User login

Reduced TPA Regimen Safely Treats Pulmonary Embolism

CHICAGO – A reduced-dose regimen of tissue plasminogen activator and parenteral anticoagulant safely led to improved outcomes in hemodynamically stable patients with a pulmonary embolism in a pilot study with a total of 121 patients treated at one U.S. center.

None of the 61 patients treated with the regimen, which halved the standard dosage of tissue plasminogen activator (TPA) and cut the dosage of enoxaparin or heparin by about 20%-30%, had an intracranial hemorrhage or a major bleeding event, compared with a historic 2%-6% incidence of intracranial hemorrhage and a 6%-20% incidence of major bleeds in hemodynamically unstable pulmonary embolism patients who receive the standard, full dose of both the thrombolytic and anticoagulant, Dr. Mohsen Sharifi said at the meeting.

While he acknowledged that the results need confirmation in a larger study, "in our experience treating deep vein thrombosis [with a similarly low dosage of TPA], we are comfortable that this amount of TPA can be given safely," said Dr. Sharifi, an interventional cardiologist who practices in Mesa, Ariz.

The findings also showed that applying this reduced-dose intervention to hemodynamically stable patients with a pulmonary embolism (PE), who are typically not treated, substantially improved their long-term prognosis by reducing their development of pulmonary hypertension. After an average of 28 months follow-up, 9 of the 58 patients (16%) followed long term and treated with the reduced-dose regimen had pulmonary hypertension, defined as a pulmonary artery systolic pressure greater than 40 mm Hg, compared with pulmonary hypertension in 32 of the 56 control patients (57%) managed by standard treatment with anticoagulation only.

Current guidelines from the American Heart Association call for fibrinolytic treatment only in patients with a massive, acute PE, or in patients with a submassive PE who are hemodynamically unstable or have other clinical evidence of an adverse prognosis (Circulation 2011;123:1788-830). According to Dr. Sharifi, about 5% of all PE patients fall into this category. He estimated that broadening thrombolytic treatment to hemodynamically stable patients who met his study’s inclusion criteria could broaden TPA treatment to an additional 70% of PE patients currently seen in emergency departments.

"I think that, based on the results of this pilot study, you won’t get broad acceptance of treating hemodynamically stable PE patients with thrombolysis," commented Dr. Michael Crawford, chief of general cardiology at the University of California, San Francisco. Two larger studies nearing completion are both examining the efficacy and safety of thrombolysis in patients with submassive PE.

Dr. Sharifi said that despite the small study size, he and his associates were convinced enough by their findings to use the reduced TPA dosage tested in this study on a routine basis when they see patients who meet their enrollment criteria.

The MOPETT (Moderate Pulmonary Embolism Treated with Thrombolysis) study enrolled patients with a PE affecting at least two lobar segments, pulmonary artery systolic pressure greater than 40 mm Hg; right ventricular hypokinesia and enlargement; and at least two symptoms, which could include chest pain, tachypnea greater than 22 respirations/min, tachycardia with a resting heart rate of more than 90 beats/min, dyspnea, cough, oxygen desaturation, and jugular venous pressure more than 12 mm H2O. The average age of the patients was about 59 years, and slightly more than half were women. Their average pulmonary artery systolic pressure at entry was about 50 mm Hg.

Dr. Sharifi and his associates randomized half the patients to receive conventional treatment with anticoagulant only, either enoxaparin or heparin plus warfarin. The other patients received thrombolytic treatment with an infusion of TPA at half the standard dosage, starting in patients who weighed at least 50 kg with a loading dose of 10 mg delivered in 1 minute, and followed by a 40-mg total additional dose administered over 2 hours. Patients who weighed less received the same 10-mg initial dose, but their total dose including the subsequent 2-hour infusion was limited to 0.5 mg/kg. The patients treated with TPA also received concomitant anticoagulation, with either enoxaparin given at 1 mg/kg but not to exceed 80 mg as an initial dose, or heparin at an initial dose of 70 U/kg but capped at 6,000 U, followed by heparin maintenance at 10 U/kg per hour during the TPA infusion (but not exceeding 1,000 U/hour), and then rising to 18 U/kg per hour starting 1 hour after TPA treatment stopped. About 80% of all patients in the study received enoxaparin, and about 20% received heparin.

At 48 hours after starting treatment, average pulmonary artery systolic pressure dropped by 16 mm Hg in the TPA group and by 5 mm Hg in the control patients. By the end of the average 28-month follow-up, average pulmonary artery systolic pressure was 28 mm Hg in the TPA patients and 43 mm Hg in the controls. Dr. Sharifi attributed the efficacy of reduced-dose TPA to the "exquisite sensitivity" of blood clots lodged in a patient’s lungs to the drug, a consequence of all the infused TPA passing through the lung’s arterial circulation.

In addition to showing a statistically significant benefit from TPA for the study’s primary end point, the average duration of hospitalization in the TPA recipients was 2.2 days, compared with an average of 4.9 days in the control patients, a statistically significant difference. And at the end of the average 28 months of follow-up, three patients in the control arm had a recurrent PE and another three had died, significantly more than the no recurrent PEs and one death in the TPA arm.

Dr. Sharifi and Dr. Crawford said that they had no relevant disclosures.

CHICAGO – A reduced-dose regimen of tissue plasminogen activator and parenteral anticoagulant safely led to improved outcomes in hemodynamically stable patients with a pulmonary embolism in a pilot study with a total of 121 patients treated at one U.S. center.

None of the 61 patients treated with the regimen, which halved the standard dosage of tissue plasminogen activator (TPA) and cut the dosage of enoxaparin or heparin by about 20%-30%, had an intracranial hemorrhage or a major bleeding event, compared with a historic 2%-6% incidence of intracranial hemorrhage and a 6%-20% incidence of major bleeds in hemodynamically unstable pulmonary embolism patients who receive the standard, full dose of both the thrombolytic and anticoagulant, Dr. Mohsen Sharifi said at the meeting.

While he acknowledged that the results need confirmation in a larger study, "in our experience treating deep vein thrombosis [with a similarly low dosage of TPA], we are comfortable that this amount of TPA can be given safely," said Dr. Sharifi, an interventional cardiologist who practices in Mesa, Ariz.

The findings also showed that applying this reduced-dose intervention to hemodynamically stable patients with a pulmonary embolism (PE), who are typically not treated, substantially improved their long-term prognosis by reducing their development of pulmonary hypertension. After an average of 28 months follow-up, 9 of the 58 patients (16%) followed long term and treated with the reduced-dose regimen had pulmonary hypertension, defined as a pulmonary artery systolic pressure greater than 40 mm Hg, compared with pulmonary hypertension in 32 of the 56 control patients (57%) managed by standard treatment with anticoagulation only.

Current guidelines from the American Heart Association call for fibrinolytic treatment only in patients with a massive, acute PE, or in patients with a submassive PE who are hemodynamically unstable or have other clinical evidence of an adverse prognosis (Circulation 2011;123:1788-830). According to Dr. Sharifi, about 5% of all PE patients fall into this category. He estimated that broadening thrombolytic treatment to hemodynamically stable patients who met his study’s inclusion criteria could broaden TPA treatment to an additional 70% of PE patients currently seen in emergency departments.

"I think that, based on the results of this pilot study, you won’t get broad acceptance of treating hemodynamically stable PE patients with thrombolysis," commented Dr. Michael Crawford, chief of general cardiology at the University of California, San Francisco. Two larger studies nearing completion are both examining the efficacy and safety of thrombolysis in patients with submassive PE.

Dr. Sharifi said that despite the small study size, he and his associates were convinced enough by their findings to use the reduced TPA dosage tested in this study on a routine basis when they see patients who meet their enrollment criteria.

The MOPETT (Moderate Pulmonary Embolism Treated with Thrombolysis) study enrolled patients with a PE affecting at least two lobar segments, pulmonary artery systolic pressure greater than 40 mm Hg; right ventricular hypokinesia and enlargement; and at least two symptoms, which could include chest pain, tachypnea greater than 22 respirations/min, tachycardia with a resting heart rate of more than 90 beats/min, dyspnea, cough, oxygen desaturation, and jugular venous pressure more than 12 mm H2O. The average age of the patients was about 59 years, and slightly more than half were women. Their average pulmonary artery systolic pressure at entry was about 50 mm Hg.

Dr. Sharifi and his associates randomized half the patients to receive conventional treatment with anticoagulant only, either enoxaparin or heparin plus warfarin. The other patients received thrombolytic treatment with an infusion of TPA at half the standard dosage, starting in patients who weighed at least 50 kg with a loading dose of 10 mg delivered in 1 minute, and followed by a 40-mg total additional dose administered over 2 hours. Patients who weighed less received the same 10-mg initial dose, but their total dose including the subsequent 2-hour infusion was limited to 0.5 mg/kg. The patients treated with TPA also received concomitant anticoagulation, with either enoxaparin given at 1 mg/kg but not to exceed 80 mg as an initial dose, or heparin at an initial dose of 70 U/kg but capped at 6,000 U, followed by heparin maintenance at 10 U/kg per hour during the TPA infusion (but not exceeding 1,000 U/hour), and then rising to 18 U/kg per hour starting 1 hour after TPA treatment stopped. About 80% of all patients in the study received enoxaparin, and about 20% received heparin.

At 48 hours after starting treatment, average pulmonary artery systolic pressure dropped by 16 mm Hg in the TPA group and by 5 mm Hg in the control patients. By the end of the average 28-month follow-up, average pulmonary artery systolic pressure was 28 mm Hg in the TPA patients and 43 mm Hg in the controls. Dr. Sharifi attributed the efficacy of reduced-dose TPA to the "exquisite sensitivity" of blood clots lodged in a patient’s lungs to the drug, a consequence of all the infused TPA passing through the lung’s arterial circulation.

In addition to showing a statistically significant benefit from TPA for the study’s primary end point, the average duration of hospitalization in the TPA recipients was 2.2 days, compared with an average of 4.9 days in the control patients, a statistically significant difference. And at the end of the average 28 months of follow-up, three patients in the control arm had a recurrent PE and another three had died, significantly more than the no recurrent PEs and one death in the TPA arm.

Dr. Sharifi and Dr. Crawford said that they had no relevant disclosures.

CHICAGO – A reduced-dose regimen of tissue plasminogen activator and parenteral anticoagulant safely led to improved outcomes in hemodynamically stable patients with a pulmonary embolism in a pilot study with a total of 121 patients treated at one U.S. center.

None of the 61 patients treated with the regimen, which halved the standard dosage of tissue plasminogen activator (TPA) and cut the dosage of enoxaparin or heparin by about 20%-30%, had an intracranial hemorrhage or a major bleeding event, compared with a historic 2%-6% incidence of intracranial hemorrhage and a 6%-20% incidence of major bleeds in hemodynamically unstable pulmonary embolism patients who receive the standard, full dose of both the thrombolytic and anticoagulant, Dr. Mohsen Sharifi said at the meeting.

While he acknowledged that the results need confirmation in a larger study, "in our experience treating deep vein thrombosis [with a similarly low dosage of TPA], we are comfortable that this amount of TPA can be given safely," said Dr. Sharifi, an interventional cardiologist who practices in Mesa, Ariz.

The findings also showed that applying this reduced-dose intervention to hemodynamically stable patients with a pulmonary embolism (PE), who are typically not treated, substantially improved their long-term prognosis by reducing their development of pulmonary hypertension. After an average of 28 months follow-up, 9 of the 58 patients (16%) followed long term and treated with the reduced-dose regimen had pulmonary hypertension, defined as a pulmonary artery systolic pressure greater than 40 mm Hg, compared with pulmonary hypertension in 32 of the 56 control patients (57%) managed by standard treatment with anticoagulation only.

Current guidelines from the American Heart Association call for fibrinolytic treatment only in patients with a massive, acute PE, or in patients with a submassive PE who are hemodynamically unstable or have other clinical evidence of an adverse prognosis (Circulation 2011;123:1788-830). According to Dr. Sharifi, about 5% of all PE patients fall into this category. He estimated that broadening thrombolytic treatment to hemodynamically stable patients who met his study’s inclusion criteria could broaden TPA treatment to an additional 70% of PE patients currently seen in emergency departments.

"I think that, based on the results of this pilot study, you won’t get broad acceptance of treating hemodynamically stable PE patients with thrombolysis," commented Dr. Michael Crawford, chief of general cardiology at the University of California, San Francisco. Two larger studies nearing completion are both examining the efficacy and safety of thrombolysis in patients with submassive PE.

Dr. Sharifi said that despite the small study size, he and his associates were convinced enough by their findings to use the reduced TPA dosage tested in this study on a routine basis when they see patients who meet their enrollment criteria.

The MOPETT (Moderate Pulmonary Embolism Treated with Thrombolysis) study enrolled patients with a PE affecting at least two lobar segments, pulmonary artery systolic pressure greater than 40 mm Hg; right ventricular hypokinesia and enlargement; and at least two symptoms, which could include chest pain, tachypnea greater than 22 respirations/min, tachycardia with a resting heart rate of more than 90 beats/min, dyspnea, cough, oxygen desaturation, and jugular venous pressure more than 12 mm H2O. The average age of the patients was about 59 years, and slightly more than half were women. Their average pulmonary artery systolic pressure at entry was about 50 mm Hg.

Dr. Sharifi and his associates randomized half the patients to receive conventional treatment with anticoagulant only, either enoxaparin or heparin plus warfarin. The other patients received thrombolytic treatment with an infusion of TPA at half the standard dosage, starting in patients who weighed at least 50 kg with a loading dose of 10 mg delivered in 1 minute, and followed by a 40-mg total additional dose administered over 2 hours. Patients who weighed less received the same 10-mg initial dose, but their total dose including the subsequent 2-hour infusion was limited to 0.5 mg/kg. The patients treated with TPA also received concomitant anticoagulation, with either enoxaparin given at 1 mg/kg but not to exceed 80 mg as an initial dose, or heparin at an initial dose of 70 U/kg but capped at 6,000 U, followed by heparin maintenance at 10 U/kg per hour during the TPA infusion (but not exceeding 1,000 U/hour), and then rising to 18 U/kg per hour starting 1 hour after TPA treatment stopped. About 80% of all patients in the study received enoxaparin, and about 20% received heparin.

At 48 hours after starting treatment, average pulmonary artery systolic pressure dropped by 16 mm Hg in the TPA group and by 5 mm Hg in the control patients. By the end of the average 28-month follow-up, average pulmonary artery systolic pressure was 28 mm Hg in the TPA patients and 43 mm Hg in the controls. Dr. Sharifi attributed the efficacy of reduced-dose TPA to the "exquisite sensitivity" of blood clots lodged in a patient’s lungs to the drug, a consequence of all the infused TPA passing through the lung’s arterial circulation.

In addition to showing a statistically significant benefit from TPA for the study’s primary end point, the average duration of hospitalization in the TPA recipients was 2.2 days, compared with an average of 4.9 days in the control patients, a statistically significant difference. And at the end of the average 28 months of follow-up, three patients in the control arm had a recurrent PE and another three had died, significantly more than the no recurrent PEs and one death in the TPA arm.

Dr. Sharifi and Dr. Crawford said that they had no relevant disclosures.

FROM THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF CARDIOLOGY

Major Finding: Pulmonary embolism patients receiving reduced dosages of TPA and anticoagulant had a 16% pulmonary hypertension rate versus 57% in controls.

Data Source: Data came from a single-center, randomized study that enrolled 121 patients with hemodynamically stable pulmonary embolism.

Disclosures: Dr. Sharifi and Dr. Crawford said that they had no relevant disclosures.

Glucose Cocktail Halved Cardiac Arrest in Suspected ACS

CHICAGO – Glucose, insulin, and potassium given in the field to patients with suspected acute coronary syndrome cut in half the odds of pre- or in-hospital cardiac arrest or death in the prospective, double-blind, randomized IMMEDIATE trial.

The benefits of glucose, insulin, and potassium (GIK) were even more pronounced in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), reducing this outcome by a statistically significant 60%, compared with placebo (6% vs. 14%; risk ratio, 0.39).

The study’s primary end point of progression to myocardial infarction at 30 days was reported in 49% of GIK and 53% of placebo patients, a nonsignificant difference.

Although GIK did not prevent infarcts, it significantly reduced their size, coprincipal investigator Dr. Harry P. Selker said at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

"Risks and side effects rates from GIK are very low and GIK is inexpensive, potentially available in all communities, and deserves further evaluation in trials for widespread," he said.

Despite missing its primary end point, the panel of invited discussants was enthusiastic about the potential for IMMEDIATE (Immediate Myocardial Metabolic Enhancement During Initial Assessment and Treatment in Emergency Care) to revive the 50-year-old therapy, long advocated by the late Tufts researcher Dr. Carl Apstein.

Panelist Dr. Bernard Gersh, from the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., asked whether the investigators were surprised at the magnitude of the treatment effect, given that GIK has failed in prior trials involving more than 20,000 patients.

"No, first of all, we know that most of the mortality is in that first hour since cardiac arrest and a lot of its effect is [against] cardiac arrest," replied Dr. Selker, professor of medicine and director of the Center for Cardiovascular Health Services Research at Tufts Medical Center in Boston. Experimental animal studies have also shown a 50% reduction in cardiac arrest. GIK decreases plasma and cellular free fatty acid levels, which are known to damage cell membranes and cause arrhythmias, supports the myocardium when there is less blood flow, and preserves myocardial potassium, an antiarrhythmic.

Notably, a subgroup analysis confirmed a significant benefit for GIK on cardiac arrest or hospital mortality only in those patients who received the therapy within 1 hour of symptom onset (odds ratio, 0.28), compared with those receiving GIK at least 1-6 hours (OR, 0.39) or more than 6 hours after symptom onset (OR, 1.18).

Dr. Elliott Antman, professor of medicine at Harvard University and senior faculty member in the cardiovascular division at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, asked why IMMEDIATE succeeded where so many other earlier GIK trials failed.

GIK was used for 12 hours, not 24-48 hours as previously done in other trials, said Dr. Selker, who also remarked that larger trials are needed to validate the findings since there are opposing data.

IMMEDIATE randomized 911 patients with suspected acute coronary syndrome to usual care or 30% glucose plus 50 IU insulin and 80 mEq potassium chloride/L at 1.5 mL/kg per hour administered en route by paramedics. All patients had a 12-lead ambulance ECG with Acute Ca Ischemia–Time-Insensitive Predictive Instrument (ACI-TIPI) and Thrombolytic Predictive Instrument (TPI) decision support.

Patients had at least one of the following: at least 75% predicted probability of ACS on ACI-TIPI, TPI detection of STEMI, or STEMI identified by local EMS protocol. Their mean age was 63 years and one-third had a history of myocardial infarction. Paramedics were from 36 EMS systems in 13 states across the country.

Pre- or in-hospital cardiac arrest or mortality was reported in 4% of GIK vs. 9% of placebo patients, a significant difference. The individual components of the composite outcome trended in the right direction, but did not achieve significance, Dr. Selker said.

At 30 days, 4% of the 432 GIK patients and 6% of the 479 placebo patients had died, a nonsignificant difference.

Mortality or hospitalization for heart failure was also similar between groups, occurring in 6% of GIK and 8% of placebo patients at 30 days.

Among STEMI patients, only the composite of cardiac arrest or pre- or in-hospital mortality significantly favored the GIK arm.

The percentage of patients with any glucose greater than 300 mg/dL was significantly higher in the GIK arm at 21% vs. 10% in the placebo arm. GIK also raised glucose levels in patients with diabetes (44% vs. 29%), but this did not lead to any serious adverse events, Dr. Selker said.

Dr. Antman asked whether the investigators evaluated the location of the STEMI because of the potential for an imbalance in anterior versus inferior locations that might have favored the GIK group. Dr. Selker said they had not performed that subanalysis.

IMMEDIATE was simultaneously published in JAMA (JAMA 2012 March 27 [doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.426]).

This study was funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Selker and his coauthors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

CHICAGO – Glucose, insulin, and potassium given in the field to patients with suspected acute coronary syndrome cut in half the odds of pre- or in-hospital cardiac arrest or death in the prospective, double-blind, randomized IMMEDIATE trial.

The benefits of glucose, insulin, and potassium (GIK) were even more pronounced in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), reducing this outcome by a statistically significant 60%, compared with placebo (6% vs. 14%; risk ratio, 0.39).

The study’s primary end point of progression to myocardial infarction at 30 days was reported in 49% of GIK and 53% of placebo patients, a nonsignificant difference.

Although GIK did not prevent infarcts, it significantly reduced their size, coprincipal investigator Dr. Harry P. Selker said at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

"Risks and side effects rates from GIK are very low and GIK is inexpensive, potentially available in all communities, and deserves further evaluation in trials for widespread," he said.

Despite missing its primary end point, the panel of invited discussants was enthusiastic about the potential for IMMEDIATE (Immediate Myocardial Metabolic Enhancement During Initial Assessment and Treatment in Emergency Care) to revive the 50-year-old therapy, long advocated by the late Tufts researcher Dr. Carl Apstein.

Panelist Dr. Bernard Gersh, from the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., asked whether the investigators were surprised at the magnitude of the treatment effect, given that GIK has failed in prior trials involving more than 20,000 patients.

"No, first of all, we know that most of the mortality is in that first hour since cardiac arrest and a lot of its effect is [against] cardiac arrest," replied Dr. Selker, professor of medicine and director of the Center for Cardiovascular Health Services Research at Tufts Medical Center in Boston. Experimental animal studies have also shown a 50% reduction in cardiac arrest. GIK decreases plasma and cellular free fatty acid levels, which are known to damage cell membranes and cause arrhythmias, supports the myocardium when there is less blood flow, and preserves myocardial potassium, an antiarrhythmic.

Notably, a subgroup analysis confirmed a significant benefit for GIK on cardiac arrest or hospital mortality only in those patients who received the therapy within 1 hour of symptom onset (odds ratio, 0.28), compared with those receiving GIK at least 1-6 hours (OR, 0.39) or more than 6 hours after symptom onset (OR, 1.18).

Dr. Elliott Antman, professor of medicine at Harvard University and senior faculty member in the cardiovascular division at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, asked why IMMEDIATE succeeded where so many other earlier GIK trials failed.

GIK was used for 12 hours, not 24-48 hours as previously done in other trials, said Dr. Selker, who also remarked that larger trials are needed to validate the findings since there are opposing data.

IMMEDIATE randomized 911 patients with suspected acute coronary syndrome to usual care or 30% glucose plus 50 IU insulin and 80 mEq potassium chloride/L at 1.5 mL/kg per hour administered en route by paramedics. All patients had a 12-lead ambulance ECG with Acute Ca Ischemia–Time-Insensitive Predictive Instrument (ACI-TIPI) and Thrombolytic Predictive Instrument (TPI) decision support.

Patients had at least one of the following: at least 75% predicted probability of ACS on ACI-TIPI, TPI detection of STEMI, or STEMI identified by local EMS protocol. Their mean age was 63 years and one-third had a history of myocardial infarction. Paramedics were from 36 EMS systems in 13 states across the country.

Pre- or in-hospital cardiac arrest or mortality was reported in 4% of GIK vs. 9% of placebo patients, a significant difference. The individual components of the composite outcome trended in the right direction, but did not achieve significance, Dr. Selker said.

At 30 days, 4% of the 432 GIK patients and 6% of the 479 placebo patients had died, a nonsignificant difference.

Mortality or hospitalization for heart failure was also similar between groups, occurring in 6% of GIK and 8% of placebo patients at 30 days.

Among STEMI patients, only the composite of cardiac arrest or pre- or in-hospital mortality significantly favored the GIK arm.

The percentage of patients with any glucose greater than 300 mg/dL was significantly higher in the GIK arm at 21% vs. 10% in the placebo arm. GIK also raised glucose levels in patients with diabetes (44% vs. 29%), but this did not lead to any serious adverse events, Dr. Selker said.

Dr. Antman asked whether the investigators evaluated the location of the STEMI because of the potential for an imbalance in anterior versus inferior locations that might have favored the GIK group. Dr. Selker said they had not performed that subanalysis.

IMMEDIATE was simultaneously published in JAMA (JAMA 2012 March 27 [doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.426]).

This study was funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Selker and his coauthors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

CHICAGO – Glucose, insulin, and potassium given in the field to patients with suspected acute coronary syndrome cut in half the odds of pre- or in-hospital cardiac arrest or death in the prospective, double-blind, randomized IMMEDIATE trial.

The benefits of glucose, insulin, and potassium (GIK) were even more pronounced in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), reducing this outcome by a statistically significant 60%, compared with placebo (6% vs. 14%; risk ratio, 0.39).

The study’s primary end point of progression to myocardial infarction at 30 days was reported in 49% of GIK and 53% of placebo patients, a nonsignificant difference.

Although GIK did not prevent infarcts, it significantly reduced their size, coprincipal investigator Dr. Harry P. Selker said at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

"Risks and side effects rates from GIK are very low and GIK is inexpensive, potentially available in all communities, and deserves further evaluation in trials for widespread," he said.

Despite missing its primary end point, the panel of invited discussants was enthusiastic about the potential for IMMEDIATE (Immediate Myocardial Metabolic Enhancement During Initial Assessment and Treatment in Emergency Care) to revive the 50-year-old therapy, long advocated by the late Tufts researcher Dr. Carl Apstein.

Panelist Dr. Bernard Gersh, from the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., asked whether the investigators were surprised at the magnitude of the treatment effect, given that GIK has failed in prior trials involving more than 20,000 patients.

"No, first of all, we know that most of the mortality is in that first hour since cardiac arrest and a lot of its effect is [against] cardiac arrest," replied Dr. Selker, professor of medicine and director of the Center for Cardiovascular Health Services Research at Tufts Medical Center in Boston. Experimental animal studies have also shown a 50% reduction in cardiac arrest. GIK decreases plasma and cellular free fatty acid levels, which are known to damage cell membranes and cause arrhythmias, supports the myocardium when there is less blood flow, and preserves myocardial potassium, an antiarrhythmic.

Notably, a subgroup analysis confirmed a significant benefit for GIK on cardiac arrest or hospital mortality only in those patients who received the therapy within 1 hour of symptom onset (odds ratio, 0.28), compared with those receiving GIK at least 1-6 hours (OR, 0.39) or more than 6 hours after symptom onset (OR, 1.18).

Dr. Elliott Antman, professor of medicine at Harvard University and senior faculty member in the cardiovascular division at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, asked why IMMEDIATE succeeded where so many other earlier GIK trials failed.

GIK was used for 12 hours, not 24-48 hours as previously done in other trials, said Dr. Selker, who also remarked that larger trials are needed to validate the findings since there are opposing data.

IMMEDIATE randomized 911 patients with suspected acute coronary syndrome to usual care or 30% glucose plus 50 IU insulin and 80 mEq potassium chloride/L at 1.5 mL/kg per hour administered en route by paramedics. All patients had a 12-lead ambulance ECG with Acute Ca Ischemia–Time-Insensitive Predictive Instrument (ACI-TIPI) and Thrombolytic Predictive Instrument (TPI) decision support.

Patients had at least one of the following: at least 75% predicted probability of ACS on ACI-TIPI, TPI detection of STEMI, or STEMI identified by local EMS protocol. Their mean age was 63 years and one-third had a history of myocardial infarction. Paramedics were from 36 EMS systems in 13 states across the country.

Pre- or in-hospital cardiac arrest or mortality was reported in 4% of GIK vs. 9% of placebo patients, a significant difference. The individual components of the composite outcome trended in the right direction, but did not achieve significance, Dr. Selker said.

At 30 days, 4% of the 432 GIK patients and 6% of the 479 placebo patients had died, a nonsignificant difference.

Mortality or hospitalization for heart failure was also similar between groups, occurring in 6% of GIK and 8% of placebo patients at 30 days.

Among STEMI patients, only the composite of cardiac arrest or pre- or in-hospital mortality significantly favored the GIK arm.

The percentage of patients with any glucose greater than 300 mg/dL was significantly higher in the GIK arm at 21% vs. 10% in the placebo arm. GIK also raised glucose levels in patients with diabetes (44% vs. 29%), but this did not lead to any serious adverse events, Dr. Selker said.

Dr. Antman asked whether the investigators evaluated the location of the STEMI because of the potential for an imbalance in anterior versus inferior locations that might have favored the GIK group. Dr. Selker said they had not performed that subanalysis.

IMMEDIATE was simultaneously published in JAMA (JAMA 2012 March 27 [doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.426]).

This study was funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Selker and his coauthors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

FROM THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF CARDIOLOGY

Major Finding: Administration of GIK in patients with suspected acute coronary syndrome reduced the combined end point of pre- or in-hospital cardiac arrest or death by 60%, compared with placebo, a significant difference.

Data Source: The prospective, double-blind randomized trial included 911 patients with suspected acute coronary syndrome.

Disclosures: This study was funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Selker and his coauthors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

Sleeping Too Much or Too Little Puts Heart at Risk

CHICAGO – Sleeping too much as well as too little appears to be detrimental to cardiovascular health, according to large retrospective analysis of the NHANES database.

Individuals who slept less than 6 hours per day had twice the risk of myocardial infarction (odds ratio 2.04) or stroke (OR 2.01), compared with those who slept 6-8 hours, even after adjusting for a multiple confounders associated with cardiovascular risk.

Individuals with less than 6 hours of sleep duration were also at increased risk of heart failure (OR 1.67), Dr. Rohit R. Arora reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

Intriguingly, persons who slept more than 8 hours per night had a twofold increased risk of angina (OR 2.07) as well as an increased risk of coronary artery disease (OR 1.19).

"It seems that the optimal time is 6 to 8 hours," said Dr. Arora, chair of cardiology and professor of medicine at the Chicago Medical School.

He stressed that the analysis could not establish a cause-and-effect relationship, but suggested that patients who sleep more than 8 hours per night may do so because of underlying comorbid conditions such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and diabetes or low socioeconomic status, all of which could contribute to their cardiovascular risk.

Previous studies have shown that insufficient sleep is associated with hyperactivation of the sympathetic nervous system, glucose intolerance, an increase in cortisol levels and blood pressure, decreased variability in heart rate, disruption of the hypothalamic axis, and a general increase in inflammatory markers.

The analysis included 3,019 individuals, at least 45 years of age, who participated in the 2007-2008 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). Patients were asked about sleep quality and then stratified into one of three categories: fewer than 6 hours of sleep a night, 6-8 hours a night, and more than 8 hours of sleep per night.

The analysis adjusted for the covariates of age, systolic blood pressure, gender, body mass index, diabetes, smoking status, total cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol, sleep apnea, and family history of heart attack. The analysis could not determine the underlying level of cardiovascular or cerebrovascular disease in the participants, nor did it evaluate quality of sleep, which emerging data suggests plays a role in certain cardiovascular outcomes, Dr. Arora said.

What is clear from the analysis is that providers should talk to their patients about their sleep, particularly those who are at greater risk for heart disease. The data also support a recommendation for 6-8 hours of sleep per night in current guidelines. As for whether this recommendation should be given early on in life to adolescents, who are known to have inadequate sleep, the recommendation would not be amiss, he said in an interview.

Dr. Arora reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

myocardial infarction, stroke, American College of Cardiology

CHICAGO – Sleeping too much as well as too little appears to be detrimental to cardiovascular health, according to large retrospective analysis of the NHANES database.

Individuals who slept less than 6 hours per day had twice the risk of myocardial infarction (odds ratio 2.04) or stroke (OR 2.01), compared with those who slept 6-8 hours, even after adjusting for a multiple confounders associated with cardiovascular risk.

Individuals with less than 6 hours of sleep duration were also at increased risk of heart failure (OR 1.67), Dr. Rohit R. Arora reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

Intriguingly, persons who slept more than 8 hours per night had a twofold increased risk of angina (OR 2.07) as well as an increased risk of coronary artery disease (OR 1.19).

"It seems that the optimal time is 6 to 8 hours," said Dr. Arora, chair of cardiology and professor of medicine at the Chicago Medical School.

He stressed that the analysis could not establish a cause-and-effect relationship, but suggested that patients who sleep more than 8 hours per night may do so because of underlying comorbid conditions such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and diabetes or low socioeconomic status, all of which could contribute to their cardiovascular risk.

Previous studies have shown that insufficient sleep is associated with hyperactivation of the sympathetic nervous system, glucose intolerance, an increase in cortisol levels and blood pressure, decreased variability in heart rate, disruption of the hypothalamic axis, and a general increase in inflammatory markers.

The analysis included 3,019 individuals, at least 45 years of age, who participated in the 2007-2008 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). Patients were asked about sleep quality and then stratified into one of three categories: fewer than 6 hours of sleep a night, 6-8 hours a night, and more than 8 hours of sleep per night.

The analysis adjusted for the covariates of age, systolic blood pressure, gender, body mass index, diabetes, smoking status, total cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol, sleep apnea, and family history of heart attack. The analysis could not determine the underlying level of cardiovascular or cerebrovascular disease in the participants, nor did it evaluate quality of sleep, which emerging data suggests plays a role in certain cardiovascular outcomes, Dr. Arora said.

What is clear from the analysis is that providers should talk to their patients about their sleep, particularly those who are at greater risk for heart disease. The data also support a recommendation for 6-8 hours of sleep per night in current guidelines. As for whether this recommendation should be given early on in life to adolescents, who are known to have inadequate sleep, the recommendation would not be amiss, he said in an interview.

Dr. Arora reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

CHICAGO – Sleeping too much as well as too little appears to be detrimental to cardiovascular health, according to large retrospective analysis of the NHANES database.

Individuals who slept less than 6 hours per day had twice the risk of myocardial infarction (odds ratio 2.04) or stroke (OR 2.01), compared with those who slept 6-8 hours, even after adjusting for a multiple confounders associated with cardiovascular risk.

Individuals with less than 6 hours of sleep duration were also at increased risk of heart failure (OR 1.67), Dr. Rohit R. Arora reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

Intriguingly, persons who slept more than 8 hours per night had a twofold increased risk of angina (OR 2.07) as well as an increased risk of coronary artery disease (OR 1.19).

"It seems that the optimal time is 6 to 8 hours," said Dr. Arora, chair of cardiology and professor of medicine at the Chicago Medical School.

He stressed that the analysis could not establish a cause-and-effect relationship, but suggested that patients who sleep more than 8 hours per night may do so because of underlying comorbid conditions such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and diabetes or low socioeconomic status, all of which could contribute to their cardiovascular risk.

Previous studies have shown that insufficient sleep is associated with hyperactivation of the sympathetic nervous system, glucose intolerance, an increase in cortisol levels and blood pressure, decreased variability in heart rate, disruption of the hypothalamic axis, and a general increase in inflammatory markers.

The analysis included 3,019 individuals, at least 45 years of age, who participated in the 2007-2008 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). Patients were asked about sleep quality and then stratified into one of three categories: fewer than 6 hours of sleep a night, 6-8 hours a night, and more than 8 hours of sleep per night.

The analysis adjusted for the covariates of age, systolic blood pressure, gender, body mass index, diabetes, smoking status, total cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol, sleep apnea, and family history of heart attack. The analysis could not determine the underlying level of cardiovascular or cerebrovascular disease in the participants, nor did it evaluate quality of sleep, which emerging data suggests plays a role in certain cardiovascular outcomes, Dr. Arora said.

What is clear from the analysis is that providers should talk to their patients about their sleep, particularly those who are at greater risk for heart disease. The data also support a recommendation for 6-8 hours of sleep per night in current guidelines. As for whether this recommendation should be given early on in life to adolescents, who are known to have inadequate sleep, the recommendation would not be amiss, he said in an interview.

Dr. Arora reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

myocardial infarction, stroke, American College of Cardiology

myocardial infarction, stroke, American College of Cardiology

FROM THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF CARDIOLOGY

Major Finding: Persons who slept more than eight hours per night had a twofold increased risk of angina (2.07) as well as an increased risk of coronary artery disease (OR 1.19).

Data Source: Retrospective analysis of 3,019 individuals who participated in the 2007-2008 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES).

Disclosures: Dr. Arora reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

Tracking Method Improves Outcomes in CRT

Speckle-tracking echocardiography has been shown to significantly improve clinical outcomes when used in cardiac resynchronization therapy, according to results from a randomized, controlled trial.

The finding adds to the increasing body of evidence that individualized placement of the ventricular pacing lead in CRT – away from scar and on the most delayed segment of contraction – can result in better outcomes.

In research published online March 7 in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, Dr. Fakhar Z. Khan of Papworth Hospital, Cambridge, U.K., and colleagues, showed that 70% of heart-failure patients treated with CRT guided by speckle-tracking saw improvement at 6 months, compared with 55% treated with unguided CRT (J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2012 [(doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2011.12.030]).

Cardiac resynchronization therapy is used to coordinate contractions in people with heart failure who have failed medical therapies. Speckle-tracking echocardiography is an imaging technique that tracks interference patterns and natural acoustic reflections to show tissue deformation and motion.

Because recent evidence has increasingly suggested that the optimal positioning of the left ventricular pacing lead in CRT is at the most delayed site of contraction and away from myocardial scar (J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2010;55:566-75; J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2010;56:774-81), speckle tracking has been used to help identify the ideal sites for each patient. Conventional CRT, by contrast, places the LV lead at a lateral or postlateral branch of the coronary sinus in all patients.

For their study comparing conventional unguided CRT with guided CRT, Dr. Khan and colleagues randomized 220 men and women scheduled to undergo CRT. In the study group (N = 110), patients were analyzed with two-dimensional speckle-tracking radial strain imaging to determine the ideal LV lead placing.

Controls (N = 110) underwent standard unguided CRT. Both patients and assessors were blinded to group assignment before and after surgery. The primary end point of the study was response at 6 months, defined as a 15% or greater reduction in left ventricular end-systolic volume, or LVESV.

Secondary end points included clinical response (defined as improvement in New York Heart Association functional class of at least 1 level), 2-year all-cause mortality, and heart failure–related hospitalization combined with all-cause mortality at 2 years. A total of seven patients in the intervention group and six in the control group died prior to the intervention or were lost to follow-up.

The results showed that the speckle-tracking group had significantly greater proportion of responders at 6 months than did the control group (70% vs. 55%). The tracking group also saw NYHA functional class improve in 83% of patients, compared with 65% in conventional CRT, also a significant difference. Though there were no significant differences in 2-year all-cause mortality, investigators saw significantly lower rates of the combined end point of all cause mortality and hospitalization.

"The conventional approach to resynchronization has been to direct the LV lead to the lateral and posterior wall based on the benefit shown in early hemodynamic studies and the observation that delayed segments predominate at these sites," Dr. Khan and colleagues wrote in their analysis.

"However, recent data support a more individualized approach to LV lead placement with significant interindividual and intraindividual variation in the optimal LV lead position."

Furthermore, the investigators wrote, "in this randomized study, subgroup analyses confirm previous reports that the greatest clinical response is seen in patients with a concordant LV lead, together with improved survival and a reduction in the combined end point of death and heart failure–related hospitalization."

Dr. Khan and colleagues argued that "an individualized approach to LV lead placement should be considered in all patients undergoing CRT for advanced heart failure."

The investigators noted that newer imaging techniques, such as three-dimensional speckle tracking, might be better than the one they used for their study. Inadequate image quality resulted in 11% of initially recruited patients being excluded before randomization, they said.

They also noted as a limitation of their study that it made no attempt to preselect patients on the basis of dyssynchrony parameters, nor did it consider the extent of total scar burden.

"The presence of both of these parameters would tend to reduce the overall benefit, although this would be distributed in both groups. CRT response may therefore be enhanced by integrating measures of dyssynchrony and total scar burden with a targeted approach to lead placement, and such an approach should be tested in future studies," Dr. Khan and colleagues wrote.

Dr. Khan’s study was funded by the Addenbrooke’s Charitable Trust, Papworth Hospital Research and Development Department, Cambridge Biomedical Research Center, the U.K. National Institute for Health Research. The authors had no relevant disclosures.

The inability to predict individual responses has been the Achilles’ heel of heart failure RCTs, including CRT trials. It is remarkable, however, that for CRT, many more efforts have been devoted to identifying and predicting responders. Initial small single-center studies reported a favorable outlook for several echocardiographic measures of mechanical dyssynchrony in predicting responders. A subsequent large multicenter study, however, the PROSPECT (Predictors of Response to CRT) trial, failed to identify a useful measurement using conventional and tissue Doppler-based methods (Circulation 2008;117:2608-16).

This important study not only identified an important parameter for selecting responders but also provided indirect support for efforts aimed at identifying predictors of CRT response in individual patients. Khan et al. should be commended for the successful completion of this RCT, which is likely to not only stimulate further innovations in imaging modalities and technical approaches but also more clinical trials that incorporate the assessment of the role of surgical approaches in their design.

Jalal K. Ghali, M.D., is in the DMC Cardiovascular Institute in Detroit. These remarks were taken from his editorial accompanying Dr. Kahn’s report (J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2012 [doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2012.01.018]). He had no relevant disclosures.

The inability to predict individual responses has been the Achilles’ heel of heart failure RCTs, including CRT trials. It is remarkable, however, that for CRT, many more efforts have been devoted to identifying and predicting responders. Initial small single-center studies reported a favorable outlook for several echocardiographic measures of mechanical dyssynchrony in predicting responders. A subsequent large multicenter study, however, the PROSPECT (Predictors of Response to CRT) trial, failed to identify a useful measurement using conventional and tissue Doppler-based methods (Circulation 2008;117:2608-16).

This important study not only identified an important parameter for selecting responders but also provided indirect support for efforts aimed at identifying predictors of CRT response in individual patients. Khan et al. should be commended for the successful completion of this RCT, which is likely to not only stimulate further innovations in imaging modalities and technical approaches but also more clinical trials that incorporate the assessment of the role of surgical approaches in their design.

Jalal K. Ghali, M.D., is in the DMC Cardiovascular Institute in Detroit. These remarks were taken from his editorial accompanying Dr. Kahn’s report (J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2012 [doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2012.01.018]). He had no relevant disclosures.

The inability to predict individual responses has been the Achilles’ heel of heart failure RCTs, including CRT trials. It is remarkable, however, that for CRT, many more efforts have been devoted to identifying and predicting responders. Initial small single-center studies reported a favorable outlook for several echocardiographic measures of mechanical dyssynchrony in predicting responders. A subsequent large multicenter study, however, the PROSPECT (Predictors of Response to CRT) trial, failed to identify a useful measurement using conventional and tissue Doppler-based methods (Circulation 2008;117:2608-16).

This important study not only identified an important parameter for selecting responders but also provided indirect support for efforts aimed at identifying predictors of CRT response in individual patients. Khan et al. should be commended for the successful completion of this RCT, which is likely to not only stimulate further innovations in imaging modalities and technical approaches but also more clinical trials that incorporate the assessment of the role of surgical approaches in their design.

Jalal K. Ghali, M.D., is in the DMC Cardiovascular Institute in Detroit. These remarks were taken from his editorial accompanying Dr. Kahn’s report (J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2012 [doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2012.01.018]). He had no relevant disclosures.

Speckle-tracking echocardiography has been shown to significantly improve clinical outcomes when used in cardiac resynchronization therapy, according to results from a randomized, controlled trial.

The finding adds to the increasing body of evidence that individualized placement of the ventricular pacing lead in CRT – away from scar and on the most delayed segment of contraction – can result in better outcomes.

In research published online March 7 in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, Dr. Fakhar Z. Khan of Papworth Hospital, Cambridge, U.K., and colleagues, showed that 70% of heart-failure patients treated with CRT guided by speckle-tracking saw improvement at 6 months, compared with 55% treated with unguided CRT (J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2012 [(doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2011.12.030]).

Cardiac resynchronization therapy is used to coordinate contractions in people with heart failure who have failed medical therapies. Speckle-tracking echocardiography is an imaging technique that tracks interference patterns and natural acoustic reflections to show tissue deformation and motion.

Because recent evidence has increasingly suggested that the optimal positioning of the left ventricular pacing lead in CRT is at the most delayed site of contraction and away from myocardial scar (J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2010;55:566-75; J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2010;56:774-81), speckle tracking has been used to help identify the ideal sites for each patient. Conventional CRT, by contrast, places the LV lead at a lateral or postlateral branch of the coronary sinus in all patients.

For their study comparing conventional unguided CRT with guided CRT, Dr. Khan and colleagues randomized 220 men and women scheduled to undergo CRT. In the study group (N = 110), patients were analyzed with two-dimensional speckle-tracking radial strain imaging to determine the ideal LV lead placing.

Controls (N = 110) underwent standard unguided CRT. Both patients and assessors were blinded to group assignment before and after surgery. The primary end point of the study was response at 6 months, defined as a 15% or greater reduction in left ventricular end-systolic volume, or LVESV.

Secondary end points included clinical response (defined as improvement in New York Heart Association functional class of at least 1 level), 2-year all-cause mortality, and heart failure–related hospitalization combined with all-cause mortality at 2 years. A total of seven patients in the intervention group and six in the control group died prior to the intervention or were lost to follow-up.

The results showed that the speckle-tracking group had significantly greater proportion of responders at 6 months than did the control group (70% vs. 55%). The tracking group also saw NYHA functional class improve in 83% of patients, compared with 65% in conventional CRT, also a significant difference. Though there were no significant differences in 2-year all-cause mortality, investigators saw significantly lower rates of the combined end point of all cause mortality and hospitalization.

"The conventional approach to resynchronization has been to direct the LV lead to the lateral and posterior wall based on the benefit shown in early hemodynamic studies and the observation that delayed segments predominate at these sites," Dr. Khan and colleagues wrote in their analysis.

"However, recent data support a more individualized approach to LV lead placement with significant interindividual and intraindividual variation in the optimal LV lead position."

Furthermore, the investigators wrote, "in this randomized study, subgroup analyses confirm previous reports that the greatest clinical response is seen in patients with a concordant LV lead, together with improved survival and a reduction in the combined end point of death and heart failure–related hospitalization."

Dr. Khan and colleagues argued that "an individualized approach to LV lead placement should be considered in all patients undergoing CRT for advanced heart failure."

The investigators noted that newer imaging techniques, such as three-dimensional speckle tracking, might be better than the one they used for their study. Inadequate image quality resulted in 11% of initially recruited patients being excluded before randomization, they said.

They also noted as a limitation of their study that it made no attempt to preselect patients on the basis of dyssynchrony parameters, nor did it consider the extent of total scar burden.

"The presence of both of these parameters would tend to reduce the overall benefit, although this would be distributed in both groups. CRT response may therefore be enhanced by integrating measures of dyssynchrony and total scar burden with a targeted approach to lead placement, and such an approach should be tested in future studies," Dr. Khan and colleagues wrote.

Dr. Khan’s study was funded by the Addenbrooke’s Charitable Trust, Papworth Hospital Research and Development Department, Cambridge Biomedical Research Center, the U.K. National Institute for Health Research. The authors had no relevant disclosures.

Speckle-tracking echocardiography has been shown to significantly improve clinical outcomes when used in cardiac resynchronization therapy, according to results from a randomized, controlled trial.

The finding adds to the increasing body of evidence that individualized placement of the ventricular pacing lead in CRT – away from scar and on the most delayed segment of contraction – can result in better outcomes.

In research published online March 7 in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, Dr. Fakhar Z. Khan of Papworth Hospital, Cambridge, U.K., and colleagues, showed that 70% of heart-failure patients treated with CRT guided by speckle-tracking saw improvement at 6 months, compared with 55% treated with unguided CRT (J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2012 [(doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2011.12.030]).

Cardiac resynchronization therapy is used to coordinate contractions in people with heart failure who have failed medical therapies. Speckle-tracking echocardiography is an imaging technique that tracks interference patterns and natural acoustic reflections to show tissue deformation and motion.

Because recent evidence has increasingly suggested that the optimal positioning of the left ventricular pacing lead in CRT is at the most delayed site of contraction and away from myocardial scar (J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2010;55:566-75; J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2010;56:774-81), speckle tracking has been used to help identify the ideal sites for each patient. Conventional CRT, by contrast, places the LV lead at a lateral or postlateral branch of the coronary sinus in all patients.

For their study comparing conventional unguided CRT with guided CRT, Dr. Khan and colleagues randomized 220 men and women scheduled to undergo CRT. In the study group (N = 110), patients were analyzed with two-dimensional speckle-tracking radial strain imaging to determine the ideal LV lead placing.

Controls (N = 110) underwent standard unguided CRT. Both patients and assessors were blinded to group assignment before and after surgery. The primary end point of the study was response at 6 months, defined as a 15% or greater reduction in left ventricular end-systolic volume, or LVESV.

Secondary end points included clinical response (defined as improvement in New York Heart Association functional class of at least 1 level), 2-year all-cause mortality, and heart failure–related hospitalization combined with all-cause mortality at 2 years. A total of seven patients in the intervention group and six in the control group died prior to the intervention or were lost to follow-up.

The results showed that the speckle-tracking group had significantly greater proportion of responders at 6 months than did the control group (70% vs. 55%). The tracking group also saw NYHA functional class improve in 83% of patients, compared with 65% in conventional CRT, also a significant difference. Though there were no significant differences in 2-year all-cause mortality, investigators saw significantly lower rates of the combined end point of all cause mortality and hospitalization.

"The conventional approach to resynchronization has been to direct the LV lead to the lateral and posterior wall based on the benefit shown in early hemodynamic studies and the observation that delayed segments predominate at these sites," Dr. Khan and colleagues wrote in their analysis.

"However, recent data support a more individualized approach to LV lead placement with significant interindividual and intraindividual variation in the optimal LV lead position."

Furthermore, the investigators wrote, "in this randomized study, subgroup analyses confirm previous reports that the greatest clinical response is seen in patients with a concordant LV lead, together with improved survival and a reduction in the combined end point of death and heart failure–related hospitalization."

Dr. Khan and colleagues argued that "an individualized approach to LV lead placement should be considered in all patients undergoing CRT for advanced heart failure."

The investigators noted that newer imaging techniques, such as three-dimensional speckle tracking, might be better than the one they used for their study. Inadequate image quality resulted in 11% of initially recruited patients being excluded before randomization, they said.

They also noted as a limitation of their study that it made no attempt to preselect patients on the basis of dyssynchrony parameters, nor did it consider the extent of total scar burden.

"The presence of both of these parameters would tend to reduce the overall benefit, although this would be distributed in both groups. CRT response may therefore be enhanced by integrating measures of dyssynchrony and total scar burden with a targeted approach to lead placement, and such an approach should be tested in future studies," Dr. Khan and colleagues wrote.

Dr. Khan’s study was funded by the Addenbrooke’s Charitable Trust, Papworth Hospital Research and Development Department, Cambridge Biomedical Research Center, the U.K. National Institute for Health Research. The authors had no relevant disclosures.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF CARDIOLOGY

Major Finding: 70% of heart failure patients receiving cardiac resynchronization therapy with guided imaging to determine individualized placement saw significant improvement at 6 months, compared with 55% of those receiving CRT using standard placement protocol.

Data Source: These results came from a two-center randomized controlled trial of 220 patients between April 2009 and July 2010.

Disclosures: The authors had no relevant disclosures.

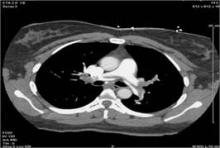

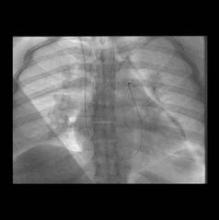

Community Hospital Offers Catheter-Directed Pulmonary Thrombolysis

Few, if any, vascular specialists are aggressively treating massive or submassive pulmonary embolism with catheter-directed thrombolytic therapy at community hospitals, but it is feasible and can have good outcomes with proper planning and preparation, according to Dr. Jeffrey Y. Wang.

Catheter-directed thrombolytic therapy for massive or submassive pulmonary embolism (PE) can shorten stays in the ICU and the hospital, reduce or eliminate the need for home oxygen therapy, and help restore right heart function, he said. However, catheter-directed interventions for these patients is rare outside of academic or tertiary-care settings, probably because of a lack of randomized trials, little retrospective data, and lack of expertise, he said.

For physicians considering this treatment at their own community hospitals, Dr. Wang emphasized that preparing the hospital and protocols are as important as is technical expertise in doing the procedure. The fluoroscopy suite must be available on an emergency basis, for example.

"In our institution, we use the same protocols for call-in and transport to the cath lab as for ST-elevation myocardial infarction, which allows us to get the patient up and into the fluoroscopy suite within 30 minutes," said Dr. Wang of Shady Grove Adventist Hospital, Rockville, Md.

Before doing his first case, he made sure that protocols were in place in the emergency department, in the ICU, and with the hospitalist team for the early detection of deep vein thrombosis and PE, notification of the appropriate staff, and posttreatment care of patients.

Systemic anticoagulation has been the mainstay of treatment for PE, but the American Heart Association and the American College of Chest Physicians have recommended more aggressive therapy for massive and submassive PEs, Dr. Wang said. Up to 60% of patients with massive PE die, data suggest, with two-thirds of the deaths occurring in the first hour of embolism formation. Within 30 days of submassive PE formation, 15%-20% of patients die secondary to pulmonary hypertension and subsequent cor pulmonale.

Approximately 30% of all 500,000 symptomatic PEs diagnosed each year in the United States lead to death. Even among inpatients who are diagnosed with a PE while in the hospital, the mortality rate is approximately 10%-15%, he said.

Until recently, there was no Food and Drug Administration–approved device for catheter-directed thrombolytic therapy. "There’s also not a purpose-built device to help you with these types of procedures," Dr. Wang said.

At the annual meeting of the Southern Association for Vascular Surgery, he described treating nine women and three men who had a total of seven massive and five submassive PEs. Catheter-directed thrombolytic therapy was offered to patients with massive or submassive PE if they were hemodynamically unstable or had right heart dysfunction, elevated troponin levels, or pulmonary artery pressures greater than 70 mm Hg, or if they were not being weaned off intubation for oxygen within 5 days, Dr. Wang said. He excluded patients who were actively bleeding or who were not able to tolerate any systemic anticoagulation – "not even aspirin," he said.

Recent surgery was not a disqualifying factor. "Typically those patients were orthopedic in nature, with a hip or knee replacement," Dr. Wang said. The patient would develop a big PE, and the orthopedist would give him the green light for aggressive treatment.

All procedures were technically successful. One patient developed hemodynamically significant bradycardia, but all were off supplemental oxygen within 24 hours of the procedure, and there were no bleeding events.

One patient died 14 hours after the procedure, most likely due to a paradoxical embolism to the intestine, Dr. Wang said. The 11 surviving patients were discharged to home within 48 hours of the intervention.

His technique includes accessing the internal jugular vein to get to the pulmonary artery, placing a vena cava filter, and giving tissue plasminogen activator as the lytic agent. All patients had a spiral CT scan before going to the catheterization lab, so pulmonary angiography was not routinely performed.

He reserved mechanical (catheter) thrombectomy for some patients with massive thromboembolism. Instead of being guided by angiography, he determined the duration of mechanical thrombectomy by the patient’s blood pressure, pulse, and oxygen saturation.

"I discontinued mechanical thrombectomy once oxygen saturation was above 95%, they’re weaning off their inotropes, and the pulse rate was trending toward normal," he said.

For some patients who developed nonsinus arrhythmias due to the wire manipulations within the heart and pulmonary arteries, he removed the wire device, waited for it to resolve, and continued. A minority of patients whose arrhythmias continued to occur during the intervention received calcium blockade or beta blockade.

Patients who received mechanical thrombectomy developed dark or bloody urine that resolved within 48 hours with hydration.

Follow-up at 2 weeks assessed general function and access sites, and patients had a repeat echocardiogram at 1 month. If they were doing well functionally and pulmonary hypertension had resolved, Dr. Wang offered to remove the vena cava filter. All but one patient accepted. All were to remain on systemic anticoagulation for 6-12 months, and patients with massive PE underwent hematologic workups.

Dr. Wang reported having no financial disclosures.

It amazes me that over many decades, the treatment of pulmonary embolism has remained stagnant. There have been no significant changes in the way we treat these patients. Most are treated with systemic anticoagulation and prolonged warfarin therapy.

There are many limitations to the use of systemic thrombolysis. The most important one is a high incidence of bleeding complications, about 20%-40%. Surgical thrombectomy also has limitations and is performed in a very limited number of centers, with mortality rates of about 10%-20%.

There is no question in my mind that there is a large potential benefit in treating patients with catheter-directed thrombolysis, particularly patients with massive pulmonary embolism. There’s also a potential benefit from catheter-directed thrombolysis in a large subgroup of patients with submassive pulmonary embolism. Those patients may benefit the most in terms of prevention of pulmonary hypertension.

Many of these questions are being investigated now in a European prospective, randomized trial comparing catheter-guided pulmonary thrombolysis to chemical thrombolysis. In the Unites States, there are a couple of registries for these patients, and a randomized trial is expected to start in the near future. I encourage vascular specialists to enroll patients in these.

Dr. Juan Ayerdi is a clinical assistant professor of vascular surgery at the Medical Center of Central Georgia, Macon. He made these remarks as the discussant of Dr. Wang’s presentation at the meeting. Dr. Ayerdi reported having no financial disclosures.

It amazes me that over many decades, the treatment of pulmonary embolism has remained stagnant. There have been no significant changes in the way we treat these patients. Most are treated with systemic anticoagulation and prolonged warfarin therapy.

There are many limitations to the use of systemic thrombolysis. The most important one is a high incidence of bleeding complications, about 20%-40%. Surgical thrombectomy also has limitations and is performed in a very limited number of centers, with mortality rates of about 10%-20%.

There is no question in my mind that there is a large potential benefit in treating patients with catheter-directed thrombolysis, particularly patients with massive pulmonary embolism. There’s also a potential benefit from catheter-directed thrombolysis in a large subgroup of patients with submassive pulmonary embolism. Those patients may benefit the most in terms of prevention of pulmonary hypertension.

Many of these questions are being investigated now in a European prospective, randomized trial comparing catheter-guided pulmonary thrombolysis to chemical thrombolysis. In the Unites States, there are a couple of registries for these patients, and a randomized trial is expected to start in the near future. I encourage vascular specialists to enroll patients in these.

Dr. Juan Ayerdi is a clinical assistant professor of vascular surgery at the Medical Center of Central Georgia, Macon. He made these remarks as the discussant of Dr. Wang’s presentation at the meeting. Dr. Ayerdi reported having no financial disclosures.

It amazes me that over many decades, the treatment of pulmonary embolism has remained stagnant. There have been no significant changes in the way we treat these patients. Most are treated with systemic anticoagulation and prolonged warfarin therapy.

There are many limitations to the use of systemic thrombolysis. The most important one is a high incidence of bleeding complications, about 20%-40%. Surgical thrombectomy also has limitations and is performed in a very limited number of centers, with mortality rates of about 10%-20%.

There is no question in my mind that there is a large potential benefit in treating patients with catheter-directed thrombolysis, particularly patients with massive pulmonary embolism. There’s also a potential benefit from catheter-directed thrombolysis in a large subgroup of patients with submassive pulmonary embolism. Those patients may benefit the most in terms of prevention of pulmonary hypertension.

Many of these questions are being investigated now in a European prospective, randomized trial comparing catheter-guided pulmonary thrombolysis to chemical thrombolysis. In the Unites States, there are a couple of registries for these patients, and a randomized trial is expected to start in the near future. I encourage vascular specialists to enroll patients in these.

Dr. Juan Ayerdi is a clinical assistant professor of vascular surgery at the Medical Center of Central Georgia, Macon. He made these remarks as the discussant of Dr. Wang’s presentation at the meeting. Dr. Ayerdi reported having no financial disclosures.

Few, if any, vascular specialists are aggressively treating massive or submassive pulmonary embolism with catheter-directed thrombolytic therapy at community hospitals, but it is feasible and can have good outcomes with proper planning and preparation, according to Dr. Jeffrey Y. Wang.

Catheter-directed thrombolytic therapy for massive or submassive pulmonary embolism (PE) can shorten stays in the ICU and the hospital, reduce or eliminate the need for home oxygen therapy, and help restore right heart function, he said. However, catheter-directed interventions for these patients is rare outside of academic or tertiary-care settings, probably because of a lack of randomized trials, little retrospective data, and lack of expertise, he said.

For physicians considering this treatment at their own community hospitals, Dr. Wang emphasized that preparing the hospital and protocols are as important as is technical expertise in doing the procedure. The fluoroscopy suite must be available on an emergency basis, for example.

"In our institution, we use the same protocols for call-in and transport to the cath lab as for ST-elevation myocardial infarction, which allows us to get the patient up and into the fluoroscopy suite within 30 minutes," said Dr. Wang of Shady Grove Adventist Hospital, Rockville, Md.

Before doing his first case, he made sure that protocols were in place in the emergency department, in the ICU, and with the hospitalist team for the early detection of deep vein thrombosis and PE, notification of the appropriate staff, and posttreatment care of patients.

Systemic anticoagulation has been the mainstay of treatment for PE, but the American Heart Association and the American College of Chest Physicians have recommended more aggressive therapy for massive and submassive PEs, Dr. Wang said. Up to 60% of patients with massive PE die, data suggest, with two-thirds of the deaths occurring in the first hour of embolism formation. Within 30 days of submassive PE formation, 15%-20% of patients die secondary to pulmonary hypertension and subsequent cor pulmonale.

Approximately 30% of all 500,000 symptomatic PEs diagnosed each year in the United States lead to death. Even among inpatients who are diagnosed with a PE while in the hospital, the mortality rate is approximately 10%-15%, he said.

Until recently, there was no Food and Drug Administration–approved device for catheter-directed thrombolytic therapy. "There’s also not a purpose-built device to help you with these types of procedures," Dr. Wang said.

At the annual meeting of the Southern Association for Vascular Surgery, he described treating nine women and three men who had a total of seven massive and five submassive PEs. Catheter-directed thrombolytic therapy was offered to patients with massive or submassive PE if they were hemodynamically unstable or had right heart dysfunction, elevated troponin levels, or pulmonary artery pressures greater than 70 mm Hg, or if they were not being weaned off intubation for oxygen within 5 days, Dr. Wang said. He excluded patients who were actively bleeding or who were not able to tolerate any systemic anticoagulation – "not even aspirin," he said.

Recent surgery was not a disqualifying factor. "Typically those patients were orthopedic in nature, with a hip or knee replacement," Dr. Wang said. The patient would develop a big PE, and the orthopedist would give him the green light for aggressive treatment.

All procedures were technically successful. One patient developed hemodynamically significant bradycardia, but all were off supplemental oxygen within 24 hours of the procedure, and there were no bleeding events.

One patient died 14 hours after the procedure, most likely due to a paradoxical embolism to the intestine, Dr. Wang said. The 11 surviving patients were discharged to home within 48 hours of the intervention.

His technique includes accessing the internal jugular vein to get to the pulmonary artery, placing a vena cava filter, and giving tissue plasminogen activator as the lytic agent. All patients had a spiral CT scan before going to the catheterization lab, so pulmonary angiography was not routinely performed.

He reserved mechanical (catheter) thrombectomy for some patients with massive thromboembolism. Instead of being guided by angiography, he determined the duration of mechanical thrombectomy by the patient’s blood pressure, pulse, and oxygen saturation.

"I discontinued mechanical thrombectomy once oxygen saturation was above 95%, they’re weaning off their inotropes, and the pulse rate was trending toward normal," he said.

For some patients who developed nonsinus arrhythmias due to the wire manipulations within the heart and pulmonary arteries, he removed the wire device, waited for it to resolve, and continued. A minority of patients whose arrhythmias continued to occur during the intervention received calcium blockade or beta blockade.