the first, second, third new patient, and so on, admitted during the night. This is possible if patients are assigned by a predetermined algorithm, or if the day doctors have their load-leveling meeting at the end of each day shift, rather than in the morning, to create a list telling the night doctor which day hospitalist he should admit the first and subsequent patents to. That way, the night doctor can write in the admitting orders at 1 a.m. “admit to Dr. X.” This eliminates confusion on the part of other hospital staff who need to know who to call about a patient after the start of the day shift.

Next month I will look at special circumstances, and some pros and cons of having an individual hospitalist take on the care of more patients at the beginning of consecutive day shifts, and exempting them from taking on new patients on the last day or two before rotating off. TH

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988 and is co-founder and past president of SHM. He is a principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants, a national hospitalist practice management consulting firm (www.nelsonflores.com). He is also course co-director and faculty for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. This column represents his views and is not intended to reflect an official position of SHM.

Editor’s note: Second of a three-part series.

As I mentioned last month, there isn’t a proven best method to use when distributing new referrals among your group’s providers. The popular methods fall along a continuum of being focused on daily, or continuous, leveling of patient loads between providers (“load leveling”) at one end; at the other end of the continuum is having a doctor be “on” for all new referrals for a predetermined time period, and accepting that patient volumes might be uneven day to day but tend to even out over long periods.

There might not be any reason to change your group’s approach to patient assignment, but you should always be thinking about how your own methods might be changed or improved. I have shared (“Bigger Isn’t Always Better,” June 2009, p. 46) my concern that some groups invest far too much time in a morning load-leveling and handoff conference. Make sure your group is using only as much time as needed.

Air-Traffic Controllers

Many large groups (e.g., more than 15 full-time equivalents) that assign patients to providers in sequence, like dealing a deck of cards, have a designated provider who holds the triage pager and serves as “air-traffic controller.” This person typically takes incoming calls about all new referrals, jots down the relevant clinical data, keeps track of which hospitalist is due to take the next patient, pages that person, and repeats the clinical information. As I’ve written before (“How to Hire and Use Clerical Staff,” June 2007, p. 73), many practices have found that during business hours, they can hand this role to a clerical person who simply takes down the name and phone number of the doctor making the referral, then pages that information to the hospitalist due to get the next patient. The hospitalist then calls and speaks directly with the referring doctor.

Small- to medium-sized groups can eliminate entirely the need for any such “air-traffic control” function if they assign all new referrals to a single doctor for specified periods of time. For example, from 7 a.m. to 3 p.m. today, all new referrals go to Dr. Glass, and from 3 p.m. to 11 p.m., they go to Dr. Cage.

Admitter-Rounder Duties

Many—maybe most?—large groups separate daytime admitter and rounder functions so that on any given day, a hospitalist does one but not both. The principal advantages of this approach are reducing the stress on, and possibly increasing the efficiency of, rounding doctors by shielding them from the unpredictable and time-consuming interruption of needing to admit a new patient. And a daytime doctor who only does admissions might be able to start seeing a patient in the ED more quickly than one who is busy making rounds.

Any increased availability of admitters to the ED could be offset by their lack of surge capacity leading to a bottleneck in ED throughput when there are many patients to admit at the same time and a limited number of admitters (often only one). Such a bottleneck would be much less likely if all daytime doctors (i.e., the rounders) were available to see admissions rather than just admitters.

Continuity of care suffers when a group has separate admitters and rounders, because no patients will be seen by the same doctor on the day of admission and the day following. This method requires a handoff from the day of admission to the next day. Such a handoff might be unavoidable for patients admitted during the night, but this doesn’t have to occur when patients are admitted during the daytime.

Who’s Seeing this Patient?

It seems to make sense to wait until each morning to distribute patients. That allows the practice to know just how many new patients there are, and they can be distributed according to complexity and whether a hospitalist has formed a previous relationship with that patient. But it means that no one at the hospital will know which hospitalist is caring for the patient until later in the morning. For example, if the radiologist is over-reading a study done during the night and finds something worthy of a phone call to the hospitalist, no one is sure who should get the call. A patient might develop hypoglycemia shortly after the hospitalist night shift is over, but the nurse doesn’t know which hospitalist to call.

And, perhaps most importantly, if patients aren’t distributed until the start of the day shift, the night hospitalist can’t tell the patient and family which hospitalist to expect the next morning. To test the significance of this issue, I conducted an experiment while working our group’s late-evening admitter shift. I concluded my visit with each admitted patient by explaining, “I am on-call for our group tonight, so I will be off recovering tomorrow. Therefore, I won’t see you again, but one of my partners will take over in the morning. Do you have any questions for me?” Every patient I admitted had the same question. “What is that doctor’s name?”

How does your group answer a patient who asks which hospitalist will be in the next day? If your method is load-leveling in the morning, then the best answer your night admitting doctor can give is probably to say: “I don’t know which of my partners will be in. There are several working tomorrow, and at the start of the day, they will divide up the patients who come in tonight depending on how busy each of them is. But all the doctors in our group are terrific and will take good care of you.”

I’m told the same thing when I get my hair cut: You’ll get whichever “hair artist” is up next. I put up with it at the hair place because it costs less than $15. But I still find it a little irritating. I’m sure all the barbers aren’t equally skilled or diligent, and I want the best one. (Maybe I shouldn’t care since there isn’t much that can be done with my hair.) I’m pretty sure patients feel the same way about which doctor they get. The public is convinced there is a wide variety in the quality of doctors, and they want a good one. If you have to tell them theirs is being assigned by lottery, they won’t be as happy than if you can provide the name and a little information about the doctor they can expect to see the next day.

When the patients I admit late last evening ask who would see them the next day, I’m glad when I can provide a name and a little more information. I say something like, “I won’t see you after tonight, but my partner, Dr. Shawn Lee, will be instead. That means you’re getting an upgrade! Not only is he a really nice guy, he’s voted one of Seattle’s best doctors every year. He’ll do a great job for you.”

To make this communication effective, the night doctor has to know which hospitalist takes over the next morning and has a list indicating which day doctor will get the first, second, third new patient, and so on, admitted during the night. This is possible if patients are assigned by a predetermined algorithm, or if the day doctors have their load-leveling meeting at the end of each day shift, rather than in the morning, to create a list telling the night doctor which day hospitalist he should admit the first and subsequent patents to. That way, the night doctor can write in the admitting orders at 1 a.m. “admit to Dr. X.” This eliminates confusion on the part of other hospital staff who need to know who to call about a patient after the start of the day shift.

Next month I will look at special circumstances, and some pros and cons of having an individual hospitalist take on the care of more patients at the beginning of consecutive day shifts, and exempting them from taking on new patients on the last day or two before rotating off. TH

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988 and is co-founder and past president of SHM. He is a principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants, a national hospitalist practice management consulting firm (www.nelsonflores.com). He is also course co-director and faculty for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. This column represents his views and is not intended to reflect an official position of SHM.

Patient Distribution

Editor’s note: This is the first of a three-part series.

My experience is that some, maybe even most, hospitalists tend to assume there is a standard or “right” way to organize things like work schedules, compensation, or even the assignment of patients among the group’s providers. Some will say things like “SHM says the best hospitalist schedule is …” or “The best way to compensate hospitalists is …”

But there really isn’t a “best” way to manage any particular attribute of a practice. Don’t make the mistake of assuming your method is best, or that it’s the way “everybody else does it.” Although scheduling and compensation are marquee issues for hospitalists, approaches to distributing new patients is much less visible. Many groups tend to assume their method is the only reasonable approach. The best approach, however, varies from one practice to the next. You should be open to hearing approaches to scheduling that are different from your own.

Assign Patients by “Load Leveling”

I’ve come across a lot—and I mean a lot—of different approaches to distributing new patients in HM groups around the country, but it seems pretty clear that the most common method is to undertake “load leveling” on a daily or ongoing basis.

For example, groups that have a separate night shift (the night doctor performs no daytime work the day before or the day after a night shift) typically distribute the night’s new patients with the intent of having each daytime doctor start with the same number of patients. The group might more heavily weight some patients, such as those in the ICU (e.g., each ICU patient counts as 1.5 or two non-ICU patients), but most groups don’t. Over the course of the day shift, new referrals will be distributed evenly among the doctors one at a time, sort of like dealing a deck of cards.

This approach aims to avoid significant imbalances in patient loads and has the potential cultural benefit of everyone sharing equally in busy and slow days. Groups that use it tend to see it as the best option because it is the fairest way to divide up the workload.

Practices that use load-leveling almost always use a schedule built on shifts of a predetermined and fixed duration. For example, say the day shift always works from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. This schedule usually has the majority of compensation paid via a fixed annual salary or fixed shift rate. One potential problem with this approach is that the doctor who is efficient and discharges a lot of patients today is “rewarded” with more new patients tomorrow. Hospitalists who are allergic to work might have an incentive to have a patient wait until tomorrow to discharge to avoid having to assume the care of yet another patient tomorrow morning. Hospital executives who are focused on length-of-stay management might be concerned if they knew this was a potential issue. Of course, the reverse is true as well. In a practice that doesn’t aggressively undertake load-leveling, a less-than-admirable hospitalist could push patients to discharge earlier than optimal just to have one less patient the next day.

Another cost of this approach is that the distribution of patients can be time-consuming each morning. It also offers the opportunity for some in the group to decide they’re treated unfairly. For instance, you might hear the occasional “just last Tuesday, I started with 16 patients, compared with 15 for everyone else. Now you want me to do it again? You’re being unfair to me; it’s someone else’s turn to take the extra patient.”

Assignment by Location

Groups that use “unit-based” hospitalists distribute patients according to the unit the patient is admitted to—and the hospitalist covering that unit. The pros and cons of unit-based hospitalists are many (see “A Unit-Based Approach,” September 2007), but there is an obvious tension between keeping patient loads even among hospitalists and ensuring that all of a hospitalist’s patients are on “their” unit. Practicality usually requires a compromise between pure unit-based assignment and load-leveling.

Uneven Assignments

Some groups assign patients according to a predetermined algorithm and employ load-leveling only when patient loads become extremely unbalanced. For example, Dr. Jones gets all the new referrals today, and Dr. James gets them tomorrow. The idea is that patient loads end up close to even over time, even if they’re unbalanced on any given day.

A system like this allows everyone, including the hospitalists themselves, ED staff, etc., to know who will take the next patient. It decreases the need to communicate the “who’s next” information time after time during the course of the day. In small- to medium-sized practices, it could mean no one needs to function as the triage doctor (i.e., the person who inefficiently answers the service calls, scribbles down clinical information, then calls the hospitalist who is due to take the next patient and relays all the pertinent patient info). This system allows the

hospitalists to know which days will be harder (e.g., taking on the care of new patients) and which days will be easier (e.g., rounding but not assuming care of new patients). Allowing uneven loads also eliminates the need to spend energy working to even the loads and risking that some in the group feel as if they aren’t being treated fairly.

Uncommon yet Intriguing Approaches

Pair referring primary-care physicians (PCPs) with specific hospitalists. I’ve encountered two groups that had hospitalists always admit patients from the same PCPs. In other words, hospitalist Dr. Hancock always serves as attending for patients referred by the same nine PCPs, and hospitalist Dr. Franklin always attends to patients from a different set of PCPs. It seems to me that there could be tremendous benefit in working closely with the same PCPs, most notably getting to know the PCPs’ office staff. But this system raises the risk of creating out-of-balance patient loads, among other problems. It is really attractive to me, but most groups will decide its costs outweigh its benefits.

Hospitalist and patient stay connected during admission. I’m not aware of any group that uses this method (let me know if you do!), but there could be benefits to having each patient see the same hospitalist during each hospital stay. Of course, that is assuming the hospitalist is on duty. Hospitalist and patient could be paired upon the patient’s first admission. The hospitalist could form an excellent relationship with the patient and family; the time spent by the hospitalist getting to know patients on admission would be reduced, and I suspect there might be some benefit in the quality of care.

This method, however, likely results in the most uneven patient loads, and load-leveling would be difficult, if not impossible. Even if hospitalist and patient did form a tight bond, there is a high probability that the hospitalist would be off for the duration of the patient’s next admission. So despite what I suspect are tremendous benefits, this approach may not be feasible for any group.

In next month’s column, I will discuss issues related to the way patients are distributed. TH

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988 and is co-founder and past president of SHM. He is a principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants, a national hospitalist practice management consulting firm (www.nelsonflores.com). He is co-director and faculty for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. This column represents his views and is not intended to reflect an official position of SHM.

Editor’s note: This is the first of a three-part series.

My experience is that some, maybe even most, hospitalists tend to assume there is a standard or “right” way to organize things like work schedules, compensation, or even the assignment of patients among the group’s providers. Some will say things like “SHM says the best hospitalist schedule is …” or “The best way to compensate hospitalists is …”

But there really isn’t a “best” way to manage any particular attribute of a practice. Don’t make the mistake of assuming your method is best, or that it’s the way “everybody else does it.” Although scheduling and compensation are marquee issues for hospitalists, approaches to distributing new patients is much less visible. Many groups tend to assume their method is the only reasonable approach. The best approach, however, varies from one practice to the next. You should be open to hearing approaches to scheduling that are different from your own.

Assign Patients by “Load Leveling”

I’ve come across a lot—and I mean a lot—of different approaches to distributing new patients in HM groups around the country, but it seems pretty clear that the most common method is to undertake “load leveling” on a daily or ongoing basis.

For example, groups that have a separate night shift (the night doctor performs no daytime work the day before or the day after a night shift) typically distribute the night’s new patients with the intent of having each daytime doctor start with the same number of patients. The group might more heavily weight some patients, such as those in the ICU (e.g., each ICU patient counts as 1.5 or two non-ICU patients), but most groups don’t. Over the course of the day shift, new referrals will be distributed evenly among the doctors one at a time, sort of like dealing a deck of cards.

This approach aims to avoid significant imbalances in patient loads and has the potential cultural benefit of everyone sharing equally in busy and slow days. Groups that use it tend to see it as the best option because it is the fairest way to divide up the workload.

Practices that use load-leveling almost always use a schedule built on shifts of a predetermined and fixed duration. For example, say the day shift always works from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. This schedule usually has the majority of compensation paid via a fixed annual salary or fixed shift rate. One potential problem with this approach is that the doctor who is efficient and discharges a lot of patients today is “rewarded” with more new patients tomorrow. Hospitalists who are allergic to work might have an incentive to have a patient wait until tomorrow to discharge to avoid having to assume the care of yet another patient tomorrow morning. Hospital executives who are focused on length-of-stay management might be concerned if they knew this was a potential issue. Of course, the reverse is true as well. In a practice that doesn’t aggressively undertake load-leveling, a less-than-admirable hospitalist could push patients to discharge earlier than optimal just to have one less patient the next day.

Another cost of this approach is that the distribution of patients can be time-consuming each morning. It also offers the opportunity for some in the group to decide they’re treated unfairly. For instance, you might hear the occasional “just last Tuesday, I started with 16 patients, compared with 15 for everyone else. Now you want me to do it again? You’re being unfair to me; it’s someone else’s turn to take the extra patient.”

Assignment by Location

Groups that use “unit-based” hospitalists distribute patients according to the unit the patient is admitted to—and the hospitalist covering that unit. The pros and cons of unit-based hospitalists are many (see “A Unit-Based Approach,” September 2007), but there is an obvious tension between keeping patient loads even among hospitalists and ensuring that all of a hospitalist’s patients are on “their” unit. Practicality usually requires a compromise between pure unit-based assignment and load-leveling.

Uneven Assignments

Some groups assign patients according to a predetermined algorithm and employ load-leveling only when patient loads become extremely unbalanced. For example, Dr. Jones gets all the new referrals today, and Dr. James gets them tomorrow. The idea is that patient loads end up close to even over time, even if they’re unbalanced on any given day.

A system like this allows everyone, including the hospitalists themselves, ED staff, etc., to know who will take the next patient. It decreases the need to communicate the “who’s next” information time after time during the course of the day. In small- to medium-sized practices, it could mean no one needs to function as the triage doctor (i.e., the person who inefficiently answers the service calls, scribbles down clinical information, then calls the hospitalist who is due to take the next patient and relays all the pertinent patient info). This system allows the

hospitalists to know which days will be harder (e.g., taking on the care of new patients) and which days will be easier (e.g., rounding but not assuming care of new patients). Allowing uneven loads also eliminates the need to spend energy working to even the loads and risking that some in the group feel as if they aren’t being treated fairly.

Uncommon yet Intriguing Approaches

Pair referring primary-care physicians (PCPs) with specific hospitalists. I’ve encountered two groups that had hospitalists always admit patients from the same PCPs. In other words, hospitalist Dr. Hancock always serves as attending for patients referred by the same nine PCPs, and hospitalist Dr. Franklin always attends to patients from a different set of PCPs. It seems to me that there could be tremendous benefit in working closely with the same PCPs, most notably getting to know the PCPs’ office staff. But this system raises the risk of creating out-of-balance patient loads, among other problems. It is really attractive to me, but most groups will decide its costs outweigh its benefits.

Hospitalist and patient stay connected during admission. I’m not aware of any group that uses this method (let me know if you do!), but there could be benefits to having each patient see the same hospitalist during each hospital stay. Of course, that is assuming the hospitalist is on duty. Hospitalist and patient could be paired upon the patient’s first admission. The hospitalist could form an excellent relationship with the patient and family; the time spent by the hospitalist getting to know patients on admission would be reduced, and I suspect there might be some benefit in the quality of care.

This method, however, likely results in the most uneven patient loads, and load-leveling would be difficult, if not impossible. Even if hospitalist and patient did form a tight bond, there is a high probability that the hospitalist would be off for the duration of the patient’s next admission. So despite what I suspect are tremendous benefits, this approach may not be feasible for any group.

In next month’s column, I will discuss issues related to the way patients are distributed. TH

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988 and is co-founder and past president of SHM. He is a principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants, a national hospitalist practice management consulting firm (www.nelsonflores.com). He is co-director and faculty for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. This column represents his views and is not intended to reflect an official position of SHM.

Editor’s note: This is the first of a three-part series.

My experience is that some, maybe even most, hospitalists tend to assume there is a standard or “right” way to organize things like work schedules, compensation, or even the assignment of patients among the group’s providers. Some will say things like “SHM says the best hospitalist schedule is …” or “The best way to compensate hospitalists is …”

But there really isn’t a “best” way to manage any particular attribute of a practice. Don’t make the mistake of assuming your method is best, or that it’s the way “everybody else does it.” Although scheduling and compensation are marquee issues for hospitalists, approaches to distributing new patients is much less visible. Many groups tend to assume their method is the only reasonable approach. The best approach, however, varies from one practice to the next. You should be open to hearing approaches to scheduling that are different from your own.

Assign Patients by “Load Leveling”

I’ve come across a lot—and I mean a lot—of different approaches to distributing new patients in HM groups around the country, but it seems pretty clear that the most common method is to undertake “load leveling” on a daily or ongoing basis.

For example, groups that have a separate night shift (the night doctor performs no daytime work the day before or the day after a night shift) typically distribute the night’s new patients with the intent of having each daytime doctor start with the same number of patients. The group might more heavily weight some patients, such as those in the ICU (e.g., each ICU patient counts as 1.5 or two non-ICU patients), but most groups don’t. Over the course of the day shift, new referrals will be distributed evenly among the doctors one at a time, sort of like dealing a deck of cards.

This approach aims to avoid significant imbalances in patient loads and has the potential cultural benefit of everyone sharing equally in busy and slow days. Groups that use it tend to see it as the best option because it is the fairest way to divide up the workload.

Practices that use load-leveling almost always use a schedule built on shifts of a predetermined and fixed duration. For example, say the day shift always works from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. This schedule usually has the majority of compensation paid via a fixed annual salary or fixed shift rate. One potential problem with this approach is that the doctor who is efficient and discharges a lot of patients today is “rewarded” with more new patients tomorrow. Hospitalists who are allergic to work might have an incentive to have a patient wait until tomorrow to discharge to avoid having to assume the care of yet another patient tomorrow morning. Hospital executives who are focused on length-of-stay management might be concerned if they knew this was a potential issue. Of course, the reverse is true as well. In a practice that doesn’t aggressively undertake load-leveling, a less-than-admirable hospitalist could push patients to discharge earlier than optimal just to have one less patient the next day.

Another cost of this approach is that the distribution of patients can be time-consuming each morning. It also offers the opportunity for some in the group to decide they’re treated unfairly. For instance, you might hear the occasional “just last Tuesday, I started with 16 patients, compared with 15 for everyone else. Now you want me to do it again? You’re being unfair to me; it’s someone else’s turn to take the extra patient.”

Assignment by Location

Groups that use “unit-based” hospitalists distribute patients according to the unit the patient is admitted to—and the hospitalist covering that unit. The pros and cons of unit-based hospitalists are many (see “A Unit-Based Approach,” September 2007), but there is an obvious tension between keeping patient loads even among hospitalists and ensuring that all of a hospitalist’s patients are on “their” unit. Practicality usually requires a compromise between pure unit-based assignment and load-leveling.

Uneven Assignments

Some groups assign patients according to a predetermined algorithm and employ load-leveling only when patient loads become extremely unbalanced. For example, Dr. Jones gets all the new referrals today, and Dr. James gets them tomorrow. The idea is that patient loads end up close to even over time, even if they’re unbalanced on any given day.

A system like this allows everyone, including the hospitalists themselves, ED staff, etc., to know who will take the next patient. It decreases the need to communicate the “who’s next” information time after time during the course of the day. In small- to medium-sized practices, it could mean no one needs to function as the triage doctor (i.e., the person who inefficiently answers the service calls, scribbles down clinical information, then calls the hospitalist who is due to take the next patient and relays all the pertinent patient info). This system allows the

hospitalists to know which days will be harder (e.g., taking on the care of new patients) and which days will be easier (e.g., rounding but not assuming care of new patients). Allowing uneven loads also eliminates the need to spend energy working to even the loads and risking that some in the group feel as if they aren’t being treated fairly.

Uncommon yet Intriguing Approaches

Pair referring primary-care physicians (PCPs) with specific hospitalists. I’ve encountered two groups that had hospitalists always admit patients from the same PCPs. In other words, hospitalist Dr. Hancock always serves as attending for patients referred by the same nine PCPs, and hospitalist Dr. Franklin always attends to patients from a different set of PCPs. It seems to me that there could be tremendous benefit in working closely with the same PCPs, most notably getting to know the PCPs’ office staff. But this system raises the risk of creating out-of-balance patient loads, among other problems. It is really attractive to me, but most groups will decide its costs outweigh its benefits.

Hospitalist and patient stay connected during admission. I’m not aware of any group that uses this method (let me know if you do!), but there could be benefits to having each patient see the same hospitalist during each hospital stay. Of course, that is assuming the hospitalist is on duty. Hospitalist and patient could be paired upon the patient’s first admission. The hospitalist could form an excellent relationship with the patient and family; the time spent by the hospitalist getting to know patients on admission would be reduced, and I suspect there might be some benefit in the quality of care.

This method, however, likely results in the most uneven patient loads, and load-leveling would be difficult, if not impossible. Even if hospitalist and patient did form a tight bond, there is a high probability that the hospitalist would be off for the duration of the patient’s next admission. So despite what I suspect are tremendous benefits, this approach may not be feasible for any group.

In next month’s column, I will discuss issues related to the way patients are distributed. TH

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988 and is co-founder and past president of SHM. He is a principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants, a national hospitalist practice management consulting firm (www.nelsonflores.com). He is co-director and faculty for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. This column represents his views and is not intended to reflect an official position of SHM.

Necessary Evil: Change

The amount and complexity of medical knowledge we need to keep up with is changing and growing at a remarkable rate. I was trained in an era in which it was taken as a given that congestive heart failure patients should not receive beta-blockers; now it is a big mistake if we don’t prescribe them in most cases. But even before starting medical school, most of us realize that things will change a lot, and many of us see that as a good thing. It keeps our work interesting. Just recently, our hospital had a guest speaker who talked about potential medical applications of nanotechnology. It was way over my head, but it sounded pretty cool.

While I was prepared for ongoing changes in medical knowledge, I failed to anticipate how quickly the business of medicine would change during my career. I think the need to keep up with ever-increasing financial and regulatory issues siphons a lot of time and energy that could be used to keep up with the medical knowledge base. I wasn’t prepared for this when I started my career.

Because it is the start of a new year, I thought I would highlight one issue related to CPT coding: Medicare stopped recognizing consult codes as of Jan. 1 (see “Consultation Elimination,” p. 31).

What It Means for Hospitalists

The good news is that we can just use initial hospital visit codes, inpatient or observation, for all new visits. For example, it won’t matter anymore whether I’m admitting and serving as attending for a patient, or whether a surgeon admitted the patient and asked me to consult for preoperative medical evaluation (“clearance”). I should use the same CPT code in either situation, simply appending a modifier if I’m the admitting physician. And for billing purposes, we won’t have to worry about documenting which doctor requested that we see the patient, though it is a good idea to document it as part of the clinical record anyway.

But it gets a little more complicated. The codes aren’t going away or being removed from the CPT “bible” published by the American Medical Association (AMA). Instead, Medicare simply won’t recognize them anymore. Other payors probably will follow suit within a few months, but that isn’t certain. So it is possible that when asked by a surgeon to provide a preoperative evaluation, you will need to bill an initial hospital (or office or nursing facility) care visit if the patient is on Medicare but bill a consult code if the patient has other insurance. You should check with your billers to ensure you’re doing this correctly.

Medicare-paid consults are at a slightly higher rate than the equivalent service billed as initial hospital care (e.g., when the hospitalist is attending). So a higher reimbursing code has been replaced with one that pays a little less. For example, a 99253 consultation code requires a detailed history, detailed examination, and medical decision-making of low complexity; last year, 99253 was reimbursed by Medicare at an average rate of $114.69. The equivalent admission code for a detailed history, detailed examination, and low-complexity medical decision-making is a 99221 code, for which Medicare pays about $99.90. This represents a difference of about 14%.

However, the net financial impact of this change probably will be positive for most HM groups because you probably bill very few initial consult codes, and instead were stuck billing a follow-up visit code when seeing co-management “consults” (i.e., a patient admitted by a surgeon who asks you to follow and manage diabetes and other medical issues). Now, at least in the case of Medicare, it is appropriate for us to bill an initial hospital visit code, which provides significantly higher reimbursement than follow-up codes.

In addition, there is a modest (about 0.3%) proposed increase in work relative value units attached to the initial hospital visit codes, which will benefit us not only when we’re consulting, but also when we admit and serve as a patient’s attending.

Some specialists may be less interested in consulting on our patients because the initial visit codes will reimburse a little less than similar consultation codes. I don’t anticipate this will be a significant problem for most of us, particularly since many specialists bill the highest level of consultation code (99255), which pays about the same as the equivalent admission code (99223).

Although I think elimination of the use of consultation codes seems like a reasonable step toward simplifying how hospitalists bill for our services, keeping up with these frequent coding changes requires a high level of diligence on our part, and on the part of our administrative and clerical staffs. And it consumes time and resources that I—and my team—could better spend keeping up with changes in clinical practice.

Perhaps when all the dust settles around the healthcare reform debate, we will begin to move toward new, more creative payment models that will allow us to focus on what we do best. TH

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988 and is cofounder and past president of SHM. He is a principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants, a national hospitalist practice management consulting firm (www.nelsonflores.com). He is also course co-director and faculty for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. This column represents his views and is not intended to reflect an official position of SHM.

The amount and complexity of medical knowledge we need to keep up with is changing and growing at a remarkable rate. I was trained in an era in which it was taken as a given that congestive heart failure patients should not receive beta-blockers; now it is a big mistake if we don’t prescribe them in most cases. But even before starting medical school, most of us realize that things will change a lot, and many of us see that as a good thing. It keeps our work interesting. Just recently, our hospital had a guest speaker who talked about potential medical applications of nanotechnology. It was way over my head, but it sounded pretty cool.

While I was prepared for ongoing changes in medical knowledge, I failed to anticipate how quickly the business of medicine would change during my career. I think the need to keep up with ever-increasing financial and regulatory issues siphons a lot of time and energy that could be used to keep up with the medical knowledge base. I wasn’t prepared for this when I started my career.

Because it is the start of a new year, I thought I would highlight one issue related to CPT coding: Medicare stopped recognizing consult codes as of Jan. 1 (see “Consultation Elimination,” p. 31).

What It Means for Hospitalists

The good news is that we can just use initial hospital visit codes, inpatient or observation, for all new visits. For example, it won’t matter anymore whether I’m admitting and serving as attending for a patient, or whether a surgeon admitted the patient and asked me to consult for preoperative medical evaluation (“clearance”). I should use the same CPT code in either situation, simply appending a modifier if I’m the admitting physician. And for billing purposes, we won’t have to worry about documenting which doctor requested that we see the patient, though it is a good idea to document it as part of the clinical record anyway.

But it gets a little more complicated. The codes aren’t going away or being removed from the CPT “bible” published by the American Medical Association (AMA). Instead, Medicare simply won’t recognize them anymore. Other payors probably will follow suit within a few months, but that isn’t certain. So it is possible that when asked by a surgeon to provide a preoperative evaluation, you will need to bill an initial hospital (or office or nursing facility) care visit if the patient is on Medicare but bill a consult code if the patient has other insurance. You should check with your billers to ensure you’re doing this correctly.

Medicare-paid consults are at a slightly higher rate than the equivalent service billed as initial hospital care (e.g., when the hospitalist is attending). So a higher reimbursing code has been replaced with one that pays a little less. For example, a 99253 consultation code requires a detailed history, detailed examination, and medical decision-making of low complexity; last year, 99253 was reimbursed by Medicare at an average rate of $114.69. The equivalent admission code for a detailed history, detailed examination, and low-complexity medical decision-making is a 99221 code, for which Medicare pays about $99.90. This represents a difference of about 14%.

However, the net financial impact of this change probably will be positive for most HM groups because you probably bill very few initial consult codes, and instead were stuck billing a follow-up visit code when seeing co-management “consults” (i.e., a patient admitted by a surgeon who asks you to follow and manage diabetes and other medical issues). Now, at least in the case of Medicare, it is appropriate for us to bill an initial hospital visit code, which provides significantly higher reimbursement than follow-up codes.

In addition, there is a modest (about 0.3%) proposed increase in work relative value units attached to the initial hospital visit codes, which will benefit us not only when we’re consulting, but also when we admit and serve as a patient’s attending.