User login

Renal disease can play a large role in altering the pharmacokinetics of medications, especially in elimination or clearance and plasma protein binding. Specifically, renal impairment decreases the plasma protein binding secondary to decreased albumin and retention of urea, which competes with medications to bind to the protein.1

Electrolyte shifts—which could lead to a fatal arrhythmia—are common among patients with renal impairment. The risk can be further increased in this population if a patient is taking a medication that can induce arrhythmia. If a drug is primarily excreted by the kidneys, elimination could be significantly altered, especially if the medication has active metabolites.1

Normal renal function is defined as an estimated creatinine clearance (eCrCl) of >80 mL/min. Renal impairment is classified as:

- mild: eCrCl, 51 to 80 mL/min

- moderate: eCrCl, 31 to 50 mL/min

- severe: eCrCl, ≤30 mL/min

- end-stage renal disease (ESRD): eCrCl, <10 mL/min.2

Overall, there is minimal information about the effects of renal disease on psychotropic therapy; our goal here is to summarize available data. We have created quick reference tables highlighting psychotropics that have renal dosing recommendations based on manufacturers’ package inserts.

Antipsychotics

First-generation antipsychotics (FGAs). Dosage adjustments based on renal function are not required for any FGA, according to manufacturers’ package inserts. Some of these antipsychotics are excreted in urine, but typically as inactive metabolites.

Although there are no dosage recommendations based on renal function provided by the labeling, there has been concern about the use of some FGAs in patients with renal impairment. Specifically, concerns center around the piperidine phenothiazines (thioridazine and mesoridazine) because of the increased risk of electrocardiographic changes and medication-induced arrhythmias in renal disease due to electrolyte imbalances.3,4 Additionally, there is case evidence5 that phenothiazine antipsychotics could increase a patient’s risk for hypotension in chronic renal failure. Haloperidol is considered safe in renal disease because <1% of the medication is excreted unchanged through urine.6

Second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs). Overall, SGAs are considered safe in patients with renal disease. Most SGAs undergo extensive hepatic metabolism before excretion, allowing them to be used safely in patients with renal disease.

Sheehan et al7 analyzed the metabolism and excretion of SGAs, evaluating 8 antipsychotics divided into 4 groups: (1) excretion primarily as an unchanged drug in urine, (2) changed drug in urine, (3) changed drug in feces, (4) and unchanged drug in feces.

- Paliperidone was found to be primarily excreted as an unchanged drug in urine.

- Clozapine, iloperidone, olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone all were found to be primarily excreted as a changed drug in urine.

- Aripiprazole and ziprasidone were found to be primarily excreted as a changed drug in feces.

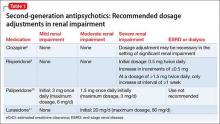

The manufacturers’ package inserts for clozapine, paliperidone, risperidone, and lurasidone have recommended dosage adjustments based on renal function (Table 1).8-11

Ziprasidone. Although ziprasidone does not have a recommended renal dosage adjustment, caution is recommended because of the risk of electrocardiographic changes and potential for medication-induced arrhythmias in patients with electrolyte disturbances secondary to renal disease. A single-dosage study of ziprasidone by Aweeka et al12 demonstrated that the pharmacokinetics of ziprasidone are unchanged in patients with renal impairment.

Asenapine. A small study by Peeters et al13 evaluated the pharmacokinetics of asenapine in hepatic and renal impairment and found no clinically relevant changes in asenapine’s pharmacokinetics among patients with any level of renal impairment compared with patients with normal renal function.

Aripiprazole. Mallikaarjun et al14 completed a small study evaluating the pharmacokinetics of aripiprazole in patients with renal impairment. They found that the pharmacokinetics of aripiprazole in these patients is no different than it is in patients with normal renal function who are taking aripiprazole.

Quetiapine. Thyrum et al15 conducted a similar study with quetiapine, which showed no significant difference detected in the pharmacokinetics of quetiapine in patients with renal impairment. Additionally, quetiapine had no negative effect on patients’ creatinine clearance.

Lurasidone. During clinical trials of lurasidone in patients with mild, moderate, and severe renal impairment, the mean Cmax and area under the curve was higher compared with healthy patients, which led to recommended dosage adjustments in patients with renal impairment.11

As mentioned above, renal impairment decreases the protein binding percentage of medications. Hypothetically, the greater the protein binding, the lower the recommended dosage in patients with renal impairment because the free or unbound form correlates with efficacy and toxicity. Most FGAs and SGAs have the protein-binding characteristic of ≥90%.16 Although it seems this characteristic should result in recommendations to adjust dosage based on renal function, the various pharmacokinetic studies of antipsychotics have not shown this factor to play a role in the manufacturers’ recommendations.

Antidepressants

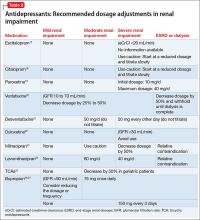

Comorbidity rates of depression in patients with renal disease range from 14% to 30%, making use of antidepressants in renal disease common.4 Antidepressants primarily are metabolized hepatically and excreted renally. Table 217-27 summarizes recommended dosing adjustments for antidepressants.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.Escitalopram is the (S)-enantiomer of the racemic antidepressant citalopram, both of which have been shown to decrease renal clearance in patients with mild or moderate renal impairment. However, according to the package insert, no dosage adjustments are needed.17 No extensive studies have been conducted on escitalopram or citalopram, but each should be initiated at a reduced dosage and the titration schedule should be prolonged in patients with severe renal impairment or ESRD.17,18

The plasma concentration of paroxetine has been noted to be elevated in patients with severe renal impairment, and the half-life can increase to nearly 50%.4 Paroxetine should be initiated at 10 mg/d, and then titrated slowly in patients with severe renal impairment.19,28

The pharmacokinetics of fluoxetine are unchanged in any stage of renal impairment. Patients in active renal dialysis report good tolerability and efficacy.4

Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors. Venlafaxine and its metabolite O-desmethylvenlafaxine (desvenlafaxine) are primarily excreted via renal elimination. Studies have shown that mild renal impairment can have an effect on plasma levels of the drug, and that moderate or severe impairment can increase the venlafaxine plasma concentration. According to the package insert, a dosage reduction of 50% is recommended for desvenlafaxine and venlafaxine.20,21

No significant pharmacokinetic changes with duloxetine have been noted in patients with mild or moderate renal impairment.22 However, duloxetine’s major metabolites, which are excreted renally, have been measured to be as much as 7 to 9 times higher in patients with ESRD compared with healthy subjects; therefore, it is recommended to avoid duloxetine in patients with severe renal disease.4,22 Our review of the literature produced limited recommendations on dosing milnacipran and its enantiomer levomilnacipran in renally impaired patients. The milnacipran package insert cautions its use in moderate renal impairment and recommends a 50% dosage reduction to 100 mg/d (50 mg twice daily) in patients with severe renal impairment.23 Dosage recommendations for levomilnacipran are 80 mg/d for moderate renal impairment and 40 mg/d for severe impairment. Both agents have relative contraindications for ESRD.23,24

Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) are predominantly metabolized hepatically, glucuronidated, and then eliminated renally. Desipramine, imipramine, and nortriptyline have nonspecific package insert recommendations for modified dosing in geriatric patients because of an age-related decrease in renal clearance.29-31 Review articles assert that elevated glucuronidated metabolites could increase patients’ sensitivity to side effects of TCAs. Because of concerns regarding elevated glucuronidated metabolites, it has been proposed to initiate TCAs at a low dosage, titrate slowly, and maintain the lowest effective dosage in patients with renal impairment.25

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) and other antidepressants. The package inserts of the MAOIs isocarboxazid, phenelzine, selegiline, and tranylcypromine provide limited data and dosage recommendations for use in the context of renal impairment.32-36 Isocarboxazid should not be used in patients with severe renal impairment, according to the prescribing information.32 There are no dosing recommendations for transdermal selegiline in mild, moderate, or severe renal impairment.37 Extra vigilance is required when using MAOIs in patients with renal disease because of an increased risk of dialysis-induced hypotension (orthostatic hypotension is a common adverse effect of MAOIs).38

Bupropion is primarily metabolized hepatically to the active metabolite hydroxybupropion. Plasma levels of this metabolite at steady state are reported to be 10 times greater than bupropion’s concentration levels in healthy subjects; plasma levels are further increased in mild renal impairment.26 Hydroxybupropion is not dialyzable, which can increase the risk of toxicity with bupropion therapy in patients with renal impairment.3 If bupropion effectively treats depression in patients with declining renal function, specifically severe renal impairment and ESRD, then decreasing the dosage to 150 mg every 3 days is recommended to lessen the risk of toxicity. 27

Mood stabilizers

Lithium has the most published literature on dosing adjustments with renal impairment. Many providers are inclined to discontinue lithium use at the first sign of any change in renal function; however, monitoring, prevention, and treatment guidelines for lithium are well established after many years of research and clinical use.39 Lithium’s prescribing information recommends dosage adjustment in mild to moderate renal impairment and lists severe renal impairment and ESRD as relative contraindications.40

A recent study proposes more assertive use of lithium in patients with renal impairment of any severity. Rej et al41 compared continued lithium treatment to discontinuing treatment in geriatric patients with chronic renal failure, and reported (1) a statistically insignificant difference in renal function between groups at 2 years and (2) a “trending decrease” in renal function at 5 years in the lithium treatment group. With closely monitored plasma levels, lithium treatment is considered a workable treatment for patients with moderate renal impairment when mood stabilizer treatment has been effective.42

Lamotrigine and its main glucuronidated metabolite, lamotrigine-2N-glucuronide (L-2-N-G), are primarily excreted renally. In severe renal impairment and ESRD, the L-2-N-G levels are elevated but are not pharmacologically active and, therefore, do not affect plasma concentration or efficacy of lamotrigine.43 Although data are limited regarding the use of lamotrigine in severe renal impairment and ESRD, Kaufman44 reported a 17% to 20% decrease in concentration after dialysis—suggesting that post-dialysis titration might be needed in these patients.

Oxcarbazepine is metabolized by means of cytosolic enzymes in the liver to its primary pharmacologically active metabolite, 10-monohydroxy, which is further metabolized via glucuronidation and then renally excreted. There are no dosage adjustment recommendations for patients with an eCrCl >30 mL/min.45 Rouan et al46 suggest initiating oxcarbazepine at 50% of the recommended dosage and following a longer titration schedule in patients with an eCrCl 10 to 30 mL/min. No dosing suggestions for severe renal impairment and ESRD were provided because of study limitations; however, the general recommendation for psychotropic agents in patients in a severe stage of renal impairment is dosage reduction with close monitoring.46

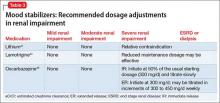

Table 341,44,46 summarizes dosage adjustments for mood stabilizers in patients with renal impairment.

1. Levy G. Pharmacokinetics in renal disease. Am J Med. 1977;62(4):461-465.

2. Preskorn SH. Clinically important differences in the pharmacokinetics of the ten newer “atypical” antipsychotics: part 3. Effects of renal and hepatic impairment. J Psychiatr Pract. 2012;18(6):430-437.

3. Cohen LM, Tessier EG, Germain MJ, et al. Update on psychotropic medication use in renal disease. Psychosomatics. 2004;45(1):34-48.

4. Baghdady NT, Banik S, Swartz SA, et al. Psychotropic drugs and renal failure: translating the evidence for clinical practice. Adv Ther. 2009;26(4):404-424.

5. Sheehan J, White A, Wilson R. Hazards of phenothiazines in chronic renal failure. Ir Med J. 1982;75(9):335.

6. Haloperidol [monograph]. In: Micromedex Drugdex [online database]. Greenwood Village, CO: Truven Health Analytics. Accessed December 17, 2014.

7. Sheehan JJ, Sliwa JK, Amatniek JC, et al. Atypical antipsychotic metabolism and excretion. Curr Drug Metab. 2010;11(6):516-525.

8. Clozaril [package insert]. East Hanover, NJ: Novartis Pharmaceuticals; 2014.

9. Risperdal [package insert]. Titusville, NJ: Janssen Pharmaceuticals; 2014.

10. Invega [package insert]. Titusville, NJ: Janssen Pharmaceuticals; 2014.

11. Latuda [package insert]. Fort Lee, NJ: Sunovion Pharmaceuticals; 2013.

12. Aweeka F, Jayesekara D, Horton M, et al. The pharmacokinetics of ziprasidone in subjects with normal and impaired renal function. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;49(suppl 1):27S-33S.

13. Peeters P, Bockbrader H, Spaans E, et al. Asenapine pharmacokinetics in hepatic and renal impairment. Clin Pharmacol. 2011;50(7):471-481.

14. Mallikaarjun S, Shoaf SE, Boulton DW, et al. Effects of hepatic or renal impairment on the pharmacokinetics of aripiprazole. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2008;47(8):533-542.

15. Thyrum PT, Wong YW, Yeh C. Single-dose pharmacokinetics of quetiapine in subjects with renal or hepatic impairment. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2000;24(4):521-533.

16. Lexi-Drugs. Lexicomp. Hudson, OH: Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. http://online.lexi.com. Accessed May 28, 2015.

17. Lexapro [package insert]. Forest Pharmaceuticals, Inc.: St. Louis, MO; 2014.

18. Celexa [package insert]. Forest Pharmaceuticals, Inc.: St. Louis, MO; 2014.

19. Paxil [package insert]. Research Triangle Park, NC: GlaxoSmithKline; 2008.

20. Effexor [package insert]. Philadelphia, PA: Wyeth Pharmaceuticals Inc.; 2010.

21. Pristiq [package insert]. Philadelphia, PA: Wyeth Pharmaceuticals Inc.; 2014.

22. Cymbalta [package insert]. Indianapolis, IN: Lilly USA, LLC; 2014.

23. Savella [package insert]. St. Louis, MO: Forest Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; 2013.

24. Fetzima [package insert]. St. Louis, MO: Forest Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; 2014.

25. Kurella M, Bennett WM, Chertow GM. Analgesia in patients with ESRD: a review of available evidence. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;42(2):217-228.

26. Wellbutrin [package insert]. Research Triangle Park, NC: GlaxoSmithKline; 2014.

27. Worrall SP, Almond MK, Dhillon S. Pharmacokinetics of bupropion and its metabolites in haemodialysis patients who smoke. A single dose study. Nephron Clin Pract. 2004;97(3):c83-c89.

28. Nagler EV, Webster AC, Vanholder R, et al. Antidepressants for depression in stage 3-5 chronic kidney disease: a systematic review of pharmacokinetics, efficacy and safety with recommendations by European Renal Best Practice (ERBP). Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27(10):3736-3745.

29. Norpramin. [package insert] Bridgewater, NJ: Sanofi-Aventis U.S. LLC; 2014.

30. Tofranil [package insert]. Hazelwood, MO: Mallinckrodt Inc.; 2014.

31. Pamelor [package insert]. Hazelwood, MO: Mallinckrodt Inc.; 2014.

32. Marplan [package insert]. Parsippany, NJ: Validus Pharmaceuticals, LLC; 2012.

33. Nardil [package insert]. New York, NY: Parke-Davis Division of Pfizer Inc.; 2009.

34. EMSAM [package insert]. Morgantown, WV: Mylan Specialty, L.P.; 2014.

35. Eldepryl [package insert]. Morgantown, WV: Somerset Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; 2009.

36. Parnate [package insert]. Research Triangle Park, NC: GlaxoSmithKline; 2008.

37. Culpepper L. Reducing the burden of difficult-to-treat major depressive disorder: revisiting monoamine oxidase inhibitor therapy. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2013;15(5). doi: 10.4088/PCC.13r01515.

38. Tossani E, Cassano P, Fava M. Depression and renal disease. Semin Dial. 2005;18(2):73-81.

39. Young AH, Hammond JM. Lithium in mood disorders: increasing evidence base, declining use? Br J Psychiatry. 2007;191:474-476.

40. Eskalith [package insert]. Research Triangle Park, NC: GlaxoSmithKline; 2003.

41. Rej S, Looper K, Segal M. The effect of serum lithium levels on renal function in geriatric outpatients: a retrospective longitudinal study. Drugs Aging. 2013;30(6):409-415.

42. Malhi GS, Tanious M, Das P, et al. The science and practice of lithium therapy. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2012;46(3):192-211.

43. Lamictal [package insert]. Research Triangle Park, NC: GlaxoSmithKline; 2014.

44. Kaufman KR. Lamotrigine and hemodialysis in bipolar disorder: case analysis of dosing strategy with literature review. Bipolar Disord. 2010;12(4):446-449.

45. Trileptal [package insert]. East Hanover, NJ: Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; 2014.

46. Rouan MC, Lecaillon JB, Godbillon J, et al. The effect of renal impairment on the pharmacokinetics of oxcarbazepine and its metabolites. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1994;47(2):161-167.

Renal disease can play a large role in altering the pharmacokinetics of medications, especially in elimination or clearance and plasma protein binding. Specifically, renal impairment decreases the plasma protein binding secondary to decreased albumin and retention of urea, which competes with medications to bind to the protein.1

Electrolyte shifts—which could lead to a fatal arrhythmia—are common among patients with renal impairment. The risk can be further increased in this population if a patient is taking a medication that can induce arrhythmia. If a drug is primarily excreted by the kidneys, elimination could be significantly altered, especially if the medication has active metabolites.1

Normal renal function is defined as an estimated creatinine clearance (eCrCl) of >80 mL/min. Renal impairment is classified as:

- mild: eCrCl, 51 to 80 mL/min

- moderate: eCrCl, 31 to 50 mL/min

- severe: eCrCl, ≤30 mL/min

- end-stage renal disease (ESRD): eCrCl, <10 mL/min.2

Overall, there is minimal information about the effects of renal disease on psychotropic therapy; our goal here is to summarize available data. We have created quick reference tables highlighting psychotropics that have renal dosing recommendations based on manufacturers’ package inserts.

Antipsychotics

First-generation antipsychotics (FGAs). Dosage adjustments based on renal function are not required for any FGA, according to manufacturers’ package inserts. Some of these antipsychotics are excreted in urine, but typically as inactive metabolites.

Although there are no dosage recommendations based on renal function provided by the labeling, there has been concern about the use of some FGAs in patients with renal impairment. Specifically, concerns center around the piperidine phenothiazines (thioridazine and mesoridazine) because of the increased risk of electrocardiographic changes and medication-induced arrhythmias in renal disease due to electrolyte imbalances.3,4 Additionally, there is case evidence5 that phenothiazine antipsychotics could increase a patient’s risk for hypotension in chronic renal failure. Haloperidol is considered safe in renal disease because <1% of the medication is excreted unchanged through urine.6

Second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs). Overall, SGAs are considered safe in patients with renal disease. Most SGAs undergo extensive hepatic metabolism before excretion, allowing them to be used safely in patients with renal disease.

Sheehan et al7 analyzed the metabolism and excretion of SGAs, evaluating 8 antipsychotics divided into 4 groups: (1) excretion primarily as an unchanged drug in urine, (2) changed drug in urine, (3) changed drug in feces, (4) and unchanged drug in feces.

- Paliperidone was found to be primarily excreted as an unchanged drug in urine.

- Clozapine, iloperidone, olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone all were found to be primarily excreted as a changed drug in urine.

- Aripiprazole and ziprasidone were found to be primarily excreted as a changed drug in feces.

The manufacturers’ package inserts for clozapine, paliperidone, risperidone, and lurasidone have recommended dosage adjustments based on renal function (Table 1).8-11

Ziprasidone. Although ziprasidone does not have a recommended renal dosage adjustment, caution is recommended because of the risk of electrocardiographic changes and potential for medication-induced arrhythmias in patients with electrolyte disturbances secondary to renal disease. A single-dosage study of ziprasidone by Aweeka et al12 demonstrated that the pharmacokinetics of ziprasidone are unchanged in patients with renal impairment.

Asenapine. A small study by Peeters et al13 evaluated the pharmacokinetics of asenapine in hepatic and renal impairment and found no clinically relevant changes in asenapine’s pharmacokinetics among patients with any level of renal impairment compared with patients with normal renal function.

Aripiprazole. Mallikaarjun et al14 completed a small study evaluating the pharmacokinetics of aripiprazole in patients with renal impairment. They found that the pharmacokinetics of aripiprazole in these patients is no different than it is in patients with normal renal function who are taking aripiprazole.

Quetiapine. Thyrum et al15 conducted a similar study with quetiapine, which showed no significant difference detected in the pharmacokinetics of quetiapine in patients with renal impairment. Additionally, quetiapine had no negative effect on patients’ creatinine clearance.

Lurasidone. During clinical trials of lurasidone in patients with mild, moderate, and severe renal impairment, the mean Cmax and area under the curve was higher compared with healthy patients, which led to recommended dosage adjustments in patients with renal impairment.11

As mentioned above, renal impairment decreases the protein binding percentage of medications. Hypothetically, the greater the protein binding, the lower the recommended dosage in patients with renal impairment because the free or unbound form correlates with efficacy and toxicity. Most FGAs and SGAs have the protein-binding characteristic of ≥90%.16 Although it seems this characteristic should result in recommendations to adjust dosage based on renal function, the various pharmacokinetic studies of antipsychotics have not shown this factor to play a role in the manufacturers’ recommendations.

Antidepressants

Comorbidity rates of depression in patients with renal disease range from 14% to 30%, making use of antidepressants in renal disease common.4 Antidepressants primarily are metabolized hepatically and excreted renally. Table 217-27 summarizes recommended dosing adjustments for antidepressants.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.Escitalopram is the (S)-enantiomer of the racemic antidepressant citalopram, both of which have been shown to decrease renal clearance in patients with mild or moderate renal impairment. However, according to the package insert, no dosage adjustments are needed.17 No extensive studies have been conducted on escitalopram or citalopram, but each should be initiated at a reduced dosage and the titration schedule should be prolonged in patients with severe renal impairment or ESRD.17,18

The plasma concentration of paroxetine has been noted to be elevated in patients with severe renal impairment, and the half-life can increase to nearly 50%.4 Paroxetine should be initiated at 10 mg/d, and then titrated slowly in patients with severe renal impairment.19,28

The pharmacokinetics of fluoxetine are unchanged in any stage of renal impairment. Patients in active renal dialysis report good tolerability and efficacy.4

Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors. Venlafaxine and its metabolite O-desmethylvenlafaxine (desvenlafaxine) are primarily excreted via renal elimination. Studies have shown that mild renal impairment can have an effect on plasma levels of the drug, and that moderate or severe impairment can increase the venlafaxine plasma concentration. According to the package insert, a dosage reduction of 50% is recommended for desvenlafaxine and venlafaxine.20,21

No significant pharmacokinetic changes with duloxetine have been noted in patients with mild or moderate renal impairment.22 However, duloxetine’s major metabolites, which are excreted renally, have been measured to be as much as 7 to 9 times higher in patients with ESRD compared with healthy subjects; therefore, it is recommended to avoid duloxetine in patients with severe renal disease.4,22 Our review of the literature produced limited recommendations on dosing milnacipran and its enantiomer levomilnacipran in renally impaired patients. The milnacipran package insert cautions its use in moderate renal impairment and recommends a 50% dosage reduction to 100 mg/d (50 mg twice daily) in patients with severe renal impairment.23 Dosage recommendations for levomilnacipran are 80 mg/d for moderate renal impairment and 40 mg/d for severe impairment. Both agents have relative contraindications for ESRD.23,24

Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) are predominantly metabolized hepatically, glucuronidated, and then eliminated renally. Desipramine, imipramine, and nortriptyline have nonspecific package insert recommendations for modified dosing in geriatric patients because of an age-related decrease in renal clearance.29-31 Review articles assert that elevated glucuronidated metabolites could increase patients’ sensitivity to side effects of TCAs. Because of concerns regarding elevated glucuronidated metabolites, it has been proposed to initiate TCAs at a low dosage, titrate slowly, and maintain the lowest effective dosage in patients with renal impairment.25

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) and other antidepressants. The package inserts of the MAOIs isocarboxazid, phenelzine, selegiline, and tranylcypromine provide limited data and dosage recommendations for use in the context of renal impairment.32-36 Isocarboxazid should not be used in patients with severe renal impairment, according to the prescribing information.32 There are no dosing recommendations for transdermal selegiline in mild, moderate, or severe renal impairment.37 Extra vigilance is required when using MAOIs in patients with renal disease because of an increased risk of dialysis-induced hypotension (orthostatic hypotension is a common adverse effect of MAOIs).38

Bupropion is primarily metabolized hepatically to the active metabolite hydroxybupropion. Plasma levels of this metabolite at steady state are reported to be 10 times greater than bupropion’s concentration levels in healthy subjects; plasma levels are further increased in mild renal impairment.26 Hydroxybupropion is not dialyzable, which can increase the risk of toxicity with bupropion therapy in patients with renal impairment.3 If bupropion effectively treats depression in patients with declining renal function, specifically severe renal impairment and ESRD, then decreasing the dosage to 150 mg every 3 days is recommended to lessen the risk of toxicity. 27

Mood stabilizers

Lithium has the most published literature on dosing adjustments with renal impairment. Many providers are inclined to discontinue lithium use at the first sign of any change in renal function; however, monitoring, prevention, and treatment guidelines for lithium are well established after many years of research and clinical use.39 Lithium’s prescribing information recommends dosage adjustment in mild to moderate renal impairment and lists severe renal impairment and ESRD as relative contraindications.40

A recent study proposes more assertive use of lithium in patients with renal impairment of any severity. Rej et al41 compared continued lithium treatment to discontinuing treatment in geriatric patients with chronic renal failure, and reported (1) a statistically insignificant difference in renal function between groups at 2 years and (2) a “trending decrease” in renal function at 5 years in the lithium treatment group. With closely monitored plasma levels, lithium treatment is considered a workable treatment for patients with moderate renal impairment when mood stabilizer treatment has been effective.42

Lamotrigine and its main glucuronidated metabolite, lamotrigine-2N-glucuronide (L-2-N-G), are primarily excreted renally. In severe renal impairment and ESRD, the L-2-N-G levels are elevated but are not pharmacologically active and, therefore, do not affect plasma concentration or efficacy of lamotrigine.43 Although data are limited regarding the use of lamotrigine in severe renal impairment and ESRD, Kaufman44 reported a 17% to 20% decrease in concentration after dialysis—suggesting that post-dialysis titration might be needed in these patients.

Oxcarbazepine is metabolized by means of cytosolic enzymes in the liver to its primary pharmacologically active metabolite, 10-monohydroxy, which is further metabolized via glucuronidation and then renally excreted. There are no dosage adjustment recommendations for patients with an eCrCl >30 mL/min.45 Rouan et al46 suggest initiating oxcarbazepine at 50% of the recommended dosage and following a longer titration schedule in patients with an eCrCl 10 to 30 mL/min. No dosing suggestions for severe renal impairment and ESRD were provided because of study limitations; however, the general recommendation for psychotropic agents in patients in a severe stage of renal impairment is dosage reduction with close monitoring.46

Table 341,44,46 summarizes dosage adjustments for mood stabilizers in patients with renal impairment.

Renal disease can play a large role in altering the pharmacokinetics of medications, especially in elimination or clearance and plasma protein binding. Specifically, renal impairment decreases the plasma protein binding secondary to decreased albumin and retention of urea, which competes with medications to bind to the protein.1

Electrolyte shifts—which could lead to a fatal arrhythmia—are common among patients with renal impairment. The risk can be further increased in this population if a patient is taking a medication that can induce arrhythmia. If a drug is primarily excreted by the kidneys, elimination could be significantly altered, especially if the medication has active metabolites.1

Normal renal function is defined as an estimated creatinine clearance (eCrCl) of >80 mL/min. Renal impairment is classified as:

- mild: eCrCl, 51 to 80 mL/min

- moderate: eCrCl, 31 to 50 mL/min

- severe: eCrCl, ≤30 mL/min

- end-stage renal disease (ESRD): eCrCl, <10 mL/min.2

Overall, there is minimal information about the effects of renal disease on psychotropic therapy; our goal here is to summarize available data. We have created quick reference tables highlighting psychotropics that have renal dosing recommendations based on manufacturers’ package inserts.

Antipsychotics

First-generation antipsychotics (FGAs). Dosage adjustments based on renal function are not required for any FGA, according to manufacturers’ package inserts. Some of these antipsychotics are excreted in urine, but typically as inactive metabolites.

Although there are no dosage recommendations based on renal function provided by the labeling, there has been concern about the use of some FGAs in patients with renal impairment. Specifically, concerns center around the piperidine phenothiazines (thioridazine and mesoridazine) because of the increased risk of electrocardiographic changes and medication-induced arrhythmias in renal disease due to electrolyte imbalances.3,4 Additionally, there is case evidence5 that phenothiazine antipsychotics could increase a patient’s risk for hypotension in chronic renal failure. Haloperidol is considered safe in renal disease because <1% of the medication is excreted unchanged through urine.6

Second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs). Overall, SGAs are considered safe in patients with renal disease. Most SGAs undergo extensive hepatic metabolism before excretion, allowing them to be used safely in patients with renal disease.

Sheehan et al7 analyzed the metabolism and excretion of SGAs, evaluating 8 antipsychotics divided into 4 groups: (1) excretion primarily as an unchanged drug in urine, (2) changed drug in urine, (3) changed drug in feces, (4) and unchanged drug in feces.

- Paliperidone was found to be primarily excreted as an unchanged drug in urine.

- Clozapine, iloperidone, olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone all were found to be primarily excreted as a changed drug in urine.

- Aripiprazole and ziprasidone were found to be primarily excreted as a changed drug in feces.

The manufacturers’ package inserts for clozapine, paliperidone, risperidone, and lurasidone have recommended dosage adjustments based on renal function (Table 1).8-11

Ziprasidone. Although ziprasidone does not have a recommended renal dosage adjustment, caution is recommended because of the risk of electrocardiographic changes and potential for medication-induced arrhythmias in patients with electrolyte disturbances secondary to renal disease. A single-dosage study of ziprasidone by Aweeka et al12 demonstrated that the pharmacokinetics of ziprasidone are unchanged in patients with renal impairment.

Asenapine. A small study by Peeters et al13 evaluated the pharmacokinetics of asenapine in hepatic and renal impairment and found no clinically relevant changes in asenapine’s pharmacokinetics among patients with any level of renal impairment compared with patients with normal renal function.

Aripiprazole. Mallikaarjun et al14 completed a small study evaluating the pharmacokinetics of aripiprazole in patients with renal impairment. They found that the pharmacokinetics of aripiprazole in these patients is no different than it is in patients with normal renal function who are taking aripiprazole.

Quetiapine. Thyrum et al15 conducted a similar study with quetiapine, which showed no significant difference detected in the pharmacokinetics of quetiapine in patients with renal impairment. Additionally, quetiapine had no negative effect on patients’ creatinine clearance.

Lurasidone. During clinical trials of lurasidone in patients with mild, moderate, and severe renal impairment, the mean Cmax and area under the curve was higher compared with healthy patients, which led to recommended dosage adjustments in patients with renal impairment.11

As mentioned above, renal impairment decreases the protein binding percentage of medications. Hypothetically, the greater the protein binding, the lower the recommended dosage in patients with renal impairment because the free or unbound form correlates with efficacy and toxicity. Most FGAs and SGAs have the protein-binding characteristic of ≥90%.16 Although it seems this characteristic should result in recommendations to adjust dosage based on renal function, the various pharmacokinetic studies of antipsychotics have not shown this factor to play a role in the manufacturers’ recommendations.

Antidepressants

Comorbidity rates of depression in patients with renal disease range from 14% to 30%, making use of antidepressants in renal disease common.4 Antidepressants primarily are metabolized hepatically and excreted renally. Table 217-27 summarizes recommended dosing adjustments for antidepressants.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.Escitalopram is the (S)-enantiomer of the racemic antidepressant citalopram, both of which have been shown to decrease renal clearance in patients with mild or moderate renal impairment. However, according to the package insert, no dosage adjustments are needed.17 No extensive studies have been conducted on escitalopram or citalopram, but each should be initiated at a reduced dosage and the titration schedule should be prolonged in patients with severe renal impairment or ESRD.17,18

The plasma concentration of paroxetine has been noted to be elevated in patients with severe renal impairment, and the half-life can increase to nearly 50%.4 Paroxetine should be initiated at 10 mg/d, and then titrated slowly in patients with severe renal impairment.19,28

The pharmacokinetics of fluoxetine are unchanged in any stage of renal impairment. Patients in active renal dialysis report good tolerability and efficacy.4

Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors. Venlafaxine and its metabolite O-desmethylvenlafaxine (desvenlafaxine) are primarily excreted via renal elimination. Studies have shown that mild renal impairment can have an effect on plasma levels of the drug, and that moderate or severe impairment can increase the venlafaxine plasma concentration. According to the package insert, a dosage reduction of 50% is recommended for desvenlafaxine and venlafaxine.20,21

No significant pharmacokinetic changes with duloxetine have been noted in patients with mild or moderate renal impairment.22 However, duloxetine’s major metabolites, which are excreted renally, have been measured to be as much as 7 to 9 times higher in patients with ESRD compared with healthy subjects; therefore, it is recommended to avoid duloxetine in patients with severe renal disease.4,22 Our review of the literature produced limited recommendations on dosing milnacipran and its enantiomer levomilnacipran in renally impaired patients. The milnacipran package insert cautions its use in moderate renal impairment and recommends a 50% dosage reduction to 100 mg/d (50 mg twice daily) in patients with severe renal impairment.23 Dosage recommendations for levomilnacipran are 80 mg/d for moderate renal impairment and 40 mg/d for severe impairment. Both agents have relative contraindications for ESRD.23,24

Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) are predominantly metabolized hepatically, glucuronidated, and then eliminated renally. Desipramine, imipramine, and nortriptyline have nonspecific package insert recommendations for modified dosing in geriatric patients because of an age-related decrease in renal clearance.29-31 Review articles assert that elevated glucuronidated metabolites could increase patients’ sensitivity to side effects of TCAs. Because of concerns regarding elevated glucuronidated metabolites, it has been proposed to initiate TCAs at a low dosage, titrate slowly, and maintain the lowest effective dosage in patients with renal impairment.25

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) and other antidepressants. The package inserts of the MAOIs isocarboxazid, phenelzine, selegiline, and tranylcypromine provide limited data and dosage recommendations for use in the context of renal impairment.32-36 Isocarboxazid should not be used in patients with severe renal impairment, according to the prescribing information.32 There are no dosing recommendations for transdermal selegiline in mild, moderate, or severe renal impairment.37 Extra vigilance is required when using MAOIs in patients with renal disease because of an increased risk of dialysis-induced hypotension (orthostatic hypotension is a common adverse effect of MAOIs).38

Bupropion is primarily metabolized hepatically to the active metabolite hydroxybupropion. Plasma levels of this metabolite at steady state are reported to be 10 times greater than bupropion’s concentration levels in healthy subjects; plasma levels are further increased in mild renal impairment.26 Hydroxybupropion is not dialyzable, which can increase the risk of toxicity with bupropion therapy in patients with renal impairment.3 If bupropion effectively treats depression in patients with declining renal function, specifically severe renal impairment and ESRD, then decreasing the dosage to 150 mg every 3 days is recommended to lessen the risk of toxicity. 27

Mood stabilizers

Lithium has the most published literature on dosing adjustments with renal impairment. Many providers are inclined to discontinue lithium use at the first sign of any change in renal function; however, monitoring, prevention, and treatment guidelines for lithium are well established after many years of research and clinical use.39 Lithium’s prescribing information recommends dosage adjustment in mild to moderate renal impairment and lists severe renal impairment and ESRD as relative contraindications.40

A recent study proposes more assertive use of lithium in patients with renal impairment of any severity. Rej et al41 compared continued lithium treatment to discontinuing treatment in geriatric patients with chronic renal failure, and reported (1) a statistically insignificant difference in renal function between groups at 2 years and (2) a “trending decrease” in renal function at 5 years in the lithium treatment group. With closely monitored plasma levels, lithium treatment is considered a workable treatment for patients with moderate renal impairment when mood stabilizer treatment has been effective.42

Lamotrigine and its main glucuronidated metabolite, lamotrigine-2N-glucuronide (L-2-N-G), are primarily excreted renally. In severe renal impairment and ESRD, the L-2-N-G levels are elevated but are not pharmacologically active and, therefore, do not affect plasma concentration or efficacy of lamotrigine.43 Although data are limited regarding the use of lamotrigine in severe renal impairment and ESRD, Kaufman44 reported a 17% to 20% decrease in concentration after dialysis—suggesting that post-dialysis titration might be needed in these patients.

Oxcarbazepine is metabolized by means of cytosolic enzymes in the liver to its primary pharmacologically active metabolite, 10-monohydroxy, which is further metabolized via glucuronidation and then renally excreted. There are no dosage adjustment recommendations for patients with an eCrCl >30 mL/min.45 Rouan et al46 suggest initiating oxcarbazepine at 50% of the recommended dosage and following a longer titration schedule in patients with an eCrCl 10 to 30 mL/min. No dosing suggestions for severe renal impairment and ESRD were provided because of study limitations; however, the general recommendation for psychotropic agents in patients in a severe stage of renal impairment is dosage reduction with close monitoring.46

Table 341,44,46 summarizes dosage adjustments for mood stabilizers in patients with renal impairment.

1. Levy G. Pharmacokinetics in renal disease. Am J Med. 1977;62(4):461-465.

2. Preskorn SH. Clinically important differences in the pharmacokinetics of the ten newer “atypical” antipsychotics: part 3. Effects of renal and hepatic impairment. J Psychiatr Pract. 2012;18(6):430-437.

3. Cohen LM, Tessier EG, Germain MJ, et al. Update on psychotropic medication use in renal disease. Psychosomatics. 2004;45(1):34-48.

4. Baghdady NT, Banik S, Swartz SA, et al. Psychotropic drugs and renal failure: translating the evidence for clinical practice. Adv Ther. 2009;26(4):404-424.

5. Sheehan J, White A, Wilson R. Hazards of phenothiazines in chronic renal failure. Ir Med J. 1982;75(9):335.

6. Haloperidol [monograph]. In: Micromedex Drugdex [online database]. Greenwood Village, CO: Truven Health Analytics. Accessed December 17, 2014.

7. Sheehan JJ, Sliwa JK, Amatniek JC, et al. Atypical antipsychotic metabolism and excretion. Curr Drug Metab. 2010;11(6):516-525.

8. Clozaril [package insert]. East Hanover, NJ: Novartis Pharmaceuticals; 2014.

9. Risperdal [package insert]. Titusville, NJ: Janssen Pharmaceuticals; 2014.

10. Invega [package insert]. Titusville, NJ: Janssen Pharmaceuticals; 2014.

11. Latuda [package insert]. Fort Lee, NJ: Sunovion Pharmaceuticals; 2013.

12. Aweeka F, Jayesekara D, Horton M, et al. The pharmacokinetics of ziprasidone in subjects with normal and impaired renal function. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;49(suppl 1):27S-33S.

13. Peeters P, Bockbrader H, Spaans E, et al. Asenapine pharmacokinetics in hepatic and renal impairment. Clin Pharmacol. 2011;50(7):471-481.

14. Mallikaarjun S, Shoaf SE, Boulton DW, et al. Effects of hepatic or renal impairment on the pharmacokinetics of aripiprazole. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2008;47(8):533-542.

15. Thyrum PT, Wong YW, Yeh C. Single-dose pharmacokinetics of quetiapine in subjects with renal or hepatic impairment. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2000;24(4):521-533.

16. Lexi-Drugs. Lexicomp. Hudson, OH: Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. http://online.lexi.com. Accessed May 28, 2015.

17. Lexapro [package insert]. Forest Pharmaceuticals, Inc.: St. Louis, MO; 2014.

18. Celexa [package insert]. Forest Pharmaceuticals, Inc.: St. Louis, MO; 2014.

19. Paxil [package insert]. Research Triangle Park, NC: GlaxoSmithKline; 2008.

20. Effexor [package insert]. Philadelphia, PA: Wyeth Pharmaceuticals Inc.; 2010.

21. Pristiq [package insert]. Philadelphia, PA: Wyeth Pharmaceuticals Inc.; 2014.

22. Cymbalta [package insert]. Indianapolis, IN: Lilly USA, LLC; 2014.

23. Savella [package insert]. St. Louis, MO: Forest Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; 2013.

24. Fetzima [package insert]. St. Louis, MO: Forest Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; 2014.

25. Kurella M, Bennett WM, Chertow GM. Analgesia in patients with ESRD: a review of available evidence. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;42(2):217-228.

26. Wellbutrin [package insert]. Research Triangle Park, NC: GlaxoSmithKline; 2014.

27. Worrall SP, Almond MK, Dhillon S. Pharmacokinetics of bupropion and its metabolites in haemodialysis patients who smoke. A single dose study. Nephron Clin Pract. 2004;97(3):c83-c89.

28. Nagler EV, Webster AC, Vanholder R, et al. Antidepressants for depression in stage 3-5 chronic kidney disease: a systematic review of pharmacokinetics, efficacy and safety with recommendations by European Renal Best Practice (ERBP). Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27(10):3736-3745.

29. Norpramin. [package insert] Bridgewater, NJ: Sanofi-Aventis U.S. LLC; 2014.

30. Tofranil [package insert]. Hazelwood, MO: Mallinckrodt Inc.; 2014.

31. Pamelor [package insert]. Hazelwood, MO: Mallinckrodt Inc.; 2014.

32. Marplan [package insert]. Parsippany, NJ: Validus Pharmaceuticals, LLC; 2012.

33. Nardil [package insert]. New York, NY: Parke-Davis Division of Pfizer Inc.; 2009.

34. EMSAM [package insert]. Morgantown, WV: Mylan Specialty, L.P.; 2014.

35. Eldepryl [package insert]. Morgantown, WV: Somerset Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; 2009.

36. Parnate [package insert]. Research Triangle Park, NC: GlaxoSmithKline; 2008.

37. Culpepper L. Reducing the burden of difficult-to-treat major depressive disorder: revisiting monoamine oxidase inhibitor therapy. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2013;15(5). doi: 10.4088/PCC.13r01515.

38. Tossani E, Cassano P, Fava M. Depression and renal disease. Semin Dial. 2005;18(2):73-81.

39. Young AH, Hammond JM. Lithium in mood disorders: increasing evidence base, declining use? Br J Psychiatry. 2007;191:474-476.

40. Eskalith [package insert]. Research Triangle Park, NC: GlaxoSmithKline; 2003.

41. Rej S, Looper K, Segal M. The effect of serum lithium levels on renal function in geriatric outpatients: a retrospective longitudinal study. Drugs Aging. 2013;30(6):409-415.

42. Malhi GS, Tanious M, Das P, et al. The science and practice of lithium therapy. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2012;46(3):192-211.

43. Lamictal [package insert]. Research Triangle Park, NC: GlaxoSmithKline; 2014.

44. Kaufman KR. Lamotrigine and hemodialysis in bipolar disorder: case analysis of dosing strategy with literature review. Bipolar Disord. 2010;12(4):446-449.

45. Trileptal [package insert]. East Hanover, NJ: Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; 2014.

46. Rouan MC, Lecaillon JB, Godbillon J, et al. The effect of renal impairment on the pharmacokinetics of oxcarbazepine and its metabolites. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1994;47(2):161-167.

1. Levy G. Pharmacokinetics in renal disease. Am J Med. 1977;62(4):461-465.

2. Preskorn SH. Clinically important differences in the pharmacokinetics of the ten newer “atypical” antipsychotics: part 3. Effects of renal and hepatic impairment. J Psychiatr Pract. 2012;18(6):430-437.

3. Cohen LM, Tessier EG, Germain MJ, et al. Update on psychotropic medication use in renal disease. Psychosomatics. 2004;45(1):34-48.

4. Baghdady NT, Banik S, Swartz SA, et al. Psychotropic drugs and renal failure: translating the evidence for clinical practice. Adv Ther. 2009;26(4):404-424.

5. Sheehan J, White A, Wilson R. Hazards of phenothiazines in chronic renal failure. Ir Med J. 1982;75(9):335.

6. Haloperidol [monograph]. In: Micromedex Drugdex [online database]. Greenwood Village, CO: Truven Health Analytics. Accessed December 17, 2014.

7. Sheehan JJ, Sliwa JK, Amatniek JC, et al. Atypical antipsychotic metabolism and excretion. Curr Drug Metab. 2010;11(6):516-525.

8. Clozaril [package insert]. East Hanover, NJ: Novartis Pharmaceuticals; 2014.

9. Risperdal [package insert]. Titusville, NJ: Janssen Pharmaceuticals; 2014.

10. Invega [package insert]. Titusville, NJ: Janssen Pharmaceuticals; 2014.

11. Latuda [package insert]. Fort Lee, NJ: Sunovion Pharmaceuticals; 2013.

12. Aweeka F, Jayesekara D, Horton M, et al. The pharmacokinetics of ziprasidone in subjects with normal and impaired renal function. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;49(suppl 1):27S-33S.

13. Peeters P, Bockbrader H, Spaans E, et al. Asenapine pharmacokinetics in hepatic and renal impairment. Clin Pharmacol. 2011;50(7):471-481.

14. Mallikaarjun S, Shoaf SE, Boulton DW, et al. Effects of hepatic or renal impairment on the pharmacokinetics of aripiprazole. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2008;47(8):533-542.

15. Thyrum PT, Wong YW, Yeh C. Single-dose pharmacokinetics of quetiapine in subjects with renal or hepatic impairment. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2000;24(4):521-533.

16. Lexi-Drugs. Lexicomp. Hudson, OH: Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. http://online.lexi.com. Accessed May 28, 2015.

17. Lexapro [package insert]. Forest Pharmaceuticals, Inc.: St. Louis, MO; 2014.

18. Celexa [package insert]. Forest Pharmaceuticals, Inc.: St. Louis, MO; 2014.

19. Paxil [package insert]. Research Triangle Park, NC: GlaxoSmithKline; 2008.

20. Effexor [package insert]. Philadelphia, PA: Wyeth Pharmaceuticals Inc.; 2010.

21. Pristiq [package insert]. Philadelphia, PA: Wyeth Pharmaceuticals Inc.; 2014.

22. Cymbalta [package insert]. Indianapolis, IN: Lilly USA, LLC; 2014.

23. Savella [package insert]. St. Louis, MO: Forest Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; 2013.

24. Fetzima [package insert]. St. Louis, MO: Forest Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; 2014.

25. Kurella M, Bennett WM, Chertow GM. Analgesia in patients with ESRD: a review of available evidence. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;42(2):217-228.

26. Wellbutrin [package insert]. Research Triangle Park, NC: GlaxoSmithKline; 2014.

27. Worrall SP, Almond MK, Dhillon S. Pharmacokinetics of bupropion and its metabolites in haemodialysis patients who smoke. A single dose study. Nephron Clin Pract. 2004;97(3):c83-c89.

28. Nagler EV, Webster AC, Vanholder R, et al. Antidepressants for depression in stage 3-5 chronic kidney disease: a systematic review of pharmacokinetics, efficacy and safety with recommendations by European Renal Best Practice (ERBP). Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27(10):3736-3745.

29. Norpramin. [package insert] Bridgewater, NJ: Sanofi-Aventis U.S. LLC; 2014.

30. Tofranil [package insert]. Hazelwood, MO: Mallinckrodt Inc.; 2014.

31. Pamelor [package insert]. Hazelwood, MO: Mallinckrodt Inc.; 2014.

32. Marplan [package insert]. Parsippany, NJ: Validus Pharmaceuticals, LLC; 2012.

33. Nardil [package insert]. New York, NY: Parke-Davis Division of Pfizer Inc.; 2009.

34. EMSAM [package insert]. Morgantown, WV: Mylan Specialty, L.P.; 2014.

35. Eldepryl [package insert]. Morgantown, WV: Somerset Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; 2009.

36. Parnate [package insert]. Research Triangle Park, NC: GlaxoSmithKline; 2008.

37. Culpepper L. Reducing the burden of difficult-to-treat major depressive disorder: revisiting monoamine oxidase inhibitor therapy. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2013;15(5). doi: 10.4088/PCC.13r01515.

38. Tossani E, Cassano P, Fava M. Depression and renal disease. Semin Dial. 2005;18(2):73-81.

39. Young AH, Hammond JM. Lithium in mood disorders: increasing evidence base, declining use? Br J Psychiatry. 2007;191:474-476.

40. Eskalith [package insert]. Research Triangle Park, NC: GlaxoSmithKline; 2003.

41. Rej S, Looper K, Segal M. The effect of serum lithium levels on renal function in geriatric outpatients: a retrospective longitudinal study. Drugs Aging. 2013;30(6):409-415.

42. Malhi GS, Tanious M, Das P, et al. The science and practice of lithium therapy. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2012;46(3):192-211.

43. Lamictal [package insert]. Research Triangle Park, NC: GlaxoSmithKline; 2014.

44. Kaufman KR. Lamotrigine and hemodialysis in bipolar disorder: case analysis of dosing strategy with literature review. Bipolar Disord. 2010;12(4):446-449.

45. Trileptal [package insert]. East Hanover, NJ: Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; 2014.

46. Rouan MC, Lecaillon JB, Godbillon J, et al. The effect of renal impairment on the pharmacokinetics of oxcarbazepine and its metabolites. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1994;47(2):161-167.