User login

The media often make complex issues sound simple—10 tips for this, the best eight ways to do that. Vexing problems are neatly addressed in a page or two, ending with bullet points lest the reader misunderstand the sage advice offered. While The Hospitalist would not presume that a task as fraught as hospitalist scheduling could be approached using tips similar to those suggested for soothing toddler temper tantrums, we lightly present some collective wisdom on scheduling.

Before sharing how several hospitalist medicine groups (HMGs) previously profiled in The Hospitalist attacked their toughest scheduling issues, we looked at the “2005-2006 SHM Survey: State of the Hospital Medicine Movement” of 2,550 hospitalists in 396 HMGs for insights about how hospitalists spend their time and how they struggle to balance work and personal lives. This background information provides a context for scheduling.

Here’s what the data say. For starters, the average hospitalist is not fresh out of residency. The SHM survey says the average HMG leader is 41, with 5.1 years of hospitalist experience. Non-leader hospitalists are, on average, 37 and have been hospitalists for an average of three years. Hospitalist physician staffing levels increased from 8.49 to 8.81 physicians, while non-physician staffing decreased from 3.10 to 1.09 FTEs.

Hospitalists spend 10% of their time in non-clinical activities, and that 10% is divided as follows: committee work, 92%; quality improvement, 86%; developing practice guidelines, 72%; and teaching medical students, 51%. New since the last survey is the fact that 52% of HMGs became involved in rapid response teams, while 19% of HMGs spend time on computerized physician order entry (CPOE) systems.

Scheduling’s impact on hospitalists’ lives remains a big issue. Forty-two percent of HMG leaders cited balancing work hours and personal life balance as problematic, 29% were concerned about their daily workloads, 23% said that expectations and demands on hospitalists were increasing, 15% worried about career sustainability and retaining hospitalists, while 11% cited scheduling per se as challenging.

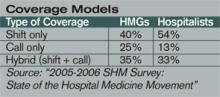

Coverage arrangements changed significantly from the 2003-2004 survey. More HMGs now use hybrid (shift + call) coverage (35% in ’05-’06 versus 27% in ’03-’04) and fewer use call only (25% in ’05-’06 versus 36% in ’03-’04).

SHM’s survey shows that hospitalists working shift-only schedules average 187 shifts, 10.8 hours a day. Call-only hospitalists average 150 days on call, for 15.7-hour days. Hybrid schedules average 206 days, with each day spanning 8.9 hours; of those days, 82 are 12.8-hour on-call days.

For the thorny issue of night call, of the hospitalists who do cover call, 41% cover call from home, 51% are on site, and 8% of HMGs don’t cover call. About one-quarter of HMGs provide an on-site nocturnist, but most practices can’t justify the compensation package for the one or two admits and patient visits they have during the average night. To fill gaps, 24% of HMGs used moonlighters; 11% rely on residents; and 5% and 4%, respectively, use physician assistants and nurse practitioners.

In summary, HMG staffing has increased slightly, more groups are using hybrid shift/call arrangements, most hospitalists work long hours compressed into approximately 180 days per year, and scheduling for work/personal life balance remains a major issue for HMG leaders and their hospitalists.

Common Sense

Hospitalist schedules have evolved from what doctors know best—shift work or office-based practice hours. Most HMGs organize hospitalist shifts into blocks, with the most popular block still the seven days on/seven days off schedule. Block scheduling becomes easier as HMGs grow to six to 10 physicians.

While the seven on/seven off schedule has become popular, many find that it is stressful and can lead to burnout. The on days’ long hours can make it hard to recover on days off. John Nelson, MD, director of the hospitalist practice at Overlake Hospital in Bellevue, Wash., SHM co-founder, and “Practice Management” columnist for The Hospitalist, contends in published writings that the seven on/seven off schedule squeezes a full-time job into only 182.5 days; the stress that such intensity entails—both personally and professionally—is tremendous. Compressed schedules, in trying to shoehorn the average workload into too few days, can also lead to below average relative value units (RVUs) and other productivity measures.

Dr. Nelson advises reducing the daily workload by spreading the work over 210 to 220 days annually. While that doesn’t afford the luxury of seven consecutive days off, it allows the doctors to titrate their work out over more days so that the average day will be less busy. He also advises flexibility in starting and stopping times for individual shifts, allowing HMGs to adjust to changes in patient volume and workload. Scheduling elasticity lets doctors adapt to a day’s ebbs and flows, perhaps taking a lunch hour or driving a child to soccer practice. That may mean early evening hospital time to finish up, but variety keeps life interesting.

About patient volume (another scheduling headache) Dr. Nelson says that capping individual physician workloads makes sense because overwhelmed physicians tend to make mistakes. But capping a practice’s volume looks unprofessional and can limit a group’s earnings. Several HMGs we profiled disagree with Dr. Nelson. (See below.) Most didn’t actually cap patient volume, but instead restricted the number of physicians transferring inpatients to the HMG, adding more referral sources only as patient volume stabilized or new hospitalists came on board to handle growing volume.

Some of the best-functioning HMGs we encountered have lured well-known office-based doctors ready for a change. Eager to shed a practice’s financial and administrative burden, as well as regular office hours, these physicians relish the chance to return to hospital work—their first career love. They also remember what it’s like to have to work Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Year’s, and the more generous among them volunteer for those shifts so that younger hospitalists can spend holidays with their families.

Awards for Struggling through Scheduling Issues

Data on where the average HMG stands on scheduling are important, but every successful group has physician leaders who craft schedules based on a broad and subtle understanding of their medical communities. They factor in whether the areas surrounding their hospitals are stable, growing, or shrinking; the patient mix they’re likely to see; their hospital’s corporate culture and those of the referring office practices. For recruiting, they think about whether their location offers an attractive lifestyle or how they can sweeten the pot if it doesn’t. If they’re at an academic medical center, they’ll have a lower average daily census (ADC) and different expectations about productivity than if they’re a private HMG at a community hospital. Chemistry, meaning whether or not a new hospitalist who looks great on paper and interviews well will gel with the group or upset the apple cart, is a tantalizing unknown.

So here’s our list of HMGs that wrestled successfully with their scheduling challenges:

The “Are We Good, or What? Award” goes to Health Partners of Minneapolis, Minn. These hospitalists have won numerous SHM awards for clinical excellence, reflecting their high standards and competence. The 25 physicians and two nurse practitioners can choose between two block schedules: seven days on/seven days off or 14 days on/14 days off. They also work two night shifts a month—6 p.m. to 8 a.m.—backing up residents. Key to avoiding burnout on this schedule is geographical deployment. Hospitalists work only in one or two units, rather than covering the entire seven-floor hospital.

The “Go Gators Award” goes to Sage Alachua General Hospital of Gainesville, Fla. Whenever possible, these hospitalists attend the home football games of their beloved Florida Gators, 2007 Bowl Championship Series winners. This reflects their strong ties to the University of Florida Medical School—also Dr. Nelson’s alma mater—and the many physicians who come from or settle in the Gainesville area. The group started with three hospitalists on a seven on/seven off schedule, backed up by a nocturnist who quit due to the heavy volume of night admissions. They now have nine hospitalists—all family practice physicians—working a seven/seven schedule. Each one covers Monday through Thursday night call every nine weeks, with residents handling Friday through Sunday. An internist who retired from his office practice works Monday through Friday mornings and occasionally covers holiday shifts for his younger colleagues.

The “He’s Not Heavy, He’s My Colleague Award” goes to Nashua, N.H.-based Southern New Hampshire Medical Center (SNHMC) hospitalists: Stewart Fulton, DO, SNHMC’s solo hospitalist for more than a year, answered call 24/7, with help from the community doctors whose inpatients he was following. Though he was joined eventually by the group’s second hospitalist, Suneetha Kammila, MD, chaos reigned for the next year. They hired a third hospitalist and eventually grew to five physicians and moved from call to shifts. By the third year, SNHMC had 10 hospitalists—two teams of five—and moved to the seven days on/seven days off schedule everyone wanted. The tenacity of HMG leaders Dr. Fulton and Dr. Kammila allowed the group to survive its early scheduling hardships.

The “If We Were Cars, We’d Be Benzes or Beemers Award” goes to the Colorado Kaiser-Permanente hospitalists in Denver. Part of an organization that prides itself on perfecting processes and improving transparency in healthcare, this group had all the tools to get their scheduling right. They started with the widely used seven on/seven off schedule but found it dissatisfying both personally and professionally. Through consensus, they arrived at a schedule of six consecutive eight-hour days of rounding with one triage physician handling after-hours call. There are two hospitalists on-site, 24 hours a day, seven days a week, and they admit and cross-cover after 4 p.m.

The “Planning Is Everything Award” goes to the Brockie Hospitalist Group in York, Pa. Both the hospital and the city of York are in a sustained growth mode. There are several large outpatient practices waiting for Brockie’s hospitalist group to assume their inpatients. The 18 hospitalists have wisely demurred, allowing their office-based colleagues to turn over the inpatient work only when the hospitalists can handle the additional load. Hospitalists choose either a 132-hour or a 147-hour schedule that is divided into blocks over three weeks, with a productivity/incentive program that changes as the increasing workload dictates.

The “Scheduling Is a Piece of Cake Award” goes out to Scott Oxenhandler, MD, chief hospitalist at Hollywood Memorial Hospital in Florida. Dr. Oxenhandler left an office practice for the hospitalist’s chance to practice acute care medicine with good compensation and benefits, reduced paperwork, and a great schedule. He recruited 21 hospitalists. Most work an 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. schedule, while a nocturnist covers the hours from 8 p.m. to 8 a.m. Ten physicians handle the 5 to 8 p.m. “short call” four times a month. The large number of hospitalists allows flexibility in scheduling to accommodate individual needs.

The “We Grew Past Our Mistakes Award” has been earned by Presbyterian Inpatient Care Systems in Charlotte, N.C. This program started as a two-physician, 5 p.m. to 7 a.m. admitting service for community physicians too busy to cover call. The hospitalists quit, wanting more out of medicine than an admitting service. Four hospitalists who were committed to providing inpatient care replaced them, with better results. The group now has more than 30 physicians working 12-hour shifts and co-managing, with sub-specialists, complex care. A nocturnist, working an eight-hour shift instead of the 12-hour shift that burned out a predecessor, covers night admissions and call.

Tighter Times?

Could the days of hospitalists fretting about work/life balance and optimal schedules be drawing to an end, as hospitals cast a jaundiced eye on the value hospitalists create versus what they cost? Chris Nussbaum, MD, CEO of Synergy Medical Group, based in Brandon, Fla., thinks so. He employs 10 hospitalists who cover six Tampa-area hospitals located within 15 minutes of each other. The group just switched from call to a 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. shift schedule. Dr. Nussbaum deploys hospitalists based on each hospital’s average daily census, so a doctor could cover several hospitals a day.

On an average day, eight hospitalists work days, one works the night shift, and one is off. Dr. Nussbaum’s rationale: “We’re very aggressive about time management. Our first year docs earn a base salary of $200,000, with $40,000 in productivity bonuses.” He adds, “I believe hospitalist medicine is moving in the direction we’ve taken. Scheduling is critical, and hospitalists need to work harder and be entrepreneurial. … In today’s market, prima donna docs command high salaries and have an ADC of 10 patients. That will change soon as supply catches up with demand.” TH

Marlene Piturro regularly profiles HMGs and trends in hospital medicine for The Hospitalist.

The media often make complex issues sound simple—10 tips for this, the best eight ways to do that. Vexing problems are neatly addressed in a page or two, ending with bullet points lest the reader misunderstand the sage advice offered. While The Hospitalist would not presume that a task as fraught as hospitalist scheduling could be approached using tips similar to those suggested for soothing toddler temper tantrums, we lightly present some collective wisdom on scheduling.

Before sharing how several hospitalist medicine groups (HMGs) previously profiled in The Hospitalist attacked their toughest scheduling issues, we looked at the “2005-2006 SHM Survey: State of the Hospital Medicine Movement” of 2,550 hospitalists in 396 HMGs for insights about how hospitalists spend their time and how they struggle to balance work and personal lives. This background information provides a context for scheduling.

Here’s what the data say. For starters, the average hospitalist is not fresh out of residency. The SHM survey says the average HMG leader is 41, with 5.1 years of hospitalist experience. Non-leader hospitalists are, on average, 37 and have been hospitalists for an average of three years. Hospitalist physician staffing levels increased from 8.49 to 8.81 physicians, while non-physician staffing decreased from 3.10 to 1.09 FTEs.

Hospitalists spend 10% of their time in non-clinical activities, and that 10% is divided as follows: committee work, 92%; quality improvement, 86%; developing practice guidelines, 72%; and teaching medical students, 51%. New since the last survey is the fact that 52% of HMGs became involved in rapid response teams, while 19% of HMGs spend time on computerized physician order entry (CPOE) systems.

Scheduling’s impact on hospitalists’ lives remains a big issue. Forty-two percent of HMG leaders cited balancing work hours and personal life balance as problematic, 29% were concerned about their daily workloads, 23% said that expectations and demands on hospitalists were increasing, 15% worried about career sustainability and retaining hospitalists, while 11% cited scheduling per se as challenging.

Coverage arrangements changed significantly from the 2003-2004 survey. More HMGs now use hybrid (shift + call) coverage (35% in ’05-’06 versus 27% in ’03-’04) and fewer use call only (25% in ’05-’06 versus 36% in ’03-’04).

SHM’s survey shows that hospitalists working shift-only schedules average 187 shifts, 10.8 hours a day. Call-only hospitalists average 150 days on call, for 15.7-hour days. Hybrid schedules average 206 days, with each day spanning 8.9 hours; of those days, 82 are 12.8-hour on-call days.

For the thorny issue of night call, of the hospitalists who do cover call, 41% cover call from home, 51% are on site, and 8% of HMGs don’t cover call. About one-quarter of HMGs provide an on-site nocturnist, but most practices can’t justify the compensation package for the one or two admits and patient visits they have during the average night. To fill gaps, 24% of HMGs used moonlighters; 11% rely on residents; and 5% and 4%, respectively, use physician assistants and nurse practitioners.

In summary, HMG staffing has increased slightly, more groups are using hybrid shift/call arrangements, most hospitalists work long hours compressed into approximately 180 days per year, and scheduling for work/personal life balance remains a major issue for HMG leaders and their hospitalists.

Common Sense

Hospitalist schedules have evolved from what doctors know best—shift work or office-based practice hours. Most HMGs organize hospitalist shifts into blocks, with the most popular block still the seven days on/seven days off schedule. Block scheduling becomes easier as HMGs grow to six to 10 physicians.

While the seven on/seven off schedule has become popular, many find that it is stressful and can lead to burnout. The on days’ long hours can make it hard to recover on days off. John Nelson, MD, director of the hospitalist practice at Overlake Hospital in Bellevue, Wash., SHM co-founder, and “Practice Management” columnist for The Hospitalist, contends in published writings that the seven on/seven off schedule squeezes a full-time job into only 182.5 days; the stress that such intensity entails—both personally and professionally—is tremendous. Compressed schedules, in trying to shoehorn the average workload into too few days, can also lead to below average relative value units (RVUs) and other productivity measures.

Dr. Nelson advises reducing the daily workload by spreading the work over 210 to 220 days annually. While that doesn’t afford the luxury of seven consecutive days off, it allows the doctors to titrate their work out over more days so that the average day will be less busy. He also advises flexibility in starting and stopping times for individual shifts, allowing HMGs to adjust to changes in patient volume and workload. Scheduling elasticity lets doctors adapt to a day’s ebbs and flows, perhaps taking a lunch hour or driving a child to soccer practice. That may mean early evening hospital time to finish up, but variety keeps life interesting.

About patient volume (another scheduling headache) Dr. Nelson says that capping individual physician workloads makes sense because overwhelmed physicians tend to make mistakes. But capping a practice’s volume looks unprofessional and can limit a group’s earnings. Several HMGs we profiled disagree with Dr. Nelson. (See below.) Most didn’t actually cap patient volume, but instead restricted the number of physicians transferring inpatients to the HMG, adding more referral sources only as patient volume stabilized or new hospitalists came on board to handle growing volume.

Some of the best-functioning HMGs we encountered have lured well-known office-based doctors ready for a change. Eager to shed a practice’s financial and administrative burden, as well as regular office hours, these physicians relish the chance to return to hospital work—their first career love. They also remember what it’s like to have to work Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Year’s, and the more generous among them volunteer for those shifts so that younger hospitalists can spend holidays with their families.

Awards for Struggling through Scheduling Issues

Data on where the average HMG stands on scheduling are important, but every successful group has physician leaders who craft schedules based on a broad and subtle understanding of their medical communities. They factor in whether the areas surrounding their hospitals are stable, growing, or shrinking; the patient mix they’re likely to see; their hospital’s corporate culture and those of the referring office practices. For recruiting, they think about whether their location offers an attractive lifestyle or how they can sweeten the pot if it doesn’t. If they’re at an academic medical center, they’ll have a lower average daily census (ADC) and different expectations about productivity than if they’re a private HMG at a community hospital. Chemistry, meaning whether or not a new hospitalist who looks great on paper and interviews well will gel with the group or upset the apple cart, is a tantalizing unknown.

So here’s our list of HMGs that wrestled successfully with their scheduling challenges:

The “Are We Good, or What? Award” goes to Health Partners of Minneapolis, Minn. These hospitalists have won numerous SHM awards for clinical excellence, reflecting their high standards and competence. The 25 physicians and two nurse practitioners can choose between two block schedules: seven days on/seven days off or 14 days on/14 days off. They also work two night shifts a month—6 p.m. to 8 a.m.—backing up residents. Key to avoiding burnout on this schedule is geographical deployment. Hospitalists work only in one or two units, rather than covering the entire seven-floor hospital.

The “Go Gators Award” goes to Sage Alachua General Hospital of Gainesville, Fla. Whenever possible, these hospitalists attend the home football games of their beloved Florida Gators, 2007 Bowl Championship Series winners. This reflects their strong ties to the University of Florida Medical School—also Dr. Nelson’s alma mater—and the many physicians who come from or settle in the Gainesville area. The group started with three hospitalists on a seven on/seven off schedule, backed up by a nocturnist who quit due to the heavy volume of night admissions. They now have nine hospitalists—all family practice physicians—working a seven/seven schedule. Each one covers Monday through Thursday night call every nine weeks, with residents handling Friday through Sunday. An internist who retired from his office practice works Monday through Friday mornings and occasionally covers holiday shifts for his younger colleagues.

The “He’s Not Heavy, He’s My Colleague Award” goes to Nashua, N.H.-based Southern New Hampshire Medical Center (SNHMC) hospitalists: Stewart Fulton, DO, SNHMC’s solo hospitalist for more than a year, answered call 24/7, with help from the community doctors whose inpatients he was following. Though he was joined eventually by the group’s second hospitalist, Suneetha Kammila, MD, chaos reigned for the next year. They hired a third hospitalist and eventually grew to five physicians and moved from call to shifts. By the third year, SNHMC had 10 hospitalists—two teams of five—and moved to the seven days on/seven days off schedule everyone wanted. The tenacity of HMG leaders Dr. Fulton and Dr. Kammila allowed the group to survive its early scheduling hardships.

The “If We Were Cars, We’d Be Benzes or Beemers Award” goes to the Colorado Kaiser-Permanente hospitalists in Denver. Part of an organization that prides itself on perfecting processes and improving transparency in healthcare, this group had all the tools to get their scheduling right. They started with the widely used seven on/seven off schedule but found it dissatisfying both personally and professionally. Through consensus, they arrived at a schedule of six consecutive eight-hour days of rounding with one triage physician handling after-hours call. There are two hospitalists on-site, 24 hours a day, seven days a week, and they admit and cross-cover after 4 p.m.

The “Planning Is Everything Award” goes to the Brockie Hospitalist Group in York, Pa. Both the hospital and the city of York are in a sustained growth mode. There are several large outpatient practices waiting for Brockie’s hospitalist group to assume their inpatients. The 18 hospitalists have wisely demurred, allowing their office-based colleagues to turn over the inpatient work only when the hospitalists can handle the additional load. Hospitalists choose either a 132-hour or a 147-hour schedule that is divided into blocks over three weeks, with a productivity/incentive program that changes as the increasing workload dictates.

The “Scheduling Is a Piece of Cake Award” goes out to Scott Oxenhandler, MD, chief hospitalist at Hollywood Memorial Hospital in Florida. Dr. Oxenhandler left an office practice for the hospitalist’s chance to practice acute care medicine with good compensation and benefits, reduced paperwork, and a great schedule. He recruited 21 hospitalists. Most work an 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. schedule, while a nocturnist covers the hours from 8 p.m. to 8 a.m. Ten physicians handle the 5 to 8 p.m. “short call” four times a month. The large number of hospitalists allows flexibility in scheduling to accommodate individual needs.

The “We Grew Past Our Mistakes Award” has been earned by Presbyterian Inpatient Care Systems in Charlotte, N.C. This program started as a two-physician, 5 p.m. to 7 a.m. admitting service for community physicians too busy to cover call. The hospitalists quit, wanting more out of medicine than an admitting service. Four hospitalists who were committed to providing inpatient care replaced them, with better results. The group now has more than 30 physicians working 12-hour shifts and co-managing, with sub-specialists, complex care. A nocturnist, working an eight-hour shift instead of the 12-hour shift that burned out a predecessor, covers night admissions and call.

Tighter Times?

Could the days of hospitalists fretting about work/life balance and optimal schedules be drawing to an end, as hospitals cast a jaundiced eye on the value hospitalists create versus what they cost? Chris Nussbaum, MD, CEO of Synergy Medical Group, based in Brandon, Fla., thinks so. He employs 10 hospitalists who cover six Tampa-area hospitals located within 15 minutes of each other. The group just switched from call to a 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. shift schedule. Dr. Nussbaum deploys hospitalists based on each hospital’s average daily census, so a doctor could cover several hospitals a day.

On an average day, eight hospitalists work days, one works the night shift, and one is off. Dr. Nussbaum’s rationale: “We’re very aggressive about time management. Our first year docs earn a base salary of $200,000, with $40,000 in productivity bonuses.” He adds, “I believe hospitalist medicine is moving in the direction we’ve taken. Scheduling is critical, and hospitalists need to work harder and be entrepreneurial. … In today’s market, prima donna docs command high salaries and have an ADC of 10 patients. That will change soon as supply catches up with demand.” TH

Marlene Piturro regularly profiles HMGs and trends in hospital medicine for The Hospitalist.

The media often make complex issues sound simple—10 tips for this, the best eight ways to do that. Vexing problems are neatly addressed in a page or two, ending with bullet points lest the reader misunderstand the sage advice offered. While The Hospitalist would not presume that a task as fraught as hospitalist scheduling could be approached using tips similar to those suggested for soothing toddler temper tantrums, we lightly present some collective wisdom on scheduling.

Before sharing how several hospitalist medicine groups (HMGs) previously profiled in The Hospitalist attacked their toughest scheduling issues, we looked at the “2005-2006 SHM Survey: State of the Hospital Medicine Movement” of 2,550 hospitalists in 396 HMGs for insights about how hospitalists spend their time and how they struggle to balance work and personal lives. This background information provides a context for scheduling.

Here’s what the data say. For starters, the average hospitalist is not fresh out of residency. The SHM survey says the average HMG leader is 41, with 5.1 years of hospitalist experience. Non-leader hospitalists are, on average, 37 and have been hospitalists for an average of three years. Hospitalist physician staffing levels increased from 8.49 to 8.81 physicians, while non-physician staffing decreased from 3.10 to 1.09 FTEs.

Hospitalists spend 10% of their time in non-clinical activities, and that 10% is divided as follows: committee work, 92%; quality improvement, 86%; developing practice guidelines, 72%; and teaching medical students, 51%. New since the last survey is the fact that 52% of HMGs became involved in rapid response teams, while 19% of HMGs spend time on computerized physician order entry (CPOE) systems.

Scheduling’s impact on hospitalists’ lives remains a big issue. Forty-two percent of HMG leaders cited balancing work hours and personal life balance as problematic, 29% were concerned about their daily workloads, 23% said that expectations and demands on hospitalists were increasing, 15% worried about career sustainability and retaining hospitalists, while 11% cited scheduling per se as challenging.

Coverage arrangements changed significantly from the 2003-2004 survey. More HMGs now use hybrid (shift + call) coverage (35% in ’05-’06 versus 27% in ’03-’04) and fewer use call only (25% in ’05-’06 versus 36% in ’03-’04).

SHM’s survey shows that hospitalists working shift-only schedules average 187 shifts, 10.8 hours a day. Call-only hospitalists average 150 days on call, for 15.7-hour days. Hybrid schedules average 206 days, with each day spanning 8.9 hours; of those days, 82 are 12.8-hour on-call days.

For the thorny issue of night call, of the hospitalists who do cover call, 41% cover call from home, 51% are on site, and 8% of HMGs don’t cover call. About one-quarter of HMGs provide an on-site nocturnist, but most practices can’t justify the compensation package for the one or two admits and patient visits they have during the average night. To fill gaps, 24% of HMGs used moonlighters; 11% rely on residents; and 5% and 4%, respectively, use physician assistants and nurse practitioners.

In summary, HMG staffing has increased slightly, more groups are using hybrid shift/call arrangements, most hospitalists work long hours compressed into approximately 180 days per year, and scheduling for work/personal life balance remains a major issue for HMG leaders and their hospitalists.

Common Sense

Hospitalist schedules have evolved from what doctors know best—shift work or office-based practice hours. Most HMGs organize hospitalist shifts into blocks, with the most popular block still the seven days on/seven days off schedule. Block scheduling becomes easier as HMGs grow to six to 10 physicians.

While the seven on/seven off schedule has become popular, many find that it is stressful and can lead to burnout. The on days’ long hours can make it hard to recover on days off. John Nelson, MD, director of the hospitalist practice at Overlake Hospital in Bellevue, Wash., SHM co-founder, and “Practice Management” columnist for The Hospitalist, contends in published writings that the seven on/seven off schedule squeezes a full-time job into only 182.5 days; the stress that such intensity entails—both personally and professionally—is tremendous. Compressed schedules, in trying to shoehorn the average workload into too few days, can also lead to below average relative value units (RVUs) and other productivity measures.

Dr. Nelson advises reducing the daily workload by spreading the work over 210 to 220 days annually. While that doesn’t afford the luxury of seven consecutive days off, it allows the doctors to titrate their work out over more days so that the average day will be less busy. He also advises flexibility in starting and stopping times for individual shifts, allowing HMGs to adjust to changes in patient volume and workload. Scheduling elasticity lets doctors adapt to a day’s ebbs and flows, perhaps taking a lunch hour or driving a child to soccer practice. That may mean early evening hospital time to finish up, but variety keeps life interesting.

About patient volume (another scheduling headache) Dr. Nelson says that capping individual physician workloads makes sense because overwhelmed physicians tend to make mistakes. But capping a practice’s volume looks unprofessional and can limit a group’s earnings. Several HMGs we profiled disagree with Dr. Nelson. (See below.) Most didn’t actually cap patient volume, but instead restricted the number of physicians transferring inpatients to the HMG, adding more referral sources only as patient volume stabilized or new hospitalists came on board to handle growing volume.

Some of the best-functioning HMGs we encountered have lured well-known office-based doctors ready for a change. Eager to shed a practice’s financial and administrative burden, as well as regular office hours, these physicians relish the chance to return to hospital work—their first career love. They also remember what it’s like to have to work Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Year’s, and the more generous among them volunteer for those shifts so that younger hospitalists can spend holidays with their families.

Awards for Struggling through Scheduling Issues

Data on where the average HMG stands on scheduling are important, but every successful group has physician leaders who craft schedules based on a broad and subtle understanding of their medical communities. They factor in whether the areas surrounding their hospitals are stable, growing, or shrinking; the patient mix they’re likely to see; their hospital’s corporate culture and those of the referring office practices. For recruiting, they think about whether their location offers an attractive lifestyle or how they can sweeten the pot if it doesn’t. If they’re at an academic medical center, they’ll have a lower average daily census (ADC) and different expectations about productivity than if they’re a private HMG at a community hospital. Chemistry, meaning whether or not a new hospitalist who looks great on paper and interviews well will gel with the group or upset the apple cart, is a tantalizing unknown.

So here’s our list of HMGs that wrestled successfully with their scheduling challenges:

The “Are We Good, or What? Award” goes to Health Partners of Minneapolis, Minn. These hospitalists have won numerous SHM awards for clinical excellence, reflecting their high standards and competence. The 25 physicians and two nurse practitioners can choose between two block schedules: seven days on/seven days off or 14 days on/14 days off. They also work two night shifts a month—6 p.m. to 8 a.m.—backing up residents. Key to avoiding burnout on this schedule is geographical deployment. Hospitalists work only in one or two units, rather than covering the entire seven-floor hospital.

The “Go Gators Award” goes to Sage Alachua General Hospital of Gainesville, Fla. Whenever possible, these hospitalists attend the home football games of their beloved Florida Gators, 2007 Bowl Championship Series winners. This reflects their strong ties to the University of Florida Medical School—also Dr. Nelson’s alma mater—and the many physicians who come from or settle in the Gainesville area. The group started with three hospitalists on a seven on/seven off schedule, backed up by a nocturnist who quit due to the heavy volume of night admissions. They now have nine hospitalists—all family practice physicians—working a seven/seven schedule. Each one covers Monday through Thursday night call every nine weeks, with residents handling Friday through Sunday. An internist who retired from his office practice works Monday through Friday mornings and occasionally covers holiday shifts for his younger colleagues.

The “He’s Not Heavy, He’s My Colleague Award” goes to Nashua, N.H.-based Southern New Hampshire Medical Center (SNHMC) hospitalists: Stewart Fulton, DO, SNHMC’s solo hospitalist for more than a year, answered call 24/7, with help from the community doctors whose inpatients he was following. Though he was joined eventually by the group’s second hospitalist, Suneetha Kammila, MD, chaos reigned for the next year. They hired a third hospitalist and eventually grew to five physicians and moved from call to shifts. By the third year, SNHMC had 10 hospitalists—two teams of five—and moved to the seven days on/seven days off schedule everyone wanted. The tenacity of HMG leaders Dr. Fulton and Dr. Kammila allowed the group to survive its early scheduling hardships.

The “If We Were Cars, We’d Be Benzes or Beemers Award” goes to the Colorado Kaiser-Permanente hospitalists in Denver. Part of an organization that prides itself on perfecting processes and improving transparency in healthcare, this group had all the tools to get their scheduling right. They started with the widely used seven on/seven off schedule but found it dissatisfying both personally and professionally. Through consensus, they arrived at a schedule of six consecutive eight-hour days of rounding with one triage physician handling after-hours call. There are two hospitalists on-site, 24 hours a day, seven days a week, and they admit and cross-cover after 4 p.m.

The “Planning Is Everything Award” goes to the Brockie Hospitalist Group in York, Pa. Both the hospital and the city of York are in a sustained growth mode. There are several large outpatient practices waiting for Brockie’s hospitalist group to assume their inpatients. The 18 hospitalists have wisely demurred, allowing their office-based colleagues to turn over the inpatient work only when the hospitalists can handle the additional load. Hospitalists choose either a 132-hour or a 147-hour schedule that is divided into blocks over three weeks, with a productivity/incentive program that changes as the increasing workload dictates.

The “Scheduling Is a Piece of Cake Award” goes out to Scott Oxenhandler, MD, chief hospitalist at Hollywood Memorial Hospital in Florida. Dr. Oxenhandler left an office practice for the hospitalist’s chance to practice acute care medicine with good compensation and benefits, reduced paperwork, and a great schedule. He recruited 21 hospitalists. Most work an 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. schedule, while a nocturnist covers the hours from 8 p.m. to 8 a.m. Ten physicians handle the 5 to 8 p.m. “short call” four times a month. The large number of hospitalists allows flexibility in scheduling to accommodate individual needs.

The “We Grew Past Our Mistakes Award” has been earned by Presbyterian Inpatient Care Systems in Charlotte, N.C. This program started as a two-physician, 5 p.m. to 7 a.m. admitting service for community physicians too busy to cover call. The hospitalists quit, wanting more out of medicine than an admitting service. Four hospitalists who were committed to providing inpatient care replaced them, with better results. The group now has more than 30 physicians working 12-hour shifts and co-managing, with sub-specialists, complex care. A nocturnist, working an eight-hour shift instead of the 12-hour shift that burned out a predecessor, covers night admissions and call.

Tighter Times?

Could the days of hospitalists fretting about work/life balance and optimal schedules be drawing to an end, as hospitals cast a jaundiced eye on the value hospitalists create versus what they cost? Chris Nussbaum, MD, CEO of Synergy Medical Group, based in Brandon, Fla., thinks so. He employs 10 hospitalists who cover six Tampa-area hospitals located within 15 minutes of each other. The group just switched from call to a 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. shift schedule. Dr. Nussbaum deploys hospitalists based on each hospital’s average daily census, so a doctor could cover several hospitals a day.

On an average day, eight hospitalists work days, one works the night shift, and one is off. Dr. Nussbaum’s rationale: “We’re very aggressive about time management. Our first year docs earn a base salary of $200,000, with $40,000 in productivity bonuses.” He adds, “I believe hospitalist medicine is moving in the direction we’ve taken. Scheduling is critical, and hospitalists need to work harder and be entrepreneurial. … In today’s market, prima donna docs command high salaries and have an ADC of 10 patients. That will change soon as supply catches up with demand.” TH

Marlene Piturro regularly profiles HMGs and trends in hospital medicine for The Hospitalist.