User login

Influenza tied to long-term increased risk for Parkinson’s disease

Influenza infection is linked to a subsequent diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease (PD) more than 10 years later, resurfacing a long-held debate about whether infection increases the risk for movement disorders over the long term.

In a large case-control study, investigators found and by more than 70% for PD occurring more than 10 years after the flu.

“This study is not definitive by any means, but it certainly suggests there are potential long-term consequences from influenza,” study investigator Noelle M. Cocoros, DSc, research scientist at Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute and Harvard Medical School, Boston, said in an interview.

The study was published online Oct. 25 in JAMA Neurology.

Ongoing debate

The debate about whether influenza is associated with PD has been going on as far back as the 1918 influenza pandemic, when experts documented parkinsonism in affected individuals.

Using data from the Danish patient registry, researchers identified 10,271 subjects diagnosed with PD during a 17-year period (2000-2016). Of these, 38.7% were female, and the mean age was 71.4 years.

They matched these subjects for age and sex to 51,355 controls without PD. Compared with controls, slightly fewer individuals with PD had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or emphysema, but there was a similar distribution of cardiovascular disease and various other conditions.

Researchers collected data on influenza diagnoses from inpatient and outpatient hospital clinics from 1977 to 2016. They plotted these by month and year on a graph, calculated the median number of diagnoses per month, and identified peaks as those with more than threefold the median.

They categorized cases in groups related to the time between the infection and PD: More than 10 years, 10-15 years, and more than 15 years.

The time lapse accounts for a rather long “run-up” to PD, said Dr. Cocoros. There’s a sometimes decades-long preclinical phase before patients develop typical motor signs and a prodromal phase where they may present with nonmotor symptoms such as sleep disorders and constipation.

“We expected there would be at least 10 years between any infection and PD if there was an association present,” said Dr. Cocoros.

Investigators found an association between influenza exposure and PD diagnosis “that held up over time,” she said.

For more than 10 years before PD, the likelihood of a diagnosis for the infected compared with the unexposed was increased 73% (odds ratio [OR] 1.73; 95% confidence interval, 1.11-2.71; P = .02) after adjustment for cardiovascular disease, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, emphysema, lung cancer, Crohn’s disease, and ulcerative colitis.

The odds increased with more time from infection. For more than 15 years, the adjusted OR was 1.91 (95% CI, 1.14 - 3.19; P =.01).

However, for the 10- to 15-year time frame, the point estimate was reduced and the CI nonsignificant (OR, 1.33; 95% CI, 0.54-3.27; P = .53). This “is a little hard to interpret,” but could be a result of the small numbers, exposure misclassification, or because “the longer time interval is what’s meaningful,” said Dr. Cocoros.

Potential COVID-19–related PD surge?

In a sensitivity analysis, researchers looked at peak infection activity. “We wanted to increase the likelihood of these diagnoses representing actual infection,” Dr. Cocoros noted.

Here, the OR was still elevated at more than 10 years, but the CI was quite wide and included 1 (OR, 1.52; 95% CI, 0.80-2.89; P = .21). “So the association holds up, but the estimates are quite unstable,” said Dr. Cocoros.

Researchers examined associations with numerous other infection types, but did not see the same trend over time. Some infections – for example, gastrointestinal infections and septicemia – were associated with PD within 5 years, but most associations appeared to be null after more than 10 years.

“There seemed to be associations earlier between the infection and PD, which we interpret to suggest there’s actually not a meaningful association,” said Dr. Cocoros.

An exception might be urinary tract infections (UTIs), where after 10 years, the adjusted OR was 1.19 (95% CI, 1.01-1.40). Research suggests patients with PD often have UTIs and neurogenic bladder.

“It’s possible that UTIs could be an early symptom of PD rather than a causative factor,” said Dr. Cocoros.

It’s unclear how influenza might lead to PD but it could be that the virus gets into the central nervous system, resulting in neuroinflammation. Cytokines generated in response to the influenza infection might damage the brain.

“The infection could be a ‘primer’ or an initial ‘hit’ to the system, maybe setting people up for PD,” said Dr. Cocoros.

As for the current COVID-19 pandemic, some experts are concerned about a potential surge in PD cases in decades to come, and are calling for prospective monitoring of patients with this infection, said Dr. Cocoros.

However, she noted that infections don’t account for all PD cases and that genetic and environmental factors also influence risk.

Many individuals who contract influenza don’t seek medical care or get tested, so it’s possible the study counted those who had the infection as unexposed. Another potential study limitation was that small numbers for some infections, for example, Helicobacter pylori and hepatitis C, limited the ability to interpret results.

‘Exciting and important’ findings

Commenting on the research for this news organization, Aparna Wagle Shukla, MD, professor, Norman Fixel Institute for Neurological Diseases, University of Florida, Gainesville, said the results amid the current pandemic are “exciting and important” and “have reinvigorated interest” in the role of infection in PD.

However, the study had some limitations, an important one being lack of accounting for confounding factors, including environmental factors, she said. Exposure to pesticides, living in a rural area, drinking well water, and having had a head injury may increase PD risk, whereas high intake of caffeine, nicotine, alcohol, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs might lower the risk.

The researchers did not take into account exposure to multiple microbes or “infection burden,” said Dr. Wagle Shukla, who was not involved in the current study. In addition, as the data are from a single country with exposure to specific influenza strains, application of the findings elsewhere may be limited.

Dr. Wagle Shukla noted that a case-control design “isn’t ideal” from an epidemiological perspective. “Future studies should involve large cohorts followed longitudinally.”

The study was supported by grants from the Lundbeck Foundation and the Augustinus Foundation. Dr. Cocoros has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Several coauthors have disclosed relationships with industry. The full list can be found with the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Influenza infection is linked to a subsequent diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease (PD) more than 10 years later, resurfacing a long-held debate about whether infection increases the risk for movement disorders over the long term.

In a large case-control study, investigators found and by more than 70% for PD occurring more than 10 years after the flu.

“This study is not definitive by any means, but it certainly suggests there are potential long-term consequences from influenza,” study investigator Noelle M. Cocoros, DSc, research scientist at Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute and Harvard Medical School, Boston, said in an interview.

The study was published online Oct. 25 in JAMA Neurology.

Ongoing debate

The debate about whether influenza is associated with PD has been going on as far back as the 1918 influenza pandemic, when experts documented parkinsonism in affected individuals.

Using data from the Danish patient registry, researchers identified 10,271 subjects diagnosed with PD during a 17-year period (2000-2016). Of these, 38.7% were female, and the mean age was 71.4 years.

They matched these subjects for age and sex to 51,355 controls without PD. Compared with controls, slightly fewer individuals with PD had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or emphysema, but there was a similar distribution of cardiovascular disease and various other conditions.

Researchers collected data on influenza diagnoses from inpatient and outpatient hospital clinics from 1977 to 2016. They plotted these by month and year on a graph, calculated the median number of diagnoses per month, and identified peaks as those with more than threefold the median.

They categorized cases in groups related to the time between the infection and PD: More than 10 years, 10-15 years, and more than 15 years.

The time lapse accounts for a rather long “run-up” to PD, said Dr. Cocoros. There’s a sometimes decades-long preclinical phase before patients develop typical motor signs and a prodromal phase where they may present with nonmotor symptoms such as sleep disorders and constipation.

“We expected there would be at least 10 years between any infection and PD if there was an association present,” said Dr. Cocoros.

Investigators found an association between influenza exposure and PD diagnosis “that held up over time,” she said.

For more than 10 years before PD, the likelihood of a diagnosis for the infected compared with the unexposed was increased 73% (odds ratio [OR] 1.73; 95% confidence interval, 1.11-2.71; P = .02) after adjustment for cardiovascular disease, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, emphysema, lung cancer, Crohn’s disease, and ulcerative colitis.

The odds increased with more time from infection. For more than 15 years, the adjusted OR was 1.91 (95% CI, 1.14 - 3.19; P =.01).

However, for the 10- to 15-year time frame, the point estimate was reduced and the CI nonsignificant (OR, 1.33; 95% CI, 0.54-3.27; P = .53). This “is a little hard to interpret,” but could be a result of the small numbers, exposure misclassification, or because “the longer time interval is what’s meaningful,” said Dr. Cocoros.

Potential COVID-19–related PD surge?

In a sensitivity analysis, researchers looked at peak infection activity. “We wanted to increase the likelihood of these diagnoses representing actual infection,” Dr. Cocoros noted.

Here, the OR was still elevated at more than 10 years, but the CI was quite wide and included 1 (OR, 1.52; 95% CI, 0.80-2.89; P = .21). “So the association holds up, but the estimates are quite unstable,” said Dr. Cocoros.

Researchers examined associations with numerous other infection types, but did not see the same trend over time. Some infections – for example, gastrointestinal infections and septicemia – were associated with PD within 5 years, but most associations appeared to be null after more than 10 years.

“There seemed to be associations earlier between the infection and PD, which we interpret to suggest there’s actually not a meaningful association,” said Dr. Cocoros.

An exception might be urinary tract infections (UTIs), where after 10 years, the adjusted OR was 1.19 (95% CI, 1.01-1.40). Research suggests patients with PD often have UTIs and neurogenic bladder.

“It’s possible that UTIs could be an early symptom of PD rather than a causative factor,” said Dr. Cocoros.

It’s unclear how influenza might lead to PD but it could be that the virus gets into the central nervous system, resulting in neuroinflammation. Cytokines generated in response to the influenza infection might damage the brain.

“The infection could be a ‘primer’ or an initial ‘hit’ to the system, maybe setting people up for PD,” said Dr. Cocoros.

As for the current COVID-19 pandemic, some experts are concerned about a potential surge in PD cases in decades to come, and are calling for prospective monitoring of patients with this infection, said Dr. Cocoros.

However, she noted that infections don’t account for all PD cases and that genetic and environmental factors also influence risk.

Many individuals who contract influenza don’t seek medical care or get tested, so it’s possible the study counted those who had the infection as unexposed. Another potential study limitation was that small numbers for some infections, for example, Helicobacter pylori and hepatitis C, limited the ability to interpret results.

‘Exciting and important’ findings

Commenting on the research for this news organization, Aparna Wagle Shukla, MD, professor, Norman Fixel Institute for Neurological Diseases, University of Florida, Gainesville, said the results amid the current pandemic are “exciting and important” and “have reinvigorated interest” in the role of infection in PD.

However, the study had some limitations, an important one being lack of accounting for confounding factors, including environmental factors, she said. Exposure to pesticides, living in a rural area, drinking well water, and having had a head injury may increase PD risk, whereas high intake of caffeine, nicotine, alcohol, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs might lower the risk.

The researchers did not take into account exposure to multiple microbes or “infection burden,” said Dr. Wagle Shukla, who was not involved in the current study. In addition, as the data are from a single country with exposure to specific influenza strains, application of the findings elsewhere may be limited.

Dr. Wagle Shukla noted that a case-control design “isn’t ideal” from an epidemiological perspective. “Future studies should involve large cohorts followed longitudinally.”

The study was supported by grants from the Lundbeck Foundation and the Augustinus Foundation. Dr. Cocoros has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Several coauthors have disclosed relationships with industry. The full list can be found with the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Influenza infection is linked to a subsequent diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease (PD) more than 10 years later, resurfacing a long-held debate about whether infection increases the risk for movement disorders over the long term.

In a large case-control study, investigators found and by more than 70% for PD occurring more than 10 years after the flu.

“This study is not definitive by any means, but it certainly suggests there are potential long-term consequences from influenza,” study investigator Noelle M. Cocoros, DSc, research scientist at Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute and Harvard Medical School, Boston, said in an interview.

The study was published online Oct. 25 in JAMA Neurology.

Ongoing debate

The debate about whether influenza is associated with PD has been going on as far back as the 1918 influenza pandemic, when experts documented parkinsonism in affected individuals.

Using data from the Danish patient registry, researchers identified 10,271 subjects diagnosed with PD during a 17-year period (2000-2016). Of these, 38.7% were female, and the mean age was 71.4 years.

They matched these subjects for age and sex to 51,355 controls without PD. Compared with controls, slightly fewer individuals with PD had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or emphysema, but there was a similar distribution of cardiovascular disease and various other conditions.

Researchers collected data on influenza diagnoses from inpatient and outpatient hospital clinics from 1977 to 2016. They plotted these by month and year on a graph, calculated the median number of diagnoses per month, and identified peaks as those with more than threefold the median.

They categorized cases in groups related to the time between the infection and PD: More than 10 years, 10-15 years, and more than 15 years.

The time lapse accounts for a rather long “run-up” to PD, said Dr. Cocoros. There’s a sometimes decades-long preclinical phase before patients develop typical motor signs and a prodromal phase where they may present with nonmotor symptoms such as sleep disorders and constipation.

“We expected there would be at least 10 years between any infection and PD if there was an association present,” said Dr. Cocoros.

Investigators found an association between influenza exposure and PD diagnosis “that held up over time,” she said.

For more than 10 years before PD, the likelihood of a diagnosis for the infected compared with the unexposed was increased 73% (odds ratio [OR] 1.73; 95% confidence interval, 1.11-2.71; P = .02) after adjustment for cardiovascular disease, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, emphysema, lung cancer, Crohn’s disease, and ulcerative colitis.

The odds increased with more time from infection. For more than 15 years, the adjusted OR was 1.91 (95% CI, 1.14 - 3.19; P =.01).

However, for the 10- to 15-year time frame, the point estimate was reduced and the CI nonsignificant (OR, 1.33; 95% CI, 0.54-3.27; P = .53). This “is a little hard to interpret,” but could be a result of the small numbers, exposure misclassification, or because “the longer time interval is what’s meaningful,” said Dr. Cocoros.

Potential COVID-19–related PD surge?

In a sensitivity analysis, researchers looked at peak infection activity. “We wanted to increase the likelihood of these diagnoses representing actual infection,” Dr. Cocoros noted.

Here, the OR was still elevated at more than 10 years, but the CI was quite wide and included 1 (OR, 1.52; 95% CI, 0.80-2.89; P = .21). “So the association holds up, but the estimates are quite unstable,” said Dr. Cocoros.

Researchers examined associations with numerous other infection types, but did not see the same trend over time. Some infections – for example, gastrointestinal infections and septicemia – were associated with PD within 5 years, but most associations appeared to be null after more than 10 years.

“There seemed to be associations earlier between the infection and PD, which we interpret to suggest there’s actually not a meaningful association,” said Dr. Cocoros.

An exception might be urinary tract infections (UTIs), where after 10 years, the adjusted OR was 1.19 (95% CI, 1.01-1.40). Research suggests patients with PD often have UTIs and neurogenic bladder.

“It’s possible that UTIs could be an early symptom of PD rather than a causative factor,” said Dr. Cocoros.

It’s unclear how influenza might lead to PD but it could be that the virus gets into the central nervous system, resulting in neuroinflammation. Cytokines generated in response to the influenza infection might damage the brain.

“The infection could be a ‘primer’ or an initial ‘hit’ to the system, maybe setting people up for PD,” said Dr. Cocoros.

As for the current COVID-19 pandemic, some experts are concerned about a potential surge in PD cases in decades to come, and are calling for prospective monitoring of patients with this infection, said Dr. Cocoros.

However, she noted that infections don’t account for all PD cases and that genetic and environmental factors also influence risk.

Many individuals who contract influenza don’t seek medical care or get tested, so it’s possible the study counted those who had the infection as unexposed. Another potential study limitation was that small numbers for some infections, for example, Helicobacter pylori and hepatitis C, limited the ability to interpret results.

‘Exciting and important’ findings

Commenting on the research for this news organization, Aparna Wagle Shukla, MD, professor, Norman Fixel Institute for Neurological Diseases, University of Florida, Gainesville, said the results amid the current pandemic are “exciting and important” and “have reinvigorated interest” in the role of infection in PD.

However, the study had some limitations, an important one being lack of accounting for confounding factors, including environmental factors, she said. Exposure to pesticides, living in a rural area, drinking well water, and having had a head injury may increase PD risk, whereas high intake of caffeine, nicotine, alcohol, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs might lower the risk.

The researchers did not take into account exposure to multiple microbes or “infection burden,” said Dr. Wagle Shukla, who was not involved in the current study. In addition, as the data are from a single country with exposure to specific influenza strains, application of the findings elsewhere may be limited.

Dr. Wagle Shukla noted that a case-control design “isn’t ideal” from an epidemiological perspective. “Future studies should involve large cohorts followed longitudinally.”

The study was supported by grants from the Lundbeck Foundation and the Augustinus Foundation. Dr. Cocoros has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Several coauthors have disclosed relationships with industry. The full list can be found with the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Art therapy linked to slowed Parkinson’s progression

Adding art therapy to standard drug treatment in Parkinson’s disease (PD) not only improves severity of both motor and nonmotor symptoms, but also slows rates of disease progression, new research suggests.

Fifty PD patients were randomly assigned to receive either art therapy, including sculpting and drawing, plus drug therapy or drug therapy alone, and followed up over 12 months.

Patients receiving combined therapy experienced improvements in symptoms, depression, and cognitive scores, and had reduced tremor and daytime sleepiness. They were also substantially less likely to experience disease progression.

“The use of art therapy can reduce the severity of motor and nonmotor manifestations of Parkinson’s disease,” said study investigator Iryna Khubetova, MD, PhD, head of the neurology department, Odessa (Ukraine) Regional Clinical Hospital.

she added.

The findings were presented at the virtual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

A promising approach

Dr. Khubetova told this news organization that offering art therapy to PD patients was “very affordable,” especially as professional artists “provided materials for painting and other art supplies free of charge.”

“We hope this approach is very promising and would be widely adopted.”

She suggested the positive effect of art therapy could be related to “activating the brain’s reward neural network.”

This may be via improved visual attention acting on visuospatial mechanisms and emotional drive, with “activation of the medial orbitofrontal cortex, ventral striatum, and other structures.”

The researchers note PD, a “multisystem progressive neurodegenerative disease,” is among the three most common neurological disorders, with an incidence of 100-150 cases per 100,000 people.

They also note that nonpharmacologic approaches are “widely used” as an adjunct to drug therapy and as part of an “integrated approach” to disease management.

To examine the clinical efficacy of art therapy, the team recruited patients with PD who had preserved facility for independent movement, defined as stages 1-2.5 on the Hoehn and Yahr scale.

Patients were randomly assigned to art therapy sessions alongside standard drug therapy or to standard drug therapy alone. The art therapy included sculpting, free drawing, and coloring patterns.

Multiple benefits

Participants were assessed at baseline and at 6 and 12 months with the Unified Parkinson Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS), the Beck Depression Inventory, the Montreal Cognitive Assessment, and the Pegboard Test of finger dexterity.

Fifty patients were included in the study, with 30 assigned to standard drug therapy alone and 20 to the combined intervention. Participants had a mean age of 57.8 years, and 46% were women.

Over the study period, investigators found patients assigned to art therapy plus drug treatment had improved mood, as well as decreased daytime sleeping, reduced tremor, and a decrease in anxiety and fear intensity.

Between baseline and the 6- and 12-month assessments, patients in the combined therapy group showed improvements in scores on all of the questionnaires, and on the Pegboard Test. In contrast, scores were either stable or worsened in the standard drug therapy–alone group.

The team notes that there was also a marked difference in rates of disease progression, defined as a change on the Hoehn and Yahr scale of at least 0.5 points, between the two groups.

Only two (10%) patients in the combined drug and art therapy progressed over the study period, compared with 10 (33%) in the control group (P = .05).

The findings complement those of a recent study conducted by Alberto Cucca, MD, of the Fresco Institute for Parkinson’s and Movement Disorders, New York University, and colleagues.

Eighteen patients took part in the prospective, open-label trial. They were assessed before and after 20 sessions of art therapy on a range of measures.

Results revealed that following the art therapy, patients had improvements in the Navon Test (which assesses visual neglect, eye tracking, and UPDRS scores), as well as significantly increased functional connectivity levels in the visual cortex on resting-state functional MRI.

Many benefits, no side effects

Rebecca Gilbert, MD, PhD, vice president and chief scientific officer of the American Parkinson Disease Association, who was not involved in either study, told this news organization that the idea of art therapy for patients with Parkinson’s is “very reasonable.”

She highlighted that “people with Parkinson’s have many issues with their visuospatial abilities,” as well as their depth and distance perception, and so “enhancing that aspect could potentially be very beneficial.”

“So I’m hopeful that it’s a really good avenue to explore, and the preliminary data are very exciting.”

Dr. Gilbert also highlighted that the “wonderful” aspect of art therapy is that there are “so many benefits and not really any side effects.” Patients can “take the meds … and then enhance that with various therapies, and this would be an additional option.”

Another notable aspect of art therapy is the “social element” and the sense of “camaraderie,” although that has “to be teased out from the benefits you would get from the actual art therapy.”

Finally, Dr. Gilbert pointed out that the difference between the current trial and Dr. Cucca’s trial is the presence of a control group.

“Of course, it’s not blinded, because you know whether you got therapy or not … but that extra element of being able to compare with a group that didn’t get the treatment gives it a little more weight in terms of the field.”

No funding was declared. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Adding art therapy to standard drug treatment in Parkinson’s disease (PD) not only improves severity of both motor and nonmotor symptoms, but also slows rates of disease progression, new research suggests.

Fifty PD patients were randomly assigned to receive either art therapy, including sculpting and drawing, plus drug therapy or drug therapy alone, and followed up over 12 months.

Patients receiving combined therapy experienced improvements in symptoms, depression, and cognitive scores, and had reduced tremor and daytime sleepiness. They were also substantially less likely to experience disease progression.

“The use of art therapy can reduce the severity of motor and nonmotor manifestations of Parkinson’s disease,” said study investigator Iryna Khubetova, MD, PhD, head of the neurology department, Odessa (Ukraine) Regional Clinical Hospital.

she added.

The findings were presented at the virtual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

A promising approach

Dr. Khubetova told this news organization that offering art therapy to PD patients was “very affordable,” especially as professional artists “provided materials for painting and other art supplies free of charge.”

“We hope this approach is very promising and would be widely adopted.”

She suggested the positive effect of art therapy could be related to “activating the brain’s reward neural network.”

This may be via improved visual attention acting on visuospatial mechanisms and emotional drive, with “activation of the medial orbitofrontal cortex, ventral striatum, and other structures.”

The researchers note PD, a “multisystem progressive neurodegenerative disease,” is among the three most common neurological disorders, with an incidence of 100-150 cases per 100,000 people.

They also note that nonpharmacologic approaches are “widely used” as an adjunct to drug therapy and as part of an “integrated approach” to disease management.

To examine the clinical efficacy of art therapy, the team recruited patients with PD who had preserved facility for independent movement, defined as stages 1-2.5 on the Hoehn and Yahr scale.

Patients were randomly assigned to art therapy sessions alongside standard drug therapy or to standard drug therapy alone. The art therapy included sculpting, free drawing, and coloring patterns.

Multiple benefits

Participants were assessed at baseline and at 6 and 12 months with the Unified Parkinson Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS), the Beck Depression Inventory, the Montreal Cognitive Assessment, and the Pegboard Test of finger dexterity.

Fifty patients were included in the study, with 30 assigned to standard drug therapy alone and 20 to the combined intervention. Participants had a mean age of 57.8 years, and 46% were women.

Over the study period, investigators found patients assigned to art therapy plus drug treatment had improved mood, as well as decreased daytime sleeping, reduced tremor, and a decrease in anxiety and fear intensity.

Between baseline and the 6- and 12-month assessments, patients in the combined therapy group showed improvements in scores on all of the questionnaires, and on the Pegboard Test. In contrast, scores were either stable or worsened in the standard drug therapy–alone group.

The team notes that there was also a marked difference in rates of disease progression, defined as a change on the Hoehn and Yahr scale of at least 0.5 points, between the two groups.

Only two (10%) patients in the combined drug and art therapy progressed over the study period, compared with 10 (33%) in the control group (P = .05).

The findings complement those of a recent study conducted by Alberto Cucca, MD, of the Fresco Institute for Parkinson’s and Movement Disorders, New York University, and colleagues.

Eighteen patients took part in the prospective, open-label trial. They were assessed before and after 20 sessions of art therapy on a range of measures.

Results revealed that following the art therapy, patients had improvements in the Navon Test (which assesses visual neglect, eye tracking, and UPDRS scores), as well as significantly increased functional connectivity levels in the visual cortex on resting-state functional MRI.

Many benefits, no side effects

Rebecca Gilbert, MD, PhD, vice president and chief scientific officer of the American Parkinson Disease Association, who was not involved in either study, told this news organization that the idea of art therapy for patients with Parkinson’s is “very reasonable.”

She highlighted that “people with Parkinson’s have many issues with their visuospatial abilities,” as well as their depth and distance perception, and so “enhancing that aspect could potentially be very beneficial.”

“So I’m hopeful that it’s a really good avenue to explore, and the preliminary data are very exciting.”

Dr. Gilbert also highlighted that the “wonderful” aspect of art therapy is that there are “so many benefits and not really any side effects.” Patients can “take the meds … and then enhance that with various therapies, and this would be an additional option.”

Another notable aspect of art therapy is the “social element” and the sense of “camaraderie,” although that has “to be teased out from the benefits you would get from the actual art therapy.”

Finally, Dr. Gilbert pointed out that the difference between the current trial and Dr. Cucca’s trial is the presence of a control group.

“Of course, it’s not blinded, because you know whether you got therapy or not … but that extra element of being able to compare with a group that didn’t get the treatment gives it a little more weight in terms of the field.”

No funding was declared. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Adding art therapy to standard drug treatment in Parkinson’s disease (PD) not only improves severity of both motor and nonmotor symptoms, but also slows rates of disease progression, new research suggests.

Fifty PD patients were randomly assigned to receive either art therapy, including sculpting and drawing, plus drug therapy or drug therapy alone, and followed up over 12 months.

Patients receiving combined therapy experienced improvements in symptoms, depression, and cognitive scores, and had reduced tremor and daytime sleepiness. They were also substantially less likely to experience disease progression.

“The use of art therapy can reduce the severity of motor and nonmotor manifestations of Parkinson’s disease,” said study investigator Iryna Khubetova, MD, PhD, head of the neurology department, Odessa (Ukraine) Regional Clinical Hospital.

she added.

The findings were presented at the virtual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

A promising approach

Dr. Khubetova told this news organization that offering art therapy to PD patients was “very affordable,” especially as professional artists “provided materials for painting and other art supplies free of charge.”

“We hope this approach is very promising and would be widely adopted.”

She suggested the positive effect of art therapy could be related to “activating the brain’s reward neural network.”

This may be via improved visual attention acting on visuospatial mechanisms and emotional drive, with “activation of the medial orbitofrontal cortex, ventral striatum, and other structures.”

The researchers note PD, a “multisystem progressive neurodegenerative disease,” is among the three most common neurological disorders, with an incidence of 100-150 cases per 100,000 people.

They also note that nonpharmacologic approaches are “widely used” as an adjunct to drug therapy and as part of an “integrated approach” to disease management.

To examine the clinical efficacy of art therapy, the team recruited patients with PD who had preserved facility for independent movement, defined as stages 1-2.5 on the Hoehn and Yahr scale.

Patients were randomly assigned to art therapy sessions alongside standard drug therapy or to standard drug therapy alone. The art therapy included sculpting, free drawing, and coloring patterns.

Multiple benefits

Participants were assessed at baseline and at 6 and 12 months with the Unified Parkinson Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS), the Beck Depression Inventory, the Montreal Cognitive Assessment, and the Pegboard Test of finger dexterity.

Fifty patients were included in the study, with 30 assigned to standard drug therapy alone and 20 to the combined intervention. Participants had a mean age of 57.8 years, and 46% were women.

Over the study period, investigators found patients assigned to art therapy plus drug treatment had improved mood, as well as decreased daytime sleeping, reduced tremor, and a decrease in anxiety and fear intensity.

Between baseline and the 6- and 12-month assessments, patients in the combined therapy group showed improvements in scores on all of the questionnaires, and on the Pegboard Test. In contrast, scores were either stable or worsened in the standard drug therapy–alone group.

The team notes that there was also a marked difference in rates of disease progression, defined as a change on the Hoehn and Yahr scale of at least 0.5 points, between the two groups.

Only two (10%) patients in the combined drug and art therapy progressed over the study period, compared with 10 (33%) in the control group (P = .05).

The findings complement those of a recent study conducted by Alberto Cucca, MD, of the Fresco Institute for Parkinson’s and Movement Disorders, New York University, and colleagues.

Eighteen patients took part in the prospective, open-label trial. They were assessed before and after 20 sessions of art therapy on a range of measures.

Results revealed that following the art therapy, patients had improvements in the Navon Test (which assesses visual neglect, eye tracking, and UPDRS scores), as well as significantly increased functional connectivity levels in the visual cortex on resting-state functional MRI.

Many benefits, no side effects

Rebecca Gilbert, MD, PhD, vice president and chief scientific officer of the American Parkinson Disease Association, who was not involved in either study, told this news organization that the idea of art therapy for patients with Parkinson’s is “very reasonable.”

She highlighted that “people with Parkinson’s have many issues with their visuospatial abilities,” as well as their depth and distance perception, and so “enhancing that aspect could potentially be very beneficial.”

“So I’m hopeful that it’s a really good avenue to explore, and the preliminary data are very exciting.”

Dr. Gilbert also highlighted that the “wonderful” aspect of art therapy is that there are “so many benefits and not really any side effects.” Patients can “take the meds … and then enhance that with various therapies, and this would be an additional option.”

Another notable aspect of art therapy is the “social element” and the sense of “camaraderie,” although that has “to be teased out from the benefits you would get from the actual art therapy.”

Finally, Dr. Gilbert pointed out that the difference between the current trial and Dr. Cucca’s trial is the presence of a control group.

“Of course, it’s not blinded, because you know whether you got therapy or not … but that extra element of being able to compare with a group that didn’t get the treatment gives it a little more weight in terms of the field.”

No funding was declared. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ECNP 2021

Customized brain stimulation: New hope for severe depression

Personalized deep brain stimulation (DBS) appears to rapidly and effectively improve symptoms of treatment-resistant depression, new research suggests.

In a proof-of-concept study, investigators identified specific brain activity patterns responsible for a single patient’s severe depression and customized a DBS protocol to modulate the patterns. Results showed rapid and sustained improvement in depression scores.

“This study points the way to a new paradigm that is desperately needed in psychiatry,” Andrew Krystal, PhD, Weill Institute for Neurosciences, University of California, San Francisco, said in a news release.

“ by identifying and modulating the circuit in her brain that’s uniquely associated with her symptoms,” Dr. Krystal added.

The findings were published online Oct. 4 in Nature Medicine.

Closed-loop, on-demand stimulation

The patient was a 36-year-old woman with longstanding, severe, and treatment-resistant major depressive disorder. She was unresponsive to multiple antidepressant combinations and electroconvulsive therapy.

The researchers used intracranial electrophysiology and focal electrical stimulation to identify the specific pattern of electrical brain activity that correlated with her depressed mood.

They identified the right ventral striatum – which is involved in emotion, motivation, and reward – as the stimulation site that led to consistent, sustained, and dose-dependent improvement of symptoms and served as the neural biomarker.

In addition, the investigators identified a neural activity pattern in the amygdala that predicted both the mood symptoms, symptom severity, and stimulation efficacy.

The patient was implanted with the Food and Drug Administration–approved NeuroPace RNS System. The device was placed in the right hemisphere. A single sensing lead was positioned in the amygdala and the second stimulation lead was placed in the ventral striatum.

When the sensing lead detected the activity pattern associated with depression, the other lead delivered a tiny dose (1 milliampere/1 mA) of electricity for 6 seconds, which altered the neural activity and relieved mood symptoms.

Remission achieved

Once this personalized, closed-loop therapy was fully operational, the patient’s depression score on the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) dropped from 33 before turning treatment ON to 14 at the first ON-treatment assessment carried out after 12 days of stimulation. The score dropped below 10, representing remission, several months later.

The treatment also rapidly improved symptom severity, as measured daily with Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD-6) and visual analog scales.

“Success was predicated on a clinical mapping stage before chronic device placement, a strategy that has been utilized in epilepsy to map seizure foci in a personalized manner but has not previously been performed in other neuropsychiatric conditions,” the investigators wrote.

This patient represents “one of the first examples of precision psychiatry – a treatment tailored to an individual,” the study’s lead author, Katherine Scangos, MD, also with UCSF Weill Institute, said in an interview.

She added that the treatment “was personally tailored both spatially,” meaning at the brain location, and temporally – the time it was delivered.

“This is the first time a neural biomarker has been used to automatically trigger therapeutic stimulation in depression as a successful long-term treatment,” said Dr. Scangos. However, “we have a lot of work left to do,” she added.

“This study provides proof-of-principle that we can utilize a multimodal brain mapping approach to identify a personalized depression circuit and target that circuit with successful treatment. We will need to test the approach in more patients before we can determine its efficacy,” Dr. Scangos said.

First reliable biomarker in psychiatry

In a statement from the UK nonprofit Science Media Centre, Vladimir Litvak, PhD, with the Wellcome Centre for Human Neuroimaging, University College London, said that the study is interesting, noting that it is from “one of the leading groups in the field.”

The fact that depression symptoms can be treated in some patients by electrical stimulation of the ventral striatum is not new, Dr. Litvak said. However, what is “exciting” is that the authors identified a particular neural activity pattern in the amygdala as a reliable predictor of both symptom severity and stimulation effectiveness, he noted.

“Patterns of brain activity correlated with disease symptoms when testing over a large group of patients are commonly discovered. But there are just a handful of examples of patterns that are reliable enough to be predictive on a short time scale in a single patient,” said Dr. Litvak, who was not associated with the research.

“Furthermore, to my knowledge, this is the first example of such a reliable biomarker for psychiatric symptoms. The other examples were all for neurological disorders such as Parkinson’s disease, dystonia, and epilepsy,” he added.

He cautioned that this is a single case, but “if reproduced in additional patients, it will bring at least some psychiatric conditions into the domain of brain diseases that can be characterized and diagnosed objectively rather than based on symptoms alone.”

Dr. Litvak pointed out two other critical aspects of the study: the use of exploratory recordings and stimulation to determine the most effective treatment strategy, and the use of a closed-loop device that stimulates only when detecting the amygdala biomarker.

“It is hard to say based on this single case how important these will be in the future. There is no comparison to constant stimulation that might have worked as well because the implanted device used in the study is not suitable for that,” Dr. Litvak said.

It should also be noted that implanting multiple depth electrodes at different brain sites is a “traumatic invasive procedure only reserved to date for severe cases of drug-resistant epilepsy,” he said. “Furthermore, it only allows [researchers] to test a small number of candidate sites, so it relies heavily on prior knowledge.

“Once clinicians know better what to look for, it might be possible to avoid this procedure altogether by using noninvasive methods,” such as functional MRI or EEG, to match the right treatment option to a patient, Dr. Litvak concluded.

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health, the Brain & Behavior Research Foundation, and the Ray and Dagmar Dolby Family Fund through the department of psychiatry at UCSF. Dr. Scangos has reported no relevant financial relationships. A complete list of author disclosures is available in the original article. Dr. Litvak is participating in a research funding application to search for electrophysiological biomarkers of depression symptoms using invasive recordings.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Personalized deep brain stimulation (DBS) appears to rapidly and effectively improve symptoms of treatment-resistant depression, new research suggests.

In a proof-of-concept study, investigators identified specific brain activity patterns responsible for a single patient’s severe depression and customized a DBS protocol to modulate the patterns. Results showed rapid and sustained improvement in depression scores.

“This study points the way to a new paradigm that is desperately needed in psychiatry,” Andrew Krystal, PhD, Weill Institute for Neurosciences, University of California, San Francisco, said in a news release.

“ by identifying and modulating the circuit in her brain that’s uniquely associated with her symptoms,” Dr. Krystal added.

The findings were published online Oct. 4 in Nature Medicine.

Closed-loop, on-demand stimulation

The patient was a 36-year-old woman with longstanding, severe, and treatment-resistant major depressive disorder. She was unresponsive to multiple antidepressant combinations and electroconvulsive therapy.

The researchers used intracranial electrophysiology and focal electrical stimulation to identify the specific pattern of electrical brain activity that correlated with her depressed mood.

They identified the right ventral striatum – which is involved in emotion, motivation, and reward – as the stimulation site that led to consistent, sustained, and dose-dependent improvement of symptoms and served as the neural biomarker.

In addition, the investigators identified a neural activity pattern in the amygdala that predicted both the mood symptoms, symptom severity, and stimulation efficacy.

The patient was implanted with the Food and Drug Administration–approved NeuroPace RNS System. The device was placed in the right hemisphere. A single sensing lead was positioned in the amygdala and the second stimulation lead was placed in the ventral striatum.

When the sensing lead detected the activity pattern associated with depression, the other lead delivered a tiny dose (1 milliampere/1 mA) of electricity for 6 seconds, which altered the neural activity and relieved mood symptoms.

Remission achieved

Once this personalized, closed-loop therapy was fully operational, the patient’s depression score on the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) dropped from 33 before turning treatment ON to 14 at the first ON-treatment assessment carried out after 12 days of stimulation. The score dropped below 10, representing remission, several months later.

The treatment also rapidly improved symptom severity, as measured daily with Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD-6) and visual analog scales.

“Success was predicated on a clinical mapping stage before chronic device placement, a strategy that has been utilized in epilepsy to map seizure foci in a personalized manner but has not previously been performed in other neuropsychiatric conditions,” the investigators wrote.

This patient represents “one of the first examples of precision psychiatry – a treatment tailored to an individual,” the study’s lead author, Katherine Scangos, MD, also with UCSF Weill Institute, said in an interview.

She added that the treatment “was personally tailored both spatially,” meaning at the brain location, and temporally – the time it was delivered.

“This is the first time a neural biomarker has been used to automatically trigger therapeutic stimulation in depression as a successful long-term treatment,” said Dr. Scangos. However, “we have a lot of work left to do,” she added.

“This study provides proof-of-principle that we can utilize a multimodal brain mapping approach to identify a personalized depression circuit and target that circuit with successful treatment. We will need to test the approach in more patients before we can determine its efficacy,” Dr. Scangos said.

First reliable biomarker in psychiatry

In a statement from the UK nonprofit Science Media Centre, Vladimir Litvak, PhD, with the Wellcome Centre for Human Neuroimaging, University College London, said that the study is interesting, noting that it is from “one of the leading groups in the field.”

The fact that depression symptoms can be treated in some patients by electrical stimulation of the ventral striatum is not new, Dr. Litvak said. However, what is “exciting” is that the authors identified a particular neural activity pattern in the amygdala as a reliable predictor of both symptom severity and stimulation effectiveness, he noted.

“Patterns of brain activity correlated with disease symptoms when testing over a large group of patients are commonly discovered. But there are just a handful of examples of patterns that are reliable enough to be predictive on a short time scale in a single patient,” said Dr. Litvak, who was not associated with the research.

“Furthermore, to my knowledge, this is the first example of such a reliable biomarker for psychiatric symptoms. The other examples were all for neurological disorders such as Parkinson’s disease, dystonia, and epilepsy,” he added.

He cautioned that this is a single case, but “if reproduced in additional patients, it will bring at least some psychiatric conditions into the domain of brain diseases that can be characterized and diagnosed objectively rather than based on symptoms alone.”

Dr. Litvak pointed out two other critical aspects of the study: the use of exploratory recordings and stimulation to determine the most effective treatment strategy, and the use of a closed-loop device that stimulates only when detecting the amygdala biomarker.

“It is hard to say based on this single case how important these will be in the future. There is no comparison to constant stimulation that might have worked as well because the implanted device used in the study is not suitable for that,” Dr. Litvak said.

It should also be noted that implanting multiple depth electrodes at different brain sites is a “traumatic invasive procedure only reserved to date for severe cases of drug-resistant epilepsy,” he said. “Furthermore, it only allows [researchers] to test a small number of candidate sites, so it relies heavily on prior knowledge.

“Once clinicians know better what to look for, it might be possible to avoid this procedure altogether by using noninvasive methods,” such as functional MRI or EEG, to match the right treatment option to a patient, Dr. Litvak concluded.

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health, the Brain & Behavior Research Foundation, and the Ray and Dagmar Dolby Family Fund through the department of psychiatry at UCSF. Dr. Scangos has reported no relevant financial relationships. A complete list of author disclosures is available in the original article. Dr. Litvak is participating in a research funding application to search for electrophysiological biomarkers of depression symptoms using invasive recordings.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Personalized deep brain stimulation (DBS) appears to rapidly and effectively improve symptoms of treatment-resistant depression, new research suggests.

In a proof-of-concept study, investigators identified specific brain activity patterns responsible for a single patient’s severe depression and customized a DBS protocol to modulate the patterns. Results showed rapid and sustained improvement in depression scores.

“This study points the way to a new paradigm that is desperately needed in psychiatry,” Andrew Krystal, PhD, Weill Institute for Neurosciences, University of California, San Francisco, said in a news release.

“ by identifying and modulating the circuit in her brain that’s uniquely associated with her symptoms,” Dr. Krystal added.

The findings were published online Oct. 4 in Nature Medicine.

Closed-loop, on-demand stimulation

The patient was a 36-year-old woman with longstanding, severe, and treatment-resistant major depressive disorder. She was unresponsive to multiple antidepressant combinations and electroconvulsive therapy.

The researchers used intracranial electrophysiology and focal electrical stimulation to identify the specific pattern of electrical brain activity that correlated with her depressed mood.

They identified the right ventral striatum – which is involved in emotion, motivation, and reward – as the stimulation site that led to consistent, sustained, and dose-dependent improvement of symptoms and served as the neural biomarker.

In addition, the investigators identified a neural activity pattern in the amygdala that predicted both the mood symptoms, symptom severity, and stimulation efficacy.

The patient was implanted with the Food and Drug Administration–approved NeuroPace RNS System. The device was placed in the right hemisphere. A single sensing lead was positioned in the amygdala and the second stimulation lead was placed in the ventral striatum.

When the sensing lead detected the activity pattern associated with depression, the other lead delivered a tiny dose (1 milliampere/1 mA) of electricity for 6 seconds, which altered the neural activity and relieved mood symptoms.

Remission achieved

Once this personalized, closed-loop therapy was fully operational, the patient’s depression score on the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) dropped from 33 before turning treatment ON to 14 at the first ON-treatment assessment carried out after 12 days of stimulation. The score dropped below 10, representing remission, several months later.

The treatment also rapidly improved symptom severity, as measured daily with Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD-6) and visual analog scales.

“Success was predicated on a clinical mapping stage before chronic device placement, a strategy that has been utilized in epilepsy to map seizure foci in a personalized manner but has not previously been performed in other neuropsychiatric conditions,” the investigators wrote.

This patient represents “one of the first examples of precision psychiatry – a treatment tailored to an individual,” the study’s lead author, Katherine Scangos, MD, also with UCSF Weill Institute, said in an interview.

She added that the treatment “was personally tailored both spatially,” meaning at the brain location, and temporally – the time it was delivered.

“This is the first time a neural biomarker has been used to automatically trigger therapeutic stimulation in depression as a successful long-term treatment,” said Dr. Scangos. However, “we have a lot of work left to do,” she added.

“This study provides proof-of-principle that we can utilize a multimodal brain mapping approach to identify a personalized depression circuit and target that circuit with successful treatment. We will need to test the approach in more patients before we can determine its efficacy,” Dr. Scangos said.

First reliable biomarker in psychiatry

In a statement from the UK nonprofit Science Media Centre, Vladimir Litvak, PhD, with the Wellcome Centre for Human Neuroimaging, University College London, said that the study is interesting, noting that it is from “one of the leading groups in the field.”

The fact that depression symptoms can be treated in some patients by electrical stimulation of the ventral striatum is not new, Dr. Litvak said. However, what is “exciting” is that the authors identified a particular neural activity pattern in the amygdala as a reliable predictor of both symptom severity and stimulation effectiveness, he noted.

“Patterns of brain activity correlated with disease symptoms when testing over a large group of patients are commonly discovered. But there are just a handful of examples of patterns that are reliable enough to be predictive on a short time scale in a single patient,” said Dr. Litvak, who was not associated with the research.

“Furthermore, to my knowledge, this is the first example of such a reliable biomarker for psychiatric symptoms. The other examples were all for neurological disorders such as Parkinson’s disease, dystonia, and epilepsy,” he added.

He cautioned that this is a single case, but “if reproduced in additional patients, it will bring at least some psychiatric conditions into the domain of brain diseases that can be characterized and diagnosed objectively rather than based on symptoms alone.”

Dr. Litvak pointed out two other critical aspects of the study: the use of exploratory recordings and stimulation to determine the most effective treatment strategy, and the use of a closed-loop device that stimulates only when detecting the amygdala biomarker.

“It is hard to say based on this single case how important these will be in the future. There is no comparison to constant stimulation that might have worked as well because the implanted device used in the study is not suitable for that,” Dr. Litvak said.

It should also be noted that implanting multiple depth electrodes at different brain sites is a “traumatic invasive procedure only reserved to date for severe cases of drug-resistant epilepsy,” he said. “Furthermore, it only allows [researchers] to test a small number of candidate sites, so it relies heavily on prior knowledge.

“Once clinicians know better what to look for, it might be possible to avoid this procedure altogether by using noninvasive methods,” such as functional MRI or EEG, to match the right treatment option to a patient, Dr. Litvak concluded.

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health, the Brain & Behavior Research Foundation, and the Ray and Dagmar Dolby Family Fund through the department of psychiatry at UCSF. Dr. Scangos has reported no relevant financial relationships. A complete list of author disclosures is available in the original article. Dr. Litvak is participating in a research funding application to search for electrophysiological biomarkers of depression symptoms using invasive recordings.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Worsening motor function tied to post COVID syndrome in Parkinson’s disease

, new research suggests.

Results from a small, international retrospective case study show that about half of participants with Parkinson’s disease who developed post–COVID-19 syndrome experienced a worsening of motor symptoms and that their need for anti-Parkinson’s medication increased.

“In our series of 27 patients with Parkinson’s disease, 85% developed post–COVID-19 symptoms,” said lead investigator Valentina Leta, MD, Parkinson’s Foundation Center of Excellence, Kings College Hospital, London.

The most common long-term effects were worsening of motor function and an increase in the need for daily levodopa. Other adverse effects included fatigue; cognitive disturbances, including brain fog, loss of concentration, and memory deficits; and sleep disturbances, such as insomnia, Dr. Leta said.

The findings were presented at the International Congress of Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders.

Long-term sequelae

Previous studies have documented worsening of motor and nonmotor symptoms among patients with Parkinson’s disease in the acute phase of COVID-19. Results of these studies suggest that mortality may be higher among patients with more advanced Parkinson’s disease, comorbidities, and frailty.

Dr. Leta noted that long-term sequelae with so-called long COVID have not been adequately explored, prompting the current study.

The case series included 27 patients with Parkinson’s disease in the United Kingdom, Italy, Romania, and Mexico who were also affected by COVID-19. The investigators defined post–COVID-19 syndrome as “signs and symptoms that develop during or after an infection consistent with COVID-19, continue for more than 12 weeks, and are not explained by an alternative diagnosis.”

Because some of the symptoms are also associated with Parkinson’s disease, symptoms were attributed to post–COVID-19 only if they occurred after a confirmed severe acute respiratory infection with SARS-CoV-2 or if patients experienced an acute or subacute worsening of a pre-existing symptom that had previously been stable.

Among the participants, 59.3% were men. The mean age at the time of Parkinson’s disease diagnosis was 59.0 ± 12.7 years, and the mean Parkinson’s disease duration was 9.2 ± 7.8 years. The patients were in Hoehn and Yahr stage 2.0 ± 1.0 at the time of their COVID-19 diagnosis.

Charlson Comorbidity Index score at COVID-19 diagnosis was 2.0 ± 1.5, and the levodopa equivalent daily dose (LEDD) was 1053.5 ± 842.4 mg.

Symptom worsening

“Cognitive disturbances” were defined as brain fog, concentration difficulty, or memory problems. “Peripheral neuropathy symptoms” were defined as having feelings of pins and needles or numbness.

By far, the most prevalent sequelae were worsening motor symptoms and increased need for anti-Parkinson’s medications. Each affected about half of the study cohort, the investigators noted.

Dr. Leta added the non-Parkinson’s disease-specific findings are in line with the existing literature on long COVID in the general population. The severity of COVID-19, as indicated by a history of hospitalization, did not seem to correlate with development of post–COVID-19 syndrome in patients with Parkinson’s disease.

In this series, few patients had respiratory, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, musculoskeletal, or dermatologic symptoms. Interestingly, only four patients reported a loss of taste or smell.

The investigators noted that in addition to viral illness, the stress of prolonged lockdown during the pandemic and reduced access to health care and rehabilitation programs may contribute to the burden of post–COVID-19 syndrome in patients with Parkinson’s disease.

Study limitations cited include the relatively small sample size and the lack of a control group. The researchers noted the need for larger studies to elucidate the natural history of COVID-19 among patients with Parkinson’s disease in order to raise awareness of their needs and to help develop personalized management strategies.

Meaningful addition

Commenting on the findings, Kyle Mitchell, MD, movement disorders neurologist, Duke University, Durham, N.C., said he found the study to be a meaningful addition in light of the fact that data on the challenges that patients with Parkinson’s disease may face after having COVID-19 are limited.

“What I liked about this study was there’s data from multiple countries, what looks like a diverse population of study participants, and really just addressing a question that we get asked a lot in clinic and we see a fair amount, but we don’t really know a lot about: how people with Parkinson’s disease will do during and post COVID-19 infection,” said Dr. Mitchell, who was not involved with the research.

He said the worsening of motor symptoms and the need for increased dopaminergic medication brought some questions to mind.

“Is this increase in medications permanent, or is it temporary until post-COVID resolves? Or is it truly something where they stay on a higher dose?” he asked.

Dr. Mitchell said he does not believe the worsening of symptoms is specific to COVID-19 and that he sees individuals with Parkinson’s disease who experience setbacks “from any number of infections.” These include urinary tract infections and influenza, which are associated with worsening mobility, rigidity, tremor, fatigue, and cognition.

“People with Parkinson’s disease seem to get hit harder by infections in general,” he said.

The study had no outside funding. Dr. Leta and Dr. Mitchell have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, new research suggests.

Results from a small, international retrospective case study show that about half of participants with Parkinson’s disease who developed post–COVID-19 syndrome experienced a worsening of motor symptoms and that their need for anti-Parkinson’s medication increased.

“In our series of 27 patients with Parkinson’s disease, 85% developed post–COVID-19 symptoms,” said lead investigator Valentina Leta, MD, Parkinson’s Foundation Center of Excellence, Kings College Hospital, London.

The most common long-term effects were worsening of motor function and an increase in the need for daily levodopa. Other adverse effects included fatigue; cognitive disturbances, including brain fog, loss of concentration, and memory deficits; and sleep disturbances, such as insomnia, Dr. Leta said.

The findings were presented at the International Congress of Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders.

Long-term sequelae

Previous studies have documented worsening of motor and nonmotor symptoms among patients with Parkinson’s disease in the acute phase of COVID-19. Results of these studies suggest that mortality may be higher among patients with more advanced Parkinson’s disease, comorbidities, and frailty.

Dr. Leta noted that long-term sequelae with so-called long COVID have not been adequately explored, prompting the current study.

The case series included 27 patients with Parkinson’s disease in the United Kingdom, Italy, Romania, and Mexico who were also affected by COVID-19. The investigators defined post–COVID-19 syndrome as “signs and symptoms that develop during or after an infection consistent with COVID-19, continue for more than 12 weeks, and are not explained by an alternative diagnosis.”

Because some of the symptoms are also associated with Parkinson’s disease, symptoms were attributed to post–COVID-19 only if they occurred after a confirmed severe acute respiratory infection with SARS-CoV-2 or if patients experienced an acute or subacute worsening of a pre-existing symptom that had previously been stable.

Among the participants, 59.3% were men. The mean age at the time of Parkinson’s disease diagnosis was 59.0 ± 12.7 years, and the mean Parkinson’s disease duration was 9.2 ± 7.8 years. The patients were in Hoehn and Yahr stage 2.0 ± 1.0 at the time of their COVID-19 diagnosis.

Charlson Comorbidity Index score at COVID-19 diagnosis was 2.0 ± 1.5, and the levodopa equivalent daily dose (LEDD) was 1053.5 ± 842.4 mg.

Symptom worsening

“Cognitive disturbances” were defined as brain fog, concentration difficulty, or memory problems. “Peripheral neuropathy symptoms” were defined as having feelings of pins and needles or numbness.

By far, the most prevalent sequelae were worsening motor symptoms and increased need for anti-Parkinson’s medications. Each affected about half of the study cohort, the investigators noted.

Dr. Leta added the non-Parkinson’s disease-specific findings are in line with the existing literature on long COVID in the general population. The severity of COVID-19, as indicated by a history of hospitalization, did not seem to correlate with development of post–COVID-19 syndrome in patients with Parkinson’s disease.

In this series, few patients had respiratory, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, musculoskeletal, or dermatologic symptoms. Interestingly, only four patients reported a loss of taste or smell.

The investigators noted that in addition to viral illness, the stress of prolonged lockdown during the pandemic and reduced access to health care and rehabilitation programs may contribute to the burden of post–COVID-19 syndrome in patients with Parkinson’s disease.

Study limitations cited include the relatively small sample size and the lack of a control group. The researchers noted the need for larger studies to elucidate the natural history of COVID-19 among patients with Parkinson’s disease in order to raise awareness of their needs and to help develop personalized management strategies.

Meaningful addition

Commenting on the findings, Kyle Mitchell, MD, movement disorders neurologist, Duke University, Durham, N.C., said he found the study to be a meaningful addition in light of the fact that data on the challenges that patients with Parkinson’s disease may face after having COVID-19 are limited.

“What I liked about this study was there’s data from multiple countries, what looks like a diverse population of study participants, and really just addressing a question that we get asked a lot in clinic and we see a fair amount, but we don’t really know a lot about: how people with Parkinson’s disease will do during and post COVID-19 infection,” said Dr. Mitchell, who was not involved with the research.

He said the worsening of motor symptoms and the need for increased dopaminergic medication brought some questions to mind.

“Is this increase in medications permanent, or is it temporary until post-COVID resolves? Or is it truly something where they stay on a higher dose?” he asked.

Dr. Mitchell said he does not believe the worsening of symptoms is specific to COVID-19 and that he sees individuals with Parkinson’s disease who experience setbacks “from any number of infections.” These include urinary tract infections and influenza, which are associated with worsening mobility, rigidity, tremor, fatigue, and cognition.

“People with Parkinson’s disease seem to get hit harder by infections in general,” he said.

The study had no outside funding. Dr. Leta and Dr. Mitchell have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, new research suggests.

Results from a small, international retrospective case study show that about half of participants with Parkinson’s disease who developed post–COVID-19 syndrome experienced a worsening of motor symptoms and that their need for anti-Parkinson’s medication increased.

“In our series of 27 patients with Parkinson’s disease, 85% developed post–COVID-19 symptoms,” said lead investigator Valentina Leta, MD, Parkinson’s Foundation Center of Excellence, Kings College Hospital, London.

The most common long-term effects were worsening of motor function and an increase in the need for daily levodopa. Other adverse effects included fatigue; cognitive disturbances, including brain fog, loss of concentration, and memory deficits; and sleep disturbances, such as insomnia, Dr. Leta said.

The findings were presented at the International Congress of Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders.

Long-term sequelae

Previous studies have documented worsening of motor and nonmotor symptoms among patients with Parkinson’s disease in the acute phase of COVID-19. Results of these studies suggest that mortality may be higher among patients with more advanced Parkinson’s disease, comorbidities, and frailty.

Dr. Leta noted that long-term sequelae with so-called long COVID have not been adequately explored, prompting the current study.

The case series included 27 patients with Parkinson’s disease in the United Kingdom, Italy, Romania, and Mexico who were also affected by COVID-19. The investigators defined post–COVID-19 syndrome as “signs and symptoms that develop during or after an infection consistent with COVID-19, continue for more than 12 weeks, and are not explained by an alternative diagnosis.”

Because some of the symptoms are also associated with Parkinson’s disease, symptoms were attributed to post–COVID-19 only if they occurred after a confirmed severe acute respiratory infection with SARS-CoV-2 or if patients experienced an acute or subacute worsening of a pre-existing symptom that had previously been stable.

Among the participants, 59.3% were men. The mean age at the time of Parkinson’s disease diagnosis was 59.0 ± 12.7 years, and the mean Parkinson’s disease duration was 9.2 ± 7.8 years. The patients were in Hoehn and Yahr stage 2.0 ± 1.0 at the time of their COVID-19 diagnosis.

Charlson Comorbidity Index score at COVID-19 diagnosis was 2.0 ± 1.5, and the levodopa equivalent daily dose (LEDD) was 1053.5 ± 842.4 mg.

Symptom worsening

“Cognitive disturbances” were defined as brain fog, concentration difficulty, or memory problems. “Peripheral neuropathy symptoms” were defined as having feelings of pins and needles or numbness.

By far, the most prevalent sequelae were worsening motor symptoms and increased need for anti-Parkinson’s medications. Each affected about half of the study cohort, the investigators noted.

Dr. Leta added the non-Parkinson’s disease-specific findings are in line with the existing literature on long COVID in the general population. The severity of COVID-19, as indicated by a history of hospitalization, did not seem to correlate with development of post–COVID-19 syndrome in patients with Parkinson’s disease.

In this series, few patients had respiratory, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, musculoskeletal, or dermatologic symptoms. Interestingly, only four patients reported a loss of taste or smell.

The investigators noted that in addition to viral illness, the stress of prolonged lockdown during the pandemic and reduced access to health care and rehabilitation programs may contribute to the burden of post–COVID-19 syndrome in patients with Parkinson’s disease.

Study limitations cited include the relatively small sample size and the lack of a control group. The researchers noted the need for larger studies to elucidate the natural history of COVID-19 among patients with Parkinson’s disease in order to raise awareness of their needs and to help develop personalized management strategies.

Meaningful addition

Commenting on the findings, Kyle Mitchell, MD, movement disorders neurologist, Duke University, Durham, N.C., said he found the study to be a meaningful addition in light of the fact that data on the challenges that patients with Parkinson’s disease may face after having COVID-19 are limited.

“What I liked about this study was there’s data from multiple countries, what looks like a diverse population of study participants, and really just addressing a question that we get asked a lot in clinic and we see a fair amount, but we don’t really know a lot about: how people with Parkinson’s disease will do during and post COVID-19 infection,” said Dr. Mitchell, who was not involved with the research.

He said the worsening of motor symptoms and the need for increased dopaminergic medication brought some questions to mind.

“Is this increase in medications permanent, or is it temporary until post-COVID resolves? Or is it truly something where they stay on a higher dose?” he asked.

Dr. Mitchell said he does not believe the worsening of symptoms is specific to COVID-19 and that he sees individuals with Parkinson’s disease who experience setbacks “from any number of infections.” These include urinary tract infections and influenza, which are associated with worsening mobility, rigidity, tremor, fatigue, and cognition.

“People with Parkinson’s disease seem to get hit harder by infections in general,” he said.

The study had no outside funding. Dr. Leta and Dr. Mitchell have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM MDS VIRTUAL CONGRESS 2021

Apple devices identify early Parkinson’s disease

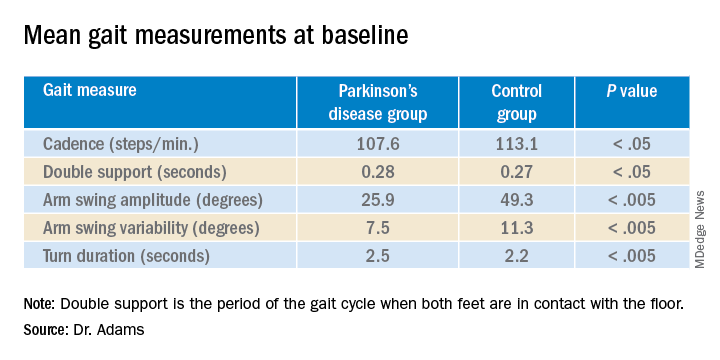

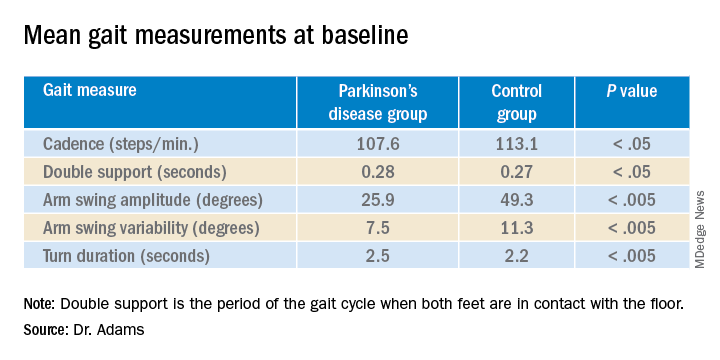

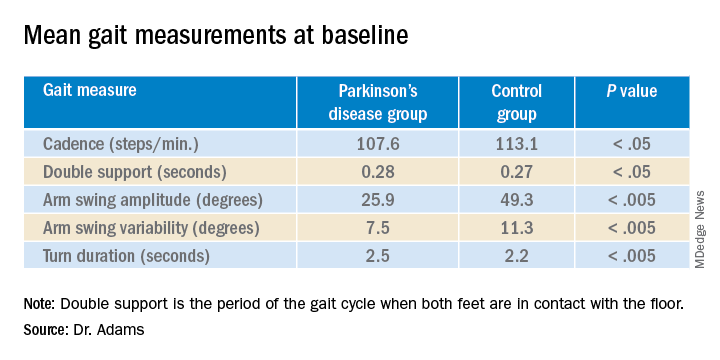

, new research shows. Results from the WATCH-PD study show clear differences in a finger-tapping task in the Parkinson’s disease versus control group. The finger-tapping task also correlated with “traditional measures,” such as the Movement Disorder Society–Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS), investigators reported.

“And then the smartphone and smartwatch also showed differences in gait between groups,” said lead investigator Jamie Adams, MD, University of Rochester, New York.

The findings were presented at the International Congress of Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders.

WATCH-PD

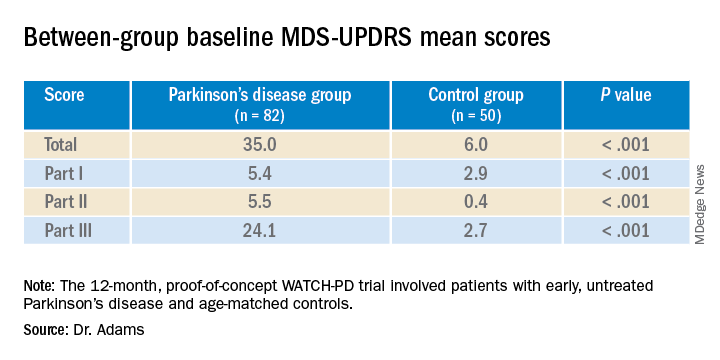

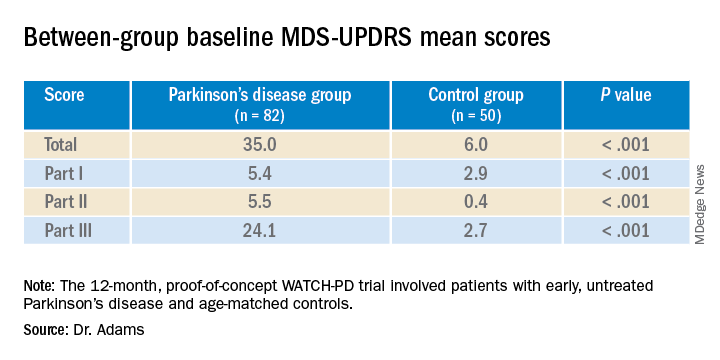

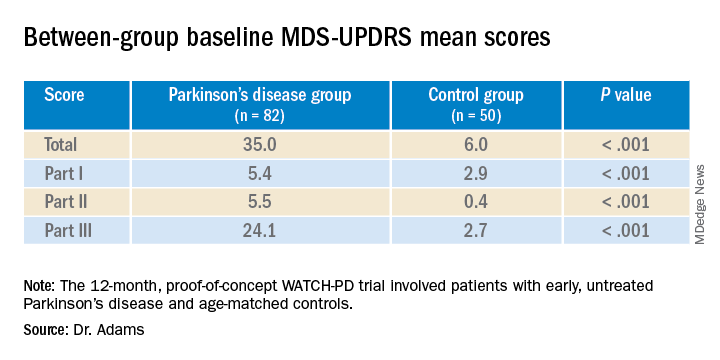

The 12-month WATCH-PD study included 132 individuals at 17 Parkinson’s Study Group sites, 82 with Parkinson’s disease and 50 controls.

Participants with Parkinson’s disease were untreated, were no more than 2 years out from diagnosis (mean disease duration, 10.0 ±7.3 months), and were in Hoehn and Yahr stage 1 or 2.

Apple Watches and iPhones were provided to participants, all of whom underwent in-clinic assessments at baseline and at months 1, 3, 6, 9, and 12. The assessments included motor and cognitive tasks using the devices, which contained motion sensors.

The phone also contained an app that could assess verbal, cognitive, and other abilities. Participants wore a set of inertial sensors (APDM Mobility Lab) while performing the MDS-UPDRS Part III motor examination.