User login

Residual symptoms of schizophrenia: What are realistic treatment goals?

The course of chronic psychiatric conditions, such as schizophrenia, differs from chronic medical conditions, such as diabetes. Some patients with chronic psychiatric conditions achieve remission and become symptom-free, while others continue to have lingering signs of disease for life.

Residual symptoms of schizophrenia are not fully defined in the literature, which poses a challenge because they are central in the overall treatment of schizophrenia spectrum disorders.1 During this phase of schizophrenia, patients continue to have symptoms after psychosis has subsided. These patients might continue to have negative symptoms such as social and emotional withdrawal and low energy. Although frank psychotic behavior has disappeared, the patient might continue to hold strange beliefs. Pharmacotherapy is the primary treatment option for psychiatric conditions, but the psychosocial aspect may have greater importance when treating residual symptoms and patients with chronic psychiatric illness.2

A naturalistic study in Germany evaluated the occurrence and characteristics of residual symptoms in patients with schizophrenia.3 The authors used a Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale symptom severity score >1 for those purposes, which is possibly a stringent criterion to define residual symptoms. This multicenter study enrolled 399 individuals age 18 to 65 with a DSM-IV-TR diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, delusional disorder, or schizoaffective disorder.3 Of the 236 patients achieving remission at discharge, 94% had at least 1 residual symptom and 69% had at least 4 residual symptoms. Therefore, residual symptoms were highly prevalent in remitted patients. The most frequent residual symptoms were:

- blunted affect

- conceptual disorganization

- passive or apathetic social withdrawal

- emotional withdrawal

- lack of judgment and insight

- poor attention

- somatic concern

- difficulty with abstract thinking

- anxiety

- poor rapport.3

Of note, positive symptoms, such as delusions and hallucinatory behavior, were found in remitted patients at discharge (17% and 10%, respectively). The study concluded that the severity of residual symptoms was associated with relapse risk and had an overall negative impact on the outcome of patients with schizophrenia.3 The study noted that residual symptoms may be greater in number or volume than negative symptoms and questioned the origins of residual symptoms because most were present at baseline in more than two-third of patients.

Patients with residual symptoms of schizophrenia usually are older and therefore present specific management challenges for clinicians. Changes associated with aging, such as medical problems, cognitive deficits, and lack of social support, could create new care needs for this patient population. Although the biopsychosocial model used to treat chronic psychiatric conditions, especially schizophrenia, is preferred, older schizophrenia patients with residual symptoms often need more psychosocial interventions compared with young adults with schizophrenia.

Managing residual symptoms in schizophrenia

Few studies are devoted to pharmacological treatment of older adults with schizophrenia, likely because pharmacotherapy for older patients with schizophrenia can be challenging. Evidence-based treatment is based primarily on findings from younger patients who survived into later life. Clinicians often use the adage of geriatric psychiatry, “start low, go slow,” because older patients are susceptible to adverse effects associated with psychiatric medications, including cardiovascular, metabolic, anticholinergic, and extrapyramidal effects, orthostasis, sedation, falls, and neuroleptic malignant syndrome.

Older patients with schizophrenia are at an increased risk for extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) and anticholinergic adverse effects, perhaps because of degeneration of dopaminergic and cholinergic neurons.4 Lowering the anticholinergic load by discontinuing or reducing the dosage of medications with anticholinergic properties, when possible, is a key principle when treating these patients. This tactic could help improve cognition and quality of life by decreasing the risk of other anticholinergic adverse effects, including delirium, constipation, urinary retention, and blurred vision.

Patients treated with typical antipsychotics are nearly twice as likely to develop tardive dyskinesia compared with those receiving atypical antipsychotics.5 Sedation, orthostatic hypotension, and anticholinergic effects can cause cognitive clouding, worsen cognitive impairment, and increase the risk of falls, especially in older patients.6 Clozapine and olanzapine have the strongest association with clinically significant weight gain and treatment-induced type 2 diabetes mellitus.7

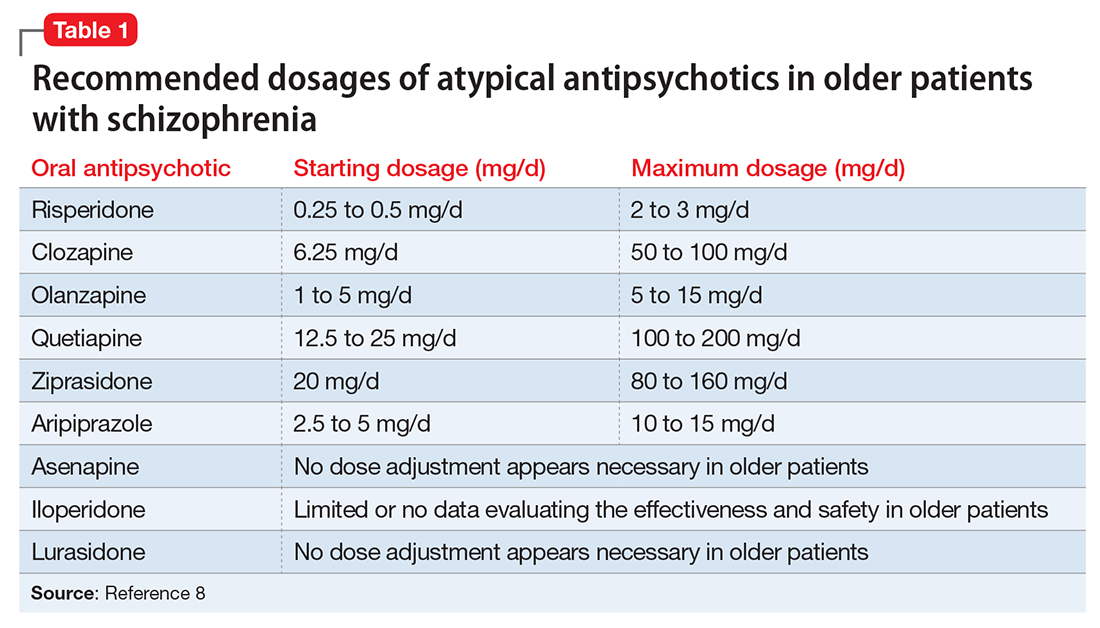

The appropriate starting dosage of antipsychotics in older patients with schizophrenia is one-fourth of the starting adult dosage. Total daily maintenance dosages may be one-third to one-half of the adult dosage.6 Consensus guidelines for dosing atypical antipsychotics for older patients with schizophrenia are as shown in Table 1.8

To ensure safety, patients should be regularly monitored with a complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, lipid panel, hemoglobin A1C, electrocardiogram, orthostatic vital signs, Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale, and weight check.7,9

When negative symptoms remain after a patient has achieved remission, it is important to evaluate whether the symptoms are related to adverse effects of medication (eg, parkinsonism syndrome), untreated depressive symptoms, or persistent positive symptoms, such as paranoia. Management of these symptoms consists of treating the cause, for example, using antipsychotics for primary positive symptoms, antidepressants for depression, anxiolytics for anxiety, and anti-parkinsonian agents or antipsychotic dosage reduction for EPS.

It is important to differentiate between negative symptoms of schizophrenia and depression in these patients. Negative symptoms of schizophrenia include affective flattening, alogia, avolition, and anhedonia. In depression, patients could have depressed mood, cognitive problems, sleep disturbances, and loss of appetite. Also, long-term symptoms are more consistent with negative symptomatology.

Keep in mind the potential for pharmacokinetic drug–drug interaction when using a combination of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), such as fluoxetine, paroxetine, and fluvoxamine (to treat negative/depressive symptoms), because all are significant inhibitors of cytochrome P450 enzymes and increase antipsychotic plasma level. The Expert Treatment Guidelines for Patients with Schizophrenia recommends SSRIs, followed by venlafaxine then bupropion to treat depressive symptoms after optimizing second-generation antipsychotics.9

Another point to consider when treating residual symptoms in patients with schizophrenia is to not discontinue antipsychotic medications. Relapse rates for these patients can occur up to 5 times higher than for those who continue treatment.10 A way to address this problem could be the use of depot antipsychotic medications, but there are no set recommendations for the use of long-acting injectable antipsychotics in older patients. These medications should be used with caution and at lowest effective dosages to offset potential adverse effects.

With the introduction of typical and atypical antipsychotics, the use of electroconvulsive therapy in older patients with schizophrenia has declined. In a 2009 meta-analysis of studies that included patients with refractory schizophrenia and repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS), results revealed a mixed effect size for controlled and uncontrolled studies. The authors stated the need for further controlled trials, assessing the efficacy of rTMS on negative and positive symptoms of schizophrenia.11

Psychotherapy and psychosocial interventions

Patients with schizophrenia who have persistent psychotic symptoms while receiving adequate pharmacotherapy should be offered adjunctive cognitive, behaviorally oriented psychotherapy to reduce symptom severity. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) has been shown to help reduce relapse rates, reduce psychotic symptoms, and improve patients’ mental state.12 Amotivation and lack of insight can be particularly troublesome, which CBT can help address.12 Psychoeducation can:

- empower patients to understand their illness

- help them cope with their disease

- be aware of symptom relapse

- seek help sooner rather than later.

Also, counseling and supportive therapy are recommended by the American Psychiatric Association guidelines. Providers should involve family and loved ones in this discussion, so that they can help collaborate with care and provide a supportive and non-judgmental environment.

Older patients with residual symptoms of schizophrenia are less likely to have completed their education, pursued a career, or developed long-lasting relationships. Family members who were their support system earlier in life, such as parents, often are unable to provide care for them by the time patients with schizophrenia become older. These patients also are less likely to get married or have children, meaning that they are more likely to live alone. The advent of the interdisciplinary team, integration of several therapeutic modalities, the provision of case managers, and assertive community treatment (ACT) teams has provided help with social support, relapses, and hospitalizations, for older patients with schizophrenia.13 Key elements of ACT include:

- a multidisciplinary team, including a medication prescriber

- a shared caseload among team members

- direct service provision by team members

- frequent patient contact

- low patient to staff ratios

- outreach to patients in the community.

Medical care

Patients with schizophrenia are at higher risk for several comorbid medical conditions, such as diabetes, coronary artery disease, and digestive and liver disorders, compared with individuals without schizophrenia. This risk is associated with numerous factors, including sedentary lifestyle, high rates of lifetime cigarette use (70% to 80% of schizophrenia outpatients age <67 smoke), poor self-management skills, frequent homelessness, and unhealthy diet.

Although substantial attention is devoted to the psychiatric and behavioral management of patients with schizophrenia, many barriers impede the detection and treatment of their medical conditions. Patients with schizophrenia could experience delays in diagnosing a medical disorder, leading to more acute comorbidities at the time of diagnosis and premature mortality. Studies have confirmed that cardiovascular diseases are the leading cause of premature death among psychiatric patients in the United States.14 Key risk factors include smoking, obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, and lack of physical activity, all of which are more common among patients with schizophrenia compared with the general population.15 In addition, antipsychotics are associated with adverse metabolic effects.16

What are realistic treatment goals to manage residual symptoms in schizophrenia?

We believe that because remission in schizophrenia has been defined consensually, the bar for treatment expectations is set higher than it was 20 years ago. There can be patient-, family-, and system-related variables affecting the feasibility of treating residual symptoms. Providers who treat patients with schizophrenia should consider the following treatment goals:

- Prevent relapse and acute psychiatric hospitalization

- Use evidence-based strategies to minimize or monitor adverse effects

- Monitor compliance and consider use of depot antipsychotics combined with patients’ preference

- Facilitate ongoing safety assessment, including suicide risk

- Monitor negative and cognitive symptoms in addition to positive symptoms, using evidence-based management

- Encourage collaboration of care with family, caretakers, and other members of the treatment team

- Empower patients by providing psychoeducation and social skills training and assisting in their vocational rehabilitation

- Educate the patient and family about healthy lifestyle interventions and medical comorbidities common with schizophrenia

- Perform baseline screening and follow-up for early detection and treatment of medical comorbidities in patients with schizophrenia

- Improve functional status and quality of life.

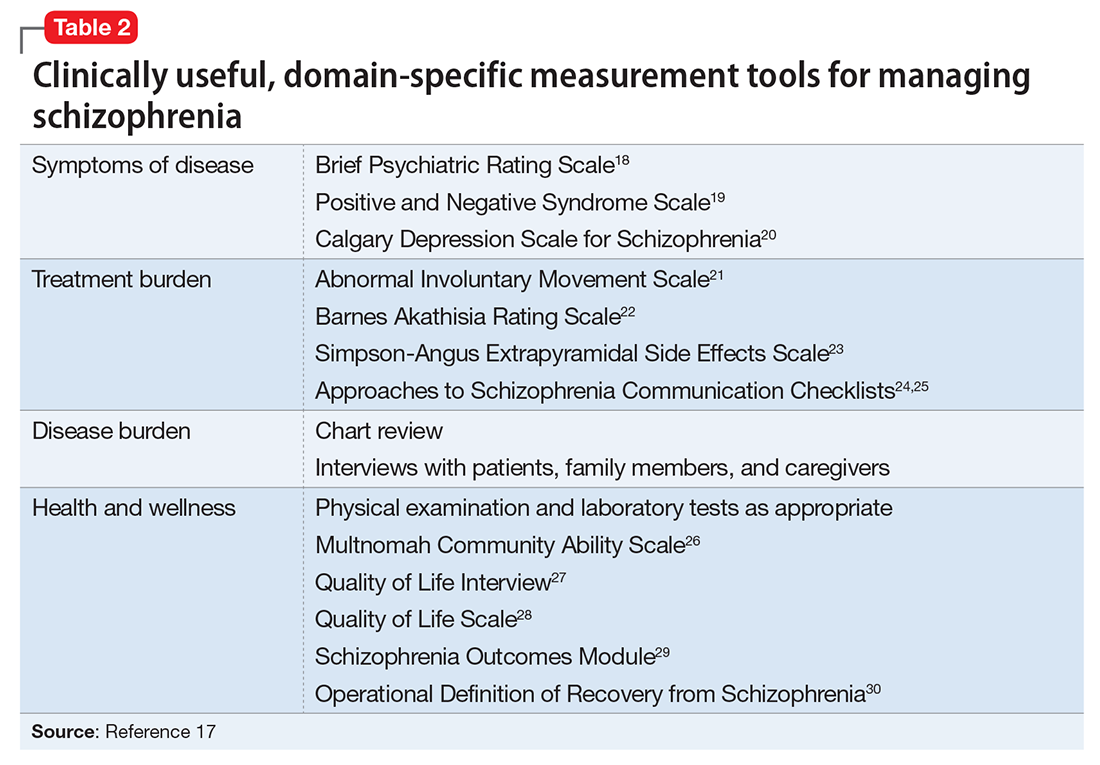

In addition to meeting these treatment goals, a measurement-based method can be implemented to monitor improvement and status of the independent treatment domains. A collection of rating instruments can be found in Table 2.17-30

The clinical presentation of patients with residual symptoms of schizophrenia differs from that of other patients with schizophrenia. Our understanding of residual symptoms in schizophrenia has come a long way in the last decade; however, we are still far from pinning the complex nature of these symptoms, let alone their management. Given the risk of morbidity and disability, there clearly is a need for further investigation and investment of time and resources to support developing novel pharmacological treatment options to manage residual symptoms in patients with schizophrenia.

Because patients with residual symptoms of schizophrenia usually are older, psychiatrists should be responsible for implementing necessary screening assessments and should closely collaborate with primary care practitioners and other specialists, and when necessary, treat comorbid medical conditions. The importance of educating patients, their families, and the treatment team cannot be overlooked. Further, psychiatric treatment facilities should offer and promote healthy lifestyle interventions.

1. Kaiser S, Lyne J, Agartz I, et al. Individual negative symptoms and domains - relevance for assessment, pathomechanisms and treatment [published online July 21, 2016]. Schizophr Res. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2016.07.013.

2. Taylor M, Chaudhry I, Cross M, et al. Towards consensus in the long-term management of relapse prevention in schizophrenia. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2005;20(3):175-181.

3. Schennach R, Riedel M, Obermeier M, et al. What are residual symptoms in schizophrenia spectrum disorder? Clinical description and 1-year persistence within a naturalistic trial. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2015;265(2):107-116.

4. Caligiuri MP, Jeste DV, Lacro JP. Antipsychotic-induced movement disorders in the elderly: epidemiology and treatment recommendations. Drugs Aging. 2000;17(5):363-384.

5. Dolder CR, Jeste DV. Incidence of tardive dyskinesia with typical versus atypical antipsychotics in very high risk patients. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;53(12):1142-1145.

6. Sable JA, Jeste DV. Antipsychotic treatment for late-life schizophrenia. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2002;4(4):299-306.

7. Newcomer JW. Second-generation (atypical) antipsychotics and metabolic effects: a comprehensive literature review. CNS Drugs. 2005;19(suppl 1):1-93.

8. Khan AY, Redden W, Ovais M, et al. Current concepts in the diagnosis and treatment of schizophrenia in later life. Current Geriatric Reports. 2015;4(4):290-300.

9. Alexopoulos GS, Streim J, Carpenter D, et al; Expert Consensus Panel for Using Antipsychotic Drugs in Older Patients. Using antipsychotic agents in older patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(suppl 2):5-99; discussion 100-102; quiz 103-104.

10. Robinson D, Woerner MG, Alvir JM, et al. Predictors of relapse following response from a first episode of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56(3):241-247.

11. Freitas C, Fregni F, Pascual-Leone A. Meta-analysis of the effects of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) on negative and positive symptoms in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2009;108(1-3):11-24.

12. Rector NA, Beck AT. Cognitive behavioral therapy for schizophrenia: an empirical review. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2012;200(10):832-839.

13. Stobbe J, Mulder NC, Roosenschoon BJ, et al. Assertive community treatment for elderly people with severe mental illness. BMC Psychiatry. 2010;10:84.

14. Hennekens CH, Hennekens AR, Hollar D, et al. Schizophrenia and increased risks of cardiovascular disease. Am Heart J. 2005;150(6):1115-1121.

15. Bushe CJ, Taylor M, Haukka J. Mortality in schizophrenia: a measurable clinical point. J Psychopharmacol. 2010;24(suppl 4):17-25.

16. Nasrallah HA, Meyer JM, Goff DC, et al. Low rates of treatment for hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes in schizophrenia: data from the CATIE schizophrenia trial sample at baseline. Schizophr Res. 2006;86(1-3):15-22.

17. Nasrallah HA, Targum SD, Tandon R, et al. Defining and measuring clinical effectiveness in the treatment of schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56(3):273-282.

18. Overall JE, Gorham DR. The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS): recent developments in ascertainment and scaling. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1988;24:97-99.

19. Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13(2):261-276.

20. Addington D, Addington J, Schissel B. A depression rating scale for schizophrenics. Schizophr Res. 1990;3(4):247-251.

21. Guy W. ECDEU Assessment manual for psychopharmacology revised, 1976. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare; Public Health Service; Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration; National Institute of Mental Health Psychopharmacology Research Branch, Division of Extramural Research Programs; 1976.

22. Barnes TR. A rating scale for drug-induced akathisia. Br J Psychiatry. 1989;154:672-676.

23. Simpson GM, Angus JWS. A rating scale for extrapyramidal side effects. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1970;45(212):11-19.

24. Dott SG, Weiden P, Hopwood P, et al. An innovative approach to clinical communication in schizophrenia: the Approaches to Schizophrenia Communication checklists. CNS Spectr. 2001;6(4):333-338.

25. Dott SG, Knesevich J, Miller A, et al. Using the ASC program: a training guide. J Psychiatr Pract. 2001;7(1):64-68.

26. Barker S, Barron N, McFarland BH, et al. Multnomah Community Ability Scale: user’s manual. Portland, OR: Western Mental Health Research Center, Oregon Health Sciences University; 1994.

27. Lehman AF. A quality of life interview for the chronically mentally ill. Eval Program Plann. 1988;11(1):51-62.

28. Heinrichs DW, Hanlon TE, Carpenter WT Jr. The Quality of Life Scale: an instrument for rating the schizophrenic deficit syndrome. Schizophr Bull. 1984;10(3):388-398.

29. Becker M, Diamond R, Sainfort F. A new patient focused index for measuring quality of life in persons with severe and persistent mental illness. Qual Life Res. 1993;2(4):239-251.

30. Liberman RP, Kopelowicz A, Ventura J, et al. Operational criteria and factors related to recovery from schizophrenia. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2009;14(4):256-272.

The course of chronic psychiatric conditions, such as schizophrenia, differs from chronic medical conditions, such as diabetes. Some patients with chronic psychiatric conditions achieve remission and become symptom-free, while others continue to have lingering signs of disease for life.

Residual symptoms of schizophrenia are not fully defined in the literature, which poses a challenge because they are central in the overall treatment of schizophrenia spectrum disorders.1 During this phase of schizophrenia, patients continue to have symptoms after psychosis has subsided. These patients might continue to have negative symptoms such as social and emotional withdrawal and low energy. Although frank psychotic behavior has disappeared, the patient might continue to hold strange beliefs. Pharmacotherapy is the primary treatment option for psychiatric conditions, but the psychosocial aspect may have greater importance when treating residual symptoms and patients with chronic psychiatric illness.2

A naturalistic study in Germany evaluated the occurrence and characteristics of residual symptoms in patients with schizophrenia.3 The authors used a Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale symptom severity score >1 for those purposes, which is possibly a stringent criterion to define residual symptoms. This multicenter study enrolled 399 individuals age 18 to 65 with a DSM-IV-TR diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, delusional disorder, or schizoaffective disorder.3 Of the 236 patients achieving remission at discharge, 94% had at least 1 residual symptom and 69% had at least 4 residual symptoms. Therefore, residual symptoms were highly prevalent in remitted patients. The most frequent residual symptoms were:

- blunted affect

- conceptual disorganization

- passive or apathetic social withdrawal

- emotional withdrawal

- lack of judgment and insight

- poor attention

- somatic concern

- difficulty with abstract thinking

- anxiety

- poor rapport.3

Of note, positive symptoms, such as delusions and hallucinatory behavior, were found in remitted patients at discharge (17% and 10%, respectively). The study concluded that the severity of residual symptoms was associated with relapse risk and had an overall negative impact on the outcome of patients with schizophrenia.3 The study noted that residual symptoms may be greater in number or volume than negative symptoms and questioned the origins of residual symptoms because most were present at baseline in more than two-third of patients.

Patients with residual symptoms of schizophrenia usually are older and therefore present specific management challenges for clinicians. Changes associated with aging, such as medical problems, cognitive deficits, and lack of social support, could create new care needs for this patient population. Although the biopsychosocial model used to treat chronic psychiatric conditions, especially schizophrenia, is preferred, older schizophrenia patients with residual symptoms often need more psychosocial interventions compared with young adults with schizophrenia.

Managing residual symptoms in schizophrenia

Few studies are devoted to pharmacological treatment of older adults with schizophrenia, likely because pharmacotherapy for older patients with schizophrenia can be challenging. Evidence-based treatment is based primarily on findings from younger patients who survived into later life. Clinicians often use the adage of geriatric psychiatry, “start low, go slow,” because older patients are susceptible to adverse effects associated with psychiatric medications, including cardiovascular, metabolic, anticholinergic, and extrapyramidal effects, orthostasis, sedation, falls, and neuroleptic malignant syndrome.

Older patients with schizophrenia are at an increased risk for extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) and anticholinergic adverse effects, perhaps because of degeneration of dopaminergic and cholinergic neurons.4 Lowering the anticholinergic load by discontinuing or reducing the dosage of medications with anticholinergic properties, when possible, is a key principle when treating these patients. This tactic could help improve cognition and quality of life by decreasing the risk of other anticholinergic adverse effects, including delirium, constipation, urinary retention, and blurred vision.

Patients treated with typical antipsychotics are nearly twice as likely to develop tardive dyskinesia compared with those receiving atypical antipsychotics.5 Sedation, orthostatic hypotension, and anticholinergic effects can cause cognitive clouding, worsen cognitive impairment, and increase the risk of falls, especially in older patients.6 Clozapine and olanzapine have the strongest association with clinically significant weight gain and treatment-induced type 2 diabetes mellitus.7

The appropriate starting dosage of antipsychotics in older patients with schizophrenia is one-fourth of the starting adult dosage. Total daily maintenance dosages may be one-third to one-half of the adult dosage.6 Consensus guidelines for dosing atypical antipsychotics for older patients with schizophrenia are as shown in Table 1.8

To ensure safety, patients should be regularly monitored with a complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, lipid panel, hemoglobin A1C, electrocardiogram, orthostatic vital signs, Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale, and weight check.7,9

When negative symptoms remain after a patient has achieved remission, it is important to evaluate whether the symptoms are related to adverse effects of medication (eg, parkinsonism syndrome), untreated depressive symptoms, or persistent positive symptoms, such as paranoia. Management of these symptoms consists of treating the cause, for example, using antipsychotics for primary positive symptoms, antidepressants for depression, anxiolytics for anxiety, and anti-parkinsonian agents or antipsychotic dosage reduction for EPS.

It is important to differentiate between negative symptoms of schizophrenia and depression in these patients. Negative symptoms of schizophrenia include affective flattening, alogia, avolition, and anhedonia. In depression, patients could have depressed mood, cognitive problems, sleep disturbances, and loss of appetite. Also, long-term symptoms are more consistent with negative symptomatology.

Keep in mind the potential for pharmacokinetic drug–drug interaction when using a combination of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), such as fluoxetine, paroxetine, and fluvoxamine (to treat negative/depressive symptoms), because all are significant inhibitors of cytochrome P450 enzymes and increase antipsychotic plasma level. The Expert Treatment Guidelines for Patients with Schizophrenia recommends SSRIs, followed by venlafaxine then bupropion to treat depressive symptoms after optimizing second-generation antipsychotics.9

Another point to consider when treating residual symptoms in patients with schizophrenia is to not discontinue antipsychotic medications. Relapse rates for these patients can occur up to 5 times higher than for those who continue treatment.10 A way to address this problem could be the use of depot antipsychotic medications, but there are no set recommendations for the use of long-acting injectable antipsychotics in older patients. These medications should be used with caution and at lowest effective dosages to offset potential adverse effects.

With the introduction of typical and atypical antipsychotics, the use of electroconvulsive therapy in older patients with schizophrenia has declined. In a 2009 meta-analysis of studies that included patients with refractory schizophrenia and repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS), results revealed a mixed effect size for controlled and uncontrolled studies. The authors stated the need for further controlled trials, assessing the efficacy of rTMS on negative and positive symptoms of schizophrenia.11

Psychotherapy and psychosocial interventions

Patients with schizophrenia who have persistent psychotic symptoms while receiving adequate pharmacotherapy should be offered adjunctive cognitive, behaviorally oriented psychotherapy to reduce symptom severity. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) has been shown to help reduce relapse rates, reduce psychotic symptoms, and improve patients’ mental state.12 Amotivation and lack of insight can be particularly troublesome, which CBT can help address.12 Psychoeducation can:

- empower patients to understand their illness

- help them cope with their disease

- be aware of symptom relapse

- seek help sooner rather than later.

Also, counseling and supportive therapy are recommended by the American Psychiatric Association guidelines. Providers should involve family and loved ones in this discussion, so that they can help collaborate with care and provide a supportive and non-judgmental environment.

Older patients with residual symptoms of schizophrenia are less likely to have completed their education, pursued a career, or developed long-lasting relationships. Family members who were their support system earlier in life, such as parents, often are unable to provide care for them by the time patients with schizophrenia become older. These patients also are less likely to get married or have children, meaning that they are more likely to live alone. The advent of the interdisciplinary team, integration of several therapeutic modalities, the provision of case managers, and assertive community treatment (ACT) teams has provided help with social support, relapses, and hospitalizations, for older patients with schizophrenia.13 Key elements of ACT include:

- a multidisciplinary team, including a medication prescriber

- a shared caseload among team members

- direct service provision by team members

- frequent patient contact

- low patient to staff ratios

- outreach to patients in the community.

Medical care

Patients with schizophrenia are at higher risk for several comorbid medical conditions, such as diabetes, coronary artery disease, and digestive and liver disorders, compared with individuals without schizophrenia. This risk is associated with numerous factors, including sedentary lifestyle, high rates of lifetime cigarette use (70% to 80% of schizophrenia outpatients age <67 smoke), poor self-management skills, frequent homelessness, and unhealthy diet.

Although substantial attention is devoted to the psychiatric and behavioral management of patients with schizophrenia, many barriers impede the detection and treatment of their medical conditions. Patients with schizophrenia could experience delays in diagnosing a medical disorder, leading to more acute comorbidities at the time of diagnosis and premature mortality. Studies have confirmed that cardiovascular diseases are the leading cause of premature death among psychiatric patients in the United States.14 Key risk factors include smoking, obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, and lack of physical activity, all of which are more common among patients with schizophrenia compared with the general population.15 In addition, antipsychotics are associated with adverse metabolic effects.16

What are realistic treatment goals to manage residual symptoms in schizophrenia?

We believe that because remission in schizophrenia has been defined consensually, the bar for treatment expectations is set higher than it was 20 years ago. There can be patient-, family-, and system-related variables affecting the feasibility of treating residual symptoms. Providers who treat patients with schizophrenia should consider the following treatment goals:

- Prevent relapse and acute psychiatric hospitalization

- Use evidence-based strategies to minimize or monitor adverse effects

- Monitor compliance and consider use of depot antipsychotics combined with patients’ preference

- Facilitate ongoing safety assessment, including suicide risk

- Monitor negative and cognitive symptoms in addition to positive symptoms, using evidence-based management

- Encourage collaboration of care with family, caretakers, and other members of the treatment team

- Empower patients by providing psychoeducation and social skills training and assisting in their vocational rehabilitation

- Educate the patient and family about healthy lifestyle interventions and medical comorbidities common with schizophrenia

- Perform baseline screening and follow-up for early detection and treatment of medical comorbidities in patients with schizophrenia

- Improve functional status and quality of life.

In addition to meeting these treatment goals, a measurement-based method can be implemented to monitor improvement and status of the independent treatment domains. A collection of rating instruments can be found in Table 2.17-30

The clinical presentation of patients with residual symptoms of schizophrenia differs from that of other patients with schizophrenia. Our understanding of residual symptoms in schizophrenia has come a long way in the last decade; however, we are still far from pinning the complex nature of these symptoms, let alone their management. Given the risk of morbidity and disability, there clearly is a need for further investigation and investment of time and resources to support developing novel pharmacological treatment options to manage residual symptoms in patients with schizophrenia.

Because patients with residual symptoms of schizophrenia usually are older, psychiatrists should be responsible for implementing necessary screening assessments and should closely collaborate with primary care practitioners and other specialists, and when necessary, treat comorbid medical conditions. The importance of educating patients, their families, and the treatment team cannot be overlooked. Further, psychiatric treatment facilities should offer and promote healthy lifestyle interventions.

The course of chronic psychiatric conditions, such as schizophrenia, differs from chronic medical conditions, such as diabetes. Some patients with chronic psychiatric conditions achieve remission and become symptom-free, while others continue to have lingering signs of disease for life.

Residual symptoms of schizophrenia are not fully defined in the literature, which poses a challenge because they are central in the overall treatment of schizophrenia spectrum disorders.1 During this phase of schizophrenia, patients continue to have symptoms after psychosis has subsided. These patients might continue to have negative symptoms such as social and emotional withdrawal and low energy. Although frank psychotic behavior has disappeared, the patient might continue to hold strange beliefs. Pharmacotherapy is the primary treatment option for psychiatric conditions, but the psychosocial aspect may have greater importance when treating residual symptoms and patients with chronic psychiatric illness.2

A naturalistic study in Germany evaluated the occurrence and characteristics of residual symptoms in patients with schizophrenia.3 The authors used a Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale symptom severity score >1 for those purposes, which is possibly a stringent criterion to define residual symptoms. This multicenter study enrolled 399 individuals age 18 to 65 with a DSM-IV-TR diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, delusional disorder, or schizoaffective disorder.3 Of the 236 patients achieving remission at discharge, 94% had at least 1 residual symptom and 69% had at least 4 residual symptoms. Therefore, residual symptoms were highly prevalent in remitted patients. The most frequent residual symptoms were:

- blunted affect

- conceptual disorganization

- passive or apathetic social withdrawal

- emotional withdrawal

- lack of judgment and insight

- poor attention

- somatic concern

- difficulty with abstract thinking

- anxiety

- poor rapport.3

Of note, positive symptoms, such as delusions and hallucinatory behavior, were found in remitted patients at discharge (17% and 10%, respectively). The study concluded that the severity of residual symptoms was associated with relapse risk and had an overall negative impact on the outcome of patients with schizophrenia.3 The study noted that residual symptoms may be greater in number or volume than negative symptoms and questioned the origins of residual symptoms because most were present at baseline in more than two-third of patients.

Patients with residual symptoms of schizophrenia usually are older and therefore present specific management challenges for clinicians. Changes associated with aging, such as medical problems, cognitive deficits, and lack of social support, could create new care needs for this patient population. Although the biopsychosocial model used to treat chronic psychiatric conditions, especially schizophrenia, is preferred, older schizophrenia patients with residual symptoms often need more psychosocial interventions compared with young adults with schizophrenia.

Managing residual symptoms in schizophrenia

Few studies are devoted to pharmacological treatment of older adults with schizophrenia, likely because pharmacotherapy for older patients with schizophrenia can be challenging. Evidence-based treatment is based primarily on findings from younger patients who survived into later life. Clinicians often use the adage of geriatric psychiatry, “start low, go slow,” because older patients are susceptible to adverse effects associated with psychiatric medications, including cardiovascular, metabolic, anticholinergic, and extrapyramidal effects, orthostasis, sedation, falls, and neuroleptic malignant syndrome.

Older patients with schizophrenia are at an increased risk for extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) and anticholinergic adverse effects, perhaps because of degeneration of dopaminergic and cholinergic neurons.4 Lowering the anticholinergic load by discontinuing or reducing the dosage of medications with anticholinergic properties, when possible, is a key principle when treating these patients. This tactic could help improve cognition and quality of life by decreasing the risk of other anticholinergic adverse effects, including delirium, constipation, urinary retention, and blurred vision.

Patients treated with typical antipsychotics are nearly twice as likely to develop tardive dyskinesia compared with those receiving atypical antipsychotics.5 Sedation, orthostatic hypotension, and anticholinergic effects can cause cognitive clouding, worsen cognitive impairment, and increase the risk of falls, especially in older patients.6 Clozapine and olanzapine have the strongest association with clinically significant weight gain and treatment-induced type 2 diabetes mellitus.7

The appropriate starting dosage of antipsychotics in older patients with schizophrenia is one-fourth of the starting adult dosage. Total daily maintenance dosages may be one-third to one-half of the adult dosage.6 Consensus guidelines for dosing atypical antipsychotics for older patients with schizophrenia are as shown in Table 1.8

To ensure safety, patients should be regularly monitored with a complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, lipid panel, hemoglobin A1C, electrocardiogram, orthostatic vital signs, Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale, and weight check.7,9

When negative symptoms remain after a patient has achieved remission, it is important to evaluate whether the symptoms are related to adverse effects of medication (eg, parkinsonism syndrome), untreated depressive symptoms, or persistent positive symptoms, such as paranoia. Management of these symptoms consists of treating the cause, for example, using antipsychotics for primary positive symptoms, antidepressants for depression, anxiolytics for anxiety, and anti-parkinsonian agents or antipsychotic dosage reduction for EPS.

It is important to differentiate between negative symptoms of schizophrenia and depression in these patients. Negative symptoms of schizophrenia include affective flattening, alogia, avolition, and anhedonia. In depression, patients could have depressed mood, cognitive problems, sleep disturbances, and loss of appetite. Also, long-term symptoms are more consistent with negative symptomatology.

Keep in mind the potential for pharmacokinetic drug–drug interaction when using a combination of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), such as fluoxetine, paroxetine, and fluvoxamine (to treat negative/depressive symptoms), because all are significant inhibitors of cytochrome P450 enzymes and increase antipsychotic plasma level. The Expert Treatment Guidelines for Patients with Schizophrenia recommends SSRIs, followed by venlafaxine then bupropion to treat depressive symptoms after optimizing second-generation antipsychotics.9

Another point to consider when treating residual symptoms in patients with schizophrenia is to not discontinue antipsychotic medications. Relapse rates for these patients can occur up to 5 times higher than for those who continue treatment.10 A way to address this problem could be the use of depot antipsychotic medications, but there are no set recommendations for the use of long-acting injectable antipsychotics in older patients. These medications should be used with caution and at lowest effective dosages to offset potential adverse effects.

With the introduction of typical and atypical antipsychotics, the use of electroconvulsive therapy in older patients with schizophrenia has declined. In a 2009 meta-analysis of studies that included patients with refractory schizophrenia and repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS), results revealed a mixed effect size for controlled and uncontrolled studies. The authors stated the need for further controlled trials, assessing the efficacy of rTMS on negative and positive symptoms of schizophrenia.11

Psychotherapy and psychosocial interventions

Patients with schizophrenia who have persistent psychotic symptoms while receiving adequate pharmacotherapy should be offered adjunctive cognitive, behaviorally oriented psychotherapy to reduce symptom severity. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) has been shown to help reduce relapse rates, reduce psychotic symptoms, and improve patients’ mental state.12 Amotivation and lack of insight can be particularly troublesome, which CBT can help address.12 Psychoeducation can:

- empower patients to understand their illness

- help them cope with their disease

- be aware of symptom relapse

- seek help sooner rather than later.

Also, counseling and supportive therapy are recommended by the American Psychiatric Association guidelines. Providers should involve family and loved ones in this discussion, so that they can help collaborate with care and provide a supportive and non-judgmental environment.

Older patients with residual symptoms of schizophrenia are less likely to have completed their education, pursued a career, or developed long-lasting relationships. Family members who were their support system earlier in life, such as parents, often are unable to provide care for them by the time patients with schizophrenia become older. These patients also are less likely to get married or have children, meaning that they are more likely to live alone. The advent of the interdisciplinary team, integration of several therapeutic modalities, the provision of case managers, and assertive community treatment (ACT) teams has provided help with social support, relapses, and hospitalizations, for older patients with schizophrenia.13 Key elements of ACT include:

- a multidisciplinary team, including a medication prescriber

- a shared caseload among team members

- direct service provision by team members

- frequent patient contact

- low patient to staff ratios

- outreach to patients in the community.

Medical care

Patients with schizophrenia are at higher risk for several comorbid medical conditions, such as diabetes, coronary artery disease, and digestive and liver disorders, compared with individuals without schizophrenia. This risk is associated with numerous factors, including sedentary lifestyle, high rates of lifetime cigarette use (70% to 80% of schizophrenia outpatients age <67 smoke), poor self-management skills, frequent homelessness, and unhealthy diet.

Although substantial attention is devoted to the psychiatric and behavioral management of patients with schizophrenia, many barriers impede the detection and treatment of their medical conditions. Patients with schizophrenia could experience delays in diagnosing a medical disorder, leading to more acute comorbidities at the time of diagnosis and premature mortality. Studies have confirmed that cardiovascular diseases are the leading cause of premature death among psychiatric patients in the United States.14 Key risk factors include smoking, obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, and lack of physical activity, all of which are more common among patients with schizophrenia compared with the general population.15 In addition, antipsychotics are associated with adverse metabolic effects.16

What are realistic treatment goals to manage residual symptoms in schizophrenia?

We believe that because remission in schizophrenia has been defined consensually, the bar for treatment expectations is set higher than it was 20 years ago. There can be patient-, family-, and system-related variables affecting the feasibility of treating residual symptoms. Providers who treat patients with schizophrenia should consider the following treatment goals:

- Prevent relapse and acute psychiatric hospitalization

- Use evidence-based strategies to minimize or monitor adverse effects

- Monitor compliance and consider use of depot antipsychotics combined with patients’ preference

- Facilitate ongoing safety assessment, including suicide risk

- Monitor negative and cognitive symptoms in addition to positive symptoms, using evidence-based management

- Encourage collaboration of care with family, caretakers, and other members of the treatment team

- Empower patients by providing psychoeducation and social skills training and assisting in their vocational rehabilitation

- Educate the patient and family about healthy lifestyle interventions and medical comorbidities common with schizophrenia

- Perform baseline screening and follow-up for early detection and treatment of medical comorbidities in patients with schizophrenia

- Improve functional status and quality of life.

In addition to meeting these treatment goals, a measurement-based method can be implemented to monitor improvement and status of the independent treatment domains. A collection of rating instruments can be found in Table 2.17-30

The clinical presentation of patients with residual symptoms of schizophrenia differs from that of other patients with schizophrenia. Our understanding of residual symptoms in schizophrenia has come a long way in the last decade; however, we are still far from pinning the complex nature of these symptoms, let alone their management. Given the risk of morbidity and disability, there clearly is a need for further investigation and investment of time and resources to support developing novel pharmacological treatment options to manage residual symptoms in patients with schizophrenia.

Because patients with residual symptoms of schizophrenia usually are older, psychiatrists should be responsible for implementing necessary screening assessments and should closely collaborate with primary care practitioners and other specialists, and when necessary, treat comorbid medical conditions. The importance of educating patients, their families, and the treatment team cannot be overlooked. Further, psychiatric treatment facilities should offer and promote healthy lifestyle interventions.

1. Kaiser S, Lyne J, Agartz I, et al. Individual negative symptoms and domains - relevance for assessment, pathomechanisms and treatment [published online July 21, 2016]. Schizophr Res. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2016.07.013.

2. Taylor M, Chaudhry I, Cross M, et al. Towards consensus in the long-term management of relapse prevention in schizophrenia. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2005;20(3):175-181.

3. Schennach R, Riedel M, Obermeier M, et al. What are residual symptoms in schizophrenia spectrum disorder? Clinical description and 1-year persistence within a naturalistic trial. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2015;265(2):107-116.

4. Caligiuri MP, Jeste DV, Lacro JP. Antipsychotic-induced movement disorders in the elderly: epidemiology and treatment recommendations. Drugs Aging. 2000;17(5):363-384.

5. Dolder CR, Jeste DV. Incidence of tardive dyskinesia with typical versus atypical antipsychotics in very high risk patients. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;53(12):1142-1145.

6. Sable JA, Jeste DV. Antipsychotic treatment for late-life schizophrenia. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2002;4(4):299-306.

7. Newcomer JW. Second-generation (atypical) antipsychotics and metabolic effects: a comprehensive literature review. CNS Drugs. 2005;19(suppl 1):1-93.

8. Khan AY, Redden W, Ovais M, et al. Current concepts in the diagnosis and treatment of schizophrenia in later life. Current Geriatric Reports. 2015;4(4):290-300.

9. Alexopoulos GS, Streim J, Carpenter D, et al; Expert Consensus Panel for Using Antipsychotic Drugs in Older Patients. Using antipsychotic agents in older patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(suppl 2):5-99; discussion 100-102; quiz 103-104.

10. Robinson D, Woerner MG, Alvir JM, et al. Predictors of relapse following response from a first episode of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56(3):241-247.

11. Freitas C, Fregni F, Pascual-Leone A. Meta-analysis of the effects of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) on negative and positive symptoms in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2009;108(1-3):11-24.

12. Rector NA, Beck AT. Cognitive behavioral therapy for schizophrenia: an empirical review. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2012;200(10):832-839.

13. Stobbe J, Mulder NC, Roosenschoon BJ, et al. Assertive community treatment for elderly people with severe mental illness. BMC Psychiatry. 2010;10:84.

14. Hennekens CH, Hennekens AR, Hollar D, et al. Schizophrenia and increased risks of cardiovascular disease. Am Heart J. 2005;150(6):1115-1121.

15. Bushe CJ, Taylor M, Haukka J. Mortality in schizophrenia: a measurable clinical point. J Psychopharmacol. 2010;24(suppl 4):17-25.

16. Nasrallah HA, Meyer JM, Goff DC, et al. Low rates of treatment for hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes in schizophrenia: data from the CATIE schizophrenia trial sample at baseline. Schizophr Res. 2006;86(1-3):15-22.

17. Nasrallah HA, Targum SD, Tandon R, et al. Defining and measuring clinical effectiveness in the treatment of schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56(3):273-282.

18. Overall JE, Gorham DR. The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS): recent developments in ascertainment and scaling. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1988;24:97-99.

19. Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13(2):261-276.

20. Addington D, Addington J, Schissel B. A depression rating scale for schizophrenics. Schizophr Res. 1990;3(4):247-251.

21. Guy W. ECDEU Assessment manual for psychopharmacology revised, 1976. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare; Public Health Service; Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration; National Institute of Mental Health Psychopharmacology Research Branch, Division of Extramural Research Programs; 1976.

22. Barnes TR. A rating scale for drug-induced akathisia. Br J Psychiatry. 1989;154:672-676.

23. Simpson GM, Angus JWS. A rating scale for extrapyramidal side effects. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1970;45(212):11-19.

24. Dott SG, Weiden P, Hopwood P, et al. An innovative approach to clinical communication in schizophrenia: the Approaches to Schizophrenia Communication checklists. CNS Spectr. 2001;6(4):333-338.

25. Dott SG, Knesevich J, Miller A, et al. Using the ASC program: a training guide. J Psychiatr Pract. 2001;7(1):64-68.

26. Barker S, Barron N, McFarland BH, et al. Multnomah Community Ability Scale: user’s manual. Portland, OR: Western Mental Health Research Center, Oregon Health Sciences University; 1994.

27. Lehman AF. A quality of life interview for the chronically mentally ill. Eval Program Plann. 1988;11(1):51-62.

28. Heinrichs DW, Hanlon TE, Carpenter WT Jr. The Quality of Life Scale: an instrument for rating the schizophrenic deficit syndrome. Schizophr Bull. 1984;10(3):388-398.

29. Becker M, Diamond R, Sainfort F. A new patient focused index for measuring quality of life in persons with severe and persistent mental illness. Qual Life Res. 1993;2(4):239-251.

30. Liberman RP, Kopelowicz A, Ventura J, et al. Operational criteria and factors related to recovery from schizophrenia. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2009;14(4):256-272.

1. Kaiser S, Lyne J, Agartz I, et al. Individual negative symptoms and domains - relevance for assessment, pathomechanisms and treatment [published online July 21, 2016]. Schizophr Res. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2016.07.013.

2. Taylor M, Chaudhry I, Cross M, et al. Towards consensus in the long-term management of relapse prevention in schizophrenia. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2005;20(3):175-181.

3. Schennach R, Riedel M, Obermeier M, et al. What are residual symptoms in schizophrenia spectrum disorder? Clinical description and 1-year persistence within a naturalistic trial. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2015;265(2):107-116.

4. Caligiuri MP, Jeste DV, Lacro JP. Antipsychotic-induced movement disorders in the elderly: epidemiology and treatment recommendations. Drugs Aging. 2000;17(5):363-384.

5. Dolder CR, Jeste DV. Incidence of tardive dyskinesia with typical versus atypical antipsychotics in very high risk patients. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;53(12):1142-1145.

6. Sable JA, Jeste DV. Antipsychotic treatment for late-life schizophrenia. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2002;4(4):299-306.

7. Newcomer JW. Second-generation (atypical) antipsychotics and metabolic effects: a comprehensive literature review. CNS Drugs. 2005;19(suppl 1):1-93.

8. Khan AY, Redden W, Ovais M, et al. Current concepts in the diagnosis and treatment of schizophrenia in later life. Current Geriatric Reports. 2015;4(4):290-300.

9. Alexopoulos GS, Streim J, Carpenter D, et al; Expert Consensus Panel for Using Antipsychotic Drugs in Older Patients. Using antipsychotic agents in older patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(suppl 2):5-99; discussion 100-102; quiz 103-104.

10. Robinson D, Woerner MG, Alvir JM, et al. Predictors of relapse following response from a first episode of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56(3):241-247.

11. Freitas C, Fregni F, Pascual-Leone A. Meta-analysis of the effects of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) on negative and positive symptoms in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2009;108(1-3):11-24.

12. Rector NA, Beck AT. Cognitive behavioral therapy for schizophrenia: an empirical review. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2012;200(10):832-839.

13. Stobbe J, Mulder NC, Roosenschoon BJ, et al. Assertive community treatment for elderly people with severe mental illness. BMC Psychiatry. 2010;10:84.

14. Hennekens CH, Hennekens AR, Hollar D, et al. Schizophrenia and increased risks of cardiovascular disease. Am Heart J. 2005;150(6):1115-1121.

15. Bushe CJ, Taylor M, Haukka J. Mortality in schizophrenia: a measurable clinical point. J Psychopharmacol. 2010;24(suppl 4):17-25.

16. Nasrallah HA, Meyer JM, Goff DC, et al. Low rates of treatment for hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes in schizophrenia: data from the CATIE schizophrenia trial sample at baseline. Schizophr Res. 2006;86(1-3):15-22.

17. Nasrallah HA, Targum SD, Tandon R, et al. Defining and measuring clinical effectiveness in the treatment of schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56(3):273-282.

18. Overall JE, Gorham DR. The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS): recent developments in ascertainment and scaling. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1988;24:97-99.

19. Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13(2):261-276.

20. Addington D, Addington J, Schissel B. A depression rating scale for schizophrenics. Schizophr Res. 1990;3(4):247-251.

21. Guy W. ECDEU Assessment manual for psychopharmacology revised, 1976. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare; Public Health Service; Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration; National Institute of Mental Health Psychopharmacology Research Branch, Division of Extramural Research Programs; 1976.

22. Barnes TR. A rating scale for drug-induced akathisia. Br J Psychiatry. 1989;154:672-676.

23. Simpson GM, Angus JWS. A rating scale for extrapyramidal side effects. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1970;45(212):11-19.

24. Dott SG, Weiden P, Hopwood P, et al. An innovative approach to clinical communication in schizophrenia: the Approaches to Schizophrenia Communication checklists. CNS Spectr. 2001;6(4):333-338.

25. Dott SG, Knesevich J, Miller A, et al. Using the ASC program: a training guide. J Psychiatr Pract. 2001;7(1):64-68.

26. Barker S, Barron N, McFarland BH, et al. Multnomah Community Ability Scale: user’s manual. Portland, OR: Western Mental Health Research Center, Oregon Health Sciences University; 1994.

27. Lehman AF. A quality of life interview for the chronically mentally ill. Eval Program Plann. 1988;11(1):51-62.

28. Heinrichs DW, Hanlon TE, Carpenter WT Jr. The Quality of Life Scale: an instrument for rating the schizophrenic deficit syndrome. Schizophr Bull. 1984;10(3):388-398.

29. Becker M, Diamond R, Sainfort F. A new patient focused index for measuring quality of life in persons with severe and persistent mental illness. Qual Life Res. 1993;2(4):239-251.

30. Liberman RP, Kopelowicz A, Ventura J, et al. Operational criteria and factors related to recovery from schizophrenia. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2009;14(4):256-272.