Many patients with psychiatric illness have difficulty with medication adherence. Patients with impaired reality testing especially are at risk.

Keck and McElroy evaluated 141 patients who were initially hospitalized for bipolar disorder prospectively over 1 year to assess adherence with medication. During the follow-up period, 71 patients (51%) were partially or totally nonadherent with medication as prescribed. The most commonly cited reason for nonadherence was denial of need.1

Clinicians and patients face additional challenges due to the deleterious effects of relapse in the setting of both schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Almost all oral antipsychotic or mood stabilizer medications require a minimum dosing schedule to effectively treat these disorders, and some of these oral medications require regular laboratory monitoring. Moreover, some of the agents can have serious adverse effects (AEs), such as seizure or withdrawal, if stopped abruptly. Social support from family or friends may improve adherence, but many psychiatric outpatients have a smaller social support network than do patients without psychiatric illnesses.2

Long-acting injectable (LAI) antipsychotics have been available for the past 40 years. These medications have provided clinicians with an additional option for patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder who are nonadherent to their medication treatment plans or who desire an administration choice that is more convenient than daily oral pills.3-7 Some clinical practice guidelines recommend considering LAIs as a maintenance treatment for schizophrenia.5 Like the rest of the pharmacopoeia, these formulations have AEs, such as extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS), weight gain, and metabolic syndrome.1 The longer half-life of these drugs may make such effects difficult to reverse.

This article presents a case of the use of depot formulation paliperidone palmitate in an elderly patient with bipolar disorder who was previously on high-dose oral second generation antipsychotics. He developed severe parkinsonism during a protracted hospitalization that ended in death.

Case Presentation

Mr. W was a 68-year-old homeless white male with a history of coronary artery disease status-post coronary artery bypass surgery, obstructive sleep apnea, and bipolar 1 disorder who presented to a large rural VAMC emergency department (ED) as a transfer from an outside hospital (OSH). He originally presented at the OSH for vomiting and diarrhea, but while there, he was placed under involuntary psychiatric commitment. The involuntary commitment form noted him to be tangential and disorganized; he was found walking about the ED without clothes. During the initial psychiatry interview, the clinician noted a disorganized thought process. When asked about circumstances leading to admission, he stated he was “a scuba diver, pilot, actor, submarine commander.” He also reported he had given “seminars to 6,000 people,” he held a psychology degree, and he came from a family that owned part of the island of Kodiak, Alaska. Mr. W stated he had no mental health history and believed psychiatry was witchcraft. He reported having no hallucinations and stated he heard the voice of god. He also reported to have met god multiple times and to have been married to a supermodel.

Mr. W’s chart demonstrated a history of mental illness over 30 years and that he previously was prescribed psychiatric medications. He had multiple inpatient psychiatric admissions with grandiose ideations, disorganized behaviors, and hypersexuality. He had been prescribed quetiapine, divalproex, lithium, carbamazepine, and lorazepam. He was formally diagnosed in the past with bipolar 1 disorder. There also was a family history of psychiatric illness. His mother had received electroconvulsive therapy, and both parents had alcohol substance use disorder.

Mr. W had been homeless for 20 years and had several psychiatric admissions during this period. Mr. W also had chronic difficulty with obtaining food and taking medications as prescribed. Sometimes he would only be able to eat 1 to 2 meals per day. He often changed location and had lived in at least 7 different states. Currently, he was estranged from his family. About 19 years ago, his sister reported that the veteran had told her that he was Jesus Christ, per clinical records. His estranged sister’s statement was corroborated by past psychology consult records citing episodes of the patient hearing god 30 and 26 years before the current admission. His second ex-wife cited inappropriate sexual behavior in front of their children. He had difficulty in school, failed at least 2 grades, and joined the U.S. Navy in tenth grade. A Neurobehavioral Cognitive Status Examination given 19 years ago showed mild impairment on attention and severe impairment in memory.

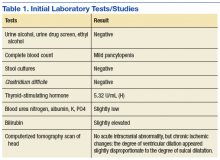

The physical examination on presentation to the OSH was unremarkable. Mr. W did not cooperate with formal neurocognitive testing, and he consistently made errors during orientation testing. Complete blood count from a OSH ED laboratory test was remarkable for a mild pancytopenia with a leukocyte count of 3,100 cells/mcL, hemoglobin 13.1 g/dL, and hematocrit 38.4%. Red cell distribution width was within normal limits at 13.5%. Stool cultures showed normal fecal flora and no salmonella, shigella, or campylobacter. Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) was slightly elevated at 5.32 U/mL. An electrocardiogram showed a QTc interval of 412 ms. A computerized tomography scan of his head showed no acute intracranial abnormality along with chronic ischemic changes in the brain (Table 1). Presumed cause of his nausea and diarrhea was viral gastroenteritis likely acquired at a homeless shelter.

Once stabilized, Mr. W was admitted to the VA hospital inpatient psychiatry unit under involuntary commitment for acute mania. Risperidone 0.25 mg orally twice a day was started for mood stabilization and psychosis along with trazodone 50 mg orally as needed for insomnia. Despite upward titration and change in frequency of the risperidone dose, Mr. W’s manic episode persisted. He remained on the psychiatric floor for 2 months (Figure). His TSH and free T4 were monitored during his stay, and levothyroxine was started. Risperidone was titrated to 8 mg/d. Mr. W’s Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) score decreased from 30 to 24. Mr. W had a mild improvement in irritability and speech rate but little change in elevated mood and delusional content.

He continued to endorse “speaking to god 16 times” even at the highest risperidone dose. The treatment team prescribed dissolvable risperidone tablets secondary to diversion concerns. In addition, the team added benztropine 0.5 mg once a day after observing a stooped posture and decreased arm swing. Mr. W noted risperidone made him “lethargic” and that his “body did not need” it. After 1 month of treatment with risperidone, the treatment team decided to cross taper the veteran from risperidone to a combination of olanzapine and divalproex secondary to inadequate treatment response.

The inpatient team started Mr. W on oral disintegrating tablets of olanzapine 5 mg once a day, and oral divalproex 1,000 mg once a day. An intramuscular backup of olanzapine was made available if oral medication was refused. Divalproex was titrated to 1,250 mg once a day to target a serum level of 61.7 µg/mL, and olanzapine was titrated to 10 mg once a day. After 9 days, the veteran showed moderate improvement in mania symptoms with a YMRS score < 20, indicating the absence of mania. However, the veteran made it very clear that he would stop taking the prescribed medication on discharge. The team elected to initiate a LAI.

The veteran received his first injection of the LAI psychiatric medication paliperidone palmitate 234 mg and a second 156-mg injection of the same medication 1 week later as per loading protocol. He was concurrently on daily oral divalproex 1,250 mg and olanzapine 10 mg. Mr. W continued to note he felt sedated during this period; his sedation worsened after the second injection. He also began to forget the location of his room and developed mumbled speech. His gait deteriorated to where he required a walker 6 days after injection and a wheelchair 3 days later. He became incontinent of urine and feces. Mr. W exhibited masked facies with severe drooling. This eventually progressed to difficulty swallowing. At the advice of speech pathology, he was downgraded to a pureed and nectar-thick liquid diet. He required assistance with meals.

Because of his sedation and parkinsonism symptoms, he was tapered off both olanzapine and divalproex. His last dose of olanzapine was on the date of his first injection and last dose of divalproex was 15 days after the second injection. The benztropine, which was originally given to counteract the effects of risperidone monotherapy, was discontinued over concern of anticholinergic load and sedation. The neurology consultant recommended carbidopa 25 mg and levodopa 100 mg 3 times per day for treatment of parkinsonism symptoms. Mr. W was only able to take 1 dose because of trouble swallowing. Twenty days after his second injection, a rapid response team (local clinical team 1 step below a code team) was called as Mr. W was unusually lethargic and unable to eat. He was then transferred to the medical floor.

While on the medical floor, dobhoff tube access was established for nutrition and to allow administration of carbidopa and levodopa. Mr. W could still speak at this time and was distraught. He stated, “I don’t know why god would do this to me.” Further workup was performed to look for other etiologies of the patient’s change in status. Creatinine kinase testing, lumbar puncture with cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) bacterial culture, CSF cryptococcal testing, and syphilis antigens were all negative. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain demonstrated diffuse cerebral atrophy with widened cistern and sulci resulting in ex vacuo dilatation.

Neurology thought that the ventriculomegaly did not have features of normal pressure hydrocephalus and was secondary to chronic ischemic demyelination caused by chronic malnutrition. During follow-up visits, the veteran was less and less verbal. It progressed to where he answered questions only in grunts. Eight days after transfer to the medical floor, Mr. W was noted to have his neck locked in a laterally rotated position with clonus of the sternocleidomastoid. Due to concern about possibility of neck dystonia and the poor adherence of the patient with carbidopa and levodopa given orally, the psychiatric team made the recommendation to start benztropine 1 mg given twice a day, delivered via the dobhoff tube to treat both the parkinsonism and dystonia. The following day Mr. W failed a repeat swallow study and was no longer allowed to receive anything orally.

Mild icterus and jaundice were noted on physical examination along with transaminitis and elevated bilirubin. He developed a fever. Thirteen days after transfer to the medical floor, blood cultures revealed Klebsiella septicemia. Benztropine was discontinued at this time because of concern the medication was causing or exacerbating the fever. While being treated for Klebsiella sepsis, the psychiatry team addressed his continued hypophonia, inability to ambulate, masked facies, and neck dystonia with diphenhydramine 50 mg given intramuscular (IM) twice per day.

Mr. W developed several more iatrogenic complications near this time, including urinary tract infection septicemia and acute hypoxic respiratory failure with lung infiltrate on X-ray, requiring ventilator support. His clinical status led to a number of transfers in and out of the medical intensive care unit (MICU). During this time, his parkinsonism symptoms were managed through a combination of carbidopa and levodopa and amantadine. Cervical dystonia was managed with botulism toxin injections. Mr. W spent 6 weeks in the MICU until the decision was made to terminate life support, and he was taken off the ventilator. He died shortly thereafter. Autopsy findings suggested that Mr. W had severe Alzheimer disease.