User login

Subclinical hypothyroidism (SCH) is a biochemical state in which the thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) is elevated while the free thyroxine (T4) level is normal. Overt hypothyroidism is not diagnosed until the free T4 level is decreased, regardless of the degree of TSH elevation.

The overall prevalence of SCH in iodine-rich areas is 4% to 10%, with a risk for progression to overt hypothyroidism of between 2% and 6% annually.1 The prevalence of SCH varies depending on the TSH reference range used.1 The normal reference range for TSH varies depending on the laboratory and/or the reference population surveyed, with the range likely widening with increasing age.

SCH is most common among women, the elderly, and White individuals.2 The discovery of SCH is often incidental, given that usually it is detected by laboratory findings alone without associated symptoms of overt hypothyroidism.3

The not-so-significant role of symptoms in subclinical hypothyroidism

Symptoms associated with overt hypothyroidism include constipation, dry skin, fatigue, slow thinking, poor memory, muscle cramps, weakness, and cold intolerance. In SCH, these symptoms are inconsistent, with around 1 in 3 patients having no symptoms

One study reported that roughly 18% of euthyroid individuals, 22% of SCH patients, and 26% of those with overt hypothyroidism reported 4 or more symptoms classically thought to be related to hypothyroidism.4 A large Danish cohort study found that hypothyroid symptoms were no more common in patients with SCH than in euthyroid individuals in the general population.5 These studies question the validity of attributing symptoms to SCH.

Adverse health associations

Observational data suggest that SCH is associated with an increased risk for dyslipidemia, coronary heart disease, heart failure, and cardiovascular mortality, particularly in those with TSH levels ≥ 10 mIU/L.6,7 Such associations were not found for most adults with TSH levels between 5 and 10 mIU/L.8 There are also potential associations of SCH with obesity, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis.9,10 Despite thyroid studies being commonly ordered as part of a mental health evaluation, SCH has not been statistically associated with depressive symptoms.11,12

Caveats with laboratory testing

There are several issues to consider when performing a laboratory assessment of thyroid function. TSH levels fluctuate considerably during the day, as TSH secretion has a circadian rhythm. TSH values are 50% higher at night and in the early morning than during the rest of the day.13 TSH values also may rise in response to current illness or stress. Due to this biologic variability, repeat testing to confirm TSH levels is recommended if an initial test result is abnormal.14

Continue to: An exact reference range...

An exact reference range for TSH is not widely agreed upon—although most laboratories regard 4.0 to 5.0 mIU/L as the high-end cutoff for normal. Also, “normal” TSH levels appear to differ by age. Accordingly, some experts have recommended an age-based reference range for TSH levels,15 although this is not implemented widely by laboratories. A TSH level of 6.0 mIU/L (or even higher) may be more appropriate for adults older than 65 years.1

Biotin supplementation has been shown to cause spurious thyroid testing results (TSH, T3, T4) depending on the type of assay used. Therefore, supplements containing biotin should be withheld for several days before assessing thyroid function.16Patients with SCH are often categorized as having TSH levels between 4.5 and 10 mIU/L (around 90% of patients) or levels ≥ 10 mIU/L.8,17 If followed for 5 years, approximately 60% of patients with SCH and TSH levels between 4 and 10 mIU/L will normalize without intervention.18 Normalization is less common in patients with a TSH level greater than 10 mIU/L.18

The risk for progression to overt hypothyroidism also appears to be higher for those with certain risk factors. These include higher baseline TSH levels, presence of thyroid peroxidase antibodies (TPOAbs), or history of neck irradiation or radioactive iodine uptake.1 Other risk factors for eventual thyroid dysfunction include female sex, older age, goiter, and high iodine intake.13

Evidence for treatment varies

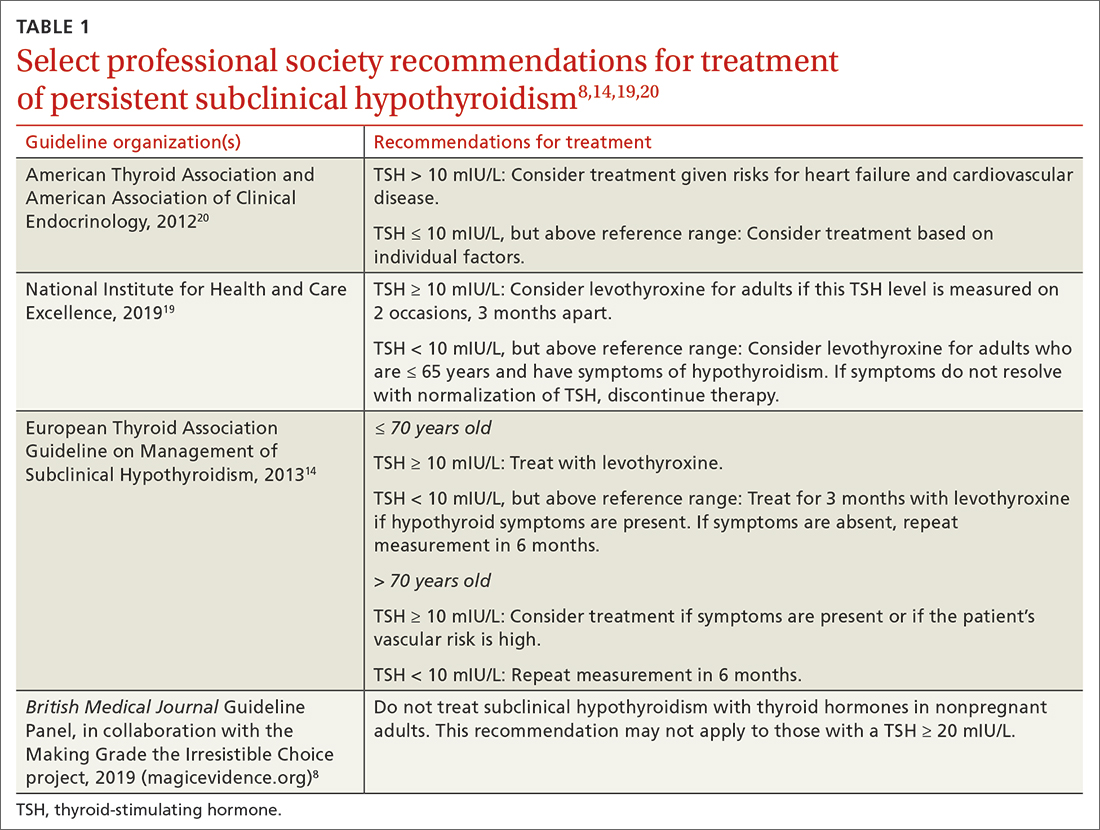

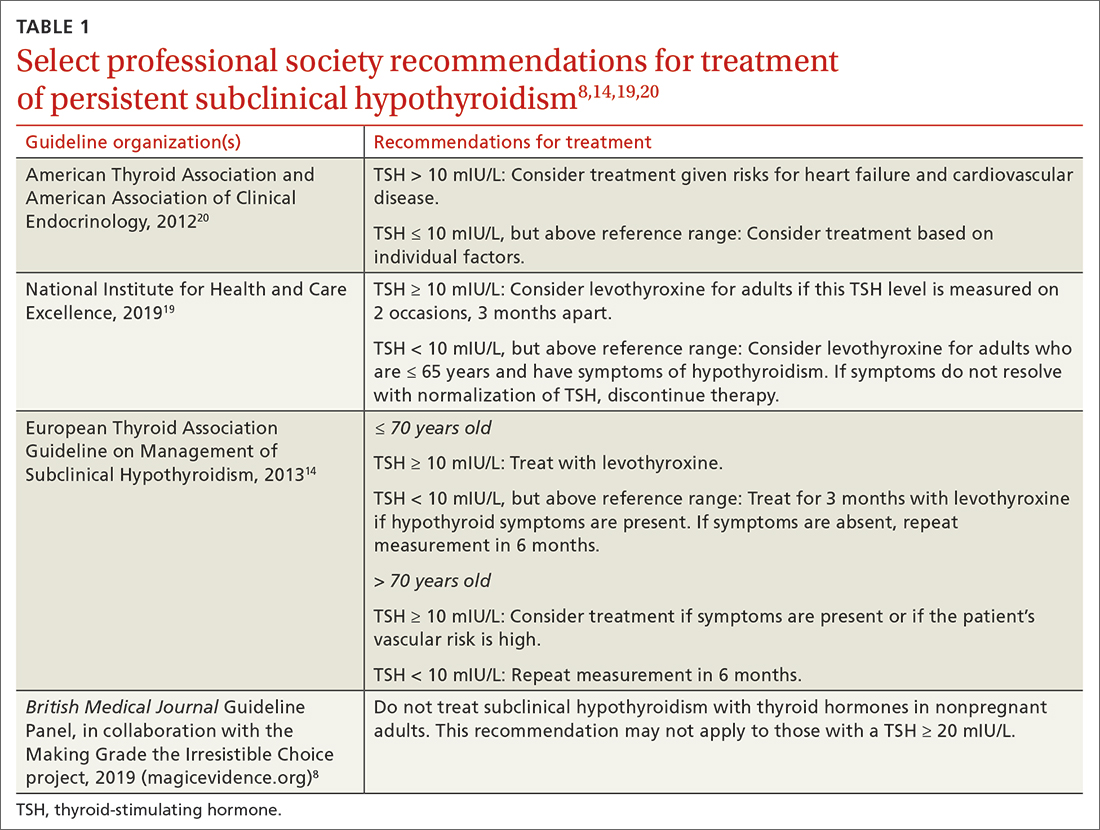

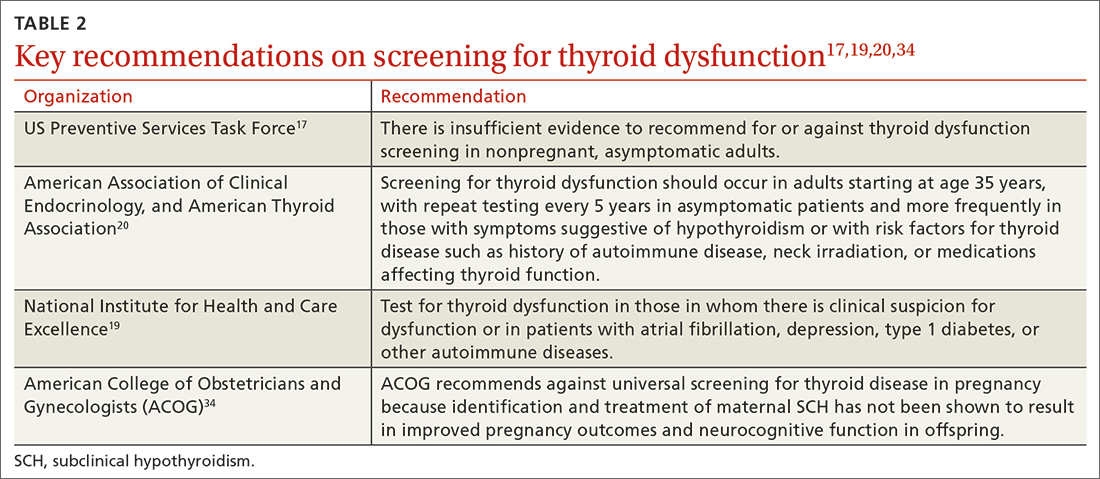

Guidelines for the treatment of SCH (TABLE 18,14,19,20) are founded on the condition’s risk for progression to overt hypothyroidism and its association with health consequences such as cardiovascular disease. Guidelines of the American Thyroid Association (ATA) and European Thyroid Association (ETA), and those of the United Kingdom–based National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), prioritize treatment for individuals with a TSH level > 10 mIU/La and for those with

There are few large RCTs of treatment outcomes for SCH. A 2017 RCT (the Thyroid Hormone Replacement for Untreated Older Adults with Subclinical Hypothyroidism, or TRUST, trial) of 737 adults older than 65 years with SCH evaluated the ability of levothyroxine to normalize TSH values compared with placebo. At 1 year, there was no difference in hypothyroid symptoms or tiredness scale scores with levothyroxine treatment compared with placebo.21 This finding was consistent even in the subgroup with a higher baseline symptom burden.22

Continue to: Two small RCTs evaluated...

Two small RCTs evaluated treatment of SCH with depressive symptoms and cognitive function, neither finding benefit compared with placebo.12,23 A 2018 systematic review and meta-analysis of 21 studies and 2192 adults did not show a benefit to quality of life or thyroid-specific symptoms in those treated for SCH compared with controls.24

RCT support also is lacking for a reduction in cardiovascular mortality following treatment for SCH. A large population-level retrospective cohort from Denmark showed no difference in cardiovascular mortality or myocardial infarction in those treated for SCH compared with controls.25 Pooled results from 2 RCTs (for patients older than 65 years, and those older than 80 years) showed no change in risk for cardiovascular outcomes in older adults treated for SCH.26 Older adults treated for SCH in the TRUST trial showed no improvements in systolic or diastolic function on echocardiography.27 Two trials showed no difference in carotid intima-media thickness with treatment of SCH compared with placebo.28,29

While most of the RCT data come from older adults, a retrospective cohort study in the United Kingdom of younger (ages 40-70 years; n = 3093) and older (age > 70 years; n = 1642) patients showed a reduction in cardiovascular mortality among treated patients who were younger (hazard ratio [HR] = 0.61; 4.2% vs. 6.6%) but not those who were older (HR = 0.99; 12.7% vs. 10.7%).30 There is also evidence that thyroid size in those with goiter can be reduced with treatment of SCH.31

A measured approach to treating subclinical hypothyroidism

Consider several factors when deciding whether to treat SCH. For instance, RCT data suggest a lack of treatment benefit in relieving depression, improving cognition, or reducing general hypothyroid symptoms. Treatment of SCH in older adults does not appear to improve cardiovascular outcomes. The question of whether long-term treatment of SCH in younger patients reduces cardiovascular morbidity or mortality lacks answers from RCTs. Before diagnosing SCH or starting treatment, always confirm SCH with repeat testing in 2 to 3 months, as a high percentage of those with untreated SCH will have normal thyroid function on repeat testing.

In the event you and your patient elect to treat SCH, guidelines and trials generally support a low initial daily dose of 25 to 50 mcg of levothyroxine (T4), followed with dose changes every 4 to 8 weeks and a goal of normalizing TSH to within the lower half of the reference range (0.4-2.5 mIU/L).14 This is generally similar to published treatment goals for primary hypothyroidism and is based on studies suggesting the lower half of the reference range is normal for young, healthy, euthyroid individuals.32 Though full replacement doses (1.6-1.8 mcg/kg of ideal body weight) can be started for those who are elderly or who have ischemic heart disease or angina, this approach should be avoided in favor of low-dose initial therapy.33 Thyroid supplements are best absorbed when taken apart from food, calcium, or iron supplements. The ATA suggests taking thyroid medication 60 minutes before breakfast or at bedtime (3 or more hours after the evening meal).33

Continue to: Screening guidelines differ

Screening guidelines differ

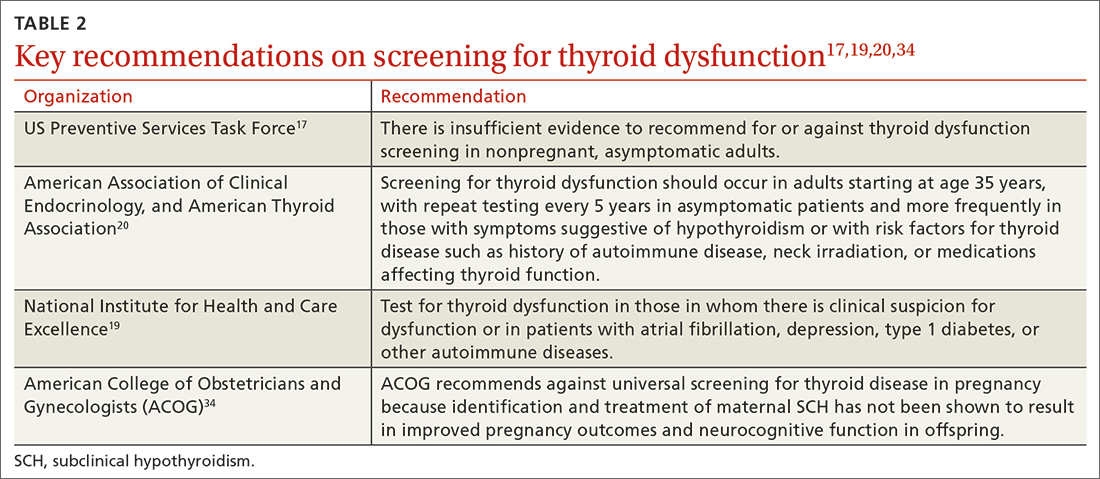

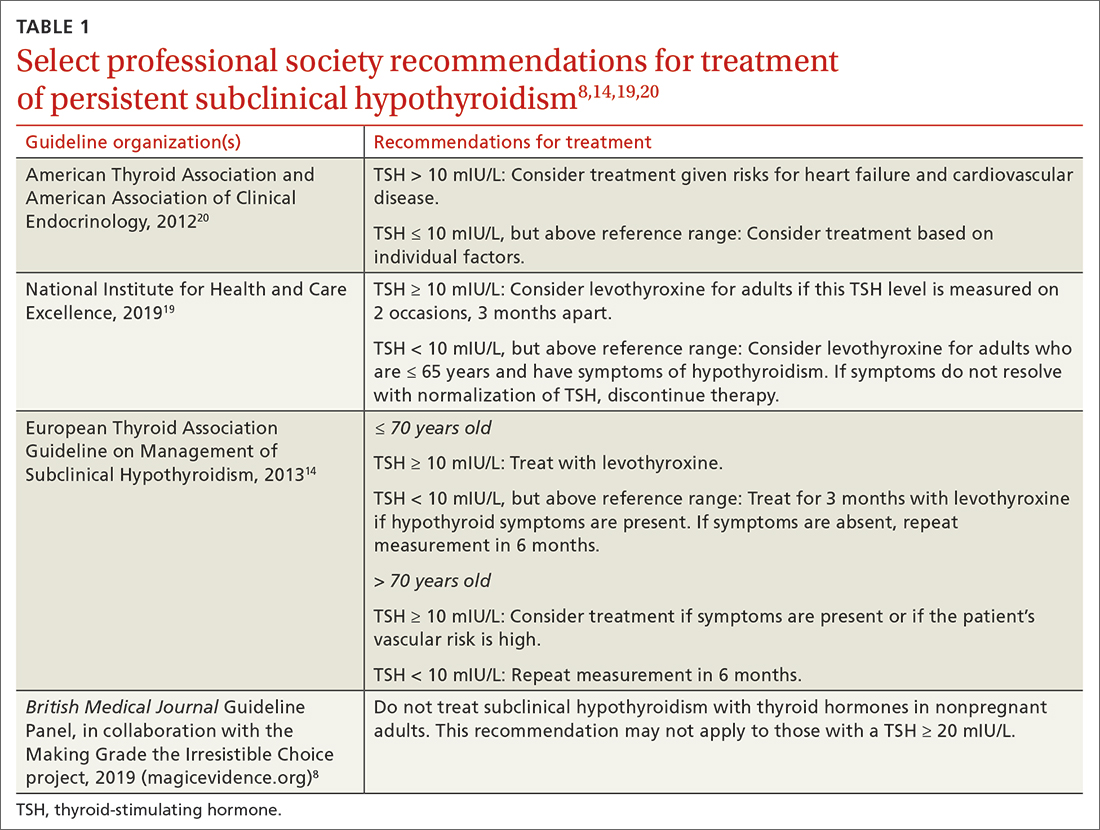

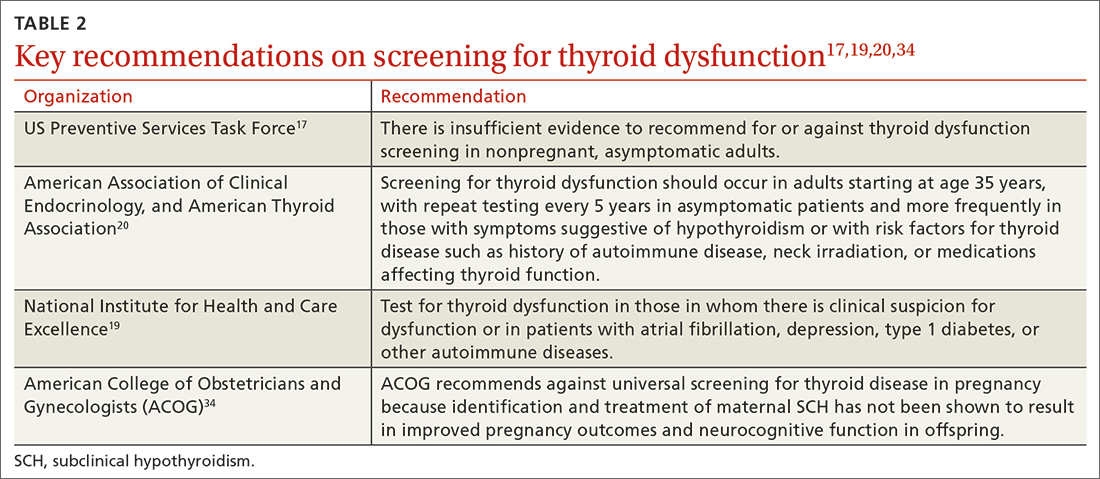

Lacking population-level screening data from RCTs, most organizations do not recommend screening for thyroid dysfunction or they note insufficient evidence to make a screening recommendation (TABLE 217,19,20,34). In their most recent recommendation statement on the subject in 2015, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) concluded the current evidence was insufficient to recommend for or against thyroid dysfunction screening in nonpregnant, asymptomatic adults.17 This differs from the ATA and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinology (AACE; formerly known as the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists), which both recommend targeted screening for thyroid dysfunction based on symptoms or risk factors.20

What about subclinical hypothyroidism in pregnancy?

Overt hypothyroidism is associated with adverse events during pregnancy and with subsequent neurodevelopmental complications in children, although the effects of SCH during pregnancy remain less certain. Concerns have been raised over the potential association of SCH with pregnancy loss, placental abruption, premature rupture of membranes, and neonatal death.35 Historically, the prevalence of SCH during pregnancy has ranged from 2% to 2.5%, but using lower trimester-based TSH reference ranges, the prevalence of SCH in pregnancy may be as high as 15%.35

Guided by a large RCT that failed to find benefit (pregnancy outcomes, neurodevelopmental outcomes in children) following treatment of SCH in pregnancy,36 the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends against routine screening for thyroid disease in pregnancy.34 The ATA notes insufficient evidence to rec-ommend universal screening for thyroid dysfunction in pregnancy but recommends targeted screening of those with risk factors.37 Data are conflicting on the benefit of treating known or recently detected SCH on pregnancy outcomes including pregnancy loss.35,38 As such, the American Society of Reproductive Medicine and the ATA both generally recommend treatment of SCH in pregnant patients, particularly when the TSH is ≥ 4.0 mIU/L and TPOAbs are present.37,39

a The ATA, ETA, and NICE have slightly different recommendations when a TSH level = 10 mIU/L. ETA and NICE recommend prioritizing treatment for individuals with this level, while ATA recommends treatment when individual factors are also considered.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors thank Family Medicine Medical Librarian Gwen Wilson, MLS, AHIP, for her assistance with literature searches.

CORRESPONDENCE

Nicholas LeFevre, MD, Family and Community Medicine, University of Missouri–Columbia School of Medicine, One Hospital Drive, M224 Medical Science Building, Columbia, MO 65212; nlefevre@health.missouri.edu

1. Reyes Domingo F, Avey MT, Doull M. Screening for thyroid dysfunction and treatment of screen-detected thyroid dysfunction in asymptomatic, community-dwelling adults: a systematic review. Syst Rev. 2019;8:260. doi: 10.1186/s13643-019-1181-7

2. Cooper DS, Biondi B. Subclinical thyroid disease. Lancet. 2012;379:1142-1154. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60276-6

3. Bauer BS, Azcoaga-Lorenzo A, Agrawal U, et al. Management strategies for patients with subclinical hypothyroidism: a protocol for an umbrella review. Syst Rev. 2021;10:290. doi: 10.1186/s13643-021-01842-y

4. Canaris GJ, Manowitz NR, Mayor G, et al. The Colorado thyroid disease prevalence study. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:526-534. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.4.526

5. Carlé A, Karmisholt JS, Knudsen N, et al. Does subclinical hypothyroidism add any symptoms? Evidence from a Danish population-based study. Am J Med. 2021;134:1115-1126.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2021.03.009

6. Gencer B, Collet TH, Virgini V, et al. Subclinical thyroid dysfunction and the risk of heart failure events: an individual participant data analysis from 6 prospective cohorts. Circulation. 2012;126:1040-1049. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.096024

7. Rodondi N, den Elzen WP, Bauer DC, et al. Subclinical hypothyroidism and the risk of coronary heart disease and mortality. JAMA. 2010;304:1365-1374. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1361

8. Bekkering GE, Agoritsas T, Lytvyn L, et al. Thyroid hormones treatment for subclinical hypothyroidism: a clinical practice guideline. BMJ. 2019;365:l2006. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l2006

9. Chung GE, Kim D, Kim W, et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease across the spectrum of hypothyroidism. J Hepatol. 2012;57:150-156. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.02.027

10. Kim D, Kim W, Joo SK, et al. Subclinical hypothyroidism and low-normal thyroid function are associated with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and fibrosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16:123-131.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.08.014

11. Kim JS, Zhang Y, Chang Y, et al. Subclinical hypothyroidism and incident depression in young and middle-age adults. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;103:1827-1833. doi: 10.1210/jc.2017-01247

12. Jorde R, Waterloo K, Storhaug H, et al. Neuropsychological function and symptoms in subjects with subclinical hypothyroidism and the effect of thyroxine treatment. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:145-53. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-1775

13. Azim S, Nasr C. Subclinical hypothyroidism: when to treat. Cleve Clin J Med. 2019;86:101-110. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.86a.17053

14. Pearce SH, Brabant G, Duntas LH, et al. 2013 ETA Guideline: Management of subclinical hypothyroidism. Eur Thyroid J. 2013;2:215-228. doi: 10.1159/000356507

15. Cappola AR. The thyrotropin reference range should be changed in older patients. JAMA. 2019;322:1961-1962. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.14728

16. Li D, Radulescu A, Shrestha RT, et al. Association of biotin ingestion with performance of hormone and nonhormone assays in healthy adults. JAMA. 2017;318:1150-1160.

17. LeFevre ML, USPSTF. Screening for thyroid dysfunction: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:641-650. doi: 10.7326/M15-0483

18. Meyerovitch J, Rotman-Pikielni P, Sherf M, et al. Serum thyrotropin measurements in the community: five-year follow-up in a large network of primary care physicians. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1533-1538. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.14.1533

19. NICE. Thyroid Disease: assessment and management (NICE guideline NG145). 2019. Accessed March 14, 2023. www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng145/resources/thyroid-disease-assessment-and-management-pdf-66141781496773

20. Garber JR, Cobin RH, Gharib H, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for hypothyroidism in adults: cosponsored by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and the American Thyroid Association. Thyroid. 2012;22:1200-1235. doi: 10.1089/thy.2012.0205

21. Stott DJ, Rodondi N, Kearney PM, et al. Thyroid hormone therapy for older adults with subclinical hypothyroidism. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:2534-2544. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1603825

22. de Montmollin M, Feller M, Beglinger S, et al. L-thyroxine therapy for older adults with subclinical hypothyroidism and hypothyroid symptoms: secondary analysis of a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172:709-716. doi: 10.7326/M19-3193

23. Parle J, Roberts L, Wilson S, et al. A randomized controlled trial of the effect of thyroxine replacement on cognitive function in community-living elderly subjects with subclinical hypothyroidism: the Birmingham Elderly Thyroid study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:3623-3632. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-2571

24. Feller M, Snel M, Moutzouri E, et al. Association of thyroid hormone therapy with quality of life and thyroid-related symptoms in patients with subclinical hypothyroidism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2018;320:1349-1359. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.13770

25. Andersen MN, Schjerning Olsen A-M, Madsen JC, et al. Levothyroxine substitution in patients with subclinical hypothyroidism and the risk of myocardial infarction and mortality. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0129793. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129793

26. Zijlstra LE, Jukema JW, Westendorp RG, et al. Levothyroxine treatment and cardiovascular outcomes in older people with subclinical hypothyroidism: pooled individual results of two randomised controlled trials. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021;12:674841. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2021.674841

27. Gencer B, Moutzouri E, Blum MR, et al. The impact of levothyroxine on cardiac function in older adults with mild subclinical hypothyroidism: a randomized clinical trial. Am J Med. 2020;133:848-856.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2020.01.018

28. Blum MR, Gencer B, Adam L, et al. Impact of thyroid hormone therapy on atherosclerosis in the elderly with subclinical hypothyroidism: a randomized trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;103:2988-2997. doi: 10.1210/jc.2018-00279

29. Aziz M, Kandimalla Y, Machavarapu A, et al. Effect of thyroxin treatment on carotid intima-media thickness (CIMT) reduction in patients with subclinical hypothyroidism (SCH): a meta-analysis of clinical trials. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2017;24:643-659. doi: 10.5551/jat.39917

30. Razvi S, Weaver JU, Butler TJ, et al. Levothyroxine treatment of subclinical hypothyroidism, fatal and nonfatal cardiovascular events, and mortality. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:811-817. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.1159

31. Romaldini JH, Biancalana MM, Figueiredo DI, et al. Effect of L-thyroxine administration on antithyroid antibody levels, lipid profile, and thyroid volume in patients with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Thyroid. 1996;6:183-188. doi: 10.1089/thy.1996.6.183

32. Biondi B, Cooper DS. The clinical significance of subclinical thyroid dysfunction. Endocr Rev. 2008;29:76-131. doi: 10.1210/er.2006-0043

33. Jonklaas J, Bianco AC, Bauer AJ, et al. Guidelines for the treatment of hypothyroidism: prepared by the american thyroid association task force on thyroid hormone replacement. Thyroid. 2014;24:1670-1751. doi: 10.1089/thy.2014.0028

34. ACOG. Thyroid disease in pregnancy: ACOG practice bulletin, Number 223. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:e261-e274. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003893

35. Maraka S, Ospina NM, O’Keeffe ET, et al. Subclinical hypothyroidism in pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thyroid. 2016;26:580-590. doi: 10.1089/thy.2015.0418

36. Casey BM, Thom EA, Peaceman AM, et al. Treatment of subclinical hypothyroidism or hypothyroxinemia in pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:815-825. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1606205

37. Alexander EK, Pearce EN, Brent FA, et al. 2017 Guidelines of the American Thyroid Association for the Diagnosis and Management of Thyroid Disease During Pregnancy and the Postpartum. Thyroid. 2017;27:315-389. doi: 10.1089/thy.2016.0457

38. Dong AC, Morgan J, Kane M, et al. Subclinical hypothyroidism and thyroid autoimmunity in recurrent pregnancy loss: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. 2020;113:587-600.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2019.11.003

39. Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Subclinical hypothyroidism in the infertile female population: a guideline. Fertil Steril. 2015;104:545-553. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.05.028

Subclinical hypothyroidism (SCH) is a biochemical state in which the thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) is elevated while the free thyroxine (T4) level is normal. Overt hypothyroidism is not diagnosed until the free T4 level is decreased, regardless of the degree of TSH elevation.

The overall prevalence of SCH in iodine-rich areas is 4% to 10%, with a risk for progression to overt hypothyroidism of between 2% and 6% annually.1 The prevalence of SCH varies depending on the TSH reference range used.1 The normal reference range for TSH varies depending on the laboratory and/or the reference population surveyed, with the range likely widening with increasing age.

SCH is most common among women, the elderly, and White individuals.2 The discovery of SCH is often incidental, given that usually it is detected by laboratory findings alone without associated symptoms of overt hypothyroidism.3

The not-so-significant role of symptoms in subclinical hypothyroidism

Symptoms associated with overt hypothyroidism include constipation, dry skin, fatigue, slow thinking, poor memory, muscle cramps, weakness, and cold intolerance. In SCH, these symptoms are inconsistent, with around 1 in 3 patients having no symptoms

One study reported that roughly 18% of euthyroid individuals, 22% of SCH patients, and 26% of those with overt hypothyroidism reported 4 or more symptoms classically thought to be related to hypothyroidism.4 A large Danish cohort study found that hypothyroid symptoms were no more common in patients with SCH than in euthyroid individuals in the general population.5 These studies question the validity of attributing symptoms to SCH.

Adverse health associations

Observational data suggest that SCH is associated with an increased risk for dyslipidemia, coronary heart disease, heart failure, and cardiovascular mortality, particularly in those with TSH levels ≥ 10 mIU/L.6,7 Such associations were not found for most adults with TSH levels between 5 and 10 mIU/L.8 There are also potential associations of SCH with obesity, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis.9,10 Despite thyroid studies being commonly ordered as part of a mental health evaluation, SCH has not been statistically associated with depressive symptoms.11,12

Caveats with laboratory testing

There are several issues to consider when performing a laboratory assessment of thyroid function. TSH levels fluctuate considerably during the day, as TSH secretion has a circadian rhythm. TSH values are 50% higher at night and in the early morning than during the rest of the day.13 TSH values also may rise in response to current illness or stress. Due to this biologic variability, repeat testing to confirm TSH levels is recommended if an initial test result is abnormal.14

Continue to: An exact reference range...

An exact reference range for TSH is not widely agreed upon—although most laboratories regard 4.0 to 5.0 mIU/L as the high-end cutoff for normal. Also, “normal” TSH levels appear to differ by age. Accordingly, some experts have recommended an age-based reference range for TSH levels,15 although this is not implemented widely by laboratories. A TSH level of 6.0 mIU/L (or even higher) may be more appropriate for adults older than 65 years.1

Biotin supplementation has been shown to cause spurious thyroid testing results (TSH, T3, T4) depending on the type of assay used. Therefore, supplements containing biotin should be withheld for several days before assessing thyroid function.16Patients with SCH are often categorized as having TSH levels between 4.5 and 10 mIU/L (around 90% of patients) or levels ≥ 10 mIU/L.8,17 If followed for 5 years, approximately 60% of patients with SCH and TSH levels between 4 and 10 mIU/L will normalize without intervention.18 Normalization is less common in patients with a TSH level greater than 10 mIU/L.18

The risk for progression to overt hypothyroidism also appears to be higher for those with certain risk factors. These include higher baseline TSH levels, presence of thyroid peroxidase antibodies (TPOAbs), or history of neck irradiation or radioactive iodine uptake.1 Other risk factors for eventual thyroid dysfunction include female sex, older age, goiter, and high iodine intake.13

Evidence for treatment varies

Guidelines for the treatment of SCH (TABLE 18,14,19,20) are founded on the condition’s risk for progression to overt hypothyroidism and its association with health consequences such as cardiovascular disease. Guidelines of the American Thyroid Association (ATA) and European Thyroid Association (ETA), and those of the United Kingdom–based National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), prioritize treatment for individuals with a TSH level > 10 mIU/La and for those with

There are few large RCTs of treatment outcomes for SCH. A 2017 RCT (the Thyroid Hormone Replacement for Untreated Older Adults with Subclinical Hypothyroidism, or TRUST, trial) of 737 adults older than 65 years with SCH evaluated the ability of levothyroxine to normalize TSH values compared with placebo. At 1 year, there was no difference in hypothyroid symptoms or tiredness scale scores with levothyroxine treatment compared with placebo.21 This finding was consistent even in the subgroup with a higher baseline symptom burden.22

Continue to: Two small RCTs evaluated...

Two small RCTs evaluated treatment of SCH with depressive symptoms and cognitive function, neither finding benefit compared with placebo.12,23 A 2018 systematic review and meta-analysis of 21 studies and 2192 adults did not show a benefit to quality of life or thyroid-specific symptoms in those treated for SCH compared with controls.24

RCT support also is lacking for a reduction in cardiovascular mortality following treatment for SCH. A large population-level retrospective cohort from Denmark showed no difference in cardiovascular mortality or myocardial infarction in those treated for SCH compared with controls.25 Pooled results from 2 RCTs (for patients older than 65 years, and those older than 80 years) showed no change in risk for cardiovascular outcomes in older adults treated for SCH.26 Older adults treated for SCH in the TRUST trial showed no improvements in systolic or diastolic function on echocardiography.27 Two trials showed no difference in carotid intima-media thickness with treatment of SCH compared with placebo.28,29

While most of the RCT data come from older adults, a retrospective cohort study in the United Kingdom of younger (ages 40-70 years; n = 3093) and older (age > 70 years; n = 1642) patients showed a reduction in cardiovascular mortality among treated patients who were younger (hazard ratio [HR] = 0.61; 4.2% vs. 6.6%) but not those who were older (HR = 0.99; 12.7% vs. 10.7%).30 There is also evidence that thyroid size in those with goiter can be reduced with treatment of SCH.31

A measured approach to treating subclinical hypothyroidism

Consider several factors when deciding whether to treat SCH. For instance, RCT data suggest a lack of treatment benefit in relieving depression, improving cognition, or reducing general hypothyroid symptoms. Treatment of SCH in older adults does not appear to improve cardiovascular outcomes. The question of whether long-term treatment of SCH in younger patients reduces cardiovascular morbidity or mortality lacks answers from RCTs. Before diagnosing SCH or starting treatment, always confirm SCH with repeat testing in 2 to 3 months, as a high percentage of those with untreated SCH will have normal thyroid function on repeat testing.

In the event you and your patient elect to treat SCH, guidelines and trials generally support a low initial daily dose of 25 to 50 mcg of levothyroxine (T4), followed with dose changes every 4 to 8 weeks and a goal of normalizing TSH to within the lower half of the reference range (0.4-2.5 mIU/L).14 This is generally similar to published treatment goals for primary hypothyroidism and is based on studies suggesting the lower half of the reference range is normal for young, healthy, euthyroid individuals.32 Though full replacement doses (1.6-1.8 mcg/kg of ideal body weight) can be started for those who are elderly or who have ischemic heart disease or angina, this approach should be avoided in favor of low-dose initial therapy.33 Thyroid supplements are best absorbed when taken apart from food, calcium, or iron supplements. The ATA suggests taking thyroid medication 60 minutes before breakfast or at bedtime (3 or more hours after the evening meal).33

Continue to: Screening guidelines differ

Screening guidelines differ

Lacking population-level screening data from RCTs, most organizations do not recommend screening for thyroid dysfunction or they note insufficient evidence to make a screening recommendation (TABLE 217,19,20,34). In their most recent recommendation statement on the subject in 2015, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) concluded the current evidence was insufficient to recommend for or against thyroid dysfunction screening in nonpregnant, asymptomatic adults.17 This differs from the ATA and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinology (AACE; formerly known as the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists), which both recommend targeted screening for thyroid dysfunction based on symptoms or risk factors.20

What about subclinical hypothyroidism in pregnancy?

Overt hypothyroidism is associated with adverse events during pregnancy and with subsequent neurodevelopmental complications in children, although the effects of SCH during pregnancy remain less certain. Concerns have been raised over the potential association of SCH with pregnancy loss, placental abruption, premature rupture of membranes, and neonatal death.35 Historically, the prevalence of SCH during pregnancy has ranged from 2% to 2.5%, but using lower trimester-based TSH reference ranges, the prevalence of SCH in pregnancy may be as high as 15%.35

Guided by a large RCT that failed to find benefit (pregnancy outcomes, neurodevelopmental outcomes in children) following treatment of SCH in pregnancy,36 the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends against routine screening for thyroid disease in pregnancy.34 The ATA notes insufficient evidence to rec-ommend universal screening for thyroid dysfunction in pregnancy but recommends targeted screening of those with risk factors.37 Data are conflicting on the benefit of treating known or recently detected SCH on pregnancy outcomes including pregnancy loss.35,38 As such, the American Society of Reproductive Medicine and the ATA both generally recommend treatment of SCH in pregnant patients, particularly when the TSH is ≥ 4.0 mIU/L and TPOAbs are present.37,39

a The ATA, ETA, and NICE have slightly different recommendations when a TSH level = 10 mIU/L. ETA and NICE recommend prioritizing treatment for individuals with this level, while ATA recommends treatment when individual factors are also considered.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors thank Family Medicine Medical Librarian Gwen Wilson, MLS, AHIP, for her assistance with literature searches.

CORRESPONDENCE

Nicholas LeFevre, MD, Family and Community Medicine, University of Missouri–Columbia School of Medicine, One Hospital Drive, M224 Medical Science Building, Columbia, MO 65212; nlefevre@health.missouri.edu

Subclinical hypothyroidism (SCH) is a biochemical state in which the thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) is elevated while the free thyroxine (T4) level is normal. Overt hypothyroidism is not diagnosed until the free T4 level is decreased, regardless of the degree of TSH elevation.

The overall prevalence of SCH in iodine-rich areas is 4% to 10%, with a risk for progression to overt hypothyroidism of between 2% and 6% annually.1 The prevalence of SCH varies depending on the TSH reference range used.1 The normal reference range for TSH varies depending on the laboratory and/or the reference population surveyed, with the range likely widening with increasing age.

SCH is most common among women, the elderly, and White individuals.2 The discovery of SCH is often incidental, given that usually it is detected by laboratory findings alone without associated symptoms of overt hypothyroidism.3

The not-so-significant role of symptoms in subclinical hypothyroidism

Symptoms associated with overt hypothyroidism include constipation, dry skin, fatigue, slow thinking, poor memory, muscle cramps, weakness, and cold intolerance. In SCH, these symptoms are inconsistent, with around 1 in 3 patients having no symptoms

One study reported that roughly 18% of euthyroid individuals, 22% of SCH patients, and 26% of those with overt hypothyroidism reported 4 or more symptoms classically thought to be related to hypothyroidism.4 A large Danish cohort study found that hypothyroid symptoms were no more common in patients with SCH than in euthyroid individuals in the general population.5 These studies question the validity of attributing symptoms to SCH.

Adverse health associations

Observational data suggest that SCH is associated with an increased risk for dyslipidemia, coronary heart disease, heart failure, and cardiovascular mortality, particularly in those with TSH levels ≥ 10 mIU/L.6,7 Such associations were not found for most adults with TSH levels between 5 and 10 mIU/L.8 There are also potential associations of SCH with obesity, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis.9,10 Despite thyroid studies being commonly ordered as part of a mental health evaluation, SCH has not been statistically associated with depressive symptoms.11,12

Caveats with laboratory testing

There are several issues to consider when performing a laboratory assessment of thyroid function. TSH levels fluctuate considerably during the day, as TSH secretion has a circadian rhythm. TSH values are 50% higher at night and in the early morning than during the rest of the day.13 TSH values also may rise in response to current illness or stress. Due to this biologic variability, repeat testing to confirm TSH levels is recommended if an initial test result is abnormal.14

Continue to: An exact reference range...

An exact reference range for TSH is not widely agreed upon—although most laboratories regard 4.0 to 5.0 mIU/L as the high-end cutoff for normal. Also, “normal” TSH levels appear to differ by age. Accordingly, some experts have recommended an age-based reference range for TSH levels,15 although this is not implemented widely by laboratories. A TSH level of 6.0 mIU/L (or even higher) may be more appropriate for adults older than 65 years.1

Biotin supplementation has been shown to cause spurious thyroid testing results (TSH, T3, T4) depending on the type of assay used. Therefore, supplements containing biotin should be withheld for several days before assessing thyroid function.16Patients with SCH are often categorized as having TSH levels between 4.5 and 10 mIU/L (around 90% of patients) or levels ≥ 10 mIU/L.8,17 If followed for 5 years, approximately 60% of patients with SCH and TSH levels between 4 and 10 mIU/L will normalize without intervention.18 Normalization is less common in patients with a TSH level greater than 10 mIU/L.18

The risk for progression to overt hypothyroidism also appears to be higher for those with certain risk factors. These include higher baseline TSH levels, presence of thyroid peroxidase antibodies (TPOAbs), or history of neck irradiation or radioactive iodine uptake.1 Other risk factors for eventual thyroid dysfunction include female sex, older age, goiter, and high iodine intake.13

Evidence for treatment varies

Guidelines for the treatment of SCH (TABLE 18,14,19,20) are founded on the condition’s risk for progression to overt hypothyroidism and its association with health consequences such as cardiovascular disease. Guidelines of the American Thyroid Association (ATA) and European Thyroid Association (ETA), and those of the United Kingdom–based National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), prioritize treatment for individuals with a TSH level > 10 mIU/La and for those with

There are few large RCTs of treatment outcomes for SCH. A 2017 RCT (the Thyroid Hormone Replacement for Untreated Older Adults with Subclinical Hypothyroidism, or TRUST, trial) of 737 adults older than 65 years with SCH evaluated the ability of levothyroxine to normalize TSH values compared with placebo. At 1 year, there was no difference in hypothyroid symptoms or tiredness scale scores with levothyroxine treatment compared with placebo.21 This finding was consistent even in the subgroup with a higher baseline symptom burden.22

Continue to: Two small RCTs evaluated...

Two small RCTs evaluated treatment of SCH with depressive symptoms and cognitive function, neither finding benefit compared with placebo.12,23 A 2018 systematic review and meta-analysis of 21 studies and 2192 adults did not show a benefit to quality of life or thyroid-specific symptoms in those treated for SCH compared with controls.24

RCT support also is lacking for a reduction in cardiovascular mortality following treatment for SCH. A large population-level retrospective cohort from Denmark showed no difference in cardiovascular mortality or myocardial infarction in those treated for SCH compared with controls.25 Pooled results from 2 RCTs (for patients older than 65 years, and those older than 80 years) showed no change in risk for cardiovascular outcomes in older adults treated for SCH.26 Older adults treated for SCH in the TRUST trial showed no improvements in systolic or diastolic function on echocardiography.27 Two trials showed no difference in carotid intima-media thickness with treatment of SCH compared with placebo.28,29

While most of the RCT data come from older adults, a retrospective cohort study in the United Kingdom of younger (ages 40-70 years; n = 3093) and older (age > 70 years; n = 1642) patients showed a reduction in cardiovascular mortality among treated patients who were younger (hazard ratio [HR] = 0.61; 4.2% vs. 6.6%) but not those who were older (HR = 0.99; 12.7% vs. 10.7%).30 There is also evidence that thyroid size in those with goiter can be reduced with treatment of SCH.31

A measured approach to treating subclinical hypothyroidism

Consider several factors when deciding whether to treat SCH. For instance, RCT data suggest a lack of treatment benefit in relieving depression, improving cognition, or reducing general hypothyroid symptoms. Treatment of SCH in older adults does not appear to improve cardiovascular outcomes. The question of whether long-term treatment of SCH in younger patients reduces cardiovascular morbidity or mortality lacks answers from RCTs. Before diagnosing SCH or starting treatment, always confirm SCH with repeat testing in 2 to 3 months, as a high percentage of those with untreated SCH will have normal thyroid function on repeat testing.

In the event you and your patient elect to treat SCH, guidelines and trials generally support a low initial daily dose of 25 to 50 mcg of levothyroxine (T4), followed with dose changes every 4 to 8 weeks and a goal of normalizing TSH to within the lower half of the reference range (0.4-2.5 mIU/L).14 This is generally similar to published treatment goals for primary hypothyroidism and is based on studies suggesting the lower half of the reference range is normal for young, healthy, euthyroid individuals.32 Though full replacement doses (1.6-1.8 mcg/kg of ideal body weight) can be started for those who are elderly or who have ischemic heart disease or angina, this approach should be avoided in favor of low-dose initial therapy.33 Thyroid supplements are best absorbed when taken apart from food, calcium, or iron supplements. The ATA suggests taking thyroid medication 60 minutes before breakfast or at bedtime (3 or more hours after the evening meal).33

Continue to: Screening guidelines differ

Screening guidelines differ

Lacking population-level screening data from RCTs, most organizations do not recommend screening for thyroid dysfunction or they note insufficient evidence to make a screening recommendation (TABLE 217,19,20,34). In their most recent recommendation statement on the subject in 2015, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) concluded the current evidence was insufficient to recommend for or against thyroid dysfunction screening in nonpregnant, asymptomatic adults.17 This differs from the ATA and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinology (AACE; formerly known as the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists), which both recommend targeted screening for thyroid dysfunction based on symptoms or risk factors.20

What about subclinical hypothyroidism in pregnancy?

Overt hypothyroidism is associated with adverse events during pregnancy and with subsequent neurodevelopmental complications in children, although the effects of SCH during pregnancy remain less certain. Concerns have been raised over the potential association of SCH with pregnancy loss, placental abruption, premature rupture of membranes, and neonatal death.35 Historically, the prevalence of SCH during pregnancy has ranged from 2% to 2.5%, but using lower trimester-based TSH reference ranges, the prevalence of SCH in pregnancy may be as high as 15%.35

Guided by a large RCT that failed to find benefit (pregnancy outcomes, neurodevelopmental outcomes in children) following treatment of SCH in pregnancy,36 the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends against routine screening for thyroid disease in pregnancy.34 The ATA notes insufficient evidence to rec-ommend universal screening for thyroid dysfunction in pregnancy but recommends targeted screening of those with risk factors.37 Data are conflicting on the benefit of treating known or recently detected SCH on pregnancy outcomes including pregnancy loss.35,38 As such, the American Society of Reproductive Medicine and the ATA both generally recommend treatment of SCH in pregnant patients, particularly when the TSH is ≥ 4.0 mIU/L and TPOAbs are present.37,39

a The ATA, ETA, and NICE have slightly different recommendations when a TSH level = 10 mIU/L. ETA and NICE recommend prioritizing treatment for individuals with this level, while ATA recommends treatment when individual factors are also considered.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors thank Family Medicine Medical Librarian Gwen Wilson, MLS, AHIP, for her assistance with literature searches.

CORRESPONDENCE

Nicholas LeFevre, MD, Family and Community Medicine, University of Missouri–Columbia School of Medicine, One Hospital Drive, M224 Medical Science Building, Columbia, MO 65212; nlefevre@health.missouri.edu

1. Reyes Domingo F, Avey MT, Doull M. Screening for thyroid dysfunction and treatment of screen-detected thyroid dysfunction in asymptomatic, community-dwelling adults: a systematic review. Syst Rev. 2019;8:260. doi: 10.1186/s13643-019-1181-7

2. Cooper DS, Biondi B. Subclinical thyroid disease. Lancet. 2012;379:1142-1154. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60276-6

3. Bauer BS, Azcoaga-Lorenzo A, Agrawal U, et al. Management strategies for patients with subclinical hypothyroidism: a protocol for an umbrella review. Syst Rev. 2021;10:290. doi: 10.1186/s13643-021-01842-y

4. Canaris GJ, Manowitz NR, Mayor G, et al. The Colorado thyroid disease prevalence study. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:526-534. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.4.526

5. Carlé A, Karmisholt JS, Knudsen N, et al. Does subclinical hypothyroidism add any symptoms? Evidence from a Danish population-based study. Am J Med. 2021;134:1115-1126.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2021.03.009

6. Gencer B, Collet TH, Virgini V, et al. Subclinical thyroid dysfunction and the risk of heart failure events: an individual participant data analysis from 6 prospective cohorts. Circulation. 2012;126:1040-1049. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.096024

7. Rodondi N, den Elzen WP, Bauer DC, et al. Subclinical hypothyroidism and the risk of coronary heart disease and mortality. JAMA. 2010;304:1365-1374. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1361

8. Bekkering GE, Agoritsas T, Lytvyn L, et al. Thyroid hormones treatment for subclinical hypothyroidism: a clinical practice guideline. BMJ. 2019;365:l2006. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l2006

9. Chung GE, Kim D, Kim W, et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease across the spectrum of hypothyroidism. J Hepatol. 2012;57:150-156. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.02.027

10. Kim D, Kim W, Joo SK, et al. Subclinical hypothyroidism and low-normal thyroid function are associated with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and fibrosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16:123-131.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.08.014

11. Kim JS, Zhang Y, Chang Y, et al. Subclinical hypothyroidism and incident depression in young and middle-age adults. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;103:1827-1833. doi: 10.1210/jc.2017-01247

12. Jorde R, Waterloo K, Storhaug H, et al. Neuropsychological function and symptoms in subjects with subclinical hypothyroidism and the effect of thyroxine treatment. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:145-53. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-1775

13. Azim S, Nasr C. Subclinical hypothyroidism: when to treat. Cleve Clin J Med. 2019;86:101-110. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.86a.17053

14. Pearce SH, Brabant G, Duntas LH, et al. 2013 ETA Guideline: Management of subclinical hypothyroidism. Eur Thyroid J. 2013;2:215-228. doi: 10.1159/000356507

15. Cappola AR. The thyrotropin reference range should be changed in older patients. JAMA. 2019;322:1961-1962. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.14728

16. Li D, Radulescu A, Shrestha RT, et al. Association of biotin ingestion with performance of hormone and nonhormone assays in healthy adults. JAMA. 2017;318:1150-1160.

17. LeFevre ML, USPSTF. Screening for thyroid dysfunction: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:641-650. doi: 10.7326/M15-0483

18. Meyerovitch J, Rotman-Pikielni P, Sherf M, et al. Serum thyrotropin measurements in the community: five-year follow-up in a large network of primary care physicians. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1533-1538. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.14.1533

19. NICE. Thyroid Disease: assessment and management (NICE guideline NG145). 2019. Accessed March 14, 2023. www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng145/resources/thyroid-disease-assessment-and-management-pdf-66141781496773

20. Garber JR, Cobin RH, Gharib H, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for hypothyroidism in adults: cosponsored by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and the American Thyroid Association. Thyroid. 2012;22:1200-1235. doi: 10.1089/thy.2012.0205

21. Stott DJ, Rodondi N, Kearney PM, et al. Thyroid hormone therapy for older adults with subclinical hypothyroidism. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:2534-2544. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1603825

22. de Montmollin M, Feller M, Beglinger S, et al. L-thyroxine therapy for older adults with subclinical hypothyroidism and hypothyroid symptoms: secondary analysis of a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172:709-716. doi: 10.7326/M19-3193

23. Parle J, Roberts L, Wilson S, et al. A randomized controlled trial of the effect of thyroxine replacement on cognitive function in community-living elderly subjects with subclinical hypothyroidism: the Birmingham Elderly Thyroid study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:3623-3632. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-2571

24. Feller M, Snel M, Moutzouri E, et al. Association of thyroid hormone therapy with quality of life and thyroid-related symptoms in patients with subclinical hypothyroidism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2018;320:1349-1359. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.13770

25. Andersen MN, Schjerning Olsen A-M, Madsen JC, et al. Levothyroxine substitution in patients with subclinical hypothyroidism and the risk of myocardial infarction and mortality. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0129793. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129793

26. Zijlstra LE, Jukema JW, Westendorp RG, et al. Levothyroxine treatment and cardiovascular outcomes in older people with subclinical hypothyroidism: pooled individual results of two randomised controlled trials. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021;12:674841. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2021.674841

27. Gencer B, Moutzouri E, Blum MR, et al. The impact of levothyroxine on cardiac function in older adults with mild subclinical hypothyroidism: a randomized clinical trial. Am J Med. 2020;133:848-856.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2020.01.018

28. Blum MR, Gencer B, Adam L, et al. Impact of thyroid hormone therapy on atherosclerosis in the elderly with subclinical hypothyroidism: a randomized trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;103:2988-2997. doi: 10.1210/jc.2018-00279

29. Aziz M, Kandimalla Y, Machavarapu A, et al. Effect of thyroxin treatment on carotid intima-media thickness (CIMT) reduction in patients with subclinical hypothyroidism (SCH): a meta-analysis of clinical trials. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2017;24:643-659. doi: 10.5551/jat.39917

30. Razvi S, Weaver JU, Butler TJ, et al. Levothyroxine treatment of subclinical hypothyroidism, fatal and nonfatal cardiovascular events, and mortality. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:811-817. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.1159

31. Romaldini JH, Biancalana MM, Figueiredo DI, et al. Effect of L-thyroxine administration on antithyroid antibody levels, lipid profile, and thyroid volume in patients with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Thyroid. 1996;6:183-188. doi: 10.1089/thy.1996.6.183

32. Biondi B, Cooper DS. The clinical significance of subclinical thyroid dysfunction. Endocr Rev. 2008;29:76-131. doi: 10.1210/er.2006-0043

33. Jonklaas J, Bianco AC, Bauer AJ, et al. Guidelines for the treatment of hypothyroidism: prepared by the american thyroid association task force on thyroid hormone replacement. Thyroid. 2014;24:1670-1751. doi: 10.1089/thy.2014.0028

34. ACOG. Thyroid disease in pregnancy: ACOG practice bulletin, Number 223. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:e261-e274. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003893

35. Maraka S, Ospina NM, O’Keeffe ET, et al. Subclinical hypothyroidism in pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thyroid. 2016;26:580-590. doi: 10.1089/thy.2015.0418

36. Casey BM, Thom EA, Peaceman AM, et al. Treatment of subclinical hypothyroidism or hypothyroxinemia in pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:815-825. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1606205

37. Alexander EK, Pearce EN, Brent FA, et al. 2017 Guidelines of the American Thyroid Association for the Diagnosis and Management of Thyroid Disease During Pregnancy and the Postpartum. Thyroid. 2017;27:315-389. doi: 10.1089/thy.2016.0457

38. Dong AC, Morgan J, Kane M, et al. Subclinical hypothyroidism and thyroid autoimmunity in recurrent pregnancy loss: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. 2020;113:587-600.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2019.11.003

39. Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Subclinical hypothyroidism in the infertile female population: a guideline. Fertil Steril. 2015;104:545-553. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.05.028

1. Reyes Domingo F, Avey MT, Doull M. Screening for thyroid dysfunction and treatment of screen-detected thyroid dysfunction in asymptomatic, community-dwelling adults: a systematic review. Syst Rev. 2019;8:260. doi: 10.1186/s13643-019-1181-7

2. Cooper DS, Biondi B. Subclinical thyroid disease. Lancet. 2012;379:1142-1154. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60276-6

3. Bauer BS, Azcoaga-Lorenzo A, Agrawal U, et al. Management strategies for patients with subclinical hypothyroidism: a protocol for an umbrella review. Syst Rev. 2021;10:290. doi: 10.1186/s13643-021-01842-y

4. Canaris GJ, Manowitz NR, Mayor G, et al. The Colorado thyroid disease prevalence study. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:526-534. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.4.526

5. Carlé A, Karmisholt JS, Knudsen N, et al. Does subclinical hypothyroidism add any symptoms? Evidence from a Danish population-based study. Am J Med. 2021;134:1115-1126.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2021.03.009

6. Gencer B, Collet TH, Virgini V, et al. Subclinical thyroid dysfunction and the risk of heart failure events: an individual participant data analysis from 6 prospective cohorts. Circulation. 2012;126:1040-1049. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.096024

7. Rodondi N, den Elzen WP, Bauer DC, et al. Subclinical hypothyroidism and the risk of coronary heart disease and mortality. JAMA. 2010;304:1365-1374. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1361

8. Bekkering GE, Agoritsas T, Lytvyn L, et al. Thyroid hormones treatment for subclinical hypothyroidism: a clinical practice guideline. BMJ. 2019;365:l2006. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l2006

9. Chung GE, Kim D, Kim W, et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease across the spectrum of hypothyroidism. J Hepatol. 2012;57:150-156. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.02.027

10. Kim D, Kim W, Joo SK, et al. Subclinical hypothyroidism and low-normal thyroid function are associated with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and fibrosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16:123-131.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.08.014

11. Kim JS, Zhang Y, Chang Y, et al. Subclinical hypothyroidism and incident depression in young and middle-age adults. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;103:1827-1833. doi: 10.1210/jc.2017-01247

12. Jorde R, Waterloo K, Storhaug H, et al. Neuropsychological function and symptoms in subjects with subclinical hypothyroidism and the effect of thyroxine treatment. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:145-53. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-1775

13. Azim S, Nasr C. Subclinical hypothyroidism: when to treat. Cleve Clin J Med. 2019;86:101-110. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.86a.17053

14. Pearce SH, Brabant G, Duntas LH, et al. 2013 ETA Guideline: Management of subclinical hypothyroidism. Eur Thyroid J. 2013;2:215-228. doi: 10.1159/000356507

15. Cappola AR. The thyrotropin reference range should be changed in older patients. JAMA. 2019;322:1961-1962. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.14728

16. Li D, Radulescu A, Shrestha RT, et al. Association of biotin ingestion with performance of hormone and nonhormone assays in healthy adults. JAMA. 2017;318:1150-1160.

17. LeFevre ML, USPSTF. Screening for thyroid dysfunction: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:641-650. doi: 10.7326/M15-0483

18. Meyerovitch J, Rotman-Pikielni P, Sherf M, et al. Serum thyrotropin measurements in the community: five-year follow-up in a large network of primary care physicians. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1533-1538. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.14.1533

19. NICE. Thyroid Disease: assessment and management (NICE guideline NG145). 2019. Accessed March 14, 2023. www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng145/resources/thyroid-disease-assessment-and-management-pdf-66141781496773

20. Garber JR, Cobin RH, Gharib H, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for hypothyroidism in adults: cosponsored by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and the American Thyroid Association. Thyroid. 2012;22:1200-1235. doi: 10.1089/thy.2012.0205

21. Stott DJ, Rodondi N, Kearney PM, et al. Thyroid hormone therapy for older adults with subclinical hypothyroidism. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:2534-2544. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1603825

22. de Montmollin M, Feller M, Beglinger S, et al. L-thyroxine therapy for older adults with subclinical hypothyroidism and hypothyroid symptoms: secondary analysis of a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172:709-716. doi: 10.7326/M19-3193

23. Parle J, Roberts L, Wilson S, et al. A randomized controlled trial of the effect of thyroxine replacement on cognitive function in community-living elderly subjects with subclinical hypothyroidism: the Birmingham Elderly Thyroid study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:3623-3632. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-2571

24. Feller M, Snel M, Moutzouri E, et al. Association of thyroid hormone therapy with quality of life and thyroid-related symptoms in patients with subclinical hypothyroidism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2018;320:1349-1359. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.13770

25. Andersen MN, Schjerning Olsen A-M, Madsen JC, et al. Levothyroxine substitution in patients with subclinical hypothyroidism and the risk of myocardial infarction and mortality. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0129793. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129793

26. Zijlstra LE, Jukema JW, Westendorp RG, et al. Levothyroxine treatment and cardiovascular outcomes in older people with subclinical hypothyroidism: pooled individual results of two randomised controlled trials. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021;12:674841. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2021.674841

27. Gencer B, Moutzouri E, Blum MR, et al. The impact of levothyroxine on cardiac function in older adults with mild subclinical hypothyroidism: a randomized clinical trial. Am J Med. 2020;133:848-856.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2020.01.018

28. Blum MR, Gencer B, Adam L, et al. Impact of thyroid hormone therapy on atherosclerosis in the elderly with subclinical hypothyroidism: a randomized trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;103:2988-2997. doi: 10.1210/jc.2018-00279

29. Aziz M, Kandimalla Y, Machavarapu A, et al. Effect of thyroxin treatment on carotid intima-media thickness (CIMT) reduction in patients with subclinical hypothyroidism (SCH): a meta-analysis of clinical trials. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2017;24:643-659. doi: 10.5551/jat.39917

30. Razvi S, Weaver JU, Butler TJ, et al. Levothyroxine treatment of subclinical hypothyroidism, fatal and nonfatal cardiovascular events, and mortality. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:811-817. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.1159

31. Romaldini JH, Biancalana MM, Figueiredo DI, et al. Effect of L-thyroxine administration on antithyroid antibody levels, lipid profile, and thyroid volume in patients with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Thyroid. 1996;6:183-188. doi: 10.1089/thy.1996.6.183

32. Biondi B, Cooper DS. The clinical significance of subclinical thyroid dysfunction. Endocr Rev. 2008;29:76-131. doi: 10.1210/er.2006-0043

33. Jonklaas J, Bianco AC, Bauer AJ, et al. Guidelines for the treatment of hypothyroidism: prepared by the american thyroid association task force on thyroid hormone replacement. Thyroid. 2014;24:1670-1751. doi: 10.1089/thy.2014.0028

34. ACOG. Thyroid disease in pregnancy: ACOG practice bulletin, Number 223. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:e261-e274. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003893

35. Maraka S, Ospina NM, O’Keeffe ET, et al. Subclinical hypothyroidism in pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thyroid. 2016;26:580-590. doi: 10.1089/thy.2015.0418

36. Casey BM, Thom EA, Peaceman AM, et al. Treatment of subclinical hypothyroidism or hypothyroxinemia in pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:815-825. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1606205

37. Alexander EK, Pearce EN, Brent FA, et al. 2017 Guidelines of the American Thyroid Association for the Diagnosis and Management of Thyroid Disease During Pregnancy and the Postpartum. Thyroid. 2017;27:315-389. doi: 10.1089/thy.2016.0457

38. Dong AC, Morgan J, Kane M, et al. Subclinical hypothyroidism and thyroid autoimmunity in recurrent pregnancy loss: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. 2020;113:587-600.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2019.11.003

39. Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Subclinical hypothyroidism in the infertile female population: a guideline. Fertil Steril. 2015;104:545-553. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.05.028

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

› Do not routinely screen for subclinical or overt hypothyroidism in asymptomatic nonpregnant adults. B

› Consider treatment of known or screening-detected subclinical hypothyroidism (SCH) in patients who are pregnant or trying to conceive. C

› Consider treating SCH in younger adults whose thyroidstimulating hormone level is ≥ 10 mIU/L. C

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series