User login

Less-frequent cytologic testing, followed by hrHPV tests

George F. Sawaya, MD, from the University of California, San Francisco, and colleagues enrolled 451 English-speaking or Spanish-speaking women aged 21-65 years from women’s health clinics between September 2014 and June 2016. The women were mean 38 years old, and 57% were nonwhite women. The researchers examined utilities for 23 different health states associated with cervical cancer, and created a Markov decision model of type-specific high-risk human papillomavirus (hrHPV)–induced cervical carcinogenesis.

The researchers evaluated 12 screening strategies, which included the following scenarios:

- For women aged 21-65 years, cytologic testing every 3 years; if atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASCUS) are found, repeat cytologic testing in 1 year or switch to immediate hrHPV triage.

- For women 21-29 years, cytologic testing every 3 years, and then followed with cytologic testing plus hrHPV testing (cotesting) for women 30-65 years old; if a normal cytologic test result and positive hrHPV test results, move to cotesting in 1 year or immediate genotyping triage.

- For women 21-29 years, cytologic testing every 3 years, and then followed with hrHPV testing alone every 3-5 years for women 30-65 years; if there are positive hrHPV results, move to immediate cytologic testing triage or immediate genotyping triage. Women with positive hrHPV and negative genotyping results receive additional cytologic testing triage.

In the strategies that switched the women from cytologic testing to hrHPV tests, the study also tested doing the switch at age 25 years rather than 30 years, the investigators reported.

Overall, with regard to cost, screening resulted in more cost savings ($1,267-$2,577) than not screening ($2,891 per woman). Women received the most benefit as measured by lifetime quality-adjusted life-years (QALY) if they received cytologic test every 3 years and received repeat testing for ASCUS. The strategy with the lowest cost was cytologic testing every 3 years and hrHPV triage for ASCUS ($1,267), and the strategy of 3-year cytology testing with repeat testing for ASCUS had more QALY but at a higher cost ($2,166). Other higher-cost strategies relative to QALYs included cotesting and primary hrHPV and also annual cytologic testing ($2,577).

“Both the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the American Cancer Society consider cotesting the preferred cervical cancer screening strategy, and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force considers it an alternative strategy,” Dr. Sawaya and colleagues noted. “Our findings challenge these endorsements.”

“Our analyses suggest that it is not cost effective to begin primary hrHPV testing prior to age 30 years, to perform hrHPV testing every 3 years, or to perform cytologic testing annually. Comparative modeling is needed to confirm these findings,” they concluded.

Dual stain vs. cytologic testing alone

In a second study, Nicolas Wentzensen, MD, PhD, from the National Cancer Institute and colleagues performed a prospective observational study of 3,225 women who tested positive for human papillomavirus (HPV) who underwent p16/Ki-67 dual stain (DS) and HPV16/18 genotyping.

p16/Ki-67 DS was more effective at risk stratification for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 or more severe neoplasia (CIN3+) than cytologic testing alone, and women with positive DS results had a higher risk of developing CIN3+ (12%) than did women with cytologic testing alone (10%; P = .005). Women who were HPV16/18 negative were the most likely to not have CIN3+ if they had negative DS results, and DS strategies resulted in fewer overall colposcopies relative to CIN3+ detections, compared with cytologic testing alone.

“We found that, for primary HPV screening, DS has both higher sensitivity and specificity compared with cytologic testing for triage of HPV-positive women Because of the greater reassurance of negative DS results, screening intervals can be extended compared with the screening intervals after negative cytologic results. Dual stain reduces unnecessary colposcopy referral and unnecessary cervical biopsies, and may reduce unnecessary treatment compared with Papanicolaou cytologic testing,” Dr. Wentzensen and colleagues concluded. “Our estimates of sensitivity, absolute risk, and colposcopy referral for various triage strategies can guide implementation of primary HPV screening.”

Five authors of Sawaya et al. reported receiving grants from the National Cancer Institute, and Dr. Megan J. Huchko reported receiving a grant from the University of California, San Francisco, during that study. That study was funded by a grant from the NCI. Six authors from Wentzensen et al. reported receiving grants from the NCI or being employed by the NCI or NIH. Dr. Philip E. Castle reported receiving low-cost or free cervical screening tests from Roche, Becton Dickinson, Cepheid, and Arbor Vita Corp. The other authors from both studies reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCES: Sawaya GF et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2019. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0299; Wentzensen N et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2019. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0306.

Cervical cancer screening can be simplified and managed by reducing annual screening to every 3 years for women with normal cytological test results, Sarah Feldman, MD, MPH, wrote in a related editorial. There is evidence from large studies that this is possible for women with average risk of cervical cancer.

Primary human papillomavirus (HPV) screening also is an option for patients, and although there are no current guidelines, 2015 expert guidance states HPV16/18 genotyping and reflex cytologic testing should be used in cases of abnormal results. Transitioning from cytologic testing to primary HPV testing may require a period of using both tests in clinical practice, but this may raise issues with creating false positive results.

“The biggest challenge for cervical cancer screening, however, is likely not which test to use, but determining which women are at low enough risk of cervical cancer to undergo screening at less-frequent intervals,” wrote Dr. Feldman. In these cases, a better infrastructure where clinicians can access women’s prior screening results and make recommendations with decision support systems is needed.

But challenges remain. “These challenges include clinician and patient education and acceptance; access to primary HPV tests; the development of simple, easily implementable, and evidence-based management advice; and systems-based approaches to help clinicians implement optimal care.”

While women 30 years or older are likely to receive primary HPV testing as a standard of care, the risk of cervical cancer also should decrease as more children receive the HPV vaccine, concluded Dr. Feldman.

“Ultimately, once all children have received the HPV vaccination, the incidence of both cervical cancer and precancerous abnormalities should markedly diminish,” Dr. Feldman said. “Ultimately, we may hope to prevent all cervical cancer.”

Dr. Feldman is from the division of gynecologic oncology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. Her editorial accompanied the reports by Sawaya et al. and Wentzensen et al. (JAMA Intern Med. 2019. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0298). She reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

Cervical cancer screening can be simplified and managed by reducing annual screening to every 3 years for women with normal cytological test results, Sarah Feldman, MD, MPH, wrote in a related editorial. There is evidence from large studies that this is possible for women with average risk of cervical cancer.

Primary human papillomavirus (HPV) screening also is an option for patients, and although there are no current guidelines, 2015 expert guidance states HPV16/18 genotyping and reflex cytologic testing should be used in cases of abnormal results. Transitioning from cytologic testing to primary HPV testing may require a period of using both tests in clinical practice, but this may raise issues with creating false positive results.

“The biggest challenge for cervical cancer screening, however, is likely not which test to use, but determining which women are at low enough risk of cervical cancer to undergo screening at less-frequent intervals,” wrote Dr. Feldman. In these cases, a better infrastructure where clinicians can access women’s prior screening results and make recommendations with decision support systems is needed.

But challenges remain. “These challenges include clinician and patient education and acceptance; access to primary HPV tests; the development of simple, easily implementable, and evidence-based management advice; and systems-based approaches to help clinicians implement optimal care.”

While women 30 years or older are likely to receive primary HPV testing as a standard of care, the risk of cervical cancer also should decrease as more children receive the HPV vaccine, concluded Dr. Feldman.

“Ultimately, once all children have received the HPV vaccination, the incidence of both cervical cancer and precancerous abnormalities should markedly diminish,” Dr. Feldman said. “Ultimately, we may hope to prevent all cervical cancer.”

Dr. Feldman is from the division of gynecologic oncology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. Her editorial accompanied the reports by Sawaya et al. and Wentzensen et al. (JAMA Intern Med. 2019. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0298). She reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

Cervical cancer screening can be simplified and managed by reducing annual screening to every 3 years for women with normal cytological test results, Sarah Feldman, MD, MPH, wrote in a related editorial. There is evidence from large studies that this is possible for women with average risk of cervical cancer.

Primary human papillomavirus (HPV) screening also is an option for patients, and although there are no current guidelines, 2015 expert guidance states HPV16/18 genotyping and reflex cytologic testing should be used in cases of abnormal results. Transitioning from cytologic testing to primary HPV testing may require a period of using both tests in clinical practice, but this may raise issues with creating false positive results.

“The biggest challenge for cervical cancer screening, however, is likely not which test to use, but determining which women are at low enough risk of cervical cancer to undergo screening at less-frequent intervals,” wrote Dr. Feldman. In these cases, a better infrastructure where clinicians can access women’s prior screening results and make recommendations with decision support systems is needed.

But challenges remain. “These challenges include clinician and patient education and acceptance; access to primary HPV tests; the development of simple, easily implementable, and evidence-based management advice; and systems-based approaches to help clinicians implement optimal care.”

While women 30 years or older are likely to receive primary HPV testing as a standard of care, the risk of cervical cancer also should decrease as more children receive the HPV vaccine, concluded Dr. Feldman.

“Ultimately, once all children have received the HPV vaccination, the incidence of both cervical cancer and precancerous abnormalities should markedly diminish,” Dr. Feldman said. “Ultimately, we may hope to prevent all cervical cancer.”

Dr. Feldman is from the division of gynecologic oncology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. Her editorial accompanied the reports by Sawaya et al. and Wentzensen et al. (JAMA Intern Med. 2019. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0298). She reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

Less-frequent cytologic testing, followed by hrHPV tests

George F. Sawaya, MD, from the University of California, San Francisco, and colleagues enrolled 451 English-speaking or Spanish-speaking women aged 21-65 years from women’s health clinics between September 2014 and June 2016. The women were mean 38 years old, and 57% were nonwhite women. The researchers examined utilities for 23 different health states associated with cervical cancer, and created a Markov decision model of type-specific high-risk human papillomavirus (hrHPV)–induced cervical carcinogenesis.

The researchers evaluated 12 screening strategies, which included the following scenarios:

- For women aged 21-65 years, cytologic testing every 3 years; if atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASCUS) are found, repeat cytologic testing in 1 year or switch to immediate hrHPV triage.

- For women 21-29 years, cytologic testing every 3 years, and then followed with cytologic testing plus hrHPV testing (cotesting) for women 30-65 years old; if a normal cytologic test result and positive hrHPV test results, move to cotesting in 1 year or immediate genotyping triage.

- For women 21-29 years, cytologic testing every 3 years, and then followed with hrHPV testing alone every 3-5 years for women 30-65 years; if there are positive hrHPV results, move to immediate cytologic testing triage or immediate genotyping triage. Women with positive hrHPV and negative genotyping results receive additional cytologic testing triage.

In the strategies that switched the women from cytologic testing to hrHPV tests, the study also tested doing the switch at age 25 years rather than 30 years, the investigators reported.

Overall, with regard to cost, screening resulted in more cost savings ($1,267-$2,577) than not screening ($2,891 per woman). Women received the most benefit as measured by lifetime quality-adjusted life-years (QALY) if they received cytologic test every 3 years and received repeat testing for ASCUS. The strategy with the lowest cost was cytologic testing every 3 years and hrHPV triage for ASCUS ($1,267), and the strategy of 3-year cytology testing with repeat testing for ASCUS had more QALY but at a higher cost ($2,166). Other higher-cost strategies relative to QALYs included cotesting and primary hrHPV and also annual cytologic testing ($2,577).

“Both the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the American Cancer Society consider cotesting the preferred cervical cancer screening strategy, and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force considers it an alternative strategy,” Dr. Sawaya and colleagues noted. “Our findings challenge these endorsements.”

“Our analyses suggest that it is not cost effective to begin primary hrHPV testing prior to age 30 years, to perform hrHPV testing every 3 years, or to perform cytologic testing annually. Comparative modeling is needed to confirm these findings,” they concluded.

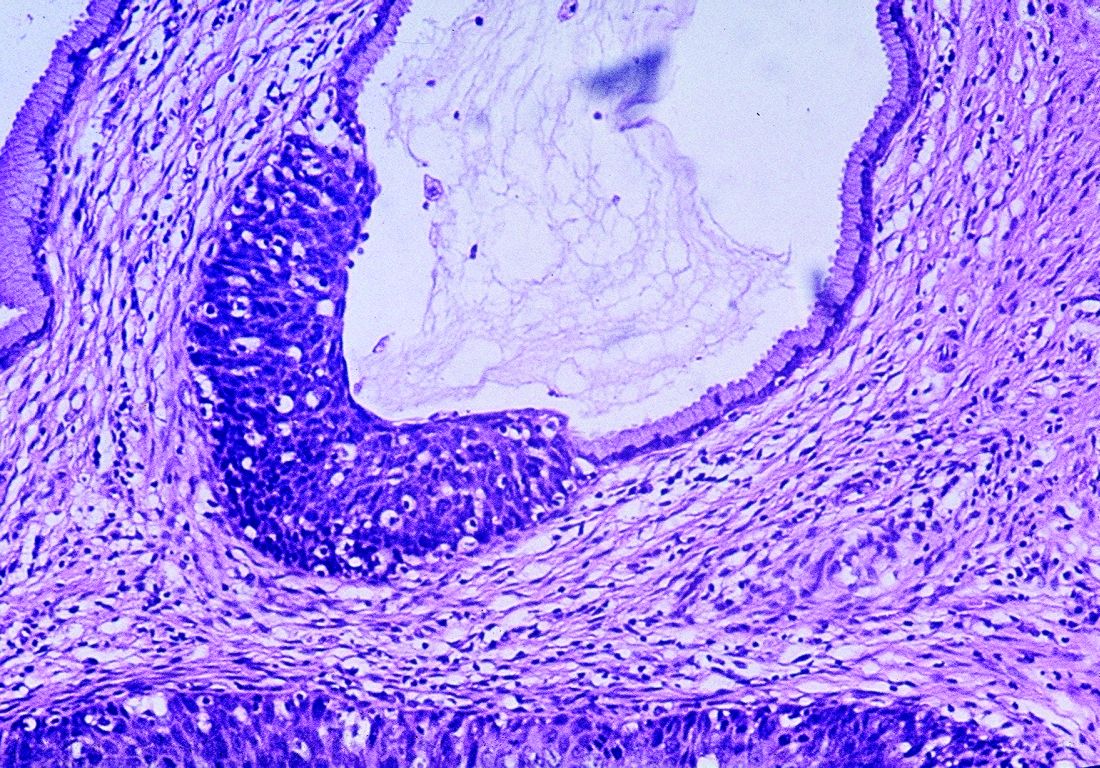

Dual stain vs. cytologic testing alone

In a second study, Nicolas Wentzensen, MD, PhD, from the National Cancer Institute and colleagues performed a prospective observational study of 3,225 women who tested positive for human papillomavirus (HPV) who underwent p16/Ki-67 dual stain (DS) and HPV16/18 genotyping.

p16/Ki-67 DS was more effective at risk stratification for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 or more severe neoplasia (CIN3+) than cytologic testing alone, and women with positive DS results had a higher risk of developing CIN3+ (12%) than did women with cytologic testing alone (10%; P = .005). Women who were HPV16/18 negative were the most likely to not have CIN3+ if they had negative DS results, and DS strategies resulted in fewer overall colposcopies relative to CIN3+ detections, compared with cytologic testing alone.

“We found that, for primary HPV screening, DS has both higher sensitivity and specificity compared with cytologic testing for triage of HPV-positive women Because of the greater reassurance of negative DS results, screening intervals can be extended compared with the screening intervals after negative cytologic results. Dual stain reduces unnecessary colposcopy referral and unnecessary cervical biopsies, and may reduce unnecessary treatment compared with Papanicolaou cytologic testing,” Dr. Wentzensen and colleagues concluded. “Our estimates of sensitivity, absolute risk, and colposcopy referral for various triage strategies can guide implementation of primary HPV screening.”

Five authors of Sawaya et al. reported receiving grants from the National Cancer Institute, and Dr. Megan J. Huchko reported receiving a grant from the University of California, San Francisco, during that study. That study was funded by a grant from the NCI. Six authors from Wentzensen et al. reported receiving grants from the NCI or being employed by the NCI or NIH. Dr. Philip E. Castle reported receiving low-cost or free cervical screening tests from Roche, Becton Dickinson, Cepheid, and Arbor Vita Corp. The other authors from both studies reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCES: Sawaya GF et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2019. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0299; Wentzensen N et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2019. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0306.

Less-frequent cytologic testing, followed by hrHPV tests

George F. Sawaya, MD, from the University of California, San Francisco, and colleagues enrolled 451 English-speaking or Spanish-speaking women aged 21-65 years from women’s health clinics between September 2014 and June 2016. The women were mean 38 years old, and 57% were nonwhite women. The researchers examined utilities for 23 different health states associated with cervical cancer, and created a Markov decision model of type-specific high-risk human papillomavirus (hrHPV)–induced cervical carcinogenesis.

The researchers evaluated 12 screening strategies, which included the following scenarios:

- For women aged 21-65 years, cytologic testing every 3 years; if atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASCUS) are found, repeat cytologic testing in 1 year or switch to immediate hrHPV triage.

- For women 21-29 years, cytologic testing every 3 years, and then followed with cytologic testing plus hrHPV testing (cotesting) for women 30-65 years old; if a normal cytologic test result and positive hrHPV test results, move to cotesting in 1 year or immediate genotyping triage.

- For women 21-29 years, cytologic testing every 3 years, and then followed with hrHPV testing alone every 3-5 years for women 30-65 years; if there are positive hrHPV results, move to immediate cytologic testing triage or immediate genotyping triage. Women with positive hrHPV and negative genotyping results receive additional cytologic testing triage.

In the strategies that switched the women from cytologic testing to hrHPV tests, the study also tested doing the switch at age 25 years rather than 30 years, the investigators reported.

Overall, with regard to cost, screening resulted in more cost savings ($1,267-$2,577) than not screening ($2,891 per woman). Women received the most benefit as measured by lifetime quality-adjusted life-years (QALY) if they received cytologic test every 3 years and received repeat testing for ASCUS. The strategy with the lowest cost was cytologic testing every 3 years and hrHPV triage for ASCUS ($1,267), and the strategy of 3-year cytology testing with repeat testing for ASCUS had more QALY but at a higher cost ($2,166). Other higher-cost strategies relative to QALYs included cotesting and primary hrHPV and also annual cytologic testing ($2,577).

“Both the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the American Cancer Society consider cotesting the preferred cervical cancer screening strategy, and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force considers it an alternative strategy,” Dr. Sawaya and colleagues noted. “Our findings challenge these endorsements.”

“Our analyses suggest that it is not cost effective to begin primary hrHPV testing prior to age 30 years, to perform hrHPV testing every 3 years, or to perform cytologic testing annually. Comparative modeling is needed to confirm these findings,” they concluded.

Dual stain vs. cytologic testing alone

In a second study, Nicolas Wentzensen, MD, PhD, from the National Cancer Institute and colleagues performed a prospective observational study of 3,225 women who tested positive for human papillomavirus (HPV) who underwent p16/Ki-67 dual stain (DS) and HPV16/18 genotyping.

p16/Ki-67 DS was more effective at risk stratification for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 or more severe neoplasia (CIN3+) than cytologic testing alone, and women with positive DS results had a higher risk of developing CIN3+ (12%) than did women with cytologic testing alone (10%; P = .005). Women who were HPV16/18 negative were the most likely to not have CIN3+ if they had negative DS results, and DS strategies resulted in fewer overall colposcopies relative to CIN3+ detections, compared with cytologic testing alone.

“We found that, for primary HPV screening, DS has both higher sensitivity and specificity compared with cytologic testing for triage of HPV-positive women Because of the greater reassurance of negative DS results, screening intervals can be extended compared with the screening intervals after negative cytologic results. Dual stain reduces unnecessary colposcopy referral and unnecessary cervical biopsies, and may reduce unnecessary treatment compared with Papanicolaou cytologic testing,” Dr. Wentzensen and colleagues concluded. “Our estimates of sensitivity, absolute risk, and colposcopy referral for various triage strategies can guide implementation of primary HPV screening.”

Five authors of Sawaya et al. reported receiving grants from the National Cancer Institute, and Dr. Megan J. Huchko reported receiving a grant from the University of California, San Francisco, during that study. That study was funded by a grant from the NCI. Six authors from Wentzensen et al. reported receiving grants from the NCI or being employed by the NCI or NIH. Dr. Philip E. Castle reported receiving low-cost or free cervical screening tests from Roche, Becton Dickinson, Cepheid, and Arbor Vita Corp. The other authors from both studies reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCES: Sawaya GF et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2019. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0299; Wentzensen N et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2019. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0306.

FROM JAMA INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Current ways of testing women for cervical testing may be replaced in the near future.

Major finding: Two studies challenge existing recommendations on when women should be screened for cervical cancer and explore how to manage abnormal results.

Study details: It is not cost effective to begin primary hrHPV testing prior to age 30 years, to perform hrHPV testing every 3 years, or to perform cytologic testing annually. Dual stain reduces unnecessary colposcopy referral and unnecessary cervical biopsies, and may reduce unnecessary treatment, compared with Papanicolaou cytologic testing.

Disclosures: Five authors from Sawaya et al. reported receiving grants from the National Cancer Institute and Dr. Megan J. Huchko reported receiving a grant from the University of California, San Francisco, during that study. That study was funded by a grant from the NCI. Six authors from Wentzensen et al. reported receiving grants from the NCI or being employed by the NCI or National Institutes of Health. Dr. Philip E. Castle reported receiving low-cost or free cervical screening tests from Roche, Becton Dickinson, Cepheid, and Arbor Vita Corp. The other authors from both studies reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

Sources: Sawaya GF et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2019. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0299; Wentzensen N et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2019. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0306.