User login

There are 2 leading types of dental diseases: tooth decay (dental caries or cavities) and gum disease (periodontal disease). Tooth decay is by far the more prevalent of the 2, causing a greater, needless loss in the quality of life.

Prevalence of Tooth Decay

Dental caries is a major public health problem. Even though in the past 50 years there has been a significant decline in dental caries, it is the most common ailment in the U.S., and large segments of the population experience various barriers to care. Among children and adolescents, dental caries is 4 to 5 times more common than asthma.1,2 Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2011-2012, show that among children aged 2 to 8 years, 37% had dental caries in their primary teeth. Among adolescents aged 12 to 19 years, the prevalence of dental caries in the permanent teeth was 58%. About 90% of adults aged ≥ 20 years had dental caries.3,4

Unmet Dental Needs

The real disease burden of dental caries is the amount of unmet needs or untreated decay. In recent years, there has been a shift in the peak prevalence of untreated tooth decay from children to adults, possibly attributable to socioecologic factors.3,5 The prevalence of untreated decay in children and adolescents was about 15%. However, the prevalence of untreated decay among adults aged 20 to 64 years was higher: 27% of the adults had decayed teeth that were left untreated.3,4

The rates of untreated decay among these adults were higher among Hispanics (36%) and non-Hispanic blacks (42%) than among non-Hispanic whites (22%) and non-Hispanic Asians (17%).3,4 Despite the decline in dental caries, disparities persist among different racial, ethnic, educational, and income groups; it remains a modern curse for large segments of the population.

Basics of Tooth Decay

Tooth decay is caused by Streptococcus mutans (S mutans) bacterial infection. The cariogenic bacteria are transmissible from mother or caregiver to children.6 After tooth eruption, the mouth is quickly colonized by S mutans. Even though the bacteria are ubiquitous, the disease burden is more concentrated in some populations.

What makes some people more susceptible to tooth decay? Contrary to popular belief, it is not caused by childbirth or low dietary intake of calcium.7,8 Tooth decay typically starts on the chewing surfaces or proximal contacts of teeth.

S mutans is introduced into the mouth principally from another person. The bacteria colonize the mouth and with the formation of plaques, adhere to the teeth. Plaque is the soft, sticky film formed on teeth from food degradation. The biofilm is conducive to bacterial proliferation and teeming with bacteria.

The S mutans bacteria break down sugars and produce lactic acids, which cause tooth decay—a process of demineralization, or loss of calcium phosphate, from the tooth structure.2,9 As a result, the tooth “softens” and eventually collapses on itself, forming a cavity. Tooth decay most commonly occurs at the occlusal (chewing) surfaces and the proximal contacts of teeth. The occlusal aspects of teeth have a natural pit-and-fissure morphology that facilitates bacterial adherence and colonization. The proximal contacts of teeth also facilitate adherence of plaque and bacteria.

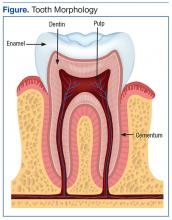

A tooth is made up of 3 layers. The outermost layer of the tooth crown is the enamel, which is the hardest or most mineralized part of the tooth—it is harder than bone. The next layer is the dentin, which has a higher percentage of organic material (collagen) and water than the enamel has and is softer. In the center of the tooth is the pulp (consisting of nerves and blood vessels), which keeps the tooth alive and provides sensation to the tooth. The outermost layer of the tooth root is cementum (instead of enamel), followed by dentin, which encases the pulp tissues contained within the root canals (Figure).

Process of Tooth Loss

At the early stage of tooth decay, when the decay is confined to the enamel, the tooth is asymptomatic, and the damage is reversible. When the decay extends into the dentin, restorations are a consideration. The further the decay extends toward the pulp, the greater the risk of tooth sensitivity and pain. Decay naturally progresses faster in the (less mineralized) dentin than when the decay is still confined to the enamel. If left unchecked, the decay may progress, and the bacteria eventually invade the pulp. At that point, there is risk of not only pain, but also swelling and tooth loss.

At the earlier stage of decay, a tooth may be treated with restorations, which are typically made of dental amalgam, resin (composite), glass ionomer, porcelain, or gold. When the bacteria have invaded the pulp, a dental restoration will not treat the pain and infection. Root canal therapy is needed to remove the infected tissues in the pulp chamber and root canals. Further, if the tooth is too compromised with extensive destruction from the decay or if there are financial or other barriers to root canal therapy, extraction is likely the only option.

Key to Oral Health

Personal daily oral hygiene (brushing and flossing) helps remove plaque from accumulating on tooth surfaces—especially the occlusal surfaces and proximal contacts, which are most prone to decay. Brushing teeth is of limited benefit without the use of fluoride toothpaste.8 The most important time for brushing is before bedtime, because less salivation occurs during sleep. Saliva helps clear fermented bacterial products, buffers the drop in pH, prevents demineralization, and enhances remineralizaton.10

Fluoride benefits children and adults of all ages, and comes in the form of fluoridated tap water, toothpaste, mouth rinse, and professionally applied gel and varnish. Fluoride occurs naturally in the environment, too. Its effect is mainly topical—fluoride gets incorporated into the tooth as fluorapatite, replacing the hydroxyapatite. Fluorapatite is harder than the hydroxyapatite; hence, the tooth is better able to resist demineralization by bacterial acid attacks.11 Professionally applied fluoride is generally recommended for high-risk patients, typically patients with high caries burden, ie, many decayed teeth. The best predictor of future caries is the past caries experience.

Sealants are thin, plastic coatings that are painted on to tooth occlusal surfaces, obliterating the pits and fissures normally found on posterior teeth. The smooth sealants effectively inhibit the colonization of S mutans on the occlusal aspects of teeth.12 Sealants are applied in dental offices (by the dentists or dental hygienists) or in school-based programs.

1. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Oral health in America: a report of the Surgeon General. http://www.nidcr.nih.gov/DataStatistics/SurgeonGeneral/Report/ExecutiveSummary.htm. Updated March 7, 2014. Accessed August 22, 2016.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hygiene-related diseases. http://www.cdc.gov/healthywater/hygiene/disease/dental_caries.html. Updated December 16, 2014. Accessed August 22, 2016.

3. Dye BA, Thornton-Evan G, Xianfen L, Iafolla TJ. Dental caries and sealant prevalence in children and adolescents in the United States, 2011-2012. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db191.pdf. Published March 2015. NCHS Data Brief. Accessed August 22, 2016.

4. Dye BA, Thornton-Evan G, Xianfen L, Iafolla TJ. Dental caries and tooth loss in adults in the United States, 2011-2012. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db197.pdf. NCHS Data Brief. Published May 2015. Accessed August 22, 2016.

5. Kassebaum NJ, Bernabé E, Dahiya M, Bhandari B, Murray CJ, Marcenes W. Global burden of untreated caries: a systematic review and metaregression. J Dent Res. 2015;94(5):650-658.

6. Smith RE, Badner VM, Morse DE, Freeman K. Maternal risk indicators for childhood caries in an inner city population. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2002;30(3):176-181.

7. Boggess KA, Urlaub DM, Moos MK, Polinkovsky M, El-Khorazaty J, Lorenz C. Knowledge and beliefs regarding oral health among pregnant women. J Am Dent Assoc. 2011;142(11):1275-1282.

8. Roberts-Thomson KF, Spencer AJ. Public knowledge of the prevention of dental decay and gum diseases. Aust Dent J. 1999;44(4):253-258.

9. Cochrane NJ, Cai F, Hug NL, Burrow MF, Reynolds EC. New approaches to enhanced remineralization of tooth enamel. J Dent Res. 2010;89(11):1187-1197.

10. Prabhakar AR, Dodawad R, Os R. Evaluation of flow Rate, pH, buffering capacity, calcium, total protein and total antioxidant levels of saliva in caries free and caries active children—an in vivo study. Int J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2009;2(1):9-12.

11. Hicks J, Garcia-Godoy F, Flaitz C. Biological factors in dental caries: role of remineralization and fluoride in the dynamic process of demineralization and remuneration (part 3). J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2004;28(3):203-214.

12. Azarpazhooh A, Main PA. Pit and fissure sealants in the prevention of dental caries in children and adolescents: a systematic review. J Can Dent Assoc. 2008;74(2):171-177.

There are 2 leading types of dental diseases: tooth decay (dental caries or cavities) and gum disease (periodontal disease). Tooth decay is by far the more prevalent of the 2, causing a greater, needless loss in the quality of life.

Prevalence of Tooth Decay

Dental caries is a major public health problem. Even though in the past 50 years there has been a significant decline in dental caries, it is the most common ailment in the U.S., and large segments of the population experience various barriers to care. Among children and adolescents, dental caries is 4 to 5 times more common than asthma.1,2 Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2011-2012, show that among children aged 2 to 8 years, 37% had dental caries in their primary teeth. Among adolescents aged 12 to 19 years, the prevalence of dental caries in the permanent teeth was 58%. About 90% of adults aged ≥ 20 years had dental caries.3,4

Unmet Dental Needs

The real disease burden of dental caries is the amount of unmet needs or untreated decay. In recent years, there has been a shift in the peak prevalence of untreated tooth decay from children to adults, possibly attributable to socioecologic factors.3,5 The prevalence of untreated decay in children and adolescents was about 15%. However, the prevalence of untreated decay among adults aged 20 to 64 years was higher: 27% of the adults had decayed teeth that were left untreated.3,4

The rates of untreated decay among these adults were higher among Hispanics (36%) and non-Hispanic blacks (42%) than among non-Hispanic whites (22%) and non-Hispanic Asians (17%).3,4 Despite the decline in dental caries, disparities persist among different racial, ethnic, educational, and income groups; it remains a modern curse for large segments of the population.

Basics of Tooth Decay

Tooth decay is caused by Streptococcus mutans (S mutans) bacterial infection. The cariogenic bacteria are transmissible from mother or caregiver to children.6 After tooth eruption, the mouth is quickly colonized by S mutans. Even though the bacteria are ubiquitous, the disease burden is more concentrated in some populations.

What makes some people more susceptible to tooth decay? Contrary to popular belief, it is not caused by childbirth or low dietary intake of calcium.7,8 Tooth decay typically starts on the chewing surfaces or proximal contacts of teeth.

S mutans is introduced into the mouth principally from another person. The bacteria colonize the mouth and with the formation of plaques, adhere to the teeth. Plaque is the soft, sticky film formed on teeth from food degradation. The biofilm is conducive to bacterial proliferation and teeming with bacteria.

The S mutans bacteria break down sugars and produce lactic acids, which cause tooth decay—a process of demineralization, or loss of calcium phosphate, from the tooth structure.2,9 As a result, the tooth “softens” and eventually collapses on itself, forming a cavity. Tooth decay most commonly occurs at the occlusal (chewing) surfaces and the proximal contacts of teeth. The occlusal aspects of teeth have a natural pit-and-fissure morphology that facilitates bacterial adherence and colonization. The proximal contacts of teeth also facilitate adherence of plaque and bacteria.

A tooth is made up of 3 layers. The outermost layer of the tooth crown is the enamel, which is the hardest or most mineralized part of the tooth—it is harder than bone. The next layer is the dentin, which has a higher percentage of organic material (collagen) and water than the enamel has and is softer. In the center of the tooth is the pulp (consisting of nerves and blood vessels), which keeps the tooth alive and provides sensation to the tooth. The outermost layer of the tooth root is cementum (instead of enamel), followed by dentin, which encases the pulp tissues contained within the root canals (Figure).

Process of Tooth Loss

At the early stage of tooth decay, when the decay is confined to the enamel, the tooth is asymptomatic, and the damage is reversible. When the decay extends into the dentin, restorations are a consideration. The further the decay extends toward the pulp, the greater the risk of tooth sensitivity and pain. Decay naturally progresses faster in the (less mineralized) dentin than when the decay is still confined to the enamel. If left unchecked, the decay may progress, and the bacteria eventually invade the pulp. At that point, there is risk of not only pain, but also swelling and tooth loss.

At the earlier stage of decay, a tooth may be treated with restorations, which are typically made of dental amalgam, resin (composite), glass ionomer, porcelain, or gold. When the bacteria have invaded the pulp, a dental restoration will not treat the pain and infection. Root canal therapy is needed to remove the infected tissues in the pulp chamber and root canals. Further, if the tooth is too compromised with extensive destruction from the decay or if there are financial or other barriers to root canal therapy, extraction is likely the only option.

Key to Oral Health

Personal daily oral hygiene (brushing and flossing) helps remove plaque from accumulating on tooth surfaces—especially the occlusal surfaces and proximal contacts, which are most prone to decay. Brushing teeth is of limited benefit without the use of fluoride toothpaste.8 The most important time for brushing is before bedtime, because less salivation occurs during sleep. Saliva helps clear fermented bacterial products, buffers the drop in pH, prevents demineralization, and enhances remineralizaton.10

Fluoride benefits children and adults of all ages, and comes in the form of fluoridated tap water, toothpaste, mouth rinse, and professionally applied gel and varnish. Fluoride occurs naturally in the environment, too. Its effect is mainly topical—fluoride gets incorporated into the tooth as fluorapatite, replacing the hydroxyapatite. Fluorapatite is harder than the hydroxyapatite; hence, the tooth is better able to resist demineralization by bacterial acid attacks.11 Professionally applied fluoride is generally recommended for high-risk patients, typically patients with high caries burden, ie, many decayed teeth. The best predictor of future caries is the past caries experience.

Sealants are thin, plastic coatings that are painted on to tooth occlusal surfaces, obliterating the pits and fissures normally found on posterior teeth. The smooth sealants effectively inhibit the colonization of S mutans on the occlusal aspects of teeth.12 Sealants are applied in dental offices (by the dentists or dental hygienists) or in school-based programs.

There are 2 leading types of dental diseases: tooth decay (dental caries or cavities) and gum disease (periodontal disease). Tooth decay is by far the more prevalent of the 2, causing a greater, needless loss in the quality of life.

Prevalence of Tooth Decay

Dental caries is a major public health problem. Even though in the past 50 years there has been a significant decline in dental caries, it is the most common ailment in the U.S., and large segments of the population experience various barriers to care. Among children and adolescents, dental caries is 4 to 5 times more common than asthma.1,2 Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2011-2012, show that among children aged 2 to 8 years, 37% had dental caries in their primary teeth. Among adolescents aged 12 to 19 years, the prevalence of dental caries in the permanent teeth was 58%. About 90% of adults aged ≥ 20 years had dental caries.3,4

Unmet Dental Needs

The real disease burden of dental caries is the amount of unmet needs or untreated decay. In recent years, there has been a shift in the peak prevalence of untreated tooth decay from children to adults, possibly attributable to socioecologic factors.3,5 The prevalence of untreated decay in children and adolescents was about 15%. However, the prevalence of untreated decay among adults aged 20 to 64 years was higher: 27% of the adults had decayed teeth that were left untreated.3,4

The rates of untreated decay among these adults were higher among Hispanics (36%) and non-Hispanic blacks (42%) than among non-Hispanic whites (22%) and non-Hispanic Asians (17%).3,4 Despite the decline in dental caries, disparities persist among different racial, ethnic, educational, and income groups; it remains a modern curse for large segments of the population.

Basics of Tooth Decay

Tooth decay is caused by Streptococcus mutans (S mutans) bacterial infection. The cariogenic bacteria are transmissible from mother or caregiver to children.6 After tooth eruption, the mouth is quickly colonized by S mutans. Even though the bacteria are ubiquitous, the disease burden is more concentrated in some populations.

What makes some people more susceptible to tooth decay? Contrary to popular belief, it is not caused by childbirth or low dietary intake of calcium.7,8 Tooth decay typically starts on the chewing surfaces or proximal contacts of teeth.

S mutans is introduced into the mouth principally from another person. The bacteria colonize the mouth and with the formation of plaques, adhere to the teeth. Plaque is the soft, sticky film formed on teeth from food degradation. The biofilm is conducive to bacterial proliferation and teeming with bacteria.

The S mutans bacteria break down sugars and produce lactic acids, which cause tooth decay—a process of demineralization, or loss of calcium phosphate, from the tooth structure.2,9 As a result, the tooth “softens” and eventually collapses on itself, forming a cavity. Tooth decay most commonly occurs at the occlusal (chewing) surfaces and the proximal contacts of teeth. The occlusal aspects of teeth have a natural pit-and-fissure morphology that facilitates bacterial adherence and colonization. The proximal contacts of teeth also facilitate adherence of plaque and bacteria.

A tooth is made up of 3 layers. The outermost layer of the tooth crown is the enamel, which is the hardest or most mineralized part of the tooth—it is harder than bone. The next layer is the dentin, which has a higher percentage of organic material (collagen) and water than the enamel has and is softer. In the center of the tooth is the pulp (consisting of nerves and blood vessels), which keeps the tooth alive and provides sensation to the tooth. The outermost layer of the tooth root is cementum (instead of enamel), followed by dentin, which encases the pulp tissues contained within the root canals (Figure).

Process of Tooth Loss

At the early stage of tooth decay, when the decay is confined to the enamel, the tooth is asymptomatic, and the damage is reversible. When the decay extends into the dentin, restorations are a consideration. The further the decay extends toward the pulp, the greater the risk of tooth sensitivity and pain. Decay naturally progresses faster in the (less mineralized) dentin than when the decay is still confined to the enamel. If left unchecked, the decay may progress, and the bacteria eventually invade the pulp. At that point, there is risk of not only pain, but also swelling and tooth loss.

At the earlier stage of decay, a tooth may be treated with restorations, which are typically made of dental amalgam, resin (composite), glass ionomer, porcelain, or gold. When the bacteria have invaded the pulp, a dental restoration will not treat the pain and infection. Root canal therapy is needed to remove the infected tissues in the pulp chamber and root canals. Further, if the tooth is too compromised with extensive destruction from the decay or if there are financial or other barriers to root canal therapy, extraction is likely the only option.

Key to Oral Health

Personal daily oral hygiene (brushing and flossing) helps remove plaque from accumulating on tooth surfaces—especially the occlusal surfaces and proximal contacts, which are most prone to decay. Brushing teeth is of limited benefit without the use of fluoride toothpaste.8 The most important time for brushing is before bedtime, because less salivation occurs during sleep. Saliva helps clear fermented bacterial products, buffers the drop in pH, prevents demineralization, and enhances remineralizaton.10

Fluoride benefits children and adults of all ages, and comes in the form of fluoridated tap water, toothpaste, mouth rinse, and professionally applied gel and varnish. Fluoride occurs naturally in the environment, too. Its effect is mainly topical—fluoride gets incorporated into the tooth as fluorapatite, replacing the hydroxyapatite. Fluorapatite is harder than the hydroxyapatite; hence, the tooth is better able to resist demineralization by bacterial acid attacks.11 Professionally applied fluoride is generally recommended for high-risk patients, typically patients with high caries burden, ie, many decayed teeth. The best predictor of future caries is the past caries experience.

Sealants are thin, plastic coatings that are painted on to tooth occlusal surfaces, obliterating the pits and fissures normally found on posterior teeth. The smooth sealants effectively inhibit the colonization of S mutans on the occlusal aspects of teeth.12 Sealants are applied in dental offices (by the dentists or dental hygienists) or in school-based programs.

1. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Oral health in America: a report of the Surgeon General. http://www.nidcr.nih.gov/DataStatistics/SurgeonGeneral/Report/ExecutiveSummary.htm. Updated March 7, 2014. Accessed August 22, 2016.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hygiene-related diseases. http://www.cdc.gov/healthywater/hygiene/disease/dental_caries.html. Updated December 16, 2014. Accessed August 22, 2016.

3. Dye BA, Thornton-Evan G, Xianfen L, Iafolla TJ. Dental caries and sealant prevalence in children and adolescents in the United States, 2011-2012. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db191.pdf. Published March 2015. NCHS Data Brief. Accessed August 22, 2016.

4. Dye BA, Thornton-Evan G, Xianfen L, Iafolla TJ. Dental caries and tooth loss in adults in the United States, 2011-2012. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db197.pdf. NCHS Data Brief. Published May 2015. Accessed August 22, 2016.

5. Kassebaum NJ, Bernabé E, Dahiya M, Bhandari B, Murray CJ, Marcenes W. Global burden of untreated caries: a systematic review and metaregression. J Dent Res. 2015;94(5):650-658.

6. Smith RE, Badner VM, Morse DE, Freeman K. Maternal risk indicators for childhood caries in an inner city population. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2002;30(3):176-181.

7. Boggess KA, Urlaub DM, Moos MK, Polinkovsky M, El-Khorazaty J, Lorenz C. Knowledge and beliefs regarding oral health among pregnant women. J Am Dent Assoc. 2011;142(11):1275-1282.

8. Roberts-Thomson KF, Spencer AJ. Public knowledge of the prevention of dental decay and gum diseases. Aust Dent J. 1999;44(4):253-258.

9. Cochrane NJ, Cai F, Hug NL, Burrow MF, Reynolds EC. New approaches to enhanced remineralization of tooth enamel. J Dent Res. 2010;89(11):1187-1197.

10. Prabhakar AR, Dodawad R, Os R. Evaluation of flow Rate, pH, buffering capacity, calcium, total protein and total antioxidant levels of saliva in caries free and caries active children—an in vivo study. Int J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2009;2(1):9-12.

11. Hicks J, Garcia-Godoy F, Flaitz C. Biological factors in dental caries: role of remineralization and fluoride in the dynamic process of demineralization and remuneration (part 3). J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2004;28(3):203-214.

12. Azarpazhooh A, Main PA. Pit and fissure sealants in the prevention of dental caries in children and adolescents: a systematic review. J Can Dent Assoc. 2008;74(2):171-177.

1. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Oral health in America: a report of the Surgeon General. http://www.nidcr.nih.gov/DataStatistics/SurgeonGeneral/Report/ExecutiveSummary.htm. Updated March 7, 2014. Accessed August 22, 2016.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hygiene-related diseases. http://www.cdc.gov/healthywater/hygiene/disease/dental_caries.html. Updated December 16, 2014. Accessed August 22, 2016.

3. Dye BA, Thornton-Evan G, Xianfen L, Iafolla TJ. Dental caries and sealant prevalence in children and adolescents in the United States, 2011-2012. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db191.pdf. Published March 2015. NCHS Data Brief. Accessed August 22, 2016.

4. Dye BA, Thornton-Evan G, Xianfen L, Iafolla TJ. Dental caries and tooth loss in adults in the United States, 2011-2012. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db197.pdf. NCHS Data Brief. Published May 2015. Accessed August 22, 2016.

5. Kassebaum NJ, Bernabé E, Dahiya M, Bhandari B, Murray CJ, Marcenes W. Global burden of untreated caries: a systematic review and metaregression. J Dent Res. 2015;94(5):650-658.

6. Smith RE, Badner VM, Morse DE, Freeman K. Maternal risk indicators for childhood caries in an inner city population. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2002;30(3):176-181.

7. Boggess KA, Urlaub DM, Moos MK, Polinkovsky M, El-Khorazaty J, Lorenz C. Knowledge and beliefs regarding oral health among pregnant women. J Am Dent Assoc. 2011;142(11):1275-1282.

8. Roberts-Thomson KF, Spencer AJ. Public knowledge of the prevention of dental decay and gum diseases. Aust Dent J. 1999;44(4):253-258.

9. Cochrane NJ, Cai F, Hug NL, Burrow MF, Reynolds EC. New approaches to enhanced remineralization of tooth enamel. J Dent Res. 2010;89(11):1187-1197.

10. Prabhakar AR, Dodawad R, Os R. Evaluation of flow Rate, pH, buffering capacity, calcium, total protein and total antioxidant levels of saliva in caries free and caries active children—an in vivo study. Int J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2009;2(1):9-12.

11. Hicks J, Garcia-Godoy F, Flaitz C. Biological factors in dental caries: role of remineralization and fluoride in the dynamic process of demineralization and remuneration (part 3). J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2004;28(3):203-214.

12. Azarpazhooh A, Main PA. Pit and fissure sealants in the prevention of dental caries in children and adolescents: a systematic review. J Can Dent Assoc. 2008;74(2):171-177.