User login

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic, relapsing, inflammatory skin disease typically with childhood onset. In some cases, the condition persists, but AD usually resolves by the time a child reaches adulthood. Prevalence is difficult to estimate but, in developed countries, is approximately 15% to 30% among children and 2% to 10% among adults.1

Atopic dermatitis is characterized by chronically itchy dry skin, weeping erythematous papules and plaques, and lichenification. Furthermore, AD often is associated with other atopic diseases, such as food allergy, allergic rhinitis, and bronchial asthma.

In this article, we review the literature on the quality of life (QOL) of patients with AD. Our goals are to discuss the most common methods for measuring QOL in AD and how to use them; highlight specific alterations of QOL in AD; and review data about QOL of children with AD, which is underrepresented in the medical literature, as studies tend to focus on adults. In addition, we address the importance of assessing QOL in patients with AD due to the psychological burden of the disease.

Quality of Life

The harmful effects of AD can include a range of areas, including

Because QOL is an important instrument used in many AD studies, we call attention to the work of the Harmonising Outcome Measures for Eczema (HOME) initiative, which established a core outcome set for all AD clinical trials to enable comparison of results of individual studies.2 Quality of life was identified in HOME as one of 4 basic outcome measures that should be included in every AD trial (the others are clinician-reported signs, patient-reported symptoms, and long-term control).3 According to the recent agreement, the following QOL instruments should be used: Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) for adults, Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index (CDLQI) for children, and Infants’ Dermatitis Quality of Life Index (IDQOL) for infants.4

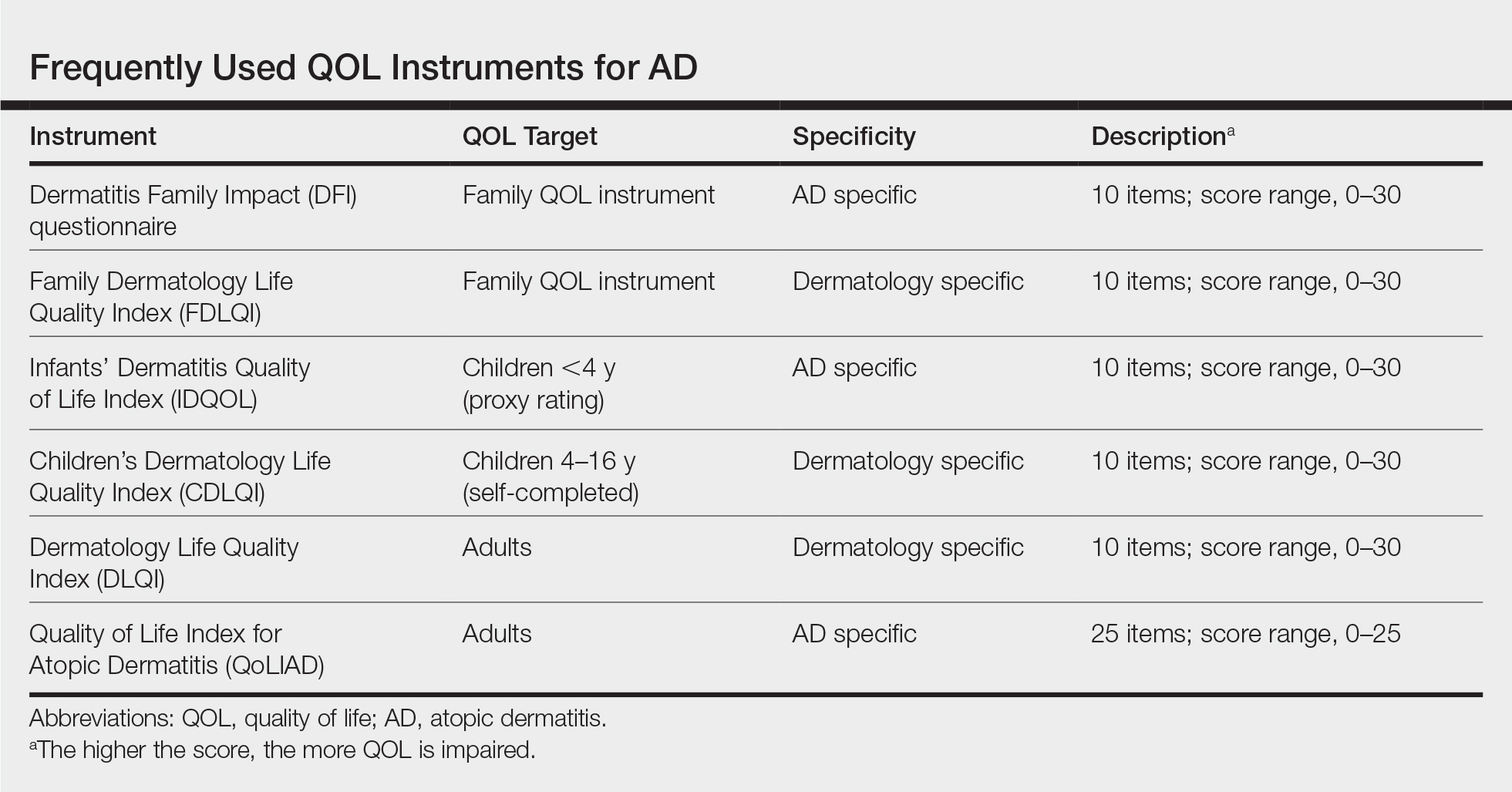

In dermatology, these instruments can be divided into 3 basic categories: generic, dermatology specific, and disease specific.5 Generic QOL questionnaires are beneficial when comparing the QOL of an AD patient to patients with other conditions or to healthy individuals. On the other hand, dermatology-specific and AD-specific methods are more effective instruments for detecting impairments linked directly to the disease and, therefore, are more sensitive to changes in QOL.5 Some of the most frequently used QOL measures5,6 for AD along with their key attributes are

Given that AD is a chronic disease that requires constant care, parents/guardians or the partner of the patient usually are affected as well. To detect this effect, the Family Dermatology Life Quality Index (FDLQI), a dermatology-specific instrument, measures the QOL in family members of dermatology patients.7 The Dermatitis Family Impact (DFI)8 is a disease-specific method for assessing how having a child with AD can impact the QOL of family members; it is a 10-item questionnaire completed by an adult family member. The FDLQI7 and DFI8 both help to understand the secondary impact of the disease.

In contrast, several other methods that also are administered by a parent/guardian assess how the parent perceives the QOL of their child with AD; these methods are essential for small children and infants who cannot answer questions themselves. The IDQOL9 was designed to assess the QOL of patients younger than 4 years using a parent-completed questionnaire. For older children and adolescents aged 4 to 16 years, the CDLQI10 is a widely used instrument; the questionnaire is completed by the child and is available in a cartoon format.10

For patients older than 16 years, 2 important instruments are the DLQI, a generic dermatology instrument, and the Quality of Life Index for Atopic Dermatitis (QoLIAD).11

Clearly it can be troublesome for researchers and clinicians to find the most suitable instrument to evaluate QOL in AD patients. To make this task easier, the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology Task Force released a position paper with the following recommendations: (1) only validated instruments should be used, and (2) their use should be based on the age of the patients for which the instruments were designed. It is reommended that researchers use a combination of a generic and a dermatology-specific or AD-specific instrument, whereas clinicians should apply a dermatology-specific or AD-specific method, or both.5

Alterations of QOL in AD

Sleep Disturbance in AD

Sleep disorders observed in AD include difficulty falling asleep, frequent waking episodes, shorter sleep duration, and feelings of inadequate sleep, which often result in impairment of daily activity.12,13 Correlation has been found between sleep quality and QOL in both children and adults.14 Approximately 60% of children affected by AD experience a sleep disturbance,15 which seems to correlate well with disease severity.16 A US study found that adults with AD are more likely to experience a sleep disturbance, which often affects daytime functioning and work productivity.13

Financial Aspects and Impact on Work

The financial burden of AD is extensive.17 There are direct medical costs, including medication, visits to the physician, alternative therapies, and nonprescription products. Patients tend to spend relevant money on such items as moisturizers, bath products, antihistamines, topical steroids, and topical antibiotics.18,19 However, it seems that most of the cost of AD is due to indirect and nonmedical costs, including transportation to medical visits; loss of work days; extra childcare; and expenditures associated with lifestyle changes,19,20 such as modifying diet, wearing special clothes, using special bed linens, and purchasing special household items (eg, anti–dust mite vacuum cleaner, humidifier, new carpeting).17,19

Absenteeism from work often is a consequence of physician appointments; in addition, parents/guardians of a child with AD often miss work due to medical care. Even at work, patients (or parents/guardians) often experience decreased work productivity (so-called presenteeism) due to loss of sleep and anxiety.21 In addressing the effects of AD on work life, a systematic literature review found that AD strongly affects sick leave and might have an impact on job choice and change or loss of job.22

Furthermore, according to Su et al,23 the costs of AD are related to disease severity. Moreover, their data suggest that among chronic childhood diseases, the financial burden of AD is greater than the cost of asthma and similar to the cost of diabetes mellitus.23

Association Between QOL and Disease Severity

A large observational study found that improvement in AD severity was followed by an increase in QOL.24 A positive correlation between disease severity and QOL has been found in other studies,25,26 though no correlation or only moderate correlation also has been reported.27 Apparently, in addition to QOL, disease severity scores are substantial parameters in the evaluation of distress caused by AD; the HOME initiative has identified clinician-reported signs and patient-reported symptoms as 2 of 4 core outcomes domains to include in all future AD clinical trials.3 For measuring symptoms, the Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM) is the recommended instrument.28 Regarding clinical signs, the HOME group named the Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) as the preferred instrument.29

Psychological Burden

Stress is a triggering factor for AD, but the connection between skin and mind appears bidirectional. The biological reaction to stress probably lowers the itch threshold and disrupts the skin barrier.30 The Global Burden of Disease Study showed that skin diseases are the fourth leading cause of nonfatal disease burden.31 There are several factors—pruritus, scratch, and pain—that can all lead to sleep deprivation and daytime fatigue. Based on our experience, if lesions develop on visible areas, patients can feel stigmatized, which restricts their social life.

The most common psychological comorbidities of AD are anxiety and depression. In a cross-sectional, multicenter study, there was a significantly higher prevalence of depression (P<.001) and anxiety disorder (P=.02) among patients with common skin diseases compared to a control group.32 In a study that assessed AD patients, researchers found a higher risk of depression and anxiety.33 Suicidal ideation also is more common in the population with AD32,34; a study showed that the risk of suicidal ideation in adolescents was nearly 4-fold in patients with itching skin lesions compared to those without itch.34

According to Linnet and Jemec,35 mental and psychological comorbidities of AD are associated with lower QOL, not with clinical severity. As a result, to improve QOL in AD, one should take care of both dermatological and psychological problems. It has been demonstrated that psychological interventions, such as autogenic training, cognitive-behavioral therapy, relaxation techniques, habit reversal training,36 and hypnotherapy37 might be helpful in individual cases; educational interventions also are recommended.36 With these adjuvant therapies, psychological status, unpleasant clinical symptoms, and QOL could be improved, though further studies are needed to confirm these benefits.

Conclusion

Atopic dermatitis places a notable burden on patients and their families. The degree of burden is probably related to disease severity. For measuring QOL, researchers and clinicians should use validated methods suited to the age of the patients for which they were designed. More studies are needed to assess the effects of different treatments on QOL. Besides pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy and educational programs might be beneficial for improving QOL, another important area to be studied.

- Bieber T. Atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1483-1494.

- Schmitt J, Williams H; HOME Development Group. Harmonising Outcome Measures for Eczema (HOME). report from the First International Consensus Meeting (HOME 1), 24 July 2010, Munich, Germany. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:1166-1168.

- Schmitt J, Spuls P, Boers M, et al. Towards global consensus on outcome measures for atopic eczema research: results of the HOME II meeting. Allergy. 2012;67:1111-1117.

- Quality of Life (QoL). Harmonising Outcome Measures for Eczema (HOME) website. http://www.homeforeczema.org/research/quality-of-life.aspx. Accessed August 18, 2019.

Chernyshov PV, Tomas-Aragones L, Manolache L, et al; EADV Quality of Life Task Force. Quality of life measurement in atopic dermatitis. Position paper of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV) Task Force on quality of life. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:576-593. - Hill MK, Kheirandish Pishkenari A, Braunberger TL, et al. Recent trends in disease severity and quality of life instruments for patients with atopic dermatitis: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:906-917.

- Basra MK, Sue-Ho R, Finlay AY. The Family Dermatology Life Quality Index: measuring the secondary impact of skin disease. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:528-538.

- Dodington SR, Basra MK, Finlay AY, et al. The Dermatitis Family Impact questionnaire: a review of its measurement properties and clinical application. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:31-46.

- Lewis-Jones MS, Finlay AY, Dykes PJ. The Infants’ Dermatitis Quality of Life Index. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:104-110.

- Holme SA, Man I, Sharpe JL, et al. The Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index: validation of the cartoon version. Br J Dermatol. 2003;148:285-290.

- Whalley D, McKenna SP, Dewar AL, et al. A new instrument for assessing quality of life in atopic dermatitis: international development of the Quality of Life Index for Atopic Dermatitis (QoLIAD). Br J Dermatol. 2004;150:274-283.

- Jeon C, Yan D, Nakamura M, et al. Frequency and management of sleep disturbance in adults with atopic dermatitis: a systematic review. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2017;7:349-364.

- Yu SH, Attarian H, Zee P, et al. Burden of sleep and fatigue in US adults with atopic dermatitis. Dermatitis. 2016;27:50-58.

- Kong TS, Han TY, Lee JH, et al. Correlation between severity of atopic dermatitis and sleep quality in children and adults. Ann Dermatol. 2016;28:321-326.

- Fishbein AB, Mueller K, Kruse L, et al. Sleep disturbance in children with moderate/severe atopic dermatitis: a case-control study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:336-341.

- Chamlin SL, Mattson CL, Frieden IJ, et al. The price of pruritus: sleep disturbance and cosleeping in atopic dermatitis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:745-750.

- Emerson RM, Williams HC, Allen BR. What is the cost of atopic dermatitis in preschool children? Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:514-522.

- Filanovsky MG, Pootongkam S, Tamburro JE, et al. The financial and emotional impact of atopic dermatitis on children and their families. J Pediatr. 2016;169:284-290.

- Fivenson D, Arnold RJ, Kaniecki DJ, et al. The effect of atopic dermatitis on total burden of illness and quality of life on adults and children in a large managed care organization. J Manag Care Pharm. 2002;8:333-342.

- Carroll CL, Balkrishnan R, Feldman SR, et al. The burden of atopic dermatitis: impact on the patient, family, and society. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:192-199.

- Drucker AM, Wang AR, Qureshi AA. Research gaps in quality of life and economic burden of atopic dermatitis: the National Eczema Association Burden of Disease Audit. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:873-874.

- Nørreslet LB, Ebbehøj NE, Ellekilde Bonde JP, et al. The impact of atopic dermatitis on work life—a systematic review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:23-38.

- Su JC, Kemp AS, Varigos GA, et al. Atopic eczema: its impact on the family and financial cost. Arch Dis Child. 1997;76:159-162.

- Coutanceau C, Stalder JF. Analysis of correlations between patient-oriented SCORAD (PO-SCORAD) and other assessment scores of atopic dermatitis severity and quality of life. Dermatology. 2014;229:248-255.

- Ben-Gashir MA, Seed PT, Hay RJ. Quality of life and disease severity are correlated in children with atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2004;150:284-290.

- van Valburg RW, Willemsen MG, Dirven-Meijer PC, et al. Quality of life measurement and its relationship to disease severity in children with atopic dermatitis in general practice. Acta Derm Venereol. 2011;91:147-151.

- Haeck IM, ten Berge O, van Velsen SG, et al. Moderate correlation between quality of life and disease activity in adult patients with atopic dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:236-241.

- Spuls PI, Gerbens LAA, Simpson E, et al; HOME initiative collaborators. Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM), a core instrument to measure symptoms in clinical trials: a Harmonising Outcome Measures for Eczema (HOME) statement. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:979-984.

- Schmitt J, Spuls PI, Thomas KS, et al; HOME initiative collaborators. The Harmonising Outcome Measures for Eczema (HOME) statement to assess clinical signs of atopic eczema in trials. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134:800-807.

- Oh SH, Bae BG, Park CO, et al. Association of stress with symptoms of atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2010;90:582-588.

- Hay RJ, Johns NE, Williams HC, et al. The global burden of skin disease in 2010: an analysis of the prevalence and impact of skin conditions. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:1527-1534.

- Dalgard FJ, Gieler U, Tomas-Aragones L, et al. The psychological burden of skin diseases: a cross-sectional multicenter study among dermatological out-patients in 13 European countries. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:984-991.

- Cheng CM, Hsu JW, Huang KL, et al. Risk of developing major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders among adolescents and adults with atopic dermatitis: a nationwide longitudinal study. J Affect Disord. 2015;178:60-65.

Halvorsen JA, Lien L, Dalgard F, et al. Suicidal ideation, mental health problems, and social function in adolescents with eczema: a population-based study. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:1847-1854. - Linnet J, Jemec GB. An assessment of anxiety and dermatology life quality in patients with atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:268-272.

- Ring J, Alomar A, Bieber T, et al; European Dermatology Forum; European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology; European Task Force on Atopic Dermatitis; European Federation of Allergy; European Society of Pediatric Dermatology; Global Allergy and Asthma European Network. Guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) Part II. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:1176-1193.

- Perczel K, Gál J. Hypnotherapy of atopic dermatitis in an adult. case report. Orv Hetil. 2016;157:111-115.

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic, relapsing, inflammatory skin disease typically with childhood onset. In some cases, the condition persists, but AD usually resolves by the time a child reaches adulthood. Prevalence is difficult to estimate but, in developed countries, is approximately 15% to 30% among children and 2% to 10% among adults.1

Atopic dermatitis is characterized by chronically itchy dry skin, weeping erythematous papules and plaques, and lichenification. Furthermore, AD often is associated with other atopic diseases, such as food allergy, allergic rhinitis, and bronchial asthma.

In this article, we review the literature on the quality of life (QOL) of patients with AD. Our goals are to discuss the most common methods for measuring QOL in AD and how to use them; highlight specific alterations of QOL in AD; and review data about QOL of children with AD, which is underrepresented in the medical literature, as studies tend to focus on adults. In addition, we address the importance of assessing QOL in patients with AD due to the psychological burden of the disease.

Quality of Life

The harmful effects of AD can include a range of areas, including

Because QOL is an important instrument used in many AD studies, we call attention to the work of the Harmonising Outcome Measures for Eczema (HOME) initiative, which established a core outcome set for all AD clinical trials to enable comparison of results of individual studies.2 Quality of life was identified in HOME as one of 4 basic outcome measures that should be included in every AD trial (the others are clinician-reported signs, patient-reported symptoms, and long-term control).3 According to the recent agreement, the following QOL instruments should be used: Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) for adults, Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index (CDLQI) for children, and Infants’ Dermatitis Quality of Life Index (IDQOL) for infants.4

In dermatology, these instruments can be divided into 3 basic categories: generic, dermatology specific, and disease specific.5 Generic QOL questionnaires are beneficial when comparing the QOL of an AD patient to patients with other conditions or to healthy individuals. On the other hand, dermatology-specific and AD-specific methods are more effective instruments for detecting impairments linked directly to the disease and, therefore, are more sensitive to changes in QOL.5 Some of the most frequently used QOL measures5,6 for AD along with their key attributes are

Given that AD is a chronic disease that requires constant care, parents/guardians or the partner of the patient usually are affected as well. To detect this effect, the Family Dermatology Life Quality Index (FDLQI), a dermatology-specific instrument, measures the QOL in family members of dermatology patients.7 The Dermatitis Family Impact (DFI)8 is a disease-specific method for assessing how having a child with AD can impact the QOL of family members; it is a 10-item questionnaire completed by an adult family member. The FDLQI7 and DFI8 both help to understand the secondary impact of the disease.

In contrast, several other methods that also are administered by a parent/guardian assess how the parent perceives the QOL of their child with AD; these methods are essential for small children and infants who cannot answer questions themselves. The IDQOL9 was designed to assess the QOL of patients younger than 4 years using a parent-completed questionnaire. For older children and adolescents aged 4 to 16 years, the CDLQI10 is a widely used instrument; the questionnaire is completed by the child and is available in a cartoon format.10

For patients older than 16 years, 2 important instruments are the DLQI, a generic dermatology instrument, and the Quality of Life Index for Atopic Dermatitis (QoLIAD).11

Clearly it can be troublesome for researchers and clinicians to find the most suitable instrument to evaluate QOL in AD patients. To make this task easier, the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology Task Force released a position paper with the following recommendations: (1) only validated instruments should be used, and (2) their use should be based on the age of the patients for which the instruments were designed. It is reommended that researchers use a combination of a generic and a dermatology-specific or AD-specific instrument, whereas clinicians should apply a dermatology-specific or AD-specific method, or both.5

Alterations of QOL in AD

Sleep Disturbance in AD

Sleep disorders observed in AD include difficulty falling asleep, frequent waking episodes, shorter sleep duration, and feelings of inadequate sleep, which often result in impairment of daily activity.12,13 Correlation has been found between sleep quality and QOL in both children and adults.14 Approximately 60% of children affected by AD experience a sleep disturbance,15 which seems to correlate well with disease severity.16 A US study found that adults with AD are more likely to experience a sleep disturbance, which often affects daytime functioning and work productivity.13

Financial Aspects and Impact on Work

The financial burden of AD is extensive.17 There are direct medical costs, including medication, visits to the physician, alternative therapies, and nonprescription products. Patients tend to spend relevant money on such items as moisturizers, bath products, antihistamines, topical steroids, and topical antibiotics.18,19 However, it seems that most of the cost of AD is due to indirect and nonmedical costs, including transportation to medical visits; loss of work days; extra childcare; and expenditures associated with lifestyle changes,19,20 such as modifying diet, wearing special clothes, using special bed linens, and purchasing special household items (eg, anti–dust mite vacuum cleaner, humidifier, new carpeting).17,19

Absenteeism from work often is a consequence of physician appointments; in addition, parents/guardians of a child with AD often miss work due to medical care. Even at work, patients (or parents/guardians) often experience decreased work productivity (so-called presenteeism) due to loss of sleep and anxiety.21 In addressing the effects of AD on work life, a systematic literature review found that AD strongly affects sick leave and might have an impact on job choice and change or loss of job.22

Furthermore, according to Su et al,23 the costs of AD are related to disease severity. Moreover, their data suggest that among chronic childhood diseases, the financial burden of AD is greater than the cost of asthma and similar to the cost of diabetes mellitus.23

Association Between QOL and Disease Severity

A large observational study found that improvement in AD severity was followed by an increase in QOL.24 A positive correlation between disease severity and QOL has been found in other studies,25,26 though no correlation or only moderate correlation also has been reported.27 Apparently, in addition to QOL, disease severity scores are substantial parameters in the evaluation of distress caused by AD; the HOME initiative has identified clinician-reported signs and patient-reported symptoms as 2 of 4 core outcomes domains to include in all future AD clinical trials.3 For measuring symptoms, the Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM) is the recommended instrument.28 Regarding clinical signs, the HOME group named the Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) as the preferred instrument.29

Psychological Burden

Stress is a triggering factor for AD, but the connection between skin and mind appears bidirectional. The biological reaction to stress probably lowers the itch threshold and disrupts the skin barrier.30 The Global Burden of Disease Study showed that skin diseases are the fourth leading cause of nonfatal disease burden.31 There are several factors—pruritus, scratch, and pain—that can all lead to sleep deprivation and daytime fatigue. Based on our experience, if lesions develop on visible areas, patients can feel stigmatized, which restricts their social life.

The most common psychological comorbidities of AD are anxiety and depression. In a cross-sectional, multicenter study, there was a significantly higher prevalence of depression (P<.001) and anxiety disorder (P=.02) among patients with common skin diseases compared to a control group.32 In a study that assessed AD patients, researchers found a higher risk of depression and anxiety.33 Suicidal ideation also is more common in the population with AD32,34; a study showed that the risk of suicidal ideation in adolescents was nearly 4-fold in patients with itching skin lesions compared to those without itch.34

According to Linnet and Jemec,35 mental and psychological comorbidities of AD are associated with lower QOL, not with clinical severity. As a result, to improve QOL in AD, one should take care of both dermatological and psychological problems. It has been demonstrated that psychological interventions, such as autogenic training, cognitive-behavioral therapy, relaxation techniques, habit reversal training,36 and hypnotherapy37 might be helpful in individual cases; educational interventions also are recommended.36 With these adjuvant therapies, psychological status, unpleasant clinical symptoms, and QOL could be improved, though further studies are needed to confirm these benefits.

Conclusion

Atopic dermatitis places a notable burden on patients and their families. The degree of burden is probably related to disease severity. For measuring QOL, researchers and clinicians should use validated methods suited to the age of the patients for which they were designed. More studies are needed to assess the effects of different treatments on QOL. Besides pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy and educational programs might be beneficial for improving QOL, another important area to be studied.

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic, relapsing, inflammatory skin disease typically with childhood onset. In some cases, the condition persists, but AD usually resolves by the time a child reaches adulthood. Prevalence is difficult to estimate but, in developed countries, is approximately 15% to 30% among children and 2% to 10% among adults.1

Atopic dermatitis is characterized by chronically itchy dry skin, weeping erythematous papules and plaques, and lichenification. Furthermore, AD often is associated with other atopic diseases, such as food allergy, allergic rhinitis, and bronchial asthma.

In this article, we review the literature on the quality of life (QOL) of patients with AD. Our goals are to discuss the most common methods for measuring QOL in AD and how to use them; highlight specific alterations of QOL in AD; and review data about QOL of children with AD, which is underrepresented in the medical literature, as studies tend to focus on adults. In addition, we address the importance of assessing QOL in patients with AD due to the psychological burden of the disease.

Quality of Life

The harmful effects of AD can include a range of areas, including

Because QOL is an important instrument used in many AD studies, we call attention to the work of the Harmonising Outcome Measures for Eczema (HOME) initiative, which established a core outcome set for all AD clinical trials to enable comparison of results of individual studies.2 Quality of life was identified in HOME as one of 4 basic outcome measures that should be included in every AD trial (the others are clinician-reported signs, patient-reported symptoms, and long-term control).3 According to the recent agreement, the following QOL instruments should be used: Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) for adults, Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index (CDLQI) for children, and Infants’ Dermatitis Quality of Life Index (IDQOL) for infants.4

In dermatology, these instruments can be divided into 3 basic categories: generic, dermatology specific, and disease specific.5 Generic QOL questionnaires are beneficial when comparing the QOL of an AD patient to patients with other conditions or to healthy individuals. On the other hand, dermatology-specific and AD-specific methods are more effective instruments for detecting impairments linked directly to the disease and, therefore, are more sensitive to changes in QOL.5 Some of the most frequently used QOL measures5,6 for AD along with their key attributes are

Given that AD is a chronic disease that requires constant care, parents/guardians or the partner of the patient usually are affected as well. To detect this effect, the Family Dermatology Life Quality Index (FDLQI), a dermatology-specific instrument, measures the QOL in family members of dermatology patients.7 The Dermatitis Family Impact (DFI)8 is a disease-specific method for assessing how having a child with AD can impact the QOL of family members; it is a 10-item questionnaire completed by an adult family member. The FDLQI7 and DFI8 both help to understand the secondary impact of the disease.

In contrast, several other methods that also are administered by a parent/guardian assess how the parent perceives the QOL of their child with AD; these methods are essential for small children and infants who cannot answer questions themselves. The IDQOL9 was designed to assess the QOL of patients younger than 4 years using a parent-completed questionnaire. For older children and adolescents aged 4 to 16 years, the CDLQI10 is a widely used instrument; the questionnaire is completed by the child and is available in a cartoon format.10

For patients older than 16 years, 2 important instruments are the DLQI, a generic dermatology instrument, and the Quality of Life Index for Atopic Dermatitis (QoLIAD).11

Clearly it can be troublesome for researchers and clinicians to find the most suitable instrument to evaluate QOL in AD patients. To make this task easier, the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology Task Force released a position paper with the following recommendations: (1) only validated instruments should be used, and (2) their use should be based on the age of the patients for which the instruments were designed. It is reommended that researchers use a combination of a generic and a dermatology-specific or AD-specific instrument, whereas clinicians should apply a dermatology-specific or AD-specific method, or both.5

Alterations of QOL in AD

Sleep Disturbance in AD

Sleep disorders observed in AD include difficulty falling asleep, frequent waking episodes, shorter sleep duration, and feelings of inadequate sleep, which often result in impairment of daily activity.12,13 Correlation has been found between sleep quality and QOL in both children and adults.14 Approximately 60% of children affected by AD experience a sleep disturbance,15 which seems to correlate well with disease severity.16 A US study found that adults with AD are more likely to experience a sleep disturbance, which often affects daytime functioning and work productivity.13

Financial Aspects and Impact on Work

The financial burden of AD is extensive.17 There are direct medical costs, including medication, visits to the physician, alternative therapies, and nonprescription products. Patients tend to spend relevant money on such items as moisturizers, bath products, antihistamines, topical steroids, and topical antibiotics.18,19 However, it seems that most of the cost of AD is due to indirect and nonmedical costs, including transportation to medical visits; loss of work days; extra childcare; and expenditures associated with lifestyle changes,19,20 such as modifying diet, wearing special clothes, using special bed linens, and purchasing special household items (eg, anti–dust mite vacuum cleaner, humidifier, new carpeting).17,19

Absenteeism from work often is a consequence of physician appointments; in addition, parents/guardians of a child with AD often miss work due to medical care. Even at work, patients (or parents/guardians) often experience decreased work productivity (so-called presenteeism) due to loss of sleep and anxiety.21 In addressing the effects of AD on work life, a systematic literature review found that AD strongly affects sick leave and might have an impact on job choice and change or loss of job.22

Furthermore, according to Su et al,23 the costs of AD are related to disease severity. Moreover, their data suggest that among chronic childhood diseases, the financial burden of AD is greater than the cost of asthma and similar to the cost of diabetes mellitus.23

Association Between QOL and Disease Severity

A large observational study found that improvement in AD severity was followed by an increase in QOL.24 A positive correlation between disease severity and QOL has been found in other studies,25,26 though no correlation or only moderate correlation also has been reported.27 Apparently, in addition to QOL, disease severity scores are substantial parameters in the evaluation of distress caused by AD; the HOME initiative has identified clinician-reported signs and patient-reported symptoms as 2 of 4 core outcomes domains to include in all future AD clinical trials.3 For measuring symptoms, the Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM) is the recommended instrument.28 Regarding clinical signs, the HOME group named the Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) as the preferred instrument.29

Psychological Burden

Stress is a triggering factor for AD, but the connection between skin and mind appears bidirectional. The biological reaction to stress probably lowers the itch threshold and disrupts the skin barrier.30 The Global Burden of Disease Study showed that skin diseases are the fourth leading cause of nonfatal disease burden.31 There are several factors—pruritus, scratch, and pain—that can all lead to sleep deprivation and daytime fatigue. Based on our experience, if lesions develop on visible areas, patients can feel stigmatized, which restricts their social life.

The most common psychological comorbidities of AD are anxiety and depression. In a cross-sectional, multicenter study, there was a significantly higher prevalence of depression (P<.001) and anxiety disorder (P=.02) among patients with common skin diseases compared to a control group.32 In a study that assessed AD patients, researchers found a higher risk of depression and anxiety.33 Suicidal ideation also is more common in the population with AD32,34; a study showed that the risk of suicidal ideation in adolescents was nearly 4-fold in patients with itching skin lesions compared to those without itch.34

According to Linnet and Jemec,35 mental and psychological comorbidities of AD are associated with lower QOL, not with clinical severity. As a result, to improve QOL in AD, one should take care of both dermatological and psychological problems. It has been demonstrated that psychological interventions, such as autogenic training, cognitive-behavioral therapy, relaxation techniques, habit reversal training,36 and hypnotherapy37 might be helpful in individual cases; educational interventions also are recommended.36 With these adjuvant therapies, psychological status, unpleasant clinical symptoms, and QOL could be improved, though further studies are needed to confirm these benefits.

Conclusion

Atopic dermatitis places a notable burden on patients and their families. The degree of burden is probably related to disease severity. For measuring QOL, researchers and clinicians should use validated methods suited to the age of the patients for which they were designed. More studies are needed to assess the effects of different treatments on QOL. Besides pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy and educational programs might be beneficial for improving QOL, another important area to be studied.

- Bieber T. Atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1483-1494.

- Schmitt J, Williams H; HOME Development Group. Harmonising Outcome Measures for Eczema (HOME). report from the First International Consensus Meeting (HOME 1), 24 July 2010, Munich, Germany. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:1166-1168.

- Schmitt J, Spuls P, Boers M, et al. Towards global consensus on outcome measures for atopic eczema research: results of the HOME II meeting. Allergy. 2012;67:1111-1117.

- Quality of Life (QoL). Harmonising Outcome Measures for Eczema (HOME) website. http://www.homeforeczema.org/research/quality-of-life.aspx. Accessed August 18, 2019.

Chernyshov PV, Tomas-Aragones L, Manolache L, et al; EADV Quality of Life Task Force. Quality of life measurement in atopic dermatitis. Position paper of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV) Task Force on quality of life. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:576-593. - Hill MK, Kheirandish Pishkenari A, Braunberger TL, et al. Recent trends in disease severity and quality of life instruments for patients with atopic dermatitis: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:906-917.

- Basra MK, Sue-Ho R, Finlay AY. The Family Dermatology Life Quality Index: measuring the secondary impact of skin disease. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:528-538.

- Dodington SR, Basra MK, Finlay AY, et al. The Dermatitis Family Impact questionnaire: a review of its measurement properties and clinical application. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:31-46.

- Lewis-Jones MS, Finlay AY, Dykes PJ. The Infants’ Dermatitis Quality of Life Index. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:104-110.

- Holme SA, Man I, Sharpe JL, et al. The Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index: validation of the cartoon version. Br J Dermatol. 2003;148:285-290.

- Whalley D, McKenna SP, Dewar AL, et al. A new instrument for assessing quality of life in atopic dermatitis: international development of the Quality of Life Index for Atopic Dermatitis (QoLIAD). Br J Dermatol. 2004;150:274-283.

- Jeon C, Yan D, Nakamura M, et al. Frequency and management of sleep disturbance in adults with atopic dermatitis: a systematic review. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2017;7:349-364.

- Yu SH, Attarian H, Zee P, et al. Burden of sleep and fatigue in US adults with atopic dermatitis. Dermatitis. 2016;27:50-58.

- Kong TS, Han TY, Lee JH, et al. Correlation between severity of atopic dermatitis and sleep quality in children and adults. Ann Dermatol. 2016;28:321-326.

- Fishbein AB, Mueller K, Kruse L, et al. Sleep disturbance in children with moderate/severe atopic dermatitis: a case-control study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:336-341.

- Chamlin SL, Mattson CL, Frieden IJ, et al. The price of pruritus: sleep disturbance and cosleeping in atopic dermatitis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:745-750.

- Emerson RM, Williams HC, Allen BR. What is the cost of atopic dermatitis in preschool children? Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:514-522.

- Filanovsky MG, Pootongkam S, Tamburro JE, et al. The financial and emotional impact of atopic dermatitis on children and their families. J Pediatr. 2016;169:284-290.

- Fivenson D, Arnold RJ, Kaniecki DJ, et al. The effect of atopic dermatitis on total burden of illness and quality of life on adults and children in a large managed care organization. J Manag Care Pharm. 2002;8:333-342.

- Carroll CL, Balkrishnan R, Feldman SR, et al. The burden of atopic dermatitis: impact on the patient, family, and society. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:192-199.

- Drucker AM, Wang AR, Qureshi AA. Research gaps in quality of life and economic burden of atopic dermatitis: the National Eczema Association Burden of Disease Audit. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:873-874.

- Nørreslet LB, Ebbehøj NE, Ellekilde Bonde JP, et al. The impact of atopic dermatitis on work life—a systematic review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:23-38.

- Su JC, Kemp AS, Varigos GA, et al. Atopic eczema: its impact on the family and financial cost. Arch Dis Child. 1997;76:159-162.

- Coutanceau C, Stalder JF. Analysis of correlations between patient-oriented SCORAD (PO-SCORAD) and other assessment scores of atopic dermatitis severity and quality of life. Dermatology. 2014;229:248-255.

- Ben-Gashir MA, Seed PT, Hay RJ. Quality of life and disease severity are correlated in children with atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2004;150:284-290.

- van Valburg RW, Willemsen MG, Dirven-Meijer PC, et al. Quality of life measurement and its relationship to disease severity in children with atopic dermatitis in general practice. Acta Derm Venereol. 2011;91:147-151.

- Haeck IM, ten Berge O, van Velsen SG, et al. Moderate correlation between quality of life and disease activity in adult patients with atopic dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:236-241.

- Spuls PI, Gerbens LAA, Simpson E, et al; HOME initiative collaborators. Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM), a core instrument to measure symptoms in clinical trials: a Harmonising Outcome Measures for Eczema (HOME) statement. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:979-984.

- Schmitt J, Spuls PI, Thomas KS, et al; HOME initiative collaborators. The Harmonising Outcome Measures for Eczema (HOME) statement to assess clinical signs of atopic eczema in trials. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134:800-807.

- Oh SH, Bae BG, Park CO, et al. Association of stress with symptoms of atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2010;90:582-588.

- Hay RJ, Johns NE, Williams HC, et al. The global burden of skin disease in 2010: an analysis of the prevalence and impact of skin conditions. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:1527-1534.

- Dalgard FJ, Gieler U, Tomas-Aragones L, et al. The psychological burden of skin diseases: a cross-sectional multicenter study among dermatological out-patients in 13 European countries. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:984-991.

- Cheng CM, Hsu JW, Huang KL, et al. Risk of developing major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders among adolescents and adults with atopic dermatitis: a nationwide longitudinal study. J Affect Disord. 2015;178:60-65.

Halvorsen JA, Lien L, Dalgard F, et al. Suicidal ideation, mental health problems, and social function in adolescents with eczema: a population-based study. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:1847-1854. - Linnet J, Jemec GB. An assessment of anxiety and dermatology life quality in patients with atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:268-272.

- Ring J, Alomar A, Bieber T, et al; European Dermatology Forum; European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology; European Task Force on Atopic Dermatitis; European Federation of Allergy; European Society of Pediatric Dermatology; Global Allergy and Asthma European Network. Guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) Part II. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:1176-1193.

- Perczel K, Gál J. Hypnotherapy of atopic dermatitis in an adult. case report. Orv Hetil. 2016;157:111-115.

- Bieber T. Atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1483-1494.

- Schmitt J, Williams H; HOME Development Group. Harmonising Outcome Measures for Eczema (HOME). report from the First International Consensus Meeting (HOME 1), 24 July 2010, Munich, Germany. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:1166-1168.

- Schmitt J, Spuls P, Boers M, et al. Towards global consensus on outcome measures for atopic eczema research: results of the HOME II meeting. Allergy. 2012;67:1111-1117.

- Quality of Life (QoL). Harmonising Outcome Measures for Eczema (HOME) website. http://www.homeforeczema.org/research/quality-of-life.aspx. Accessed August 18, 2019.

Chernyshov PV, Tomas-Aragones L, Manolache L, et al; EADV Quality of Life Task Force. Quality of life measurement in atopic dermatitis. Position paper of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV) Task Force on quality of life. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:576-593. - Hill MK, Kheirandish Pishkenari A, Braunberger TL, et al. Recent trends in disease severity and quality of life instruments for patients with atopic dermatitis: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:906-917.

- Basra MK, Sue-Ho R, Finlay AY. The Family Dermatology Life Quality Index: measuring the secondary impact of skin disease. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:528-538.

- Dodington SR, Basra MK, Finlay AY, et al. The Dermatitis Family Impact questionnaire: a review of its measurement properties and clinical application. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:31-46.

- Lewis-Jones MS, Finlay AY, Dykes PJ. The Infants’ Dermatitis Quality of Life Index. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:104-110.

- Holme SA, Man I, Sharpe JL, et al. The Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index: validation of the cartoon version. Br J Dermatol. 2003;148:285-290.

- Whalley D, McKenna SP, Dewar AL, et al. A new instrument for assessing quality of life in atopic dermatitis: international development of the Quality of Life Index for Atopic Dermatitis (QoLIAD). Br J Dermatol. 2004;150:274-283.

- Jeon C, Yan D, Nakamura M, et al. Frequency and management of sleep disturbance in adults with atopic dermatitis: a systematic review. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2017;7:349-364.

- Yu SH, Attarian H, Zee P, et al. Burden of sleep and fatigue in US adults with atopic dermatitis. Dermatitis. 2016;27:50-58.

- Kong TS, Han TY, Lee JH, et al. Correlation between severity of atopic dermatitis and sleep quality in children and adults. Ann Dermatol. 2016;28:321-326.

- Fishbein AB, Mueller K, Kruse L, et al. Sleep disturbance in children with moderate/severe atopic dermatitis: a case-control study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:336-341.

- Chamlin SL, Mattson CL, Frieden IJ, et al. The price of pruritus: sleep disturbance and cosleeping in atopic dermatitis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:745-750.

- Emerson RM, Williams HC, Allen BR. What is the cost of atopic dermatitis in preschool children? Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:514-522.

- Filanovsky MG, Pootongkam S, Tamburro JE, et al. The financial and emotional impact of atopic dermatitis on children and their families. J Pediatr. 2016;169:284-290.

- Fivenson D, Arnold RJ, Kaniecki DJ, et al. The effect of atopic dermatitis on total burden of illness and quality of life on adults and children in a large managed care organization. J Manag Care Pharm. 2002;8:333-342.

- Carroll CL, Balkrishnan R, Feldman SR, et al. The burden of atopic dermatitis: impact on the patient, family, and society. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:192-199.

- Drucker AM, Wang AR, Qureshi AA. Research gaps in quality of life and economic burden of atopic dermatitis: the National Eczema Association Burden of Disease Audit. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:873-874.

- Nørreslet LB, Ebbehøj NE, Ellekilde Bonde JP, et al. The impact of atopic dermatitis on work life—a systematic review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:23-38.

- Su JC, Kemp AS, Varigos GA, et al. Atopic eczema: its impact on the family and financial cost. Arch Dis Child. 1997;76:159-162.

- Coutanceau C, Stalder JF. Analysis of correlations between patient-oriented SCORAD (PO-SCORAD) and other assessment scores of atopic dermatitis severity and quality of life. Dermatology. 2014;229:248-255.

- Ben-Gashir MA, Seed PT, Hay RJ. Quality of life and disease severity are correlated in children with atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2004;150:284-290.

- van Valburg RW, Willemsen MG, Dirven-Meijer PC, et al. Quality of life measurement and its relationship to disease severity in children with atopic dermatitis in general practice. Acta Derm Venereol. 2011;91:147-151.

- Haeck IM, ten Berge O, van Velsen SG, et al. Moderate correlation between quality of life and disease activity in adult patients with atopic dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:236-241.

- Spuls PI, Gerbens LAA, Simpson E, et al; HOME initiative collaborators. Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM), a core instrument to measure symptoms in clinical trials: a Harmonising Outcome Measures for Eczema (HOME) statement. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:979-984.

- Schmitt J, Spuls PI, Thomas KS, et al; HOME initiative collaborators. The Harmonising Outcome Measures for Eczema (HOME) statement to assess clinical signs of atopic eczema in trials. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134:800-807.

- Oh SH, Bae BG, Park CO, et al. Association of stress with symptoms of atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2010;90:582-588.

- Hay RJ, Johns NE, Williams HC, et al. The global burden of skin disease in 2010: an analysis of the prevalence and impact of skin conditions. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:1527-1534.

- Dalgard FJ, Gieler U, Tomas-Aragones L, et al. The psychological burden of skin diseases: a cross-sectional multicenter study among dermatological out-patients in 13 European countries. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:984-991.

- Cheng CM, Hsu JW, Huang KL, et al. Risk of developing major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders among adolescents and adults with atopic dermatitis: a nationwide longitudinal study. J Affect Disord. 2015;178:60-65.

Halvorsen JA, Lien L, Dalgard F, et al. Suicidal ideation, mental health problems, and social function in adolescents with eczema: a population-based study. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:1847-1854. - Linnet J, Jemec GB. An assessment of anxiety and dermatology life quality in patients with atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:268-272.

- Ring J, Alomar A, Bieber T, et al; European Dermatology Forum; European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology; European Task Force on Atopic Dermatitis; European Federation of Allergy; European Society of Pediatric Dermatology; Global Allergy and Asthma European Network. Guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) Part II. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:1176-1193.

- Perczel K, Gál J. Hypnotherapy of atopic dermatitis in an adult. case report. Orv Hetil. 2016;157:111-115.

Practice Points

- For assessing quality of life (QOL) in atopic dermatitis (AD), it is recommended that researchers use a combination of a generic and a dermatology-specific or AD-specific instrument, whereas clinicians should apply a dermatology-specific or an AD-specific method or both.

- Anxiety and depression are common comorbidities in AD; patients also may need psychological support.

- Patient education is key for improving QOL in AD.

- Financial aspects of the treatment of AD should be taken into consideration because AD requires constant care, which puts a financial burden on patients.