User login

THE CASE

A 49-year-old woman presented to our clinic with concerns about the changing appearance of her tongue over the past 2 to 3 weeks. She had been given a diagnosis of celiac disease by her gastroenterologist approximately 5 years earlier. At the time of that diagnosis, she had smooth patches on the surface of her tongue with missing papillae and slightly raised borders. (This gave her tongue a map-like appearance, consistent with geographic tongue [GT].) The patient’s symptoms improved after she started a gluten-free diet, but she reported occasional noncompliance over the past year.

At the current presentation, the patient noted that new lesions on the tongue had started as diffuse shiny red patches surrounded by clearly delineated white borders, ultimately progressing to structural changes. She denied any burning of the tongue or other oral symptoms but reported feelings of anxiety, a “foggy mind,” and diffuse arthralgia for the past several weeks. The patient’s list of medications included vitamin D and magnesium supplements, a multivitamin, and probiotics.

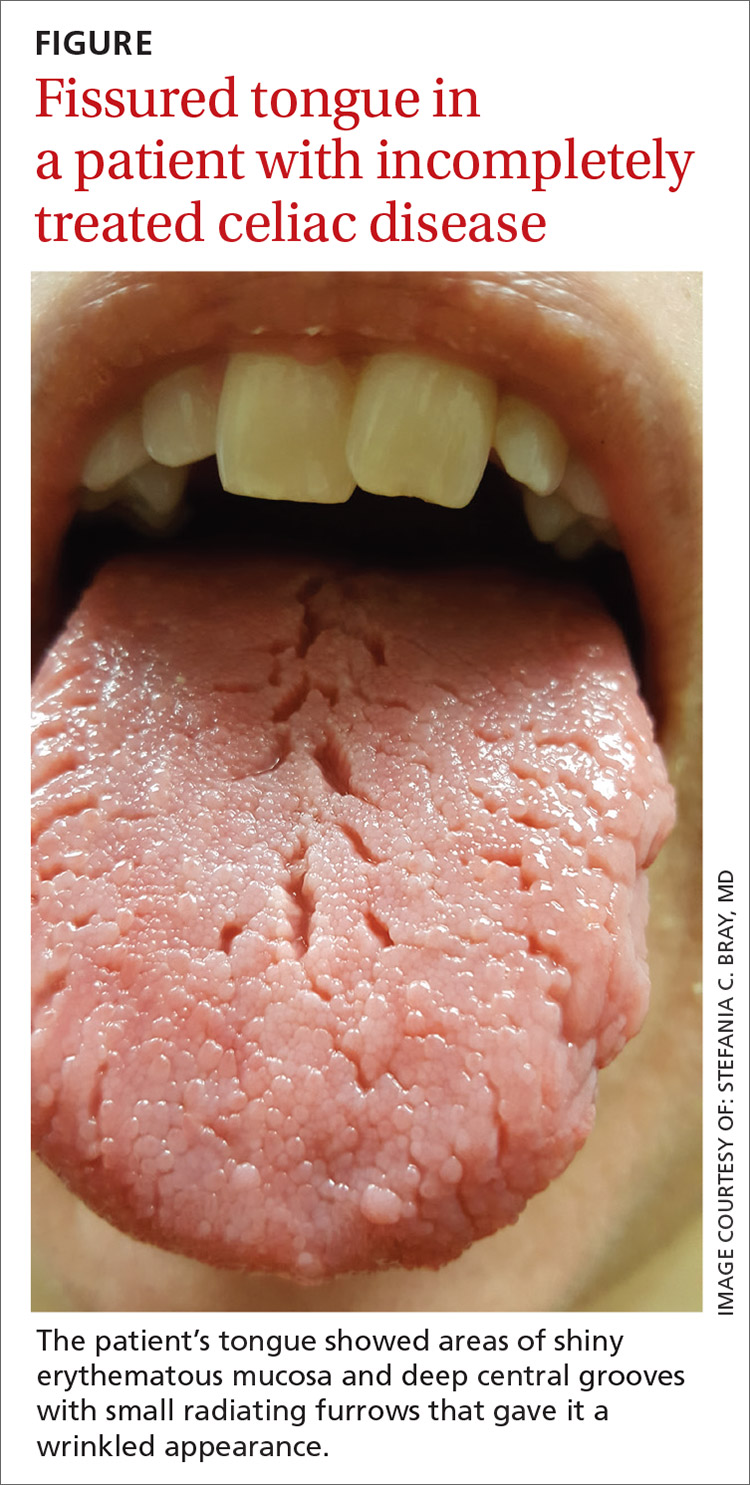

On physical examination, her tongue showed areas of shiny erythematous mucosa and deep central grooves with small radiating furrows giving a wrinkled appearance (FIGURE). A review of systems revealed nonspecific abdominal pain including bloating, cramping, and gas for the previous few months. An examination of her throat and oral cavity was unremarkable, and the remainder of the physical examination was normal.

THE DIAGNOSIS

A diagnosis of fissured tongue (FT) was suspected based on the clinical appearance of the patient’s tongue. Laboratory studies including a complete blood count; antinuclear antibody test; rheumatoid factor test; anticyclic citrullinated peptide test; a comprehensive metabolic panel; and thyroid-stimulating hormone, 25-hydroxyvitamin D, and vitamin B₁₂ level tests were performed based on her symptoms and current medications to rule out any other potential diagnoses. All laboratory results were normal, and a tissue transglutaminase IgA test was not repeated because it was positive when previously tested by the gastroenterologist at the time of her celiac disease diagnosis. A diagnosis of FT due to incompletely treated celiac disease was confirmed.

DISCUSSION

Clinical presentation. FT commonly presents in association with GT,1,2 with some cases of GT naturally progressing to FT.3,4 In most cases, FT is asymptomatic unless debris becomes entrapped in the fissures. Rarely, patients may complain of a burning sensation on the tongue. The clinical appearance of the tongue includes deep grooves with possible malodor or halitosis along with discoloration if trapping of debris and subsequent inflammation occurs.1

Etiology. FT has been linked to celiac disease; systemic conditions such as arthritis, iron deficiency, depression, anxiety, and neuropathy; and poor oral hygiene. Genetics also may play a role, as some cases of FT may be inherited. Getting to the source requires a careful history to uncover signs and symptoms (that may not have been reported until now) and to determine if other family members also have FT. A careful examination of the oral cavity, with an eye toward the patient’s oral hygiene, is also instructive (TABLE).5-8 In general, FT is believed to be a normal tongue variant in less than 10% of the general population.5,6 Additionally, local factors such as ill-fitting prosthesis, infection, parafunctional habits, allergic reaction, xerostomia, and galvanism have been implicated in the etiology of FT.5

In our patient, progression of GT to FT was caused by incompletely treated celiac disease. Both FT and GT may represent different reaction patterns caused by the same hematologic and immunologic diseases.3 In fact, the appearance of the tongue may aid in the diagnosis of celiac disease, which has been observed in 15% of patients with GT.7 Fissured tongue also may indicate an inability of the gastrointestinal mucosa to absorb nutrients; therefore, close nutrition monitoring is recommended.9

Continue to: Other oral and dental manifestations...

Other oral and dental manifestations of celiac disease include enamel defects, delayed tooth eruption, recurrent aphthous ulcers, cheilosis, oral lichen planus, and atrophic glossitis.10 Our patient also reported anxiety, “foggy mind,” diffuse arthralgia, and abdominal pain, which are symptoms of uncontrolled celiac disease. There is no known etiology of tongue manifestations in patients with incompletely treated celiac disease.

Treatment. FT generally does not require specific therapy other than the treatment of the underlying inflammatory condition. It is important to maintain proper oral and dental care, such as brushing the top surface of the tongue to clean and remove food debris. Bacteria and plaque can collect in the fissures, leading to bad breath and an increased potential for tooth decay.

Our patient was referred to a dietitian to assist with adherence to the gluten-free diet. At follow-up 3 months later, the appearance of her tongue had improved and fewer fissures were visible. The majority of her other symptoms also had resolved.

THE TAKEAWAY

FT may be a normal variant of the tongue in some patients or may be associated with poor oral hygiene. Additionally, FT often is associated with an underlying medical or inherited condition and may serve as a marker for an untreated or partially treated condition such as celiac disease, as was the case with our patient. When other signs or symptoms of systemic disease are present, further laboratory and endoscopic workup is necessary to rule out other causes and to diagnose celiac disease, if present.

As FT has been reported to be a natural progression from GT, the appearance of FT may indicate partial treatment of the underlying disease process and therefore more intensive therapy and follow-up would be needed. In this case, more intensive dietary guidance was provided with subsequent improvement of symptoms.

CORRESPONDENCE

Peter J. Carek, MD, MS, Department of Community Health and Family Medicine, College of Medicine, University of Florida, P.O. Box 100237, Gainesville, FL 32610-0237; carek@ufl.edu

1. Reamy BV, Cerby R, Bunt CW. Common tongue conditions in primary care. Am Fam Physician. 2010;81:627-634.

2. Yarom N, Cantony U, Gorsky M. Prevalence of fissured tongue, geographic tongue and median rhomboid glossitis among Israeli adults of different ethnic origins. Dermatology. 2004;209:88-94.

3. Dafar A, Cevik-Aras H, Robledo-Sierra J, et al. Factors associated with geographic tongue and fissured tongue. Acta Odontol Scad. 2016;74:210-216.

4. Hume WJ. Geographic stomatitis: a critical review. J Dent. 1975;3:25-43.

5. Sudarshan R, Sree Vijayabala G, Samata Y, et al. Newer classification system for fissured tongue: an epidemiological approach. J Tropical Med. doi:10.1155/2015/262079.

6. Mangold AR, Torgerson RR, Rogers RS. Diseases of the tongue. Clin Dermatol. 2016;34:458-469.

7. Cigic L, Galic T, Kero D, et al. The prevalence of celiac disease in patients with geographic tongue. J Oral Pathol Med. 2016;45:791-796.

8. Zargari O. The prevalence and significance of fissured tongue and geographical tongue in psoriatic patients. Clin Exp Dermatology. 2006;31:192-195.

9. Kullaa-Mikkonen A, Penttila I, Kotilainen R, et al. Haematological and immunological features of patients with fissured tongue syndrome. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1987;25:481-487.

10. Rashid M, Zarkadas M, Anca A, et al. Oral manifestations of celiac disease: a clinical guide for dentists. J Can Dent Assoc. 2011;77:b39.

THE CASE

A 49-year-old woman presented to our clinic with concerns about the changing appearance of her tongue over the past 2 to 3 weeks. She had been given a diagnosis of celiac disease by her gastroenterologist approximately 5 years earlier. At the time of that diagnosis, she had smooth patches on the surface of her tongue with missing papillae and slightly raised borders. (This gave her tongue a map-like appearance, consistent with geographic tongue [GT].) The patient’s symptoms improved after she started a gluten-free diet, but she reported occasional noncompliance over the past year.

At the current presentation, the patient noted that new lesions on the tongue had started as diffuse shiny red patches surrounded by clearly delineated white borders, ultimately progressing to structural changes. She denied any burning of the tongue or other oral symptoms but reported feelings of anxiety, a “foggy mind,” and diffuse arthralgia for the past several weeks. The patient’s list of medications included vitamin D and magnesium supplements, a multivitamin, and probiotics.

On physical examination, her tongue showed areas of shiny erythematous mucosa and deep central grooves with small radiating furrows giving a wrinkled appearance (FIGURE). A review of systems revealed nonspecific abdominal pain including bloating, cramping, and gas for the previous few months. An examination of her throat and oral cavity was unremarkable, and the remainder of the physical examination was normal.

THE DIAGNOSIS

A diagnosis of fissured tongue (FT) was suspected based on the clinical appearance of the patient’s tongue. Laboratory studies including a complete blood count; antinuclear antibody test; rheumatoid factor test; anticyclic citrullinated peptide test; a comprehensive metabolic panel; and thyroid-stimulating hormone, 25-hydroxyvitamin D, and vitamin B₁₂ level tests were performed based on her symptoms and current medications to rule out any other potential diagnoses. All laboratory results were normal, and a tissue transglutaminase IgA test was not repeated because it was positive when previously tested by the gastroenterologist at the time of her celiac disease diagnosis. A diagnosis of FT due to incompletely treated celiac disease was confirmed.

DISCUSSION

Clinical presentation. FT commonly presents in association with GT,1,2 with some cases of GT naturally progressing to FT.3,4 In most cases, FT is asymptomatic unless debris becomes entrapped in the fissures. Rarely, patients may complain of a burning sensation on the tongue. The clinical appearance of the tongue includes deep grooves with possible malodor or halitosis along with discoloration if trapping of debris and subsequent inflammation occurs.1

Etiology. FT has been linked to celiac disease; systemic conditions such as arthritis, iron deficiency, depression, anxiety, and neuropathy; and poor oral hygiene. Genetics also may play a role, as some cases of FT may be inherited. Getting to the source requires a careful history to uncover signs and symptoms (that may not have been reported until now) and to determine if other family members also have FT. A careful examination of the oral cavity, with an eye toward the patient’s oral hygiene, is also instructive (TABLE).5-8 In general, FT is believed to be a normal tongue variant in less than 10% of the general population.5,6 Additionally, local factors such as ill-fitting prosthesis, infection, parafunctional habits, allergic reaction, xerostomia, and galvanism have been implicated in the etiology of FT.5

In our patient, progression of GT to FT was caused by incompletely treated celiac disease. Both FT and GT may represent different reaction patterns caused by the same hematologic and immunologic diseases.3 In fact, the appearance of the tongue may aid in the diagnosis of celiac disease, which has been observed in 15% of patients with GT.7 Fissured tongue also may indicate an inability of the gastrointestinal mucosa to absorb nutrients; therefore, close nutrition monitoring is recommended.9

Continue to: Other oral and dental manifestations...

Other oral and dental manifestations of celiac disease include enamel defects, delayed tooth eruption, recurrent aphthous ulcers, cheilosis, oral lichen planus, and atrophic glossitis.10 Our patient also reported anxiety, “foggy mind,” diffuse arthralgia, and abdominal pain, which are symptoms of uncontrolled celiac disease. There is no known etiology of tongue manifestations in patients with incompletely treated celiac disease.

Treatment. FT generally does not require specific therapy other than the treatment of the underlying inflammatory condition. It is important to maintain proper oral and dental care, such as brushing the top surface of the tongue to clean and remove food debris. Bacteria and plaque can collect in the fissures, leading to bad breath and an increased potential for tooth decay.

Our patient was referred to a dietitian to assist with adherence to the gluten-free diet. At follow-up 3 months later, the appearance of her tongue had improved and fewer fissures were visible. The majority of her other symptoms also had resolved.

THE TAKEAWAY

FT may be a normal variant of the tongue in some patients or may be associated with poor oral hygiene. Additionally, FT often is associated with an underlying medical or inherited condition and may serve as a marker for an untreated or partially treated condition such as celiac disease, as was the case with our patient. When other signs or symptoms of systemic disease are present, further laboratory and endoscopic workup is necessary to rule out other causes and to diagnose celiac disease, if present.

As FT has been reported to be a natural progression from GT, the appearance of FT may indicate partial treatment of the underlying disease process and therefore more intensive therapy and follow-up would be needed. In this case, more intensive dietary guidance was provided with subsequent improvement of symptoms.

CORRESPONDENCE

Peter J. Carek, MD, MS, Department of Community Health and Family Medicine, College of Medicine, University of Florida, P.O. Box 100237, Gainesville, FL 32610-0237; carek@ufl.edu

THE CASE

A 49-year-old woman presented to our clinic with concerns about the changing appearance of her tongue over the past 2 to 3 weeks. She had been given a diagnosis of celiac disease by her gastroenterologist approximately 5 years earlier. At the time of that diagnosis, she had smooth patches on the surface of her tongue with missing papillae and slightly raised borders. (This gave her tongue a map-like appearance, consistent with geographic tongue [GT].) The patient’s symptoms improved after she started a gluten-free diet, but she reported occasional noncompliance over the past year.

At the current presentation, the patient noted that new lesions on the tongue had started as diffuse shiny red patches surrounded by clearly delineated white borders, ultimately progressing to structural changes. She denied any burning of the tongue or other oral symptoms but reported feelings of anxiety, a “foggy mind,” and diffuse arthralgia for the past several weeks. The patient’s list of medications included vitamin D and magnesium supplements, a multivitamin, and probiotics.

On physical examination, her tongue showed areas of shiny erythematous mucosa and deep central grooves with small radiating furrows giving a wrinkled appearance (FIGURE). A review of systems revealed nonspecific abdominal pain including bloating, cramping, and gas for the previous few months. An examination of her throat and oral cavity was unremarkable, and the remainder of the physical examination was normal.

THE DIAGNOSIS

A diagnosis of fissured tongue (FT) was suspected based on the clinical appearance of the patient’s tongue. Laboratory studies including a complete blood count; antinuclear antibody test; rheumatoid factor test; anticyclic citrullinated peptide test; a comprehensive metabolic panel; and thyroid-stimulating hormone, 25-hydroxyvitamin D, and vitamin B₁₂ level tests were performed based on her symptoms and current medications to rule out any other potential diagnoses. All laboratory results were normal, and a tissue transglutaminase IgA test was not repeated because it was positive when previously tested by the gastroenterologist at the time of her celiac disease diagnosis. A diagnosis of FT due to incompletely treated celiac disease was confirmed.

DISCUSSION

Clinical presentation. FT commonly presents in association with GT,1,2 with some cases of GT naturally progressing to FT.3,4 In most cases, FT is asymptomatic unless debris becomes entrapped in the fissures. Rarely, patients may complain of a burning sensation on the tongue. The clinical appearance of the tongue includes deep grooves with possible malodor or halitosis along with discoloration if trapping of debris and subsequent inflammation occurs.1

Etiology. FT has been linked to celiac disease; systemic conditions such as arthritis, iron deficiency, depression, anxiety, and neuropathy; and poor oral hygiene. Genetics also may play a role, as some cases of FT may be inherited. Getting to the source requires a careful history to uncover signs and symptoms (that may not have been reported until now) and to determine if other family members also have FT. A careful examination of the oral cavity, with an eye toward the patient’s oral hygiene, is also instructive (TABLE).5-8 In general, FT is believed to be a normal tongue variant in less than 10% of the general population.5,6 Additionally, local factors such as ill-fitting prosthesis, infection, parafunctional habits, allergic reaction, xerostomia, and galvanism have been implicated in the etiology of FT.5

In our patient, progression of GT to FT was caused by incompletely treated celiac disease. Both FT and GT may represent different reaction patterns caused by the same hematologic and immunologic diseases.3 In fact, the appearance of the tongue may aid in the diagnosis of celiac disease, which has been observed in 15% of patients with GT.7 Fissured tongue also may indicate an inability of the gastrointestinal mucosa to absorb nutrients; therefore, close nutrition monitoring is recommended.9

Continue to: Other oral and dental manifestations...

Other oral and dental manifestations of celiac disease include enamel defects, delayed tooth eruption, recurrent aphthous ulcers, cheilosis, oral lichen planus, and atrophic glossitis.10 Our patient also reported anxiety, “foggy mind,” diffuse arthralgia, and abdominal pain, which are symptoms of uncontrolled celiac disease. There is no known etiology of tongue manifestations in patients with incompletely treated celiac disease.

Treatment. FT generally does not require specific therapy other than the treatment of the underlying inflammatory condition. It is important to maintain proper oral and dental care, such as brushing the top surface of the tongue to clean and remove food debris. Bacteria and plaque can collect in the fissures, leading to bad breath and an increased potential for tooth decay.

Our patient was referred to a dietitian to assist with adherence to the gluten-free diet. At follow-up 3 months later, the appearance of her tongue had improved and fewer fissures were visible. The majority of her other symptoms also had resolved.

THE TAKEAWAY

FT may be a normal variant of the tongue in some patients or may be associated with poor oral hygiene. Additionally, FT often is associated with an underlying medical or inherited condition and may serve as a marker for an untreated or partially treated condition such as celiac disease, as was the case with our patient. When other signs or symptoms of systemic disease are present, further laboratory and endoscopic workup is necessary to rule out other causes and to diagnose celiac disease, if present.

As FT has been reported to be a natural progression from GT, the appearance of FT may indicate partial treatment of the underlying disease process and therefore more intensive therapy and follow-up would be needed. In this case, more intensive dietary guidance was provided with subsequent improvement of symptoms.

CORRESPONDENCE

Peter J. Carek, MD, MS, Department of Community Health and Family Medicine, College of Medicine, University of Florida, P.O. Box 100237, Gainesville, FL 32610-0237; carek@ufl.edu

1. Reamy BV, Cerby R, Bunt CW. Common tongue conditions in primary care. Am Fam Physician. 2010;81:627-634.

2. Yarom N, Cantony U, Gorsky M. Prevalence of fissured tongue, geographic tongue and median rhomboid glossitis among Israeli adults of different ethnic origins. Dermatology. 2004;209:88-94.

3. Dafar A, Cevik-Aras H, Robledo-Sierra J, et al. Factors associated with geographic tongue and fissured tongue. Acta Odontol Scad. 2016;74:210-216.

4. Hume WJ. Geographic stomatitis: a critical review. J Dent. 1975;3:25-43.

5. Sudarshan R, Sree Vijayabala G, Samata Y, et al. Newer classification system for fissured tongue: an epidemiological approach. J Tropical Med. doi:10.1155/2015/262079.

6. Mangold AR, Torgerson RR, Rogers RS. Diseases of the tongue. Clin Dermatol. 2016;34:458-469.

7. Cigic L, Galic T, Kero D, et al. The prevalence of celiac disease in patients with geographic tongue. J Oral Pathol Med. 2016;45:791-796.

8. Zargari O. The prevalence and significance of fissured tongue and geographical tongue in psoriatic patients. Clin Exp Dermatology. 2006;31:192-195.

9. Kullaa-Mikkonen A, Penttila I, Kotilainen R, et al. Haematological and immunological features of patients with fissured tongue syndrome. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1987;25:481-487.

10. Rashid M, Zarkadas M, Anca A, et al. Oral manifestations of celiac disease: a clinical guide for dentists. J Can Dent Assoc. 2011;77:b39.

1. Reamy BV, Cerby R, Bunt CW. Common tongue conditions in primary care. Am Fam Physician. 2010;81:627-634.

2. Yarom N, Cantony U, Gorsky M. Prevalence of fissured tongue, geographic tongue and median rhomboid glossitis among Israeli adults of different ethnic origins. Dermatology. 2004;209:88-94.

3. Dafar A, Cevik-Aras H, Robledo-Sierra J, et al. Factors associated with geographic tongue and fissured tongue. Acta Odontol Scad. 2016;74:210-216.

4. Hume WJ. Geographic stomatitis: a critical review. J Dent. 1975;3:25-43.

5. Sudarshan R, Sree Vijayabala G, Samata Y, et al. Newer classification system for fissured tongue: an epidemiological approach. J Tropical Med. doi:10.1155/2015/262079.

6. Mangold AR, Torgerson RR, Rogers RS. Diseases of the tongue. Clin Dermatol. 2016;34:458-469.

7. Cigic L, Galic T, Kero D, et al. The prevalence of celiac disease in patients with geographic tongue. J Oral Pathol Med. 2016;45:791-796.

8. Zargari O. The prevalence and significance of fissured tongue and geographical tongue in psoriatic patients. Clin Exp Dermatology. 2006;31:192-195.

9. Kullaa-Mikkonen A, Penttila I, Kotilainen R, et al. Haematological and immunological features of patients with fissured tongue syndrome. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1987;25:481-487.

10. Rashid M, Zarkadas M, Anca A, et al. Oral manifestations of celiac disease: a clinical guide for dentists. J Can Dent Assoc. 2011;77:b39.