User login

New limits on resident work hours and the graying of the U.S. population are putting hospitalists in the forefront of helping surgeons manage their patients.

Because the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education restricted resident duty hours, surgeons can no longer rely automatically on residents to medically manage their patients on the floors, says Amir K. Jaffer, MD, a hospitalist and an associate professor of medicine at the Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine of Case Western Reserve University in Ohio.

Meanwhile, the population over age 65 will double, increasing to 70 million over the next 10 to 15 years.1

“More patients living longer means an increase in surgeries along the way,” says Dr. Jaffer, who is also the medical director of the Internal Medicine Preoperative Assessment Consultation and Treatment program in the section of hospital medicine at the Cleveland Clinic. For him, the first place hospitalists need to co-manage is in the postoperative setting.

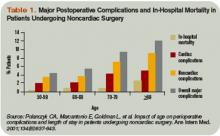

“Studies have suggested that as patients age there is an increase in cardiological complications, noncardiological complications, pulmonary complications, and overall mortality,” he continues. “In my opinion there is going to be a crisis in regard to managing medical issues and complications surrounding surgery.” (See Table 1, p. 24)

Medications issues are another major reason hospitalists are called for surgical consults, says Benny Gavi, MD, hospitalist at Stanford Hospitals and Clinics in Calif. “I got consulted for a patient with tachycardia in the inpatient setting,” says Dr. Gavi. “By the time we saw the patient, the orthopedic surgeon had already ordered an echocardiogram and added a beta-blocker. When I looked at the patient I realized he had a gout flare; the colchicine that he took daily for his gout was never started in the inpatient setting, which ultimately delayed his physical therapy and added three additional days to his hospital stay.”

Co-management makes sense for still other reasons, he says.

“The knowledge base of both surgery and medicine is growing rapidly; no one person can remain on top of what is needed for both fields,” says Dr. Gavi. “In the last 20 years there has been a dramatic rise in the number of medications and some are very complicated. Also, physicians and surgeons both are being approached to participate more in quality initiatives and increasing throughput. As a result, physicians have to work faster and do more.”

Opportunities

In the United States, approximately 100,000 surgeries are performed each day and 36 million surgeries are performed each year at a cost of $450 billion annually. More than 1 million serious surgical adverse events each year cost $45 billion. Within two decades, the surgeries will increase by 25%, the associated cost will increase 50%, and the cost of in-hospital and long-term complications will increase 100%.

Along with postoperative care, there are increasing opportunities in the preoperative setting.

“At our institution, which is a tertiary care center with a huge surgical hospital, we determined that there was a need for hospitalists to provide medical management of surgical patients 10 years ago,” Dr. Jaffer says. “Patients were often not adequately prepared when they went to surgery, and sometimes in the morning of surgery the anesthesiologists would cancel their cases.”

The traditional model of physicians calling in consultants when problems arise might need to change.

“We are increasingly looking for ways to identify patients who have a high likelihood of developing medical problems and proactively getting involved,” says Dr. Gavi.

To co-manage, hospitalists must take ownership of some medical issues under specific conditions (diabetes, anticoagulation, blood pressure), says Dr. Jaffer.

The Benefits

To Latha Sivaprasad, MD, hospitalist at Beth Israel Medical Center in New York City, there are three main advantages of hospitalists’ involvement in perioperative co-management:

- Hospitalists typically perform comprehensive, multisystemic patient evaluations;

- Hospitalists are extremely accessible; and

- Hospitalists are up to date on inpatient medicine.

How up to date?

“Periop isn’t routinely taught in residency,” says Ali Usmani, MD, a hospitalist at the Cleveland Clinic. “In fact, I had little information about perioperative care.”

When he joined the hospitalist group after a three-year residency at Cleveland Clinic, Dr. Usmani did preparatory reading. Later, the hospitalist group gave him a helpful collection of essays.

“I was very nervous because, of course, I had never done this before,” he says. “Surprisingly, I also had not done a general medicine consult service where we see postoperative patients. It was scary to some extent, but I found out that it is easier than I thought because there are guidelines you can follow from the AHA/ACC that are fairly straightforward. It also meant a nice schedule change from being on the floors.”

Although conducting preoperative evaluations with patients was technically outpatient work, it was not like he was seeing patients with such simple illnesses as a cold or a sore throat. Also, he says, there were no new surprises postoperatively because either he or a hospitalist colleague had seen the patient preoperatively.

Dr. Usmani, also a clinical assistant professor of medicine at Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine of Case Western Reserve University, believes patients are happier when seen by hospitalists because they get a standardized, holistic preoperative assessment. And, helping to reduce the number of unnecessary tests ordered by primary care physicians or surgeons makes him feel as though he’s making a valuable contribution.

New Niche

Dr. Sivaprasad, who is also doing a one-year fellowship in quality improvement and patient safety at Beth Israel, has practiced hospital medicine in four hospitals ranging from 500 to 1,000 beds. “The primary reason we are consulted by surgeons is for perioperative cardiac risk assessment,” says Dr. Sivaprasad. “Other reasons include co-managing a patient with comorbidities such as a history of diabetes, hypertension, or renal failure.”

From 2003-2006, Dr. Sivaprasad was one of 14 hospitalists consulted often by surgeons at St. John’s Mercy Hospital in St Louis, a 1,000-bed Level I trauma center. “We were consulted for postoperative co-management, preoperative evaluation, or more urgent cases such as a patient experiencing hypotension, atrial fibrillation, shortness of breath, decreased urine output, or renal failure,” she says.

Dr. Sivaprasad recently attended the Johns Hopkins conference on Perioperative Management. The session made it easier for her to do a systems-based consult.

“All hospitalists differ to the degree of perioperative medicine they feel comfortable with,” she says. “Hospitalists understand perioperative medicine on different levels. They all can do an acceptable consult; but there is a spectrum of how detailed one can be and what service one can provide for the surgeon and the patient.”

Dr. Jaffer finds his work in perioperative care fulfilling and considers it another way hospitalists can increase their influence.

“Often when you manage medical patients in the hospital, it’s you, the medical patient, and the patient’s primary care physician,” Dr. Jaffer says. “But when you start to manage surgical patients, you are really being looked at by your surgical colleagues as an expert in managing medical problems, just as you view them as experts in managing surgical problems. What I realize from this is that I can be a perioperative medicine expert as well.”

Are there any downfalls to co-managing surgical patients?

“Sometimes the surgeons order unnecessary lab tests such as PTTs [partial thromboplastin time] because they are concerned about bleeding and complications,” Dr. Usmani says. “The next day if there is a deranged PTT, we need to figure out whether to suggest postponing the surgery or go ahead with the surgery based on the patients’ past medical/family history. We try to get our surgeons and our colleagues to work together with us in that regard because they don’t want to postpone surgery either.”

Drs. Usmani, Gavi, Jaffer, and Sivaprasad all say that when surgeons can observe firsthand their hospitalist partners exhibiting expertise in acute care it appears to improve surgeons’ attitudes about the role and value of hospitalists.

In fact, says Dr. Usmani, surgeons call him or one of his colleagues to thank them. “They say, ‘We really appreciate what you’ve done for this patient,’ ’’ he says. “Even if we suggest canceling surgery, they respect that we have seen a potential problem instead of letting it go ahead. They are happy to receive this advice.”

Another new relationship is between anesthesiologists and hospitalists. “I spend a lot of time calling anesthesiologists in regard to patient cases, and a good many of them are surprised to get a call from a hospitalist,” Dr. Gavi says. “We especially work closely together when we get complicated patients ready for surgery.”

A recent encounter proved to Dr. Gavi the complementary nature of the hospitalist-anesthesiologist relationship.2

“A patient came to the hospital two weeks ago to have an elective total knee replacement,” says Dr. Gavi. “She was an older woman with severe pulmonary disease. When the anesthesiologists saw her in the preoperative waiting area and realized how sick she is, they wanted to cancel the surgery. But the surgeon told the anesthesiologist that this patient had been seen in our own preoperative clinic and cleared by a hospitalist.”

Dr. Gavi had done what is customary for an internist. He took a more in-depth look at her pulmonology and cardiac records, called her cardiologist for further history, and reassured the anesthesiologist and surgeon. The patient had her surgery.

The Future

“Perioperative co-management is becoming more of a visible need,” says Dr. Sivaprasad. “It bridges the gap between surgeons and internists.”

To those of his hospitalist colleagues who have little information and are a bit afraid to begin perioperative care practice, Dr. Usmani recommends attending a perioperative summit conference.

The session should teach how to set up a perioperative center and what to do when managing patients with certain conditions.

“Although you meet with patients preoperatively in an office setting, you don’t feel like a primary care physician,” Dr. Usmani says. “You feel as if you are a specialist. You are respected, and you are contributing to postoperative outcomes to the benefit of the patient.”

Perioperative patient management is also financially rewarding because reimbursement is higher than customary hospital medicine duties.

Dr. Jaffer, soon to be chief of the division of hospital medicine at the University of Miami Medical Center in Florida, is proud of the work he and his colleagues have done to grow the Cleveland Clinic perioperative summit. This third summit, in September, was organized in collaboration with the Society of Perioperative Assessment and Quality Improvement.

“I think this is something that every hospitalist should try,” Dr. Usmani says. “It is definitely a niche.” TH

Andrea Sattinger is a frequent contributor to The Hospitalist.

References

- Mangano DT. Perioperative medicine: NHLBI working group deliberations and recommendations. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2004;18(1):1-6.

- Adebola O, Adesanya AO, Joshi GP. Hospitalists and anesthesiologists as perioperative physicians: Are their roles complementary? Proc. (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 2007 April;20(2):140-142.

New limits on resident work hours and the graying of the U.S. population are putting hospitalists in the forefront of helping surgeons manage their patients.

Because the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education restricted resident duty hours, surgeons can no longer rely automatically on residents to medically manage their patients on the floors, says Amir K. Jaffer, MD, a hospitalist and an associate professor of medicine at the Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine of Case Western Reserve University in Ohio.

Meanwhile, the population over age 65 will double, increasing to 70 million over the next 10 to 15 years.1

“More patients living longer means an increase in surgeries along the way,” says Dr. Jaffer, who is also the medical director of the Internal Medicine Preoperative Assessment Consultation and Treatment program in the section of hospital medicine at the Cleveland Clinic. For him, the first place hospitalists need to co-manage is in the postoperative setting.

“Studies have suggested that as patients age there is an increase in cardiological complications, noncardiological complications, pulmonary complications, and overall mortality,” he continues. “In my opinion there is going to be a crisis in regard to managing medical issues and complications surrounding surgery.” (See Table 1, p. 24)

Medications issues are another major reason hospitalists are called for surgical consults, says Benny Gavi, MD, hospitalist at Stanford Hospitals and Clinics in Calif. “I got consulted for a patient with tachycardia in the inpatient setting,” says Dr. Gavi. “By the time we saw the patient, the orthopedic surgeon had already ordered an echocardiogram and added a beta-blocker. When I looked at the patient I realized he had a gout flare; the colchicine that he took daily for his gout was never started in the inpatient setting, which ultimately delayed his physical therapy and added three additional days to his hospital stay.”

Co-management makes sense for still other reasons, he says.

“The knowledge base of both surgery and medicine is growing rapidly; no one person can remain on top of what is needed for both fields,” says Dr. Gavi. “In the last 20 years there has been a dramatic rise in the number of medications and some are very complicated. Also, physicians and surgeons both are being approached to participate more in quality initiatives and increasing throughput. As a result, physicians have to work faster and do more.”

Opportunities

In the United States, approximately 100,000 surgeries are performed each day and 36 million surgeries are performed each year at a cost of $450 billion annually. More than 1 million serious surgical adverse events each year cost $45 billion. Within two decades, the surgeries will increase by 25%, the associated cost will increase 50%, and the cost of in-hospital and long-term complications will increase 100%.

Along with postoperative care, there are increasing opportunities in the preoperative setting.

“At our institution, which is a tertiary care center with a huge surgical hospital, we determined that there was a need for hospitalists to provide medical management of surgical patients 10 years ago,” Dr. Jaffer says. “Patients were often not adequately prepared when they went to surgery, and sometimes in the morning of surgery the anesthesiologists would cancel their cases.”

The traditional model of physicians calling in consultants when problems arise might need to change.

“We are increasingly looking for ways to identify patients who have a high likelihood of developing medical problems and proactively getting involved,” says Dr. Gavi.

To co-manage, hospitalists must take ownership of some medical issues under specific conditions (diabetes, anticoagulation, blood pressure), says Dr. Jaffer.

The Benefits

To Latha Sivaprasad, MD, hospitalist at Beth Israel Medical Center in New York City, there are three main advantages of hospitalists’ involvement in perioperative co-management:

- Hospitalists typically perform comprehensive, multisystemic patient evaluations;

- Hospitalists are extremely accessible; and

- Hospitalists are up to date on inpatient medicine.

How up to date?

“Periop isn’t routinely taught in residency,” says Ali Usmani, MD, a hospitalist at the Cleveland Clinic. “In fact, I had little information about perioperative care.”

When he joined the hospitalist group after a three-year residency at Cleveland Clinic, Dr. Usmani did preparatory reading. Later, the hospitalist group gave him a helpful collection of essays.

“I was very nervous because, of course, I had never done this before,” he says. “Surprisingly, I also had not done a general medicine consult service where we see postoperative patients. It was scary to some extent, but I found out that it is easier than I thought because there are guidelines you can follow from the AHA/ACC that are fairly straightforward. It also meant a nice schedule change from being on the floors.”

Although conducting preoperative evaluations with patients was technically outpatient work, it was not like he was seeing patients with such simple illnesses as a cold or a sore throat. Also, he says, there were no new surprises postoperatively because either he or a hospitalist colleague had seen the patient preoperatively.

Dr. Usmani, also a clinical assistant professor of medicine at Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine of Case Western Reserve University, believes patients are happier when seen by hospitalists because they get a standardized, holistic preoperative assessment. And, helping to reduce the number of unnecessary tests ordered by primary care physicians or surgeons makes him feel as though he’s making a valuable contribution.

New Niche

Dr. Sivaprasad, who is also doing a one-year fellowship in quality improvement and patient safety at Beth Israel, has practiced hospital medicine in four hospitals ranging from 500 to 1,000 beds. “The primary reason we are consulted by surgeons is for perioperative cardiac risk assessment,” says Dr. Sivaprasad. “Other reasons include co-managing a patient with comorbidities such as a history of diabetes, hypertension, or renal failure.”

From 2003-2006, Dr. Sivaprasad was one of 14 hospitalists consulted often by surgeons at St. John’s Mercy Hospital in St Louis, a 1,000-bed Level I trauma center. “We were consulted for postoperative co-management, preoperative evaluation, or more urgent cases such as a patient experiencing hypotension, atrial fibrillation, shortness of breath, decreased urine output, or renal failure,” she says.

Dr. Sivaprasad recently attended the Johns Hopkins conference on Perioperative Management. The session made it easier for her to do a systems-based consult.

“All hospitalists differ to the degree of perioperative medicine they feel comfortable with,” she says. “Hospitalists understand perioperative medicine on different levels. They all can do an acceptable consult; but there is a spectrum of how detailed one can be and what service one can provide for the surgeon and the patient.”

Dr. Jaffer finds his work in perioperative care fulfilling and considers it another way hospitalists can increase their influence.

“Often when you manage medical patients in the hospital, it’s you, the medical patient, and the patient’s primary care physician,” Dr. Jaffer says. “But when you start to manage surgical patients, you are really being looked at by your surgical colleagues as an expert in managing medical problems, just as you view them as experts in managing surgical problems. What I realize from this is that I can be a perioperative medicine expert as well.”

Are there any downfalls to co-managing surgical patients?

“Sometimes the surgeons order unnecessary lab tests such as PTTs [partial thromboplastin time] because they are concerned about bleeding and complications,” Dr. Usmani says. “The next day if there is a deranged PTT, we need to figure out whether to suggest postponing the surgery or go ahead with the surgery based on the patients’ past medical/family history. We try to get our surgeons and our colleagues to work together with us in that regard because they don’t want to postpone surgery either.”

Drs. Usmani, Gavi, Jaffer, and Sivaprasad all say that when surgeons can observe firsthand their hospitalist partners exhibiting expertise in acute care it appears to improve surgeons’ attitudes about the role and value of hospitalists.

In fact, says Dr. Usmani, surgeons call him or one of his colleagues to thank them. “They say, ‘We really appreciate what you’ve done for this patient,’ ’’ he says. “Even if we suggest canceling surgery, they respect that we have seen a potential problem instead of letting it go ahead. They are happy to receive this advice.”

Another new relationship is between anesthesiologists and hospitalists. “I spend a lot of time calling anesthesiologists in regard to patient cases, and a good many of them are surprised to get a call from a hospitalist,” Dr. Gavi says. “We especially work closely together when we get complicated patients ready for surgery.”

A recent encounter proved to Dr. Gavi the complementary nature of the hospitalist-anesthesiologist relationship.2

“A patient came to the hospital two weeks ago to have an elective total knee replacement,” says Dr. Gavi. “She was an older woman with severe pulmonary disease. When the anesthesiologists saw her in the preoperative waiting area and realized how sick she is, they wanted to cancel the surgery. But the surgeon told the anesthesiologist that this patient had been seen in our own preoperative clinic and cleared by a hospitalist.”

Dr. Gavi had done what is customary for an internist. He took a more in-depth look at her pulmonology and cardiac records, called her cardiologist for further history, and reassured the anesthesiologist and surgeon. The patient had her surgery.

The Future

“Perioperative co-management is becoming more of a visible need,” says Dr. Sivaprasad. “It bridges the gap between surgeons and internists.”

To those of his hospitalist colleagues who have little information and are a bit afraid to begin perioperative care practice, Dr. Usmani recommends attending a perioperative summit conference.

The session should teach how to set up a perioperative center and what to do when managing patients with certain conditions.

“Although you meet with patients preoperatively in an office setting, you don’t feel like a primary care physician,” Dr. Usmani says. “You feel as if you are a specialist. You are respected, and you are contributing to postoperative outcomes to the benefit of the patient.”

Perioperative patient management is also financially rewarding because reimbursement is higher than customary hospital medicine duties.

Dr. Jaffer, soon to be chief of the division of hospital medicine at the University of Miami Medical Center in Florida, is proud of the work he and his colleagues have done to grow the Cleveland Clinic perioperative summit. This third summit, in September, was organized in collaboration with the Society of Perioperative Assessment and Quality Improvement.

“I think this is something that every hospitalist should try,” Dr. Usmani says. “It is definitely a niche.” TH

Andrea Sattinger is a frequent contributor to The Hospitalist.

References

- Mangano DT. Perioperative medicine: NHLBI working group deliberations and recommendations. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2004;18(1):1-6.

- Adebola O, Adesanya AO, Joshi GP. Hospitalists and anesthesiologists as perioperative physicians: Are their roles complementary? Proc. (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 2007 April;20(2):140-142.

New limits on resident work hours and the graying of the U.S. population are putting hospitalists in the forefront of helping surgeons manage their patients.

Because the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education restricted resident duty hours, surgeons can no longer rely automatically on residents to medically manage their patients on the floors, says Amir K. Jaffer, MD, a hospitalist and an associate professor of medicine at the Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine of Case Western Reserve University in Ohio.

Meanwhile, the population over age 65 will double, increasing to 70 million over the next 10 to 15 years.1

“More patients living longer means an increase in surgeries along the way,” says Dr. Jaffer, who is also the medical director of the Internal Medicine Preoperative Assessment Consultation and Treatment program in the section of hospital medicine at the Cleveland Clinic. For him, the first place hospitalists need to co-manage is in the postoperative setting.

“Studies have suggested that as patients age there is an increase in cardiological complications, noncardiological complications, pulmonary complications, and overall mortality,” he continues. “In my opinion there is going to be a crisis in regard to managing medical issues and complications surrounding surgery.” (See Table 1, p. 24)

Medications issues are another major reason hospitalists are called for surgical consults, says Benny Gavi, MD, hospitalist at Stanford Hospitals and Clinics in Calif. “I got consulted for a patient with tachycardia in the inpatient setting,” says Dr. Gavi. “By the time we saw the patient, the orthopedic surgeon had already ordered an echocardiogram and added a beta-blocker. When I looked at the patient I realized he had a gout flare; the colchicine that he took daily for his gout was never started in the inpatient setting, which ultimately delayed his physical therapy and added three additional days to his hospital stay.”

Co-management makes sense for still other reasons, he says.

“The knowledge base of both surgery and medicine is growing rapidly; no one person can remain on top of what is needed for both fields,” says Dr. Gavi. “In the last 20 years there has been a dramatic rise in the number of medications and some are very complicated. Also, physicians and surgeons both are being approached to participate more in quality initiatives and increasing throughput. As a result, physicians have to work faster and do more.”

Opportunities

In the United States, approximately 100,000 surgeries are performed each day and 36 million surgeries are performed each year at a cost of $450 billion annually. More than 1 million serious surgical adverse events each year cost $45 billion. Within two decades, the surgeries will increase by 25%, the associated cost will increase 50%, and the cost of in-hospital and long-term complications will increase 100%.

Along with postoperative care, there are increasing opportunities in the preoperative setting.

“At our institution, which is a tertiary care center with a huge surgical hospital, we determined that there was a need for hospitalists to provide medical management of surgical patients 10 years ago,” Dr. Jaffer says. “Patients were often not adequately prepared when they went to surgery, and sometimes in the morning of surgery the anesthesiologists would cancel their cases.”

The traditional model of physicians calling in consultants when problems arise might need to change.

“We are increasingly looking for ways to identify patients who have a high likelihood of developing medical problems and proactively getting involved,” says Dr. Gavi.

To co-manage, hospitalists must take ownership of some medical issues under specific conditions (diabetes, anticoagulation, blood pressure), says Dr. Jaffer.

The Benefits

To Latha Sivaprasad, MD, hospitalist at Beth Israel Medical Center in New York City, there are three main advantages of hospitalists’ involvement in perioperative co-management:

- Hospitalists typically perform comprehensive, multisystemic patient evaluations;

- Hospitalists are extremely accessible; and

- Hospitalists are up to date on inpatient medicine.

How up to date?

“Periop isn’t routinely taught in residency,” says Ali Usmani, MD, a hospitalist at the Cleveland Clinic. “In fact, I had little information about perioperative care.”

When he joined the hospitalist group after a three-year residency at Cleveland Clinic, Dr. Usmani did preparatory reading. Later, the hospitalist group gave him a helpful collection of essays.

“I was very nervous because, of course, I had never done this before,” he says. “Surprisingly, I also had not done a general medicine consult service where we see postoperative patients. It was scary to some extent, but I found out that it is easier than I thought because there are guidelines you can follow from the AHA/ACC that are fairly straightforward. It also meant a nice schedule change from being on the floors.”

Although conducting preoperative evaluations with patients was technically outpatient work, it was not like he was seeing patients with such simple illnesses as a cold or a sore throat. Also, he says, there were no new surprises postoperatively because either he or a hospitalist colleague had seen the patient preoperatively.

Dr. Usmani, also a clinical assistant professor of medicine at Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine of Case Western Reserve University, believes patients are happier when seen by hospitalists because they get a standardized, holistic preoperative assessment. And, helping to reduce the number of unnecessary tests ordered by primary care physicians or surgeons makes him feel as though he’s making a valuable contribution.

New Niche

Dr. Sivaprasad, who is also doing a one-year fellowship in quality improvement and patient safety at Beth Israel, has practiced hospital medicine in four hospitals ranging from 500 to 1,000 beds. “The primary reason we are consulted by surgeons is for perioperative cardiac risk assessment,” says Dr. Sivaprasad. “Other reasons include co-managing a patient with comorbidities such as a history of diabetes, hypertension, or renal failure.”

From 2003-2006, Dr. Sivaprasad was one of 14 hospitalists consulted often by surgeons at St. John’s Mercy Hospital in St Louis, a 1,000-bed Level I trauma center. “We were consulted for postoperative co-management, preoperative evaluation, or more urgent cases such as a patient experiencing hypotension, atrial fibrillation, shortness of breath, decreased urine output, or renal failure,” she says.

Dr. Sivaprasad recently attended the Johns Hopkins conference on Perioperative Management. The session made it easier for her to do a systems-based consult.

“All hospitalists differ to the degree of perioperative medicine they feel comfortable with,” she says. “Hospitalists understand perioperative medicine on different levels. They all can do an acceptable consult; but there is a spectrum of how detailed one can be and what service one can provide for the surgeon and the patient.”

Dr. Jaffer finds his work in perioperative care fulfilling and considers it another way hospitalists can increase their influence.

“Often when you manage medical patients in the hospital, it’s you, the medical patient, and the patient’s primary care physician,” Dr. Jaffer says. “But when you start to manage surgical patients, you are really being looked at by your surgical colleagues as an expert in managing medical problems, just as you view them as experts in managing surgical problems. What I realize from this is that I can be a perioperative medicine expert as well.”

Are there any downfalls to co-managing surgical patients?

“Sometimes the surgeons order unnecessary lab tests such as PTTs [partial thromboplastin time] because they are concerned about bleeding and complications,” Dr. Usmani says. “The next day if there is a deranged PTT, we need to figure out whether to suggest postponing the surgery or go ahead with the surgery based on the patients’ past medical/family history. We try to get our surgeons and our colleagues to work together with us in that regard because they don’t want to postpone surgery either.”

Drs. Usmani, Gavi, Jaffer, and Sivaprasad all say that when surgeons can observe firsthand their hospitalist partners exhibiting expertise in acute care it appears to improve surgeons’ attitudes about the role and value of hospitalists.

In fact, says Dr. Usmani, surgeons call him or one of his colleagues to thank them. “They say, ‘We really appreciate what you’ve done for this patient,’ ’’ he says. “Even if we suggest canceling surgery, they respect that we have seen a potential problem instead of letting it go ahead. They are happy to receive this advice.”

Another new relationship is between anesthesiologists and hospitalists. “I spend a lot of time calling anesthesiologists in regard to patient cases, and a good many of them are surprised to get a call from a hospitalist,” Dr. Gavi says. “We especially work closely together when we get complicated patients ready for surgery.”

A recent encounter proved to Dr. Gavi the complementary nature of the hospitalist-anesthesiologist relationship.2

“A patient came to the hospital two weeks ago to have an elective total knee replacement,” says Dr. Gavi. “She was an older woman with severe pulmonary disease. When the anesthesiologists saw her in the preoperative waiting area and realized how sick she is, they wanted to cancel the surgery. But the surgeon told the anesthesiologist that this patient had been seen in our own preoperative clinic and cleared by a hospitalist.”

Dr. Gavi had done what is customary for an internist. He took a more in-depth look at her pulmonology and cardiac records, called her cardiologist for further history, and reassured the anesthesiologist and surgeon. The patient had her surgery.

The Future

“Perioperative co-management is becoming more of a visible need,” says Dr. Sivaprasad. “It bridges the gap between surgeons and internists.”

To those of his hospitalist colleagues who have little information and are a bit afraid to begin perioperative care practice, Dr. Usmani recommends attending a perioperative summit conference.

The session should teach how to set up a perioperative center and what to do when managing patients with certain conditions.

“Although you meet with patients preoperatively in an office setting, you don’t feel like a primary care physician,” Dr. Usmani says. “You feel as if you are a specialist. You are respected, and you are contributing to postoperative outcomes to the benefit of the patient.”

Perioperative patient management is also financially rewarding because reimbursement is higher than customary hospital medicine duties.

Dr. Jaffer, soon to be chief of the division of hospital medicine at the University of Miami Medical Center in Florida, is proud of the work he and his colleagues have done to grow the Cleveland Clinic perioperative summit. This third summit, in September, was organized in collaboration with the Society of Perioperative Assessment and Quality Improvement.

“I think this is something that every hospitalist should try,” Dr. Usmani says. “It is definitely a niche.” TH

Andrea Sattinger is a frequent contributor to The Hospitalist.

References

- Mangano DT. Perioperative medicine: NHLBI working group deliberations and recommendations. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2004;18(1):1-6.

- Adebola O, Adesanya AO, Joshi GP. Hospitalists and anesthesiologists as perioperative physicians: Are their roles complementary? Proc. (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 2007 April;20(2):140-142.