User login

Vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia (VAIN) is a condition that frequently poses therapeutic dilemmas for gynecologists. VAIN represents dysplastic changes to the epithelium of the vaginal mucosa, and like cervical neoplasia, the extent of disease is characterized as levels I, II, or III dependent upon the depth of involvement in the epithelial layer by dysplastic cells. While VAIN itself typically is asymptomatic and not a harmful condition, it carries a 12% risk of progression to invasive vaginal carcinoma, so accurate identification, thorough treatment, and ongoing surveillance are essential.1

VAIN is associated with high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, tobacco use, and prior cervical dysplasia. Of women with VAIN, 65% have undergone a prior hysterectomy for cervical dysplasia, which emphasizes the nondefinitive nature of such an intervention.2 These women should be very closely followed for at least 20 years with vaginal cytologic and/or HPV surveillance. High-risk HPV infection is present in 85% of women with VAIN, and the presence of high-risk HPV is a predictor for recurrent VAIN. Recurrent and persistent VAIN also is more common in postmenopausal women and those with multifocal disease.

The most common location for VAIN is at the upper third of the vagina (including the vaginal cuff). It commonly arises within the vaginal fornices, which may be difficult to fully visualize because of their puckered appearance, redundant vaginal tissues, and extensive vaginal rogation.

A diagnosis of VAIN is typically obtained from vaginal cytology which reveals atypical or dysplastic cells. Such a result should prompt the physician to perform vaginal colposcopy and directed biopsies. Comprehensive visualization of the vaginal cuff can be limited in cases where the vaginal fornices are tethered, deeply puckered, or when there is significant mucosal rogation.

The application of 4% acetic acid or Lugol’s iodine are techniques that can enhance the detection of dysplastic vaginal mucosa. Lugol’s iodine selectively stains normal, glycogenated cells, and spares dysplastic glycogen-free cells. The sharp contrast between the brown iodine-stained tissues and the white dysplastic tissues aids in detection of dysplastic areas.

If colposcopic biopsy reveals low grade dysplasia (VAIN I) it does not require intervention, and has a very low rate of conversion to invasive vaginal carcinoma. However moderate- and high-grade vaginal dysplastic lesions should be treated because of the potential for malignant transformation.

Options for treatment of VAIN include topical, ablative, and excisional procedures. Observation also is an option but should be reserved for patients who are closely monitored with repeated colposcopic examinations, and probably should best be reserved for patients with VAIN I or II lesions.

Excisional procedures

The most common excisional procedure employed for VAIN is upper vaginectomy. In this procedure, the surgeon grasps and tents up the vaginal mucosa, incises the mucosa without penetrating the subepithelial tissue layers such as bladder and rectum. The vaginal mucosa then is carefully separated from the underlying endopelvic fascial plane. The specimen should be oriented, ideally on a cork board, with pins or sutures to ascribe margins and borders. Excision is best utilized for women with unifocal disease, or those who fail or do not tolerate ablative or topical interventions.

The most significant risks of excision include the potential for damage to underlying pelvic visceral structures, which is particularly concerning in postmenopausal women with thin vaginal epithelium. Vaginectomy is commonly associated with vaginal shortening or narrowing, which can be deleterious for quality of life. Retrospective series have described a 30% incidence of recurrence after vaginectomy, likely secondary to incomplete excision of all affected tissue.3

Ablation

Ablation of dysplastic foci with a carbon dioxide (CO2) laser is a common method for treatment of VAIN. CO2 laser should ablate tissue to a 1.5 mm minimum depth.3 The benefit of using CO2 laser is its ability to treat multifocal disease in situ without an extensive excisional procedure.

It is technically more straightforward than upper vaginectomy with less blood loss and shorter surgical times, and it can be easily accomplished in an outpatient surgical or office setting. However, one of its greatest limitations is the difficulty in visualizing all lesions and therefore adequately treating all sites. The vaginal rogations also make adequate laser ablation challenging because laser only is able to effectively ablate tissue that is oriented perpendicular to the laser beam.

In addition, there is no pathologic confirmation of adequacy of excision or margin status. These features may contribute to the modestly higher rates of recurrence of dysplasia following laser ablation, compared with vaginectomy.3 It also has been associated with more vaginal scarring than vaginectomy, which can have a negative effect on sexual health.

Topical agents

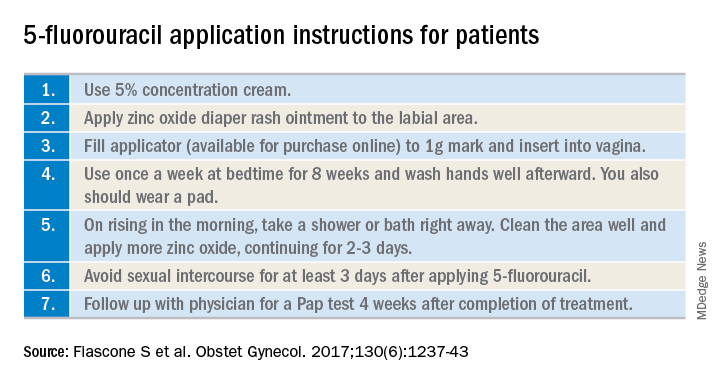

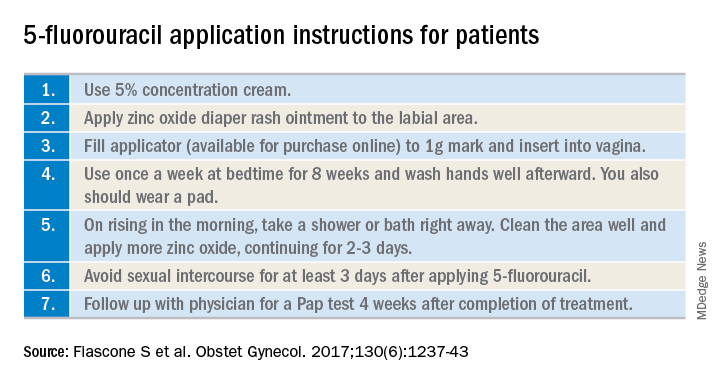

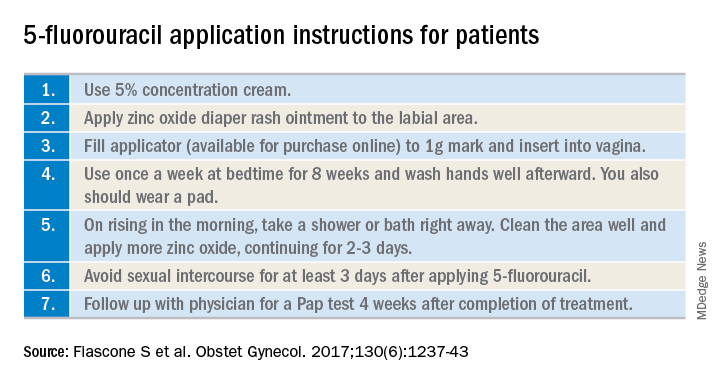

The most commonly utilized topical therapy for VAIN is the antimetabolite chemotherapeutic agent 5-fluorouracil (5FU). A typical schedule for 5FU treatment is to apply vaginally, at night, once a week for 8 weeks.4 Because it can cause extensive irritation to the vulvar and urethral epithelium, patients are recommended to apply barrier creams or ointments before and following the use of 5FU for several days, wash hands thoroughly after application, and to rinse and shower in the morning after rising. Severe irritation occurs in up to 16% of patients, but in general it is very well tolerated.

Its virtue is that it is able to conform and travel to all parts of the vaginal mucosa, including those that are poorly visualized within the fornices or vaginal folds. 5FU does not require a hospitalization or surgical procedure, can be applied by the patient at home, and preserves vaginal length and function. In recent reports, 5FU is associated with the lowest rates of recurrence (10%-30%), compared with excision or ablation, and therefore is a very attractive option for primary therapy.3 However, it requires patients to have a degree of comfort with vaginal application of drug and adherence with perineal care strategies to minimize the likelihood of toxicity.

The immune response modifier, imiquimod, that is commonly used in the treatment of vulvar dysplasia also has been described in the treatment of VAIN. It appears to have high rates of clearance (greater than 75%) and be most effective in the treatment of VAIN I.5 It requires application under colposcopic guidance three times a week for 8 weeks, which is a laborious undertaking for both patient and physician. Like 5FU, imiquimod is associated with vulvar and perineal irritation.

Vaginal estrogens are an alternative topical therapy for moderate- and high-grade VAIN and particularly useful for postmenopausal patients. They have been associated with a high rate (up to 90%) of resolution on follow-up vaginal cytology testing and are not associated with toxicities of the above stated therapies.6 Vaginal estrogen can be used alone or in addition to other therapeutic strategies. For example, it can be added to the nontreatment days of 5FU or postoperatively prescribed following laser or excisional procedures.

Radiation

Intracavitary brachytherapy is a technique in which a radiation source is placed within a cylinder or ovoids and placed within the vagina.7 Typically 45 Gy is delivered to a depth 0.5mm below the vaginal mucosal surface (“point z”). Recurrence occurs is approximately 10%-15% of patients, and toxicities can be severe, including vaginal stenosis and ulceration. This aggressive therapy typically is best reserved for cases that are refractory to other therapies. Following radiation, subsequent treatments are more difficult because of radiation-induced changes to the vaginal mucosa that can affect healing.

Vaginal dysplasia is a relatively common sequelae of high-risk HPV, particularly among women who have had a prior hysterectomy for cervical dysplasia. Because of anatomic changes following hysterectomy, adequate visualization and comprehensive vaginal treatment is difficult. Therefore, surgeons should avoid utilization of hysterectomy as a routine strategy to “cure” dysplasia as it may fail to achieve this cure and make subsequent evaluations and treatments of persistent dysplasia more difficult. Women who have had a hysterectomy for dysplasia should be closely followed for several decades, and they should be counseled that they have a persistent risk for vaginal disease. When VAIN develops, clinicians should consider topical therapies as primary treatment options because they may minimize toxicity and have high rates of enduring response.

Dr. Rossi is an assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She had no relevant conflicts of interest.

References

1. Gynecol Oncol. 2016 Jun;141(3):507-10.

2. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2016 Feb;293(2):415-9.

3. Anticancer Res. 2013 Jan;33(1):29-38.

4. Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Dec;130(6):1237-43.

5. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2017 Nov;218:129-36.

6. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2014 Apr;18(2):115-21.

7. Gynecol Oncol. 2007 Jul;106(1):105-11.

Vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia (VAIN) is a condition that frequently poses therapeutic dilemmas for gynecologists. VAIN represents dysplastic changes to the epithelium of the vaginal mucosa, and like cervical neoplasia, the extent of disease is characterized as levels I, II, or III dependent upon the depth of involvement in the epithelial layer by dysplastic cells. While VAIN itself typically is asymptomatic and not a harmful condition, it carries a 12% risk of progression to invasive vaginal carcinoma, so accurate identification, thorough treatment, and ongoing surveillance are essential.1

VAIN is associated with high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, tobacco use, and prior cervical dysplasia. Of women with VAIN, 65% have undergone a prior hysterectomy for cervical dysplasia, which emphasizes the nondefinitive nature of such an intervention.2 These women should be very closely followed for at least 20 years with vaginal cytologic and/or HPV surveillance. High-risk HPV infection is present in 85% of women with VAIN, and the presence of high-risk HPV is a predictor for recurrent VAIN. Recurrent and persistent VAIN also is more common in postmenopausal women and those with multifocal disease.

The most common location for VAIN is at the upper third of the vagina (including the vaginal cuff). It commonly arises within the vaginal fornices, which may be difficult to fully visualize because of their puckered appearance, redundant vaginal tissues, and extensive vaginal rogation.

A diagnosis of VAIN is typically obtained from vaginal cytology which reveals atypical or dysplastic cells. Such a result should prompt the physician to perform vaginal colposcopy and directed biopsies. Comprehensive visualization of the vaginal cuff can be limited in cases where the vaginal fornices are tethered, deeply puckered, or when there is significant mucosal rogation.

The application of 4% acetic acid or Lugol’s iodine are techniques that can enhance the detection of dysplastic vaginal mucosa. Lugol’s iodine selectively stains normal, glycogenated cells, and spares dysplastic glycogen-free cells. The sharp contrast between the brown iodine-stained tissues and the white dysplastic tissues aids in detection of dysplastic areas.

If colposcopic biopsy reveals low grade dysplasia (VAIN I) it does not require intervention, and has a very low rate of conversion to invasive vaginal carcinoma. However moderate- and high-grade vaginal dysplastic lesions should be treated because of the potential for malignant transformation.

Options for treatment of VAIN include topical, ablative, and excisional procedures. Observation also is an option but should be reserved for patients who are closely monitored with repeated colposcopic examinations, and probably should best be reserved for patients with VAIN I or II lesions.

Excisional procedures

The most common excisional procedure employed for VAIN is upper vaginectomy. In this procedure, the surgeon grasps and tents up the vaginal mucosa, incises the mucosa without penetrating the subepithelial tissue layers such as bladder and rectum. The vaginal mucosa then is carefully separated from the underlying endopelvic fascial plane. The specimen should be oriented, ideally on a cork board, with pins or sutures to ascribe margins and borders. Excision is best utilized for women with unifocal disease, or those who fail or do not tolerate ablative or topical interventions.

The most significant risks of excision include the potential for damage to underlying pelvic visceral structures, which is particularly concerning in postmenopausal women with thin vaginal epithelium. Vaginectomy is commonly associated with vaginal shortening or narrowing, which can be deleterious for quality of life. Retrospective series have described a 30% incidence of recurrence after vaginectomy, likely secondary to incomplete excision of all affected tissue.3

Ablation

Ablation of dysplastic foci with a carbon dioxide (CO2) laser is a common method for treatment of VAIN. CO2 laser should ablate tissue to a 1.5 mm minimum depth.3 The benefit of using CO2 laser is its ability to treat multifocal disease in situ without an extensive excisional procedure.

It is technically more straightforward than upper vaginectomy with less blood loss and shorter surgical times, and it can be easily accomplished in an outpatient surgical or office setting. However, one of its greatest limitations is the difficulty in visualizing all lesions and therefore adequately treating all sites. The vaginal rogations also make adequate laser ablation challenging because laser only is able to effectively ablate tissue that is oriented perpendicular to the laser beam.

In addition, there is no pathologic confirmation of adequacy of excision or margin status. These features may contribute to the modestly higher rates of recurrence of dysplasia following laser ablation, compared with vaginectomy.3 It also has been associated with more vaginal scarring than vaginectomy, which can have a negative effect on sexual health.

Topical agents

The most commonly utilized topical therapy for VAIN is the antimetabolite chemotherapeutic agent 5-fluorouracil (5FU). A typical schedule for 5FU treatment is to apply vaginally, at night, once a week for 8 weeks.4 Because it can cause extensive irritation to the vulvar and urethral epithelium, patients are recommended to apply barrier creams or ointments before and following the use of 5FU for several days, wash hands thoroughly after application, and to rinse and shower in the morning after rising. Severe irritation occurs in up to 16% of patients, but in general it is very well tolerated.

Its virtue is that it is able to conform and travel to all parts of the vaginal mucosa, including those that are poorly visualized within the fornices or vaginal folds. 5FU does not require a hospitalization or surgical procedure, can be applied by the patient at home, and preserves vaginal length and function. In recent reports, 5FU is associated with the lowest rates of recurrence (10%-30%), compared with excision or ablation, and therefore is a very attractive option for primary therapy.3 However, it requires patients to have a degree of comfort with vaginal application of drug and adherence with perineal care strategies to minimize the likelihood of toxicity.

The immune response modifier, imiquimod, that is commonly used in the treatment of vulvar dysplasia also has been described in the treatment of VAIN. It appears to have high rates of clearance (greater than 75%) and be most effective in the treatment of VAIN I.5 It requires application under colposcopic guidance three times a week for 8 weeks, which is a laborious undertaking for both patient and physician. Like 5FU, imiquimod is associated with vulvar and perineal irritation.

Vaginal estrogens are an alternative topical therapy for moderate- and high-grade VAIN and particularly useful for postmenopausal patients. They have been associated with a high rate (up to 90%) of resolution on follow-up vaginal cytology testing and are not associated with toxicities of the above stated therapies.6 Vaginal estrogen can be used alone or in addition to other therapeutic strategies. For example, it can be added to the nontreatment days of 5FU or postoperatively prescribed following laser or excisional procedures.

Radiation

Intracavitary brachytherapy is a technique in which a radiation source is placed within a cylinder or ovoids and placed within the vagina.7 Typically 45 Gy is delivered to a depth 0.5mm below the vaginal mucosal surface (“point z”). Recurrence occurs is approximately 10%-15% of patients, and toxicities can be severe, including vaginal stenosis and ulceration. This aggressive therapy typically is best reserved for cases that are refractory to other therapies. Following radiation, subsequent treatments are more difficult because of radiation-induced changes to the vaginal mucosa that can affect healing.

Vaginal dysplasia is a relatively common sequelae of high-risk HPV, particularly among women who have had a prior hysterectomy for cervical dysplasia. Because of anatomic changes following hysterectomy, adequate visualization and comprehensive vaginal treatment is difficult. Therefore, surgeons should avoid utilization of hysterectomy as a routine strategy to “cure” dysplasia as it may fail to achieve this cure and make subsequent evaluations and treatments of persistent dysplasia more difficult. Women who have had a hysterectomy for dysplasia should be closely followed for several decades, and they should be counseled that they have a persistent risk for vaginal disease. When VAIN develops, clinicians should consider topical therapies as primary treatment options because they may minimize toxicity and have high rates of enduring response.

Dr. Rossi is an assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She had no relevant conflicts of interest.

References

1. Gynecol Oncol. 2016 Jun;141(3):507-10.

2. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2016 Feb;293(2):415-9.

3. Anticancer Res. 2013 Jan;33(1):29-38.

4. Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Dec;130(6):1237-43.

5. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2017 Nov;218:129-36.

6. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2014 Apr;18(2):115-21.

7. Gynecol Oncol. 2007 Jul;106(1):105-11.

Vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia (VAIN) is a condition that frequently poses therapeutic dilemmas for gynecologists. VAIN represents dysplastic changes to the epithelium of the vaginal mucosa, and like cervical neoplasia, the extent of disease is characterized as levels I, II, or III dependent upon the depth of involvement in the epithelial layer by dysplastic cells. While VAIN itself typically is asymptomatic and not a harmful condition, it carries a 12% risk of progression to invasive vaginal carcinoma, so accurate identification, thorough treatment, and ongoing surveillance are essential.1

VAIN is associated with high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, tobacco use, and prior cervical dysplasia. Of women with VAIN, 65% have undergone a prior hysterectomy for cervical dysplasia, which emphasizes the nondefinitive nature of such an intervention.2 These women should be very closely followed for at least 20 years with vaginal cytologic and/or HPV surveillance. High-risk HPV infection is present in 85% of women with VAIN, and the presence of high-risk HPV is a predictor for recurrent VAIN. Recurrent and persistent VAIN also is more common in postmenopausal women and those with multifocal disease.

The most common location for VAIN is at the upper third of the vagina (including the vaginal cuff). It commonly arises within the vaginal fornices, which may be difficult to fully visualize because of their puckered appearance, redundant vaginal tissues, and extensive vaginal rogation.

A diagnosis of VAIN is typically obtained from vaginal cytology which reveals atypical or dysplastic cells. Such a result should prompt the physician to perform vaginal colposcopy and directed biopsies. Comprehensive visualization of the vaginal cuff can be limited in cases where the vaginal fornices are tethered, deeply puckered, or when there is significant mucosal rogation.

The application of 4% acetic acid or Lugol’s iodine are techniques that can enhance the detection of dysplastic vaginal mucosa. Lugol’s iodine selectively stains normal, glycogenated cells, and spares dysplastic glycogen-free cells. The sharp contrast between the brown iodine-stained tissues and the white dysplastic tissues aids in detection of dysplastic areas.

If colposcopic biopsy reveals low grade dysplasia (VAIN I) it does not require intervention, and has a very low rate of conversion to invasive vaginal carcinoma. However moderate- and high-grade vaginal dysplastic lesions should be treated because of the potential for malignant transformation.

Options for treatment of VAIN include topical, ablative, and excisional procedures. Observation also is an option but should be reserved for patients who are closely monitored with repeated colposcopic examinations, and probably should best be reserved for patients with VAIN I or II lesions.

Excisional procedures

The most common excisional procedure employed for VAIN is upper vaginectomy. In this procedure, the surgeon grasps and tents up the vaginal mucosa, incises the mucosa without penetrating the subepithelial tissue layers such as bladder and rectum. The vaginal mucosa then is carefully separated from the underlying endopelvic fascial plane. The specimen should be oriented, ideally on a cork board, with pins or sutures to ascribe margins and borders. Excision is best utilized for women with unifocal disease, or those who fail or do not tolerate ablative or topical interventions.

The most significant risks of excision include the potential for damage to underlying pelvic visceral structures, which is particularly concerning in postmenopausal women with thin vaginal epithelium. Vaginectomy is commonly associated with vaginal shortening or narrowing, which can be deleterious for quality of life. Retrospective series have described a 30% incidence of recurrence after vaginectomy, likely secondary to incomplete excision of all affected tissue.3

Ablation

Ablation of dysplastic foci with a carbon dioxide (CO2) laser is a common method for treatment of VAIN. CO2 laser should ablate tissue to a 1.5 mm minimum depth.3 The benefit of using CO2 laser is its ability to treat multifocal disease in situ without an extensive excisional procedure.

It is technically more straightforward than upper vaginectomy with less blood loss and shorter surgical times, and it can be easily accomplished in an outpatient surgical or office setting. However, one of its greatest limitations is the difficulty in visualizing all lesions and therefore adequately treating all sites. The vaginal rogations also make adequate laser ablation challenging because laser only is able to effectively ablate tissue that is oriented perpendicular to the laser beam.

In addition, there is no pathologic confirmation of adequacy of excision or margin status. These features may contribute to the modestly higher rates of recurrence of dysplasia following laser ablation, compared with vaginectomy.3 It also has been associated with more vaginal scarring than vaginectomy, which can have a negative effect on sexual health.

Topical agents

The most commonly utilized topical therapy for VAIN is the antimetabolite chemotherapeutic agent 5-fluorouracil (5FU). A typical schedule for 5FU treatment is to apply vaginally, at night, once a week for 8 weeks.4 Because it can cause extensive irritation to the vulvar and urethral epithelium, patients are recommended to apply barrier creams or ointments before and following the use of 5FU for several days, wash hands thoroughly after application, and to rinse and shower in the morning after rising. Severe irritation occurs in up to 16% of patients, but in general it is very well tolerated.

Its virtue is that it is able to conform and travel to all parts of the vaginal mucosa, including those that are poorly visualized within the fornices or vaginal folds. 5FU does not require a hospitalization or surgical procedure, can be applied by the patient at home, and preserves vaginal length and function. In recent reports, 5FU is associated with the lowest rates of recurrence (10%-30%), compared with excision or ablation, and therefore is a very attractive option for primary therapy.3 However, it requires patients to have a degree of comfort with vaginal application of drug and adherence with perineal care strategies to minimize the likelihood of toxicity.

The immune response modifier, imiquimod, that is commonly used in the treatment of vulvar dysplasia also has been described in the treatment of VAIN. It appears to have high rates of clearance (greater than 75%) and be most effective in the treatment of VAIN I.5 It requires application under colposcopic guidance three times a week for 8 weeks, which is a laborious undertaking for both patient and physician. Like 5FU, imiquimod is associated with vulvar and perineal irritation.

Vaginal estrogens are an alternative topical therapy for moderate- and high-grade VAIN and particularly useful for postmenopausal patients. They have been associated with a high rate (up to 90%) of resolution on follow-up vaginal cytology testing and are not associated with toxicities of the above stated therapies.6 Vaginal estrogen can be used alone or in addition to other therapeutic strategies. For example, it can be added to the nontreatment days of 5FU or postoperatively prescribed following laser or excisional procedures.

Radiation

Intracavitary brachytherapy is a technique in which a radiation source is placed within a cylinder or ovoids and placed within the vagina.7 Typically 45 Gy is delivered to a depth 0.5mm below the vaginal mucosal surface (“point z”). Recurrence occurs is approximately 10%-15% of patients, and toxicities can be severe, including vaginal stenosis and ulceration. This aggressive therapy typically is best reserved for cases that are refractory to other therapies. Following radiation, subsequent treatments are more difficult because of radiation-induced changes to the vaginal mucosa that can affect healing.

Vaginal dysplasia is a relatively common sequelae of high-risk HPV, particularly among women who have had a prior hysterectomy for cervical dysplasia. Because of anatomic changes following hysterectomy, adequate visualization and comprehensive vaginal treatment is difficult. Therefore, surgeons should avoid utilization of hysterectomy as a routine strategy to “cure” dysplasia as it may fail to achieve this cure and make subsequent evaluations and treatments of persistent dysplasia more difficult. Women who have had a hysterectomy for dysplasia should be closely followed for several decades, and they should be counseled that they have a persistent risk for vaginal disease. When VAIN develops, clinicians should consider topical therapies as primary treatment options because they may minimize toxicity and have high rates of enduring response.

Dr. Rossi is an assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She had no relevant conflicts of interest.

References

1. Gynecol Oncol. 2016 Jun;141(3):507-10.

2. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2016 Feb;293(2):415-9.

3. Anticancer Res. 2013 Jan;33(1):29-38.

4. Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Dec;130(6):1237-43.

5. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2017 Nov;218:129-36.

6. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2014 Apr;18(2):115-21.

7. Gynecol Oncol. 2007 Jul;106(1):105-11.