User login

The Diagnosis: Idiopathic Guttate Hypomelanosis

A biopsy of the largest lesion from the left leg superior to the lateral malleolus was performed. Histopathologic examination revealed solar elastosis, diminished number of focal melanocytes and pigment within keratinocytes compared to uninvolved skin, and presence of hyperkeratosis with flattening of rete ridges. The clinical presentation along with histopathologic analysis confirmed a diagnosis of idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis (IGH). The lesions were treated with short-exposure cryotherapy, which resulted in partial repigmentation after several treatments.

Idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis is a common but underreported condition in elderly patients that usually presents with small, discrete, asymptomatic, hypopigmented macules. The frequency of IGH increases with age.1 Frequency of the condition is much lower in patients aged 21 to 30 years and does not exceed 7%. Lesions of IGH have a predilection for sun-exposed areas such as the arms and legs but rarely can be seen on the face and trunk. Facial lesions of IGH are more frequently reported in women.1 The size of lesions can be up to 1.5 cm in diameter. The condition generally is self-limited, but some patients may express aesthetic concerns. Rare cases of IGH in children have been associated with prolonged sun exposure.2

The etiology of IGH is unknown but an association with sun exposure has been noted. Patients with IGH frequently show other signs of photoaging, such as numerous seborrheic keratoses, solar lentigines, xeroses, freckles, and actinic keratoses.1 Short-term exposure to UVB radiation and psoralen plus UVA therapy has been shown to cause IGH in patients with chronic diseases such as mycosis fungoides.3-5 One small study that examined renal transplant recipients determined an association between HLA-DQ3 antigens and IGH, whereas HLA-DR8 antigens were not identified in any patients with IGH, indicating it may have some advantage in preventing the development of IGH.6 Shin et al1 reported that IGH was prevalent among patients who regularly traumatized their skin by scrubbing.

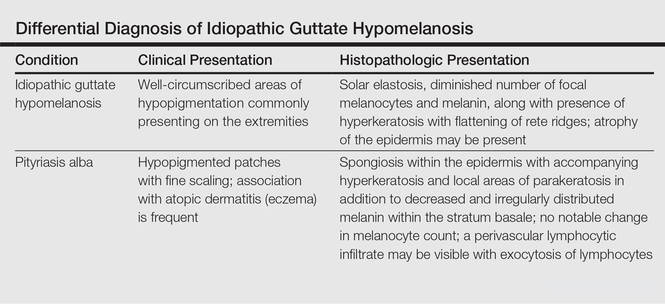

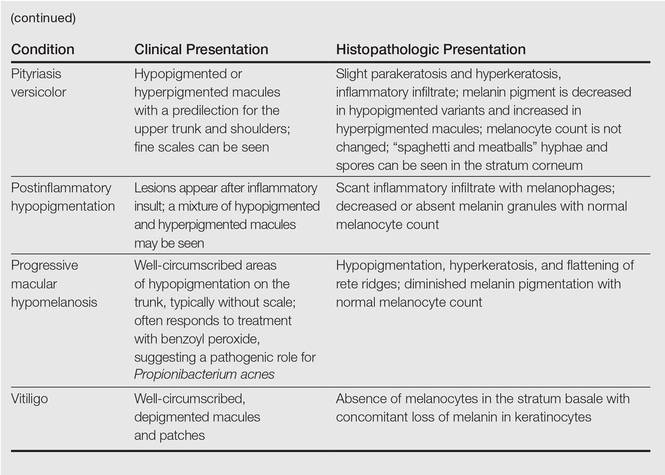

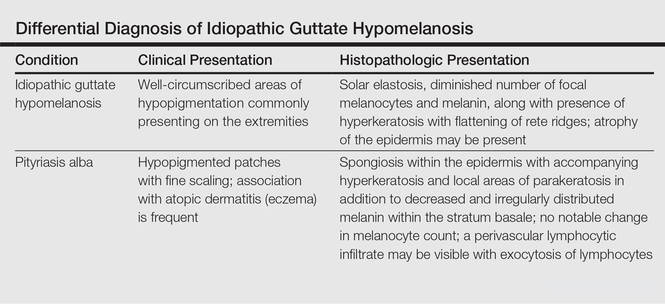

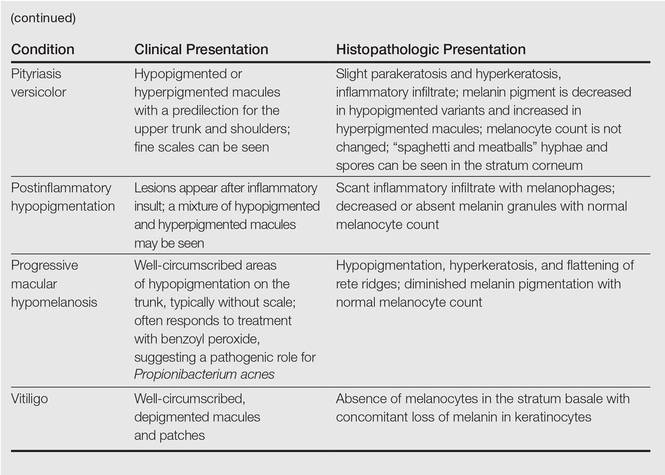

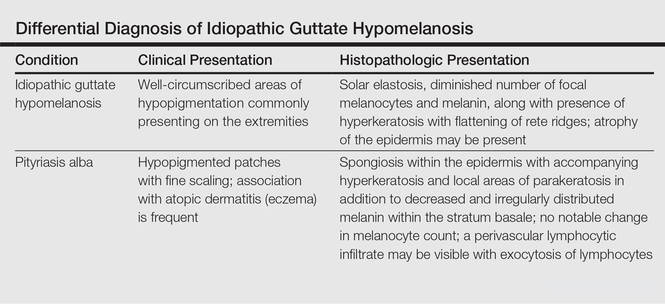

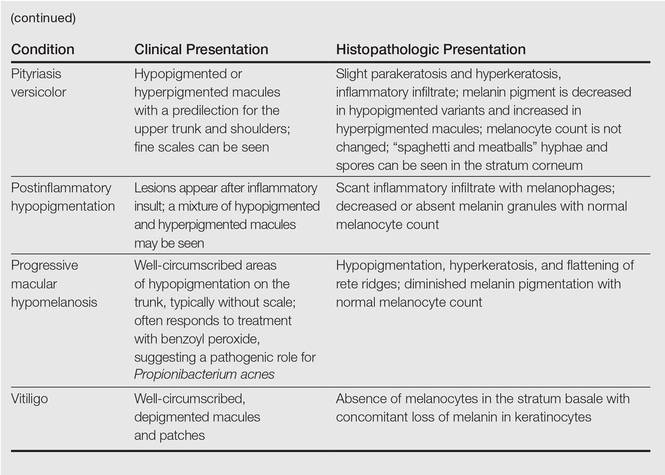

Clinically, IGH should be differentiated from other conditions characterized by hypopigmentation, such as pityriasis alba, pityriasis versicolor, postinflammatory hypopigmentation, progressive macular hypomelanosis, and vitiligo. Aside from clinical examination, histopathologic studies are helpful in making a definitive diagnosis. The differential diagnosis of IGH is presented in the Table.

Histopathology of IGH lesions usually reveals slight atrophy of the epidermis with flattening of rete ridges and concomitant hyperkeratosis. A thickened stratum granulosum also has been noted in lesions of IGH.2 The diminished number of melanocytes and melanin pigment granules along with hyperkeratosis both appear to contribute to the hypopigmentation noted in IGH.7 Ultrastructural studies of lesions of IGH can confirm melanocytic degeneration and a decreased number of melanosomes in melanocytes and keratinocytes.2,8

There is no uniformly effective treatment of IGH. Topical application of tacrolimus and tretinoin have shown efficacy in repigmenting IGH lesions.8,9 Short-exposure cryotherapy with a duration of 3 to 5 seconds, localized chemical peels, and/or local dermabrasion can be helpful.10-12 CO2 lasers also have demonstrated promising results.13

- Shin MK, Jeong KH, Oh IH, et al. Clinical features of idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis in 646 subjects and association with other aspects of photoaging. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:798-805.

- Kim SK, Kim EH, Kang HY, et al. Comprehensive understanding of idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis: clinical and histopathological correlation. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:162-166.

- Friedland R, David M, Feinmesser M, et al. Idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis-like lesions in patients with mycosis fungoides: a new adverse effect of phototherapy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:1026-1030.

- Kaya TI, Yazici AC, Tursen U, et al. Idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis: idiopathic or ultraviolet induced? Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2005;21:270-271.

- Loquai C, Metze D, Nashan D, et al. Confetti-like lesions with hyperkeratosis: a novel ultraviolet-induced hypomelanotic disorder? Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:190-193.

- Arrunategui A, Trujillo RA, Marulanda MP, et al. HLA-DQ3 is associated with idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis, whereas HLA-DR8 is not, in a group of renal transplant patients. Int J Dermatol. 2002;41:744-747.

- Wallace ML, Grichnik JM, Prieto VG, et al. Numbers and differentiation status of melanocytes in idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis. J Cutan Pathol. 1998;25:375-379.

- Ortonne JP, Perrot H. Idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis. ultrastructural study. Arch Dermatol. 1980;116:664-668.

- Rerknimitr P, Disphanurat W, Achariyakul M. Topical tacrolimus significantly promotes repigmentation in idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:460-464.

- Pagnoni A, Kligman AM, Sadiq I, et al. Hypopigmented macules of photodamaged skin and their treatment with topical tretinoin. Acta Derm Venereol. 1999;79:305-310.

- Kumarasinghe SP. 3-5 second cryotherapy is effective in idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis. J Dermatol. 2004;31:457-459.

- Hexsel DM. Treatment of idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis by localized superficial dermabrasion. Dermatol Surg. 1999;25:917-918.

- Shin J, Kim M, Park SH, et al. The effect of fractional carbon dioxide lasers on idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis: a preliminary study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:e243-e246.

The Diagnosis: Idiopathic Guttate Hypomelanosis

A biopsy of the largest lesion from the left leg superior to the lateral malleolus was performed. Histopathologic examination revealed solar elastosis, diminished number of focal melanocytes and pigment within keratinocytes compared to uninvolved skin, and presence of hyperkeratosis with flattening of rete ridges. The clinical presentation along with histopathologic analysis confirmed a diagnosis of idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis (IGH). The lesions were treated with short-exposure cryotherapy, which resulted in partial repigmentation after several treatments.

Idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis is a common but underreported condition in elderly patients that usually presents with small, discrete, asymptomatic, hypopigmented macules. The frequency of IGH increases with age.1 Frequency of the condition is much lower in patients aged 21 to 30 years and does not exceed 7%. Lesions of IGH have a predilection for sun-exposed areas such as the arms and legs but rarely can be seen on the face and trunk. Facial lesions of IGH are more frequently reported in women.1 The size of lesions can be up to 1.5 cm in diameter. The condition generally is self-limited, but some patients may express aesthetic concerns. Rare cases of IGH in children have been associated with prolonged sun exposure.2

The etiology of IGH is unknown but an association with sun exposure has been noted. Patients with IGH frequently show other signs of photoaging, such as numerous seborrheic keratoses, solar lentigines, xeroses, freckles, and actinic keratoses.1 Short-term exposure to UVB radiation and psoralen plus UVA therapy has been shown to cause IGH in patients with chronic diseases such as mycosis fungoides.3-5 One small study that examined renal transplant recipients determined an association between HLA-DQ3 antigens and IGH, whereas HLA-DR8 antigens were not identified in any patients with IGH, indicating it may have some advantage in preventing the development of IGH.6 Shin et al1 reported that IGH was prevalent among patients who regularly traumatized their skin by scrubbing.

Clinically, IGH should be differentiated from other conditions characterized by hypopigmentation, such as pityriasis alba, pityriasis versicolor, postinflammatory hypopigmentation, progressive macular hypomelanosis, and vitiligo. Aside from clinical examination, histopathologic studies are helpful in making a definitive diagnosis. The differential diagnosis of IGH is presented in the Table.

Histopathology of IGH lesions usually reveals slight atrophy of the epidermis with flattening of rete ridges and concomitant hyperkeratosis. A thickened stratum granulosum also has been noted in lesions of IGH.2 The diminished number of melanocytes and melanin pigment granules along with hyperkeratosis both appear to contribute to the hypopigmentation noted in IGH.7 Ultrastructural studies of lesions of IGH can confirm melanocytic degeneration and a decreased number of melanosomes in melanocytes and keratinocytes.2,8

There is no uniformly effective treatment of IGH. Topical application of tacrolimus and tretinoin have shown efficacy in repigmenting IGH lesions.8,9 Short-exposure cryotherapy with a duration of 3 to 5 seconds, localized chemical peels, and/or local dermabrasion can be helpful.10-12 CO2 lasers also have demonstrated promising results.13

The Diagnosis: Idiopathic Guttate Hypomelanosis

A biopsy of the largest lesion from the left leg superior to the lateral malleolus was performed. Histopathologic examination revealed solar elastosis, diminished number of focal melanocytes and pigment within keratinocytes compared to uninvolved skin, and presence of hyperkeratosis with flattening of rete ridges. The clinical presentation along with histopathologic analysis confirmed a diagnosis of idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis (IGH). The lesions were treated with short-exposure cryotherapy, which resulted in partial repigmentation after several treatments.

Idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis is a common but underreported condition in elderly patients that usually presents with small, discrete, asymptomatic, hypopigmented macules. The frequency of IGH increases with age.1 Frequency of the condition is much lower in patients aged 21 to 30 years and does not exceed 7%. Lesions of IGH have a predilection for sun-exposed areas such as the arms and legs but rarely can be seen on the face and trunk. Facial lesions of IGH are more frequently reported in women.1 The size of lesions can be up to 1.5 cm in diameter. The condition generally is self-limited, but some patients may express aesthetic concerns. Rare cases of IGH in children have been associated with prolonged sun exposure.2

The etiology of IGH is unknown but an association with sun exposure has been noted. Patients with IGH frequently show other signs of photoaging, such as numerous seborrheic keratoses, solar lentigines, xeroses, freckles, and actinic keratoses.1 Short-term exposure to UVB radiation and psoralen plus UVA therapy has been shown to cause IGH in patients with chronic diseases such as mycosis fungoides.3-5 One small study that examined renal transplant recipients determined an association between HLA-DQ3 antigens and IGH, whereas HLA-DR8 antigens were not identified in any patients with IGH, indicating it may have some advantage in preventing the development of IGH.6 Shin et al1 reported that IGH was prevalent among patients who regularly traumatized their skin by scrubbing.

Clinically, IGH should be differentiated from other conditions characterized by hypopigmentation, such as pityriasis alba, pityriasis versicolor, postinflammatory hypopigmentation, progressive macular hypomelanosis, and vitiligo. Aside from clinical examination, histopathologic studies are helpful in making a definitive diagnosis. The differential diagnosis of IGH is presented in the Table.

Histopathology of IGH lesions usually reveals slight atrophy of the epidermis with flattening of rete ridges and concomitant hyperkeratosis. A thickened stratum granulosum also has been noted in lesions of IGH.2 The diminished number of melanocytes and melanin pigment granules along with hyperkeratosis both appear to contribute to the hypopigmentation noted in IGH.7 Ultrastructural studies of lesions of IGH can confirm melanocytic degeneration and a decreased number of melanosomes in melanocytes and keratinocytes.2,8

There is no uniformly effective treatment of IGH. Topical application of tacrolimus and tretinoin have shown efficacy in repigmenting IGH lesions.8,9 Short-exposure cryotherapy with a duration of 3 to 5 seconds, localized chemical peels, and/or local dermabrasion can be helpful.10-12 CO2 lasers also have demonstrated promising results.13

- Shin MK, Jeong KH, Oh IH, et al. Clinical features of idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis in 646 subjects and association with other aspects of photoaging. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:798-805.

- Kim SK, Kim EH, Kang HY, et al. Comprehensive understanding of idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis: clinical and histopathological correlation. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:162-166.

- Friedland R, David M, Feinmesser M, et al. Idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis-like lesions in patients with mycosis fungoides: a new adverse effect of phototherapy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:1026-1030.

- Kaya TI, Yazici AC, Tursen U, et al. Idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis: idiopathic or ultraviolet induced? Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2005;21:270-271.

- Loquai C, Metze D, Nashan D, et al. Confetti-like lesions with hyperkeratosis: a novel ultraviolet-induced hypomelanotic disorder? Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:190-193.

- Arrunategui A, Trujillo RA, Marulanda MP, et al. HLA-DQ3 is associated with idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis, whereas HLA-DR8 is not, in a group of renal transplant patients. Int J Dermatol. 2002;41:744-747.

- Wallace ML, Grichnik JM, Prieto VG, et al. Numbers and differentiation status of melanocytes in idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis. J Cutan Pathol. 1998;25:375-379.

- Ortonne JP, Perrot H. Idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis. ultrastructural study. Arch Dermatol. 1980;116:664-668.

- Rerknimitr P, Disphanurat W, Achariyakul M. Topical tacrolimus significantly promotes repigmentation in idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:460-464.

- Pagnoni A, Kligman AM, Sadiq I, et al. Hypopigmented macules of photodamaged skin and their treatment with topical tretinoin. Acta Derm Venereol. 1999;79:305-310.

- Kumarasinghe SP. 3-5 second cryotherapy is effective in idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis. J Dermatol. 2004;31:457-459.

- Hexsel DM. Treatment of idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis by localized superficial dermabrasion. Dermatol Surg. 1999;25:917-918.

- Shin J, Kim M, Park SH, et al. The effect of fractional carbon dioxide lasers on idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis: a preliminary study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:e243-e246.

- Shin MK, Jeong KH, Oh IH, et al. Clinical features of idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis in 646 subjects and association with other aspects of photoaging. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:798-805.

- Kim SK, Kim EH, Kang HY, et al. Comprehensive understanding of idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis: clinical and histopathological correlation. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:162-166.

- Friedland R, David M, Feinmesser M, et al. Idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis-like lesions in patients with mycosis fungoides: a new adverse effect of phototherapy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:1026-1030.

- Kaya TI, Yazici AC, Tursen U, et al. Idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis: idiopathic or ultraviolet induced? Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2005;21:270-271.

- Loquai C, Metze D, Nashan D, et al. Confetti-like lesions with hyperkeratosis: a novel ultraviolet-induced hypomelanotic disorder? Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:190-193.

- Arrunategui A, Trujillo RA, Marulanda MP, et al. HLA-DQ3 is associated with idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis, whereas HLA-DR8 is not, in a group of renal transplant patients. Int J Dermatol. 2002;41:744-747.

- Wallace ML, Grichnik JM, Prieto VG, et al. Numbers and differentiation status of melanocytes in idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis. J Cutan Pathol. 1998;25:375-379.

- Ortonne JP, Perrot H. Idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis. ultrastructural study. Arch Dermatol. 1980;116:664-668.

- Rerknimitr P, Disphanurat W, Achariyakul M. Topical tacrolimus significantly promotes repigmentation in idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:460-464.

- Pagnoni A, Kligman AM, Sadiq I, et al. Hypopigmented macules of photodamaged skin and their treatment with topical tretinoin. Acta Derm Venereol. 1999;79:305-310.

- Kumarasinghe SP. 3-5 second cryotherapy is effective in idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis. J Dermatol. 2004;31:457-459.

- Hexsel DM. Treatment of idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis by localized superficial dermabrasion. Dermatol Surg. 1999;25:917-918.

- Shin J, Kim M, Park SH, et al. The effect of fractional carbon dioxide lasers on idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis: a preliminary study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:e243-e246.

A 58-year-old man presented with disseminated, hypopigmented, asymptomatic lesions on the right arm (top) and left leg (bottom) that had been present for approximately 6 years. The patient reported that the lesions had become more visible and greater in number within the last year. Multiple circular hypopigmented macules of various sizes ranging from 1 to 3 mm in diameter were identified. No scaling was seen. Physical examination was otherwise unremarkable.