Discussion

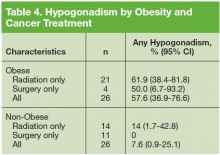

To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study to assess the prevalence of hypogonadism in treated low-risk PCa survivors. In this sample of 52 men in an outpatient setting, about 1 in 3 had low testosterone levels. Three patients had primary hypogonadism, and 14 had secondary

(hypogonadotrophic) hypogonadism. Obese patients were significantly more likely to have hypogonadism than were nonobese patients. There was no evidence of an associationbetween PCa treatment and hypogonadism.

Estimates of prevalence of hypogonadism in the general population vary in the literature based on different patient demographics, study designs, and geography. A recent review found that the prevalence of hypogonadism in adult men ≥ 18 years had a range of 2.1% to 31.2% since the authors included studies that were population-based, community-based, and primary care or screening-based. 14 The prevalence of hypogonadism was 15.0% to 78.8% in obese people and 21.4% to 33% in men with newly diagnosed PCa. 14

Mulligan and colleagues estimated that 38.7% of men aged ≥ 45 years who visited primary care clinics in the U.S. had hypogonadism. 15 They also found that the prevalence of hypogonadism, defined as serum T < 300 ng/dL, was significantly higher in men with obesity, DM, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and prostate disease. The prevalence of hypogonadism in this study was slightly lower (32.6%), but the authors used a different serum T level (< 250 ng/dL).15 Using the Mulligan and colleagues’ definition of serum T level, there was a prevalence of 40.3% in this study’s population of men with treated low-risk PCa.

Other patient characteristics were examined to determine whether the prevalence of hypogonadism differed by age, tumor stage, or mode of treatment. Testosterone levels drop in all men, 1% per year on average after age 30 years. 15 Hypogonadism has been consistently found to increase with age and certain comorbidities. Zarotsky and colleagues found a 17% increase in the risk for hypogonadism with every 10-year increase in age. 14 In this study, the authors did not find a significant difference in the prevalence of hypogonadism in this group by age or DM.

In the Prostate Cancer Outcomes Study (PCOS), the prevalence of erectile dysfunction was almost 90% in the prostatectomy and radiotherapy group after 15 years. It was unclear whether this was due to PCa and its treatment, the normal aging process, or a combination of factors, but no significant differences were observed between the treatment groups. However, it is unclear whether the PCOS men had hypogonadism, because testosterone levels were not reported. 16

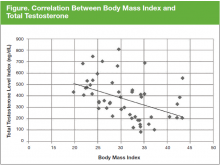

In the current study, the association between obesity and hypogonadism is consistent with epidemiologic evidence that suggests complex multidirectional interactions between testosterone, sex hormone-binding globulin, obesity, metabolic syndrome, and type 2 DM (T2DM), mediated by cytokines and adipokines. Several studies show that obesity adversely affects testicular function and is associated with a reduction in sex hormone-binding globulin, serum T, and free testosterone levels. 17,18 In addition, secondary hypogonadism has been shown to be higher in men who are overweight (25-29 kg/m2 BMI) and obese (≥ 30 kg/ m2 BMI) compared with normal weight men. 19,20 Hypogonadism has also been shown to increase insulin resistance, thereby increasing the risk for developing metabolic syndrome, which is a precursor for cardiovascular disease (CVD) and T2DM. 21 Furthermore, low testosterone concentration may be associated with increased insulin resistance, incidence of CVD events, anemia, and low bone density. 19,22,23