User login

Fever in hospitalized patients is a nonspecific finding with many potential causes. Blood cultures (BC) are commonly obtained prior to commencing parenteral antibiotics in febrile patients. However, as many as 35% to 50% of positive BCs represent a contamination with organisms inoculated from the skin into culture bottles at the time of sample collection.1-3 Such results represent false-positive BCs that can lead to unnecessary investigations and treatment.

Recently, Coburn et al. reviewed the severity of chills (graded on an ordinal scale) as the most useful predictor of true bacteremia (positive likelihood ratio [LR], 4.7; 95% confidence interval [CI], 3.0–7.2),4-6 and the lack of the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) criteria as the best negative indicator of true bacteremia with a negative LR of 0.09 (95% CI, 0.03-0.3).6,7 We have also previously reported normal food consumption as a negative indicator of true bacteremia, with a 98.3% negative predictive value.8 Henderson’s Basic Principles of Nursing Care emphasizes the importance of evaluating whether a patient can eat and drink adequately,9 and the evaluation of a patient’s food consumption is a routine nursing staff practice, which is treated as vital sign in Japan, in contrast to nursing practices in the United States.

However, these data were the result of a single-center retrospective study using the nursing staff’s assessment of food consumption, and they cannot be generalized to larger patient populations. Therefore, the aim of this prospective, multicenter study was to measure the accuracy of food consumption and shaking chills as predictive factors for true bacteremia.

METHODS

Study Design

This was a prospective multicenter observational study (UMIN ID: R000013768) involving 3 hospitals in Tokyo, Japan, that enrolled consecutive patients who had BCs obtained. This study was approved by the ethical committee at Juntendo University Nerima Hospital and each of the participating centers, and the study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki 1971, as revised in 1983. We evaluated 2,792 consecutive hospitalized patients (mean age, 68.9 ± 17.1 years; 55.3% men) who had BCs obtained between April 2013 and August 2014, inclusive. The indication for BC acquisition was at the discretion of the treating physician. The study protocol and the indication for BCs are described in detail elsewhere.8 We excluded patients with anorexia-inducing conditions such as gastrointestinal disease, including gastrointestinal bleeding, enterocolitis, gastric ulceration, peritonitis, appendicitis, cholangitis, pancreatitis, diverticulitis, and ischemic colitis. We also excluded patients receiving chemotherapy for malignancy. In this study, true bacteremia was defined as identical organisms isolated from 2 sets of blood cultures (a set refers to one aerobic bottle and one anaerobic bottle). Moreover, even if only one set of blood cultures was acquired, when the identified pathogen could account for the clinical presentation, we also defined this as true bacteremia. Briefly, contaminants were defined as organisms common to skin flora, including Bacillus species, coagulase-negative Staphylococcus, Corynebacterium species, and Micrococcus species, without isolation of an identical organism with the same antibiotic susceptibilities from another potentially infected site in a patient with incompatible clinical features and no risk factors for infection with the isolated organism. Single BCs that were positive for organisms that were unlikely to explain the patient’s symptoms were also considered as contaminants. Patients with contaminated BCs were excluded from the analyses.

Structure of Reliability Study Procedures

Nurses in the 3 different hospitals performed daily independent food consumption ratings during each patient’s stay. Interrater reliability assessments were conducted in the morning or afternoon, and none of the raters had access to the other nurses’ scores at any time. The study nurses performed simultaneous ratings during these assessments (one interacted with and rated the patient while the other observed and rated the same patient).

Prediction Variables of True Bacteremia

1. Food consumption. Assessment of food consumption has been previously described in detail.8 Briefly, we characterized the patients’ oral intake based on the meal taken immediately prior to the BCs. For example, if a fever developed at 2

2. Chills. As done previously, the physician evaluated the patient for a history of chills at the time of BCs and classified the patients into 1 of 4 grades4,5: “no chills,” the absence of any chills; “mild chills,” feeling cold, equivalent to needing an outer jacket; “moderate chills,” feeling very cold, equivalent to needing a thick blanket; and “shaking chills,” feeling extremely cold with rigors and generalized bodily shaking, even under a thick blanket. To distinguish between those patients who had shaking chills and those who did not, we divided the patients into 2 groups: the “shaking chills group” and the combination of none, mild, and moderate chills, referred to as the “negative shaking chills group.”

3. Other predictive variables. We considered the following additional predictive variables: age, gender, axillary body temperature (BT), heart rate (HR), systolic blood pressure (SBP), respiratory rate (RR), white blood cell count (WBC), and serum C-reactive protein level (CRP). These predictive variables were obtained immediately prior to the BCs. We defined SIRS based on standard criteria (HR >90 beats/m, RR >20/m, BT <36°C or >38°C, and a WBC <4 × 103 WBC/μL or >12 × 103 WBC/μL). Patients were subcategorized by age into 2 groups (≤69 years and >70 years). CRP levels were dichotomized as >10.0 mg/dL or ≤10.0 mg/dL. We reviewed the patients’ charts to determine whether they had received antibiotics. In the case of walk-in patients, we interviewed the patients regarding whether they had visited a clinic; if they had, they were questioned as to whether any antibiotic therapy had been prescribed.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables are presented as the mean with the associated standard deviation (SD). All potential variables predictive of true bacteremia are shown in Table 1. The variables were dichotomized by clinically meaningful thresholds and used as potential risk-adjusted variables. We calculated the sensitivity and specificity and positive and negative predictive value for each criterion. Multiple logistic regression analysis was used to select components that were significantly associated with true bacteremia (the level of statistical significance determined with maximum likelihood methods was set at P < .05). To visualize and quantify other aspects in the prediction of true bacteremia, a recursive partitioning analysis (RPA) was used to make a decision tree model for true bacteremia. This nonparametric regression method produces a classification tree following a series of nonsequential top-down binary splits. The tree-building process starts by considering a set of predictive variables and selects the variable that produces 2 subsets of participants with the greatest purity. Two factors are considered when splitting a node into its daughter nodes: the goodness of the split and the amount of impurity in the daughter nodes. The splitting process is repeated until further partitioning is no longer possible and the terminal nodes have been reached. Details on this method are discussed in Monte Carlo Calibration of Distributions of Partition Statistics (www.jmp.com).

Probability was considered significant at a value of P < .05. All statistical tests were 2-tailed. Statistical analyses were conducted by a physician (KI) and an independent statistician (JM) with the use of the SPSS® v.16.0 software package (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) and JMP® version 8.0.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Patients Characteristics

Two thousand seven hundred and ninety-two patients met the inclusion criteria for our study, from which 849 were excluded (see Figure 1 for flow diagram). Among the remaining 1,943 patients, there were 317 patients with positive BCs, of which 221 patients (69.7%) were considered to have true-positive BCs and 96 (30.3%) were considered to have contaminated BCs. After excluding these 96 patients, 221 patients with true bacteremia (true bacteremic group) were compared with 1,626 nonbacteremic patients (nonbacteremic group; Figure 1). The baseline characteristics of the subjects are shown in Table 1. The mean BT was 38.4 ± 1.2°C in the true bacteremic group and 37.9 ± 1.0°C in the nonbacteremic group. The mean serum CRP level was 11.6 ± 9.6 mg/dL in the true bacteremic group and 7.3 ± 6.9 mg/dL in the nonbacteremic group. In the true bacteremic group, there were 6 afebrile patients, and 27 patients without leukocytosis. The pathogens identified from the true-positive BCs were Escherichia coli (n = 59, 26.7%), including extended-spectrum beta-lactamase producing species, Staphylococcus aureus (n = 36, 16.3%), including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, and Klebsiella pneumoniae (n = 22, 10.0%; Supplemental Table 1).

The underlying clinical diagnoses in the true bacteremic group included urinary tract infection (UTI), pneumonia, abscess, catheter-related bloodstream infection (CRBSI), cellulitis, osteomyelitis, infective endocarditis (IE), chorioamnionitis, iatrogenic infection at hemodialysis puncture sites, bacterial meningitis, septic arthritis, and infection of unknown cause (Supplemental Table 2).

Interrater Reliability Testing of Food Consumption

Patients were evaluated during their hospital stays. The interrater reliability of the evaluation of food consumption was very high across all participating hospitals (Supplemental Table 3). To assess the reliability of the evaluations of food consumption, patients (separate from this main study) were selected randomly and evaluated independently by 2 nurses in 3 different hospitals. The kappa scores of agreement between the nurses at the 3 different hospitals were 0.83 (95% CI, 0.63-0.88), 0.90 (95% CI, 0.80-0.99), and 0.80 (95% CI, 0.67-0.99), respectively. The interrater reliability of food consumption evaluation by the nurses was very high at all participating hospitals.

Food Consumption

The low, moderate, and high food consumption groups consisted of 964 (52.1%), 306 (16.6%), and 577 (31.2%) patients, respectively (Table 1). Of these, 174 (18.0%), 33 (10.8%), and 14 (2.4%) patients, respectively, had true bacteremia. The presence of poor food consumption had a sensitivity of 93.7% (95% CI, 89.4%-97.9%), specificity of 34.6% (95% CI, 33.0%-36.2%), and a positive LR of 1.43 (95% CI, 1.37-1.50) for predicting true bacteremia. Conversely, the absence of poor food consumption (ie, normal food consumption) had a negative LR of 0.18 (95% CI, 0.17-0.19).

Chills

The no, mild, moderate, and shaking chills groups consisted of 1,514 (82.0%), 148 (8.0%), 53 (2.9%), and 132 (7.1%) patients, respectively (Table 1). Of these, 136 (9.0%), 25 (16.9%), 8 (15.1%), and 52 (39.4%) patients, respectively, had true bacteremia. The presence of shaking chills had a sensitivity of 23.5% (95% CI, 22.5%-24.6%), a specificity of 95.1% (95% CI, 90.7%-99.4%), and a positive LR of 4.78 (95% CI, 4.56–5.00) for predicting true bacteremia. Conversely, the absence of shaking chills had a negative LR of 0.80 (95% CI, 0.77-0.84).

Prediction Model for True Bacteremia

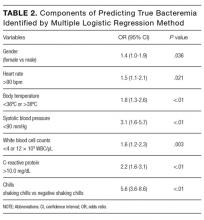

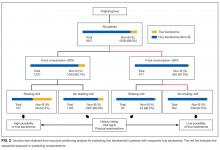

The components identified as significantly related to true bacteremia by multiple logistic regression analysis are indicated in Table 2. The significant predictors of true bacteremia were shaking chills (odds ratio [OR], 5.6; 95% CI, 3.6-8.6; P < .01), SBP <90 mmHg (OR, 3.1; 95% CI, 1.6-5.7; P < 01), CRP levels >10.0 mg/dL (OR, 2.2; 95% CI, 1.6-3.1; P < .01), BT <36°C or >38°C (OR, 1.8; 95% CI, 1.3-2.6; P < .01), WBC <4 × 103/μL or >12 × 103/μL (OR, 1.6; 95% CI, 1.2-2.3; P = .003), HR >90 bpm (OR, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.1-2.1; P = .021), and female (OR, 1.4; 95% CI, 1.0-1.9; P = .036). An RPA to create an ideal prediction model for patients with true bacteremia or nonbacteremia is shown in Figure 2. The original group consisted of 1,847 patients, including 221 patients with true bacteremia. The pretest probability of true bacteremia was 2.4% (14/577) for those with normal food consumption (Group 1) and 2.4% (13/552) for those with both normal food consumption and the absence of shaking chills (Group 2). Conversely, the pretest probability of true bacteremia was 16.3% (207/1270) for those with poor food consumption and 47.7% (51/107) for those with both poor food consumption and shaking chills. The patients with true bacteremia with normal food consumption and without shaking chills consisted of 4 cases of CRBSI and UTI, 2 cases of osteomyelitis, 1 case of IE, 1 case of chorioamnionitis, and 1 case for which the focus was unknown (Supplemental Table 4).

DISCUSSION

In this observational study, we evaluated if a simple algorithm using food consumption and shaking chills was useful for assessing whether a patient had true bacteremia. A 2-item screening checklist (nursing assessment of food consumption and shaking chills) had excellent statistical properties as a brief screening instrument for true bacteremia.

We have prospectively validated that food consumption, as assessed by nurses, is a reliable predictor of true bacteremia.8 A previous single-center retrospective study showed similar findings, but these could not be generalized across all institutions because of the limited nature of the study. In this multicenter study, we used 2 statistical methods to reduce selection bias. First, we performed a kappa analysis across the hospitals to evaluate the interrater reliability of the evaluation of food consumption. Second, we used an RPA (Figure 2), also known as a decision tree model. RPA is a step-by-step process by which a decision tree is constructed by either splitting or not splitting each node on the tree into 2 daughter nodes.10 By using this method, we successfully generated an ideal approach to predict true bacteremia using food consumption and shaking chills. After adjusting for food consumption and shaking chills, groups 1 to 2 had sequentially decreasing diagnoses of true bacteremia, varying from 221 patients to only 13 patients.

Appetite is influenced by many factors that are integrated by the brain, most importantly within the hypothalamus. Signals that impinge on the hypothalamic center include neural afferents, hormones, cytokines, and metabolites.11 These factors elicit “sickness behavior,” which includes a decrease in food-motivated behavior.12 Furthermore, exposure to pathogenic bacteria increases serotonin, which has been shown to decrease metabolism in

The strengths of this study include its relatively large sample size, multicenter design, uniformity of data collection across sites, and completeness of data collection from study participants. All of these factors allowed for a robust analysis.

However, there are several limitations of this study. First, the physicians or nurses asked the patients about the presence of shaking chills when they obtained the BCs. It may be difficult for patients, especially elderly patients, to provide this information promptly and accurately. Some patients did not call the nurse when they had shaking chills, and the chills were not witnessed by a healthcare provider. However, we used a more specific definition for shaking chills: a feeling of being extremely cold with rigors and generalized bodily shaking, even under a thick blanket. Second, this algorithm is not applicable to patients with immunosuppressed states because none of the hospitals involved in this study perform bone marrow or organ transplantation. Third, although we included patients with dementia in our cohort, we did not specifically evaluate performance of the algorithm in patients with this medical condition. It is possible that the algorithm would not perform well in this subset of patients owing to their unreliable appetite and food intake. Fourth, some medications may affect appetite, leading to reduced food consumption. Although we have not considered the details of medications in this study, we found that the pretest probability of true bacteremia was low for those patients with normal food consumption regardless of whether the medication affected their appetites or not. However, the question of whether medications truly affect patients’ appetites concurrently with bacteremia would need to be specifically addressed in a future study.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, we have established a simple algorithm to identify patients with suspected true bacteremia who require the acquisition of blood cultures. This extremely simple model can enable physicians to make a rapid bedside estimation of the risk of true bacteremia.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Drs. H. Honda and S. Saint, and Ms. A. Okada for their helpful discussions with regard to this study; Ms. M. Takigawa for the collection of data; and Ms. T. Oguri for providing infectious disease consultation on the pathogenicity of the identified organisms.

Disclosure

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 15K19294 (to TK) and 20590840 (to KI) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science. The authors report no potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

1. Weinstein MP, Towns ML, Quartey SM et al. The clinical significance of positive blood cultures in the 1990s: a prospective comprehensive evaluation of the microbiology, epidemiology, and outcome of bacteremia and fungemia in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:584-602. PubMed

2. Strand CL, Wajsbort RR, Sturmann K. Effect of iodophor vs iodine tincture skin preparation on blood culture contamination rate. JAMA. 1993;269:1004-1006. PubMed

3. Bates DW, Goldman L, Lee TH. Contaminant blood cultures and resource utilization. The true consequences of false-positive results. JAMA. 1991;265:365-369. PubMed

4. Tokuda Y, Miyasato H, Stein GH. A simple prediction algorithm for bacteraemia in patients with acute febrile illness. QJM. 2005;98:813-820. PubMed

5. Tokuda Y, Miyasato H, Stein GH, Kishaba T. The degree of chills for risk of bacteremia in acute febrile illness. Am J Med. 2005;118:1417. PubMed

6. Coburn B, Morris AM, Tomlinson G, Detsky AS. Does this adult patient with suspected bacteremia require blood cultures? JAMA. 2012;308:502-511. PubMed

7. Shapiro NI, Wolfe RE, Wright SB, Moore R, Bates DW. Who needs a blood culture? A prospectively derived and validated prediction rule. J Emerg Med. 2008;35:255-264. PubMed

8. Komatsu T, Onda T, Murayama G, et al. Predicting bacteremia based on nurse-assessed food consumption at the time of blood culture. J Hosp Med. 2012;7:702-705. PubMed

9. Henderson V. Basic Principles of Nursing Care. 2nd ed. Silver Spring, MD: American Nurses Association; 1969.

10. Therneau T, Atkinson, EJ. An Introduction to Recursive Partitioning using the RPART Routines. Mayo Foundation 2017. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/rpart/vignettes/longintro.pdf. Accessed May 5, 2017.

11. Pavlov VA, Wang H, Czura CJ, Friedman SG, Tracey KJ. The cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway: a missing link in neuroimmunomodulation. Mol Med .2003;9:125-134. PubMed

12. Hansen MK, Nguyen KT, Fleshner M, et al. Effects of vagotomy on serum endotoxin, cytokines, and corticosterone after intraperitoneal lipopolysaccharide. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2000;278:R331-336. PubMed

13. Zhang Y, Lu H, Bargmann CI. Pathogenic bacteria induce aversive olfactory learning in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 2005;438:179-84. PubMed

14. Van Dissel JT, Schijf V, Vogtlander N, Hoogendoorn M, van’t Wout J. Implications of chills. Lancet 1998;352:374. PubMed

15. Fukui S, Uehara Y, Fujibayashi K, et al. Bacteraemia predictive factors among general medical inpatients: a retrospective cross-sectional survey in a Japanese university hospital. BMJ Open 2016;6:e010527. PubMed

Fever in hospitalized patients is a nonspecific finding with many potential causes. Blood cultures (BC) are commonly obtained prior to commencing parenteral antibiotics in febrile patients. However, as many as 35% to 50% of positive BCs represent a contamination with organisms inoculated from the skin into culture bottles at the time of sample collection.1-3 Such results represent false-positive BCs that can lead to unnecessary investigations and treatment.

Recently, Coburn et al. reviewed the severity of chills (graded on an ordinal scale) as the most useful predictor of true bacteremia (positive likelihood ratio [LR], 4.7; 95% confidence interval [CI], 3.0–7.2),4-6 and the lack of the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) criteria as the best negative indicator of true bacteremia with a negative LR of 0.09 (95% CI, 0.03-0.3).6,7 We have also previously reported normal food consumption as a negative indicator of true bacteremia, with a 98.3% negative predictive value.8 Henderson’s Basic Principles of Nursing Care emphasizes the importance of evaluating whether a patient can eat and drink adequately,9 and the evaluation of a patient’s food consumption is a routine nursing staff practice, which is treated as vital sign in Japan, in contrast to nursing practices in the United States.

However, these data were the result of a single-center retrospective study using the nursing staff’s assessment of food consumption, and they cannot be generalized to larger patient populations. Therefore, the aim of this prospective, multicenter study was to measure the accuracy of food consumption and shaking chills as predictive factors for true bacteremia.

METHODS

Study Design

This was a prospective multicenter observational study (UMIN ID: R000013768) involving 3 hospitals in Tokyo, Japan, that enrolled consecutive patients who had BCs obtained. This study was approved by the ethical committee at Juntendo University Nerima Hospital and each of the participating centers, and the study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki 1971, as revised in 1983. We evaluated 2,792 consecutive hospitalized patients (mean age, 68.9 ± 17.1 years; 55.3% men) who had BCs obtained between April 2013 and August 2014, inclusive. The indication for BC acquisition was at the discretion of the treating physician. The study protocol and the indication for BCs are described in detail elsewhere.8 We excluded patients with anorexia-inducing conditions such as gastrointestinal disease, including gastrointestinal bleeding, enterocolitis, gastric ulceration, peritonitis, appendicitis, cholangitis, pancreatitis, diverticulitis, and ischemic colitis. We also excluded patients receiving chemotherapy for malignancy. In this study, true bacteremia was defined as identical organisms isolated from 2 sets of blood cultures (a set refers to one aerobic bottle and one anaerobic bottle). Moreover, even if only one set of blood cultures was acquired, when the identified pathogen could account for the clinical presentation, we also defined this as true bacteremia. Briefly, contaminants were defined as organisms common to skin flora, including Bacillus species, coagulase-negative Staphylococcus, Corynebacterium species, and Micrococcus species, without isolation of an identical organism with the same antibiotic susceptibilities from another potentially infected site in a patient with incompatible clinical features and no risk factors for infection with the isolated organism. Single BCs that were positive for organisms that were unlikely to explain the patient’s symptoms were also considered as contaminants. Patients with contaminated BCs were excluded from the analyses.

Structure of Reliability Study Procedures

Nurses in the 3 different hospitals performed daily independent food consumption ratings during each patient’s stay. Interrater reliability assessments were conducted in the morning or afternoon, and none of the raters had access to the other nurses’ scores at any time. The study nurses performed simultaneous ratings during these assessments (one interacted with and rated the patient while the other observed and rated the same patient).

Prediction Variables of True Bacteremia

1. Food consumption. Assessment of food consumption has been previously described in detail.8 Briefly, we characterized the patients’ oral intake based on the meal taken immediately prior to the BCs. For example, if a fever developed at 2

2. Chills. As done previously, the physician evaluated the patient for a history of chills at the time of BCs and classified the patients into 1 of 4 grades4,5: “no chills,” the absence of any chills; “mild chills,” feeling cold, equivalent to needing an outer jacket; “moderate chills,” feeling very cold, equivalent to needing a thick blanket; and “shaking chills,” feeling extremely cold with rigors and generalized bodily shaking, even under a thick blanket. To distinguish between those patients who had shaking chills and those who did not, we divided the patients into 2 groups: the “shaking chills group” and the combination of none, mild, and moderate chills, referred to as the “negative shaking chills group.”

3. Other predictive variables. We considered the following additional predictive variables: age, gender, axillary body temperature (BT), heart rate (HR), systolic blood pressure (SBP), respiratory rate (RR), white blood cell count (WBC), and serum C-reactive protein level (CRP). These predictive variables were obtained immediately prior to the BCs. We defined SIRS based on standard criteria (HR >90 beats/m, RR >20/m, BT <36°C or >38°C, and a WBC <4 × 103 WBC/μL or >12 × 103 WBC/μL). Patients were subcategorized by age into 2 groups (≤69 years and >70 years). CRP levels were dichotomized as >10.0 mg/dL or ≤10.0 mg/dL. We reviewed the patients’ charts to determine whether they had received antibiotics. In the case of walk-in patients, we interviewed the patients regarding whether they had visited a clinic; if they had, they were questioned as to whether any antibiotic therapy had been prescribed.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables are presented as the mean with the associated standard deviation (SD). All potential variables predictive of true bacteremia are shown in Table 1. The variables were dichotomized by clinically meaningful thresholds and used as potential risk-adjusted variables. We calculated the sensitivity and specificity and positive and negative predictive value for each criterion. Multiple logistic regression analysis was used to select components that were significantly associated with true bacteremia (the level of statistical significance determined with maximum likelihood methods was set at P < .05). To visualize and quantify other aspects in the prediction of true bacteremia, a recursive partitioning analysis (RPA) was used to make a decision tree model for true bacteremia. This nonparametric regression method produces a classification tree following a series of nonsequential top-down binary splits. The tree-building process starts by considering a set of predictive variables and selects the variable that produces 2 subsets of participants with the greatest purity. Two factors are considered when splitting a node into its daughter nodes: the goodness of the split and the amount of impurity in the daughter nodes. The splitting process is repeated until further partitioning is no longer possible and the terminal nodes have been reached. Details on this method are discussed in Monte Carlo Calibration of Distributions of Partition Statistics (www.jmp.com).

Probability was considered significant at a value of P < .05. All statistical tests were 2-tailed. Statistical analyses were conducted by a physician (KI) and an independent statistician (JM) with the use of the SPSS® v.16.0 software package (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) and JMP® version 8.0.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Patients Characteristics

Two thousand seven hundred and ninety-two patients met the inclusion criteria for our study, from which 849 were excluded (see Figure 1 for flow diagram). Among the remaining 1,943 patients, there were 317 patients with positive BCs, of which 221 patients (69.7%) were considered to have true-positive BCs and 96 (30.3%) were considered to have contaminated BCs. After excluding these 96 patients, 221 patients with true bacteremia (true bacteremic group) were compared with 1,626 nonbacteremic patients (nonbacteremic group; Figure 1). The baseline characteristics of the subjects are shown in Table 1. The mean BT was 38.4 ± 1.2°C in the true bacteremic group and 37.9 ± 1.0°C in the nonbacteremic group. The mean serum CRP level was 11.6 ± 9.6 mg/dL in the true bacteremic group and 7.3 ± 6.9 mg/dL in the nonbacteremic group. In the true bacteremic group, there were 6 afebrile patients, and 27 patients without leukocytosis. The pathogens identified from the true-positive BCs were Escherichia coli (n = 59, 26.7%), including extended-spectrum beta-lactamase producing species, Staphylococcus aureus (n = 36, 16.3%), including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, and Klebsiella pneumoniae (n = 22, 10.0%; Supplemental Table 1).

The underlying clinical diagnoses in the true bacteremic group included urinary tract infection (UTI), pneumonia, abscess, catheter-related bloodstream infection (CRBSI), cellulitis, osteomyelitis, infective endocarditis (IE), chorioamnionitis, iatrogenic infection at hemodialysis puncture sites, bacterial meningitis, septic arthritis, and infection of unknown cause (Supplemental Table 2).

Interrater Reliability Testing of Food Consumption

Patients were evaluated during their hospital stays. The interrater reliability of the evaluation of food consumption was very high across all participating hospitals (Supplemental Table 3). To assess the reliability of the evaluations of food consumption, patients (separate from this main study) were selected randomly and evaluated independently by 2 nurses in 3 different hospitals. The kappa scores of agreement between the nurses at the 3 different hospitals were 0.83 (95% CI, 0.63-0.88), 0.90 (95% CI, 0.80-0.99), and 0.80 (95% CI, 0.67-0.99), respectively. The interrater reliability of food consumption evaluation by the nurses was very high at all participating hospitals.

Food Consumption

The low, moderate, and high food consumption groups consisted of 964 (52.1%), 306 (16.6%), and 577 (31.2%) patients, respectively (Table 1). Of these, 174 (18.0%), 33 (10.8%), and 14 (2.4%) patients, respectively, had true bacteremia. The presence of poor food consumption had a sensitivity of 93.7% (95% CI, 89.4%-97.9%), specificity of 34.6% (95% CI, 33.0%-36.2%), and a positive LR of 1.43 (95% CI, 1.37-1.50) for predicting true bacteremia. Conversely, the absence of poor food consumption (ie, normal food consumption) had a negative LR of 0.18 (95% CI, 0.17-0.19).

Chills

The no, mild, moderate, and shaking chills groups consisted of 1,514 (82.0%), 148 (8.0%), 53 (2.9%), and 132 (7.1%) patients, respectively (Table 1). Of these, 136 (9.0%), 25 (16.9%), 8 (15.1%), and 52 (39.4%) patients, respectively, had true bacteremia. The presence of shaking chills had a sensitivity of 23.5% (95% CI, 22.5%-24.6%), a specificity of 95.1% (95% CI, 90.7%-99.4%), and a positive LR of 4.78 (95% CI, 4.56–5.00) for predicting true bacteremia. Conversely, the absence of shaking chills had a negative LR of 0.80 (95% CI, 0.77-0.84).

Prediction Model for True Bacteremia

The components identified as significantly related to true bacteremia by multiple logistic regression analysis are indicated in Table 2. The significant predictors of true bacteremia were shaking chills (odds ratio [OR], 5.6; 95% CI, 3.6-8.6; P < .01), SBP <90 mmHg (OR, 3.1; 95% CI, 1.6-5.7; P < 01), CRP levels >10.0 mg/dL (OR, 2.2; 95% CI, 1.6-3.1; P < .01), BT <36°C or >38°C (OR, 1.8; 95% CI, 1.3-2.6; P < .01), WBC <4 × 103/μL or >12 × 103/μL (OR, 1.6; 95% CI, 1.2-2.3; P = .003), HR >90 bpm (OR, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.1-2.1; P = .021), and female (OR, 1.4; 95% CI, 1.0-1.9; P = .036). An RPA to create an ideal prediction model for patients with true bacteremia or nonbacteremia is shown in Figure 2. The original group consisted of 1,847 patients, including 221 patients with true bacteremia. The pretest probability of true bacteremia was 2.4% (14/577) for those with normal food consumption (Group 1) and 2.4% (13/552) for those with both normal food consumption and the absence of shaking chills (Group 2). Conversely, the pretest probability of true bacteremia was 16.3% (207/1270) for those with poor food consumption and 47.7% (51/107) for those with both poor food consumption and shaking chills. The patients with true bacteremia with normal food consumption and without shaking chills consisted of 4 cases of CRBSI and UTI, 2 cases of osteomyelitis, 1 case of IE, 1 case of chorioamnionitis, and 1 case for which the focus was unknown (Supplemental Table 4).

DISCUSSION

In this observational study, we evaluated if a simple algorithm using food consumption and shaking chills was useful for assessing whether a patient had true bacteremia. A 2-item screening checklist (nursing assessment of food consumption and shaking chills) had excellent statistical properties as a brief screening instrument for true bacteremia.

We have prospectively validated that food consumption, as assessed by nurses, is a reliable predictor of true bacteremia.8 A previous single-center retrospective study showed similar findings, but these could not be generalized across all institutions because of the limited nature of the study. In this multicenter study, we used 2 statistical methods to reduce selection bias. First, we performed a kappa analysis across the hospitals to evaluate the interrater reliability of the evaluation of food consumption. Second, we used an RPA (Figure 2), also known as a decision tree model. RPA is a step-by-step process by which a decision tree is constructed by either splitting or not splitting each node on the tree into 2 daughter nodes.10 By using this method, we successfully generated an ideal approach to predict true bacteremia using food consumption and shaking chills. After adjusting for food consumption and shaking chills, groups 1 to 2 had sequentially decreasing diagnoses of true bacteremia, varying from 221 patients to only 13 patients.

Appetite is influenced by many factors that are integrated by the brain, most importantly within the hypothalamus. Signals that impinge on the hypothalamic center include neural afferents, hormones, cytokines, and metabolites.11 These factors elicit “sickness behavior,” which includes a decrease in food-motivated behavior.12 Furthermore, exposure to pathogenic bacteria increases serotonin, which has been shown to decrease metabolism in

The strengths of this study include its relatively large sample size, multicenter design, uniformity of data collection across sites, and completeness of data collection from study participants. All of these factors allowed for a robust analysis.

However, there are several limitations of this study. First, the physicians or nurses asked the patients about the presence of shaking chills when they obtained the BCs. It may be difficult for patients, especially elderly patients, to provide this information promptly and accurately. Some patients did not call the nurse when they had shaking chills, and the chills were not witnessed by a healthcare provider. However, we used a more specific definition for shaking chills: a feeling of being extremely cold with rigors and generalized bodily shaking, even under a thick blanket. Second, this algorithm is not applicable to patients with immunosuppressed states because none of the hospitals involved in this study perform bone marrow or organ transplantation. Third, although we included patients with dementia in our cohort, we did not specifically evaluate performance of the algorithm in patients with this medical condition. It is possible that the algorithm would not perform well in this subset of patients owing to their unreliable appetite and food intake. Fourth, some medications may affect appetite, leading to reduced food consumption. Although we have not considered the details of medications in this study, we found that the pretest probability of true bacteremia was low for those patients with normal food consumption regardless of whether the medication affected their appetites or not. However, the question of whether medications truly affect patients’ appetites concurrently with bacteremia would need to be specifically addressed in a future study.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, we have established a simple algorithm to identify patients with suspected true bacteremia who require the acquisition of blood cultures. This extremely simple model can enable physicians to make a rapid bedside estimation of the risk of true bacteremia.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Drs. H. Honda and S. Saint, and Ms. A. Okada for their helpful discussions with regard to this study; Ms. M. Takigawa for the collection of data; and Ms. T. Oguri for providing infectious disease consultation on the pathogenicity of the identified organisms.

Disclosure

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 15K19294 (to TK) and 20590840 (to KI) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science. The authors report no potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

Fever in hospitalized patients is a nonspecific finding with many potential causes. Blood cultures (BC) are commonly obtained prior to commencing parenteral antibiotics in febrile patients. However, as many as 35% to 50% of positive BCs represent a contamination with organisms inoculated from the skin into culture bottles at the time of sample collection.1-3 Such results represent false-positive BCs that can lead to unnecessary investigations and treatment.

Recently, Coburn et al. reviewed the severity of chills (graded on an ordinal scale) as the most useful predictor of true bacteremia (positive likelihood ratio [LR], 4.7; 95% confidence interval [CI], 3.0–7.2),4-6 and the lack of the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) criteria as the best negative indicator of true bacteremia with a negative LR of 0.09 (95% CI, 0.03-0.3).6,7 We have also previously reported normal food consumption as a negative indicator of true bacteremia, with a 98.3% negative predictive value.8 Henderson’s Basic Principles of Nursing Care emphasizes the importance of evaluating whether a patient can eat and drink adequately,9 and the evaluation of a patient’s food consumption is a routine nursing staff practice, which is treated as vital sign in Japan, in contrast to nursing practices in the United States.

However, these data were the result of a single-center retrospective study using the nursing staff’s assessment of food consumption, and they cannot be generalized to larger patient populations. Therefore, the aim of this prospective, multicenter study was to measure the accuracy of food consumption and shaking chills as predictive factors for true bacteremia.

METHODS

Study Design

This was a prospective multicenter observational study (UMIN ID: R000013768) involving 3 hospitals in Tokyo, Japan, that enrolled consecutive patients who had BCs obtained. This study was approved by the ethical committee at Juntendo University Nerima Hospital and each of the participating centers, and the study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki 1971, as revised in 1983. We evaluated 2,792 consecutive hospitalized patients (mean age, 68.9 ± 17.1 years; 55.3% men) who had BCs obtained between April 2013 and August 2014, inclusive. The indication for BC acquisition was at the discretion of the treating physician. The study protocol and the indication for BCs are described in detail elsewhere.8 We excluded patients with anorexia-inducing conditions such as gastrointestinal disease, including gastrointestinal bleeding, enterocolitis, gastric ulceration, peritonitis, appendicitis, cholangitis, pancreatitis, diverticulitis, and ischemic colitis. We also excluded patients receiving chemotherapy for malignancy. In this study, true bacteremia was defined as identical organisms isolated from 2 sets of blood cultures (a set refers to one aerobic bottle and one anaerobic bottle). Moreover, even if only one set of blood cultures was acquired, when the identified pathogen could account for the clinical presentation, we also defined this as true bacteremia. Briefly, contaminants were defined as organisms common to skin flora, including Bacillus species, coagulase-negative Staphylococcus, Corynebacterium species, and Micrococcus species, without isolation of an identical organism with the same antibiotic susceptibilities from another potentially infected site in a patient with incompatible clinical features and no risk factors for infection with the isolated organism. Single BCs that were positive for organisms that were unlikely to explain the patient’s symptoms were also considered as contaminants. Patients with contaminated BCs were excluded from the analyses.

Structure of Reliability Study Procedures

Nurses in the 3 different hospitals performed daily independent food consumption ratings during each patient’s stay. Interrater reliability assessments were conducted in the morning or afternoon, and none of the raters had access to the other nurses’ scores at any time. The study nurses performed simultaneous ratings during these assessments (one interacted with and rated the patient while the other observed and rated the same patient).

Prediction Variables of True Bacteremia

1. Food consumption. Assessment of food consumption has been previously described in detail.8 Briefly, we characterized the patients’ oral intake based on the meal taken immediately prior to the BCs. For example, if a fever developed at 2

2. Chills. As done previously, the physician evaluated the patient for a history of chills at the time of BCs and classified the patients into 1 of 4 grades4,5: “no chills,” the absence of any chills; “mild chills,” feeling cold, equivalent to needing an outer jacket; “moderate chills,” feeling very cold, equivalent to needing a thick blanket; and “shaking chills,” feeling extremely cold with rigors and generalized bodily shaking, even under a thick blanket. To distinguish between those patients who had shaking chills and those who did not, we divided the patients into 2 groups: the “shaking chills group” and the combination of none, mild, and moderate chills, referred to as the “negative shaking chills group.”

3. Other predictive variables. We considered the following additional predictive variables: age, gender, axillary body temperature (BT), heart rate (HR), systolic blood pressure (SBP), respiratory rate (RR), white blood cell count (WBC), and serum C-reactive protein level (CRP). These predictive variables were obtained immediately prior to the BCs. We defined SIRS based on standard criteria (HR >90 beats/m, RR >20/m, BT <36°C or >38°C, and a WBC <4 × 103 WBC/μL or >12 × 103 WBC/μL). Patients were subcategorized by age into 2 groups (≤69 years and >70 years). CRP levels were dichotomized as >10.0 mg/dL or ≤10.0 mg/dL. We reviewed the patients’ charts to determine whether they had received antibiotics. In the case of walk-in patients, we interviewed the patients regarding whether they had visited a clinic; if they had, they were questioned as to whether any antibiotic therapy had been prescribed.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables are presented as the mean with the associated standard deviation (SD). All potential variables predictive of true bacteremia are shown in Table 1. The variables were dichotomized by clinically meaningful thresholds and used as potential risk-adjusted variables. We calculated the sensitivity and specificity and positive and negative predictive value for each criterion. Multiple logistic regression analysis was used to select components that were significantly associated with true bacteremia (the level of statistical significance determined with maximum likelihood methods was set at P < .05). To visualize and quantify other aspects in the prediction of true bacteremia, a recursive partitioning analysis (RPA) was used to make a decision tree model for true bacteremia. This nonparametric regression method produces a classification tree following a series of nonsequential top-down binary splits. The tree-building process starts by considering a set of predictive variables and selects the variable that produces 2 subsets of participants with the greatest purity. Two factors are considered when splitting a node into its daughter nodes: the goodness of the split and the amount of impurity in the daughter nodes. The splitting process is repeated until further partitioning is no longer possible and the terminal nodes have been reached. Details on this method are discussed in Monte Carlo Calibration of Distributions of Partition Statistics (www.jmp.com).

Probability was considered significant at a value of P < .05. All statistical tests were 2-tailed. Statistical analyses were conducted by a physician (KI) and an independent statistician (JM) with the use of the SPSS® v.16.0 software package (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) and JMP® version 8.0.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Patients Characteristics

Two thousand seven hundred and ninety-two patients met the inclusion criteria for our study, from which 849 were excluded (see Figure 1 for flow diagram). Among the remaining 1,943 patients, there were 317 patients with positive BCs, of which 221 patients (69.7%) were considered to have true-positive BCs and 96 (30.3%) were considered to have contaminated BCs. After excluding these 96 patients, 221 patients with true bacteremia (true bacteremic group) were compared with 1,626 nonbacteremic patients (nonbacteremic group; Figure 1). The baseline characteristics of the subjects are shown in Table 1. The mean BT was 38.4 ± 1.2°C in the true bacteremic group and 37.9 ± 1.0°C in the nonbacteremic group. The mean serum CRP level was 11.6 ± 9.6 mg/dL in the true bacteremic group and 7.3 ± 6.9 mg/dL in the nonbacteremic group. In the true bacteremic group, there were 6 afebrile patients, and 27 patients without leukocytosis. The pathogens identified from the true-positive BCs were Escherichia coli (n = 59, 26.7%), including extended-spectrum beta-lactamase producing species, Staphylococcus aureus (n = 36, 16.3%), including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, and Klebsiella pneumoniae (n = 22, 10.0%; Supplemental Table 1).

The underlying clinical diagnoses in the true bacteremic group included urinary tract infection (UTI), pneumonia, abscess, catheter-related bloodstream infection (CRBSI), cellulitis, osteomyelitis, infective endocarditis (IE), chorioamnionitis, iatrogenic infection at hemodialysis puncture sites, bacterial meningitis, septic arthritis, and infection of unknown cause (Supplemental Table 2).

Interrater Reliability Testing of Food Consumption

Patients were evaluated during their hospital stays. The interrater reliability of the evaluation of food consumption was very high across all participating hospitals (Supplemental Table 3). To assess the reliability of the evaluations of food consumption, patients (separate from this main study) were selected randomly and evaluated independently by 2 nurses in 3 different hospitals. The kappa scores of agreement between the nurses at the 3 different hospitals were 0.83 (95% CI, 0.63-0.88), 0.90 (95% CI, 0.80-0.99), and 0.80 (95% CI, 0.67-0.99), respectively. The interrater reliability of food consumption evaluation by the nurses was very high at all participating hospitals.

Food Consumption

The low, moderate, and high food consumption groups consisted of 964 (52.1%), 306 (16.6%), and 577 (31.2%) patients, respectively (Table 1). Of these, 174 (18.0%), 33 (10.8%), and 14 (2.4%) patients, respectively, had true bacteremia. The presence of poor food consumption had a sensitivity of 93.7% (95% CI, 89.4%-97.9%), specificity of 34.6% (95% CI, 33.0%-36.2%), and a positive LR of 1.43 (95% CI, 1.37-1.50) for predicting true bacteremia. Conversely, the absence of poor food consumption (ie, normal food consumption) had a negative LR of 0.18 (95% CI, 0.17-0.19).

Chills

The no, mild, moderate, and shaking chills groups consisted of 1,514 (82.0%), 148 (8.0%), 53 (2.9%), and 132 (7.1%) patients, respectively (Table 1). Of these, 136 (9.0%), 25 (16.9%), 8 (15.1%), and 52 (39.4%) patients, respectively, had true bacteremia. The presence of shaking chills had a sensitivity of 23.5% (95% CI, 22.5%-24.6%), a specificity of 95.1% (95% CI, 90.7%-99.4%), and a positive LR of 4.78 (95% CI, 4.56–5.00) for predicting true bacteremia. Conversely, the absence of shaking chills had a negative LR of 0.80 (95% CI, 0.77-0.84).

Prediction Model for True Bacteremia

The components identified as significantly related to true bacteremia by multiple logistic regression analysis are indicated in Table 2. The significant predictors of true bacteremia were shaking chills (odds ratio [OR], 5.6; 95% CI, 3.6-8.6; P < .01), SBP <90 mmHg (OR, 3.1; 95% CI, 1.6-5.7; P < 01), CRP levels >10.0 mg/dL (OR, 2.2; 95% CI, 1.6-3.1; P < .01), BT <36°C or >38°C (OR, 1.8; 95% CI, 1.3-2.6; P < .01), WBC <4 × 103/μL or >12 × 103/μL (OR, 1.6; 95% CI, 1.2-2.3; P = .003), HR >90 bpm (OR, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.1-2.1; P = .021), and female (OR, 1.4; 95% CI, 1.0-1.9; P = .036). An RPA to create an ideal prediction model for patients with true bacteremia or nonbacteremia is shown in Figure 2. The original group consisted of 1,847 patients, including 221 patients with true bacteremia. The pretest probability of true bacteremia was 2.4% (14/577) for those with normal food consumption (Group 1) and 2.4% (13/552) for those with both normal food consumption and the absence of shaking chills (Group 2). Conversely, the pretest probability of true bacteremia was 16.3% (207/1270) for those with poor food consumption and 47.7% (51/107) for those with both poor food consumption and shaking chills. The patients with true bacteremia with normal food consumption and without shaking chills consisted of 4 cases of CRBSI and UTI, 2 cases of osteomyelitis, 1 case of IE, 1 case of chorioamnionitis, and 1 case for which the focus was unknown (Supplemental Table 4).

DISCUSSION

In this observational study, we evaluated if a simple algorithm using food consumption and shaking chills was useful for assessing whether a patient had true bacteremia. A 2-item screening checklist (nursing assessment of food consumption and shaking chills) had excellent statistical properties as a brief screening instrument for true bacteremia.

We have prospectively validated that food consumption, as assessed by nurses, is a reliable predictor of true bacteremia.8 A previous single-center retrospective study showed similar findings, but these could not be generalized across all institutions because of the limited nature of the study. In this multicenter study, we used 2 statistical methods to reduce selection bias. First, we performed a kappa analysis across the hospitals to evaluate the interrater reliability of the evaluation of food consumption. Second, we used an RPA (Figure 2), also known as a decision tree model. RPA is a step-by-step process by which a decision tree is constructed by either splitting or not splitting each node on the tree into 2 daughter nodes.10 By using this method, we successfully generated an ideal approach to predict true bacteremia using food consumption and shaking chills. After adjusting for food consumption and shaking chills, groups 1 to 2 had sequentially decreasing diagnoses of true bacteremia, varying from 221 patients to only 13 patients.

Appetite is influenced by many factors that are integrated by the brain, most importantly within the hypothalamus. Signals that impinge on the hypothalamic center include neural afferents, hormones, cytokines, and metabolites.11 These factors elicit “sickness behavior,” which includes a decrease in food-motivated behavior.12 Furthermore, exposure to pathogenic bacteria increases serotonin, which has been shown to decrease metabolism in

The strengths of this study include its relatively large sample size, multicenter design, uniformity of data collection across sites, and completeness of data collection from study participants. All of these factors allowed for a robust analysis.

However, there are several limitations of this study. First, the physicians or nurses asked the patients about the presence of shaking chills when they obtained the BCs. It may be difficult for patients, especially elderly patients, to provide this information promptly and accurately. Some patients did not call the nurse when they had shaking chills, and the chills were not witnessed by a healthcare provider. However, we used a more specific definition for shaking chills: a feeling of being extremely cold with rigors and generalized bodily shaking, even under a thick blanket. Second, this algorithm is not applicable to patients with immunosuppressed states because none of the hospitals involved in this study perform bone marrow or organ transplantation. Third, although we included patients with dementia in our cohort, we did not specifically evaluate performance of the algorithm in patients with this medical condition. It is possible that the algorithm would not perform well in this subset of patients owing to their unreliable appetite and food intake. Fourth, some medications may affect appetite, leading to reduced food consumption. Although we have not considered the details of medications in this study, we found that the pretest probability of true bacteremia was low for those patients with normal food consumption regardless of whether the medication affected their appetites or not. However, the question of whether medications truly affect patients’ appetites concurrently with bacteremia would need to be specifically addressed in a future study.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, we have established a simple algorithm to identify patients with suspected true bacteremia who require the acquisition of blood cultures. This extremely simple model can enable physicians to make a rapid bedside estimation of the risk of true bacteremia.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Drs. H. Honda and S. Saint, and Ms. A. Okada for their helpful discussions with regard to this study; Ms. M. Takigawa for the collection of data; and Ms. T. Oguri for providing infectious disease consultation on the pathogenicity of the identified organisms.

Disclosure

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 15K19294 (to TK) and 20590840 (to KI) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science. The authors report no potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

1. Weinstein MP, Towns ML, Quartey SM et al. The clinical significance of positive blood cultures in the 1990s: a prospective comprehensive evaluation of the microbiology, epidemiology, and outcome of bacteremia and fungemia in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:584-602. PubMed

2. Strand CL, Wajsbort RR, Sturmann K. Effect of iodophor vs iodine tincture skin preparation on blood culture contamination rate. JAMA. 1993;269:1004-1006. PubMed

3. Bates DW, Goldman L, Lee TH. Contaminant blood cultures and resource utilization. The true consequences of false-positive results. JAMA. 1991;265:365-369. PubMed

4. Tokuda Y, Miyasato H, Stein GH. A simple prediction algorithm for bacteraemia in patients with acute febrile illness. QJM. 2005;98:813-820. PubMed

5. Tokuda Y, Miyasato H, Stein GH, Kishaba T. The degree of chills for risk of bacteremia in acute febrile illness. Am J Med. 2005;118:1417. PubMed

6. Coburn B, Morris AM, Tomlinson G, Detsky AS. Does this adult patient with suspected bacteremia require blood cultures? JAMA. 2012;308:502-511. PubMed

7. Shapiro NI, Wolfe RE, Wright SB, Moore R, Bates DW. Who needs a blood culture? A prospectively derived and validated prediction rule. J Emerg Med. 2008;35:255-264. PubMed

8. Komatsu T, Onda T, Murayama G, et al. Predicting bacteremia based on nurse-assessed food consumption at the time of blood culture. J Hosp Med. 2012;7:702-705. PubMed

9. Henderson V. Basic Principles of Nursing Care. 2nd ed. Silver Spring, MD: American Nurses Association; 1969.

10. Therneau T, Atkinson, EJ. An Introduction to Recursive Partitioning using the RPART Routines. Mayo Foundation 2017. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/rpart/vignettes/longintro.pdf. Accessed May 5, 2017.

11. Pavlov VA, Wang H, Czura CJ, Friedman SG, Tracey KJ. The cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway: a missing link in neuroimmunomodulation. Mol Med .2003;9:125-134. PubMed

12. Hansen MK, Nguyen KT, Fleshner M, et al. Effects of vagotomy on serum endotoxin, cytokines, and corticosterone after intraperitoneal lipopolysaccharide. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2000;278:R331-336. PubMed

13. Zhang Y, Lu H, Bargmann CI. Pathogenic bacteria induce aversive olfactory learning in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 2005;438:179-84. PubMed

14. Van Dissel JT, Schijf V, Vogtlander N, Hoogendoorn M, van’t Wout J. Implications of chills. Lancet 1998;352:374. PubMed

15. Fukui S, Uehara Y, Fujibayashi K, et al. Bacteraemia predictive factors among general medical inpatients: a retrospective cross-sectional survey in a Japanese university hospital. BMJ Open 2016;6:e010527. PubMed

1. Weinstein MP, Towns ML, Quartey SM et al. The clinical significance of positive blood cultures in the 1990s: a prospective comprehensive evaluation of the microbiology, epidemiology, and outcome of bacteremia and fungemia in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:584-602. PubMed

2. Strand CL, Wajsbort RR, Sturmann K. Effect of iodophor vs iodine tincture skin preparation on blood culture contamination rate. JAMA. 1993;269:1004-1006. PubMed

3. Bates DW, Goldman L, Lee TH. Contaminant blood cultures and resource utilization. The true consequences of false-positive results. JAMA. 1991;265:365-369. PubMed

4. Tokuda Y, Miyasato H, Stein GH. A simple prediction algorithm for bacteraemia in patients with acute febrile illness. QJM. 2005;98:813-820. PubMed

5. Tokuda Y, Miyasato H, Stein GH, Kishaba T. The degree of chills for risk of bacteremia in acute febrile illness. Am J Med. 2005;118:1417. PubMed

6. Coburn B, Morris AM, Tomlinson G, Detsky AS. Does this adult patient with suspected bacteremia require blood cultures? JAMA. 2012;308:502-511. PubMed

7. Shapiro NI, Wolfe RE, Wright SB, Moore R, Bates DW. Who needs a blood culture? A prospectively derived and validated prediction rule. J Emerg Med. 2008;35:255-264. PubMed

8. Komatsu T, Onda T, Murayama G, et al. Predicting bacteremia based on nurse-assessed food consumption at the time of blood culture. J Hosp Med. 2012;7:702-705. PubMed

9. Henderson V. Basic Principles of Nursing Care. 2nd ed. Silver Spring, MD: American Nurses Association; 1969.

10. Therneau T, Atkinson, EJ. An Introduction to Recursive Partitioning using the RPART Routines. Mayo Foundation 2017. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/rpart/vignettes/longintro.pdf. Accessed May 5, 2017.

11. Pavlov VA, Wang H, Czura CJ, Friedman SG, Tracey KJ. The cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway: a missing link in neuroimmunomodulation. Mol Med .2003;9:125-134. PubMed

12. Hansen MK, Nguyen KT, Fleshner M, et al. Effects of vagotomy on serum endotoxin, cytokines, and corticosterone after intraperitoneal lipopolysaccharide. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2000;278:R331-336. PubMed

13. Zhang Y, Lu H, Bargmann CI. Pathogenic bacteria induce aversive olfactory learning in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 2005;438:179-84. PubMed

14. Van Dissel JT, Schijf V, Vogtlander N, Hoogendoorn M, van’t Wout J. Implications of chills. Lancet 1998;352:374. PubMed

15. Fukui S, Uehara Y, Fujibayashi K, et al. Bacteraemia predictive factors among general medical inpatients: a retrospective cross-sectional survey in a Japanese university hospital. BMJ Open 2016;6:e010527. PubMed

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine