User login

The question that nearly stumped me came from the back of the room.

I was giving a presentation on the hospital medicine movement to 350 physicians with an organization interested in our rapidly developing specialty. The evolution of hospital medicine is a great story, and I relish telling it. My biggest problem is usually curbing my enthusiasm to fit the time allotted. As an old colleague once told me when I launched into an exhaustive explanation of a simple medical problem: “Rusty, don’t build the watch—just tell me the time!” For this talk, I behaved myself and had managed with 10 minutes to spare for questions.

Then came the question:

“With more than a third of hospitalists directly employed by the hospital I have concerns that the loyalty of the physician will be to the best interests of the institution instead of the patient, don’t you?”

It was certainly thought provoking. The questioner was asking if the source of a physician’s paycheck trumped patient needs. For many hospitalists, our employer is technically not the patient, but the hospital.

Some referring physicians, who put their patients in our care when they hospitalize them, wonder which master we serve. Can that hospitalist in charge of my patient resist the institutional pull to drive down length of stay (LOS) and curtail costs? Whose interests will that physician favor when there is a clash between what my patients might need and the hospital’s bottom line?

I could have simply said: “No, I’m not concerned. Physicians should always act in the interest of their patients over that of the hospital.” But the real answer is far more complex—a synthesis of complementary interests that can appear mutually exclusive.

How? While my response was somewhat less well organized than this column, I attempted to address the complexity of the question by including the profile of hospitalists’ employers, the obligations of the medical staff in any hospital, physician incentives, transparency of performance, checks and balances, and the general principle of managing polarities.

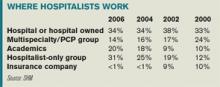

Let’s look at the scope of the issue. Who pays the hospitalist? A third are employed directly by hospitals, a fifth by academic medical centers, and nearly half by multispecialty or hospitalist-only medical groups. Two points emerge from the data. First, employment percentage by hospitals has remained stable, while academic centers and hospitalist-only groups have grown. Second, this employment model is not unique to hospitalists. These same types of practice groups and institutions employ physicians in other specialties, too.

All physicians working in a hospital are members of the active medical staff and must uphold certain core responsibilities. Chief among these are the quality and safety of care, treatment, and services delivered at the institution. That duty applies whether they are solo practitioners or employees of a hospital or independent medical group.

These core obligations are enforced by the organized medical staff through by-laws, rules, and regulations. Further, the medical staff is beholden to operate with the cooperation of hospital administration/management and hospital governance (i.e., the board) to support quality of care within the institution.

These elements are intended to provide a structure for optimizing patient care. But they often collide with the real world in which we physicians operate—a world of competing interests we face daily. While a physician’s fiduciary responsibility is always to the patient, there are often other interests to consider. Who among us has not tried to balance the often conflicting opinions and agendas of the:

- Patient;

- Caregivers/family;

- Hospital;

- Primary care physician;

- Consulting specialists; and

- Insurers.

These conflicts are usually over methods rather than outcomes. If hospitals want to cut LOS, so do patients, who want to sleep in their own beds. Hospitals want to manage costly and scarce resources wisely; patients want judicious use of treatments and tests. Hospitals want to keep costs down; patients want to keep out-of-pocket expenses down.

Are the loyalties of doctors to their patients sometimes at odds? The honest answer is, “Sometimes, yes.” Sometimes hospitals make providing care more challenging. Incentives affect how doctors behave. If bonuses accrue to good infection control, infection rates fall. If bonuses are aligned with keeping costs down, costs likely go down.

But such incentives play a role in how all doctors behave, not just hospitalists employed by a hospital. Self-employed physicians (hospitalists or otherwise) and members of a large medical practice group respond to incentives, as well.

One could argue these doctors might have a greater conflict of interest than hospital-based physicians. Think of the time pressures under which many physicians work, the complexity of the hospital environment, and the burden of paperwork.

Solo private practitioners whose only source of revenue is professional service fees may be inclined to keep patients in the hospital longer because that generates higher fees. They may also have a secondary agenda: Drive higher patient satisfaction by keeping patients in the hospital until they feel completely well, “protecting” them from hospital administrators who want to “prematurely” discharge them.

The real problem with incentives is aligning them with optimal care.

Once we establish that incentives are important, that their ultimate goal is optimal care, the next step is to create transparent, explicit performance criteria. There should be no mystery concerning which behaviors and outcomes physicians are expected to achieve, including those involving quality and safety. Finally, incentives need good checks and balances. There must be a good measurement system for desired performance and a method for keeping tabs to mitigate or eliminate unintended consequences.

All physicians must simultaneously manage the interests of the patient and the interests of the healthcare system—especially the hospital. When these goals are met, patient and system benefit by maximally utilizing precious resources such as inpatient beds, diagnostic and treatment technologies, and drugs. These resources are not limitless and should never be used without a great deal of critical thinking and consideration of alternatives.

There will always be tension between optimizing resources and treatment. Balancing these interests is not a problem to be solved, but a polarity to manage. Polarities are unsolvable because neither pole alone is the right answer. Focusing on one pole to the neglect of the other undermines our efforts to optimize patient needs and propagate a sustainable hospital care system. These alternatives are ongoing and interdependent and must be managed together.

To achieve the right balance, we must establish measures to alert us when one pole “tips” over the other. While I believe physicians, in the face of conflict of interests, must do what is right for the patient, it is also our duty to find ways to balance the interests of all involved. This is the key to a more sustainable, reliable, satisfying healthcare system—and to fulfilling our promise to monitor and self-govern the quality and safety of care we deliver. TH

Dr. Holman is president of SHM. He can be reached at holman.russell@cogenthealthcare.com

The question that nearly stumped me came from the back of the room.

I was giving a presentation on the hospital medicine movement to 350 physicians with an organization interested in our rapidly developing specialty. The evolution of hospital medicine is a great story, and I relish telling it. My biggest problem is usually curbing my enthusiasm to fit the time allotted. As an old colleague once told me when I launched into an exhaustive explanation of a simple medical problem: “Rusty, don’t build the watch—just tell me the time!” For this talk, I behaved myself and had managed with 10 minutes to spare for questions.

Then came the question:

“With more than a third of hospitalists directly employed by the hospital I have concerns that the loyalty of the physician will be to the best interests of the institution instead of the patient, don’t you?”

It was certainly thought provoking. The questioner was asking if the source of a physician’s paycheck trumped patient needs. For many hospitalists, our employer is technically not the patient, but the hospital.

Some referring physicians, who put their patients in our care when they hospitalize them, wonder which master we serve. Can that hospitalist in charge of my patient resist the institutional pull to drive down length of stay (LOS) and curtail costs? Whose interests will that physician favor when there is a clash between what my patients might need and the hospital’s bottom line?

I could have simply said: “No, I’m not concerned. Physicians should always act in the interest of their patients over that of the hospital.” But the real answer is far more complex—a synthesis of complementary interests that can appear mutually exclusive.

How? While my response was somewhat less well organized than this column, I attempted to address the complexity of the question by including the profile of hospitalists’ employers, the obligations of the medical staff in any hospital, physician incentives, transparency of performance, checks and balances, and the general principle of managing polarities.

Let’s look at the scope of the issue. Who pays the hospitalist? A third are employed directly by hospitals, a fifth by academic medical centers, and nearly half by multispecialty or hospitalist-only medical groups. Two points emerge from the data. First, employment percentage by hospitals has remained stable, while academic centers and hospitalist-only groups have grown. Second, this employment model is not unique to hospitalists. These same types of practice groups and institutions employ physicians in other specialties, too.

All physicians working in a hospital are members of the active medical staff and must uphold certain core responsibilities. Chief among these are the quality and safety of care, treatment, and services delivered at the institution. That duty applies whether they are solo practitioners or employees of a hospital or independent medical group.

These core obligations are enforced by the organized medical staff through by-laws, rules, and regulations. Further, the medical staff is beholden to operate with the cooperation of hospital administration/management and hospital governance (i.e., the board) to support quality of care within the institution.

These elements are intended to provide a structure for optimizing patient care. But they often collide with the real world in which we physicians operate—a world of competing interests we face daily. While a physician’s fiduciary responsibility is always to the patient, there are often other interests to consider. Who among us has not tried to balance the often conflicting opinions and agendas of the:

- Patient;

- Caregivers/family;

- Hospital;

- Primary care physician;

- Consulting specialists; and

- Insurers.

These conflicts are usually over methods rather than outcomes. If hospitals want to cut LOS, so do patients, who want to sleep in their own beds. Hospitals want to manage costly and scarce resources wisely; patients want judicious use of treatments and tests. Hospitals want to keep costs down; patients want to keep out-of-pocket expenses down.

Are the loyalties of doctors to their patients sometimes at odds? The honest answer is, “Sometimes, yes.” Sometimes hospitals make providing care more challenging. Incentives affect how doctors behave. If bonuses accrue to good infection control, infection rates fall. If bonuses are aligned with keeping costs down, costs likely go down.

But such incentives play a role in how all doctors behave, not just hospitalists employed by a hospital. Self-employed physicians (hospitalists or otherwise) and members of a large medical practice group respond to incentives, as well.

One could argue these doctors might have a greater conflict of interest than hospital-based physicians. Think of the time pressures under which many physicians work, the complexity of the hospital environment, and the burden of paperwork.

Solo private practitioners whose only source of revenue is professional service fees may be inclined to keep patients in the hospital longer because that generates higher fees. They may also have a secondary agenda: Drive higher patient satisfaction by keeping patients in the hospital until they feel completely well, “protecting” them from hospital administrators who want to “prematurely” discharge them.

The real problem with incentives is aligning them with optimal care.

Once we establish that incentives are important, that their ultimate goal is optimal care, the next step is to create transparent, explicit performance criteria. There should be no mystery concerning which behaviors and outcomes physicians are expected to achieve, including those involving quality and safety. Finally, incentives need good checks and balances. There must be a good measurement system for desired performance and a method for keeping tabs to mitigate or eliminate unintended consequences.

All physicians must simultaneously manage the interests of the patient and the interests of the healthcare system—especially the hospital. When these goals are met, patient and system benefit by maximally utilizing precious resources such as inpatient beds, diagnostic and treatment technologies, and drugs. These resources are not limitless and should never be used without a great deal of critical thinking and consideration of alternatives.

There will always be tension between optimizing resources and treatment. Balancing these interests is not a problem to be solved, but a polarity to manage. Polarities are unsolvable because neither pole alone is the right answer. Focusing on one pole to the neglect of the other undermines our efforts to optimize patient needs and propagate a sustainable hospital care system. These alternatives are ongoing and interdependent and must be managed together.

To achieve the right balance, we must establish measures to alert us when one pole “tips” over the other. While I believe physicians, in the face of conflict of interests, must do what is right for the patient, it is also our duty to find ways to balance the interests of all involved. This is the key to a more sustainable, reliable, satisfying healthcare system—and to fulfilling our promise to monitor and self-govern the quality and safety of care we deliver. TH

Dr. Holman is president of SHM. He can be reached at holman.russell@cogenthealthcare.com

The question that nearly stumped me came from the back of the room.

I was giving a presentation on the hospital medicine movement to 350 physicians with an organization interested in our rapidly developing specialty. The evolution of hospital medicine is a great story, and I relish telling it. My biggest problem is usually curbing my enthusiasm to fit the time allotted. As an old colleague once told me when I launched into an exhaustive explanation of a simple medical problem: “Rusty, don’t build the watch—just tell me the time!” For this talk, I behaved myself and had managed with 10 minutes to spare for questions.

Then came the question:

“With more than a third of hospitalists directly employed by the hospital I have concerns that the loyalty of the physician will be to the best interests of the institution instead of the patient, don’t you?”

It was certainly thought provoking. The questioner was asking if the source of a physician’s paycheck trumped patient needs. For many hospitalists, our employer is technically not the patient, but the hospital.

Some referring physicians, who put their patients in our care when they hospitalize them, wonder which master we serve. Can that hospitalist in charge of my patient resist the institutional pull to drive down length of stay (LOS) and curtail costs? Whose interests will that physician favor when there is a clash between what my patients might need and the hospital’s bottom line?

I could have simply said: “No, I’m not concerned. Physicians should always act in the interest of their patients over that of the hospital.” But the real answer is far more complex—a synthesis of complementary interests that can appear mutually exclusive.

How? While my response was somewhat less well organized than this column, I attempted to address the complexity of the question by including the profile of hospitalists’ employers, the obligations of the medical staff in any hospital, physician incentives, transparency of performance, checks and balances, and the general principle of managing polarities.

Let’s look at the scope of the issue. Who pays the hospitalist? A third are employed directly by hospitals, a fifth by academic medical centers, and nearly half by multispecialty or hospitalist-only medical groups. Two points emerge from the data. First, employment percentage by hospitals has remained stable, while academic centers and hospitalist-only groups have grown. Second, this employment model is not unique to hospitalists. These same types of practice groups and institutions employ physicians in other specialties, too.

All physicians working in a hospital are members of the active medical staff and must uphold certain core responsibilities. Chief among these are the quality and safety of care, treatment, and services delivered at the institution. That duty applies whether they are solo practitioners or employees of a hospital or independent medical group.

These core obligations are enforced by the organized medical staff through by-laws, rules, and regulations. Further, the medical staff is beholden to operate with the cooperation of hospital administration/management and hospital governance (i.e., the board) to support quality of care within the institution.

These elements are intended to provide a structure for optimizing patient care. But they often collide with the real world in which we physicians operate—a world of competing interests we face daily. While a physician’s fiduciary responsibility is always to the patient, there are often other interests to consider. Who among us has not tried to balance the often conflicting opinions and agendas of the:

- Patient;

- Caregivers/family;

- Hospital;

- Primary care physician;

- Consulting specialists; and

- Insurers.

These conflicts are usually over methods rather than outcomes. If hospitals want to cut LOS, so do patients, who want to sleep in their own beds. Hospitals want to manage costly and scarce resources wisely; patients want judicious use of treatments and tests. Hospitals want to keep costs down; patients want to keep out-of-pocket expenses down.

Are the loyalties of doctors to their patients sometimes at odds? The honest answer is, “Sometimes, yes.” Sometimes hospitals make providing care more challenging. Incentives affect how doctors behave. If bonuses accrue to good infection control, infection rates fall. If bonuses are aligned with keeping costs down, costs likely go down.

But such incentives play a role in how all doctors behave, not just hospitalists employed by a hospital. Self-employed physicians (hospitalists or otherwise) and members of a large medical practice group respond to incentives, as well.

One could argue these doctors might have a greater conflict of interest than hospital-based physicians. Think of the time pressures under which many physicians work, the complexity of the hospital environment, and the burden of paperwork.

Solo private practitioners whose only source of revenue is professional service fees may be inclined to keep patients in the hospital longer because that generates higher fees. They may also have a secondary agenda: Drive higher patient satisfaction by keeping patients in the hospital until they feel completely well, “protecting” them from hospital administrators who want to “prematurely” discharge them.

The real problem with incentives is aligning them with optimal care.

Once we establish that incentives are important, that their ultimate goal is optimal care, the next step is to create transparent, explicit performance criteria. There should be no mystery concerning which behaviors and outcomes physicians are expected to achieve, including those involving quality and safety. Finally, incentives need good checks and balances. There must be a good measurement system for desired performance and a method for keeping tabs to mitigate or eliminate unintended consequences.

All physicians must simultaneously manage the interests of the patient and the interests of the healthcare system—especially the hospital. When these goals are met, patient and system benefit by maximally utilizing precious resources such as inpatient beds, diagnostic and treatment technologies, and drugs. These resources are not limitless and should never be used without a great deal of critical thinking and consideration of alternatives.

There will always be tension between optimizing resources and treatment. Balancing these interests is not a problem to be solved, but a polarity to manage. Polarities are unsolvable because neither pole alone is the right answer. Focusing on one pole to the neglect of the other undermines our efforts to optimize patient needs and propagate a sustainable hospital care system. These alternatives are ongoing and interdependent and must be managed together.

To achieve the right balance, we must establish measures to alert us when one pole “tips” over the other. While I believe physicians, in the face of conflict of interests, must do what is right for the patient, it is also our duty to find ways to balance the interests of all involved. This is the key to a more sustainable, reliable, satisfying healthcare system—and to fulfilling our promise to monitor and self-govern the quality and safety of care we deliver. TH

Dr. Holman is president of SHM. He can be reached at holman.russell@cogenthealthcare.com