User login

Homelessness is associated with disproportionate medical morbidity and mortality and use of nonpreventive health services.1 In fiscal year 2010, veterans experiencing homelessness were 4 times more likely to use VA emergency departments and had a greater 10-year mortality risk than did veterans who were housed.1 Veterans experiencing homelessness were more likely to be diagnosed with substance use disorder, schizophrenia, liver disease, and/or HIV/AIDS than were their housed counterparts.

Ending veteran homelessness is a federal priority, exemplified by the goal of President Obama to end veteran homelessness by 2015.2 Since the goal’s articulation, veteran homelessness has declined nationally by 33% (24,117 veterans) from 2009 to 2014 however, 49,933 veterans were identified as being homeless on a given night in January 2014.3

Related: Landmark Initiative Signed for Homeless Veterans

A crucial element needed to end veteran homelessness is veteran and health care provider knowledge of existing homeless services and mechanisms of access. In 2012, VHA launched a homelessness screening clinical reminder in the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS), which prompts a discussion of housing status between the veteran and provider.4 The staff of the VA North Texas Health Care System (VANTHCS) Comprehensive Homeless Center Programs (CHCP) realized that homeless housing programs at the facility could be more accessible if staff from each program could screen for all available programs and if a single phone number existed for scheduling appointments. Therefore, VANTHCS transformed its homeless housing screening process to a standardized process through which veterans are screened for all CHCP housing programs during a single screening assessment, Universal Homeless Housing Screening (UHHS).

This article describes the creation of the UHHS, the screening tool, 3-month postimplementation findings, and recommendations based on initial VANTHCS staff experiences with this process. During the redesign of screening process for homeless housing, VANTHCS staff found a paucity of guidance regarding best practices. This article attempts to fill this gap and provide guidance to institutions that are considering standardizing their screening process for homeless housing across multiple programs at different locations.

Background

Established in 1990, VANTHCS CHCP is VA’ s first comprehensive homeless center. The CHCP provides both housing and vocational rehabilitation programs, including 13 housing programs in 6 different cities and long-standing partnerships between CHCP and 3 community agencies whose programs have specific housing for veterans.5 Screenings performed in Dallas, Texas, for CHCP housing programs are completed at 4 separate locations.

Prior to the inception of the UHHS process, access to housing programs was limited by veteran awareness of the programs and transportation to various program locations. To participate in these programs, veterans needed to complete a form for the VA Northeast Program Evaluation Center (NEPEC), which staff at the Healthcare for Homeless Veterans (HCHV) CHCP program could administer. This process created an admission bottleneck, because HCHV staff needed to evaluate veterans even if they were being admitted to non-HCHV programs.

UHHS Creation Process

In 2011, NEPEC launched the electronic Homeless Operations Management and Evaluation System (HOMES) to replace paper-based reporting.6 This tool allowed non-HCHV CHCP staff to complete NEPEC evaluation and allowed CHCP to meet its goal of designing a system where all CHCP housing programs could complete a screening assessment. This goal originated from the desire of then CHCP Director Teresa House-Hatfield to create a more efficient housing screening process and from similar feedback from veterans.

Furthermore, in 2009, then Secretary of Veterans Affairs Eric K. Shinseki described a “no wrong door” philosophy for ending veteran homelessness, which CHCP operationalized by screening veterans for any CHCP housing program regardless of initial point of contact within the CHCP system.2 Subsequently, in 2010, the VA Office of Mental Health Services contracted with Mathematica Policy Research, Inc., to conduct a quality review of VA Mental Health Residential Rehabilitation Treatment Programs. Notable among their recommendations was to create a one-stop screening process for these programs.

Related: Primary Care Medical Services for Homeless Veterans

In 2010, CHCP embarked on a process to transform the facility’s screening procedure to a one-stop assessment with standardized screening questions and create a systematic process to track outcomes across all CHCP housing programs. The new process allowed for a standardized appeal procedure when eligibility for a program was not met. It also improved the ease of communication by having 1 phone number for making appointments or informing about screening times. These changes were enacted without the addition of any new staff positions. Instead, in October 2011, Ms. House-Hatfield tasked Dina Hooshyar of the VANTHCS to champion and spearhead this transformation.

The challenge associated with the UHHS creation process was to balance individual program autonomy with standardized processes. This balance was achieved through weekly calls where Ms. House- Hatfield, Dr. Hooshyar, and CHCP program managers discussed how to design UHHS. The management of the CHCP also actively sought input from CHCP frontline staff. During the preimplementation phase, Dr. Hooshyar gave multiple UHHS trainings to CHCP staff who would become involved in UHHS process, another feedback mechanism.

Program managers retained their programs’ autonomy by picking screeners and the number of employees in that position for their program, screening location and time, and screening type (appointment, walk-in, telephone, and/or combination). Managers and staff also assisted in the creation of the UHHS tool by providing their program’s eligibility criteria and customary psychosocial assessment questions. The UHHS tool not only brought consistency to the screening process, but also removed any perceived biases by asking all veterans the same questions across all UHHS screening locations. Implemented on August 26, 2013, UHHS continues to be used.

UHHS Screening Tool

The UHHS tool is an assessment composed of 4 sections: (1) History; (2) Decision Tree; (3) Specific Program Eligibility Criteria; and (4) Plan. The sections exist as templates in the CPRS.

The History section asks about demographic information, diagnoses, alcohol and illicit drug use history, dependent status, outstanding legal issues, housing status, functional limitations, income and employment status, and potential benefit from and interest in psychosocial rehabilitation and care management. If the veteran would not benefit from and/or is not interested in participating in psychosocial rehabilitation and care management, the screener concludes the assessment, as these factors are eligibility requirements for all CHCP programs. Veterans can appeal their case to the screener’s program manager.

The Decision Tree template consists of 6 core eligibility criteria across programs that can serve to narrow the list of eligible programs: (1) Is the veteran currently homeless; (2) Has the veteran been homeless continuously for ≥ 1 year, or has the veteran had ≥ 4 separate occasions of homelessness in the past 3 years; (3) Does the veteran have a mental health or substance use diagnosis; (4) Can the veteran pay a program fee (9 of 16 UHHS-associated programs have no fees); (5) Is the veteran capable of self-administering medications; and (6) Can the veteran perform activities of daily living and does not need acute hospitalization?

Related: Using H-PACT to Overcome Treatment Obstacles for Homeless Veterans (audio)

Veterans are then asked in which town(s) they want to reside. The questions for the Specific Program Eligibility Criteria section are asked only for those programs for which the veteran is found to be tentatively eligible by the Decision Tree and has interest in participating.

The Plan section gives veterans the opportunity to appeal a UHHS finding to the specific program’s manager whose program they are not eligible to participate. Veterans also rank their preference for the programs for which they are interested and eligible. A shared folder contains all program census information. Through the screening tool, veterans devise a plan to contact the potential admitting program. Veterans are informed about the importance of keeping in contact with these programs, because programs will not hold openings for an indefinite time.

Completion of this screening assessment, which includes HOMES and the UHHS tool, generally takes 1.5 hours. After a veteran undergoes this assessment, a preadmission appointment is made with the first open program for which they are eligible and interested in participating. The main goal of this appointment varies by program, such as finalizing referral processes with associated community partners, performing a preliminary medical clearance, determining whether veterans have already used their program’s maximum allotted time, coordinating a Therapeutic Supported Employment Services assessment, or obtaining the required documents from veterans. If at the preadmission appointment, either the veteran declines participation or the program declines admittance, the veteran can follow up with other programs for which they met eligibility criteria and were interested in participating during the initial UHHS assessment instead of undergoing another housing screening.

Notification of Screening Results

The CHCP staff member who performs the screening is responsible for documenting the veteran’s name, phone number or means of contact, current residence, and housing outcome in a secure shared Microsoft Excel document called Housing Outcome. The Excel IF and VLOOKUP function link the original document to each program’s acceptance and petition documents. This linkage auto populates information entered in the Housing Outcome document to each program’s acceptance and petition documents if the veteran has a housing outcome associated with the program. CHCP staff members then look at their individual program’s acceptance and/or petition documents to see the list of veterans who have a housing outcome involving their program instead of having to sort through the Housing Outcome document. As a backup to the Housing Outcome document, screeners add the point of contact for the programs that the veteran had an associated housing outcome as additional signers to their CPRS screening note.

When UHHS was first implemented, the screeners had a daily call to discuss the screened veterans’ housing outcomes and screener experiences with the new system. Dr. Hooshyar also participated in this call as a means to answer screener questions and to get feedback. Within a month of UHHS implementation, these calls were cancelled, because the screeners felt comfortable with the UHHS process and the majority of housing programs were operating at full capacity.

UHHS Appointment Line

The UHHS appointment phone number uses an automatic call distributor, a call-center technology. Thus, 1 phone number can be answered by multiple people working in separate locations. The challenge was how to connect phones associated with offices located offsite from the VANTHCS campus. The solution was to use Internet phones in addition to existing staff phones.

Results

During the review period from August 26, 2013, to November 27, 2013 (65 workdays), 392 unique veterans attended a UHHS assessment. Four veterans who were screened twice were included only once in the analysis; outcomes from only their initial screenings were evaluated. Three hundred fifty-six veterans completed a UHHS assessment; 36 had an assessment but did not complete it. Rates of veterans not presenting for their scheduled appointments increased over time, from 24% in August 2013 to 50% in November 2013. To address the no-show rate, program managers decreased the number of offered scheduled appointments and increased the number of walk-in visits. Overall, the schedule distribution consisted of about twice as much time allotted for walk-in appointments compared with scheduled appointments. The UHHS appointment line received 873 calls, where the number decreased over time.

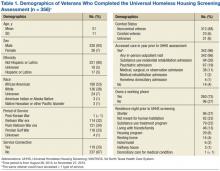

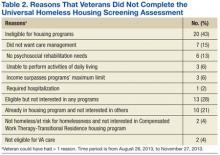

The typical screened veteran who completed a UHHS assessment was a non-Hispanic, African American male aged 51 years with no service connection or history of combat who served either in the Vietnam War era, post-Vietnam War era, or Persian Gulf War. He had accessed VANTHCS care in the year prior to screening; owned a working phone; and was staying in a shelter, a place not meant for human habitation, or a substance use treatment program the night prior to screening (Table 1). Only 20 veterans (5%) were ineligible for participation in all programs, because they did not meet core eligibility criteria as defined by the UHHS Decision Tree, their income surpassed the program limit, or they were not eligible for VA care (Table 2).

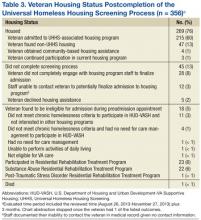

To determine the housing outcome of the veterans screened during the reviewed period, a 3-month follow-up from the end of the review period was used. During this time, 269 veterans (76%) who completed the UHHS process were housed, with 215 (60%) veterans housed in a UHHS-associated housing program (Table 3). Of the veterans who completed a UHHS assessment, 45 veterans (13%) did not complete the screening process; admitting program staff documented in CPRS unsuccessful attempts at reaching 12 veterans (3%), among whom 4 had no working phone at the time of their UHHS assessment. Time to admission depended on the program mission, openings, and the veteran’s UHHS engagement. Admission date indicates the date that programs housed veterans except in the case of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development-VA Supportive Housing (HUD-VASH), where admission date indicates the date the veteran gave all required documents to HUD-VASH staff.

Discussion

Prior to the inception of UHHS, the staff of the CHCP housing program did not have a standardized process for communication across programs about veterans’ housing status and outcomes. Veterans went to multiple locations for screening if they were interested in > 1 program or if they were not admitted to the first program they approached. The UHHS process improved communication across CHCP housing programs, resulting in increased veteran accessibility to these programs as suggested by 3 CHCP housing programs having fewer days with openings post-UHHS implementation. Furthermore, a new screener position did not need to be created, because existing CHCP social workers were all capable screeners due to process standardization.

Fifty-five percent of the screened veterans were interested in and eligible for participation in > 1 housing program. They were eligible for 3 programs on average and were usually admitted to the housing program with the earliest opening. The need for screenings across all the CHCP housing programs was potentially decreased by ≥ one-third. This increased available time for the screeners to accomplish their other clinical responsibilities.

Limitations

A limitation of the review period evaluation is little information on noncompleters. The available data are confined to information documented in CPRS regarding why 45 veterans (13% of those who completed UHHS assessment) did not complete the screening process. For 12, admitting staff of the housing program documented in CPRS that they had been unable to reach the veteran; 9 of these veterans attended subsequent non-UHHS VANTHCS visits. To further improve the homeless housing delivery service, the creation of a CPRS-related process that informs VA clinicians that a housing program is attempting to contact a veteran is needed.

Challenges and Recommendations

Because the Housing Outcome document is a shared document, only 1 person at a time can save information in it. Facility staff have been unable to create a simple macro that closes the document automatically. Instead, screeners who need to save information when a document is already opened elsewhere must use a group e-mail list to alert others to close the document.

Streamlining the communication channel between the screeners and management evolved from the daily call, to e-mailing and program managers discussing topics with their staff, to Dr. Hooshyar facilitating a weekly call for screeners and program managers.

Optimizing the ratio of walk-in to scheduled appointments took time. Prior to the UHHS process, some CHCP housing programs offered scheduled appointments, whereas others had walk-in appointments. The decision to offer in-person scheduled appointments for veterans who preferred scheduled appointments or who commuted from a distance was made. Universal Homeless Housing Screening staff also offered scheduled telephone appointments for veterans who lacked transportation.

At times, admitting program staff was unable to reach veterans eligible for and interested in their program, despite screeners recommending to veterans that they should provide these programs with any changes in their contact information.

Recommendations for designing a screening process for homeless housing include:

- Have periodic retreats instead of weekly conference calls to quicken the pre-implementation process.

- Start with a pilot that includes some potential screeners to test the implementation process. The screeners involved in the pilot would train future screeners to expand the screener pool.

- Invest time in electronic tracking tools despite upfront and maintenance time requirements.

- Offer more walk-in than scheduled screening appointments.

- Embrace the idea that the pro-cess is always under development.

Conclusion

To ameliorate anxiety associated with changing the system, UHHS- associated staff redesigned the housing screening process through openness to stakeholder feedback and building on consensus. The staff also nurtured a culture that could change newly revised processes, depending on quality assurance findings. Without this method, the unknown likely would have propagated continued status quo. Universal Homeless Housing Screening processes improved veteran access to CHCP housing programs through instituting a one-stop housing screening assessment that also reduced the potential number of screenings by ≥ one-third.

Acknowledgments

The authors greatly appreciate the input of the many people involved in the creation of the UHHS process, in particular Daniel Anderson, Heather Arredondo, Tara Ayala, TiieShaiyon Banton, Melody Boyet, Amelia Bradley, Timothy Brown, Carnisha Campbell, Donald Capps, Burnell Carden Jr, Pushpi Chaudhary, Howard Cunningham, Rachael David, Marianna Demko, Derrick Evans, Steven Fisher, Kimberly Fite, Fatina Ford, Christi Godfrey, Gerald Goodwin, Melvin Haley, Tony Hall, Jessica Hennessey, Teresa House-Hatfield, Don Hubbard, Kathryn Jacob, Tonja King, Cecelia Knight, Janine Lenger-Gvist, Vickie Linden, Julia Long, Kristin Manley, Peggy Martin, Treva McDaniel, William McNair, Tammy Miller, Jeffery Milligan, Anhloan Nguyen, Tywanna Nichols, Cheryl Paul, Catherine Orsak, Dustin Perkins, Claudette Phillips, Joan Prescott, John Purkey, Martin Roback, Catriska Robertson, Charles Ross, Shanna Ruppert, Stephanie Saldivar, Linda Saucedo, Inga Sinclair-Henderson, John Smith, Zaire Smith, Cheryl Stringer, Valetta Ward, Carolyn Washington, Tammra Wood, and Skylar Woods-Nunley. They would also like to thank the veterans for their service and feedback.

Author disclosures

Dr. North discloses research support from National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, and VA and consultant fees from the University of Missouri-Columbia. Dr. Surís is Local Site Investigator for VA CSP #589 VIPSTAR-Veterans Individual Placement and Support Towards Advancing Recovery (PI Lori Davis, MD). She is co- investigator for VISN 17 grant Association of Myocardial Viability to Symptom Improvement post-CTO PCI (PI-Shuaib Abdullah, MD) and co-investigator for National Institutes on Drug Abuse grant Lidocaine Infusion as a Treatment for Cocaine Relapse and Craving (PI-Bryon Adinoff, MD). In addition, Dr. Surís is co-site-PI for the upcoming VA CSP #590 Lithium for Suicidal Behavior in Mood Disorders.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

1. Tsai J, Doran KM, Rosenheck RA. When health insurance is not a factor: National comparison of homeless and nonhomeless US veterans who use Veterans Affairs emergency departments. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(suppl 2):S225-S231.

2. Secretary Shinseki Details Plan to End Homelessness for Veterans [news release]. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs: Office of Public and Intergovernmental Affairs. http://www.va.gov/opa/pressrel/pressrelease.cfm?id=1807. Published November 3, 2009. Accessed March 3, 2014.

3. U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development: Office of Community Planning and Development. The 2014 Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress. Part 1 Point-In-Time Estimates of Homelessness. https://www.hudexchange.info/resources/documents /2014-AHAR-Part1.pdf. Published October 2014. Accessed March 18, 2015.

4. Montgomery AE, Fargo JD, Byrne TH, Kane VR, Culhane DP. Universal screening for homelessness and risk for homelessness in the Veterans Health Administration. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(suppl 2):S210-S211.

5. Berman S, Barilich JE, Rosenheck R, Koerber G. The VA’s first comprehensive homeless center: A catalyst for public and private partnerships. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1993;44(12):1183-1184.

6. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Homeless Operations Management and Evaluation System (HOMES) User Manual–Phase 1. http://www.vfwsc.org/homes.pdf. Published April 19, 2011. Accessed March 3, 2014.

Homelessness is associated with disproportionate medical morbidity and mortality and use of nonpreventive health services.1 In fiscal year 2010, veterans experiencing homelessness were 4 times more likely to use VA emergency departments and had a greater 10-year mortality risk than did veterans who were housed.1 Veterans experiencing homelessness were more likely to be diagnosed with substance use disorder, schizophrenia, liver disease, and/or HIV/AIDS than were their housed counterparts.

Ending veteran homelessness is a federal priority, exemplified by the goal of President Obama to end veteran homelessness by 2015.2 Since the goal’s articulation, veteran homelessness has declined nationally by 33% (24,117 veterans) from 2009 to 2014 however, 49,933 veterans were identified as being homeless on a given night in January 2014.3

Related: Landmark Initiative Signed for Homeless Veterans

A crucial element needed to end veteran homelessness is veteran and health care provider knowledge of existing homeless services and mechanisms of access. In 2012, VHA launched a homelessness screening clinical reminder in the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS), which prompts a discussion of housing status between the veteran and provider.4 The staff of the VA North Texas Health Care System (VANTHCS) Comprehensive Homeless Center Programs (CHCP) realized that homeless housing programs at the facility could be more accessible if staff from each program could screen for all available programs and if a single phone number existed for scheduling appointments. Therefore, VANTHCS transformed its homeless housing screening process to a standardized process through which veterans are screened for all CHCP housing programs during a single screening assessment, Universal Homeless Housing Screening (UHHS).

This article describes the creation of the UHHS, the screening tool, 3-month postimplementation findings, and recommendations based on initial VANTHCS staff experiences with this process. During the redesign of screening process for homeless housing, VANTHCS staff found a paucity of guidance regarding best practices. This article attempts to fill this gap and provide guidance to institutions that are considering standardizing their screening process for homeless housing across multiple programs at different locations.

Background

Established in 1990, VANTHCS CHCP is VA’ s first comprehensive homeless center. The CHCP provides both housing and vocational rehabilitation programs, including 13 housing programs in 6 different cities and long-standing partnerships between CHCP and 3 community agencies whose programs have specific housing for veterans.5 Screenings performed in Dallas, Texas, for CHCP housing programs are completed at 4 separate locations.

Prior to the inception of the UHHS process, access to housing programs was limited by veteran awareness of the programs and transportation to various program locations. To participate in these programs, veterans needed to complete a form for the VA Northeast Program Evaluation Center (NEPEC), which staff at the Healthcare for Homeless Veterans (HCHV) CHCP program could administer. This process created an admission bottleneck, because HCHV staff needed to evaluate veterans even if they were being admitted to non-HCHV programs.

UHHS Creation Process

In 2011, NEPEC launched the electronic Homeless Operations Management and Evaluation System (HOMES) to replace paper-based reporting.6 This tool allowed non-HCHV CHCP staff to complete NEPEC evaluation and allowed CHCP to meet its goal of designing a system where all CHCP housing programs could complete a screening assessment. This goal originated from the desire of then CHCP Director Teresa House-Hatfield to create a more efficient housing screening process and from similar feedback from veterans.

Furthermore, in 2009, then Secretary of Veterans Affairs Eric K. Shinseki described a “no wrong door” philosophy for ending veteran homelessness, which CHCP operationalized by screening veterans for any CHCP housing program regardless of initial point of contact within the CHCP system.2 Subsequently, in 2010, the VA Office of Mental Health Services contracted with Mathematica Policy Research, Inc., to conduct a quality review of VA Mental Health Residential Rehabilitation Treatment Programs. Notable among their recommendations was to create a one-stop screening process for these programs.

Related: Primary Care Medical Services for Homeless Veterans

In 2010, CHCP embarked on a process to transform the facility’s screening procedure to a one-stop assessment with standardized screening questions and create a systematic process to track outcomes across all CHCP housing programs. The new process allowed for a standardized appeal procedure when eligibility for a program was not met. It also improved the ease of communication by having 1 phone number for making appointments or informing about screening times. These changes were enacted without the addition of any new staff positions. Instead, in October 2011, Ms. House-Hatfield tasked Dina Hooshyar of the VANTHCS to champion and spearhead this transformation.

The challenge associated with the UHHS creation process was to balance individual program autonomy with standardized processes. This balance was achieved through weekly calls where Ms. House- Hatfield, Dr. Hooshyar, and CHCP program managers discussed how to design UHHS. The management of the CHCP also actively sought input from CHCP frontline staff. During the preimplementation phase, Dr. Hooshyar gave multiple UHHS trainings to CHCP staff who would become involved in UHHS process, another feedback mechanism.

Program managers retained their programs’ autonomy by picking screeners and the number of employees in that position for their program, screening location and time, and screening type (appointment, walk-in, telephone, and/or combination). Managers and staff also assisted in the creation of the UHHS tool by providing their program’s eligibility criteria and customary psychosocial assessment questions. The UHHS tool not only brought consistency to the screening process, but also removed any perceived biases by asking all veterans the same questions across all UHHS screening locations. Implemented on August 26, 2013, UHHS continues to be used.

UHHS Screening Tool

The UHHS tool is an assessment composed of 4 sections: (1) History; (2) Decision Tree; (3) Specific Program Eligibility Criteria; and (4) Plan. The sections exist as templates in the CPRS.

The History section asks about demographic information, diagnoses, alcohol and illicit drug use history, dependent status, outstanding legal issues, housing status, functional limitations, income and employment status, and potential benefit from and interest in psychosocial rehabilitation and care management. If the veteran would not benefit from and/or is not interested in participating in psychosocial rehabilitation and care management, the screener concludes the assessment, as these factors are eligibility requirements for all CHCP programs. Veterans can appeal their case to the screener’s program manager.

The Decision Tree template consists of 6 core eligibility criteria across programs that can serve to narrow the list of eligible programs: (1) Is the veteran currently homeless; (2) Has the veteran been homeless continuously for ≥ 1 year, or has the veteran had ≥ 4 separate occasions of homelessness in the past 3 years; (3) Does the veteran have a mental health or substance use diagnosis; (4) Can the veteran pay a program fee (9 of 16 UHHS-associated programs have no fees); (5) Is the veteran capable of self-administering medications; and (6) Can the veteran perform activities of daily living and does not need acute hospitalization?

Related: Using H-PACT to Overcome Treatment Obstacles for Homeless Veterans (audio)

Veterans are then asked in which town(s) they want to reside. The questions for the Specific Program Eligibility Criteria section are asked only for those programs for which the veteran is found to be tentatively eligible by the Decision Tree and has interest in participating.

The Plan section gives veterans the opportunity to appeal a UHHS finding to the specific program’s manager whose program they are not eligible to participate. Veterans also rank their preference for the programs for which they are interested and eligible. A shared folder contains all program census information. Through the screening tool, veterans devise a plan to contact the potential admitting program. Veterans are informed about the importance of keeping in contact with these programs, because programs will not hold openings for an indefinite time.

Completion of this screening assessment, which includes HOMES and the UHHS tool, generally takes 1.5 hours. After a veteran undergoes this assessment, a preadmission appointment is made with the first open program for which they are eligible and interested in participating. The main goal of this appointment varies by program, such as finalizing referral processes with associated community partners, performing a preliminary medical clearance, determining whether veterans have already used their program’s maximum allotted time, coordinating a Therapeutic Supported Employment Services assessment, or obtaining the required documents from veterans. If at the preadmission appointment, either the veteran declines participation or the program declines admittance, the veteran can follow up with other programs for which they met eligibility criteria and were interested in participating during the initial UHHS assessment instead of undergoing another housing screening.

Notification of Screening Results

The CHCP staff member who performs the screening is responsible for documenting the veteran’s name, phone number or means of contact, current residence, and housing outcome in a secure shared Microsoft Excel document called Housing Outcome. The Excel IF and VLOOKUP function link the original document to each program’s acceptance and petition documents. This linkage auto populates information entered in the Housing Outcome document to each program’s acceptance and petition documents if the veteran has a housing outcome associated with the program. CHCP staff members then look at their individual program’s acceptance and/or petition documents to see the list of veterans who have a housing outcome involving their program instead of having to sort through the Housing Outcome document. As a backup to the Housing Outcome document, screeners add the point of contact for the programs that the veteran had an associated housing outcome as additional signers to their CPRS screening note.

When UHHS was first implemented, the screeners had a daily call to discuss the screened veterans’ housing outcomes and screener experiences with the new system. Dr. Hooshyar also participated in this call as a means to answer screener questions and to get feedback. Within a month of UHHS implementation, these calls were cancelled, because the screeners felt comfortable with the UHHS process and the majority of housing programs were operating at full capacity.

UHHS Appointment Line

The UHHS appointment phone number uses an automatic call distributor, a call-center technology. Thus, 1 phone number can be answered by multiple people working in separate locations. The challenge was how to connect phones associated with offices located offsite from the VANTHCS campus. The solution was to use Internet phones in addition to existing staff phones.

Results

During the review period from August 26, 2013, to November 27, 2013 (65 workdays), 392 unique veterans attended a UHHS assessment. Four veterans who were screened twice were included only once in the analysis; outcomes from only their initial screenings were evaluated. Three hundred fifty-six veterans completed a UHHS assessment; 36 had an assessment but did not complete it. Rates of veterans not presenting for their scheduled appointments increased over time, from 24% in August 2013 to 50% in November 2013. To address the no-show rate, program managers decreased the number of offered scheduled appointments and increased the number of walk-in visits. Overall, the schedule distribution consisted of about twice as much time allotted for walk-in appointments compared with scheduled appointments. The UHHS appointment line received 873 calls, where the number decreased over time.

The typical screened veteran who completed a UHHS assessment was a non-Hispanic, African American male aged 51 years with no service connection or history of combat who served either in the Vietnam War era, post-Vietnam War era, or Persian Gulf War. He had accessed VANTHCS care in the year prior to screening; owned a working phone; and was staying in a shelter, a place not meant for human habitation, or a substance use treatment program the night prior to screening (Table 1). Only 20 veterans (5%) were ineligible for participation in all programs, because they did not meet core eligibility criteria as defined by the UHHS Decision Tree, their income surpassed the program limit, or they were not eligible for VA care (Table 2).

To determine the housing outcome of the veterans screened during the reviewed period, a 3-month follow-up from the end of the review period was used. During this time, 269 veterans (76%) who completed the UHHS process were housed, with 215 (60%) veterans housed in a UHHS-associated housing program (Table 3). Of the veterans who completed a UHHS assessment, 45 veterans (13%) did not complete the screening process; admitting program staff documented in CPRS unsuccessful attempts at reaching 12 veterans (3%), among whom 4 had no working phone at the time of their UHHS assessment. Time to admission depended on the program mission, openings, and the veteran’s UHHS engagement. Admission date indicates the date that programs housed veterans except in the case of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development-VA Supportive Housing (HUD-VASH), where admission date indicates the date the veteran gave all required documents to HUD-VASH staff.

Discussion

Prior to the inception of UHHS, the staff of the CHCP housing program did not have a standardized process for communication across programs about veterans’ housing status and outcomes. Veterans went to multiple locations for screening if they were interested in > 1 program or if they were not admitted to the first program they approached. The UHHS process improved communication across CHCP housing programs, resulting in increased veteran accessibility to these programs as suggested by 3 CHCP housing programs having fewer days with openings post-UHHS implementation. Furthermore, a new screener position did not need to be created, because existing CHCP social workers were all capable screeners due to process standardization.

Fifty-five percent of the screened veterans were interested in and eligible for participation in > 1 housing program. They were eligible for 3 programs on average and were usually admitted to the housing program with the earliest opening. The need for screenings across all the CHCP housing programs was potentially decreased by ≥ one-third. This increased available time for the screeners to accomplish their other clinical responsibilities.

Limitations

A limitation of the review period evaluation is little information on noncompleters. The available data are confined to information documented in CPRS regarding why 45 veterans (13% of those who completed UHHS assessment) did not complete the screening process. For 12, admitting staff of the housing program documented in CPRS that they had been unable to reach the veteran; 9 of these veterans attended subsequent non-UHHS VANTHCS visits. To further improve the homeless housing delivery service, the creation of a CPRS-related process that informs VA clinicians that a housing program is attempting to contact a veteran is needed.

Challenges and Recommendations

Because the Housing Outcome document is a shared document, only 1 person at a time can save information in it. Facility staff have been unable to create a simple macro that closes the document automatically. Instead, screeners who need to save information when a document is already opened elsewhere must use a group e-mail list to alert others to close the document.

Streamlining the communication channel between the screeners and management evolved from the daily call, to e-mailing and program managers discussing topics with their staff, to Dr. Hooshyar facilitating a weekly call for screeners and program managers.

Optimizing the ratio of walk-in to scheduled appointments took time. Prior to the UHHS process, some CHCP housing programs offered scheduled appointments, whereas others had walk-in appointments. The decision to offer in-person scheduled appointments for veterans who preferred scheduled appointments or who commuted from a distance was made. Universal Homeless Housing Screening staff also offered scheduled telephone appointments for veterans who lacked transportation.

At times, admitting program staff was unable to reach veterans eligible for and interested in their program, despite screeners recommending to veterans that they should provide these programs with any changes in their contact information.

Recommendations for designing a screening process for homeless housing include:

- Have periodic retreats instead of weekly conference calls to quicken the pre-implementation process.

- Start with a pilot that includes some potential screeners to test the implementation process. The screeners involved in the pilot would train future screeners to expand the screener pool.

- Invest time in electronic tracking tools despite upfront and maintenance time requirements.

- Offer more walk-in than scheduled screening appointments.

- Embrace the idea that the pro-cess is always under development.

Conclusion

To ameliorate anxiety associated with changing the system, UHHS- associated staff redesigned the housing screening process through openness to stakeholder feedback and building on consensus. The staff also nurtured a culture that could change newly revised processes, depending on quality assurance findings. Without this method, the unknown likely would have propagated continued status quo. Universal Homeless Housing Screening processes improved veteran access to CHCP housing programs through instituting a one-stop housing screening assessment that also reduced the potential number of screenings by ≥ one-third.

Acknowledgments

The authors greatly appreciate the input of the many people involved in the creation of the UHHS process, in particular Daniel Anderson, Heather Arredondo, Tara Ayala, TiieShaiyon Banton, Melody Boyet, Amelia Bradley, Timothy Brown, Carnisha Campbell, Donald Capps, Burnell Carden Jr, Pushpi Chaudhary, Howard Cunningham, Rachael David, Marianna Demko, Derrick Evans, Steven Fisher, Kimberly Fite, Fatina Ford, Christi Godfrey, Gerald Goodwin, Melvin Haley, Tony Hall, Jessica Hennessey, Teresa House-Hatfield, Don Hubbard, Kathryn Jacob, Tonja King, Cecelia Knight, Janine Lenger-Gvist, Vickie Linden, Julia Long, Kristin Manley, Peggy Martin, Treva McDaniel, William McNair, Tammy Miller, Jeffery Milligan, Anhloan Nguyen, Tywanna Nichols, Cheryl Paul, Catherine Orsak, Dustin Perkins, Claudette Phillips, Joan Prescott, John Purkey, Martin Roback, Catriska Robertson, Charles Ross, Shanna Ruppert, Stephanie Saldivar, Linda Saucedo, Inga Sinclair-Henderson, John Smith, Zaire Smith, Cheryl Stringer, Valetta Ward, Carolyn Washington, Tammra Wood, and Skylar Woods-Nunley. They would also like to thank the veterans for their service and feedback.

Author disclosures

Dr. North discloses research support from National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, and VA and consultant fees from the University of Missouri-Columbia. Dr. Surís is Local Site Investigator for VA CSP #589 VIPSTAR-Veterans Individual Placement and Support Towards Advancing Recovery (PI Lori Davis, MD). She is co- investigator for VISN 17 grant Association of Myocardial Viability to Symptom Improvement post-CTO PCI (PI-Shuaib Abdullah, MD) and co-investigator for National Institutes on Drug Abuse grant Lidocaine Infusion as a Treatment for Cocaine Relapse and Craving (PI-Bryon Adinoff, MD). In addition, Dr. Surís is co-site-PI for the upcoming VA CSP #590 Lithium for Suicidal Behavior in Mood Disorders.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

Homelessness is associated with disproportionate medical morbidity and mortality and use of nonpreventive health services.1 In fiscal year 2010, veterans experiencing homelessness were 4 times more likely to use VA emergency departments and had a greater 10-year mortality risk than did veterans who were housed.1 Veterans experiencing homelessness were more likely to be diagnosed with substance use disorder, schizophrenia, liver disease, and/or HIV/AIDS than were their housed counterparts.

Ending veteran homelessness is a federal priority, exemplified by the goal of President Obama to end veteran homelessness by 2015.2 Since the goal’s articulation, veteran homelessness has declined nationally by 33% (24,117 veterans) from 2009 to 2014 however, 49,933 veterans were identified as being homeless on a given night in January 2014.3

Related: Landmark Initiative Signed for Homeless Veterans

A crucial element needed to end veteran homelessness is veteran and health care provider knowledge of existing homeless services and mechanisms of access. In 2012, VHA launched a homelessness screening clinical reminder in the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS), which prompts a discussion of housing status between the veteran and provider.4 The staff of the VA North Texas Health Care System (VANTHCS) Comprehensive Homeless Center Programs (CHCP) realized that homeless housing programs at the facility could be more accessible if staff from each program could screen for all available programs and if a single phone number existed for scheduling appointments. Therefore, VANTHCS transformed its homeless housing screening process to a standardized process through which veterans are screened for all CHCP housing programs during a single screening assessment, Universal Homeless Housing Screening (UHHS).

This article describes the creation of the UHHS, the screening tool, 3-month postimplementation findings, and recommendations based on initial VANTHCS staff experiences with this process. During the redesign of screening process for homeless housing, VANTHCS staff found a paucity of guidance regarding best practices. This article attempts to fill this gap and provide guidance to institutions that are considering standardizing their screening process for homeless housing across multiple programs at different locations.

Background

Established in 1990, VANTHCS CHCP is VA’ s first comprehensive homeless center. The CHCP provides both housing and vocational rehabilitation programs, including 13 housing programs in 6 different cities and long-standing partnerships between CHCP and 3 community agencies whose programs have specific housing for veterans.5 Screenings performed in Dallas, Texas, for CHCP housing programs are completed at 4 separate locations.

Prior to the inception of the UHHS process, access to housing programs was limited by veteran awareness of the programs and transportation to various program locations. To participate in these programs, veterans needed to complete a form for the VA Northeast Program Evaluation Center (NEPEC), which staff at the Healthcare for Homeless Veterans (HCHV) CHCP program could administer. This process created an admission bottleneck, because HCHV staff needed to evaluate veterans even if they were being admitted to non-HCHV programs.

UHHS Creation Process

In 2011, NEPEC launched the electronic Homeless Operations Management and Evaluation System (HOMES) to replace paper-based reporting.6 This tool allowed non-HCHV CHCP staff to complete NEPEC evaluation and allowed CHCP to meet its goal of designing a system where all CHCP housing programs could complete a screening assessment. This goal originated from the desire of then CHCP Director Teresa House-Hatfield to create a more efficient housing screening process and from similar feedback from veterans.

Furthermore, in 2009, then Secretary of Veterans Affairs Eric K. Shinseki described a “no wrong door” philosophy for ending veteran homelessness, which CHCP operationalized by screening veterans for any CHCP housing program regardless of initial point of contact within the CHCP system.2 Subsequently, in 2010, the VA Office of Mental Health Services contracted with Mathematica Policy Research, Inc., to conduct a quality review of VA Mental Health Residential Rehabilitation Treatment Programs. Notable among their recommendations was to create a one-stop screening process for these programs.

Related: Primary Care Medical Services for Homeless Veterans

In 2010, CHCP embarked on a process to transform the facility’s screening procedure to a one-stop assessment with standardized screening questions and create a systematic process to track outcomes across all CHCP housing programs. The new process allowed for a standardized appeal procedure when eligibility for a program was not met. It also improved the ease of communication by having 1 phone number for making appointments or informing about screening times. These changes were enacted without the addition of any new staff positions. Instead, in October 2011, Ms. House-Hatfield tasked Dina Hooshyar of the VANTHCS to champion and spearhead this transformation.

The challenge associated with the UHHS creation process was to balance individual program autonomy with standardized processes. This balance was achieved through weekly calls where Ms. House- Hatfield, Dr. Hooshyar, and CHCP program managers discussed how to design UHHS. The management of the CHCP also actively sought input from CHCP frontline staff. During the preimplementation phase, Dr. Hooshyar gave multiple UHHS trainings to CHCP staff who would become involved in UHHS process, another feedback mechanism.

Program managers retained their programs’ autonomy by picking screeners and the number of employees in that position for their program, screening location and time, and screening type (appointment, walk-in, telephone, and/or combination). Managers and staff also assisted in the creation of the UHHS tool by providing their program’s eligibility criteria and customary psychosocial assessment questions. The UHHS tool not only brought consistency to the screening process, but also removed any perceived biases by asking all veterans the same questions across all UHHS screening locations. Implemented on August 26, 2013, UHHS continues to be used.

UHHS Screening Tool

The UHHS tool is an assessment composed of 4 sections: (1) History; (2) Decision Tree; (3) Specific Program Eligibility Criteria; and (4) Plan. The sections exist as templates in the CPRS.

The History section asks about demographic information, diagnoses, alcohol and illicit drug use history, dependent status, outstanding legal issues, housing status, functional limitations, income and employment status, and potential benefit from and interest in psychosocial rehabilitation and care management. If the veteran would not benefit from and/or is not interested in participating in psychosocial rehabilitation and care management, the screener concludes the assessment, as these factors are eligibility requirements for all CHCP programs. Veterans can appeal their case to the screener’s program manager.

The Decision Tree template consists of 6 core eligibility criteria across programs that can serve to narrow the list of eligible programs: (1) Is the veteran currently homeless; (2) Has the veteran been homeless continuously for ≥ 1 year, or has the veteran had ≥ 4 separate occasions of homelessness in the past 3 years; (3) Does the veteran have a mental health or substance use diagnosis; (4) Can the veteran pay a program fee (9 of 16 UHHS-associated programs have no fees); (5) Is the veteran capable of self-administering medications; and (6) Can the veteran perform activities of daily living and does not need acute hospitalization?

Related: Using H-PACT to Overcome Treatment Obstacles for Homeless Veterans (audio)

Veterans are then asked in which town(s) they want to reside. The questions for the Specific Program Eligibility Criteria section are asked only for those programs for which the veteran is found to be tentatively eligible by the Decision Tree and has interest in participating.

The Plan section gives veterans the opportunity to appeal a UHHS finding to the specific program’s manager whose program they are not eligible to participate. Veterans also rank their preference for the programs for which they are interested and eligible. A shared folder contains all program census information. Through the screening tool, veterans devise a plan to contact the potential admitting program. Veterans are informed about the importance of keeping in contact with these programs, because programs will not hold openings for an indefinite time.

Completion of this screening assessment, which includes HOMES and the UHHS tool, generally takes 1.5 hours. After a veteran undergoes this assessment, a preadmission appointment is made with the first open program for which they are eligible and interested in participating. The main goal of this appointment varies by program, such as finalizing referral processes with associated community partners, performing a preliminary medical clearance, determining whether veterans have already used their program’s maximum allotted time, coordinating a Therapeutic Supported Employment Services assessment, or obtaining the required documents from veterans. If at the preadmission appointment, either the veteran declines participation or the program declines admittance, the veteran can follow up with other programs for which they met eligibility criteria and were interested in participating during the initial UHHS assessment instead of undergoing another housing screening.

Notification of Screening Results

The CHCP staff member who performs the screening is responsible for documenting the veteran’s name, phone number or means of contact, current residence, and housing outcome in a secure shared Microsoft Excel document called Housing Outcome. The Excel IF and VLOOKUP function link the original document to each program’s acceptance and petition documents. This linkage auto populates information entered in the Housing Outcome document to each program’s acceptance and petition documents if the veteran has a housing outcome associated with the program. CHCP staff members then look at their individual program’s acceptance and/or petition documents to see the list of veterans who have a housing outcome involving their program instead of having to sort through the Housing Outcome document. As a backup to the Housing Outcome document, screeners add the point of contact for the programs that the veteran had an associated housing outcome as additional signers to their CPRS screening note.

When UHHS was first implemented, the screeners had a daily call to discuss the screened veterans’ housing outcomes and screener experiences with the new system. Dr. Hooshyar also participated in this call as a means to answer screener questions and to get feedback. Within a month of UHHS implementation, these calls were cancelled, because the screeners felt comfortable with the UHHS process and the majority of housing programs were operating at full capacity.

UHHS Appointment Line

The UHHS appointment phone number uses an automatic call distributor, a call-center technology. Thus, 1 phone number can be answered by multiple people working in separate locations. The challenge was how to connect phones associated with offices located offsite from the VANTHCS campus. The solution was to use Internet phones in addition to existing staff phones.

Results

During the review period from August 26, 2013, to November 27, 2013 (65 workdays), 392 unique veterans attended a UHHS assessment. Four veterans who were screened twice were included only once in the analysis; outcomes from only their initial screenings were evaluated. Three hundred fifty-six veterans completed a UHHS assessment; 36 had an assessment but did not complete it. Rates of veterans not presenting for their scheduled appointments increased over time, from 24% in August 2013 to 50% in November 2013. To address the no-show rate, program managers decreased the number of offered scheduled appointments and increased the number of walk-in visits. Overall, the schedule distribution consisted of about twice as much time allotted for walk-in appointments compared with scheduled appointments. The UHHS appointment line received 873 calls, where the number decreased over time.

The typical screened veteran who completed a UHHS assessment was a non-Hispanic, African American male aged 51 years with no service connection or history of combat who served either in the Vietnam War era, post-Vietnam War era, or Persian Gulf War. He had accessed VANTHCS care in the year prior to screening; owned a working phone; and was staying in a shelter, a place not meant for human habitation, or a substance use treatment program the night prior to screening (Table 1). Only 20 veterans (5%) were ineligible for participation in all programs, because they did not meet core eligibility criteria as defined by the UHHS Decision Tree, their income surpassed the program limit, or they were not eligible for VA care (Table 2).

To determine the housing outcome of the veterans screened during the reviewed period, a 3-month follow-up from the end of the review period was used. During this time, 269 veterans (76%) who completed the UHHS process were housed, with 215 (60%) veterans housed in a UHHS-associated housing program (Table 3). Of the veterans who completed a UHHS assessment, 45 veterans (13%) did not complete the screening process; admitting program staff documented in CPRS unsuccessful attempts at reaching 12 veterans (3%), among whom 4 had no working phone at the time of their UHHS assessment. Time to admission depended on the program mission, openings, and the veteran’s UHHS engagement. Admission date indicates the date that programs housed veterans except in the case of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development-VA Supportive Housing (HUD-VASH), where admission date indicates the date the veteran gave all required documents to HUD-VASH staff.

Discussion

Prior to the inception of UHHS, the staff of the CHCP housing program did not have a standardized process for communication across programs about veterans’ housing status and outcomes. Veterans went to multiple locations for screening if they were interested in > 1 program or if they were not admitted to the first program they approached. The UHHS process improved communication across CHCP housing programs, resulting in increased veteran accessibility to these programs as suggested by 3 CHCP housing programs having fewer days with openings post-UHHS implementation. Furthermore, a new screener position did not need to be created, because existing CHCP social workers were all capable screeners due to process standardization.

Fifty-five percent of the screened veterans were interested in and eligible for participation in > 1 housing program. They were eligible for 3 programs on average and were usually admitted to the housing program with the earliest opening. The need for screenings across all the CHCP housing programs was potentially decreased by ≥ one-third. This increased available time for the screeners to accomplish their other clinical responsibilities.

Limitations

A limitation of the review period evaluation is little information on noncompleters. The available data are confined to information documented in CPRS regarding why 45 veterans (13% of those who completed UHHS assessment) did not complete the screening process. For 12, admitting staff of the housing program documented in CPRS that they had been unable to reach the veteran; 9 of these veterans attended subsequent non-UHHS VANTHCS visits. To further improve the homeless housing delivery service, the creation of a CPRS-related process that informs VA clinicians that a housing program is attempting to contact a veteran is needed.

Challenges and Recommendations

Because the Housing Outcome document is a shared document, only 1 person at a time can save information in it. Facility staff have been unable to create a simple macro that closes the document automatically. Instead, screeners who need to save information when a document is already opened elsewhere must use a group e-mail list to alert others to close the document.

Streamlining the communication channel between the screeners and management evolved from the daily call, to e-mailing and program managers discussing topics with their staff, to Dr. Hooshyar facilitating a weekly call for screeners and program managers.

Optimizing the ratio of walk-in to scheduled appointments took time. Prior to the UHHS process, some CHCP housing programs offered scheduled appointments, whereas others had walk-in appointments. The decision to offer in-person scheduled appointments for veterans who preferred scheduled appointments or who commuted from a distance was made. Universal Homeless Housing Screening staff also offered scheduled telephone appointments for veterans who lacked transportation.

At times, admitting program staff was unable to reach veterans eligible for and interested in their program, despite screeners recommending to veterans that they should provide these programs with any changes in their contact information.

Recommendations for designing a screening process for homeless housing include:

- Have periodic retreats instead of weekly conference calls to quicken the pre-implementation process.

- Start with a pilot that includes some potential screeners to test the implementation process. The screeners involved in the pilot would train future screeners to expand the screener pool.

- Invest time in electronic tracking tools despite upfront and maintenance time requirements.

- Offer more walk-in than scheduled screening appointments.

- Embrace the idea that the pro-cess is always under development.

Conclusion

To ameliorate anxiety associated with changing the system, UHHS- associated staff redesigned the housing screening process through openness to stakeholder feedback and building on consensus. The staff also nurtured a culture that could change newly revised processes, depending on quality assurance findings. Without this method, the unknown likely would have propagated continued status quo. Universal Homeless Housing Screening processes improved veteran access to CHCP housing programs through instituting a one-stop housing screening assessment that also reduced the potential number of screenings by ≥ one-third.

Acknowledgments

The authors greatly appreciate the input of the many people involved in the creation of the UHHS process, in particular Daniel Anderson, Heather Arredondo, Tara Ayala, TiieShaiyon Banton, Melody Boyet, Amelia Bradley, Timothy Brown, Carnisha Campbell, Donald Capps, Burnell Carden Jr, Pushpi Chaudhary, Howard Cunningham, Rachael David, Marianna Demko, Derrick Evans, Steven Fisher, Kimberly Fite, Fatina Ford, Christi Godfrey, Gerald Goodwin, Melvin Haley, Tony Hall, Jessica Hennessey, Teresa House-Hatfield, Don Hubbard, Kathryn Jacob, Tonja King, Cecelia Knight, Janine Lenger-Gvist, Vickie Linden, Julia Long, Kristin Manley, Peggy Martin, Treva McDaniel, William McNair, Tammy Miller, Jeffery Milligan, Anhloan Nguyen, Tywanna Nichols, Cheryl Paul, Catherine Orsak, Dustin Perkins, Claudette Phillips, Joan Prescott, John Purkey, Martin Roback, Catriska Robertson, Charles Ross, Shanna Ruppert, Stephanie Saldivar, Linda Saucedo, Inga Sinclair-Henderson, John Smith, Zaire Smith, Cheryl Stringer, Valetta Ward, Carolyn Washington, Tammra Wood, and Skylar Woods-Nunley. They would also like to thank the veterans for their service and feedback.

Author disclosures

Dr. North discloses research support from National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, and VA and consultant fees from the University of Missouri-Columbia. Dr. Surís is Local Site Investigator for VA CSP #589 VIPSTAR-Veterans Individual Placement and Support Towards Advancing Recovery (PI Lori Davis, MD). She is co- investigator for VISN 17 grant Association of Myocardial Viability to Symptom Improvement post-CTO PCI (PI-Shuaib Abdullah, MD) and co-investigator for National Institutes on Drug Abuse grant Lidocaine Infusion as a Treatment for Cocaine Relapse and Craving (PI-Bryon Adinoff, MD). In addition, Dr. Surís is co-site-PI for the upcoming VA CSP #590 Lithium for Suicidal Behavior in Mood Disorders.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

1. Tsai J, Doran KM, Rosenheck RA. When health insurance is not a factor: National comparison of homeless and nonhomeless US veterans who use Veterans Affairs emergency departments. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(suppl 2):S225-S231.

2. Secretary Shinseki Details Plan to End Homelessness for Veterans [news release]. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs: Office of Public and Intergovernmental Affairs. http://www.va.gov/opa/pressrel/pressrelease.cfm?id=1807. Published November 3, 2009. Accessed March 3, 2014.

3. U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development: Office of Community Planning and Development. The 2014 Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress. Part 1 Point-In-Time Estimates of Homelessness. https://www.hudexchange.info/resources/documents /2014-AHAR-Part1.pdf. Published October 2014. Accessed March 18, 2015.

4. Montgomery AE, Fargo JD, Byrne TH, Kane VR, Culhane DP. Universal screening for homelessness and risk for homelessness in the Veterans Health Administration. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(suppl 2):S210-S211.

5. Berman S, Barilich JE, Rosenheck R, Koerber G. The VA’s first comprehensive homeless center: A catalyst for public and private partnerships. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1993;44(12):1183-1184.

6. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Homeless Operations Management and Evaluation System (HOMES) User Manual–Phase 1. http://www.vfwsc.org/homes.pdf. Published April 19, 2011. Accessed March 3, 2014.

1. Tsai J, Doran KM, Rosenheck RA. When health insurance is not a factor: National comparison of homeless and nonhomeless US veterans who use Veterans Affairs emergency departments. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(suppl 2):S225-S231.

2. Secretary Shinseki Details Plan to End Homelessness for Veterans [news release]. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs: Office of Public and Intergovernmental Affairs. http://www.va.gov/opa/pressrel/pressrelease.cfm?id=1807. Published November 3, 2009. Accessed March 3, 2014.

3. U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development: Office of Community Planning and Development. The 2014 Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress. Part 1 Point-In-Time Estimates of Homelessness. https://www.hudexchange.info/resources/documents /2014-AHAR-Part1.pdf. Published October 2014. Accessed March 18, 2015.

4. Montgomery AE, Fargo JD, Byrne TH, Kane VR, Culhane DP. Universal screening for homelessness and risk for homelessness in the Veterans Health Administration. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(suppl 2):S210-S211.

5. Berman S, Barilich JE, Rosenheck R, Koerber G. The VA’s first comprehensive homeless center: A catalyst for public and private partnerships. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1993;44(12):1183-1184.

6. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Homeless Operations Management and Evaluation System (HOMES) User Manual–Phase 1. http://www.vfwsc.org/homes.pdf. Published April 19, 2011. Accessed March 3, 2014.