User login

Whether subclinical hypothyroidism is clinically important and should be treated remains controversial. Studies have differed in their findings, and although most have found this condition to be associated with a variety of adverse outcomes, large randomized controlled trials are needed to clearly demonstrate its clinical impact in various age groups and the benefit of levothyroxine therapy.

Currently, the best practical approach is to base treatment decisions on the magnitude of elevation of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) and whether the patient has thyroid autoantibodies and associated comorbid conditions.

HIGH TSH, NORMAL FREE T4 LEVELS

Subclinical hypothyroidism is defined by elevated TSH along with a normal free thyroxine (T4).1

The hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis is a balanced homeostatic system, and TSH and thyroid hormone levels have an inverse log-linear relation: if free T4 and triiodothyronine (T3) levels go down even a little, TSH levels go up a lot.2

TSH secretion is pulsatile and has a circadian rhythm: serum TSH levels are 50% higher at night and early in the morning than during the rest of the day. Thus, repeated measurements in the same patient can vary by as much as half of the reference range.3

WHAT IS THE UPPER LIMIT OF NORMAL FOR TSH?

The upper limit of normal for TSH, defined as the 97.5th percentile, is approximately 4 or 5 mIU/L depending on the laboratory and the population, but some experts believe it should be lower.3

In favor of a lower upper limit: the distribution of serum TSH levels in the healthy general population does not seem to be a typical bell-shaped Gaussian curve, but rather has a tail at the high end. Some argue that some of the individuals with values in the upper end of the normal range may actually have undiagnosed hypothyroidism and that the upper 97.5th percentile cutoff would be 2.5 mIU/L if these people were excluded.4 Also, TSH levels higher than 2.5 mIU/L have been associated with a higher prevalence of antithyroid antibodies and a higher risk of clinical hypothyroidism.5

On the other hand, lowering the upper limit of normal to 2.5 mIU/L would result in 4 times as many people receiving a diagnosis of subclinical hypothyroidism, or 22 to 28 million people in the United States.4,6 Thus, lowering the cutoff may lead to unnecessary therapy and could even harm from overtreatment.

Another argument against lowering the upper limit of normal for TSH is that, with age, serum TSH levels shift higher.7 The third National Health and Nutrition Education Survey (NHANES III) found that the 97.5th percentile for serum TSH was 3.56 mIU/L for age group 20 to 29 but 7.49 mIU/L for octogenarians.7,8

It has been suggested that the upper limit of normal for TSH be adjusted for age, race, sex, and iodine intake.3 Currently available TSH reference ranges are not adjusted for these variables, and there is not enough evidence to suggest age-appropriate ranges,9 although higher TSH cutoffs for treatment are advised in elderly patients.10 Interestingly, higher TSH in older people has been linked to lower mortality rates in some studies.11

Authors of the NHANES III8 and Hanford Thyroid Disease study12 have proposed a cutoff of 4.1 mIU/L for the upper limit of normal for serum TSH in patients with negative antithyroid antibodies and normal findings on thyroid ultrasonography.

SUBCLINICAL HYPOTHYROIDISM IS COMMON

In different studies, the prevalence of subclinical hypothyroidism has been as low as 4% and as high as 20%.1,8,13 The prevalence is higher in women and increases with age.8 It is higher in iodine-sufficient areas, and it increases in iodine-deficient areas with iodine supplementation.14 Genetics also plays a role, as subclinical hypothyroidism is more common in white people than in African Americans.8

A difficulty in estimating the prevalence is the disagreement about the cutoff for TSH, which may differ from that in the general population in certain subgroups such as adolescents, the elderly, and pregnant women.10,15

A VARIETY OF CAUSES

The most common cause of subclinical hypothyroidism, accounting for 60% to 80% of cases, is Hashimoto (autoimmune) thyroiditis,2 in which thyroid peroxidase antibodies are usually present.2,16

Also important to rule out are false-positive elevations due to substances that interfere with TSH assays (eg, heterophile antibodies, rheumatoid factor, biotin, macro-TSH); reversible causes such as the recovery phase of euthyroid sick syndrome; subacute, painless, or postpartum thyroiditis; central hypo- or hyperthyroidism; and thyroid hormone resistance.

SUBCLINICAL HYPOTHYROIDISM CAN RESOLVE OR PROGRESS

“Subclinical” suggests that the disease is in its early stage, with changes in TSH already apparent but decreases in thyroid hormone levels yet to come.17 And indeed, subclinical hypothyroidism can progress to overt hypothyroidism,18 although it has been reported to resolve spontaneously in half of cases within 2 years,19 typically in patients with TSH values of 4 to 6 mIU/L.20 The rate of progression to overt hypothyroidism is estimated to be 33% to 55% over 10 to 20 years of follow-up.18

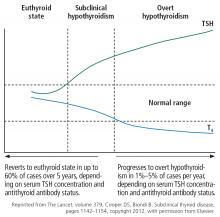

Figure 1 shows the natural history of subclinical hypothyroidism.1

GUIDELINES FOR SCREENING DIFFER

Guidelines differ on screening for thyroid disease in the general population, owing to lack of large-scale randomized controlled trials showing treatment benefit in otherwise-healthy people with mildly elevated TSH values.

Various professional societies have adopted different criteria for aggressive case-finding in patients at risk of thyroid disease. Risk factors include family history of thyroid disease, neck irradiation, partial thyroidectomy, dyslipidemia, atrial fibrillation, unexplained weight loss, hyperprolactinemia, autoimmune disorders, and use of medications affecting thyroid function.23

The US Preventive Services Task Force in 2014 found insufficient evidence on the benefits and harms of screening.24

The American Thyroid Association (ATA) recommends screening adults starting at age 35, with repeat testing every 5 years in patients who have no signs or symptoms of hypothyroidism, and more frequently in those who do.25

The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists recommends screening in women and older patients. Their guidelines and those of the ATA also suggest screening people at high risk of thyroid disease due to risk factors such as history of autoimmune diseases, neck irradiation, or medications affecting thyroid function.26

The American Academy of Family Physicians recommends screening after age 60.18

The American College of Physicians recommends screening patients over age 50 who have symptoms.18

Our approach. Although evidence is lacking to recommend routine screening in adults, aggressive case-finding and treatment in patients at risk of thyroid disease can, we believe, offset the risks associated with subclinical hypothyroidism.24

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

About 70% of patients with subclinical hypothyroidism have no symptoms.13

Tiredness was more common in subclinical hypothyroid patients with TSH levels lower than 10 mIU/L compared with euthyroid controls in 1 study, but other studies have been unable to replicate this finding.27,28

Other frequently reported symptoms include dry skin, cognitive slowing, poor memory, muscle weakness, cold intolerance, constipation, puffy eyes, and hoarseness.13

The evidence in favor of levothyroxine therapy to improve symptoms in subclinical hypothyroidism has varied, with some studies showing an improvement in symptom scores compared with placebo, while others have not shown any benefit.29–31

In one study, the average TSH value for patients whose symptoms did not improve with therapy was 4.6 mIU/L.31 An explanation for the lack of effect in this group may be that the TSH values for these patients were in the high-normal range. Also, because most subclinical hypothyroid patients have no symptoms, it is difficult to ascertain symptomatic improvement. Though it is possible to conclude that levothyroxine therapy has a limited role in this group, it is important to also consider the suggestive evidence that untreated subclinical hypothyroidism may lead to increased morbidity and mortality.

ADVERSE EFFECTS OF SUBCLINICAL HYPOTHYROIDISM, EFFECTS OF THERAPY

INDIVIDUALIZED MANAGEMENT AND SHARED DECISION-MAKING

The management of subclinical hypothyroidism should be individualized on the basis of extent of thyroid dysfunction, comorbid conditions, risk factors, and patient preference.118 Shared decision-making is key, weighing the risks and benefits of levothyroxine treatment and the patient’s goals.

The risks of treatment should be kept in mind and explained to the patient. Levothyroxine has a narrow therapeutic range, causing a possibility of overreplacement, and a half-life of 7 days that can cause dosing errors to have longer effect.118,119

Adherence can be a challenge. The drug needs to be taken on an empty stomach because foods and supplements interfere with its absorption.118,120 In addition, the cost of medication, frequent biochemical monitoring, and possible need for titration can add to financial burden.

When choosing the dose, one should consider the degree of hypothyroidism or TSH elevation and the patient’s weight, and adjust the dose gently.

If the TSH is high-normal

It is proposed that a TSH range of 3 to 5 mIU/L overlaps with normal thyroid function in a great segment of the population, and at this level it is probably not associated with clinically significant consequences. For these reasons, levothyroxine therapy is not thought to be beneficial for those with TSH in this range.

Pollock et al121 found that, in patients with symptoms suggesting hypothyroidism and TSH values in the upper end of the normal range, there was no improvement in cognitive function or psychological well-being after 12 weeks of levothyroxine therapy.

However, due to the concern for possible adverse maternal and fetal outcomes and low IQ in children of pregnant patients with subclinical hypothyroidism, levothyroxine therapy is advised in those who are pregnant or planning pregnancy who have TSH levels higher than 2.5 mIU/L, especially if they have thyroid peroxidase antibody. Levothyroxine therapy is not recommended for pregnant patients with negative thyroid peroxidase antibody and TSH within the pregnancy-specific range or less than 4 mIU/L if the reference ranges are unavailable.

Keep in mind that, even at these TSH values, there is risk of progression to overt hypothyroidism, especially in the presence of thyroid peroxidase antibody, so patients in this group should be monitored closely.

If TSH is mildly elevated

The evidence to support levothyroxine therapy in patients with subclinical hypothyroidism with TSH levels less than 10 mIU/L remains inconclusive, and the decision to treat should be based on clinical judgment.2 The studies that have looked at the benefit of treating subclinical hypothyroidism in terms of cardiac, neuromuscular, cognitive, and neuropsychiatric outcomes have included patients with a wide range of TSH levels, and some of these studies were not stratified on the basis of degree of TSH elevation.

The risk that subclinical hypothyroidism will progress to overt hypothyroidism in patients with TSH higher than 8 mIU/L is high, and in 70% of these patients, the TSH level rises to more than 10 mIU/L within 4 years. Early treatment should be considered if the TSH is higher than 7 or 8 mIU/L.

If TSH is higher than 10 mIU/L

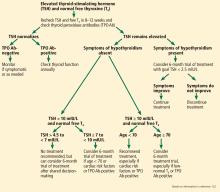

Figure 2 outlines an algorithmic approach to subclinical hypothyroidism in nonpregnant patients as suggested by Peeters.122

- Cooper DS, Biondi B. Subclinical thyroid disease. Lancet 2012; 379(9821):1142–1154. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60276-6

- Fatourechi V. Subclinical hypothyroidism: an update for primary care physicians. Mayo Clin Proc 2009; 84(1):65–71. doi:10.4065/84.1.65

- Laurberg P, Andersen S, Carle A, Karmisholt J, Knudsen N, Pedersen IB. The TSH upper reference limit: where are we at? Nat Rev Endocrinol 2011; 7(4):232–239. doi:10.1038/nrendo.2011.13

- Wartofsky L, Dickey RA. The evidence for a narrower thyrotropin reference range is compelling. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2005; 90(9):5483–5488. doi:10.1210/jc.2005-0455

- Spencer CA, Hollowell JG, Kazarosyan M, Braverman LE. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH)-thyroperoxidase antibody relationships demonstrate that TSH upper reference limits may be skewed by occult thyroid dysfunction. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007; 92(11):4236–4240. doi:10.1210/jc.2007-0287

- Fatourechi V, Klee GG, Grebe SK, et al. Effects of reducing the upper limit of normal TSH values. JAMA 2003; 290(24):3195–3196. doi:10.1001/jama.290.24.3195-a

- Surks MI, Hollowell JG. Age-specific distribution of serum thyrotropin and antithyroid antibodies in the US population: implications for the prevalence of subclinical hypothyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007; 92(12):4575–4582. doi:10.1210/jc.2007-1499

- Hollowell JG, Staehling NW, Flanders WD, et al. Serum TSH, T(4), and thyroid antibodies in the United States population (1988 to 1994): National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III). J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2002; 87(2):489–499. doi:10.1210/jcem.87.2.8182

- Jonklaas J, Bianco AC, Bauer AJ, et al; American Thyroid Association Task Force on Thyroid Hormone Replacement. Guidelines for the treatment of hypothyroidism: prepared by the American Thyroid Association Task Force on Thyroid Hormone Replacement. Thyroid 2014; 24(12):1670–1751. doi:10.1089/thy.2014.0028

- Hennessey JV, Espaillat R. Diagnosis and management of subclinical hypothyroidism in elderly adults: a review of the literature. J Am Geriatr Soc 2015; 63(8):1663–1673. doi:10.1111/jgs.13532

- Razvi S, Shakoor A, Vanderpump M, Weaver JU, Pearce SH. The influence of age on the relationship between subclinical hypothyroidism and ischemic heart disease: a metaanalysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008; 93(8):2998–3007. doi:10.1210/jc.2008-0167

- Hamilton TE, Davis S, Onstad L, Kopecky KJ. Thyrotropin levels in a population with no clinical, autoantibody, or ultrasonographic evidence of thyroid disease: implications for the diagnosis of subclinical hypothyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008; 93(4):1224–1230. doi:10.1210/jc.2006-2300

- Canaris GJ, Manowitz NR, Mayor G, Ridgway EC. The Colorado thyroid disease prevalence study. Arch Intern Med 2000; 160(4):526–534. pmid:10695693

- Teng W, Shan Z, Teng X, et al. Effect of iodine intake on thyroid diseases in China. N Engl J Med 2006; 354(26):2783–2793. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa054022

- Negro R, Stagnaro-Green A. Diagnosis and management of subclinical hypothyroidism in pregnancy. BMJ 2014; 349:g4929. doi:10.1136/bmj.g4929

- Baumgartner C, Blum MR, Rodondi N. Subclinical hypothyroidism: summary of evidence in 2014. Swiss Med Wkly 2014; 144:w14058. doi:10.4414/smw.2014.14058

- Stedman TL. Stedman’s Medical Dictionary. 28th ed. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2006.

- Raza SA, Mahmood N. Subclinical hypothyroidism: controversies to consensus. Indian J Endocrinol Metab 2013; 17(suppl 3):S636–S642. doi:10.4103/2230-8210.123555

- Huber G, Staub JJ, Meier C, et al. Prospective study of the spontaneous course of subclinical hypothyroidism: prognostic value of thyrotropin, thyroid reserve, and thyroid antibodies. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2002; 87(7):3221–3226. doi:10.1210/jcem.87.7.8678

- Diez JJ, Iglesias P, Burman KD. Spontaneous normalization of thyrotropin concentrations in patients with subclinical hypothyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2005; 90(7):4124–4127. doi:10.1210/jc.2005-0375

- Vanderpump MP, Tunbridge WM, French JM, et al. The incidence of thyroid disorders in the community: a twenty-year follow-up of the Whickham survey. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1995; 43(1):55–68. pmid:7641412

- Li Y, Teng D, Shan Z, et al. Antithyroperoxidase and antithyroglobulin antibodies in a five-year follow-up survey of populations with different iodine intakes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008; 93(5):1751–1757. doi:10.1210/jc.2007-2368

- Hennessey JV, Klein I, Woeber KA, Cobin R, Garber JR. Aggressive case finding: a clinical strategy for the documentation of thyroid dysfunction. Ann Intern Med 2015; 163(4):311–312. doi:10.7326/M15-0762

- Rugge JB, Bougatsos C, Chou R. Screening and treatment of thyroid dysfunction: an evidence review for the US.Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med 2015; 162(1):35–45. doi:10.7326/M14-1456

- Ladenson PW, Singer PA, Ain KB, et al. American Thyroid Association guidelines for detection of thyroid dysfunction. Arch Intern Med 2000; 160(11):1573–1575. pmid:10847249

- Garber JR, Cobin RH, Gharib H, et al; American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American Thyroid Association Taskforce on Hypothyroidism in Adults. Clinical practice guidelines for hypothyroidism in adults: cosponsored by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and the American Thyroid Association. Endocr Pract 2012; 18(6):988–1028. doi:10.4158/EP12280.GL

- Jorde R, Waterloo K, Storhaug H, Nyrnes A, Sundsfjord J, Jenssen TG. Neuropsychological function and symptoms in subjects with subclinical hypothyroidism and the effect of thyroxine treatment. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006; 91(1):145–153. doi:10.1210/jc.2005-1775

- Joffe RT, Pearce EN, Hennessey JV, Ryan JJ, Stern RA. Subclinical hypothyroidism, mood, and cognition in older adults: a review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2013; 28(2):111–118. doi:10.1002/gps.3796

- Cooper DS, Halpern R, Wood LC, Levin AA, Ridgway EC. L-thyroxine therapy in subclinical hypothyroidism. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 1984; 101(1):18–24. pmid:6428290

- Nystrom E, Caidahl K, Fager G, Wikkelso C, Lundberg PA, Lindstedt G. A double-blind cross-over 12-month study of L-thyroxine treatment of women with ‘subclinical’ hypothyroidism. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1988; 29(1):63–75. pmid:3073880

- Monzani F, Del Guerra P, Caraccio N, et al. Subclinical hypothyroidism: neurobehavioral features and beneficial effect of L-thyroxine treatment. Clin Investig 1993; 71(5):367–371. pmid:8508006

- Biondi B. Thyroid and obesity: an intriguing relationship. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2010; 95(8):3614–3617. doi:10.1210/jc.2010-1245

- Erdogan M, Canataroglu A, Ganidagli S, Kulaksizoglu M. Metabolic syndrome prevalence in subclinic and overt hypothyroid patients and the relation among metabolic syndrome parameters. J Endocrinol Invest 2011; 34(7):488–492. doi:10.3275/7202

- Javed Z, Sathyapalan T. Levothyroxine treatment of mild subclinical hypothyroidism: a review of potential risks and benefits. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab 2016; 7(1):12–23. doi:10.1177/2042018815616543

- Pearce SH, Brabant G, Duntas LH, et al. 2013 ETA guideline: management of subclinical hypothyroidism. Eur Thyroid J 2013; 2(4):215–228. doi:10.1159/000356507

- Wang C. The relationship between type 2 diabetes mellitus and related thyroid diseases. J Diabetes Res 2013; 2013:390534. doi:10.1155/2013/390534

- Razvi S, Weaver JU, Vanderpump MP, Pearce SH. The incidence of ischemic heart disease and mortality in people with subclinical hypothyroidism: reanalysis of the Whickham survey cohort. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2010; 95(4):1734–1740. doi:10.1210/jc.2009-1749

- Bindels AJ, Westendorp RG, Frolich M, Seidell JC, Blokstra A, Smelt AH. The prevalence of subclinical hypothyroidism at different total plasma cholesterol levels in middle aged men and women: a need for case-finding? Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1999; 50(2):217–220. pmid:10396365

- Pearce EN. Hypothyroidism and dyslipidemia: modern concepts and approaches. Curr Cardiol Rep 2004; 6(6):451–456. pmid:15485607

- Pearce EN. Update in lipid alterations in subclinical hypothyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012; 97(2):326–333. doi:10.1210/jc.2011-2532

- Rizos CV, Elisaf MS, Liberopoulos EN. Effects of thyroid dysfunction on lipid profile. Open Cardiovasc Med J 2011; 5:76–84. doi:10.2174/1874192401105010076

- Peppa M, Betsi G, Dimitriadis G. Lipid abnormalities and cardiometabolic risk in patients with overt and subclinical thyroid disease. J Lipids 2011; 2011:575840. doi:10.1155/2011/575840

- Asvold BO, Vatten LJ, Nilsen TI, Bjoro T. The association between TSH within the reference range and serum lipid concentrations in a population-based study. the HUNT study. Eur J Endocrinol 2007;1 56(2):181–186. doi:10.1530/eje.1.02333

- Danese MD, Ladenson PW, Meinert CL, Powe NR. Clinical review 115: effect of thyroxine therapy on serum lipoproteins in patients with mild thyroid failure: a quantitative review of the literature. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2000; 85(9):2993–3001. doi:10.1210/jcem.85.9.6841

- Razvi S, Ingoe L, Keeka G, Oates C, McMillan C, Weaver JU. The beneficial effect of L-thyroxine on cardiovascular risk factors, endothelial function, and quality of life in subclinical hypothyroidism: randomized, crossover trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007; 92(5):1715–1723. doi:10.1210/jc.2006-1869

- Abreu IM, Lau E, de Sousa Pinto B, Carvalho D. Subclinical hypothyroidism: to treat or not to treat, that is the question! A systematic review with meta-analysis on lipid profile. Endocr Connect 2017; 6(3):188–199. doi:10.1530/EC-17-0028

- Robison CD, Bair TL, Horne BD, et al. Hypothyroidism as a risk factor for statin intolerance. J Clin Lipidol 2014; 8(4):401–407. doi:10.1016/j.jacl.2014.05.005

- Hak AE, Pols HA, Visser TJ, Drexhage HA, Hofman A, Witteman JC. Subclinical hypothyroidism is an independent risk factor for atherosclerosis and myocardial infarction in elderly women: the Rotterdam study. Ann Intern Med 2000; 132(4):270–278. pmid:10681281

- Boekholdt SM, Titan SM, Wiersinga WM, et al. Initial thyroid status and cardiovascular risk factors: the EPIC-Norfolk prospective population study. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2010; 72(3):404–410. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2265.2009.03640.x

- Andersen MN, Olsen AM, Madsen JC, et al. Levothyroxine substitution in patients with subclinical hypothyroidism and the risk of myocardial infarction and mortality. PLoS One 2015; 10(6):e0129793. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0129793

- Biondi B. Cardiovascular effects of mild hypothyroidism. Thyroid 2007; 17(7):625–630. doi:10.1089/thy.2007.0158

- Brenta G, Mutti LA, Schnitman M, Fretes O, Perrone A, Matute ML. Assessment of left ventricular diastolic function by radionuclide ventriculography at rest and exercise in subclinical hypothyroidism, and its response to L-thyroxine therapy. Am J Cardiol 2003; 91(11):1327–1330. pmid:12767425

- Taddei S, Caraccio N, Virdis A, et al. Impaired endothelium-dependent vasodilatation in subclinical hypothyroidism: beneficial effect of levothyroxine therapy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003; 88(8):3731–3737. doi:10.1210/jc.2003-030039

- Gao N, Zhang W, Zhang YZ, Yang Q, Chen SH. Carotid intima-media thickness in patients with subclinical hypothyroidism: a meta-analysis. Atherosclerosis 2013; 227(1):18–25. doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2012.10.070

- Biondi B, Cooper DS. The clinical significance of subclinical thyroid dysfunction. Endocr Rev 2008; 29(1):76–131. doi:10.1210/er.2006-0043

- Chaker L, Baumgartner C, den Elzen WP, et al; Thyroid Studies Collaboration. Subclinical hypothyroidism and the risk of stroke events and fatal stroke: an individual participant data analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2015; 100(6):2181–2191. doi:10.1210/jc.2015-1438

- Monzani F, Di Bello V, Caraccio N, et al. Effect of levothyroxine on cardiac function and structure in subclinical hypothyroidism: a double blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2001; 86(3):1110–1115. doi:10.1210/jcem.86.3.7291

- Parle JV, Maisonneuve P, Sheppard MC, Boyle P, Franklyn JA. Prediction of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in elderly people from one low serum thyrotropin result: a 10-year cohort study. Lancet 2001; 358(9285):861-865. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06067-6

- Razvi S, Weaver JU, Butler TJ, Pearce SH. Levothyroxine treatment of subclinical hypothyroidism, fatal and nonfatal cardiovascular events, and mortality. Arch Intern Med 2012; 172(10):811–817. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2012.1159

- Pasqualetti G, Tognini S, Polini A, Caraccio N, Monzani F. Is subclinical hypothyroidism a cardiovascular risk factor in the elderly? J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2013; 98(6):2256–2266. doi:10.1210/jc.2012-3818

- Mooijaart SP, IEMO 80-plus Thyroid Trial Collaboration. Subclinical thyroid disorders. Lancet 2012; 380(9839):335. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61241-0

- Rodondi N, Bauer DC. Subclinical hypothyroidism and cardiovascular risk: how to end the controversy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2013; 98(6):2267–2269. doi:10.1210/jc.2013-1875

- Rodondi N, Newman AB, Vittinghoff E, et al. Subclinical hypothyroidism and the risk of heart failure, other cardiovascular events, and death. Arch Intern Med 2005; 165(21):2460–2466. doi:10.1001/archinte.165.21.2460

- Rodondi N, Bauer DC, Cappola AR, et al. Subclinical thyroid dysfunction, cardiac function, and the risk of heart failure. The Cardiovascular Health study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008; 52(14):1152–1159. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2008.07.009

- Haggerty JJ Jr, Garbutt JC, Evans DL, et al. Subclinical hypothyroidism: a review of neuropsychiatric aspects. Int J Psychiatry Med 1990; 20(2):193–208. doi:10.2190/ADLY-1UU0-1A8L-HPXY

- Baldini IM, Vita A, Mauri MC, et al. Psychopathological and cognitive features in subclinical hypothyroidism. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 1997; 21(6):925–935. pmid:9380789

- del Ser Quijano T, Delgado C, Martinez Espinosa S, Vazquez C. Cognitive deficiency in mild hypothyroidism. Neurologia 2000; 15(5):193–198. Spanish. pmid:10850118

- Correia N, Mullally S, Cooke G, et al. Evidence for a specific defect in hippocampal memory in overt and subclinical hypothyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2009; 94(10):3789–3797. doi:10.1210/jc.2008-2702

- Aghili R, Khamseh ME, Malek M, et al. Changes of subtests of Wechsler memory scale and cognitive function in subjects with subclinical hypothyroidism following treatment with levothyroxine. Arch Med Sci 2012; 8(6):1096–1101. doi:10.5114/aoms.2012.32423

- Pasqualetti G, Pagano G, Rengo G, Ferrara N, Monzani F. Subclinical hypothyroidism and cognitive impairment: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2015; 100(11):4240–4248. doi:10.1210/jc.2015-2046

- Christ-Crain M, Meier C, Huber PR, Staub J, Muller B. Effect of L-thyroxine replacement therapy on surrogate markers of skeletal and cardiac function in subclinical hypothyroidism. Endocrinologist 2004; 14(3):161–166. doi:10.1097/01.ten.0000127932.31710.4f

- Brennan MD, Powell C, Kaufman KR, Sun PC, Bahn RS, Nair KS. The impact of overt and subclinical hyperthyroidism on skeletal muscle. Thyroid 2006; 16(4):375–380. doi:10.1089/thy.2006.16.375

- Reuters VS, Teixeira Pde F, Vigario PS, et al. Functional capacity and muscular abnormalities in subclinical hypothyroidism. Am J Med Sci 2009; 338(4):259–263. doi:10.1097/MAJ.0b013e3181af7c7c

- Mainenti MR, Vigario PS, Teixeira PF, Maia MD, Oliveira FP, Vaisman M. Effect of levothyroxine replacement on exercise performance in subclinical hypothyroidism. J Endocrinol Invest 2009; 32(5):470–473. doi:10.3275/6106

- Lankhaar JA, de Vries WR, Jansen JA, Zelissen PM, Backx FJ. Impact of overt and subclinical hypothyroidism on exercise tolerance: a systematic review. Res Q Exerc Sport 2014; 85(3):365–389. doi:10.1080/02701367.2014.930405

- Lee JS, Buzkova P, Fink HA, et al. Subclinical thyroid dysfunction and incident hip fracture in older adults. Arch Intern Med 2010; 170(21):1876–1883. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2010.424

- Svare A, Nilsen TI, Asvold BO, et al. Does thyroid function influence fracture risk? Prospective data from the HUNT2 study, Norway. Eur J Endocrinol 2013; 169(6):845–852. doi:10.1530/EJE-13-0546

- Di Mase R, Cerbone M, Improda N, et al. Bone health in children with long-term idiopathic subclinical hypothyroidism. Ital J Pediatr 2012; 38:56. doi:10.1186/1824-7288-38-56

- Boelaert K. The association between serum TSH concentration and thyroid cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer 2009; 16(4):1065–1072. doi:10.1677/ERC-09-0150

- Haymart MR, Glinberg SL, Liu J, Sippel RS, Jaume JC, Chen H. Higher serum TSH in thyroid cancer patients occurs independent of age and correlates with extrathyroidal extension. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2009; 71(3):434–439. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2265.2008.03489.x

- Fiore E, Vitti P. Serum TSH and risk of papillary thyroid cancer in nodular thyroid disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012; 97(4):1134–1145. doi:10.1210/jc.2011-2735

- Fiore E, Rago T, Provenzale MA, et al. L-thyroxine-treated patients with nodular goiter have lower serum TSH and lower frequency of papillary thyroid cancer: results of a cross-sectional study on 27,914 patients. Endocr Relat Cancer 2010; 17(1):231–239. doi:10.1677/ERC-09-0251

- Hercbergs AH, Ashur-Fabian O, Garfield D. Thyroid hormones and cancer: clinical studies of hypothyroidism in oncology. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes 2010; 17(5):432–436. doi:10.1097/MED.0b013e32833d9710

- Thvilum M, Brandt F, Brix TH, Hegedus L. A review of the evidence for and against increased mortality in hypothyroidism. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2012; 8(7):417–424. doi:10.1038/nrendo.2012.29

- Stott DJ, Rodondi N, Kearney PM, et al; TRUST Study Group. Thyroid hormone therapy for older adults with subclinical hypothyroidism. N Engl J Med 2017; 376(26):2534–2544. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1603825

- Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Subclinical hypothyroidism in the infertile female population: a guideline. Fertil Steril 2015; 104(3):545–753. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.05.028

- Stagnaro-Green A, Abalovich M, Alexander E, et al; American Thyroid Association Taskforce on Thyroid Disease During Pregnancy and Postpartum. Guidelines of the American Thyroid Association for the diagnosis and management of thyroid disease during pregnancy and postpartum. Thyroid 2011; 21(10):1081–1125. doi:10.1089/thy.2011.0087

- Goldsmith RE, Sturgis SH, Lerman J, Stanbury JB. The menstrual pattern in thyroid disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1952; 12(7):846-855. doi:10.1210/jcem-12-7-846

- Plowden TC, Schisterman EF, Sjaarda LA, et al. Subclinical hypothyroidism and thyroid autoimmunity are not associated with fecundity, pregnancy loss, or live birth. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2016; 101(6):2358–2365. doi:10.1210/jc.2016-1049

- Alexander EK, Pearce EN, Brent GA, et al. 2017 Guidelines of the American Thyroid Association for the diagnosis and management of thyroid disease during pregnancy and the postpartum. Thyroid 2017; 27(3):315–389. doi:10.1089/thy.2016.0457

- Negro R, Formoso G, Mangieri T, Pezzarossa A, Dazzi D, Hassan H. Levothyroxine treatment in euthyroid pregnant women with autoimmune thyroid disease: effects on obstetrical complications. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006; 91(7):2587–2591. doi:10.1210/jc.2005-1603

- Panesar NS, Li CY, Rogers MS. Reference intervals for thyroid hormones in pregnant Chinese women. Ann Clin Biochem 2001; 38(pt 4):329–332. doi:10.1258/0004563011900830

- Lepoutre T, Debieve F, Gruson D, Daumerie C. Reduction of miscarriages through universal screening and treatment of thyroid autoimmune diseases. Gynecol Obstet Invest 2012; 74(4):265–273. doi:10.1159/000343759

- De Groot L, Abalovich M, Alexander EK, et al. Management of thyroid dysfunction during pregnancy and postpartum: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012; 97(8):2543–2565. doi:10.1210/jc.2011-2803

- Crawford NM, Steiner AZ. Thyroid autoimmunity and reproductive function. Semin Reprod Med 2016; 34(6):343–350. doi:10.1055/s-0036-1593485

- Maraka S, Ospina NM, O’Keeffe DT, et al. Subclinical hypothyroidism in pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thyroid 2016; 26(4):580–590. doi:10.1089/thy.2015.0418

- Wiles KS, Jarvis S, Nelson-Piercy C. Are we overtreating subclinical hypothyroidism in pregnancy? BMJ 2015; 351:h4726. doi:10.1136/bmj.h4726

- Tudela CM, Casey BM, McIntire DD, Cunningham FG. Relationship of subclinical thyroid disease to the incidence of gestational diabetes. Obstet Gynecol 2012; 119(5):983–988. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e318250aeeb

- Lazarus J, Brown RS, Daumerie C, Hubalewska-Dydejczyk A, Negro R, Vaidya B. 2014 European Thyroid Association guidelines for the management of subclinical hypothyroidism in pregnancy and in children. Eur Thyroid J 2014; 3(2):76–94. doi:10.1159/000362597

- Karakosta P, Alegakis D, Georgiou V, et al. Thyroid dysfunction and autoantibodies in early pregnancy are associated with increased risk of gestational diabetes and adverse birth outcomes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012; 97(12):4464–4472. doi:10.1210/jc.2012-2540

- Toulis KA, Stagnaro-Green A, Negro R. Maternal subclinical hypothyroidsm and gestational diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis. Endocr Pract 2014; 20(7):703–714. doi:10.4158/EP13440.RA

- van den Boogaard E, Vissenberg R, Land JA, et al. Significance of subclinical thyroid dysfunction and thyroid autoimmunity before conception and in early pregnancy: a systematic review. Hum Reprod Update 2011; 17(5):605–619. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmr024

- Wilson KL, Casey BM, McIntire DD, Halvorson LM, Cunningham FG. Subclinical thyroid disease and the incidence of hypertension in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2012; 119(2 Pt 1):315–320. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e318240de6a

- Ashoor G, Maiz N, Rotas M, Jawdat F, Nicolaides KH. Maternal thyroid function at 11 to 13 weeks of gestation and subsequent fetal death. Thyroid 2010; 20(9):989–993. doi:10.1089/thy.2010.0058

- Casey BM, Dashe JS, Wells CE, et al. Subclinical hypothyroidism and pregnancy outcomes. Obstet Gynecol 2005; 105(2):239–245. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000152345.99421.22

- Negro R, Schwartz A, Gismondi R, Tinelli A, Mangieri T, Stagnaro-Green A. Increased pregnancy loss rate in thyroid antibody negative women with TSH levels between 2.5 and 5.0 in the first trimester of pregnancy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2010; 95(9):E44–E48. doi:10.1210/jc.2010-0340

- Su PY, Huang K, Hao JH, et al. Maternal thyroid function in the first twenty weeks of pregnancy and subsequent fetal and infant development: a prospective population-based cohort study in China. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011; 96(10):3234–3241. doi:10.1210/jc.2011-0274

- Allan WC, Haddow JE, Palomaki GE, et al. Maternal thyroid deficiency and pregnancy complications: implications for population screening. J Med Screen 2000; 7(3):127–130. doi:10.1136/jms.7.3.127

- Benhadi N, Wiersinga WM, Reitsma JB, Vrijkotte TG, Bonsel GJ. Higher maternal TSH levels in pregnancy are associated with increased risk for miscarriage, fetal or neonatal death. Eur J Endocrinol 2009; 160(6):985–991. doi:10.1530/EJE-08-0953

- Korevaar TI, Medici M, de Rijke YB, et al. Ethnic differences in maternal thyroid parameters during pregnancy: the generation R study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2013; 98(9):3678–3686. doi:10.1210/jc.2013-2005

- Cleary-Goldman J, Malone FD, Lambert-Messerlian G, et al. Maternal thyroid hypofunction and pregnancy outcome. Obstet Gynecol 2008; 112(1):85–92. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181788dd7

- Li Y, Shan Z, Teng W, et al. Abnormalities of maternal thyroid function during pregnancy affect neuropsychological development of their children at 25-30 months. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2010; 72(6):825–829. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2265.2009.03743.x

- Haddow JE, Palomaki GE, Allan WC, et al. Maternal thyroid deficiency during pregnancy and subsequent neuropsychological development of the child. N Engl J Med 1999; 341(8):549–555. doi:10.1056/NEJM199908193410801

- Henrichs J, Bongers-Schokking JJ, Schenk JJ, et al. Maternal thyroid function during early pregnancy and cognitive functioning in early childhood: the generation R study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2010; 95(9):4227–4234. doi:10.1210/jc.2010-0415

- Behrooz HG, Tohidi M, Mehrabi Y, Behrooz EG, Tehranidoost M, Azizi F. Subclinical hypothyroidism in pregnancy: intellectual development of offspring. Thyroid 2011; 21(10):1143–1147. doi:10.1089/thy.2011.0053

- Julvez J, Alvarez-Pedrerol M, Rebagliato M, et al. Thyroxine levels during pregnancy in healthy women and early child neurodevelopment. Epidemiology 2013; 24(1):150–157. doi:10.1097/EDE.0b013e318276ccd3

- Casey BM, Thom EA, Peaceman AM, et al; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal–Fetal Medicine Units Network. Treatment of subclinical hypothyroidism or hypothyroxinemia in pregnancy. N Engl J Med 2017; 376(9):815–825. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1606205

- Burns RB, Bates CK, Hartzband P, Smetana GW. Should we treat for subclinical hypothyroidism?: Grand rounds discussion from Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. Ann Intern Med 2016; 164(11):764–770. doi:10.7326/M16-0857

- Kucukler FK, Akbaba G, Arduc A, Simsek Y, Guler S. Evaluation of the common mistakes made by patients in the use of levothyroxine. Eur J Intern Med 2014; 25(9):e107–e108. doi:10.1016/j.ejim.2014.09.002

- McMillan M, Rotenberg KS, Vora K, et al. Comorbidities, concomitant medications, and diet as factors affecting levothyroxine therapy: results of the CONTROL surveillance project. Drugs R D 2016; 16(1):53–68. doi:10.1007/s40268-015-0116-6

- Pollock MA, Sturrock A, Marshall K, et al. Thyroxine treatment in patients with symptoms of hypothyroidism but thyroid function tests within the reference range: Randomised double blind placebo controlled crossover trial. BMJ 2001; 323(7318):891–895. pmid:11668132

- Peeters RP. Subclinical hypothyroidism. N Engl J Med 2017; 376(26):2556–2565. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1611144

Whether subclinical hypothyroidism is clinically important and should be treated remains controversial. Studies have differed in their findings, and although most have found this condition to be associated with a variety of adverse outcomes, large randomized controlled trials are needed to clearly demonstrate its clinical impact in various age groups and the benefit of levothyroxine therapy.

Currently, the best practical approach is to base treatment decisions on the magnitude of elevation of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) and whether the patient has thyroid autoantibodies and associated comorbid conditions.

HIGH TSH, NORMAL FREE T4 LEVELS

Subclinical hypothyroidism is defined by elevated TSH along with a normal free thyroxine (T4).1

The hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis is a balanced homeostatic system, and TSH and thyroid hormone levels have an inverse log-linear relation: if free T4 and triiodothyronine (T3) levels go down even a little, TSH levels go up a lot.2

TSH secretion is pulsatile and has a circadian rhythm: serum TSH levels are 50% higher at night and early in the morning than during the rest of the day. Thus, repeated measurements in the same patient can vary by as much as half of the reference range.3

WHAT IS THE UPPER LIMIT OF NORMAL FOR TSH?

The upper limit of normal for TSH, defined as the 97.5th percentile, is approximately 4 or 5 mIU/L depending on the laboratory and the population, but some experts believe it should be lower.3

In favor of a lower upper limit: the distribution of serum TSH levels in the healthy general population does not seem to be a typical bell-shaped Gaussian curve, but rather has a tail at the high end. Some argue that some of the individuals with values in the upper end of the normal range may actually have undiagnosed hypothyroidism and that the upper 97.5th percentile cutoff would be 2.5 mIU/L if these people were excluded.4 Also, TSH levels higher than 2.5 mIU/L have been associated with a higher prevalence of antithyroid antibodies and a higher risk of clinical hypothyroidism.5

On the other hand, lowering the upper limit of normal to 2.5 mIU/L would result in 4 times as many people receiving a diagnosis of subclinical hypothyroidism, or 22 to 28 million people in the United States.4,6 Thus, lowering the cutoff may lead to unnecessary therapy and could even harm from overtreatment.

Another argument against lowering the upper limit of normal for TSH is that, with age, serum TSH levels shift higher.7 The third National Health and Nutrition Education Survey (NHANES III) found that the 97.5th percentile for serum TSH was 3.56 mIU/L for age group 20 to 29 but 7.49 mIU/L for octogenarians.7,8

It has been suggested that the upper limit of normal for TSH be adjusted for age, race, sex, and iodine intake.3 Currently available TSH reference ranges are not adjusted for these variables, and there is not enough evidence to suggest age-appropriate ranges,9 although higher TSH cutoffs for treatment are advised in elderly patients.10 Interestingly, higher TSH in older people has been linked to lower mortality rates in some studies.11

Authors of the NHANES III8 and Hanford Thyroid Disease study12 have proposed a cutoff of 4.1 mIU/L for the upper limit of normal for serum TSH in patients with negative antithyroid antibodies and normal findings on thyroid ultrasonography.

SUBCLINICAL HYPOTHYROIDISM IS COMMON

In different studies, the prevalence of subclinical hypothyroidism has been as low as 4% and as high as 20%.1,8,13 The prevalence is higher in women and increases with age.8 It is higher in iodine-sufficient areas, and it increases in iodine-deficient areas with iodine supplementation.14 Genetics also plays a role, as subclinical hypothyroidism is more common in white people than in African Americans.8

A difficulty in estimating the prevalence is the disagreement about the cutoff for TSH, which may differ from that in the general population in certain subgroups such as adolescents, the elderly, and pregnant women.10,15

A VARIETY OF CAUSES

The most common cause of subclinical hypothyroidism, accounting for 60% to 80% of cases, is Hashimoto (autoimmune) thyroiditis,2 in which thyroid peroxidase antibodies are usually present.2,16

Also important to rule out are false-positive elevations due to substances that interfere with TSH assays (eg, heterophile antibodies, rheumatoid factor, biotin, macro-TSH); reversible causes such as the recovery phase of euthyroid sick syndrome; subacute, painless, or postpartum thyroiditis; central hypo- or hyperthyroidism; and thyroid hormone resistance.

SUBCLINICAL HYPOTHYROIDISM CAN RESOLVE OR PROGRESS

“Subclinical” suggests that the disease is in its early stage, with changes in TSH already apparent but decreases in thyroid hormone levels yet to come.17 And indeed, subclinical hypothyroidism can progress to overt hypothyroidism,18 although it has been reported to resolve spontaneously in half of cases within 2 years,19 typically in patients with TSH values of 4 to 6 mIU/L.20 The rate of progression to overt hypothyroidism is estimated to be 33% to 55% over 10 to 20 years of follow-up.18

Figure 1 shows the natural history of subclinical hypothyroidism.1

GUIDELINES FOR SCREENING DIFFER

Guidelines differ on screening for thyroid disease in the general population, owing to lack of large-scale randomized controlled trials showing treatment benefit in otherwise-healthy people with mildly elevated TSH values.

Various professional societies have adopted different criteria for aggressive case-finding in patients at risk of thyroid disease. Risk factors include family history of thyroid disease, neck irradiation, partial thyroidectomy, dyslipidemia, atrial fibrillation, unexplained weight loss, hyperprolactinemia, autoimmune disorders, and use of medications affecting thyroid function.23

The US Preventive Services Task Force in 2014 found insufficient evidence on the benefits and harms of screening.24

The American Thyroid Association (ATA) recommends screening adults starting at age 35, with repeat testing every 5 years in patients who have no signs or symptoms of hypothyroidism, and more frequently in those who do.25

The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists recommends screening in women and older patients. Their guidelines and those of the ATA also suggest screening people at high risk of thyroid disease due to risk factors such as history of autoimmune diseases, neck irradiation, or medications affecting thyroid function.26

The American Academy of Family Physicians recommends screening after age 60.18

The American College of Physicians recommends screening patients over age 50 who have symptoms.18

Our approach. Although evidence is lacking to recommend routine screening in adults, aggressive case-finding and treatment in patients at risk of thyroid disease can, we believe, offset the risks associated with subclinical hypothyroidism.24

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

About 70% of patients with subclinical hypothyroidism have no symptoms.13

Tiredness was more common in subclinical hypothyroid patients with TSH levels lower than 10 mIU/L compared with euthyroid controls in 1 study, but other studies have been unable to replicate this finding.27,28

Other frequently reported symptoms include dry skin, cognitive slowing, poor memory, muscle weakness, cold intolerance, constipation, puffy eyes, and hoarseness.13

The evidence in favor of levothyroxine therapy to improve symptoms in subclinical hypothyroidism has varied, with some studies showing an improvement in symptom scores compared with placebo, while others have not shown any benefit.29–31

In one study, the average TSH value for patients whose symptoms did not improve with therapy was 4.6 mIU/L.31 An explanation for the lack of effect in this group may be that the TSH values for these patients were in the high-normal range. Also, because most subclinical hypothyroid patients have no symptoms, it is difficult to ascertain symptomatic improvement. Though it is possible to conclude that levothyroxine therapy has a limited role in this group, it is important to also consider the suggestive evidence that untreated subclinical hypothyroidism may lead to increased morbidity and mortality.

ADVERSE EFFECTS OF SUBCLINICAL HYPOTHYROIDISM, EFFECTS OF THERAPY

INDIVIDUALIZED MANAGEMENT AND SHARED DECISION-MAKING

The management of subclinical hypothyroidism should be individualized on the basis of extent of thyroid dysfunction, comorbid conditions, risk factors, and patient preference.118 Shared decision-making is key, weighing the risks and benefits of levothyroxine treatment and the patient’s goals.

The risks of treatment should be kept in mind and explained to the patient. Levothyroxine has a narrow therapeutic range, causing a possibility of overreplacement, and a half-life of 7 days that can cause dosing errors to have longer effect.118,119

Adherence can be a challenge. The drug needs to be taken on an empty stomach because foods and supplements interfere with its absorption.118,120 In addition, the cost of medication, frequent biochemical monitoring, and possible need for titration can add to financial burden.

When choosing the dose, one should consider the degree of hypothyroidism or TSH elevation and the patient’s weight, and adjust the dose gently.

If the TSH is high-normal

It is proposed that a TSH range of 3 to 5 mIU/L overlaps with normal thyroid function in a great segment of the population, and at this level it is probably not associated with clinically significant consequences. For these reasons, levothyroxine therapy is not thought to be beneficial for those with TSH in this range.

Pollock et al121 found that, in patients with symptoms suggesting hypothyroidism and TSH values in the upper end of the normal range, there was no improvement in cognitive function or psychological well-being after 12 weeks of levothyroxine therapy.

However, due to the concern for possible adverse maternal and fetal outcomes and low IQ in children of pregnant patients with subclinical hypothyroidism, levothyroxine therapy is advised in those who are pregnant or planning pregnancy who have TSH levels higher than 2.5 mIU/L, especially if they have thyroid peroxidase antibody. Levothyroxine therapy is not recommended for pregnant patients with negative thyroid peroxidase antibody and TSH within the pregnancy-specific range or less than 4 mIU/L if the reference ranges are unavailable.

Keep in mind that, even at these TSH values, there is risk of progression to overt hypothyroidism, especially in the presence of thyroid peroxidase antibody, so patients in this group should be monitored closely.

If TSH is mildly elevated

The evidence to support levothyroxine therapy in patients with subclinical hypothyroidism with TSH levels less than 10 mIU/L remains inconclusive, and the decision to treat should be based on clinical judgment.2 The studies that have looked at the benefit of treating subclinical hypothyroidism in terms of cardiac, neuromuscular, cognitive, and neuropsychiatric outcomes have included patients with a wide range of TSH levels, and some of these studies were not stratified on the basis of degree of TSH elevation.

The risk that subclinical hypothyroidism will progress to overt hypothyroidism in patients with TSH higher than 8 mIU/L is high, and in 70% of these patients, the TSH level rises to more than 10 mIU/L within 4 years. Early treatment should be considered if the TSH is higher than 7 or 8 mIU/L.

If TSH is higher than 10 mIU/L

Figure 2 outlines an algorithmic approach to subclinical hypothyroidism in nonpregnant patients as suggested by Peeters.122

Whether subclinical hypothyroidism is clinically important and should be treated remains controversial. Studies have differed in their findings, and although most have found this condition to be associated with a variety of adverse outcomes, large randomized controlled trials are needed to clearly demonstrate its clinical impact in various age groups and the benefit of levothyroxine therapy.

Currently, the best practical approach is to base treatment decisions on the magnitude of elevation of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) and whether the patient has thyroid autoantibodies and associated comorbid conditions.

HIGH TSH, NORMAL FREE T4 LEVELS

Subclinical hypothyroidism is defined by elevated TSH along with a normal free thyroxine (T4).1

The hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis is a balanced homeostatic system, and TSH and thyroid hormone levels have an inverse log-linear relation: if free T4 and triiodothyronine (T3) levels go down even a little, TSH levels go up a lot.2

TSH secretion is pulsatile and has a circadian rhythm: serum TSH levels are 50% higher at night and early in the morning than during the rest of the day. Thus, repeated measurements in the same patient can vary by as much as half of the reference range.3

WHAT IS THE UPPER LIMIT OF NORMAL FOR TSH?

The upper limit of normal for TSH, defined as the 97.5th percentile, is approximately 4 or 5 mIU/L depending on the laboratory and the population, but some experts believe it should be lower.3

In favor of a lower upper limit: the distribution of serum TSH levels in the healthy general population does not seem to be a typical bell-shaped Gaussian curve, but rather has a tail at the high end. Some argue that some of the individuals with values in the upper end of the normal range may actually have undiagnosed hypothyroidism and that the upper 97.5th percentile cutoff would be 2.5 mIU/L if these people were excluded.4 Also, TSH levels higher than 2.5 mIU/L have been associated with a higher prevalence of antithyroid antibodies and a higher risk of clinical hypothyroidism.5

On the other hand, lowering the upper limit of normal to 2.5 mIU/L would result in 4 times as many people receiving a diagnosis of subclinical hypothyroidism, or 22 to 28 million people in the United States.4,6 Thus, lowering the cutoff may lead to unnecessary therapy and could even harm from overtreatment.

Another argument against lowering the upper limit of normal for TSH is that, with age, serum TSH levels shift higher.7 The third National Health and Nutrition Education Survey (NHANES III) found that the 97.5th percentile for serum TSH was 3.56 mIU/L for age group 20 to 29 but 7.49 mIU/L for octogenarians.7,8

It has been suggested that the upper limit of normal for TSH be adjusted for age, race, sex, and iodine intake.3 Currently available TSH reference ranges are not adjusted for these variables, and there is not enough evidence to suggest age-appropriate ranges,9 although higher TSH cutoffs for treatment are advised in elderly patients.10 Interestingly, higher TSH in older people has been linked to lower mortality rates in some studies.11

Authors of the NHANES III8 and Hanford Thyroid Disease study12 have proposed a cutoff of 4.1 mIU/L for the upper limit of normal for serum TSH in patients with negative antithyroid antibodies and normal findings on thyroid ultrasonography.

SUBCLINICAL HYPOTHYROIDISM IS COMMON

In different studies, the prevalence of subclinical hypothyroidism has been as low as 4% and as high as 20%.1,8,13 The prevalence is higher in women and increases with age.8 It is higher in iodine-sufficient areas, and it increases in iodine-deficient areas with iodine supplementation.14 Genetics also plays a role, as subclinical hypothyroidism is more common in white people than in African Americans.8

A difficulty in estimating the prevalence is the disagreement about the cutoff for TSH, which may differ from that in the general population in certain subgroups such as adolescents, the elderly, and pregnant women.10,15

A VARIETY OF CAUSES

The most common cause of subclinical hypothyroidism, accounting for 60% to 80% of cases, is Hashimoto (autoimmune) thyroiditis,2 in which thyroid peroxidase antibodies are usually present.2,16

Also important to rule out are false-positive elevations due to substances that interfere with TSH assays (eg, heterophile antibodies, rheumatoid factor, biotin, macro-TSH); reversible causes such as the recovery phase of euthyroid sick syndrome; subacute, painless, or postpartum thyroiditis; central hypo- or hyperthyroidism; and thyroid hormone resistance.

SUBCLINICAL HYPOTHYROIDISM CAN RESOLVE OR PROGRESS

“Subclinical” suggests that the disease is in its early stage, with changes in TSH already apparent but decreases in thyroid hormone levels yet to come.17 And indeed, subclinical hypothyroidism can progress to overt hypothyroidism,18 although it has been reported to resolve spontaneously in half of cases within 2 years,19 typically in patients with TSH values of 4 to 6 mIU/L.20 The rate of progression to overt hypothyroidism is estimated to be 33% to 55% over 10 to 20 years of follow-up.18

Figure 1 shows the natural history of subclinical hypothyroidism.1

GUIDELINES FOR SCREENING DIFFER

Guidelines differ on screening for thyroid disease in the general population, owing to lack of large-scale randomized controlled trials showing treatment benefit in otherwise-healthy people with mildly elevated TSH values.

Various professional societies have adopted different criteria for aggressive case-finding in patients at risk of thyroid disease. Risk factors include family history of thyroid disease, neck irradiation, partial thyroidectomy, dyslipidemia, atrial fibrillation, unexplained weight loss, hyperprolactinemia, autoimmune disorders, and use of medications affecting thyroid function.23

The US Preventive Services Task Force in 2014 found insufficient evidence on the benefits and harms of screening.24

The American Thyroid Association (ATA) recommends screening adults starting at age 35, with repeat testing every 5 years in patients who have no signs or symptoms of hypothyroidism, and more frequently in those who do.25

The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists recommends screening in women and older patients. Their guidelines and those of the ATA also suggest screening people at high risk of thyroid disease due to risk factors such as history of autoimmune diseases, neck irradiation, or medications affecting thyroid function.26

The American Academy of Family Physicians recommends screening after age 60.18

The American College of Physicians recommends screening patients over age 50 who have symptoms.18

Our approach. Although evidence is lacking to recommend routine screening in adults, aggressive case-finding and treatment in patients at risk of thyroid disease can, we believe, offset the risks associated with subclinical hypothyroidism.24

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

About 70% of patients with subclinical hypothyroidism have no symptoms.13

Tiredness was more common in subclinical hypothyroid patients with TSH levels lower than 10 mIU/L compared with euthyroid controls in 1 study, but other studies have been unable to replicate this finding.27,28

Other frequently reported symptoms include dry skin, cognitive slowing, poor memory, muscle weakness, cold intolerance, constipation, puffy eyes, and hoarseness.13

The evidence in favor of levothyroxine therapy to improve symptoms in subclinical hypothyroidism has varied, with some studies showing an improvement in symptom scores compared with placebo, while others have not shown any benefit.29–31

In one study, the average TSH value for patients whose symptoms did not improve with therapy was 4.6 mIU/L.31 An explanation for the lack of effect in this group may be that the TSH values for these patients were in the high-normal range. Also, because most subclinical hypothyroid patients have no symptoms, it is difficult to ascertain symptomatic improvement. Though it is possible to conclude that levothyroxine therapy has a limited role in this group, it is important to also consider the suggestive evidence that untreated subclinical hypothyroidism may lead to increased morbidity and mortality.

ADVERSE EFFECTS OF SUBCLINICAL HYPOTHYROIDISM, EFFECTS OF THERAPY

INDIVIDUALIZED MANAGEMENT AND SHARED DECISION-MAKING

The management of subclinical hypothyroidism should be individualized on the basis of extent of thyroid dysfunction, comorbid conditions, risk factors, and patient preference.118 Shared decision-making is key, weighing the risks and benefits of levothyroxine treatment and the patient’s goals.

The risks of treatment should be kept in mind and explained to the patient. Levothyroxine has a narrow therapeutic range, causing a possibility of overreplacement, and a half-life of 7 days that can cause dosing errors to have longer effect.118,119

Adherence can be a challenge. The drug needs to be taken on an empty stomach because foods and supplements interfere with its absorption.118,120 In addition, the cost of medication, frequent biochemical monitoring, and possible need for titration can add to financial burden.

When choosing the dose, one should consider the degree of hypothyroidism or TSH elevation and the patient’s weight, and adjust the dose gently.

If the TSH is high-normal

It is proposed that a TSH range of 3 to 5 mIU/L overlaps with normal thyroid function in a great segment of the population, and at this level it is probably not associated with clinically significant consequences. For these reasons, levothyroxine therapy is not thought to be beneficial for those with TSH in this range.

Pollock et al121 found that, in patients with symptoms suggesting hypothyroidism and TSH values in the upper end of the normal range, there was no improvement in cognitive function or psychological well-being after 12 weeks of levothyroxine therapy.

However, due to the concern for possible adverse maternal and fetal outcomes and low IQ in children of pregnant patients with subclinical hypothyroidism, levothyroxine therapy is advised in those who are pregnant or planning pregnancy who have TSH levels higher than 2.5 mIU/L, especially if they have thyroid peroxidase antibody. Levothyroxine therapy is not recommended for pregnant patients with negative thyroid peroxidase antibody and TSH within the pregnancy-specific range or less than 4 mIU/L if the reference ranges are unavailable.

Keep in mind that, even at these TSH values, there is risk of progression to overt hypothyroidism, especially in the presence of thyroid peroxidase antibody, so patients in this group should be monitored closely.

If TSH is mildly elevated

The evidence to support levothyroxine therapy in patients with subclinical hypothyroidism with TSH levels less than 10 mIU/L remains inconclusive, and the decision to treat should be based on clinical judgment.2 The studies that have looked at the benefit of treating subclinical hypothyroidism in terms of cardiac, neuromuscular, cognitive, and neuropsychiatric outcomes have included patients with a wide range of TSH levels, and some of these studies were not stratified on the basis of degree of TSH elevation.

The risk that subclinical hypothyroidism will progress to overt hypothyroidism in patients with TSH higher than 8 mIU/L is high, and in 70% of these patients, the TSH level rises to more than 10 mIU/L within 4 years. Early treatment should be considered if the TSH is higher than 7 or 8 mIU/L.

If TSH is higher than 10 mIU/L

Figure 2 outlines an algorithmic approach to subclinical hypothyroidism in nonpregnant patients as suggested by Peeters.122

- Cooper DS, Biondi B. Subclinical thyroid disease. Lancet 2012; 379(9821):1142–1154. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60276-6

- Fatourechi V. Subclinical hypothyroidism: an update for primary care physicians. Mayo Clin Proc 2009; 84(1):65–71. doi:10.4065/84.1.65

- Laurberg P, Andersen S, Carle A, Karmisholt J, Knudsen N, Pedersen IB. The TSH upper reference limit: where are we at? Nat Rev Endocrinol 2011; 7(4):232–239. doi:10.1038/nrendo.2011.13

- Wartofsky L, Dickey RA. The evidence for a narrower thyrotropin reference range is compelling. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2005; 90(9):5483–5488. doi:10.1210/jc.2005-0455

- Spencer CA, Hollowell JG, Kazarosyan M, Braverman LE. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH)-thyroperoxidase antibody relationships demonstrate that TSH upper reference limits may be skewed by occult thyroid dysfunction. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007; 92(11):4236–4240. doi:10.1210/jc.2007-0287

- Fatourechi V, Klee GG, Grebe SK, et al. Effects of reducing the upper limit of normal TSH values. JAMA 2003; 290(24):3195–3196. doi:10.1001/jama.290.24.3195-a

- Surks MI, Hollowell JG. Age-specific distribution of serum thyrotropin and antithyroid antibodies in the US population: implications for the prevalence of subclinical hypothyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007; 92(12):4575–4582. doi:10.1210/jc.2007-1499

- Hollowell JG, Staehling NW, Flanders WD, et al. Serum TSH, T(4), and thyroid antibodies in the United States population (1988 to 1994): National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III). J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2002; 87(2):489–499. doi:10.1210/jcem.87.2.8182

- Jonklaas J, Bianco AC, Bauer AJ, et al; American Thyroid Association Task Force on Thyroid Hormone Replacement. Guidelines for the treatment of hypothyroidism: prepared by the American Thyroid Association Task Force on Thyroid Hormone Replacement. Thyroid 2014; 24(12):1670–1751. doi:10.1089/thy.2014.0028

- Hennessey JV, Espaillat R. Diagnosis and management of subclinical hypothyroidism in elderly adults: a review of the literature. J Am Geriatr Soc 2015; 63(8):1663–1673. doi:10.1111/jgs.13532

- Razvi S, Shakoor A, Vanderpump M, Weaver JU, Pearce SH. The influence of age on the relationship between subclinical hypothyroidism and ischemic heart disease: a metaanalysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008; 93(8):2998–3007. doi:10.1210/jc.2008-0167

- Hamilton TE, Davis S, Onstad L, Kopecky KJ. Thyrotropin levels in a population with no clinical, autoantibody, or ultrasonographic evidence of thyroid disease: implications for the diagnosis of subclinical hypothyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008; 93(4):1224–1230. doi:10.1210/jc.2006-2300

- Canaris GJ, Manowitz NR, Mayor G, Ridgway EC. The Colorado thyroid disease prevalence study. Arch Intern Med 2000; 160(4):526–534. pmid:10695693

- Teng W, Shan Z, Teng X, et al. Effect of iodine intake on thyroid diseases in China. N Engl J Med 2006; 354(26):2783–2793. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa054022

- Negro R, Stagnaro-Green A. Diagnosis and management of subclinical hypothyroidism in pregnancy. BMJ 2014; 349:g4929. doi:10.1136/bmj.g4929

- Baumgartner C, Blum MR, Rodondi N. Subclinical hypothyroidism: summary of evidence in 2014. Swiss Med Wkly 2014; 144:w14058. doi:10.4414/smw.2014.14058

- Stedman TL. Stedman’s Medical Dictionary. 28th ed. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2006.

- Raza SA, Mahmood N. Subclinical hypothyroidism: controversies to consensus. Indian J Endocrinol Metab 2013; 17(suppl 3):S636–S642. doi:10.4103/2230-8210.123555

- Huber G, Staub JJ, Meier C, et al. Prospective study of the spontaneous course of subclinical hypothyroidism: prognostic value of thyrotropin, thyroid reserve, and thyroid antibodies. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2002; 87(7):3221–3226. doi:10.1210/jcem.87.7.8678

- Diez JJ, Iglesias P, Burman KD. Spontaneous normalization of thyrotropin concentrations in patients with subclinical hypothyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2005; 90(7):4124–4127. doi:10.1210/jc.2005-0375

- Vanderpump MP, Tunbridge WM, French JM, et al. The incidence of thyroid disorders in the community: a twenty-year follow-up of the Whickham survey. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1995; 43(1):55–68. pmid:7641412

- Li Y, Teng D, Shan Z, et al. Antithyroperoxidase and antithyroglobulin antibodies in a five-year follow-up survey of populations with different iodine intakes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008; 93(5):1751–1757. doi:10.1210/jc.2007-2368

- Hennessey JV, Klein I, Woeber KA, Cobin R, Garber JR. Aggressive case finding: a clinical strategy for the documentation of thyroid dysfunction. Ann Intern Med 2015; 163(4):311–312. doi:10.7326/M15-0762

- Rugge JB, Bougatsos C, Chou R. Screening and treatment of thyroid dysfunction: an evidence review for the US.Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med 2015; 162(1):35–45. doi:10.7326/M14-1456

- Ladenson PW, Singer PA, Ain KB, et al. American Thyroid Association guidelines for detection of thyroid dysfunction. Arch Intern Med 2000; 160(11):1573–1575. pmid:10847249

- Garber JR, Cobin RH, Gharib H, et al; American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American Thyroid Association Taskforce on Hypothyroidism in Adults. Clinical practice guidelines for hypothyroidism in adults: cosponsored by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and the American Thyroid Association. Endocr Pract 2012; 18(6):988–1028. doi:10.4158/EP12280.GL

- Jorde R, Waterloo K, Storhaug H, Nyrnes A, Sundsfjord J, Jenssen TG. Neuropsychological function and symptoms in subjects with subclinical hypothyroidism and the effect of thyroxine treatment. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006; 91(1):145–153. doi:10.1210/jc.2005-1775

- Joffe RT, Pearce EN, Hennessey JV, Ryan JJ, Stern RA. Subclinical hypothyroidism, mood, and cognition in older adults: a review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2013; 28(2):111–118. doi:10.1002/gps.3796

- Cooper DS, Halpern R, Wood LC, Levin AA, Ridgway EC. L-thyroxine therapy in subclinical hypothyroidism. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 1984; 101(1):18–24. pmid:6428290

- Nystrom E, Caidahl K, Fager G, Wikkelso C, Lundberg PA, Lindstedt G. A double-blind cross-over 12-month study of L-thyroxine treatment of women with ‘subclinical’ hypothyroidism. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1988; 29(1):63–75. pmid:3073880

- Monzani F, Del Guerra P, Caraccio N, et al. Subclinical hypothyroidism: neurobehavioral features and beneficial effect of L-thyroxine treatment. Clin Investig 1993; 71(5):367–371. pmid:8508006

- Biondi B. Thyroid and obesity: an intriguing relationship. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2010; 95(8):3614–3617. doi:10.1210/jc.2010-1245

- Erdogan M, Canataroglu A, Ganidagli S, Kulaksizoglu M. Metabolic syndrome prevalence in subclinic and overt hypothyroid patients and the relation among metabolic syndrome parameters. J Endocrinol Invest 2011; 34(7):488–492. doi:10.3275/7202

- Javed Z, Sathyapalan T. Levothyroxine treatment of mild subclinical hypothyroidism: a review of potential risks and benefits. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab 2016; 7(1):12–23. doi:10.1177/2042018815616543

- Pearce SH, Brabant G, Duntas LH, et al. 2013 ETA guideline: management of subclinical hypothyroidism. Eur Thyroid J 2013; 2(4):215–228. doi:10.1159/000356507

- Wang C. The relationship between type 2 diabetes mellitus and related thyroid diseases. J Diabetes Res 2013; 2013:390534. doi:10.1155/2013/390534

- Razvi S, Weaver JU, Vanderpump MP, Pearce SH. The incidence of ischemic heart disease and mortality in people with subclinical hypothyroidism: reanalysis of the Whickham survey cohort. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2010; 95(4):1734–1740. doi:10.1210/jc.2009-1749

- Bindels AJ, Westendorp RG, Frolich M, Seidell JC, Blokstra A, Smelt AH. The prevalence of subclinical hypothyroidism at different total plasma cholesterol levels in middle aged men and women: a need for case-finding? Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1999; 50(2):217–220. pmid:10396365

- Pearce EN. Hypothyroidism and dyslipidemia: modern concepts and approaches. Curr Cardiol Rep 2004; 6(6):451–456. pmid:15485607

- Pearce EN. Update in lipid alterations in subclinical hypothyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012; 97(2):326–333. doi:10.1210/jc.2011-2532

- Rizos CV, Elisaf MS, Liberopoulos EN. Effects of thyroid dysfunction on lipid profile. Open Cardiovasc Med J 2011; 5:76–84. doi:10.2174/1874192401105010076

- Peppa M, Betsi G, Dimitriadis G. Lipid abnormalities and cardiometabolic risk in patients with overt and subclinical thyroid disease. J Lipids 2011; 2011:575840. doi:10.1155/2011/575840

- Asvold BO, Vatten LJ, Nilsen TI, Bjoro T. The association between TSH within the reference range and serum lipid concentrations in a population-based study. the HUNT study. Eur J Endocrinol 2007;1 56(2):181–186. doi:10.1530/eje.1.02333

- Danese MD, Ladenson PW, Meinert CL, Powe NR. Clinical review 115: effect of thyroxine therapy on serum lipoproteins in patients with mild thyroid failure: a quantitative review of the literature. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2000; 85(9):2993–3001. doi:10.1210/jcem.85.9.6841

- Razvi S, Ingoe L, Keeka G, Oates C, McMillan C, Weaver JU. The beneficial effect of L-thyroxine on cardiovascular risk factors, endothelial function, and quality of life in subclinical hypothyroidism: randomized, crossover trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007; 92(5):1715–1723. doi:10.1210/jc.2006-1869

- Abreu IM, Lau E, de Sousa Pinto B, Carvalho D. Subclinical hypothyroidism: to treat or not to treat, that is the question! A systematic review with meta-analysis on lipid profile. Endocr Connect 2017; 6(3):188–199. doi:10.1530/EC-17-0028

- Robison CD, Bair TL, Horne BD, et al. Hypothyroidism as a risk factor for statin intolerance. J Clin Lipidol 2014; 8(4):401–407. doi:10.1016/j.jacl.2014.05.005

- Hak AE, Pols HA, Visser TJ, Drexhage HA, Hofman A, Witteman JC. Subclinical hypothyroidism is an independent risk factor for atherosclerosis and myocardial infarction in elderly women: the Rotterdam study. Ann Intern Med 2000; 132(4):270–278. pmid:10681281

- Boekholdt SM, Titan SM, Wiersinga WM, et al. Initial thyroid status and cardiovascular risk factors: the EPIC-Norfolk prospective population study. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2010; 72(3):404–410. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2265.2009.03640.x

- Andersen MN, Olsen AM, Madsen JC, et al. Levothyroxine substitution in patients with subclinical hypothyroidism and the risk of myocardial infarction and mortality. PLoS One 2015; 10(6):e0129793. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0129793

- Biondi B. Cardiovascular effects of mild hypothyroidism. Thyroid 2007; 17(7):625–630. doi:10.1089/thy.2007.0158

- Brenta G, Mutti LA, Schnitman M, Fretes O, Perrone A, Matute ML. Assessment of left ventricular diastolic function by radionuclide ventriculography at rest and exercise in subclinical hypothyroidism, and its response to L-thyroxine therapy. Am J Cardiol 2003; 91(11):1327–1330. pmid:12767425

- Taddei S, Caraccio N, Virdis A, et al. Impaired endothelium-dependent vasodilatation in subclinical hypothyroidism: beneficial effect of levothyroxine therapy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003; 88(8):3731–3737. doi:10.1210/jc.2003-030039

- Gao N, Zhang W, Zhang YZ, Yang Q, Chen SH. Carotid intima-media thickness in patients with subclinical hypothyroidism: a meta-analysis. Atherosclerosis 2013; 227(1):18–25. doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2012.10.070

- Biondi B, Cooper DS. The clinical significance of subclinical thyroid dysfunction. Endocr Rev 2008; 29(1):76–131. doi:10.1210/er.2006-0043

- Chaker L, Baumgartner C, den Elzen WP, et al; Thyroid Studies Collaboration. Subclinical hypothyroidism and the risk of stroke events and fatal stroke: an individual participant data analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2015; 100(6):2181–2191. doi:10.1210/jc.2015-1438

- Monzani F, Di Bello V, Caraccio N, et al. Effect of levothyroxine on cardiac function and structure in subclinical hypothyroidism: a double blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2001; 86(3):1110–1115. doi:10.1210/jcem.86.3.7291

- Parle JV, Maisonneuve P, Sheppard MC, Boyle P, Franklyn JA. Prediction of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in elderly people from one low serum thyrotropin result: a 10-year cohort study. Lancet 2001; 358(9285):861-865. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06067-6

- Razvi S, Weaver JU, Butler TJ, Pearce SH. Levothyroxine treatment of subclinical hypothyroidism, fatal and nonfatal cardiovascular events, and mortality. Arch Intern Med 2012; 172(10):811–817. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2012.1159

- Pasqualetti G, Tognini S, Polini A, Caraccio N, Monzani F. Is subclinical hypothyroidism a cardiovascular risk factor in the elderly? J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2013; 98(6):2256–2266. doi:10.1210/jc.2012-3818

- Mooijaart SP, IEMO 80-plus Thyroid Trial Collaboration. Subclinical thyroid disorders. Lancet 2012; 380(9839):335. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61241-0

- Rodondi N, Bauer DC. Subclinical hypothyroidism and cardiovascular risk: how to end the controversy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2013; 98(6):2267–2269. doi:10.1210/jc.2013-1875

- Rodondi N, Newman AB, Vittinghoff E, et al. Subclinical hypothyroidism and the risk of heart failure, other cardiovascular events, and death. Arch Intern Med 2005; 165(21):2460–2466. doi:10.1001/archinte.165.21.2460

- Rodondi N, Bauer DC, Cappola AR, et al. Subclinical thyroid dysfunction, cardiac function, and the risk of heart failure. The Cardiovascular Health study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008; 52(14):1152–1159. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2008.07.009

- Haggerty JJ Jr, Garbutt JC, Evans DL, et al. Subclinical hypothyroidism: a review of neuropsychiatric aspects. Int J Psychiatry Med 1990; 20(2):193–208. doi:10.2190/ADLY-1UU0-1A8L-HPXY

- Baldini IM, Vita A, Mauri MC, et al. Psychopathological and cognitive features in subclinical hypothyroidism. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 1997; 21(6):925–935. pmid:9380789

- del Ser Quijano T, Delgado C, Martinez Espinosa S, Vazquez C. Cognitive deficiency in mild hypothyroidism. Neurologia 2000; 15(5):193–198. Spanish. pmid:10850118

- Correia N, Mullally S, Cooke G, et al. Evidence for a specific defect in hippocampal memory in overt and subclinical hypothyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2009; 94(10):3789–3797. doi:10.1210/jc.2008-2702

- Aghili R, Khamseh ME, Malek M, et al. Changes of subtests of Wechsler memory scale and cognitive function in subjects with subclinical hypothyroidism following treatment with levothyroxine. Arch Med Sci 2012; 8(6):1096–1101. doi:10.5114/aoms.2012.32423

- Pasqualetti G, Pagano G, Rengo G, Ferrara N, Monzani F. Subclinical hypothyroidism and cognitive impairment: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2015; 100(11):4240–4248. doi:10.1210/jc.2015-2046

- Christ-Crain M, Meier C, Huber PR, Staub J, Muller B. Effect of L-thyroxine replacement therapy on surrogate markers of skeletal and cardiac function in subclinical hypothyroidism. Endocrinologist 2004; 14(3):161–166. doi:10.1097/01.ten.0000127932.31710.4f

- Brennan MD, Powell C, Kaufman KR, Sun PC, Bahn RS, Nair KS. The impact of overt and subclinical hyperthyroidism on skeletal muscle. Thyroid 2006; 16(4):375–380. doi:10.1089/thy.2006.16.375

- Reuters VS, Teixeira Pde F, Vigario PS, et al. Functional capacity and muscular abnormalities in subclinical hypothyroidism. Am J Med Sci 2009; 338(4):259–263. doi:10.1097/MAJ.0b013e3181af7c7c

- Mainenti MR, Vigario PS, Teixeira PF, Maia MD, Oliveira FP, Vaisman M. Effect of levothyroxine replacement on exercise performance in subclinical hypothyroidism. J Endocrinol Invest 2009; 32(5):470–473. doi:10.3275/6106

- Lankhaar JA, de Vries WR, Jansen JA, Zelissen PM, Backx FJ. Impact of overt and subclinical hypothyroidism on exercise tolerance: a systematic review. Res Q Exerc Sport 2014; 85(3):365–389. doi:10.1080/02701367.2014.930405

- Lee JS, Buzkova P, Fink HA, et al. Subclinical thyroid dysfunction and incident hip fracture in older adults. Arch Intern Med 2010; 170(21):1876–1883. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2010.424

- Svare A, Nilsen TI, Asvold BO, et al. Does thyroid function influence fracture risk? Prospective data from the HUNT2 study, Norway. Eur J Endocrinol 2013; 169(6):845–852. doi:10.1530/EJE-13-0546

- Di Mase R, Cerbone M, Improda N, et al. Bone health in children with long-term idiopathic subclinical hypothyroidism. Ital J Pediatr 2012; 38:56. doi:10.1186/1824-7288-38-56

- Boelaert K. The association between serum TSH concentration and thyroid cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer 2009; 16(4):1065–1072. doi:10.1677/ERC-09-0150

- Haymart MR, Glinberg SL, Liu J, Sippel RS, Jaume JC, Chen H. Higher serum TSH in thyroid cancer patients occurs independent of age and correlates with extrathyroidal extension. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2009; 71(3):434–439. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2265.2008.03489.x

- Fiore E, Vitti P. Serum TSH and risk of papillary thyroid cancer in nodular thyroid disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012; 97(4):1134–1145. doi:10.1210/jc.2011-2735