Mucorales fungi are ubiquitous organisms commonly inhabiting soil and can cause opportunistic infections. The majority of infections are caused by 3 genera: Rhizopus, Mucor, and Rhizomucor.1 Infection occurs by inhalation or by direct contact with damaged skin. Mucorales infections can have cutaneous, rhinocerebral, pulmonary, gastrointestinal, and central nervous system manifestations. Pulmonary mucormycosis is often rapidly progressive with angioinvasion and fulminant necrosis causing acute dyspnea, hemoptysis, and chest pain. More indolent pulmonary Mucorales infections can mimic a pulmonary mass with occasional cavitation found on imaging studies similar to other fungal infections (eg, Aspergillus).2 Risk factors include severe uncontrolled diabetes mellitus (DM), recurrent diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), immunosuppression due to congenital or acquired causes, hematologic malignancies, and chronic renal failure.3 The authors present a case of a patient with recurrent DKA and pulmonary mucormycosis.

Case Presentation

A 62-year-old male with DM and a more than 30-pack-year smoking history presented to the emergency department with abdominal pain and chest pain ongoing for about 1 week. The patient had a history of frequent admissions with DKA and medication nonadherence.

On admission, the patient was hemodynamically stable. His vital signs were: temperature 97.4° F, heart rate 89 bpm, respirations 24 breathes per minute, blood pressure 146/86 mm Hg, and oxygen saturation 94% on ambient air. The patient appeared ill but the physical examination was otherwise unremarkable. Laboratory results revealed a white blood cell count of 24,400 with neutrophilic predominance, blood glucose 658 mg/dL, creatinine clearance 2.16 mL/min/1.73 m2, sodium level 124 mEq/L, bicarbonate 6 mEq/L, anion gap 27 mEq/L, 6.8 pH, partial pressure of CO2 11 mm Hg, and lactic acid 2.3 mmol/L.

The patient admitted for DKA management and placed on an insulin drip. Although he did not have a fever or cough productive of sputum or hemoptysis, there was concern that pneumonia might have precipitated DKA. A chest X-ray revealed a patchy, right suprahilar opacity (Figure 1).

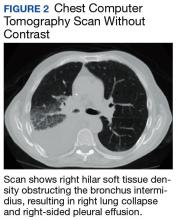

The patient was placed on vancomycin 1,000 mg every 12 hours and cefepime 2,000 mg every 12 hours for possible hospital-acquired pneumonia because of his history of recent DKA hospitalization. Once the patient’s anion gap was closed and metabolic acidosis was resolved, the insulin drip was discontinued, and the patient was transferred to the general medical ward for further management. There, he continued to report having chest pain. A computed tomography (CT) scan without contrast of the chest (contrast was held due to recent acute kidney injury) revealed right hilar soft tissue density obstructing the bronchus intermidius, which had resulted in a right-lung collapse and right-sided pleural effusion (Figure 2). The left lung was clear, and there was no evidence of nodularity.

Given the patient’s extensive smoking history, the initial concern was for pulmonary malignancy. The decision was made to proceed with bronchoscopy with endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle biopsy. Endobronchial brushings and biopsies of R11, 7, right bronchus intermedius, and right upper lobe were obtained. Gross inspection of the airway revealed markedly abnormal-appearing mucosa involving the take off to the right upper lobe and the entire bronchus intermedius with friable, cobblestoned, and edematous mucosa. Biopsies and immunostaining for occult carcinoma markers, including CD-56, TTF-1, Synaptophysin A, chromogranin, AE1/AE3, and CK-5/6, were negative for malignancy. Final microbiologic analysis was positive for Mucor. There was no evidence of bacterial or mycobacterial growth.

Due to continued suspicion for malignancy and lack of histologic yield, the patient underwent a repeat endobronchial ultrasound-guided needle biopsy. On this occasion, gross inspection revealed significant mucosal necrosis and extensive, extrinsic bronchial compression starting from the right bronchial division and notable throughout the right middle and lower lobes (Figure 3).

Bronchial washings revealed necrotic material with rare fungal hyphae present. Biopsies yielded necrotic material or lung tissue containing nonseptate hyphae with rare, right-angle branching consistent with Mucor (Figures 4 and 5). Malignancy was not present in the specimens obtained.

Based on the bronchoscopy results, thoracic surgery and infectious disease specialists were consulted. Surgical intervention was not recommended because of concerns for potential postoperative complications. The infectious disease specialists recommended initiation of liposomal amphotericin B at 10 mg/kg/d. Magnetic resonance imaging of the head showed parietal lobe enhancement with restricted diffusion most consistent with prior infarct. Paranasal sinus disease also was demonstrated. The latter findings prompted further evaluation. The patient underwent right and left endoscopic resection of concha bullosa as well as left maxillary endoscopic antrostomy. Gross examination showed thick mucosa in left concha bullosa, polypoid changes anterior to bulla ethmoidalis, and clear left maxillary sinus. The procedure had to be aborted when the patient experienced cardiac arrest secondary to ventricular fibrillation; he was successfully resuscitated.

Samples from the contents of right and left sinuses as well as left concha bullosa were submitted to pathology, showing benign respiratory mucosa with chronic inflammation and foci of bone without fungal elements. There was no other evidence of disseminated mucormycosis. The patient had a prolonged hospital course complicated by progressive hypoxemia, acute kidney injury, and toxic metabolic encephalopathy. Three months after his original diagnosis, he sustained another cardiac arrest in the hospital. Shortly after achieving return of spontaneous circulation and initiation of invasive mechanical ventilation, the family elected to withdraw care. The family declined an autopsy.