User login

Click for Credit: Endometriosis surgery benefits; diabetes & aging; more

Here are 5 articles from the March issue of Clinician Reviews (individual articles are valid for one year from date of publication—expiration dates below):

1. Endometriosis surgery: Women can expect years-long benefits

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2Ez8mdu

Expires January 3, 2019

2. Cerebral small vessel disease progression linked to MCI in hypertensive patients

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2ExDV7o

Expires January 4, 2019

3. Adult atopic dermatitis is fraught with dermatologic comorbidities

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2Vl7E9a

Expires January 11, 2019

4. Antidepressants tied to greater hip fracture incidence in older adults

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2GRfMeH

Expires January 4, 2019

5. Researchers exploring ways to mitigate aging’s impact on diabetes

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2tFxF7v

Expires January 8, 2019

Here are 5 articles from the March issue of Clinician Reviews (individual articles are valid for one year from date of publication—expiration dates below):

1. Endometriosis surgery: Women can expect years-long benefits

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2Ez8mdu

Expires January 3, 2019

2. Cerebral small vessel disease progression linked to MCI in hypertensive patients

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2ExDV7o

Expires January 4, 2019

3. Adult atopic dermatitis is fraught with dermatologic comorbidities

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2Vl7E9a

Expires January 11, 2019

4. Antidepressants tied to greater hip fracture incidence in older adults

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2GRfMeH

Expires January 4, 2019

5. Researchers exploring ways to mitigate aging’s impact on diabetes

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2tFxF7v

Expires January 8, 2019

Here are 5 articles from the March issue of Clinician Reviews (individual articles are valid for one year from date of publication—expiration dates below):

1. Endometriosis surgery: Women can expect years-long benefits

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2Ez8mdu

Expires January 3, 2019

2. Cerebral small vessel disease progression linked to MCI in hypertensive patients

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2ExDV7o

Expires January 4, 2019

3. Adult atopic dermatitis is fraught with dermatologic comorbidities

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2Vl7E9a

Expires January 11, 2019

4. Antidepressants tied to greater hip fracture incidence in older adults

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2GRfMeH

Expires January 4, 2019

5. Researchers exploring ways to mitigate aging’s impact on diabetes

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2tFxF7v

Expires January 8, 2019

Click for Credit: Missed HIV screening opps; aspirin & preeclampsia; more

Here are 5 articles from the February issue of Clinician Reviews (individual articles are valid for one year from date of publication—expiration dates below):

1. Short-term lung function better predicts mortality risk in SSc

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2RrRuIY

Expires November 26, 2019

2. Healthier lifestyle in midlife women reduces subclinical carotid atherosclerosis

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2TvDH5G

Expires November 28, 2019

3. Three commonly used quick cognitive assessments often yield flawed results

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2G1qkHn

Expires November 28, 2019

4. Missed HIV screening opportunities found among subsequently infected youth

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2HGa8Nm

Expires November 29, 2019

5. Aspirin appears underused to prevent preeclampsia in SLE patients

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2G0dU2v

Expires January 2, 2019

Here are 5 articles from the February issue of Clinician Reviews (individual articles are valid for one year from date of publication—expiration dates below):

1. Short-term lung function better predicts mortality risk in SSc

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2RrRuIY

Expires November 26, 2019

2. Healthier lifestyle in midlife women reduces subclinical carotid atherosclerosis

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2TvDH5G

Expires November 28, 2019

3. Three commonly used quick cognitive assessments often yield flawed results

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2G1qkHn

Expires November 28, 2019

4. Missed HIV screening opportunities found among subsequently infected youth

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2HGa8Nm

Expires November 29, 2019

5. Aspirin appears underused to prevent preeclampsia in SLE patients

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2G0dU2v

Expires January 2, 2019

Here are 5 articles from the February issue of Clinician Reviews (individual articles are valid for one year from date of publication—expiration dates below):

1. Short-term lung function better predicts mortality risk in SSc

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2RrRuIY

Expires November 26, 2019

2. Healthier lifestyle in midlife women reduces subclinical carotid atherosclerosis

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2TvDH5G

Expires November 28, 2019

3. Three commonly used quick cognitive assessments often yield flawed results

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2G1qkHn

Expires November 28, 2019

4. Missed HIV screening opportunities found among subsequently infected youth

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2HGa8Nm

Expires November 29, 2019

5. Aspirin appears underused to prevent preeclampsia in SLE patients

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2G0dU2v

Expires January 2, 2019

Click for Credit: STIs on the rise; psoriasis & cardiac risk; more

Here are 5 articles from the January issue of Clinician Reviews (individual articles are valid for one year from date of publication—expiration dates below):

1. Can ultrasound screening improve survival in ovarian cancer?

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2Vtuc8F

Expires October 17, 2019

2. Higher BMI associated with greater loss of gray matter volume in MS

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2ArvFDp

Expires October 29, 2019

3. Psoriasis adds to increased risk of cardiovascular procedures, surgery in patients with hypertension

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2sbnkiS

Expires October 31, 2019

4. Fever, intestinal symptoms may delay diagnosis of Kawasaki disease in children

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2RdPoBi

Expires October 31, 2019

5. Rate of STIs is rising, and many U.S. teens are sexually active

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2CPuYFW

Expires November 8, 2019

Here are 5 articles from the January issue of Clinician Reviews (individual articles are valid for one year from date of publication—expiration dates below):

1. Can ultrasound screening improve survival in ovarian cancer?

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2Vtuc8F

Expires October 17, 2019

2. Higher BMI associated with greater loss of gray matter volume in MS

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2ArvFDp

Expires October 29, 2019

3. Psoriasis adds to increased risk of cardiovascular procedures, surgery in patients with hypertension

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2sbnkiS

Expires October 31, 2019

4. Fever, intestinal symptoms may delay diagnosis of Kawasaki disease in children

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2RdPoBi

Expires October 31, 2019

5. Rate of STIs is rising, and many U.S. teens are sexually active

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2CPuYFW

Expires November 8, 2019

Here are 5 articles from the January issue of Clinician Reviews (individual articles are valid for one year from date of publication—expiration dates below):

1. Can ultrasound screening improve survival in ovarian cancer?

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2Vtuc8F

Expires October 17, 2019

2. Higher BMI associated with greater loss of gray matter volume in MS

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2ArvFDp

Expires October 29, 2019

3. Psoriasis adds to increased risk of cardiovascular procedures, surgery in patients with hypertension

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2sbnkiS

Expires October 31, 2019

4. Fever, intestinal symptoms may delay diagnosis of Kawasaki disease in children

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2RdPoBi

Expires October 31, 2019

5. Rate of STIs is rising, and many U.S. teens are sexually active

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2CPuYFW

Expires November 8, 2019

Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder: Diagnosis and Management in Primary Care

CE/CME No: CR-1812

PROGRAM OVERVIEW

Earn credit by reading this article and successfully completing the posttest and evaluation. Successful completion is defined as a cumulative score of at least 70% correct.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

• Understand the epidemiology and underlying pathogenesis of premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD).

• Describe PMDD diagnostic criteria established by DSM-5.

• Differentiate PMDD from other conditions in order to provide appropriate treatment.

• Identify effective evidence-based treatment modalities for PMDD.

• Discuss PMDD treatment challenges and importance of individualizing PMDD treatment.

FACULTY

Jovanka Rajic is a recent graduate of the Master of Science in Nursing–Family Nurse Practitioner program at the Patricia A. Chin School of Nursing at California State University, Los Angeles. Stefanie A. Varela is adjunct faculty in the Patricia A. Chin School of Nursing at California State University, Los Angeles, and practices in the Obstetrics and Gynecology Department at Kaiser Permanente in Ontario, California.

The authors reported no conflicts of interest related to this article.

ACCREDITATION STATEMENT

This program has been reviewed and is approved for a maximum of 1.0 hour of American Academy of Physician Assistants (AAPA) Category 1 CME credit by the Physician Assistant Review Panel. [NPs: Both ANCC and the AANP Certification Program recognize AAPA as an approved provider of Category 1 credit.] Approval is valid through November 30, 2019.

Article begins on next page >>

The severe psychiatric and somatic symptoms of premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) can be debilitating and place women at increased risk for other psychiatric disorders (including major depression and generalized anxiety) and for suicidal ideation. While PMDD’s complex nature makes it an underdiagnosed condition, there are clear diagnostic criteria for clinicians to ensure their patients receive timely and appropriate treatment—thus reducing the risk for serious sequelae.

Premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) is categorized as a depressive disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5).1 The hallmarks of this unique disorder are chronic, severe psychiatric and somatic symptoms that occur only during the late luteal phase of the menstrual cycle and dissipate soon after the onset of menstruation.2 Symptoms are generally disruptive and often associated with significant distress and impaired quality of life.2

PMDD occurs in 3%-8% of women of childbearing age; it affects women worldwide and is not influenced by geography or culture.2 Genetic susceptibility, stress, obesity, and a history of trauma or sexual abuse have been implicated as risk factors.2-6 The impact of PMDD on health-related quality of life is greater than that of chronic back pain but comparable to that of rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis.2,7 Significantly, women with PMDD have a 50%-78% lifetime risk for psychiatric disorders, such as major depressive, dysthymic, seasonal affective, and generalized anxiety disorders, and suicidality.2

PMDD can be challenging for primary care providers to diagnose and treat, due to the lack of standardized screening methods, unfamiliarity with evidence-based practices for diagnosis, and the need to tailor treatment to each patient’s individual needs.3,8 But the increased risk for psychiatric sequelae, including suicidality, make timely diagnosis and treatment of PMDD critical.2,9

PATHOGENESIS

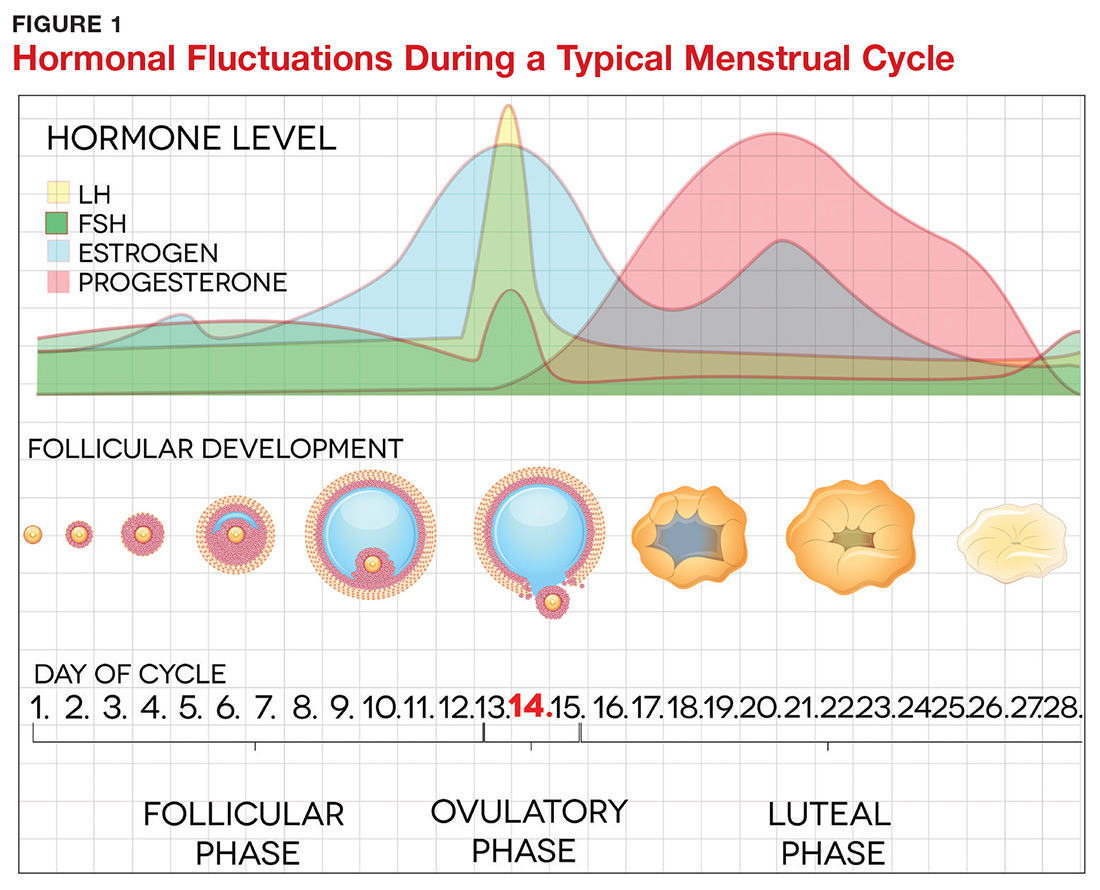

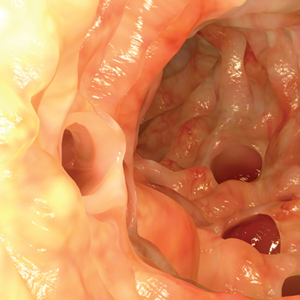

The pathogenesis of PMDD is not completely understood. The prevailing theory is that PMDD is underlined by increased sensitivity to normal fluctuations in ovarian steroid hormone levels (see the Figure) during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle.2-4,6

This sensitivity involves the progesterone metabolite allopregnanolone (ALLO), which acts as a modulator of central GABA-A receptors that have anxiolytic and sedative effects.2,3 It has been postulated that women with PMDD have impaired production of ALLO or decreased sensitivity of GABA-A receptors to ALLO during the luteal phase.2,3 In addition, women with PMDD exhibit a paradoxical anxiety and irritability response to ALLO.2,3 Recent research suggests that PMDD is precipitated by changing ALLO levels during the luteal phase and that treatment directed at reducing ALLO availability during this phase can alleviate PMDD symptoms.10

Hormonal fluctuations have been associated with impaired serotonergic system function in women with PMDD, which results in dysregulation of mood, cognition, sleep, and eating behavior.2-4,6 Hormonal fluctuations have also been implicated in the alteration of emotional and cognitive circuits.2,3,6,11,12 Brain imaging studies have revealed that women with PMDD demonstrate enhanced reactivity to amygdala, which processes emotional and cognitive stimuli, as well as impaired control of amygdala by the prefrontal cortex during the luteal phase.3,7,12

Continue to: PATIENT PRESENTATION/HISTORY

PATIENT PRESENTATION/HISTORY

PMDD is an individual experience for each woman.3,4 However, women with PMDD generally present with a history of various psychiatric and somatic symptoms that significantly interfere with their occupational or social functions (to be discussed in the Diagnosis section, page 42).1-4 The reported symptoms occur in predictable patterns that are associated with the menstrual cycle, intensifying around the time of menstruation and resolving immediately after onset of menstruation in most cases.1-4

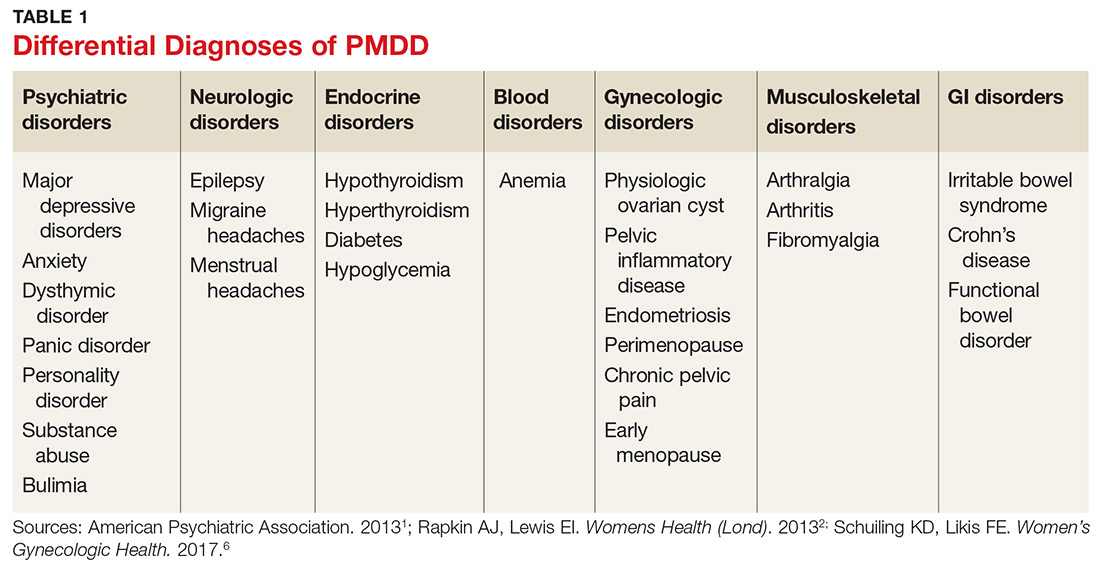

Many psychiatric and medical conditions may be exacerbated during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle and thus may mimic the signs and symptoms of PMDD (see Table 1).1,4 Therefore, the pattern and severity of symptoms should always be considered when differentiating PMDD from other underlying conditions.1,2,4,5

It is also important to distinguish PMDD from PMS, a condition with which it is frequently confused. The latter manifests with at least one affective or somatic symptom that is bothersome but not disabling.4,5 An accurate differential diagnosis is important, as the management of these two conditions differs significantly.4,5

ASSESSMENT

PMDD assessment should include thorough history taking, with emphasis on medical, gynecologic, and psychiatric history as well as social and familial history (including PMDD and other psychiatric disorders); and physical examination, including gynecologic and mental status assessment and depression screening using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9).2,4,13,14 The physical exam is usually unremarkable.14 The most common physical findings during the luteal phase include mild swelling in the lower extremities and breast tenderness.14 Mental status examination, however, may be abnormal during the late luteal phase—albeit with orientation, memory, thoughts, and perceptions intact.13,14

LABORATORY WORKUP

There is no specific laboratory test for PMDD; rather, testing is aimed at ruling out alternative diagnoses.4,14 Relevant studies may include a complete blood count to exclude anemia, a thyroid function test to exclude thyroid disorders, a blood glucose test to exclude diabetes or hypoglycemia, and a ß hCG test to exclude possible pregnancy.4,14 Hormonal tests (eg, for FSH) may be considered for younger women with irregular cycles or for those younger than 40 with suspected premature menopause.4,14

Continue to: DIAGNOSIS

DIAGNOSIS

Diagnosis of PMDD is guided by the DSM-5 criteria, which include the following components

- Content (presence of specific symptoms)

- Cyclicity (premenstrual onset and postmenstrual resolution)

- Severity (significant distress)

- Chronicity (occurrence in the past year).15

DSM-5 has established seven criteria (labeled A-G) for a PMDD diagnosis.1 First and foremost, a woman must experience a minimum of five of the 11 listed symptoms, with a minimum of one symptom being related to mood, during most menstrual cycles over the previous 12 months (Criterion A).1 The symptoms must occur during the week before the onset of menses, must improve within a few days of onset of menses, and must resolve in the week following menses.1

Mood-related symptoms (outlined in Criterion B) include

1. Notable depressed mood, hopelessness, or self-deprecation

2. Notable tension and/or anxiety

3. Notable affective lability (eg, mood swings, sudden sadness, tearfulness, or increased sensitivity to rejection)

4. Notable anger or irritability or increased interpersonal conflicts.1

Somatic or functional symptoms associated with PMDD (Criterion C) include:

5. Low interest in common activities (eg, those related to friends, work, school, and/or hobbies)

6. Difficulty concentrating

7. Lethargy, fatigue, or increased lack of energy

8. Notable change in appetite

9. Insomnia or hypersomnia

10. Feeling overwhelmed or out of control

11. Physical symptoms, such as breast tenderness or swelling, joint or muscle pain, headache, weight gain, or bloating.1

Again, patients must report at least one symptom from Criterion B and at least one from Criterion C—but a minimum of five symptoms overall—to receive a diagnosis of PMDD.1

Continue to: Additionally, the symptoms must...

Additionally, the symptoms must cause clinically significant distress or impair daily functioning, including occupational, social, academic, and sexual activities (Criterion D). They must not represent exacerbation of another underlying psychiatric disorder, such as major depressive, dysthymic, panic, or personality disorders (Criterion E), although PMDD may co-occur with psychiatric disorders.1

The above-mentioned symptom profile must be confirmed by prospective daily ratings of a minimum of two consecutive symptomatic menstrual cycles (Criterion F), although a provisional diagnosis of PMDD may be made prior to confirmation.1 The Daily Record of Severity of Problems is the most widely used instrument for prospective daily rating of PMDD symptoms listed in the DSM-5 criteria.5,15

Finally, the symptoms must not be evoked by the use of a substance (eg, medications, alcohol, and illicit drugs) or another medical condition (Criterion G).1

TREATMENT/MANAGEMENT

The goal of PMDD treatment is to relieve psychiatric and physical symptoms and improve the patient's ability to function.3 Treatment is primarily directed at pharmacologic neuromodulation using selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) or ovulation suppression using oral contraceptives and hormones.2

Pharmacotherapy

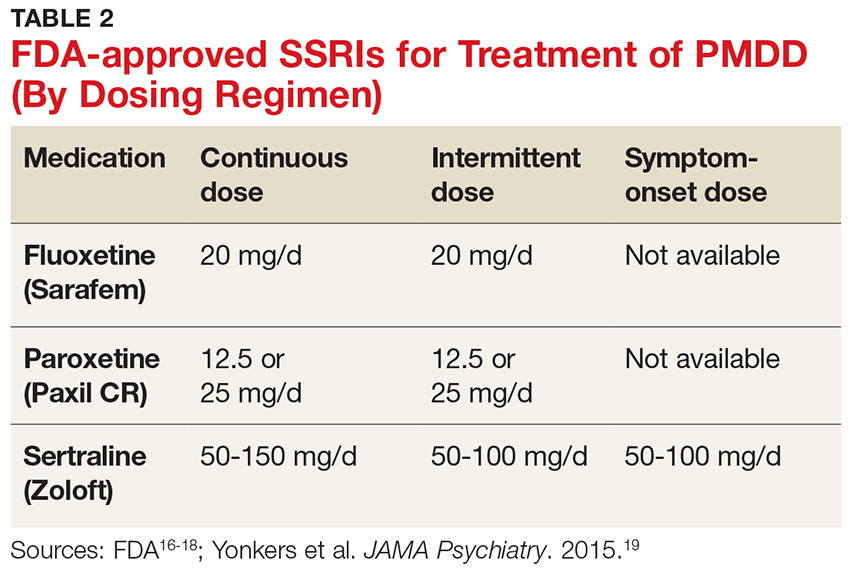

SSRIs are the firstline treatment for PMDD.5 Fluoxetine, paroxetine, and sertraline are the only serotonergic medications approved by the FDA for treatment of PMDD.2 SSRIs act within one to two days when used for PMDD, thereby allowing different modes of dosing.2 SSRI dosing may be continuous (daily administration), intermittent (administration from ovulation to first day of menses), or symptomatic (administration from symptom onset until first day of menses).3 Although data on continuous and intermittent dosing are available for fluoxetine, paroxetine, and sertraline, symptom-onset data are currently available only for sertraline (see Table 2).16-19

Continue to: Combined oral contraceptives...

Combined oral contraceptives (COCs) containing estrogen and progesterone are considered secondline treatment for PMDD—specifically, COCs containing 20 µg of ethinyl estradiol and 3 mg of drospirenone administered as a 24/4 regimen.2,3,5,6 This combination has been approved by the FDA for women with PMDD who seek oral contraception.3 Although drospirenone-containing products have been associated with increased risk for venous thromboembolism (VTE), this risk is lower than that for VTE during pregnancy or in the postpartum period.3 Currently, no strong evidence exists regarding the effectiveness of other oral contraceptives for PMDD.6

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists are the thirdline treatment for PMDD.6 They eliminate symptoms of the luteal phase by suppressing ovarian release of estrogen and ovulation.6 However, use of these agents is not recommended for more than one year due to the increased risk for cardiovascular events.5,6 In addition, long-term users need add-back therapy (adding back small amounts of the hormone) to counteract the effects of low estrogen, such as bone loss; providers should be aware that this may lead to the recurrence of PMDD.3,5,6 The use of estrogen and progesterone formulations for PMDD is currently not strongly supported by research.6

Complementary treatment

Cognitive behavioral therapy has been shown to improve functioning and reduce depression in women with PMDD and may be a useful adjunct.2,20 Regular aerobic exercise, a diet high in protein and complex carbohydrates to increase tryptophan (serotonin precursor) levels, and reduced intake of caffeine, sugar, and alcohol are some commonly recommended lifestyle changes.2

Calcium carbonate supplementation (500 mg/d) has demonstrated effectiveness in alleviating premenstrual mood and physical symptoms.21 There is currently no strong evidence regarding the benefits of acupuncture, Qi therapy, reflexology, and herbal preparations for managing PMDD.22

Surgery

Bilateral oophorectomy, usually with concomitant hysterectomy, is the last resort for women with severe PMDD who do not respond to or cannot tolerate the standard treatments.6 This surgical procedure results in premature menopause, which may lead to complications related to a hypoestrogenic state—including vasomotor symptoms (flushes/flashes), vaginal atrophy, osteopenia, osteoporosis, and cardiovascular disease.2 Therefore, it is important to implement estrogen replacement therapy after surgery until the age of natural menopause is reached.2 If hysterectomy is not performed, the administration of progesterone is necessary to prevent endometrial hyperplasia and therefore reduce the risk for endometrial cancer.2 However, the addition of progesterone may lead to recurrence of symptoms.2

Continue to: Treatment challenges

Treatment challenges

PMDD treatment differs for each patient.3 Severity of symptoms, response to treatment, treatment preference, conception plans, and reproductive age need to be considered.3

Women with prominent depressive or physical symptoms may respond better to continuous dosing of SSRIs, whereas those with prominent irritability, anger, and mood swings may respond better to a symptom-onset SSRI regimen that reduces availability and function of ALLO.3 Women who develop tolerance to SSRIs may need to have their dosage increased or be switched to another medication.3Quetiapine is used as an adjunct to SSRIs for women who do not respond to SSRIs alone and has shown to improve mood swings, anxiety, and irritability.5 However, women experiencing persistent adverse effects of SSRIs, such as sexual dysfunction, may benefit from intermittent dosing.3

Adolescents and women in their early 20s should be treated with OCs or nonpharmacologic modalities due to concerns about SSRI use and increased risk for suicidality in this population.3 The risks related to SSRI use during pregnancy and breastfeeding should be considered and discussed with women of childbearing age who use SSRIs to treat PMDD.3 Perimenopausal women with irregular menses on intermittent SSRIs may have to switch to symptom-onset or continuous dosing due to the difficulty of tracking the menstrual period and lack of significant benchmarks regarding when to start the treatment.3

Patient education/follow-up

Patients should be educated on PMDD etiology, diagnostic process, and available treatment options.4 The importance of prospective record-keeping—for confirmation of the diagnosis and evaluation of individual response to a specific treatment—should be emphasized.4 Patients should be encouraged to follow up with their health care provider to monitor treatment effectiveness, possible adverse effects, and need for treatment adjustment.4

CONCLUSION

The symptoms of PMDD can have a debilitating and life-disrupting impact on affected women—and put them at risk for other serious psychiatric disorders and suicide. The DSM-5 criteria provide diagnostic guidance to help distinguish PMDD from other underlying conditions, ensuring that patients can receive timely and appropriate treatment. While SSRIs are regarded as the most effective option, other evidence-based treatments should be considered, since PMDD requires individualized treatment to ensure optimal clinical outcomes.

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Rapkin AJ, Lewis EI. Treatment of premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Womens Health (Lond). 2013;9(6):537-556.

3. Pearlstein T. Treatment of premenstrual dysphoric disorder: therapeutic challenges. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2016;9(4):493-496.

4. Zielinski R, Lynne S. Menstrual-cycle pain and premenstrual conditions. In: Schuiling KD, Likis FE, eds. Women’s Gynecologic Health. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning; 2017:556-573.

5. Hofmeister S, Bodden S. Premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Am Fam Physician. 2016;94(3):236-240.

6. Yonkers KA, Simoni MK. Premenstrual disorders. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218(1):68-74.

7. Yang M, Wallenstein G, Hagan M, et al. Burden of premenstrual dysphoric disorder on health-related quality of life. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2008;17(1):113-121.

8. Craner JR, Sigmon ST, Women Health.

9. Hong JP, Park S, Wang HR, et al. Prevalence, correlates, comorbidities, and suicidal tendencies of premenstrual dysphoric disorder in a nationwide sample of Korean women. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2012;47(12): 1937-1945.

10. Martinez PE, Rubinow PR, Nieman LK, et al. 5α-reductase inhibition prevents the luteal phase increase in plasma allopregnanolone levels and mitigates symptoms in women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2016;41:1093-1102.

11. Baller EB, Wei SM, Kohn PD. Abnormalities of dorsolateral prefrontal function in women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder: A multimodal neuroimaging study. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(3):305-314.

. EINeuroimaging the menstrual cycle and premenstrual dysphoric disorderCurr Psychiatry Rep.201577

13. Reid RL. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder (formerly premenstrual syndrome) [Updated Jan 23, 2017]. In: De Groot LJ, Chrousos G, Dungan K, et al, eds. Endotext [Internet]. South Dartmouth, MA: MDText.com, Inc; 2000.

14. Htay TT. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder clinical presentation. Medscape. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/293257-clinical#b3. Updated February 16, 2016. Accessed February 7, 2018.

15. Epperson CN, Hantsoo LV. Making strides to simplify diagnosis of premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174(1):6-7.

16. FDA. Sarafem. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2006/021860lbl.pdf. Accessed February 15, 2018.

17. FDA. Paxil CR. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2004/20936se2-013_paxil_lbl.pdf. Accessed February 15, 2018.

18. FDA. Zoloft. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2016/019839s74s86s87_20990s35s44s45lbl.pdf. Accessed February 15, 2018.

19. Yonkers KA, Kornstein SG, Gueorguieva R, et al. Symptom-onset dosing of sertraline for the treatment of premenstrual dysphoric disorder: a randomized trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(10):1037-1044.

20. Busse JW, Montori VM, Krasnik C, et al. Psychological intervention for premenstrual syndrome: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Psychother Psychosom. 2009;78(1):6-15.

21. Shobeiri F, Araste FE, Ebrahimi R, et al. Effect of calcium on premenstrual syndrome: a double-blind randomized clinical trial. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2017;60(1):100-105.

22. Nevatte T, O’Brien PMS, Bäckström T, et al. ISPMD consensus on the management of premenstrual disorders. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2013;16(4):279-291.

CE/CME No: CR-1812

PROGRAM OVERVIEW

Earn credit by reading this article and successfully completing the posttest and evaluation. Successful completion is defined as a cumulative score of at least 70% correct.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

• Understand the epidemiology and underlying pathogenesis of premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD).

• Describe PMDD diagnostic criteria established by DSM-5.

• Differentiate PMDD from other conditions in order to provide appropriate treatment.

• Identify effective evidence-based treatment modalities for PMDD.

• Discuss PMDD treatment challenges and importance of individualizing PMDD treatment.

FACULTY

Jovanka Rajic is a recent graduate of the Master of Science in Nursing–Family Nurse Practitioner program at the Patricia A. Chin School of Nursing at California State University, Los Angeles. Stefanie A. Varela is adjunct faculty in the Patricia A. Chin School of Nursing at California State University, Los Angeles, and practices in the Obstetrics and Gynecology Department at Kaiser Permanente in Ontario, California.

The authors reported no conflicts of interest related to this article.

ACCREDITATION STATEMENT

This program has been reviewed and is approved for a maximum of 1.0 hour of American Academy of Physician Assistants (AAPA) Category 1 CME credit by the Physician Assistant Review Panel. [NPs: Both ANCC and the AANP Certification Program recognize AAPA as an approved provider of Category 1 credit.] Approval is valid through November 30, 2019.

Article begins on next page >>

The severe psychiatric and somatic symptoms of premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) can be debilitating and place women at increased risk for other psychiatric disorders (including major depression and generalized anxiety) and for suicidal ideation. While PMDD’s complex nature makes it an underdiagnosed condition, there are clear diagnostic criteria for clinicians to ensure their patients receive timely and appropriate treatment—thus reducing the risk for serious sequelae.

Premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) is categorized as a depressive disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5).1 The hallmarks of this unique disorder are chronic, severe psychiatric and somatic symptoms that occur only during the late luteal phase of the menstrual cycle and dissipate soon after the onset of menstruation.2 Symptoms are generally disruptive and often associated with significant distress and impaired quality of life.2

PMDD occurs in 3%-8% of women of childbearing age; it affects women worldwide and is not influenced by geography or culture.2 Genetic susceptibility, stress, obesity, and a history of trauma or sexual abuse have been implicated as risk factors.2-6 The impact of PMDD on health-related quality of life is greater than that of chronic back pain but comparable to that of rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis.2,7 Significantly, women with PMDD have a 50%-78% lifetime risk for psychiatric disorders, such as major depressive, dysthymic, seasonal affective, and generalized anxiety disorders, and suicidality.2

PMDD can be challenging for primary care providers to diagnose and treat, due to the lack of standardized screening methods, unfamiliarity with evidence-based practices for diagnosis, and the need to tailor treatment to each patient’s individual needs.3,8 But the increased risk for psychiatric sequelae, including suicidality, make timely diagnosis and treatment of PMDD critical.2,9

PATHOGENESIS

The pathogenesis of PMDD is not completely understood. The prevailing theory is that PMDD is underlined by increased sensitivity to normal fluctuations in ovarian steroid hormone levels (see the Figure) during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle.2-4,6

This sensitivity involves the progesterone metabolite allopregnanolone (ALLO), which acts as a modulator of central GABA-A receptors that have anxiolytic and sedative effects.2,3 It has been postulated that women with PMDD have impaired production of ALLO or decreased sensitivity of GABA-A receptors to ALLO during the luteal phase.2,3 In addition, women with PMDD exhibit a paradoxical anxiety and irritability response to ALLO.2,3 Recent research suggests that PMDD is precipitated by changing ALLO levels during the luteal phase and that treatment directed at reducing ALLO availability during this phase can alleviate PMDD symptoms.10

Hormonal fluctuations have been associated with impaired serotonergic system function in women with PMDD, which results in dysregulation of mood, cognition, sleep, and eating behavior.2-4,6 Hormonal fluctuations have also been implicated in the alteration of emotional and cognitive circuits.2,3,6,11,12 Brain imaging studies have revealed that women with PMDD demonstrate enhanced reactivity to amygdala, which processes emotional and cognitive stimuli, as well as impaired control of amygdala by the prefrontal cortex during the luteal phase.3,7,12

Continue to: PATIENT PRESENTATION/HISTORY

PATIENT PRESENTATION/HISTORY

PMDD is an individual experience for each woman.3,4 However, women with PMDD generally present with a history of various psychiatric and somatic symptoms that significantly interfere with their occupational or social functions (to be discussed in the Diagnosis section, page 42).1-4 The reported symptoms occur in predictable patterns that are associated with the menstrual cycle, intensifying around the time of menstruation and resolving immediately after onset of menstruation in most cases.1-4

Many psychiatric and medical conditions may be exacerbated during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle and thus may mimic the signs and symptoms of PMDD (see Table 1).1,4 Therefore, the pattern and severity of symptoms should always be considered when differentiating PMDD from other underlying conditions.1,2,4,5

It is also important to distinguish PMDD from PMS, a condition with which it is frequently confused. The latter manifests with at least one affective or somatic symptom that is bothersome but not disabling.4,5 An accurate differential diagnosis is important, as the management of these two conditions differs significantly.4,5

ASSESSMENT

PMDD assessment should include thorough history taking, with emphasis on medical, gynecologic, and psychiatric history as well as social and familial history (including PMDD and other psychiatric disorders); and physical examination, including gynecologic and mental status assessment and depression screening using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9).2,4,13,14 The physical exam is usually unremarkable.14 The most common physical findings during the luteal phase include mild swelling in the lower extremities and breast tenderness.14 Mental status examination, however, may be abnormal during the late luteal phase—albeit with orientation, memory, thoughts, and perceptions intact.13,14

LABORATORY WORKUP

There is no specific laboratory test for PMDD; rather, testing is aimed at ruling out alternative diagnoses.4,14 Relevant studies may include a complete blood count to exclude anemia, a thyroid function test to exclude thyroid disorders, a blood glucose test to exclude diabetes or hypoglycemia, and a ß hCG test to exclude possible pregnancy.4,14 Hormonal tests (eg, for FSH) may be considered for younger women with irregular cycles or for those younger than 40 with suspected premature menopause.4,14

Continue to: DIAGNOSIS

DIAGNOSIS

Diagnosis of PMDD is guided by the DSM-5 criteria, which include the following components

- Content (presence of specific symptoms)

- Cyclicity (premenstrual onset and postmenstrual resolution)

- Severity (significant distress)

- Chronicity (occurrence in the past year).15

DSM-5 has established seven criteria (labeled A-G) for a PMDD diagnosis.1 First and foremost, a woman must experience a minimum of five of the 11 listed symptoms, with a minimum of one symptom being related to mood, during most menstrual cycles over the previous 12 months (Criterion A).1 The symptoms must occur during the week before the onset of menses, must improve within a few days of onset of menses, and must resolve in the week following menses.1

Mood-related symptoms (outlined in Criterion B) include

1. Notable depressed mood, hopelessness, or self-deprecation

2. Notable tension and/or anxiety

3. Notable affective lability (eg, mood swings, sudden sadness, tearfulness, or increased sensitivity to rejection)

4. Notable anger or irritability or increased interpersonal conflicts.1

Somatic or functional symptoms associated with PMDD (Criterion C) include:

5. Low interest in common activities (eg, those related to friends, work, school, and/or hobbies)

6. Difficulty concentrating

7. Lethargy, fatigue, or increased lack of energy

8. Notable change in appetite

9. Insomnia or hypersomnia

10. Feeling overwhelmed or out of control

11. Physical symptoms, such as breast tenderness or swelling, joint or muscle pain, headache, weight gain, or bloating.1

Again, patients must report at least one symptom from Criterion B and at least one from Criterion C—but a minimum of five symptoms overall—to receive a diagnosis of PMDD.1

Continue to: Additionally, the symptoms must...

Additionally, the symptoms must cause clinically significant distress or impair daily functioning, including occupational, social, academic, and sexual activities (Criterion D). They must not represent exacerbation of another underlying psychiatric disorder, such as major depressive, dysthymic, panic, or personality disorders (Criterion E), although PMDD may co-occur with psychiatric disorders.1

The above-mentioned symptom profile must be confirmed by prospective daily ratings of a minimum of two consecutive symptomatic menstrual cycles (Criterion F), although a provisional diagnosis of PMDD may be made prior to confirmation.1 The Daily Record of Severity of Problems is the most widely used instrument for prospective daily rating of PMDD symptoms listed in the DSM-5 criteria.5,15

Finally, the symptoms must not be evoked by the use of a substance (eg, medications, alcohol, and illicit drugs) or another medical condition (Criterion G).1

TREATMENT/MANAGEMENT

The goal of PMDD treatment is to relieve psychiatric and physical symptoms and improve the patient's ability to function.3 Treatment is primarily directed at pharmacologic neuromodulation using selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) or ovulation suppression using oral contraceptives and hormones.2

Pharmacotherapy

SSRIs are the firstline treatment for PMDD.5 Fluoxetine, paroxetine, and sertraline are the only serotonergic medications approved by the FDA for treatment of PMDD.2 SSRIs act within one to two days when used for PMDD, thereby allowing different modes of dosing.2 SSRI dosing may be continuous (daily administration), intermittent (administration from ovulation to first day of menses), or symptomatic (administration from symptom onset until first day of menses).3 Although data on continuous and intermittent dosing are available for fluoxetine, paroxetine, and sertraline, symptom-onset data are currently available only for sertraline (see Table 2).16-19

Continue to: Combined oral contraceptives...

Combined oral contraceptives (COCs) containing estrogen and progesterone are considered secondline treatment for PMDD—specifically, COCs containing 20 µg of ethinyl estradiol and 3 mg of drospirenone administered as a 24/4 regimen.2,3,5,6 This combination has been approved by the FDA for women with PMDD who seek oral contraception.3 Although drospirenone-containing products have been associated with increased risk for venous thromboembolism (VTE), this risk is lower than that for VTE during pregnancy or in the postpartum period.3 Currently, no strong evidence exists regarding the effectiveness of other oral contraceptives for PMDD.6

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists are the thirdline treatment for PMDD.6 They eliminate symptoms of the luteal phase by suppressing ovarian release of estrogen and ovulation.6 However, use of these agents is not recommended for more than one year due to the increased risk for cardiovascular events.5,6 In addition, long-term users need add-back therapy (adding back small amounts of the hormone) to counteract the effects of low estrogen, such as bone loss; providers should be aware that this may lead to the recurrence of PMDD.3,5,6 The use of estrogen and progesterone formulations for PMDD is currently not strongly supported by research.6

Complementary treatment

Cognitive behavioral therapy has been shown to improve functioning and reduce depression in women with PMDD and may be a useful adjunct.2,20 Regular aerobic exercise, a diet high in protein and complex carbohydrates to increase tryptophan (serotonin precursor) levels, and reduced intake of caffeine, sugar, and alcohol are some commonly recommended lifestyle changes.2

Calcium carbonate supplementation (500 mg/d) has demonstrated effectiveness in alleviating premenstrual mood and physical symptoms.21 There is currently no strong evidence regarding the benefits of acupuncture, Qi therapy, reflexology, and herbal preparations for managing PMDD.22

Surgery

Bilateral oophorectomy, usually with concomitant hysterectomy, is the last resort for women with severe PMDD who do not respond to or cannot tolerate the standard treatments.6 This surgical procedure results in premature menopause, which may lead to complications related to a hypoestrogenic state—including vasomotor symptoms (flushes/flashes), vaginal atrophy, osteopenia, osteoporosis, and cardiovascular disease.2 Therefore, it is important to implement estrogen replacement therapy after surgery until the age of natural menopause is reached.2 If hysterectomy is not performed, the administration of progesterone is necessary to prevent endometrial hyperplasia and therefore reduce the risk for endometrial cancer.2 However, the addition of progesterone may lead to recurrence of symptoms.2

Continue to: Treatment challenges

Treatment challenges

PMDD treatment differs for each patient.3 Severity of symptoms, response to treatment, treatment preference, conception plans, and reproductive age need to be considered.3

Women with prominent depressive or physical symptoms may respond better to continuous dosing of SSRIs, whereas those with prominent irritability, anger, and mood swings may respond better to a symptom-onset SSRI regimen that reduces availability and function of ALLO.3 Women who develop tolerance to SSRIs may need to have their dosage increased or be switched to another medication.3Quetiapine is used as an adjunct to SSRIs for women who do not respond to SSRIs alone and has shown to improve mood swings, anxiety, and irritability.5 However, women experiencing persistent adverse effects of SSRIs, such as sexual dysfunction, may benefit from intermittent dosing.3

Adolescents and women in their early 20s should be treated with OCs or nonpharmacologic modalities due to concerns about SSRI use and increased risk for suicidality in this population.3 The risks related to SSRI use during pregnancy and breastfeeding should be considered and discussed with women of childbearing age who use SSRIs to treat PMDD.3 Perimenopausal women with irregular menses on intermittent SSRIs may have to switch to symptom-onset or continuous dosing due to the difficulty of tracking the menstrual period and lack of significant benchmarks regarding when to start the treatment.3

Patient education/follow-up

Patients should be educated on PMDD etiology, diagnostic process, and available treatment options.4 The importance of prospective record-keeping—for confirmation of the diagnosis and evaluation of individual response to a specific treatment—should be emphasized.4 Patients should be encouraged to follow up with their health care provider to monitor treatment effectiveness, possible adverse effects, and need for treatment adjustment.4

CONCLUSION

The symptoms of PMDD can have a debilitating and life-disrupting impact on affected women—and put them at risk for other serious psychiatric disorders and suicide. The DSM-5 criteria provide diagnostic guidance to help distinguish PMDD from other underlying conditions, ensuring that patients can receive timely and appropriate treatment. While SSRIs are regarded as the most effective option, other evidence-based treatments should be considered, since PMDD requires individualized treatment to ensure optimal clinical outcomes.

CE/CME No: CR-1812

PROGRAM OVERVIEW

Earn credit by reading this article and successfully completing the posttest and evaluation. Successful completion is defined as a cumulative score of at least 70% correct.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

• Understand the epidemiology and underlying pathogenesis of premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD).

• Describe PMDD diagnostic criteria established by DSM-5.

• Differentiate PMDD from other conditions in order to provide appropriate treatment.

• Identify effective evidence-based treatment modalities for PMDD.

• Discuss PMDD treatment challenges and importance of individualizing PMDD treatment.

FACULTY

Jovanka Rajic is a recent graduate of the Master of Science in Nursing–Family Nurse Practitioner program at the Patricia A. Chin School of Nursing at California State University, Los Angeles. Stefanie A. Varela is adjunct faculty in the Patricia A. Chin School of Nursing at California State University, Los Angeles, and practices in the Obstetrics and Gynecology Department at Kaiser Permanente in Ontario, California.

The authors reported no conflicts of interest related to this article.

ACCREDITATION STATEMENT

This program has been reviewed and is approved for a maximum of 1.0 hour of American Academy of Physician Assistants (AAPA) Category 1 CME credit by the Physician Assistant Review Panel. [NPs: Both ANCC and the AANP Certification Program recognize AAPA as an approved provider of Category 1 credit.] Approval is valid through November 30, 2019.

Article begins on next page >>

The severe psychiatric and somatic symptoms of premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) can be debilitating and place women at increased risk for other psychiatric disorders (including major depression and generalized anxiety) and for suicidal ideation. While PMDD’s complex nature makes it an underdiagnosed condition, there are clear diagnostic criteria for clinicians to ensure their patients receive timely and appropriate treatment—thus reducing the risk for serious sequelae.

Premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) is categorized as a depressive disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5).1 The hallmarks of this unique disorder are chronic, severe psychiatric and somatic symptoms that occur only during the late luteal phase of the menstrual cycle and dissipate soon after the onset of menstruation.2 Symptoms are generally disruptive and often associated with significant distress and impaired quality of life.2

PMDD occurs in 3%-8% of women of childbearing age; it affects women worldwide and is not influenced by geography or culture.2 Genetic susceptibility, stress, obesity, and a history of trauma or sexual abuse have been implicated as risk factors.2-6 The impact of PMDD on health-related quality of life is greater than that of chronic back pain but comparable to that of rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis.2,7 Significantly, women with PMDD have a 50%-78% lifetime risk for psychiatric disorders, such as major depressive, dysthymic, seasonal affective, and generalized anxiety disorders, and suicidality.2

PMDD can be challenging for primary care providers to diagnose and treat, due to the lack of standardized screening methods, unfamiliarity with evidence-based practices for diagnosis, and the need to tailor treatment to each patient’s individual needs.3,8 But the increased risk for psychiatric sequelae, including suicidality, make timely diagnosis and treatment of PMDD critical.2,9

PATHOGENESIS

The pathogenesis of PMDD is not completely understood. The prevailing theory is that PMDD is underlined by increased sensitivity to normal fluctuations in ovarian steroid hormone levels (see the Figure) during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle.2-4,6

This sensitivity involves the progesterone metabolite allopregnanolone (ALLO), which acts as a modulator of central GABA-A receptors that have anxiolytic and sedative effects.2,3 It has been postulated that women with PMDD have impaired production of ALLO or decreased sensitivity of GABA-A receptors to ALLO during the luteal phase.2,3 In addition, women with PMDD exhibit a paradoxical anxiety and irritability response to ALLO.2,3 Recent research suggests that PMDD is precipitated by changing ALLO levels during the luteal phase and that treatment directed at reducing ALLO availability during this phase can alleviate PMDD symptoms.10

Hormonal fluctuations have been associated with impaired serotonergic system function in women with PMDD, which results in dysregulation of mood, cognition, sleep, and eating behavior.2-4,6 Hormonal fluctuations have also been implicated in the alteration of emotional and cognitive circuits.2,3,6,11,12 Brain imaging studies have revealed that women with PMDD demonstrate enhanced reactivity to amygdala, which processes emotional and cognitive stimuli, as well as impaired control of amygdala by the prefrontal cortex during the luteal phase.3,7,12

Continue to: PATIENT PRESENTATION/HISTORY

PATIENT PRESENTATION/HISTORY

PMDD is an individual experience for each woman.3,4 However, women with PMDD generally present with a history of various psychiatric and somatic symptoms that significantly interfere with their occupational or social functions (to be discussed in the Diagnosis section, page 42).1-4 The reported symptoms occur in predictable patterns that are associated with the menstrual cycle, intensifying around the time of menstruation and resolving immediately after onset of menstruation in most cases.1-4

Many psychiatric and medical conditions may be exacerbated during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle and thus may mimic the signs and symptoms of PMDD (see Table 1).1,4 Therefore, the pattern and severity of symptoms should always be considered when differentiating PMDD from other underlying conditions.1,2,4,5

It is also important to distinguish PMDD from PMS, a condition with which it is frequently confused. The latter manifests with at least one affective or somatic symptom that is bothersome but not disabling.4,5 An accurate differential diagnosis is important, as the management of these two conditions differs significantly.4,5

ASSESSMENT

PMDD assessment should include thorough history taking, with emphasis on medical, gynecologic, and psychiatric history as well as social and familial history (including PMDD and other psychiatric disorders); and physical examination, including gynecologic and mental status assessment and depression screening using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9).2,4,13,14 The physical exam is usually unremarkable.14 The most common physical findings during the luteal phase include mild swelling in the lower extremities and breast tenderness.14 Mental status examination, however, may be abnormal during the late luteal phase—albeit with orientation, memory, thoughts, and perceptions intact.13,14

LABORATORY WORKUP

There is no specific laboratory test for PMDD; rather, testing is aimed at ruling out alternative diagnoses.4,14 Relevant studies may include a complete blood count to exclude anemia, a thyroid function test to exclude thyroid disorders, a blood glucose test to exclude diabetes or hypoglycemia, and a ß hCG test to exclude possible pregnancy.4,14 Hormonal tests (eg, for FSH) may be considered for younger women with irregular cycles or for those younger than 40 with suspected premature menopause.4,14

Continue to: DIAGNOSIS

DIAGNOSIS

Diagnosis of PMDD is guided by the DSM-5 criteria, which include the following components

- Content (presence of specific symptoms)

- Cyclicity (premenstrual onset and postmenstrual resolution)

- Severity (significant distress)

- Chronicity (occurrence in the past year).15

DSM-5 has established seven criteria (labeled A-G) for a PMDD diagnosis.1 First and foremost, a woman must experience a minimum of five of the 11 listed symptoms, with a minimum of one symptom being related to mood, during most menstrual cycles over the previous 12 months (Criterion A).1 The symptoms must occur during the week before the onset of menses, must improve within a few days of onset of menses, and must resolve in the week following menses.1

Mood-related symptoms (outlined in Criterion B) include

1. Notable depressed mood, hopelessness, or self-deprecation

2. Notable tension and/or anxiety

3. Notable affective lability (eg, mood swings, sudden sadness, tearfulness, or increased sensitivity to rejection)

4. Notable anger or irritability or increased interpersonal conflicts.1

Somatic or functional symptoms associated with PMDD (Criterion C) include:

5. Low interest in common activities (eg, those related to friends, work, school, and/or hobbies)

6. Difficulty concentrating

7. Lethargy, fatigue, or increased lack of energy

8. Notable change in appetite

9. Insomnia or hypersomnia

10. Feeling overwhelmed or out of control

11. Physical symptoms, such as breast tenderness or swelling, joint or muscle pain, headache, weight gain, or bloating.1

Again, patients must report at least one symptom from Criterion B and at least one from Criterion C—but a minimum of five symptoms overall—to receive a diagnosis of PMDD.1

Continue to: Additionally, the symptoms must...

Additionally, the symptoms must cause clinically significant distress or impair daily functioning, including occupational, social, academic, and sexual activities (Criterion D). They must not represent exacerbation of another underlying psychiatric disorder, such as major depressive, dysthymic, panic, or personality disorders (Criterion E), although PMDD may co-occur with psychiatric disorders.1

The above-mentioned symptom profile must be confirmed by prospective daily ratings of a minimum of two consecutive symptomatic menstrual cycles (Criterion F), although a provisional diagnosis of PMDD may be made prior to confirmation.1 The Daily Record of Severity of Problems is the most widely used instrument for prospective daily rating of PMDD symptoms listed in the DSM-5 criteria.5,15

Finally, the symptoms must not be evoked by the use of a substance (eg, medications, alcohol, and illicit drugs) or another medical condition (Criterion G).1

TREATMENT/MANAGEMENT

The goal of PMDD treatment is to relieve psychiatric and physical symptoms and improve the patient's ability to function.3 Treatment is primarily directed at pharmacologic neuromodulation using selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) or ovulation suppression using oral contraceptives and hormones.2

Pharmacotherapy

SSRIs are the firstline treatment for PMDD.5 Fluoxetine, paroxetine, and sertraline are the only serotonergic medications approved by the FDA for treatment of PMDD.2 SSRIs act within one to two days when used for PMDD, thereby allowing different modes of dosing.2 SSRI dosing may be continuous (daily administration), intermittent (administration from ovulation to first day of menses), or symptomatic (administration from symptom onset until first day of menses).3 Although data on continuous and intermittent dosing are available for fluoxetine, paroxetine, and sertraline, symptom-onset data are currently available only for sertraline (see Table 2).16-19

Continue to: Combined oral contraceptives...

Combined oral contraceptives (COCs) containing estrogen and progesterone are considered secondline treatment for PMDD—specifically, COCs containing 20 µg of ethinyl estradiol and 3 mg of drospirenone administered as a 24/4 regimen.2,3,5,6 This combination has been approved by the FDA for women with PMDD who seek oral contraception.3 Although drospirenone-containing products have been associated with increased risk for venous thromboembolism (VTE), this risk is lower than that for VTE during pregnancy or in the postpartum period.3 Currently, no strong evidence exists regarding the effectiveness of other oral contraceptives for PMDD.6

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists are the thirdline treatment for PMDD.6 They eliminate symptoms of the luteal phase by suppressing ovarian release of estrogen and ovulation.6 However, use of these agents is not recommended for more than one year due to the increased risk for cardiovascular events.5,6 In addition, long-term users need add-back therapy (adding back small amounts of the hormone) to counteract the effects of low estrogen, such as bone loss; providers should be aware that this may lead to the recurrence of PMDD.3,5,6 The use of estrogen and progesterone formulations for PMDD is currently not strongly supported by research.6

Complementary treatment

Cognitive behavioral therapy has been shown to improve functioning and reduce depression in women with PMDD and may be a useful adjunct.2,20 Regular aerobic exercise, a diet high in protein and complex carbohydrates to increase tryptophan (serotonin precursor) levels, and reduced intake of caffeine, sugar, and alcohol are some commonly recommended lifestyle changes.2

Calcium carbonate supplementation (500 mg/d) has demonstrated effectiveness in alleviating premenstrual mood and physical symptoms.21 There is currently no strong evidence regarding the benefits of acupuncture, Qi therapy, reflexology, and herbal preparations for managing PMDD.22

Surgery

Bilateral oophorectomy, usually with concomitant hysterectomy, is the last resort for women with severe PMDD who do not respond to or cannot tolerate the standard treatments.6 This surgical procedure results in premature menopause, which may lead to complications related to a hypoestrogenic state—including vasomotor symptoms (flushes/flashes), vaginal atrophy, osteopenia, osteoporosis, and cardiovascular disease.2 Therefore, it is important to implement estrogen replacement therapy after surgery until the age of natural menopause is reached.2 If hysterectomy is not performed, the administration of progesterone is necessary to prevent endometrial hyperplasia and therefore reduce the risk for endometrial cancer.2 However, the addition of progesterone may lead to recurrence of symptoms.2

Continue to: Treatment challenges

Treatment challenges

PMDD treatment differs for each patient.3 Severity of symptoms, response to treatment, treatment preference, conception plans, and reproductive age need to be considered.3

Women with prominent depressive or physical symptoms may respond better to continuous dosing of SSRIs, whereas those with prominent irritability, anger, and mood swings may respond better to a symptom-onset SSRI regimen that reduces availability and function of ALLO.3 Women who develop tolerance to SSRIs may need to have their dosage increased or be switched to another medication.3Quetiapine is used as an adjunct to SSRIs for women who do not respond to SSRIs alone and has shown to improve mood swings, anxiety, and irritability.5 However, women experiencing persistent adverse effects of SSRIs, such as sexual dysfunction, may benefit from intermittent dosing.3

Adolescents and women in their early 20s should be treated with OCs or nonpharmacologic modalities due to concerns about SSRI use and increased risk for suicidality in this population.3 The risks related to SSRI use during pregnancy and breastfeeding should be considered and discussed with women of childbearing age who use SSRIs to treat PMDD.3 Perimenopausal women with irregular menses on intermittent SSRIs may have to switch to symptom-onset or continuous dosing due to the difficulty of tracking the menstrual period and lack of significant benchmarks regarding when to start the treatment.3

Patient education/follow-up

Patients should be educated on PMDD etiology, diagnostic process, and available treatment options.4 The importance of prospective record-keeping—for confirmation of the diagnosis and evaluation of individual response to a specific treatment—should be emphasized.4 Patients should be encouraged to follow up with their health care provider to monitor treatment effectiveness, possible adverse effects, and need for treatment adjustment.4

CONCLUSION

The symptoms of PMDD can have a debilitating and life-disrupting impact on affected women—and put them at risk for other serious psychiatric disorders and suicide. The DSM-5 criteria provide diagnostic guidance to help distinguish PMDD from other underlying conditions, ensuring that patients can receive timely and appropriate treatment. While SSRIs are regarded as the most effective option, other evidence-based treatments should be considered, since PMDD requires individualized treatment to ensure optimal clinical outcomes.

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Rapkin AJ, Lewis EI. Treatment of premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Womens Health (Lond). 2013;9(6):537-556.

3. Pearlstein T. Treatment of premenstrual dysphoric disorder: therapeutic challenges. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2016;9(4):493-496.

4. Zielinski R, Lynne S. Menstrual-cycle pain and premenstrual conditions. In: Schuiling KD, Likis FE, eds. Women’s Gynecologic Health. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning; 2017:556-573.

5. Hofmeister S, Bodden S. Premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Am Fam Physician. 2016;94(3):236-240.

6. Yonkers KA, Simoni MK. Premenstrual disorders. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218(1):68-74.

7. Yang M, Wallenstein G, Hagan M, et al. Burden of premenstrual dysphoric disorder on health-related quality of life. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2008;17(1):113-121.

8. Craner JR, Sigmon ST, Women Health.

9. Hong JP, Park S, Wang HR, et al. Prevalence, correlates, comorbidities, and suicidal tendencies of premenstrual dysphoric disorder in a nationwide sample of Korean women. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2012;47(12): 1937-1945.

10. Martinez PE, Rubinow PR, Nieman LK, et al. 5α-reductase inhibition prevents the luteal phase increase in plasma allopregnanolone levels and mitigates symptoms in women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2016;41:1093-1102.

11. Baller EB, Wei SM, Kohn PD. Abnormalities of dorsolateral prefrontal function in women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder: A multimodal neuroimaging study. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(3):305-314.

. EINeuroimaging the menstrual cycle and premenstrual dysphoric disorderCurr Psychiatry Rep.201577

13. Reid RL. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder (formerly premenstrual syndrome) [Updated Jan 23, 2017]. In: De Groot LJ, Chrousos G, Dungan K, et al, eds. Endotext [Internet]. South Dartmouth, MA: MDText.com, Inc; 2000.

14. Htay TT. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder clinical presentation. Medscape. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/293257-clinical#b3. Updated February 16, 2016. Accessed February 7, 2018.

15. Epperson CN, Hantsoo LV. Making strides to simplify diagnosis of premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174(1):6-7.

16. FDA. Sarafem. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2006/021860lbl.pdf. Accessed February 15, 2018.

17. FDA. Paxil CR. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2004/20936se2-013_paxil_lbl.pdf. Accessed February 15, 2018.

18. FDA. Zoloft. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2016/019839s74s86s87_20990s35s44s45lbl.pdf. Accessed February 15, 2018.

19. Yonkers KA, Kornstein SG, Gueorguieva R, et al. Symptom-onset dosing of sertraline for the treatment of premenstrual dysphoric disorder: a randomized trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(10):1037-1044.

20. Busse JW, Montori VM, Krasnik C, et al. Psychological intervention for premenstrual syndrome: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Psychother Psychosom. 2009;78(1):6-15.

21. Shobeiri F, Araste FE, Ebrahimi R, et al. Effect of calcium on premenstrual syndrome: a double-blind randomized clinical trial. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2017;60(1):100-105.

22. Nevatte T, O’Brien PMS, Bäckström T, et al. ISPMD consensus on the management of premenstrual disorders. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2013;16(4):279-291.

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Rapkin AJ, Lewis EI. Treatment of premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Womens Health (Lond). 2013;9(6):537-556.

3. Pearlstein T. Treatment of premenstrual dysphoric disorder: therapeutic challenges. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2016;9(4):493-496.

4. Zielinski R, Lynne S. Menstrual-cycle pain and premenstrual conditions. In: Schuiling KD, Likis FE, eds. Women’s Gynecologic Health. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning; 2017:556-573.

5. Hofmeister S, Bodden S. Premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Am Fam Physician. 2016;94(3):236-240.

6. Yonkers KA, Simoni MK. Premenstrual disorders. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218(1):68-74.

7. Yang M, Wallenstein G, Hagan M, et al. Burden of premenstrual dysphoric disorder on health-related quality of life. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2008;17(1):113-121.

8. Craner JR, Sigmon ST, Women Health.

9. Hong JP, Park S, Wang HR, et al. Prevalence, correlates, comorbidities, and suicidal tendencies of premenstrual dysphoric disorder in a nationwide sample of Korean women. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2012;47(12): 1937-1945.

10. Martinez PE, Rubinow PR, Nieman LK, et al. 5α-reductase inhibition prevents the luteal phase increase in plasma allopregnanolone levels and mitigates symptoms in women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2016;41:1093-1102.

11. Baller EB, Wei SM, Kohn PD. Abnormalities of dorsolateral prefrontal function in women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder: A multimodal neuroimaging study. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(3):305-314.

. EINeuroimaging the menstrual cycle and premenstrual dysphoric disorderCurr Psychiatry Rep.201577

13. Reid RL. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder (formerly premenstrual syndrome) [Updated Jan 23, 2017]. In: De Groot LJ, Chrousos G, Dungan K, et al, eds. Endotext [Internet]. South Dartmouth, MA: MDText.com, Inc; 2000.

14. Htay TT. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder clinical presentation. Medscape. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/293257-clinical#b3. Updated February 16, 2016. Accessed February 7, 2018.

15. Epperson CN, Hantsoo LV. Making strides to simplify diagnosis of premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174(1):6-7.

16. FDA. Sarafem. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2006/021860lbl.pdf. Accessed February 15, 2018.

17. FDA. Paxil CR. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2004/20936se2-013_paxil_lbl.pdf. Accessed February 15, 2018.

18. FDA. Zoloft. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2016/019839s74s86s87_20990s35s44s45lbl.pdf. Accessed February 15, 2018.

19. Yonkers KA, Kornstein SG, Gueorguieva R, et al. Symptom-onset dosing of sertraline for the treatment of premenstrual dysphoric disorder: a randomized trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(10):1037-1044.

20. Busse JW, Montori VM, Krasnik C, et al. Psychological intervention for premenstrual syndrome: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Psychother Psychosom. 2009;78(1):6-15.

21. Shobeiri F, Araste FE, Ebrahimi R, et al. Effect of calcium on premenstrual syndrome: a double-blind randomized clinical trial. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2017;60(1):100-105.

22. Nevatte T, O’Brien PMS, Bäckström T, et al. ISPMD consensus on the management of premenstrual disorders. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2013;16(4):279-291.

(CME) Going Flat Out for Glycemic Control: The Role of New Basal Insulins in Patient-Centered T2DM Management

Based on material presented at the 2018 Metabolic & Endocrine Disease Summit (MEDS), this CME supplement to Clinician Reviews provides an overview of evidence and best practices for individualizing and intensifying antihyperglycemic therapy using current basal insulin options to achieve patient-centered goals in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Physician assistants, nurse practitioners and nurses will have the opportunity to complete pre- and post-assessment questions to earn a maximum of 1.5 free CME/CE credits.

Dr. Vanita Aroda and Ms. Davida Kruger walk readers through the following learning objectives:

- Explain the role/usage of ultralong-acting basal insulins for addressing the underlying pathophysiology of T2DM

- Compare ultralong-acting and other basal insulins regarding therapeutic characteristics, including pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic profiles, efficacy, safety, and dosing

- Develop patient-centered treatment regimens that include ultralong-acting insulins to minimize barriers to successful use of basal insulin therapy

Based on material presented at the 2018 Metabolic & Endocrine Disease Summit (MEDS), this CME supplement to Clinician Reviews provides an overview of evidence and best practices for individualizing and intensifying antihyperglycemic therapy using current basal insulin options to achieve patient-centered goals in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Physician assistants, nurse practitioners and nurses will have the opportunity to complete pre- and post-assessment questions to earn a maximum of 1.5 free CME/CE credits.

Dr. Vanita Aroda and Ms. Davida Kruger walk readers through the following learning objectives:

- Explain the role/usage of ultralong-acting basal insulins for addressing the underlying pathophysiology of T2DM

- Compare ultralong-acting and other basal insulins regarding therapeutic characteristics, including pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic profiles, efficacy, safety, and dosing

- Develop patient-centered treatment regimens that include ultralong-acting insulins to minimize barriers to successful use of basal insulin therapy

Based on material presented at the 2018 Metabolic & Endocrine Disease Summit (MEDS), this CME supplement to Clinician Reviews provides an overview of evidence and best practices for individualizing and intensifying antihyperglycemic therapy using current basal insulin options to achieve patient-centered goals in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Physician assistants, nurse practitioners and nurses will have the opportunity to complete pre- and post-assessment questions to earn a maximum of 1.5 free CME/CE credits.

Dr. Vanita Aroda and Ms. Davida Kruger walk readers through the following learning objectives:

- Explain the role/usage of ultralong-acting basal insulins for addressing the underlying pathophysiology of T2DM

- Compare ultralong-acting and other basal insulins regarding therapeutic characteristics, including pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic profiles, efficacy, safety, and dosing

- Develop patient-centered treatment regimens that include ultralong-acting insulins to minimize barriers to successful use of basal insulin therapy

Click for Credit: Short-term NSAIDs; endometriosis; more

Here are 5 articles from the November issue of Clinician Reviews (individual articles are valid for one year from date of publication—expiration dates below):

1. Short-term NSAIDs appear safe for high-risk patients

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2PgXKGx

Expires October 8, 2019

2. Chronic liver disease raises death risk in pneumonia patients

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2NPSXXA

Expires October 8, 2019

3. Half of outpatient antibiotics prescribed with no infectious disease code

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2pWEWxU

Expires October 6, 2019

4. Secondary fractures in older men spike soon after first, but exercise may help

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2OCNl8A

Expires October 3, 2019

5. Consider ART for younger endometriosis patients

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2NO1Sc4

Expires October 5, 2019

Here are 5 articles from the November issue of Clinician Reviews (individual articles are valid for one year from date of publication—expiration dates below):

1. Short-term NSAIDs appear safe for high-risk patients

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2PgXKGx

Expires October 8, 2019

2. Chronic liver disease raises death risk in pneumonia patients

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2NPSXXA

Expires October 8, 2019

3. Half of outpatient antibiotics prescribed with no infectious disease code

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2pWEWxU

Expires October 6, 2019

4. Secondary fractures in older men spike soon after first, but exercise may help

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2OCNl8A

Expires October 3, 2019

5. Consider ART for younger endometriosis patients

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2NO1Sc4

Expires October 5, 2019

Here are 5 articles from the November issue of Clinician Reviews (individual articles are valid for one year from date of publication—expiration dates below):

1. Short-term NSAIDs appear safe for high-risk patients

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2PgXKGx

Expires October 8, 2019

2. Chronic liver disease raises death risk in pneumonia patients

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2NPSXXA

Expires October 8, 2019

3. Half of outpatient antibiotics prescribed with no infectious disease code

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2pWEWxU

Expires October 6, 2019

4. Secondary fractures in older men spike soon after first, but exercise may help

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2OCNl8A

Expires October 3, 2019

5. Consider ART for younger endometriosis patients

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2NO1Sc4

Expires October 5, 2019

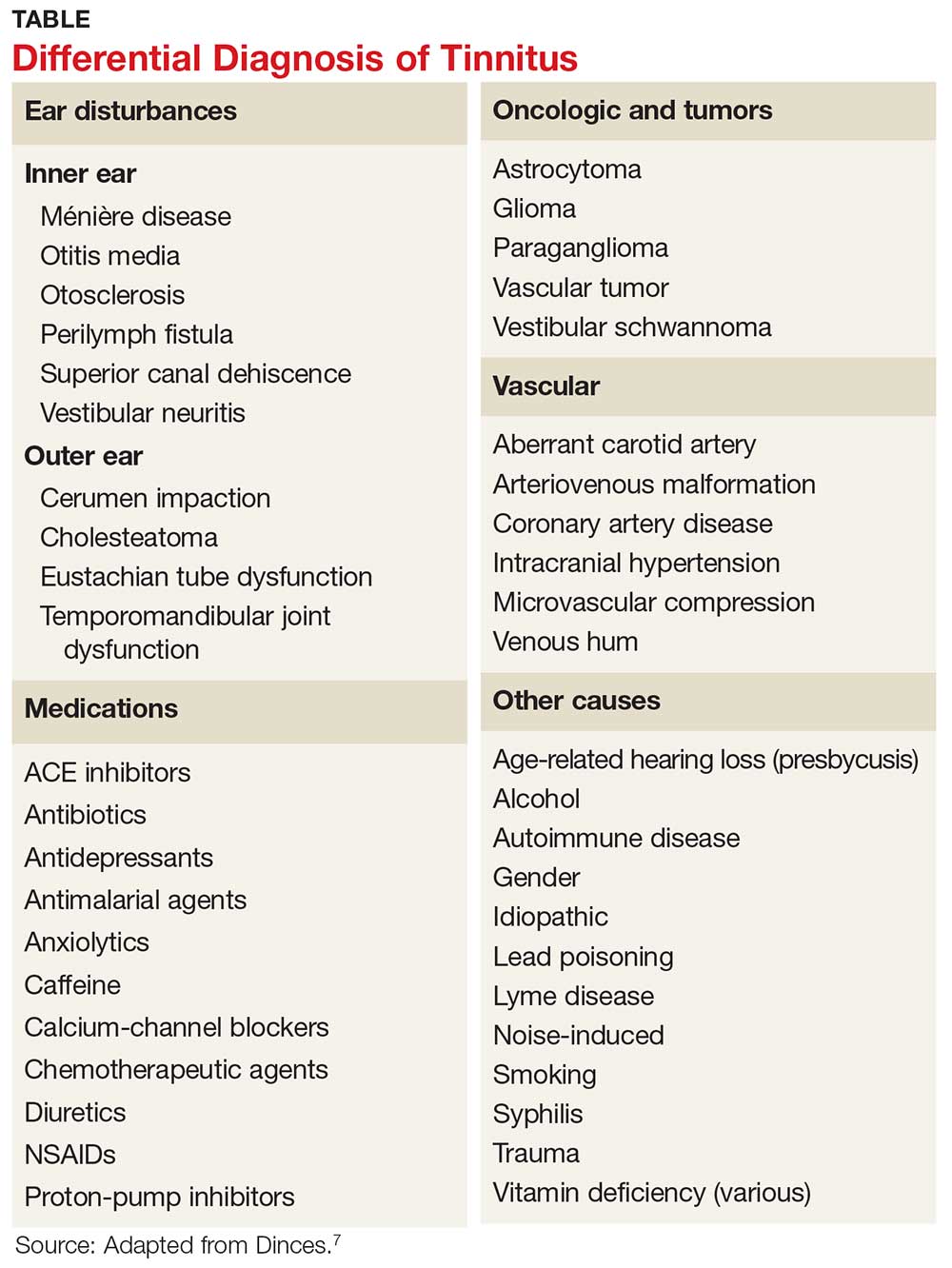

What’s the Buzz? Treatment Strategies in Chronic Subjective Tinnitus

CE/CME No: CR-1810

PROGRAM OVERVIEW

Earn credit by reading this article and successfully completing the posttest and evaluation. Successful completion is defined as a cumulative score of at least 70% correct.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

• Distinguish primary tinnitus from secondary tinnitus.

• Understand and implement a full clinical evaluation of tinnitus, including imaging studies when appropriate.

• Discuss expectations regarding treatment options and realistic outcomes of currently recommended therapy.

• Direct patients to specialist care for cognitive behavioral therapy or tinnitus retraining therapy.

• Know when pharmacotherapeutic intervention is indicated.

FACULTY

Wendy Gillian Ross practices urgent care medicine in Lake Grove, New York, and primary care in Patchogue, New York. Randy Danielsen is Professor and Dean, Arizona School of Health Sciences, and Director, Center for the Future of the Health Professions, both at A.T. Still University, in Mesa, Arizona. He is Physician Assistant Editor-in-Chief of Clinician Reviews.

The authors have no financial relationships to disclose.

ACCREDITATION STATEMENT

This program has been reviewed and is approved for a maximum of 1.0 hour of American Academy of Physician Assistants (AAPA) Category 1 CME credit by the Physician Assistant Review Panel. [NPs: Both ANCC and the AANP Certification Program recognize AAPA as an approved provider of Category 1 credit.] Approval is valid through September 30, 2019.

Article begins on next page >>

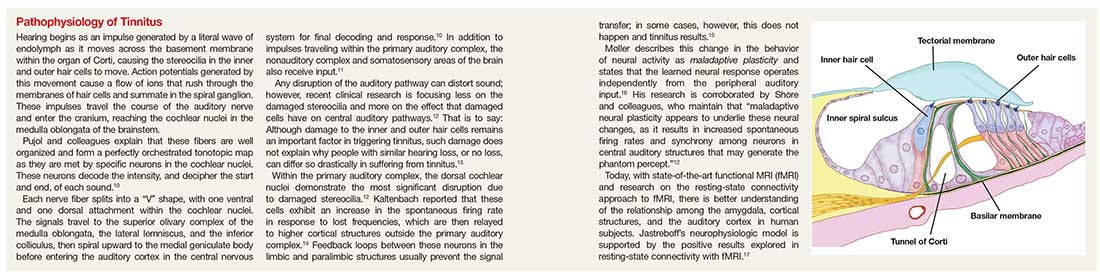

Tinnitus can be a debilitating condition that affects quality of life and is often not treated according to guidelines. Cognitive behavioral therapy and tinnitus retraining therapy have been successful in reducing tinnitus bother; pharmacotherapy is not widely accepted as successful, and can, in fact, be deleterious. This article describes pathophysiologic disturbances of hearing and how they relate to chronic subjective tinnitus, discusses the clinical evaluation of tinnitus as a presenting symptom, and reviews current treatments.

Primary chronic subjective tinnitus, often thought of more as a symptom than a diagnosis, affects millions of people worldwide. This troublesome condition has been chronicled as far back as the first century

It is estimated that only 20% of people who experience tinnitus actively seek treatment.2 In the United States, 2 to 3 million of the 12 million patients who do request treatment report lasting symptoms that they describe as debilitating.3 For patients who seek help, the treatment recommended by physicians is typically pharmacotherapeutic—which does not follow guidelines.4