User login

Inspired by the ABIM Foundation’s Choosing Wisel y ® campaign, the “Things We Do for No Reason ™” (TWDFNR) series reviews practices that have become common parts of hospital care but may provide little value to our patients. Practices reviewed in the TWDFNR series do not represent clear-cut conclusions or clinical practice standards but are meant as a starting place for research and active discussions among hospitalists and patients. We invite you to be part of that discussion.

CLINICAL SCENARIO

A hospitalist admits a 68-year-old woman for community-acquired pneumonia with a past medical history of hypertension, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and osteoarthritis. Her hospitalist consults physical therapy to maximize mobility; continues her home medications including pantoprazole, hydrochlorothiazide, and acetaminophen; and initiates antimicrobial therapy with ceftriaxone and azithromycin. The hospital admission order set requires administration of subcutaneous unfractionated heparin for venous thromboembolism chemoprophylaxis.

WHY YOU MIGHT THINK UNIVERSAL CHEMOPROPHYLAXIS IS NECESSARY

Venous thromboembolism (VTE), which includes deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE), ranks among the leading preventable causes of morbidity and mortality in hospitalized patients.1 DVTs can rapidly progress to a PE, which account for 5% to 10% of in-hospital deaths.1 The negative sequelae of in-hospital VTE, including prolonged hospital stay, increased healthcare costs, and greater risks associated with pharmacologic treatment, add $9 to $18.2 billion in US healthcare expenditures each year.2 Various risk-assessment models (RAMs) identify medical patients at high risk for developing VTE based on the presence of risk factors including acute heart failure, prior history of VTE, and reduced mobility.3 Since hospitalization may itself increase the risk for VTE, medical patients often receive universal chemoprophylaxis with anticoagulants such as unfractionated heparin (UFH), low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH), or fondaparinux.3 A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) published by Wein et al supports the use of VTE chemoprophylaxis in high-risk patients.4 It showed statistically significant reductions in rates of PE in high-risk hospitalized medical patients with UFH (risk ratio [RR], 0.64; 95% CI, 0.50-0.82) or LMWH chemoprophylaxis (RR, 0.37; 95% CI, 0.21-0.64), compared with controls.

In recognition of the magnitude of the problem, national organizations have emphasized routine chemoprophylaxis for prevention of in-hospital VTE as a top-priority measure for patient safety.5,6 The Joint Commission includes chemoprophylaxis as a quality core metric and failure to adhere to such standards compromises hospital accreditation.5 Since 2008, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services no longer reimburses hospitals for preventable VTE and requires institutions to document the rationale for omitting chemoprophylaxis if not commenced on hospital admission.6

WHY CHEMOPROPHYLAXIS FOR LOW-RISK MEDICAL PATIENTS IS UNNECESSARY

In order to understand why chemoprophylaxis fails to benefit low-risk medical patients, it is necessary to critically examine the benefits identified in trials of high-risk patients. Although RCTs and meta-analysis of chemoprophylaxis have consistently demonstrated a reduction in VTE, prevention of asymptomatic VTE identified on screening with ultrasound or venography accounts for more than 90% of the composite outcome in the three key trials.7-9 Hospitalists do not routinely screen for asymptomatic VTE, and incorporation of these events into composite VTE outcomes inflates the magnitude of benefit gained by chemoprophylaxis. Importantly, the standard of care does not include screening for asymptomatic DVTs, and studies have estimated that only 10% to 15% of asymptomatic DVTs progress to a symptomatic VTE.10

A meta-analysis of trials evaluating unselected general medical patients (ie, not those with specific high-risk conditions such as acute myocardial infarction) did not show a reduction in symptomatic VTE with chemoprophylaxis (odds ratio [OR], 0.59; 95% CI, 0.29-1.23).11 In the meta-analysis by Wein et al, which did include patients with specific high-risk conditions, chemoprophylaxis produced a small absolute risk reduction, resulting in a number needed to treat (NNT) of 345 to prevent one PE.4 This demonstrates that, even in high-risk patients, the magnitude of benefit is small. Population-level data also question the benefit of chemoprophylaxis. Flanders et al stratified 35 Michigan hospitals into high-, moderate-, and low-performance tertiles, with performance based on the rate of chemoprophylaxis use on admission for general medical patients at high-risk for VTE. The authors found no significant difference in the rate of VTE at 90 days among tertiles.12 These findings question the usefulness of universal chemoprophylaxis when applied in a real-world setting.

The high rates of VTE in the absence of chemoprophylaxis reported in historic trials may overestimate the contemporary risk. A 2019 multicenter, observational study examined the rate of hospital-acquired DVT for 1,170 low- and high-risk patients with acute medical illness admitted to the internal medicine ward.13 Of them, 250 (21%) underwent prophylaxis with parenteral anticoagulants (mean Padua Prediction Score, 4.5). The remaining 920 (79%) were not treated with prophylaxis (mean Padua Prediction Score, 2.5). All patients underwent ultrasound at admission and discharge. The average length of stay was 13 days, and just three patients (0.3%) experienced in-hospital DVT, two of whom were receiving chemoprophylaxis. Only one (0.09%) DVT was symptomatic.

It should be emphasized that any evidence favoring chemoprophylaxis comes from studies of patients at high-risk of VTE. No data show benefit for low-risk patients. Therefore, any risk of chemoprophylaxis likely outweighs the benefits in low-risk patients. Importantly, the risks are underappreciated. A 2014 meta-analysis reported an increased risk of major hemorrhage (OR, 1.81; 95% CI, 1.10-2.98; P = .02) in high-risk medically ill patients on chemoprophylaxis.14 This results in a number needed to harm for major bleeding of 336, a value similar to the NNT for benefit reported by Wein et al.4 Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, a potentially limb- and life-threatening complication of UFH or LMWH exposure, has an overall incidence of 0.3% to 0.7% in hospitalized patients on chemoprophylaxis.3 Finally, the most commonly used chemoprophylaxis medications are administered subcutaneously, resulting in injection site pain. Unsurprisingly, hospitalized patients refuse chemoprophylaxis more frequently than any other medication.15

The negative implications of inappropriate chemoprophylaxis extend beyond direct harms to patients. Poor stratification and overuse results in unnecessary healthcare costs. One single-center retrospective review demonstrated that, after integration of chemoprophylaxis into hospital order sets, 76% of patients received unnecessary administration of chemoprophylaxis, resulting in an annualized expenditure of $77,652.16 This does not take into account costs associated with major bleeds.

Unfortunately, the pendulum has shifted from an era of underprescribing chemoprophylaxis to hospitalized medical patients to one of overprescribing. Data published in 2018 suggest that providers overuse chemoprophylaxis in low-risk medical patients at more than double the rate of underusing it in high-risk patients (57% vs 21%).17

Several national societies, including the often cited American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) and American Society of Hematology (ASH), provide guidance on the use of VTE chemoprophylaxis in acutely ill medical inpatients.3,18 The ASH guidelines conditionally recommend VTE chemoprophylaxis rather than no chemoprophylaxis.18 However, the guidelines do not provide guidance on a risk-stratified approach and disclose that this recommendation is supported by a low certainty in the evidence of the net health benefit gained.18 Guidelines from ACCP lean towards individualized care and recommend against the use of VTE chemoprophylaxis for hospitalized acutely ill, low-risk medical patients.3

WHAT YOU SHOULD DO INSTEAD

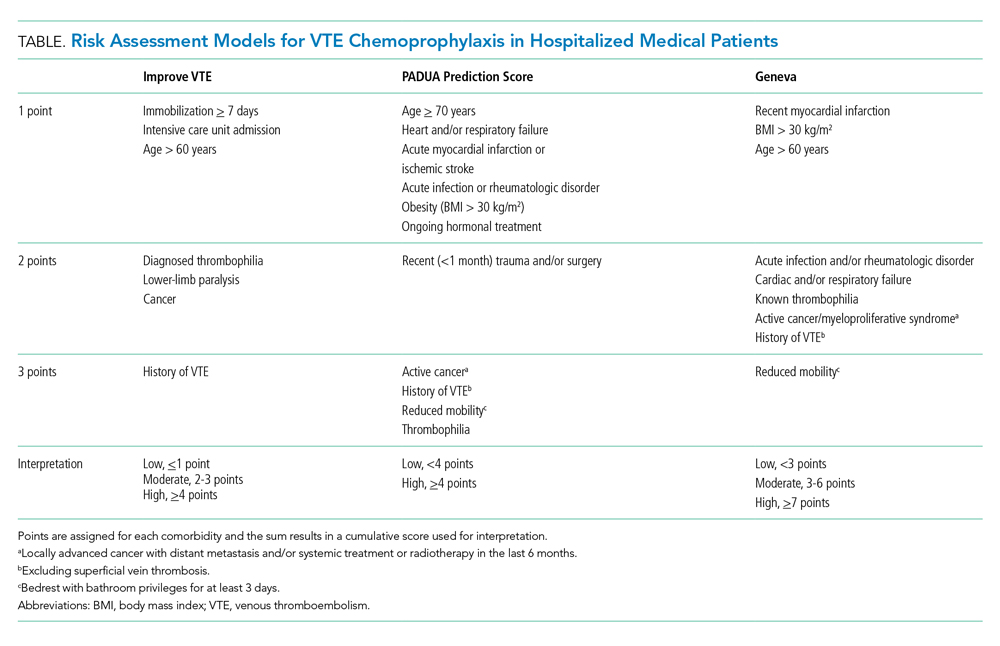

Clinicians should risk stratify using validated RAMs when making a patient-centered treatment plan on admission. The table outlines the most common RAMs with evidence for use in acute medically ill hospitalized patients. Although RAMs have limitations (eg, lack of prospective validation and complexity), the ACCP guidelines advocate for their use.3

Given that immobility independently increases risk for VTE, early mobilization is a simple and cost-effective way to potentially prevent VTE in low-risk patients. In addition to this potential benefit, early mobilization shortens the length of hospital stay, improves functional status and rates of delirium in hospitalized elderly patients, and hastens postoperative recovery after major surgeries.19

RECOMMENDATIONS

- Incorporate a patient-centered, risk-stratified approach to identify low-risk patients. This can be done manually or with use of RAMS embedded in the electronic health record.

- Do not prescribe chemoprophylaxis to low-risk hospitalized medical patients.

- Emphasize the importance of early mobilization in hospitalized patients.

CONCLUSION

In regard to the case, the hospitalist should use a RAM developed for the nonsurgical, non–critically ill patient to determine her need for chemoprophylaxis. Based on the clinical data presented, the three RAMs available would classify the patient as low risk for developing an in-hospital VTE. She should not receive chemoprophylaxis given the lack of data demonstrating benefit in this population. To mitigate the potential risk of bleeding, heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, and painful injections, the hospitalist should discontinue heparin. The hospitalist should advocate for early mobilization and minimize the duration of hospital stay as appropriate.

Do you think this is a low-value practice? Is this truly a “Thing We Do for No Reason™”? Share what you do in your practice and join in the conversation online by retweeting it on Twitter (#TWDFNR) and liking it on Facebook. We invite you to propose ideas for other “Things We Do for No Reason™” topics by emailing TWDFNR@hospitalmedicine.org.

- Francis CW. Clinical practice. prophylaxis for thromboembolism in hospitalized medical patients. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(14):1438-1444. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmcp067264

- Mahan CE, Borrego ME, Woersching AL, et al. Venous thromboembolism: annualised United States models for total, hospital-acquired and preventable costs utilising long-term attack rates. Thromb Haemost. 2012;108(2):291-302. https://doi.org/10.1160/th12-03-0162

- Kahn SR, Lim W, Dunn AS, et al. Prevention of VTE in nonsurgical patients: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 Suppl):e195S-e226S. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.11-2296

- Wein L, Wein S, Haas SJ, Shaw J, Krum H. Pharmacological venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in hospitalized medical patients: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(14):1476-1486. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.167.14.1476

- Performance Measurement. The Joint Commission. Updated October 26, 2020. Accessed November 8, 2019. http://www.jointcommission.org/PerformanceMeasurement/PerformanceMeasurement/VTE.htm

- Venous Thromboembolism Prophylaxis. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Updated May 6, 2020. Accessed November 8, 2019. https://ecqi.healthit.gov/ecqm/eh/2019/cms108v7

- Cohen AT, Davidson BL, Gallus AS, et al. Efficacy and safety of fondaparinux for the prevention of venous thromboembolism in older acute medical patients: randomised placebo controlled trial. BMJ. 2006;332(7537):325-329. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.38733.466748.7c

- Leizorovicz A, Cohen AT, Turpie AG, et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of dalteparin for the prevention of venous thromboembolism in acutely ill medical patients. Circulation. 2004;110(7):874-879. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.cir.0000138928.83266.24

- Samama MM, Cohen AT, Darmon JY, et. al. A comparison of enoxaparin with placebo for the prevention of venous thromboembolism in acutely ill medical patients. prophylaxis in medical patients with enoxaparin study group. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(11):793-800. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejm199909093411103

- Segers AE, Prins MH, Lensing AW, Buller HR. Is contrast venography a valid surrogate outcome measure in venous thromboembolism prevention studies? J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3(5):1099-1102. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01317.x

- Vardi M, Steinberg M, Haran M, Cohen S. Benefits versus risks of pharmacological prophylaxis to prevent symptomatic venous thromboembolism in unselected medical patients revisited. Meta-analysis of the medical literature. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2012;34(1):11-19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11239-012-0730-x

- Flanders SA, Greene MT, Grant P, et al. Hospital performance for pharmacologic venous thromboembolism prophylaxis and rate of venous thromboembolism: a cohort study. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(10):1577-1584. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.3384

- Loffredo L, Arienti V, Vidili G, et al. Low rate of intrahospital deep venous thrombosis in acutely ill medical patients: results from the AURELIO study. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019;94(1):37-43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2018.07.020

- Alikhan R, Bedenis R, Cohen AT. Heparin for the prevention of venous thromboembolism in acutely ill medical patients (excluding stroke and myocardial infarction). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2014(5):CD003747. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd003747.pub4

- Popoola VO, Lau BD, Tan E, et al. Nonadministration of medication doses for venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in a cohort of hospitalized patients. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2018;75(6):392-397. https://doi.org/10.2146/ajhp161057

- Chaudhary R, Damluji A, Batukbhai B, et al. Venous Thromboembolism prophylaxis: inadequate and overprophylaxis when comparing perceived versus calculated risk. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2017;1(3):242-247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2017.10.003

- Grant PJ, Conlon A, Chopra V, Flanders SA. Use of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in hospitalized patients. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(8):1122-1124. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.2022

- Schünemann HJ, Cushman M, Burnett AE, et al. American Society of Hematology 2018 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: prophylaxis for hospitalized and nonhospitalized medical patients. Blood Adv. 2018;2(22):3198-3225. https://doi.org/10.1182/bloodadvances.2018022954

- Pashikanti L, Von Ah D. Impact of early mobilization protocol on the medical-surgical inpatient population: an integrated review of literature. Clin Nurse Spec. 2012;26(2):87-94. https://doi.org/10.1097/nur.0b013e31824590e6

Inspired by the ABIM Foundation’s Choosing Wisel y ® campaign, the “Things We Do for No Reason ™” (TWDFNR) series reviews practices that have become common parts of hospital care but may provide little value to our patients. Practices reviewed in the TWDFNR series do not represent clear-cut conclusions or clinical practice standards but are meant as a starting place for research and active discussions among hospitalists and patients. We invite you to be part of that discussion.

CLINICAL SCENARIO

A hospitalist admits a 68-year-old woman for community-acquired pneumonia with a past medical history of hypertension, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and osteoarthritis. Her hospitalist consults physical therapy to maximize mobility; continues her home medications including pantoprazole, hydrochlorothiazide, and acetaminophen; and initiates antimicrobial therapy with ceftriaxone and azithromycin. The hospital admission order set requires administration of subcutaneous unfractionated heparin for venous thromboembolism chemoprophylaxis.

WHY YOU MIGHT THINK UNIVERSAL CHEMOPROPHYLAXIS IS NECESSARY

Venous thromboembolism (VTE), which includes deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE), ranks among the leading preventable causes of morbidity and mortality in hospitalized patients.1 DVTs can rapidly progress to a PE, which account for 5% to 10% of in-hospital deaths.1 The negative sequelae of in-hospital VTE, including prolonged hospital stay, increased healthcare costs, and greater risks associated with pharmacologic treatment, add $9 to $18.2 billion in US healthcare expenditures each year.2 Various risk-assessment models (RAMs) identify medical patients at high risk for developing VTE based on the presence of risk factors including acute heart failure, prior history of VTE, and reduced mobility.3 Since hospitalization may itself increase the risk for VTE, medical patients often receive universal chemoprophylaxis with anticoagulants such as unfractionated heparin (UFH), low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH), or fondaparinux.3 A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) published by Wein et al supports the use of VTE chemoprophylaxis in high-risk patients.4 It showed statistically significant reductions in rates of PE in high-risk hospitalized medical patients with UFH (risk ratio [RR], 0.64; 95% CI, 0.50-0.82) or LMWH chemoprophylaxis (RR, 0.37; 95% CI, 0.21-0.64), compared with controls.

In recognition of the magnitude of the problem, national organizations have emphasized routine chemoprophylaxis for prevention of in-hospital VTE as a top-priority measure for patient safety.5,6 The Joint Commission includes chemoprophylaxis as a quality core metric and failure to adhere to such standards compromises hospital accreditation.5 Since 2008, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services no longer reimburses hospitals for preventable VTE and requires institutions to document the rationale for omitting chemoprophylaxis if not commenced on hospital admission.6

WHY CHEMOPROPHYLAXIS FOR LOW-RISK MEDICAL PATIENTS IS UNNECESSARY

In order to understand why chemoprophylaxis fails to benefit low-risk medical patients, it is necessary to critically examine the benefits identified in trials of high-risk patients. Although RCTs and meta-analysis of chemoprophylaxis have consistently demonstrated a reduction in VTE, prevention of asymptomatic VTE identified on screening with ultrasound or venography accounts for more than 90% of the composite outcome in the three key trials.7-9 Hospitalists do not routinely screen for asymptomatic VTE, and incorporation of these events into composite VTE outcomes inflates the magnitude of benefit gained by chemoprophylaxis. Importantly, the standard of care does not include screening for asymptomatic DVTs, and studies have estimated that only 10% to 15% of asymptomatic DVTs progress to a symptomatic VTE.10

A meta-analysis of trials evaluating unselected general medical patients (ie, not those with specific high-risk conditions such as acute myocardial infarction) did not show a reduction in symptomatic VTE with chemoprophylaxis (odds ratio [OR], 0.59; 95% CI, 0.29-1.23).11 In the meta-analysis by Wein et al, which did include patients with specific high-risk conditions, chemoprophylaxis produced a small absolute risk reduction, resulting in a number needed to treat (NNT) of 345 to prevent one PE.4 This demonstrates that, even in high-risk patients, the magnitude of benefit is small. Population-level data also question the benefit of chemoprophylaxis. Flanders et al stratified 35 Michigan hospitals into high-, moderate-, and low-performance tertiles, with performance based on the rate of chemoprophylaxis use on admission for general medical patients at high-risk for VTE. The authors found no significant difference in the rate of VTE at 90 days among tertiles.12 These findings question the usefulness of universal chemoprophylaxis when applied in a real-world setting.

The high rates of VTE in the absence of chemoprophylaxis reported in historic trials may overestimate the contemporary risk. A 2019 multicenter, observational study examined the rate of hospital-acquired DVT for 1,170 low- and high-risk patients with acute medical illness admitted to the internal medicine ward.13 Of them, 250 (21%) underwent prophylaxis with parenteral anticoagulants (mean Padua Prediction Score, 4.5). The remaining 920 (79%) were not treated with prophylaxis (mean Padua Prediction Score, 2.5). All patients underwent ultrasound at admission and discharge. The average length of stay was 13 days, and just three patients (0.3%) experienced in-hospital DVT, two of whom were receiving chemoprophylaxis. Only one (0.09%) DVT was symptomatic.

It should be emphasized that any evidence favoring chemoprophylaxis comes from studies of patients at high-risk of VTE. No data show benefit for low-risk patients. Therefore, any risk of chemoprophylaxis likely outweighs the benefits in low-risk patients. Importantly, the risks are underappreciated. A 2014 meta-analysis reported an increased risk of major hemorrhage (OR, 1.81; 95% CI, 1.10-2.98; P = .02) in high-risk medically ill patients on chemoprophylaxis.14 This results in a number needed to harm for major bleeding of 336, a value similar to the NNT for benefit reported by Wein et al.4 Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, a potentially limb- and life-threatening complication of UFH or LMWH exposure, has an overall incidence of 0.3% to 0.7% in hospitalized patients on chemoprophylaxis.3 Finally, the most commonly used chemoprophylaxis medications are administered subcutaneously, resulting in injection site pain. Unsurprisingly, hospitalized patients refuse chemoprophylaxis more frequently than any other medication.15

The negative implications of inappropriate chemoprophylaxis extend beyond direct harms to patients. Poor stratification and overuse results in unnecessary healthcare costs. One single-center retrospective review demonstrated that, after integration of chemoprophylaxis into hospital order sets, 76% of patients received unnecessary administration of chemoprophylaxis, resulting in an annualized expenditure of $77,652.16 This does not take into account costs associated with major bleeds.

Unfortunately, the pendulum has shifted from an era of underprescribing chemoprophylaxis to hospitalized medical patients to one of overprescribing. Data published in 2018 suggest that providers overuse chemoprophylaxis in low-risk medical patients at more than double the rate of underusing it in high-risk patients (57% vs 21%).17

Several national societies, including the often cited American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) and American Society of Hematology (ASH), provide guidance on the use of VTE chemoprophylaxis in acutely ill medical inpatients.3,18 The ASH guidelines conditionally recommend VTE chemoprophylaxis rather than no chemoprophylaxis.18 However, the guidelines do not provide guidance on a risk-stratified approach and disclose that this recommendation is supported by a low certainty in the evidence of the net health benefit gained.18 Guidelines from ACCP lean towards individualized care and recommend against the use of VTE chemoprophylaxis for hospitalized acutely ill, low-risk medical patients.3

WHAT YOU SHOULD DO INSTEAD

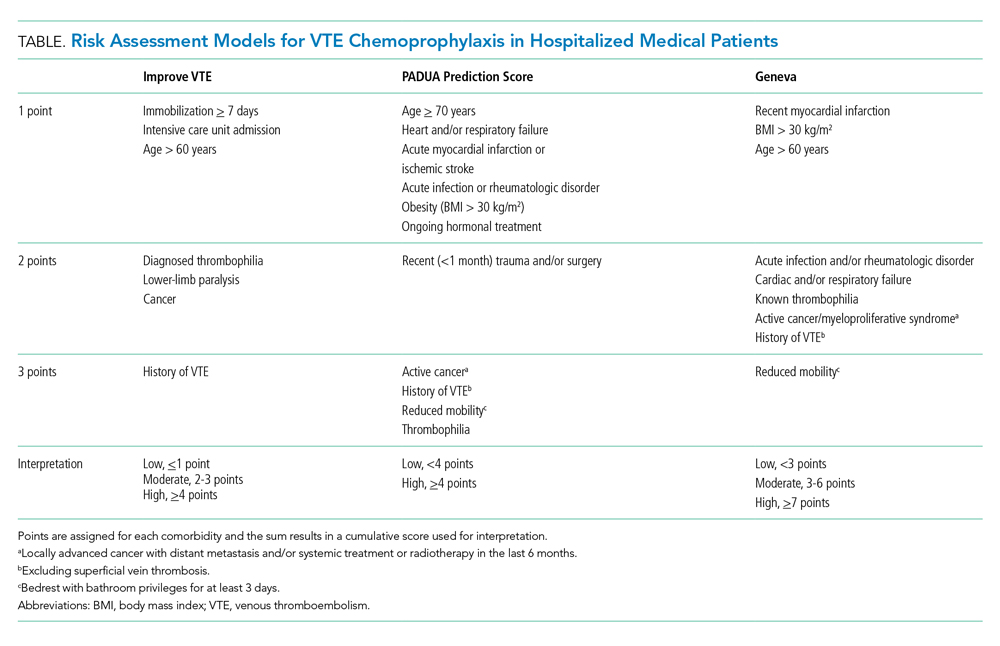

Clinicians should risk stratify using validated RAMs when making a patient-centered treatment plan on admission. The table outlines the most common RAMs with evidence for use in acute medically ill hospitalized patients. Although RAMs have limitations (eg, lack of prospective validation and complexity), the ACCP guidelines advocate for their use.3

Given that immobility independently increases risk for VTE, early mobilization is a simple and cost-effective way to potentially prevent VTE in low-risk patients. In addition to this potential benefit, early mobilization shortens the length of hospital stay, improves functional status and rates of delirium in hospitalized elderly patients, and hastens postoperative recovery after major surgeries.19

RECOMMENDATIONS

- Incorporate a patient-centered, risk-stratified approach to identify low-risk patients. This can be done manually or with use of RAMS embedded in the electronic health record.

- Do not prescribe chemoprophylaxis to low-risk hospitalized medical patients.

- Emphasize the importance of early mobilization in hospitalized patients.

CONCLUSION

In regard to the case, the hospitalist should use a RAM developed for the nonsurgical, non–critically ill patient to determine her need for chemoprophylaxis. Based on the clinical data presented, the three RAMs available would classify the patient as low risk for developing an in-hospital VTE. She should not receive chemoprophylaxis given the lack of data demonstrating benefit in this population. To mitigate the potential risk of bleeding, heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, and painful injections, the hospitalist should discontinue heparin. The hospitalist should advocate for early mobilization and minimize the duration of hospital stay as appropriate.

Do you think this is a low-value practice? Is this truly a “Thing We Do for No Reason™”? Share what you do in your practice and join in the conversation online by retweeting it on Twitter (#TWDFNR) and liking it on Facebook. We invite you to propose ideas for other “Things We Do for No Reason™” topics by emailing TWDFNR@hospitalmedicine.org.

Inspired by the ABIM Foundation’s Choosing Wisel y ® campaign, the “Things We Do for No Reason ™” (TWDFNR) series reviews practices that have become common parts of hospital care but may provide little value to our patients. Practices reviewed in the TWDFNR series do not represent clear-cut conclusions or clinical practice standards but are meant as a starting place for research and active discussions among hospitalists and patients. We invite you to be part of that discussion.

CLINICAL SCENARIO

A hospitalist admits a 68-year-old woman for community-acquired pneumonia with a past medical history of hypertension, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and osteoarthritis. Her hospitalist consults physical therapy to maximize mobility; continues her home medications including pantoprazole, hydrochlorothiazide, and acetaminophen; and initiates antimicrobial therapy with ceftriaxone and azithromycin. The hospital admission order set requires administration of subcutaneous unfractionated heparin for venous thromboembolism chemoprophylaxis.

WHY YOU MIGHT THINK UNIVERSAL CHEMOPROPHYLAXIS IS NECESSARY

Venous thromboembolism (VTE), which includes deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE), ranks among the leading preventable causes of morbidity and mortality in hospitalized patients.1 DVTs can rapidly progress to a PE, which account for 5% to 10% of in-hospital deaths.1 The negative sequelae of in-hospital VTE, including prolonged hospital stay, increased healthcare costs, and greater risks associated with pharmacologic treatment, add $9 to $18.2 billion in US healthcare expenditures each year.2 Various risk-assessment models (RAMs) identify medical patients at high risk for developing VTE based on the presence of risk factors including acute heart failure, prior history of VTE, and reduced mobility.3 Since hospitalization may itself increase the risk for VTE, medical patients often receive universal chemoprophylaxis with anticoagulants such as unfractionated heparin (UFH), low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH), or fondaparinux.3 A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) published by Wein et al supports the use of VTE chemoprophylaxis in high-risk patients.4 It showed statistically significant reductions in rates of PE in high-risk hospitalized medical patients with UFH (risk ratio [RR], 0.64; 95% CI, 0.50-0.82) or LMWH chemoprophylaxis (RR, 0.37; 95% CI, 0.21-0.64), compared with controls.

In recognition of the magnitude of the problem, national organizations have emphasized routine chemoprophylaxis for prevention of in-hospital VTE as a top-priority measure for patient safety.5,6 The Joint Commission includes chemoprophylaxis as a quality core metric and failure to adhere to such standards compromises hospital accreditation.5 Since 2008, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services no longer reimburses hospitals for preventable VTE and requires institutions to document the rationale for omitting chemoprophylaxis if not commenced on hospital admission.6

WHY CHEMOPROPHYLAXIS FOR LOW-RISK MEDICAL PATIENTS IS UNNECESSARY

In order to understand why chemoprophylaxis fails to benefit low-risk medical patients, it is necessary to critically examine the benefits identified in trials of high-risk patients. Although RCTs and meta-analysis of chemoprophylaxis have consistently demonstrated a reduction in VTE, prevention of asymptomatic VTE identified on screening with ultrasound or venography accounts for more than 90% of the composite outcome in the three key trials.7-9 Hospitalists do not routinely screen for asymptomatic VTE, and incorporation of these events into composite VTE outcomes inflates the magnitude of benefit gained by chemoprophylaxis. Importantly, the standard of care does not include screening for asymptomatic DVTs, and studies have estimated that only 10% to 15% of asymptomatic DVTs progress to a symptomatic VTE.10

A meta-analysis of trials evaluating unselected general medical patients (ie, not those with specific high-risk conditions such as acute myocardial infarction) did not show a reduction in symptomatic VTE with chemoprophylaxis (odds ratio [OR], 0.59; 95% CI, 0.29-1.23).11 In the meta-analysis by Wein et al, which did include patients with specific high-risk conditions, chemoprophylaxis produced a small absolute risk reduction, resulting in a number needed to treat (NNT) of 345 to prevent one PE.4 This demonstrates that, even in high-risk patients, the magnitude of benefit is small. Population-level data also question the benefit of chemoprophylaxis. Flanders et al stratified 35 Michigan hospitals into high-, moderate-, and low-performance tertiles, with performance based on the rate of chemoprophylaxis use on admission for general medical patients at high-risk for VTE. The authors found no significant difference in the rate of VTE at 90 days among tertiles.12 These findings question the usefulness of universal chemoprophylaxis when applied in a real-world setting.

The high rates of VTE in the absence of chemoprophylaxis reported in historic trials may overestimate the contemporary risk. A 2019 multicenter, observational study examined the rate of hospital-acquired DVT for 1,170 low- and high-risk patients with acute medical illness admitted to the internal medicine ward.13 Of them, 250 (21%) underwent prophylaxis with parenteral anticoagulants (mean Padua Prediction Score, 4.5). The remaining 920 (79%) were not treated with prophylaxis (mean Padua Prediction Score, 2.5). All patients underwent ultrasound at admission and discharge. The average length of stay was 13 days, and just three patients (0.3%) experienced in-hospital DVT, two of whom were receiving chemoprophylaxis. Only one (0.09%) DVT was symptomatic.

It should be emphasized that any evidence favoring chemoprophylaxis comes from studies of patients at high-risk of VTE. No data show benefit for low-risk patients. Therefore, any risk of chemoprophylaxis likely outweighs the benefits in low-risk patients. Importantly, the risks are underappreciated. A 2014 meta-analysis reported an increased risk of major hemorrhage (OR, 1.81; 95% CI, 1.10-2.98; P = .02) in high-risk medically ill patients on chemoprophylaxis.14 This results in a number needed to harm for major bleeding of 336, a value similar to the NNT for benefit reported by Wein et al.4 Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, a potentially limb- and life-threatening complication of UFH or LMWH exposure, has an overall incidence of 0.3% to 0.7% in hospitalized patients on chemoprophylaxis.3 Finally, the most commonly used chemoprophylaxis medications are administered subcutaneously, resulting in injection site pain. Unsurprisingly, hospitalized patients refuse chemoprophylaxis more frequently than any other medication.15

The negative implications of inappropriate chemoprophylaxis extend beyond direct harms to patients. Poor stratification and overuse results in unnecessary healthcare costs. One single-center retrospective review demonstrated that, after integration of chemoprophylaxis into hospital order sets, 76% of patients received unnecessary administration of chemoprophylaxis, resulting in an annualized expenditure of $77,652.16 This does not take into account costs associated with major bleeds.

Unfortunately, the pendulum has shifted from an era of underprescribing chemoprophylaxis to hospitalized medical patients to one of overprescribing. Data published in 2018 suggest that providers overuse chemoprophylaxis in low-risk medical patients at more than double the rate of underusing it in high-risk patients (57% vs 21%).17

Several national societies, including the often cited American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) and American Society of Hematology (ASH), provide guidance on the use of VTE chemoprophylaxis in acutely ill medical inpatients.3,18 The ASH guidelines conditionally recommend VTE chemoprophylaxis rather than no chemoprophylaxis.18 However, the guidelines do not provide guidance on a risk-stratified approach and disclose that this recommendation is supported by a low certainty in the evidence of the net health benefit gained.18 Guidelines from ACCP lean towards individualized care and recommend against the use of VTE chemoprophylaxis for hospitalized acutely ill, low-risk medical patients.3

WHAT YOU SHOULD DO INSTEAD

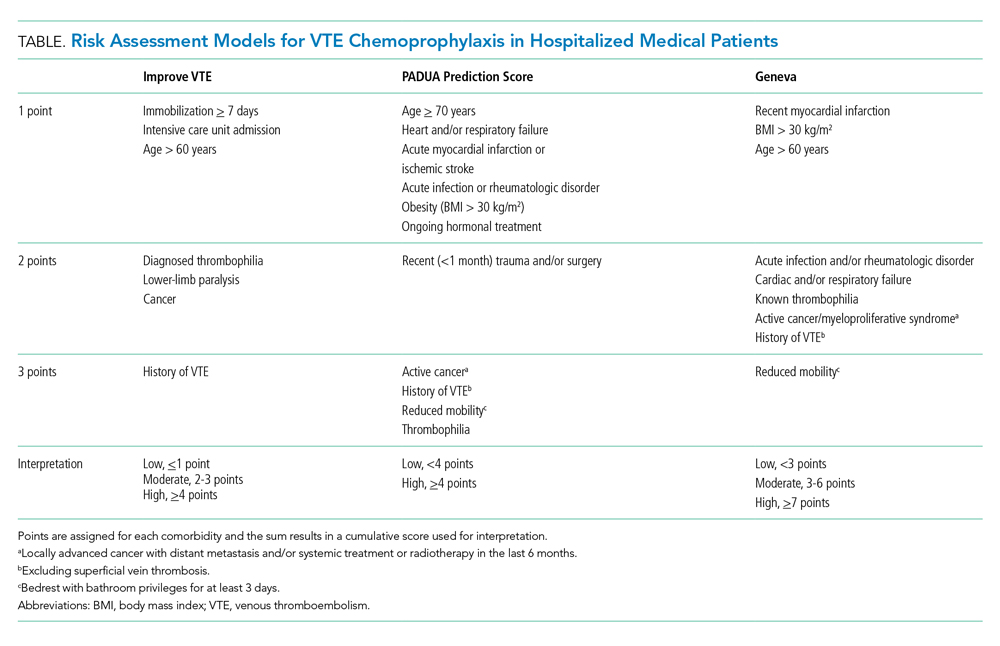

Clinicians should risk stratify using validated RAMs when making a patient-centered treatment plan on admission. The table outlines the most common RAMs with evidence for use in acute medically ill hospitalized patients. Although RAMs have limitations (eg, lack of prospective validation and complexity), the ACCP guidelines advocate for their use.3

Given that immobility independently increases risk for VTE, early mobilization is a simple and cost-effective way to potentially prevent VTE in low-risk patients. In addition to this potential benefit, early mobilization shortens the length of hospital stay, improves functional status and rates of delirium in hospitalized elderly patients, and hastens postoperative recovery after major surgeries.19

RECOMMENDATIONS

- Incorporate a patient-centered, risk-stratified approach to identify low-risk patients. This can be done manually or with use of RAMS embedded in the electronic health record.

- Do not prescribe chemoprophylaxis to low-risk hospitalized medical patients.

- Emphasize the importance of early mobilization in hospitalized patients.

CONCLUSION

In regard to the case, the hospitalist should use a RAM developed for the nonsurgical, non–critically ill patient to determine her need for chemoprophylaxis. Based on the clinical data presented, the three RAMs available would classify the patient as low risk for developing an in-hospital VTE. She should not receive chemoprophylaxis given the lack of data demonstrating benefit in this population. To mitigate the potential risk of bleeding, heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, and painful injections, the hospitalist should discontinue heparin. The hospitalist should advocate for early mobilization and minimize the duration of hospital stay as appropriate.

Do you think this is a low-value practice? Is this truly a “Thing We Do for No Reason™”? Share what you do in your practice and join in the conversation online by retweeting it on Twitter (#TWDFNR) and liking it on Facebook. We invite you to propose ideas for other “Things We Do for No Reason™” topics by emailing TWDFNR@hospitalmedicine.org.

- Francis CW. Clinical practice. prophylaxis for thromboembolism in hospitalized medical patients. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(14):1438-1444. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmcp067264

- Mahan CE, Borrego ME, Woersching AL, et al. Venous thromboembolism: annualised United States models for total, hospital-acquired and preventable costs utilising long-term attack rates. Thromb Haemost. 2012;108(2):291-302. https://doi.org/10.1160/th12-03-0162

- Kahn SR, Lim W, Dunn AS, et al. Prevention of VTE in nonsurgical patients: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 Suppl):e195S-e226S. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.11-2296

- Wein L, Wein S, Haas SJ, Shaw J, Krum H. Pharmacological venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in hospitalized medical patients: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(14):1476-1486. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.167.14.1476

- Performance Measurement. The Joint Commission. Updated October 26, 2020. Accessed November 8, 2019. http://www.jointcommission.org/PerformanceMeasurement/PerformanceMeasurement/VTE.htm

- Venous Thromboembolism Prophylaxis. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Updated May 6, 2020. Accessed November 8, 2019. https://ecqi.healthit.gov/ecqm/eh/2019/cms108v7

- Cohen AT, Davidson BL, Gallus AS, et al. Efficacy and safety of fondaparinux for the prevention of venous thromboembolism in older acute medical patients: randomised placebo controlled trial. BMJ. 2006;332(7537):325-329. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.38733.466748.7c

- Leizorovicz A, Cohen AT, Turpie AG, et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of dalteparin for the prevention of venous thromboembolism in acutely ill medical patients. Circulation. 2004;110(7):874-879. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.cir.0000138928.83266.24

- Samama MM, Cohen AT, Darmon JY, et. al. A comparison of enoxaparin with placebo for the prevention of venous thromboembolism in acutely ill medical patients. prophylaxis in medical patients with enoxaparin study group. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(11):793-800. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejm199909093411103

- Segers AE, Prins MH, Lensing AW, Buller HR. Is contrast venography a valid surrogate outcome measure in venous thromboembolism prevention studies? J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3(5):1099-1102. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01317.x

- Vardi M, Steinberg M, Haran M, Cohen S. Benefits versus risks of pharmacological prophylaxis to prevent symptomatic venous thromboembolism in unselected medical patients revisited. Meta-analysis of the medical literature. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2012;34(1):11-19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11239-012-0730-x

- Flanders SA, Greene MT, Grant P, et al. Hospital performance for pharmacologic venous thromboembolism prophylaxis and rate of venous thromboembolism: a cohort study. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(10):1577-1584. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.3384

- Loffredo L, Arienti V, Vidili G, et al. Low rate of intrahospital deep venous thrombosis in acutely ill medical patients: results from the AURELIO study. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019;94(1):37-43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2018.07.020

- Alikhan R, Bedenis R, Cohen AT. Heparin for the prevention of venous thromboembolism in acutely ill medical patients (excluding stroke and myocardial infarction). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2014(5):CD003747. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd003747.pub4

- Popoola VO, Lau BD, Tan E, et al. Nonadministration of medication doses for venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in a cohort of hospitalized patients. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2018;75(6):392-397. https://doi.org/10.2146/ajhp161057

- Chaudhary R, Damluji A, Batukbhai B, et al. Venous Thromboembolism prophylaxis: inadequate and overprophylaxis when comparing perceived versus calculated risk. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2017;1(3):242-247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2017.10.003

- Grant PJ, Conlon A, Chopra V, Flanders SA. Use of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in hospitalized patients. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(8):1122-1124. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.2022

- Schünemann HJ, Cushman M, Burnett AE, et al. American Society of Hematology 2018 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: prophylaxis for hospitalized and nonhospitalized medical patients. Blood Adv. 2018;2(22):3198-3225. https://doi.org/10.1182/bloodadvances.2018022954

- Pashikanti L, Von Ah D. Impact of early mobilization protocol on the medical-surgical inpatient population: an integrated review of literature. Clin Nurse Spec. 2012;26(2):87-94. https://doi.org/10.1097/nur.0b013e31824590e6

- Francis CW. Clinical practice. prophylaxis for thromboembolism in hospitalized medical patients. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(14):1438-1444. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmcp067264

- Mahan CE, Borrego ME, Woersching AL, et al. Venous thromboembolism: annualised United States models for total, hospital-acquired and preventable costs utilising long-term attack rates. Thromb Haemost. 2012;108(2):291-302. https://doi.org/10.1160/th12-03-0162

- Kahn SR, Lim W, Dunn AS, et al. Prevention of VTE in nonsurgical patients: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 Suppl):e195S-e226S. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.11-2296

- Wein L, Wein S, Haas SJ, Shaw J, Krum H. Pharmacological venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in hospitalized medical patients: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(14):1476-1486. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.167.14.1476

- Performance Measurement. The Joint Commission. Updated October 26, 2020. Accessed November 8, 2019. http://www.jointcommission.org/PerformanceMeasurement/PerformanceMeasurement/VTE.htm

- Venous Thromboembolism Prophylaxis. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Updated May 6, 2020. Accessed November 8, 2019. https://ecqi.healthit.gov/ecqm/eh/2019/cms108v7

- Cohen AT, Davidson BL, Gallus AS, et al. Efficacy and safety of fondaparinux for the prevention of venous thromboembolism in older acute medical patients: randomised placebo controlled trial. BMJ. 2006;332(7537):325-329. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.38733.466748.7c

- Leizorovicz A, Cohen AT, Turpie AG, et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of dalteparin for the prevention of venous thromboembolism in acutely ill medical patients. Circulation. 2004;110(7):874-879. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.cir.0000138928.83266.24

- Samama MM, Cohen AT, Darmon JY, et. al. A comparison of enoxaparin with placebo for the prevention of venous thromboembolism in acutely ill medical patients. prophylaxis in medical patients with enoxaparin study group. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(11):793-800. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejm199909093411103

- Segers AE, Prins MH, Lensing AW, Buller HR. Is contrast venography a valid surrogate outcome measure in venous thromboembolism prevention studies? J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3(5):1099-1102. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01317.x

- Vardi M, Steinberg M, Haran M, Cohen S. Benefits versus risks of pharmacological prophylaxis to prevent symptomatic venous thromboembolism in unselected medical patients revisited. Meta-analysis of the medical literature. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2012;34(1):11-19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11239-012-0730-x

- Flanders SA, Greene MT, Grant P, et al. Hospital performance for pharmacologic venous thromboembolism prophylaxis and rate of venous thromboembolism: a cohort study. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(10):1577-1584. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.3384

- Loffredo L, Arienti V, Vidili G, et al. Low rate of intrahospital deep venous thrombosis in acutely ill medical patients: results from the AURELIO study. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019;94(1):37-43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2018.07.020

- Alikhan R, Bedenis R, Cohen AT. Heparin for the prevention of venous thromboembolism in acutely ill medical patients (excluding stroke and myocardial infarction). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2014(5):CD003747. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd003747.pub4

- Popoola VO, Lau BD, Tan E, et al. Nonadministration of medication doses for venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in a cohort of hospitalized patients. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2018;75(6):392-397. https://doi.org/10.2146/ajhp161057

- Chaudhary R, Damluji A, Batukbhai B, et al. Venous Thromboembolism prophylaxis: inadequate and overprophylaxis when comparing perceived versus calculated risk. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2017;1(3):242-247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2017.10.003

- Grant PJ, Conlon A, Chopra V, Flanders SA. Use of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in hospitalized patients. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(8):1122-1124. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.2022

- Schünemann HJ, Cushman M, Burnett AE, et al. American Society of Hematology 2018 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: prophylaxis for hospitalized and nonhospitalized medical patients. Blood Adv. 2018;2(22):3198-3225. https://doi.org/10.1182/bloodadvances.2018022954

- Pashikanti L, Von Ah D. Impact of early mobilization protocol on the medical-surgical inpatient population: an integrated review of literature. Clin Nurse Spec. 2012;26(2):87-94. https://doi.org/10.1097/nur.0b013e31824590e6

© 2020 Society of Hospital Medicine

Email: blba249@uky.edu; Telephone: 267-627-4207; Twitter @theABofPharmaC.