User login

FDA will strengthen heart attack, stroke risk warnings for all NSAIDs

The Food and Drug Administration has taken new action to strengthen existing warning labels about the increased risk of heart attack or stroke with the use of prescription and over-the-counter nonaspirin nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

In a July 9 drug safety communication, the agency did not provide the exact language that will be used on NSAID labels, but said that they “will be revised to reflect” information describing that:

• The risk of heart attack or stroke can occur as early as the first weeks of using an NSAID.

• The risk may increase with longer use and at higher doses of the NSAID.

• The drugs can increase the risk of heart attack or stroke even in patients without heart disease or risk factors for heart disease, but patients with heart disease or risk factors for it have a greater likelihood of heart attack or stroke following NSAID use.

• Treatment with NSAIDs following a first heart attack increases the risk of death in the first year after the heart attack, compared with patients who were not treated with NSAIDs after their first heart attack.

• NSAID use increases the risk of heart failure.

The new wording will also note that although newer information may suggest that the risk for heart attack or stroke is not the same for all NSAIDs, it “is not sufficient for us to determine that the risk of any particular NSAID is definitely higher or lower than that of any other particular NSAID.”

*The update to NSAID labels follows the recommendations given by panel members from a joint meeting of the FDA’s Arthritis Advisory Committee and the Drug Safety and Risk Management Advisory Committee in February 2014 in which there was a split vote (14-11) that was slightly in favor of rewording the warning labeling for NSAIDs in regard to the drug class’s current labeling, which implies that the cardiovascular thrombotic risk is not substantial with short treatment courses. At that meeting, the panelists also voted 16-9 that there were not enough data to suggest that naproxen presented a substantially lower risk of CV events than did either ibuprofen or selective NSAIDs, such as cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors.

The FDA made its decision based on a comprehensive review of the data presented during that meeting.

*Correction, 7/16/2015: An earlier version of this story misstated the FDA panels’ recommendation for labeling changes.

The Food and Drug Administration has taken new action to strengthen existing warning labels about the increased risk of heart attack or stroke with the use of prescription and over-the-counter nonaspirin nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

In a July 9 drug safety communication, the agency did not provide the exact language that will be used on NSAID labels, but said that they “will be revised to reflect” information describing that:

• The risk of heart attack or stroke can occur as early as the first weeks of using an NSAID.

• The risk may increase with longer use and at higher doses of the NSAID.

• The drugs can increase the risk of heart attack or stroke even in patients without heart disease or risk factors for heart disease, but patients with heart disease or risk factors for it have a greater likelihood of heart attack or stroke following NSAID use.

• Treatment with NSAIDs following a first heart attack increases the risk of death in the first year after the heart attack, compared with patients who were not treated with NSAIDs after their first heart attack.

• NSAID use increases the risk of heart failure.

The new wording will also note that although newer information may suggest that the risk for heart attack or stroke is not the same for all NSAIDs, it “is not sufficient for us to determine that the risk of any particular NSAID is definitely higher or lower than that of any other particular NSAID.”

*The update to NSAID labels follows the recommendations given by panel members from a joint meeting of the FDA’s Arthritis Advisory Committee and the Drug Safety and Risk Management Advisory Committee in February 2014 in which there was a split vote (14-11) that was slightly in favor of rewording the warning labeling for NSAIDs in regard to the drug class’s current labeling, which implies that the cardiovascular thrombotic risk is not substantial with short treatment courses. At that meeting, the panelists also voted 16-9 that there were not enough data to suggest that naproxen presented a substantially lower risk of CV events than did either ibuprofen or selective NSAIDs, such as cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors.

The FDA made its decision based on a comprehensive review of the data presented during that meeting.

*Correction, 7/16/2015: An earlier version of this story misstated the FDA panels’ recommendation for labeling changes.

The Food and Drug Administration has taken new action to strengthen existing warning labels about the increased risk of heart attack or stroke with the use of prescription and over-the-counter nonaspirin nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

In a July 9 drug safety communication, the agency did not provide the exact language that will be used on NSAID labels, but said that they “will be revised to reflect” information describing that:

• The risk of heart attack or stroke can occur as early as the first weeks of using an NSAID.

• The risk may increase with longer use and at higher doses of the NSAID.

• The drugs can increase the risk of heart attack or stroke even in patients without heart disease or risk factors for heart disease, but patients with heart disease or risk factors for it have a greater likelihood of heart attack or stroke following NSAID use.

• Treatment with NSAIDs following a first heart attack increases the risk of death in the first year after the heart attack, compared with patients who were not treated with NSAIDs after their first heart attack.

• NSAID use increases the risk of heart failure.

The new wording will also note that although newer information may suggest that the risk for heart attack or stroke is not the same for all NSAIDs, it “is not sufficient for us to determine that the risk of any particular NSAID is definitely higher or lower than that of any other particular NSAID.”

*The update to NSAID labels follows the recommendations given by panel members from a joint meeting of the FDA’s Arthritis Advisory Committee and the Drug Safety and Risk Management Advisory Committee in February 2014 in which there was a split vote (14-11) that was slightly in favor of rewording the warning labeling for NSAIDs in regard to the drug class’s current labeling, which implies that the cardiovascular thrombotic risk is not substantial with short treatment courses. At that meeting, the panelists also voted 16-9 that there were not enough data to suggest that naproxen presented a substantially lower risk of CV events than did either ibuprofen or selective NSAIDs, such as cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors.

The FDA made its decision based on a comprehensive review of the data presented during that meeting.

*Correction, 7/16/2015: An earlier version of this story misstated the FDA panels’ recommendation for labeling changes.

Updated acute stroke guideline boosts thrombectomy

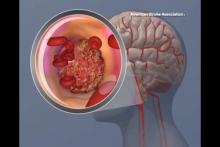

Pivotal new high-quality evidence from randomized clinical trials and other sources published since 2013 has prompted the American Heart Association and the American Stroke Association to update their joint clinical practice guideline on endovascular treatment of acute ischemic stroke.

The revisions were published online June 29 in Stroke.

Unchanged is the key recommendation that intravenous recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator (r-tPA) remain the mainstay of initial therapy, even if endovascular treatment is being considered. But a new recommendation adds that a period of observation to assess patients’ clinical response to r-tPA before proceeding with endovascular therapy is not necessary and is not advisable, said Dr. William J. Powers, chair of the guideline writing committee and professor and chairman of the department of neurology, University of North Carolina, Durham, and his associates.

Most of the updates pertain to the use of a stent retriever, which is now recommended for all patients with acute ischemic stroke who meet these seven criteria:

1. A prestroke modified Rankin scale (mRS) score of 0-1.

2. Receipt of r-tPA within 4.5 hours of symptom onset.

3. Causative occlusion of the internal carotid artery or proximal middle cerebral artery.

4. Age of 18 years or older.

5. A National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score of 6 or greater.

6. An Alberta Stroke Program Early CT Score (ASPECTS) of 6 or greater.

7. Initiation of the procedure within 6 hours of symptom onset.

Use of stent retrievers also is now considered “reasonable” in carefully selected patients with occlusion of the anterior circulation who have contraindications to r-tPA, such as current use of anticoagulants, prior stroke, serious head trauma, or hemorrhagic coagulopathy. It also may be reasonable in selected patients who have causative occlusion of the M2 or M3 portion of the middle cerebral arteries, anterior cerebral arteries, vertebral arteries, basilar artery, or posterior cerebral arteries, although the benefits are “uncertain” in this patient population.

Similarly, endovascular therapy using stent retrievers may be reasonable for some patients younger than age 18 who otherwise meet the seven criteria, even though the benefits of treatment haven’t been established in this age group. And it likewise may be reasonable in patients with prestroke mRS scores greater than 1, an ASPECTS of less than 6, or NIHSS scores of less than 6 if there is causative occlusion of the internal carotid artery or the proximal middle cerebral artery.

The updated guideline also says that stent retrievers are preferable to the Merci device, but that other mechanical thrombectomy devices may be reasonable to use in some circumstances. And adjunctive use of a proximal balloon guide catheter or a large-bore distal access catheter rather than a cervical guide catheter along with stent retrievers also may be beneficial.

In addition, “the technical goal of the thrombectomy procedure should be a TICI [Thrombolysis in Cerebral Infarction] 2b/3 angiographic result to maximize the probability of a good functional outcome. Use of salvage technical adjuncts including intra-arterial fibrinolysis may be reasonable to achieve these angiographic results, if completed within 6 hours of symptom onset,” the guideline states (Stroke 2015 June 29 [doi:10.1161/STR.0000000000000074]).

Also with regard to intra-arterial rather than intravenous fibrinolysis, stent retrievers are now preferable to intra-arterial fibrinolysis as first-line therapy.

The updated guideline also has added the recommendation that conscious sedation may be preferable to general anesthesia during endovascular therapy, depending on patient risk factors, tolerance of the procedure, and other clinical characteristics. It also revised recommendations addressing imaging studies and systems of stroke care.

Five prospective, randomized controlled trials have come out in the past few months, and triggered a revolution in acute stroke therapy. All five studies – MR CLEAN, ESCAPE, EXTENT IA, SWIFT PRIME, and REVASCAT – were halted early because of the significant advantage mechanical endovascular therapy with stents or thrombus retrieval devices demonstrated over standard therapy featuring clot thrombolysis with r-tPA.

Collectively, the five trials showed a 60% greater chance for good functional recovery from stroke with endovascular interventions. The rate of a favorable neurologic outcome as reflected in a modified Rankin score of 0-2 was 48% with the use of stent/retriever devices, compared with 30% with thrombolysis alone, said Dr. Petr Widimsky, professor and chair of the cardiology department at Charles University in Prague, at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EuroPCR) held in Paris in May.

The American Academy of Neurology “affirms the value of this guideline as an educational tool for neurologists.” The revised guideline is endorsed by the American Association of Neurological Surgeons, the Congress of Neurological Surgeons, the American Society of Neuroradiology, and the Society of Vascular and Interventional Neurology. A copy of the document is available at http://myamericanheart.org/statements.

Pivotal new high-quality evidence from randomized clinical trials and other sources published since 2013 has prompted the American Heart Association and the American Stroke Association to update their joint clinical practice guideline on endovascular treatment of acute ischemic stroke.

The revisions were published online June 29 in Stroke.

Unchanged is the key recommendation that intravenous recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator (r-tPA) remain the mainstay of initial therapy, even if endovascular treatment is being considered. But a new recommendation adds that a period of observation to assess patients’ clinical response to r-tPA before proceeding with endovascular therapy is not necessary and is not advisable, said Dr. William J. Powers, chair of the guideline writing committee and professor and chairman of the department of neurology, University of North Carolina, Durham, and his associates.

Most of the updates pertain to the use of a stent retriever, which is now recommended for all patients with acute ischemic stroke who meet these seven criteria:

1. A prestroke modified Rankin scale (mRS) score of 0-1.

2. Receipt of r-tPA within 4.5 hours of symptom onset.

3. Causative occlusion of the internal carotid artery or proximal middle cerebral artery.

4. Age of 18 years or older.

5. A National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score of 6 or greater.

6. An Alberta Stroke Program Early CT Score (ASPECTS) of 6 or greater.

7. Initiation of the procedure within 6 hours of symptom onset.

Use of stent retrievers also is now considered “reasonable” in carefully selected patients with occlusion of the anterior circulation who have contraindications to r-tPA, such as current use of anticoagulants, prior stroke, serious head trauma, or hemorrhagic coagulopathy. It also may be reasonable in selected patients who have causative occlusion of the M2 or M3 portion of the middle cerebral arteries, anterior cerebral arteries, vertebral arteries, basilar artery, or posterior cerebral arteries, although the benefits are “uncertain” in this patient population.

Similarly, endovascular therapy using stent retrievers may be reasonable for some patients younger than age 18 who otherwise meet the seven criteria, even though the benefits of treatment haven’t been established in this age group. And it likewise may be reasonable in patients with prestroke mRS scores greater than 1, an ASPECTS of less than 6, or NIHSS scores of less than 6 if there is causative occlusion of the internal carotid artery or the proximal middle cerebral artery.

The updated guideline also says that stent retrievers are preferable to the Merci device, but that other mechanical thrombectomy devices may be reasonable to use in some circumstances. And adjunctive use of a proximal balloon guide catheter or a large-bore distal access catheter rather than a cervical guide catheter along with stent retrievers also may be beneficial.

In addition, “the technical goal of the thrombectomy procedure should be a TICI [Thrombolysis in Cerebral Infarction] 2b/3 angiographic result to maximize the probability of a good functional outcome. Use of salvage technical adjuncts including intra-arterial fibrinolysis may be reasonable to achieve these angiographic results, if completed within 6 hours of symptom onset,” the guideline states (Stroke 2015 June 29 [doi:10.1161/STR.0000000000000074]).

Also with regard to intra-arterial rather than intravenous fibrinolysis, stent retrievers are now preferable to intra-arterial fibrinolysis as first-line therapy.

The updated guideline also has added the recommendation that conscious sedation may be preferable to general anesthesia during endovascular therapy, depending on patient risk factors, tolerance of the procedure, and other clinical characteristics. It also revised recommendations addressing imaging studies and systems of stroke care.

Five prospective, randomized controlled trials have come out in the past few months, and triggered a revolution in acute stroke therapy. All five studies – MR CLEAN, ESCAPE, EXTENT IA, SWIFT PRIME, and REVASCAT – were halted early because of the significant advantage mechanical endovascular therapy with stents or thrombus retrieval devices demonstrated over standard therapy featuring clot thrombolysis with r-tPA.

Collectively, the five trials showed a 60% greater chance for good functional recovery from stroke with endovascular interventions. The rate of a favorable neurologic outcome as reflected in a modified Rankin score of 0-2 was 48% with the use of stent/retriever devices, compared with 30% with thrombolysis alone, said Dr. Petr Widimsky, professor and chair of the cardiology department at Charles University in Prague, at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EuroPCR) held in Paris in May.

The American Academy of Neurology “affirms the value of this guideline as an educational tool for neurologists.” The revised guideline is endorsed by the American Association of Neurological Surgeons, the Congress of Neurological Surgeons, the American Society of Neuroradiology, and the Society of Vascular and Interventional Neurology. A copy of the document is available at http://myamericanheart.org/statements.

Pivotal new high-quality evidence from randomized clinical trials and other sources published since 2013 has prompted the American Heart Association and the American Stroke Association to update their joint clinical practice guideline on endovascular treatment of acute ischemic stroke.

The revisions were published online June 29 in Stroke.

Unchanged is the key recommendation that intravenous recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator (r-tPA) remain the mainstay of initial therapy, even if endovascular treatment is being considered. But a new recommendation adds that a period of observation to assess patients’ clinical response to r-tPA before proceeding with endovascular therapy is not necessary and is not advisable, said Dr. William J. Powers, chair of the guideline writing committee and professor and chairman of the department of neurology, University of North Carolina, Durham, and his associates.

Most of the updates pertain to the use of a stent retriever, which is now recommended for all patients with acute ischemic stroke who meet these seven criteria:

1. A prestroke modified Rankin scale (mRS) score of 0-1.

2. Receipt of r-tPA within 4.5 hours of symptom onset.

3. Causative occlusion of the internal carotid artery or proximal middle cerebral artery.

4. Age of 18 years or older.

5. A National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score of 6 or greater.

6. An Alberta Stroke Program Early CT Score (ASPECTS) of 6 or greater.

7. Initiation of the procedure within 6 hours of symptom onset.

Use of stent retrievers also is now considered “reasonable” in carefully selected patients with occlusion of the anterior circulation who have contraindications to r-tPA, such as current use of anticoagulants, prior stroke, serious head trauma, or hemorrhagic coagulopathy. It also may be reasonable in selected patients who have causative occlusion of the M2 or M3 portion of the middle cerebral arteries, anterior cerebral arteries, vertebral arteries, basilar artery, or posterior cerebral arteries, although the benefits are “uncertain” in this patient population.

Similarly, endovascular therapy using stent retrievers may be reasonable for some patients younger than age 18 who otherwise meet the seven criteria, even though the benefits of treatment haven’t been established in this age group. And it likewise may be reasonable in patients with prestroke mRS scores greater than 1, an ASPECTS of less than 6, or NIHSS scores of less than 6 if there is causative occlusion of the internal carotid artery or the proximal middle cerebral artery.

The updated guideline also says that stent retrievers are preferable to the Merci device, but that other mechanical thrombectomy devices may be reasonable to use in some circumstances. And adjunctive use of a proximal balloon guide catheter or a large-bore distal access catheter rather than a cervical guide catheter along with stent retrievers also may be beneficial.

In addition, “the technical goal of the thrombectomy procedure should be a TICI [Thrombolysis in Cerebral Infarction] 2b/3 angiographic result to maximize the probability of a good functional outcome. Use of salvage technical adjuncts including intra-arterial fibrinolysis may be reasonable to achieve these angiographic results, if completed within 6 hours of symptom onset,” the guideline states (Stroke 2015 June 29 [doi:10.1161/STR.0000000000000074]).

Also with regard to intra-arterial rather than intravenous fibrinolysis, stent retrievers are now preferable to intra-arterial fibrinolysis as first-line therapy.

The updated guideline also has added the recommendation that conscious sedation may be preferable to general anesthesia during endovascular therapy, depending on patient risk factors, tolerance of the procedure, and other clinical characteristics. It also revised recommendations addressing imaging studies and systems of stroke care.

Five prospective, randomized controlled trials have come out in the past few months, and triggered a revolution in acute stroke therapy. All five studies – MR CLEAN, ESCAPE, EXTENT IA, SWIFT PRIME, and REVASCAT – were halted early because of the significant advantage mechanical endovascular therapy with stents or thrombus retrieval devices demonstrated over standard therapy featuring clot thrombolysis with r-tPA.

Collectively, the five trials showed a 60% greater chance for good functional recovery from stroke with endovascular interventions. The rate of a favorable neurologic outcome as reflected in a modified Rankin score of 0-2 was 48% with the use of stent/retriever devices, compared with 30% with thrombolysis alone, said Dr. Petr Widimsky, professor and chair of the cardiology department at Charles University in Prague, at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EuroPCR) held in Paris in May.

The American Academy of Neurology “affirms the value of this guideline as an educational tool for neurologists.” The revised guideline is endorsed by the American Association of Neurological Surgeons, the Congress of Neurological Surgeons, the American Society of Neuroradiology, and the Society of Vascular and Interventional Neurology. A copy of the document is available at http://myamericanheart.org/statements.

FROM STROKE

Key clinical point: Pivotal new evidence prompted several changes in the 2013 AHA/ASA clinical practice guideline for early endovascular treatment of acute ischemic stroke.

Major finding: Most of the updates pertain to use of stent retrievers, which is now recommended for all patients with acute ischemic stroke who meet seven criteria.

Data source: A detailed review of eight randomized clinical trials and other relevant data published since 2013.

Disclosures: This work was supported by the American Heart Association and the American Stroke Association; Medtronic/Covidien, maker of the stent retriever newly recommended in this guideline, is a corporate sponsor of both the AHA and the ASA. Dr. Powers reported having no relevant financial disclosures; his associates on the writing committee reported ties to Microvention, Penumbra, Silk Road, Pulse Therapeutics, Covidien, Genentech, Stryker, Roche, Sequent, Lazarus, Codman, and Aldagn/Cytomedix.

Stent-retriever thrombectomy reduces poststroke disability

For patients with proximal large-vessel anterior stroke, neurovascular thrombectomy with a stent retriever plus medical therapy in the REVASCAT trial reduced the severity of poststroke disability and raised the rate of functional independence, compared with medical therapy alone, according to a report in the New England Journal of Medicine.

To assess the efficacy and safety of thrombectomy with a stent retriever, investigators performed a prospective, open-label, phase III clinical trial involving 206 adults up to 85 years of age treated at four designated comprehensive stroke centers in Catalonia, Spain.

All the participants in the Randomized Trial of Revascularization With Solitaire FR Device Versus Best Medical Therapy in the Treatment of Acute Stroke Due to Anterior Circulation Large Vessel Occlusion Presenting Within Eight Hours of Symptom Onset (REVASCAT) had either not responded to intravenous alteplase administered within 4.5 hours of symptom onset or had contraindications to alteplase therapy. They were randomly assigned in equal numbers to undergo endovascular treatment with a stent retriever or medical therapy alone, said Dr. Tudor G. Jovin, director of the Stroke Institute, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, and his associates.

The trial was halted early when the first interim analysis showed “lack of equipoise” between the two study groups, and because emerging results from three other studies demonstrated the superior efficacy of thrombectomy. The primary efficacy outcome measure – severity of disability at 90 days, as measured by expert assessors blinded to treatment assignment – significantly favored thrombectomy over medical therapy. The proportion of patients who achieved functional independence by day 90 on the modified Rankin scale also demonstrated the clear superiority of thrombectomy (43.7%) over medical therapy (28.2%).

Only 6.5 patients would need to be treated with thrombectomy to prevent 1 case of functional dependency or death. In addition, “thrombectomy was associated with a shift toward better outcomes across the entire spectrum of disability,” Dr. Jovin and his associates said (N. Engl. J. Med. 2015 [doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1503780]).

Regarding safety, the rate of death at 90 days did not differ significantly between patients who underwent thrombectomy (18.4%) and control subjects (15.5%). Rates of intracranial hemorrhage were the same, 1.9%, in both groups, and rates of other serious adverse events also were similar.

These findings are consistent with those of several other recently reported clinical trials and show that “in patients with acute stroke caused by a proximal large-vessel occlusion and an absence of a large infarct on baseline imaging, mechanical thrombectomy with [a] stent retriever was safe and led to improved clinical outcomes, as compared with medical therapy alone,” the investigators said.

REVASCAT was funded by an unrestricted grant from Covidien, maker of the stent retriever, and by grants from several Spanish research institutes. Dr. Jovin reported ties to Covidien, Silk Road Medical, Air Liquide, Medtronic, and Stryker Neurovascular.

For patients with proximal large-vessel anterior stroke, neurovascular thrombectomy with a stent retriever plus medical therapy in the REVASCAT trial reduced the severity of poststroke disability and raised the rate of functional independence, compared with medical therapy alone, according to a report in the New England Journal of Medicine.

To assess the efficacy and safety of thrombectomy with a stent retriever, investigators performed a prospective, open-label, phase III clinical trial involving 206 adults up to 85 years of age treated at four designated comprehensive stroke centers in Catalonia, Spain.

All the participants in the Randomized Trial of Revascularization With Solitaire FR Device Versus Best Medical Therapy in the Treatment of Acute Stroke Due to Anterior Circulation Large Vessel Occlusion Presenting Within Eight Hours of Symptom Onset (REVASCAT) had either not responded to intravenous alteplase administered within 4.5 hours of symptom onset or had contraindications to alteplase therapy. They were randomly assigned in equal numbers to undergo endovascular treatment with a stent retriever or medical therapy alone, said Dr. Tudor G. Jovin, director of the Stroke Institute, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, and his associates.

The trial was halted early when the first interim analysis showed “lack of equipoise” between the two study groups, and because emerging results from three other studies demonstrated the superior efficacy of thrombectomy. The primary efficacy outcome measure – severity of disability at 90 days, as measured by expert assessors blinded to treatment assignment – significantly favored thrombectomy over medical therapy. The proportion of patients who achieved functional independence by day 90 on the modified Rankin scale also demonstrated the clear superiority of thrombectomy (43.7%) over medical therapy (28.2%).

Only 6.5 patients would need to be treated with thrombectomy to prevent 1 case of functional dependency or death. In addition, “thrombectomy was associated with a shift toward better outcomes across the entire spectrum of disability,” Dr. Jovin and his associates said (N. Engl. J. Med. 2015 [doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1503780]).

Regarding safety, the rate of death at 90 days did not differ significantly between patients who underwent thrombectomy (18.4%) and control subjects (15.5%). Rates of intracranial hemorrhage were the same, 1.9%, in both groups, and rates of other serious adverse events also were similar.

These findings are consistent with those of several other recently reported clinical trials and show that “in patients with acute stroke caused by a proximal large-vessel occlusion and an absence of a large infarct on baseline imaging, mechanical thrombectomy with [a] stent retriever was safe and led to improved clinical outcomes, as compared with medical therapy alone,” the investigators said.

REVASCAT was funded by an unrestricted grant from Covidien, maker of the stent retriever, and by grants from several Spanish research institutes. Dr. Jovin reported ties to Covidien, Silk Road Medical, Air Liquide, Medtronic, and Stryker Neurovascular.

For patients with proximal large-vessel anterior stroke, neurovascular thrombectomy with a stent retriever plus medical therapy in the REVASCAT trial reduced the severity of poststroke disability and raised the rate of functional independence, compared with medical therapy alone, according to a report in the New England Journal of Medicine.

To assess the efficacy and safety of thrombectomy with a stent retriever, investigators performed a prospective, open-label, phase III clinical trial involving 206 adults up to 85 years of age treated at four designated comprehensive stroke centers in Catalonia, Spain.

All the participants in the Randomized Trial of Revascularization With Solitaire FR Device Versus Best Medical Therapy in the Treatment of Acute Stroke Due to Anterior Circulation Large Vessel Occlusion Presenting Within Eight Hours of Symptom Onset (REVASCAT) had either not responded to intravenous alteplase administered within 4.5 hours of symptom onset or had contraindications to alteplase therapy. They were randomly assigned in equal numbers to undergo endovascular treatment with a stent retriever or medical therapy alone, said Dr. Tudor G. Jovin, director of the Stroke Institute, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, and his associates.

The trial was halted early when the first interim analysis showed “lack of equipoise” between the two study groups, and because emerging results from three other studies demonstrated the superior efficacy of thrombectomy. The primary efficacy outcome measure – severity of disability at 90 days, as measured by expert assessors blinded to treatment assignment – significantly favored thrombectomy over medical therapy. The proportion of patients who achieved functional independence by day 90 on the modified Rankin scale also demonstrated the clear superiority of thrombectomy (43.7%) over medical therapy (28.2%).

Only 6.5 patients would need to be treated with thrombectomy to prevent 1 case of functional dependency or death. In addition, “thrombectomy was associated with a shift toward better outcomes across the entire spectrum of disability,” Dr. Jovin and his associates said (N. Engl. J. Med. 2015 [doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1503780]).

Regarding safety, the rate of death at 90 days did not differ significantly between patients who underwent thrombectomy (18.4%) and control subjects (15.5%). Rates of intracranial hemorrhage were the same, 1.9%, in both groups, and rates of other serious adverse events also were similar.

These findings are consistent with those of several other recently reported clinical trials and show that “in patients with acute stroke caused by a proximal large-vessel occlusion and an absence of a large infarct on baseline imaging, mechanical thrombectomy with [a] stent retriever was safe and led to improved clinical outcomes, as compared with medical therapy alone,” the investigators said.

REVASCAT was funded by an unrestricted grant from Covidien, maker of the stent retriever, and by grants from several Spanish research institutes. Dr. Jovin reported ties to Covidien, Silk Road Medical, Air Liquide, Medtronic, and Stryker Neurovascular.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Thrombectomy with a stent retriever reduced poststroke disability in patients with occlusion of the proximal anterior circulation.

Major finding: The proportion of patients who achieved functional independence by day 90 showed the clear superiority of thrombectomy (43.7%) over medical therapy (28.2%); only 6.5 patients would need to be treated with thrombectomy to prevent 1 case of functional dependency or death.

Data source: REVASCAT, a prospective, open-label, randomized phase III trial involving 206 adults treated during a 4-year period at four stroke centers in Spain.

Disclosures: REVASCAT was funded by an unrestricted grant from Covidien, maker of the stent retriever, and by grants from several Spanish research institutes. Dr. Jovin reported ties to Covidien, Silk Road Medical, Air Liquide, Medtronic, and Stryker Neurovascular.

Hyperglycemia may predict prognosis after ischemic stroke

VIENNA – Patients who have had an ischemic stroke and have high blood sugar levels without being diabetic may be more likely to experience functional impairments than those already diagnosed with diabetes, according to results from a large secondary stroke prevention trial performed in China.

In the trial, conducted at 47 hospitals, high levels of fasting blood glucose (FBG) were associated with worse disability at 6 months in the study, but the association only held in patients who did not have a diagnosis of diabetes at the time of their stroke. The odds ratios for poor functional outcome assessed using the modified Rankin scale (mRS) as a score of greater than 2 versus up to 2 were 1.09 (P = .031) in nondiabetics and 0.98 (P = 0.65) in those previously known to have diabetes.

“We think that a high FBG level after stroke might be better for predicting prognosis in patients without prediagnosed diabetes than in those with diabetes and confirms the importance of glycemic control during the acute phase of ischemic stroke,” said study researcher Dr. Ming Yao of Peking Union Medical College Hospital at the annual European Stroke Conference.Dr. Yao noted that hyperglycemia after an acute stroke had already been linked to poorer clinical outcomes, with reports of larger infarct volumes, an increased risk for secondary hemorrhagic transformation, and lower recanalization rates after thrombolysis. However, it was not clear how functional outcomes were affected or if there was much of difference based on whether or not a patient had diabetes. Data from the Standard Medical Management in Secondary Prevention of Ischemic Stroke in China (SMART) study were therefore used to see what effect high FBG had on functional outcomes in diabetic versus nondiabetic subjects. SMART was a multicenter, cluster-randomized, controlled trial designed to assess the effectiveness of a guideline-based structured care program versus usual care for the secondary prevention of ischemic stroke (Stroke. 2014;45:515-9) and offered a large population of patients for the subgroup analysis. Of the 3,821 patients enrolled in the study, 2,862 had FBG data available and had complete follow-up data at 6 months.

Potential factors related to functional outcome 6 months after a stroke were first identified in the whole cohort using a binary logistic regression model, which categorized outcome as favorable (mRS ≤2) or poor (mRS >2). Univariate and multivariate analyses were then performed to narrow down the variables that might be the most influential.

For the whole cohort, older age (OR = 1.04, P < .001), hypertension (OR = 1.45, P = .028), baseline National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score (OR = 1.28, P < .001), and FBG (OR = 1.07, P = .004) were indicative of a poor functional outcome.

Looking at patients with and without diabetes, older age remained predictive of a poorer functional outcome, with respective odds ratios of 1.04 (P = .011) and 1.04 (P < .001). Baseline NIHSS score was also predictive in both patients with diabetes (OR = 1.33, P < .001) and those without (OR = 1.27, P < .001).

“Our present results demonstrate that a higher FBG following stroke is strongly and independently associated with a poor functional outcome,” Dr. Yao observed, “but this association was found only in patients without prediagnosed diabetes.”

The study was study was sponsored by Peking Union Medical College Hospital. Dr. Yao had no conflicts of interest.

VIENNA – Patients who have had an ischemic stroke and have high blood sugar levels without being diabetic may be more likely to experience functional impairments than those already diagnosed with diabetes, according to results from a large secondary stroke prevention trial performed in China.

In the trial, conducted at 47 hospitals, high levels of fasting blood glucose (FBG) were associated with worse disability at 6 months in the study, but the association only held in patients who did not have a diagnosis of diabetes at the time of their stroke. The odds ratios for poor functional outcome assessed using the modified Rankin scale (mRS) as a score of greater than 2 versus up to 2 were 1.09 (P = .031) in nondiabetics and 0.98 (P = 0.65) in those previously known to have diabetes.

“We think that a high FBG level after stroke might be better for predicting prognosis in patients without prediagnosed diabetes than in those with diabetes and confirms the importance of glycemic control during the acute phase of ischemic stroke,” said study researcher Dr. Ming Yao of Peking Union Medical College Hospital at the annual European Stroke Conference.Dr. Yao noted that hyperglycemia after an acute stroke had already been linked to poorer clinical outcomes, with reports of larger infarct volumes, an increased risk for secondary hemorrhagic transformation, and lower recanalization rates after thrombolysis. However, it was not clear how functional outcomes were affected or if there was much of difference based on whether or not a patient had diabetes. Data from the Standard Medical Management in Secondary Prevention of Ischemic Stroke in China (SMART) study were therefore used to see what effect high FBG had on functional outcomes in diabetic versus nondiabetic subjects. SMART was a multicenter, cluster-randomized, controlled trial designed to assess the effectiveness of a guideline-based structured care program versus usual care for the secondary prevention of ischemic stroke (Stroke. 2014;45:515-9) and offered a large population of patients for the subgroup analysis. Of the 3,821 patients enrolled in the study, 2,862 had FBG data available and had complete follow-up data at 6 months.

Potential factors related to functional outcome 6 months after a stroke were first identified in the whole cohort using a binary logistic regression model, which categorized outcome as favorable (mRS ≤2) or poor (mRS >2). Univariate and multivariate analyses were then performed to narrow down the variables that might be the most influential.

For the whole cohort, older age (OR = 1.04, P < .001), hypertension (OR = 1.45, P = .028), baseline National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score (OR = 1.28, P < .001), and FBG (OR = 1.07, P = .004) were indicative of a poor functional outcome.

Looking at patients with and without diabetes, older age remained predictive of a poorer functional outcome, with respective odds ratios of 1.04 (P = .011) and 1.04 (P < .001). Baseline NIHSS score was also predictive in both patients with diabetes (OR = 1.33, P < .001) and those without (OR = 1.27, P < .001).

“Our present results demonstrate that a higher FBG following stroke is strongly and independently associated with a poor functional outcome,” Dr. Yao observed, “but this association was found only in patients without prediagnosed diabetes.”

The study was study was sponsored by Peking Union Medical College Hospital. Dr. Yao had no conflicts of interest.

VIENNA – Patients who have had an ischemic stroke and have high blood sugar levels without being diabetic may be more likely to experience functional impairments than those already diagnosed with diabetes, according to results from a large secondary stroke prevention trial performed in China.

In the trial, conducted at 47 hospitals, high levels of fasting blood glucose (FBG) were associated with worse disability at 6 months in the study, but the association only held in patients who did not have a diagnosis of diabetes at the time of their stroke. The odds ratios for poor functional outcome assessed using the modified Rankin scale (mRS) as a score of greater than 2 versus up to 2 were 1.09 (P = .031) in nondiabetics and 0.98 (P = 0.65) in those previously known to have diabetes.

“We think that a high FBG level after stroke might be better for predicting prognosis in patients without prediagnosed diabetes than in those with diabetes and confirms the importance of glycemic control during the acute phase of ischemic stroke,” said study researcher Dr. Ming Yao of Peking Union Medical College Hospital at the annual European Stroke Conference.Dr. Yao noted that hyperglycemia after an acute stroke had already been linked to poorer clinical outcomes, with reports of larger infarct volumes, an increased risk for secondary hemorrhagic transformation, and lower recanalization rates after thrombolysis. However, it was not clear how functional outcomes were affected or if there was much of difference based on whether or not a patient had diabetes. Data from the Standard Medical Management in Secondary Prevention of Ischemic Stroke in China (SMART) study were therefore used to see what effect high FBG had on functional outcomes in diabetic versus nondiabetic subjects. SMART was a multicenter, cluster-randomized, controlled trial designed to assess the effectiveness of a guideline-based structured care program versus usual care for the secondary prevention of ischemic stroke (Stroke. 2014;45:515-9) and offered a large population of patients for the subgroup analysis. Of the 3,821 patients enrolled in the study, 2,862 had FBG data available and had complete follow-up data at 6 months.

Potential factors related to functional outcome 6 months after a stroke were first identified in the whole cohort using a binary logistic regression model, which categorized outcome as favorable (mRS ≤2) or poor (mRS >2). Univariate and multivariate analyses were then performed to narrow down the variables that might be the most influential.

For the whole cohort, older age (OR = 1.04, P < .001), hypertension (OR = 1.45, P = .028), baseline National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score (OR = 1.28, P < .001), and FBG (OR = 1.07, P = .004) were indicative of a poor functional outcome.

Looking at patients with and without diabetes, older age remained predictive of a poorer functional outcome, with respective odds ratios of 1.04 (P = .011) and 1.04 (P < .001). Baseline NIHSS score was also predictive in both patients with diabetes (OR = 1.33, P < .001) and those without (OR = 1.27, P < .001).

“Our present results demonstrate that a higher FBG following stroke is strongly and independently associated with a poor functional outcome,” Dr. Yao observed, “but this association was found only in patients without prediagnosed diabetes.”

The study was study was sponsored by Peking Union Medical College Hospital. Dr. Yao had no conflicts of interest.

AT THE EUROPEAN STROKE CONFERENCE

Key clinical point: Glycemic control during acute stroke is important, particularly in nondiabetic patients.

Major finding: High fasting plasma glucose was associated with poor functional outcome at 6 months in nondiabetic patients (OR = 1.09, P = .031).

Data source: 2,862 patients from the SMART study, a multicenter, cluster-randomized, controlled, secondary stroke prevention trial conducted in China.

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by Peking Union Medical College Hospital. Dr. Yao had no disclosures.

Carotid artery stenosis guidelines need modernizing

VIENNA – Guidelines used around the world for the management of carotid stenosis, both in asymptomatic and symptomatic cases, are often outdated and do not match current evidence, according to the results of a systematic review undertaken by an international group of experts.*

Furthermore, the qualifying statements used to back up the recommendations are often confused and too simplistic, being based only on the degree of randomized data used.

“Other problems were that the guidelines often didn’t even define asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis or symptomatic carotid artery stenosis or they left out procedural standards,” said Dr. Anne Abbott, who presented the findings at the annual European Stroke Conference.

“A number of important discoveries have been made in recent years to better inform treatment decisions for patients with carotid stenosis,” Dr. Abbott, a neurologist at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia, observed.

For instance, based on evidence available today, it is clear that medical therapy alone is best for patients with moderate or severe (50%-99%) asymptomatic disease. Surgery in these patients might actually be harmful, she noted, and it is unknown if or by how much carotid endarterectomy improves stroke prevention versus medical therapy alone.

“We just haven’t done the studies, and this is where we should be concentrating our efforts with respect to randomized, placebo-controlled trials,” Dr. Abbott proposed. “But we do know that the 6% 30-day stroke/death rate [with endarterectomy] is really now too high.”

It’s also now apparent that carotid angioplasty or stenting is more harmful than carotid endarterectomy in asymptomatic patients and “shouldn’t be recommended for routine practice.” Many of the guidelines were still supporting this as an option, she observed, based on the supposed counterbalancing argument that surgical intervention was more likely to increase the risk for heart attacks than stenting. However, the evidence shows that the greatest risk to patients in the periprocedural period is the stroke risk, which is increased by stenting.

Dr. Abbott explained how the team of 16 experts had reviewed all the latest available guidelines for asymptomatic and symptomatic carotid stenosis that they could find from published from January 2008 until January 2015. She noted that guidelines were often difficult to access were often only found because the team knew of their existence through their professional networks.

A total of 34 guidelines from 23 regions or countries in six languages were identified and included in the review. Each of these was independently assessed by two to six of the team, looking at the clinical scenarios covered, the nature of the recommendations made and what evidence was being used to support the recommendations.

Of 28 guidelines that gave recommendations for asymptomatic carotid stenosis, surgery was endorsed for patients at average surgical risk and only one (4%) endorsed medical treatment alone. Eighteen (64%) recommended that stenting be performed or considered, and 24 (86%) supported the use of endarterectomy. “This is despite current evidence that these procedures are now more likely to harm than help patients,” Dr. Abbott said.

“Of major concern I think is that a high proportion, about half, of these guidelines are recommending stenting for high surgical risk asymptomatic patients, she cautioned. “This includes patients with major medical comorbidities – heart failure, respiratory failure – who have a very short life expectancy and are least likely to benefit and are more likely to be at risk from the procedures.”

Somewhat similar findings were seen regarding the use of stenting and surgery in the 33 guidelines that gave recommendations for the management of symptomatic carotid stenosis. Endarterectomy was recommended for average-surgical-risk symptomatic patients by 31 (94%) guidelines and, worryingly, stenting was still being advocated in 19 (58%) guidelines with only nine (27%) saying that stenting should not be used. Stenting was also being endorsed in symptomatic patients at high surgical risk.

Dr. Abbott said that the guidelines were hard to compare because they used a variety of qualifying statements to try to advise on the degree to which a procedure was recommended. There was no consistency or standardization: six guidelines did not use any qualifying statements or were not defined in two guidelines, 10 guidelines used class or grade to denote the strength of the recommendation being made, and 27 guidelines used class, grade, or other means to denote the strength of the evidence the recommendations were being based on.

All this means, however, that there are many opportunities to modernize the guidelines and bring them up-to-date with current knowledge. They shouldn’t be recommending stenting over surgery, for example, and they need to standardize what the recommendations are based on.

“The guidelines should always define their target population properly and that comes straight from randomized trials usually,” Dr. Abbott noted. Procedural standards also need to be given. “Guidelines also need to be consistent throughout, self-contained, and be more accessible.”

Dr. Abbott had no relevant disclosures.

*CORRECTION: 6/21/2015 An error in identification of the stent was corrected.

VIENNA – Guidelines used around the world for the management of carotid stenosis, both in asymptomatic and symptomatic cases, are often outdated and do not match current evidence, according to the results of a systematic review undertaken by an international group of experts.*

Furthermore, the qualifying statements used to back up the recommendations are often confused and too simplistic, being based only on the degree of randomized data used.

“Other problems were that the guidelines often didn’t even define asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis or symptomatic carotid artery stenosis or they left out procedural standards,” said Dr. Anne Abbott, who presented the findings at the annual European Stroke Conference.

“A number of important discoveries have been made in recent years to better inform treatment decisions for patients with carotid stenosis,” Dr. Abbott, a neurologist at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia, observed.

For instance, based on evidence available today, it is clear that medical therapy alone is best for patients with moderate or severe (50%-99%) asymptomatic disease. Surgery in these patients might actually be harmful, she noted, and it is unknown if or by how much carotid endarterectomy improves stroke prevention versus medical therapy alone.

“We just haven’t done the studies, and this is where we should be concentrating our efforts with respect to randomized, placebo-controlled trials,” Dr. Abbott proposed. “But we do know that the 6% 30-day stroke/death rate [with endarterectomy] is really now too high.”

It’s also now apparent that carotid angioplasty or stenting is more harmful than carotid endarterectomy in asymptomatic patients and “shouldn’t be recommended for routine practice.” Many of the guidelines were still supporting this as an option, she observed, based on the supposed counterbalancing argument that surgical intervention was more likely to increase the risk for heart attacks than stenting. However, the evidence shows that the greatest risk to patients in the periprocedural period is the stroke risk, which is increased by stenting.

Dr. Abbott explained how the team of 16 experts had reviewed all the latest available guidelines for asymptomatic and symptomatic carotid stenosis that they could find from published from January 2008 until January 2015. She noted that guidelines were often difficult to access were often only found because the team knew of their existence through their professional networks.

A total of 34 guidelines from 23 regions or countries in six languages were identified and included in the review. Each of these was independently assessed by two to six of the team, looking at the clinical scenarios covered, the nature of the recommendations made and what evidence was being used to support the recommendations.

Of 28 guidelines that gave recommendations for asymptomatic carotid stenosis, surgery was endorsed for patients at average surgical risk and only one (4%) endorsed medical treatment alone. Eighteen (64%) recommended that stenting be performed or considered, and 24 (86%) supported the use of endarterectomy. “This is despite current evidence that these procedures are now more likely to harm than help patients,” Dr. Abbott said.

“Of major concern I think is that a high proportion, about half, of these guidelines are recommending stenting for high surgical risk asymptomatic patients, she cautioned. “This includes patients with major medical comorbidities – heart failure, respiratory failure – who have a very short life expectancy and are least likely to benefit and are more likely to be at risk from the procedures.”

Somewhat similar findings were seen regarding the use of stenting and surgery in the 33 guidelines that gave recommendations for the management of symptomatic carotid stenosis. Endarterectomy was recommended for average-surgical-risk symptomatic patients by 31 (94%) guidelines and, worryingly, stenting was still being advocated in 19 (58%) guidelines with only nine (27%) saying that stenting should not be used. Stenting was also being endorsed in symptomatic patients at high surgical risk.

Dr. Abbott said that the guidelines were hard to compare because they used a variety of qualifying statements to try to advise on the degree to which a procedure was recommended. There was no consistency or standardization: six guidelines did not use any qualifying statements or were not defined in two guidelines, 10 guidelines used class or grade to denote the strength of the recommendation being made, and 27 guidelines used class, grade, or other means to denote the strength of the evidence the recommendations were being based on.

All this means, however, that there are many opportunities to modernize the guidelines and bring them up-to-date with current knowledge. They shouldn’t be recommending stenting over surgery, for example, and they need to standardize what the recommendations are based on.

“The guidelines should always define their target population properly and that comes straight from randomized trials usually,” Dr. Abbott noted. Procedural standards also need to be given. “Guidelines also need to be consistent throughout, self-contained, and be more accessible.”

Dr. Abbott had no relevant disclosures.

*CORRECTION: 6/21/2015 An error in identification of the stent was corrected.

VIENNA – Guidelines used around the world for the management of carotid stenosis, both in asymptomatic and symptomatic cases, are often outdated and do not match current evidence, according to the results of a systematic review undertaken by an international group of experts.*

Furthermore, the qualifying statements used to back up the recommendations are often confused and too simplistic, being based only on the degree of randomized data used.

“Other problems were that the guidelines often didn’t even define asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis or symptomatic carotid artery stenosis or they left out procedural standards,” said Dr. Anne Abbott, who presented the findings at the annual European Stroke Conference.

“A number of important discoveries have been made in recent years to better inform treatment decisions for patients with carotid stenosis,” Dr. Abbott, a neurologist at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia, observed.

For instance, based on evidence available today, it is clear that medical therapy alone is best for patients with moderate or severe (50%-99%) asymptomatic disease. Surgery in these patients might actually be harmful, she noted, and it is unknown if or by how much carotid endarterectomy improves stroke prevention versus medical therapy alone.

“We just haven’t done the studies, and this is where we should be concentrating our efforts with respect to randomized, placebo-controlled trials,” Dr. Abbott proposed. “But we do know that the 6% 30-day stroke/death rate [with endarterectomy] is really now too high.”

It’s also now apparent that carotid angioplasty or stenting is more harmful than carotid endarterectomy in asymptomatic patients and “shouldn’t be recommended for routine practice.” Many of the guidelines were still supporting this as an option, she observed, based on the supposed counterbalancing argument that surgical intervention was more likely to increase the risk for heart attacks than stenting. However, the evidence shows that the greatest risk to patients in the periprocedural period is the stroke risk, which is increased by stenting.

Dr. Abbott explained how the team of 16 experts had reviewed all the latest available guidelines for asymptomatic and symptomatic carotid stenosis that they could find from published from January 2008 until January 2015. She noted that guidelines were often difficult to access were often only found because the team knew of their existence through their professional networks.

A total of 34 guidelines from 23 regions or countries in six languages were identified and included in the review. Each of these was independently assessed by two to six of the team, looking at the clinical scenarios covered, the nature of the recommendations made and what evidence was being used to support the recommendations.

Of 28 guidelines that gave recommendations for asymptomatic carotid stenosis, surgery was endorsed for patients at average surgical risk and only one (4%) endorsed medical treatment alone. Eighteen (64%) recommended that stenting be performed or considered, and 24 (86%) supported the use of endarterectomy. “This is despite current evidence that these procedures are now more likely to harm than help patients,” Dr. Abbott said.

“Of major concern I think is that a high proportion, about half, of these guidelines are recommending stenting for high surgical risk asymptomatic patients, she cautioned. “This includes patients with major medical comorbidities – heart failure, respiratory failure – who have a very short life expectancy and are least likely to benefit and are more likely to be at risk from the procedures.”

Somewhat similar findings were seen regarding the use of stenting and surgery in the 33 guidelines that gave recommendations for the management of symptomatic carotid stenosis. Endarterectomy was recommended for average-surgical-risk symptomatic patients by 31 (94%) guidelines and, worryingly, stenting was still being advocated in 19 (58%) guidelines with only nine (27%) saying that stenting should not be used. Stenting was also being endorsed in symptomatic patients at high surgical risk.

Dr. Abbott said that the guidelines were hard to compare because they used a variety of qualifying statements to try to advise on the degree to which a procedure was recommended. There was no consistency or standardization: six guidelines did not use any qualifying statements or were not defined in two guidelines, 10 guidelines used class or grade to denote the strength of the recommendation being made, and 27 guidelines used class, grade, or other means to denote the strength of the evidence the recommendations were being based on.

All this means, however, that there are many opportunities to modernize the guidelines and bring them up-to-date with current knowledge. They shouldn’t be recommending stenting over surgery, for example, and they need to standardize what the recommendations are based on.

“The guidelines should always define their target population properly and that comes straight from randomized trials usually,” Dr. Abbott noted. Procedural standards also need to be given. “Guidelines also need to be consistent throughout, self-contained, and be more accessible.”

Dr. Abbott had no relevant disclosures.

*CORRECTION: 6/21/2015 An error in identification of the stent was corrected.

AT THE EUROPEAN STROKE CONFERENCE

Key clinical point: Guidelines for carotid stenosis need reviewing and updating in line with modern evidence and practice.

Major finding: Carotid angiography/stenting was recommended for both asymptomatic and symptomatic patients despite current evidence showing that it is more likely to cause harm than provide benefit.

Data source: Systematic review of 33 guidelines for asymptomatic and symptomatic carotid stenosis.

Disclosures: Dr. Abbott had no relevant disclosures.

Statins, fibrates lower stroke risk in elderly

Both statin and fibrate therapies taken to improve lipid profiles decreased the risk of stroke by 30% in a community-dwelling population of elderly people, according to prospective European study published online May 19 in the British Medical Journal.

Participants in almost all the randomized clinical trials assessing cardiovascular drugs are younger than age 70, so the benefits of these agents in older patients – particularly their effectiveness as primary prevention in people who have no known cardiovascular illness – is uncertain. Nevertheless, “in real life, statins are commonly prescribed to older people without clinical evidence of atherosclerosis,” said Dr. Annick Alperovitch of the University of Bordeaux (France) and her associates.

To assess the effects of statin and fibrate therapies on incident cardiovascular events in an elderly population, the investigators analyzed data from an ongoing cohort study of vascular disease among elderly residents of Bordeaux, Dijon, and Montpellier. Dr. Alperovitch and her associates examined the medical records of a subset of 7,484 men and women (mean age 74 years) who were followed every 2 years for a mean of 9 years. A total of 27% reported using lipid-lowering medications at baseline; roughly half used statins and half used fibrates. There were 292 strokes during follow-up.

The risk of stroke was cut by roughly 30% among statin and fibrate users, compared with nonusers (hazard ratio, 0.66). This decrease was similar between the two medications. All-cause mortality was slightly lower in people who took statins or fibrates, compared with nonusers (HR 0.87), the investigators said (Br. Med. J. 2015 May 19 [doi:10.1136/bmj.h2335]).

This is the first observational study to show a significant association between lipid-lowering drugs and decreased stroke risk, they noted.

The overall incidence of stroke in this study was low (0.47 per 100 person-years), so even a 30% decrease produced “a limited number of avoided cases.” That may be attributable in part to the generally healthy lifestyle, high educational achievement, and high economic status of this urban French study population. But if the findings are confirmed in future studies, they could have an important impact on public health in other populations, Dr. Alperovitch and her associates said.

The findings of a single observational study will not change guidelines regarding cholesterol therapy, but they are sufficiently compelling to warrant further research on primary prevention of stroke in elderly people.

This is the first observational study to describe a significant association between lipid-lowering medications and decreased stroke risk. Previous studies have shown only a weak association in early middle age, and no association in the elderly.

Graeme J. Hankey, M.D., is professor of neurology at the University of Western Australia’s Harry Perkins Institute of Medical Research, Perth, and honorary senior research fellow at Western Australian Neuroscience Research Institute, also in Perth. He reported ties to Sanofi Aventis, Bayer Pharmaceuticals, and Medscape. Dr. Hankey made these remarks in an editorial accompanying Dr. Alperovitch’s report (Br. Med. J. 2015 May 19 [doi:10.1136/bmj.h2568]).

The findings of a single observational study will not change guidelines regarding cholesterol therapy, but they are sufficiently compelling to warrant further research on primary prevention of stroke in elderly people.

This is the first observational study to describe a significant association between lipid-lowering medications and decreased stroke risk. Previous studies have shown only a weak association in early middle age, and no association in the elderly.

Graeme J. Hankey, M.D., is professor of neurology at the University of Western Australia’s Harry Perkins Institute of Medical Research, Perth, and honorary senior research fellow at Western Australian Neuroscience Research Institute, also in Perth. He reported ties to Sanofi Aventis, Bayer Pharmaceuticals, and Medscape. Dr. Hankey made these remarks in an editorial accompanying Dr. Alperovitch’s report (Br. Med. J. 2015 May 19 [doi:10.1136/bmj.h2568]).

The findings of a single observational study will not change guidelines regarding cholesterol therapy, but they are sufficiently compelling to warrant further research on primary prevention of stroke in elderly people.

This is the first observational study to describe a significant association between lipid-lowering medications and decreased stroke risk. Previous studies have shown only a weak association in early middle age, and no association in the elderly.

Graeme J. Hankey, M.D., is professor of neurology at the University of Western Australia’s Harry Perkins Institute of Medical Research, Perth, and honorary senior research fellow at Western Australian Neuroscience Research Institute, also in Perth. He reported ties to Sanofi Aventis, Bayer Pharmaceuticals, and Medscape. Dr. Hankey made these remarks in an editorial accompanying Dr. Alperovitch’s report (Br. Med. J. 2015 May 19 [doi:10.1136/bmj.h2568]).

Both statin and fibrate therapies taken to improve lipid profiles decreased the risk of stroke by 30% in a community-dwelling population of elderly people, according to prospective European study published online May 19 in the British Medical Journal.

Participants in almost all the randomized clinical trials assessing cardiovascular drugs are younger than age 70, so the benefits of these agents in older patients – particularly their effectiveness as primary prevention in people who have no known cardiovascular illness – is uncertain. Nevertheless, “in real life, statins are commonly prescribed to older people without clinical evidence of atherosclerosis,” said Dr. Annick Alperovitch of the University of Bordeaux (France) and her associates.

To assess the effects of statin and fibrate therapies on incident cardiovascular events in an elderly population, the investigators analyzed data from an ongoing cohort study of vascular disease among elderly residents of Bordeaux, Dijon, and Montpellier. Dr. Alperovitch and her associates examined the medical records of a subset of 7,484 men and women (mean age 74 years) who were followed every 2 years for a mean of 9 years. A total of 27% reported using lipid-lowering medications at baseline; roughly half used statins and half used fibrates. There were 292 strokes during follow-up.

The risk of stroke was cut by roughly 30% among statin and fibrate users, compared with nonusers (hazard ratio, 0.66). This decrease was similar between the two medications. All-cause mortality was slightly lower in people who took statins or fibrates, compared with nonusers (HR 0.87), the investigators said (Br. Med. J. 2015 May 19 [doi:10.1136/bmj.h2335]).

This is the first observational study to show a significant association between lipid-lowering drugs and decreased stroke risk, they noted.

The overall incidence of stroke in this study was low (0.47 per 100 person-years), so even a 30% decrease produced “a limited number of avoided cases.” That may be attributable in part to the generally healthy lifestyle, high educational achievement, and high economic status of this urban French study population. But if the findings are confirmed in future studies, they could have an important impact on public health in other populations, Dr. Alperovitch and her associates said.

Both statin and fibrate therapies taken to improve lipid profiles decreased the risk of stroke by 30% in a community-dwelling population of elderly people, according to prospective European study published online May 19 in the British Medical Journal.

Participants in almost all the randomized clinical trials assessing cardiovascular drugs are younger than age 70, so the benefits of these agents in older patients – particularly their effectiveness as primary prevention in people who have no known cardiovascular illness – is uncertain. Nevertheless, “in real life, statins are commonly prescribed to older people without clinical evidence of atherosclerosis,” said Dr. Annick Alperovitch of the University of Bordeaux (France) and her associates.

To assess the effects of statin and fibrate therapies on incident cardiovascular events in an elderly population, the investigators analyzed data from an ongoing cohort study of vascular disease among elderly residents of Bordeaux, Dijon, and Montpellier. Dr. Alperovitch and her associates examined the medical records of a subset of 7,484 men and women (mean age 74 years) who were followed every 2 years for a mean of 9 years. A total of 27% reported using lipid-lowering medications at baseline; roughly half used statins and half used fibrates. There were 292 strokes during follow-up.

The risk of stroke was cut by roughly 30% among statin and fibrate users, compared with nonusers (hazard ratio, 0.66). This decrease was similar between the two medications. All-cause mortality was slightly lower in people who took statins or fibrates, compared with nonusers (HR 0.87), the investigators said (Br. Med. J. 2015 May 19 [doi:10.1136/bmj.h2335]).

This is the first observational study to show a significant association between lipid-lowering drugs and decreased stroke risk, they noted.

The overall incidence of stroke in this study was low (0.47 per 100 person-years), so even a 30% decrease produced “a limited number of avoided cases.” That may be attributable in part to the generally healthy lifestyle, high educational achievement, and high economic status of this urban French study population. But if the findings are confirmed in future studies, they could have an important impact on public health in other populations, Dr. Alperovitch and her associates said.

Key clinical point: Statin and fibrate therapies significantly decreased stroke risk in a large cohort of elderly people.

Major finding: The risk of stroke was cut by 30% among statin and fibrate users, compared with nonusers (HR, 0.66).

Data source: A prospective, population-based cohort study of 7,484 elderly community-dwelling people followed for 9 years.

Disclosures: This study was supported by Institut National de la Sante et de la Recherche Medicale, Victor Segalen-Bordeaux II University, and Sanofi-Aventis. Dr. Alperovitch reported receiving honoraria from the French National Medicines Agency, the Fondation Plan Alzheimer, and Fondation Bettencourt-Schueller.

Asymptomatic carotid stenosis and central sleep apnea linked

More than two-thirds of patients with asymptomatic carotid stenosis are likely have sleep apnea, according to an observational study.

The polysomnography results of 96 patients with asymptomatic extracranial carotid stenosis revealed that 69% had sleep apnea. Obstructive sleep apnea was present in 42% of patients and central sleep apnea in 27%.

Stenosis severity was significantly associated with central sleep apnea, but not with obstructive sleep apnea. Researchers found that central sleep apnea, but not obstructive sleep apnea, was associated with arterial hypertension and diabetes mellitus in those patients with asymptomatic carotid stenosis (CHEST 2015;147:1029-1036 [doi:10.1378/chest.14-1655]).

The patients ranged in age from 39 to 86 years (mean age, 70 years); 64 were men. Of the 96 patients, 21 had mild/moderate stenosis and 75 had severe carotid stenosis. Patients with severe stenosis were older, average age 67 years, than were those with mild/moderate stenosis, average age 61 years. The frequency of arterial hypertension and diabetes mellitus was higher in the severe stenosis group than in the mild/moderate stenosis group.

The prevalence of sleep apnea was 76% in patients with severe stenosis compared with 29% in those with mild/moderate carotid stenosis. Total apnea-hypopnea index was higher in the severe stenosis group compared with the mild/moderate stenosis group (P less than or equal to .009). Increase in sleep apnea severity was based on an increase in central apnea-hypopnea index (P less than or equal to .001) but not in obstructive apnea-hypopnea index, reflecting an augmentation of central sleep apnea and not of obstructive sleep apnea in patients with severe compared with mild/moderate carotid stenosis.

“This vascular risk constellation seems to be more strongly connected with CSA [central sleep apnea] than with OSA [obstructive sleep apnea], possibly attributable to carotid chemoreceptor dysfunction,” wrote Dr. Jens Ehrhardt and colleagues at Jena University Hospital, Germany.

No conflicts of interest were declared.

More than two-thirds of patients with asymptomatic carotid stenosis are likely have sleep apnea, according to an observational study.

The polysomnography results of 96 patients with asymptomatic extracranial carotid stenosis revealed that 69% had sleep apnea. Obstructive sleep apnea was present in 42% of patients and central sleep apnea in 27%.

Stenosis severity was significantly associated with central sleep apnea, but not with obstructive sleep apnea. Researchers found that central sleep apnea, but not obstructive sleep apnea, was associated with arterial hypertension and diabetes mellitus in those patients with asymptomatic carotid stenosis (CHEST 2015;147:1029-1036 [doi:10.1378/chest.14-1655]).

The patients ranged in age from 39 to 86 years (mean age, 70 years); 64 were men. Of the 96 patients, 21 had mild/moderate stenosis and 75 had severe carotid stenosis. Patients with severe stenosis were older, average age 67 years, than were those with mild/moderate stenosis, average age 61 years. The frequency of arterial hypertension and diabetes mellitus was higher in the severe stenosis group than in the mild/moderate stenosis group.

The prevalence of sleep apnea was 76% in patients with severe stenosis compared with 29% in those with mild/moderate carotid stenosis. Total apnea-hypopnea index was higher in the severe stenosis group compared with the mild/moderate stenosis group (P less than or equal to .009). Increase in sleep apnea severity was based on an increase in central apnea-hypopnea index (P less than or equal to .001) but not in obstructive apnea-hypopnea index, reflecting an augmentation of central sleep apnea and not of obstructive sleep apnea in patients with severe compared with mild/moderate carotid stenosis.

“This vascular risk constellation seems to be more strongly connected with CSA [central sleep apnea] than with OSA [obstructive sleep apnea], possibly attributable to carotid chemoreceptor dysfunction,” wrote Dr. Jens Ehrhardt and colleagues at Jena University Hospital, Germany.

No conflicts of interest were declared.

More than two-thirds of patients with asymptomatic carotid stenosis are likely have sleep apnea, according to an observational study.

The polysomnography results of 96 patients with asymptomatic extracranial carotid stenosis revealed that 69% had sleep apnea. Obstructive sleep apnea was present in 42% of patients and central sleep apnea in 27%.

Stenosis severity was significantly associated with central sleep apnea, but not with obstructive sleep apnea. Researchers found that central sleep apnea, but not obstructive sleep apnea, was associated with arterial hypertension and diabetes mellitus in those patients with asymptomatic carotid stenosis (CHEST 2015;147:1029-1036 [doi:10.1378/chest.14-1655]).

The patients ranged in age from 39 to 86 years (mean age, 70 years); 64 were men. Of the 96 patients, 21 had mild/moderate stenosis and 75 had severe carotid stenosis. Patients with severe stenosis were older, average age 67 years, than were those with mild/moderate stenosis, average age 61 years. The frequency of arterial hypertension and diabetes mellitus was higher in the severe stenosis group than in the mild/moderate stenosis group.

The prevalence of sleep apnea was 76% in patients with severe stenosis compared with 29% in those with mild/moderate carotid stenosis. Total apnea-hypopnea index was higher in the severe stenosis group compared with the mild/moderate stenosis group (P less than or equal to .009). Increase in sleep apnea severity was based on an increase in central apnea-hypopnea index (P less than or equal to .001) but not in obstructive apnea-hypopnea index, reflecting an augmentation of central sleep apnea and not of obstructive sleep apnea in patients with severe compared with mild/moderate carotid stenosis.