User login

Pathological laughter and crying— pseudobulbar affect (PBA)—is a disorder of emotional expression characterized by uncontrollable outbursts of laughter or crying without an environmental trigger. Persons with PBA are at an increased risk of depressive and anxiety symptoms associated with an inappropriate outburst of emotion1; such emotional acts might be incongruent with their underlying emotional state.

When should you consider PBA?

Consider PBA in patients with new-onset emotional lability in the presence of certain neurologic conditions. PBA is most common in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and stroke, in which an incidence of >50% has been estimated.2 Other conditions associated with PBA include Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, frontotemporal dementia, traumatic brain injury, Alzheimer’s disease, epilepsy, normal pressure hydrocephalus, progressive supranuclear palsy, Wilson disease, and neurosyphilis.3

Avoid PBA misdiagnosis

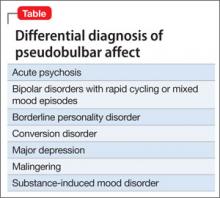

Depression is the most common PBA misdiagnosis (Table). However, many clinical features distinguish PBA episodes from depressive symptoms; the most prominent difference is duration. Depressive symptoms, including depressed mood, typically last weeks to months, but a PBA episode lasts seconds or minutes. In addition, crying, as a symptom of PBA, might be unrelated or exaggerated relative to the patient’s mood, but crying is congruent with subjective mood in depression. Other symptoms of depression—fatigue, anorexia, insomnia, anhedonia, and feelings of hopelessness and guilt— are not associated with pseudobulbar affect.

PBA also can be differentiated from bipolar disorder (BD) with rapid cycling or mixed mood episodes because of PBA’s relatively brief duration of laughing or crying episodes—with no mood disturbance between episodes—compared with the sustained changes in mood, cognition, and behavior seen in BD.

Options for treating PBA

Serotonergic therapies, such as amitriptyline and fluoxetine, may exert effects by increasing serotonin in the synapse; dextromethorphan may act via antiglutamatergic effects at N-methyl-d-aspartate receptors and sigma-1 receptors.4 Dextromethorphan binding is most prominent in the brainstem and cerebellum, brain areas known to be rich in sigma-1 receptors and key sites implicated in the pathophysiology of PBA. Although the precise mechanisms by which dextromethorphan ameliorates PBA are unknown, modulation of excessive glutamatergic transmission within corticopontine-cerebellar circuits may contribute to its benefits.

Disclosure

The author reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Tateno A, Jorge RE, Robinson RG. Pathological laughing and crying following traumatic brain injury. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2004;16(4):426-434.

2. Miller A, Pratt H, Schiffer RB. Pseudobulbar affect: the spectrum of clinical presentations, etiologies and treatments. Expert Rev Neurother. 2011;11(7):1077-1088.

3. Haiman G, Pratt H, Miller A. Brain responses to verbal stimuli among multiple sclerosis patients with pseudobulbar affect. J Neurol Sci. 2008;271(1-2):137-147.

4. Werling LL, Keller A, Frank JG, et al. A comparison of the binding profiles of dextromethorphan, memantine, fluoxetine and amitriptyline: treatment of involuntary emotional expression disorder. Exp Neurol. 2007;207(2): 248-257.

Pathological laughter and crying— pseudobulbar affect (PBA)—is a disorder of emotional expression characterized by uncontrollable outbursts of laughter or crying without an environmental trigger. Persons with PBA are at an increased risk of depressive and anxiety symptoms associated with an inappropriate outburst of emotion1; such emotional acts might be incongruent with their underlying emotional state.

When should you consider PBA?

Consider PBA in patients with new-onset emotional lability in the presence of certain neurologic conditions. PBA is most common in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and stroke, in which an incidence of >50% has been estimated.2 Other conditions associated with PBA include Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, frontotemporal dementia, traumatic brain injury, Alzheimer’s disease, epilepsy, normal pressure hydrocephalus, progressive supranuclear palsy, Wilson disease, and neurosyphilis.3

Avoid PBA misdiagnosis

Depression is the most common PBA misdiagnosis (Table). However, many clinical features distinguish PBA episodes from depressive symptoms; the most prominent difference is duration. Depressive symptoms, including depressed mood, typically last weeks to months, but a PBA episode lasts seconds or minutes. In addition, crying, as a symptom of PBA, might be unrelated or exaggerated relative to the patient’s mood, but crying is congruent with subjective mood in depression. Other symptoms of depression—fatigue, anorexia, insomnia, anhedonia, and feelings of hopelessness and guilt— are not associated with pseudobulbar affect.

PBA also can be differentiated from bipolar disorder (BD) with rapid cycling or mixed mood episodes because of PBA’s relatively brief duration of laughing or crying episodes—with no mood disturbance between episodes—compared with the sustained changes in mood, cognition, and behavior seen in BD.

Options for treating PBA

Serotonergic therapies, such as amitriptyline and fluoxetine, may exert effects by increasing serotonin in the synapse; dextromethorphan may act via antiglutamatergic effects at N-methyl-d-aspartate receptors and sigma-1 receptors.4 Dextromethorphan binding is most prominent in the brainstem and cerebellum, brain areas known to be rich in sigma-1 receptors and key sites implicated in the pathophysiology of PBA. Although the precise mechanisms by which dextromethorphan ameliorates PBA are unknown, modulation of excessive glutamatergic transmission within corticopontine-cerebellar circuits may contribute to its benefits.

Disclosure

The author reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Pathological laughter and crying— pseudobulbar affect (PBA)—is a disorder of emotional expression characterized by uncontrollable outbursts of laughter or crying without an environmental trigger. Persons with PBA are at an increased risk of depressive and anxiety symptoms associated with an inappropriate outburst of emotion1; such emotional acts might be incongruent with their underlying emotional state.

When should you consider PBA?

Consider PBA in patients with new-onset emotional lability in the presence of certain neurologic conditions. PBA is most common in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and stroke, in which an incidence of >50% has been estimated.2 Other conditions associated with PBA include Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, frontotemporal dementia, traumatic brain injury, Alzheimer’s disease, epilepsy, normal pressure hydrocephalus, progressive supranuclear palsy, Wilson disease, and neurosyphilis.3

Avoid PBA misdiagnosis

Depression is the most common PBA misdiagnosis (Table). However, many clinical features distinguish PBA episodes from depressive symptoms; the most prominent difference is duration. Depressive symptoms, including depressed mood, typically last weeks to months, but a PBA episode lasts seconds or minutes. In addition, crying, as a symptom of PBA, might be unrelated or exaggerated relative to the patient’s mood, but crying is congruent with subjective mood in depression. Other symptoms of depression—fatigue, anorexia, insomnia, anhedonia, and feelings of hopelessness and guilt— are not associated with pseudobulbar affect.

PBA also can be differentiated from bipolar disorder (BD) with rapid cycling or mixed mood episodes because of PBA’s relatively brief duration of laughing or crying episodes—with no mood disturbance between episodes—compared with the sustained changes in mood, cognition, and behavior seen in BD.

Options for treating PBA

Serotonergic therapies, such as amitriptyline and fluoxetine, may exert effects by increasing serotonin in the synapse; dextromethorphan may act via antiglutamatergic effects at N-methyl-d-aspartate receptors and sigma-1 receptors.4 Dextromethorphan binding is most prominent in the brainstem and cerebellum, brain areas known to be rich in sigma-1 receptors and key sites implicated in the pathophysiology of PBA. Although the precise mechanisms by which dextromethorphan ameliorates PBA are unknown, modulation of excessive glutamatergic transmission within corticopontine-cerebellar circuits may contribute to its benefits.

Disclosure

The author reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Tateno A, Jorge RE, Robinson RG. Pathological laughing and crying following traumatic brain injury. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2004;16(4):426-434.

2. Miller A, Pratt H, Schiffer RB. Pseudobulbar affect: the spectrum of clinical presentations, etiologies and treatments. Expert Rev Neurother. 2011;11(7):1077-1088.

3. Haiman G, Pratt H, Miller A. Brain responses to verbal stimuli among multiple sclerosis patients with pseudobulbar affect. J Neurol Sci. 2008;271(1-2):137-147.

4. Werling LL, Keller A, Frank JG, et al. A comparison of the binding profiles of dextromethorphan, memantine, fluoxetine and amitriptyline: treatment of involuntary emotional expression disorder. Exp Neurol. 2007;207(2): 248-257.

1. Tateno A, Jorge RE, Robinson RG. Pathological laughing and crying following traumatic brain injury. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2004;16(4):426-434.

2. Miller A, Pratt H, Schiffer RB. Pseudobulbar affect: the spectrum of clinical presentations, etiologies and treatments. Expert Rev Neurother. 2011;11(7):1077-1088.

3. Haiman G, Pratt H, Miller A. Brain responses to verbal stimuli among multiple sclerosis patients with pseudobulbar affect. J Neurol Sci. 2008;271(1-2):137-147.

4. Werling LL, Keller A, Frank JG, et al. A comparison of the binding profiles of dextromethorphan, memantine, fluoxetine and amitriptyline: treatment of involuntary emotional expression disorder. Exp Neurol. 2007;207(2): 248-257.