User login

1,200 Satisfied Customers and Counting

Another SHM Leadership Academy just ended, with introductory and advanced courses presented at the Fontainebleau resort, complete with the backdrop of Miami Beach. These four-day courses are aimed at hospitalist leaders, and have trained more than 1,200 participants to date. The faculty includes nationally recognized experts in their respective fields, as well as experienced HM leaders.

Level I courses are designed to help new leaders in HM, and focus on communication skills, hospital business drivers, leadership, strategic planning, and conflict resolution. Harjit Bhogal, MD, a hospitalist at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, found the Level I course addressed many of the roles she has as a new hospitalist. “The session on strategic planning was interactive and extremely informative,” Dr. Bhogal says. She also says the academy is an ideal place for networking, as attendees have access to more than 100 practicing hospitalist leaders with whom to connect.

Level II takes concepts introduced in Level I and refines them. Communication and negotiation, “meta-leadership,” financial storytelling, and a leadership roundtable help more advanced leaders tackle more complex issues. The session on meta-leadership was “terrific,” according to hospitalist Darlene Tad-y, MD, of Johns Hopkins. “One of the best days I have spent as an adult learner,” she says. “Lenny [Marcus] was absolutely amazing; his walk-in-the-woods approach was a terrific method to discuss leadership.”

Many see hospitalists as the future leaders of the hospital and throughout healthcare. “In addition to helping train leaders for hospital medicine, we believe that SHM has the obligation to train hospitalists to be the next hospital CMOs and CEOs,” says Larry Wellikson, MD, FHM, CEO of SHM.

Apparently, 1,200 academy graduates agree with him.

Another SHM Leadership Academy just ended, with introductory and advanced courses presented at the Fontainebleau resort, complete with the backdrop of Miami Beach. These four-day courses are aimed at hospitalist leaders, and have trained more than 1,200 participants to date. The faculty includes nationally recognized experts in their respective fields, as well as experienced HM leaders.

Level I courses are designed to help new leaders in HM, and focus on communication skills, hospital business drivers, leadership, strategic planning, and conflict resolution. Harjit Bhogal, MD, a hospitalist at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, found the Level I course addressed many of the roles she has as a new hospitalist. “The session on strategic planning was interactive and extremely informative,” Dr. Bhogal says. She also says the academy is an ideal place for networking, as attendees have access to more than 100 practicing hospitalist leaders with whom to connect.

Level II takes concepts introduced in Level I and refines them. Communication and negotiation, “meta-leadership,” financial storytelling, and a leadership roundtable help more advanced leaders tackle more complex issues. The session on meta-leadership was “terrific,” according to hospitalist Darlene Tad-y, MD, of Johns Hopkins. “One of the best days I have spent as an adult learner,” she says. “Lenny [Marcus] was absolutely amazing; his walk-in-the-woods approach was a terrific method to discuss leadership.”

Many see hospitalists as the future leaders of the hospital and throughout healthcare. “In addition to helping train leaders for hospital medicine, we believe that SHM has the obligation to train hospitalists to be the next hospital CMOs and CEOs,” says Larry Wellikson, MD, FHM, CEO of SHM.

Apparently, 1,200 academy graduates agree with him.

Another SHM Leadership Academy just ended, with introductory and advanced courses presented at the Fontainebleau resort, complete with the backdrop of Miami Beach. These four-day courses are aimed at hospitalist leaders, and have trained more than 1,200 participants to date. The faculty includes nationally recognized experts in their respective fields, as well as experienced HM leaders.

Level I courses are designed to help new leaders in HM, and focus on communication skills, hospital business drivers, leadership, strategic planning, and conflict resolution. Harjit Bhogal, MD, a hospitalist at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, found the Level I course addressed many of the roles she has as a new hospitalist. “The session on strategic planning was interactive and extremely informative,” Dr. Bhogal says. She also says the academy is an ideal place for networking, as attendees have access to more than 100 practicing hospitalist leaders with whom to connect.

Level II takes concepts introduced in Level I and refines them. Communication and negotiation, “meta-leadership,” financial storytelling, and a leadership roundtable help more advanced leaders tackle more complex issues. The session on meta-leadership was “terrific,” according to hospitalist Darlene Tad-y, MD, of Johns Hopkins. “One of the best days I have spent as an adult learner,” she says. “Lenny [Marcus] was absolutely amazing; his walk-in-the-woods approach was a terrific method to discuss leadership.”

Many see hospitalists as the future leaders of the hospital and throughout healthcare. “In addition to helping train leaders for hospital medicine, we believe that SHM has the obligation to train hospitalists to be the next hospital CMOs and CEOs,” says Larry Wellikson, MD, FHM, CEO of SHM.

Apparently, 1,200 academy graduates agree with him.

Where Loyalty Lies

The question that nearly stumped me came from the back of the room.

I was giving a presentation on the hospital medicine movement to 350 physicians with an organization interested in our rapidly developing specialty. The evolution of hospital medicine is a great story, and I relish telling it. My biggest problem is usually curbing my enthusiasm to fit the time allotted. As an old colleague once told me when I launched into an exhaustive explanation of a simple medical problem: “Rusty, don’t build the watch—just tell me the time!” For this talk, I behaved myself and had managed with 10 minutes to spare for questions.

Then came the question:

“With more than a third of hospitalists directly employed by the hospital I have concerns that the loyalty of the physician will be to the best interests of the institution instead of the patient, don’t you?”

It was certainly thought provoking. The questioner was asking if the source of a physician’s paycheck trumped patient needs. For many hospitalists, our employer is technically not the patient, but the hospital.

Some referring physicians, who put their patients in our care when they hospitalize them, wonder which master we serve. Can that hospitalist in charge of my patient resist the institutional pull to drive down length of stay (LOS) and curtail costs? Whose interests will that physician favor when there is a clash between what my patients might need and the hospital’s bottom line?

I could have simply said: “No, I’m not concerned. Physicians should always act in the interest of their patients over that of the hospital.” But the real answer is far more complex—a synthesis of complementary interests that can appear mutually exclusive.

How? While my response was somewhat less well organized than this column, I attempted to address the complexity of the question by including the profile of hospitalists’ employers, the obligations of the medical staff in any hospital, physician incentives, transparency of performance, checks and balances, and the general principle of managing polarities.

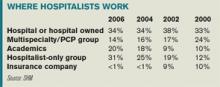

Let’s look at the scope of the issue. Who pays the hospitalist? A third are employed directly by hospitals, a fifth by academic medical centers, and nearly half by multispecialty or hospitalist-only medical groups. Two points emerge from the data. First, employment percentage by hospitals has remained stable, while academic centers and hospitalist-only groups have grown. Second, this employment model is not unique to hospitalists. These same types of practice groups and institutions employ physicians in other specialties, too.

All physicians working in a hospital are members of the active medical staff and must uphold certain core responsibilities. Chief among these are the quality and safety of care, treatment, and services delivered at the institution. That duty applies whether they are solo practitioners or employees of a hospital or independent medical group.

These core obligations are enforced by the organized medical staff through by-laws, rules, and regulations. Further, the medical staff is beholden to operate with the cooperation of hospital administration/management and hospital governance (i.e., the board) to support quality of care within the institution.

These elements are intended to provide a structure for optimizing patient care. But they often collide with the real world in which we physicians operate—a world of competing interests we face daily. While a physician’s fiduciary responsibility is always to the patient, there are often other interests to consider. Who among us has not tried to balance the often conflicting opinions and agendas of the:

- Patient;

- Caregivers/family;

- Hospital;

- Primary care physician;

- Consulting specialists; and

- Insurers.

These conflicts are usually over methods rather than outcomes. If hospitals want to cut LOS, so do patients, who want to sleep in their own beds. Hospitals want to manage costly and scarce resources wisely; patients want judicious use of treatments and tests. Hospitals want to keep costs down; patients want to keep out-of-pocket expenses down.

Are the loyalties of doctors to their patients sometimes at odds? The honest answer is, “Sometimes, yes.” Sometimes hospitals make providing care more challenging. Incentives affect how doctors behave. If bonuses accrue to good infection control, infection rates fall. If bonuses are aligned with keeping costs down, costs likely go down.

But such incentives play a role in how all doctors behave, not just hospitalists employed by a hospital. Self-employed physicians (hospitalists or otherwise) and members of a large medical practice group respond to incentives, as well.

One could argue these doctors might have a greater conflict of interest than hospital-based physicians. Think of the time pressures under which many physicians work, the complexity of the hospital environment, and the burden of paperwork.

Solo private practitioners whose only source of revenue is professional service fees may be inclined to keep patients in the hospital longer because that generates higher fees. They may also have a secondary agenda: Drive higher patient satisfaction by keeping patients in the hospital until they feel completely well, “protecting” them from hospital administrators who want to “prematurely” discharge them.

The real problem with incentives is aligning them with optimal care.

Once we establish that incentives are important, that their ultimate goal is optimal care, the next step is to create transparent, explicit performance criteria. There should be no mystery concerning which behaviors and outcomes physicians are expected to achieve, including those involving quality and safety. Finally, incentives need good checks and balances. There must be a good measurement system for desired performance and a method for keeping tabs to mitigate or eliminate unintended consequences.

All physicians must simultaneously manage the interests of the patient and the interests of the healthcare system—especially the hospital. When these goals are met, patient and system benefit by maximally utilizing precious resources such as inpatient beds, diagnostic and treatment technologies, and drugs. These resources are not limitless and should never be used without a great deal of critical thinking and consideration of alternatives.

There will always be tension between optimizing resources and treatment. Balancing these interests is not a problem to be solved, but a polarity to manage. Polarities are unsolvable because neither pole alone is the right answer. Focusing on one pole to the neglect of the other undermines our efforts to optimize patient needs and propagate a sustainable hospital care system. These alternatives are ongoing and interdependent and must be managed together.

To achieve the right balance, we must establish measures to alert us when one pole “tips” over the other. While I believe physicians, in the face of conflict of interests, must do what is right for the patient, it is also our duty to find ways to balance the interests of all involved. This is the key to a more sustainable, reliable, satisfying healthcare system—and to fulfilling our promise to monitor and self-govern the quality and safety of care we deliver. TH

Dr. Holman is president of SHM. He can be reached at holman.russell@cogenthealthcare.com

The question that nearly stumped me came from the back of the room.

I was giving a presentation on the hospital medicine movement to 350 physicians with an organization interested in our rapidly developing specialty. The evolution of hospital medicine is a great story, and I relish telling it. My biggest problem is usually curbing my enthusiasm to fit the time allotted. As an old colleague once told me when I launched into an exhaustive explanation of a simple medical problem: “Rusty, don’t build the watch—just tell me the time!” For this talk, I behaved myself and had managed with 10 minutes to spare for questions.

Then came the question:

“With more than a third of hospitalists directly employed by the hospital I have concerns that the loyalty of the physician will be to the best interests of the institution instead of the patient, don’t you?”

It was certainly thought provoking. The questioner was asking if the source of a physician’s paycheck trumped patient needs. For many hospitalists, our employer is technically not the patient, but the hospital.

Some referring physicians, who put their patients in our care when they hospitalize them, wonder which master we serve. Can that hospitalist in charge of my patient resist the institutional pull to drive down length of stay (LOS) and curtail costs? Whose interests will that physician favor when there is a clash between what my patients might need and the hospital’s bottom line?

I could have simply said: “No, I’m not concerned. Physicians should always act in the interest of their patients over that of the hospital.” But the real answer is far more complex—a synthesis of complementary interests that can appear mutually exclusive.

How? While my response was somewhat less well organized than this column, I attempted to address the complexity of the question by including the profile of hospitalists’ employers, the obligations of the medical staff in any hospital, physician incentives, transparency of performance, checks and balances, and the general principle of managing polarities.

Let’s look at the scope of the issue. Who pays the hospitalist? A third are employed directly by hospitals, a fifth by academic medical centers, and nearly half by multispecialty or hospitalist-only medical groups. Two points emerge from the data. First, employment percentage by hospitals has remained stable, while academic centers and hospitalist-only groups have grown. Second, this employment model is not unique to hospitalists. These same types of practice groups and institutions employ physicians in other specialties, too.

All physicians working in a hospital are members of the active medical staff and must uphold certain core responsibilities. Chief among these are the quality and safety of care, treatment, and services delivered at the institution. That duty applies whether they are solo practitioners or employees of a hospital or independent medical group.

These core obligations are enforced by the organized medical staff through by-laws, rules, and regulations. Further, the medical staff is beholden to operate with the cooperation of hospital administration/management and hospital governance (i.e., the board) to support quality of care within the institution.

These elements are intended to provide a structure for optimizing patient care. But they often collide with the real world in which we physicians operate—a world of competing interests we face daily. While a physician’s fiduciary responsibility is always to the patient, there are often other interests to consider. Who among us has not tried to balance the often conflicting opinions and agendas of the:

- Patient;

- Caregivers/family;

- Hospital;

- Primary care physician;

- Consulting specialists; and

- Insurers.

These conflicts are usually over methods rather than outcomes. If hospitals want to cut LOS, so do patients, who want to sleep in their own beds. Hospitals want to manage costly and scarce resources wisely; patients want judicious use of treatments and tests. Hospitals want to keep costs down; patients want to keep out-of-pocket expenses down.

Are the loyalties of doctors to their patients sometimes at odds? The honest answer is, “Sometimes, yes.” Sometimes hospitals make providing care more challenging. Incentives affect how doctors behave. If bonuses accrue to good infection control, infection rates fall. If bonuses are aligned with keeping costs down, costs likely go down.

But such incentives play a role in how all doctors behave, not just hospitalists employed by a hospital. Self-employed physicians (hospitalists or otherwise) and members of a large medical practice group respond to incentives, as well.

One could argue these doctors might have a greater conflict of interest than hospital-based physicians. Think of the time pressures under which many physicians work, the complexity of the hospital environment, and the burden of paperwork.

Solo private practitioners whose only source of revenue is professional service fees may be inclined to keep patients in the hospital longer because that generates higher fees. They may also have a secondary agenda: Drive higher patient satisfaction by keeping patients in the hospital until they feel completely well, “protecting” them from hospital administrators who want to “prematurely” discharge them.

The real problem with incentives is aligning them with optimal care.

Once we establish that incentives are important, that their ultimate goal is optimal care, the next step is to create transparent, explicit performance criteria. There should be no mystery concerning which behaviors and outcomes physicians are expected to achieve, including those involving quality and safety. Finally, incentives need good checks and balances. There must be a good measurement system for desired performance and a method for keeping tabs to mitigate or eliminate unintended consequences.

All physicians must simultaneously manage the interests of the patient and the interests of the healthcare system—especially the hospital. When these goals are met, patient and system benefit by maximally utilizing precious resources such as inpatient beds, diagnostic and treatment technologies, and drugs. These resources are not limitless and should never be used without a great deal of critical thinking and consideration of alternatives.

There will always be tension between optimizing resources and treatment. Balancing these interests is not a problem to be solved, but a polarity to manage. Polarities are unsolvable because neither pole alone is the right answer. Focusing on one pole to the neglect of the other undermines our efforts to optimize patient needs and propagate a sustainable hospital care system. These alternatives are ongoing and interdependent and must be managed together.

To achieve the right balance, we must establish measures to alert us when one pole “tips” over the other. While I believe physicians, in the face of conflict of interests, must do what is right for the patient, it is also our duty to find ways to balance the interests of all involved. This is the key to a more sustainable, reliable, satisfying healthcare system—and to fulfilling our promise to monitor and self-govern the quality and safety of care we deliver. TH

Dr. Holman is president of SHM. He can be reached at holman.russell@cogenthealthcare.com

The question that nearly stumped me came from the back of the room.

I was giving a presentation on the hospital medicine movement to 350 physicians with an organization interested in our rapidly developing specialty. The evolution of hospital medicine is a great story, and I relish telling it. My biggest problem is usually curbing my enthusiasm to fit the time allotted. As an old colleague once told me when I launched into an exhaustive explanation of a simple medical problem: “Rusty, don’t build the watch—just tell me the time!” For this talk, I behaved myself and had managed with 10 minutes to spare for questions.

Then came the question:

“With more than a third of hospitalists directly employed by the hospital I have concerns that the loyalty of the physician will be to the best interests of the institution instead of the patient, don’t you?”

It was certainly thought provoking. The questioner was asking if the source of a physician’s paycheck trumped patient needs. For many hospitalists, our employer is technically not the patient, but the hospital.

Some referring physicians, who put their patients in our care when they hospitalize them, wonder which master we serve. Can that hospitalist in charge of my patient resist the institutional pull to drive down length of stay (LOS) and curtail costs? Whose interests will that physician favor when there is a clash between what my patients might need and the hospital’s bottom line?

I could have simply said: “No, I’m not concerned. Physicians should always act in the interest of their patients over that of the hospital.” But the real answer is far more complex—a synthesis of complementary interests that can appear mutually exclusive.

How? While my response was somewhat less well organized than this column, I attempted to address the complexity of the question by including the profile of hospitalists’ employers, the obligations of the medical staff in any hospital, physician incentives, transparency of performance, checks and balances, and the general principle of managing polarities.

Let’s look at the scope of the issue. Who pays the hospitalist? A third are employed directly by hospitals, a fifth by academic medical centers, and nearly half by multispecialty or hospitalist-only medical groups. Two points emerge from the data. First, employment percentage by hospitals has remained stable, while academic centers and hospitalist-only groups have grown. Second, this employment model is not unique to hospitalists. These same types of practice groups and institutions employ physicians in other specialties, too.

All physicians working in a hospital are members of the active medical staff and must uphold certain core responsibilities. Chief among these are the quality and safety of care, treatment, and services delivered at the institution. That duty applies whether they are solo practitioners or employees of a hospital or independent medical group.

These core obligations are enforced by the organized medical staff through by-laws, rules, and regulations. Further, the medical staff is beholden to operate with the cooperation of hospital administration/management and hospital governance (i.e., the board) to support quality of care within the institution.

These elements are intended to provide a structure for optimizing patient care. But they often collide with the real world in which we physicians operate—a world of competing interests we face daily. While a physician’s fiduciary responsibility is always to the patient, there are often other interests to consider. Who among us has not tried to balance the often conflicting opinions and agendas of the:

- Patient;

- Caregivers/family;

- Hospital;

- Primary care physician;

- Consulting specialists; and

- Insurers.

These conflicts are usually over methods rather than outcomes. If hospitals want to cut LOS, so do patients, who want to sleep in their own beds. Hospitals want to manage costly and scarce resources wisely; patients want judicious use of treatments and tests. Hospitals want to keep costs down; patients want to keep out-of-pocket expenses down.

Are the loyalties of doctors to their patients sometimes at odds? The honest answer is, “Sometimes, yes.” Sometimes hospitals make providing care more challenging. Incentives affect how doctors behave. If bonuses accrue to good infection control, infection rates fall. If bonuses are aligned with keeping costs down, costs likely go down.

But such incentives play a role in how all doctors behave, not just hospitalists employed by a hospital. Self-employed physicians (hospitalists or otherwise) and members of a large medical practice group respond to incentives, as well.

One could argue these doctors might have a greater conflict of interest than hospital-based physicians. Think of the time pressures under which many physicians work, the complexity of the hospital environment, and the burden of paperwork.

Solo private practitioners whose only source of revenue is professional service fees may be inclined to keep patients in the hospital longer because that generates higher fees. They may also have a secondary agenda: Drive higher patient satisfaction by keeping patients in the hospital until they feel completely well, “protecting” them from hospital administrators who want to “prematurely” discharge them.

The real problem with incentives is aligning them with optimal care.

Once we establish that incentives are important, that their ultimate goal is optimal care, the next step is to create transparent, explicit performance criteria. There should be no mystery concerning which behaviors and outcomes physicians are expected to achieve, including those involving quality and safety. Finally, incentives need good checks and balances. There must be a good measurement system for desired performance and a method for keeping tabs to mitigate or eliminate unintended consequences.

All physicians must simultaneously manage the interests of the patient and the interests of the healthcare system—especially the hospital. When these goals are met, patient and system benefit by maximally utilizing precious resources such as inpatient beds, diagnostic and treatment technologies, and drugs. These resources are not limitless and should never be used without a great deal of critical thinking and consideration of alternatives.

There will always be tension between optimizing resources and treatment. Balancing these interests is not a problem to be solved, but a polarity to manage. Polarities are unsolvable because neither pole alone is the right answer. Focusing on one pole to the neglect of the other undermines our efforts to optimize patient needs and propagate a sustainable hospital care system. These alternatives are ongoing and interdependent and must be managed together.

To achieve the right balance, we must establish measures to alert us when one pole “tips” over the other. While I believe physicians, in the face of conflict of interests, must do what is right for the patient, it is also our duty to find ways to balance the interests of all involved. This is the key to a more sustainable, reliable, satisfying healthcare system—and to fulfilling our promise to monitor and self-govern the quality and safety of care we deliver. TH

Dr. Holman is president of SHM. He can be reached at holman.russell@cogenthealthcare.com

Readmission or the Egg?

If you heat water sufficiently, you get steam. When you cool the steam, you get water again. Using the same process for chocolate—more “busy” than water and composed of multiple ingredients—will take you from solid to liquid and back again. So why won’t this technique also apply to the egg?

Eggs, or egg whites to be specific, are made up almost exclusively of the protein albumin. The chains of amino acids in proteins are normally configured in elaborate and precise folds, spirals, and sheets. Upon heating, the albumin becomes denatured and alters its molecular structure in such a way that it unfolds and adheres to itself in a dysfunctional manner known as aggregates. In the end, albumin permanently changes from clear to white and retains a rigid form.

No intervention has been successful in returning albumin to its original viscosity and color—not cooling, not anything. The caveat is that there is exciting research being done with naturally existing heat shock proteins called chaperones that have the potential to return proteins to their native state. This research has enormous implications for treating diseases such as cystic fibrosis and Alzheimer’s.

It may seem idiosyncratic that while we can manipulate water and chocolate, we can’t unfry an egg. The answer is, simply, that proteins are too complex for simple logic or techniques.

In its June report, the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC), the group that advises Congress on issues affecting the Medicare program, formulated recommendations for amending the construct for payments to hospitals based on their readmission rates. The rationale for targeting readmission rates, according to MedPAC, is to create favorable financial incentives for hospitals that achieve lower readmissions. Sounds simple enough. The MedPAC report identified potential savings of $12 billion given a 13.3% rate of “potentially preventable readmissions” within 30 days. Not only does it sound simple, it sounds compelling for quality and financial imperatives.

SHM has long identified transitions of care as one of the most vulnerable events for patients. Some of the earliest presentations at SHM meetings vividly described the “voltage drop” of information that can occur when a patient enters or leaves the hospital—not to mention during intra-hospital transitions. SHM has embraced transitions of care as a core competency in hospital medicine, has built a quality improvement resource room online for care transitions of older adults, and in July year co-sponsored a summit on transitions of care.

Readmission rates are commonly considered a proxy outcome measure to reflect the broader issue of quality of care transitions at the time of hospital discharge; however, we must be clear that these two entities are not nearly synonymous. A hospital readmission does not necessarily reflect a poorly executed hospital discharge, and high-quality discharges do not absolutely prevent hospital readmissions. The challenge with improving transitions of care and reducing preventable readmissions lies in the systems, processes, facilities, and people involved.

To drive lower readmission rates, MedPAC is suggesting a bifurcated strategy: public reporting and altering payment schedules to hospitals. I believe the former, combined with appropriate public education on the multifactorial nature of readmissions and how to interpret the data, can be a positive step toward improving care transitions. The more transparent the healthcare system becomes, the more frank conversations we can have in the pursuit of higher quality care. Those conversations open the door to understanding the complexity of care processes and the dependency of various resources and stakeholders on one another. They also help to confront the brutal truth of care transitions: that there must be shared accountability for ensuring our patients receive the support they need, where and when they need it.

By recommending changes in payment methodology to hospitals, however, MedPAC is isolating the facility from the intricate composite of systems and processes involved in transitions of care. While I realize the analogy is a bit of a stretch, this approach strikes me as similar to applying the logic of cooling to unfry an egg. A generally simple tactic to address a highly complex issue. Just as albumin has precise folds, spirals, and sheets to allow it to perform its proper function as a protein, so too must the healthcare system provide proper coordination, communication and support services to ensure proper health and well-being of patients.

Restructuring hospital payments in no way addresses the role of physicians in the hospital, physicians in the ambulatory or sub-acute setting, home-care agencies, other vendors, caregiver compliance, patient self-care, or chronic disease management. MedPAC’s proposal holds one party accountable in a scenario where only joint accountability will render the results we desire. In a recent article in the Harvard Business Review, Roger Martin eloquently describes a common coping mechanism people use to address complexity and ambiguity—simplification whenever possible. Within organizations, “When a colleague admonishes us to ‘quit complicating the issue,’ it’s not just an impatient reminder to get on with the damn job—it’s also a plea to keep the complexity at a comfortable level.”

I do not mean to imply incentives are not important; they are vital to stimulate change and manage behavior. That being said, I also believe incentive programs often beget unintended consequences and may drive undesirable behavior.

Would MedPAC’s proposal cause hospitals to become apprehensive about accepting more complex cases? Even the best severity-adjustment methods account for only a fraction of the variations among patients, so hospitals may feel compelled to screen or select out certain complex populations as opposed to relying on severity-adjustment measures to account for true differences in patient outcomes.

Don Berwick, MD, the CEO of the Institute of Healthcare Improvement (IHI), is often quoted as saying, “Every system is perfectly designed to achieve the results it gets.” If this is so, a singular focus on incentives and penalties directed toward hospitals will bring either unilateral facility actions and/or a lack of leverage to effect needed improvements in the rest of the care system.

Alternatively, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Systems (CMS) could focus on several areas that constructively address the interdependent systems and multiple stakeholders involved in transitions of care. CMS could:

- Adopt a public reporting system for readmission rates for hospitals according to select discharge diagnoses. Transparency likely will drive some improvements via the “Hawthorne effect,” and it will serve as a common basis for key parties discussing the issues to drive improvement;

- Advocate that public reporting should be accompanied by rigorous public education on transitions of care. Such education should include a clear outline of the complexities, interdependencies, and pitfalls common to care transitions, and should also include clear steps patients and caregivers can take to play an effective role in the process;

- Participate in the development of improvement tools to address readmission rates. IHI is a terrific example of an organization that has created such a device to improve hospital mortality rates. Their Mortality Diagnostic Tool identifies potentially avoidable hospital deaths;

- Sponsor collaborative meetings with key industry organizations to discuss the issues, gain consensus on standards and expectations, and promote necessary change; and

- Take the framework of reporting, education, improvement tools and practice standards to create aligned incentives across facilities, providers, vendors, and beneficiaries.

While it’s tempting to seek simple answers to complex issues, they often fall short of the best solution. As leaders in healthcare, we must embrace complexity and find answers that reflect an integrated and aligned approach. We must acknowledge that accountability for high-quality transitions of care and reductions in readmissions has to be shared. With the support of CMS, SHM, and other agencies and professional organizations, we have every resource available to improve this vulnerable time in the lives of our patients. Only then will we have an environment suitable to unfry the egg. Or perhaps we’ll engineer an environment where the egg is never fried in the first place. TH

Dr. Holman is the president of SHM.

If you heat water sufficiently, you get steam. When you cool the steam, you get water again. Using the same process for chocolate—more “busy” than water and composed of multiple ingredients—will take you from solid to liquid and back again. So why won’t this technique also apply to the egg?

Eggs, or egg whites to be specific, are made up almost exclusively of the protein albumin. The chains of amino acids in proteins are normally configured in elaborate and precise folds, spirals, and sheets. Upon heating, the albumin becomes denatured and alters its molecular structure in such a way that it unfolds and adheres to itself in a dysfunctional manner known as aggregates. In the end, albumin permanently changes from clear to white and retains a rigid form.

No intervention has been successful in returning albumin to its original viscosity and color—not cooling, not anything. The caveat is that there is exciting research being done with naturally existing heat shock proteins called chaperones that have the potential to return proteins to their native state. This research has enormous implications for treating diseases such as cystic fibrosis and Alzheimer’s.

It may seem idiosyncratic that while we can manipulate water and chocolate, we can’t unfry an egg. The answer is, simply, that proteins are too complex for simple logic or techniques.

In its June report, the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC), the group that advises Congress on issues affecting the Medicare program, formulated recommendations for amending the construct for payments to hospitals based on their readmission rates. The rationale for targeting readmission rates, according to MedPAC, is to create favorable financial incentives for hospitals that achieve lower readmissions. Sounds simple enough. The MedPAC report identified potential savings of $12 billion given a 13.3% rate of “potentially preventable readmissions” within 30 days. Not only does it sound simple, it sounds compelling for quality and financial imperatives.

SHM has long identified transitions of care as one of the most vulnerable events for patients. Some of the earliest presentations at SHM meetings vividly described the “voltage drop” of information that can occur when a patient enters or leaves the hospital—not to mention during intra-hospital transitions. SHM has embraced transitions of care as a core competency in hospital medicine, has built a quality improvement resource room online for care transitions of older adults, and in July year co-sponsored a summit on transitions of care.

Readmission rates are commonly considered a proxy outcome measure to reflect the broader issue of quality of care transitions at the time of hospital discharge; however, we must be clear that these two entities are not nearly synonymous. A hospital readmission does not necessarily reflect a poorly executed hospital discharge, and high-quality discharges do not absolutely prevent hospital readmissions. The challenge with improving transitions of care and reducing preventable readmissions lies in the systems, processes, facilities, and people involved.

To drive lower readmission rates, MedPAC is suggesting a bifurcated strategy: public reporting and altering payment schedules to hospitals. I believe the former, combined with appropriate public education on the multifactorial nature of readmissions and how to interpret the data, can be a positive step toward improving care transitions. The more transparent the healthcare system becomes, the more frank conversations we can have in the pursuit of higher quality care. Those conversations open the door to understanding the complexity of care processes and the dependency of various resources and stakeholders on one another. They also help to confront the brutal truth of care transitions: that there must be shared accountability for ensuring our patients receive the support they need, where and when they need it.

By recommending changes in payment methodology to hospitals, however, MedPAC is isolating the facility from the intricate composite of systems and processes involved in transitions of care. While I realize the analogy is a bit of a stretch, this approach strikes me as similar to applying the logic of cooling to unfry an egg. A generally simple tactic to address a highly complex issue. Just as albumin has precise folds, spirals, and sheets to allow it to perform its proper function as a protein, so too must the healthcare system provide proper coordination, communication and support services to ensure proper health and well-being of patients.

Restructuring hospital payments in no way addresses the role of physicians in the hospital, physicians in the ambulatory or sub-acute setting, home-care agencies, other vendors, caregiver compliance, patient self-care, or chronic disease management. MedPAC’s proposal holds one party accountable in a scenario where only joint accountability will render the results we desire. In a recent article in the Harvard Business Review, Roger Martin eloquently describes a common coping mechanism people use to address complexity and ambiguity—simplification whenever possible. Within organizations, “When a colleague admonishes us to ‘quit complicating the issue,’ it’s not just an impatient reminder to get on with the damn job—it’s also a plea to keep the complexity at a comfortable level.”

I do not mean to imply incentives are not important; they are vital to stimulate change and manage behavior. That being said, I also believe incentive programs often beget unintended consequences and may drive undesirable behavior.

Would MedPAC’s proposal cause hospitals to become apprehensive about accepting more complex cases? Even the best severity-adjustment methods account for only a fraction of the variations among patients, so hospitals may feel compelled to screen or select out certain complex populations as opposed to relying on severity-adjustment measures to account for true differences in patient outcomes.

Don Berwick, MD, the CEO of the Institute of Healthcare Improvement (IHI), is often quoted as saying, “Every system is perfectly designed to achieve the results it gets.” If this is so, a singular focus on incentives and penalties directed toward hospitals will bring either unilateral facility actions and/or a lack of leverage to effect needed improvements in the rest of the care system.

Alternatively, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Systems (CMS) could focus on several areas that constructively address the interdependent systems and multiple stakeholders involved in transitions of care. CMS could:

- Adopt a public reporting system for readmission rates for hospitals according to select discharge diagnoses. Transparency likely will drive some improvements via the “Hawthorne effect,” and it will serve as a common basis for key parties discussing the issues to drive improvement;

- Advocate that public reporting should be accompanied by rigorous public education on transitions of care. Such education should include a clear outline of the complexities, interdependencies, and pitfalls common to care transitions, and should also include clear steps patients and caregivers can take to play an effective role in the process;

- Participate in the development of improvement tools to address readmission rates. IHI is a terrific example of an organization that has created such a device to improve hospital mortality rates. Their Mortality Diagnostic Tool identifies potentially avoidable hospital deaths;

- Sponsor collaborative meetings with key industry organizations to discuss the issues, gain consensus on standards and expectations, and promote necessary change; and

- Take the framework of reporting, education, improvement tools and practice standards to create aligned incentives across facilities, providers, vendors, and beneficiaries.

While it’s tempting to seek simple answers to complex issues, they often fall short of the best solution. As leaders in healthcare, we must embrace complexity and find answers that reflect an integrated and aligned approach. We must acknowledge that accountability for high-quality transitions of care and reductions in readmissions has to be shared. With the support of CMS, SHM, and other agencies and professional organizations, we have every resource available to improve this vulnerable time in the lives of our patients. Only then will we have an environment suitable to unfry the egg. Or perhaps we’ll engineer an environment where the egg is never fried in the first place. TH

Dr. Holman is the president of SHM.

If you heat water sufficiently, you get steam. When you cool the steam, you get water again. Using the same process for chocolate—more “busy” than water and composed of multiple ingredients—will take you from solid to liquid and back again. So why won’t this technique also apply to the egg?

Eggs, or egg whites to be specific, are made up almost exclusively of the protein albumin. The chains of amino acids in proteins are normally configured in elaborate and precise folds, spirals, and sheets. Upon heating, the albumin becomes denatured and alters its molecular structure in such a way that it unfolds and adheres to itself in a dysfunctional manner known as aggregates. In the end, albumin permanently changes from clear to white and retains a rigid form.

No intervention has been successful in returning albumin to its original viscosity and color—not cooling, not anything. The caveat is that there is exciting research being done with naturally existing heat shock proteins called chaperones that have the potential to return proteins to their native state. This research has enormous implications for treating diseases such as cystic fibrosis and Alzheimer’s.

It may seem idiosyncratic that while we can manipulate water and chocolate, we can’t unfry an egg. The answer is, simply, that proteins are too complex for simple logic or techniques.

In its June report, the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC), the group that advises Congress on issues affecting the Medicare program, formulated recommendations for amending the construct for payments to hospitals based on their readmission rates. The rationale for targeting readmission rates, according to MedPAC, is to create favorable financial incentives for hospitals that achieve lower readmissions. Sounds simple enough. The MedPAC report identified potential savings of $12 billion given a 13.3% rate of “potentially preventable readmissions” within 30 days. Not only does it sound simple, it sounds compelling for quality and financial imperatives.

SHM has long identified transitions of care as one of the most vulnerable events for patients. Some of the earliest presentations at SHM meetings vividly described the “voltage drop” of information that can occur when a patient enters or leaves the hospital—not to mention during intra-hospital transitions. SHM has embraced transitions of care as a core competency in hospital medicine, has built a quality improvement resource room online for care transitions of older adults, and in July year co-sponsored a summit on transitions of care.

Readmission rates are commonly considered a proxy outcome measure to reflect the broader issue of quality of care transitions at the time of hospital discharge; however, we must be clear that these two entities are not nearly synonymous. A hospital readmission does not necessarily reflect a poorly executed hospital discharge, and high-quality discharges do not absolutely prevent hospital readmissions. The challenge with improving transitions of care and reducing preventable readmissions lies in the systems, processes, facilities, and people involved.

To drive lower readmission rates, MedPAC is suggesting a bifurcated strategy: public reporting and altering payment schedules to hospitals. I believe the former, combined with appropriate public education on the multifactorial nature of readmissions and how to interpret the data, can be a positive step toward improving care transitions. The more transparent the healthcare system becomes, the more frank conversations we can have in the pursuit of higher quality care. Those conversations open the door to understanding the complexity of care processes and the dependency of various resources and stakeholders on one another. They also help to confront the brutal truth of care transitions: that there must be shared accountability for ensuring our patients receive the support they need, where and when they need it.

By recommending changes in payment methodology to hospitals, however, MedPAC is isolating the facility from the intricate composite of systems and processes involved in transitions of care. While I realize the analogy is a bit of a stretch, this approach strikes me as similar to applying the logic of cooling to unfry an egg. A generally simple tactic to address a highly complex issue. Just as albumin has precise folds, spirals, and sheets to allow it to perform its proper function as a protein, so too must the healthcare system provide proper coordination, communication and support services to ensure proper health and well-being of patients.

Restructuring hospital payments in no way addresses the role of physicians in the hospital, physicians in the ambulatory or sub-acute setting, home-care agencies, other vendors, caregiver compliance, patient self-care, or chronic disease management. MedPAC’s proposal holds one party accountable in a scenario where only joint accountability will render the results we desire. In a recent article in the Harvard Business Review, Roger Martin eloquently describes a common coping mechanism people use to address complexity and ambiguity—simplification whenever possible. Within organizations, “When a colleague admonishes us to ‘quit complicating the issue,’ it’s not just an impatient reminder to get on with the damn job—it’s also a plea to keep the complexity at a comfortable level.”

I do not mean to imply incentives are not important; they are vital to stimulate change and manage behavior. That being said, I also believe incentive programs often beget unintended consequences and may drive undesirable behavior.

Would MedPAC’s proposal cause hospitals to become apprehensive about accepting more complex cases? Even the best severity-adjustment methods account for only a fraction of the variations among patients, so hospitals may feel compelled to screen or select out certain complex populations as opposed to relying on severity-adjustment measures to account for true differences in patient outcomes.

Don Berwick, MD, the CEO of the Institute of Healthcare Improvement (IHI), is often quoted as saying, “Every system is perfectly designed to achieve the results it gets.” If this is so, a singular focus on incentives and penalties directed toward hospitals will bring either unilateral facility actions and/or a lack of leverage to effect needed improvements in the rest of the care system.

Alternatively, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Systems (CMS) could focus on several areas that constructively address the interdependent systems and multiple stakeholders involved in transitions of care. CMS could:

- Adopt a public reporting system for readmission rates for hospitals according to select discharge diagnoses. Transparency likely will drive some improvements via the “Hawthorne effect,” and it will serve as a common basis for key parties discussing the issues to drive improvement;

- Advocate that public reporting should be accompanied by rigorous public education on transitions of care. Such education should include a clear outline of the complexities, interdependencies, and pitfalls common to care transitions, and should also include clear steps patients and caregivers can take to play an effective role in the process;

- Participate in the development of improvement tools to address readmission rates. IHI is a terrific example of an organization that has created such a device to improve hospital mortality rates. Their Mortality Diagnostic Tool identifies potentially avoidable hospital deaths;

- Sponsor collaborative meetings with key industry organizations to discuss the issues, gain consensus on standards and expectations, and promote necessary change; and

- Take the framework of reporting, education, improvement tools and practice standards to create aligned incentives across facilities, providers, vendors, and beneficiaries.

While it’s tempting to seek simple answers to complex issues, they often fall short of the best solution. As leaders in healthcare, we must embrace complexity and find answers that reflect an integrated and aligned approach. We must acknowledge that accountability for high-quality transitions of care and reductions in readmissions has to be shared. With the support of CMS, SHM, and other agencies and professional organizations, we have every resource available to improve this vulnerable time in the lives of our patients. Only then will we have an environment suitable to unfry the egg. Or perhaps we’ll engineer an environment where the egg is never fried in the first place. TH

Dr. Holman is the president of SHM.

Look No Further

As I follow Mary Jo Gorman, MD, MBA, as president of SHM, it might be tempting for me to simply follow the leading rule of the “organizational” Hippocratic Oath and “First do no harm.”

Put another way, in the context of the success SHM has enjoyed for the past 10 years, there is a case to be made for standing out of the way of our society’s positive momentum. But I believe we can—and will—do better than that. None of us can afford to be spectators in this arena.

We often speak of teamwork in healthcare, but precious few of us intuitively know what this means—much less have any education in its principles. During my training, the idea of teamwork amounted to little more than relying on a medical assistant to obtain daily weights or counting on the pharmacist to calculate and follow the appropriate dosing schedule for gentamicin. Common sense led me to understand that building an amicable relationship with the nursing staff made my working life easier.

Slowly, the advantages of structuring a more organized team in the hospital setting became more evident and helped encourage me to find ways of exploiting this concept further. As I look back, it was Jeff Dichter, MD, past president of SHM and director of the hospitalist program at Ball Memorial Hospital in Muncie, Ind., who emerged as one of the true champions for teamwork as an optimal model for inpatient care. Jeff would talk about it to everyone who would listen, in every venue he could reach. He wrote about it in this very column. He charged our meeting planners and committee chairs with integrating teamwork principles into our educational content as well as our advocacy and membership development initiatives. His vision of a true team galvanized SHM’s commitment to supporting a broad constituency, extending well beyond hospitalist physicians. Jeff knew care is never delivered by an individual; it’s always a team. And he believed this framework to be fully realized by way of building from a strong organizational agenda for quality improvement.

Speaking of quality in healthcare, I look no further than Mark Williams, MD, editor of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, for having built that agenda for our society through his own efforts as well as collaboration with the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) and other national entities. As another past president of SHM, Mark brought a level of organizational focus and rigor around quality improvement and patient safety that rose to the challenges outlined in two Institute of Medicine reports, “To Err is Human” and “Crossing the Quality Chasm.” He helped move “quality” from something we talk about to something we do. He pushed it from an espoused value to a core commitment of our specialty. Quality improvement is now inseparable from what I consider to be the true promise of hospital medicine: that care organized in well-orchestrated, well-resourced teams can deliver our patients remarkable improvements in the quality, safety, and experience of healthcare.

But how do we get this done? How do we take a relatively abstract notion of a team, channel its activities to drive measurable improvements in quality, and change the arcane systems of inpatient care so as to sustain and hardwire those improvements?

Leadership. Like it or not, each of you is regarded as one of—if not the—most important leaders in the hospital. Nursing, case management, physical therapy, patients, and families look to you to provide leadership for clinical and operational systems. You are the person most able to make meaningful decisions at the front-line level that directly affect the patient experience. You are called upon to lead and manage change in a volatile environment, to resolve the inevitable conflicts that change provokes, and to reconcile hospital business drivers with quality and safety imperatives.

Our immediate past president, Dr. Gorman, emphasized the crucial role we serve as leaders. Recognizing the tremendous development needs for skills and knowledge to effectively lead, SHM has created Leadership Academies and is working on e-discussion forums and mentoring programs to promote longitudinal learning. While we must unlearn some of the behaviors and beliefs seared into our brains during our traditional medical training, we must position ourselves to forge high-performing teams and lead the quality agenda.

At a dinner during the SHM Annual Meeting in May, I sat with a senior leader from the American Medical Association’s Organized Medical Staff Section (AMA OMSS). He had flown in with other AMA representatives to meet with us on common interests. By the end of the evening, the late-career surgeon took me aside and said: “I have to tell you how touched I am by your organization. The passion, drive, and commitment of your membership is what’s missing in so many professional societies today. You must bring this passion to the larger house of medicine.”

As SHM enjoys 10 years of explosive growth and remarkable success, we need to balance the right to celebrate success with the duty not to rest on laurels. Much has been accomplished, but more than a life’s work lies before us. The road is complex and fraught with uncertainty. We might become frustrated with mounting complexity, tired with resistance to change, and fatigued with leading against the status quo. It is hard—and lonely—to confront the systems and issues that desperately need to be confronted on our journey to transform care. And it might be easy for us to become distracted from our core commitments to teamwork and leading quality by allowing our medical society to become more of a guild that defends our professional incomes and way of life. Yet I believe—I know—a much brighter future lies ahead than emerging as a casualty of temptation.

If the best predictor of behavior is past behavior, then our future will mirror the spirit in which SHM was founded. It’s the spirit an invited guest observed in a few short hours at our annual meeting. It’s the spirit that binds teamwork, quality improvement, and leadership into a unified approach to our professional endeavors. That spirit has a name: accountability. It’s the fundamental understanding that we are answerable to others, including patients, families, the community, hospital and medical staff, as well as each other, for the performance of the care systems in which we work.

Being accountable means we must rebuild trust of the broader public in hospital care, and that we follow through on the promise of hospital medicine. It means we own our mistakes, we agree that transparency and measurement will lead to better outcomes, and we commit to being part of the solution.

Accountability also mandates that we eliminate blame and “victimhood.” We cannot first think of ourselves as victims of a broken reimbursement model, or a lack of data or a hospital administration that “just doesn’t get it.” The real questions are: What can I do today about improving management of scarce resources? About the nursing shortage? About incorporating patient-safety principles into a new facility? About access to care and overcrowding? About the needless hospital deaths due to ventilator-assisted pneumonia (VAP), acute myocardial infarction, and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus? About ensuring seamless transitions of patients throughout the care continuum?

Several years ago I spoke with Brent James, MD, executive director of the Institute for Health Care Delivery Research and vice president of medical research and continuing medical education at InterMountain Healthcare in Salt Lake City, Utah. At the time, I was trying to learn quality improvement methods and practices. He reminded me of a quote Sir William Osler, the father of internal medicine, made at the end of his career when he gave an address at the Phipps Clinic in England to a group of young physicians who had recently completed training. They were about to embark on their careers early in the 20th century. “I am sorry for you young men of this generation,” he told the physicians. “Oh, you’ll do great things. You’ll have great victories, and standing on our shoulders you’ll see far. But you can never have our sensations. To have lived through a revolution, to have seen a new birth of science, new dispensation of health, redesigned medical training, remodeled hospitals, a new outlook for humanity. That is not given to every generation.”

While it seems appropriate in retrospect that these young physicians were indeed entering a time after which tremendous change and transformation had taken place, it seems equally appropriate to consider ourselves one of those generations that must lead and drive change of the magnitude of which Osler spoke. As we lead teams in the hospital to revolutionize the state of healthcare quality, we must begin every thought, every action, by holding ourselves and each other accountable for being part of the solution. To begin, we need look no further than ourselves. TH

Dr. Holman is president of SHM.

As I follow Mary Jo Gorman, MD, MBA, as president of SHM, it might be tempting for me to simply follow the leading rule of the “organizational” Hippocratic Oath and “First do no harm.”

Put another way, in the context of the success SHM has enjoyed for the past 10 years, there is a case to be made for standing out of the way of our society’s positive momentum. But I believe we can—and will—do better than that. None of us can afford to be spectators in this arena.

We often speak of teamwork in healthcare, but precious few of us intuitively know what this means—much less have any education in its principles. During my training, the idea of teamwork amounted to little more than relying on a medical assistant to obtain daily weights or counting on the pharmacist to calculate and follow the appropriate dosing schedule for gentamicin. Common sense led me to understand that building an amicable relationship with the nursing staff made my working life easier.

Slowly, the advantages of structuring a more organized team in the hospital setting became more evident and helped encourage me to find ways of exploiting this concept further. As I look back, it was Jeff Dichter, MD, past president of SHM and director of the hospitalist program at Ball Memorial Hospital in Muncie, Ind., who emerged as one of the true champions for teamwork as an optimal model for inpatient care. Jeff would talk about it to everyone who would listen, in every venue he could reach. He wrote about it in this very column. He charged our meeting planners and committee chairs with integrating teamwork principles into our educational content as well as our advocacy and membership development initiatives. His vision of a true team galvanized SHM’s commitment to supporting a broad constituency, extending well beyond hospitalist physicians. Jeff knew care is never delivered by an individual; it’s always a team. And he believed this framework to be fully realized by way of building from a strong organizational agenda for quality improvement.

Speaking of quality in healthcare, I look no further than Mark Williams, MD, editor of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, for having built that agenda for our society through his own efforts as well as collaboration with the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) and other national entities. As another past president of SHM, Mark brought a level of organizational focus and rigor around quality improvement and patient safety that rose to the challenges outlined in two Institute of Medicine reports, “To Err is Human” and “Crossing the Quality Chasm.” He helped move “quality” from something we talk about to something we do. He pushed it from an espoused value to a core commitment of our specialty. Quality improvement is now inseparable from what I consider to be the true promise of hospital medicine: that care organized in well-orchestrated, well-resourced teams can deliver our patients remarkable improvements in the quality, safety, and experience of healthcare.

But how do we get this done? How do we take a relatively abstract notion of a team, channel its activities to drive measurable improvements in quality, and change the arcane systems of inpatient care so as to sustain and hardwire those improvements?

Leadership. Like it or not, each of you is regarded as one of—if not the—most important leaders in the hospital. Nursing, case management, physical therapy, patients, and families look to you to provide leadership for clinical and operational systems. You are the person most able to make meaningful decisions at the front-line level that directly affect the patient experience. You are called upon to lead and manage change in a volatile environment, to resolve the inevitable conflicts that change provokes, and to reconcile hospital business drivers with quality and safety imperatives.

Our immediate past president, Dr. Gorman, emphasized the crucial role we serve as leaders. Recognizing the tremendous development needs for skills and knowledge to effectively lead, SHM has created Leadership Academies and is working on e-discussion forums and mentoring programs to promote longitudinal learning. While we must unlearn some of the behaviors and beliefs seared into our brains during our traditional medical training, we must position ourselves to forge high-performing teams and lead the quality agenda.

At a dinner during the SHM Annual Meeting in May, I sat with a senior leader from the American Medical Association’s Organized Medical Staff Section (AMA OMSS). He had flown in with other AMA representatives to meet with us on common interests. By the end of the evening, the late-career surgeon took me aside and said: “I have to tell you how touched I am by your organization. The passion, drive, and commitment of your membership is what’s missing in so many professional societies today. You must bring this passion to the larger house of medicine.”

As SHM enjoys 10 years of explosive growth and remarkable success, we need to balance the right to celebrate success with the duty not to rest on laurels. Much has been accomplished, but more than a life’s work lies before us. The road is complex and fraught with uncertainty. We might become frustrated with mounting complexity, tired with resistance to change, and fatigued with leading against the status quo. It is hard—and lonely—to confront the systems and issues that desperately need to be confronted on our journey to transform care. And it might be easy for us to become distracted from our core commitments to teamwork and leading quality by allowing our medical society to become more of a guild that defends our professional incomes and way of life. Yet I believe—I know—a much brighter future lies ahead than emerging as a casualty of temptation.

If the best predictor of behavior is past behavior, then our future will mirror the spirit in which SHM was founded. It’s the spirit an invited guest observed in a few short hours at our annual meeting. It’s the spirit that binds teamwork, quality improvement, and leadership into a unified approach to our professional endeavors. That spirit has a name: accountability. It’s the fundamental understanding that we are answerable to others, including patients, families, the community, hospital and medical staff, as well as each other, for the performance of the care systems in which we work.

Being accountable means we must rebuild trust of the broader public in hospital care, and that we follow through on the promise of hospital medicine. It means we own our mistakes, we agree that transparency and measurement will lead to better outcomes, and we commit to being part of the solution.

Accountability also mandates that we eliminate blame and “victimhood.” We cannot first think of ourselves as victims of a broken reimbursement model, or a lack of data or a hospital administration that “just doesn’t get it.” The real questions are: What can I do today about improving management of scarce resources? About the nursing shortage? About incorporating patient-safety principles into a new facility? About access to care and overcrowding? About the needless hospital deaths due to ventilator-assisted pneumonia (VAP), acute myocardial infarction, and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus? About ensuring seamless transitions of patients throughout the care continuum?

Several years ago I spoke with Brent James, MD, executive director of the Institute for Health Care Delivery Research and vice president of medical research and continuing medical education at InterMountain Healthcare in Salt Lake City, Utah. At the time, I was trying to learn quality improvement methods and practices. He reminded me of a quote Sir William Osler, the father of internal medicine, made at the end of his career when he gave an address at the Phipps Clinic in England to a group of young physicians who had recently completed training. They were about to embark on their careers early in the 20th century. “I am sorry for you young men of this generation,” he told the physicians. “Oh, you’ll do great things. You’ll have great victories, and standing on our shoulders you’ll see far. But you can never have our sensations. To have lived through a revolution, to have seen a new birth of science, new dispensation of health, redesigned medical training, remodeled hospitals, a new outlook for humanity. That is not given to every generation.”

While it seems appropriate in retrospect that these young physicians were indeed entering a time after which tremendous change and transformation had taken place, it seems equally appropriate to consider ourselves one of those generations that must lead and drive change of the magnitude of which Osler spoke. As we lead teams in the hospital to revolutionize the state of healthcare quality, we must begin every thought, every action, by holding ourselves and each other accountable for being part of the solution. To begin, we need look no further than ourselves. TH

Dr. Holman is president of SHM.

As I follow Mary Jo Gorman, MD, MBA, as president of SHM, it might be tempting for me to simply follow the leading rule of the “organizational” Hippocratic Oath and “First do no harm.”

Put another way, in the context of the success SHM has enjoyed for the past 10 years, there is a case to be made for standing out of the way of our society’s positive momentum. But I believe we can—and will—do better than that. None of us can afford to be spectators in this arena.

We often speak of teamwork in healthcare, but precious few of us intuitively know what this means—much less have any education in its principles. During my training, the idea of teamwork amounted to little more than relying on a medical assistant to obtain daily weights or counting on the pharmacist to calculate and follow the appropriate dosing schedule for gentamicin. Common sense led me to understand that building an amicable relationship with the nursing staff made my working life easier.

Slowly, the advantages of structuring a more organized team in the hospital setting became more evident and helped encourage me to find ways of exploiting this concept further. As I look back, it was Jeff Dichter, MD, past president of SHM and director of the hospitalist program at Ball Memorial Hospital in Muncie, Ind., who emerged as one of the true champions for teamwork as an optimal model for inpatient care. Jeff would talk about it to everyone who would listen, in every venue he could reach. He wrote about it in this very column. He charged our meeting planners and committee chairs with integrating teamwork principles into our educational content as well as our advocacy and membership development initiatives. His vision of a true team galvanized SHM’s commitment to supporting a broad constituency, extending well beyond hospitalist physicians. Jeff knew care is never delivered by an individual; it’s always a team. And he believed this framework to be fully realized by way of building from a strong organizational agenda for quality improvement.

Speaking of quality in healthcare, I look no further than Mark Williams, MD, editor of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, for having built that agenda for our society through his own efforts as well as collaboration with the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) and other national entities. As another past president of SHM, Mark brought a level of organizational focus and rigor around quality improvement and patient safety that rose to the challenges outlined in two Institute of Medicine reports, “To Err is Human” and “Crossing the Quality Chasm.” He helped move “quality” from something we talk about to something we do. He pushed it from an espoused value to a core commitment of our specialty. Quality improvement is now inseparable from what I consider to be the true promise of hospital medicine: that care organized in well-orchestrated, well-resourced teams can deliver our patients remarkable improvements in the quality, safety, and experience of healthcare.

But how do we get this done? How do we take a relatively abstract notion of a team, channel its activities to drive measurable improvements in quality, and change the arcane systems of inpatient care so as to sustain and hardwire those improvements?

Leadership. Like it or not, each of you is regarded as one of—if not the—most important leaders in the hospital. Nursing, case management, physical therapy, patients, and families look to you to provide leadership for clinical and operational systems. You are the person most able to make meaningful decisions at the front-line level that directly affect the patient experience. You are called upon to lead and manage change in a volatile environment, to resolve the inevitable conflicts that change provokes, and to reconcile hospital business drivers with quality and safety imperatives.

Our immediate past president, Dr. Gorman, emphasized the crucial role we serve as leaders. Recognizing the tremendous development needs for skills and knowledge to effectively lead, SHM has created Leadership Academies and is working on e-discussion forums and mentoring programs to promote longitudinal learning. While we must unlearn some of the behaviors and beliefs seared into our brains during our traditional medical training, we must position ourselves to forge high-performing teams and lead the quality agenda.

At a dinner during the SHM Annual Meeting in May, I sat with a senior leader from the American Medical Association’s Organized Medical Staff Section (AMA OMSS). He had flown in with other AMA representatives to meet with us on common interests. By the end of the evening, the late-career surgeon took me aside and said: “I have to tell you how touched I am by your organization. The passion, drive, and commitment of your membership is what’s missing in so many professional societies today. You must bring this passion to the larger house of medicine.”

As SHM enjoys 10 years of explosive growth and remarkable success, we need to balance the right to celebrate success with the duty not to rest on laurels. Much has been accomplished, but more than a life’s work lies before us. The road is complex and fraught with uncertainty. We might become frustrated with mounting complexity, tired with resistance to change, and fatigued with leading against the status quo. It is hard—and lonely—to confront the systems and issues that desperately need to be confronted on our journey to transform care. And it might be easy for us to become distracted from our core commitments to teamwork and leading quality by allowing our medical society to become more of a guild that defends our professional incomes and way of life. Yet I believe—I know—a much brighter future lies ahead than emerging as a casualty of temptation.

If the best predictor of behavior is past behavior, then our future will mirror the spirit in which SHM was founded. It’s the spirit an invited guest observed in a few short hours at our annual meeting. It’s the spirit that binds teamwork, quality improvement, and leadership into a unified approach to our professional endeavors. That spirit has a name: accountability. It’s the fundamental understanding that we are answerable to others, including patients, families, the community, hospital and medical staff, as well as each other, for the performance of the care systems in which we work.

Being accountable means we must rebuild trust of the broader public in hospital care, and that we follow through on the promise of hospital medicine. It means we own our mistakes, we agree that transparency and measurement will lead to better outcomes, and we commit to being part of the solution.