User login

Vitiligo is the loss of skin pigmentation caused by autoimmune destruction of melanocytes. Multiple pathogenic factors for vitiligo have been described, including CD8+ T lymphocyte/T helper 1 infiltrates in lesional skin1,2 with increased expression of IFN-γ3 and tumor necrosis factor α,3-6 decreased transforming growth factor β,7 and circulating autoantibodies against tyrosine hydroxylase.8 Additionally, several studies have found a high prevalence of antecedent psychological stressors in vitiligo patients, suggesting that specific stressors may trigger and/or exacerbate vitiligo.9-12

The relationship between antecedent psychological stressors and vitiligo extent has not been well studied. Potential mechanisms for stress-triggered vitiligo include increased catecholamines13 and neuropeptides,14 which have been found in vitiligo patients. However, the complex relationship between stressors and subsequent vitiligo is not well defined. We hypothesized that persistent stressors are associated with increased vitiligo extent.

Vitiligo is classically considered to be a silent pigmentary disorder with few or no symptoms. Prior studies have demonstrated that one-third of vitiligo patients report skin symptoms (eg, pruritus, burning), which may be specifically associated with early-onset disease.15-17 Further, we observed that some vitiligo patients report abdominal cramping associated with their disease. Few studies have described the burden of skin symptoms and other associated symptoms in vitiligo or their determinants.

We conducted a prospective questionnaire-based study of 1541 adult vitiligo patients to identify psychological factors that may precede vitiligo onset. We hypothesized that some types of stressors that occur within 2 years prior to disease onset would have specific associations with vitiligo and/or somatic symptoms.

Methods

Study Population and Questionnaire Distribution

This prospective questionnaire-based study was approved by the institutional review board at St. Luke’s-Roosevelt Hospital Center (now Mount Sinai St. Luke’s-Roosevelt) (New York, New York) for adults (>18 years; male or female) with vitiligo. The survey was validated in paper format at St. Luke’s-Roosevelt Hospital Center and distributed online to members of nonprofit support groups for vitiligo vulgaris, as previously described.15

Questionnaire

The a priori aim of this questionnaire was to identify psychological factors that may precede vitiligo onset. The questionnaire consisted of 77 items (55 closed questions and 22 open questions) pertaining to participant demographics/vitiligo phenotype and psychological stressors preceding vitiligo onset. The questions related to this study and response rates are listed in eTable 1. Responses were verified by screening for noninteger or implausible values (eg, <0 or >100 years of age).

Sample Size

The primary outcome used for sample size calculation was the potential association between vitiligo and the presence of antecedent psychological stressors. Using a 2-tailed test, we determined that a sample size of 1264 participants would have 90% power at α=.05 and a baseline proportion of 0.01 (1% presumed prevalence of vitiligo) to detect an odds ratio (OR) of 2.5 or higher.18

Data and Statistical Analysis

Closed question responses were analyzed using descriptive statistics. Open-ended question responses were analyzed using content analysis. Related comments were coded and grouped, with similarities and differences noted. All data processing and statistics were done with SAS version 9.2. Age at diagnosis (years) and number of anatomic sites affected were divided into tertiles for statistical analysis due to wide skewing.

Logistic regression models were constructed with numbers of reported deaths or stressors per participant within the 2 years prior to vitiligo onset as independent variables (0, 1, or ≥2), and symptoms associated with vitiligo as dependent variables. Adjusted ORs were calculated from multivariate models that included sex, current age (continuous), and comorbid autoimmune disease (binary) as covariates. Linear interaction terms were tested and were included in final models if statistically significant (P<.05).

Ordinal logistic regression was used to analyze the relationship between stressors (and other independent variables) and number of anatomic sites affected with vitiligo (tertiles). Ordinal logistic regression models were constructed to examine the impact of psychological stressors on pruritus secondary to vitiligo (not relevant combined with not at all, a little, a lot, very much) as the dependent variable. The proportional odds assumption was met in both models, as judged by score testing (P>.05). Binary logistic regression was used to analyze laterality, body surface area (BSA) greater than 25%, and involvement of the face and/or body with vitiligo lesions (binary).

Binary logistic regression models were constructed with impact of psychological stressors preceding vitiligo onset on comorbid abdominal cramping and specific etiologies as the dependent variables. There were 20 candidate stressors occurring within the 2 years prior to vitiligo onset. Selection methods for predictors were used to identify significant covariates within the context of the other covariates included in the final models. The results of forward, backward, and stepwise approaches were similar, and the stepwise selection output was presented.

Missing values were encountered because some participants did not respond to all the questionnaire items. A complete case analysis was performed (ie, missing values were ignored throughout the study). Data imputation was considered by multiple imputations; however, there were few or no differences between the estimates from the 2 approaches. Therefore, final models did not involve data imputation.

The statistical significance for all estimates was considered to be P<.05. However, a P value near .05 should be interpreted with caution given the multiple dependent tests performed in this study with increased risk for falsely rejecting the null hypothesis.

Results

Survey Population Characteristics

One thousand seven hundred participants started the survey; 1632 completed the survey (96.0% completion rate) and 1553 had been diagnosed with vitiligo by a physician. Twelve participants were excluded because they were younger than 18 years, leaving 1541 evaluable participants. Five hundred thirty-eight participants (34.9%) had comorbid autoimmune disorders. Demographics and disease phenotypes of the study participants are listed in Table 1.

Stressors Preceding Vitiligo Onset

Eight hundred twenty-one participants (56.6%) experienced at least one death or stressor within 2 years prior to vitiligo onset (Table 2), including death of a loved one (16.6%) and stressful life events (51.0%) within the 2 years prior to the onset of vitiligo, especially work/financial problems (10.8%), end of a long-term relationship (10.2%), and family problems (not otherwise specified)(7.8%). Two hundred (13.5%) participants reported experiencing 1 death and 46 (3.1%) reported multiple deaths. Five hundred participants (33.6%) reported experiencing 1 stressor and 259 (17.4%) reported multiple stressors.

Stressors Not Associated With Vitiligo Extent

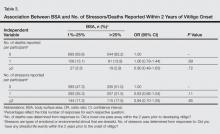

The number of deaths or stressors reported per participant within the 2 years prior to vitiligo onset were not associated with BSA, laterality, or distribution of lesions (Table 3 and eTable 2–eTable 4).

Symptoms Associated With Vitiligo

Five hundred twenty-two participants (34.5%) reported intermittent abdominal cramping, including premenstrual and/or menstrual cramping in women (9.7%), food-related abdominal cramping (4.4%), inflammatory bowel syndrome (IBS)(2.6%), anxiety-related abdominal cramping (1.5%), autoimmune gastrointestinal disorders (1.2%), and “other” etiologies (20.4%). Five hundred ten participants reported itching and/or burning associated with vitiligo lesions (35.1%).

Intermittent abdominal cramping overall was associated with a BSA greater than 75% (OR, 1.65; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.17-2.32; P=.004). However, specific etiologies of abdominal cramping were not significantly associated with BSA (P≥.11). In contrast, itching and/or burning from vitiligo lesions was associated with a BSA greater than 25% (OR, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.23-1.90; P<.0001).

Association Between Number of Stressors and Symptoms in Vitiligo

A history of multiple stressors (≥2) within the 2 years prior to vitiligo onset was associated with intermittent abdominal cramping overall (OR, 1.84; 95% CI, 1.38-2.47; P<.0001), including premenstrual and/or menstrual cramping in women (OR, 1.84; 95% CI, 1.15-2.95; P=.01), IBS (OR, 3.29; 95% CI, 1.34-8.05; P=.01), and autoimmune gastrointestinal disorders (OR, 4.02; 95% CI, 1.27-12.80; P=.02)(eTable 5). These associations remained significant in multivariate models that included age, sex, and BSA as covariates. However, a history of 1 stressor or death or multiple deaths in the 2 years prior to vitiligo onset was not associated with any etiology of abdominal cramping.

Experiencing 1 (OR, 1.43; 95% CI, 1.12-1.82; P=.005) or multiple stressors (OR, 1.51; 95% CI, 1.12-2.04; P=.007) also was associated with itching and/or burning secondary to vitiligo. This association remained significant in a multivariate model that included age, sex, and BSA as covariates. However, a history of 1 or multiple deaths in the 2 years prior to vitiligo onset was not associated with itching and/or burning.

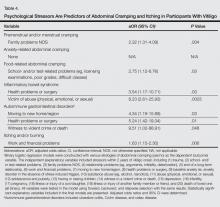

Association Between Specific Stressors and Vitiligo Symptoms

Perimenstrual (premenstrual and/or menstrual) cramping in women was associated with family problems (not otherwise specified) within the 2 years prior to vitiligo onset (Table 4). Food-related abdominal cramping was associated with school- and/or test-related stressors. Diagnosis of IBS was associated with health problems or surgery and being a victim of abuse within the 2 years prior to onset of vitiligo. Autoimmune gastrointestinal disorders were associated with moving to a new home/region, health problems or surgery, and witness to a violent crime or death. Finally, itching and/or burning of vitiligo lesions was associated with work and financial problems.

Comment

The present study found a high frequency of stressful life events and deaths of loved ones occurring within the 2 years preceding vitiligo onset. A history of multiple stressors but not deaths of loved ones was associated with more frequent symptoms in vitiligo patients, including itching and/or burning and intermittent abdominal pain. Specific stressors were associated with intermittent abdominal cramping, which occurred in approximately one-third of vitiligo patients. Abdominal cramping was related to menses in women, anxiety, foods, IBS, autoimmune gastrointestinal disorders, and other etiologies of abdominal cramping, which underscores the complex relationship between stressors, vitiligo, and inflammation. It is possible that stress-related immune abnormalities occur in vitiligo, which may influence the development of other autoimmune disorders. Alternatively, abdominal symptoms may precede and perhaps contribute to psychological stressors and impaired quality of life in vitiligo patients; however, the cross-sectional nature of the study did not allow us to elucidate this temporal relationship.

The present study found that 56.6% of participants experienced 1 or more deaths (17%) and/or stressful life events (51%) within the 2 years prior to vitiligo onset. These results are consistent with prior smaller studies that demonstrated a high frequency of stressful events preceding vitiligo onset. A case-controlled study found stressful events in 12 of 21 (57%) Romanian children with vitiligo, which was higher than controls.19 Another questionnaire-based, case-controlled study compared a heterogeneous group of 32 adolescent and adult Romanian patients with vitiligo and found higher odds of a stressful event in women preceding vitiligo diagnosis compared to controls.10 A retrospective analysis of 65 Croatian patients with vitiligo also reported that 56.9% (37/65) had some associated psychological factors.9 Another retrospective study of 31 adults with vitiligo found increased occurrence of 3 or more uncontrollable events, decreased perceived social support, and increased anxiety in vitiligo patients versus 116 other dermatologic disease controls.12 A questionnaire-based study found increased bereavements, changes in sleeping and eating habits, and personal injuries/illnesses in 73 British adults with vitiligo compared to 73 other age- and sex-matched dermatologic disease controls.11 All of these studies were limited by a small sample size, and the patient populations were localized to a regional dermatology referral center. The present study provided a larger analysis of stressful life events preceding vitiligo onset and included a diverse patient population.

The present study found that stressful life events and deaths of a loved one are not associated with vitiligo extent and distribution. This finding suggests that stressful life events may act as vitiligo triggers in genetically predisposed individuals, but ultimately the disease course and prognosis are driven by other factors, such as increased systemic inflammation or other immunologic abnormalities. Indeed, Silverberg and Silverberg20 and other investigators21,22 reported relative deficiencies of 25-hydroxyvitamin D,23 vitamins B6 and B12, and folic acid,20 as well as elevated serum homocysteine levels in vitiligo patients. Increased serum homocysteine levels were associated with increased BSA of vitiligo lesions.20 Elevated serum homocysteine levels also have been associated with increased inflammation in coronary artery disease,24 psoriasis,25,26 and in vitro.27 These laboratory anomalies likely reflect an underlying predisposition toward vitiligo, which might be triggered by stress responses or secondarily altered immune responses.

The present study had several strengths, including being prospective with a large sample size. The patient population included a large sample of men and women with representation of various adult ages and vitiligo extent. However, this study also had potential limitations. Measures of vitiligo extent were self-reported and were not clinically assessed. To address this limitation, we validated the questionnaire before posting it online.15 Invitation to participate in the survey was distributed by vitiligo support groups, which may have resulted in a selection bias toward participants with greater disease severity or with a poorer quality of life associated with vitiligo. Invitation to participate in this study was sent to members of vitiligo support groups, which allowed for recruitment of a large number of vitiligo patients despite a relatively low prevalence of disease in the general population. However, there are several challenges using this approach for nonvitiligo controls. Using participants with another dermatological disease as a control group may yield spurious results. Ideally, a large randomized sample of healthy participants with minimization of bias should be used for controls, which is an ambitious undertaking that was beyond the scope of this pilot study and will be the subject of future studies. Finally, this analysis found associations between stressors that occurred in the 2 years prior to vitiligo onset with symptomatic disease. We chose a broad interval for stressors because early vitiligo lesions may go unnoticed, making recognition of stressors occurring within days or weeks of onset infeasible. Further, we considered that chronic and prolonged stressors are more likely to have harmful consequences than acute stressors. Thus, stressors occurring within a more narrow interval (eg, 2 months) may not have the same association with vitiligo. Future studies are warranted to precisely identify the type and timing of psychological stressors preceding vitiligo onset.

Conclusion

In conclusion, there is a high prevalence of stressful life events preceding vitiligo, which may play an important role as disease triggers as well as predict the presence of intermittent abdominal cramping and itching or burning of skin. These associations indicate that screening of vitiligo patients for psychological stressors, abdominal cramping, and itching and/or burning of skin should be included in the routine assessment of vitiligo patients.

Appendix

1. Goronzy J, Weyand CM, Waase I. T cell subpopulations in inflammatory bowel disease: evidence for a defective induction of T8+ suppressor/cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Clin Exp Immunol. 1985;61:593-600.

2. Ongenae K, Van Geel N, Naeyaert JM. Evidence for an autoimmune pathogenesis of vitiligo. Pigment Cell Res. 2003;16:90-100.

3. Grimes PE, Morris R, Avaniss-Aghajani E, et al. Topical tacrolimus therapy for vitiligo: therapeutic responses and skin messenger RNA expression of proinflammatory cytokines. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:52-61.

4. Birol A, Kisa U, Kurtipek GS, et al. Increased tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-alpha) and interleukin 1 alpha (IL1-alpha) levels in the lesional skin of patients with nonsegmental vitiligo. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:992-993.

5. Moretti S, Spallanzani A, Amato L, et al. New insights into the pathogenesis of vitiligo: imbalance of epidermal cytokines at sites of lesions. Pigment Cell Res. 2002;15:87-92.

6. Zailaie MZ. Decreased proinflammatory cytokine production by peripheral blood mononuclear cells from vitiligo patients following aspirin treatment. Saudi Med J. 2005;26:799-805.

7. Basak PY, Adiloglu AK, Ceyhan AM, et al. The role of helper and regulatory T cells in the pathogenesis of vitiligo. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:256-260.

8. Kemp EH, Emhemad S, Akhtar S, et al. Autoantibodies against tyrosine hydroxylase in patients with non-segmental (generalised) vitiligo. Exp Dermatol. 2011;20:35-40.

9. Barisic´-Drusko V, Rucevic I. Trigger factors in childhood psoriasis and vitiligo. Coll Antropol. 2004;28:277-285.

10. Manolache L, Benea V. Stress in patients with alopecia areata and vitiligo. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:921-928.

11. Papadopoulos L, Bor R, Legg C, et al. Impact of life events on the onset of vitiligo in adults: preliminary evidence for a psychological dimension in aetiology. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1998;23:243-248.

12. Picardi A, Pasquini P, Cattaruzza MS, et al. Stressful life events, social support, attachment security and alexithymia in vitiligo. a case-control study. Psychother Psychosom. 2003;72:150-158.

13. Salzer BA, Schallreuter KU. Investigation of the personality structure in patients with vitiligo and a possible association with impaired catecholamine metabolism. Dermatology. 1995;190:109-115.

14. Al’Abadie MS, Senior HJ, Bleehen SS, et al. Neuropeptide and neuronal marker studies in vitiligo. Br J Dermatol. 1994;131:160-165.

15. Silverberg JI, Silverberg NB. Association between vitiligo extent and distribution and quality-of-life impairment. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:159-164.

16. Silverberg JI, Silverberg NB. Quality of life impairments in children and adolescents with vitiligo. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:309-318.

17. Kanwar AJ, Mahajan R, Parsad D. Effect of age at onset on disease characteristics in vitiligo. J Cutan Med Surg. 2013;17:253-258.

18. Hsieh FY, Bloch DA, Larsen MD. A simple method of sample size calculation for linear and logistic regression. Stat Med. 1998;17:1623-1634.

19. Manolache L, Petrescu-Seceleanu D, Benea V. Correlation of stressful events with onset of vitiligo in children. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:187-188.

20. Silverberg JI, Silverberg NB. Serum homocysteine as a biomarker of vitiligo vulgaris severity: a pilot study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:445-447.

21. Shaker OG, El-Tahlawi SM. Is there a relationship between homocysteine and vitiligo? a pilot study. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:720-724.

22. Balci DD, Yonden Z, Yenin JZ, et al. Serum homocysteine, folic acid and vitamin B12 levels in vitiligo. Eur J Dermatol. 2009;19:382-383.

23. Silverberg JI, Silverberg AI, Malka E, et al. A pilot study assessing the role of 25 hydroxy vitamin D levels in patients with vitiligo vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:937-941.

24. Jonasson T, Ohlin AK, Gottsater A, et al. Plasma homocysteine and markers for oxidative stress and inflammation in patients with coronary artery disease—a prospective randomized study of vitamin supplementation. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2005;43:628-634.

25. Cakmak SK, Gul U, Kilic C, et al. Homocysteine, vitamin B12 and folic acid levels in psoriasis patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:300-303.

26. Malerba M, Gisondi P, Radaeli A, et al. Plasma homocysteine and folate levels in patients with chronic plaque psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155:1165-1169.

27. Shastry S, James LR. Homocysteine-induced macrophage inflammatory protein-2 production by glomerular mesangial cells is mediated by PI3 Kinase and p38 MAPK. J Inflamm (Lond). 2009;6:27.

Vitiligo is the loss of skin pigmentation caused by autoimmune destruction of melanocytes. Multiple pathogenic factors for vitiligo have been described, including CD8+ T lymphocyte/T helper 1 infiltrates in lesional skin1,2 with increased expression of IFN-γ3 and tumor necrosis factor α,3-6 decreased transforming growth factor β,7 and circulating autoantibodies against tyrosine hydroxylase.8 Additionally, several studies have found a high prevalence of antecedent psychological stressors in vitiligo patients, suggesting that specific stressors may trigger and/or exacerbate vitiligo.9-12

The relationship between antecedent psychological stressors and vitiligo extent has not been well studied. Potential mechanisms for stress-triggered vitiligo include increased catecholamines13 and neuropeptides,14 which have been found in vitiligo patients. However, the complex relationship between stressors and subsequent vitiligo is not well defined. We hypothesized that persistent stressors are associated with increased vitiligo extent.

Vitiligo is classically considered to be a silent pigmentary disorder with few or no symptoms. Prior studies have demonstrated that one-third of vitiligo patients report skin symptoms (eg, pruritus, burning), which may be specifically associated with early-onset disease.15-17 Further, we observed that some vitiligo patients report abdominal cramping associated with their disease. Few studies have described the burden of skin symptoms and other associated symptoms in vitiligo or their determinants.

We conducted a prospective questionnaire-based study of 1541 adult vitiligo patients to identify psychological factors that may precede vitiligo onset. We hypothesized that some types of stressors that occur within 2 years prior to disease onset would have specific associations with vitiligo and/or somatic symptoms.

Methods

Study Population and Questionnaire Distribution

This prospective questionnaire-based study was approved by the institutional review board at St. Luke’s-Roosevelt Hospital Center (now Mount Sinai St. Luke’s-Roosevelt) (New York, New York) for adults (>18 years; male or female) with vitiligo. The survey was validated in paper format at St. Luke’s-Roosevelt Hospital Center and distributed online to members of nonprofit support groups for vitiligo vulgaris, as previously described.15

Questionnaire

The a priori aim of this questionnaire was to identify psychological factors that may precede vitiligo onset. The questionnaire consisted of 77 items (55 closed questions and 22 open questions) pertaining to participant demographics/vitiligo phenotype and psychological stressors preceding vitiligo onset. The questions related to this study and response rates are listed in eTable 1. Responses were verified by screening for noninteger or implausible values (eg, <0 or >100 years of age).

Sample Size

The primary outcome used for sample size calculation was the potential association between vitiligo and the presence of antecedent psychological stressors. Using a 2-tailed test, we determined that a sample size of 1264 participants would have 90% power at α=.05 and a baseline proportion of 0.01 (1% presumed prevalence of vitiligo) to detect an odds ratio (OR) of 2.5 or higher.18

Data and Statistical Analysis

Closed question responses were analyzed using descriptive statistics. Open-ended question responses were analyzed using content analysis. Related comments were coded and grouped, with similarities and differences noted. All data processing and statistics were done with SAS version 9.2. Age at diagnosis (years) and number of anatomic sites affected were divided into tertiles for statistical analysis due to wide skewing.

Logistic regression models were constructed with numbers of reported deaths or stressors per participant within the 2 years prior to vitiligo onset as independent variables (0, 1, or ≥2), and symptoms associated with vitiligo as dependent variables. Adjusted ORs were calculated from multivariate models that included sex, current age (continuous), and comorbid autoimmune disease (binary) as covariates. Linear interaction terms were tested and were included in final models if statistically significant (P<.05).

Ordinal logistic regression was used to analyze the relationship between stressors (and other independent variables) and number of anatomic sites affected with vitiligo (tertiles). Ordinal logistic regression models were constructed to examine the impact of psychological stressors on pruritus secondary to vitiligo (not relevant combined with not at all, a little, a lot, very much) as the dependent variable. The proportional odds assumption was met in both models, as judged by score testing (P>.05). Binary logistic regression was used to analyze laterality, body surface area (BSA) greater than 25%, and involvement of the face and/or body with vitiligo lesions (binary).

Binary logistic regression models were constructed with impact of psychological stressors preceding vitiligo onset on comorbid abdominal cramping and specific etiologies as the dependent variables. There were 20 candidate stressors occurring within the 2 years prior to vitiligo onset. Selection methods for predictors were used to identify significant covariates within the context of the other covariates included in the final models. The results of forward, backward, and stepwise approaches were similar, and the stepwise selection output was presented.

Missing values were encountered because some participants did not respond to all the questionnaire items. A complete case analysis was performed (ie, missing values were ignored throughout the study). Data imputation was considered by multiple imputations; however, there were few or no differences between the estimates from the 2 approaches. Therefore, final models did not involve data imputation.

The statistical significance for all estimates was considered to be P<.05. However, a P value near .05 should be interpreted with caution given the multiple dependent tests performed in this study with increased risk for falsely rejecting the null hypothesis.

Results

Survey Population Characteristics

One thousand seven hundred participants started the survey; 1632 completed the survey (96.0% completion rate) and 1553 had been diagnosed with vitiligo by a physician. Twelve participants were excluded because they were younger than 18 years, leaving 1541 evaluable participants. Five hundred thirty-eight participants (34.9%) had comorbid autoimmune disorders. Demographics and disease phenotypes of the study participants are listed in Table 1.

Stressors Preceding Vitiligo Onset

Eight hundred twenty-one participants (56.6%) experienced at least one death or stressor within 2 years prior to vitiligo onset (Table 2), including death of a loved one (16.6%) and stressful life events (51.0%) within the 2 years prior to the onset of vitiligo, especially work/financial problems (10.8%), end of a long-term relationship (10.2%), and family problems (not otherwise specified)(7.8%). Two hundred (13.5%) participants reported experiencing 1 death and 46 (3.1%) reported multiple deaths. Five hundred participants (33.6%) reported experiencing 1 stressor and 259 (17.4%) reported multiple stressors.

Stressors Not Associated With Vitiligo Extent

The number of deaths or stressors reported per participant within the 2 years prior to vitiligo onset were not associated with BSA, laterality, or distribution of lesions (Table 3 and eTable 2–eTable 4).

Symptoms Associated With Vitiligo

Five hundred twenty-two participants (34.5%) reported intermittent abdominal cramping, including premenstrual and/or menstrual cramping in women (9.7%), food-related abdominal cramping (4.4%), inflammatory bowel syndrome (IBS)(2.6%), anxiety-related abdominal cramping (1.5%), autoimmune gastrointestinal disorders (1.2%), and “other” etiologies (20.4%). Five hundred ten participants reported itching and/or burning associated with vitiligo lesions (35.1%).

Intermittent abdominal cramping overall was associated with a BSA greater than 75% (OR, 1.65; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.17-2.32; P=.004). However, specific etiologies of abdominal cramping were not significantly associated with BSA (P≥.11). In contrast, itching and/or burning from vitiligo lesions was associated with a BSA greater than 25% (OR, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.23-1.90; P<.0001).

Association Between Number of Stressors and Symptoms in Vitiligo

A history of multiple stressors (≥2) within the 2 years prior to vitiligo onset was associated with intermittent abdominal cramping overall (OR, 1.84; 95% CI, 1.38-2.47; P<.0001), including premenstrual and/or menstrual cramping in women (OR, 1.84; 95% CI, 1.15-2.95; P=.01), IBS (OR, 3.29; 95% CI, 1.34-8.05; P=.01), and autoimmune gastrointestinal disorders (OR, 4.02; 95% CI, 1.27-12.80; P=.02)(eTable 5). These associations remained significant in multivariate models that included age, sex, and BSA as covariates. However, a history of 1 stressor or death or multiple deaths in the 2 years prior to vitiligo onset was not associated with any etiology of abdominal cramping.

Experiencing 1 (OR, 1.43; 95% CI, 1.12-1.82; P=.005) or multiple stressors (OR, 1.51; 95% CI, 1.12-2.04; P=.007) also was associated with itching and/or burning secondary to vitiligo. This association remained significant in a multivariate model that included age, sex, and BSA as covariates. However, a history of 1 or multiple deaths in the 2 years prior to vitiligo onset was not associated with itching and/or burning.

Association Between Specific Stressors and Vitiligo Symptoms

Perimenstrual (premenstrual and/or menstrual) cramping in women was associated with family problems (not otherwise specified) within the 2 years prior to vitiligo onset (Table 4). Food-related abdominal cramping was associated with school- and/or test-related stressors. Diagnosis of IBS was associated with health problems or surgery and being a victim of abuse within the 2 years prior to onset of vitiligo. Autoimmune gastrointestinal disorders were associated with moving to a new home/region, health problems or surgery, and witness to a violent crime or death. Finally, itching and/or burning of vitiligo lesions was associated with work and financial problems.

Comment

The present study found a high frequency of stressful life events and deaths of loved ones occurring within the 2 years preceding vitiligo onset. A history of multiple stressors but not deaths of loved ones was associated with more frequent symptoms in vitiligo patients, including itching and/or burning and intermittent abdominal pain. Specific stressors were associated with intermittent abdominal cramping, which occurred in approximately one-third of vitiligo patients. Abdominal cramping was related to menses in women, anxiety, foods, IBS, autoimmune gastrointestinal disorders, and other etiologies of abdominal cramping, which underscores the complex relationship between stressors, vitiligo, and inflammation. It is possible that stress-related immune abnormalities occur in vitiligo, which may influence the development of other autoimmune disorders. Alternatively, abdominal symptoms may precede and perhaps contribute to psychological stressors and impaired quality of life in vitiligo patients; however, the cross-sectional nature of the study did not allow us to elucidate this temporal relationship.

The present study found that 56.6% of participants experienced 1 or more deaths (17%) and/or stressful life events (51%) within the 2 years prior to vitiligo onset. These results are consistent with prior smaller studies that demonstrated a high frequency of stressful events preceding vitiligo onset. A case-controlled study found stressful events in 12 of 21 (57%) Romanian children with vitiligo, which was higher than controls.19 Another questionnaire-based, case-controlled study compared a heterogeneous group of 32 adolescent and adult Romanian patients with vitiligo and found higher odds of a stressful event in women preceding vitiligo diagnosis compared to controls.10 A retrospective analysis of 65 Croatian patients with vitiligo also reported that 56.9% (37/65) had some associated psychological factors.9 Another retrospective study of 31 adults with vitiligo found increased occurrence of 3 or more uncontrollable events, decreased perceived social support, and increased anxiety in vitiligo patients versus 116 other dermatologic disease controls.12 A questionnaire-based study found increased bereavements, changes in sleeping and eating habits, and personal injuries/illnesses in 73 British adults with vitiligo compared to 73 other age- and sex-matched dermatologic disease controls.11 All of these studies were limited by a small sample size, and the patient populations were localized to a regional dermatology referral center. The present study provided a larger analysis of stressful life events preceding vitiligo onset and included a diverse patient population.

The present study found that stressful life events and deaths of a loved one are not associated with vitiligo extent and distribution. This finding suggests that stressful life events may act as vitiligo triggers in genetically predisposed individuals, but ultimately the disease course and prognosis are driven by other factors, such as increased systemic inflammation or other immunologic abnormalities. Indeed, Silverberg and Silverberg20 and other investigators21,22 reported relative deficiencies of 25-hydroxyvitamin D,23 vitamins B6 and B12, and folic acid,20 as well as elevated serum homocysteine levels in vitiligo patients. Increased serum homocysteine levels were associated with increased BSA of vitiligo lesions.20 Elevated serum homocysteine levels also have been associated with increased inflammation in coronary artery disease,24 psoriasis,25,26 and in vitro.27 These laboratory anomalies likely reflect an underlying predisposition toward vitiligo, which might be triggered by stress responses or secondarily altered immune responses.

The present study had several strengths, including being prospective with a large sample size. The patient population included a large sample of men and women with representation of various adult ages and vitiligo extent. However, this study also had potential limitations. Measures of vitiligo extent were self-reported and were not clinically assessed. To address this limitation, we validated the questionnaire before posting it online.15 Invitation to participate in the survey was distributed by vitiligo support groups, which may have resulted in a selection bias toward participants with greater disease severity or with a poorer quality of life associated with vitiligo. Invitation to participate in this study was sent to members of vitiligo support groups, which allowed for recruitment of a large number of vitiligo patients despite a relatively low prevalence of disease in the general population. However, there are several challenges using this approach for nonvitiligo controls. Using participants with another dermatological disease as a control group may yield spurious results. Ideally, a large randomized sample of healthy participants with minimization of bias should be used for controls, which is an ambitious undertaking that was beyond the scope of this pilot study and will be the subject of future studies. Finally, this analysis found associations between stressors that occurred in the 2 years prior to vitiligo onset with symptomatic disease. We chose a broad interval for stressors because early vitiligo lesions may go unnoticed, making recognition of stressors occurring within days or weeks of onset infeasible. Further, we considered that chronic and prolonged stressors are more likely to have harmful consequences than acute stressors. Thus, stressors occurring within a more narrow interval (eg, 2 months) may not have the same association with vitiligo. Future studies are warranted to precisely identify the type and timing of psychological stressors preceding vitiligo onset.

Conclusion

In conclusion, there is a high prevalence of stressful life events preceding vitiligo, which may play an important role as disease triggers as well as predict the presence of intermittent abdominal cramping and itching or burning of skin. These associations indicate that screening of vitiligo patients for psychological stressors, abdominal cramping, and itching and/or burning of skin should be included in the routine assessment of vitiligo patients.

Appendix

Vitiligo is the loss of skin pigmentation caused by autoimmune destruction of melanocytes. Multiple pathogenic factors for vitiligo have been described, including CD8+ T lymphocyte/T helper 1 infiltrates in lesional skin1,2 with increased expression of IFN-γ3 and tumor necrosis factor α,3-6 decreased transforming growth factor β,7 and circulating autoantibodies against tyrosine hydroxylase.8 Additionally, several studies have found a high prevalence of antecedent psychological stressors in vitiligo patients, suggesting that specific stressors may trigger and/or exacerbate vitiligo.9-12

The relationship between antecedent psychological stressors and vitiligo extent has not been well studied. Potential mechanisms for stress-triggered vitiligo include increased catecholamines13 and neuropeptides,14 which have been found in vitiligo patients. However, the complex relationship between stressors and subsequent vitiligo is not well defined. We hypothesized that persistent stressors are associated with increased vitiligo extent.

Vitiligo is classically considered to be a silent pigmentary disorder with few or no symptoms. Prior studies have demonstrated that one-third of vitiligo patients report skin symptoms (eg, pruritus, burning), which may be specifically associated with early-onset disease.15-17 Further, we observed that some vitiligo patients report abdominal cramping associated with their disease. Few studies have described the burden of skin symptoms and other associated symptoms in vitiligo or their determinants.

We conducted a prospective questionnaire-based study of 1541 adult vitiligo patients to identify psychological factors that may precede vitiligo onset. We hypothesized that some types of stressors that occur within 2 years prior to disease onset would have specific associations with vitiligo and/or somatic symptoms.

Methods

Study Population and Questionnaire Distribution

This prospective questionnaire-based study was approved by the institutional review board at St. Luke’s-Roosevelt Hospital Center (now Mount Sinai St. Luke’s-Roosevelt) (New York, New York) for adults (>18 years; male or female) with vitiligo. The survey was validated in paper format at St. Luke’s-Roosevelt Hospital Center and distributed online to members of nonprofit support groups for vitiligo vulgaris, as previously described.15

Questionnaire

The a priori aim of this questionnaire was to identify psychological factors that may precede vitiligo onset. The questionnaire consisted of 77 items (55 closed questions and 22 open questions) pertaining to participant demographics/vitiligo phenotype and psychological stressors preceding vitiligo onset. The questions related to this study and response rates are listed in eTable 1. Responses were verified by screening for noninteger or implausible values (eg, <0 or >100 years of age).

Sample Size

The primary outcome used for sample size calculation was the potential association between vitiligo and the presence of antecedent psychological stressors. Using a 2-tailed test, we determined that a sample size of 1264 participants would have 90% power at α=.05 and a baseline proportion of 0.01 (1% presumed prevalence of vitiligo) to detect an odds ratio (OR) of 2.5 or higher.18

Data and Statistical Analysis

Closed question responses were analyzed using descriptive statistics. Open-ended question responses were analyzed using content analysis. Related comments were coded and grouped, with similarities and differences noted. All data processing and statistics were done with SAS version 9.2. Age at diagnosis (years) and number of anatomic sites affected were divided into tertiles for statistical analysis due to wide skewing.

Logistic regression models were constructed with numbers of reported deaths or stressors per participant within the 2 years prior to vitiligo onset as independent variables (0, 1, or ≥2), and symptoms associated with vitiligo as dependent variables. Adjusted ORs were calculated from multivariate models that included sex, current age (continuous), and comorbid autoimmune disease (binary) as covariates. Linear interaction terms were tested and were included in final models if statistically significant (P<.05).

Ordinal logistic regression was used to analyze the relationship between stressors (and other independent variables) and number of anatomic sites affected with vitiligo (tertiles). Ordinal logistic regression models were constructed to examine the impact of psychological stressors on pruritus secondary to vitiligo (not relevant combined with not at all, a little, a lot, very much) as the dependent variable. The proportional odds assumption was met in both models, as judged by score testing (P>.05). Binary logistic regression was used to analyze laterality, body surface area (BSA) greater than 25%, and involvement of the face and/or body with vitiligo lesions (binary).

Binary logistic regression models were constructed with impact of psychological stressors preceding vitiligo onset on comorbid abdominal cramping and specific etiologies as the dependent variables. There were 20 candidate stressors occurring within the 2 years prior to vitiligo onset. Selection methods for predictors were used to identify significant covariates within the context of the other covariates included in the final models. The results of forward, backward, and stepwise approaches were similar, and the stepwise selection output was presented.

Missing values were encountered because some participants did not respond to all the questionnaire items. A complete case analysis was performed (ie, missing values were ignored throughout the study). Data imputation was considered by multiple imputations; however, there were few or no differences between the estimates from the 2 approaches. Therefore, final models did not involve data imputation.

The statistical significance for all estimates was considered to be P<.05. However, a P value near .05 should be interpreted with caution given the multiple dependent tests performed in this study with increased risk for falsely rejecting the null hypothesis.

Results

Survey Population Characteristics

One thousand seven hundred participants started the survey; 1632 completed the survey (96.0% completion rate) and 1553 had been diagnosed with vitiligo by a physician. Twelve participants were excluded because they were younger than 18 years, leaving 1541 evaluable participants. Five hundred thirty-eight participants (34.9%) had comorbid autoimmune disorders. Demographics and disease phenotypes of the study participants are listed in Table 1.

Stressors Preceding Vitiligo Onset

Eight hundred twenty-one participants (56.6%) experienced at least one death or stressor within 2 years prior to vitiligo onset (Table 2), including death of a loved one (16.6%) and stressful life events (51.0%) within the 2 years prior to the onset of vitiligo, especially work/financial problems (10.8%), end of a long-term relationship (10.2%), and family problems (not otherwise specified)(7.8%). Two hundred (13.5%) participants reported experiencing 1 death and 46 (3.1%) reported multiple deaths. Five hundred participants (33.6%) reported experiencing 1 stressor and 259 (17.4%) reported multiple stressors.

Stressors Not Associated With Vitiligo Extent

The number of deaths or stressors reported per participant within the 2 years prior to vitiligo onset were not associated with BSA, laterality, or distribution of lesions (Table 3 and eTable 2–eTable 4).

Symptoms Associated With Vitiligo

Five hundred twenty-two participants (34.5%) reported intermittent abdominal cramping, including premenstrual and/or menstrual cramping in women (9.7%), food-related abdominal cramping (4.4%), inflammatory bowel syndrome (IBS)(2.6%), anxiety-related abdominal cramping (1.5%), autoimmune gastrointestinal disorders (1.2%), and “other” etiologies (20.4%). Five hundred ten participants reported itching and/or burning associated with vitiligo lesions (35.1%).

Intermittent abdominal cramping overall was associated with a BSA greater than 75% (OR, 1.65; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.17-2.32; P=.004). However, specific etiologies of abdominal cramping were not significantly associated with BSA (P≥.11). In contrast, itching and/or burning from vitiligo lesions was associated with a BSA greater than 25% (OR, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.23-1.90; P<.0001).

Association Between Number of Stressors and Symptoms in Vitiligo

A history of multiple stressors (≥2) within the 2 years prior to vitiligo onset was associated with intermittent abdominal cramping overall (OR, 1.84; 95% CI, 1.38-2.47; P<.0001), including premenstrual and/or menstrual cramping in women (OR, 1.84; 95% CI, 1.15-2.95; P=.01), IBS (OR, 3.29; 95% CI, 1.34-8.05; P=.01), and autoimmune gastrointestinal disorders (OR, 4.02; 95% CI, 1.27-12.80; P=.02)(eTable 5). These associations remained significant in multivariate models that included age, sex, and BSA as covariates. However, a history of 1 stressor or death or multiple deaths in the 2 years prior to vitiligo onset was not associated with any etiology of abdominal cramping.

Experiencing 1 (OR, 1.43; 95% CI, 1.12-1.82; P=.005) or multiple stressors (OR, 1.51; 95% CI, 1.12-2.04; P=.007) also was associated with itching and/or burning secondary to vitiligo. This association remained significant in a multivariate model that included age, sex, and BSA as covariates. However, a history of 1 or multiple deaths in the 2 years prior to vitiligo onset was not associated with itching and/or burning.

Association Between Specific Stressors and Vitiligo Symptoms

Perimenstrual (premenstrual and/or menstrual) cramping in women was associated with family problems (not otherwise specified) within the 2 years prior to vitiligo onset (Table 4). Food-related abdominal cramping was associated with school- and/or test-related stressors. Diagnosis of IBS was associated with health problems or surgery and being a victim of abuse within the 2 years prior to onset of vitiligo. Autoimmune gastrointestinal disorders were associated with moving to a new home/region, health problems or surgery, and witness to a violent crime or death. Finally, itching and/or burning of vitiligo lesions was associated with work and financial problems.

Comment

The present study found a high frequency of stressful life events and deaths of loved ones occurring within the 2 years preceding vitiligo onset. A history of multiple stressors but not deaths of loved ones was associated with more frequent symptoms in vitiligo patients, including itching and/or burning and intermittent abdominal pain. Specific stressors were associated with intermittent abdominal cramping, which occurred in approximately one-third of vitiligo patients. Abdominal cramping was related to menses in women, anxiety, foods, IBS, autoimmune gastrointestinal disorders, and other etiologies of abdominal cramping, which underscores the complex relationship between stressors, vitiligo, and inflammation. It is possible that stress-related immune abnormalities occur in vitiligo, which may influence the development of other autoimmune disorders. Alternatively, abdominal symptoms may precede and perhaps contribute to psychological stressors and impaired quality of life in vitiligo patients; however, the cross-sectional nature of the study did not allow us to elucidate this temporal relationship.

The present study found that 56.6% of participants experienced 1 or more deaths (17%) and/or stressful life events (51%) within the 2 years prior to vitiligo onset. These results are consistent with prior smaller studies that demonstrated a high frequency of stressful events preceding vitiligo onset. A case-controlled study found stressful events in 12 of 21 (57%) Romanian children with vitiligo, which was higher than controls.19 Another questionnaire-based, case-controlled study compared a heterogeneous group of 32 adolescent and adult Romanian patients with vitiligo and found higher odds of a stressful event in women preceding vitiligo diagnosis compared to controls.10 A retrospective analysis of 65 Croatian patients with vitiligo also reported that 56.9% (37/65) had some associated psychological factors.9 Another retrospective study of 31 adults with vitiligo found increased occurrence of 3 or more uncontrollable events, decreased perceived social support, and increased anxiety in vitiligo patients versus 116 other dermatologic disease controls.12 A questionnaire-based study found increased bereavements, changes in sleeping and eating habits, and personal injuries/illnesses in 73 British adults with vitiligo compared to 73 other age- and sex-matched dermatologic disease controls.11 All of these studies were limited by a small sample size, and the patient populations were localized to a regional dermatology referral center. The present study provided a larger analysis of stressful life events preceding vitiligo onset and included a diverse patient population.

The present study found that stressful life events and deaths of a loved one are not associated with vitiligo extent and distribution. This finding suggests that stressful life events may act as vitiligo triggers in genetically predisposed individuals, but ultimately the disease course and prognosis are driven by other factors, such as increased systemic inflammation or other immunologic abnormalities. Indeed, Silverberg and Silverberg20 and other investigators21,22 reported relative deficiencies of 25-hydroxyvitamin D,23 vitamins B6 and B12, and folic acid,20 as well as elevated serum homocysteine levels in vitiligo patients. Increased serum homocysteine levels were associated with increased BSA of vitiligo lesions.20 Elevated serum homocysteine levels also have been associated with increased inflammation in coronary artery disease,24 psoriasis,25,26 and in vitro.27 These laboratory anomalies likely reflect an underlying predisposition toward vitiligo, which might be triggered by stress responses or secondarily altered immune responses.

The present study had several strengths, including being prospective with a large sample size. The patient population included a large sample of men and women with representation of various adult ages and vitiligo extent. However, this study also had potential limitations. Measures of vitiligo extent were self-reported and were not clinically assessed. To address this limitation, we validated the questionnaire before posting it online.15 Invitation to participate in the survey was distributed by vitiligo support groups, which may have resulted in a selection bias toward participants with greater disease severity or with a poorer quality of life associated with vitiligo. Invitation to participate in this study was sent to members of vitiligo support groups, which allowed for recruitment of a large number of vitiligo patients despite a relatively low prevalence of disease in the general population. However, there are several challenges using this approach for nonvitiligo controls. Using participants with another dermatological disease as a control group may yield spurious results. Ideally, a large randomized sample of healthy participants with minimization of bias should be used for controls, which is an ambitious undertaking that was beyond the scope of this pilot study and will be the subject of future studies. Finally, this analysis found associations between stressors that occurred in the 2 years prior to vitiligo onset with symptomatic disease. We chose a broad interval for stressors because early vitiligo lesions may go unnoticed, making recognition of stressors occurring within days or weeks of onset infeasible. Further, we considered that chronic and prolonged stressors are more likely to have harmful consequences than acute stressors. Thus, stressors occurring within a more narrow interval (eg, 2 months) may not have the same association with vitiligo. Future studies are warranted to precisely identify the type and timing of psychological stressors preceding vitiligo onset.

Conclusion

In conclusion, there is a high prevalence of stressful life events preceding vitiligo, which may play an important role as disease triggers as well as predict the presence of intermittent abdominal cramping and itching or burning of skin. These associations indicate that screening of vitiligo patients for psychological stressors, abdominal cramping, and itching and/or burning of skin should be included in the routine assessment of vitiligo patients.

Appendix

1. Goronzy J, Weyand CM, Waase I. T cell subpopulations in inflammatory bowel disease: evidence for a defective induction of T8+ suppressor/cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Clin Exp Immunol. 1985;61:593-600.

2. Ongenae K, Van Geel N, Naeyaert JM. Evidence for an autoimmune pathogenesis of vitiligo. Pigment Cell Res. 2003;16:90-100.

3. Grimes PE, Morris R, Avaniss-Aghajani E, et al. Topical tacrolimus therapy for vitiligo: therapeutic responses and skin messenger RNA expression of proinflammatory cytokines. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:52-61.

4. Birol A, Kisa U, Kurtipek GS, et al. Increased tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-alpha) and interleukin 1 alpha (IL1-alpha) levels in the lesional skin of patients with nonsegmental vitiligo. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:992-993.

5. Moretti S, Spallanzani A, Amato L, et al. New insights into the pathogenesis of vitiligo: imbalance of epidermal cytokines at sites of lesions. Pigment Cell Res. 2002;15:87-92.

6. Zailaie MZ. Decreased proinflammatory cytokine production by peripheral blood mononuclear cells from vitiligo patients following aspirin treatment. Saudi Med J. 2005;26:799-805.

7. Basak PY, Adiloglu AK, Ceyhan AM, et al. The role of helper and regulatory T cells in the pathogenesis of vitiligo. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:256-260.

8. Kemp EH, Emhemad S, Akhtar S, et al. Autoantibodies against tyrosine hydroxylase in patients with non-segmental (generalised) vitiligo. Exp Dermatol. 2011;20:35-40.

9. Barisic´-Drusko V, Rucevic I. Trigger factors in childhood psoriasis and vitiligo. Coll Antropol. 2004;28:277-285.

10. Manolache L, Benea V. Stress in patients with alopecia areata and vitiligo. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:921-928.

11. Papadopoulos L, Bor R, Legg C, et al. Impact of life events on the onset of vitiligo in adults: preliminary evidence for a psychological dimension in aetiology. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1998;23:243-248.

12. Picardi A, Pasquini P, Cattaruzza MS, et al. Stressful life events, social support, attachment security and alexithymia in vitiligo. a case-control study. Psychother Psychosom. 2003;72:150-158.

13. Salzer BA, Schallreuter KU. Investigation of the personality structure in patients with vitiligo and a possible association with impaired catecholamine metabolism. Dermatology. 1995;190:109-115.

14. Al’Abadie MS, Senior HJ, Bleehen SS, et al. Neuropeptide and neuronal marker studies in vitiligo. Br J Dermatol. 1994;131:160-165.

15. Silverberg JI, Silverberg NB. Association between vitiligo extent and distribution and quality-of-life impairment. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:159-164.

16. Silverberg JI, Silverberg NB. Quality of life impairments in children and adolescents with vitiligo. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:309-318.

17. Kanwar AJ, Mahajan R, Parsad D. Effect of age at onset on disease characteristics in vitiligo. J Cutan Med Surg. 2013;17:253-258.

18. Hsieh FY, Bloch DA, Larsen MD. A simple method of sample size calculation for linear and logistic regression. Stat Med. 1998;17:1623-1634.

19. Manolache L, Petrescu-Seceleanu D, Benea V. Correlation of stressful events with onset of vitiligo in children. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:187-188.

20. Silverberg JI, Silverberg NB. Serum homocysteine as a biomarker of vitiligo vulgaris severity: a pilot study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:445-447.

21. Shaker OG, El-Tahlawi SM. Is there a relationship between homocysteine and vitiligo? a pilot study. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:720-724.

22. Balci DD, Yonden Z, Yenin JZ, et al. Serum homocysteine, folic acid and vitamin B12 levels in vitiligo. Eur J Dermatol. 2009;19:382-383.

23. Silverberg JI, Silverberg AI, Malka E, et al. A pilot study assessing the role of 25 hydroxy vitamin D levels in patients with vitiligo vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:937-941.

24. Jonasson T, Ohlin AK, Gottsater A, et al. Plasma homocysteine and markers for oxidative stress and inflammation in patients with coronary artery disease—a prospective randomized study of vitamin supplementation. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2005;43:628-634.

25. Cakmak SK, Gul U, Kilic C, et al. Homocysteine, vitamin B12 and folic acid levels in psoriasis patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:300-303.

26. Malerba M, Gisondi P, Radaeli A, et al. Plasma homocysteine and folate levels in patients with chronic plaque psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155:1165-1169.

27. Shastry S, James LR. Homocysteine-induced macrophage inflammatory protein-2 production by glomerular mesangial cells is mediated by PI3 Kinase and p38 MAPK. J Inflamm (Lond). 2009;6:27.

1. Goronzy J, Weyand CM, Waase I. T cell subpopulations in inflammatory bowel disease: evidence for a defective induction of T8+ suppressor/cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Clin Exp Immunol. 1985;61:593-600.

2. Ongenae K, Van Geel N, Naeyaert JM. Evidence for an autoimmune pathogenesis of vitiligo. Pigment Cell Res. 2003;16:90-100.

3. Grimes PE, Morris R, Avaniss-Aghajani E, et al. Topical tacrolimus therapy for vitiligo: therapeutic responses and skin messenger RNA expression of proinflammatory cytokines. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:52-61.

4. Birol A, Kisa U, Kurtipek GS, et al. Increased tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-alpha) and interleukin 1 alpha (IL1-alpha) levels in the lesional skin of patients with nonsegmental vitiligo. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:992-993.

5. Moretti S, Spallanzani A, Amato L, et al. New insights into the pathogenesis of vitiligo: imbalance of epidermal cytokines at sites of lesions. Pigment Cell Res. 2002;15:87-92.

6. Zailaie MZ. Decreased proinflammatory cytokine production by peripheral blood mononuclear cells from vitiligo patients following aspirin treatment. Saudi Med J. 2005;26:799-805.

7. Basak PY, Adiloglu AK, Ceyhan AM, et al. The role of helper and regulatory T cells in the pathogenesis of vitiligo. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:256-260.

8. Kemp EH, Emhemad S, Akhtar S, et al. Autoantibodies against tyrosine hydroxylase in patients with non-segmental (generalised) vitiligo. Exp Dermatol. 2011;20:35-40.

9. Barisic´-Drusko V, Rucevic I. Trigger factors in childhood psoriasis and vitiligo. Coll Antropol. 2004;28:277-285.

10. Manolache L, Benea V. Stress in patients with alopecia areata and vitiligo. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:921-928.

11. Papadopoulos L, Bor R, Legg C, et al. Impact of life events on the onset of vitiligo in adults: preliminary evidence for a psychological dimension in aetiology. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1998;23:243-248.

12. Picardi A, Pasquini P, Cattaruzza MS, et al. Stressful life events, social support, attachment security and alexithymia in vitiligo. a case-control study. Psychother Psychosom. 2003;72:150-158.

13. Salzer BA, Schallreuter KU. Investigation of the personality structure in patients with vitiligo and a possible association with impaired catecholamine metabolism. Dermatology. 1995;190:109-115.

14. Al’Abadie MS, Senior HJ, Bleehen SS, et al. Neuropeptide and neuronal marker studies in vitiligo. Br J Dermatol. 1994;131:160-165.

15. Silverberg JI, Silverberg NB. Association between vitiligo extent and distribution and quality-of-life impairment. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:159-164.

16. Silverberg JI, Silverberg NB. Quality of life impairments in children and adolescents with vitiligo. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:309-318.

17. Kanwar AJ, Mahajan R, Parsad D. Effect of age at onset on disease characteristics in vitiligo. J Cutan Med Surg. 2013;17:253-258.

18. Hsieh FY, Bloch DA, Larsen MD. A simple method of sample size calculation for linear and logistic regression. Stat Med. 1998;17:1623-1634.

19. Manolache L, Petrescu-Seceleanu D, Benea V. Correlation of stressful events with onset of vitiligo in children. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:187-188.

20. Silverberg JI, Silverberg NB. Serum homocysteine as a biomarker of vitiligo vulgaris severity: a pilot study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:445-447.

21. Shaker OG, El-Tahlawi SM. Is there a relationship between homocysteine and vitiligo? a pilot study. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:720-724.

22. Balci DD, Yonden Z, Yenin JZ, et al. Serum homocysteine, folic acid and vitamin B12 levels in vitiligo. Eur J Dermatol. 2009;19:382-383.

23. Silverberg JI, Silverberg AI, Malka E, et al. A pilot study assessing the role of 25 hydroxy vitamin D levels in patients with vitiligo vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:937-941.

24. Jonasson T, Ohlin AK, Gottsater A, et al. Plasma homocysteine and markers for oxidative stress and inflammation in patients with coronary artery disease—a prospective randomized study of vitamin supplementation. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2005;43:628-634.

25. Cakmak SK, Gul U, Kilic C, et al. Homocysteine, vitamin B12 and folic acid levels in psoriasis patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:300-303.

26. Malerba M, Gisondi P, Radaeli A, et al. Plasma homocysteine and folate levels in patients with chronic plaque psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155:1165-1169.

27. Shastry S, James LR. Homocysteine-induced macrophage inflammatory protein-2 production by glomerular mesangial cells is mediated by PI3 Kinase and p38 MAPK. J Inflamm (Lond). 2009;6:27.

Practice Points

- Psychological stressors (eg, loss of a loved one) that occurred within 2 years prior to vitiligo onset should be considered as potential disease triggers.

- Psychological stressors have been associated with symptoms of abdominal cramping and itching/burning in vitiligo patients but not disease extent or distribution.