User login

June 2018: Click for Credit

Here are 4 articles from the June issue of Clinician Reviews (individual articles are valid for one year from date of publication—expiration dates below):

1. Dermatology Practice Gaps: Missed Diagnoses

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2IhaxSm

Expires February 11, 2019

2. When to Worry About Congenital Melanocytic Nevi

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2IhMOBC

Expires March 2, 2019

3. Unscheduled Visits for Pain After Hernia Surgery Common, Costly

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2GbfWIV

Expires February 15, 2019

4. Melanoma Incidence Increased in Older Non-Hispanic Whites

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2wOkVzZ

Expires February 9, 2019

Here are 4 articles from the June issue of Clinician Reviews (individual articles are valid for one year from date of publication—expiration dates below):

1. Dermatology Practice Gaps: Missed Diagnoses

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2IhaxSm

Expires February 11, 2019

2. When to Worry About Congenital Melanocytic Nevi

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2IhMOBC

Expires March 2, 2019

3. Unscheduled Visits for Pain After Hernia Surgery Common, Costly

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2GbfWIV

Expires February 15, 2019

4. Melanoma Incidence Increased in Older Non-Hispanic Whites

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2wOkVzZ

Expires February 9, 2019

Here are 4 articles from the June issue of Clinician Reviews (individual articles are valid for one year from date of publication—expiration dates below):

1. Dermatology Practice Gaps: Missed Diagnoses

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2IhaxSm

Expires February 11, 2019

2. When to Worry About Congenital Melanocytic Nevi

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2IhMOBC

Expires March 2, 2019

3. Unscheduled Visits for Pain After Hernia Surgery Common, Costly

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2GbfWIV

Expires February 15, 2019

4. Melanoma Incidence Increased in Older Non-Hispanic Whites

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2wOkVzZ

Expires February 9, 2019

Heart Failure: A Dynamic Approach to Classification and Management

CE/CME No: CR-1805

PROGRAM OVERVIEW

Earn credit by reading this article and successfully completing the posttest and evaluation. Successful completion is defined as a cumulative score of at least 70% correct.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

• Develop an understanding of the classification of heart failure and its associated signs and symptoms.

• Describe clinical findings of heart failure from the physical exam.

• Understand the utility of laboratory and imaging studies for diagnosis of heart failure and its underlying causes.

• Demonstrate knowledge of nonpharmacotherapeutic and pharmacotherapeutic options for managing heart failure.

FACULTY

Michael Roscoe is Chair/Program Director and Associate Professor, Andrew Lampkins is Associate Professor, Sean Harper is Assistant Professor, and Gina Niemeier is Associate Program Director and Assistant Professor, in the PA Department at the University of Evansville in Indiana.

The authors have no financial relationships to disclose.

ACCREDITATION STATEMENT

This program has been reviewed and is approved for a maximum of 1.0 hour of American Academy of Physician Assistants (AAPA) Category 1 CME credit by the Physician Assistant Review Panel. [NPs: Both ANCC and the AANP Certification Program recognize AAPA as an approved provider of Category 1 credit.] Approval is valid through April 30, 2019.

Article begins on next page >>

Heart failure is a complex syndrome with a spectrum of signs and symptoms that range from asymptomatic to terminal. This variability of presentation, paired with the irreversibility of the process, make it both difficult and critical to identify this syndrome early to prevent progression. Here is an overview of the classification and common presentations of heart failure, as well as a guide to diagnostic modalities and treatment options.

Heart failure (HF) is a complex syndrome, not a specific disease; it is always associated with an underlying cause. Hypertension and coronary artery disease are the two most common causes in all age groups, but a number of other conditions—valvular disease, unrecognized obstructive sleep apnea, obesity, chronic kidney disease, anemia, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, and atrial fibrillation—have been identified as secondary causes.1-3

Often, however, clinicians do not identify HF until the syndrome reaches an advanced stage—at which point, the damage is irreversible and pharmacotherapeutic management is limited to control of signs and symptoms. The ramifications are concerning, since HF has achieved near-epidemic scope in the United States. An estimated 5.7 million Americans ages 20 and older have HF; prevalence is projected to increase by 46% between 2012 and 2030—resulting in more than 8 million affected individuals (ages 18 and older).4,5 More than 1 million patients are discharged from the hospital annually with a primary diagnosis of HF.4 And in 2013, one in nine death certificates in the US mentioned HF.4

Most cases of HF are managed in primary care. Established, evidence-based therapies should be implemented in the outpatient setting when possible, as early in the course as possible. Referral to a cardiologist is needed when the underlying cause of HF remains undetermined, or when specialized treatment is required.

CLASSIFICATION OF HF

The two most widely recognized classification systems for HF are those of the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) and of the New York Heart Association (NYHA). Both focus on one-year mortality. The stages of the ACC/AHA system (A to D) are based on worsening of both structural heart disease and clinical symptoms of HF. The NYHA designations (Class I to IV) are based on the functional capability associated with physical activity. Both systems are outlined in Table 1.3,6,7

While these systems are used to “stage” HF, there are several ways the syndrome is classified in the medical literature. For example, HF can be described by

- Anatomy (left- or right-sided)

- Physiology (dilated and hypertrophic)

- Course (chronic or acute heart failure [cardiogenic shock])

- Output (high- or low-output failure)

- Ejection fraction (reduced or preserved)

- Pressure phase (systolic and diastolic).

All these classifications have merit; however, this article will attempt to simplify the approach to patients with HF and focus on systolic HF, defined as a reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), and diastolic HF, defined as a preserved LVEF. Although the common perception of HF among clinicians—and thus the traditional diagnostic focus—is reduced LVEF (systolic HF), preserved LVEF (diastolic HF) in fact represents approximately 50% of cases.1 Diastolic HF is estimated to be increasing in prevalence and is expected to become the more common phenotype.8

Continue to: SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Heart failure is characterized by a constellation of signs and symptoms of pulmonary and/or systemic venous congestion caused by impaired ability of the heart to fill with or eject blood in proportion to the metabolic needs of the body.1 Manifestations include fatigue, dyspnea, fluid retention, and cachexia, and patients can present anywhere on the spectrum—from asymptomatic at rest to severely symptomatic.

Symptoms

In both reduced LVEF and preserved LVEF HF, common early symptoms include dyspnea and fatigue on exertion, with or without some degree of lower-extremity swelling.2 Lack of treatment and disease progression increase symptom severity—to the extent that dyspnea and fatigue start to occur at rest. Reviewing the anatomic classifications/findings of HF facilitates understanding of the clinical symptoms.

Right HF. Right ventricular dysfunction is rarely found in isolation; when symptoms are present, further evaluation of the left ventricle and the pulmonary system (to look for cor pulmonale) is warranted. Right HF is associated with an inability to manage venous return and move volume into the pulmonary circuit. This produces the predominant symptom of fluid retention. Peripheral edema is a cardinal symptom of right HF; edema can also present systemically, mostly as hepatic congestion or general gastrointestinal complaints resulting from impaired gastrointestinal perfusion.9

Left HF. Left ventricular dysfunction is the more common anatomic finding in HF and is often generalized to represent all cases. The dysfunction can be found in isolation and is actually the leading cause of right HF. In left HF (regardless of etiology), the heart does not produce enough “forward” pressure (ie, cannot pump or fill with enough blood) for the cardiovascular system to remain in balance. Thus, “back” pressure into the pulmonary circuit develops.

The combination of insufficient systemic perfusion capability with a dysfunctional left pump means that the most common symptom in all cases of left HF is shortness of breath—specifically, exertional dyspnea. Dyspnea can progress to orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, and, finally, dyspnea at rest. Patients often present with a cough that is worse while lying down and that can be nonproductive or productive, depending on volume status.9,10

Signs

Vital signs range from normal to indicative of shock. Increased sympathetic nervous system activity is common; this may manifest as coldness of the extremities and diaphoresis. Keep in mind that HF is a clinical diagnosis: The physical examination, focusing on peripheral signs, is key in all HF patients for both diagnosis and management.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

The physical exam includes the heart, neck, lungs, abdomen, and extremities. The cardiac exam includes evaluation for hypertrophy, by palpating for the point of maximum impulse to assess for lifts, heaves, valvular disease, and S3 and S4 sounds. Respiratory, abdominal, and extremity exams all focus on the evaluation of fluid status and edema.

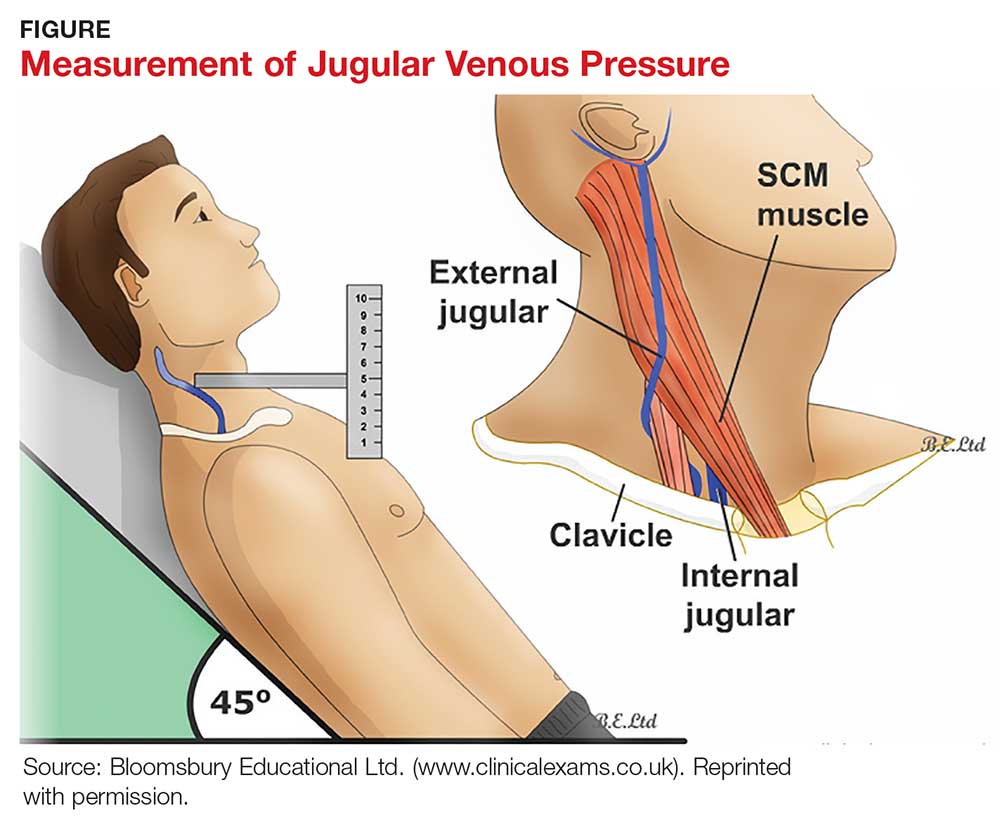

A key, often underutilized measurement is jugular venous pressure (JVP). Elevated JVP has been identified as the most specific sign of fluid overload in HF and the most important physical finding in the initial and subsequent examinations of a patient with HF.11 (For good reason, clinicians who treat patients with HF must be able to recognize volume overload and hypovolemia; euvolemia allows patients to remain symptom-free and makes it possible to initiate life-prolonging therapy, which will be discussed in the Treatment section.2) JVP is an indirect measure of pressure within the right side of the heart (central venous pressure).

Most texts on performing the physical exam recommend measuring JVP using the right internal jugular vein. However, use of the internal jugular vein is limiting in HF patients, because it is covered by the sternocleidomastoid muscle for most of its course in the neck and visible only in a small triangle between the two heads in the root of the neck (see Figure). Conversely, the external jugular veins are subcutaneous along their entire course and pulsations are easily visible—but superficial and prone to external pressure and internal occlusion. A nonpulsatile, distended jugular vein should not be used to estimate venous pressure.2

What, then, is the best method? Vinayak et al evaluated the comparative effectiveness of the internal and external jugular veins for detection of central venous pressure. They found that the external jugular vein is easier to visualize and has excellent reliability for determining low and high venous pressures.12

The process for estimating JVP is the same regardless of which jugular vein (internal or external) is used. The technique is described by Bickley in Bates’ Guide to Physical Examination and History Taking:

The patient lies supine and at an angle between 30° and 45°. Turn the head slightly, and with tangential lighting, identify the external and internal jugular veins. Identify the highest point of pulsation in the right jugular vein and extend a long rectangular object or card horizontally from this point and a centimeter ruler vertically from the sternal angle, making an exact right angle. Measure the vertical distance (in centimeters) above the sternal angle where the horizontal object crosses the ruler and add this distance to 4 cm. Measurements of > 3-4 cm above the sternal angle or > 8 cm in total distance are considered elevated.13

Continue to: DIAGNOSTIC AND SCREENING TESTS

DIAGNOSTIC AND SCREENING TESTS

Several diagnostic studies can identify HF or elucidate underlying causes. However, not all tests yield sufficient information for diagnosis—and commonly held “maxims” about findings that definitively rule in or out the diagnosis have been confounded by the available evidence.

Laboratory tests. The lab parameter most associated with HF is brain natriuretic peptide (BNP). Natriuretic peptides are produced primarily within the heart and released into the circulation in response to increased wall tension.14 In contrast to atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP), BNP is secreted not only from the atria but also from the ventricles, especially in patients with HF.15

Circulating concentrations of several cardiac natriuretic peptides—including ANP, BNP, and the two peptides’ N-terminal pro-hormones (N-terminal pro-atrial natriuretic peptide and N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide, respectively) are elevated in both symptomatic and asymptomatic patients with left ventricular dysfunction.16 These levels are generally elevated for both systolic and diastolic HF. However, in one study, as many as 30% of diastolic HF patients had a low BNP level, despite signs and symptoms of HF and significantly elevated left ventricular filling pressures, as determined by invasive hemodynamic monitoring.17 Comorbid obesity is associated with low levels of natriuretic peptides.18

Additional lab tests can provide information about underlying causes of HF or reveal contraindications to certain treatment options (to be discussed in the Treatment section). A complete blood count (CBC) might reveal anemia, which can cause or aggravate HF, and which is an important consideration in management because of its association with decreased renal function, hemodilution, and proinflammatory cytokines. Leukocytosis can signal underlying infection. A troponin assay is helpful for ruling out acute MI as a cause of worsening HF in acute cases. Thyroid function tests and iron studies can be considered to rule out secondary causes of HF.

A serum electrolyte screen should be ordered; results are usually within normal ranges. Hyponatremia is an indicator of activation of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS) and may be seen in the context of prolonged salt restriction and diuretic therapy. Hyperkalemia and hypokalemia are also prevalent in HF; both are limiting factors for some treatment options. A low sodium level is often the result of increased congestion and release of vasopressin; a level of ≤ 135 mEq/L predicts a poorer outcome.

Kidney function tests can determine whether HF is associated with impaired kidney function, secondary to poor renal perfusion. Poor renal function may limit treatment options. Patients with severe HF, particularly those receiving a high dosage of a diuretic for a long period, may have elevated levels of blood urea nitrogen and creatinine, indicating renal insufficiency.

Electrocardiography and chest radiography. ECGs and chest radiographs are noninvasive tests that have been used widely in the diagnosis of HF. They might indicate an underlying cause (eg, acute MI, ischemia, secondary arrhythmia) but are often nonspecific—and thus may be unhelpful in the diagnosis and treatment of HF.

The most common ECG findings in HF are nonspecific ST-T wave abnormalities.19 Other findings often consist of low-voltage left ventricular hypertrophy, conduction defects, and repolarization changes. With chest radiography, primary findings in HF include pulmonary edema—seen as perivascular edema, peribronchial cuffing, perihilar haze, interstitial edema (Kerley B, or septal, lines), and alveolar fluid—and pleural effusion.19,20

For both these modalities, however, there are commonly held conceptions that particular findings rule out HF—which has been disproven by Fonseca and colleagues.19 Because most patients with HF have an abnormal ECG, some studies have proposed that a normal ECG virtually rules out left ventricular systolic dysfunction.20 Evaluating the value of ECG in HF diagnosis, Fonseca et al found that about 85% of patients with an abnormal ECG had HF—but so did 30% of patients with a normal ECG. They concluded that, if used alone, ECG could have missed as many as 25% of patients with HF.19

Likewise, it has been suggested that a patient cannot have HF if heart size is normal on a chest radiograph.20 Fonseca et al found that cardiac enlargement, while the most informative radiologic measurement in HF, was present in only half of patients with HF.19 About 57% of patients who had an abnormal chest radiograph had HF, but so did about 40% of those who had a normal chest radiograph.19 Therefore, abnormal chest radiograph for identification of HF had an estimated sensitivity of 57%, a specificity of 78%, positive predictive value of 50%, and negative predictive value of 83%.19 The conclusion: Caution should be taken regarding the use of chest radiography in isolation to make a diagnosis of HF.

Echocardiography. The most useful test in evaluating HF is the echocardiogram, because it can distinguish between HF with and without preserved left ventricular systolic function. This is critical: The most clinically relevant classification of HF differentiates systolic and diastolic HF, based on LVEF.2 This determination has both prognostic and therapeutic implications.21

Echocardiography is widely available, safe, and noninvasive. The “echo” can identify the size of the atria and ventricles, valve function and dysfunction, and any associated shunting. Pericardial effusions and heart wall-motion abnormalities (for example, an old MI) are also easily identified.9

A normal ejection fraction does not rule out HF. Therefore, assessment of LVEF should not be considered until after a clinical diagnosis has been made, because more than half of HF patients have a normal LVEF—evidence that can confound the diagnostic process.2

Continue to: TREATMENT OF HEART FAILURE WITH REDUCED LVEF

TREATMENT OF HEART FAILURE WITH REDUCED LVEF

The body’s neurohormonal system, including the RAAS and the sympathetic nervous system, is activated to compensate for the insufficient cardiac performance found in HF. However, activation of these systems contributes to worsening HF, deterioration of quality of life, and poor outcomes.22 Therefore, therapies that suppress these responses can reduce the progression of HF.

Treatment of HF is generally divided into symptom-relieving treatment and disease-modifying/life-prolonging treatment.1 Symptom relief is similar in both systolic and diastolic HF. However, most evidence-based, disease-modifying treatment focuses on systolic HF; guidelines for disease-modifying treatment of diastolic HF are minimal.1

Treatment of reversible causes

Since HF is caused by something else, the primary focus of management is addressing underlying causes. The primary goal is to relieve symptoms while improving functional status—which should lead to a decrease in hospitalization and premature death.

The first step is to evaluate patients’ use of medications that can contribute to a worsening of HF.9 The most common offending medications are calcium-channel blockers with negative inotropy (non-dihydropyridine calcium-channel blockers, eg, verapamil and diltiazem); some antiarrhythmic drugs (eg, amiodarone); thiazolidinediones (glitazones); and NSAIDs.9 If identified as a possible contributor to HF symptoms, these agents should be stopped (if possible) or replaced.

Nonpharmacotherapy

Effective counseling and education of patients with HF may help with long-term adherence to treatment plans. Patients can be taught to monitor their weight at home and to adjust the dosage of diuretics as advised: A sudden increase in weight (> 2 kg in one to three d), for example, should alert a patient to alter treatment or seek advice.23

Diet modification is a multifactorial recommendation. Proper nutrition is critical because HF patients are at increased risk for malnutrition due to poor appetite, malabsorption, and increased nutritional requirements.23 Weight reduction in obese patients helps reduce cardiac workload. Patients should be placed on salt restriction (2 to 2.6 g/d of sodium).9,23

Exercise has been shown to relieve symptoms, provide a greater sense of well-being, and improve functional capacity. It does not, however, result in obvious improvement in cardiac function.22

Alcohol consumption should be restricted because of the myocardial depressant properties of alcohol and its direct toxic effect on the myocardium.22 Smoking should be discouraged because it has a direct effect on coronary artery disease.

Influenza and pneumococcal vaccination should be considered in all patients with HF.23 Heart failure predisposes patients to, and can be exacerbated by, pulmonary infection and exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Evaluation and management of obstructive sleep apnea should be performed. Sleep-disordered breathing, an umbrella term that covers obstructive and central sleep apneas, has been found to increase the risk for poor prognosis in HF.24 All patients with HF should be tested for obstructive sleep apnea because, often, only the patient’s bed partner is aware of disordered sleep. For unknown reasons, patients with HF do not report subjective sleepiness.25

Continue to: Pharmacotherapy

Pharmacotherapy

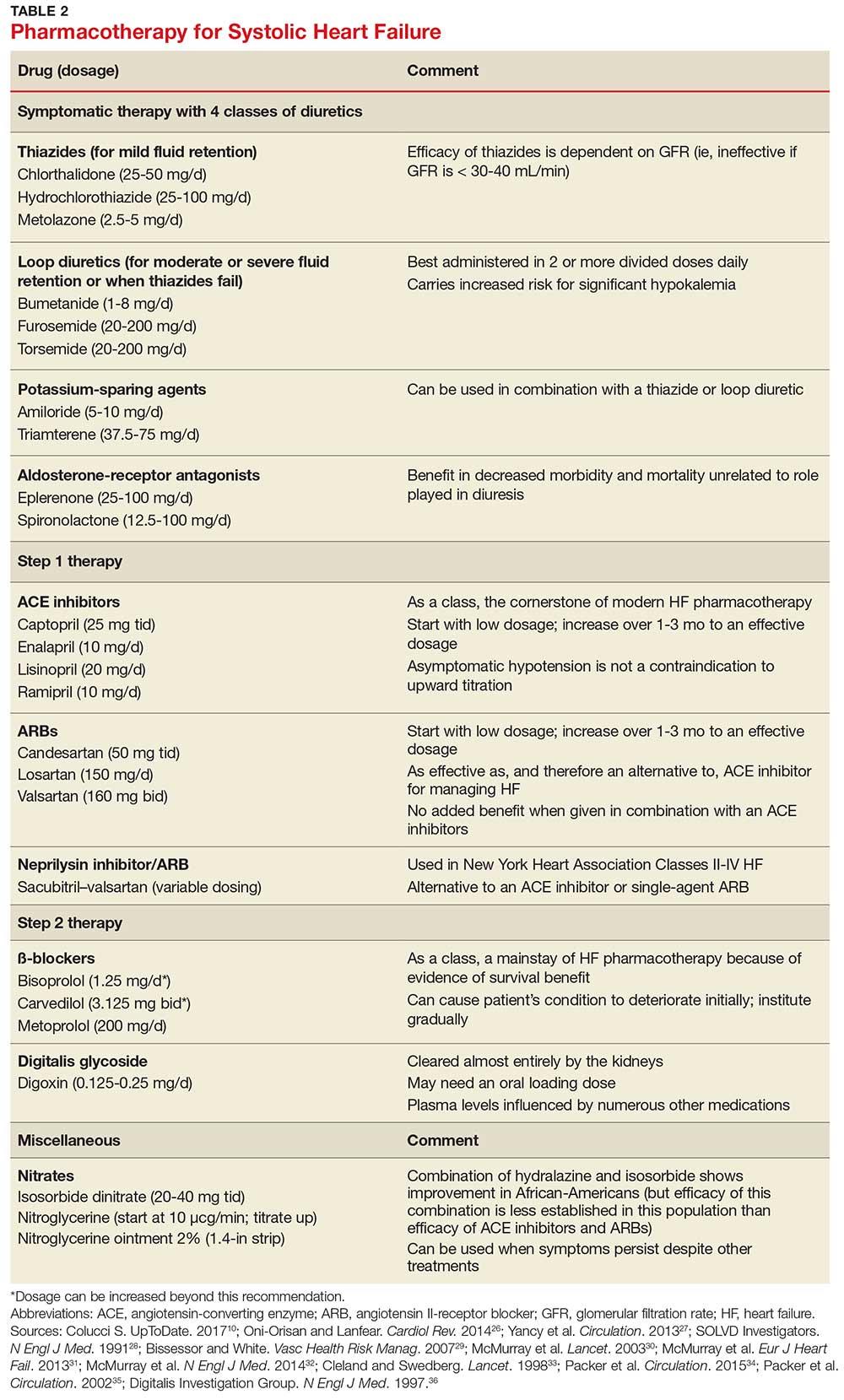

Diuretics have not been found to have benefit for reducing early mortality but are the most common agents used for symptomatic relief of sodium and water retention.26 In fact, few patients with signs and symptoms of fluid retention can be managed without a diuretic.9 Caution must be observed, however, because excessive diuresis can lead to electrolyte imbalance and neurohormonal activation.

Treating mild fluid retention with a thiazide diuretic (hydrochlorothiazide, metolazone, or chlorthalidone) is often sufficient (see Table 2 for dosing and other information on these and other drugs for treating HF).9 Thiazide diuretics are dependent on the glomerular filtration rate and are ineffective when it falls below 30-40 mL/min. Adverse reactions to diuretics include hypokalemia, dehydration (intravascular volume depletion) with prerenal azotemia, skin rash, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, hyperglycemia, hyperuricemia, and hepatic dysfunction.

In cases of moderate or severe HF, or failure of thiazide diuretics to relieve mild symptoms, an oral loop diuretic (furosemide, bumetanide, or torsemide; see Table 2 for dosing) can be used if kidney function is preserved.9 These agents are best administered in two or more divided doses. Major adverse reactions are similar to those of thiazide diuretics, plus ototoxicity. Special caution must be used when a loop diuretic is co-administered with digitalis because the combination can cause significant hypokalemia.9

A potassium-sparing diuretic (triamterene or amiloride; see Table 2) can be used in combination with thiazide and loop diuretics.9 The location of their action is at the distal tubule, but diuretic potency is mild. Potassium-sparing agents can minimize hypokalemia induced by other diuretics. Adverse effects include hyperkalemia, kidney dysfunction, and gastrointestinal symptoms.

The aldosterone-receptor antagonists spironolactone and eplerenone are specific inhibitors of aldosterone, an effect that has been shown to improve clinical outcomes.9 Aldosterone-receptor antagonists are indicated for patients with NYHA class II-IV HF who have LVEF ≤ 35% or those with a history of acute MI, LVEF < 40%, and symptoms of HF.27 In these patients, a reduction in mortality and relative risk has been demonstrated with the use of aldosterone-receptor antagonists, unrelated to their role in diuresis. The adverse effect profile of spironolactone includes gynecomastia.

Continue to: Inhibitors of the RAAS

Inhibitors of the RAAS. As noted, the RAAS plays a key role during the development and worsening of HF.22

Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE inhibitors) constitute the cornerstone of modern HF pharmacotherapy and have compelling evidence of survival benefit.28 These agents (captopril, enalapril, lisinopril, and ramipril; see Table 2 for dosing) have been shown to be effective therapy for HF and post-MI left ventricular dysfunction.29 They reduce early mortality by approximately 20% in symptomatic HF and can prevent hospitalization, increase exercise tolerance, and reduce adverse events (symptoms).9

Because of these benefits, ACE inhibitors should be firstline therapy in all HF patients with left ventricular dysfunction. They are usually used in combination with a diuretic. In addition, ACE inhibitors should be used in patients with reduced LVEF, even if they are asymptomatic, because these agents prevent progression to clinical HF.

Since ACE inhibitors carry the risk for severe hypotension, caution must be used, especially during treatment initiation. Patients whose systolic blood pressure is < 100 mm Hg, or who are hypovolemic, should be started at a low dosage (captopril, 6.25 mg tid; enalapril, 2.5 mg/d; or other equivalent ACE inhibitor dose); for other patients, these dosages can be doubled at initiation.9 Within days of initiation, but no longer than two weeks later, patients should be screened for hypotension and have both kidney function and potassium levels monitored. The dosage of ACE inhibitors should be increased over one to three months to an effective dosage (eg, captopril, 25 mg tid; enalapril, 10 mg bid; ramipril, 10 mg/d; and lisinopril, 20 mg/d, or other equivalent ACE inhibitor dose).9

Asymptomatic hypotension is not a contraindication to continuation or uptitration of the dosage of ACE inhibitors. Patients may also experience an increase in the serum creatinine or potassium level; likewise, this should not prompt a change in dosage if the elevated level stabilizes. The most common adverse effects of ACE inhibitors are dizziness and cough.9

Angiotensin II-receptor blockers (ARBs) have been shown to be as effective as ACE inhibitors for the management of hypertension, congestive HF, and chronic renal failure.30 ARBs decrease the adverse effects of angiotensin II, but do not have the same effects that ACE inhibitors do on other pathways found in HF (specifically, on bradykinin, prostaglandins, and nitric oxide).29 Candesartan and valsartan have been shown to have benefits in HF and are an equivalent alternative to ACE inhibitors; they are often used when a patient cannot tolerate an ACE inhibitor. Because ARBs and ACE inhibitors affect the RAAS at different points in the pathway, there is a theoretical basis for ARB and ACE inhibitor combination therapy; in clinical studies to date, however, the combination has shown no beneficial effect and rather was associated with more adverse effects.29

Neprilysin inhibitor. Recently, the combination of the neprilysin inhibitor sacubitril and an ARB, valsartan, has surfaced as an alternative to ACE inhibitor or single-agent ARB therapy.31,32 Inhibition of the enzyme neprilysin results in an increase in levels of endogenous vasoactive peptides (eg, natriuretic peptides and bradykinin), which may benefit hemodynamics in patients with HF. However, use of an ARB in combination with sacubitril is necessary to counteract the increase in angiotensin II levels that also results from inhibition of neprilysin.33

Sacubitril–valsartan is typically reserved for patients with mild-to-moderate HF who have either an elevated BNP (≥ 50 pg/mL) or an HF-related hospitalization within the past year. Upon transitioning from an ACE inhibitor (or single-agent ARB), a 36-hour washout period must be observed before starting sacubitril–valsartan to minimize the risk for angioedema. Because therapy with sacubitril–valsartan leads directly to an elevation in the BNP level, using the level of N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide—which is not degraded by neprilysin—to monitor disease progression is recommended.34

ß-

Initiation of ß-blockers in stable patients can cause general deterioration; initiation must therefore be done gradually:

- Carvedilol, initiated at 3.125 mg bid, can be increased to 6.25 mg, then 12.5 mg, and then 25 mg, all bid, at intervals of approximately two weeks

- Sustained-release metoprolol can be started at 12.5 mg/d or 25 mg/d and doubled at two weeks to a target of 200 mg/d

- Bisoprolol, initiated at 1.25 mg/d, can be increased incrementally to 2.5 mg/d, 3.75 mg/d, 5 mg/d, 7.5 mg/d, or 10 mg/d at one-to-four-week intervals.9

Patients taking ß-blockers need to monitor their weight at home as an indicator of fluid retention. If HF becomes worse, an increase in the dosage of the accompanying diuretic, a delay in the increase of the ß-blocker, or downward adjustment of the ß-blocker is usually sufficient.

Continue to: Digitalis glycoside

Digitalis glycoside. Digoxin has been shown to relieve the symptoms of HF, decrease the risk for hospitalization, and increase exercise tolerance; however, it has not been shown to offer a mortality benefit.36 Digoxin should be considered for patients who remain symptomatic when taking a diuretic and an ACE inhibitor and for patients who are also in atrial fibrillation and need rate control.

Digoxin is cleared almost entirely by the kidneys and therefore must be used with care in patients with renal dysfunction. Patients usually can be started on the expected maintenance dosage (0.125-0.25 mg/d). An oral loading dose of 0.75-1.25 mg over 24 to 48 hours can be used if an early effect is needed.9

Digoxin can induce ventricular arrhythmias (especially in a setting of hypokalemia and ischemia) and is sensitive to other medications that can drastically increase its level—most notably, amiodarone, quinidine, propafenone, and verapamil.9 The digoxin blood level should be measured every seven to 14 days until a maintenance dosage is established, and again whenever there is a change in medication or kidney function. The optimum serum level is 0.7-1.2 ng/mL; toxicity is not usually seen at < 1.8 ng/mL.9

Hydralazine and nitrates. The combination of hydralazine and isosorbide dinitrate has been shown to improve outcomes in African-American patients with HF, but efficacy is less well-established in this population than for ACE inhibitor and ARB therapy.9 This combination can be considered in patients who are unable to tolerate ACE inhibitor or ARB therapy. It can also be considered in those who have persistent symptoms despite treatment with a ß-blocker, ACE inhibitor, or aldosterone antagonist.9

Intravenous nitrates are used primarily for acute HF, especially when accompanied by hypertension or myocardial ischemia. The starting dosage for nitroglycerin is approximately 10 μcg/min, titrated upward by 10-20 μcg/min to a maximum of 200 μcg/min. Isosorbide dinitrate (20-40 mg tid) and nitroglycerine ointment 2% (1.4 in applied every six to eight hours [although generally reserved for inpatient therapy]) are equally effective.9 Adverse effects that may limit the use of these agents are headache and hypotension. Patients also develop tolerance for nitrates, which can be mitigated if a daily 8-to-12–hour nitrate-free period is instituted.9

TREATMENT OF HEART FAILURE WITH PRESERVED LVEF

Treatment options for patients with preserved LVEF (diastolic HF) are not as clear as those for patients with reduced LVEF (systolic HF). No traditional therapies (ACE inhibitors, ARBs, ß-blockers, digoxin) have been shown to improve survival in this population, although a recent study on the effects of spironolactone in diastolic HF did show some improvement of diastolic dysfunction without adverse effects.17,37 In the absense of clear evidence-based therapies, treatment focuses on managing comorbidities, addressing reversible causes, and alleviating fluid overload with a diuretic.9,17

Diuretic therapy is critical to control fluid overload; regimens are similar to those for HF with reduced LVEF. ACE inhibitors and ARBs have not been shown to improve outcomes in this population but can be used to manage comorbid hypertension. Spironolactone has also not been shown to improve outcomes in patients with diastolic HF.9

The principal conditions that can lead to HF with preserved LVEF are hypertension, pericardial disease, and atrial tachycardia. Tachycardia is associated with overall shorter diastolic filling time; controlling an accelerated heart rate, therefore, is theorized to be an important therapeutic goal.9 Other disease states, including diabetes mellitus, sleep-disordered breathing, obesity, and chronic kidney disease, can all lead to HF with preserved LVEF.

CONCLUSION

Managing HF today requires an “upstream” model of care, by which providers consider the diagnosis/syndrome of HF in the asymptomatic patient with risk factors (Stage A/Class I and Stage B/Class II). Perhaps a better way to state this is that providers must change their approach from ruling-in to ruling-out HF. Any person in whom a decrease in activity level, mild shortness of breath, or edema are observed, and who has known risk factors, should be considered to have HF until proven otherwise.

Because of the wide variability in the underlying causes of HF, providers must be dynamic in both their clinical approach and their treatment plans to optimize care for the individual patient. Finally, providers must also take note of the increasing prevalence of diastolic HF and, again, focus on early diagnosis.

1. Lam CS, Donal E, Kraigher-Krainer E, Vasan RS. Epidemiology and clinical course of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail. 2011;13(1):18-28.

2. Ahmed A. DEFEAT - Heart failure: a guide to management of geriatric heart failure by generalist physicians. Minerva Med. 2009;100(1):39-50.

3. Hunt SA, Baker DW, Chin MH, et al. ACC/AHA guidelines for the evaluation and management of chronic heart failure in the adult: executive summary. A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee to revise the 1995 Guidelines for the Evaluation and Management of Heart Failure). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001; 38(7):2101-2113.

4. Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, et al; Writing Group Members, American Heart Association Statistics Committee; Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2016 Update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;26: 133(4):e38-e360.

5. Heidenreich PA, Albert NM, Allen LA, et al; American Heart Association Advocacy Coordinating Committee; Council on Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology; Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention; Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Epidemiology and Prevention; Stroke Council. Forecasting the impact of heart failure in the United States: a policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6(3):606-619.

6. American Heart Association. Classes of heart failure (2017). www.heart.org/HEARTORG/Conditions/HeartFailure/AboutHeartFailure/Classes-of-Heart-Failure_UCM_306328_Article.jsp#.V8cFhfkrLRY. Accessed March 7, 2018.

7. New York Heart Association Criteria Committee. Nomenclature and Criteria for Diagnosis of Diseases of the Heart and Great Vessels. 9th ed. Boston, MA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 1994.

8. Owan TE, Hodge DO, Herges RM, et al. Trends in prevalence and outcome of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(3):251-259.

9. Bashore T, Granger C, Hranitzy P, Patel M. Heart diseases. In: Papadakis MA, McPhee SJ, Rabow MW, eds. Current Medical Diagnosis and Treatment. 55th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education; 2016:402.

10. Colucci S. Patient education: heart failure (beyond the basics). Waltham, MA: UpToDate; 2017. www.uptodate.com/contents/heart-failure-beyond-the-basics?view=print. Accessed March 7, 2018.

11. Butman S, Ewy GA, Standen J, et al. Bedside cardiovascular examination in patients with severe chronic heart failure: importance of rest or inducible jugular venous distention. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1993;22(4):968-974.

12. Vinayak A, Levitt J, Gehlbach B, et al. Usefulness of the external jugular vein examination in detecting abnormal central venous pressure in critically ill patients. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(19):2132-2137.

13. Bickley LA. Bates’ Guide to Physical Examination and History Taking. 11th ed. Alphen aan den Rijn, The Netherlands: Wolters Kluwer; 2012:364-365.

14. Kinnunen P, Vuolteenaho O, Ruskoaho H. Mechanisms of atrial and brain natriuretic peptide release from rat ventricular myocardium: effect of stretching. Endocrinology. 1993;132(5):1961-1970.

15. Yasue H, Yoshimura M, Sumida H, et al. Localization and mechanism of secretion of B-type natriuretic peptide in comparison with those of A-type natriuretic peptide in normal subjects and patients with heart failure. Circulation. 1994;90(1):195-204.

16. Cowie M, Struthers A, Wood D, et al. Value of natriuretic peptides in assessment of patients with possible new heart failure in primary care. Lancet. 1997;350(9088):1349-1353.

17. Oktay AA, Shah SJ. Diagnosis and management of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: 10 key lessons. Curr Cardiol Rev. 2015;11(1):42-52.

18. Horwich TB, Hamilton MA, Fonarow GC. B-type natriuretic peptide levels in obese patients with advanced heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47(1):85-90.

19. Fonseca C, Mota T, Morais H; EPICA Investigators. The value of the electrocardiogram and chest X-ray for confirming or refuting a suspected diagnosis of heart failure in the community. Eur J Heart Fail. 2006;6(6):807-812.

20. Rihal CS, Davis KB, Kennedy JW, Gersch BJ. The utility of clinical, electrocardiographic, and roentgenographic variables in the prediction of left ventricular function. Am J Cardiol. 1995;75(4):220-223.

21. Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. A Comprehensive Review of Development and Testing for National Implementation of Hospital Core Measures. 2002. www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/18/A_Comprehensive_Review_of_Development_for_Core_Measures.pdf. Accessed March 6, 2018.

22. Kemp CD, Conte JV. The pathophysiology of heart failure. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2012;21(5):365-371.

23. Gibbs CR, Jackson G, Lip GY. ABC of heart failure: Nondrug management. BMJ. 2000;320(7231):365-369.

24. Wang H, Parker JD, Newton GE, et al. Influence of obstructive sleep apnea on mortality in patients with heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49(15):1625-1631.

25. Arzt M, Young T, Finn L, et al. Sleepiness and sleep in patients with both systolic heart failure and obstructive sleep apnea. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(16):1716-1722.

26. Oni-Orisan A, Lanfear DE. Pharmacogenomics in heart failure: where are we now and how can we reach clinical application? Cardiol Rev. 2014;22(5):193-198.

27. Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. Circulation. 2013;128(16):1810-1852.

28. SOLVD Investigators, Yusuf S, Pitt B, Davis CE, Hood WB, Cohn JN. Effect of enalapril on survival in patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fractions and congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1991;325(5):293-302.

29. Bissessor N, White H. Valsartan in the treatment of heart failure or left ventricular dysfunction after myocardial infarction. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2007;3(4):425-430.

30. McMurray JJ, Ostegren J, Swedberg K, et al. Effects of candesartan in patients with chronic heart failure and reduced left-ventricular systolic function taking angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors: the CHARM-Added trial. Lancet. 2003;362(9386):767-771.

31. McMurray JJ, Packer M, Desai AS, et al; PARADIGM-HF Committees and Investigators. Dual angiotensin receptor and neprilysin inhibition as an alternative to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition in patients with chronic systolic heart failure: rationale for and design of the Prospective comparison of ARNI with ACEI to Determine Impact on Global Mortality and morbidity in Heart Failure trial (PARADIGM-HF). Eur J Heart Fail. 2013;15(9):1062-1073.

32. McMurray J, Packer M, Desai A, et al; PARADIGM-HF Committees and Investigators. Angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition versus enalapril in heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(11):993-1004.

33. Cleland JG, Swedberg K. Lack of efficacy of neutral endopeptidase inhibitor ecadotril in heart failure. The International Ecadotril Multi-centre Dose-ranging Study Investigators. Lancet. 1998;351(9116):1657-1658.

34. Packer M, McMurray JJ, Desai AS, et al; PARADIGM-HF Committees and Investigators. Angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibition compared with enalapril on the risk of clinical progression in surviving patients with heart failure. Circulation. 2015;131(1):54-61.

35. Packer M, Fowler MB, Roecker EB, et al; Carvedilol Prospective Randomized Cumulative Survival (COPERNICUS) Study Group. Effect of carvedilol on the morbidity of patients with severe chronic heart failure: results of the carvedilol prospective randomized cumulative survival (COPERNICUS) study. Circulation. 2002;106(17):2194-2199.

36. Digitalis Investigation Group. The effect of digoxin on mortality and morbidity in patients with heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1997;336(8):525-533.

37. Edelmann F, Wachter R, Schmidt AG, et al; Aldo-DHF Investigators. Effect of spironolactone on diastolic function and exercise capacity in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: the Aldo-DHF randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2013;309(8):781-791.

CE/CME No: CR-1805

PROGRAM OVERVIEW

Earn credit by reading this article and successfully completing the posttest and evaluation. Successful completion is defined as a cumulative score of at least 70% correct.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

• Develop an understanding of the classification of heart failure and its associated signs and symptoms.

• Describe clinical findings of heart failure from the physical exam.

• Understand the utility of laboratory and imaging studies for diagnosis of heart failure and its underlying causes.

• Demonstrate knowledge of nonpharmacotherapeutic and pharmacotherapeutic options for managing heart failure.

FACULTY

Michael Roscoe is Chair/Program Director and Associate Professor, Andrew Lampkins is Associate Professor, Sean Harper is Assistant Professor, and Gina Niemeier is Associate Program Director and Assistant Professor, in the PA Department at the University of Evansville in Indiana.

The authors have no financial relationships to disclose.

ACCREDITATION STATEMENT

This program has been reviewed and is approved for a maximum of 1.0 hour of American Academy of Physician Assistants (AAPA) Category 1 CME credit by the Physician Assistant Review Panel. [NPs: Both ANCC and the AANP Certification Program recognize AAPA as an approved provider of Category 1 credit.] Approval is valid through April 30, 2019.

Article begins on next page >>

Heart failure is a complex syndrome with a spectrum of signs and symptoms that range from asymptomatic to terminal. This variability of presentation, paired with the irreversibility of the process, make it both difficult and critical to identify this syndrome early to prevent progression. Here is an overview of the classification and common presentations of heart failure, as well as a guide to diagnostic modalities and treatment options.

Heart failure (HF) is a complex syndrome, not a specific disease; it is always associated with an underlying cause. Hypertension and coronary artery disease are the two most common causes in all age groups, but a number of other conditions—valvular disease, unrecognized obstructive sleep apnea, obesity, chronic kidney disease, anemia, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, and atrial fibrillation—have been identified as secondary causes.1-3

Often, however, clinicians do not identify HF until the syndrome reaches an advanced stage—at which point, the damage is irreversible and pharmacotherapeutic management is limited to control of signs and symptoms. The ramifications are concerning, since HF has achieved near-epidemic scope in the United States. An estimated 5.7 million Americans ages 20 and older have HF; prevalence is projected to increase by 46% between 2012 and 2030—resulting in more than 8 million affected individuals (ages 18 and older).4,5 More than 1 million patients are discharged from the hospital annually with a primary diagnosis of HF.4 And in 2013, one in nine death certificates in the US mentioned HF.4

Most cases of HF are managed in primary care. Established, evidence-based therapies should be implemented in the outpatient setting when possible, as early in the course as possible. Referral to a cardiologist is needed when the underlying cause of HF remains undetermined, or when specialized treatment is required.

CLASSIFICATION OF HF

The two most widely recognized classification systems for HF are those of the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) and of the New York Heart Association (NYHA). Both focus on one-year mortality. The stages of the ACC/AHA system (A to D) are based on worsening of both structural heart disease and clinical symptoms of HF. The NYHA designations (Class I to IV) are based on the functional capability associated with physical activity. Both systems are outlined in Table 1.3,6,7

While these systems are used to “stage” HF, there are several ways the syndrome is classified in the medical literature. For example, HF can be described by

- Anatomy (left- or right-sided)

- Physiology (dilated and hypertrophic)

- Course (chronic or acute heart failure [cardiogenic shock])

- Output (high- or low-output failure)

- Ejection fraction (reduced or preserved)

- Pressure phase (systolic and diastolic).

All these classifications have merit; however, this article will attempt to simplify the approach to patients with HF and focus on systolic HF, defined as a reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), and diastolic HF, defined as a preserved LVEF. Although the common perception of HF among clinicians—and thus the traditional diagnostic focus—is reduced LVEF (systolic HF), preserved LVEF (diastolic HF) in fact represents approximately 50% of cases.1 Diastolic HF is estimated to be increasing in prevalence and is expected to become the more common phenotype.8

Continue to: SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Heart failure is characterized by a constellation of signs and symptoms of pulmonary and/or systemic venous congestion caused by impaired ability of the heart to fill with or eject blood in proportion to the metabolic needs of the body.1 Manifestations include fatigue, dyspnea, fluid retention, and cachexia, and patients can present anywhere on the spectrum—from asymptomatic at rest to severely symptomatic.

Symptoms

In both reduced LVEF and preserved LVEF HF, common early symptoms include dyspnea and fatigue on exertion, with or without some degree of lower-extremity swelling.2 Lack of treatment and disease progression increase symptom severity—to the extent that dyspnea and fatigue start to occur at rest. Reviewing the anatomic classifications/findings of HF facilitates understanding of the clinical symptoms.

Right HF. Right ventricular dysfunction is rarely found in isolation; when symptoms are present, further evaluation of the left ventricle and the pulmonary system (to look for cor pulmonale) is warranted. Right HF is associated with an inability to manage venous return and move volume into the pulmonary circuit. This produces the predominant symptom of fluid retention. Peripheral edema is a cardinal symptom of right HF; edema can also present systemically, mostly as hepatic congestion or general gastrointestinal complaints resulting from impaired gastrointestinal perfusion.9

Left HF. Left ventricular dysfunction is the more common anatomic finding in HF and is often generalized to represent all cases. The dysfunction can be found in isolation and is actually the leading cause of right HF. In left HF (regardless of etiology), the heart does not produce enough “forward” pressure (ie, cannot pump or fill with enough blood) for the cardiovascular system to remain in balance. Thus, “back” pressure into the pulmonary circuit develops.

The combination of insufficient systemic perfusion capability with a dysfunctional left pump means that the most common symptom in all cases of left HF is shortness of breath—specifically, exertional dyspnea. Dyspnea can progress to orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, and, finally, dyspnea at rest. Patients often present with a cough that is worse while lying down and that can be nonproductive or productive, depending on volume status.9,10

Signs

Vital signs range from normal to indicative of shock. Increased sympathetic nervous system activity is common; this may manifest as coldness of the extremities and diaphoresis. Keep in mind that HF is a clinical diagnosis: The physical examination, focusing on peripheral signs, is key in all HF patients for both diagnosis and management.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

The physical exam includes the heart, neck, lungs, abdomen, and extremities. The cardiac exam includes evaluation for hypertrophy, by palpating for the point of maximum impulse to assess for lifts, heaves, valvular disease, and S3 and S4 sounds. Respiratory, abdominal, and extremity exams all focus on the evaluation of fluid status and edema.

A key, often underutilized measurement is jugular venous pressure (JVP). Elevated JVP has been identified as the most specific sign of fluid overload in HF and the most important physical finding in the initial and subsequent examinations of a patient with HF.11 (For good reason, clinicians who treat patients with HF must be able to recognize volume overload and hypovolemia; euvolemia allows patients to remain symptom-free and makes it possible to initiate life-prolonging therapy, which will be discussed in the Treatment section.2) JVP is an indirect measure of pressure within the right side of the heart (central venous pressure).

Most texts on performing the physical exam recommend measuring JVP using the right internal jugular vein. However, use of the internal jugular vein is limiting in HF patients, because it is covered by the sternocleidomastoid muscle for most of its course in the neck and visible only in a small triangle between the two heads in the root of the neck (see Figure). Conversely, the external jugular veins are subcutaneous along their entire course and pulsations are easily visible—but superficial and prone to external pressure and internal occlusion. A nonpulsatile, distended jugular vein should not be used to estimate venous pressure.2

What, then, is the best method? Vinayak et al evaluated the comparative effectiveness of the internal and external jugular veins for detection of central venous pressure. They found that the external jugular vein is easier to visualize and has excellent reliability for determining low and high venous pressures.12

The process for estimating JVP is the same regardless of which jugular vein (internal or external) is used. The technique is described by Bickley in Bates’ Guide to Physical Examination and History Taking:

The patient lies supine and at an angle between 30° and 45°. Turn the head slightly, and with tangential lighting, identify the external and internal jugular veins. Identify the highest point of pulsation in the right jugular vein and extend a long rectangular object or card horizontally from this point and a centimeter ruler vertically from the sternal angle, making an exact right angle. Measure the vertical distance (in centimeters) above the sternal angle where the horizontal object crosses the ruler and add this distance to 4 cm. Measurements of > 3-4 cm above the sternal angle or > 8 cm in total distance are considered elevated.13

Continue to: DIAGNOSTIC AND SCREENING TESTS

DIAGNOSTIC AND SCREENING TESTS

Several diagnostic studies can identify HF or elucidate underlying causes. However, not all tests yield sufficient information for diagnosis—and commonly held “maxims” about findings that definitively rule in or out the diagnosis have been confounded by the available evidence.

Laboratory tests. The lab parameter most associated with HF is brain natriuretic peptide (BNP). Natriuretic peptides are produced primarily within the heart and released into the circulation in response to increased wall tension.14 In contrast to atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP), BNP is secreted not only from the atria but also from the ventricles, especially in patients with HF.15

Circulating concentrations of several cardiac natriuretic peptides—including ANP, BNP, and the two peptides’ N-terminal pro-hormones (N-terminal pro-atrial natriuretic peptide and N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide, respectively) are elevated in both symptomatic and asymptomatic patients with left ventricular dysfunction.16 These levels are generally elevated for both systolic and diastolic HF. However, in one study, as many as 30% of diastolic HF patients had a low BNP level, despite signs and symptoms of HF and significantly elevated left ventricular filling pressures, as determined by invasive hemodynamic monitoring.17 Comorbid obesity is associated with low levels of natriuretic peptides.18

Additional lab tests can provide information about underlying causes of HF or reveal contraindications to certain treatment options (to be discussed in the Treatment section). A complete blood count (CBC) might reveal anemia, which can cause or aggravate HF, and which is an important consideration in management because of its association with decreased renal function, hemodilution, and proinflammatory cytokines. Leukocytosis can signal underlying infection. A troponin assay is helpful for ruling out acute MI as a cause of worsening HF in acute cases. Thyroid function tests and iron studies can be considered to rule out secondary causes of HF.

A serum electrolyte screen should be ordered; results are usually within normal ranges. Hyponatremia is an indicator of activation of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS) and may be seen in the context of prolonged salt restriction and diuretic therapy. Hyperkalemia and hypokalemia are also prevalent in HF; both are limiting factors for some treatment options. A low sodium level is often the result of increased congestion and release of vasopressin; a level of ≤ 135 mEq/L predicts a poorer outcome.

Kidney function tests can determine whether HF is associated with impaired kidney function, secondary to poor renal perfusion. Poor renal function may limit treatment options. Patients with severe HF, particularly those receiving a high dosage of a diuretic for a long period, may have elevated levels of blood urea nitrogen and creatinine, indicating renal insufficiency.

Electrocardiography and chest radiography. ECGs and chest radiographs are noninvasive tests that have been used widely in the diagnosis of HF. They might indicate an underlying cause (eg, acute MI, ischemia, secondary arrhythmia) but are often nonspecific—and thus may be unhelpful in the diagnosis and treatment of HF.

The most common ECG findings in HF are nonspecific ST-T wave abnormalities.19 Other findings often consist of low-voltage left ventricular hypertrophy, conduction defects, and repolarization changes. With chest radiography, primary findings in HF include pulmonary edema—seen as perivascular edema, peribronchial cuffing, perihilar haze, interstitial edema (Kerley B, or septal, lines), and alveolar fluid—and pleural effusion.19,20

For both these modalities, however, there are commonly held conceptions that particular findings rule out HF—which has been disproven by Fonseca and colleagues.19 Because most patients with HF have an abnormal ECG, some studies have proposed that a normal ECG virtually rules out left ventricular systolic dysfunction.20 Evaluating the value of ECG in HF diagnosis, Fonseca et al found that about 85% of patients with an abnormal ECG had HF—but so did 30% of patients with a normal ECG. They concluded that, if used alone, ECG could have missed as many as 25% of patients with HF.19

Likewise, it has been suggested that a patient cannot have HF if heart size is normal on a chest radiograph.20 Fonseca et al found that cardiac enlargement, while the most informative radiologic measurement in HF, was present in only half of patients with HF.19 About 57% of patients who had an abnormal chest radiograph had HF, but so did about 40% of those who had a normal chest radiograph.19 Therefore, abnormal chest radiograph for identification of HF had an estimated sensitivity of 57%, a specificity of 78%, positive predictive value of 50%, and negative predictive value of 83%.19 The conclusion: Caution should be taken regarding the use of chest radiography in isolation to make a diagnosis of HF.

Echocardiography. The most useful test in evaluating HF is the echocardiogram, because it can distinguish between HF with and without preserved left ventricular systolic function. This is critical: The most clinically relevant classification of HF differentiates systolic and diastolic HF, based on LVEF.2 This determination has both prognostic and therapeutic implications.21

Echocardiography is widely available, safe, and noninvasive. The “echo” can identify the size of the atria and ventricles, valve function and dysfunction, and any associated shunting. Pericardial effusions and heart wall-motion abnormalities (for example, an old MI) are also easily identified.9

A normal ejection fraction does not rule out HF. Therefore, assessment of LVEF should not be considered until after a clinical diagnosis has been made, because more than half of HF patients have a normal LVEF—evidence that can confound the diagnostic process.2

Continue to: TREATMENT OF HEART FAILURE WITH REDUCED LVEF

TREATMENT OF HEART FAILURE WITH REDUCED LVEF

The body’s neurohormonal system, including the RAAS and the sympathetic nervous system, is activated to compensate for the insufficient cardiac performance found in HF. However, activation of these systems contributes to worsening HF, deterioration of quality of life, and poor outcomes.22 Therefore, therapies that suppress these responses can reduce the progression of HF.

Treatment of HF is generally divided into symptom-relieving treatment and disease-modifying/life-prolonging treatment.1 Symptom relief is similar in both systolic and diastolic HF. However, most evidence-based, disease-modifying treatment focuses on systolic HF; guidelines for disease-modifying treatment of diastolic HF are minimal.1

Treatment of reversible causes

Since HF is caused by something else, the primary focus of management is addressing underlying causes. The primary goal is to relieve symptoms while improving functional status—which should lead to a decrease in hospitalization and premature death.

The first step is to evaluate patients’ use of medications that can contribute to a worsening of HF.9 The most common offending medications are calcium-channel blockers with negative inotropy (non-dihydropyridine calcium-channel blockers, eg, verapamil and diltiazem); some antiarrhythmic drugs (eg, amiodarone); thiazolidinediones (glitazones); and NSAIDs.9 If identified as a possible contributor to HF symptoms, these agents should be stopped (if possible) or replaced.

Nonpharmacotherapy

Effective counseling and education of patients with HF may help with long-term adherence to treatment plans. Patients can be taught to monitor their weight at home and to adjust the dosage of diuretics as advised: A sudden increase in weight (> 2 kg in one to three d), for example, should alert a patient to alter treatment or seek advice.23

Diet modification is a multifactorial recommendation. Proper nutrition is critical because HF patients are at increased risk for malnutrition due to poor appetite, malabsorption, and increased nutritional requirements.23 Weight reduction in obese patients helps reduce cardiac workload. Patients should be placed on salt restriction (2 to 2.6 g/d of sodium).9,23

Exercise has been shown to relieve symptoms, provide a greater sense of well-being, and improve functional capacity. It does not, however, result in obvious improvement in cardiac function.22

Alcohol consumption should be restricted because of the myocardial depressant properties of alcohol and its direct toxic effect on the myocardium.22 Smoking should be discouraged because it has a direct effect on coronary artery disease.

Influenza and pneumococcal vaccination should be considered in all patients with HF.23 Heart failure predisposes patients to, and can be exacerbated by, pulmonary infection and exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Evaluation and management of obstructive sleep apnea should be performed. Sleep-disordered breathing, an umbrella term that covers obstructive and central sleep apneas, has been found to increase the risk for poor prognosis in HF.24 All patients with HF should be tested for obstructive sleep apnea because, often, only the patient’s bed partner is aware of disordered sleep. For unknown reasons, patients with HF do not report subjective sleepiness.25

Continue to: Pharmacotherapy

Pharmacotherapy

Diuretics have not been found to have benefit for reducing early mortality but are the most common agents used for symptomatic relief of sodium and water retention.26 In fact, few patients with signs and symptoms of fluid retention can be managed without a diuretic.9 Caution must be observed, however, because excessive diuresis can lead to electrolyte imbalance and neurohormonal activation.

Treating mild fluid retention with a thiazide diuretic (hydrochlorothiazide, metolazone, or chlorthalidone) is often sufficient (see Table 2 for dosing and other information on these and other drugs for treating HF).9 Thiazide diuretics are dependent on the glomerular filtration rate and are ineffective when it falls below 30-40 mL/min. Adverse reactions to diuretics include hypokalemia, dehydration (intravascular volume depletion) with prerenal azotemia, skin rash, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, hyperglycemia, hyperuricemia, and hepatic dysfunction.

In cases of moderate or severe HF, or failure of thiazide diuretics to relieve mild symptoms, an oral loop diuretic (furosemide, bumetanide, or torsemide; see Table 2 for dosing) can be used if kidney function is preserved.9 These agents are best administered in two or more divided doses. Major adverse reactions are similar to those of thiazide diuretics, plus ototoxicity. Special caution must be used when a loop diuretic is co-administered with digitalis because the combination can cause significant hypokalemia.9

A potassium-sparing diuretic (triamterene or amiloride; see Table 2) can be used in combination with thiazide and loop diuretics.9 The location of their action is at the distal tubule, but diuretic potency is mild. Potassium-sparing agents can minimize hypokalemia induced by other diuretics. Adverse effects include hyperkalemia, kidney dysfunction, and gastrointestinal symptoms.

The aldosterone-receptor antagonists spironolactone and eplerenone are specific inhibitors of aldosterone, an effect that has been shown to improve clinical outcomes.9 Aldosterone-receptor antagonists are indicated for patients with NYHA class II-IV HF who have LVEF ≤ 35% or those with a history of acute MI, LVEF < 40%, and symptoms of HF.27 In these patients, a reduction in mortality and relative risk has been demonstrated with the use of aldosterone-receptor antagonists, unrelated to their role in diuresis. The adverse effect profile of spironolactone includes gynecomastia.

Continue to: Inhibitors of the RAAS

Inhibitors of the RAAS. As noted, the RAAS plays a key role during the development and worsening of HF.22

Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE inhibitors) constitute the cornerstone of modern HF pharmacotherapy and have compelling evidence of survival benefit.28 These agents (captopril, enalapril, lisinopril, and ramipril; see Table 2 for dosing) have been shown to be effective therapy for HF and post-MI left ventricular dysfunction.29 They reduce early mortality by approximately 20% in symptomatic HF and can prevent hospitalization, increase exercise tolerance, and reduce adverse events (symptoms).9

Because of these benefits, ACE inhibitors should be firstline therapy in all HF patients with left ventricular dysfunction. They are usually used in combination with a diuretic. In addition, ACE inhibitors should be used in patients with reduced LVEF, even if they are asymptomatic, because these agents prevent progression to clinical HF.

Since ACE inhibitors carry the risk for severe hypotension, caution must be used, especially during treatment initiation. Patients whose systolic blood pressure is < 100 mm Hg, or who are hypovolemic, should be started at a low dosage (captopril, 6.25 mg tid; enalapril, 2.5 mg/d; or other equivalent ACE inhibitor dose); for other patients, these dosages can be doubled at initiation.9 Within days of initiation, but no longer than two weeks later, patients should be screened for hypotension and have both kidney function and potassium levels monitored. The dosage of ACE inhibitors should be increased over one to three months to an effective dosage (eg, captopril, 25 mg tid; enalapril, 10 mg bid; ramipril, 10 mg/d; and lisinopril, 20 mg/d, or other equivalent ACE inhibitor dose).9

Asymptomatic hypotension is not a contraindication to continuation or uptitration of the dosage of ACE inhibitors. Patients may also experience an increase in the serum creatinine or potassium level; likewise, this should not prompt a change in dosage if the elevated level stabilizes. The most common adverse effects of ACE inhibitors are dizziness and cough.9

Angiotensin II-receptor blockers (ARBs) have been shown to be as effective as ACE inhibitors for the management of hypertension, congestive HF, and chronic renal failure.30 ARBs decrease the adverse effects of angiotensin II, but do not have the same effects that ACE inhibitors do on other pathways found in HF (specifically, on bradykinin, prostaglandins, and nitric oxide).29 Candesartan and valsartan have been shown to have benefits in HF and are an equivalent alternative to ACE inhibitors; they are often used when a patient cannot tolerate an ACE inhibitor. Because ARBs and ACE inhibitors affect the RAAS at different points in the pathway, there is a theoretical basis for ARB and ACE inhibitor combination therapy; in clinical studies to date, however, the combination has shown no beneficial effect and rather was associated with more adverse effects.29

Neprilysin inhibitor. Recently, the combination of the neprilysin inhibitor sacubitril and an ARB, valsartan, has surfaced as an alternative to ACE inhibitor or single-agent ARB therapy.31,32 Inhibition of the enzyme neprilysin results in an increase in levels of endogenous vasoactive peptides (eg, natriuretic peptides and bradykinin), which may benefit hemodynamics in patients with HF. However, use of an ARB in combination with sacubitril is necessary to counteract the increase in angiotensin II levels that also results from inhibition of neprilysin.33

Sacubitril–valsartan is typically reserved for patients with mild-to-moderate HF who have either an elevated BNP (≥ 50 pg/mL) or an HF-related hospitalization within the past year. Upon transitioning from an ACE inhibitor (or single-agent ARB), a 36-hour washout period must be observed before starting sacubitril–valsartan to minimize the risk for angioedema. Because therapy with sacubitril–valsartan leads directly to an elevation in the BNP level, using the level of N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide—which is not degraded by neprilysin—to monitor disease progression is recommended.34

ß-

Initiation of ß-blockers in stable patients can cause general deterioration; initiation must therefore be done gradually:

- Carvedilol, initiated at 3.125 mg bid, can be increased to 6.25 mg, then 12.5 mg, and then 25 mg, all bid, at intervals of approximately two weeks

- Sustained-release metoprolol can be started at 12.5 mg/d or 25 mg/d and doubled at two weeks to a target of 200 mg/d

- Bisoprolol, initiated at 1.25 mg/d, can be increased incrementally to 2.5 mg/d, 3.75 mg/d, 5 mg/d, 7.5 mg/d, or 10 mg/d at one-to-four-week intervals.9

Patients taking ß-blockers need to monitor their weight at home as an indicator of fluid retention. If HF becomes worse, an increase in the dosage of the accompanying diuretic, a delay in the increase of the ß-blocker, or downward adjustment of the ß-blocker is usually sufficient.

Continue to: Digitalis glycoside

Digitalis glycoside. Digoxin has been shown to relieve the symptoms of HF, decrease the risk for hospitalization, and increase exercise tolerance; however, it has not been shown to offer a mortality benefit.36 Digoxin should be considered for patients who remain symptomatic when taking a diuretic and an ACE inhibitor and for patients who are also in atrial fibrillation and need rate control.

Digoxin is cleared almost entirely by the kidneys and therefore must be used with care in patients with renal dysfunction. Patients usually can be started on the expected maintenance dosage (0.125-0.25 mg/d). An oral loading dose of 0.75-1.25 mg over 24 to 48 hours can be used if an early effect is needed.9

Digoxin can induce ventricular arrhythmias (especially in a setting of hypokalemia and ischemia) and is sensitive to other medications that can drastically increase its level—most notably, amiodarone, quinidine, propafenone, and verapamil.9 The digoxin blood level should be measured every seven to 14 days until a maintenance dosage is established, and again whenever there is a change in medication or kidney function. The optimum serum level is 0.7-1.2 ng/mL; toxicity is not usually seen at < 1.8 ng/mL.9

Hydralazine and nitrates. The combination of hydralazine and isosorbide dinitrate has been shown to improve outcomes in African-American patients with HF, but efficacy is less well-established in this population than for ACE inhibitor and ARB therapy.9 This combination can be considered in patients who are unable to tolerate ACE inhibitor or ARB therapy. It can also be considered in those who have persistent symptoms despite treatment with a ß-blocker, ACE inhibitor, or aldosterone antagonist.9

Intravenous nitrates are used primarily for acute HF, especially when accompanied by hypertension or myocardial ischemia. The starting dosage for nitroglycerin is approximately 10 μcg/min, titrated upward by 10-20 μcg/min to a maximum of 200 μcg/min. Isosorbide dinitrate (20-40 mg tid) and nitroglycerine ointment 2% (1.4 in applied every six to eight hours [although generally reserved for inpatient therapy]) are equally effective.9 Adverse effects that may limit the use of these agents are headache and hypotension. Patients also develop tolerance for nitrates, which can be mitigated if a daily 8-to-12–hour nitrate-free period is instituted.9

TREATMENT OF HEART FAILURE WITH PRESERVED LVEF

Treatment options for patients with preserved LVEF (diastolic HF) are not as clear as those for patients with reduced LVEF (systolic HF). No traditional therapies (ACE inhibitors, ARBs, ß-blockers, digoxin) have been shown to improve survival in this population, although a recent study on the effects of spironolactone in diastolic HF did show some improvement of diastolic dysfunction without adverse effects.17,37 In the absense of clear evidence-based therapies, treatment focuses on managing comorbidities, addressing reversible causes, and alleviating fluid overload with a diuretic.9,17

Diuretic therapy is critical to control fluid overload; regimens are similar to those for HF with reduced LVEF. ACE inhibitors and ARBs have not been shown to improve outcomes in this population but can be used to manage comorbid hypertension. Spironolactone has also not been shown to improve outcomes in patients with diastolic HF.9

The principal conditions that can lead to HF with preserved LVEF are hypertension, pericardial disease, and atrial tachycardia. Tachycardia is associated with overall shorter diastolic filling time; controlling an accelerated heart rate, therefore, is theorized to be an important therapeutic goal.9 Other disease states, including diabetes mellitus, sleep-disordered breathing, obesity, and chronic kidney disease, can all lead to HF with preserved LVEF.

CONCLUSION

Managing HF today requires an “upstream” model of care, by which providers consider the diagnosis/syndrome of HF in the asymptomatic patient with risk factors (Stage A/Class I and Stage B/Class II). Perhaps a better way to state this is that providers must change their approach from ruling-in to ruling-out HF. Any person in whom a decrease in activity level, mild shortness of breath, or edema are observed, and who has known risk factors, should be considered to have HF until proven otherwise.

Because of the wide variability in the underlying causes of HF, providers must be dynamic in both their clinical approach and their treatment plans to optimize care for the individual patient. Finally, providers must also take note of the increasing prevalence of diastolic HF and, again, focus on early diagnosis.

CE/CME No: CR-1805

PROGRAM OVERVIEW

Earn credit by reading this article and successfully completing the posttest and evaluation. Successful completion is defined as a cumulative score of at least 70% correct.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

• Develop an understanding of the classification of heart failure and its associated signs and symptoms.

• Describe clinical findings of heart failure from the physical exam.

• Understand the utility of laboratory and imaging studies for diagnosis of heart failure and its underlying causes.

• Demonstrate knowledge of nonpharmacotherapeutic and pharmacotherapeutic options for managing heart failure.

FACULTY

Michael Roscoe is Chair/Program Director and Associate Professor, Andrew Lampkins is Associate Professor, Sean Harper is Assistant Professor, and Gina Niemeier is Associate Program Director and Assistant Professor, in the PA Department at the University of Evansville in Indiana.

The authors have no financial relationships to disclose.

ACCREDITATION STATEMENT

This program has been reviewed and is approved for a maximum of 1.0 hour of American Academy of Physician Assistants (AAPA) Category 1 CME credit by the Physician Assistant Review Panel. [NPs: Both ANCC and the AANP Certification Program recognize AAPA as an approved provider of Category 1 credit.] Approval is valid through April 30, 2019.

Article begins on next page >>

Heart failure is a complex syndrome with a spectrum of signs and symptoms that range from asymptomatic to terminal. This variability of presentation, paired with the irreversibility of the process, make it both difficult and critical to identify this syndrome early to prevent progression. Here is an overview of the classification and common presentations of heart failure, as well as a guide to diagnostic modalities and treatment options.

Heart failure (HF) is a complex syndrome, not a specific disease; it is always associated with an underlying cause. Hypertension and coronary artery disease are the two most common causes in all age groups, but a number of other conditions—valvular disease, unrecognized obstructive sleep apnea, obesity, chronic kidney disease, anemia, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, and atrial fibrillation—have been identified as secondary causes.1-3

Often, however, clinicians do not identify HF until the syndrome reaches an advanced stage—at which point, the damage is irreversible and pharmacotherapeutic management is limited to control of signs and symptoms. The ramifications are concerning, since HF has achieved near-epidemic scope in the United States. An estimated 5.7 million Americans ages 20 and older have HF; prevalence is projected to increase by 46% between 2012 and 2030—resulting in more than 8 million affected individuals (ages 18 and older).4,5 More than 1 million patients are discharged from the hospital annually with a primary diagnosis of HF.4 And in 2013, one in nine death certificates in the US mentioned HF.4

Most cases of HF are managed in primary care. Established, evidence-based therapies should be implemented in the outpatient setting when possible, as early in the course as possible. Referral to a cardiologist is needed when the underlying cause of HF remains undetermined, or when specialized treatment is required.

CLASSIFICATION OF HF

The two most widely recognized classification systems for HF are those of the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) and of the New York Heart Association (NYHA). Both focus on one-year mortality. The stages of the ACC/AHA system (A to D) are based on worsening of both structural heart disease and clinical symptoms of HF. The NYHA designations (Class I to IV) are based on the functional capability associated with physical activity. Both systems are outlined in Table 1.3,6,7

While these systems are used to “stage” HF, there are several ways the syndrome is classified in the medical literature. For example, HF can be described by

- Anatomy (left- or right-sided)

- Physiology (dilated and hypertrophic)

- Course (chronic or acute heart failure [cardiogenic shock])

- Output (high- or low-output failure)

- Ejection fraction (reduced or preserved)