User login

They’ve already been in the hospital three or four times, and now they’re back,” says Howard Epstein, MD, an internal medicine-trained hospitalist and the medical director of the palliative care program at Regions Hospital, St. Paul, Minn., describing patients who have acute exacerbations of their life-threatening chronic illnesses. “It’s a challenge we face all the time.”

Hospitalists spend a good deal of their time caring for dying patients, and data show that, by many accounts, they do it well.1 But just how near these patients are to death is often uncertain, especially for patients with diagnoses such as advanced heart and lung failure. Despite their slow decline, during any episode in which they are hospitalized, they may indeed die.

“As hospitalists, we encounter these situations regularly, maybe even daily,” wrote Steve Pantilat, MD, SHM past president, in his column in The Hospitalist (July/August 2005, p. 4): “We are the physicians who care for the seriously ill and the dying. The question is not whether we will take care of these patients; rather, when we do, will we be ready and able?”

End of life and palliative care are areas that hospitalists consider important but feel their training is generally inadequate.2 The conversations with patients and families can be challenging and take time, yet the time is worth the investment and they are a critical part of quality care. “We can learn how to conduct these discussions better,” wrote Dr. Pantilat, “and can practice phrases that will help them go more smoothly.”1,3-14 (See “Practice Phrases,” p. 34.)

Is there a difference in the way hospitalists treat those acute exacerbations if they come from or are attempting to return to their homes in the community or in long-term care? Not really, says Dr. Epstein. The exceptions may be in determining what kind of assistance a patient is getting or not getting outside the hospital (e.g., they’ll return home to a “supercaregiver spouse” versus returning to an assisted or skilled nursing facility). A patient in long-term care usually has multiple comorbidities, or their functional state has declined to the point where they need more assistance, palliative care only, or referral to hospice.

When a patient who has chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) comes in with an acute exacerbation, he says, it’s a good example of when you need to ask those clarifying questions. “If they’re deteriorating and you can paint that broad picture and help them to see that and that they’re going toward some inexorable decline,” says Dr. Epstein, “then they might make different decisions with that information.”

What’s Good in a Good Death?

Phrases such as “good death” and “dying with dignity” bear some interpretation, says Eva Chittenden, MD, a hospitalist with the University of California at San Francisco and a faculty member of its Palliative Care Leadership Center. Most palliative care experts might further define this to mean dying with appropriate respect for who that person is or who that person has been up until this point. A good death, she says, might better be referred to as a death that is “as good as possible.

“People say they want to die at home, but on the other hand, they also want to live forever,” says Dr. Chittenden. The reality is that most people die in acute-care hospitals while receiving invasive therapies.5-6,15 “We want a peaceful death, we want a pain-free death, we want a death where we’re surrounded by our families,” she says, “but at the same time we want to delay that forever. And those two things come into extreme conflict.7,9

“If you have cancer, maybe you don’t want to talk with your oncologist about death and dying because you want them to save your life. So you don’t even want to go there. And then you’re admitted to the hospital you’re told, ‘You’re extremely sick; you have pneumonia, but if we intubate you, we might be able to turn this situation around versus, if we don’t intubate you, you will surely die.’ And people don’t want to make that decision, because they’re not ready to die, even if ideally they’d want to have that good death,” says Dr. Chittenden, noting that not all providers have come to terms with how to use the available medical technology, when to stop using it, and how to talk about prognosis.

Talking about Prognosis

“In no case of serious illness … is predicting the future straightforward or meaningless,” writes Nicholas Christakis, in Death Foretold: Prophecy and Prognosis in Medical Care.16 “Part of the problem is that even formulating, much less communicating, a prediction about death is unpleasant, so physicians are inclined to refrain from it. But when they are able to formulate a prediction and fail to do so, the quality of care that patients receive may suffer.”

According to Dr. Epstein, you have to practice the conversations. “It’s a skill set, just like doing a bedside procedure … something that you have to do over and over and get comfortable doing,” he explains. “And it shocks people out of their seats when they actually hear the ‘D word.’ ” But part of meeting your responsibility to patients and their families requires speaking the truth.

Dr. Epstein says there are numerous resources available to help hospitalists overcome their discomfort and fears about being incorrect about how long the patient has to live. “I think it is OK to also say, ‘Look, I’m not God and I don't have a crystal ball, but I have seen lots of people in your situation and having watched them go through this point in their life, this is my expert opinion … ,’ ” he advises.

This involves telling the patient, “These are your chances of making a full recovery to the point where you might appreciate the quality of life you would have.” You don’t have to give numbers; you can use words such as good, bad, or poor.

For those with advanced systemic failure, you might discuss prognoses in words that patients can better understand by making a comparison to someone has a cancer diagnosis. For instance, “I’ll say, ‘Your chances for living for a year are about as good as someone living with metastatic lung cancer,’ ” says Dr. Epstein. “I think that’s something that patients grasp a lot easier.”

In addition to the fear of being incorrect in prognosticating, physicians often don’t want their patients to lose hope. “Whereas in truth people are already thinking about these things, and there are studies that show people want their doctors to bring it up,” says Dr. Chittenden.7

A number of these studies were conducted by Dr. Christakis and Elizabeth Lamont, MD, a medical oncologist now practicing at Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center and assistant professor of medicine and health care policy at Harvard Medical School.15,17-19 Their findings have shown that doctors’ inaccuracies in their prognoses for terminally ill patients are systematically optimistic and that this may adversely affect the quality of care given to patients near the end of life.17

In their study of 326 patients in five hospices in Chicago, Drs. Christakis and Lamont showed that even if patients with cancer requested survival estimates, doctors would provide a frank estimate only 37% of the time and would provide no estimate, a conscious overestimate, or a conscious underestimate most of the time (63%).18 This, they concluded, may contribute to the observed disparities between physicians’ and patients’ estimates of survival.

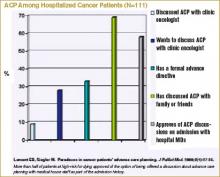

Dr. Lamont’s interest in prognosis at end of life and the subject of advanced care planning arose from her experiences as a resident when she was cross-covering the oncology services. “I would be called to see [for example] a 35-year-old woman with widely metastatic breast cancer including brain metastases who was clearly at the end of life,” she says. “She became acutely short of breath, and my concern was that she was having a pulmonary embolism. … I was trying to decide whether to send her to the ICU. I was trying to inform her about the risks of anticoagulation … and I asked, ‘Have you talked about whether or not you’d want to go to the intensive care unit, whether or not you’d want your heart restarted, whether or not you’d want to be put on a ventilator if you couldn’t be breathe on your own; have you talked about these kinds of things with your oncologist?’ [Her answer was,] ‘Oh, no!’ ” Dr. Lamont figured that if she would have these conversations anyway, it would make more sense to have them as part of the admission history and physical. The study she subsequently designed and conducted involved 111 newly admitted patients with cancer whom she interviewed about (among other things) whether they had advanced care preferences (ACP) and whether they had discussed advanced directives with their medical oncologists. Only 9% of patients said that they had advanced directives, although 69% of patients had discussed their ACP with someone else (such as family).19 (See “ACP among Hospitalized Cancer Patients,” below.) However, 58% of patients approved of the option of being offered a discussion about advanced care planning with medical house staff as part of the admission history.

In other words, for the population of patients at high risk for dying during their current hospitalization, more than half would be open to discussing ACP with those whom they do not know well—such as hospitalists.

Advance Care Planning

A study just published in Archives of Internal Medicine suggests that elderly people who suffer from terminal illnesses become increasingly more willing to accept a life-preserving treatment, resulting in further physical disability or more pain if they were already diminished in those domains.20 Terri Fried, MD, an associate professor of internal medicine at Yale, and her colleagues studied 226 older men and women with advanced cancer, congestive heart failure (CHF), or COPD. In the course of in-home interviews conducted over two years, the investigators explored whether the participants would accept life-prolonging treatment if it resulted in one of four diminished health states: mild physical disability, severe physical disability, mental disability, or moderately severe daily pain.

Results showed that the likelihood of a treatment resulting in mild or severe functional disability rating as acceptable increased with each month of participation in the study. More than half of the patients had prepared living wills, and these individuals were more likely to prefer death to disability, but preferences could also change. These findings suggest that even though providers, patients, and families may have already had conversations about advance care planning, a patient’s change in health status might herald the need for a new conversation.

Dr. Lamont says there are two major areas in which hospitalists can politically advocate for changes that could facilitate better advance care planning. The first is to adopt the model proposed in her study, whereby patients are queried regarding advanced directives as part of the admission history.19 Patients for whom this could be added as a new data field would include, for example, those with advanced cancer, metastatic solid tumors, relapsed leukemia, relapsed lymphoma, or with acute exacerbations of illnesses such as CHF or COPD. The second area where hospitalists could advocate for change is national healthcare policy. Like a number of others, Dr. Lamont believes CMS should begin reimbursing for high-quality end-of-life care discussions, the measures of which would be determined at both local and national levels.

Communication Training

“The more hospital medicine training gets incorporated into internal medicine residency,” says Dr. Epstein, “the greater the opportunity to train new hospitalists to have these difficult conversations: how to have a family meeting, to identify the issues, to see if there are any ethical issues involved, any legal issues, and how to negotiate a reasonable plan of care based on the patient’s goals.”2,8,21

In addition to helping with control of physical symptoms, such as pain and nausea control, physicians facilitate decision-making. “We try to address a lot of the existential and reconciliation and legacy issues,” says Dr. Chittenden. Because of the number of situations in which the patient is a woman or man in their 40s or 50s who have young children, she says, “we help the parents come to terms with this and get our child-life specialist involved to help the parents think about how to talk with the kids.”

Because of the growth of the palliative care movement, the training is beginning to improve. “The LCME [Liaison Committee on Medical Education], the licensure group for medical schools, mandates that there be some end-of-life care exposure,” says Dr. Chittenden. “And the ACGME [Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education], which licenses the residency programs, strongly suggests that there be opportunities to learn about this. … Slowly but surely we are realizing this needs to happen, but we are far from doing it well.”

What would be ideal? A two-week rotation for residents in a palliative care service? “That would be wonderful,” says Dr. Epstein. “As more palliative care services pop up across the country, the chance of that happening would increase. … And even if you’re not in palliative care and you’re a hospitalist and you do these kinds of things well, the residents should be watching you have those kinds of conversations.”

Explaining that he is paraphrasing Mark Leenay, MD, the former program director at Fairview-University, Minnesota, and the physician who spearheaded the development of a clinical team that comprehensively addresses the multiple aspects of suffering from life-threatening illness, Dr. Epstein says: “I can train anybody to do symptom management in hospice, but how to walk into a room and understand … and negotiate the family dynamics and the patient’s plan of care … to communicate on different levels with different people with … their own agendas, and all the pieces of information … [and different interpretations] … to take it all in and digest it for that meeting and spit it out in a way [in which] everyone can relate and come to some sort of consensus, hopefully, at the end of the meeting? That’s the art. And that takes practice.”

Conclusion

Patients with life-threatening chronic illnesses are often admitted to the hospital multiple times in the course of the period that could be considered the end of life. Important nonmedical issues for hospitalists to address at each new admission include communication regarding prognosis and advance care planning, and addressing existential issues greatly contributes to the quality of care. TH

Resources

- The Hastings Center is involved in bioethics and other issues surrounding end-of-life care (www.thehastingscenter.org/default.asp). The Special Report listed in “References” is downloadable from their Web site.23

- Education in Palliative and End-of-Life Care (EPEC) curriculum (www.epec.net).

- The American Board of Hospice and Palliative Medicine (www.abhpm.org).

- The American Association of Hospice and Palliative Medicine (www.aahpm.org).

- Harvard’s Center for Palliative Care offers courses that emphasize teaching (www.hms.harvard.edu/cdi/pallcare/).

- The Center to Advance Palliative Care (CAPC), Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, serves as a resource for hospital-based palliative care program development. CAPC supports six regional Palliative Care Leadership Centers (www.capc.org).

The following Web sites include models for advance directives.

- Five Wishes: www.agingwithdignity.org

- Individual decisions: www.newgrangepress.com

- Respecting choices at end of life: www.gundersenlutheran.com/eolprograms

- Physician orders for life-sustaining treatment: www.polst.org

References

- Auerbach AD, Pantilat SZ. End-of-Life care in a voluntary hospitalist model: effects on communication, processes of care, and patient symptoms. Am J Med. 2004 May 15;116(10):669-675.

- Plauth WH, Pantilat SZ, Wachter RM, et al. Hospitalists' perceptions of their residency training needs: result of a national survey. Am J Med. 2001;111(3):247-254.

- Lo B, Quill TE, Tulsky J. Discussing palliative care with patients. ACP--ASIM End-of-Life Care Consensus Panel. American College of Physicians--American Society of Internal Medicine. Ann Intern Med. 1999 May 4;130(9):744-749.

- Quill TE. Initiating end-of-life discussions with seriously ill patients: addressing the "elephant in the room." JAMA. 2000 Nov 15;284(19):2502-2507.

- Kaufman SR. And a Time to Die: How American Hospitals Shape the End of Life. New York: Scribner; 2005.

- Kaufman SR. A commentary: hospital experience and meaning at the end of life. Gerontologist. 2002 Oct;42 Spec No. 3:34-39.

- Pantilat SZ. End-of-life care for the hospitalized patient. Med Clin North Am. 2002 Jul;86(4):749-770.

- Tulsky JA. Beyond advance directives: importance of communication skills at the end of life. JAMA. 2005 Jul 20;294(3):359-365.

- Heyland DK, Dodek P, Rocker G, et al. What matters most in end-of-life care: perceptions of seriously ill patients and their family members. CMAJ. 2006 Feb 28;174(5):627-633.

- Barbato M. Caring for the dying: the doctor as healer. MJAust. 2003 May 19;178(10):508-509.

- Fallowfield LJ, Jenkins VA, Beveridge HA. Truth may hurt but deceit hurts more: communication in palliative care. Palliat Med. 2002 Jul;16(4):297-303.

- Fins JJ, Miller FG, Acres CA, et al. End-of-life decision-making in the hospital: current practice and future prospects. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1999 Jan;17(1):6-15.

- Kalish RA. Death, grief and caring relationships. Belmont, California: Brooks/Cole; 1985.

- Lynn J, Schuster JL, Kabcenell A. Improving Care for the End of Life: A Sourcebook for Health Care Managers and Clinicians. New York: Oxford University Press; 2000.

- Lamont EB. A demographic and prognostic approach to defining the end of life. J Palliat Med. 2005;8 Suppl 1:S12-21.

- Christakis NA. Death Foretold: Prophecy and Prognosis in Medical Care. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2001.

- Christakis NA, Lamont EB. Extent and determinants of error in doctors' prognoses in terminally ill patients: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2000 Feb;320(7233):469-472.

- Lamont EB, Christakis NA. Prognostic disclosure to patients with cancer near the end of life. Ann Intern Med. 2001 Jun 19; 134 (12):1096-1105.

- Lamont EB, Siegler M. Paradoxes in cancer patients' advance care planning. J Palliat Med. 2000 Spring;3(1):27-35.

- Fried TR, Byers AL, Gallo WT, et al. Prospective study of health status preferences and changes in preferences over time in older adults. Arch Intern Med. 2006 Apr 24;166(8):890-895.

- McPhee SJ, Rabow MW, Pantilat SZ, et al. Finding our way--perspectives on care at the close of life. JAMA. 2000 Nov 15;284(19):2512-2513.

- Solie D. How to Say It to Seniors: Closing the Communication Gap with Our Elders. New York: Prentice Hall Press; 2004.

- Jennings B, Kaebnick GE, Murray TH. Improving End of Life Care: Why Has It Been So Difficult? Hastings Center Special Report. 2005;35.

They’ve already been in the hospital three or four times, and now they’re back,” says Howard Epstein, MD, an internal medicine-trained hospitalist and the medical director of the palliative care program at Regions Hospital, St. Paul, Minn., describing patients who have acute exacerbations of their life-threatening chronic illnesses. “It’s a challenge we face all the time.”

Hospitalists spend a good deal of their time caring for dying patients, and data show that, by many accounts, they do it well.1 But just how near these patients are to death is often uncertain, especially for patients with diagnoses such as advanced heart and lung failure. Despite their slow decline, during any episode in which they are hospitalized, they may indeed die.

“As hospitalists, we encounter these situations regularly, maybe even daily,” wrote Steve Pantilat, MD, SHM past president, in his column in The Hospitalist (July/August 2005, p. 4): “We are the physicians who care for the seriously ill and the dying. The question is not whether we will take care of these patients; rather, when we do, will we be ready and able?”

End of life and palliative care are areas that hospitalists consider important but feel their training is generally inadequate.2 The conversations with patients and families can be challenging and take time, yet the time is worth the investment and they are a critical part of quality care. “We can learn how to conduct these discussions better,” wrote Dr. Pantilat, “and can practice phrases that will help them go more smoothly.”1,3-14 (See “Practice Phrases,” p. 34.)

Is there a difference in the way hospitalists treat those acute exacerbations if they come from or are attempting to return to their homes in the community or in long-term care? Not really, says Dr. Epstein. The exceptions may be in determining what kind of assistance a patient is getting or not getting outside the hospital (e.g., they’ll return home to a “supercaregiver spouse” versus returning to an assisted or skilled nursing facility). A patient in long-term care usually has multiple comorbidities, or their functional state has declined to the point where they need more assistance, palliative care only, or referral to hospice.

When a patient who has chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) comes in with an acute exacerbation, he says, it’s a good example of when you need to ask those clarifying questions. “If they’re deteriorating and you can paint that broad picture and help them to see that and that they’re going toward some inexorable decline,” says Dr. Epstein, “then they might make different decisions with that information.”

What’s Good in a Good Death?

Phrases such as “good death” and “dying with dignity” bear some interpretation, says Eva Chittenden, MD, a hospitalist with the University of California at San Francisco and a faculty member of its Palliative Care Leadership Center. Most palliative care experts might further define this to mean dying with appropriate respect for who that person is or who that person has been up until this point. A good death, she says, might better be referred to as a death that is “as good as possible.

“People say they want to die at home, but on the other hand, they also want to live forever,” says Dr. Chittenden. The reality is that most people die in acute-care hospitals while receiving invasive therapies.5-6,15 “We want a peaceful death, we want a pain-free death, we want a death where we’re surrounded by our families,” she says, “but at the same time we want to delay that forever. And those two things come into extreme conflict.7,9

“If you have cancer, maybe you don’t want to talk with your oncologist about death and dying because you want them to save your life. So you don’t even want to go there. And then you’re admitted to the hospital you’re told, ‘You’re extremely sick; you have pneumonia, but if we intubate you, we might be able to turn this situation around versus, if we don’t intubate you, you will surely die.’ And people don’t want to make that decision, because they’re not ready to die, even if ideally they’d want to have that good death,” says Dr. Chittenden, noting that not all providers have come to terms with how to use the available medical technology, when to stop using it, and how to talk about prognosis.

Talking about Prognosis

“In no case of serious illness … is predicting the future straightforward or meaningless,” writes Nicholas Christakis, in Death Foretold: Prophecy and Prognosis in Medical Care.16 “Part of the problem is that even formulating, much less communicating, a prediction about death is unpleasant, so physicians are inclined to refrain from it. But when they are able to formulate a prediction and fail to do so, the quality of care that patients receive may suffer.”

According to Dr. Epstein, you have to practice the conversations. “It’s a skill set, just like doing a bedside procedure … something that you have to do over and over and get comfortable doing,” he explains. “And it shocks people out of their seats when they actually hear the ‘D word.’ ” But part of meeting your responsibility to patients and their families requires speaking the truth.

Dr. Epstein says there are numerous resources available to help hospitalists overcome their discomfort and fears about being incorrect about how long the patient has to live. “I think it is OK to also say, ‘Look, I’m not God and I don't have a crystal ball, but I have seen lots of people in your situation and having watched them go through this point in their life, this is my expert opinion … ,’ ” he advises.

This involves telling the patient, “These are your chances of making a full recovery to the point where you might appreciate the quality of life you would have.” You don’t have to give numbers; you can use words such as good, bad, or poor.

For those with advanced systemic failure, you might discuss prognoses in words that patients can better understand by making a comparison to someone has a cancer diagnosis. For instance, “I’ll say, ‘Your chances for living for a year are about as good as someone living with metastatic lung cancer,’ ” says Dr. Epstein. “I think that’s something that patients grasp a lot easier.”

In addition to the fear of being incorrect in prognosticating, physicians often don’t want their patients to lose hope. “Whereas in truth people are already thinking about these things, and there are studies that show people want their doctors to bring it up,” says Dr. Chittenden.7

A number of these studies were conducted by Dr. Christakis and Elizabeth Lamont, MD, a medical oncologist now practicing at Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center and assistant professor of medicine and health care policy at Harvard Medical School.15,17-19 Their findings have shown that doctors’ inaccuracies in their prognoses for terminally ill patients are systematically optimistic and that this may adversely affect the quality of care given to patients near the end of life.17

In their study of 326 patients in five hospices in Chicago, Drs. Christakis and Lamont showed that even if patients with cancer requested survival estimates, doctors would provide a frank estimate only 37% of the time and would provide no estimate, a conscious overestimate, or a conscious underestimate most of the time (63%).18 This, they concluded, may contribute to the observed disparities between physicians’ and patients’ estimates of survival.

Dr. Lamont’s interest in prognosis at end of life and the subject of advanced care planning arose from her experiences as a resident when she was cross-covering the oncology services. “I would be called to see [for example] a 35-year-old woman with widely metastatic breast cancer including brain metastases who was clearly at the end of life,” she says. “She became acutely short of breath, and my concern was that she was having a pulmonary embolism. … I was trying to decide whether to send her to the ICU. I was trying to inform her about the risks of anticoagulation … and I asked, ‘Have you talked about whether or not you’d want to go to the intensive care unit, whether or not you’d want your heart restarted, whether or not you’d want to be put on a ventilator if you couldn’t be breathe on your own; have you talked about these kinds of things with your oncologist?’ [Her answer was,] ‘Oh, no!’ ” Dr. Lamont figured that if she would have these conversations anyway, it would make more sense to have them as part of the admission history and physical. The study she subsequently designed and conducted involved 111 newly admitted patients with cancer whom she interviewed about (among other things) whether they had advanced care preferences (ACP) and whether they had discussed advanced directives with their medical oncologists. Only 9% of patients said that they had advanced directives, although 69% of patients had discussed their ACP with someone else (such as family).19 (See “ACP among Hospitalized Cancer Patients,” below.) However, 58% of patients approved of the option of being offered a discussion about advanced care planning with medical house staff as part of the admission history.

In other words, for the population of patients at high risk for dying during their current hospitalization, more than half would be open to discussing ACP with those whom they do not know well—such as hospitalists.

Advance Care Planning

A study just published in Archives of Internal Medicine suggests that elderly people who suffer from terminal illnesses become increasingly more willing to accept a life-preserving treatment, resulting in further physical disability or more pain if they were already diminished in those domains.20 Terri Fried, MD, an associate professor of internal medicine at Yale, and her colleagues studied 226 older men and women with advanced cancer, congestive heart failure (CHF), or COPD. In the course of in-home interviews conducted over two years, the investigators explored whether the participants would accept life-prolonging treatment if it resulted in one of four diminished health states: mild physical disability, severe physical disability, mental disability, or moderately severe daily pain.

Results showed that the likelihood of a treatment resulting in mild or severe functional disability rating as acceptable increased with each month of participation in the study. More than half of the patients had prepared living wills, and these individuals were more likely to prefer death to disability, but preferences could also change. These findings suggest that even though providers, patients, and families may have already had conversations about advance care planning, a patient’s change in health status might herald the need for a new conversation.

Dr. Lamont says there are two major areas in which hospitalists can politically advocate for changes that could facilitate better advance care planning. The first is to adopt the model proposed in her study, whereby patients are queried regarding advanced directives as part of the admission history.19 Patients for whom this could be added as a new data field would include, for example, those with advanced cancer, metastatic solid tumors, relapsed leukemia, relapsed lymphoma, or with acute exacerbations of illnesses such as CHF or COPD. The second area where hospitalists could advocate for change is national healthcare policy. Like a number of others, Dr. Lamont believes CMS should begin reimbursing for high-quality end-of-life care discussions, the measures of which would be determined at both local and national levels.

Communication Training

“The more hospital medicine training gets incorporated into internal medicine residency,” says Dr. Epstein, “the greater the opportunity to train new hospitalists to have these difficult conversations: how to have a family meeting, to identify the issues, to see if there are any ethical issues involved, any legal issues, and how to negotiate a reasonable plan of care based on the patient’s goals.”2,8,21

In addition to helping with control of physical symptoms, such as pain and nausea control, physicians facilitate decision-making. “We try to address a lot of the existential and reconciliation and legacy issues,” says Dr. Chittenden. Because of the number of situations in which the patient is a woman or man in their 40s or 50s who have young children, she says, “we help the parents come to terms with this and get our child-life specialist involved to help the parents think about how to talk with the kids.”

Because of the growth of the palliative care movement, the training is beginning to improve. “The LCME [Liaison Committee on Medical Education], the licensure group for medical schools, mandates that there be some end-of-life care exposure,” says Dr. Chittenden. “And the ACGME [Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education], which licenses the residency programs, strongly suggests that there be opportunities to learn about this. … Slowly but surely we are realizing this needs to happen, but we are far from doing it well.”

What would be ideal? A two-week rotation for residents in a palliative care service? “That would be wonderful,” says Dr. Epstein. “As more palliative care services pop up across the country, the chance of that happening would increase. … And even if you’re not in palliative care and you’re a hospitalist and you do these kinds of things well, the residents should be watching you have those kinds of conversations.”

Explaining that he is paraphrasing Mark Leenay, MD, the former program director at Fairview-University, Minnesota, and the physician who spearheaded the development of a clinical team that comprehensively addresses the multiple aspects of suffering from life-threatening illness, Dr. Epstein says: “I can train anybody to do symptom management in hospice, but how to walk into a room and understand … and negotiate the family dynamics and the patient’s plan of care … to communicate on different levels with different people with … their own agendas, and all the pieces of information … [and different interpretations] … to take it all in and digest it for that meeting and spit it out in a way [in which] everyone can relate and come to some sort of consensus, hopefully, at the end of the meeting? That’s the art. And that takes practice.”

Conclusion

Patients with life-threatening chronic illnesses are often admitted to the hospital multiple times in the course of the period that could be considered the end of life. Important nonmedical issues for hospitalists to address at each new admission include communication regarding prognosis and advance care planning, and addressing existential issues greatly contributes to the quality of care. TH

Resources

- The Hastings Center is involved in bioethics and other issues surrounding end-of-life care (www.thehastingscenter.org/default.asp). The Special Report listed in “References” is downloadable from their Web site.23

- Education in Palliative and End-of-Life Care (EPEC) curriculum (www.epec.net).

- The American Board of Hospice and Palliative Medicine (www.abhpm.org).

- The American Association of Hospice and Palliative Medicine (www.aahpm.org).

- Harvard’s Center for Palliative Care offers courses that emphasize teaching (www.hms.harvard.edu/cdi/pallcare/).

- The Center to Advance Palliative Care (CAPC), Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, serves as a resource for hospital-based palliative care program development. CAPC supports six regional Palliative Care Leadership Centers (www.capc.org).

The following Web sites include models for advance directives.

- Five Wishes: www.agingwithdignity.org

- Individual decisions: www.newgrangepress.com

- Respecting choices at end of life: www.gundersenlutheran.com/eolprograms

- Physician orders for life-sustaining treatment: www.polst.org

References

- Auerbach AD, Pantilat SZ. End-of-Life care in a voluntary hospitalist model: effects on communication, processes of care, and patient symptoms. Am J Med. 2004 May 15;116(10):669-675.

- Plauth WH, Pantilat SZ, Wachter RM, et al. Hospitalists' perceptions of their residency training needs: result of a national survey. Am J Med. 2001;111(3):247-254.

- Lo B, Quill TE, Tulsky J. Discussing palliative care with patients. ACP--ASIM End-of-Life Care Consensus Panel. American College of Physicians--American Society of Internal Medicine. Ann Intern Med. 1999 May 4;130(9):744-749.

- Quill TE. Initiating end-of-life discussions with seriously ill patients: addressing the "elephant in the room." JAMA. 2000 Nov 15;284(19):2502-2507.

- Kaufman SR. And a Time to Die: How American Hospitals Shape the End of Life. New York: Scribner; 2005.

- Kaufman SR. A commentary: hospital experience and meaning at the end of life. Gerontologist. 2002 Oct;42 Spec No. 3:34-39.

- Pantilat SZ. End-of-life care for the hospitalized patient. Med Clin North Am. 2002 Jul;86(4):749-770.

- Tulsky JA. Beyond advance directives: importance of communication skills at the end of life. JAMA. 2005 Jul 20;294(3):359-365.

- Heyland DK, Dodek P, Rocker G, et al. What matters most in end-of-life care: perceptions of seriously ill patients and their family members. CMAJ. 2006 Feb 28;174(5):627-633.

- Barbato M. Caring for the dying: the doctor as healer. MJAust. 2003 May 19;178(10):508-509.

- Fallowfield LJ, Jenkins VA, Beveridge HA. Truth may hurt but deceit hurts more: communication in palliative care. Palliat Med. 2002 Jul;16(4):297-303.

- Fins JJ, Miller FG, Acres CA, et al. End-of-life decision-making in the hospital: current practice and future prospects. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1999 Jan;17(1):6-15.

- Kalish RA. Death, grief and caring relationships. Belmont, California: Brooks/Cole; 1985.

- Lynn J, Schuster JL, Kabcenell A. Improving Care for the End of Life: A Sourcebook for Health Care Managers and Clinicians. New York: Oxford University Press; 2000.

- Lamont EB. A demographic and prognostic approach to defining the end of life. J Palliat Med. 2005;8 Suppl 1:S12-21.

- Christakis NA. Death Foretold: Prophecy and Prognosis in Medical Care. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2001.

- Christakis NA, Lamont EB. Extent and determinants of error in doctors' prognoses in terminally ill patients: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2000 Feb;320(7233):469-472.

- Lamont EB, Christakis NA. Prognostic disclosure to patients with cancer near the end of life. Ann Intern Med. 2001 Jun 19; 134 (12):1096-1105.

- Lamont EB, Siegler M. Paradoxes in cancer patients' advance care planning. J Palliat Med. 2000 Spring;3(1):27-35.

- Fried TR, Byers AL, Gallo WT, et al. Prospective study of health status preferences and changes in preferences over time in older adults. Arch Intern Med. 2006 Apr 24;166(8):890-895.

- McPhee SJ, Rabow MW, Pantilat SZ, et al. Finding our way--perspectives on care at the close of life. JAMA. 2000 Nov 15;284(19):2512-2513.

- Solie D. How to Say It to Seniors: Closing the Communication Gap with Our Elders. New York: Prentice Hall Press; 2004.

- Jennings B, Kaebnick GE, Murray TH. Improving End of Life Care: Why Has It Been So Difficult? Hastings Center Special Report. 2005;35.

They’ve already been in the hospital three or four times, and now they’re back,” says Howard Epstein, MD, an internal medicine-trained hospitalist and the medical director of the palliative care program at Regions Hospital, St. Paul, Minn., describing patients who have acute exacerbations of their life-threatening chronic illnesses. “It’s a challenge we face all the time.”

Hospitalists spend a good deal of their time caring for dying patients, and data show that, by many accounts, they do it well.1 But just how near these patients are to death is often uncertain, especially for patients with diagnoses such as advanced heart and lung failure. Despite their slow decline, during any episode in which they are hospitalized, they may indeed die.

“As hospitalists, we encounter these situations regularly, maybe even daily,” wrote Steve Pantilat, MD, SHM past president, in his column in The Hospitalist (July/August 2005, p. 4): “We are the physicians who care for the seriously ill and the dying. The question is not whether we will take care of these patients; rather, when we do, will we be ready and able?”

End of life and palliative care are areas that hospitalists consider important but feel their training is generally inadequate.2 The conversations with patients and families can be challenging and take time, yet the time is worth the investment and they are a critical part of quality care. “We can learn how to conduct these discussions better,” wrote Dr. Pantilat, “and can practice phrases that will help them go more smoothly.”1,3-14 (See “Practice Phrases,” p. 34.)

Is there a difference in the way hospitalists treat those acute exacerbations if they come from or are attempting to return to their homes in the community or in long-term care? Not really, says Dr. Epstein. The exceptions may be in determining what kind of assistance a patient is getting or not getting outside the hospital (e.g., they’ll return home to a “supercaregiver spouse” versus returning to an assisted or skilled nursing facility). A patient in long-term care usually has multiple comorbidities, or their functional state has declined to the point where they need more assistance, palliative care only, or referral to hospice.

When a patient who has chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) comes in with an acute exacerbation, he says, it’s a good example of when you need to ask those clarifying questions. “If they’re deteriorating and you can paint that broad picture and help them to see that and that they’re going toward some inexorable decline,” says Dr. Epstein, “then they might make different decisions with that information.”

What’s Good in a Good Death?

Phrases such as “good death” and “dying with dignity” bear some interpretation, says Eva Chittenden, MD, a hospitalist with the University of California at San Francisco and a faculty member of its Palliative Care Leadership Center. Most palliative care experts might further define this to mean dying with appropriate respect for who that person is or who that person has been up until this point. A good death, she says, might better be referred to as a death that is “as good as possible.

“People say they want to die at home, but on the other hand, they also want to live forever,” says Dr. Chittenden. The reality is that most people die in acute-care hospitals while receiving invasive therapies.5-6,15 “We want a peaceful death, we want a pain-free death, we want a death where we’re surrounded by our families,” she says, “but at the same time we want to delay that forever. And those two things come into extreme conflict.7,9

“If you have cancer, maybe you don’t want to talk with your oncologist about death and dying because you want them to save your life. So you don’t even want to go there. And then you’re admitted to the hospital you’re told, ‘You’re extremely sick; you have pneumonia, but if we intubate you, we might be able to turn this situation around versus, if we don’t intubate you, you will surely die.’ And people don’t want to make that decision, because they’re not ready to die, even if ideally they’d want to have that good death,” says Dr. Chittenden, noting that not all providers have come to terms with how to use the available medical technology, when to stop using it, and how to talk about prognosis.

Talking about Prognosis

“In no case of serious illness … is predicting the future straightforward or meaningless,” writes Nicholas Christakis, in Death Foretold: Prophecy and Prognosis in Medical Care.16 “Part of the problem is that even formulating, much less communicating, a prediction about death is unpleasant, so physicians are inclined to refrain from it. But when they are able to formulate a prediction and fail to do so, the quality of care that patients receive may suffer.”

According to Dr. Epstein, you have to practice the conversations. “It’s a skill set, just like doing a bedside procedure … something that you have to do over and over and get comfortable doing,” he explains. “And it shocks people out of their seats when they actually hear the ‘D word.’ ” But part of meeting your responsibility to patients and their families requires speaking the truth.

Dr. Epstein says there are numerous resources available to help hospitalists overcome their discomfort and fears about being incorrect about how long the patient has to live. “I think it is OK to also say, ‘Look, I’m not God and I don't have a crystal ball, but I have seen lots of people in your situation and having watched them go through this point in their life, this is my expert opinion … ,’ ” he advises.

This involves telling the patient, “These are your chances of making a full recovery to the point where you might appreciate the quality of life you would have.” You don’t have to give numbers; you can use words such as good, bad, or poor.

For those with advanced systemic failure, you might discuss prognoses in words that patients can better understand by making a comparison to someone has a cancer diagnosis. For instance, “I’ll say, ‘Your chances for living for a year are about as good as someone living with metastatic lung cancer,’ ” says Dr. Epstein. “I think that’s something that patients grasp a lot easier.”

In addition to the fear of being incorrect in prognosticating, physicians often don’t want their patients to lose hope. “Whereas in truth people are already thinking about these things, and there are studies that show people want their doctors to bring it up,” says Dr. Chittenden.7

A number of these studies were conducted by Dr. Christakis and Elizabeth Lamont, MD, a medical oncologist now practicing at Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center and assistant professor of medicine and health care policy at Harvard Medical School.15,17-19 Their findings have shown that doctors’ inaccuracies in their prognoses for terminally ill patients are systematically optimistic and that this may adversely affect the quality of care given to patients near the end of life.17

In their study of 326 patients in five hospices in Chicago, Drs. Christakis and Lamont showed that even if patients with cancer requested survival estimates, doctors would provide a frank estimate only 37% of the time and would provide no estimate, a conscious overestimate, or a conscious underestimate most of the time (63%).18 This, they concluded, may contribute to the observed disparities between physicians’ and patients’ estimates of survival.

Dr. Lamont’s interest in prognosis at end of life and the subject of advanced care planning arose from her experiences as a resident when she was cross-covering the oncology services. “I would be called to see [for example] a 35-year-old woman with widely metastatic breast cancer including brain metastases who was clearly at the end of life,” she says. “She became acutely short of breath, and my concern was that she was having a pulmonary embolism. … I was trying to decide whether to send her to the ICU. I was trying to inform her about the risks of anticoagulation … and I asked, ‘Have you talked about whether or not you’d want to go to the intensive care unit, whether or not you’d want your heart restarted, whether or not you’d want to be put on a ventilator if you couldn’t be breathe on your own; have you talked about these kinds of things with your oncologist?’ [Her answer was,] ‘Oh, no!’ ” Dr. Lamont figured that if she would have these conversations anyway, it would make more sense to have them as part of the admission history and physical. The study she subsequently designed and conducted involved 111 newly admitted patients with cancer whom she interviewed about (among other things) whether they had advanced care preferences (ACP) and whether they had discussed advanced directives with their medical oncologists. Only 9% of patients said that they had advanced directives, although 69% of patients had discussed their ACP with someone else (such as family).19 (See “ACP among Hospitalized Cancer Patients,” below.) However, 58% of patients approved of the option of being offered a discussion about advanced care planning with medical house staff as part of the admission history.

In other words, for the population of patients at high risk for dying during their current hospitalization, more than half would be open to discussing ACP with those whom they do not know well—such as hospitalists.

Advance Care Planning

A study just published in Archives of Internal Medicine suggests that elderly people who suffer from terminal illnesses become increasingly more willing to accept a life-preserving treatment, resulting in further physical disability or more pain if they were already diminished in those domains.20 Terri Fried, MD, an associate professor of internal medicine at Yale, and her colleagues studied 226 older men and women with advanced cancer, congestive heart failure (CHF), or COPD. In the course of in-home interviews conducted over two years, the investigators explored whether the participants would accept life-prolonging treatment if it resulted in one of four diminished health states: mild physical disability, severe physical disability, mental disability, or moderately severe daily pain.

Results showed that the likelihood of a treatment resulting in mild or severe functional disability rating as acceptable increased with each month of participation in the study. More than half of the patients had prepared living wills, and these individuals were more likely to prefer death to disability, but preferences could also change. These findings suggest that even though providers, patients, and families may have already had conversations about advance care planning, a patient’s change in health status might herald the need for a new conversation.

Dr. Lamont says there are two major areas in which hospitalists can politically advocate for changes that could facilitate better advance care planning. The first is to adopt the model proposed in her study, whereby patients are queried regarding advanced directives as part of the admission history.19 Patients for whom this could be added as a new data field would include, for example, those with advanced cancer, metastatic solid tumors, relapsed leukemia, relapsed lymphoma, or with acute exacerbations of illnesses such as CHF or COPD. The second area where hospitalists could advocate for change is national healthcare policy. Like a number of others, Dr. Lamont believes CMS should begin reimbursing for high-quality end-of-life care discussions, the measures of which would be determined at both local and national levels.

Communication Training

“The more hospital medicine training gets incorporated into internal medicine residency,” says Dr. Epstein, “the greater the opportunity to train new hospitalists to have these difficult conversations: how to have a family meeting, to identify the issues, to see if there are any ethical issues involved, any legal issues, and how to negotiate a reasonable plan of care based on the patient’s goals.”2,8,21

In addition to helping with control of physical symptoms, such as pain and nausea control, physicians facilitate decision-making. “We try to address a lot of the existential and reconciliation and legacy issues,” says Dr. Chittenden. Because of the number of situations in which the patient is a woman or man in their 40s or 50s who have young children, she says, “we help the parents come to terms with this and get our child-life specialist involved to help the parents think about how to talk with the kids.”

Because of the growth of the palliative care movement, the training is beginning to improve. “The LCME [Liaison Committee on Medical Education], the licensure group for medical schools, mandates that there be some end-of-life care exposure,” says Dr. Chittenden. “And the ACGME [Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education], which licenses the residency programs, strongly suggests that there be opportunities to learn about this. … Slowly but surely we are realizing this needs to happen, but we are far from doing it well.”

What would be ideal? A two-week rotation for residents in a palliative care service? “That would be wonderful,” says Dr. Epstein. “As more palliative care services pop up across the country, the chance of that happening would increase. … And even if you’re not in palliative care and you’re a hospitalist and you do these kinds of things well, the residents should be watching you have those kinds of conversations.”

Explaining that he is paraphrasing Mark Leenay, MD, the former program director at Fairview-University, Minnesota, and the physician who spearheaded the development of a clinical team that comprehensively addresses the multiple aspects of suffering from life-threatening illness, Dr. Epstein says: “I can train anybody to do symptom management in hospice, but how to walk into a room and understand … and negotiate the family dynamics and the patient’s plan of care … to communicate on different levels with different people with … their own agendas, and all the pieces of information … [and different interpretations] … to take it all in and digest it for that meeting and spit it out in a way [in which] everyone can relate and come to some sort of consensus, hopefully, at the end of the meeting? That’s the art. And that takes practice.”

Conclusion

Patients with life-threatening chronic illnesses are often admitted to the hospital multiple times in the course of the period that could be considered the end of life. Important nonmedical issues for hospitalists to address at each new admission include communication regarding prognosis and advance care planning, and addressing existential issues greatly contributes to the quality of care. TH

Resources

- The Hastings Center is involved in bioethics and other issues surrounding end-of-life care (www.thehastingscenter.org/default.asp). The Special Report listed in “References” is downloadable from their Web site.23

- Education in Palliative and End-of-Life Care (EPEC) curriculum (www.epec.net).

- The American Board of Hospice and Palliative Medicine (www.abhpm.org).

- The American Association of Hospice and Palliative Medicine (www.aahpm.org).

- Harvard’s Center for Palliative Care offers courses that emphasize teaching (www.hms.harvard.edu/cdi/pallcare/).

- The Center to Advance Palliative Care (CAPC), Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, serves as a resource for hospital-based palliative care program development. CAPC supports six regional Palliative Care Leadership Centers (www.capc.org).

The following Web sites include models for advance directives.

- Five Wishes: www.agingwithdignity.org

- Individual decisions: www.newgrangepress.com

- Respecting choices at end of life: www.gundersenlutheran.com/eolprograms

- Physician orders for life-sustaining treatment: www.polst.org

References

- Auerbach AD, Pantilat SZ. End-of-Life care in a voluntary hospitalist model: effects on communication, processes of care, and patient symptoms. Am J Med. 2004 May 15;116(10):669-675.

- Plauth WH, Pantilat SZ, Wachter RM, et al. Hospitalists' perceptions of their residency training needs: result of a national survey. Am J Med. 2001;111(3):247-254.

- Lo B, Quill TE, Tulsky J. Discussing palliative care with patients. ACP--ASIM End-of-Life Care Consensus Panel. American College of Physicians--American Society of Internal Medicine. Ann Intern Med. 1999 May 4;130(9):744-749.

- Quill TE. Initiating end-of-life discussions with seriously ill patients: addressing the "elephant in the room." JAMA. 2000 Nov 15;284(19):2502-2507.

- Kaufman SR. And a Time to Die: How American Hospitals Shape the End of Life. New York: Scribner; 2005.

- Kaufman SR. A commentary: hospital experience and meaning at the end of life. Gerontologist. 2002 Oct;42 Spec No. 3:34-39.

- Pantilat SZ. End-of-life care for the hospitalized patient. Med Clin North Am. 2002 Jul;86(4):749-770.

- Tulsky JA. Beyond advance directives: importance of communication skills at the end of life. JAMA. 2005 Jul 20;294(3):359-365.

- Heyland DK, Dodek P, Rocker G, et al. What matters most in end-of-life care: perceptions of seriously ill patients and their family members. CMAJ. 2006 Feb 28;174(5):627-633.

- Barbato M. Caring for the dying: the doctor as healer. MJAust. 2003 May 19;178(10):508-509.

- Fallowfield LJ, Jenkins VA, Beveridge HA. Truth may hurt but deceit hurts more: communication in palliative care. Palliat Med. 2002 Jul;16(4):297-303.

- Fins JJ, Miller FG, Acres CA, et al. End-of-life decision-making in the hospital: current practice and future prospects. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1999 Jan;17(1):6-15.

- Kalish RA. Death, grief and caring relationships. Belmont, California: Brooks/Cole; 1985.

- Lynn J, Schuster JL, Kabcenell A. Improving Care for the End of Life: A Sourcebook for Health Care Managers and Clinicians. New York: Oxford University Press; 2000.

- Lamont EB. A demographic and prognostic approach to defining the end of life. J Palliat Med. 2005;8 Suppl 1:S12-21.

- Christakis NA. Death Foretold: Prophecy and Prognosis in Medical Care. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2001.

- Christakis NA, Lamont EB. Extent and determinants of error in doctors' prognoses in terminally ill patients: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2000 Feb;320(7233):469-472.

- Lamont EB, Christakis NA. Prognostic disclosure to patients with cancer near the end of life. Ann Intern Med. 2001 Jun 19; 134 (12):1096-1105.

- Lamont EB, Siegler M. Paradoxes in cancer patients' advance care planning. J Palliat Med. 2000 Spring;3(1):27-35.

- Fried TR, Byers AL, Gallo WT, et al. Prospective study of health status preferences and changes in preferences over time in older adults. Arch Intern Med. 2006 Apr 24;166(8):890-895.

- McPhee SJ, Rabow MW, Pantilat SZ, et al. Finding our way--perspectives on care at the close of life. JAMA. 2000 Nov 15;284(19):2512-2513.

- Solie D. How to Say It to Seniors: Closing the Communication Gap with Our Elders. New York: Prentice Hall Press; 2004.

- Jennings B, Kaebnick GE, Murray TH. Improving End of Life Care: Why Has It Been So Difficult? Hastings Center Special Report. 2005;35.