User login

An opportunity for impact

Case

A 35-year-old woman with opioid use disorder (OUD) presents with fever, left arm redness, and swelling. She is admitted to the hospital for cellulitis treatment. On the day after admission she becomes agitated and develops nausea, diarrhea, and generalized pain. Opioid withdrawal is suspected. How should her opioid use be addressed while in the hospital?

Brief overview of the issue

Since 1999, there have been more than 800,000 deaths related to drug overdose in the United States, and in 2019 more than 70% of drug overdose deaths involved an opioid.1,2 Although effective treatments for OUD exist, less than 20% of those with OUD are engaged in treatment.3

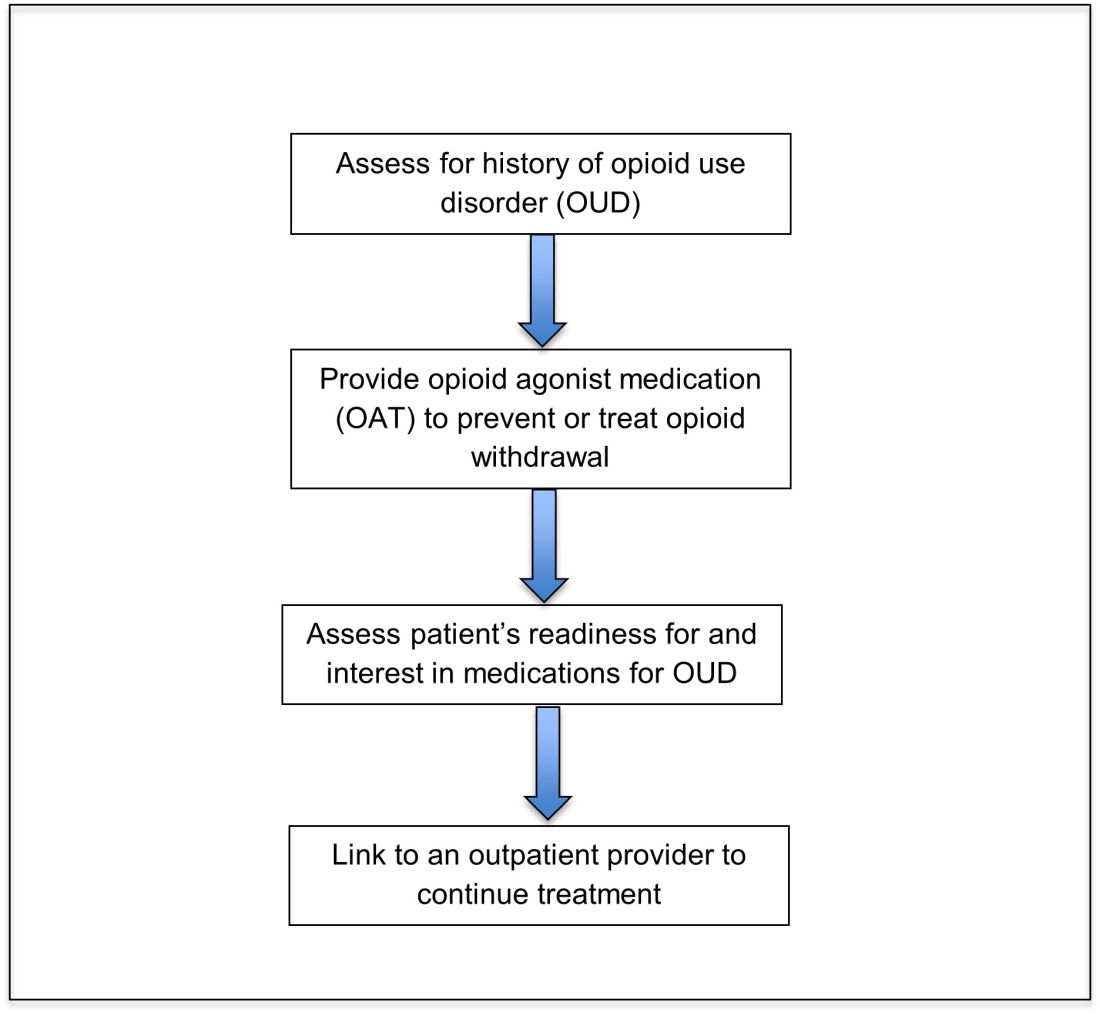

In America, 4%-11% of hospitalized patients have OUD. Hospitalized patients with OUD often experience stigma surrounding their disease, and many inpatient clinicians lack knowledge regarding the care of patients with OUD. As a result, withdrawal symptoms may go untreated, which can erode trust in the medical system and contribute to patients’ leaving the hospital before their primary medical issue is fully addressed. Therefore, it is essential that inpatient clinicians be familiar with the management of this complex and vulnerable patient population. Initiating treatment for OUD in the hospital setting is feasible and effective, and can lead to increased engagement in OUD treatment even after the hospital stay.

Overview of the data

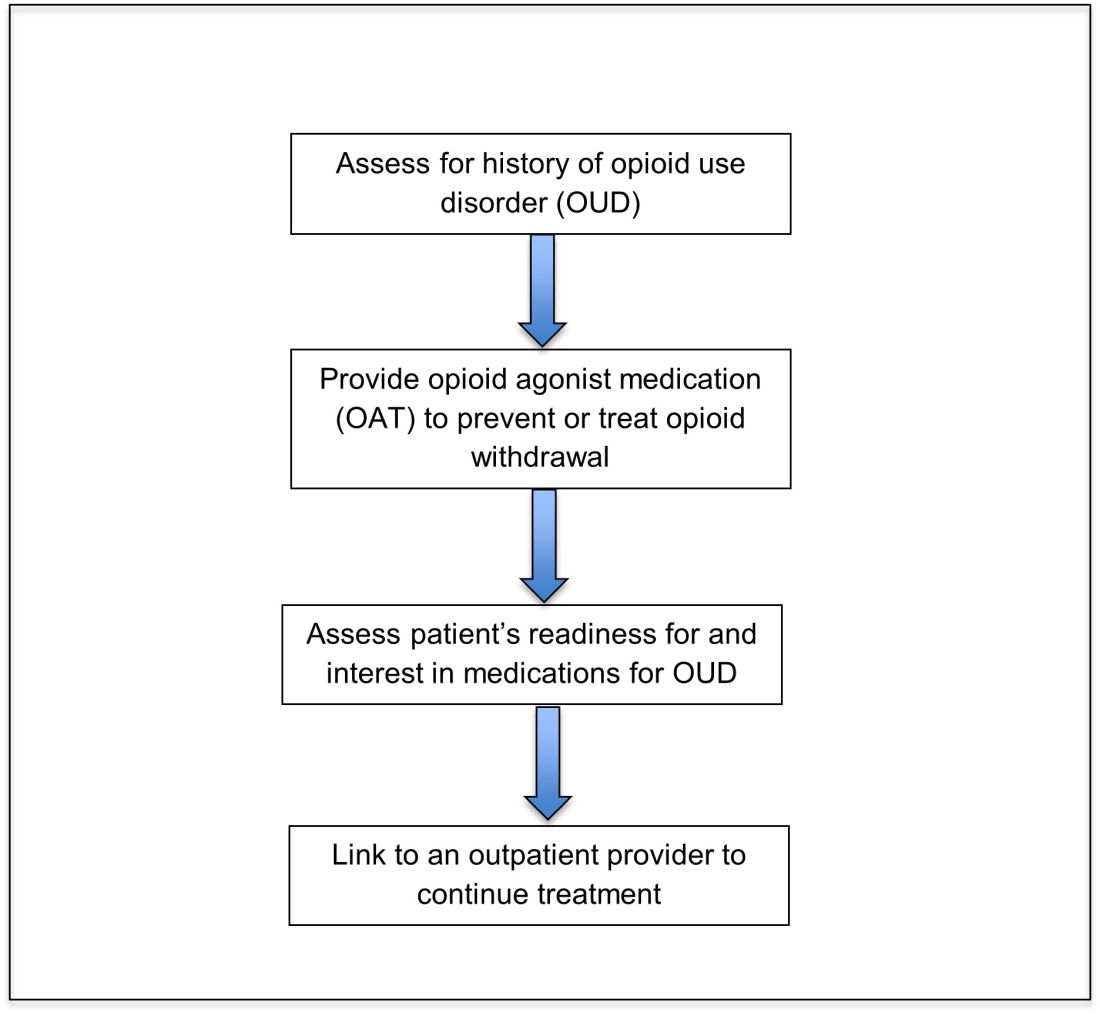

Assessing patients with suspected OUD

Assessment for OUD starts with an in-depth opioid use history including frequency, amount, and method of administration. Clinicians should gather information regarding use of other substances or nonprescribed medications, and take thorough psychiatric and social histories. A formal diagnosis of OUD can be made using the Fifth Edition Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders (DSM-5) diagnostic criteria.

Recognizing and managing opioid withdrawal

OUD in hospitalized patients often becomes apparent when patients develop signs and symptoms of withdrawal. Decreasing physical discomfort related to withdrawal can allow inpatient clinicians to address the condition for which the patient was hospitalized, help to strengthen the patient-clinician relationship, and provide an opportunity to discuss long-term OUD treatment.

Signs and symptoms of opioid withdrawal include anxiety, restlessness, irritability, generalized pain, rhinorrhea, yawning, lacrimation, piloerection, anorexia, and nausea. Withdrawal can last days to weeks, depending on the half-life of the opioid that was used. Opioids with shorter half-lives, such as heroin or oxycodone, cause withdrawal with earlier onset and shorter duration than do opioids with longer half-lives, such as methadone. The degree of withdrawal can be quantified with validated tools, such as the Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale (COWS).

Treatment of opioid withdrawal should generally include the use of an opioid agonist such as methadone or buprenorphine. A 2017 Cochrane meta-analysis found methadone or buprenorphine to be more effective than clonidine in alleviating symptoms of withdrawal and in retaining patients in treatment.4 Clonidine, an alpha2-adrenergic agonist that binds to receptors in the locus coeruleus, does not alleviate opioid cravings, but may be used as an adjunctive treatment for associated autonomic withdrawal symptoms. Other adjunctive medications include analgesics, antiemetics, antidiarrheals, and antihistamines.

Opioid agonist treatment for opioid use disorder

Opioid agonist treatment (OAT) with methadone or buprenorphine is associated with decreased mortality, opioid use, and infectious complications, but remains underutilized.5 Hospitalized patients with OUD are frequently managed with a rapid opioid detoxification and then discharged without continued OUD treatment. Detoxification alone can lead to a relapse rate as high as 90%.6 Patients are at increased risk for overdose after withdrawal due to loss of tolerance. Inpatient clinicians can close this OUD treatment gap by familiarizing themselves with OAT and offering to initiate OAT for maintenance treatment in interested patients. In one study, patients started on buprenorphine while hospitalized were more likely to be engaged in treatment and less likely to report drug use at follow-up, compared to patients who were referred without starting the medication.7

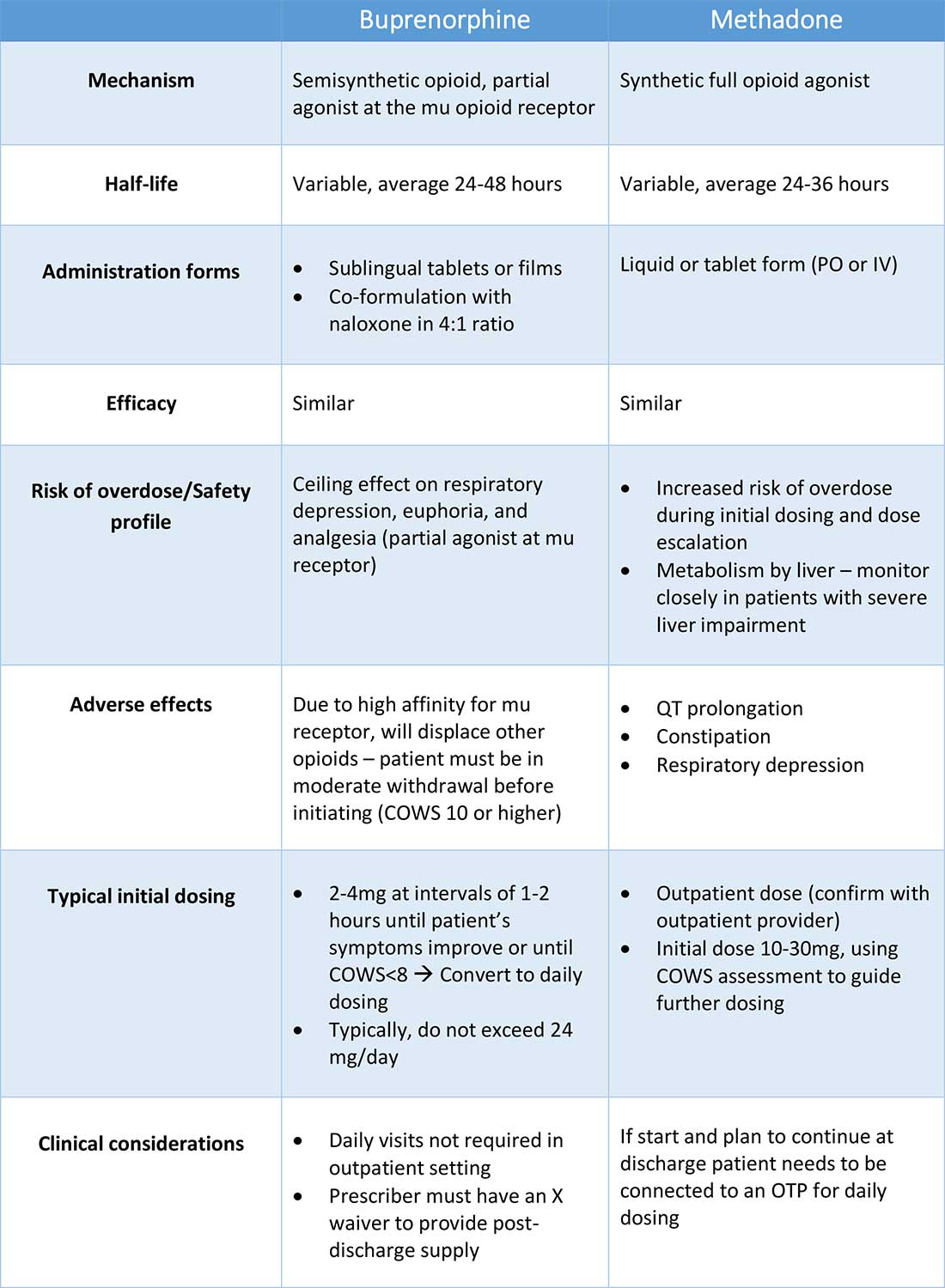

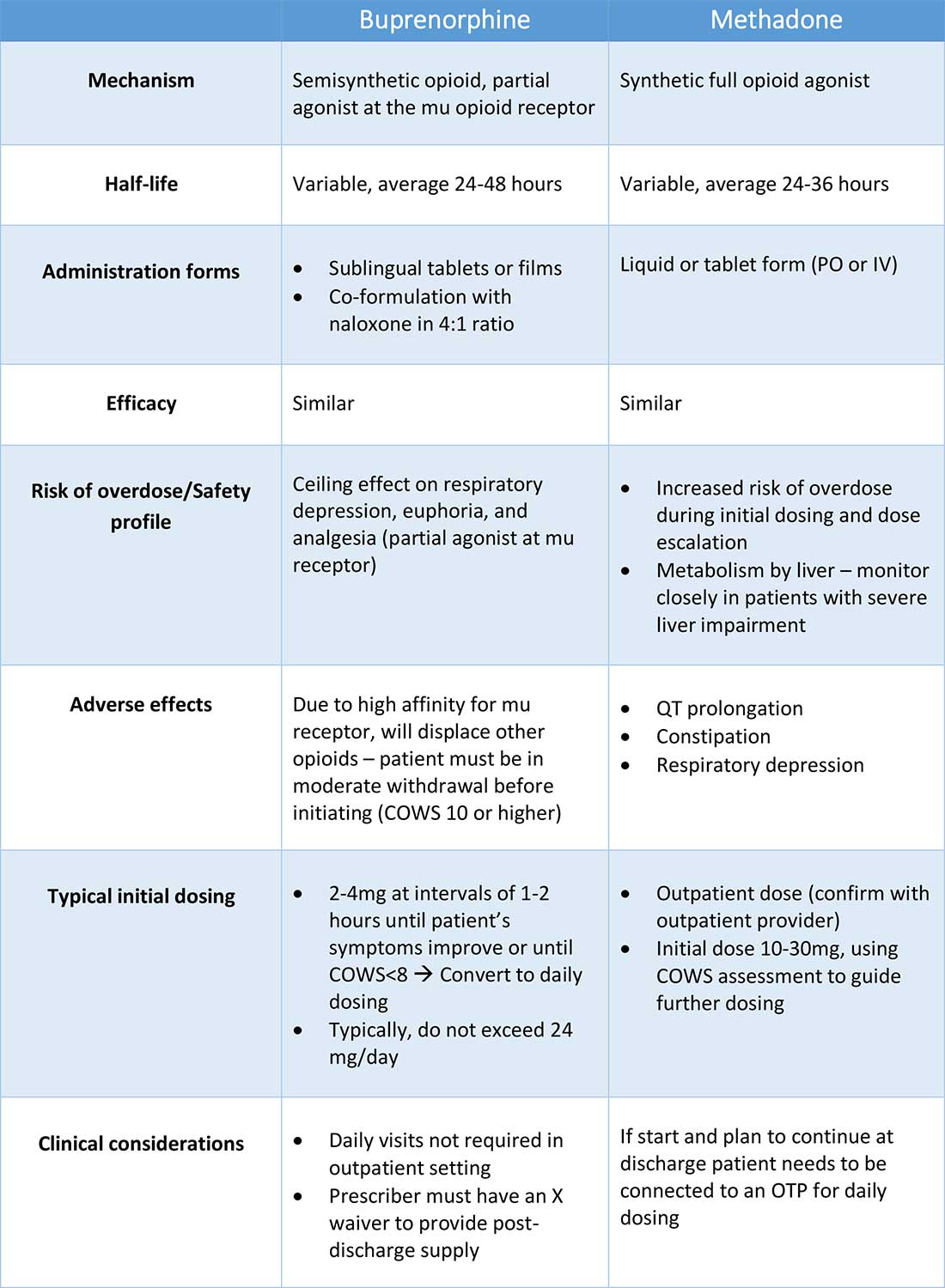

Buprenorphine

Buprenorphine is a partial agonist at the mu opioid receptor that can be ordered in the inpatient setting by any clinician. In the outpatient setting only DATA 2000 waivered clinicians can prescribe buprenorphine.8 Buprenorphine is most commonly coformulated with naloxone, an opioid antagonist, and is available in sublingual films or tablets. The naloxone component is not bioavailable when taken sublingually but becomes bioavailable if the drug is injected intravenously, leading to acute withdrawal.

Buprenorphine has a higher affinity for the mu opioid receptor than most opioids. If administered while other opioids are still present, it will displace the other opioid from the receptor but only partially stimulate the receptor, which can cause precipitated withdrawal. Buprenorphine initiation can start when the COWS score reflects moderate withdrawal. Many institutions use a threshold of 8-12 on the COWS scale. Typical dosing is 2-4 mg of buprenorphine at intervals of 1-2 hours as needed until the COWS score is less than 8, up to a maximum of 16 mg on day 1. The total dose from day 1 may be given as a daily dose beginning on day 2, up to a maximum total daily dose of 24 mg.

In recent years, a method of initiating buprenorphine called “micro-dosing” has gained traction. Very small doses of buprenorphine are given while a patient is receiving other opioids, thereby reducing the risk of precipitated withdrawal. This method can be helpful for patients who cannot tolerate withdrawal or who have recently taken long-acting opioids such as methadone. Such protocols should be utilized only at centers where consultation with an addiction specialist or experienced clinician is possible.

Despite evidence of buprenorphine’s efficacy, there are barriers to prescribing it. Physicians and advanced practitioners must be granted a waiver from the Drug Enforcement Administration to prescribe buprenorphine to outpatients. As of 2017, less than 10% of primary care physicians had obtained waivers.9 However, inpatient clinicians without a waiver can order buprenorphine and initiate treatment. Best practice is to do so with a specific plan for continuation at discharge. We encourage inpatient clinicians to obtain a waiver, so that a prescription can be given at discharge to bridge the patient to a first appointment with a community clinician who can continue treatment. As of April 27, 2021, providers treating fewer than 30 patients with OUD at one time may obtain a waiver without additional training.10

Methadone

Methadone is a full agonist at the mu opioid receptor. In the hospital setting, methadone can be ordered by any clinician to prevent and treat withdrawal. Commonly, doses of 10 mg can be given using the COWS score to guide the need for additional dosing. The patient can be reassessed every 1-2 hours to ensure that symptoms are improving, and that there is no sign of oversedation before giving additional methadone. For most patients, withdrawal can be managed with 20-40 mg of methadone daily.

In contrast to buprenorphine, methadone will not precipitate withdrawal and can be initiated even when patients are not yet showing withdrawal symptoms. Outpatient methadone treatment for OUD is federally regulated and can be delivered only in opioid treatment programs (OTPs).

Choosing methadone or buprenorphine in the inpatient setting

The choice between buprenorphine and methadone should take into consideration several factors, including patient preference, treatment history, and available outpatient treatment programs, which may vary widely by geographic region. Some patients benefit from the higher level of support and counseling available at OTPs. Methadone is available at all OTPs, and the availability of buprenorphine in this setting is increasing. Other patients may prefer the convenience and flexibility of buprenorphine treatment in an outpatient office setting.

Some patients have prior negative experiences with OAT. These can include prior precipitated withdrawal with buprenorphine induction, or negative experiences with the structure of OTPs. Clinicians are encouraged to provide counseling if patients have a history of precipitated withdrawal to assure them that this can be avoided with proper dosing. Clinicians should be familiar with available treatment options in their community and can refer to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) website to locate OTPs and buprenorphine prescribers.

Polypharmacy and safety

If combined with benzodiazepines, alcohol, or other sedating agents, methadone or buprenorphine can increase risk of overdose. However, OUD treatment should not be withheld because of other substance use. Clinicians initiating treatment should counsel patients on the risk of concomitant substance use and provide overdose prevention education.

A brief note on naltrexone

Naltrexone, an opioid antagonist, is used more commonly in outpatient addiction treatment than in the inpatient setting, but inpatient clinicians should be aware of its use. It is available in oral and long-acting injectable formulations. Its utility in the inpatient setting may be limited as safe administration requires 7-10 days of opioid abstinence.

Discharge planning

Patients with OUD or who are started on OAT during a hospitalization should be linked to continued outpatient treatment. Before discharge it is best to ensure vaccinations for HAV, HBV, pneumococcus, and tetanus are up to date, and perform screening for HIV, hepatitis C, tuberculosis, and sexually transmitted infections if appropriate. All patients with OUD should be prescribed or provided with take-home naloxone for overdose reversal. Patients can also be referred to syringe service programs for additional harm reduction counseling and services.

Application of the data to our patient

For our patient, either methadone or buprenorphine could be used to treat her withdrawal. The COWS score should be used to assess withdrawal severity, and to guide appropriate timing of medication initiation. If she wishes to continue OAT after discharge, she should be linked to a clinician who can engage her in ongoing medical care. Prior to discharge she should also receive relevant vaccines and screening for infectious diseases as outlined above, as well as take-home naloxone (or a prescription).

Bottom line

Inpatient clinicians can play a pivotal role in patients’ lives by ensuring that patients with OUD receive OAT and are connected to outpatient care at discharge.

Dr. Linker is assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. Ms. Hirt, Mr. Fine, and Mr. Villasanivis are medical students at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. Dr. Wang is assistant professor in the division of general internal medicine, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. Dr. Herscher is assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

References

1. Wide-ranging online data for epidemiologic research (WONDER). Atlanta, GA: CDC, National Center for Health Statistics; 2020. Available at http://wonder.cdc.gov.

2. Mattson CL et al. Trends and geographic patterns in drug and synthetic opioid overdose deaths – United States, 2013-2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:202-7. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7006a4.

3. Wakeman SE et al. Comparative effectiveness of different treatment pathways for opioid use disorder. JAMA Netw Open. 2020 Feb 5;3(2):e1920622. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.20622.

4. Gowing L et al. Buprenorphine for managing opioid withdrawal. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Feb;2017(2):CD002025. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002025.pub5.

5. Sordo L et al. Mortality risk during and after opioid substitution treatment: Systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMJ. 2017 Apr 26;357:j1550. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j1550.

6. Smyth BP et al. Lapse and relapse following inpatient treatment of opiate dependence. Ir Med J. 2010 Jun;103(6):176-9. Available at www.drugsandalcohol.ie/13405.

7. Liebschutz JM. Buprenorphine treatment for hospitalized, opioid-dependent patients: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014 Aug;174(8):1369-76. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.2556.

8. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (Aug 20, 2020) Statutes, Regulations, and Guidelines.

9. McBain RK et al. Growth and distribution of buprenorphine-waivered providers in the United States, 2007-2017. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172(7):504-6. doi: 10.7326/M19-2403.

10. HHS releases new buprenorphine practice guidelines, expanding access to treatment for opioid use disorder. Apr 27, 2021.

11. Herscher M et al. Diagnosis and management of opioid use disorder in hospitalized patients. Med Clin North Am. 2020 Jul;104(4):695-708. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2020.03.003.

Additional reading

Winetsky D. Expanding treatment opportunities for hospitalized patients with opioid use disorders. J Hosp Med. 2018 Jan;13(1):62-4. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2861.

Donroe JH. Caring for patients with opioid use disorder in the hospital. Can Med Assoc J. 2016 Dec 6;188(17-18):1232-9. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.160290.

Herscher M et al. Diagnosis and management of opioid use disorder in hospitalized patients. Med Clin North Am. 2020 Jul;104(4):695-708. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2020.03.003.

Key points

- Most patients with OUD are not engaged in evidence-based treatment. Clinicians have an opportunity to utilize the inpatient stay as a ‘reachable moment’ to engage patients with OUD in evidence-based treatment.

- Buprenorphine and methadone are effective opioid agonist medications used to treat OUD, and clinicians with the appropriate knowledge base can initiate either during the inpatient encounter, and link the patient to OUD treatment after the hospital stay.

Quiz

Caring for hospitalized patients with OUD

Most patients with OUD are not engaged in effective treatment. Hospitalization can be a ‘reachable moment’ to engage patients with OUD in evidence-based treatment.

1. Which is an effective and evidence-based medication for treating opioid withdrawal and OUD?

a) Naltrexone.

b) Buprenorphine.

c) Opioid detoxification.

d) Clonidine.

Explanation: Buprenorphine is effective for alleviating symptoms of withdrawal as well as for the long-term treatment of OUD. While naltrexone is also used to treat OUD, it is not useful for treating withdrawal. Clonidine can be a useful adjunctive medication for treating withdrawal but is not a long-term treatment for OUD. Nonpharmacologic detoxification is not an effective treatment for OUD and is associated with high relapse rates.

2. What scale can be used during a hospital stay to monitor patients with OUD at risk of opioid withdrawal, and to aid in buprenorphine initiation?

a) CIWA score.

b) PADUA score.

c) COWS score.

d) 4T score.

Explanation: COWS is the “clinical opiate withdrawal scale.” The COWS score should be calculated by a trained provider, and includes objective parameters (such as pulse) and subjective symptoms (such as GI upset, bone/joint aches.) It is recommended that agonist therapy be started when the COWS score is consistent with moderate withdrawal.

3. How can clinicians reliably find out if there are outpatient resources/clinics for patients with OUD in their area?

a) No way to find this out without personal knowledge.

b) Hospital providers and patients can visit www.samhsa.gov/find-help/national-helpline or call 1-800-662-HELP (4357) to find options for treatment for substance use disorders in their areas.

c) Dial “0” on any phone and ask.

d) Ask around at your hospital.

Explanation: The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) is an agency in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services that is engaged in public health efforts to reduce the impact of substance abuse and mental illness on local communities. The agency’s website has helpful information about resources for substance use treatment.

4. Patients with OUD should be prescribed and given training about what medication that can be lifesaving when given during an opioid overdose?

a) Aspirin.

b) Naloxone.

c) Naltrexone.

d) Clonidine.

Explanation: Naloxone can be life-saving in the setting of an overdose. Best practice is to provide naloxone and training to patients with OUD.

5. When patients take buprenorphine soon after taking other opioids, there is concern for the development of which reaction:

a) Precipitated withdrawal.

b) Opioid overdose.

c) Allergic reaction.

d) Intoxication.

Explanation: Administering buprenorphine soon after taking other opioids can cause precipitated withdrawal, as buprenorphine binds with higher affinity to the mu receptor than many opioids. Precipitated withdrawal causes severe discomfort and can be dangerous for patients.

An opportunity for impact

An opportunity for impact

Case

A 35-year-old woman with opioid use disorder (OUD) presents with fever, left arm redness, and swelling. She is admitted to the hospital for cellulitis treatment. On the day after admission she becomes agitated and develops nausea, diarrhea, and generalized pain. Opioid withdrawal is suspected. How should her opioid use be addressed while in the hospital?

Brief overview of the issue

Since 1999, there have been more than 800,000 deaths related to drug overdose in the United States, and in 2019 more than 70% of drug overdose deaths involved an opioid.1,2 Although effective treatments for OUD exist, less than 20% of those with OUD are engaged in treatment.3

In America, 4%-11% of hospitalized patients have OUD. Hospitalized patients with OUD often experience stigma surrounding their disease, and many inpatient clinicians lack knowledge regarding the care of patients with OUD. As a result, withdrawal symptoms may go untreated, which can erode trust in the medical system and contribute to patients’ leaving the hospital before their primary medical issue is fully addressed. Therefore, it is essential that inpatient clinicians be familiar with the management of this complex and vulnerable patient population. Initiating treatment for OUD in the hospital setting is feasible and effective, and can lead to increased engagement in OUD treatment even after the hospital stay.

Overview of the data

Assessing patients with suspected OUD

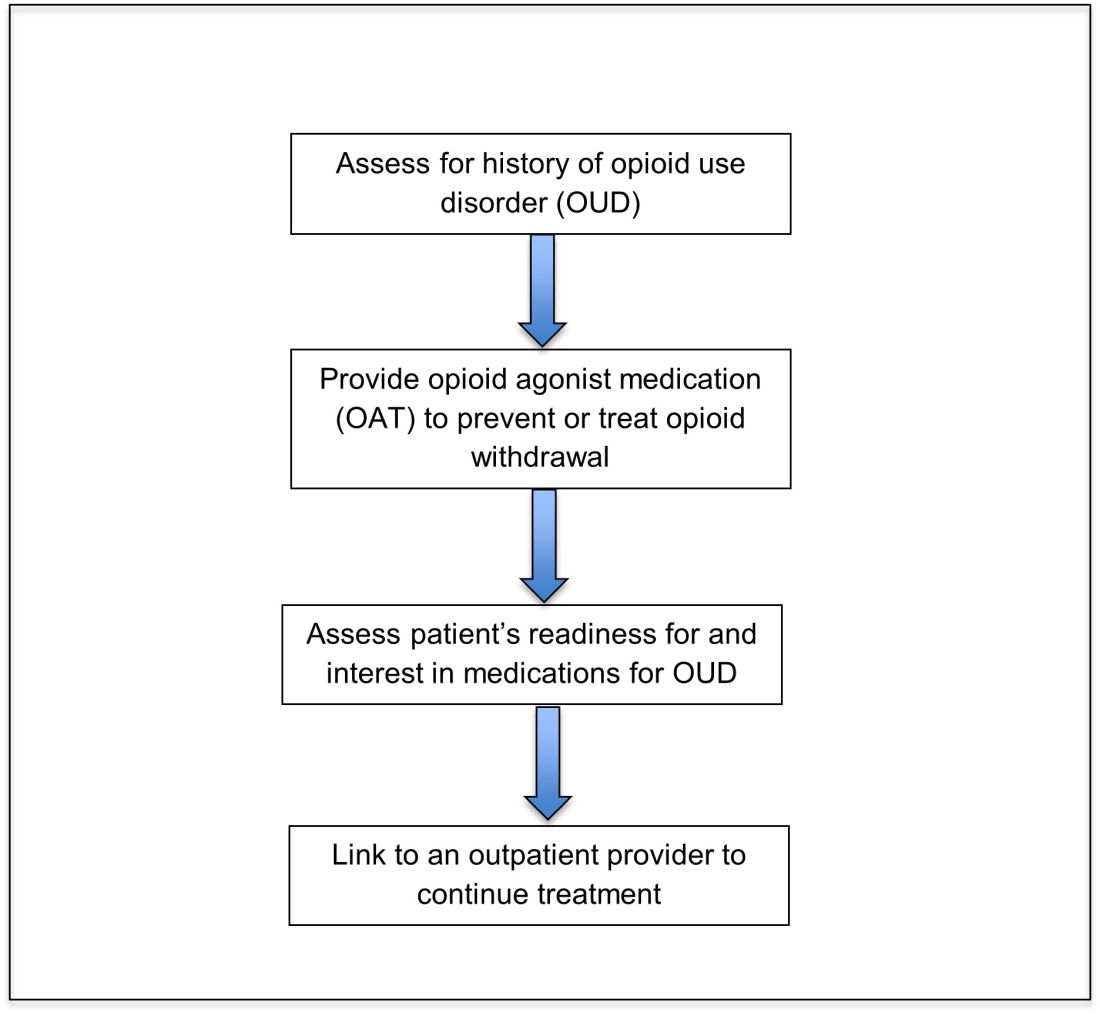

Assessment for OUD starts with an in-depth opioid use history including frequency, amount, and method of administration. Clinicians should gather information regarding use of other substances or nonprescribed medications, and take thorough psychiatric and social histories. A formal diagnosis of OUD can be made using the Fifth Edition Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders (DSM-5) diagnostic criteria.

Recognizing and managing opioid withdrawal

OUD in hospitalized patients often becomes apparent when patients develop signs and symptoms of withdrawal. Decreasing physical discomfort related to withdrawal can allow inpatient clinicians to address the condition for which the patient was hospitalized, help to strengthen the patient-clinician relationship, and provide an opportunity to discuss long-term OUD treatment.

Signs and symptoms of opioid withdrawal include anxiety, restlessness, irritability, generalized pain, rhinorrhea, yawning, lacrimation, piloerection, anorexia, and nausea. Withdrawal can last days to weeks, depending on the half-life of the opioid that was used. Opioids with shorter half-lives, such as heroin or oxycodone, cause withdrawal with earlier onset and shorter duration than do opioids with longer half-lives, such as methadone. The degree of withdrawal can be quantified with validated tools, such as the Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale (COWS).

Treatment of opioid withdrawal should generally include the use of an opioid agonist such as methadone or buprenorphine. A 2017 Cochrane meta-analysis found methadone or buprenorphine to be more effective than clonidine in alleviating symptoms of withdrawal and in retaining patients in treatment.4 Clonidine, an alpha2-adrenergic agonist that binds to receptors in the locus coeruleus, does not alleviate opioid cravings, but may be used as an adjunctive treatment for associated autonomic withdrawal symptoms. Other adjunctive medications include analgesics, antiemetics, antidiarrheals, and antihistamines.

Opioid agonist treatment for opioid use disorder

Opioid agonist treatment (OAT) with methadone or buprenorphine is associated with decreased mortality, opioid use, and infectious complications, but remains underutilized.5 Hospitalized patients with OUD are frequently managed with a rapid opioid detoxification and then discharged without continued OUD treatment. Detoxification alone can lead to a relapse rate as high as 90%.6 Patients are at increased risk for overdose after withdrawal due to loss of tolerance. Inpatient clinicians can close this OUD treatment gap by familiarizing themselves with OAT and offering to initiate OAT for maintenance treatment in interested patients. In one study, patients started on buprenorphine while hospitalized were more likely to be engaged in treatment and less likely to report drug use at follow-up, compared to patients who were referred without starting the medication.7

Buprenorphine

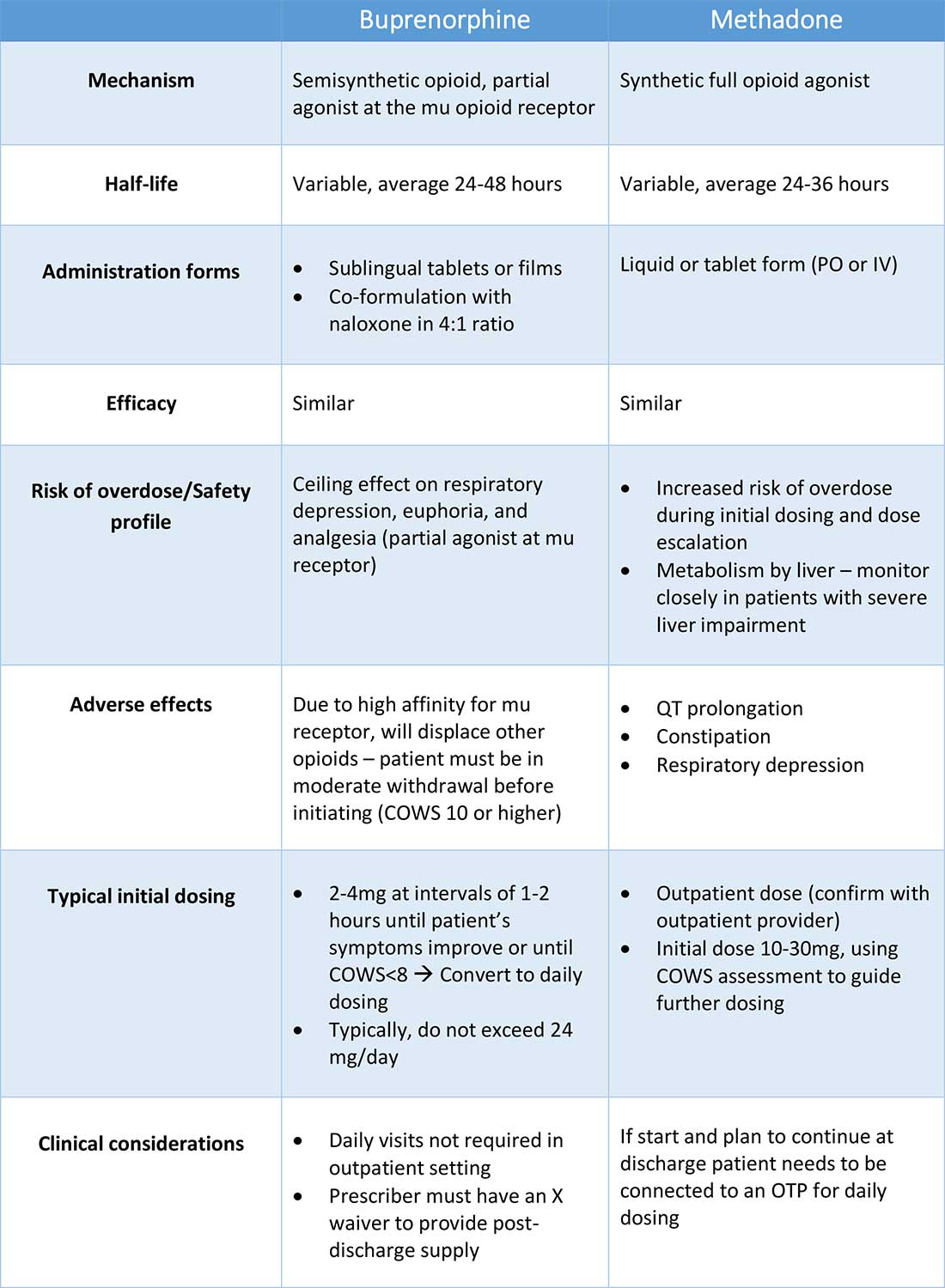

Buprenorphine is a partial agonist at the mu opioid receptor that can be ordered in the inpatient setting by any clinician. In the outpatient setting only DATA 2000 waivered clinicians can prescribe buprenorphine.8 Buprenorphine is most commonly coformulated with naloxone, an opioid antagonist, and is available in sublingual films or tablets. The naloxone component is not bioavailable when taken sublingually but becomes bioavailable if the drug is injected intravenously, leading to acute withdrawal.

Buprenorphine has a higher affinity for the mu opioid receptor than most opioids. If administered while other opioids are still present, it will displace the other opioid from the receptor but only partially stimulate the receptor, which can cause precipitated withdrawal. Buprenorphine initiation can start when the COWS score reflects moderate withdrawal. Many institutions use a threshold of 8-12 on the COWS scale. Typical dosing is 2-4 mg of buprenorphine at intervals of 1-2 hours as needed until the COWS score is less than 8, up to a maximum of 16 mg on day 1. The total dose from day 1 may be given as a daily dose beginning on day 2, up to a maximum total daily dose of 24 mg.

In recent years, a method of initiating buprenorphine called “micro-dosing” has gained traction. Very small doses of buprenorphine are given while a patient is receiving other opioids, thereby reducing the risk of precipitated withdrawal. This method can be helpful for patients who cannot tolerate withdrawal or who have recently taken long-acting opioids such as methadone. Such protocols should be utilized only at centers where consultation with an addiction specialist or experienced clinician is possible.

Despite evidence of buprenorphine’s efficacy, there are barriers to prescribing it. Physicians and advanced practitioners must be granted a waiver from the Drug Enforcement Administration to prescribe buprenorphine to outpatients. As of 2017, less than 10% of primary care physicians had obtained waivers.9 However, inpatient clinicians without a waiver can order buprenorphine and initiate treatment. Best practice is to do so with a specific plan for continuation at discharge. We encourage inpatient clinicians to obtain a waiver, so that a prescription can be given at discharge to bridge the patient to a first appointment with a community clinician who can continue treatment. As of April 27, 2021, providers treating fewer than 30 patients with OUD at one time may obtain a waiver without additional training.10

Methadone

Methadone is a full agonist at the mu opioid receptor. In the hospital setting, methadone can be ordered by any clinician to prevent and treat withdrawal. Commonly, doses of 10 mg can be given using the COWS score to guide the need for additional dosing. The patient can be reassessed every 1-2 hours to ensure that symptoms are improving, and that there is no sign of oversedation before giving additional methadone. For most patients, withdrawal can be managed with 20-40 mg of methadone daily.

In contrast to buprenorphine, methadone will not precipitate withdrawal and can be initiated even when patients are not yet showing withdrawal symptoms. Outpatient methadone treatment for OUD is federally regulated and can be delivered only in opioid treatment programs (OTPs).

Choosing methadone or buprenorphine in the inpatient setting

The choice between buprenorphine and methadone should take into consideration several factors, including patient preference, treatment history, and available outpatient treatment programs, which may vary widely by geographic region. Some patients benefit from the higher level of support and counseling available at OTPs. Methadone is available at all OTPs, and the availability of buprenorphine in this setting is increasing. Other patients may prefer the convenience and flexibility of buprenorphine treatment in an outpatient office setting.

Some patients have prior negative experiences with OAT. These can include prior precipitated withdrawal with buprenorphine induction, or negative experiences with the structure of OTPs. Clinicians are encouraged to provide counseling if patients have a history of precipitated withdrawal to assure them that this can be avoided with proper dosing. Clinicians should be familiar with available treatment options in their community and can refer to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) website to locate OTPs and buprenorphine prescribers.

Polypharmacy and safety

If combined with benzodiazepines, alcohol, or other sedating agents, methadone or buprenorphine can increase risk of overdose. However, OUD treatment should not be withheld because of other substance use. Clinicians initiating treatment should counsel patients on the risk of concomitant substance use and provide overdose prevention education.

A brief note on naltrexone

Naltrexone, an opioid antagonist, is used more commonly in outpatient addiction treatment than in the inpatient setting, but inpatient clinicians should be aware of its use. It is available in oral and long-acting injectable formulations. Its utility in the inpatient setting may be limited as safe administration requires 7-10 days of opioid abstinence.

Discharge planning

Patients with OUD or who are started on OAT during a hospitalization should be linked to continued outpatient treatment. Before discharge it is best to ensure vaccinations for HAV, HBV, pneumococcus, and tetanus are up to date, and perform screening for HIV, hepatitis C, tuberculosis, and sexually transmitted infections if appropriate. All patients with OUD should be prescribed or provided with take-home naloxone for overdose reversal. Patients can also be referred to syringe service programs for additional harm reduction counseling and services.

Application of the data to our patient

For our patient, either methadone or buprenorphine could be used to treat her withdrawal. The COWS score should be used to assess withdrawal severity, and to guide appropriate timing of medication initiation. If she wishes to continue OAT after discharge, she should be linked to a clinician who can engage her in ongoing medical care. Prior to discharge she should also receive relevant vaccines and screening for infectious diseases as outlined above, as well as take-home naloxone (or a prescription).

Bottom line

Inpatient clinicians can play a pivotal role in patients’ lives by ensuring that patients with OUD receive OAT and are connected to outpatient care at discharge.

Dr. Linker is assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. Ms. Hirt, Mr. Fine, and Mr. Villasanivis are medical students at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. Dr. Wang is assistant professor in the division of general internal medicine, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. Dr. Herscher is assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

References

1. Wide-ranging online data for epidemiologic research (WONDER). Atlanta, GA: CDC, National Center for Health Statistics; 2020. Available at http://wonder.cdc.gov.

2. Mattson CL et al. Trends and geographic patterns in drug and synthetic opioid overdose deaths – United States, 2013-2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:202-7. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7006a4.

3. Wakeman SE et al. Comparative effectiveness of different treatment pathways for opioid use disorder. JAMA Netw Open. 2020 Feb 5;3(2):e1920622. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.20622.

4. Gowing L et al. Buprenorphine for managing opioid withdrawal. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Feb;2017(2):CD002025. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002025.pub5.

5. Sordo L et al. Mortality risk during and after opioid substitution treatment: Systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMJ. 2017 Apr 26;357:j1550. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j1550.

6. Smyth BP et al. Lapse and relapse following inpatient treatment of opiate dependence. Ir Med J. 2010 Jun;103(6):176-9. Available at www.drugsandalcohol.ie/13405.

7. Liebschutz JM. Buprenorphine treatment for hospitalized, opioid-dependent patients: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014 Aug;174(8):1369-76. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.2556.

8. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (Aug 20, 2020) Statutes, Regulations, and Guidelines.

9. McBain RK et al. Growth and distribution of buprenorphine-waivered providers in the United States, 2007-2017. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172(7):504-6. doi: 10.7326/M19-2403.

10. HHS releases new buprenorphine practice guidelines, expanding access to treatment for opioid use disorder. Apr 27, 2021.

11. Herscher M et al. Diagnosis and management of opioid use disorder in hospitalized patients. Med Clin North Am. 2020 Jul;104(4):695-708. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2020.03.003.

Additional reading

Winetsky D. Expanding treatment opportunities for hospitalized patients with opioid use disorders. J Hosp Med. 2018 Jan;13(1):62-4. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2861.

Donroe JH. Caring for patients with opioid use disorder in the hospital. Can Med Assoc J. 2016 Dec 6;188(17-18):1232-9. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.160290.

Herscher M et al. Diagnosis and management of opioid use disorder in hospitalized patients. Med Clin North Am. 2020 Jul;104(4):695-708. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2020.03.003.

Key points

- Most patients with OUD are not engaged in evidence-based treatment. Clinicians have an opportunity to utilize the inpatient stay as a ‘reachable moment’ to engage patients with OUD in evidence-based treatment.

- Buprenorphine and methadone are effective opioid agonist medications used to treat OUD, and clinicians with the appropriate knowledge base can initiate either during the inpatient encounter, and link the patient to OUD treatment after the hospital stay.

Quiz

Caring for hospitalized patients with OUD

Most patients with OUD are not engaged in effective treatment. Hospitalization can be a ‘reachable moment’ to engage patients with OUD in evidence-based treatment.

1. Which is an effective and evidence-based medication for treating opioid withdrawal and OUD?

a) Naltrexone.

b) Buprenorphine.

c) Opioid detoxification.

d) Clonidine.

Explanation: Buprenorphine is effective for alleviating symptoms of withdrawal as well as for the long-term treatment of OUD. While naltrexone is also used to treat OUD, it is not useful for treating withdrawal. Clonidine can be a useful adjunctive medication for treating withdrawal but is not a long-term treatment for OUD. Nonpharmacologic detoxification is not an effective treatment for OUD and is associated with high relapse rates.

2. What scale can be used during a hospital stay to monitor patients with OUD at risk of opioid withdrawal, and to aid in buprenorphine initiation?

a) CIWA score.

b) PADUA score.

c) COWS score.

d) 4T score.

Explanation: COWS is the “clinical opiate withdrawal scale.” The COWS score should be calculated by a trained provider, and includes objective parameters (such as pulse) and subjective symptoms (such as GI upset, bone/joint aches.) It is recommended that agonist therapy be started when the COWS score is consistent with moderate withdrawal.

3. How can clinicians reliably find out if there are outpatient resources/clinics for patients with OUD in their area?

a) No way to find this out without personal knowledge.

b) Hospital providers and patients can visit www.samhsa.gov/find-help/national-helpline or call 1-800-662-HELP (4357) to find options for treatment for substance use disorders in their areas.

c) Dial “0” on any phone and ask.

d) Ask around at your hospital.

Explanation: The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) is an agency in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services that is engaged in public health efforts to reduce the impact of substance abuse and mental illness on local communities. The agency’s website has helpful information about resources for substance use treatment.

4. Patients with OUD should be prescribed and given training about what medication that can be lifesaving when given during an opioid overdose?

a) Aspirin.

b) Naloxone.

c) Naltrexone.

d) Clonidine.

Explanation: Naloxone can be life-saving in the setting of an overdose. Best practice is to provide naloxone and training to patients with OUD.

5. When patients take buprenorphine soon after taking other opioids, there is concern for the development of which reaction:

a) Precipitated withdrawal.

b) Opioid overdose.

c) Allergic reaction.

d) Intoxication.

Explanation: Administering buprenorphine soon after taking other opioids can cause precipitated withdrawal, as buprenorphine binds with higher affinity to the mu receptor than many opioids. Precipitated withdrawal causes severe discomfort and can be dangerous for patients.

Case

A 35-year-old woman with opioid use disorder (OUD) presents with fever, left arm redness, and swelling. She is admitted to the hospital for cellulitis treatment. On the day after admission she becomes agitated and develops nausea, diarrhea, and generalized pain. Opioid withdrawal is suspected. How should her opioid use be addressed while in the hospital?

Brief overview of the issue

Since 1999, there have been more than 800,000 deaths related to drug overdose in the United States, and in 2019 more than 70% of drug overdose deaths involved an opioid.1,2 Although effective treatments for OUD exist, less than 20% of those with OUD are engaged in treatment.3

In America, 4%-11% of hospitalized patients have OUD. Hospitalized patients with OUD often experience stigma surrounding their disease, and many inpatient clinicians lack knowledge regarding the care of patients with OUD. As a result, withdrawal symptoms may go untreated, which can erode trust in the medical system and contribute to patients’ leaving the hospital before their primary medical issue is fully addressed. Therefore, it is essential that inpatient clinicians be familiar with the management of this complex and vulnerable patient population. Initiating treatment for OUD in the hospital setting is feasible and effective, and can lead to increased engagement in OUD treatment even after the hospital stay.

Overview of the data

Assessing patients with suspected OUD

Assessment for OUD starts with an in-depth opioid use history including frequency, amount, and method of administration. Clinicians should gather information regarding use of other substances or nonprescribed medications, and take thorough psychiatric and social histories. A formal diagnosis of OUD can be made using the Fifth Edition Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders (DSM-5) diagnostic criteria.

Recognizing and managing opioid withdrawal

OUD in hospitalized patients often becomes apparent when patients develop signs and symptoms of withdrawal. Decreasing physical discomfort related to withdrawal can allow inpatient clinicians to address the condition for which the patient was hospitalized, help to strengthen the patient-clinician relationship, and provide an opportunity to discuss long-term OUD treatment.

Signs and symptoms of opioid withdrawal include anxiety, restlessness, irritability, generalized pain, rhinorrhea, yawning, lacrimation, piloerection, anorexia, and nausea. Withdrawal can last days to weeks, depending on the half-life of the opioid that was used. Opioids with shorter half-lives, such as heroin or oxycodone, cause withdrawal with earlier onset and shorter duration than do opioids with longer half-lives, such as methadone. The degree of withdrawal can be quantified with validated tools, such as the Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale (COWS).

Treatment of opioid withdrawal should generally include the use of an opioid agonist such as methadone or buprenorphine. A 2017 Cochrane meta-analysis found methadone or buprenorphine to be more effective than clonidine in alleviating symptoms of withdrawal and in retaining patients in treatment.4 Clonidine, an alpha2-adrenergic agonist that binds to receptors in the locus coeruleus, does not alleviate opioid cravings, but may be used as an adjunctive treatment for associated autonomic withdrawal symptoms. Other adjunctive medications include analgesics, antiemetics, antidiarrheals, and antihistamines.

Opioid agonist treatment for opioid use disorder

Opioid agonist treatment (OAT) with methadone or buprenorphine is associated with decreased mortality, opioid use, and infectious complications, but remains underutilized.5 Hospitalized patients with OUD are frequently managed with a rapid opioid detoxification and then discharged without continued OUD treatment. Detoxification alone can lead to a relapse rate as high as 90%.6 Patients are at increased risk for overdose after withdrawal due to loss of tolerance. Inpatient clinicians can close this OUD treatment gap by familiarizing themselves with OAT and offering to initiate OAT for maintenance treatment in interested patients. In one study, patients started on buprenorphine while hospitalized were more likely to be engaged in treatment and less likely to report drug use at follow-up, compared to patients who were referred without starting the medication.7

Buprenorphine

Buprenorphine is a partial agonist at the mu opioid receptor that can be ordered in the inpatient setting by any clinician. In the outpatient setting only DATA 2000 waivered clinicians can prescribe buprenorphine.8 Buprenorphine is most commonly coformulated with naloxone, an opioid antagonist, and is available in sublingual films or tablets. The naloxone component is not bioavailable when taken sublingually but becomes bioavailable if the drug is injected intravenously, leading to acute withdrawal.

Buprenorphine has a higher affinity for the mu opioid receptor than most opioids. If administered while other opioids are still present, it will displace the other opioid from the receptor but only partially stimulate the receptor, which can cause precipitated withdrawal. Buprenorphine initiation can start when the COWS score reflects moderate withdrawal. Many institutions use a threshold of 8-12 on the COWS scale. Typical dosing is 2-4 mg of buprenorphine at intervals of 1-2 hours as needed until the COWS score is less than 8, up to a maximum of 16 mg on day 1. The total dose from day 1 may be given as a daily dose beginning on day 2, up to a maximum total daily dose of 24 mg.

In recent years, a method of initiating buprenorphine called “micro-dosing” has gained traction. Very small doses of buprenorphine are given while a patient is receiving other opioids, thereby reducing the risk of precipitated withdrawal. This method can be helpful for patients who cannot tolerate withdrawal or who have recently taken long-acting opioids such as methadone. Such protocols should be utilized only at centers where consultation with an addiction specialist or experienced clinician is possible.

Despite evidence of buprenorphine’s efficacy, there are barriers to prescribing it. Physicians and advanced practitioners must be granted a waiver from the Drug Enforcement Administration to prescribe buprenorphine to outpatients. As of 2017, less than 10% of primary care physicians had obtained waivers.9 However, inpatient clinicians without a waiver can order buprenorphine and initiate treatment. Best practice is to do so with a specific plan for continuation at discharge. We encourage inpatient clinicians to obtain a waiver, so that a prescription can be given at discharge to bridge the patient to a first appointment with a community clinician who can continue treatment. As of April 27, 2021, providers treating fewer than 30 patients with OUD at one time may obtain a waiver without additional training.10

Methadone

Methadone is a full agonist at the mu opioid receptor. In the hospital setting, methadone can be ordered by any clinician to prevent and treat withdrawal. Commonly, doses of 10 mg can be given using the COWS score to guide the need for additional dosing. The patient can be reassessed every 1-2 hours to ensure that symptoms are improving, and that there is no sign of oversedation before giving additional methadone. For most patients, withdrawal can be managed with 20-40 mg of methadone daily.

In contrast to buprenorphine, methadone will not precipitate withdrawal and can be initiated even when patients are not yet showing withdrawal symptoms. Outpatient methadone treatment for OUD is federally regulated and can be delivered only in opioid treatment programs (OTPs).

Choosing methadone or buprenorphine in the inpatient setting

The choice between buprenorphine and methadone should take into consideration several factors, including patient preference, treatment history, and available outpatient treatment programs, which may vary widely by geographic region. Some patients benefit from the higher level of support and counseling available at OTPs. Methadone is available at all OTPs, and the availability of buprenorphine in this setting is increasing. Other patients may prefer the convenience and flexibility of buprenorphine treatment in an outpatient office setting.

Some patients have prior negative experiences with OAT. These can include prior precipitated withdrawal with buprenorphine induction, or negative experiences with the structure of OTPs. Clinicians are encouraged to provide counseling if patients have a history of precipitated withdrawal to assure them that this can be avoided with proper dosing. Clinicians should be familiar with available treatment options in their community and can refer to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) website to locate OTPs and buprenorphine prescribers.

Polypharmacy and safety

If combined with benzodiazepines, alcohol, or other sedating agents, methadone or buprenorphine can increase risk of overdose. However, OUD treatment should not be withheld because of other substance use. Clinicians initiating treatment should counsel patients on the risk of concomitant substance use and provide overdose prevention education.

A brief note on naltrexone

Naltrexone, an opioid antagonist, is used more commonly in outpatient addiction treatment than in the inpatient setting, but inpatient clinicians should be aware of its use. It is available in oral and long-acting injectable formulations. Its utility in the inpatient setting may be limited as safe administration requires 7-10 days of opioid abstinence.

Discharge planning

Patients with OUD or who are started on OAT during a hospitalization should be linked to continued outpatient treatment. Before discharge it is best to ensure vaccinations for HAV, HBV, pneumococcus, and tetanus are up to date, and perform screening for HIV, hepatitis C, tuberculosis, and sexually transmitted infections if appropriate. All patients with OUD should be prescribed or provided with take-home naloxone for overdose reversal. Patients can also be referred to syringe service programs for additional harm reduction counseling and services.

Application of the data to our patient

For our patient, either methadone or buprenorphine could be used to treat her withdrawal. The COWS score should be used to assess withdrawal severity, and to guide appropriate timing of medication initiation. If she wishes to continue OAT after discharge, she should be linked to a clinician who can engage her in ongoing medical care. Prior to discharge she should also receive relevant vaccines and screening for infectious diseases as outlined above, as well as take-home naloxone (or a prescription).

Bottom line

Inpatient clinicians can play a pivotal role in patients’ lives by ensuring that patients with OUD receive OAT and are connected to outpatient care at discharge.

Dr. Linker is assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. Ms. Hirt, Mr. Fine, and Mr. Villasanivis are medical students at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. Dr. Wang is assistant professor in the division of general internal medicine, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. Dr. Herscher is assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

References

1. Wide-ranging online data for epidemiologic research (WONDER). Atlanta, GA: CDC, National Center for Health Statistics; 2020. Available at http://wonder.cdc.gov.

2. Mattson CL et al. Trends and geographic patterns in drug and synthetic opioid overdose deaths – United States, 2013-2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:202-7. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7006a4.

3. Wakeman SE et al. Comparative effectiveness of different treatment pathways for opioid use disorder. JAMA Netw Open. 2020 Feb 5;3(2):e1920622. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.20622.

4. Gowing L et al. Buprenorphine for managing opioid withdrawal. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Feb;2017(2):CD002025. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002025.pub5.

5. Sordo L et al. Mortality risk during and after opioid substitution treatment: Systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMJ. 2017 Apr 26;357:j1550. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j1550.

6. Smyth BP et al. Lapse and relapse following inpatient treatment of opiate dependence. Ir Med J. 2010 Jun;103(6):176-9. Available at www.drugsandalcohol.ie/13405.

7. Liebschutz JM. Buprenorphine treatment for hospitalized, opioid-dependent patients: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014 Aug;174(8):1369-76. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.2556.

8. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (Aug 20, 2020) Statutes, Regulations, and Guidelines.

9. McBain RK et al. Growth and distribution of buprenorphine-waivered providers in the United States, 2007-2017. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172(7):504-6. doi: 10.7326/M19-2403.

10. HHS releases new buprenorphine practice guidelines, expanding access to treatment for opioid use disorder. Apr 27, 2021.

11. Herscher M et al. Diagnosis and management of opioid use disorder in hospitalized patients. Med Clin North Am. 2020 Jul;104(4):695-708. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2020.03.003.

Additional reading

Winetsky D. Expanding treatment opportunities for hospitalized patients with opioid use disorders. J Hosp Med. 2018 Jan;13(1):62-4. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2861.

Donroe JH. Caring for patients with opioid use disorder in the hospital. Can Med Assoc J. 2016 Dec 6;188(17-18):1232-9. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.160290.

Herscher M et al. Diagnosis and management of opioid use disorder in hospitalized patients. Med Clin North Am. 2020 Jul;104(4):695-708. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2020.03.003.

Key points

- Most patients with OUD are not engaged in evidence-based treatment. Clinicians have an opportunity to utilize the inpatient stay as a ‘reachable moment’ to engage patients with OUD in evidence-based treatment.

- Buprenorphine and methadone are effective opioid agonist medications used to treat OUD, and clinicians with the appropriate knowledge base can initiate either during the inpatient encounter, and link the patient to OUD treatment after the hospital stay.

Quiz

Caring for hospitalized patients with OUD

Most patients with OUD are not engaged in effective treatment. Hospitalization can be a ‘reachable moment’ to engage patients with OUD in evidence-based treatment.

1. Which is an effective and evidence-based medication for treating opioid withdrawal and OUD?

a) Naltrexone.

b) Buprenorphine.

c) Opioid detoxification.

d) Clonidine.

Explanation: Buprenorphine is effective for alleviating symptoms of withdrawal as well as for the long-term treatment of OUD. While naltrexone is also used to treat OUD, it is not useful for treating withdrawal. Clonidine can be a useful adjunctive medication for treating withdrawal but is not a long-term treatment for OUD. Nonpharmacologic detoxification is not an effective treatment for OUD and is associated with high relapse rates.

2. What scale can be used during a hospital stay to monitor patients with OUD at risk of opioid withdrawal, and to aid in buprenorphine initiation?

a) CIWA score.

b) PADUA score.

c) COWS score.

d) 4T score.

Explanation: COWS is the “clinical opiate withdrawal scale.” The COWS score should be calculated by a trained provider, and includes objective parameters (such as pulse) and subjective symptoms (such as GI upset, bone/joint aches.) It is recommended that agonist therapy be started when the COWS score is consistent with moderate withdrawal.

3. How can clinicians reliably find out if there are outpatient resources/clinics for patients with OUD in their area?

a) No way to find this out without personal knowledge.

b) Hospital providers and patients can visit www.samhsa.gov/find-help/national-helpline or call 1-800-662-HELP (4357) to find options for treatment for substance use disorders in their areas.

c) Dial “0” on any phone and ask.

d) Ask around at your hospital.

Explanation: The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) is an agency in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services that is engaged in public health efforts to reduce the impact of substance abuse and mental illness on local communities. The agency’s website has helpful information about resources for substance use treatment.

4. Patients with OUD should be prescribed and given training about what medication that can be lifesaving when given during an opioid overdose?

a) Aspirin.

b) Naloxone.

c) Naltrexone.

d) Clonidine.

Explanation: Naloxone can be life-saving in the setting of an overdose. Best practice is to provide naloxone and training to patients with OUD.

5. When patients take buprenorphine soon after taking other opioids, there is concern for the development of which reaction:

a) Precipitated withdrawal.

b) Opioid overdose.

c) Allergic reaction.

d) Intoxication.

Explanation: Administering buprenorphine soon after taking other opioids can cause precipitated withdrawal, as buprenorphine binds with higher affinity to the mu receptor than many opioids. Precipitated withdrawal causes severe discomfort and can be dangerous for patients.