User login

Acute-onset quadriplegia with hyperreflexia

A 79-year-old man presented with sudden-onset bilateral weakness in the lower and upper extremities that had started 6 hours earlier. He reported no vision disturbances or urinary incontinence. He was afebrile, with a blood pressure of 148/94 mm Hg, heart rate 98 bpm, and oxygen saturation of 95% on room air.

Physical examination revealed quadriplegia with hyperreflexia, sustained ankle clonus, and bilateral Babinski reflex, as well as spontaneous adductor and extensor spasms of the lower extremities.

Funduscopy was negative for optic neuritis. Results of a complete blood cell count and renal and liver function testing were within normal limits.

The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit. Methylprednisolone 1 g was given intravenously once daily for 5 days, with plasma exchange every other day for 5 sessions. A workup for neoplastic, autoimmune, and infectious disease was negative, as was testing for serum aquaporin-4 antibody (ie, neuromyelitis optica immunoglobulin G antibody).

Over the course of 7 days, the patient’s motor strength improved, and he was able to walk without assistance. Steroid therapy was tapered, and he was prescribed rituximab to prevent recurrence.

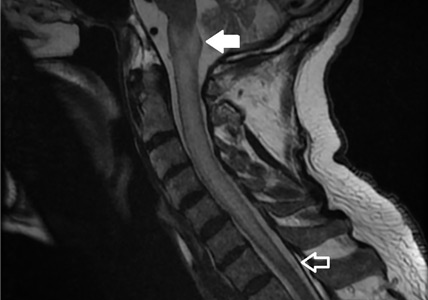

LONGITUDINALLY EXTENSIVE TRANSVERSE MYELITIS

A subtype of transverse myelitis, LETM is defined by partial or complete spinal cord dysfunction due to a lesion extending 3 or more vertebrae as confirmed on MRI. The clinical presentation can include paraparesis, sensory disturbances, and gait, bladder, bowel, or sexual dysfunction.1 Identifying the cause requires an extensive workup, as the differential diagnosis includes a wide range of conditions2:

- Autoimmune disorders such as Behçet disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, and Sjögren syndrome

- Infectious disorders such as syphilis, tuberculosis, and viral and parasitic infections

- Demyelinating disorders such as multiple sclerosis and neuromyelitis optica

- Neoplastic conditions such as intramedullary metastasis and lymphoma

- Paraneoplastic syndromes.

In our patient, the evaluation did not identify a specific underlying condition, and testing for serum aquaporin-4 antibody was negative. Therefore, the LETM was ruled an isolated idiopathic episode.

Idiopathic seronegative LETM has been associated with fewer recurrences than seropositive LETM.3 Management consists of high-dose intravenous steroids and plasma exchange. Rituximab can be used to prevent recurrence.4

- Trebst C, Raab P, Voss EV, et al. Longitudinal extensive transverse myelitis—it’s not all neuromyelitis optica. Nat Rev Neurol 2011; 7(12):688–698. doi:10.1038/nrneurol.2011.176

- Kim SM, Kim SJ, Lee HJ, Kuroda H, Palace J, Fujihara K. Differential diagnosis of neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders. Ther Adv Neurol Disord 2017; 10(7):265–289. doi:10.1177/1756285617709723

- Kitley J, Leite MI, Küker W, et al. Longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis with and without aquaporin 4 antibodies. JAMA Neurol 2013; 70(11):1375–1381. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.3890

- Tobin WO, Weinshenker BG, Lucchinetti CF. Longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis. Curr Opin Neurol 2014; 27(3):279–289. doi:10.1097/WCO.0000000000000093

A 79-year-old man presented with sudden-onset bilateral weakness in the lower and upper extremities that had started 6 hours earlier. He reported no vision disturbances or urinary incontinence. He was afebrile, with a blood pressure of 148/94 mm Hg, heart rate 98 bpm, and oxygen saturation of 95% on room air.

Physical examination revealed quadriplegia with hyperreflexia, sustained ankle clonus, and bilateral Babinski reflex, as well as spontaneous adductor and extensor spasms of the lower extremities.

Funduscopy was negative for optic neuritis. Results of a complete blood cell count and renal and liver function testing were within normal limits.

The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit. Methylprednisolone 1 g was given intravenously once daily for 5 days, with plasma exchange every other day for 5 sessions. A workup for neoplastic, autoimmune, and infectious disease was negative, as was testing for serum aquaporin-4 antibody (ie, neuromyelitis optica immunoglobulin G antibody).

Over the course of 7 days, the patient’s motor strength improved, and he was able to walk without assistance. Steroid therapy was tapered, and he was prescribed rituximab to prevent recurrence.

LONGITUDINALLY EXTENSIVE TRANSVERSE MYELITIS

A subtype of transverse myelitis, LETM is defined by partial or complete spinal cord dysfunction due to a lesion extending 3 or more vertebrae as confirmed on MRI. The clinical presentation can include paraparesis, sensory disturbances, and gait, bladder, bowel, or sexual dysfunction.1 Identifying the cause requires an extensive workup, as the differential diagnosis includes a wide range of conditions2:

- Autoimmune disorders such as Behçet disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, and Sjögren syndrome

- Infectious disorders such as syphilis, tuberculosis, and viral and parasitic infections

- Demyelinating disorders such as multiple sclerosis and neuromyelitis optica

- Neoplastic conditions such as intramedullary metastasis and lymphoma

- Paraneoplastic syndromes.

In our patient, the evaluation did not identify a specific underlying condition, and testing for serum aquaporin-4 antibody was negative. Therefore, the LETM was ruled an isolated idiopathic episode.

Idiopathic seronegative LETM has been associated with fewer recurrences than seropositive LETM.3 Management consists of high-dose intravenous steroids and plasma exchange. Rituximab can be used to prevent recurrence.4

A 79-year-old man presented with sudden-onset bilateral weakness in the lower and upper extremities that had started 6 hours earlier. He reported no vision disturbances or urinary incontinence. He was afebrile, with a blood pressure of 148/94 mm Hg, heart rate 98 bpm, and oxygen saturation of 95% on room air.

Physical examination revealed quadriplegia with hyperreflexia, sustained ankle clonus, and bilateral Babinski reflex, as well as spontaneous adductor and extensor spasms of the lower extremities.

Funduscopy was negative for optic neuritis. Results of a complete blood cell count and renal and liver function testing were within normal limits.

The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit. Methylprednisolone 1 g was given intravenously once daily for 5 days, with plasma exchange every other day for 5 sessions. A workup for neoplastic, autoimmune, and infectious disease was negative, as was testing for serum aquaporin-4 antibody (ie, neuromyelitis optica immunoglobulin G antibody).

Over the course of 7 days, the patient’s motor strength improved, and he was able to walk without assistance. Steroid therapy was tapered, and he was prescribed rituximab to prevent recurrence.

LONGITUDINALLY EXTENSIVE TRANSVERSE MYELITIS

A subtype of transverse myelitis, LETM is defined by partial or complete spinal cord dysfunction due to a lesion extending 3 or more vertebrae as confirmed on MRI. The clinical presentation can include paraparesis, sensory disturbances, and gait, bladder, bowel, or sexual dysfunction.1 Identifying the cause requires an extensive workup, as the differential diagnosis includes a wide range of conditions2:

- Autoimmune disorders such as Behçet disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, and Sjögren syndrome

- Infectious disorders such as syphilis, tuberculosis, and viral and parasitic infections

- Demyelinating disorders such as multiple sclerosis and neuromyelitis optica

- Neoplastic conditions such as intramedullary metastasis and lymphoma

- Paraneoplastic syndromes.

In our patient, the evaluation did not identify a specific underlying condition, and testing for serum aquaporin-4 antibody was negative. Therefore, the LETM was ruled an isolated idiopathic episode.

Idiopathic seronegative LETM has been associated with fewer recurrences than seropositive LETM.3 Management consists of high-dose intravenous steroids and plasma exchange. Rituximab can be used to prevent recurrence.4

- Trebst C, Raab P, Voss EV, et al. Longitudinal extensive transverse myelitis—it’s not all neuromyelitis optica. Nat Rev Neurol 2011; 7(12):688–698. doi:10.1038/nrneurol.2011.176

- Kim SM, Kim SJ, Lee HJ, Kuroda H, Palace J, Fujihara K. Differential diagnosis of neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders. Ther Adv Neurol Disord 2017; 10(7):265–289. doi:10.1177/1756285617709723

- Kitley J, Leite MI, Küker W, et al. Longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis with and without aquaporin 4 antibodies. JAMA Neurol 2013; 70(11):1375–1381. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.3890

- Tobin WO, Weinshenker BG, Lucchinetti CF. Longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis. Curr Opin Neurol 2014; 27(3):279–289. doi:10.1097/WCO.0000000000000093

- Trebst C, Raab P, Voss EV, et al. Longitudinal extensive transverse myelitis—it’s not all neuromyelitis optica. Nat Rev Neurol 2011; 7(12):688–698. doi:10.1038/nrneurol.2011.176

- Kim SM, Kim SJ, Lee HJ, Kuroda H, Palace J, Fujihara K. Differential diagnosis of neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders. Ther Adv Neurol Disord 2017; 10(7):265–289. doi:10.1177/1756285617709723

- Kitley J, Leite MI, Küker W, et al. Longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis with and without aquaporin 4 antibodies. JAMA Neurol 2013; 70(11):1375–1381. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.3890

- Tobin WO, Weinshenker BG, Lucchinetti CF. Longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis. Curr Opin Neurol 2014; 27(3):279–289. doi:10.1097/WCO.0000000000000093

Emphysematous cystitis

A 59-year-old woman with a history of chronic kidney disease and atonic bladder was brought to the hospital by emergency medical services. She had fallen in her home 2 days earlier and remained on the floor until neighbors eventually heard her cries and called 911. She complained of abdominal pain and distention along with emesis.

On presentation, she had tachycardia and tachypnea. The examination was notable for pronounced abdominal distention, diminished bowel sounds, and costovertebral angle tenderness.

While laboratory work was being done, the patient’s tachypnea progressed to respiratory distress, and she ultimately required intubation. Vasopressors were started, as the patient was hemodynamically unstable. A Foley catheter was placed, which yielded about 1,100 mL of purulent urine.

Laboratory workup showed:

- Procalcitonin 189 ng/mL (reference range < 2.0 ng/mL)

- White blood cell count 10.7 × 109/L (4.5–10.0)

- Myoglobin 20,000 ng/mL (< 71)

- Serum creatinine 4.8 mg/dL (0.06–1.10).

Urinalysis was positive for infection; blood and urine cultures later were positive for Escherichia coli.

The patient went into shock that was refractory to pressors, culminating in cardiac arrest despite resuscitative measures.

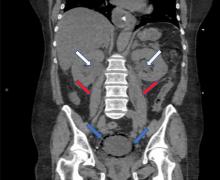

EMPHYSEMATOUS CYSTITIS, A FORM OF URINARY TRACT INFECTION

Emphysematous cystitis is a rare form of complicated urinary tract infection characterized by gas inside the bladder and in the bladder wall. While the exact mechanisms underlying gas formation are not clear, gas-producing pathogens are clearly implicated in severe infection. E coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae are the most common organisms associated with emphysematous cystitis; others include Proteus mirabilis, and Enterobacter and Streptococcus species.1,2

More than 50% of patients with emphysematous cystitis have diabetes mellitus. Other risk factors include bladder outlet obstruction, neurogenic bladder, and female sex.3 The severity of disease ranges from asymptomatic pneumaturia (up to 7% of cases)2 to fulminant emphysematous cystitis, as in our patient.

The clinical presentation of emphysematous cystitis is nonspecific and can range from minimally symptomatic urinary tract infection to acute abdomen and septic shock.4

Some patients present with pneumaturia (the passing of gas through the urethra with micturition). Pneumaturia arises from 3 discrete causes: urologic instrumentation, fistula between the bladder and large or small bowel, and gas-producing bacteria in the bladder (emphysematous cystitis).5 Pneumaturia should always raise the suspicion of emphysematous cystitis.

The diagnosis can be made with either radiographic or computed tomographic evidence of gas within the bladder and bladder wall, in the absence of both bladder fistula and history of iatrogenic pneumaturia. Emphysematous cystitis should prompt urine and blood cultures to direct antimicrobial therapy, as 50% of patients with emphysematous cystitis have concomitant bacteremia.6

Our patient had an elevated serum level of procalcitonin, a marker of bacterial infection. Procalcitonin is a more specific biomarker of bacterial infection than acute-phase reactants such as the erythrocyte sedimentation rate or the C-reactive protein level. Measuring procalcitonin may help physicians make the diagnosis earlier, differentiate infectious from sterile causes of severe systemic inflammation, assess the severity of systemic inflammation caused by bacterial infections, and decide whether to start or discontinue antibiotic therapy.7

Most cases of emphysematous cystitis can be treated with antibiotics, though early diagnosis is crucial to a favorable outcome. Delay in diagnosis may contribute to the 20% mortality rate associated with this condition.6

- Stein JP, Spitz A, Elmajian DA, et al. Bilateral emphysematous pyelonephritis: a case report and review of the literature. Urology 1996; 47(1):129–134. pmid:8560648

- Amano M, Shimizu T. Emphysematous cystitis: a review of the literature. Intern Med 2014; 53(2):79–82. pmid:24429444

- Wang JH. Emphysematous cystitis. Urol Sci 2010; 21(4):185–186. doi:10.1016/S1879-5226(10)60041-3

- Thomas AA, Lane BR, Thomas AZ, Remer EM, Campbell SC, Shoskes DA. Emphysematous cystitis: a review of 135 cases. BJU Int 2007; 100(1):17–20. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.06930.x

- Arthur LM, Johnson HW. Pneumaturia: a case report and review of the literature. J Urol 1948; 60(4):659–665. pmid:18885959

- Grupper M, Kravtsov A, Potasman I. Emphysematous cystitis: illustrative case report and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 2007; 86(1):47–53. doi:10.1097/MD.0b013e3180307c3a

- Lee H. Procalcitonin as a biomarker of infectious diseases. Korean J Intern Med 2013; 28(3):285–291. doi:10.3904/kjim.2013.28.3.285

A 59-year-old woman with a history of chronic kidney disease and atonic bladder was brought to the hospital by emergency medical services. She had fallen in her home 2 days earlier and remained on the floor until neighbors eventually heard her cries and called 911. She complained of abdominal pain and distention along with emesis.

On presentation, she had tachycardia and tachypnea. The examination was notable for pronounced abdominal distention, diminished bowel sounds, and costovertebral angle tenderness.

While laboratory work was being done, the patient’s tachypnea progressed to respiratory distress, and she ultimately required intubation. Vasopressors were started, as the patient was hemodynamically unstable. A Foley catheter was placed, which yielded about 1,100 mL of purulent urine.

Laboratory workup showed:

- Procalcitonin 189 ng/mL (reference range < 2.0 ng/mL)

- White blood cell count 10.7 × 109/L (4.5–10.0)

- Myoglobin 20,000 ng/mL (< 71)

- Serum creatinine 4.8 mg/dL (0.06–1.10).

Urinalysis was positive for infection; blood and urine cultures later were positive for Escherichia coli.

The patient went into shock that was refractory to pressors, culminating in cardiac arrest despite resuscitative measures.

EMPHYSEMATOUS CYSTITIS, A FORM OF URINARY TRACT INFECTION

Emphysematous cystitis is a rare form of complicated urinary tract infection characterized by gas inside the bladder and in the bladder wall. While the exact mechanisms underlying gas formation are not clear, gas-producing pathogens are clearly implicated in severe infection. E coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae are the most common organisms associated with emphysematous cystitis; others include Proteus mirabilis, and Enterobacter and Streptococcus species.1,2

More than 50% of patients with emphysematous cystitis have diabetes mellitus. Other risk factors include bladder outlet obstruction, neurogenic bladder, and female sex.3 The severity of disease ranges from asymptomatic pneumaturia (up to 7% of cases)2 to fulminant emphysematous cystitis, as in our patient.

The clinical presentation of emphysematous cystitis is nonspecific and can range from minimally symptomatic urinary tract infection to acute abdomen and septic shock.4

Some patients present with pneumaturia (the passing of gas through the urethra with micturition). Pneumaturia arises from 3 discrete causes: urologic instrumentation, fistula between the bladder and large or small bowel, and gas-producing bacteria in the bladder (emphysematous cystitis).5 Pneumaturia should always raise the suspicion of emphysematous cystitis.

The diagnosis can be made with either radiographic or computed tomographic evidence of gas within the bladder and bladder wall, in the absence of both bladder fistula and history of iatrogenic pneumaturia. Emphysematous cystitis should prompt urine and blood cultures to direct antimicrobial therapy, as 50% of patients with emphysematous cystitis have concomitant bacteremia.6

Our patient had an elevated serum level of procalcitonin, a marker of bacterial infection. Procalcitonin is a more specific biomarker of bacterial infection than acute-phase reactants such as the erythrocyte sedimentation rate or the C-reactive protein level. Measuring procalcitonin may help physicians make the diagnosis earlier, differentiate infectious from sterile causes of severe systemic inflammation, assess the severity of systemic inflammation caused by bacterial infections, and decide whether to start or discontinue antibiotic therapy.7

Most cases of emphysematous cystitis can be treated with antibiotics, though early diagnosis is crucial to a favorable outcome. Delay in diagnosis may contribute to the 20% mortality rate associated with this condition.6

A 59-year-old woman with a history of chronic kidney disease and atonic bladder was brought to the hospital by emergency medical services. She had fallen in her home 2 days earlier and remained on the floor until neighbors eventually heard her cries and called 911. She complained of abdominal pain and distention along with emesis.

On presentation, she had tachycardia and tachypnea. The examination was notable for pronounced abdominal distention, diminished bowel sounds, and costovertebral angle tenderness.

While laboratory work was being done, the patient’s tachypnea progressed to respiratory distress, and she ultimately required intubation. Vasopressors were started, as the patient was hemodynamically unstable. A Foley catheter was placed, which yielded about 1,100 mL of purulent urine.

Laboratory workup showed:

- Procalcitonin 189 ng/mL (reference range < 2.0 ng/mL)

- White blood cell count 10.7 × 109/L (4.5–10.0)

- Myoglobin 20,000 ng/mL (< 71)

- Serum creatinine 4.8 mg/dL (0.06–1.10).

Urinalysis was positive for infection; blood and urine cultures later were positive for Escherichia coli.

The patient went into shock that was refractory to pressors, culminating in cardiac arrest despite resuscitative measures.

EMPHYSEMATOUS CYSTITIS, A FORM OF URINARY TRACT INFECTION

Emphysematous cystitis is a rare form of complicated urinary tract infection characterized by gas inside the bladder and in the bladder wall. While the exact mechanisms underlying gas formation are not clear, gas-producing pathogens are clearly implicated in severe infection. E coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae are the most common organisms associated with emphysematous cystitis; others include Proteus mirabilis, and Enterobacter and Streptococcus species.1,2

More than 50% of patients with emphysematous cystitis have diabetes mellitus. Other risk factors include bladder outlet obstruction, neurogenic bladder, and female sex.3 The severity of disease ranges from asymptomatic pneumaturia (up to 7% of cases)2 to fulminant emphysematous cystitis, as in our patient.

The clinical presentation of emphysematous cystitis is nonspecific and can range from minimally symptomatic urinary tract infection to acute abdomen and septic shock.4

Some patients present with pneumaturia (the passing of gas through the urethra with micturition). Pneumaturia arises from 3 discrete causes: urologic instrumentation, fistula between the bladder and large or small bowel, and gas-producing bacteria in the bladder (emphysematous cystitis).5 Pneumaturia should always raise the suspicion of emphysematous cystitis.

The diagnosis can be made with either radiographic or computed tomographic evidence of gas within the bladder and bladder wall, in the absence of both bladder fistula and history of iatrogenic pneumaturia. Emphysematous cystitis should prompt urine and blood cultures to direct antimicrobial therapy, as 50% of patients with emphysematous cystitis have concomitant bacteremia.6

Our patient had an elevated serum level of procalcitonin, a marker of bacterial infection. Procalcitonin is a more specific biomarker of bacterial infection than acute-phase reactants such as the erythrocyte sedimentation rate or the C-reactive protein level. Measuring procalcitonin may help physicians make the diagnosis earlier, differentiate infectious from sterile causes of severe systemic inflammation, assess the severity of systemic inflammation caused by bacterial infections, and decide whether to start or discontinue antibiotic therapy.7

Most cases of emphysematous cystitis can be treated with antibiotics, though early diagnosis is crucial to a favorable outcome. Delay in diagnosis may contribute to the 20% mortality rate associated with this condition.6

- Stein JP, Spitz A, Elmajian DA, et al. Bilateral emphysematous pyelonephritis: a case report and review of the literature. Urology 1996; 47(1):129–134. pmid:8560648

- Amano M, Shimizu T. Emphysematous cystitis: a review of the literature. Intern Med 2014; 53(2):79–82. pmid:24429444

- Wang JH. Emphysematous cystitis. Urol Sci 2010; 21(4):185–186. doi:10.1016/S1879-5226(10)60041-3

- Thomas AA, Lane BR, Thomas AZ, Remer EM, Campbell SC, Shoskes DA. Emphysematous cystitis: a review of 135 cases. BJU Int 2007; 100(1):17–20. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.06930.x

- Arthur LM, Johnson HW. Pneumaturia: a case report and review of the literature. J Urol 1948; 60(4):659–665. pmid:18885959

- Grupper M, Kravtsov A, Potasman I. Emphysematous cystitis: illustrative case report and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 2007; 86(1):47–53. doi:10.1097/MD.0b013e3180307c3a

- Lee H. Procalcitonin as a biomarker of infectious diseases. Korean J Intern Med 2013; 28(3):285–291. doi:10.3904/kjim.2013.28.3.285

- Stein JP, Spitz A, Elmajian DA, et al. Bilateral emphysematous pyelonephritis: a case report and review of the literature. Urology 1996; 47(1):129–134. pmid:8560648

- Amano M, Shimizu T. Emphysematous cystitis: a review of the literature. Intern Med 2014; 53(2):79–82. pmid:24429444

- Wang JH. Emphysematous cystitis. Urol Sci 2010; 21(4):185–186. doi:10.1016/S1879-5226(10)60041-3

- Thomas AA, Lane BR, Thomas AZ, Remer EM, Campbell SC, Shoskes DA. Emphysematous cystitis: a review of 135 cases. BJU Int 2007; 100(1):17–20. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.06930.x

- Arthur LM, Johnson HW. Pneumaturia: a case report and review of the literature. J Urol 1948; 60(4):659–665. pmid:18885959

- Grupper M, Kravtsov A, Potasman I. Emphysematous cystitis: illustrative case report and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 2007; 86(1):47–53. doi:10.1097/MD.0b013e3180307c3a

- Lee H. Procalcitonin as a biomarker of infectious diseases. Korean J Intern Med 2013; 28(3):285–291. doi:10.3904/kjim.2013.28.3.285

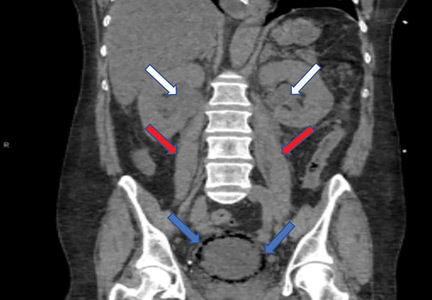

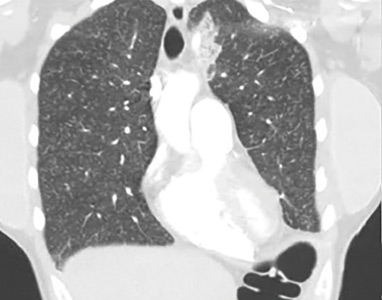

Lung complications of prescription drug abuse

A 39-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with a 2-day history of exertional dyspnea, left-sided chest pain with pleuritic characteristics, and cough without fever or chills. She had a history of severe postprandial nausea and vomiting, weight loss, and malnutrition, which had necessitated placement of a peripherally inserted central catheter in her right arm for total parenteral nutrition.

On physical examination, the patient was afebrile but tachycardic and tachypneic. Her oxygen saturation on room air by pulse oximetry was 91%, though she was not in significant distress. Breath sounds were equal bilaterally and clear, with symmetrical chest wall expansion.

Her white blood cell count was 18.5 × 109/L (reference range 3.5–10.5), with 19.3% eosinophils (reference range 1%–7%); her D-dimer level was also elevated.

Conditions to consider in a patient with these imaging findings in the setting of leukocytosis and eosinophilia include mycobacterial infection, hypersensitivity reaction, diffuse fungal infiltrates, and possibly metastatic disease such as thyroid carcinoma or melanoma. The patient reported having had a purified protein derivative test that was positive for tuberculosis, but she denied having had active disease.

She underwent bronchosocopy. Bronchoalveolar lavage specimen study showed an elevated eosinophil count of 17%. Acid-fast staining detected no organisms. Transbronchial biopsy study revealed foreign-body granulomas from microcrystalline cellulose microemboli deposited in the microvasculature of the patient’s lungs. Upon further questioning the patient admitted she had crushed oral tablets of prescribed opioids and injected them intravenously.

A COMPLICATION OF INJECTING ORAL TABLETS

Oral tablets typically contain talc, cellulose, cornstarch, or combinations of these substances as binding agents. When pulverized, the powder can be combined with water to form an injectable solution with higher and more rapid bioavailability.1,2 The binders, however, are insoluble and accumulate in various tissues.

Intravenous injection of microcellulose has been shown to produce pulmonary and peripheral eosinophilia in birds. In humans, the immune response in foreign body granulomatosis can vary, and case reports have not mentioned eosinophils in the lungs or serum.3,4

Deposition of these particles in pulmonary vessels is common and can trigger a potentially fatal reaction, presenting as acute onset of cough, chest pain, dyspnea, fever, and pulmonary hypertension. The severity of these clinical findings is relative to the degree of pulmonary hypertension created by the arteriolar involvement of these emboli.2,5

Our patient’s exertional dyspnea and hypoxemia resolved during 1 week of hospitalization with conservative management and supplemental oxygen. She was referred to our pain rehabilitation clinic, where she was successfully weaned from narcotics. Her pulmonary findings on computed tomography were still present 3 years after her initial images, though less prominent.

- Nguyen VT, Chan ES, Chou SH, et al. Pulmonary effects of IV injection of crushed oral tablets: “excipient lung disease.” AJR Am J Roentgenol 2014; 203(5):W506–W515. doi:10.2214/AJR.14.12582

- Bendeck SE, Leung AN, Berry GJ, Daniel D, Ruoss SJ. Cellulose granulomatosis presenting as centrilobular nodules: CT and histologic findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2001; 177(5):1151–1153. doi:10.2214/ajr.177.5.1771151

- Radow SK, Nachamkin I, Morrow C, et al. Foreign body granulomatosis. Clinical and immunologic findings. Am Rev Respir Dis 1983; 127(5):575–580. doi:10.1164/arrd.1983.127.5.575

- Wang W, Wideman RF Jr, Bersi TK, Erf GF. Pulmonary and hematological inflammatory responses to intravenous cellulose micro-particles in broilers. Poult Sci 2003; 82(5):771–780. doi:10.1093/ps/82.5.771

- Marchiori E, Lourenco S, Gasparetto TD, Zanetti G, Mano CM, Nobre LF. Pulmonary talcosis: imaging findings. Lung 2010; 188(2):165–171. doi:10.1007/s00408-010-9230-y

A 39-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with a 2-day history of exertional dyspnea, left-sided chest pain with pleuritic characteristics, and cough without fever or chills. She had a history of severe postprandial nausea and vomiting, weight loss, and malnutrition, which had necessitated placement of a peripherally inserted central catheter in her right arm for total parenteral nutrition.

On physical examination, the patient was afebrile but tachycardic and tachypneic. Her oxygen saturation on room air by pulse oximetry was 91%, though she was not in significant distress. Breath sounds were equal bilaterally and clear, with symmetrical chest wall expansion.

Her white blood cell count was 18.5 × 109/L (reference range 3.5–10.5), with 19.3% eosinophils (reference range 1%–7%); her D-dimer level was also elevated.

Conditions to consider in a patient with these imaging findings in the setting of leukocytosis and eosinophilia include mycobacterial infection, hypersensitivity reaction, diffuse fungal infiltrates, and possibly metastatic disease such as thyroid carcinoma or melanoma. The patient reported having had a purified protein derivative test that was positive for tuberculosis, but she denied having had active disease.

She underwent bronchosocopy. Bronchoalveolar lavage specimen study showed an elevated eosinophil count of 17%. Acid-fast staining detected no organisms. Transbronchial biopsy study revealed foreign-body granulomas from microcrystalline cellulose microemboli deposited in the microvasculature of the patient’s lungs. Upon further questioning the patient admitted she had crushed oral tablets of prescribed opioids and injected them intravenously.

A COMPLICATION OF INJECTING ORAL TABLETS

Oral tablets typically contain talc, cellulose, cornstarch, or combinations of these substances as binding agents. When pulverized, the powder can be combined with water to form an injectable solution with higher and more rapid bioavailability.1,2 The binders, however, are insoluble and accumulate in various tissues.

Intravenous injection of microcellulose has been shown to produce pulmonary and peripheral eosinophilia in birds. In humans, the immune response in foreign body granulomatosis can vary, and case reports have not mentioned eosinophils in the lungs or serum.3,4

Deposition of these particles in pulmonary vessels is common and can trigger a potentially fatal reaction, presenting as acute onset of cough, chest pain, dyspnea, fever, and pulmonary hypertension. The severity of these clinical findings is relative to the degree of pulmonary hypertension created by the arteriolar involvement of these emboli.2,5

Our patient’s exertional dyspnea and hypoxemia resolved during 1 week of hospitalization with conservative management and supplemental oxygen. She was referred to our pain rehabilitation clinic, where she was successfully weaned from narcotics. Her pulmonary findings on computed tomography were still present 3 years after her initial images, though less prominent.

A 39-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with a 2-day history of exertional dyspnea, left-sided chest pain with pleuritic characteristics, and cough without fever or chills. She had a history of severe postprandial nausea and vomiting, weight loss, and malnutrition, which had necessitated placement of a peripherally inserted central catheter in her right arm for total parenteral nutrition.

On physical examination, the patient was afebrile but tachycardic and tachypneic. Her oxygen saturation on room air by pulse oximetry was 91%, though she was not in significant distress. Breath sounds were equal bilaterally and clear, with symmetrical chest wall expansion.

Her white blood cell count was 18.5 × 109/L (reference range 3.5–10.5), with 19.3% eosinophils (reference range 1%–7%); her D-dimer level was also elevated.

Conditions to consider in a patient with these imaging findings in the setting of leukocytosis and eosinophilia include mycobacterial infection, hypersensitivity reaction, diffuse fungal infiltrates, and possibly metastatic disease such as thyroid carcinoma or melanoma. The patient reported having had a purified protein derivative test that was positive for tuberculosis, but she denied having had active disease.

She underwent bronchosocopy. Bronchoalveolar lavage specimen study showed an elevated eosinophil count of 17%. Acid-fast staining detected no organisms. Transbronchial biopsy study revealed foreign-body granulomas from microcrystalline cellulose microemboli deposited in the microvasculature of the patient’s lungs. Upon further questioning the patient admitted she had crushed oral tablets of prescribed opioids and injected them intravenously.

A COMPLICATION OF INJECTING ORAL TABLETS

Oral tablets typically contain talc, cellulose, cornstarch, or combinations of these substances as binding agents. When pulverized, the powder can be combined with water to form an injectable solution with higher and more rapid bioavailability.1,2 The binders, however, are insoluble and accumulate in various tissues.

Intravenous injection of microcellulose has been shown to produce pulmonary and peripheral eosinophilia in birds. In humans, the immune response in foreign body granulomatosis can vary, and case reports have not mentioned eosinophils in the lungs or serum.3,4

Deposition of these particles in pulmonary vessels is common and can trigger a potentially fatal reaction, presenting as acute onset of cough, chest pain, dyspnea, fever, and pulmonary hypertension. The severity of these clinical findings is relative to the degree of pulmonary hypertension created by the arteriolar involvement of these emboli.2,5

Our patient’s exertional dyspnea and hypoxemia resolved during 1 week of hospitalization with conservative management and supplemental oxygen. She was referred to our pain rehabilitation clinic, where she was successfully weaned from narcotics. Her pulmonary findings on computed tomography were still present 3 years after her initial images, though less prominent.

- Nguyen VT, Chan ES, Chou SH, et al. Pulmonary effects of IV injection of crushed oral tablets: “excipient lung disease.” AJR Am J Roentgenol 2014; 203(5):W506–W515. doi:10.2214/AJR.14.12582

- Bendeck SE, Leung AN, Berry GJ, Daniel D, Ruoss SJ. Cellulose granulomatosis presenting as centrilobular nodules: CT and histologic findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2001; 177(5):1151–1153. doi:10.2214/ajr.177.5.1771151

- Radow SK, Nachamkin I, Morrow C, et al. Foreign body granulomatosis. Clinical and immunologic findings. Am Rev Respir Dis 1983; 127(5):575–580. doi:10.1164/arrd.1983.127.5.575

- Wang W, Wideman RF Jr, Bersi TK, Erf GF. Pulmonary and hematological inflammatory responses to intravenous cellulose micro-particles in broilers. Poult Sci 2003; 82(5):771–780. doi:10.1093/ps/82.5.771

- Marchiori E, Lourenco S, Gasparetto TD, Zanetti G, Mano CM, Nobre LF. Pulmonary talcosis: imaging findings. Lung 2010; 188(2):165–171. doi:10.1007/s00408-010-9230-y

- Nguyen VT, Chan ES, Chou SH, et al. Pulmonary effects of IV injection of crushed oral tablets: “excipient lung disease.” AJR Am J Roentgenol 2014; 203(5):W506–W515. doi:10.2214/AJR.14.12582

- Bendeck SE, Leung AN, Berry GJ, Daniel D, Ruoss SJ. Cellulose granulomatosis presenting as centrilobular nodules: CT and histologic findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2001; 177(5):1151–1153. doi:10.2214/ajr.177.5.1771151

- Radow SK, Nachamkin I, Morrow C, et al. Foreign body granulomatosis. Clinical and immunologic findings. Am Rev Respir Dis 1983; 127(5):575–580. doi:10.1164/arrd.1983.127.5.575

- Wang W, Wideman RF Jr, Bersi TK, Erf GF. Pulmonary and hematological inflammatory responses to intravenous cellulose micro-particles in broilers. Poult Sci 2003; 82(5):771–780. doi:10.1093/ps/82.5.771

- Marchiori E, Lourenco S, Gasparetto TD, Zanetti G, Mano CM, Nobre LF. Pulmonary talcosis: imaging findings. Lung 2010; 188(2):165–171. doi:10.1007/s00408-010-9230-y

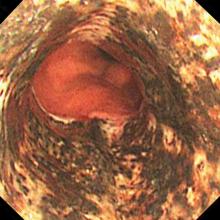

Acute necrotizing esophagitis

An 82-year-old man with poorly controlled diabetes mellitus presented to our emergency department with a 1-day history of confusion and coffee-ground emesis.

Biopsy study revealed necrosis of the esophageal mucosa. A diagnosis of acute necrotizing esophagitis was made.

ACUTE NECROTIZING ESOPHAGITIS

Acute necrotizing esophagitis is thought to arise from a combination of an ischemic insult to the esophagus, an impaired mucosal barrier system, and a backflow injury from chemical contents of gastric secretions.1 The tissue hypoperfusion derives from vasculopathy, hypotension, or malnutrition. It is associated with diabetes mellitus, diabetic ketoacidosis, lactic acidosis, alcohol abuse, cirrhosis, renal insufficiency, malignancy, antibiotic use, esophageal infections, and aortic dissection.

The esophagus has a diverse blood supply. The upper esophagus is supplied by the inferior thyroid arteries, the mid-esophagus by the bronchial, proper esophageal, and intercostal arteries, and the distal esophagus by the left gastric and left inferior phrenic arteries.1

KEY FEATURES AND DIAGNOSTIC CLUES

The necrotic changes are prominent in the distal esophagus, which is more susceptible to ischemia and mucosal injury. The characteristic endoscopic finding is a diffuse black esophagus with a sharp transition to normal mucosa at the gastroesophageal junction.

The differential diagnosis includes melanosis, pseudomelanosis, malignant melanoma, acanthosis nigricans, coal dust deposition, caustic ingestion, radiation esophagitis, and infectious esophagitis caused by cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex virus, Candida albicans, or Klebsiella pneumoniae.2–4

TREATMENT AND OUTCOME

Avoidance of oral intake and gastric acid suppression with intravenous proton pump inhibitors are recommended to prevent additional injury of the esophageal mucosa.

The condition generally resolves with restored blood flow and treatment of any coexisting illness. However, it may be complicated by perforation (6.8%), mediastinitis (5.7%), or subsequent development of esophageal stricture (10.2%).5 Patients with esophageal stricture require endoscopic dilation after mucosal recovery.

The overall risk of death in acute necrotizing esophagitis is high (31.8%) and most often due to the underlying disease, such as sepsis, malignancy, cardiogenic shock, or hypovolemic shock.5 The mortality rate directly attributed to complications of acute necrotizing esophagitis is much lower (5.7%).5

- Gurvits GE. Black esophagus: acute esophageal necrosis syndrome. World J Gastroenterol 2010; 16(26):3219–3225. pmid:20614476

- Khan HA. Coal dust deposition—rare cause of “black esophagus.” Am J Gastroenterol 1996; 91(10):2256. pmid:8855776

- Ertekin C, Alimoglu O, Akyildiz H, Guloglu R, Taviloglu K. The results of caustic ingestions. Hepatogastroenterology 2004; 51(59):1397–1400. pmid:15362762

- Kozlowski LM, Nigra TP. Esophageal acanthosis nigricans in association with adenocarcinoma from an unknown primary site. J Am Acad Dermatol 1992; 26(2 pt 2):348–351. pmid:1569256

- Gurvits GE, Shapsis A, Lau N, Gualtieri N, Robilotti JG. Acute esophageal necrosis: a rare syndrome. J Gastroenterol 2007; 42(1):29–38. doi:10.1007/s00535-006-1974-z

An 82-year-old man with poorly controlled diabetes mellitus presented to our emergency department with a 1-day history of confusion and coffee-ground emesis.

Biopsy study revealed necrosis of the esophageal mucosa. A diagnosis of acute necrotizing esophagitis was made.

ACUTE NECROTIZING ESOPHAGITIS

Acute necrotizing esophagitis is thought to arise from a combination of an ischemic insult to the esophagus, an impaired mucosal barrier system, and a backflow injury from chemical contents of gastric secretions.1 The tissue hypoperfusion derives from vasculopathy, hypotension, or malnutrition. It is associated with diabetes mellitus, diabetic ketoacidosis, lactic acidosis, alcohol abuse, cirrhosis, renal insufficiency, malignancy, antibiotic use, esophageal infections, and aortic dissection.

The esophagus has a diverse blood supply. The upper esophagus is supplied by the inferior thyroid arteries, the mid-esophagus by the bronchial, proper esophageal, and intercostal arteries, and the distal esophagus by the left gastric and left inferior phrenic arteries.1

KEY FEATURES AND DIAGNOSTIC CLUES

The necrotic changes are prominent in the distal esophagus, which is more susceptible to ischemia and mucosal injury. The characteristic endoscopic finding is a diffuse black esophagus with a sharp transition to normal mucosa at the gastroesophageal junction.

The differential diagnosis includes melanosis, pseudomelanosis, malignant melanoma, acanthosis nigricans, coal dust deposition, caustic ingestion, radiation esophagitis, and infectious esophagitis caused by cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex virus, Candida albicans, or Klebsiella pneumoniae.2–4

TREATMENT AND OUTCOME

Avoidance of oral intake and gastric acid suppression with intravenous proton pump inhibitors are recommended to prevent additional injury of the esophageal mucosa.

The condition generally resolves with restored blood flow and treatment of any coexisting illness. However, it may be complicated by perforation (6.8%), mediastinitis (5.7%), or subsequent development of esophageal stricture (10.2%).5 Patients with esophageal stricture require endoscopic dilation after mucosal recovery.

The overall risk of death in acute necrotizing esophagitis is high (31.8%) and most often due to the underlying disease, such as sepsis, malignancy, cardiogenic shock, or hypovolemic shock.5 The mortality rate directly attributed to complications of acute necrotizing esophagitis is much lower (5.7%).5

An 82-year-old man with poorly controlled diabetes mellitus presented to our emergency department with a 1-day history of confusion and coffee-ground emesis.

Biopsy study revealed necrosis of the esophageal mucosa. A diagnosis of acute necrotizing esophagitis was made.

ACUTE NECROTIZING ESOPHAGITIS

Acute necrotizing esophagitis is thought to arise from a combination of an ischemic insult to the esophagus, an impaired mucosal barrier system, and a backflow injury from chemical contents of gastric secretions.1 The tissue hypoperfusion derives from vasculopathy, hypotension, or malnutrition. It is associated with diabetes mellitus, diabetic ketoacidosis, lactic acidosis, alcohol abuse, cirrhosis, renal insufficiency, malignancy, antibiotic use, esophageal infections, and aortic dissection.

The esophagus has a diverse blood supply. The upper esophagus is supplied by the inferior thyroid arteries, the mid-esophagus by the bronchial, proper esophageal, and intercostal arteries, and the distal esophagus by the left gastric and left inferior phrenic arteries.1

KEY FEATURES AND DIAGNOSTIC CLUES

The necrotic changes are prominent in the distal esophagus, which is more susceptible to ischemia and mucosal injury. The characteristic endoscopic finding is a diffuse black esophagus with a sharp transition to normal mucosa at the gastroesophageal junction.

The differential diagnosis includes melanosis, pseudomelanosis, malignant melanoma, acanthosis nigricans, coal dust deposition, caustic ingestion, radiation esophagitis, and infectious esophagitis caused by cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex virus, Candida albicans, or Klebsiella pneumoniae.2–4

TREATMENT AND OUTCOME

Avoidance of oral intake and gastric acid suppression with intravenous proton pump inhibitors are recommended to prevent additional injury of the esophageal mucosa.

The condition generally resolves with restored blood flow and treatment of any coexisting illness. However, it may be complicated by perforation (6.8%), mediastinitis (5.7%), or subsequent development of esophageal stricture (10.2%).5 Patients with esophageal stricture require endoscopic dilation after mucosal recovery.

The overall risk of death in acute necrotizing esophagitis is high (31.8%) and most often due to the underlying disease, such as sepsis, malignancy, cardiogenic shock, or hypovolemic shock.5 The mortality rate directly attributed to complications of acute necrotizing esophagitis is much lower (5.7%).5

- Gurvits GE. Black esophagus: acute esophageal necrosis syndrome. World J Gastroenterol 2010; 16(26):3219–3225. pmid:20614476

- Khan HA. Coal dust deposition—rare cause of “black esophagus.” Am J Gastroenterol 1996; 91(10):2256. pmid:8855776

- Ertekin C, Alimoglu O, Akyildiz H, Guloglu R, Taviloglu K. The results of caustic ingestions. Hepatogastroenterology 2004; 51(59):1397–1400. pmid:15362762

- Kozlowski LM, Nigra TP. Esophageal acanthosis nigricans in association with adenocarcinoma from an unknown primary site. J Am Acad Dermatol 1992; 26(2 pt 2):348–351. pmid:1569256

- Gurvits GE, Shapsis A, Lau N, Gualtieri N, Robilotti JG. Acute esophageal necrosis: a rare syndrome. J Gastroenterol 2007; 42(1):29–38. doi:10.1007/s00535-006-1974-z

- Gurvits GE. Black esophagus: acute esophageal necrosis syndrome. World J Gastroenterol 2010; 16(26):3219–3225. pmid:20614476

- Khan HA. Coal dust deposition—rare cause of “black esophagus.” Am J Gastroenterol 1996; 91(10):2256. pmid:8855776

- Ertekin C, Alimoglu O, Akyildiz H, Guloglu R, Taviloglu K. The results of caustic ingestions. Hepatogastroenterology 2004; 51(59):1397–1400. pmid:15362762

- Kozlowski LM, Nigra TP. Esophageal acanthosis nigricans in association with adenocarcinoma from an unknown primary site. J Am Acad Dermatol 1992; 26(2 pt 2):348–351. pmid:1569256

- Gurvits GE, Shapsis A, Lau N, Gualtieri N, Robilotti JG. Acute esophageal necrosis: a rare syndrome. J Gastroenterol 2007; 42(1):29–38. doi:10.1007/s00535-006-1974-z

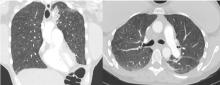

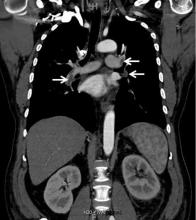

Renal vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism

A 49-year-old man developed nephrotic-range proteinuria (urine protein–creatinine ratio 4.1 g/g), and primary membranous nephropathy was diagnosed by kidney biopsy. He declined therapy apart from angiotensin receptor blockade.

Five months after undergoing the biopsy, he presented to the emergency room with marked dyspnea, cough, and epigastric discomfort. His blood pressure was 160/100 mm Hg, heart rate 95 beats/minute, and oxygen saturation by pulse oximetry 97% at rest on ambient air, decreasing to 92% with ambulation.

Initial laboratory testing results were as follows:

- Sodium 135 mmol/L (reference range 136–144)

- Potassium 3.9 mmol/L (3.7–5.1)

- Chloride 104 mmol/L (97–105)

- Bicarbonate 21 mmol/L (22–30)

- Blood urea nitrogen 14 mg/dL (9–24)

- Serum creatinine 1.1 mg/dL (0.73–1.22)

- Albumin 2.1 g/dL (3.4–4.9).

Urinalysis revealed the following:

- 5 red blood cells per high-power field, compared with 1 to 2 previously

- 3+ proteinuria

- Urine protein–creatinine ratio 11 g/g

- No glucosuria.

Electrocardiography revealed normal sinus rhythm without ischemic changes. Chest radiography did not show consolidation.

At 7 months after the thrombotic event, there was no evidence of residual renal vein thrombosis on magnetic resonance venography, and at 14 months his serum creatinine level was 0.9 mg/dL, albumin 4.0 g/dL, and urine protein–creatinine ratio 0.8 g/g.

RENAL VEIN THROMBOSIS: RISK FACTORS AND CLINICAL FEATURES

Severe hypoalbuminemia in the setting of nephrotic syndrome due to membranous nephropathy is associated with the highest risk of venous thromboembolic events, with renal vein thrombus being the classic complication.1 Venous thromboembolic events also occur in other nephrotic syndromes, albeit at a lower frequency.2

Venous thromboembolic events are estimated to occur in 7% to 33% of patients with membranous glomerulopathy, with albumin levels less than 2.8 g/dL considered a notable risk factor.1,2

While often a chronic complication, acute renal vein thrombosis may present with flank pain and hematuria.3 In our patient, the dramatic increase in proteinuria and possibly the increase in hematuria suggested renal vein thrombosis. Proximal tubular dysfunction, such as glucosuria, can be seen on occasion.

DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT

Screening asymptomatic patients for renal vein thrombosis is not recommended, and the decision to start prophylactic anticoagulation must be individualized.4

Although renal venography historically was the gold standard test to diagnose renal vein thrombosis, it has been replaced by noninvasive imaging such as computed tomography and magnetic resonance venography.

While anticoagulation remains the treatment of choice, catheter-directed thrombectomy or surgical thrombectomy can be considered for some patients with acute renal vein thrombosis.5

- Couser WG. Primary membranous nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2017; 12(6):983–997. doi:10.2215/CJN.11761116

- Barbour SJ, Greenwald A, Djurdjev O, et al. Disease-specific risk of venous thromboembolic events is increased in idiopathic glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int 2012; 81(2):190–195. doi:10.1038/ki.2011.312

- Lionaki S, Derebail VK, Hogan SL, et al. Venous thromboembolism in patients with membranous nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2012; 7(1):43–51. doi:10.2215/CJN.04250511

- Lee T, Biddle AK, Lionaki S, et al. Personalized prophylactic anticoagulation decision analysis in patients with membranous nephropathy. Kidney Int 2014; 85(6):1412–1420. doi:10.1038/ki.2013.476

- Jaar BG, Kim HS, Samaniego MD, Lund GB, Atta MG. Percutaneous mechanical thrombectomy: a new approach in the treatment of acute renal-vein thrombosis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2002; 17(6):1122–1125. pmid:12032209

A 49-year-old man developed nephrotic-range proteinuria (urine protein–creatinine ratio 4.1 g/g), and primary membranous nephropathy was diagnosed by kidney biopsy. He declined therapy apart from angiotensin receptor blockade.

Five months after undergoing the biopsy, he presented to the emergency room with marked dyspnea, cough, and epigastric discomfort. His blood pressure was 160/100 mm Hg, heart rate 95 beats/minute, and oxygen saturation by pulse oximetry 97% at rest on ambient air, decreasing to 92% with ambulation.

Initial laboratory testing results were as follows:

- Sodium 135 mmol/L (reference range 136–144)

- Potassium 3.9 mmol/L (3.7–5.1)

- Chloride 104 mmol/L (97–105)

- Bicarbonate 21 mmol/L (22–30)

- Blood urea nitrogen 14 mg/dL (9–24)

- Serum creatinine 1.1 mg/dL (0.73–1.22)

- Albumin 2.1 g/dL (3.4–4.9).

Urinalysis revealed the following:

- 5 red blood cells per high-power field, compared with 1 to 2 previously

- 3+ proteinuria

- Urine protein–creatinine ratio 11 g/g

- No glucosuria.

Electrocardiography revealed normal sinus rhythm without ischemic changes. Chest radiography did not show consolidation.

At 7 months after the thrombotic event, there was no evidence of residual renal vein thrombosis on magnetic resonance venography, and at 14 months his serum creatinine level was 0.9 mg/dL, albumin 4.0 g/dL, and urine protein–creatinine ratio 0.8 g/g.

RENAL VEIN THROMBOSIS: RISK FACTORS AND CLINICAL FEATURES

Severe hypoalbuminemia in the setting of nephrotic syndrome due to membranous nephropathy is associated with the highest risk of venous thromboembolic events, with renal vein thrombus being the classic complication.1 Venous thromboembolic events also occur in other nephrotic syndromes, albeit at a lower frequency.2

Venous thromboembolic events are estimated to occur in 7% to 33% of patients with membranous glomerulopathy, with albumin levels less than 2.8 g/dL considered a notable risk factor.1,2

While often a chronic complication, acute renal vein thrombosis may present with flank pain and hematuria.3 In our patient, the dramatic increase in proteinuria and possibly the increase in hematuria suggested renal vein thrombosis. Proximal tubular dysfunction, such as glucosuria, can be seen on occasion.

DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT

Screening asymptomatic patients for renal vein thrombosis is not recommended, and the decision to start prophylactic anticoagulation must be individualized.4

Although renal venography historically was the gold standard test to diagnose renal vein thrombosis, it has been replaced by noninvasive imaging such as computed tomography and magnetic resonance venography.

While anticoagulation remains the treatment of choice, catheter-directed thrombectomy or surgical thrombectomy can be considered for some patients with acute renal vein thrombosis.5

A 49-year-old man developed nephrotic-range proteinuria (urine protein–creatinine ratio 4.1 g/g), and primary membranous nephropathy was diagnosed by kidney biopsy. He declined therapy apart from angiotensin receptor blockade.

Five months after undergoing the biopsy, he presented to the emergency room with marked dyspnea, cough, and epigastric discomfort. His blood pressure was 160/100 mm Hg, heart rate 95 beats/minute, and oxygen saturation by pulse oximetry 97% at rest on ambient air, decreasing to 92% with ambulation.

Initial laboratory testing results were as follows:

- Sodium 135 mmol/L (reference range 136–144)

- Potassium 3.9 mmol/L (3.7–5.1)

- Chloride 104 mmol/L (97–105)

- Bicarbonate 21 mmol/L (22–30)

- Blood urea nitrogen 14 mg/dL (9–24)

- Serum creatinine 1.1 mg/dL (0.73–1.22)

- Albumin 2.1 g/dL (3.4–4.9).

Urinalysis revealed the following:

- 5 red blood cells per high-power field, compared with 1 to 2 previously

- 3+ proteinuria

- Urine protein–creatinine ratio 11 g/g

- No glucosuria.

Electrocardiography revealed normal sinus rhythm without ischemic changes. Chest radiography did not show consolidation.

At 7 months after the thrombotic event, there was no evidence of residual renal vein thrombosis on magnetic resonance venography, and at 14 months his serum creatinine level was 0.9 mg/dL, albumin 4.0 g/dL, and urine protein–creatinine ratio 0.8 g/g.

RENAL VEIN THROMBOSIS: RISK FACTORS AND CLINICAL FEATURES

Severe hypoalbuminemia in the setting of nephrotic syndrome due to membranous nephropathy is associated with the highest risk of venous thromboembolic events, with renal vein thrombus being the classic complication.1 Venous thromboembolic events also occur in other nephrotic syndromes, albeit at a lower frequency.2

Venous thromboembolic events are estimated to occur in 7% to 33% of patients with membranous glomerulopathy, with albumin levels less than 2.8 g/dL considered a notable risk factor.1,2

While often a chronic complication, acute renal vein thrombosis may present with flank pain and hematuria.3 In our patient, the dramatic increase in proteinuria and possibly the increase in hematuria suggested renal vein thrombosis. Proximal tubular dysfunction, such as glucosuria, can be seen on occasion.

DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT

Screening asymptomatic patients for renal vein thrombosis is not recommended, and the decision to start prophylactic anticoagulation must be individualized.4

Although renal venography historically was the gold standard test to diagnose renal vein thrombosis, it has been replaced by noninvasive imaging such as computed tomography and magnetic resonance venography.

While anticoagulation remains the treatment of choice, catheter-directed thrombectomy or surgical thrombectomy can be considered for some patients with acute renal vein thrombosis.5

- Couser WG. Primary membranous nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2017; 12(6):983–997. doi:10.2215/CJN.11761116

- Barbour SJ, Greenwald A, Djurdjev O, et al. Disease-specific risk of venous thromboembolic events is increased in idiopathic glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int 2012; 81(2):190–195. doi:10.1038/ki.2011.312

- Lionaki S, Derebail VK, Hogan SL, et al. Venous thromboembolism in patients with membranous nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2012; 7(1):43–51. doi:10.2215/CJN.04250511

- Lee T, Biddle AK, Lionaki S, et al. Personalized prophylactic anticoagulation decision analysis in patients with membranous nephropathy. Kidney Int 2014; 85(6):1412–1420. doi:10.1038/ki.2013.476

- Jaar BG, Kim HS, Samaniego MD, Lund GB, Atta MG. Percutaneous mechanical thrombectomy: a new approach in the treatment of acute renal-vein thrombosis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2002; 17(6):1122–1125. pmid:12032209

- Couser WG. Primary membranous nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2017; 12(6):983–997. doi:10.2215/CJN.11761116

- Barbour SJ, Greenwald A, Djurdjev O, et al. Disease-specific risk of venous thromboembolic events is increased in idiopathic glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int 2012; 81(2):190–195. doi:10.1038/ki.2011.312

- Lionaki S, Derebail VK, Hogan SL, et al. Venous thromboembolism in patients with membranous nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2012; 7(1):43–51. doi:10.2215/CJN.04250511

- Lee T, Biddle AK, Lionaki S, et al. Personalized prophylactic anticoagulation decision analysis in patients with membranous nephropathy. Kidney Int 2014; 85(6):1412–1420. doi:10.1038/ki.2013.476

- Jaar BG, Kim HS, Samaniego MD, Lund GB, Atta MG. Percutaneous mechanical thrombectomy: a new approach in the treatment of acute renal-vein thrombosis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2002; 17(6):1122–1125. pmid:12032209

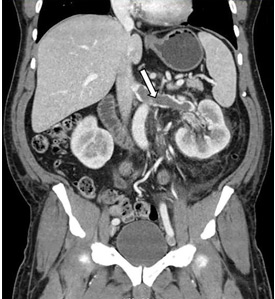

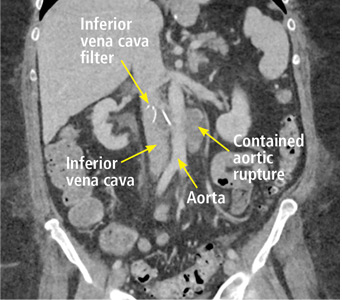

Back pain as a sign of inferior vena cava filter complications

A 63-year-old woman presented with an acute exacerbation of chronic back pain after a fall. She was taking warfarin because of a history of factor V Leiden, deep vein thrombosis, and pulmonary embolism, for which a temporary inferior vena cava (IVC) filter had been placed 8 years ago. Her physicians had subsequently tried to remove the filter, without success. Some time after that, 1 of the filter struts had been removed after it migrated through her abdominal wall.

Laboratory testing revealed a supratherapeutic international normalized ratio of 8.5.

The patient underwent endovascular aneurysm repair with adequate placement of a vascular graft. She was discharged on therapeutic anticoagulation, and her back pain had notably improved.

COMPLICATIONS OF IVC FILTERS

In the United States, the use of IVC filters has increased significantly over the last decade, with placement rates ranging from 12% to 17% in patients with venous thromboembolism.1

The American Heart Association recommends filter placement for patients with venous thromboembolism for whom anticoagulation has failed or is contraindicated, patients unable to withstand pulmonary embolism, and patients who are hemodynamically unstable.2 While indications vary in the guidelines released by different societies, filters are most often placed in patients who have an acute bleed, significant surgery after admission for venous thromboembolism, metastatic cancer, and severe illness.3

Complications can occur during and after insertion and during removal. They are more frequent with temporary than with permanent filters, and include filter movement and fracture as well as occlusion and penetration.4,5

In our patient, we believe that the 3 remaining filter struts likely penetrated the wall of the IVC to the extent that they encountered adjacent structures (aorta, duodenum, kidney).

Of cases of IVC filter penetration reported to a US Food and Drug Administration database, 13.1% involved small bowel perforation, 6.5% involved aortic perforation, and 4.2% involved retroperitoneal bleeding. Symptoms such as abdominal and back pain were present in 38.3% of cases involving IVC penetration.5

Therefore, the differential diagnosis for patients with a history of IVC filter placement presenting with these symptoms should address filter complications, including occlusion, incorrect placement, fracture, migration, and penetration of the filter.4 If complications occur, treatment options include anticoagulation, endovascular repair, and surgical intervention.

- Alkhouli M, Bashir R. Inferior vena cava filters in the United States: less is more. Int J Cardiol 2014; 177(3):742–743. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.08.010

- Jaff MR, McMurtry MS, Archer SL, et al; American Heart Association Council on Cardiopulmonary, Critical Care, Perioperative and Resuscitation; American Heart Association Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease; American Heart Association Council on Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology. Management of massive and submassive pulmonary embolism, iliofemoral deep vein thrombosis, and chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2011; 123(16):1788–1830. doi:10.1161/CIR.0b013e318214914f

- White RH, Geraghty EM, Brunson A, et al. High variation between hospitals in vena cava filter use for venous thromboembolism. JAMA Intern Med 2013; 173(7):506–512. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.2352

- Sella DM, Oldenburg WA. Complications of inferior vena cava filters. Semin Vasc Surg 2013; 26(1):23–28. doi:10.1053/j.semvascsurg.2013.04.005

- Andreoli JM, Lewandowski RJ, Vogelzang RL, Ryu RK. Comparison of complication rates associated with permanent and retrievable inferior vena cava filters: a review of the MAUDE database. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2014; 25(8):1181–1185. doi:10.1016/j.jvir.2014.04.016

A 63-year-old woman presented with an acute exacerbation of chronic back pain after a fall. She was taking warfarin because of a history of factor V Leiden, deep vein thrombosis, and pulmonary embolism, for which a temporary inferior vena cava (IVC) filter had been placed 8 years ago. Her physicians had subsequently tried to remove the filter, without success. Some time after that, 1 of the filter struts had been removed after it migrated through her abdominal wall.

Laboratory testing revealed a supratherapeutic international normalized ratio of 8.5.

The patient underwent endovascular aneurysm repair with adequate placement of a vascular graft. She was discharged on therapeutic anticoagulation, and her back pain had notably improved.

COMPLICATIONS OF IVC FILTERS

In the United States, the use of IVC filters has increased significantly over the last decade, with placement rates ranging from 12% to 17% in patients with venous thromboembolism.1

The American Heart Association recommends filter placement for patients with venous thromboembolism for whom anticoagulation has failed or is contraindicated, patients unable to withstand pulmonary embolism, and patients who are hemodynamically unstable.2 While indications vary in the guidelines released by different societies, filters are most often placed in patients who have an acute bleed, significant surgery after admission for venous thromboembolism, metastatic cancer, and severe illness.3

Complications can occur during and after insertion and during removal. They are more frequent with temporary than with permanent filters, and include filter movement and fracture as well as occlusion and penetration.4,5

In our patient, we believe that the 3 remaining filter struts likely penetrated the wall of the IVC to the extent that they encountered adjacent structures (aorta, duodenum, kidney).

Of cases of IVC filter penetration reported to a US Food and Drug Administration database, 13.1% involved small bowel perforation, 6.5% involved aortic perforation, and 4.2% involved retroperitoneal bleeding. Symptoms such as abdominal and back pain were present in 38.3% of cases involving IVC penetration.5

Therefore, the differential diagnosis for patients with a history of IVC filter placement presenting with these symptoms should address filter complications, including occlusion, incorrect placement, fracture, migration, and penetration of the filter.4 If complications occur, treatment options include anticoagulation, endovascular repair, and surgical intervention.

A 63-year-old woman presented with an acute exacerbation of chronic back pain after a fall. She was taking warfarin because of a history of factor V Leiden, deep vein thrombosis, and pulmonary embolism, for which a temporary inferior vena cava (IVC) filter had been placed 8 years ago. Her physicians had subsequently tried to remove the filter, without success. Some time after that, 1 of the filter struts had been removed after it migrated through her abdominal wall.

Laboratory testing revealed a supratherapeutic international normalized ratio of 8.5.

The patient underwent endovascular aneurysm repair with adequate placement of a vascular graft. She was discharged on therapeutic anticoagulation, and her back pain had notably improved.

COMPLICATIONS OF IVC FILTERS

In the United States, the use of IVC filters has increased significantly over the last decade, with placement rates ranging from 12% to 17% in patients with venous thromboembolism.1

The American Heart Association recommends filter placement for patients with venous thromboembolism for whom anticoagulation has failed or is contraindicated, patients unable to withstand pulmonary embolism, and patients who are hemodynamically unstable.2 While indications vary in the guidelines released by different societies, filters are most often placed in patients who have an acute bleed, significant surgery after admission for venous thromboembolism, metastatic cancer, and severe illness.3

Complications can occur during and after insertion and during removal. They are more frequent with temporary than with permanent filters, and include filter movement and fracture as well as occlusion and penetration.4,5

In our patient, we believe that the 3 remaining filter struts likely penetrated the wall of the IVC to the extent that they encountered adjacent structures (aorta, duodenum, kidney).

Of cases of IVC filter penetration reported to a US Food and Drug Administration database, 13.1% involved small bowel perforation, 6.5% involved aortic perforation, and 4.2% involved retroperitoneal bleeding. Symptoms such as abdominal and back pain were present in 38.3% of cases involving IVC penetration.5

Therefore, the differential diagnosis for patients with a history of IVC filter placement presenting with these symptoms should address filter complications, including occlusion, incorrect placement, fracture, migration, and penetration of the filter.4 If complications occur, treatment options include anticoagulation, endovascular repair, and surgical intervention.

- Alkhouli M, Bashir R. Inferior vena cava filters in the United States: less is more. Int J Cardiol 2014; 177(3):742–743. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.08.010

- Jaff MR, McMurtry MS, Archer SL, et al; American Heart Association Council on Cardiopulmonary, Critical Care, Perioperative and Resuscitation; American Heart Association Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease; American Heart Association Council on Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology. Management of massive and submassive pulmonary embolism, iliofemoral deep vein thrombosis, and chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2011; 123(16):1788–1830. doi:10.1161/CIR.0b013e318214914f

- White RH, Geraghty EM, Brunson A, et al. High variation between hospitals in vena cava filter use for venous thromboembolism. JAMA Intern Med 2013; 173(7):506–512. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.2352

- Sella DM, Oldenburg WA. Complications of inferior vena cava filters. Semin Vasc Surg 2013; 26(1):23–28. doi:10.1053/j.semvascsurg.2013.04.005

- Andreoli JM, Lewandowski RJ, Vogelzang RL, Ryu RK. Comparison of complication rates associated with permanent and retrievable inferior vena cava filters: a review of the MAUDE database. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2014; 25(8):1181–1185. doi:10.1016/j.jvir.2014.04.016

- Alkhouli M, Bashir R. Inferior vena cava filters in the United States: less is more. Int J Cardiol 2014; 177(3):742–743. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.08.010

- Jaff MR, McMurtry MS, Archer SL, et al; American Heart Association Council on Cardiopulmonary, Critical Care, Perioperative and Resuscitation; American Heart Association Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease; American Heart Association Council on Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology. Management of massive and submassive pulmonary embolism, iliofemoral deep vein thrombosis, and chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2011; 123(16):1788–1830. doi:10.1161/CIR.0b013e318214914f

- White RH, Geraghty EM, Brunson A, et al. High variation between hospitals in vena cava filter use for venous thromboembolism. JAMA Intern Med 2013; 173(7):506–512. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.2352

- Sella DM, Oldenburg WA. Complications of inferior vena cava filters. Semin Vasc Surg 2013; 26(1):23–28. doi:10.1053/j.semvascsurg.2013.04.005

- Andreoli JM, Lewandowski RJ, Vogelzang RL, Ryu RK. Comparison of complication rates associated with permanent and retrievable inferior vena cava filters: a review of the MAUDE database. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2014; 25(8):1181–1185. doi:10.1016/j.jvir.2014.04.016

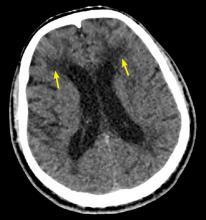

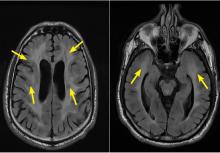

When stroke runs in the family

A 54-year-old man presented to our hospital with acute-onset left-sided weakness and right facial droop. Three days earlier he had also had migraine-like headaches, which he had never experienced before. He also reported a change in behavior during the past week, which his family had described as inappropriate laughter.

He had no history of hypertension, diabetes, or dyslipidemia. He did not smoke or drink alcohol. However, he had an extensive family history of stroke. His mother had a stroke at age 50, his brother a stroke at age 57, and his sister had been admitted for a stroke 1 month earlier at the age of 52.

On examination, he had weakness of the left arm and leg, right facial droop, and hyperactive reflexes on the left side. He had no sensory or cerebellar deficits. He had episodes of laughter during the examination.

We learned that the patient’s sister had undergone a workup showing mutations in the NOTCH3 gene and a skin biopsy study consistent with CADASIL.

Our patient was started on antiplatelet and high-intensity statin therapy. His symptoms improved, and he was discharged to an acute inpatient rehabilitation facility. He was referred to a CADASIL registry.

STROKE AND HEREDITY

CADASIL is a rare hereditary vascular disorder inherited in an autosomal dominant manner. It is the most common inherited form of small-vessel disease and results from a mutation in the NOTCH3 gene that leads to degeneration of smooth muscle in cerebral blood vessels. It can manifest as migraine with aura, vascular dementia, cognitive impairment, or ischemic stroke.

The diagnosis is based on a clinical picture that typically includes stroke at a young age (age 40 to 50) in the absence of stroke risk factors, or frequent lacunar infarction episodes that can manifest as migraine, lacunar infarct, or dementia.1 Some patients, such as ours, may have subtle nonspecific behavioral changes such as inappropriate laughter, which may herald the development of an infarct.

Characteristic findings on MRI are white matter hyperintensities that tend to be bilateral and symmetrical in the periventricular areas. Symmetrical involvement in the temporal lobes has high sensitivity and specificity for CADASIL.2 Biopsy study of the skin, muscle, or sural nerve shows small-vessel changes that include thickening of the media, granular material positive on periodic acid-Schiff staining, and narrowing of the lumen. However, the gold standard for diagnosis is confirmation of the NOTCH3 mutation on chromosome 19.1,2

There is no known treatment for CADASIL.

- Davous P. CADASIL: a review with proposed diagnostic criteria. Eur J Neurol 1998; 5(3):219–233. pmid:10210836

- Stojanov D, Vojinovic S, Aracki-Trenkic A, et al. Imaging characteristics of cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leucoencephalopathy (CADASIL). Bosn J Basic Med Sci 2015; 15(1):1–8. doi:10.17305/bjbms.2015.247

A 54-year-old man presented to our hospital with acute-onset left-sided weakness and right facial droop. Three days earlier he had also had migraine-like headaches, which he had never experienced before. He also reported a change in behavior during the past week, which his family had described as inappropriate laughter.

He had no history of hypertension, diabetes, or dyslipidemia. He did not smoke or drink alcohol. However, he had an extensive family history of stroke. His mother had a stroke at age 50, his brother a stroke at age 57, and his sister had been admitted for a stroke 1 month earlier at the age of 52.

On examination, he had weakness of the left arm and leg, right facial droop, and hyperactive reflexes on the left side. He had no sensory or cerebellar deficits. He had episodes of laughter during the examination.

We learned that the patient’s sister had undergone a workup showing mutations in the NOTCH3 gene and a skin biopsy study consistent with CADASIL.

Our patient was started on antiplatelet and high-intensity statin therapy. His symptoms improved, and he was discharged to an acute inpatient rehabilitation facility. He was referred to a CADASIL registry.

STROKE AND HEREDITY

CADASIL is a rare hereditary vascular disorder inherited in an autosomal dominant manner. It is the most common inherited form of small-vessel disease and results from a mutation in the NOTCH3 gene that leads to degeneration of smooth muscle in cerebral blood vessels. It can manifest as migraine with aura, vascular dementia, cognitive impairment, or ischemic stroke.

The diagnosis is based on a clinical picture that typically includes stroke at a young age (age 40 to 50) in the absence of stroke risk factors, or frequent lacunar infarction episodes that can manifest as migraine, lacunar infarct, or dementia.1 Some patients, such as ours, may have subtle nonspecific behavioral changes such as inappropriate laughter, which may herald the development of an infarct.

Characteristic findings on MRI are white matter hyperintensities that tend to be bilateral and symmetrical in the periventricular areas. Symmetrical involvement in the temporal lobes has high sensitivity and specificity for CADASIL.2 Biopsy study of the skin, muscle, or sural nerve shows small-vessel changes that include thickening of the media, granular material positive on periodic acid-Schiff staining, and narrowing of the lumen. However, the gold standard for diagnosis is confirmation of the NOTCH3 mutation on chromosome 19.1,2

There is no known treatment for CADASIL.

A 54-year-old man presented to our hospital with acute-onset left-sided weakness and right facial droop. Three days earlier he had also had migraine-like headaches, which he had never experienced before. He also reported a change in behavior during the past week, which his family had described as inappropriate laughter.

He had no history of hypertension, diabetes, or dyslipidemia. He did not smoke or drink alcohol. However, he had an extensive family history of stroke. His mother had a stroke at age 50, his brother a stroke at age 57, and his sister had been admitted for a stroke 1 month earlier at the age of 52.

On examination, he had weakness of the left arm and leg, right facial droop, and hyperactive reflexes on the left side. He had no sensory or cerebellar deficits. He had episodes of laughter during the examination.

We learned that the patient’s sister had undergone a workup showing mutations in the NOTCH3 gene and a skin biopsy study consistent with CADASIL.

Our patient was started on antiplatelet and high-intensity statin therapy. His symptoms improved, and he was discharged to an acute inpatient rehabilitation facility. He was referred to a CADASIL registry.

STROKE AND HEREDITY

CADASIL is a rare hereditary vascular disorder inherited in an autosomal dominant manner. It is the most common inherited form of small-vessel disease and results from a mutation in the NOTCH3 gene that leads to degeneration of smooth muscle in cerebral blood vessels. It can manifest as migraine with aura, vascular dementia, cognitive impairment, or ischemic stroke.

The diagnosis is based on a clinical picture that typically includes stroke at a young age (age 40 to 50) in the absence of stroke risk factors, or frequent lacunar infarction episodes that can manifest as migraine, lacunar infarct, or dementia.1 Some patients, such as ours, may have subtle nonspecific behavioral changes such as inappropriate laughter, which may herald the development of an infarct.

Characteristic findings on MRI are white matter hyperintensities that tend to be bilateral and symmetrical in the periventricular areas. Symmetrical involvement in the temporal lobes has high sensitivity and specificity for CADASIL.2 Biopsy study of the skin, muscle, or sural nerve shows small-vessel changes that include thickening of the media, granular material positive on periodic acid-Schiff staining, and narrowing of the lumen. However, the gold standard for diagnosis is confirmation of the NOTCH3 mutation on chromosome 19.1,2

There is no known treatment for CADASIL.

- Davous P. CADASIL: a review with proposed diagnostic criteria. Eur J Neurol 1998; 5(3):219–233. pmid:10210836

- Stojanov D, Vojinovic S, Aracki-Trenkic A, et al. Imaging characteristics of cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leucoencephalopathy (CADASIL). Bosn J Basic Med Sci 2015; 15(1):1–8. doi:10.17305/bjbms.2015.247

- Davous P. CADASIL: a review with proposed diagnostic criteria. Eur J Neurol 1998; 5(3):219–233. pmid:10210836

- Stojanov D, Vojinovic S, Aracki-Trenkic A, et al. Imaging characteristics of cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leucoencephalopathy (CADASIL). Bosn J Basic Med Sci 2015; 15(1):1–8. doi:10.17305/bjbms.2015.247