User login

Improving transitions for elderly patients

Transitions are always a time of concern for hospitalists, and the transition from hospital to skilled nursing facilities (SNF) is no exception.

“During the transition and in the 30 days after discharge from the hospital to a SNF, patients are at high risk for death, rehospitalization, and high-cost health care,” said Amber Moore, MD, MPH, a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, and instructor of medicine, Harvard Medical School. “Elderly adults are especially vulnerable because of impairments that may prevent them from participating in the discharge process and an increase in the risk that information is lost or incomplete during the care transition.”

To address this, she and several other physicians studied a novel video-conference program called Extension for Community Health Outcomes–Care Transitions (ECHO-CT) that connects an interdisciplinary hospital-based team with clinicians at SNFs to help reduce patient mortality, hospital readmission, skilled nursing facility length of stay, and 30-day health care costs.

The results of their study suggest that this intervention significantly decreased SNF length of stay, readmission rate, and costs of care, she says; the model they used is reproducible and has the potential to significantly improve care of these patients. “Our model was hospitalist run and is a mechanism to help hospitalists improve care to their patients during the transition time and beyond,” Dr. Moore said. “Furthermore, in participating in this model, hospitalists have the opportunity to better understand the challenges that face their patients after discharge and learn from postacute care providers.”

Ideally, she would like to see the model spread to other hospitals; she says hospitalists are well positioned to set up this program at their institution. “I also hope that our study highlights the incredible opportunity for improvement in the care of patients during transition from hospital to SNF and encourages hospitalists to look for innovative ways to improve care at this transition,” she said.

Reference

Moore AB, Krupp JE, Dufour AB, et al. Improving transitions to post-acute care for elderly patients using a novel video-conferencing program: ECHO-Care transitions. Am J Med. 2017 Oct;130(10):1199-204. Accessed June 6, 2017.

Transitions are always a time of concern for hospitalists, and the transition from hospital to skilled nursing facilities (SNF) is no exception.

“During the transition and in the 30 days after discharge from the hospital to a SNF, patients are at high risk for death, rehospitalization, and high-cost health care,” said Amber Moore, MD, MPH, a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, and instructor of medicine, Harvard Medical School. “Elderly adults are especially vulnerable because of impairments that may prevent them from participating in the discharge process and an increase in the risk that information is lost or incomplete during the care transition.”

To address this, she and several other physicians studied a novel video-conference program called Extension for Community Health Outcomes–Care Transitions (ECHO-CT) that connects an interdisciplinary hospital-based team with clinicians at SNFs to help reduce patient mortality, hospital readmission, skilled nursing facility length of stay, and 30-day health care costs.

The results of their study suggest that this intervention significantly decreased SNF length of stay, readmission rate, and costs of care, she says; the model they used is reproducible and has the potential to significantly improve care of these patients. “Our model was hospitalist run and is a mechanism to help hospitalists improve care to their patients during the transition time and beyond,” Dr. Moore said. “Furthermore, in participating in this model, hospitalists have the opportunity to better understand the challenges that face their patients after discharge and learn from postacute care providers.”

Ideally, she would like to see the model spread to other hospitals; she says hospitalists are well positioned to set up this program at their institution. “I also hope that our study highlights the incredible opportunity for improvement in the care of patients during transition from hospital to SNF and encourages hospitalists to look for innovative ways to improve care at this transition,” she said.

Reference

Moore AB, Krupp JE, Dufour AB, et al. Improving transitions to post-acute care for elderly patients using a novel video-conferencing program: ECHO-Care transitions. Am J Med. 2017 Oct;130(10):1199-204. Accessed June 6, 2017.

Transitions are always a time of concern for hospitalists, and the transition from hospital to skilled nursing facilities (SNF) is no exception.

“During the transition and in the 30 days after discharge from the hospital to a SNF, patients are at high risk for death, rehospitalization, and high-cost health care,” said Amber Moore, MD, MPH, a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, and instructor of medicine, Harvard Medical School. “Elderly adults are especially vulnerable because of impairments that may prevent them from participating in the discharge process and an increase in the risk that information is lost or incomplete during the care transition.”

To address this, she and several other physicians studied a novel video-conference program called Extension for Community Health Outcomes–Care Transitions (ECHO-CT) that connects an interdisciplinary hospital-based team with clinicians at SNFs to help reduce patient mortality, hospital readmission, skilled nursing facility length of stay, and 30-day health care costs.

The results of their study suggest that this intervention significantly decreased SNF length of stay, readmission rate, and costs of care, she says; the model they used is reproducible and has the potential to significantly improve care of these patients. “Our model was hospitalist run and is a mechanism to help hospitalists improve care to their patients during the transition time and beyond,” Dr. Moore said. “Furthermore, in participating in this model, hospitalists have the opportunity to better understand the challenges that face their patients after discharge and learn from postacute care providers.”

Ideally, she would like to see the model spread to other hospitals; she says hospitalists are well positioned to set up this program at their institution. “I also hope that our study highlights the incredible opportunity for improvement in the care of patients during transition from hospital to SNF and encourages hospitalists to look for innovative ways to improve care at this transition,” she said.

Reference

Moore AB, Krupp JE, Dufour AB, et al. Improving transitions to post-acute care for elderly patients using a novel video-conferencing program: ECHO-Care transitions. Am J Med. 2017 Oct;130(10):1199-204. Accessed June 6, 2017.

Scheduling patterns in hospital medicine

For years, the Society of Hospital Medicine has been asking hospital medicine programs about operational metrics in order to understand and catalog how they are functioning and evolving. After compensation, the scheduling patterns that hospital medicine groups (HMGs) are using is the most reviewed item in the report.

When hospital medicine first started, 7 days working followed by 7 days off (7-on-7-off) quickly became vogue. No one really knows how this happened, but it was most likely due to the fact that hospital medicine most closely resembled emergency medicine and scheduling similar to emergency medicine seemed to make sense (that is, 14 shifts per month). That along with the assumption that continuity of care was critical in inpatient care and would improve quality most likely resulted in the popularity of the 7-on-7-off schedule.

In the most recent survey in 2016, HMGs were once again asked to comment on how they schedule. Groups were able to choose from five scheduling options:

1. Seven days on followed by 7 days off

2. Other fixed rotation block schedules (such as 5-on 5-off; or 10-on 5-off)

3. Monday to Friday with rotating weekend coverage

4. Variable schedule

5. Other

Looking at HMG programs that serve only adult populations, a majority of them (48%) follow a fixed rotating schedule either 7 days on followed by 7 days off, or some other fixed schedule, while 31% of programs that responded stated that they used a Monday to Friday schedule. Looking at the programs as a whole, it would seem that the 7-on-7-off schedule was quickly losing popularity while the Monday to Friday schedule was increasingly being used. However, this broad generalization doesn’t really give you the full picture.

Upon analyzing the data further, we see some distinct differences arise based on program size. Small programs (fewer than 10 full-time employees [FTEs]) are much more likely to schedule a Monday to Friday schedule than any other model, whereas only a handful of large programs (greater than 20 FTEs) schedule in this way, rather choosing to use a 7-on-7-off schedule.

The last survey was done in 2014 and a lot has changed since then. Significantly more programs responded in 2016, compared with 2014 (530 vs. 355) and the majority of this increase was made of up smaller programs (fewer than 10 FTEs). Programs with four or fewer FTEs, compared with the prior survey, increased by over 400% (37 programs in 2014 vs. 151 programs in 2016). Overall, programs with fewer than 10 FTEs constituted over 50% of the total programs that responded in 2016 (whereas they made up only a third in 2014). This was particularly significant since size of the program was the one variable that determined how a program might schedule – other factors like geographic region, academic status, or primary hospital GME status did not show significant variance in how groups scheduled.

The second major change that occurred is that these same small programs (those with fewer than 10 FTEs) moved overwhelmingly to a Monday to Friday schedule. In 2014, only 3% of small programs scheduled using a Monday to Friday pattern, but in 2016 almost 50% of small programs reported scheduling in this way. This change in the overall composition of programs, with small programs now making up over 50% of the programs that reported, and the specific change in how small programs schedule results in a noteworthy decrease of programs using a 7 days on followed by 7 days off (7-on-7-off) schedule (53.8% in 2014 and only 38.1% in 2016), and a corresponding increase in the number of programs that schedule using a Monday to Friday schedule (4% in 2014 to 31% in 2016).

In distinct contrast to programs with fewer than 10 FTEs, a very similar number of programs with greater than 20 FTEs reported in 2016 as in 2014 – there was no increase in this subgroup. I’m not clear at this time if this is because there is truly no increase in the number of large programs nationally, or if there is another factor causing larger programs to under-report. The large programs that did report data in 2016 continue to utilize a 7-on-7-off schedule or another fixed rotating block schedule more than 50% of the time. In fact, the utilization of one of these two scheduling patterns increased slightly from 2014 to 2016 (from 52% to 58%). Those that did not use one of the prior mentioned scheduling patterns were most likely to schedule with a variable schedule. A Monday to Friday schedule was almost never used in programs of this size and showed no significant change from 2014 to 2016.

This snapshot highlights the changing landscape in hospital medicine. Hospital medicine is penetrating more and more into smaller and smaller hospitals, and has even made it into critical access hospitals. As recently as 5-10 years ago, it was felt that these hospitals were too small to have a hospital medicine program. This is likely one of the reasons for the increase in programs with four or fewer FTEs. There has also been increasing discontent with the 7-on-7-off schedule, which many feel is leading to burnout. Dr. Bob Wachter famously said during the closing plenary of the 2016 Society of Hospital Medicine Annual Meeting that the 7-on-7-off schedule was “a mistake.” Despite this brewing discontent, larger programs have not changed their scheduling patterns, likely because finding a another scheduling pattern that is effective, supports high-quality care, and is sustainable for such a large group is challenging.

Many people will say that there are as many different types of hospital medicine programs as there are hospital medicine programs. This is true for scheduling as for other aspects of hospital medicine operations. As we continue to grow and evolve as an industry, scheduling patterns will continue to change and evolve as well. For now, two patterns are emerging – smaller programs are utilizing a Monday to Friday schedule and larger programs are utilizing a 7-on-7-off schedule. Only time will tell if these scheduling patterns persist or continue to evolve.

Dr. George is a board certified internal medicine physician and practicing hospitalist with over 15 years of experience in hospital medicine. She has been actively involved in the Society of Hospital Medicine and has participated in and chaired multiple committees and task forces. She is currently executive vice president and chief medical officer of Hospital Medicine at Schumacher Clinical Partners, a national provider of emergency medicine and hospital medicine services. She lives in the northwest suburbs of Chicago with her family.

For years, the Society of Hospital Medicine has been asking hospital medicine programs about operational metrics in order to understand and catalog how they are functioning and evolving. After compensation, the scheduling patterns that hospital medicine groups (HMGs) are using is the most reviewed item in the report.

When hospital medicine first started, 7 days working followed by 7 days off (7-on-7-off) quickly became vogue. No one really knows how this happened, but it was most likely due to the fact that hospital medicine most closely resembled emergency medicine and scheduling similar to emergency medicine seemed to make sense (that is, 14 shifts per month). That along with the assumption that continuity of care was critical in inpatient care and would improve quality most likely resulted in the popularity of the 7-on-7-off schedule.

In the most recent survey in 2016, HMGs were once again asked to comment on how they schedule. Groups were able to choose from five scheduling options:

1. Seven days on followed by 7 days off

2. Other fixed rotation block schedules (such as 5-on 5-off; or 10-on 5-off)

3. Monday to Friday with rotating weekend coverage

4. Variable schedule

5. Other

Looking at HMG programs that serve only adult populations, a majority of them (48%) follow a fixed rotating schedule either 7 days on followed by 7 days off, or some other fixed schedule, while 31% of programs that responded stated that they used a Monday to Friday schedule. Looking at the programs as a whole, it would seem that the 7-on-7-off schedule was quickly losing popularity while the Monday to Friday schedule was increasingly being used. However, this broad generalization doesn’t really give you the full picture.

Upon analyzing the data further, we see some distinct differences arise based on program size. Small programs (fewer than 10 full-time employees [FTEs]) are much more likely to schedule a Monday to Friday schedule than any other model, whereas only a handful of large programs (greater than 20 FTEs) schedule in this way, rather choosing to use a 7-on-7-off schedule.

The last survey was done in 2014 and a lot has changed since then. Significantly more programs responded in 2016, compared with 2014 (530 vs. 355) and the majority of this increase was made of up smaller programs (fewer than 10 FTEs). Programs with four or fewer FTEs, compared with the prior survey, increased by over 400% (37 programs in 2014 vs. 151 programs in 2016). Overall, programs with fewer than 10 FTEs constituted over 50% of the total programs that responded in 2016 (whereas they made up only a third in 2014). This was particularly significant since size of the program was the one variable that determined how a program might schedule – other factors like geographic region, academic status, or primary hospital GME status did not show significant variance in how groups scheduled.

The second major change that occurred is that these same small programs (those with fewer than 10 FTEs) moved overwhelmingly to a Monday to Friday schedule. In 2014, only 3% of small programs scheduled using a Monday to Friday pattern, but in 2016 almost 50% of small programs reported scheduling in this way. This change in the overall composition of programs, with small programs now making up over 50% of the programs that reported, and the specific change in how small programs schedule results in a noteworthy decrease of programs using a 7 days on followed by 7 days off (7-on-7-off) schedule (53.8% in 2014 and only 38.1% in 2016), and a corresponding increase in the number of programs that schedule using a Monday to Friday schedule (4% in 2014 to 31% in 2016).

In distinct contrast to programs with fewer than 10 FTEs, a very similar number of programs with greater than 20 FTEs reported in 2016 as in 2014 – there was no increase in this subgroup. I’m not clear at this time if this is because there is truly no increase in the number of large programs nationally, or if there is another factor causing larger programs to under-report. The large programs that did report data in 2016 continue to utilize a 7-on-7-off schedule or another fixed rotating block schedule more than 50% of the time. In fact, the utilization of one of these two scheduling patterns increased slightly from 2014 to 2016 (from 52% to 58%). Those that did not use one of the prior mentioned scheduling patterns were most likely to schedule with a variable schedule. A Monday to Friday schedule was almost never used in programs of this size and showed no significant change from 2014 to 2016.

This snapshot highlights the changing landscape in hospital medicine. Hospital medicine is penetrating more and more into smaller and smaller hospitals, and has even made it into critical access hospitals. As recently as 5-10 years ago, it was felt that these hospitals were too small to have a hospital medicine program. This is likely one of the reasons for the increase in programs with four or fewer FTEs. There has also been increasing discontent with the 7-on-7-off schedule, which many feel is leading to burnout. Dr. Bob Wachter famously said during the closing plenary of the 2016 Society of Hospital Medicine Annual Meeting that the 7-on-7-off schedule was “a mistake.” Despite this brewing discontent, larger programs have not changed their scheduling patterns, likely because finding a another scheduling pattern that is effective, supports high-quality care, and is sustainable for such a large group is challenging.

Many people will say that there are as many different types of hospital medicine programs as there are hospital medicine programs. This is true for scheduling as for other aspects of hospital medicine operations. As we continue to grow and evolve as an industry, scheduling patterns will continue to change and evolve as well. For now, two patterns are emerging – smaller programs are utilizing a Monday to Friday schedule and larger programs are utilizing a 7-on-7-off schedule. Only time will tell if these scheduling patterns persist or continue to evolve.

Dr. George is a board certified internal medicine physician and practicing hospitalist with over 15 years of experience in hospital medicine. She has been actively involved in the Society of Hospital Medicine and has participated in and chaired multiple committees and task forces. She is currently executive vice president and chief medical officer of Hospital Medicine at Schumacher Clinical Partners, a national provider of emergency medicine and hospital medicine services. She lives in the northwest suburbs of Chicago with her family.

For years, the Society of Hospital Medicine has been asking hospital medicine programs about operational metrics in order to understand and catalog how they are functioning and evolving. After compensation, the scheduling patterns that hospital medicine groups (HMGs) are using is the most reviewed item in the report.

When hospital medicine first started, 7 days working followed by 7 days off (7-on-7-off) quickly became vogue. No one really knows how this happened, but it was most likely due to the fact that hospital medicine most closely resembled emergency medicine and scheduling similar to emergency medicine seemed to make sense (that is, 14 shifts per month). That along with the assumption that continuity of care was critical in inpatient care and would improve quality most likely resulted in the popularity of the 7-on-7-off schedule.

In the most recent survey in 2016, HMGs were once again asked to comment on how they schedule. Groups were able to choose from five scheduling options:

1. Seven days on followed by 7 days off

2. Other fixed rotation block schedules (such as 5-on 5-off; or 10-on 5-off)

3. Monday to Friday with rotating weekend coverage

4. Variable schedule

5. Other

Looking at HMG programs that serve only adult populations, a majority of them (48%) follow a fixed rotating schedule either 7 days on followed by 7 days off, or some other fixed schedule, while 31% of programs that responded stated that they used a Monday to Friday schedule. Looking at the programs as a whole, it would seem that the 7-on-7-off schedule was quickly losing popularity while the Monday to Friday schedule was increasingly being used. However, this broad generalization doesn’t really give you the full picture.

Upon analyzing the data further, we see some distinct differences arise based on program size. Small programs (fewer than 10 full-time employees [FTEs]) are much more likely to schedule a Monday to Friday schedule than any other model, whereas only a handful of large programs (greater than 20 FTEs) schedule in this way, rather choosing to use a 7-on-7-off schedule.

The last survey was done in 2014 and a lot has changed since then. Significantly more programs responded in 2016, compared with 2014 (530 vs. 355) and the majority of this increase was made of up smaller programs (fewer than 10 FTEs). Programs with four or fewer FTEs, compared with the prior survey, increased by over 400% (37 programs in 2014 vs. 151 programs in 2016). Overall, programs with fewer than 10 FTEs constituted over 50% of the total programs that responded in 2016 (whereas they made up only a third in 2014). This was particularly significant since size of the program was the one variable that determined how a program might schedule – other factors like geographic region, academic status, or primary hospital GME status did not show significant variance in how groups scheduled.

The second major change that occurred is that these same small programs (those with fewer than 10 FTEs) moved overwhelmingly to a Monday to Friday schedule. In 2014, only 3% of small programs scheduled using a Monday to Friday pattern, but in 2016 almost 50% of small programs reported scheduling in this way. This change in the overall composition of programs, with small programs now making up over 50% of the programs that reported, and the specific change in how small programs schedule results in a noteworthy decrease of programs using a 7 days on followed by 7 days off (7-on-7-off) schedule (53.8% in 2014 and only 38.1% in 2016), and a corresponding increase in the number of programs that schedule using a Monday to Friday schedule (4% in 2014 to 31% in 2016).

In distinct contrast to programs with fewer than 10 FTEs, a very similar number of programs with greater than 20 FTEs reported in 2016 as in 2014 – there was no increase in this subgroup. I’m not clear at this time if this is because there is truly no increase in the number of large programs nationally, or if there is another factor causing larger programs to under-report. The large programs that did report data in 2016 continue to utilize a 7-on-7-off schedule or another fixed rotating block schedule more than 50% of the time. In fact, the utilization of one of these two scheduling patterns increased slightly from 2014 to 2016 (from 52% to 58%). Those that did not use one of the prior mentioned scheduling patterns were most likely to schedule with a variable schedule. A Monday to Friday schedule was almost never used in programs of this size and showed no significant change from 2014 to 2016.

This snapshot highlights the changing landscape in hospital medicine. Hospital medicine is penetrating more and more into smaller and smaller hospitals, and has even made it into critical access hospitals. As recently as 5-10 years ago, it was felt that these hospitals were too small to have a hospital medicine program. This is likely one of the reasons for the increase in programs with four or fewer FTEs. There has also been increasing discontent with the 7-on-7-off schedule, which many feel is leading to burnout. Dr. Bob Wachter famously said during the closing plenary of the 2016 Society of Hospital Medicine Annual Meeting that the 7-on-7-off schedule was “a mistake.” Despite this brewing discontent, larger programs have not changed their scheduling patterns, likely because finding a another scheduling pattern that is effective, supports high-quality care, and is sustainable for such a large group is challenging.

Many people will say that there are as many different types of hospital medicine programs as there are hospital medicine programs. This is true for scheduling as for other aspects of hospital medicine operations. As we continue to grow and evolve as an industry, scheduling patterns will continue to change and evolve as well. For now, two patterns are emerging – smaller programs are utilizing a Monday to Friday schedule and larger programs are utilizing a 7-on-7-off schedule. Only time will tell if these scheduling patterns persist or continue to evolve.

Dr. George is a board certified internal medicine physician and practicing hospitalist with over 15 years of experience in hospital medicine. She has been actively involved in the Society of Hospital Medicine and has participated in and chaired multiple committees and task forces. She is currently executive vice president and chief medical officer of Hospital Medicine at Schumacher Clinical Partners, a national provider of emergency medicine and hospital medicine services. She lives in the northwest suburbs of Chicago with her family.

Pediatric hospitalists take on the challenge of antibiotic stewardship

When Carol Glaser, MD, was in training, the philosophy around antibiotic prescribing often went something like this: “Ten days of antibiotics is good, but let’s do a few more days just to be sure,” she said.

Today, however, the new mantra is “less is more.” Dr. Glaser is an experienced pediatric infectious disease physician and the lead physician for pediatric antimicrobial stewardship at The Permanente Medical Group, Kaiser Permanente, at the Oakland (Calif.) Medical Center. While antibiotic stewardship is an issue relevant to nearly all hospitalists, for pediatric patients, the considerations can be unique and particularly serious.

Dr. Shah, a pediatric infectious disease physician at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, spoke last spring at HM17, the Society of Hospital Medicine’s annual meeting. His talk drew from issues raised on pediatric hospital medicine electronic mailing lists and from audience questions. These centered on decisions regarding the use of intravenous versus oral antibiotics for pediatric patients – or what he refers to as intravenous-to-oral conversion – as well as antibiotic treatment duration.

“For many conditions in pediatrics, we used to treat with intravenous antibiotics initially – and sometimes for the entire course – and now we’re using oral antibiotics for the entire course,” Dr. Shah said. He noted that urinary tract infections were once treated with IV antibiotics in the hospital but are now routinely treated orally in an outpatient setting.

Dr. Shah cited two studies, both of which he coauthored as part of the Pediatric Research in Inpatient Settings Network, which compared intravenous versus oral antibiotics treatments given after discharge: The first, published in JAMA Pediatrics in 2014, examined treatment for osteomyelitis, while the second, which focused on complicated pneumonia, was published in Pediatrics in 2016.1,2

Both were observational, retrospective studies involving more than 2,000 children across more than 30 hospitals. The JAMA Pediatrics study found that roughly half of the patients were discharged with a peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) line, and half were prescribed oral antibiotics. In some hospitals, 100% of patients were sent home with a PICC line, and in others, all children were sent home on oral antibiotics. Although treatment failure rates were the same for both groups, 15% of the patients sent home with a PICC line had to return to the emergency department because of PICC-related complications. Some were hospitalized.1

The Pediatrics study found less variation in PICC versus oral antibiotic use across hospitals for patients with complicated pneumonia, but the treatment failure rate was slightly higher for PICC patients at 3.2%, compared with 2.6% for those on oral antibiotics. This difference, however, was not statistically significant. PICC-related complications were observed in 7.1% of patients with PICC lines also were more likely to experience adverse drug reactions, compared with patients on oral antibiotics.2

“PICC lines have some advantages, particularly when children are unable or unwilling to take oral antibiotics, but they also have risks” said Dr. Shah. “If outcomes are equivalent, why would you subject patients to the risks of a catheter? And, every time they get a fever at home with a PICC line, they need urgent evaluation for the possibility of a catheter-associated bacterial infection. There is an emotional cost, as well, to taking care of catheters in the home setting.”

Additionally, economic pressures are compelling hospitals to reduce costs and resource utilization while maintaining or improving the quality of care, Dr. Shah pointed out. “Hospitalists do many things well, and quality improvement is one of those areas. That approach really aligns with antimicrobial stewardship, and there is greater incentive with episode-based payment models and financial penalties for excess readmissions. Reducing post-discharge IV antibiotic use aligns with stewardship goals and reduces the likelihood of hospital readmissions.”

The hospital medicine division at Dr. Shah’s hospital helped assemble a multidisciplinary team involving emergency physicians, pharmacists, nursing staff, hospitalists, and infectious disease physicians to encourage the use of appropriate, narrow-spectrum antibiotics and reduce the duration of antibiotic therapies. For example, skin and soft-tissue infections that were once treated for 10-14 days are now sufficiently treated in 5-7days. These efforts to improve outcomes through better adherence to evidence-based practices, including better stewardship, earned the team the SHM Teamwork in Quality Improvement Award in 2014.

“Quality improvement is really about changing the system, and hospitalists, who excel in QI, are poised to help drive antimicrobial stewardship efforts,” Dr. Shah said.

At Oakland Medical Center, Dr. Glaser helped implement handshake rounds, an idea they adopted from a group in Colorado. Every day, with every patient, the antimicrobial stewardship team meets with representatives of the teams – pediatric intensive care, the wards, the NICU, and others – to review antibiotic treatment plans for the choice of antimicrobial drug, for the duration of treatment, and for specific conditions. “We work really closely with hospitalists and our strong pediatric pharmacy team every day to ask: ‘Do we have the right dose? Do we really need to use this antibiotic?’ ” Dr. Glaser said.

Last year, she also worked to incorporate antimicrobial stewardship principles into the hospital’s residency program. “I think the most important thing we’re doing is changing the culture,” she said. “For these young physicians, we’re giving them the knowledge to empower them rather than telling them what to do and giving them a better, fundamental understanding of infectious disease.”

For instance, most pediatric respiratory illnesses are caused by a virus, yet physicians will still prescribe antibiotics for a host of reasons – including the expectations of parents, the guesswork that can go into diagnosing a young patient who cannot describe what is wrong, and the fear that children will get sicker if an antibiotic is not started early.

“A lot of it is figuring out the best approach with the least amount of side effects but covering what we need to cover for a given patient,” she said.

A number of physicians from Dr. Glaser’s team presented stewardship data from their hospital at the July 2017 Pediatric Hospital Medicine meeting in Nashville, demonstrating that, overall, they are using fewer antibiotics and that fewer of those used are broad spectrum. This satisfies the “pillars of stewardship,” Dr. Glaser said. Use antibiotics only when you need them, use them only as long as you need, and then make sure you use the most narrow-spectrum antibiotic you possibly can, she said.

Oakland Medical Center has benefited from a strong commitment to antimicrobial stewardship efforts, Dr. Glaser said, noting that many programs may lack such support, a problem that can be one of the biggest hurdles antimicrobial stewardship efforts face. The support at her hospital “has been an immense help in getting our program to where it is today.”

References

1. Keren R, Shah SS, Srivastava R, et al. Comparative effectiveness of intravenous vs oral antibiotics for postdischarge treatment of acute osteomyelitis in children. JAMA Pediatr. 2015 Feb:169(2):120-8.

2. Shah SS, Srivastava R, Wu S, et al. Intravenous versus oral antibiotics for postdischarge treatment of complicated pneumonia. Pediatrics. 2016 Dec;138(6). pii: e20161692.

When Carol Glaser, MD, was in training, the philosophy around antibiotic prescribing often went something like this: “Ten days of antibiotics is good, but let’s do a few more days just to be sure,” she said.

Today, however, the new mantra is “less is more.” Dr. Glaser is an experienced pediatric infectious disease physician and the lead physician for pediatric antimicrobial stewardship at The Permanente Medical Group, Kaiser Permanente, at the Oakland (Calif.) Medical Center. While antibiotic stewardship is an issue relevant to nearly all hospitalists, for pediatric patients, the considerations can be unique and particularly serious.

Dr. Shah, a pediatric infectious disease physician at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, spoke last spring at HM17, the Society of Hospital Medicine’s annual meeting. His talk drew from issues raised on pediatric hospital medicine electronic mailing lists and from audience questions. These centered on decisions regarding the use of intravenous versus oral antibiotics for pediatric patients – or what he refers to as intravenous-to-oral conversion – as well as antibiotic treatment duration.

“For many conditions in pediatrics, we used to treat with intravenous antibiotics initially – and sometimes for the entire course – and now we’re using oral antibiotics for the entire course,” Dr. Shah said. He noted that urinary tract infections were once treated with IV antibiotics in the hospital but are now routinely treated orally in an outpatient setting.

Dr. Shah cited two studies, both of which he coauthored as part of the Pediatric Research in Inpatient Settings Network, which compared intravenous versus oral antibiotics treatments given after discharge: The first, published in JAMA Pediatrics in 2014, examined treatment for osteomyelitis, while the second, which focused on complicated pneumonia, was published in Pediatrics in 2016.1,2

Both were observational, retrospective studies involving more than 2,000 children across more than 30 hospitals. The JAMA Pediatrics study found that roughly half of the patients were discharged with a peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) line, and half were prescribed oral antibiotics. In some hospitals, 100% of patients were sent home with a PICC line, and in others, all children were sent home on oral antibiotics. Although treatment failure rates were the same for both groups, 15% of the patients sent home with a PICC line had to return to the emergency department because of PICC-related complications. Some were hospitalized.1

The Pediatrics study found less variation in PICC versus oral antibiotic use across hospitals for patients with complicated pneumonia, but the treatment failure rate was slightly higher for PICC patients at 3.2%, compared with 2.6% for those on oral antibiotics. This difference, however, was not statistically significant. PICC-related complications were observed in 7.1% of patients with PICC lines also were more likely to experience adverse drug reactions, compared with patients on oral antibiotics.2

“PICC lines have some advantages, particularly when children are unable or unwilling to take oral antibiotics, but they also have risks” said Dr. Shah. “If outcomes are equivalent, why would you subject patients to the risks of a catheter? And, every time they get a fever at home with a PICC line, they need urgent evaluation for the possibility of a catheter-associated bacterial infection. There is an emotional cost, as well, to taking care of catheters in the home setting.”

Additionally, economic pressures are compelling hospitals to reduce costs and resource utilization while maintaining or improving the quality of care, Dr. Shah pointed out. “Hospitalists do many things well, and quality improvement is one of those areas. That approach really aligns with antimicrobial stewardship, and there is greater incentive with episode-based payment models and financial penalties for excess readmissions. Reducing post-discharge IV antibiotic use aligns with stewardship goals and reduces the likelihood of hospital readmissions.”

The hospital medicine division at Dr. Shah’s hospital helped assemble a multidisciplinary team involving emergency physicians, pharmacists, nursing staff, hospitalists, and infectious disease physicians to encourage the use of appropriate, narrow-spectrum antibiotics and reduce the duration of antibiotic therapies. For example, skin and soft-tissue infections that were once treated for 10-14 days are now sufficiently treated in 5-7days. These efforts to improve outcomes through better adherence to evidence-based practices, including better stewardship, earned the team the SHM Teamwork in Quality Improvement Award in 2014.

“Quality improvement is really about changing the system, and hospitalists, who excel in QI, are poised to help drive antimicrobial stewardship efforts,” Dr. Shah said.

At Oakland Medical Center, Dr. Glaser helped implement handshake rounds, an idea they adopted from a group in Colorado. Every day, with every patient, the antimicrobial stewardship team meets with representatives of the teams – pediatric intensive care, the wards, the NICU, and others – to review antibiotic treatment plans for the choice of antimicrobial drug, for the duration of treatment, and for specific conditions. “We work really closely with hospitalists and our strong pediatric pharmacy team every day to ask: ‘Do we have the right dose? Do we really need to use this antibiotic?’ ” Dr. Glaser said.

Last year, she also worked to incorporate antimicrobial stewardship principles into the hospital’s residency program. “I think the most important thing we’re doing is changing the culture,” she said. “For these young physicians, we’re giving them the knowledge to empower them rather than telling them what to do and giving them a better, fundamental understanding of infectious disease.”

For instance, most pediatric respiratory illnesses are caused by a virus, yet physicians will still prescribe antibiotics for a host of reasons – including the expectations of parents, the guesswork that can go into diagnosing a young patient who cannot describe what is wrong, and the fear that children will get sicker if an antibiotic is not started early.

“A lot of it is figuring out the best approach with the least amount of side effects but covering what we need to cover for a given patient,” she said.

A number of physicians from Dr. Glaser’s team presented stewardship data from their hospital at the July 2017 Pediatric Hospital Medicine meeting in Nashville, demonstrating that, overall, they are using fewer antibiotics and that fewer of those used are broad spectrum. This satisfies the “pillars of stewardship,” Dr. Glaser said. Use antibiotics only when you need them, use them only as long as you need, and then make sure you use the most narrow-spectrum antibiotic you possibly can, she said.

Oakland Medical Center has benefited from a strong commitment to antimicrobial stewardship efforts, Dr. Glaser said, noting that many programs may lack such support, a problem that can be one of the biggest hurdles antimicrobial stewardship efforts face. The support at her hospital “has been an immense help in getting our program to where it is today.”

References

1. Keren R, Shah SS, Srivastava R, et al. Comparative effectiveness of intravenous vs oral antibiotics for postdischarge treatment of acute osteomyelitis in children. JAMA Pediatr. 2015 Feb:169(2):120-8.

2. Shah SS, Srivastava R, Wu S, et al. Intravenous versus oral antibiotics for postdischarge treatment of complicated pneumonia. Pediatrics. 2016 Dec;138(6). pii: e20161692.

When Carol Glaser, MD, was in training, the philosophy around antibiotic prescribing often went something like this: “Ten days of antibiotics is good, but let’s do a few more days just to be sure,” she said.

Today, however, the new mantra is “less is more.” Dr. Glaser is an experienced pediatric infectious disease physician and the lead physician for pediatric antimicrobial stewardship at The Permanente Medical Group, Kaiser Permanente, at the Oakland (Calif.) Medical Center. While antibiotic stewardship is an issue relevant to nearly all hospitalists, for pediatric patients, the considerations can be unique and particularly serious.

Dr. Shah, a pediatric infectious disease physician at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, spoke last spring at HM17, the Society of Hospital Medicine’s annual meeting. His talk drew from issues raised on pediatric hospital medicine electronic mailing lists and from audience questions. These centered on decisions regarding the use of intravenous versus oral antibiotics for pediatric patients – or what he refers to as intravenous-to-oral conversion – as well as antibiotic treatment duration.

“For many conditions in pediatrics, we used to treat with intravenous antibiotics initially – and sometimes for the entire course – and now we’re using oral antibiotics for the entire course,” Dr. Shah said. He noted that urinary tract infections were once treated with IV antibiotics in the hospital but are now routinely treated orally in an outpatient setting.

Dr. Shah cited two studies, both of which he coauthored as part of the Pediatric Research in Inpatient Settings Network, which compared intravenous versus oral antibiotics treatments given after discharge: The first, published in JAMA Pediatrics in 2014, examined treatment for osteomyelitis, while the second, which focused on complicated pneumonia, was published in Pediatrics in 2016.1,2

Both were observational, retrospective studies involving more than 2,000 children across more than 30 hospitals. The JAMA Pediatrics study found that roughly half of the patients were discharged with a peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) line, and half were prescribed oral antibiotics. In some hospitals, 100% of patients were sent home with a PICC line, and in others, all children were sent home on oral antibiotics. Although treatment failure rates were the same for both groups, 15% of the patients sent home with a PICC line had to return to the emergency department because of PICC-related complications. Some were hospitalized.1

The Pediatrics study found less variation in PICC versus oral antibiotic use across hospitals for patients with complicated pneumonia, but the treatment failure rate was slightly higher for PICC patients at 3.2%, compared with 2.6% for those on oral antibiotics. This difference, however, was not statistically significant. PICC-related complications were observed in 7.1% of patients with PICC lines also were more likely to experience adverse drug reactions, compared with patients on oral antibiotics.2

“PICC lines have some advantages, particularly when children are unable or unwilling to take oral antibiotics, but they also have risks” said Dr. Shah. “If outcomes are equivalent, why would you subject patients to the risks of a catheter? And, every time they get a fever at home with a PICC line, they need urgent evaluation for the possibility of a catheter-associated bacterial infection. There is an emotional cost, as well, to taking care of catheters in the home setting.”

Additionally, economic pressures are compelling hospitals to reduce costs and resource utilization while maintaining or improving the quality of care, Dr. Shah pointed out. “Hospitalists do many things well, and quality improvement is one of those areas. That approach really aligns with antimicrobial stewardship, and there is greater incentive with episode-based payment models and financial penalties for excess readmissions. Reducing post-discharge IV antibiotic use aligns with stewardship goals and reduces the likelihood of hospital readmissions.”

The hospital medicine division at Dr. Shah’s hospital helped assemble a multidisciplinary team involving emergency physicians, pharmacists, nursing staff, hospitalists, and infectious disease physicians to encourage the use of appropriate, narrow-spectrum antibiotics and reduce the duration of antibiotic therapies. For example, skin and soft-tissue infections that were once treated for 10-14 days are now sufficiently treated in 5-7days. These efforts to improve outcomes through better adherence to evidence-based practices, including better stewardship, earned the team the SHM Teamwork in Quality Improvement Award in 2014.

“Quality improvement is really about changing the system, and hospitalists, who excel in QI, are poised to help drive antimicrobial stewardship efforts,” Dr. Shah said.

At Oakland Medical Center, Dr. Glaser helped implement handshake rounds, an idea they adopted from a group in Colorado. Every day, with every patient, the antimicrobial stewardship team meets with representatives of the teams – pediatric intensive care, the wards, the NICU, and others – to review antibiotic treatment plans for the choice of antimicrobial drug, for the duration of treatment, and for specific conditions. “We work really closely with hospitalists and our strong pediatric pharmacy team every day to ask: ‘Do we have the right dose? Do we really need to use this antibiotic?’ ” Dr. Glaser said.

Last year, she also worked to incorporate antimicrobial stewardship principles into the hospital’s residency program. “I think the most important thing we’re doing is changing the culture,” she said. “For these young physicians, we’re giving them the knowledge to empower them rather than telling them what to do and giving them a better, fundamental understanding of infectious disease.”

For instance, most pediatric respiratory illnesses are caused by a virus, yet physicians will still prescribe antibiotics for a host of reasons – including the expectations of parents, the guesswork that can go into diagnosing a young patient who cannot describe what is wrong, and the fear that children will get sicker if an antibiotic is not started early.

“A lot of it is figuring out the best approach with the least amount of side effects but covering what we need to cover for a given patient,” she said.

A number of physicians from Dr. Glaser’s team presented stewardship data from their hospital at the July 2017 Pediatric Hospital Medicine meeting in Nashville, demonstrating that, overall, they are using fewer antibiotics and that fewer of those used are broad spectrum. This satisfies the “pillars of stewardship,” Dr. Glaser said. Use antibiotics only when you need them, use them only as long as you need, and then make sure you use the most narrow-spectrum antibiotic you possibly can, she said.

Oakland Medical Center has benefited from a strong commitment to antimicrobial stewardship efforts, Dr. Glaser said, noting that many programs may lack such support, a problem that can be one of the biggest hurdles antimicrobial stewardship efforts face. The support at her hospital “has been an immense help in getting our program to where it is today.”

References

1. Keren R, Shah SS, Srivastava R, et al. Comparative effectiveness of intravenous vs oral antibiotics for postdischarge treatment of acute osteomyelitis in children. JAMA Pediatr. 2015 Feb:169(2):120-8.

2. Shah SS, Srivastava R, Wu S, et al. Intravenous versus oral antibiotics for postdischarge treatment of complicated pneumonia. Pediatrics. 2016 Dec;138(6). pii: e20161692.

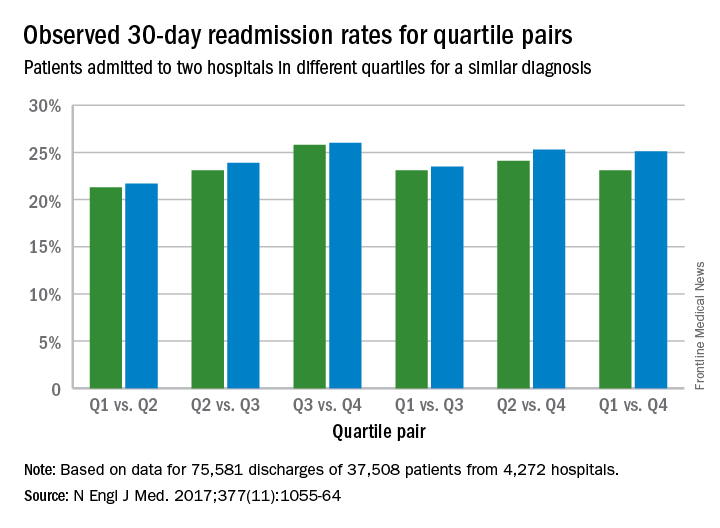

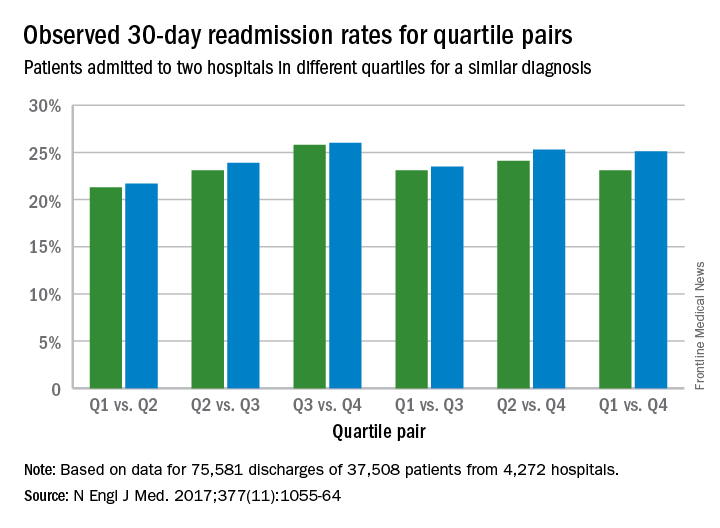

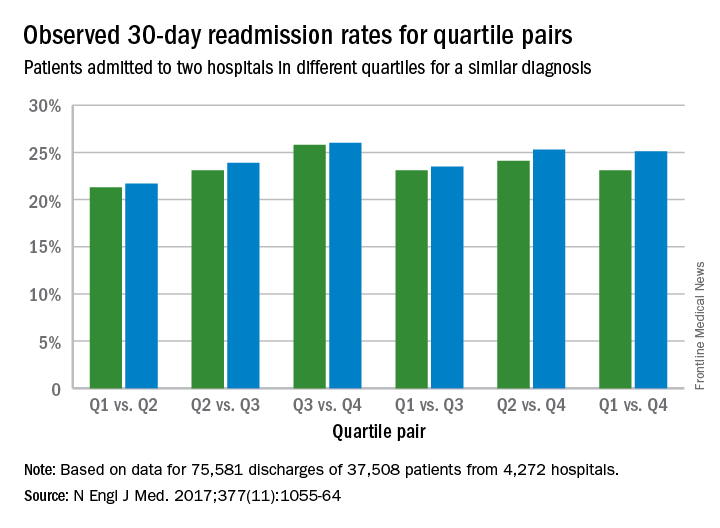

Readmission rates linked to hospital quality measures

Poorer-performing hospitals have higher readmission rates than better-performing hospitals for patients with similar diagnoses, a study shows.

Lead author Harlan M. Krumholz, MD, of Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and his colleagues analyzed Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services hospital-wide readmission data and divided data from July 2014 through June 2015 into two random samples. Researchers used the first sample to calculate the risk-standardized readmission rate within 30 days for each hospital and classified hospitals into performance quartiles, with a lower readmission rate indicating better performance. The second study sample included patients who had two admissions for similar diagnoses at different hospitals that occurred more than 1 month and less than 1 year apart. Researchers compared the observed readmission rates among patients who had been admitted to hospitals in different performance quartiles. The analysis included all discharges occurring from July 1, 2014, through June 30, 2015, from short-term acute care or critical access hospitals in the United States involving Medicare patients who were aged 65 years or older.

Results found that among the patients hospitalized more than once for similar diagnoses at different hospitals, the readmission rate was significantly higher among patients admitted to the worst-performing quartile of hospitals than among those admitted to the best-performing quartile (absolute difference in readmission rate, 2.0 percentage points; 95% confidence interval, 0.4-3.5; P = .001) (N Engl J Med. 2017. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1702321). The differences in the comparisons of the other quartiles were smaller and not significant, according to the study.

The findings suggest that hospital quality contributes at least in part to readmission rates, independent of patient factors, study authors concluded.

“This study addresses a persistent concern that national readmission measures may reflect differences in unmeasured factors rather than in hospital performance,” they said. “The findings suggest that hospital quality contributes at least in part to readmission rates, independent of patient factors. By studying patients who were admitted twice within 1 year with similar diagnoses to different hospitals, this study design was able to isolate hospital signals of performance while minimizing differences among the patients. In these cases, because the same patients had similar admissions at two hospitals, the characteristics of the patients, including their level of social disadvantage, level of education, or degree of underlying illness, were broadly the same. The alignment of the differences that we observed with the results of the CMS hospital-wide readmission measure also adds to evidence that the readmission measure classifies true differences in performance.”

Dr. Krumholz and seven coauthors reported receiving support from contracts with the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services to develop and reevaluate performance measures that are used for public reporting.

agallegos@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @legal_med

The Hospital Readmission Reduction Program (HRRP) was established in 2011 by a provision in the Affordable Care Act (ACA) requiring Medicare to reduce payments to hospitals with relatively high readmission rates for patients in traditional Medicare. Since the inception of the HRRP, readmission rates have declined across all measured diagnostic categories resulting in estimates of 565,000 fewer Medicare readmissions through 2015.1 These reductions seem to be driven by penalties demonstrated by the fact that readmissions fell more quickly at hospitals that had readmission penalties than at other hospitals. Although the severity and fairness of the penalties can be debated, the HRRP has been successful in achieving the goal of reducing readmissions.

Despite these declines seen in most hospitals, readmission rates have not declined among all hospitals. Hospitals that have higher proportions of low-income Medicare patients have not had as significant reduction in readmissions as their counterparts.2 One of the biggest complaints leveled at the HRRP program is that it is indifferent to the socioeconomic circumstances of a hospital’s patient population. In many of these hospitals, efforts to reduce readmissions have been seen as futile exercises in a patient population with complex social needs.

A study published in the journal Health Affairs found that socioeconomic factors do appear to drive many of the difference in readmission rates between safety net hospitals and their more prosperous peers. However, it also suggested that hospital performance may play a factor as well.3

The NEJM article, Hospital-Readmission Risk – Isolating Hospital Effects from Patient Effects confirms this. This well-designed review determined that hospitals, independent of a patient’s socioeconomic status, had an impact on the likelihood of patient being readmitted. The more complicated question of what higher functioning hospitals did to reduce readmissions was not addressed. It is certain that some hospitals will face greater challenges in reducing readmissions. It is difficult to determine which socioeconomic factors play the biggest role in driving readmission rates and even more difficult to change them. This study also demonstrates that despite challenging conditions, reductions in readmissions can occur.

As the primary focus and leader of health care in most communities, hospitals are best equipped to reach into the community and to develop successful transition programs that limit readmissions and begin to addressee complex social needs. Of course this must be a coordinated effort among many groups, but the hospital and its organization is in the right position to take a leading role. It is essential that hospitalists, who are on the front lines of this process, play a significant role.Many hospitals with patients who have complex needs are rising to the occasion. Motivated by the HRRP, unique innovations to improve care transitions out of hospitals are being developed. Hospitals that are serving low socioeconomic populations are finding innovative ways to reduce readmissions. These include identifying high-risk social conditions driving readmissions, intensive discharge planning, and deploying community health care workers. A key component of this has been addressing the opioid epidemic.Despite some opposition, the HHRP has worked by aligning financial incentives with good health care. The program was successful not by developing complicated metrics, but rather by simply providing financial incentives for good care and then allowing innovation to develop independently. Hopefully this study further promotes these efforts

Kevin Conrad, MD, is medical director of community affairs and healthy policy at Ochsner Health System, New Orleans.

References

1. Zuckerman RB et al. Readmissions, observation, and the hospital readmissions reduction program. N Engl J Med. 2016 April 21;374:1543-1551.

2. Jencks SF et al. Hospitalizations among patients in the Medicare Fee-for-Service Program. N Engl J Med. 2009.360(14):1418-1428; Epstein AM et al. The relationship between hospital admission rates and rehospitalizations. N Engl J Med. 2011. 365(24):2287-2295.

3. Kahn C et al. Assessing Medicare’s hospital Pay-for-Performance programs and whether they are achieving their goals. Health Affairs. 2015 Aug;34(8).

The Hospital Readmission Reduction Program (HRRP) was established in 2011 by a provision in the Affordable Care Act (ACA) requiring Medicare to reduce payments to hospitals with relatively high readmission rates for patients in traditional Medicare. Since the inception of the HRRP, readmission rates have declined across all measured diagnostic categories resulting in estimates of 565,000 fewer Medicare readmissions through 2015.1 These reductions seem to be driven by penalties demonstrated by the fact that readmissions fell more quickly at hospitals that had readmission penalties than at other hospitals. Although the severity and fairness of the penalties can be debated, the HRRP has been successful in achieving the goal of reducing readmissions.

Despite these declines seen in most hospitals, readmission rates have not declined among all hospitals. Hospitals that have higher proportions of low-income Medicare patients have not had as significant reduction in readmissions as their counterparts.2 One of the biggest complaints leveled at the HRRP program is that it is indifferent to the socioeconomic circumstances of a hospital’s patient population. In many of these hospitals, efforts to reduce readmissions have been seen as futile exercises in a patient population with complex social needs.

A study published in the journal Health Affairs found that socioeconomic factors do appear to drive many of the difference in readmission rates between safety net hospitals and their more prosperous peers. However, it also suggested that hospital performance may play a factor as well.3

The NEJM article, Hospital-Readmission Risk – Isolating Hospital Effects from Patient Effects confirms this. This well-designed review determined that hospitals, independent of a patient’s socioeconomic status, had an impact on the likelihood of patient being readmitted. The more complicated question of what higher functioning hospitals did to reduce readmissions was not addressed. It is certain that some hospitals will face greater challenges in reducing readmissions. It is difficult to determine which socioeconomic factors play the biggest role in driving readmission rates and even more difficult to change them. This study also demonstrates that despite challenging conditions, reductions in readmissions can occur.

As the primary focus and leader of health care in most communities, hospitals are best equipped to reach into the community and to develop successful transition programs that limit readmissions and begin to addressee complex social needs. Of course this must be a coordinated effort among many groups, but the hospital and its organization is in the right position to take a leading role. It is essential that hospitalists, who are on the front lines of this process, play a significant role.Many hospitals with patients who have complex needs are rising to the occasion. Motivated by the HRRP, unique innovations to improve care transitions out of hospitals are being developed. Hospitals that are serving low socioeconomic populations are finding innovative ways to reduce readmissions. These include identifying high-risk social conditions driving readmissions, intensive discharge planning, and deploying community health care workers. A key component of this has been addressing the opioid epidemic.Despite some opposition, the HHRP has worked by aligning financial incentives with good health care. The program was successful not by developing complicated metrics, but rather by simply providing financial incentives for good care and then allowing innovation to develop independently. Hopefully this study further promotes these efforts

Kevin Conrad, MD, is medical director of community affairs and healthy policy at Ochsner Health System, New Orleans.

References

1. Zuckerman RB et al. Readmissions, observation, and the hospital readmissions reduction program. N Engl J Med. 2016 April 21;374:1543-1551.

2. Jencks SF et al. Hospitalizations among patients in the Medicare Fee-for-Service Program. N Engl J Med. 2009.360(14):1418-1428; Epstein AM et al. The relationship between hospital admission rates and rehospitalizations. N Engl J Med. 2011. 365(24):2287-2295.

3. Kahn C et al. Assessing Medicare’s hospital Pay-for-Performance programs and whether they are achieving their goals. Health Affairs. 2015 Aug;34(8).

The Hospital Readmission Reduction Program (HRRP) was established in 2011 by a provision in the Affordable Care Act (ACA) requiring Medicare to reduce payments to hospitals with relatively high readmission rates for patients in traditional Medicare. Since the inception of the HRRP, readmission rates have declined across all measured diagnostic categories resulting in estimates of 565,000 fewer Medicare readmissions through 2015.1 These reductions seem to be driven by penalties demonstrated by the fact that readmissions fell more quickly at hospitals that had readmission penalties than at other hospitals. Although the severity and fairness of the penalties can be debated, the HRRP has been successful in achieving the goal of reducing readmissions.

Despite these declines seen in most hospitals, readmission rates have not declined among all hospitals. Hospitals that have higher proportions of low-income Medicare patients have not had as significant reduction in readmissions as their counterparts.2 One of the biggest complaints leveled at the HRRP program is that it is indifferent to the socioeconomic circumstances of a hospital’s patient population. In many of these hospitals, efforts to reduce readmissions have been seen as futile exercises in a patient population with complex social needs.

A study published in the journal Health Affairs found that socioeconomic factors do appear to drive many of the difference in readmission rates between safety net hospitals and their more prosperous peers. However, it also suggested that hospital performance may play a factor as well.3

The NEJM article, Hospital-Readmission Risk – Isolating Hospital Effects from Patient Effects confirms this. This well-designed review determined that hospitals, independent of a patient’s socioeconomic status, had an impact on the likelihood of patient being readmitted. The more complicated question of what higher functioning hospitals did to reduce readmissions was not addressed. It is certain that some hospitals will face greater challenges in reducing readmissions. It is difficult to determine which socioeconomic factors play the biggest role in driving readmission rates and even more difficult to change them. This study also demonstrates that despite challenging conditions, reductions in readmissions can occur.

As the primary focus and leader of health care in most communities, hospitals are best equipped to reach into the community and to develop successful transition programs that limit readmissions and begin to addressee complex social needs. Of course this must be a coordinated effort among many groups, but the hospital and its organization is in the right position to take a leading role. It is essential that hospitalists, who are on the front lines of this process, play a significant role.Many hospitals with patients who have complex needs are rising to the occasion. Motivated by the HRRP, unique innovations to improve care transitions out of hospitals are being developed. Hospitals that are serving low socioeconomic populations are finding innovative ways to reduce readmissions. These include identifying high-risk social conditions driving readmissions, intensive discharge planning, and deploying community health care workers. A key component of this has been addressing the opioid epidemic.Despite some opposition, the HHRP has worked by aligning financial incentives with good health care. The program was successful not by developing complicated metrics, but rather by simply providing financial incentives for good care and then allowing innovation to develop independently. Hopefully this study further promotes these efforts

Kevin Conrad, MD, is medical director of community affairs and healthy policy at Ochsner Health System, New Orleans.

References

1. Zuckerman RB et al. Readmissions, observation, and the hospital readmissions reduction program. N Engl J Med. 2016 April 21;374:1543-1551.

2. Jencks SF et al. Hospitalizations among patients in the Medicare Fee-for-Service Program. N Engl J Med. 2009.360(14):1418-1428; Epstein AM et al. The relationship between hospital admission rates and rehospitalizations. N Engl J Med. 2011. 365(24):2287-2295.

3. Kahn C et al. Assessing Medicare’s hospital Pay-for-Performance programs and whether they are achieving their goals. Health Affairs. 2015 Aug;34(8).

Poorer-performing hospitals have higher readmission rates than better-performing hospitals for patients with similar diagnoses, a study shows.

Lead author Harlan M. Krumholz, MD, of Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and his colleagues analyzed Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services hospital-wide readmission data and divided data from July 2014 through June 2015 into two random samples. Researchers used the first sample to calculate the risk-standardized readmission rate within 30 days for each hospital and classified hospitals into performance quartiles, with a lower readmission rate indicating better performance. The second study sample included patients who had two admissions for similar diagnoses at different hospitals that occurred more than 1 month and less than 1 year apart. Researchers compared the observed readmission rates among patients who had been admitted to hospitals in different performance quartiles. The analysis included all discharges occurring from July 1, 2014, through June 30, 2015, from short-term acute care or critical access hospitals in the United States involving Medicare patients who were aged 65 years or older.

Results found that among the patients hospitalized more than once for similar diagnoses at different hospitals, the readmission rate was significantly higher among patients admitted to the worst-performing quartile of hospitals than among those admitted to the best-performing quartile (absolute difference in readmission rate, 2.0 percentage points; 95% confidence interval, 0.4-3.5; P = .001) (N Engl J Med. 2017. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1702321). The differences in the comparisons of the other quartiles were smaller and not significant, according to the study.

The findings suggest that hospital quality contributes at least in part to readmission rates, independent of patient factors, study authors concluded.

“This study addresses a persistent concern that national readmission measures may reflect differences in unmeasured factors rather than in hospital performance,” they said. “The findings suggest that hospital quality contributes at least in part to readmission rates, independent of patient factors. By studying patients who were admitted twice within 1 year with similar diagnoses to different hospitals, this study design was able to isolate hospital signals of performance while minimizing differences among the patients. In these cases, because the same patients had similar admissions at two hospitals, the characteristics of the patients, including their level of social disadvantage, level of education, or degree of underlying illness, were broadly the same. The alignment of the differences that we observed with the results of the CMS hospital-wide readmission measure also adds to evidence that the readmission measure classifies true differences in performance.”

Dr. Krumholz and seven coauthors reported receiving support from contracts with the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services to develop and reevaluate performance measures that are used for public reporting.

agallegos@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @legal_med

Poorer-performing hospitals have higher readmission rates than better-performing hospitals for patients with similar diagnoses, a study shows.

Lead author Harlan M. Krumholz, MD, of Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and his colleagues analyzed Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services hospital-wide readmission data and divided data from July 2014 through June 2015 into two random samples. Researchers used the first sample to calculate the risk-standardized readmission rate within 30 days for each hospital and classified hospitals into performance quartiles, with a lower readmission rate indicating better performance. The second study sample included patients who had two admissions for similar diagnoses at different hospitals that occurred more than 1 month and less than 1 year apart. Researchers compared the observed readmission rates among patients who had been admitted to hospitals in different performance quartiles. The analysis included all discharges occurring from July 1, 2014, through June 30, 2015, from short-term acute care or critical access hospitals in the United States involving Medicare patients who were aged 65 years or older.

Results found that among the patients hospitalized more than once for similar diagnoses at different hospitals, the readmission rate was significantly higher among patients admitted to the worst-performing quartile of hospitals than among those admitted to the best-performing quartile (absolute difference in readmission rate, 2.0 percentage points; 95% confidence interval, 0.4-3.5; P = .001) (N Engl J Med. 2017. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1702321). The differences in the comparisons of the other quartiles were smaller and not significant, according to the study.

The findings suggest that hospital quality contributes at least in part to readmission rates, independent of patient factors, study authors concluded.

“This study addresses a persistent concern that national readmission measures may reflect differences in unmeasured factors rather than in hospital performance,” they said. “The findings suggest that hospital quality contributes at least in part to readmission rates, independent of patient factors. By studying patients who were admitted twice within 1 year with similar diagnoses to different hospitals, this study design was able to isolate hospital signals of performance while minimizing differences among the patients. In these cases, because the same patients had similar admissions at two hospitals, the characteristics of the patients, including their level of social disadvantage, level of education, or degree of underlying illness, were broadly the same. The alignment of the differences that we observed with the results of the CMS hospital-wide readmission measure also adds to evidence that the readmission measure classifies true differences in performance.”

Dr. Krumholz and seven coauthors reported receiving support from contracts with the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services to develop and reevaluate performance measures that are used for public reporting.

agallegos@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @legal_med

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The readmission rate was significantly higher among patients admitted to the worst-performing quartile of hospitals than among those admitted to the best-performing quartile (absolute difference in readmission rate, 2.0 percentage points).

Data source: Analysis of Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services hospital-wide readmission data from July 2014 through June 2015.

Disclosures: Dr. Krumholz and seven coauthors reported receiving support from contracts with the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services to develop and reevaluate performance measures that are used for public reporting.

Thinking about the basic science of quality improvement

Editor’s note: The Society of Hospital Medicine’s (SHM’s) Physician in Training Committee launched a scholarship program in 2015 for medical students to help transform health care and revolutionize patient care. The program has been expanded for the 2017-18 year, offering two options for students to receive funding and engage in scholarly work during their first, second and third years of medical school. As a part of the longitudinal (18-month) program, recipients are required to write about their experience on a monthly basis.

I reviewed recent literature about my research topic, which is clinical pathways for hospitalized injection drug users due to injection-related infection sequelae and came up with my research proposal. As part of a scholarly pursuit, I believe having a theoretical background of quality improvement to be important. Before further diving into the research topic, I also generated a small reading list of the “basic science” of quality improvement, which covers topics of general operational science and those in health care applications.

What makes standardization in health care difficult? In my operations class at Tuck School of Business, we watched a video showing former Soviet Union ophthalmologists performing “assembly line” cataract surgery. It includes multiple surgeons sitting around multiple rotating tables, each surgeon performing exactly one step of the cataract surgery. I recall all my classmates were amused by the video, because it appeared both impractical (as one surgeon was almost chasing the table) as well as slightly de-humanizing. In the health care setting, standardization can be difficult. The service is intrinsically complex, it is difficult to define processes and to measure outcomes, and standardization can create tension secondary to physician autonomy and organizational culture.

In service delivery, the person (the patient in health care organizations) is part of the production process. Patients by nature are not standard inputs. They assume different pre-existing conditions and have different preferences for clinical and non-clinical services/processes. The medical service itself, consisting of both clinical and operational processes, sometimes can be difficult to qualify and measure. A hospital can control patient flow by managing appointment and beds allocation. Clinical pathways can be defined for different diseases. However, patients can encounter undiscovered diseases or complications during the treatment, making the clinical service different and unpredictable.

Lastly standardization can encounter resistance from physicians and other health care providers. “Patients are not cars” is a phrase commonly used when discussing standardization. A health care organization needs to have not only tools, but also the cultural and managerial foundations to carry out changes. I am looking forward to using this project opportunity to further explore the local application of quality improvement.

Yun Li is an MD/MBA student attending Geisel School of Medicine and Tuck School of Business at Dartmouth. She obtained her Bachelor of Arts degree from Hanover College double-majoring in Economics and Biological Chemistry. Ms. Li participated in research in injury epidemiology and genetics, and has conducted studies on traditional Tibetan medicine, rural health, health NGOs, and digital health. Her career interest is practicing hospital medicine and geriatrics as a clinician/administrator, either in the US or China. Ms. Li is a student member of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Editor’s note: The Society of Hospital Medicine’s (SHM’s) Physician in Training Committee launched a scholarship program in 2015 for medical students to help transform health care and revolutionize patient care. The program has been expanded for the 2017-18 year, offering two options for students to receive funding and engage in scholarly work during their first, second and third years of medical school. As a part of the longitudinal (18-month) program, recipients are required to write about their experience on a monthly basis.

I reviewed recent literature about my research topic, which is clinical pathways for hospitalized injection drug users due to injection-related infection sequelae and came up with my research proposal. As part of a scholarly pursuit, I believe having a theoretical background of quality improvement to be important. Before further diving into the research topic, I also generated a small reading list of the “basic science” of quality improvement, which covers topics of general operational science and those in health care applications.

What makes standardization in health care difficult? In my operations class at Tuck School of Business, we watched a video showing former Soviet Union ophthalmologists performing “assembly line” cataract surgery. It includes multiple surgeons sitting around multiple rotating tables, each surgeon performing exactly one step of the cataract surgery. I recall all my classmates were amused by the video, because it appeared both impractical (as one surgeon was almost chasing the table) as well as slightly de-humanizing. In the health care setting, standardization can be difficult. The service is intrinsically complex, it is difficult to define processes and to measure outcomes, and standardization can create tension secondary to physician autonomy and organizational culture.