User login

Persistent gender disparities exist in pay,1,2 leadership opportunities,3,4 promotion,5 and speaking opportunities.6 While the gender distribution of the hospitalist workforce may be approaching parity,3,7,8 gender differences in leadership, speakership, and authorship have already been noted in hospital medicine.3 Between 2006 and 2012, women constituted less than a third (26%) of the presenters at the national conferences of the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) and the Society of General Internal Medicine (SGIM).3

The SHM Annual Meeting has historically had an “open call” peer review process for workshop presenters with the goal of increasing the diversity of presenters. In 2019, this process was expanded to include didactic speakers. Our aim in this study was to assess whether these open call procedures resulted in improved representation of women speakers and how the proportion of women speakers affects the overall evaluation scores of the conference. Our hypothesis was that the introduction of an open call process for the SHM conference didactic speakers would be associated with an increased proportion of women speakers, compared with the closed call processes, without a negative impact on conference scores.

METHODS

The study is a retrospective evaluation of data collected regarding speakers at the annual SHM conference from 2015 to 2019. The SHM national conference typically has two main types of offerings: workshops and didactics. Workshop presenters from 2015 to 2019 were selected via an open call process as defined below. Didactic speakers (except for plenary speakers) were selected using the open call process for 2019 only.

We aimed to compare (1) the number and proportion of women speakers, compared with men speakers, over time and (2) the proportion of women speakers when open call processes were utilized versus that seen with closed call processes. Open call included workshops for all years and didactics for 2019; closed call included didactics for 2015 to 2018 and plenary sessions 2015 to 2019 (Table). The speaker list for the conferences was obtained from conference pamphlets or agendas available via Internet searches or obtained through attendance at the conference.

Speaker Categories and Identification Process

We determined whether each individual was a featured speaker (one whose talk was unopposed by other sessions), plenary speaker (defined as such in the conference pamphlets), whether they spoke in a group format, and whether the speaking opportunity type was a workshop or a didactic session. Numbers of featured and plenary speakers were combined because of low numbers. SHM provided deidentified conference evaluation data for each year studied. For the purposes of this study, we analyzed all speakers which included physicians, advanced practice providers, and professionals such as nurses and other interdisciplinary team members. The same speaker could be included multiple times if they had multiple speaking opportunities.

Open Call Process

We defined the “open call process” (referred to as “open call” here forward) as the process utilized by SHM that includes the following two components: (1) advertisements to members of SHM and to the medical community at large through a variety of mechanisms including emails, websites, and social media outlets and (2) an online submission process that includes names of proposed speakers and their topic and, in the case of workshops, session objectives as well as an outline of the proposed workshop. SHM committees may also submit suggestions for topics and speakers. Annual Conference Committee members then review and rate submissions on the categories of topic, organization and clarity, objectives, and speaker qualifications (with a focus on institutional, geographic, and gender diversity). Scores are assigned from 1 to 5 (with 5 being the best score) for each category and a section for comments is available. All submissions are also evaluated by the course director.

After initial committee reviews, scores with marked reviewer discrepancies are rereviewed and discussed by the committee and course director. A cutoff score is then calculated with proposals falling below the cutoff threshold omitted from further consideration. Weekly calls are then focused on subcategories (ie tracks) with emphasis on clinical and educational content. Each of the tracks have a subcommittee with track leads to curate the best content first and then focus on final speaker selection. More recently, templates are shared with the track leads that include a location to call out gender and institutional diversity. Weekly calls are held to hone the content and determine the speakers.

For the purposes of this study, when the above process was not used, the authors refer to it as “closed call.” Closed call processes do not typically involve open invitations or a peer review process. (Table)

Gender

Gender was assigned based on the speaker’s self-identification by the pronouns used in their biography submitted to the conference or on their institutional website or other websites where the speaker was referenced. Persons using she/her/hers pronouns were noted as women and persons using he/him/his were noted as men. For the purposes of this study, we conceptualized gender as binary (ie woman/man) given the limited information we had from online sources.

ANALYSIS

REDCap, a secure, Web-based application for building and managing online survey and databases, was used to collect and manage all study data.9

All analyses were performed using SAS Enterprise Guide 8.1 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina) using retrospectively collected data. A Cochran-Armitage test for trend was used to evaluate the proportion of women speakers from 2015 to 2019. A chi-square test was used to assess the proportion of women speakers for open call processes versus that seen with closed call. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to evaluate annual conference evaluation scores from 2015 to 2019. Either numbers with proportions or means with standard deviations have been reported. Bonferroni’s correction for multiple comparisons was applied, with a P < .008 considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Between 2015 and 2019, a total of 709 workshop and didactic presentations were given by 1,261 speakers at the annual Society of Hospital Medicine Conference. Of these, 505 (40%) were women; 756 (60%) were men. There were no missing data.

From 2015 to 2019, representation of women speakers increased from 35% of all speakers to 47% of all speakers (P = .0068). Women plenary speakers increased from 23% in 2015 to 45% in 2019 (P = .0396).

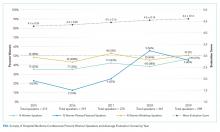

The proportion of women presenters for workshops (which have utilized an open call process throughout the study period), ranged from 43% to 53% from 2015 to 2019 with no statistically significant difference in gender distribution across years (Figure).

A greater proportion of speakers selected by an open call process were women compared to when speakers were selected by a closed call process (261 (47%) vs 244 (34%); P < .0001).

Of didactics or workshops given in a group format (N = 299), 82 (27%) were given by all-men groups and 38 (13%) were given by all-women groups. Women speakers participating in all-women group talks accounted for 21% of all women speakers; whereas men speakers participating in all-men group talks account for 26% of all men speakers (P = .02). We found that all-men group speaking opportunities did decrease from 41% of group talks in 2015 to 21% of group talks in 2019 (P = .0065).

We saw an average 3% annual increase in women speakers from 2015 to 2019, an 8% increase from 2018 to 2019 for all speakers, and an 11% increase in women speakers specific to didactic sessions. Overall conference ratings increased from a mean of 4.3 ± 0.24 in 2015 to a mean of 4.6 ± 0.14 in 2019 (n = 1,202; P < .0001; Figure).

DISCUSSION

The important findings of this study are that there has been an increase in women speakers over the last 5 years at the annual Society of Hospital Medicine Conference, that women had higher representation as speakers when open call processes were followed, and that conference scores continued to improve during the time frame studied. These findings suggest that a systematic open call process helps to support equitable speaking opportunities for men and women at a national hospital medicine conference without a negative impact on conference quality.

To recruit more diverse speakers, open call and peer review processes were used in addition to deliberate efforts at ensuring diversity in speakers. We found that over time, the proportion of women with speaking opportunities increased from 2015 to 2019. Interestingly, workshops, which had open call processes in place for the duration of the study period, had almost equal numbers of men and women presenting in all years. We also found that the number of all-men speaking groups decreased between 2015 and 2019.

A single process change can impact gender equity, but the target of true equity is expected to require additional measures such as assessment of committee structures and diversity, checklists, and reporting structures (data analysis and plans when goals not achieved).10-13 For instance, the American Society for Microbiology General Meeting was able to achieve gender equity in speakers by a multifold approach including ensuring the program committee was aware of gender statistics, increasing female representation among session convener teams, and direct instruction to try to avoid all-male sessions.11

It is important to acknowledge that these processes do require valuable resources including time. SHM has historically used committee volunteers to conduct the peer review process with each committee member reviewing 20 to 30 workshop submissions and 30 to 50 didactic sessions. While open processes with peer review seem to generate improved gender equity, ensuring processes are in place during the selection process is also key.

Several recent notable efforts to enhance gender equity and to increase diversity have been proposed. One such example of a process that may further improve gender equity was proposed by editors at the Journal of Hospital Medicine to assess current representation via demographics including gender, race, and ethnicity of authors with plans to assess patterns in the coming years.14 The American College of Physicians also published a position paper on achieving gender equity with a recommendation that organizational policies and procedures should be implemented that address implicit bias.15

Our study showed that, from 2015 to 2019, conference evaluations saw a significant increase in the score concurrently with the rise in proportion of women speakers. This finding suggests that quality does not seem to be affected by this new methodology for speaker selection and in fact this methodology may actually help improve the overall quality of the conference. To our knowledge, this is one of the first studies to concurrently evaluate speaker gender equity with conference quality.

Our study offers several strengths. This study took a pragmatic approach to understanding how processes can impact gender equity, and we were able to take advantage of the evolution of the open call system (ie workshops which have been an open call process for the duration of the study versus speaking opportunities that were not).

Our study also has several limitations. First, this study is retrospective in nature and thus other processes could have contributed to the improved gender equity, such as an organization’s priorities over time. During this study period, the SHM conference saw an average 3% increase annually in women speakers and an increase of 8% from 2018 to 2019 for all speakers compared to national trends of approximately 1%,6 which suggests that the open call processes in place could be contributing to the overall increases seen. Similarly, because of the retrospective nature of the study, we cannot be certain that the improvements in conference scores were directly the result of improved gender equity, although it does suggest that the improvements in gender equity did not have an adverse impact on the scores. We also did not assess how the composition of selection committee members for the meeting could have impacted the overall composition of the speakers. Our study looked at diversity only from the perspective of gender in a binary fashion, and thus additional studies are needed to assess how to improve diversity overall. It is unclear how this new open call for speakers affects race and ethnic diversity specifically. Identifying gender for the purposes of this study was facilitated by speakers providing their own biographies and the respective pronouns used in those biographies, and thus gender was easier to ascertain than race and ethnicity, which are not as readily available. For organizations to understand their diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts, enhancing the ability to fairly track and measure diversity will be key. Lastly, understanding of the exact composition of hospitalists from both a gender and race/ethnicity perspective is lacking. Studies have suggested that, based upon those surveyed or studied, there is a fairly equal balance of men and women albeit in academic groups.3

CONCLUSIONS

An open call approach to speakers at a national hospitalist conference seems to have contributed to improvements regarding gender equity in speaking opportunities with a concurrent improvement in overall rating of the conference. The open call system is a potential mechanism that other institutions and organizations could employ to enhance their diversity efforts.

Acknowledgments

Society of Hospital Medicine Diversity, Equity, Inclusion Special Interest Group

Work Group for SPEAK UP: Marisha Burden, MD, Daniel Cabrera, MD, Amira del Pino-Jones, MD, Areeba Kara, MD, Angela Keniston, MSPH, Keshav Khanijow, MD, Flora Kisuule, MD, Chiara Mandel, Benji Mathews, MD, David Paje, MD, Stephan Papp, MD, Snehal Patel, MD, Suchita Shah Sata, MD, Dustin Smith, MD, Kevin Vuernick

1. Weaver AC, Wetterneck TB, Whelan CT, Hinami K. A matter of priorities? Exploring the persistent gender pay gap in hospital medicine. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(8):486-490. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2400.

2. Jena AB, Olenski AR, Blumenthal DM. Sex differences in physician salary in US public medical schools. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(9):1294-1304. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.3284.

3. Burden M, Frank MG, Keniston A, et al. Gender disparities in leadership and scholarly productivity of academic hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(8):481-485. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2340.

4. Silver JK, Ghalib R, Poorman JA, et al. Analysis of gender equity in leadership of physician-focused medical specialty societies, 2008-2017. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(3):433-435. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.5303.

5. Jena AB, Khullar D, Ho O, Olenski AR, Blumenthal DM. Sex differences in academic rank in US medical schools in 2014. JAMA. 2015;314(11):1149-1158. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.10680.

6. Ruzycki SM, Fletcher S, Earp M, Bharwani A, Lithgow KC. Trends in the Proportion of Female Speakers at Medical Conferences in the United States and in Canada, 2007 to 2017. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(4):e192103. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.2103

7. Reid MB, Misky GJ, Harrison RA, Sharpe B, Auerbach A, Glasheen JJ. Mentorship, productivity, and promotion among academic hospitalists. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(1):23-27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-011-1892-5.

8. Today’s Hospitalist 2018 Compensation and Career Survey Results. https://www.todayshospitalist.com/salary-survey-results/. Accessed September 28, 2019.

9. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377-381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010.

10. Burden M, del Pino-Jones A, Shafer M, Sheth S, Rexrode K. Association of American Medical Colleagues (AAMC) Group on Women in Medicine and Science. Recruitment Toolkit: https://www.aamc.org/download/492864/data/equityinrecruitmenttoolkit.pdf. Accessed July 27, 2019.

11. Casadevall A. Achieving speaker gender equity at the american society for microbiology general meeting. MBio. 2015;6:e01146. https://doi.org/10.1128/mBio.01146-15.

12. Westring A, McDonald JM, Carr P, Grisso JA. An integrated framework for gender equity in academic medicine. Acad Med. 2016;91(8):1041-1044. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001275.

13. Martin JL. Ten simple rules to achieve conference speaker gender balance. PLoS Comput Biol. 2014;10(11):e1003903. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003903.

14. Shah SS, Shaughnessy EE, Spector ND. Leading by example: how medical journals can improve representation in academic medicine. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(7):393. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3247.

15. Butkus R, Serchen J, Moyer DV, et al. Achieving gender equity in physician compensation and career advancement: a position paper of the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2018;168:721-723. https://doi.org/10.7326/M17-3438.

Persistent gender disparities exist in pay,1,2 leadership opportunities,3,4 promotion,5 and speaking opportunities.6 While the gender distribution of the hospitalist workforce may be approaching parity,3,7,8 gender differences in leadership, speakership, and authorship have already been noted in hospital medicine.3 Between 2006 and 2012, women constituted less than a third (26%) of the presenters at the national conferences of the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) and the Society of General Internal Medicine (SGIM).3

The SHM Annual Meeting has historically had an “open call” peer review process for workshop presenters with the goal of increasing the diversity of presenters. In 2019, this process was expanded to include didactic speakers. Our aim in this study was to assess whether these open call procedures resulted in improved representation of women speakers and how the proportion of women speakers affects the overall evaluation scores of the conference. Our hypothesis was that the introduction of an open call process for the SHM conference didactic speakers would be associated with an increased proportion of women speakers, compared with the closed call processes, without a negative impact on conference scores.

METHODS

The study is a retrospective evaluation of data collected regarding speakers at the annual SHM conference from 2015 to 2019. The SHM national conference typically has two main types of offerings: workshops and didactics. Workshop presenters from 2015 to 2019 were selected via an open call process as defined below. Didactic speakers (except for plenary speakers) were selected using the open call process for 2019 only.

We aimed to compare (1) the number and proportion of women speakers, compared with men speakers, over time and (2) the proportion of women speakers when open call processes were utilized versus that seen with closed call processes. Open call included workshops for all years and didactics for 2019; closed call included didactics for 2015 to 2018 and plenary sessions 2015 to 2019 (Table). The speaker list for the conferences was obtained from conference pamphlets or agendas available via Internet searches or obtained through attendance at the conference.

Speaker Categories and Identification Process

We determined whether each individual was a featured speaker (one whose talk was unopposed by other sessions), plenary speaker (defined as such in the conference pamphlets), whether they spoke in a group format, and whether the speaking opportunity type was a workshop or a didactic session. Numbers of featured and plenary speakers were combined because of low numbers. SHM provided deidentified conference evaluation data for each year studied. For the purposes of this study, we analyzed all speakers which included physicians, advanced practice providers, and professionals such as nurses and other interdisciplinary team members. The same speaker could be included multiple times if they had multiple speaking opportunities.

Open Call Process

We defined the “open call process” (referred to as “open call” here forward) as the process utilized by SHM that includes the following two components: (1) advertisements to members of SHM and to the medical community at large through a variety of mechanisms including emails, websites, and social media outlets and (2) an online submission process that includes names of proposed speakers and their topic and, in the case of workshops, session objectives as well as an outline of the proposed workshop. SHM committees may also submit suggestions for topics and speakers. Annual Conference Committee members then review and rate submissions on the categories of topic, organization and clarity, objectives, and speaker qualifications (with a focus on institutional, geographic, and gender diversity). Scores are assigned from 1 to 5 (with 5 being the best score) for each category and a section for comments is available. All submissions are also evaluated by the course director.

After initial committee reviews, scores with marked reviewer discrepancies are rereviewed and discussed by the committee and course director. A cutoff score is then calculated with proposals falling below the cutoff threshold omitted from further consideration. Weekly calls are then focused on subcategories (ie tracks) with emphasis on clinical and educational content. Each of the tracks have a subcommittee with track leads to curate the best content first and then focus on final speaker selection. More recently, templates are shared with the track leads that include a location to call out gender and institutional diversity. Weekly calls are held to hone the content and determine the speakers.

For the purposes of this study, when the above process was not used, the authors refer to it as “closed call.” Closed call processes do not typically involve open invitations or a peer review process. (Table)

Gender

Gender was assigned based on the speaker’s self-identification by the pronouns used in their biography submitted to the conference or on their institutional website or other websites where the speaker was referenced. Persons using she/her/hers pronouns were noted as women and persons using he/him/his were noted as men. For the purposes of this study, we conceptualized gender as binary (ie woman/man) given the limited information we had from online sources.

ANALYSIS

REDCap, a secure, Web-based application for building and managing online survey and databases, was used to collect and manage all study data.9

All analyses were performed using SAS Enterprise Guide 8.1 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina) using retrospectively collected data. A Cochran-Armitage test for trend was used to evaluate the proportion of women speakers from 2015 to 2019. A chi-square test was used to assess the proportion of women speakers for open call processes versus that seen with closed call. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to evaluate annual conference evaluation scores from 2015 to 2019. Either numbers with proportions or means with standard deviations have been reported. Bonferroni’s correction for multiple comparisons was applied, with a P < .008 considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Between 2015 and 2019, a total of 709 workshop and didactic presentations were given by 1,261 speakers at the annual Society of Hospital Medicine Conference. Of these, 505 (40%) were women; 756 (60%) were men. There were no missing data.

From 2015 to 2019, representation of women speakers increased from 35% of all speakers to 47% of all speakers (P = .0068). Women plenary speakers increased from 23% in 2015 to 45% in 2019 (P = .0396).

The proportion of women presenters for workshops (which have utilized an open call process throughout the study period), ranged from 43% to 53% from 2015 to 2019 with no statistically significant difference in gender distribution across years (Figure).

A greater proportion of speakers selected by an open call process were women compared to when speakers were selected by a closed call process (261 (47%) vs 244 (34%); P < .0001).

Of didactics or workshops given in a group format (N = 299), 82 (27%) were given by all-men groups and 38 (13%) were given by all-women groups. Women speakers participating in all-women group talks accounted for 21% of all women speakers; whereas men speakers participating in all-men group talks account for 26% of all men speakers (P = .02). We found that all-men group speaking opportunities did decrease from 41% of group talks in 2015 to 21% of group talks in 2019 (P = .0065).

We saw an average 3% annual increase in women speakers from 2015 to 2019, an 8% increase from 2018 to 2019 for all speakers, and an 11% increase in women speakers specific to didactic sessions. Overall conference ratings increased from a mean of 4.3 ± 0.24 in 2015 to a mean of 4.6 ± 0.14 in 2019 (n = 1,202; P < .0001; Figure).

DISCUSSION

The important findings of this study are that there has been an increase in women speakers over the last 5 years at the annual Society of Hospital Medicine Conference, that women had higher representation as speakers when open call processes were followed, and that conference scores continued to improve during the time frame studied. These findings suggest that a systematic open call process helps to support equitable speaking opportunities for men and women at a national hospital medicine conference without a negative impact on conference quality.

To recruit more diverse speakers, open call and peer review processes were used in addition to deliberate efforts at ensuring diversity in speakers. We found that over time, the proportion of women with speaking opportunities increased from 2015 to 2019. Interestingly, workshops, which had open call processes in place for the duration of the study period, had almost equal numbers of men and women presenting in all years. We also found that the number of all-men speaking groups decreased between 2015 and 2019.

A single process change can impact gender equity, but the target of true equity is expected to require additional measures such as assessment of committee structures and diversity, checklists, and reporting structures (data analysis and plans when goals not achieved).10-13 For instance, the American Society for Microbiology General Meeting was able to achieve gender equity in speakers by a multifold approach including ensuring the program committee was aware of gender statistics, increasing female representation among session convener teams, and direct instruction to try to avoid all-male sessions.11

It is important to acknowledge that these processes do require valuable resources including time. SHM has historically used committee volunteers to conduct the peer review process with each committee member reviewing 20 to 30 workshop submissions and 30 to 50 didactic sessions. While open processes with peer review seem to generate improved gender equity, ensuring processes are in place during the selection process is also key.

Several recent notable efforts to enhance gender equity and to increase diversity have been proposed. One such example of a process that may further improve gender equity was proposed by editors at the Journal of Hospital Medicine to assess current representation via demographics including gender, race, and ethnicity of authors with plans to assess patterns in the coming years.14 The American College of Physicians also published a position paper on achieving gender equity with a recommendation that organizational policies and procedures should be implemented that address implicit bias.15

Our study showed that, from 2015 to 2019, conference evaluations saw a significant increase in the score concurrently with the rise in proportion of women speakers. This finding suggests that quality does not seem to be affected by this new methodology for speaker selection and in fact this methodology may actually help improve the overall quality of the conference. To our knowledge, this is one of the first studies to concurrently evaluate speaker gender equity with conference quality.

Our study offers several strengths. This study took a pragmatic approach to understanding how processes can impact gender equity, and we were able to take advantage of the evolution of the open call system (ie workshops which have been an open call process for the duration of the study versus speaking opportunities that were not).

Our study also has several limitations. First, this study is retrospective in nature and thus other processes could have contributed to the improved gender equity, such as an organization’s priorities over time. During this study period, the SHM conference saw an average 3% increase annually in women speakers and an increase of 8% from 2018 to 2019 for all speakers compared to national trends of approximately 1%,6 which suggests that the open call processes in place could be contributing to the overall increases seen. Similarly, because of the retrospective nature of the study, we cannot be certain that the improvements in conference scores were directly the result of improved gender equity, although it does suggest that the improvements in gender equity did not have an adverse impact on the scores. We also did not assess how the composition of selection committee members for the meeting could have impacted the overall composition of the speakers. Our study looked at diversity only from the perspective of gender in a binary fashion, and thus additional studies are needed to assess how to improve diversity overall. It is unclear how this new open call for speakers affects race and ethnic diversity specifically. Identifying gender for the purposes of this study was facilitated by speakers providing their own biographies and the respective pronouns used in those biographies, and thus gender was easier to ascertain than race and ethnicity, which are not as readily available. For organizations to understand their diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts, enhancing the ability to fairly track and measure diversity will be key. Lastly, understanding of the exact composition of hospitalists from both a gender and race/ethnicity perspective is lacking. Studies have suggested that, based upon those surveyed or studied, there is a fairly equal balance of men and women albeit in academic groups.3

CONCLUSIONS

An open call approach to speakers at a national hospitalist conference seems to have contributed to improvements regarding gender equity in speaking opportunities with a concurrent improvement in overall rating of the conference. The open call system is a potential mechanism that other institutions and organizations could employ to enhance their diversity efforts.

Acknowledgments

Society of Hospital Medicine Diversity, Equity, Inclusion Special Interest Group

Work Group for SPEAK UP: Marisha Burden, MD, Daniel Cabrera, MD, Amira del Pino-Jones, MD, Areeba Kara, MD, Angela Keniston, MSPH, Keshav Khanijow, MD, Flora Kisuule, MD, Chiara Mandel, Benji Mathews, MD, David Paje, MD, Stephan Papp, MD, Snehal Patel, MD, Suchita Shah Sata, MD, Dustin Smith, MD, Kevin Vuernick

Persistent gender disparities exist in pay,1,2 leadership opportunities,3,4 promotion,5 and speaking opportunities.6 While the gender distribution of the hospitalist workforce may be approaching parity,3,7,8 gender differences in leadership, speakership, and authorship have already been noted in hospital medicine.3 Between 2006 and 2012, women constituted less than a third (26%) of the presenters at the national conferences of the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) and the Society of General Internal Medicine (SGIM).3

The SHM Annual Meeting has historically had an “open call” peer review process for workshop presenters with the goal of increasing the diversity of presenters. In 2019, this process was expanded to include didactic speakers. Our aim in this study was to assess whether these open call procedures resulted in improved representation of women speakers and how the proportion of women speakers affects the overall evaluation scores of the conference. Our hypothesis was that the introduction of an open call process for the SHM conference didactic speakers would be associated with an increased proportion of women speakers, compared with the closed call processes, without a negative impact on conference scores.

METHODS

The study is a retrospective evaluation of data collected regarding speakers at the annual SHM conference from 2015 to 2019. The SHM national conference typically has two main types of offerings: workshops and didactics. Workshop presenters from 2015 to 2019 were selected via an open call process as defined below. Didactic speakers (except for plenary speakers) were selected using the open call process for 2019 only.

We aimed to compare (1) the number and proportion of women speakers, compared with men speakers, over time and (2) the proportion of women speakers when open call processes were utilized versus that seen with closed call processes. Open call included workshops for all years and didactics for 2019; closed call included didactics for 2015 to 2018 and plenary sessions 2015 to 2019 (Table). The speaker list for the conferences was obtained from conference pamphlets or agendas available via Internet searches or obtained through attendance at the conference.

Speaker Categories and Identification Process

We determined whether each individual was a featured speaker (one whose talk was unopposed by other sessions), plenary speaker (defined as such in the conference pamphlets), whether they spoke in a group format, and whether the speaking opportunity type was a workshop or a didactic session. Numbers of featured and plenary speakers were combined because of low numbers. SHM provided deidentified conference evaluation data for each year studied. For the purposes of this study, we analyzed all speakers which included physicians, advanced practice providers, and professionals such as nurses and other interdisciplinary team members. The same speaker could be included multiple times if they had multiple speaking opportunities.

Open Call Process

We defined the “open call process” (referred to as “open call” here forward) as the process utilized by SHM that includes the following two components: (1) advertisements to members of SHM and to the medical community at large through a variety of mechanisms including emails, websites, and social media outlets and (2) an online submission process that includes names of proposed speakers and their topic and, in the case of workshops, session objectives as well as an outline of the proposed workshop. SHM committees may also submit suggestions for topics and speakers. Annual Conference Committee members then review and rate submissions on the categories of topic, organization and clarity, objectives, and speaker qualifications (with a focus on institutional, geographic, and gender diversity). Scores are assigned from 1 to 5 (with 5 being the best score) for each category and a section for comments is available. All submissions are also evaluated by the course director.

After initial committee reviews, scores with marked reviewer discrepancies are rereviewed and discussed by the committee and course director. A cutoff score is then calculated with proposals falling below the cutoff threshold omitted from further consideration. Weekly calls are then focused on subcategories (ie tracks) with emphasis on clinical and educational content. Each of the tracks have a subcommittee with track leads to curate the best content first and then focus on final speaker selection. More recently, templates are shared with the track leads that include a location to call out gender and institutional diversity. Weekly calls are held to hone the content and determine the speakers.

For the purposes of this study, when the above process was not used, the authors refer to it as “closed call.” Closed call processes do not typically involve open invitations or a peer review process. (Table)

Gender

Gender was assigned based on the speaker’s self-identification by the pronouns used in their biography submitted to the conference or on their institutional website or other websites where the speaker was referenced. Persons using she/her/hers pronouns were noted as women and persons using he/him/his were noted as men. For the purposes of this study, we conceptualized gender as binary (ie woman/man) given the limited information we had from online sources.

ANALYSIS

REDCap, a secure, Web-based application for building and managing online survey and databases, was used to collect and manage all study data.9

All analyses were performed using SAS Enterprise Guide 8.1 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina) using retrospectively collected data. A Cochran-Armitage test for trend was used to evaluate the proportion of women speakers from 2015 to 2019. A chi-square test was used to assess the proportion of women speakers for open call processes versus that seen with closed call. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to evaluate annual conference evaluation scores from 2015 to 2019. Either numbers with proportions or means with standard deviations have been reported. Bonferroni’s correction for multiple comparisons was applied, with a P < .008 considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Between 2015 and 2019, a total of 709 workshop and didactic presentations were given by 1,261 speakers at the annual Society of Hospital Medicine Conference. Of these, 505 (40%) were women; 756 (60%) were men. There were no missing data.

From 2015 to 2019, representation of women speakers increased from 35% of all speakers to 47% of all speakers (P = .0068). Women plenary speakers increased from 23% in 2015 to 45% in 2019 (P = .0396).

The proportion of women presenters for workshops (which have utilized an open call process throughout the study period), ranged from 43% to 53% from 2015 to 2019 with no statistically significant difference in gender distribution across years (Figure).

A greater proportion of speakers selected by an open call process were women compared to when speakers were selected by a closed call process (261 (47%) vs 244 (34%); P < .0001).

Of didactics or workshops given in a group format (N = 299), 82 (27%) were given by all-men groups and 38 (13%) were given by all-women groups. Women speakers participating in all-women group talks accounted for 21% of all women speakers; whereas men speakers participating in all-men group talks account for 26% of all men speakers (P = .02). We found that all-men group speaking opportunities did decrease from 41% of group talks in 2015 to 21% of group talks in 2019 (P = .0065).

We saw an average 3% annual increase in women speakers from 2015 to 2019, an 8% increase from 2018 to 2019 for all speakers, and an 11% increase in women speakers specific to didactic sessions. Overall conference ratings increased from a mean of 4.3 ± 0.24 in 2015 to a mean of 4.6 ± 0.14 in 2019 (n = 1,202; P < .0001; Figure).

DISCUSSION

The important findings of this study are that there has been an increase in women speakers over the last 5 years at the annual Society of Hospital Medicine Conference, that women had higher representation as speakers when open call processes were followed, and that conference scores continued to improve during the time frame studied. These findings suggest that a systematic open call process helps to support equitable speaking opportunities for men and women at a national hospital medicine conference without a negative impact on conference quality.

To recruit more diverse speakers, open call and peer review processes were used in addition to deliberate efforts at ensuring diversity in speakers. We found that over time, the proportion of women with speaking opportunities increased from 2015 to 2019. Interestingly, workshops, which had open call processes in place for the duration of the study period, had almost equal numbers of men and women presenting in all years. We also found that the number of all-men speaking groups decreased between 2015 and 2019.

A single process change can impact gender equity, but the target of true equity is expected to require additional measures such as assessment of committee structures and diversity, checklists, and reporting structures (data analysis and plans when goals not achieved).10-13 For instance, the American Society for Microbiology General Meeting was able to achieve gender equity in speakers by a multifold approach including ensuring the program committee was aware of gender statistics, increasing female representation among session convener teams, and direct instruction to try to avoid all-male sessions.11

It is important to acknowledge that these processes do require valuable resources including time. SHM has historically used committee volunteers to conduct the peer review process with each committee member reviewing 20 to 30 workshop submissions and 30 to 50 didactic sessions. While open processes with peer review seem to generate improved gender equity, ensuring processes are in place during the selection process is also key.

Several recent notable efforts to enhance gender equity and to increase diversity have been proposed. One such example of a process that may further improve gender equity was proposed by editors at the Journal of Hospital Medicine to assess current representation via demographics including gender, race, and ethnicity of authors with plans to assess patterns in the coming years.14 The American College of Physicians also published a position paper on achieving gender equity with a recommendation that organizational policies and procedures should be implemented that address implicit bias.15

Our study showed that, from 2015 to 2019, conference evaluations saw a significant increase in the score concurrently with the rise in proportion of women speakers. This finding suggests that quality does not seem to be affected by this new methodology for speaker selection and in fact this methodology may actually help improve the overall quality of the conference. To our knowledge, this is one of the first studies to concurrently evaluate speaker gender equity with conference quality.

Our study offers several strengths. This study took a pragmatic approach to understanding how processes can impact gender equity, and we were able to take advantage of the evolution of the open call system (ie workshops which have been an open call process for the duration of the study versus speaking opportunities that were not).

Our study also has several limitations. First, this study is retrospective in nature and thus other processes could have contributed to the improved gender equity, such as an organization’s priorities over time. During this study period, the SHM conference saw an average 3% increase annually in women speakers and an increase of 8% from 2018 to 2019 for all speakers compared to national trends of approximately 1%,6 which suggests that the open call processes in place could be contributing to the overall increases seen. Similarly, because of the retrospective nature of the study, we cannot be certain that the improvements in conference scores were directly the result of improved gender equity, although it does suggest that the improvements in gender equity did not have an adverse impact on the scores. We also did not assess how the composition of selection committee members for the meeting could have impacted the overall composition of the speakers. Our study looked at diversity only from the perspective of gender in a binary fashion, and thus additional studies are needed to assess how to improve diversity overall. It is unclear how this new open call for speakers affects race and ethnic diversity specifically. Identifying gender for the purposes of this study was facilitated by speakers providing their own biographies and the respective pronouns used in those biographies, and thus gender was easier to ascertain than race and ethnicity, which are not as readily available. For organizations to understand their diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts, enhancing the ability to fairly track and measure diversity will be key. Lastly, understanding of the exact composition of hospitalists from both a gender and race/ethnicity perspective is lacking. Studies have suggested that, based upon those surveyed or studied, there is a fairly equal balance of men and women albeit in academic groups.3

CONCLUSIONS

An open call approach to speakers at a national hospitalist conference seems to have contributed to improvements regarding gender equity in speaking opportunities with a concurrent improvement in overall rating of the conference. The open call system is a potential mechanism that other institutions and organizations could employ to enhance their diversity efforts.

Acknowledgments

Society of Hospital Medicine Diversity, Equity, Inclusion Special Interest Group

Work Group for SPEAK UP: Marisha Burden, MD, Daniel Cabrera, MD, Amira del Pino-Jones, MD, Areeba Kara, MD, Angela Keniston, MSPH, Keshav Khanijow, MD, Flora Kisuule, MD, Chiara Mandel, Benji Mathews, MD, David Paje, MD, Stephan Papp, MD, Snehal Patel, MD, Suchita Shah Sata, MD, Dustin Smith, MD, Kevin Vuernick

1. Weaver AC, Wetterneck TB, Whelan CT, Hinami K. A matter of priorities? Exploring the persistent gender pay gap in hospital medicine. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(8):486-490. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2400.

2. Jena AB, Olenski AR, Blumenthal DM. Sex differences in physician salary in US public medical schools. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(9):1294-1304. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.3284.

3. Burden M, Frank MG, Keniston A, et al. Gender disparities in leadership and scholarly productivity of academic hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(8):481-485. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2340.

4. Silver JK, Ghalib R, Poorman JA, et al. Analysis of gender equity in leadership of physician-focused medical specialty societies, 2008-2017. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(3):433-435. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.5303.

5. Jena AB, Khullar D, Ho O, Olenski AR, Blumenthal DM. Sex differences in academic rank in US medical schools in 2014. JAMA. 2015;314(11):1149-1158. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.10680.

6. Ruzycki SM, Fletcher S, Earp M, Bharwani A, Lithgow KC. Trends in the Proportion of Female Speakers at Medical Conferences in the United States and in Canada, 2007 to 2017. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(4):e192103. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.2103

7. Reid MB, Misky GJ, Harrison RA, Sharpe B, Auerbach A, Glasheen JJ. Mentorship, productivity, and promotion among academic hospitalists. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(1):23-27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-011-1892-5.

8. Today’s Hospitalist 2018 Compensation and Career Survey Results. https://www.todayshospitalist.com/salary-survey-results/. Accessed September 28, 2019.

9. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377-381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010.

10. Burden M, del Pino-Jones A, Shafer M, Sheth S, Rexrode K. Association of American Medical Colleagues (AAMC) Group on Women in Medicine and Science. Recruitment Toolkit: https://www.aamc.org/download/492864/data/equityinrecruitmenttoolkit.pdf. Accessed July 27, 2019.

11. Casadevall A. Achieving speaker gender equity at the american society for microbiology general meeting. MBio. 2015;6:e01146. https://doi.org/10.1128/mBio.01146-15.

12. Westring A, McDonald JM, Carr P, Grisso JA. An integrated framework for gender equity in academic medicine. Acad Med. 2016;91(8):1041-1044. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001275.

13. Martin JL. Ten simple rules to achieve conference speaker gender balance. PLoS Comput Biol. 2014;10(11):e1003903. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003903.

14. Shah SS, Shaughnessy EE, Spector ND. Leading by example: how medical journals can improve representation in academic medicine. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(7):393. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3247.

15. Butkus R, Serchen J, Moyer DV, et al. Achieving gender equity in physician compensation and career advancement: a position paper of the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2018;168:721-723. https://doi.org/10.7326/M17-3438.

1. Weaver AC, Wetterneck TB, Whelan CT, Hinami K. A matter of priorities? Exploring the persistent gender pay gap in hospital medicine. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(8):486-490. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2400.

2. Jena AB, Olenski AR, Blumenthal DM. Sex differences in physician salary in US public medical schools. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(9):1294-1304. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.3284.

3. Burden M, Frank MG, Keniston A, et al. Gender disparities in leadership and scholarly productivity of academic hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(8):481-485. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2340.

4. Silver JK, Ghalib R, Poorman JA, et al. Analysis of gender equity in leadership of physician-focused medical specialty societies, 2008-2017. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(3):433-435. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.5303.

5. Jena AB, Khullar D, Ho O, Olenski AR, Blumenthal DM. Sex differences in academic rank in US medical schools in 2014. JAMA. 2015;314(11):1149-1158. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.10680.

6. Ruzycki SM, Fletcher S, Earp M, Bharwani A, Lithgow KC. Trends in the Proportion of Female Speakers at Medical Conferences in the United States and in Canada, 2007 to 2017. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(4):e192103. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.2103

7. Reid MB, Misky GJ, Harrison RA, Sharpe B, Auerbach A, Glasheen JJ. Mentorship, productivity, and promotion among academic hospitalists. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(1):23-27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-011-1892-5.

8. Today’s Hospitalist 2018 Compensation and Career Survey Results. https://www.todayshospitalist.com/salary-survey-results/. Accessed September 28, 2019.

9. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377-381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010.

10. Burden M, del Pino-Jones A, Shafer M, Sheth S, Rexrode K. Association of American Medical Colleagues (AAMC) Group on Women in Medicine and Science. Recruitment Toolkit: https://www.aamc.org/download/492864/data/equityinrecruitmenttoolkit.pdf. Accessed July 27, 2019.

11. Casadevall A. Achieving speaker gender equity at the american society for microbiology general meeting. MBio. 2015;6:e01146. https://doi.org/10.1128/mBio.01146-15.

12. Westring A, McDonald JM, Carr P, Grisso JA. An integrated framework for gender equity in academic medicine. Acad Med. 2016;91(8):1041-1044. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001275.

13. Martin JL. Ten simple rules to achieve conference speaker gender balance. PLoS Comput Biol. 2014;10(11):e1003903. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003903.

14. Shah SS, Shaughnessy EE, Spector ND. Leading by example: how medical journals can improve representation in academic medicine. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(7):393. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3247.

15. Butkus R, Serchen J, Moyer DV, et al. Achieving gender equity in physician compensation and career advancement: a position paper of the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2018;168:721-723. https://doi.org/10.7326/M17-3438.

© 2020 Society of Hospital Medicine