User login

Rising Migraine Prevalence Observed in Denmark

LOS ANGELES – The lifetime prevalence of self-reported migraine in the general population rose considerably in a recent 8-year period, suggested a study of roughly 37,000 middle-aged adults in Denmark.

From 1994 to 2002, the proportion reporting that they had ever had migraine rose by 32%, from a prevalence of 18.5% to 24.5% (P less than .001), Dr. Han Le of the University of Copenhagen reported at the annual meeting of the American Headache Society.

By type, there was a 68% increase in the prevalence of migraine with aura (from 5.6% to 9.4%; P less than .001) and a 16% increase in the prevalence of migraine without aura (from 13% to 15.1%; P less than .001), although the latter remained considerably more common (BMJ 2012 July 2 [doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2012-000962]).

"So are we having a micro-epidemic? ... We do believe that there is an increase, but [it] may not be as high as we are finding," Dr. Le commented, noting that that short time span over which the change took place would favor environmental explanations over genetic ones.

"Some part may be explained by more awareness or increased medical consultation. We do know for a fact that medical consultation has increased in Denmark. But there aren’t any campaigns to make people more aware of migraine," she elaborated. "A small part of the subjects participated in both surveys, so perhaps when they saw the migraine questions for the first time, they kind of thought more about it and went to a physician. That’s hard to tell."

In additional study findings, low education and high physical workload and activity increased the risk only of migraine without aura, whereas low body mass index increased the risk only of migraine with aura. Thus "different environmental factors seem to increase the development of migraine with aura and migraine without aura," she commented.

The investigators analyzed data from the Danish Twin Study, in which 20- to 41-year-olds in the general population were asked if they had ever experienced migraine and, if so, if they had had antecedent visual disturbances. Analyses were based on data from 22,053 adults in 1994 and from 14,810 adults in 2002.

Age-stratified analyses showed that most of the increase occurred among individuals aged older than 32 years. There was a significant increase among men and women individually, with the relative increase comparable for the sexes.

The investigators conducted an additional analysis of migraine risk factors among 13,498 adults aged 18-41 years who were free of migraine in 1994 and completed surveys in both study years.

Results showed that these adults were more likely to develop migraine if they had low back pain (odds ratio, 1.3), low education (OR, 1.3), hard physical workload (OR, 1.1), hard physical activity (OR, 1.2), and a body mass index of less than 18.5 kg/m2 (OR, 1.3).

In stratified analyses, only one of these factors (low back pain) was a risk factor for both types of migraine, according to Dr. Le. Low education as well as high physical workload and activity were risk factors only for migraine without aura, whereas low BMI was a risk factor only for migraine with aura.

Dr. Le disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

LOS ANGELES – The lifetime prevalence of self-reported migraine in the general population rose considerably in a recent 8-year period, suggested a study of roughly 37,000 middle-aged adults in Denmark.

From 1994 to 2002, the proportion reporting that they had ever had migraine rose by 32%, from a prevalence of 18.5% to 24.5% (P less than .001), Dr. Han Le of the University of Copenhagen reported at the annual meeting of the American Headache Society.

By type, there was a 68% increase in the prevalence of migraine with aura (from 5.6% to 9.4%; P less than .001) and a 16% increase in the prevalence of migraine without aura (from 13% to 15.1%; P less than .001), although the latter remained considerably more common (BMJ 2012 July 2 [doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2012-000962]).

"So are we having a micro-epidemic? ... We do believe that there is an increase, but [it] may not be as high as we are finding," Dr. Le commented, noting that that short time span over which the change took place would favor environmental explanations over genetic ones.

"Some part may be explained by more awareness or increased medical consultation. We do know for a fact that medical consultation has increased in Denmark. But there aren’t any campaigns to make people more aware of migraine," she elaborated. "A small part of the subjects participated in both surveys, so perhaps when they saw the migraine questions for the first time, they kind of thought more about it and went to a physician. That’s hard to tell."

In additional study findings, low education and high physical workload and activity increased the risk only of migraine without aura, whereas low body mass index increased the risk only of migraine with aura. Thus "different environmental factors seem to increase the development of migraine with aura and migraine without aura," she commented.

The investigators analyzed data from the Danish Twin Study, in which 20- to 41-year-olds in the general population were asked if they had ever experienced migraine and, if so, if they had had antecedent visual disturbances. Analyses were based on data from 22,053 adults in 1994 and from 14,810 adults in 2002.

Age-stratified analyses showed that most of the increase occurred among individuals aged older than 32 years. There was a significant increase among men and women individually, with the relative increase comparable for the sexes.

The investigators conducted an additional analysis of migraine risk factors among 13,498 adults aged 18-41 years who were free of migraine in 1994 and completed surveys in both study years.

Results showed that these adults were more likely to develop migraine if they had low back pain (odds ratio, 1.3), low education (OR, 1.3), hard physical workload (OR, 1.1), hard physical activity (OR, 1.2), and a body mass index of less than 18.5 kg/m2 (OR, 1.3).

In stratified analyses, only one of these factors (low back pain) was a risk factor for both types of migraine, according to Dr. Le. Low education as well as high physical workload and activity were risk factors only for migraine without aura, whereas low BMI was a risk factor only for migraine with aura.

Dr. Le disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

LOS ANGELES – The lifetime prevalence of self-reported migraine in the general population rose considerably in a recent 8-year period, suggested a study of roughly 37,000 middle-aged adults in Denmark.

From 1994 to 2002, the proportion reporting that they had ever had migraine rose by 32%, from a prevalence of 18.5% to 24.5% (P less than .001), Dr. Han Le of the University of Copenhagen reported at the annual meeting of the American Headache Society.

By type, there was a 68% increase in the prevalence of migraine with aura (from 5.6% to 9.4%; P less than .001) and a 16% increase in the prevalence of migraine without aura (from 13% to 15.1%; P less than .001), although the latter remained considerably more common (BMJ 2012 July 2 [doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2012-000962]).

"So are we having a micro-epidemic? ... We do believe that there is an increase, but [it] may not be as high as we are finding," Dr. Le commented, noting that that short time span over which the change took place would favor environmental explanations over genetic ones.

"Some part may be explained by more awareness or increased medical consultation. We do know for a fact that medical consultation has increased in Denmark. But there aren’t any campaigns to make people more aware of migraine," she elaborated. "A small part of the subjects participated in both surveys, so perhaps when they saw the migraine questions for the first time, they kind of thought more about it and went to a physician. That’s hard to tell."

In additional study findings, low education and high physical workload and activity increased the risk only of migraine without aura, whereas low body mass index increased the risk only of migraine with aura. Thus "different environmental factors seem to increase the development of migraine with aura and migraine without aura," she commented.

The investigators analyzed data from the Danish Twin Study, in which 20- to 41-year-olds in the general population were asked if they had ever experienced migraine and, if so, if they had had antecedent visual disturbances. Analyses were based on data from 22,053 adults in 1994 and from 14,810 adults in 2002.

Age-stratified analyses showed that most of the increase occurred among individuals aged older than 32 years. There was a significant increase among men and women individually, with the relative increase comparable for the sexes.

The investigators conducted an additional analysis of migraine risk factors among 13,498 adults aged 18-41 years who were free of migraine in 1994 and completed surveys in both study years.

Results showed that these adults were more likely to develop migraine if they had low back pain (odds ratio, 1.3), low education (OR, 1.3), hard physical workload (OR, 1.1), hard physical activity (OR, 1.2), and a body mass index of less than 18.5 kg/m2 (OR, 1.3).

In stratified analyses, only one of these factors (low back pain) was a risk factor for both types of migraine, according to Dr. Le. Low education as well as high physical workload and activity were risk factors only for migraine without aura, whereas low BMI was a risk factor only for migraine with aura.

Dr. Le disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

AT THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE AMERICAN HEADACHE SOCIETY

Major Finding: From 1994 to 2002, the lifetime prevalence of self-reported migraine increased from 18.5% to 24.5% (P less than .001), with increases for both migraine with aura and migraine without aura individually.

Data Source: This was an observational study of 36,863 young and middle-aged adults from the Danish general population.

Disclosures: Dr. Le disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

Secondary Headaches Flag Medical Conditions in Pregnancy

LOS ANGELES – Secondary headaches in pregnant women are likely to be associated with an additional medical complaint, according to a retrospective study of patients who presented to a tertiary-care center.

A team led by Dr. Matthew S. Robbins of Montefiore Headache Center in the Bronx, N.Y., assessed characteristics of 68 consecutive women who had an inpatient neurologic consultation for acute headache in pregnancy over a 2.5-year period at Montefiore Medical Center.

Secondary headaches were diagnosed in 57% of these women. Women with secondary headaches were more likely to have hypertension and some other chief complaint along with headache. Women with primary headaches were more likely to have a history of migraine and to have photophobia, phonophobia, and lacrimation on exam.

Three cases (4%) were noteworthy in that the headache led to discovery of an unrecognized pregnancy. All of these patients had secondary headache, and life-threatening but treatable medical conditions.

"In the acute care setting, vigilance for secondary headache in the pregnant population should be heightened, particularly in those patients who may have headache in addition to other symptoms, the lack of a migraine history, and elevated blood pressure acutely," Dr. Robbins recommended. "Because of our sad corollary [of three cases], we should ... always consider a pregnancy test in all women presenting with headache during childbearing years."

He acknowledged that a study limitation was the highly selected patient population. "This is not only patients presenting to the acute care setting, but patients who are then referred by the [emergency department] doctors or obstetricians for a neurologic consultation. So we are probably not capturing the routine cases of preeclampsia that are obvious, or other diagnoses that, in our center, the obstetricians don’t feel warrant neurologic consultation," he commented at the annual meeting of the American Headache Society.

Session attendee Dr. Peter J. Goadsby of the University of California, San Francisco, noted that about a fifth of patients with primary headache were classified as having an abnormal neurologic exam. "That wouldn’t be consistent with primary headache, would it? So what’s abnormal mean?" he asked.

"Most of the abnormal exam findings in the primary headache group were sensory abnormalities," such as unilateral facial numbness, which – although documented as abnormal – might not be clinically relevant. "It was up to the discretion of the treating team whether that patient had a primary or secondary diagnosis with the exam and abnormality combined," Dr. Robbins replied.

"Clinical experience, at least ours, suggests that consultation in the acute care setting for headache in pregnant women is not such an uncommon experience," he noted, explaining the study’s rationale. However, "there are very few guidelines that address this. It is mostly review articles in the obstetrics and gynecology literature that are not really validated, and clinical series are not well reported."

On average, the 68 women the investigators studied were 29 years old, and they were predominantly Hispanic (43%) and black (41%). The mean gestational age was 28.6 weeks, with 60% of women in their third trimester.

In terms of diagnoses, made via the ICHD-II (International Classification of Headache Disorders, second edition) system, 57% of the women had secondary headache and 43% had primary headache.

Headache class was predominantly migraine (43%), preeclampsia or eclampsia (25%), intercurrent infection (7%), and pituitary adenoma/apoplexy (6%).

The patients with primary headache and the patients with secondary headache were statistically indistinguishable in terms of most demographic, pregnancy, and clinical characteristics, according to Dr. Robbins.

But patients in the secondary headache group were less likely to have a history of migraine (39% vs. 90%; P less than .0001) and, on exam, photophobia (67% vs. 93%; P = .02), phonophobia (36% vs. 79%; P = .0004), and lacrimation (0% vs. 17%; P = .01).

On the flip side, those in the secondary headache group were more likely to have headache plus some other chief complaint such as seizure, shortness of breath, or visual disturbances (54% vs. 14%; P = .0009) and hypertension (49% vs. 0%; P less than .0001).

Of the three cases in which headache led to the discovery of an unrecognized pregnancy, one had diagnoses of PRES (posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome) and eclampsia; one had diagnoses of PRES, RCVS (reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome), and eclampsia; and one had diagnoses of hyperkalemia and renal failure in systemic lupus erythematous.

Dr. Robbins disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

LOS ANGELES – Secondary headaches in pregnant women are likely to be associated with an additional medical complaint, according to a retrospective study of patients who presented to a tertiary-care center.

A team led by Dr. Matthew S. Robbins of Montefiore Headache Center in the Bronx, N.Y., assessed characteristics of 68 consecutive women who had an inpatient neurologic consultation for acute headache in pregnancy over a 2.5-year period at Montefiore Medical Center.

Secondary headaches were diagnosed in 57% of these women. Women with secondary headaches were more likely to have hypertension and some other chief complaint along with headache. Women with primary headaches were more likely to have a history of migraine and to have photophobia, phonophobia, and lacrimation on exam.

Three cases (4%) were noteworthy in that the headache led to discovery of an unrecognized pregnancy. All of these patients had secondary headache, and life-threatening but treatable medical conditions.

"In the acute care setting, vigilance for secondary headache in the pregnant population should be heightened, particularly in those patients who may have headache in addition to other symptoms, the lack of a migraine history, and elevated blood pressure acutely," Dr. Robbins recommended. "Because of our sad corollary [of three cases], we should ... always consider a pregnancy test in all women presenting with headache during childbearing years."

He acknowledged that a study limitation was the highly selected patient population. "This is not only patients presenting to the acute care setting, but patients who are then referred by the [emergency department] doctors or obstetricians for a neurologic consultation. So we are probably not capturing the routine cases of preeclampsia that are obvious, or other diagnoses that, in our center, the obstetricians don’t feel warrant neurologic consultation," he commented at the annual meeting of the American Headache Society.

Session attendee Dr. Peter J. Goadsby of the University of California, San Francisco, noted that about a fifth of patients with primary headache were classified as having an abnormal neurologic exam. "That wouldn’t be consistent with primary headache, would it? So what’s abnormal mean?" he asked.

"Most of the abnormal exam findings in the primary headache group were sensory abnormalities," such as unilateral facial numbness, which – although documented as abnormal – might not be clinically relevant. "It was up to the discretion of the treating team whether that patient had a primary or secondary diagnosis with the exam and abnormality combined," Dr. Robbins replied.

"Clinical experience, at least ours, suggests that consultation in the acute care setting for headache in pregnant women is not such an uncommon experience," he noted, explaining the study’s rationale. However, "there are very few guidelines that address this. It is mostly review articles in the obstetrics and gynecology literature that are not really validated, and clinical series are not well reported."

On average, the 68 women the investigators studied were 29 years old, and they were predominantly Hispanic (43%) and black (41%). The mean gestational age was 28.6 weeks, with 60% of women in their third trimester.

In terms of diagnoses, made via the ICHD-II (International Classification of Headache Disorders, second edition) system, 57% of the women had secondary headache and 43% had primary headache.

Headache class was predominantly migraine (43%), preeclampsia or eclampsia (25%), intercurrent infection (7%), and pituitary adenoma/apoplexy (6%).

The patients with primary headache and the patients with secondary headache were statistically indistinguishable in terms of most demographic, pregnancy, and clinical characteristics, according to Dr. Robbins.

But patients in the secondary headache group were less likely to have a history of migraine (39% vs. 90%; P less than .0001) and, on exam, photophobia (67% vs. 93%; P = .02), phonophobia (36% vs. 79%; P = .0004), and lacrimation (0% vs. 17%; P = .01).

On the flip side, those in the secondary headache group were more likely to have headache plus some other chief complaint such as seizure, shortness of breath, or visual disturbances (54% vs. 14%; P = .0009) and hypertension (49% vs. 0%; P less than .0001).

Of the three cases in which headache led to the discovery of an unrecognized pregnancy, one had diagnoses of PRES (posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome) and eclampsia; one had diagnoses of PRES, RCVS (reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome), and eclampsia; and one had diagnoses of hyperkalemia and renal failure in systemic lupus erythematous.

Dr. Robbins disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

LOS ANGELES – Secondary headaches in pregnant women are likely to be associated with an additional medical complaint, according to a retrospective study of patients who presented to a tertiary-care center.

A team led by Dr. Matthew S. Robbins of Montefiore Headache Center in the Bronx, N.Y., assessed characteristics of 68 consecutive women who had an inpatient neurologic consultation for acute headache in pregnancy over a 2.5-year period at Montefiore Medical Center.

Secondary headaches were diagnosed in 57% of these women. Women with secondary headaches were more likely to have hypertension and some other chief complaint along with headache. Women with primary headaches were more likely to have a history of migraine and to have photophobia, phonophobia, and lacrimation on exam.

Three cases (4%) were noteworthy in that the headache led to discovery of an unrecognized pregnancy. All of these patients had secondary headache, and life-threatening but treatable medical conditions.

"In the acute care setting, vigilance for secondary headache in the pregnant population should be heightened, particularly in those patients who may have headache in addition to other symptoms, the lack of a migraine history, and elevated blood pressure acutely," Dr. Robbins recommended. "Because of our sad corollary [of three cases], we should ... always consider a pregnancy test in all women presenting with headache during childbearing years."

He acknowledged that a study limitation was the highly selected patient population. "This is not only patients presenting to the acute care setting, but patients who are then referred by the [emergency department] doctors or obstetricians for a neurologic consultation. So we are probably not capturing the routine cases of preeclampsia that are obvious, or other diagnoses that, in our center, the obstetricians don’t feel warrant neurologic consultation," he commented at the annual meeting of the American Headache Society.

Session attendee Dr. Peter J. Goadsby of the University of California, San Francisco, noted that about a fifth of patients with primary headache were classified as having an abnormal neurologic exam. "That wouldn’t be consistent with primary headache, would it? So what’s abnormal mean?" he asked.

"Most of the abnormal exam findings in the primary headache group were sensory abnormalities," such as unilateral facial numbness, which – although documented as abnormal – might not be clinically relevant. "It was up to the discretion of the treating team whether that patient had a primary or secondary diagnosis with the exam and abnormality combined," Dr. Robbins replied.

"Clinical experience, at least ours, suggests that consultation in the acute care setting for headache in pregnant women is not such an uncommon experience," he noted, explaining the study’s rationale. However, "there are very few guidelines that address this. It is mostly review articles in the obstetrics and gynecology literature that are not really validated, and clinical series are not well reported."

On average, the 68 women the investigators studied were 29 years old, and they were predominantly Hispanic (43%) and black (41%). The mean gestational age was 28.6 weeks, with 60% of women in their third trimester.

In terms of diagnoses, made via the ICHD-II (International Classification of Headache Disorders, second edition) system, 57% of the women had secondary headache and 43% had primary headache.

Headache class was predominantly migraine (43%), preeclampsia or eclampsia (25%), intercurrent infection (7%), and pituitary adenoma/apoplexy (6%).

The patients with primary headache and the patients with secondary headache were statistically indistinguishable in terms of most demographic, pregnancy, and clinical characteristics, according to Dr. Robbins.

But patients in the secondary headache group were less likely to have a history of migraine (39% vs. 90%; P less than .0001) and, on exam, photophobia (67% vs. 93%; P = .02), phonophobia (36% vs. 79%; P = .0004), and lacrimation (0% vs. 17%; P = .01).

On the flip side, those in the secondary headache group were more likely to have headache plus some other chief complaint such as seizure, shortness of breath, or visual disturbances (54% vs. 14%; P = .0009) and hypertension (49% vs. 0%; P less than .0001).

Of the three cases in which headache led to the discovery of an unrecognized pregnancy, one had diagnoses of PRES (posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome) and eclampsia; one had diagnoses of PRES, RCVS (reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome), and eclampsia; and one had diagnoses of hyperkalemia and renal failure in systemic lupus erythematous.

Dr. Robbins disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

AT THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE AMERICAN HEADACHE SOCIETY

Major Finding: Secondary headaches were seen in 57% of 68 consecutive women who had an inpatient neurologic consultation for acute headache in pregnancy.

Data Source: Researchers conducted a retrospective study of 68 women who were referred for inpatient neurologic consultation because of acute headache in pregnancy.

Disclosures: Dr. Robbins disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

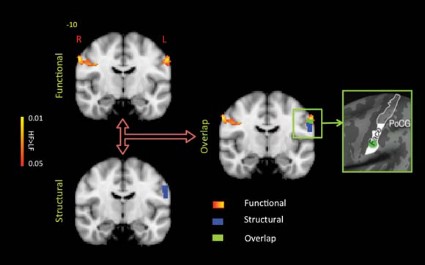

Doubt Cast on Discrete-Phase Nature of Migraine With Aura

LOS ANGELES – Contrasting with current classification criteria and the usual wisdom that attacks of migraine with aura have discrete phases, new data suggest that headache is more often than not already present during the aura phase.

In a prospective, diary-based study of 201 adults experiencing 861 attacks of migraine with aura, headache was reported within 15 minutes of the onset of aura in 61% of attacks, researchers reported at the annual meeting of the American Headache Society.

Additionally, more than half of the attacks met formal diagnostic criteria for migraine or pragmatic criteria for probable migraine within this time frame.

"These results do not seem to be consistent with the current ICHD-2 [International Classification of Headache Disorders, second edition] classification that states that migraine headache usually follows the aura symptoms; that’s not the case here," commented lead researcher Dr. Jakob M. Hansen of the headache research and treatment program at the University of California, Los Angeles and the Danish Headache Center at the University of Copenhagen.

"Furthermore, we have already headache at the onset of aura, and that does seem to conflict with the idea that you have to have a [cortical] spreading depression to activate the trigeminovascular system to cause headache."

"These data suggest that the phases of migraine attack may not be as discrete as originally believed. This is food for thought," he added.

Session attendee Dr. Jes Olesen, also of the University of Copenhagen, was skeptical of the findings, however, noting that they contrast with those of large studies in which careful histories were taken. "Always when you find something that is clearly in contrast to what is sort of conventional wisdom, we have to think about possible sources of error. ... My idea is it could be because people are mixing up a little bit attacks with and without aura ... because patients tend to mix these things up if you don’t instruct them very, very carefully," he said.

"The good thing is, for [patients] to report anything during the study, they should have an aura that they were familiar with to include an attack. I think it’s highly unlikely that people were having a migraine attack without aura. They were asked in the electronic diary, ‘Do you have an aura right now?’ " Dr. Hansen explained. "Of course it’s possible that they answered, ‘Yes, I do,’ because we reminded them. But I think it’s unlikely that so many patients would respond wrongly to a very simple question like that."

Dr. Werner Becker of the University of Calgary (Alta.), who also attended the session, commented that "migraine patients who have premonitory symptoms will often report nausea or photophobia or phonophobia even during their premonitory phase, so I’m not all that surprised that maybe symptoms are occurring during the aura as well.

"Having said that, your findings of so much headache during the aura are very interesting. But I suppose your results are consistent with the idea that the hypothalamus activation is perhaps the first part of the migraine attack," he added.

Dr. Hansen and his coinvestigators studied patients who were enrolled in a randomized therapeutic trial and had migraine with aura.

In the first phase of the study (456 attacks), patients reported the time elapsed since aura onset in quarter hours, as well as pain intensity and associated symptoms. In the second phase (405 attacks), they reported baseline pain and associated symptoms within 1 hour of aura onset, immediately before treatment.

Results showed that for 61% of attacks in the study’s first phase, headache was already present at 0-15 minutes after aura onset, Dr. Hansen reported. Patients also commonly had nausea (40%), photophobia (84%), and phonophobia (67%) at this very early phase.

Additionally, a large proportion of attacks met criteria for migraine with aura within 15 minutes of the onset of aura: 22% with use of the stricter ICHD-2 criteria for migraine with aura, and 54% with use of less strict, pragmatic criteria for probable migraine with aura (defined as migraine aura plus any-intensity headache plus at least one associated symptom among nausea/vomiting, photophobia, and phonophobia).

"These results were, of course, somewhat surprising to us because of the conflict with many of the firmly held beliefs" on migraine with aura, Dr. Hansen commented. Nonetheless, "it seems that headache and migraine symptoms are present during the aura phase."

(For all attacks studied, headache occurred within an hour of aura onset in 73%; some 31% met the ICHD-2 criteria for migraine with aura, whereas 65% met the pragmatic criteria for probable migraine with aura.)

Dr. Hansen disclosed no relevant financial conflicts of interest.

LOS ANGELES – Contrasting with current classification criteria and the usual wisdom that attacks of migraine with aura have discrete phases, new data suggest that headache is more often than not already present during the aura phase.

In a prospective, diary-based study of 201 adults experiencing 861 attacks of migraine with aura, headache was reported within 15 minutes of the onset of aura in 61% of attacks, researchers reported at the annual meeting of the American Headache Society.

Additionally, more than half of the attacks met formal diagnostic criteria for migraine or pragmatic criteria for probable migraine within this time frame.

"These results do not seem to be consistent with the current ICHD-2 [International Classification of Headache Disorders, second edition] classification that states that migraine headache usually follows the aura symptoms; that’s not the case here," commented lead researcher Dr. Jakob M. Hansen of the headache research and treatment program at the University of California, Los Angeles and the Danish Headache Center at the University of Copenhagen.

"Furthermore, we have already headache at the onset of aura, and that does seem to conflict with the idea that you have to have a [cortical] spreading depression to activate the trigeminovascular system to cause headache."

"These data suggest that the phases of migraine attack may not be as discrete as originally believed. This is food for thought," he added.

Session attendee Dr. Jes Olesen, also of the University of Copenhagen, was skeptical of the findings, however, noting that they contrast with those of large studies in which careful histories were taken. "Always when you find something that is clearly in contrast to what is sort of conventional wisdom, we have to think about possible sources of error. ... My idea is it could be because people are mixing up a little bit attacks with and without aura ... because patients tend to mix these things up if you don’t instruct them very, very carefully," he said.

"The good thing is, for [patients] to report anything during the study, they should have an aura that they were familiar with to include an attack. I think it’s highly unlikely that people were having a migraine attack without aura. They were asked in the electronic diary, ‘Do you have an aura right now?’ " Dr. Hansen explained. "Of course it’s possible that they answered, ‘Yes, I do,’ because we reminded them. But I think it’s unlikely that so many patients would respond wrongly to a very simple question like that."

Dr. Werner Becker of the University of Calgary (Alta.), who also attended the session, commented that "migraine patients who have premonitory symptoms will often report nausea or photophobia or phonophobia even during their premonitory phase, so I’m not all that surprised that maybe symptoms are occurring during the aura as well.

"Having said that, your findings of so much headache during the aura are very interesting. But I suppose your results are consistent with the idea that the hypothalamus activation is perhaps the first part of the migraine attack," he added.

Dr. Hansen and his coinvestigators studied patients who were enrolled in a randomized therapeutic trial and had migraine with aura.

In the first phase of the study (456 attacks), patients reported the time elapsed since aura onset in quarter hours, as well as pain intensity and associated symptoms. In the second phase (405 attacks), they reported baseline pain and associated symptoms within 1 hour of aura onset, immediately before treatment.

Results showed that for 61% of attacks in the study’s first phase, headache was already present at 0-15 minutes after aura onset, Dr. Hansen reported. Patients also commonly had nausea (40%), photophobia (84%), and phonophobia (67%) at this very early phase.

Additionally, a large proportion of attacks met criteria for migraine with aura within 15 minutes of the onset of aura: 22% with use of the stricter ICHD-2 criteria for migraine with aura, and 54% with use of less strict, pragmatic criteria for probable migraine with aura (defined as migraine aura plus any-intensity headache plus at least one associated symptom among nausea/vomiting, photophobia, and phonophobia).

"These results were, of course, somewhat surprising to us because of the conflict with many of the firmly held beliefs" on migraine with aura, Dr. Hansen commented. Nonetheless, "it seems that headache and migraine symptoms are present during the aura phase."

(For all attacks studied, headache occurred within an hour of aura onset in 73%; some 31% met the ICHD-2 criteria for migraine with aura, whereas 65% met the pragmatic criteria for probable migraine with aura.)

Dr. Hansen disclosed no relevant financial conflicts of interest.

LOS ANGELES – Contrasting with current classification criteria and the usual wisdom that attacks of migraine with aura have discrete phases, new data suggest that headache is more often than not already present during the aura phase.

In a prospective, diary-based study of 201 adults experiencing 861 attacks of migraine with aura, headache was reported within 15 minutes of the onset of aura in 61% of attacks, researchers reported at the annual meeting of the American Headache Society.

Additionally, more than half of the attacks met formal diagnostic criteria for migraine or pragmatic criteria for probable migraine within this time frame.

"These results do not seem to be consistent with the current ICHD-2 [International Classification of Headache Disorders, second edition] classification that states that migraine headache usually follows the aura symptoms; that’s not the case here," commented lead researcher Dr. Jakob M. Hansen of the headache research and treatment program at the University of California, Los Angeles and the Danish Headache Center at the University of Copenhagen.

"Furthermore, we have already headache at the onset of aura, and that does seem to conflict with the idea that you have to have a [cortical] spreading depression to activate the trigeminovascular system to cause headache."

"These data suggest that the phases of migraine attack may not be as discrete as originally believed. This is food for thought," he added.

Session attendee Dr. Jes Olesen, also of the University of Copenhagen, was skeptical of the findings, however, noting that they contrast with those of large studies in which careful histories were taken. "Always when you find something that is clearly in contrast to what is sort of conventional wisdom, we have to think about possible sources of error. ... My idea is it could be because people are mixing up a little bit attacks with and without aura ... because patients tend to mix these things up if you don’t instruct them very, very carefully," he said.

"The good thing is, for [patients] to report anything during the study, they should have an aura that they were familiar with to include an attack. I think it’s highly unlikely that people were having a migraine attack without aura. They were asked in the electronic diary, ‘Do you have an aura right now?’ " Dr. Hansen explained. "Of course it’s possible that they answered, ‘Yes, I do,’ because we reminded them. But I think it’s unlikely that so many patients would respond wrongly to a very simple question like that."

Dr. Werner Becker of the University of Calgary (Alta.), who also attended the session, commented that "migraine patients who have premonitory symptoms will often report nausea or photophobia or phonophobia even during their premonitory phase, so I’m not all that surprised that maybe symptoms are occurring during the aura as well.

"Having said that, your findings of so much headache during the aura are very interesting. But I suppose your results are consistent with the idea that the hypothalamus activation is perhaps the first part of the migraine attack," he added.

Dr. Hansen and his coinvestigators studied patients who were enrolled in a randomized therapeutic trial and had migraine with aura.

In the first phase of the study (456 attacks), patients reported the time elapsed since aura onset in quarter hours, as well as pain intensity and associated symptoms. In the second phase (405 attacks), they reported baseline pain and associated symptoms within 1 hour of aura onset, immediately before treatment.

Results showed that for 61% of attacks in the study’s first phase, headache was already present at 0-15 minutes after aura onset, Dr. Hansen reported. Patients also commonly had nausea (40%), photophobia (84%), and phonophobia (67%) at this very early phase.

Additionally, a large proportion of attacks met criteria for migraine with aura within 15 minutes of the onset of aura: 22% with use of the stricter ICHD-2 criteria for migraine with aura, and 54% with use of less strict, pragmatic criteria for probable migraine with aura (defined as migraine aura plus any-intensity headache plus at least one associated symptom among nausea/vomiting, photophobia, and phonophobia).

"These results were, of course, somewhat surprising to us because of the conflict with many of the firmly held beliefs" on migraine with aura, Dr. Hansen commented. Nonetheless, "it seems that headache and migraine symptoms are present during the aura phase."

(For all attacks studied, headache occurred within an hour of aura onset in 73%; some 31% met the ICHD-2 criteria for migraine with aura, whereas 65% met the pragmatic criteria for probable migraine with aura.)

Dr. Hansen disclosed no relevant financial conflicts of interest.

AT THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE AMERICAN HEADACHE SOCIETY

Major Finding: In 61% of attacks, headache was already present within 15 minutes of the onset of aura.

Data Source: This was a prospective, diary-based study of 201 adult patients experiencing 861 attacks of migraine with aura.

Disclosures: Dr. Hansen disclosed no relevant financial conflicts of interest.

Posttraumatic Headache More Common When Injury Is Mild

LOS ANGELES – The likelihood of headache after traumatic brain injury was inversely related to the severity of injury in a longitudinal study of 598 patients.

The patients with mild injury were about 70% more likely than were their counterparts with moderate or severe injury to develop new headache or have a worsening of preexisting headache over the next year, first author Dr. Sylvia Lucas reported at the annual meeting of the American Headache Society.

The majority of headaches were migraine or probable migraine according to the ICHD-2 (International Classification of Headache Disorders, second edition) system, but a large share – roughly a quarter – had features that defied classification. Patients with preexisting headache and female patients had a higher risk of posttraumatic headache.

"Using symptom-based criteria for headache after TBI [traumatic brain injury] hopefully may serve as a framework from which to provide evidence-based treatment," commented Dr. Lucas, clinical professor of neurology, rehabilitation medicine, and neurosurgery at the University of Washington in Seattle.

Session attendee Dr. Werner Becker of the University of Calgary (Alta.) asked, "Any thoughts as to why the patients with milder injuries have more headache?"

"I don’t know. It has to have something to do with the mechanics of the hit, I suspect," Dr. Lucas replied. "We’re just now trying to look at the types of injury. We’re trying to separate subarachnoid hemorrhage, depressed skull fracture, intracerebral hemorrhage, and trying to look at how they relate to the chronicity of the headache. But, as of now, I can’t answer that."

Dr. James R. Couch of the University of Oklahoma, Oklahoma City, who also attended the session, noted that he and his colleagues found a similar pattern in a previous study. "I was very gratified to see that what you are finding is the less severely injured people seem to have a greater propensity for headache," he said. "Maybe the severe brain injury takes out some kind of center that is involved in generating headache, whereas the mild head injury just irritates it."

The investigators studied a single-center cohort of 220 patients with mild TBI who were enrolled within a week of injury and a seven-center cohort of 378 patients with moderate to severe TBI who were admitted to inpatient rehabilitation facilities. All patients were evaluated with the same questionnaire, in person at baseline, and prospectively by telephone over a year, to gain a better understanding of headache incidence, characteristics, and predictors, and treatment effectiveness.

"We feel that the ICHD-2 criteria, both in the civilian and military populations, really don’t contribute to treatment planning," Dr. Lucas commented. "They also don’t account for the latency of posttraumatic headache following trauma," with experience suggesting that almost a third of headache cases do not come to clinical attention until more than 1 week after the injury, even though that is the window typically used to define posttraumatic headache.

Patients in both groups were about 43 years old, on average, and roughly three-quarters each were male and white, and had completed high school. The leading cause of injury was vehicular accident (58%) followed by falls (25%).

Study results showed that the mild TBI group and the moderate or severe TBI group had an identical prevalence of headache before injury (17%). But the former had a higher incidence of new or worsened headache at baseline (56% vs. 40%), at 3 months (63% vs. 37%), at 6 months (69% vs. 33%), and at 12 months (58% vs. 34%).

Headache was classified according to ICHD-2 criteria for primary headache, with only a single class permitted per patient, based on the predominant features, according to Dr. Lucas. "The idea behind classification of a secondary headache using primary headache criteria is really to try to find some defining features that may allow us to do what we want in the future, which is to get some evidence-based medicine treatment or management protocols," she explained.

At all time points and in both groups, the largest share of headaches (39%-67%) was of the migraine or probable migraine type. Tension headaches were the next most common type. "Surprisingly, cervicogenic was not very [common], particularly considering that many of these were motor vehicle accidents and probably involved whiplash-type injuries," she observed.

Roughly a quarter of headaches were unclassifiable. "We felt that rather than trying to use a shoehorn to fit the headache into a classification, if it didn’t fit, we just stayed with it and deemed it unclassifiable," Dr. Lucas commented.

In both the mild TBI group and the moderate to severe TBI group, the migraine and probable migraine headaches, in addition to being most common, were more likely than the other types of headache to occur daily or several times weekly.

Also, in both groups, patients who had a prior history of headache and female patients were more likely to have headache at follow-up. For example, in the mild TBI group, about 70% of patients who had preexisting headache had headache at all time points during follow-up, compared with about 50% of patients who did not have preexisting headache.

Dr. Lucas disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

LOS ANGELES – The likelihood of headache after traumatic brain injury was inversely related to the severity of injury in a longitudinal study of 598 patients.

The patients with mild injury were about 70% more likely than were their counterparts with moderate or severe injury to develop new headache or have a worsening of preexisting headache over the next year, first author Dr. Sylvia Lucas reported at the annual meeting of the American Headache Society.

The majority of headaches were migraine or probable migraine according to the ICHD-2 (International Classification of Headache Disorders, second edition) system, but a large share – roughly a quarter – had features that defied classification. Patients with preexisting headache and female patients had a higher risk of posttraumatic headache.

"Using symptom-based criteria for headache after TBI [traumatic brain injury] hopefully may serve as a framework from which to provide evidence-based treatment," commented Dr. Lucas, clinical professor of neurology, rehabilitation medicine, and neurosurgery at the University of Washington in Seattle.

Session attendee Dr. Werner Becker of the University of Calgary (Alta.) asked, "Any thoughts as to why the patients with milder injuries have more headache?"

"I don’t know. It has to have something to do with the mechanics of the hit, I suspect," Dr. Lucas replied. "We’re just now trying to look at the types of injury. We’re trying to separate subarachnoid hemorrhage, depressed skull fracture, intracerebral hemorrhage, and trying to look at how they relate to the chronicity of the headache. But, as of now, I can’t answer that."

Dr. James R. Couch of the University of Oklahoma, Oklahoma City, who also attended the session, noted that he and his colleagues found a similar pattern in a previous study. "I was very gratified to see that what you are finding is the less severely injured people seem to have a greater propensity for headache," he said. "Maybe the severe brain injury takes out some kind of center that is involved in generating headache, whereas the mild head injury just irritates it."

The investigators studied a single-center cohort of 220 patients with mild TBI who were enrolled within a week of injury and a seven-center cohort of 378 patients with moderate to severe TBI who were admitted to inpatient rehabilitation facilities. All patients were evaluated with the same questionnaire, in person at baseline, and prospectively by telephone over a year, to gain a better understanding of headache incidence, characteristics, and predictors, and treatment effectiveness.

"We feel that the ICHD-2 criteria, both in the civilian and military populations, really don’t contribute to treatment planning," Dr. Lucas commented. "They also don’t account for the latency of posttraumatic headache following trauma," with experience suggesting that almost a third of headache cases do not come to clinical attention until more than 1 week after the injury, even though that is the window typically used to define posttraumatic headache.

Patients in both groups were about 43 years old, on average, and roughly three-quarters each were male and white, and had completed high school. The leading cause of injury was vehicular accident (58%) followed by falls (25%).

Study results showed that the mild TBI group and the moderate or severe TBI group had an identical prevalence of headache before injury (17%). But the former had a higher incidence of new or worsened headache at baseline (56% vs. 40%), at 3 months (63% vs. 37%), at 6 months (69% vs. 33%), and at 12 months (58% vs. 34%).

Headache was classified according to ICHD-2 criteria for primary headache, with only a single class permitted per patient, based on the predominant features, according to Dr. Lucas. "The idea behind classification of a secondary headache using primary headache criteria is really to try to find some defining features that may allow us to do what we want in the future, which is to get some evidence-based medicine treatment or management protocols," she explained.

At all time points and in both groups, the largest share of headaches (39%-67%) was of the migraine or probable migraine type. Tension headaches were the next most common type. "Surprisingly, cervicogenic was not very [common], particularly considering that many of these were motor vehicle accidents and probably involved whiplash-type injuries," she observed.

Roughly a quarter of headaches were unclassifiable. "We felt that rather than trying to use a shoehorn to fit the headache into a classification, if it didn’t fit, we just stayed with it and deemed it unclassifiable," Dr. Lucas commented.

In both the mild TBI group and the moderate to severe TBI group, the migraine and probable migraine headaches, in addition to being most common, were more likely than the other types of headache to occur daily or several times weekly.

Also, in both groups, patients who had a prior history of headache and female patients were more likely to have headache at follow-up. For example, in the mild TBI group, about 70% of patients who had preexisting headache had headache at all time points during follow-up, compared with about 50% of patients who did not have preexisting headache.

Dr. Lucas disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

LOS ANGELES – The likelihood of headache after traumatic brain injury was inversely related to the severity of injury in a longitudinal study of 598 patients.

The patients with mild injury were about 70% more likely than were their counterparts with moderate or severe injury to develop new headache or have a worsening of preexisting headache over the next year, first author Dr. Sylvia Lucas reported at the annual meeting of the American Headache Society.

The majority of headaches were migraine or probable migraine according to the ICHD-2 (International Classification of Headache Disorders, second edition) system, but a large share – roughly a quarter – had features that defied classification. Patients with preexisting headache and female patients had a higher risk of posttraumatic headache.

"Using symptom-based criteria for headache after TBI [traumatic brain injury] hopefully may serve as a framework from which to provide evidence-based treatment," commented Dr. Lucas, clinical professor of neurology, rehabilitation medicine, and neurosurgery at the University of Washington in Seattle.

Session attendee Dr. Werner Becker of the University of Calgary (Alta.) asked, "Any thoughts as to why the patients with milder injuries have more headache?"

"I don’t know. It has to have something to do with the mechanics of the hit, I suspect," Dr. Lucas replied. "We’re just now trying to look at the types of injury. We’re trying to separate subarachnoid hemorrhage, depressed skull fracture, intracerebral hemorrhage, and trying to look at how they relate to the chronicity of the headache. But, as of now, I can’t answer that."

Dr. James R. Couch of the University of Oklahoma, Oklahoma City, who also attended the session, noted that he and his colleagues found a similar pattern in a previous study. "I was very gratified to see that what you are finding is the less severely injured people seem to have a greater propensity for headache," he said. "Maybe the severe brain injury takes out some kind of center that is involved in generating headache, whereas the mild head injury just irritates it."

The investigators studied a single-center cohort of 220 patients with mild TBI who were enrolled within a week of injury and a seven-center cohort of 378 patients with moderate to severe TBI who were admitted to inpatient rehabilitation facilities. All patients were evaluated with the same questionnaire, in person at baseline, and prospectively by telephone over a year, to gain a better understanding of headache incidence, characteristics, and predictors, and treatment effectiveness.

"We feel that the ICHD-2 criteria, both in the civilian and military populations, really don’t contribute to treatment planning," Dr. Lucas commented. "They also don’t account for the latency of posttraumatic headache following trauma," with experience suggesting that almost a third of headache cases do not come to clinical attention until more than 1 week after the injury, even though that is the window typically used to define posttraumatic headache.

Patients in both groups were about 43 years old, on average, and roughly three-quarters each were male and white, and had completed high school. The leading cause of injury was vehicular accident (58%) followed by falls (25%).

Study results showed that the mild TBI group and the moderate or severe TBI group had an identical prevalence of headache before injury (17%). But the former had a higher incidence of new or worsened headache at baseline (56% vs. 40%), at 3 months (63% vs. 37%), at 6 months (69% vs. 33%), and at 12 months (58% vs. 34%).

Headache was classified according to ICHD-2 criteria for primary headache, with only a single class permitted per patient, based on the predominant features, according to Dr. Lucas. "The idea behind classification of a secondary headache using primary headache criteria is really to try to find some defining features that may allow us to do what we want in the future, which is to get some evidence-based medicine treatment or management protocols," she explained.

At all time points and in both groups, the largest share of headaches (39%-67%) was of the migraine or probable migraine type. Tension headaches were the next most common type. "Surprisingly, cervicogenic was not very [common], particularly considering that many of these were motor vehicle accidents and probably involved whiplash-type injuries," she observed.

Roughly a quarter of headaches were unclassifiable. "We felt that rather than trying to use a shoehorn to fit the headache into a classification, if it didn’t fit, we just stayed with it and deemed it unclassifiable," Dr. Lucas commented.

In both the mild TBI group and the moderate to severe TBI group, the migraine and probable migraine headaches, in addition to being most common, were more likely than the other types of headache to occur daily or several times weekly.

Also, in both groups, patients who had a prior history of headache and female patients were more likely to have headache at follow-up. For example, in the mild TBI group, about 70% of patients who had preexisting headache had headache at all time points during follow-up, compared with about 50% of patients who did not have preexisting headache.

Dr. Lucas disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

AT THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE AMERICAN HEADACHE SOCIETY

Major Finding: The prevalence of new or worsened headache at 1 year after TBI was 58% in the cohort with mild injury, compared with 34% in the cohort with moderate or severe injury.

Data Source: This was a longitudinal study of two cohorts having a total of 598 patients with TBI.

Disclosures: Dr. Lucas disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

Acute Use of Rizatriptan for Migraine Safe, Effective in Teens

LOS ANGELES – Rizatriptan is safe and effective when used for intermittent treatment of migraine in adolescents on a long-term basis, according to a year-long, multicenter, open-label trial presented at the annual meeting of the American Headache Society.

Less than 1% of the 606 patients studied experienced serious drug-related adverse events. And all of these events were classified as serious because they occurred after accidental use of an extra dose of rizatriptan in a 24-hour period.

Additionally, in 46% of treated attacks, the patients were pain free at 2 hours after taking the medication, reported lead investigator Dr. Eric M. Pearlman of Children’s Hospital at Memorial University Medical Center, Savannah, Ga.

"Rizatriptan was generally safe and well tolerated in the long-term acute treatment of migraine in this adolescent population," he maintained. And "at least in an open-label fashion, it was effective."

Session attendee Dr. James R. Couch of the University of Oklahoma, Oklahoma City, commented, "That’s a very impressive pain-free number. ... The usual triptan gives us between 25% and 30% pain freedom. Do you have any comments on why children seem to respond much better?"

"I think it was because it was open label," Dr. Pearlman replied. "But this was done in conjunction with a single-attack, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial," he added. That trial, which led to regulatory approval of the drug for adolescents, had a run-in phase aimed at identifying and excluding placebo responders; the rate of pain freedom at 2 hours was 31% with rizatriptan.

Dr. Pearlman and his colleagues studied 12- to 17-years-olds in the United States and Europe who met diagnostic criteria for migraine and had not achieved a satisfactory response to treatment with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or acetaminophen.

They were assigned to the orally disintegrating tablet formulation of rizatriptan (Maxalt-MLT) based on weight: 5 mg if they weighed less than 40 kg, and 10 mg if they weighed 40 kg or more.

Patients were instructed to use the medication to treat up to eight migraines of any severity per month. But they also were told to use only a single dose of the medication in a 24-hour period (additional nontriptan rescue medication was permitted if necessary).

Overall, 23 patients were treated with the 5-mg dose, and 583 were treated with the 10-mg dose. The average age was about 13 years in the former group and 15 years in the latter group.

As far as migraine history, in the 3 months before the study, the patients had experienced on average four attacks monthly. The majority had migraines lasting more than 6 hours. Twelve percent were on preventive therapies. "For an adolescent trial, these are fairly disabling characteristics," Dr. Pearlman noted.

A total of 12,284 attacks (most either moderate or severe) were treated during the study. The mean number of doses of study medication taken by treated patients was 20.

The leading adverse event by far was accidental overdose (seen in 24% of patients overall), defined as taking more than one dose of rizatriptan in 24 hours. Possible reasons for these overdoses may have been previous experience with triptans for which two doses are allowed in this time period, and confusing a 24-hour day with a calendar day, Dr. Pearlman speculated. The next most common adverse events were dizziness (8%), somnolence (7%), and nausea (6%).

The rate of serious drug-related adverse events was 0% in the 5-mg group and 0.5% in the 10-mg group. "All three adverse events that were classified as serious occurred in the setting of an accidental overdose, and any adverse event that occurred in conjunction with an overdose per protocol was defined as serious," he explained.

In terms of efficacy, the rate of freedom from pain at 2 hours was 46% for all treated attacks, and it appeared to be consistent over time. In a post hoc analysis, the rate of pain relief at 2 hours was 65% for treated attacks. Rescue medications were used in only 6% of treated attacks.

Dr. Pearlman disclosed that he has received consulting fees from Merck, maker of Maxalt. The study was funded by Merck.

LOS ANGELES – Rizatriptan is safe and effective when used for intermittent treatment of migraine in adolescents on a long-term basis, according to a year-long, multicenter, open-label trial presented at the annual meeting of the American Headache Society.

Less than 1% of the 606 patients studied experienced serious drug-related adverse events. And all of these events were classified as serious because they occurred after accidental use of an extra dose of rizatriptan in a 24-hour period.

Additionally, in 46% of treated attacks, the patients were pain free at 2 hours after taking the medication, reported lead investigator Dr. Eric M. Pearlman of Children’s Hospital at Memorial University Medical Center, Savannah, Ga.

"Rizatriptan was generally safe and well tolerated in the long-term acute treatment of migraine in this adolescent population," he maintained. And "at least in an open-label fashion, it was effective."

Session attendee Dr. James R. Couch of the University of Oklahoma, Oklahoma City, commented, "That’s a very impressive pain-free number. ... The usual triptan gives us between 25% and 30% pain freedom. Do you have any comments on why children seem to respond much better?"

"I think it was because it was open label," Dr. Pearlman replied. "But this was done in conjunction with a single-attack, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial," he added. That trial, which led to regulatory approval of the drug for adolescents, had a run-in phase aimed at identifying and excluding placebo responders; the rate of pain freedom at 2 hours was 31% with rizatriptan.

Dr. Pearlman and his colleagues studied 12- to 17-years-olds in the United States and Europe who met diagnostic criteria for migraine and had not achieved a satisfactory response to treatment with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or acetaminophen.

They were assigned to the orally disintegrating tablet formulation of rizatriptan (Maxalt-MLT) based on weight: 5 mg if they weighed less than 40 kg, and 10 mg if they weighed 40 kg or more.

Patients were instructed to use the medication to treat up to eight migraines of any severity per month. But they also were told to use only a single dose of the medication in a 24-hour period (additional nontriptan rescue medication was permitted if necessary).

Overall, 23 patients were treated with the 5-mg dose, and 583 were treated with the 10-mg dose. The average age was about 13 years in the former group and 15 years in the latter group.

As far as migraine history, in the 3 months before the study, the patients had experienced on average four attacks monthly. The majority had migraines lasting more than 6 hours. Twelve percent were on preventive therapies. "For an adolescent trial, these are fairly disabling characteristics," Dr. Pearlman noted.

A total of 12,284 attacks (most either moderate or severe) were treated during the study. The mean number of doses of study medication taken by treated patients was 20.

The leading adverse event by far was accidental overdose (seen in 24% of patients overall), defined as taking more than one dose of rizatriptan in 24 hours. Possible reasons for these overdoses may have been previous experience with triptans for which two doses are allowed in this time period, and confusing a 24-hour day with a calendar day, Dr. Pearlman speculated. The next most common adverse events were dizziness (8%), somnolence (7%), and nausea (6%).

The rate of serious drug-related adverse events was 0% in the 5-mg group and 0.5% in the 10-mg group. "All three adverse events that were classified as serious occurred in the setting of an accidental overdose, and any adverse event that occurred in conjunction with an overdose per protocol was defined as serious," he explained.

In terms of efficacy, the rate of freedom from pain at 2 hours was 46% for all treated attacks, and it appeared to be consistent over time. In a post hoc analysis, the rate of pain relief at 2 hours was 65% for treated attacks. Rescue medications were used in only 6% of treated attacks.

Dr. Pearlman disclosed that he has received consulting fees from Merck, maker of Maxalt. The study was funded by Merck.

LOS ANGELES – Rizatriptan is safe and effective when used for intermittent treatment of migraine in adolescents on a long-term basis, according to a year-long, multicenter, open-label trial presented at the annual meeting of the American Headache Society.

Less than 1% of the 606 patients studied experienced serious drug-related adverse events. And all of these events were classified as serious because they occurred after accidental use of an extra dose of rizatriptan in a 24-hour period.

Additionally, in 46% of treated attacks, the patients were pain free at 2 hours after taking the medication, reported lead investigator Dr. Eric M. Pearlman of Children’s Hospital at Memorial University Medical Center, Savannah, Ga.

"Rizatriptan was generally safe and well tolerated in the long-term acute treatment of migraine in this adolescent population," he maintained. And "at least in an open-label fashion, it was effective."

Session attendee Dr. James R. Couch of the University of Oklahoma, Oklahoma City, commented, "That’s a very impressive pain-free number. ... The usual triptan gives us between 25% and 30% pain freedom. Do you have any comments on why children seem to respond much better?"

"I think it was because it was open label," Dr. Pearlman replied. "But this was done in conjunction with a single-attack, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial," he added. That trial, which led to regulatory approval of the drug for adolescents, had a run-in phase aimed at identifying and excluding placebo responders; the rate of pain freedom at 2 hours was 31% with rizatriptan.

Dr. Pearlman and his colleagues studied 12- to 17-years-olds in the United States and Europe who met diagnostic criteria for migraine and had not achieved a satisfactory response to treatment with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or acetaminophen.

They were assigned to the orally disintegrating tablet formulation of rizatriptan (Maxalt-MLT) based on weight: 5 mg if they weighed less than 40 kg, and 10 mg if they weighed 40 kg or more.

Patients were instructed to use the medication to treat up to eight migraines of any severity per month. But they also were told to use only a single dose of the medication in a 24-hour period (additional nontriptan rescue medication was permitted if necessary).

Overall, 23 patients were treated with the 5-mg dose, and 583 were treated with the 10-mg dose. The average age was about 13 years in the former group and 15 years in the latter group.

As far as migraine history, in the 3 months before the study, the patients had experienced on average four attacks monthly. The majority had migraines lasting more than 6 hours. Twelve percent were on preventive therapies. "For an adolescent trial, these are fairly disabling characteristics," Dr. Pearlman noted.

A total of 12,284 attacks (most either moderate or severe) were treated during the study. The mean number of doses of study medication taken by treated patients was 20.

The leading adverse event by far was accidental overdose (seen in 24% of patients overall), defined as taking more than one dose of rizatriptan in 24 hours. Possible reasons for these overdoses may have been previous experience with triptans for which two doses are allowed in this time period, and confusing a 24-hour day with a calendar day, Dr. Pearlman speculated. The next most common adverse events were dizziness (8%), somnolence (7%), and nausea (6%).

The rate of serious drug-related adverse events was 0% in the 5-mg group and 0.5% in the 10-mg group. "All three adverse events that were classified as serious occurred in the setting of an accidental overdose, and any adverse event that occurred in conjunction with an overdose per protocol was defined as serious," he explained.

In terms of efficacy, the rate of freedom from pain at 2 hours was 46% for all treated attacks, and it appeared to be consistent over time. In a post hoc analysis, the rate of pain relief at 2 hours was 65% for treated attacks. Rescue medications were used in only 6% of treated attacks.

Dr. Pearlman disclosed that he has received consulting fees from Merck, maker of Maxalt. The study was funded by Merck.

AT THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE AMERICAN HEADACHE SOCIETY

'Visual Snow' May Be a Distinct Clinical Entity

LOS ANGELES – So-called visual snow, characterized by myriad persistent tiny dots throughout the visual field, commonly occurs in patients with migraine, but it is usually accompanied by other visual symptoms and appears to be a distinct entity, according to combined data from two cross-sectional studies.

In a two-part study among 240 patients with visual snow, nearly all had other visual symptoms such as after-images or poor night vision, reported lead investigator Christoph Schankin, Ph.D., a postdoctoral clinical research fellow at the University of California at San Francisco Headache Center. Slightly more than half also had migraine, but the visual snow did not have any of the features of typical aura. Also, only a small minority of affected patients had used illicit drugs.

"Visual snow is almost always associated with additional visual symptoms. It therefore represents a unique clinical syndrome – the visual snow syndrome," he said at the annual meeting of the American Headache Society. "It is distinct from visual aura in migraine; migraine with and without aura are common comorbidities, but we don’t actually know at the moment what is the pathological link between those two conditions. And the intake of illicit drugs is not relevant."

Dr. Schankin went one step further, proposing new diagnostic criteria for the visual snow syndrome: visual snow plus at least three additional visual symptoms out of nine identified in the study, in the context where these symptoms are not consistent with typical migraine aura and cannot be attributed to some other disorder.

A session attendee congratulated the investigators on the research, noting, "These patients, for those who haven’t seen them, are devastated and lonely. Some can’t drive, some can’t work, some can’t read books, some can’t use computers. They are a wreck ... and there is nobody out there who is owning this condition – I don’t know if it falls in the realm of neuro-ophthalmology or neurology or headache, and what to do with these poor folks. ...They have been banished to the realms of psychiatry and have been told they have functional disorders and other things, when it is very clearly a widespread neurological perceptual disturbance."

He said his own experience with affected patients affirms the existence of the visual snow syndrome. "The more you talk to them, the more you appreciate that they really do have these features in common ... So I just want to thank you for bringing attention to this sort of orphan disorder, and hope it raises awareness, and that some people will take interest in it and studying the biophysiology and treatment options."

Session chair Dr. R. Allan Purdy, a neurologist at Dalhousie University in Halifax, N.S., asked the neuro-ophthalmologists present to weigh in with their thoughts on the possible pathophysiology of visual snow.

"I think this is a somewhat migrainous phenomenon in people with very sensitive brains," one replied. "We have done EEGs on these people and they are normal, at least in adults that we have seen with this. It is definitely real – these people are not making this up. And we have seen quite a few of these cases in neuro-ophthalmology."

Another concurred, saying "I think it’s real." Moreover, in her opinion, the presence of visual snow alone would be sufficient for diagnosis. "I suspect it’s migrainous because most of these people have migraines. But it’s not aura. I don’t know really what it is. It’s incredibly frustrating because nothing works. You can try every antiepileptic known to mankind, and nothing works. So I agree that this is something we need to pay attention to and help these people."

Dr. Schankin noted that research on visual snow is scarce, and affected individuals suffer in part because of a lack of knowledge about the condition in the medical community. "Patients are commonly given the diagnosis of persistent migraine aura or a posthallucinogen perceptual disorder, especially after LSD intake," he noted.

He and his coinvestigators studied members of an online support group for visual snow (Eye on Vision). In the first part of the study, they analyzed data from an Internet survey among 120 patients that asked about visual symptoms. They were 26 years old on average and about two-thirds were men.

Results showed that in addition to visual snow, nearly all patients reported other visual symptoms, such floaters (73%); persistent visual images (63%); difficulty seeing at night (58%); tiny objects moving on the blue sky (57%); sensitivity to light (54%); trails behind moving objects (48%); bright flashes (44%); and colored swirls, clouds, or waves when their eyes were closed (41%).

Dr. Schankin noted that some of these symptoms map onto the well defined clinical phenomena of palinopsia (trailing and prolonged after-images), photophobia, and impaired night vision.

And others fall into a category of entoptic phenomena, or visual symptoms originating in the eyes themselves, namely, floaters (likely protein aggregations in the vitreous fluid that cast a shadow on photoreceptors); photopsia (bright flashes typically elicited by mechanical stimulation of the eyes); Scheerer’s phenomenon (small moving objects against the sky thought to be due to blood cells moving in the retinal vessels that cast a shadow on the photoreceptors); and self-light of the eye (the colored swirls, clouds, and waves), whose etiology is unknown.

In the second part of the study, the investigators conducted telephone interviews with another 120 patients with visual snow to further explore the nature of symptoms and antecedent events. These patients were 31 years old on average and nearly evenly split between men and women.

Results showed that the textural patterns described for the snow varied considerably. The most common pattern reported was dots alternating from black (on light backgrounds) to white (on dark backgrounds) (48%), while some patients reported flashing dots, transparent dots, or other patterns. "We don’t know what that means – whether that has some pathophysiologic relevance," Dr. Schankin commented.

Analyses restricted to the subset reporting black and white dots showed that 98% had at least one additional visual symptom, and 93% had three or more. In this part of the study, another symptom identified was halos or starbursts, seen in 65% of cases.

Of the 40 patients with onset of visual snow later in life, 54% had a history of migraine. However, when asked about events in the week before the onset of visual snow, only 33% reported headache, and just 10% reported aura symptoms. But none had classic features of visual aura, such as unilaterality, zig-zag lines, or scotoma, during visual snow. Additionally, only 8% had used illicit drugs, mainly marijuana, in the week leading up to the start of visual snow, and none had significant ophthalmologic findings.

Dr. Schankin disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

LOS ANGELES – So-called visual snow, characterized by myriad persistent tiny dots throughout the visual field, commonly occurs in patients with migraine, but it is usually accompanied by other visual symptoms and appears to be a distinct entity, according to combined data from two cross-sectional studies.

In a two-part study among 240 patients with visual snow, nearly all had other visual symptoms such as after-images or poor night vision, reported lead investigator Christoph Schankin, Ph.D., a postdoctoral clinical research fellow at the University of California at San Francisco Headache Center. Slightly more than half also had migraine, but the visual snow did not have any of the features of typical aura. Also, only a small minority of affected patients had used illicit drugs.

"Visual snow is almost always associated with additional visual symptoms. It therefore represents a unique clinical syndrome – the visual snow syndrome," he said at the annual meeting of the American Headache Society. "It is distinct from visual aura in migraine; migraine with and without aura are common comorbidities, but we don’t actually know at the moment what is the pathological link between those two conditions. And the intake of illicit drugs is not relevant."

Dr. Schankin went one step further, proposing new diagnostic criteria for the visual snow syndrome: visual snow plus at least three additional visual symptoms out of nine identified in the study, in the context where these symptoms are not consistent with typical migraine aura and cannot be attributed to some other disorder.

A session attendee congratulated the investigators on the research, noting, "These patients, for those who haven’t seen them, are devastated and lonely. Some can’t drive, some can’t work, some can’t read books, some can’t use computers. They are a wreck ... and there is nobody out there who is owning this condition – I don’t know if it falls in the realm of neuro-ophthalmology or neurology or headache, and what to do with these poor folks. ...They have been banished to the realms of psychiatry and have been told they have functional disorders and other things, when it is very clearly a widespread neurological perceptual disturbance."

He said his own experience with affected patients affirms the existence of the visual snow syndrome. "The more you talk to them, the more you appreciate that they really do have these features in common ... So I just want to thank you for bringing attention to this sort of orphan disorder, and hope it raises awareness, and that some people will take interest in it and studying the biophysiology and treatment options."