User login

Aortomitral continuity calcification predicts new atrial fib after TAVR

PARIS – Aortomitral continuity calcification, a common finding on CT in patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement, predicts new-onset atrial fibrillation and the need for permanent pacemaker insertion, Marco Spaziano, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

“Increased surveillance for arrhythmias in the 30 days post TAVR is warranted in patients with aortomitral continuity calcification,” declared Dr. Spaziano of the Paris South Cardiovascular Institute in Massy, France.

He presented a single-center retrospective study of 524 patients undergoing TAVR with a self-expandable or balloon-expandable device. Aortomitral continuity calcification (AMCC) was found on CT in 15.8% of them. Dr. Spaziano defined AMCC as the presence of calcium in the curtain linking the aortic and mitral valve annuli. The clinical implications of this common finding were unknown prior to this study.

The 83 patients with AMCC did not differ significantly from the 441 without that CT finding in terms of baseline demographics, Society of Thoracic Surgeons risk score, prevalence of peripheral vascular disease, QRS duration, left ventricular ejection fraction, complete left or right bundle branch block, or aortic valve calcification volume. The prevalence of atrial fibrillation at baseline was 25.6% in the AMCC group and closely similar at 26.3% in the group without AMCC. Sixteen percent of subjects in each group had a previous pacemaker.

Similarly, the two groups didn’t differ in terms of procedural characteristics, including device type, size, or depth of implantation, or need for a second valve, or annular rupture.

However, excluding from consideration the patients with prior AF, the incidence of new AF in the 30 days post-TAVR was 22.7% in patients with AMCC compared with just 7.6% in the no-AMCC group. In addition, 33% of patients with AMCC received a new permanent pacemaker, as did 21% of those with no AMCC.

Other key 30-day outcomes didn’t differ between the two populations, including rates of death, stroke, vascular complications, and moderate or severe paravalvular regurgitation.

In a multivariate regression analysis adjusted for age, sex, device type and implantation depth, preexisting right bundle branch block, and surgical risk score, AMCC was associated with a statistically significant 1.8-fold increased likelihood of new pacemaker insertion and a 3.4-fold greater risk of new AF.

Dr. Spaziano said that in brainstorming with electrophysiology and echocardiography colleagues, the group came up with two hypotheses to explain the study findings. One is that AMCC might be a biologic marker for concomitant mitral stenosis, a known strong predictor of AF.

“Oftentimes it’s very difficult to diagnose mitral stenosis when there is aortic stenosis, because of left ventricular compliance issues, so potentially the patients with this calcium ridge may also have mitral stenosis,” he observed.

The other proposed hypothesis is that AMCC reflects increased calcification and fibrosis in the electrical system of both the AV node and atrium, with a resultant increased risk of developing new AF after the TAVR procedure.

Session chair Mohammad Abdelghani, MD, wasn’t buying either hypothesis. If either were correct, the group with AMCC would be expected to have a higher baseline rate of AF preprocedurally, observed Dr. Abdelghani of the Academic Medical Center at Amsterdam.

He suggested an alternative explanation on the basis of a German study that showed patients with significant calcification of the left coronary cusp were at sixfold greater risk for pacemaker implantation post TAVR. He proposed that calcification in the left sector of the valve landing zone causes the device to end up being positioned a bit off-line.

“I think the device protrudes away from the calcium and towards the right coronary artery commisure, compressing the conduction system that we know lies there,” Dr. Abdelghani said.

Dr. Spaziano reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his study.

PARIS – Aortomitral continuity calcification, a common finding on CT in patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement, predicts new-onset atrial fibrillation and the need for permanent pacemaker insertion, Marco Spaziano, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

“Increased surveillance for arrhythmias in the 30 days post TAVR is warranted in patients with aortomitral continuity calcification,” declared Dr. Spaziano of the Paris South Cardiovascular Institute in Massy, France.

He presented a single-center retrospective study of 524 patients undergoing TAVR with a self-expandable or balloon-expandable device. Aortomitral continuity calcification (AMCC) was found on CT in 15.8% of them. Dr. Spaziano defined AMCC as the presence of calcium in the curtain linking the aortic and mitral valve annuli. The clinical implications of this common finding were unknown prior to this study.

The 83 patients with AMCC did not differ significantly from the 441 without that CT finding in terms of baseline demographics, Society of Thoracic Surgeons risk score, prevalence of peripheral vascular disease, QRS duration, left ventricular ejection fraction, complete left or right bundle branch block, or aortic valve calcification volume. The prevalence of atrial fibrillation at baseline was 25.6% in the AMCC group and closely similar at 26.3% in the group without AMCC. Sixteen percent of subjects in each group had a previous pacemaker.

Similarly, the two groups didn’t differ in terms of procedural characteristics, including device type, size, or depth of implantation, or need for a second valve, or annular rupture.

However, excluding from consideration the patients with prior AF, the incidence of new AF in the 30 days post-TAVR was 22.7% in patients with AMCC compared with just 7.6% in the no-AMCC group. In addition, 33% of patients with AMCC received a new permanent pacemaker, as did 21% of those with no AMCC.

Other key 30-day outcomes didn’t differ between the two populations, including rates of death, stroke, vascular complications, and moderate or severe paravalvular regurgitation.

In a multivariate regression analysis adjusted for age, sex, device type and implantation depth, preexisting right bundle branch block, and surgical risk score, AMCC was associated with a statistically significant 1.8-fold increased likelihood of new pacemaker insertion and a 3.4-fold greater risk of new AF.

Dr. Spaziano said that in brainstorming with electrophysiology and echocardiography colleagues, the group came up with two hypotheses to explain the study findings. One is that AMCC might be a biologic marker for concomitant mitral stenosis, a known strong predictor of AF.

“Oftentimes it’s very difficult to diagnose mitral stenosis when there is aortic stenosis, because of left ventricular compliance issues, so potentially the patients with this calcium ridge may also have mitral stenosis,” he observed.

The other proposed hypothesis is that AMCC reflects increased calcification and fibrosis in the electrical system of both the AV node and atrium, with a resultant increased risk of developing new AF after the TAVR procedure.

Session chair Mohammad Abdelghani, MD, wasn’t buying either hypothesis. If either were correct, the group with AMCC would be expected to have a higher baseline rate of AF preprocedurally, observed Dr. Abdelghani of the Academic Medical Center at Amsterdam.

He suggested an alternative explanation on the basis of a German study that showed patients with significant calcification of the left coronary cusp were at sixfold greater risk for pacemaker implantation post TAVR. He proposed that calcification in the left sector of the valve landing zone causes the device to end up being positioned a bit off-line.

“I think the device protrudes away from the calcium and towards the right coronary artery commisure, compressing the conduction system that we know lies there,” Dr. Abdelghani said.

Dr. Spaziano reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his study.

PARIS – Aortomitral continuity calcification, a common finding on CT in patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement, predicts new-onset atrial fibrillation and the need for permanent pacemaker insertion, Marco Spaziano, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

“Increased surveillance for arrhythmias in the 30 days post TAVR is warranted in patients with aortomitral continuity calcification,” declared Dr. Spaziano of the Paris South Cardiovascular Institute in Massy, France.

He presented a single-center retrospective study of 524 patients undergoing TAVR with a self-expandable or balloon-expandable device. Aortomitral continuity calcification (AMCC) was found on CT in 15.8% of them. Dr. Spaziano defined AMCC as the presence of calcium in the curtain linking the aortic and mitral valve annuli. The clinical implications of this common finding were unknown prior to this study.

The 83 patients with AMCC did not differ significantly from the 441 without that CT finding in terms of baseline demographics, Society of Thoracic Surgeons risk score, prevalence of peripheral vascular disease, QRS duration, left ventricular ejection fraction, complete left or right bundle branch block, or aortic valve calcification volume. The prevalence of atrial fibrillation at baseline was 25.6% in the AMCC group and closely similar at 26.3% in the group without AMCC. Sixteen percent of subjects in each group had a previous pacemaker.

Similarly, the two groups didn’t differ in terms of procedural characteristics, including device type, size, or depth of implantation, or need for a second valve, or annular rupture.

However, excluding from consideration the patients with prior AF, the incidence of new AF in the 30 days post-TAVR was 22.7% in patients with AMCC compared with just 7.6% in the no-AMCC group. In addition, 33% of patients with AMCC received a new permanent pacemaker, as did 21% of those with no AMCC.

Other key 30-day outcomes didn’t differ between the two populations, including rates of death, stroke, vascular complications, and moderate or severe paravalvular regurgitation.

In a multivariate regression analysis adjusted for age, sex, device type and implantation depth, preexisting right bundle branch block, and surgical risk score, AMCC was associated with a statistically significant 1.8-fold increased likelihood of new pacemaker insertion and a 3.4-fold greater risk of new AF.

Dr. Spaziano said that in brainstorming with electrophysiology and echocardiography colleagues, the group came up with two hypotheses to explain the study findings. One is that AMCC might be a biologic marker for concomitant mitral stenosis, a known strong predictor of AF.

“Oftentimes it’s very difficult to diagnose mitral stenosis when there is aortic stenosis, because of left ventricular compliance issues, so potentially the patients with this calcium ridge may also have mitral stenosis,” he observed.

The other proposed hypothesis is that AMCC reflects increased calcification and fibrosis in the electrical system of both the AV node and atrium, with a resultant increased risk of developing new AF after the TAVR procedure.

Session chair Mohammad Abdelghani, MD, wasn’t buying either hypothesis. If either were correct, the group with AMCC would be expected to have a higher baseline rate of AF preprocedurally, observed Dr. Abdelghani of the Academic Medical Center at Amsterdam.

He suggested an alternative explanation on the basis of a German study that showed patients with significant calcification of the left coronary cusp were at sixfold greater risk for pacemaker implantation post TAVR. He proposed that calcification in the left sector of the valve landing zone causes the device to end up being positioned a bit off-line.

“I think the device protrudes away from the calcium and towards the right coronary artery commisure, compressing the conduction system that we know lies there,” Dr. Abdelghani said.

Dr. Spaziano reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his study.

AT europcr 2016

Key clinical point: Aortomitral continuity calcification is associated with a markedly increased risk of new atrial fibrillation in patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement.

Major finding: The CT finding of aortomitral continuity calcification in patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement was associated with a 3.4-fold increased likelihood of new atrial fibrillation arising during the first 30 days post procedure.

Data source: A retrospective single-center study in 524 patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement, nearly 16% of whom were found to have aortomitral continuity calcification.

Disclosures: The presenter reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his study.

Same-day discharge after PCI gets a boost

PARIS – Same-day discharge after uncomplicated transradial-access percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in patients with stable coronary artery disease is both feasible and safe, according to the findings of a multicenter prospective Spanish registry study.

Under the Spanish investigators’ protocol for same-day discharge, roughly three-quarters of patients successfully completed the 4- to 12-hour post-PCI surveillance period and were expeditiously sent home without spending a night in the hospital, Juan Gabriel Cordoba Soriano, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

The other 26% of patients were admitted, most often because they showed clinical instability during the surveillance period, less frequently due to a suboptimal angiographic result, explained Dr. Cordoba Soriano of the University of Albacete, Spain.

The rationale for same-day discharge post PCI – provided it has first been shown to be safe, as was the case using the Spanish criteria – is that it reduces costs by avoiding an expensive hospital bed. Also, most patients prefer to sleep in their own bed and avoid a hospital stay, he continued.

Eligibility for same-day discharge in the Spanish study was restricted to patients with stable coronary artery disease undergoing elective transradial PCI with no complications during the procedure and with clinical stability during the subsequent 4- to 12-hour observation period. Patients undergoing complex PCIs – for example, treatment of left main lesions, complex bifurcation lesions, or chronic total occlusions – were ineligible.

Why restrict eligibility to patients undergoing transradial PCI? Multiple studies convincingly show it is safer than femoral access. And outside of the United States, it is by far the more popular access route. In a show of hands, virtually all of Dr. Cordoba Soriano’s audience indicated they perform more than 70% of their PCIs via transradial access. And patients with stable CAD are less likely to experience stent thrombosis or acute occlusion of the treated artery or side branches, he continued.

Of 989 patients who presented to the three participating Spanish medical centers for elective PCI, 257 were immediately excluded from the registry because they underwent elective femoral access. That left 732 patients, 74% of whom got same-day discharge.

The same-day discharge and hospital admission groups were closely similar in terms of baseline characteristics with two exceptions: The prevalence of peripheral arterial disease in the same-day discharge group was less than half of the 10% figure in the hospitalized group, and kidney function was better in patients who ultimately received same-day discharge as evidenced by a serum creatinine of 0.9 mg/dL, half that of the hospitalized patients.

Procedural characteristics were mostly similar for the two groups as well. Although the same-day discharge group had a 26-minute shorter median procedure time, were less likely to undergo multivessel PCI, and had fewer stents implanted per patient, in a multivariate regression analysis the only independent predictors of admission post PCI were the presence of peripheral arterial disease, with an associated 2.2-fold increased risk; multivessel PCI, with a 1.8-fold risk; ad hoc as opposed to a scheduled PCI, with a 4.0-fold increased risk; and a history of prior transradial catheterization, which cut the risk of hospitalization in half.

Turning to the safety of same-day discharge, the cardiologist deemed the rate of major complications in the first 24 hours to be acceptable at 0.18% for a single case of significant bleeding. Minor complications were confined to a 1.8% incidence of hematomas greater than 5 cm in size.

The major complication rate from 24 hours to 30 days post PCI was 0.54% (two deaths, one stroke), with a 2.2% incidence of minor complications.

Dr. Cordoba Soriano noted that investigators at the Quebec Heart and Lung Institute have published a meta-analysis of 13 studies of same-day discharge after PCI totaling more than 111,000 patients (JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2013 Feb;6[2]:99-112). The investigators concluded that a definitive randomized trial would require more than 17,000 subjects, and in the absence of such evidence same-day discharge after uncomplicated PCI “seems a reasonable approach in selected patients.”

Stanford University investigators have published a separate meta-analysis of same-day discharge after PCI in nearly 13,000 patients in 30 observational and 7 randomized controlled trials. They concluded that it appears to be as safe as overnight observation (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013 Jul 23;62[4]:275-85).

Nevertheless, the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions has yet to update its 2009 expert consensus document stating that the standard of care is an overnight stay following PCI (Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2009 Jun 1;73[7]:847-58), Dr. Cordoba Soriano observed.

He reported having no financial conflicts regarding the registry study, which was conducted with university research funds.

PARIS – Same-day discharge after uncomplicated transradial-access percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in patients with stable coronary artery disease is both feasible and safe, according to the findings of a multicenter prospective Spanish registry study.

Under the Spanish investigators’ protocol for same-day discharge, roughly three-quarters of patients successfully completed the 4- to 12-hour post-PCI surveillance period and were expeditiously sent home without spending a night in the hospital, Juan Gabriel Cordoba Soriano, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

The other 26% of patients were admitted, most often because they showed clinical instability during the surveillance period, less frequently due to a suboptimal angiographic result, explained Dr. Cordoba Soriano of the University of Albacete, Spain.

The rationale for same-day discharge post PCI – provided it has first been shown to be safe, as was the case using the Spanish criteria – is that it reduces costs by avoiding an expensive hospital bed. Also, most patients prefer to sleep in their own bed and avoid a hospital stay, he continued.

Eligibility for same-day discharge in the Spanish study was restricted to patients with stable coronary artery disease undergoing elective transradial PCI with no complications during the procedure and with clinical stability during the subsequent 4- to 12-hour observation period. Patients undergoing complex PCIs – for example, treatment of left main lesions, complex bifurcation lesions, or chronic total occlusions – were ineligible.

Why restrict eligibility to patients undergoing transradial PCI? Multiple studies convincingly show it is safer than femoral access. And outside of the United States, it is by far the more popular access route. In a show of hands, virtually all of Dr. Cordoba Soriano’s audience indicated they perform more than 70% of their PCIs via transradial access. And patients with stable CAD are less likely to experience stent thrombosis or acute occlusion of the treated artery or side branches, he continued.

Of 989 patients who presented to the three participating Spanish medical centers for elective PCI, 257 were immediately excluded from the registry because they underwent elective femoral access. That left 732 patients, 74% of whom got same-day discharge.

The same-day discharge and hospital admission groups were closely similar in terms of baseline characteristics with two exceptions: The prevalence of peripheral arterial disease in the same-day discharge group was less than half of the 10% figure in the hospitalized group, and kidney function was better in patients who ultimately received same-day discharge as evidenced by a serum creatinine of 0.9 mg/dL, half that of the hospitalized patients.

Procedural characteristics were mostly similar for the two groups as well. Although the same-day discharge group had a 26-minute shorter median procedure time, were less likely to undergo multivessel PCI, and had fewer stents implanted per patient, in a multivariate regression analysis the only independent predictors of admission post PCI were the presence of peripheral arterial disease, with an associated 2.2-fold increased risk; multivessel PCI, with a 1.8-fold risk; ad hoc as opposed to a scheduled PCI, with a 4.0-fold increased risk; and a history of prior transradial catheterization, which cut the risk of hospitalization in half.

Turning to the safety of same-day discharge, the cardiologist deemed the rate of major complications in the first 24 hours to be acceptable at 0.18% for a single case of significant bleeding. Minor complications were confined to a 1.8% incidence of hematomas greater than 5 cm in size.

The major complication rate from 24 hours to 30 days post PCI was 0.54% (two deaths, one stroke), with a 2.2% incidence of minor complications.

Dr. Cordoba Soriano noted that investigators at the Quebec Heart and Lung Institute have published a meta-analysis of 13 studies of same-day discharge after PCI totaling more than 111,000 patients (JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2013 Feb;6[2]:99-112). The investigators concluded that a definitive randomized trial would require more than 17,000 subjects, and in the absence of such evidence same-day discharge after uncomplicated PCI “seems a reasonable approach in selected patients.”

Stanford University investigators have published a separate meta-analysis of same-day discharge after PCI in nearly 13,000 patients in 30 observational and 7 randomized controlled trials. They concluded that it appears to be as safe as overnight observation (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013 Jul 23;62[4]:275-85).

Nevertheless, the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions has yet to update its 2009 expert consensus document stating that the standard of care is an overnight stay following PCI (Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2009 Jun 1;73[7]:847-58), Dr. Cordoba Soriano observed.

He reported having no financial conflicts regarding the registry study, which was conducted with university research funds.

PARIS – Same-day discharge after uncomplicated transradial-access percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in patients with stable coronary artery disease is both feasible and safe, according to the findings of a multicenter prospective Spanish registry study.

Under the Spanish investigators’ protocol for same-day discharge, roughly three-quarters of patients successfully completed the 4- to 12-hour post-PCI surveillance period and were expeditiously sent home without spending a night in the hospital, Juan Gabriel Cordoba Soriano, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

The other 26% of patients were admitted, most often because they showed clinical instability during the surveillance period, less frequently due to a suboptimal angiographic result, explained Dr. Cordoba Soriano of the University of Albacete, Spain.

The rationale for same-day discharge post PCI – provided it has first been shown to be safe, as was the case using the Spanish criteria – is that it reduces costs by avoiding an expensive hospital bed. Also, most patients prefer to sleep in their own bed and avoid a hospital stay, he continued.

Eligibility for same-day discharge in the Spanish study was restricted to patients with stable coronary artery disease undergoing elective transradial PCI with no complications during the procedure and with clinical stability during the subsequent 4- to 12-hour observation period. Patients undergoing complex PCIs – for example, treatment of left main lesions, complex bifurcation lesions, or chronic total occlusions – were ineligible.

Why restrict eligibility to patients undergoing transradial PCI? Multiple studies convincingly show it is safer than femoral access. And outside of the United States, it is by far the more popular access route. In a show of hands, virtually all of Dr. Cordoba Soriano’s audience indicated they perform more than 70% of their PCIs via transradial access. And patients with stable CAD are less likely to experience stent thrombosis or acute occlusion of the treated artery or side branches, he continued.

Of 989 patients who presented to the three participating Spanish medical centers for elective PCI, 257 were immediately excluded from the registry because they underwent elective femoral access. That left 732 patients, 74% of whom got same-day discharge.

The same-day discharge and hospital admission groups were closely similar in terms of baseline characteristics with two exceptions: The prevalence of peripheral arterial disease in the same-day discharge group was less than half of the 10% figure in the hospitalized group, and kidney function was better in patients who ultimately received same-day discharge as evidenced by a serum creatinine of 0.9 mg/dL, half that of the hospitalized patients.

Procedural characteristics were mostly similar for the two groups as well. Although the same-day discharge group had a 26-minute shorter median procedure time, were less likely to undergo multivessel PCI, and had fewer stents implanted per patient, in a multivariate regression analysis the only independent predictors of admission post PCI were the presence of peripheral arterial disease, with an associated 2.2-fold increased risk; multivessel PCI, with a 1.8-fold risk; ad hoc as opposed to a scheduled PCI, with a 4.0-fold increased risk; and a history of prior transradial catheterization, which cut the risk of hospitalization in half.

Turning to the safety of same-day discharge, the cardiologist deemed the rate of major complications in the first 24 hours to be acceptable at 0.18% for a single case of significant bleeding. Minor complications were confined to a 1.8% incidence of hematomas greater than 5 cm in size.

The major complication rate from 24 hours to 30 days post PCI was 0.54% (two deaths, one stroke), with a 2.2% incidence of minor complications.

Dr. Cordoba Soriano noted that investigators at the Quebec Heart and Lung Institute have published a meta-analysis of 13 studies of same-day discharge after PCI totaling more than 111,000 patients (JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2013 Feb;6[2]:99-112). The investigators concluded that a definitive randomized trial would require more than 17,000 subjects, and in the absence of such evidence same-day discharge after uncomplicated PCI “seems a reasonable approach in selected patients.”

Stanford University investigators have published a separate meta-analysis of same-day discharge after PCI in nearly 13,000 patients in 30 observational and 7 randomized controlled trials. They concluded that it appears to be as safe as overnight observation (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013 Jul 23;62[4]:275-85).

Nevertheless, the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions has yet to update its 2009 expert consensus document stating that the standard of care is an overnight stay following PCI (Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2009 Jun 1;73[7]:847-58), Dr. Cordoba Soriano observed.

He reported having no financial conflicts regarding the registry study, which was conducted with university research funds.

AT EUROPCR 2016

Key clinical point: Same-day discharge following uncomplicated elective transradial PCI is feasible and safe.

Major finding: The rates of major and minor complications in the 24 hours following PCI with same-day discharge were 0.18% and 1.8%, respectively.

Data source: A prospective observational registry study including 989 PCI patients at three Spanish university hospitals.

Disclosures: The presenter reported having no financial conflicts regarding the registry study, which was conducted with university research funds.

Using transcatheter aortic valves for severe mitral annular calcification

PARIS – Transcatheter mitral valve replacement using a repurposed transcatheter aortic valve in patients with severe symptomatic native mitral valve disease and severe mitral annular calcification is feasible and may be an option in carefully selected patients who aren’t candidates for surgery, Mayra Guerrero, MD, said at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

However, at this early point in development, the procedure is associated with an exceptionally steep learning curve, said Dr. Guerrero, director of cardiac structural interventions at the NorthShore University Health System in Evanston, Ill.

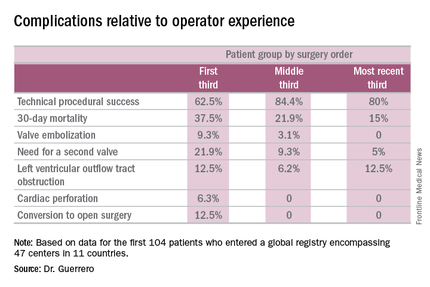

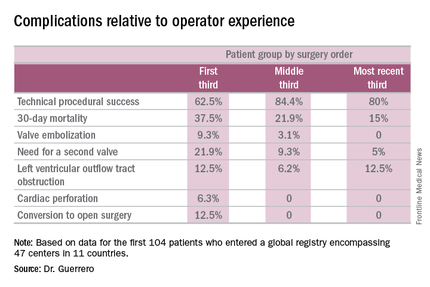

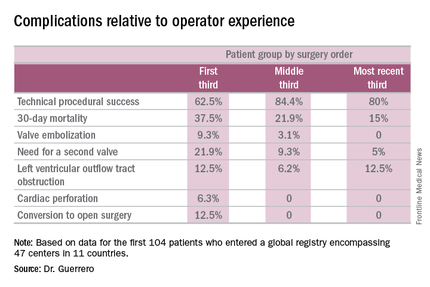

She presented the procedural and 30-day outcomes for the first 104 patients entered into a global registry encompassing 47 centers in 11 countries. Nearly 90% of patients received an Edwards SAPIEN XT or SAPIEN 3 valve. The EuroPCR results update an earlier report on the first 64 patients in the registry (JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2016 Jul 11;9[13]:1361-71).

The results, she said, are reminiscent of the early days in transcatheter aortic valve replacement, which were marked by an initial very high early mortality rate that fell dramatically as technology and techniques improved.

“We know that there are important things we need to improve. Left ventricular outflow tract obstruction is the Achilles heel of this procedure; we need to work on its prevention and management. We need better annulus sizing methods. We need to find the best delivery method and improve our patient selection in order to avoid taking on patients who are too sick. Still, even during this early experience, the technical success rate has improved, and 30-day mortality continues to drop,” Dr. Guerrero said.

Indeed, the 30-day all-cause mortality rate of 25% in the first 104 patients doesn’t tell the whole story. The rate was 37.5% in the first third of patients, fell to 21.9% in the second tertile, and then to 15% in the most recent tertile.

Similarly, the technical success rate of the procedure according to Mitral Valve Academic Research Consortium criteria improved from 62.5% in the first tertile of patients to 84.4% and 80% in the second and third, respectively, she continued.

The rates of almost all complications went down with greater operator experience, too. The notable exception was left ventricular outflow tract obstruction (LVOTO). It occurred in 12.5% of patients in the first tertile and remained unchanged in the third.

It’s noteworthy that the majority of deaths were noncardiac in nature. Patients with mitral annular calcification are a high-risk group even before they develop valvular dysfunction. They are typically older and have multiple comorbidities. Participants in the global registry had a mean Society of Thoracic Surgeons score of 14.4; 38% had diabetes, 45% had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, 35% had heart failure, 34% had previously undergone coronary artery bypass surgery, and roughly half of patients had a prior aortic valve replacement.

Causes of noncardiac mortality within 30 days included multiorgan failure in 8.6% of subjects, pneumonia in 2.9%, infection in 1.9%, and one fatal thoracentesis-related bleeding complication.

Cardiovascular deaths included two cases due to left ventricular perforation, two fatal strokes, an MI due to air emboli, a lethal complete atrioventricular block, and three deaths owing to LVOTO.

Alcohol ablation met with some success as a bailout treatment in cases of LVOTO with hemodynamic compromise after transmitral valve replacement in the global registry. All six treated patients had significant improvement initially, although the LVOTO recurred the next day in one instance. Four of the six patients were discharged from the hospital. One patient died because of atrioventricular block, and another from multiorgan failure 3 weeks after alcohol ablation of the LVOTO.

Dr. Guerrero has been a leader in this new field. She reported the first percutaneous implantation of a balloon expandable transcatheter valve in a native mitral valve without a surgical incision (Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2014 Jun 1;83[7]:E287-91), and more recently, together with coworkers developed a percutaneous alcohol ablation technique for acute reduction of LVOTO due to transcatheter mitral valve replacement (Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2016 Jul 5. doi:10.1002/ccd.26649).

She is now the principal investigator in the ongoing Mitral Implantation of Transcatheter Valves (MITRAL) trial, a physician-sponsored, 90-patient pilot study underway at six U.S. sites. MITRAL is recruiting three patient populations for transcatheter mitral valve replacement: patients like those in the global registry, with native mitral valve disease and severe mitral annular calcification; those with a symptomatic failing surgical ring with severe mitral regurgitation or stenosis; and patients with a symptomatic failing surgical bioprosthesis with severe mitral regurgitation or stenosis.

Discussant Nicolo Piazza, MD, of McGill University, Montreal, said transcatheter mitral valve replacement in mitral valve disease with severe mitral annular calcification in patients unsuitable for surgery “definitely represents an unmet clinical need in our practice today.” But he urged caution in interpreting the global registry data.

“This is a real world registry study with inherent selection bias and physician reporting bias,” the cardiologist said.

“We are leveraging a therapy from the aortic field into the mitral field. Of course, we do not have dedicated devices yet to treat these patients. The main finding of this study is that the procedure is actually feasible,” Dr. Piazza said.

Still, it’s sobering that at least 1 in 10 treated patients experiences LVOTO, 1 in 10 requires a second valve, and technical success is achieved in 3 out of 4 patients, he added.

Dr. Piazza predicted that multislice CT scans will be “extremely important” in refining patient selection criteria for the procedure, and echocardiography will be helpful in understanding the optimal procedural techniques and viewing angles. Work also needs to be done on developing optimal anticoagulation protocols in order to avoid valve thrombosis.

Dr. Guerrero reported serving as a consultant to Edwards Lifesciences. Dr. Piazza is a consultant to Medtronic and MicroPort.

PARIS – Transcatheter mitral valve replacement using a repurposed transcatheter aortic valve in patients with severe symptomatic native mitral valve disease and severe mitral annular calcification is feasible and may be an option in carefully selected patients who aren’t candidates for surgery, Mayra Guerrero, MD, said at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

However, at this early point in development, the procedure is associated with an exceptionally steep learning curve, said Dr. Guerrero, director of cardiac structural interventions at the NorthShore University Health System in Evanston, Ill.

She presented the procedural and 30-day outcomes for the first 104 patients entered into a global registry encompassing 47 centers in 11 countries. Nearly 90% of patients received an Edwards SAPIEN XT or SAPIEN 3 valve. The EuroPCR results update an earlier report on the first 64 patients in the registry (JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2016 Jul 11;9[13]:1361-71).

The results, she said, are reminiscent of the early days in transcatheter aortic valve replacement, which were marked by an initial very high early mortality rate that fell dramatically as technology and techniques improved.

“We know that there are important things we need to improve. Left ventricular outflow tract obstruction is the Achilles heel of this procedure; we need to work on its prevention and management. We need better annulus sizing methods. We need to find the best delivery method and improve our patient selection in order to avoid taking on patients who are too sick. Still, even during this early experience, the technical success rate has improved, and 30-day mortality continues to drop,” Dr. Guerrero said.

Indeed, the 30-day all-cause mortality rate of 25% in the first 104 patients doesn’t tell the whole story. The rate was 37.5% in the first third of patients, fell to 21.9% in the second tertile, and then to 15% in the most recent tertile.

Similarly, the technical success rate of the procedure according to Mitral Valve Academic Research Consortium criteria improved from 62.5% in the first tertile of patients to 84.4% and 80% in the second and third, respectively, she continued.

The rates of almost all complications went down with greater operator experience, too. The notable exception was left ventricular outflow tract obstruction (LVOTO). It occurred in 12.5% of patients in the first tertile and remained unchanged in the third.

It’s noteworthy that the majority of deaths were noncardiac in nature. Patients with mitral annular calcification are a high-risk group even before they develop valvular dysfunction. They are typically older and have multiple comorbidities. Participants in the global registry had a mean Society of Thoracic Surgeons score of 14.4; 38% had diabetes, 45% had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, 35% had heart failure, 34% had previously undergone coronary artery bypass surgery, and roughly half of patients had a prior aortic valve replacement.

Causes of noncardiac mortality within 30 days included multiorgan failure in 8.6% of subjects, pneumonia in 2.9%, infection in 1.9%, and one fatal thoracentesis-related bleeding complication.

Cardiovascular deaths included two cases due to left ventricular perforation, two fatal strokes, an MI due to air emboli, a lethal complete atrioventricular block, and three deaths owing to LVOTO.

Alcohol ablation met with some success as a bailout treatment in cases of LVOTO with hemodynamic compromise after transmitral valve replacement in the global registry. All six treated patients had significant improvement initially, although the LVOTO recurred the next day in one instance. Four of the six patients were discharged from the hospital. One patient died because of atrioventricular block, and another from multiorgan failure 3 weeks after alcohol ablation of the LVOTO.

Dr. Guerrero has been a leader in this new field. She reported the first percutaneous implantation of a balloon expandable transcatheter valve in a native mitral valve without a surgical incision (Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2014 Jun 1;83[7]:E287-91), and more recently, together with coworkers developed a percutaneous alcohol ablation technique for acute reduction of LVOTO due to transcatheter mitral valve replacement (Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2016 Jul 5. doi:10.1002/ccd.26649).

She is now the principal investigator in the ongoing Mitral Implantation of Transcatheter Valves (MITRAL) trial, a physician-sponsored, 90-patient pilot study underway at six U.S. sites. MITRAL is recruiting three patient populations for transcatheter mitral valve replacement: patients like those in the global registry, with native mitral valve disease and severe mitral annular calcification; those with a symptomatic failing surgical ring with severe mitral regurgitation or stenosis; and patients with a symptomatic failing surgical bioprosthesis with severe mitral regurgitation or stenosis.

Discussant Nicolo Piazza, MD, of McGill University, Montreal, said transcatheter mitral valve replacement in mitral valve disease with severe mitral annular calcification in patients unsuitable for surgery “definitely represents an unmet clinical need in our practice today.” But he urged caution in interpreting the global registry data.

“This is a real world registry study with inherent selection bias and physician reporting bias,” the cardiologist said.

“We are leveraging a therapy from the aortic field into the mitral field. Of course, we do not have dedicated devices yet to treat these patients. The main finding of this study is that the procedure is actually feasible,” Dr. Piazza said.

Still, it’s sobering that at least 1 in 10 treated patients experiences LVOTO, 1 in 10 requires a second valve, and technical success is achieved in 3 out of 4 patients, he added.

Dr. Piazza predicted that multislice CT scans will be “extremely important” in refining patient selection criteria for the procedure, and echocardiography will be helpful in understanding the optimal procedural techniques and viewing angles. Work also needs to be done on developing optimal anticoagulation protocols in order to avoid valve thrombosis.

Dr. Guerrero reported serving as a consultant to Edwards Lifesciences. Dr. Piazza is a consultant to Medtronic and MicroPort.

PARIS – Transcatheter mitral valve replacement using a repurposed transcatheter aortic valve in patients with severe symptomatic native mitral valve disease and severe mitral annular calcification is feasible and may be an option in carefully selected patients who aren’t candidates for surgery, Mayra Guerrero, MD, said at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

However, at this early point in development, the procedure is associated with an exceptionally steep learning curve, said Dr. Guerrero, director of cardiac structural interventions at the NorthShore University Health System in Evanston, Ill.

She presented the procedural and 30-day outcomes for the first 104 patients entered into a global registry encompassing 47 centers in 11 countries. Nearly 90% of patients received an Edwards SAPIEN XT or SAPIEN 3 valve. The EuroPCR results update an earlier report on the first 64 patients in the registry (JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2016 Jul 11;9[13]:1361-71).

The results, she said, are reminiscent of the early days in transcatheter aortic valve replacement, which were marked by an initial very high early mortality rate that fell dramatically as technology and techniques improved.

“We know that there are important things we need to improve. Left ventricular outflow tract obstruction is the Achilles heel of this procedure; we need to work on its prevention and management. We need better annulus sizing methods. We need to find the best delivery method and improve our patient selection in order to avoid taking on patients who are too sick. Still, even during this early experience, the technical success rate has improved, and 30-day mortality continues to drop,” Dr. Guerrero said.

Indeed, the 30-day all-cause mortality rate of 25% in the first 104 patients doesn’t tell the whole story. The rate was 37.5% in the first third of patients, fell to 21.9% in the second tertile, and then to 15% in the most recent tertile.

Similarly, the technical success rate of the procedure according to Mitral Valve Academic Research Consortium criteria improved from 62.5% in the first tertile of patients to 84.4% and 80% in the second and third, respectively, she continued.

The rates of almost all complications went down with greater operator experience, too. The notable exception was left ventricular outflow tract obstruction (LVOTO). It occurred in 12.5% of patients in the first tertile and remained unchanged in the third.

It’s noteworthy that the majority of deaths were noncardiac in nature. Patients with mitral annular calcification are a high-risk group even before they develop valvular dysfunction. They are typically older and have multiple comorbidities. Participants in the global registry had a mean Society of Thoracic Surgeons score of 14.4; 38% had diabetes, 45% had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, 35% had heart failure, 34% had previously undergone coronary artery bypass surgery, and roughly half of patients had a prior aortic valve replacement.

Causes of noncardiac mortality within 30 days included multiorgan failure in 8.6% of subjects, pneumonia in 2.9%, infection in 1.9%, and one fatal thoracentesis-related bleeding complication.

Cardiovascular deaths included two cases due to left ventricular perforation, two fatal strokes, an MI due to air emboli, a lethal complete atrioventricular block, and three deaths owing to LVOTO.

Alcohol ablation met with some success as a bailout treatment in cases of LVOTO with hemodynamic compromise after transmitral valve replacement in the global registry. All six treated patients had significant improvement initially, although the LVOTO recurred the next day in one instance. Four of the six patients were discharged from the hospital. One patient died because of atrioventricular block, and another from multiorgan failure 3 weeks after alcohol ablation of the LVOTO.

Dr. Guerrero has been a leader in this new field. She reported the first percutaneous implantation of a balloon expandable transcatheter valve in a native mitral valve without a surgical incision (Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2014 Jun 1;83[7]:E287-91), and more recently, together with coworkers developed a percutaneous alcohol ablation technique for acute reduction of LVOTO due to transcatheter mitral valve replacement (Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2016 Jul 5. doi:10.1002/ccd.26649).

She is now the principal investigator in the ongoing Mitral Implantation of Transcatheter Valves (MITRAL) trial, a physician-sponsored, 90-patient pilot study underway at six U.S. sites. MITRAL is recruiting three patient populations for transcatheter mitral valve replacement: patients like those in the global registry, with native mitral valve disease and severe mitral annular calcification; those with a symptomatic failing surgical ring with severe mitral regurgitation or stenosis; and patients with a symptomatic failing surgical bioprosthesis with severe mitral regurgitation or stenosis.

Discussant Nicolo Piazza, MD, of McGill University, Montreal, said transcatheter mitral valve replacement in mitral valve disease with severe mitral annular calcification in patients unsuitable for surgery “definitely represents an unmet clinical need in our practice today.” But he urged caution in interpreting the global registry data.

“This is a real world registry study with inherent selection bias and physician reporting bias,” the cardiologist said.

“We are leveraging a therapy from the aortic field into the mitral field. Of course, we do not have dedicated devices yet to treat these patients. The main finding of this study is that the procedure is actually feasible,” Dr. Piazza said.

Still, it’s sobering that at least 1 in 10 treated patients experiences LVOTO, 1 in 10 requires a second valve, and technical success is achieved in 3 out of 4 patients, he added.

Dr. Piazza predicted that multislice CT scans will be “extremely important” in refining patient selection criteria for the procedure, and echocardiography will be helpful in understanding the optimal procedural techniques and viewing angles. Work also needs to be done on developing optimal anticoagulation protocols in order to avoid valve thrombosis.

Dr. Guerrero reported serving as a consultant to Edwards Lifesciences. Dr. Piazza is a consultant to Medtronic and MicroPort.

AT EUROPCR 2016

Key clinical point: A report from a global registry of transcatheter aortic valve implantation in the mitral position shows the procedure is feasible.

Major finding: Thirty-day mortality fell from 37.5% in the first third of treated patients to 15% in the most recent tertile.

Data source: A real world registry that includes 104 patients at 47 centers in 11 countries to date.

Disclosures: The study presenter reported serving as a consultant to Edwards Lifesciences.

Bioabsorbable percutaneous device fully closes large femoral arteriotomies

PARIS – A new bioabsorbable sutureless device provides operators with a safe, simple, and dependable option for fully percutaneous closure of the large, 12-24 French femoral arteriotomies created for transcatheter aortic valve replacement or endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair, Arne Schwindt, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

He presented the 12-month follow-up results of the FRONTIER II study of the Vivasure PerQseal device. The device recently received European marketing approval on the strength of FRONTIER II but remains investigational in the United States.

The PerQseal device is deployed in less than 1 minute at the end of the primary procedure and achieves immediate hemostasis. It’s a simple three-step deployment process with essentially no learning curve, as evidenced by the fact that in FRONTIER II, the technical success rate starting from no experience was 97%, explained Dr. Schwindt of St. Franziskus Hospital in Muenster, Germany.

The large femoral arteriotomies created for TAVR or endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair have typically required surgical cut down and sutured repair with a 3- to 5-cm incision. Vascular complications have been common. Indeed, the literature shows this method entails on average a 14.7% rate of major vascular complications up to 3 months post procedure, so that was the bar set in FRONTIER II: In order for the PerQseal to be deemed noninferior to surgical cut down and sutured repair, the rate of major complications directly related to the novel device at 3 months follow-up could be no greater than 14.7%. The current Valve Academic Research Consortium (VARC) 2 definition of major complications was used.

In fact, the vascular complication rate proved to be zero. Moreover, at 12 months of follow-up, no cases of groin fibrosis or scarring had been observed, Dr. Schwindt reported.

FRONTIER II was a single-arm, prospective, multicenter European study of 58 patients who received the PerQseal device for 66 closures. They were evaluated at discharge and 1, 3, and 12 months post procedure by Doppler ultrasound, with uniformly unremarkable findings.

PerQseal features a synthetic low-profile implant with over-the-wire delivery. The implant is loaded into a sheath, released by pulling back on the sheath, then pulled up against the arteriotomy from the inside. Blood pressure molds the device to the arterial wall and seals it. The device is fully absorbed in 180 days.

Session co-chair Dr. Ted E. Feldman was favorably impressed.

“This is really terrific. It’s very nice to see we’re finally making progress with large-bore closure devices,” commented Dr. Feldman, professor of medicine at Northwestern University, Chicago.

Dr. Schwindt reported receiving a research grant from Vivasure, which sponsored the FRONTIER II study. In addition, he serves as a consultant to a half dozen medical device companies.

PARIS – A new bioabsorbable sutureless device provides operators with a safe, simple, and dependable option for fully percutaneous closure of the large, 12-24 French femoral arteriotomies created for transcatheter aortic valve replacement or endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair, Arne Schwindt, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

He presented the 12-month follow-up results of the FRONTIER II study of the Vivasure PerQseal device. The device recently received European marketing approval on the strength of FRONTIER II but remains investigational in the United States.

The PerQseal device is deployed in less than 1 minute at the end of the primary procedure and achieves immediate hemostasis. It’s a simple three-step deployment process with essentially no learning curve, as evidenced by the fact that in FRONTIER II, the technical success rate starting from no experience was 97%, explained Dr. Schwindt of St. Franziskus Hospital in Muenster, Germany.

The large femoral arteriotomies created for TAVR or endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair have typically required surgical cut down and sutured repair with a 3- to 5-cm incision. Vascular complications have been common. Indeed, the literature shows this method entails on average a 14.7% rate of major vascular complications up to 3 months post procedure, so that was the bar set in FRONTIER II: In order for the PerQseal to be deemed noninferior to surgical cut down and sutured repair, the rate of major complications directly related to the novel device at 3 months follow-up could be no greater than 14.7%. The current Valve Academic Research Consortium (VARC) 2 definition of major complications was used.

In fact, the vascular complication rate proved to be zero. Moreover, at 12 months of follow-up, no cases of groin fibrosis or scarring had been observed, Dr. Schwindt reported.

FRONTIER II was a single-arm, prospective, multicenter European study of 58 patients who received the PerQseal device for 66 closures. They were evaluated at discharge and 1, 3, and 12 months post procedure by Doppler ultrasound, with uniformly unremarkable findings.

PerQseal features a synthetic low-profile implant with over-the-wire delivery. The implant is loaded into a sheath, released by pulling back on the sheath, then pulled up against the arteriotomy from the inside. Blood pressure molds the device to the arterial wall and seals it. The device is fully absorbed in 180 days.

Session co-chair Dr. Ted E. Feldman was favorably impressed.

“This is really terrific. It’s very nice to see we’re finally making progress with large-bore closure devices,” commented Dr. Feldman, professor of medicine at Northwestern University, Chicago.

Dr. Schwindt reported receiving a research grant from Vivasure, which sponsored the FRONTIER II study. In addition, he serves as a consultant to a half dozen medical device companies.

PARIS – A new bioabsorbable sutureless device provides operators with a safe, simple, and dependable option for fully percutaneous closure of the large, 12-24 French femoral arteriotomies created for transcatheter aortic valve replacement or endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair, Arne Schwindt, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

He presented the 12-month follow-up results of the FRONTIER II study of the Vivasure PerQseal device. The device recently received European marketing approval on the strength of FRONTIER II but remains investigational in the United States.

The PerQseal device is deployed in less than 1 minute at the end of the primary procedure and achieves immediate hemostasis. It’s a simple three-step deployment process with essentially no learning curve, as evidenced by the fact that in FRONTIER II, the technical success rate starting from no experience was 97%, explained Dr. Schwindt of St. Franziskus Hospital in Muenster, Germany.

The large femoral arteriotomies created for TAVR or endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair have typically required surgical cut down and sutured repair with a 3- to 5-cm incision. Vascular complications have been common. Indeed, the literature shows this method entails on average a 14.7% rate of major vascular complications up to 3 months post procedure, so that was the bar set in FRONTIER II: In order for the PerQseal to be deemed noninferior to surgical cut down and sutured repair, the rate of major complications directly related to the novel device at 3 months follow-up could be no greater than 14.7%. The current Valve Academic Research Consortium (VARC) 2 definition of major complications was used.

In fact, the vascular complication rate proved to be zero. Moreover, at 12 months of follow-up, no cases of groin fibrosis or scarring had been observed, Dr. Schwindt reported.

FRONTIER II was a single-arm, prospective, multicenter European study of 58 patients who received the PerQseal device for 66 closures. They were evaluated at discharge and 1, 3, and 12 months post procedure by Doppler ultrasound, with uniformly unremarkable findings.

PerQseal features a synthetic low-profile implant with over-the-wire delivery. The implant is loaded into a sheath, released by pulling back on the sheath, then pulled up against the arteriotomy from the inside. Blood pressure molds the device to the arterial wall and seals it. The device is fully absorbed in 180 days.

Session co-chair Dr. Ted E. Feldman was favorably impressed.

“This is really terrific. It’s very nice to see we’re finally making progress with large-bore closure devices,” commented Dr. Feldman, professor of medicine at Northwestern University, Chicago.

Dr. Schwindt reported receiving a research grant from Vivasure, which sponsored the FRONTIER II study. In addition, he serves as a consultant to a half dozen medical device companies.

AT EUROPCR 2016

Key clinical point: The PerQseal device provides a simpler alternative to existing closure methods.

Major finding: No major vascular complications were seen during structured follow-up of recipients of the novel bioabsorbable fully percutaneous PerQseal device for closure of large-bore femoral arteriotomies.

Data source: FRONTIER II was a prospective, single-arm, 12-month multicenter study including 58 patients who underwent closure of 66 large femoral arteriotomies using the PerQseal device.

Disclosures: The presenter reported receiving a research grant from Vivasure, which sponsored the FRONTIER II study.

Most interventional cardiologists don’t fully grasp radiation risks

PARIS – What most interventional cardiologists and electrophysiologists do not know about their health risks due to occupational radiation exposure and how best to protect themselves could fill a book – or better still, make for an illuminating 2-hour expert panel discussion at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

“There’s a problem of lack of awareness on the part of interventional cardiologists, and also of institutional insensitivity to the problem,” declared Emanuela Piccaluga, MD, an investigator in the eye-opening Healthy Cath Lab study. This Italian national study showed that cardiac catheterization laboratory staff had radiation exposure duration–dependent increased risks of cataracts, cancers, and skin lesions, as well as other radiogenic noncancer effects: anxiety and depression, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia.

Cardiologists at some European hospitals have to pay for their own lead aprons and other protective gear. And even if the hospital does pick up the bill, administrators often balk at authorizing replacement of a lead apron that has developed microfractures and cracks. They view these imperfections as cosmetic defects, unaware that the damage renders the apron less protective, according to Dr. Piccaluga of Niguarda Ca’ Granda Hospital in Milan.

Ariel Roguin, MD, head of interventional cardiology at Rambam Medical Center in Haifa, Israel, said every cardiologist working with radiation should understand the three principles of radiation reduction, which he refers to in shorthand as “TDS,” for Time, Distance, and Shielding. Radiation is here to stay in cardiology, he said, but interventionalists can maximize their safety by keeping the fluoroscopy time and number of acquired images down, standing as far away as possible from both the radiation source and patient while still getting the job done well, and using appropriate shielding routinely.

Dr. Roguin gained notoriety with his report that 26 of 30 interventional cardiologists with glioblastoma multiforme or other brain malignancies had left-hemisphere cancers and 1 had a midline malignancy; only 3 were right-sided (Eur Heart J. 2014 Mar;35[10]:599-600). That distribution is highly unlikely to be due to play of chance, given that an interventional cardiologist’s left side is the side that’s usually exposed to more radiation.

“We should form a wall against radiation. Apart from the leaded aprons, for every procedure we all should also use lead skirts going from the table to the floor to block backscatter, ceiling-mounted overhead radiation shields, special glasses to protect against cataracts, and thyroid collars. And it’s very important to wear a dosimeter with sound; it helps increase awareness of our exposure,” he said.

Dr. Roguin has been a pioneer in the use of a thin, 0.5-mm lead shield draped across the patient’s abdomen from the umbilicus down during radial-access angiography. In a 322-patient randomized trial, he and his coinvestigators showed that this practice results in a threefold reduction in radiation to the operator, albeit at the cost of doubling the patient’s radiation exposure (Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2015 Jun;85[7]:1164-70).

“We now routinely do our radials with the lead apron across the patient’s abdomen. We’ve reached the conclusion that we work with radiation in the cath lab every day for many years and the patient is there only once or twice in a lifetime, hopefully,” the cardiologist explained.

With the growing popularity of radial-access interventions, audience members wanted to know if there is an advantage in terms of radiation exposure to left versus right radial artery access. The answer is no, according to Dr. Roguin.

“There are several studies showing no difference in radiation exposure. Left radial artery access is faster, but you’re leaning on the patient and getting more radiation as a result, while with right radial access you have to do more catheter manipulation, which takes longer. Both approaches involve more radiation to the operator than the transfemoral approach,” he said.

Dr. Piccaluga presented highlights from the Healthy Cath Lab study, sponsored by the Italian Society of Invasive Cardiology and the Italian National Research Council’s Institute of Clinical Physiology. The study involved detailed self-administered questionnaires completed by 218 interventional cardiologists and electrophysiologists, 191 nurses, and 57 technicians regularly exposed to ionizing radiation in the cardiac cath lab for a median of 10 years, along with 280 unexposed controls.

A variety of health problems were more frequent in the cath lab personnel regularly exposed to radiation. Rates were consistently highest in the cardiologists, followed next by the cath lab nurses, and then the radiation technicians.

Rates of health problems were highest in the 227 individuals with at least 13 years of cath lab radiation exposure. For example, their adjusted risks of cataracts, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and cancers were respectively 9-, 1.7-, 2.9-, and 4.5-fold fold greater than in unexposed controls, as detailed in a recent report (Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2016 April. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.115.003273).

Dr. Piccaluga also shared data from several other pertinent recent studies in which she was a coinvestigator. In one, 83 cardiologists and nurses working in cardiac catheterization laboratories and 83 matched radiation-nonexposed controls completed a neuropsychological test battery. The radiation-exposed group scored significantly lower on measures of delayed recall, visual short-term memory, and verbal fluency, all of which are skills located in left hemisphere structures of the brain – the side with more exposure to ionizing radiation during interventional procedures (J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2015 Oct;21[9]:670-6).

In another study, Dr. Piccaluga and her coinvestigators had participants perform an odor-sniffing test. Olfactory discrimination in the cardiac cath lab staffers was significantly diminished in a pattern that has been identified in other studies as an early signal of impending clinical onset of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases (Int J Cardiol. 2014 Feb 15;171[3]:461-3).

And in yet another study, Dr. Piccaluga and her coworkers found that left and right carotid intima-media thickness as measured by ultrasound in cardiac cath lab personnel having high lifetime radiation exposure was significantly greater than in those with low exposure and in nonexposed controls. In the left carotid artery, but not the right, intimal-medial thickness was significantly correlated with a total occupational radiologic risk score.

Moreover, the Italian investigators found a significant reduction in leukocyte telomere length – a biomarker for accelerated vascular aging – in cardiac cath lab staff regularly exposed to ionizing radiation, compared with controls (JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2015 Apr 20;8[4]:616-27).

All of these findings, she stressed, make a persuasive case for interventional cardiologists doing everything they can to protect themselves from unnecessary radiation exposure at all times.

How to best go about accomplishing this was the territory covered by Alaide Chieffo, MD, of San Raffaele Scientific Institute in Milan.

The patient-related factors germane to radiation dose – procedure complexity and body thickness – are outside physician control. But there are plenty of operator-dependent factors, including, for starters, procedural experience. In one classic study, Dr. Chieffo noted, Greek investigators showed that interventional cardiologists’ radiation exposure dose was 60% greater in their first year of practice than in their second year.

Distance from the patient is crucial, she observed, since the patient is the greatest source of radiation to the operator. If the operator is 35 cm from the patient, the radiation exposure is fourfold greater than at a distance of 70 cm. At a distance of 17.5 cm, the exposure intensity is 16-fold greater than at a 70-cm distance. And at 8.8 cm of distance, it’s 64 times greater.

Image acquisition is another key variable within the interventionalist’s control. Cine images entail 12- to 20-times greater radiation doses than those of fluoroscopy, so don’t resort to cine when fluoroscopy will do. Also, reducing the fluoroscopy frame rate from 15 to 7.5 frames per second significantly decreases the amount of radiation released while providing images of adequate quality for many procedures. Tight collimation, the use of manually inserted wedge filters, and thoughtful selection of tube angulations result in less radiation for both patient and physician. It has been shown that tube angulations that expose a patient to intense radiation levels increase the operator’s radiation exposure exponentially. The least-irradiating tube angulations are caudal posteroanterior 0°/30°– angulation for the left coronary main stem, cranial posteroanterior 0°/30°+ for the left anterior descending coronary artery bifurcation, and right anterior oblique views of 40° or more. Left anterior oblique projections are the most radiation intensive, according to a comprehensive study (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004 Oct 6;44[7]:1420-8), Dr. Chieffo continued.

Panelist Ghada Mikhail, MD, of Imperial College London, said there is some relatively new operator protective gear available. She cited lightweight protective caps, for example, but an audience show of hands indicated almost no one uses them.

“Protectors for the breasts and gonads are available. You can wear them underneath the lead. The extra time to put them on is worthwhile,” she said.

“I think the risk of radiation is completely underestimated,” Dr. Mikhail added. “We have a responsibility to young trainees to teach them about radiation protection, which a lot of institutions and supervisors don’t do. That’s partly because a lot of them don’t know the details.”

All of the speakers indicated they had no financial conflicts regarding their presentations.

PARIS – What most interventional cardiologists and electrophysiologists do not know about their health risks due to occupational radiation exposure and how best to protect themselves could fill a book – or better still, make for an illuminating 2-hour expert panel discussion at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

“There’s a problem of lack of awareness on the part of interventional cardiologists, and also of institutional insensitivity to the problem,” declared Emanuela Piccaluga, MD, an investigator in the eye-opening Healthy Cath Lab study. This Italian national study showed that cardiac catheterization laboratory staff had radiation exposure duration–dependent increased risks of cataracts, cancers, and skin lesions, as well as other radiogenic noncancer effects: anxiety and depression, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia.

Cardiologists at some European hospitals have to pay for their own lead aprons and other protective gear. And even if the hospital does pick up the bill, administrators often balk at authorizing replacement of a lead apron that has developed microfractures and cracks. They view these imperfections as cosmetic defects, unaware that the damage renders the apron less protective, according to Dr. Piccaluga of Niguarda Ca’ Granda Hospital in Milan.

Ariel Roguin, MD, head of interventional cardiology at Rambam Medical Center in Haifa, Israel, said every cardiologist working with radiation should understand the three principles of radiation reduction, which he refers to in shorthand as “TDS,” for Time, Distance, and Shielding. Radiation is here to stay in cardiology, he said, but interventionalists can maximize their safety by keeping the fluoroscopy time and number of acquired images down, standing as far away as possible from both the radiation source and patient while still getting the job done well, and using appropriate shielding routinely.

Dr. Roguin gained notoriety with his report that 26 of 30 interventional cardiologists with glioblastoma multiforme or other brain malignancies had left-hemisphere cancers and 1 had a midline malignancy; only 3 were right-sided (Eur Heart J. 2014 Mar;35[10]:599-600). That distribution is highly unlikely to be due to play of chance, given that an interventional cardiologist’s left side is the side that’s usually exposed to more radiation.

“We should form a wall against radiation. Apart from the leaded aprons, for every procedure we all should also use lead skirts going from the table to the floor to block backscatter, ceiling-mounted overhead radiation shields, special glasses to protect against cataracts, and thyroid collars. And it’s very important to wear a dosimeter with sound; it helps increase awareness of our exposure,” he said.

Dr. Roguin has been a pioneer in the use of a thin, 0.5-mm lead shield draped across the patient’s abdomen from the umbilicus down during radial-access angiography. In a 322-patient randomized trial, he and his coinvestigators showed that this practice results in a threefold reduction in radiation to the operator, albeit at the cost of doubling the patient’s radiation exposure (Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2015 Jun;85[7]:1164-70).

“We now routinely do our radials with the lead apron across the patient’s abdomen. We’ve reached the conclusion that we work with radiation in the cath lab every day for many years and the patient is there only once or twice in a lifetime, hopefully,” the cardiologist explained.

With the growing popularity of radial-access interventions, audience members wanted to know if there is an advantage in terms of radiation exposure to left versus right radial artery access. The answer is no, according to Dr. Roguin.

“There are several studies showing no difference in radiation exposure. Left radial artery access is faster, but you’re leaning on the patient and getting more radiation as a result, while with right radial access you have to do more catheter manipulation, which takes longer. Both approaches involve more radiation to the operator than the transfemoral approach,” he said.

Dr. Piccaluga presented highlights from the Healthy Cath Lab study, sponsored by the Italian Society of Invasive Cardiology and the Italian National Research Council’s Institute of Clinical Physiology. The study involved detailed self-administered questionnaires completed by 218 interventional cardiologists and electrophysiologists, 191 nurses, and 57 technicians regularly exposed to ionizing radiation in the cardiac cath lab for a median of 10 years, along with 280 unexposed controls.

A variety of health problems were more frequent in the cath lab personnel regularly exposed to radiation. Rates were consistently highest in the cardiologists, followed next by the cath lab nurses, and then the radiation technicians.

Rates of health problems were highest in the 227 individuals with at least 13 years of cath lab radiation exposure. For example, their adjusted risks of cataracts, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and cancers were respectively 9-, 1.7-, 2.9-, and 4.5-fold fold greater than in unexposed controls, as detailed in a recent report (Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2016 April. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.115.003273).

Dr. Piccaluga also shared data from several other pertinent recent studies in which she was a coinvestigator. In one, 83 cardiologists and nurses working in cardiac catheterization laboratories and 83 matched radiation-nonexposed controls completed a neuropsychological test battery. The radiation-exposed group scored significantly lower on measures of delayed recall, visual short-term memory, and verbal fluency, all of which are skills located in left hemisphere structures of the brain – the side with more exposure to ionizing radiation during interventional procedures (J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2015 Oct;21[9]:670-6).

In another study, Dr. Piccaluga and her coinvestigators had participants perform an odor-sniffing test. Olfactory discrimination in the cardiac cath lab staffers was significantly diminished in a pattern that has been identified in other studies as an early signal of impending clinical onset of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases (Int J Cardiol. 2014 Feb 15;171[3]:461-3).

And in yet another study, Dr. Piccaluga and her coworkers found that left and right carotid intima-media thickness as measured by ultrasound in cardiac cath lab personnel having high lifetime radiation exposure was significantly greater than in those with low exposure and in nonexposed controls. In the left carotid artery, but not the right, intimal-medial thickness was significantly correlated with a total occupational radiologic risk score.

Moreover, the Italian investigators found a significant reduction in leukocyte telomere length – a biomarker for accelerated vascular aging – in cardiac cath lab staff regularly exposed to ionizing radiation, compared with controls (JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2015 Apr 20;8[4]:616-27).

All of these findings, she stressed, make a persuasive case for interventional cardiologists doing everything they can to protect themselves from unnecessary radiation exposure at all times.

How to best go about accomplishing this was the territory covered by Alaide Chieffo, MD, of San Raffaele Scientific Institute in Milan.

The patient-related factors germane to radiation dose – procedure complexity and body thickness – are outside physician control. But there are plenty of operator-dependent factors, including, for starters, procedural experience. In one classic study, Dr. Chieffo noted, Greek investigators showed that interventional cardiologists’ radiation exposure dose was 60% greater in their first year of practice than in their second year.

Distance from the patient is crucial, she observed, since the patient is the greatest source of radiation to the operator. If the operator is 35 cm from the patient, the radiation exposure is fourfold greater than at a distance of 70 cm. At a distance of 17.5 cm, the exposure intensity is 16-fold greater than at a 70-cm distance. And at 8.8 cm of distance, it’s 64 times greater.

Image acquisition is another key variable within the interventionalist’s control. Cine images entail 12- to 20-times greater radiation doses than those of fluoroscopy, so don’t resort to cine when fluoroscopy will do. Also, reducing the fluoroscopy frame rate from 15 to 7.5 frames per second significantly decreases the amount of radiation released while providing images of adequate quality for many procedures. Tight collimation, the use of manually inserted wedge filters, and thoughtful selection of tube angulations result in less radiation for both patient and physician. It has been shown that tube angulations that expose a patient to intense radiation levels increase the operator’s radiation exposure exponentially. The least-irradiating tube angulations are caudal posteroanterior 0°/30°– angulation for the left coronary main stem, cranial posteroanterior 0°/30°+ for the left anterior descending coronary artery bifurcation, and right anterior oblique views of 40° or more. Left anterior oblique projections are the most radiation intensive, according to a comprehensive study (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004 Oct 6;44[7]:1420-8), Dr. Chieffo continued.

Panelist Ghada Mikhail, MD, of Imperial College London, said there is some relatively new operator protective gear available. She cited lightweight protective caps, for example, but an audience show of hands indicated almost no one uses them.

“Protectors for the breasts and gonads are available. You can wear them underneath the lead. The extra time to put them on is worthwhile,” she said.

“I think the risk of radiation is completely underestimated,” Dr. Mikhail added. “We have a responsibility to young trainees to teach them about radiation protection, which a lot of institutions and supervisors don’t do. That’s partly because a lot of them don’t know the details.”

All of the speakers indicated they had no financial conflicts regarding their presentations.