User login

Residual symptoms of schizophrenia: What are realistic treatment goals?

The course of chronic psychiatric conditions, such as schizophrenia, differs from chronic medical conditions, such as diabetes. Some patients with chronic psychiatric conditions achieve remission and become symptom-free, while others continue to have lingering signs of disease for life.

Residual symptoms of schizophrenia are not fully defined in the literature, which poses a challenge because they are central in the overall treatment of schizophrenia spectrum disorders.1 During this phase of schizophrenia, patients continue to have symptoms after psychosis has subsided. These patients might continue to have negative symptoms such as social and emotional withdrawal and low energy. Although frank psychotic behavior has disappeared, the patient might continue to hold strange beliefs. Pharmacotherapy is the primary treatment option for psychiatric conditions, but the psychosocial aspect may have greater importance when treating residual symptoms and patients with chronic psychiatric illness.2

A naturalistic study in Germany evaluated the occurrence and characteristics of residual symptoms in patients with schizophrenia.3 The authors used a Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale symptom severity score >1 for those purposes, which is possibly a stringent criterion to define residual symptoms. This multicenter study enrolled 399 individuals age 18 to 65 with a DSM-IV-TR diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, delusional disorder, or schizoaffective disorder.3 Of the 236 patients achieving remission at discharge, 94% had at least 1 residual symptom and 69% had at least 4 residual symptoms. Therefore, residual symptoms were highly prevalent in remitted patients. The most frequent residual symptoms were:

- blunted affect

- conceptual disorganization

- passive or apathetic social withdrawal

- emotional withdrawal

- lack of judgment and insight

- poor attention

- somatic concern

- difficulty with abstract thinking

- anxiety

- poor rapport.3

Of note, positive symptoms, such as delusions and hallucinatory behavior, were found in remitted patients at discharge (17% and 10%, respectively). The study concluded that the severity of residual symptoms was associated with relapse risk and had an overall negative impact on the outcome of patients with schizophrenia.3 The study noted that residual symptoms may be greater in number or volume than negative symptoms and questioned the origins of residual symptoms because most were present at baseline in more than two-third of patients.

Patients with residual symptoms of schizophrenia usually are older and therefore present specific management challenges for clinicians. Changes associated with aging, such as medical problems, cognitive deficits, and lack of social support, could create new care needs for this patient population. Although the biopsychosocial model used to treat chronic psychiatric conditions, especially schizophrenia, is preferred, older schizophrenia patients with residual symptoms often need more psychosocial interventions compared with young adults with schizophrenia.

Managing residual symptoms in schizophrenia

Few studies are devoted to pharmacological treatment of older adults with schizophrenia, likely because pharmacotherapy for older patients with schizophrenia can be challenging. Evidence-based treatment is based primarily on findings from younger patients who survived into later life. Clinicians often use the adage of geriatric psychiatry, “start low, go slow,” because older patients are susceptible to adverse effects associated with psychiatric medications, including cardiovascular, metabolic, anticholinergic, and extrapyramidal effects, orthostasis, sedation, falls, and neuroleptic malignant syndrome.

Older patients with schizophrenia are at an increased risk for extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) and anticholinergic adverse effects, perhaps because of degeneration of dopaminergic and cholinergic neurons.4 Lowering the anticholinergic load by discontinuing or reducing the dosage of medications with anticholinergic properties, when possible, is a key principle when treating these patients. This tactic could help improve cognition and quality of life by decreasing the risk of other anticholinergic adverse effects, including delirium, constipation, urinary retention, and blurred vision.

Patients treated with typical antipsychotics are nearly twice as likely to develop tardive dyskinesia compared with those receiving atypical antipsychotics.5 Sedation, orthostatic hypotension, and anticholinergic effects can cause cognitive clouding, worsen cognitive impairment, and increase the risk of falls, especially in older patients.6 Clozapine and olanzapine have the strongest association with clinically significant weight gain and treatment-induced type 2 diabetes mellitus.7

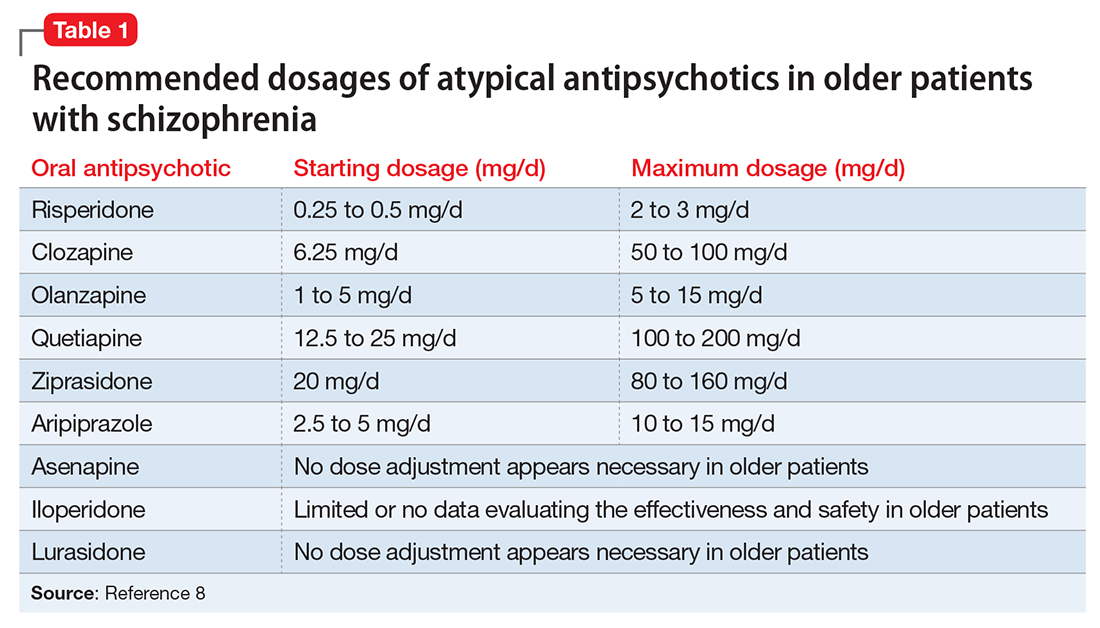

The appropriate starting dosage of antipsychotics in older patients with schizophrenia is one-fourth of the starting adult dosage. Total daily maintenance dosages may be one-third to one-half of the adult dosage.6 Consensus guidelines for dosing atypical antipsychotics for older patients with schizophrenia are as shown in Table 1.8

To ensure safety, patients should be regularly monitored with a complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, lipid panel, hemoglobin A1C, electrocardiogram, orthostatic vital signs, Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale, and weight check.7,9

When negative symptoms remain after a patient has achieved remission, it is important to evaluate whether the symptoms are related to adverse effects of medication (eg, parkinsonism syndrome), untreated depressive symptoms, or persistent positive symptoms, such as paranoia. Management of these symptoms consists of treating the cause, for example, using antipsychotics for primary positive symptoms, antidepressants for depression, anxiolytics for anxiety, and anti-parkinsonian agents or antipsychotic dosage reduction for EPS.

It is important to differentiate between negative symptoms of schizophrenia and depression in these patients. Negative symptoms of schizophrenia include affective flattening, alogia, avolition, and anhedonia. In depression, patients could have depressed mood, cognitive problems, sleep disturbances, and loss of appetite. Also, long-term symptoms are more consistent with negative symptomatology.

Keep in mind the potential for pharmacokinetic drug–drug interaction when using a combination of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), such as fluoxetine, paroxetine, and fluvoxamine (to treat negative/depressive symptoms), because all are significant inhibitors of cytochrome P450 enzymes and increase antipsychotic plasma level. The Expert Treatment Guidelines for Patients with Schizophrenia recommends SSRIs, followed by venlafaxine then bupropion to treat depressive symptoms after optimizing second-generation antipsychotics.9

Another point to consider when treating residual symptoms in patients with schizophrenia is to not discontinue antipsychotic medications. Relapse rates for these patients can occur up to 5 times higher than for those who continue treatment.10 A way to address this problem could be the use of depot antipsychotic medications, but there are no set recommendations for the use of long-acting injectable antipsychotics in older patients. These medications should be used with caution and at lowest effective dosages to offset potential adverse effects.

With the introduction of typical and atypical antipsychotics, the use of electroconvulsive therapy in older patients with schizophrenia has declined. In a 2009 meta-analysis of studies that included patients with refractory schizophrenia and repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS), results revealed a mixed effect size for controlled and uncontrolled studies. The authors stated the need for further controlled trials, assessing the efficacy of rTMS on negative and positive symptoms of schizophrenia.11

Psychotherapy and psychosocial interventions

Patients with schizophrenia who have persistent psychotic symptoms while receiving adequate pharmacotherapy should be offered adjunctive cognitive, behaviorally oriented psychotherapy to reduce symptom severity. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) has been shown to help reduce relapse rates, reduce psychotic symptoms, and improve patients’ mental state.12 Amotivation and lack of insight can be particularly troublesome, which CBT can help address.12 Psychoeducation can:

- empower patients to understand their illness

- help them cope with their disease

- be aware of symptom relapse

- seek help sooner rather than later.

Also, counseling and supportive therapy are recommended by the American Psychiatric Association guidelines. Providers should involve family and loved ones in this discussion, so that they can help collaborate with care and provide a supportive and non-judgmental environment.

Older patients with residual symptoms of schizophrenia are less likely to have completed their education, pursued a career, or developed long-lasting relationships. Family members who were their support system earlier in life, such as parents, often are unable to provide care for them by the time patients with schizophrenia become older. These patients also are less likely to get married or have children, meaning that they are more likely to live alone. The advent of the interdisciplinary team, integration of several therapeutic modalities, the provision of case managers, and assertive community treatment (ACT) teams has provided help with social support, relapses, and hospitalizations, for older patients with schizophrenia.13 Key elements of ACT include:

- a multidisciplinary team, including a medication prescriber

- a shared caseload among team members

- direct service provision by team members

- frequent patient contact

- low patient to staff ratios

- outreach to patients in the community.

Medical care

Patients with schizophrenia are at higher risk for several comorbid medical conditions, such as diabetes, coronary artery disease, and digestive and liver disorders, compared with individuals without schizophrenia. This risk is associated with numerous factors, including sedentary lifestyle, high rates of lifetime cigarette use (70% to 80% of schizophrenia outpatients age <67 smoke), poor self-management skills, frequent homelessness, and unhealthy diet.

Although substantial attention is devoted to the psychiatric and behavioral management of patients with schizophrenia, many barriers impede the detection and treatment of their medical conditions. Patients with schizophrenia could experience delays in diagnosing a medical disorder, leading to more acute comorbidities at the time of diagnosis and premature mortality. Studies have confirmed that cardiovascular diseases are the leading cause of premature death among psychiatric patients in the United States.14 Key risk factors include smoking, obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, and lack of physical activity, all of which are more common among patients with schizophrenia compared with the general population.15 In addition, antipsychotics are associated with adverse metabolic effects.16

What are realistic treatment goals to manage residual symptoms in schizophrenia?

We believe that because remission in schizophrenia has been defined consensually, the bar for treatment expectations is set higher than it was 20 years ago. There can be patient-, family-, and system-related variables affecting the feasibility of treating residual symptoms. Providers who treat patients with schizophrenia should consider the following treatment goals:

- Prevent relapse and acute psychiatric hospitalization

- Use evidence-based strategies to minimize or monitor adverse effects

- Monitor compliance and consider use of depot antipsychotics combined with patients’ preference

- Facilitate ongoing safety assessment, including suicide risk

- Monitor negative and cognitive symptoms in addition to positive symptoms, using evidence-based management

- Encourage collaboration of care with family, caretakers, and other members of the treatment team

- Empower patients by providing psychoeducation and social skills training and assisting in their vocational rehabilitation

- Educate the patient and family about healthy lifestyle interventions and medical comorbidities common with schizophrenia

- Perform baseline screening and follow-up for early detection and treatment of medical comorbidities in patients with schizophrenia

- Improve functional status and quality of life.

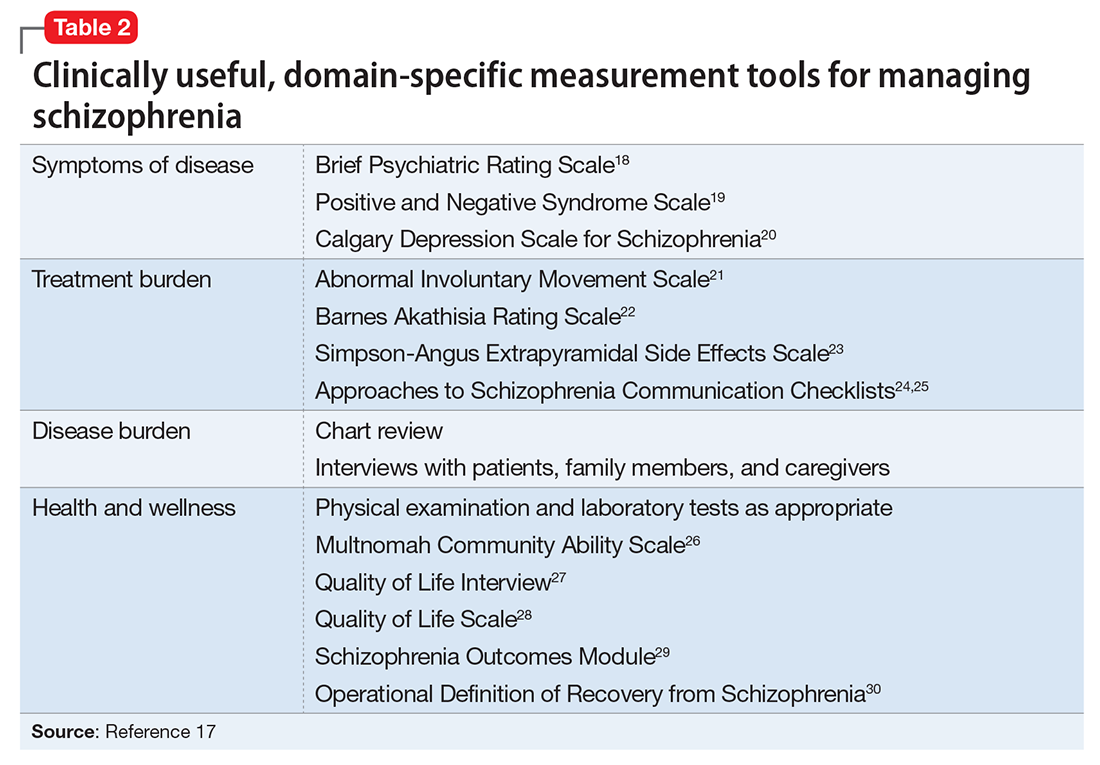

In addition to meeting these treatment goals, a measurement-based method can be implemented to monitor improvement and status of the independent treatment domains. A collection of rating instruments can be found in Table 2.17-30

The clinical presentation of patients with residual symptoms of schizophrenia differs from that of other patients with schizophrenia. Our understanding of residual symptoms in schizophrenia has come a long way in the last decade; however, we are still far from pinning the complex nature of these symptoms, let alone their management. Given the risk of morbidity and disability, there clearly is a need for further investigation and investment of time and resources to support developing novel pharmacological treatment options to manage residual symptoms in patients with schizophrenia.

Because patients with residual symptoms of schizophrenia usually are older, psychiatrists should be responsible for implementing necessary screening assessments and should closely collaborate with primary care practitioners and other specialists, and when necessary, treat comorbid medical conditions. The importance of educating patients, their families, and the treatment team cannot be overlooked. Further, psychiatric treatment facilities should offer and promote healthy lifestyle interventions.

1. Kaiser S, Lyne J, Agartz I, et al. Individual negative symptoms and domains - relevance for assessment, pathomechanisms and treatment [published online July 21, 2016]. Schizophr Res. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2016.07.013.

2. Taylor M, Chaudhry I, Cross M, et al. Towards consensus in the long-term management of relapse prevention in schizophrenia. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2005;20(3):175-181.

3. Schennach R, Riedel M, Obermeier M, et al. What are residual symptoms in schizophrenia spectrum disorder? Clinical description and 1-year persistence within a naturalistic trial. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2015;265(2):107-116.

4. Caligiuri MP, Jeste DV, Lacro JP. Antipsychotic-induced movement disorders in the elderly: epidemiology and treatment recommendations. Drugs Aging. 2000;17(5):363-384.

5. Dolder CR, Jeste DV. Incidence of tardive dyskinesia with typical versus atypical antipsychotics in very high risk patients. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;53(12):1142-1145.

6. Sable JA, Jeste DV. Antipsychotic treatment for late-life schizophrenia. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2002;4(4):299-306.

7. Newcomer JW. Second-generation (atypical) antipsychotics and metabolic effects: a comprehensive literature review. CNS Drugs. 2005;19(suppl 1):1-93.

8. Khan AY, Redden W, Ovais M, et al. Current concepts in the diagnosis and treatment of schizophrenia in later life. Current Geriatric Reports. 2015;4(4):290-300.

9. Alexopoulos GS, Streim J, Carpenter D, et al; Expert Consensus Panel for Using Antipsychotic Drugs in Older Patients. Using antipsychotic agents in older patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(suppl 2):5-99; discussion 100-102; quiz 103-104.

10. Robinson D, Woerner MG, Alvir JM, et al. Predictors of relapse following response from a first episode of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56(3):241-247.

11. Freitas C, Fregni F, Pascual-Leone A. Meta-analysis of the effects of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) on negative and positive symptoms in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2009;108(1-3):11-24.

12. Rector NA, Beck AT. Cognitive behavioral therapy for schizophrenia: an empirical review. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2012;200(10):832-839.

13. Stobbe J, Mulder NC, Roosenschoon BJ, et al. Assertive community treatment for elderly people with severe mental illness. BMC Psychiatry. 2010;10:84.

14. Hennekens CH, Hennekens AR, Hollar D, et al. Schizophrenia and increased risks of cardiovascular disease. Am Heart J. 2005;150(6):1115-1121.

15. Bushe CJ, Taylor M, Haukka J. Mortality in schizophrenia: a measurable clinical point. J Psychopharmacol. 2010;24(suppl 4):17-25.

16. Nasrallah HA, Meyer JM, Goff DC, et al. Low rates of treatment for hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes in schizophrenia: data from the CATIE schizophrenia trial sample at baseline. Schizophr Res. 2006;86(1-3):15-22.

17. Nasrallah HA, Targum SD, Tandon R, et al. Defining and measuring clinical effectiveness in the treatment of schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56(3):273-282.

18. Overall JE, Gorham DR. The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS): recent developments in ascertainment and scaling. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1988;24:97-99.

19. Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13(2):261-276.

20. Addington D, Addington J, Schissel B. A depression rating scale for schizophrenics. Schizophr Res. 1990;3(4):247-251.

21. Guy W. ECDEU Assessment manual for psychopharmacology revised, 1976. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare; Public Health Service; Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration; National Institute of Mental Health Psychopharmacology Research Branch, Division of Extramural Research Programs; 1976.

22. Barnes TR. A rating scale for drug-induced akathisia. Br J Psychiatry. 1989;154:672-676.

23. Simpson GM, Angus JWS. A rating scale for extrapyramidal side effects. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1970;45(212):11-19.

24. Dott SG, Weiden P, Hopwood P, et al. An innovative approach to clinical communication in schizophrenia: the Approaches to Schizophrenia Communication checklists. CNS Spectr. 2001;6(4):333-338.

25. Dott SG, Knesevich J, Miller A, et al. Using the ASC program: a training guide. J Psychiatr Pract. 2001;7(1):64-68.

26. Barker S, Barron N, McFarland BH, et al. Multnomah Community Ability Scale: user’s manual. Portland, OR: Western Mental Health Research Center, Oregon Health Sciences University; 1994.

27. Lehman AF. A quality of life interview for the chronically mentally ill. Eval Program Plann. 1988;11(1):51-62.

28. Heinrichs DW, Hanlon TE, Carpenter WT Jr. The Quality of Life Scale: an instrument for rating the schizophrenic deficit syndrome. Schizophr Bull. 1984;10(3):388-398.

29. Becker M, Diamond R, Sainfort F. A new patient focused index for measuring quality of life in persons with severe and persistent mental illness. Qual Life Res. 1993;2(4):239-251.

30. Liberman RP, Kopelowicz A, Ventura J, et al. Operational criteria and factors related to recovery from schizophrenia. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2009;14(4):256-272.

The course of chronic psychiatric conditions, such as schizophrenia, differs from chronic medical conditions, such as diabetes. Some patients with chronic psychiatric conditions achieve remission and become symptom-free, while others continue to have lingering signs of disease for life.

Residual symptoms of schizophrenia are not fully defined in the literature, which poses a challenge because they are central in the overall treatment of schizophrenia spectrum disorders.1 During this phase of schizophrenia, patients continue to have symptoms after psychosis has subsided. These patients might continue to have negative symptoms such as social and emotional withdrawal and low energy. Although frank psychotic behavior has disappeared, the patient might continue to hold strange beliefs. Pharmacotherapy is the primary treatment option for psychiatric conditions, but the psychosocial aspect may have greater importance when treating residual symptoms and patients with chronic psychiatric illness.2

A naturalistic study in Germany evaluated the occurrence and characteristics of residual symptoms in patients with schizophrenia.3 The authors used a Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale symptom severity score >1 for those purposes, which is possibly a stringent criterion to define residual symptoms. This multicenter study enrolled 399 individuals age 18 to 65 with a DSM-IV-TR diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, delusional disorder, or schizoaffective disorder.3 Of the 236 patients achieving remission at discharge, 94% had at least 1 residual symptom and 69% had at least 4 residual symptoms. Therefore, residual symptoms were highly prevalent in remitted patients. The most frequent residual symptoms were:

- blunted affect

- conceptual disorganization

- passive or apathetic social withdrawal

- emotional withdrawal

- lack of judgment and insight

- poor attention

- somatic concern

- difficulty with abstract thinking

- anxiety

- poor rapport.3

Of note, positive symptoms, such as delusions and hallucinatory behavior, were found in remitted patients at discharge (17% and 10%, respectively). The study concluded that the severity of residual symptoms was associated with relapse risk and had an overall negative impact on the outcome of patients with schizophrenia.3 The study noted that residual symptoms may be greater in number or volume than negative symptoms and questioned the origins of residual symptoms because most were present at baseline in more than two-third of patients.

Patients with residual symptoms of schizophrenia usually are older and therefore present specific management challenges for clinicians. Changes associated with aging, such as medical problems, cognitive deficits, and lack of social support, could create new care needs for this patient population. Although the biopsychosocial model used to treat chronic psychiatric conditions, especially schizophrenia, is preferred, older schizophrenia patients with residual symptoms often need more psychosocial interventions compared with young adults with schizophrenia.

Managing residual symptoms in schizophrenia

Few studies are devoted to pharmacological treatment of older adults with schizophrenia, likely because pharmacotherapy for older patients with schizophrenia can be challenging. Evidence-based treatment is based primarily on findings from younger patients who survived into later life. Clinicians often use the adage of geriatric psychiatry, “start low, go slow,” because older patients are susceptible to adverse effects associated with psychiatric medications, including cardiovascular, metabolic, anticholinergic, and extrapyramidal effects, orthostasis, sedation, falls, and neuroleptic malignant syndrome.

Older patients with schizophrenia are at an increased risk for extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) and anticholinergic adverse effects, perhaps because of degeneration of dopaminergic and cholinergic neurons.4 Lowering the anticholinergic load by discontinuing or reducing the dosage of medications with anticholinergic properties, when possible, is a key principle when treating these patients. This tactic could help improve cognition and quality of life by decreasing the risk of other anticholinergic adverse effects, including delirium, constipation, urinary retention, and blurred vision.

Patients treated with typical antipsychotics are nearly twice as likely to develop tardive dyskinesia compared with those receiving atypical antipsychotics.5 Sedation, orthostatic hypotension, and anticholinergic effects can cause cognitive clouding, worsen cognitive impairment, and increase the risk of falls, especially in older patients.6 Clozapine and olanzapine have the strongest association with clinically significant weight gain and treatment-induced type 2 diabetes mellitus.7

The appropriate starting dosage of antipsychotics in older patients with schizophrenia is one-fourth of the starting adult dosage. Total daily maintenance dosages may be one-third to one-half of the adult dosage.6 Consensus guidelines for dosing atypical antipsychotics for older patients with schizophrenia are as shown in Table 1.8

To ensure safety, patients should be regularly monitored with a complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, lipid panel, hemoglobin A1C, electrocardiogram, orthostatic vital signs, Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale, and weight check.7,9

When negative symptoms remain after a patient has achieved remission, it is important to evaluate whether the symptoms are related to adverse effects of medication (eg, parkinsonism syndrome), untreated depressive symptoms, or persistent positive symptoms, such as paranoia. Management of these symptoms consists of treating the cause, for example, using antipsychotics for primary positive symptoms, antidepressants for depression, anxiolytics for anxiety, and anti-parkinsonian agents or antipsychotic dosage reduction for EPS.

It is important to differentiate between negative symptoms of schizophrenia and depression in these patients. Negative symptoms of schizophrenia include affective flattening, alogia, avolition, and anhedonia. In depression, patients could have depressed mood, cognitive problems, sleep disturbances, and loss of appetite. Also, long-term symptoms are more consistent with negative symptomatology.

Keep in mind the potential for pharmacokinetic drug–drug interaction when using a combination of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), such as fluoxetine, paroxetine, and fluvoxamine (to treat negative/depressive symptoms), because all are significant inhibitors of cytochrome P450 enzymes and increase antipsychotic plasma level. The Expert Treatment Guidelines for Patients with Schizophrenia recommends SSRIs, followed by venlafaxine then bupropion to treat depressive symptoms after optimizing second-generation antipsychotics.9

Another point to consider when treating residual symptoms in patients with schizophrenia is to not discontinue antipsychotic medications. Relapse rates for these patients can occur up to 5 times higher than for those who continue treatment.10 A way to address this problem could be the use of depot antipsychotic medications, but there are no set recommendations for the use of long-acting injectable antipsychotics in older patients. These medications should be used with caution and at lowest effective dosages to offset potential adverse effects.

With the introduction of typical and atypical antipsychotics, the use of electroconvulsive therapy in older patients with schizophrenia has declined. In a 2009 meta-analysis of studies that included patients with refractory schizophrenia and repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS), results revealed a mixed effect size for controlled and uncontrolled studies. The authors stated the need for further controlled trials, assessing the efficacy of rTMS on negative and positive symptoms of schizophrenia.11

Psychotherapy and psychosocial interventions

Patients with schizophrenia who have persistent psychotic symptoms while receiving adequate pharmacotherapy should be offered adjunctive cognitive, behaviorally oriented psychotherapy to reduce symptom severity. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) has been shown to help reduce relapse rates, reduce psychotic symptoms, and improve patients’ mental state.12 Amotivation and lack of insight can be particularly troublesome, which CBT can help address.12 Psychoeducation can:

- empower patients to understand their illness

- help them cope with their disease

- be aware of symptom relapse

- seek help sooner rather than later.

Also, counseling and supportive therapy are recommended by the American Psychiatric Association guidelines. Providers should involve family and loved ones in this discussion, so that they can help collaborate with care and provide a supportive and non-judgmental environment.

Older patients with residual symptoms of schizophrenia are less likely to have completed their education, pursued a career, or developed long-lasting relationships. Family members who were their support system earlier in life, such as parents, often are unable to provide care for them by the time patients with schizophrenia become older. These patients also are less likely to get married or have children, meaning that they are more likely to live alone. The advent of the interdisciplinary team, integration of several therapeutic modalities, the provision of case managers, and assertive community treatment (ACT) teams has provided help with social support, relapses, and hospitalizations, for older patients with schizophrenia.13 Key elements of ACT include:

- a multidisciplinary team, including a medication prescriber

- a shared caseload among team members

- direct service provision by team members

- frequent patient contact

- low patient to staff ratios

- outreach to patients in the community.

Medical care

Patients with schizophrenia are at higher risk for several comorbid medical conditions, such as diabetes, coronary artery disease, and digestive and liver disorders, compared with individuals without schizophrenia. This risk is associated with numerous factors, including sedentary lifestyle, high rates of lifetime cigarette use (70% to 80% of schizophrenia outpatients age <67 smoke), poor self-management skills, frequent homelessness, and unhealthy diet.

Although substantial attention is devoted to the psychiatric and behavioral management of patients with schizophrenia, many barriers impede the detection and treatment of their medical conditions. Patients with schizophrenia could experience delays in diagnosing a medical disorder, leading to more acute comorbidities at the time of diagnosis and premature mortality. Studies have confirmed that cardiovascular diseases are the leading cause of premature death among psychiatric patients in the United States.14 Key risk factors include smoking, obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, and lack of physical activity, all of which are more common among patients with schizophrenia compared with the general population.15 In addition, antipsychotics are associated with adverse metabolic effects.16

What are realistic treatment goals to manage residual symptoms in schizophrenia?

We believe that because remission in schizophrenia has been defined consensually, the bar for treatment expectations is set higher than it was 20 years ago. There can be patient-, family-, and system-related variables affecting the feasibility of treating residual symptoms. Providers who treat patients with schizophrenia should consider the following treatment goals:

- Prevent relapse and acute psychiatric hospitalization

- Use evidence-based strategies to minimize or monitor adverse effects

- Monitor compliance and consider use of depot antipsychotics combined with patients’ preference

- Facilitate ongoing safety assessment, including suicide risk

- Monitor negative and cognitive symptoms in addition to positive symptoms, using evidence-based management

- Encourage collaboration of care with family, caretakers, and other members of the treatment team

- Empower patients by providing psychoeducation and social skills training and assisting in their vocational rehabilitation

- Educate the patient and family about healthy lifestyle interventions and medical comorbidities common with schizophrenia

- Perform baseline screening and follow-up for early detection and treatment of medical comorbidities in patients with schizophrenia

- Improve functional status and quality of life.

In addition to meeting these treatment goals, a measurement-based method can be implemented to monitor improvement and status of the independent treatment domains. A collection of rating instruments can be found in Table 2.17-30

The clinical presentation of patients with residual symptoms of schizophrenia differs from that of other patients with schizophrenia. Our understanding of residual symptoms in schizophrenia has come a long way in the last decade; however, we are still far from pinning the complex nature of these symptoms, let alone their management. Given the risk of morbidity and disability, there clearly is a need for further investigation and investment of time and resources to support developing novel pharmacological treatment options to manage residual symptoms in patients with schizophrenia.

Because patients with residual symptoms of schizophrenia usually are older, psychiatrists should be responsible for implementing necessary screening assessments and should closely collaborate with primary care practitioners and other specialists, and when necessary, treat comorbid medical conditions. The importance of educating patients, their families, and the treatment team cannot be overlooked. Further, psychiatric treatment facilities should offer and promote healthy lifestyle interventions.

The course of chronic psychiatric conditions, such as schizophrenia, differs from chronic medical conditions, such as diabetes. Some patients with chronic psychiatric conditions achieve remission and become symptom-free, while others continue to have lingering signs of disease for life.

Residual symptoms of schizophrenia are not fully defined in the literature, which poses a challenge because they are central in the overall treatment of schizophrenia spectrum disorders.1 During this phase of schizophrenia, patients continue to have symptoms after psychosis has subsided. These patients might continue to have negative symptoms such as social and emotional withdrawal and low energy. Although frank psychotic behavior has disappeared, the patient might continue to hold strange beliefs. Pharmacotherapy is the primary treatment option for psychiatric conditions, but the psychosocial aspect may have greater importance when treating residual symptoms and patients with chronic psychiatric illness.2

A naturalistic study in Germany evaluated the occurrence and characteristics of residual symptoms in patients with schizophrenia.3 The authors used a Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale symptom severity score >1 for those purposes, which is possibly a stringent criterion to define residual symptoms. This multicenter study enrolled 399 individuals age 18 to 65 with a DSM-IV-TR diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, delusional disorder, or schizoaffective disorder.3 Of the 236 patients achieving remission at discharge, 94% had at least 1 residual symptom and 69% had at least 4 residual symptoms. Therefore, residual symptoms were highly prevalent in remitted patients. The most frequent residual symptoms were:

- blunted affect

- conceptual disorganization

- passive or apathetic social withdrawal

- emotional withdrawal

- lack of judgment and insight

- poor attention

- somatic concern

- difficulty with abstract thinking

- anxiety

- poor rapport.3

Of note, positive symptoms, such as delusions and hallucinatory behavior, were found in remitted patients at discharge (17% and 10%, respectively). The study concluded that the severity of residual symptoms was associated with relapse risk and had an overall negative impact on the outcome of patients with schizophrenia.3 The study noted that residual symptoms may be greater in number or volume than negative symptoms and questioned the origins of residual symptoms because most were present at baseline in more than two-third of patients.

Patients with residual symptoms of schizophrenia usually are older and therefore present specific management challenges for clinicians. Changes associated with aging, such as medical problems, cognitive deficits, and lack of social support, could create new care needs for this patient population. Although the biopsychosocial model used to treat chronic psychiatric conditions, especially schizophrenia, is preferred, older schizophrenia patients with residual symptoms often need more psychosocial interventions compared with young adults with schizophrenia.

Managing residual symptoms in schizophrenia

Few studies are devoted to pharmacological treatment of older adults with schizophrenia, likely because pharmacotherapy for older patients with schizophrenia can be challenging. Evidence-based treatment is based primarily on findings from younger patients who survived into later life. Clinicians often use the adage of geriatric psychiatry, “start low, go slow,” because older patients are susceptible to adverse effects associated with psychiatric medications, including cardiovascular, metabolic, anticholinergic, and extrapyramidal effects, orthostasis, sedation, falls, and neuroleptic malignant syndrome.

Older patients with schizophrenia are at an increased risk for extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) and anticholinergic adverse effects, perhaps because of degeneration of dopaminergic and cholinergic neurons.4 Lowering the anticholinergic load by discontinuing or reducing the dosage of medications with anticholinergic properties, when possible, is a key principle when treating these patients. This tactic could help improve cognition and quality of life by decreasing the risk of other anticholinergic adverse effects, including delirium, constipation, urinary retention, and blurred vision.

Patients treated with typical antipsychotics are nearly twice as likely to develop tardive dyskinesia compared with those receiving atypical antipsychotics.5 Sedation, orthostatic hypotension, and anticholinergic effects can cause cognitive clouding, worsen cognitive impairment, and increase the risk of falls, especially in older patients.6 Clozapine and olanzapine have the strongest association with clinically significant weight gain and treatment-induced type 2 diabetes mellitus.7

The appropriate starting dosage of antipsychotics in older patients with schizophrenia is one-fourth of the starting adult dosage. Total daily maintenance dosages may be one-third to one-half of the adult dosage.6 Consensus guidelines for dosing atypical antipsychotics for older patients with schizophrenia are as shown in Table 1.8

To ensure safety, patients should be regularly monitored with a complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, lipid panel, hemoglobin A1C, electrocardiogram, orthostatic vital signs, Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale, and weight check.7,9

When negative symptoms remain after a patient has achieved remission, it is important to evaluate whether the symptoms are related to adverse effects of medication (eg, parkinsonism syndrome), untreated depressive symptoms, or persistent positive symptoms, such as paranoia. Management of these symptoms consists of treating the cause, for example, using antipsychotics for primary positive symptoms, antidepressants for depression, anxiolytics for anxiety, and anti-parkinsonian agents or antipsychotic dosage reduction for EPS.

It is important to differentiate between negative symptoms of schizophrenia and depression in these patients. Negative symptoms of schizophrenia include affective flattening, alogia, avolition, and anhedonia. In depression, patients could have depressed mood, cognitive problems, sleep disturbances, and loss of appetite. Also, long-term symptoms are more consistent with negative symptomatology.

Keep in mind the potential for pharmacokinetic drug–drug interaction when using a combination of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), such as fluoxetine, paroxetine, and fluvoxamine (to treat negative/depressive symptoms), because all are significant inhibitors of cytochrome P450 enzymes and increase antipsychotic plasma level. The Expert Treatment Guidelines for Patients with Schizophrenia recommends SSRIs, followed by venlafaxine then bupropion to treat depressive symptoms after optimizing second-generation antipsychotics.9

Another point to consider when treating residual symptoms in patients with schizophrenia is to not discontinue antipsychotic medications. Relapse rates for these patients can occur up to 5 times higher than for those who continue treatment.10 A way to address this problem could be the use of depot antipsychotic medications, but there are no set recommendations for the use of long-acting injectable antipsychotics in older patients. These medications should be used with caution and at lowest effective dosages to offset potential adverse effects.

With the introduction of typical and atypical antipsychotics, the use of electroconvulsive therapy in older patients with schizophrenia has declined. In a 2009 meta-analysis of studies that included patients with refractory schizophrenia and repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS), results revealed a mixed effect size for controlled and uncontrolled studies. The authors stated the need for further controlled trials, assessing the efficacy of rTMS on negative and positive symptoms of schizophrenia.11

Psychotherapy and psychosocial interventions

Patients with schizophrenia who have persistent psychotic symptoms while receiving adequate pharmacotherapy should be offered adjunctive cognitive, behaviorally oriented psychotherapy to reduce symptom severity. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) has been shown to help reduce relapse rates, reduce psychotic symptoms, and improve patients’ mental state.12 Amotivation and lack of insight can be particularly troublesome, which CBT can help address.12 Psychoeducation can:

- empower patients to understand their illness

- help them cope with their disease

- be aware of symptom relapse

- seek help sooner rather than later.

Also, counseling and supportive therapy are recommended by the American Psychiatric Association guidelines. Providers should involve family and loved ones in this discussion, so that they can help collaborate with care and provide a supportive and non-judgmental environment.

Older patients with residual symptoms of schizophrenia are less likely to have completed their education, pursued a career, or developed long-lasting relationships. Family members who were their support system earlier in life, such as parents, often are unable to provide care for them by the time patients with schizophrenia become older. These patients also are less likely to get married or have children, meaning that they are more likely to live alone. The advent of the interdisciplinary team, integration of several therapeutic modalities, the provision of case managers, and assertive community treatment (ACT) teams has provided help with social support, relapses, and hospitalizations, for older patients with schizophrenia.13 Key elements of ACT include:

- a multidisciplinary team, including a medication prescriber

- a shared caseload among team members

- direct service provision by team members

- frequent patient contact

- low patient to staff ratios

- outreach to patients in the community.

Medical care

Patients with schizophrenia are at higher risk for several comorbid medical conditions, such as diabetes, coronary artery disease, and digestive and liver disorders, compared with individuals without schizophrenia. This risk is associated with numerous factors, including sedentary lifestyle, high rates of lifetime cigarette use (70% to 80% of schizophrenia outpatients age <67 smoke), poor self-management skills, frequent homelessness, and unhealthy diet.

Although substantial attention is devoted to the psychiatric and behavioral management of patients with schizophrenia, many barriers impede the detection and treatment of their medical conditions. Patients with schizophrenia could experience delays in diagnosing a medical disorder, leading to more acute comorbidities at the time of diagnosis and premature mortality. Studies have confirmed that cardiovascular diseases are the leading cause of premature death among psychiatric patients in the United States.14 Key risk factors include smoking, obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, and lack of physical activity, all of which are more common among patients with schizophrenia compared with the general population.15 In addition, antipsychotics are associated with adverse metabolic effects.16

What are realistic treatment goals to manage residual symptoms in schizophrenia?

We believe that because remission in schizophrenia has been defined consensually, the bar for treatment expectations is set higher than it was 20 years ago. There can be patient-, family-, and system-related variables affecting the feasibility of treating residual symptoms. Providers who treat patients with schizophrenia should consider the following treatment goals:

- Prevent relapse and acute psychiatric hospitalization

- Use evidence-based strategies to minimize or monitor adverse effects

- Monitor compliance and consider use of depot antipsychotics combined with patients’ preference

- Facilitate ongoing safety assessment, including suicide risk

- Monitor negative and cognitive symptoms in addition to positive symptoms, using evidence-based management

- Encourage collaboration of care with family, caretakers, and other members of the treatment team

- Empower patients by providing psychoeducation and social skills training and assisting in their vocational rehabilitation

- Educate the patient and family about healthy lifestyle interventions and medical comorbidities common with schizophrenia

- Perform baseline screening and follow-up for early detection and treatment of medical comorbidities in patients with schizophrenia

- Improve functional status and quality of life.

In addition to meeting these treatment goals, a measurement-based method can be implemented to monitor improvement and status of the independent treatment domains. A collection of rating instruments can be found in Table 2.17-30

The clinical presentation of patients with residual symptoms of schizophrenia differs from that of other patients with schizophrenia. Our understanding of residual symptoms in schizophrenia has come a long way in the last decade; however, we are still far from pinning the complex nature of these symptoms, let alone their management. Given the risk of morbidity and disability, there clearly is a need for further investigation and investment of time and resources to support developing novel pharmacological treatment options to manage residual symptoms in patients with schizophrenia.

Because patients with residual symptoms of schizophrenia usually are older, psychiatrists should be responsible for implementing necessary screening assessments and should closely collaborate with primary care practitioners and other specialists, and when necessary, treat comorbid medical conditions. The importance of educating patients, their families, and the treatment team cannot be overlooked. Further, psychiatric treatment facilities should offer and promote healthy lifestyle interventions.

1. Kaiser S, Lyne J, Agartz I, et al. Individual negative symptoms and domains - relevance for assessment, pathomechanisms and treatment [published online July 21, 2016]. Schizophr Res. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2016.07.013.

2. Taylor M, Chaudhry I, Cross M, et al. Towards consensus in the long-term management of relapse prevention in schizophrenia. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2005;20(3):175-181.

3. Schennach R, Riedel M, Obermeier M, et al. What are residual symptoms in schizophrenia spectrum disorder? Clinical description and 1-year persistence within a naturalistic trial. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2015;265(2):107-116.

4. Caligiuri MP, Jeste DV, Lacro JP. Antipsychotic-induced movement disorders in the elderly: epidemiology and treatment recommendations. Drugs Aging. 2000;17(5):363-384.

5. Dolder CR, Jeste DV. Incidence of tardive dyskinesia with typical versus atypical antipsychotics in very high risk patients. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;53(12):1142-1145.

6. Sable JA, Jeste DV. Antipsychotic treatment for late-life schizophrenia. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2002;4(4):299-306.

7. Newcomer JW. Second-generation (atypical) antipsychotics and metabolic effects: a comprehensive literature review. CNS Drugs. 2005;19(suppl 1):1-93.

8. Khan AY, Redden W, Ovais M, et al. Current concepts in the diagnosis and treatment of schizophrenia in later life. Current Geriatric Reports. 2015;4(4):290-300.

9. Alexopoulos GS, Streim J, Carpenter D, et al; Expert Consensus Panel for Using Antipsychotic Drugs in Older Patients. Using antipsychotic agents in older patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(suppl 2):5-99; discussion 100-102; quiz 103-104.

10. Robinson D, Woerner MG, Alvir JM, et al. Predictors of relapse following response from a first episode of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56(3):241-247.

11. Freitas C, Fregni F, Pascual-Leone A. Meta-analysis of the effects of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) on negative and positive symptoms in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2009;108(1-3):11-24.

12. Rector NA, Beck AT. Cognitive behavioral therapy for schizophrenia: an empirical review. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2012;200(10):832-839.

13. Stobbe J, Mulder NC, Roosenschoon BJ, et al. Assertive community treatment for elderly people with severe mental illness. BMC Psychiatry. 2010;10:84.

14. Hennekens CH, Hennekens AR, Hollar D, et al. Schizophrenia and increased risks of cardiovascular disease. Am Heart J. 2005;150(6):1115-1121.

15. Bushe CJ, Taylor M, Haukka J. Mortality in schizophrenia: a measurable clinical point. J Psychopharmacol. 2010;24(suppl 4):17-25.

16. Nasrallah HA, Meyer JM, Goff DC, et al. Low rates of treatment for hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes in schizophrenia: data from the CATIE schizophrenia trial sample at baseline. Schizophr Res. 2006;86(1-3):15-22.

17. Nasrallah HA, Targum SD, Tandon R, et al. Defining and measuring clinical effectiveness in the treatment of schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56(3):273-282.

18. Overall JE, Gorham DR. The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS): recent developments in ascertainment and scaling. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1988;24:97-99.

19. Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13(2):261-276.

20. Addington D, Addington J, Schissel B. A depression rating scale for schizophrenics. Schizophr Res. 1990;3(4):247-251.

21. Guy W. ECDEU Assessment manual for psychopharmacology revised, 1976. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare; Public Health Service; Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration; National Institute of Mental Health Psychopharmacology Research Branch, Division of Extramural Research Programs; 1976.

22. Barnes TR. A rating scale for drug-induced akathisia. Br J Psychiatry. 1989;154:672-676.

23. Simpson GM, Angus JWS. A rating scale for extrapyramidal side effects. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1970;45(212):11-19.

24. Dott SG, Weiden P, Hopwood P, et al. An innovative approach to clinical communication in schizophrenia: the Approaches to Schizophrenia Communication checklists. CNS Spectr. 2001;6(4):333-338.

25. Dott SG, Knesevich J, Miller A, et al. Using the ASC program: a training guide. J Psychiatr Pract. 2001;7(1):64-68.

26. Barker S, Barron N, McFarland BH, et al. Multnomah Community Ability Scale: user’s manual. Portland, OR: Western Mental Health Research Center, Oregon Health Sciences University; 1994.

27. Lehman AF. A quality of life interview for the chronically mentally ill. Eval Program Plann. 1988;11(1):51-62.

28. Heinrichs DW, Hanlon TE, Carpenter WT Jr. The Quality of Life Scale: an instrument for rating the schizophrenic deficit syndrome. Schizophr Bull. 1984;10(3):388-398.

29. Becker M, Diamond R, Sainfort F. A new patient focused index for measuring quality of life in persons with severe and persistent mental illness. Qual Life Res. 1993;2(4):239-251.

30. Liberman RP, Kopelowicz A, Ventura J, et al. Operational criteria and factors related to recovery from schizophrenia. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2009;14(4):256-272.

1. Kaiser S, Lyne J, Agartz I, et al. Individual negative symptoms and domains - relevance for assessment, pathomechanisms and treatment [published online July 21, 2016]. Schizophr Res. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2016.07.013.

2. Taylor M, Chaudhry I, Cross M, et al. Towards consensus in the long-term management of relapse prevention in schizophrenia. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2005;20(3):175-181.

3. Schennach R, Riedel M, Obermeier M, et al. What are residual symptoms in schizophrenia spectrum disorder? Clinical description and 1-year persistence within a naturalistic trial. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2015;265(2):107-116.

4. Caligiuri MP, Jeste DV, Lacro JP. Antipsychotic-induced movement disorders in the elderly: epidemiology and treatment recommendations. Drugs Aging. 2000;17(5):363-384.

5. Dolder CR, Jeste DV. Incidence of tardive dyskinesia with typical versus atypical antipsychotics in very high risk patients. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;53(12):1142-1145.

6. Sable JA, Jeste DV. Antipsychotic treatment for late-life schizophrenia. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2002;4(4):299-306.

7. Newcomer JW. Second-generation (atypical) antipsychotics and metabolic effects: a comprehensive literature review. CNS Drugs. 2005;19(suppl 1):1-93.

8. Khan AY, Redden W, Ovais M, et al. Current concepts in the diagnosis and treatment of schizophrenia in later life. Current Geriatric Reports. 2015;4(4):290-300.

9. Alexopoulos GS, Streim J, Carpenter D, et al; Expert Consensus Panel for Using Antipsychotic Drugs in Older Patients. Using antipsychotic agents in older patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(suppl 2):5-99; discussion 100-102; quiz 103-104.

10. Robinson D, Woerner MG, Alvir JM, et al. Predictors of relapse following response from a first episode of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56(3):241-247.

11. Freitas C, Fregni F, Pascual-Leone A. Meta-analysis of the effects of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) on negative and positive symptoms in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2009;108(1-3):11-24.

12. Rector NA, Beck AT. Cognitive behavioral therapy for schizophrenia: an empirical review. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2012;200(10):832-839.

13. Stobbe J, Mulder NC, Roosenschoon BJ, et al. Assertive community treatment for elderly people with severe mental illness. BMC Psychiatry. 2010;10:84.

14. Hennekens CH, Hennekens AR, Hollar D, et al. Schizophrenia and increased risks of cardiovascular disease. Am Heart J. 2005;150(6):1115-1121.

15. Bushe CJ, Taylor M, Haukka J. Mortality in schizophrenia: a measurable clinical point. J Psychopharmacol. 2010;24(suppl 4):17-25.

16. Nasrallah HA, Meyer JM, Goff DC, et al. Low rates of treatment for hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes in schizophrenia: data from the CATIE schizophrenia trial sample at baseline. Schizophr Res. 2006;86(1-3):15-22.

17. Nasrallah HA, Targum SD, Tandon R, et al. Defining and measuring clinical effectiveness in the treatment of schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56(3):273-282.

18. Overall JE, Gorham DR. The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS): recent developments in ascertainment and scaling. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1988;24:97-99.

19. Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13(2):261-276.

20. Addington D, Addington J, Schissel B. A depression rating scale for schizophrenics. Schizophr Res. 1990;3(4):247-251.

21. Guy W. ECDEU Assessment manual for psychopharmacology revised, 1976. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare; Public Health Service; Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration; National Institute of Mental Health Psychopharmacology Research Branch, Division of Extramural Research Programs; 1976.

22. Barnes TR. A rating scale for drug-induced akathisia. Br J Psychiatry. 1989;154:672-676.

23. Simpson GM, Angus JWS. A rating scale for extrapyramidal side effects. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1970;45(212):11-19.

24. Dott SG, Weiden P, Hopwood P, et al. An innovative approach to clinical communication in schizophrenia: the Approaches to Schizophrenia Communication checklists. CNS Spectr. 2001;6(4):333-338.

25. Dott SG, Knesevich J, Miller A, et al. Using the ASC program: a training guide. J Psychiatr Pract. 2001;7(1):64-68.

26. Barker S, Barron N, McFarland BH, et al. Multnomah Community Ability Scale: user’s manual. Portland, OR: Western Mental Health Research Center, Oregon Health Sciences University; 1994.

27. Lehman AF. A quality of life interview for the chronically mentally ill. Eval Program Plann. 1988;11(1):51-62.

28. Heinrichs DW, Hanlon TE, Carpenter WT Jr. The Quality of Life Scale: an instrument for rating the schizophrenic deficit syndrome. Schizophr Bull. 1984;10(3):388-398.

29. Becker M, Diamond R, Sainfort F. A new patient focused index for measuring quality of life in persons with severe and persistent mental illness. Qual Life Res. 1993;2(4):239-251.

30. Liberman RP, Kopelowicz A, Ventura J, et al. Operational criteria and factors related to recovery from schizophrenia. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2009;14(4):256-272.

Vilazodone for major depressive disorder

In January 2011, the FDA approved vilazodone for the treatment of major depressive disorder (MDD) (Table 1).

Vilazodone was discovered by Merck KGaA in Germany.1 In February 2001, Merck KGaA licensed vilazodone to GlaxoSmithKline. In April 2003, GlaxoSmithKline returned all rights to Merck KGaA because phase IIb clinical data did not support progression to phase III clinical trials. In September 2004, Genaissance Pharmaceuticals Inc. acquired an exclusive worldwide license from Merck KGaA to develop and commercialize vilazodone for depression treatment.2 Subsequently, Clinical Data Inc. acquired Genaissance Pharmaceuticals Inc., including vilazodone, and proceeded with 2 phase III trials and a large safety trial resulting in FDA approval. In February 2011, Forest Laboratories Inc. acquired Clinical Data Inc. and will launch vilazodone in second quarter of 2011.

Table 1

Vilazodone: Fast facts

| Brand name: Viibryd |

| Class: Serotonin reuptake inhibitor and 5-HT1A receptor partial agonist |

| Indication: Major depressive disorder |

| Approval date: January 24, 2011 |

| Availability date: Second quarter of 2011 |

| Manufacturer: Forest Laboratories Inc. |

| Dosage forms: 10 mg, 20 mg, and 40 mg tablets |

| Starting dose: 10 mg/d |

| Target dose: 40 mg/d |

How it works

Similar to all antidepressants, vilazodone’s mechanism of action is not fully understood, but is thought to be related to its inhibition of serotonin (ie, 5-HT) reuptake and partial agonism of 5-HT1A receptors.3 Vilazodone technically is not a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) because it has greater affinity for the 5-HT1A receptor (0.2nM) than it does for the 5-HT reuptake pump (0.5nM).4

Vilazodone was developed based on the theory that inhibition of 5-HT1A autoreceptor inhibition was responsible for SSRIs’ delayed (approximately 2 weeks) onset of antidepressant efficacy. Briefly, this theory is as follows: In humans, 5-HT1A receptors are primarily presynaptic in the raphe nuclei and postsynaptic 5-HT1A receptors predominate in the neocortex and limbic regions of the brain.5 Presynaptically, 5-HT1A are autoreceptors, ie, serotonin stimulation of these receptors results in inhibition of firing of 5-HT neurons, while postsynaptically they may be involved in downstream serotonergic effects such as sexual function.5 SSRIs are thought to work as antidepressants by increasing 5-HT concentration in the synapse but their initial effect is to turn off 5-HT neuronal firing as a result of increased concentration of 5-HT at the presynaptic 5-HT1A autoreceptor. Subsequently, these 5-HT1A autoreceptors subsensitize such that 5-HT neuronal firing rate returns to normal. The time course for this subsensitization parallels the onset of SSRI antidepressant efficacy. For several years, efforts have been made to antagonize the 5-HT1A presynaptic autoreceptors as a means of potentially shortening SSRIs’ onset of efficacy.6-8

Pharmacokinetics

Vilazodone is absorbed in the gastrointestinal tract and reaches peak concentration at a median of 4 to 5 hours. Its bioavailability increases when taken with food such that Cmax (maximum concentration) is increased by 147% to 160%, and area under the curve is increased by 64% to 85%. Its absolute bioavailability in the presence of food is 72%.4 In systemic circulation, the drug is 96% to 99% protein-bound.3 Vilazodone is eliminated primarily through cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4 metabolism in the liver.3

Terminal half-life of vilazodone is 25 hours. In general, steady state is achieved in 4 to 5 times the half-life at a stable dose. However, dosing guidelines for vilazodone recommend titration over 2 weeks to achieve a target of 40 mg/d. Thus, steady state will not be achieved until the patient has been on the stable target dose for approximately 2.5 weeks.3

Efficacy

Vilazodone’ efficacy for MDD treatment was established in 2 pivotal 8-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, but not active-controlled, trials (Table 2).9-11 Study participants were outpatients age 18 to 65 who met DSM-IV-TR criteria for MDD. Patients were required to have a 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D-17) score >22 and a HAM-D-17 item 1 (depressed mood) score >2.

In the first clinical trial, 410 patients were randomly assigned to vilazodone or placebo. In the vilazodone group, patients were started on 10 mg/d for 1 week, titrated to 20 mg/d for a second week, and then 40 mg/d for the remainder of the study. At week 8, the mean change from baseline on the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS), HAM-D-17, Clinical Global Impression-Improvement scale (CGI-I), Clinical Global Impression-Severity scale (CGI-S), and Hamilton Anxiety scale (HAM-A) was statistically greater with vilazodone than placebo (P <.05).9 Compared with placebo, vilazodone-treated patients showed a statistically significant (P <. 05) improvement in MADRS and HAM-D-17 scores at week 1. Approximately 12% more vilazodone-treated patients achieved response (defined as ≥50% decrease in total score at end of treatment) on the primary efficacy measure, which was MADRS (40.4% vs 28.1%, P=.007), and the 2 secondary efficacy measures, which were HAM-D-17 (44.4% vs 32.7%, P =.011) and CGI-I (48.0 vs 32.7, P =.001). Remission rates (MADRS <10) were not reported in this study, but the authors stated that there was no statistical difference in remission rates between the vilazodone and placebo groups.9

In a second trial, which featured design and titration schedule identical to that of the first study, 481 patients were randomized to vilazodone or placebo.10 At week 8, the vilazodone-treated patients had significantly greater improvement in MADRS, HAM-D-17, HAM-A, CGI-S, and CGI-I score compared with the placebo group (P <.05). Approximately 14% more patients in the vilazodone group were MADRS responders compared with placebo (44% vs 30%, P =.002). Remission rates were not statistically different between patients taking vilazodone vs placebo (27% vs 20% respectively).10 Demonstrating a statistically significant difference between a 27% vs 20% remission rate would require a much larger number of patients than were included in this study.

Table 2

Efficacy of vilazodone in phase III clinical trials

| Trial | Drug response rate | Placebo response rate | Drug-specific response rate* | NNT† | Average reduction in MADRS change (drug minus placebo) (mean) | Average reduction in HAM-D change (drug minus placebo) (mean) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rickels et al9 | 40% | 28% | 12% | 100/12=8 | 12.9 to 9.6 (3.3) | 10.4 to 8.6 (1.8) |

| Khan et al10 | 44% | 30% | 14% | 100/14=7 | 13.3 to 10.8 (2.5) | 10.7 to 9.1 (1.6) |

| HAM-D: Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; MADRS: Montgomery-Åsburg Depression Rating Scale; NNT: number needed to treat *Difference in response rate between the drug and placebo groups. This rate is what the drug added to the treatment effects seen as a result of time and clinical management provided in the trial †The number of patients who need to be treated to benefit (ie, achieve response) one additional patient compared with placebo Source: Reference 11. Table reproduced with permission from Sheldon H. Preskorn, MD | ||||||

Tolerability

Vilazodone’s safety was evaluated in 2, 177 patients (age 18 to 70) diagnosed with MDD who participated in clinical studies, including the two 8-week, randomized, doubleblind, placebo-controlled studies (N=891) and a 52-week, open-label study of 599 patients.12 Overall, 7.1% of patients who received vilazodone discontinued treatment because of an adverse reaction, compared with 3.2% of placebo-treated patients in the double-blind studies.3 Diarrhea, nausea, and headache were the most commonly reported adverse events; the incidence of headache was similar to that in the placebo group (13.2% vs 14.2%).10 These adverse events are consistent with serotonin agonism, mild to moderate intensity, and occurred mainly during the first week of treatment.3

Doses up to 80 mg/d have not been associated with clinically significant changes in ECG parameters or laboratory parameters in serum chemistry hematology and urine analysis.9,10 The drug had no effect on weight as measured by mean change from baseline.9,10

In one 8-week trial, there were no substantial differences between vilazodone and placebo in Arizona Sexual Experience Scale (ASEX) scores at treatment end for either sex.9 ASEX is a 5-item scale used to assess sexual dysfunction; a score >18 indicates clinically significant sexual dysfunction. At baseline, mean ASEX scores among men were 15.8 in the placebo group and 16.5 in the vilazodone group. Among women, the mean ASEX score was 21.2 in both groups.9 Overall sexual function for men and women was similar for vilazodone and placebo, as measured by the Changes in Sexual Function Questionnaire.10 The most commonly reported sexual adverse effect was decreased libido.10

Contraindications

Vilazodone is contraindicated for concomitant use with monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) or within 14 days of stopping or starting an MAOI. Vilazodone is contraindicated in patients taking strong CYP3A4 inhibitors (eg, ketoconazole) because of increased vilazodone concentrations and resulting concentration-dependent adverse effects.3 Concomitant administration of strong CYP3A4 inducers (eg, rifampin) might result in a reduction in vilazodone levels leading to lack or loss of efficacy.13

As with other antidepressants, vilazodone carries a black-box warning about increased risk of suicidal thinking and behavior in children, adolescents, and young adults taking antidepressants for MDD and other psychiatric disorders.3 Vilazodone showed evidence of developmental toxicity in rats, but was not teratogenic in rats or rabbits. There are no adequate, well-controlled studies of vilazodone in pregnant women and no human data regarding vilazodone concentrations in breast milk.3 Women taking vilazodone are advised to breastfeed only if the potential benefits outweigh the risks. Vilazodone is not recommended for use in pediatric patients.3

Similar to other antidepressants, vilazodone labeling carries warnings about serotonin syndrome, seizures, abnormal bleeding, activation of mania/hypomania, and hyponatremia.4

Dosing

Vilazodone is available as 10 mg, 20 mg, and 40 mg tablets. The recommended target dose for vilazodone is 40 mg/d, with a starting dose of 10 mg/d for 7 days, followed by 20 mg/d for 7 days, then 40 mg/d.3 The drug should be taken with food, but unlike other psychotropics, the manufacturer does not recommended a specific calorie amount.3 Dose tapering is recommended when the drug is discontinued.3

Dose should be reduced to 20 mg/d when vilazodone is coadministered with strong CYP3A4 inhibitors, such as azole antifungals, macrolides, protease inhibitors, and verapamil.13 No dosage adjustment is recommended based on age, mild or moderate liver impairment, or renal impairment of any severity.3 Vilazodone has not been studied in patients with severe hepatic impairment.3

How does vilazodone compare?

Ideally, it would be good to know how vilazodone compares with other marketed antidepressants. Unfortunately, there are no published head-to-head comparison data to address this matter. The number needed to treat with vilazodone is between 7 and 8 based on the data from the 2 phase III trials (Table 2).9-11 This is comparable to other antidepressants. One phase III study showed a statistically greater reduction in depressive symptomatology in vilazodone-treated patients after 1 week, 9 but that was not replicated in the second trial.10

Related Resources

- Khan A. Vilazodone, a novel dual-acting serotonergic antidepressant for managing major depression. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2009;18(11):1753-1764.

Drug Brand Names

- Ketoconazole • Nizoral

- Rifampin • Rifadin

- Verapamil • Isoptin

- Vilazodone • Viibryd

Disclosures

Drs. Kalia and Mittal report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article, or with manufacturers of competing products.

Since January 2010, Dr. Preskorn has received grant/research support from Abbott Laboratories, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly and Company, Ipsen, Link Medicine, Pfizer Inc, Sunovion, Takeda, and Targacept. He has been a consultant to Abbott Laboratories, Allergan, Biovail, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eisai, Eli Lilly and Company, Evotec Johnson and Johnson, Labopharm, Merck, NovaDel Pharma, Orexigen, Prexa, Psylin Neurosciences Inc., and Sunovion. He is on the speakers bureau of Eisai, Pfizer Inc., and Sunovion.

1. Bartoszyk GD, Hegenbart R, Ziegler H. EMD 68843 a serotonin reuptake inhibitor with selective presynaptic 5-HT1A receptor agonistic properties. Eur J Pharmacol. 1997;322(2-3):147-153.

2. de Paulis T. Drug evaluation: vilazodone—a combined SSRI and 5-HT1A partial agonist for the treatment of depression. IDrugs 2007;10(3):193-201.

3. Viibryd [package insert]. New Haven CT: Trovis Pharmaceuticals, LLC; 2011.

4. Heinrich T, Böttcher H, Schiemann K, et al. Dual 5-HT1A agonists and 5-HT re-uptake inhibitors by combination of indole-butyl-amine and chromenonyl-piperazine structural elements in a single molecular entity. Bioorg Med Chem. 2004;12(18):4843-4852.

5. Blier P, Ward NM. Is there a role for 5-HT1A agonists in the treatment of depression? Biol Psychiatry. 2003;53:193-203.

6. Bielski RJ, Cunningham L, Horrigan JP, et al. Gepirone extended-release in the treatment of adult outpatients with major depressive disorder: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69:571-577.

7. Gammans RE, Stringfellow JC, Hvizdos AJ, et al. Use of buspirone in patients with generalized anxiety disorder and coexisting depressive symptoms. A meta-analysis of eight randomized, controlled studies. Neuropsychobiology. 1992;25:193-201.

8. Robinson DS, Rickels K, Feighner J, et al. Clinical effects of the 5-HT1A partial agonists in depression: a composite analysis of buspirone in the treatment of depression. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1990;10(3 suppl):67S-76S.

9. Rickels K, Athanasiou M, Robinson DS, et al. Evidence for efficacy and tolerability of vilazodone in the treatment of major depressive disorder: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(3):326-333.

10. Khan A, Cutler AJ, Kajdasz DK, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of vilazodone, a dual-acting serotonergic antidepressant, in the treatment of patients with MDD. Poster presented at: American Psychiatric Association Annual Meeting; New Orleans, LA; May 25, 2010.

11. Mittal MS, Kalia R, Preskorn SH. Vilazodone a 5-HT1A receptor partial agonist and serotonin reuptake pump inhibitor: what can be gleaned from its history and its clinical data? J Psychiatr Pract. In press.

12. Robinson D, Kajdasz D, Gallipoli S, et al. A one-year open-label study assessing the safety and tolerability of vilazodone in patients with MDD. Poster presented at: American Psychiatric Association Annual Meeting: New Orleans, LA; May 25, 2010.

13. Preskorn SH, Flockhart D. 2010 guide to psychiatric drug interactions. Primary Psychiatry. 2009;16(12):45-74.

In January 2011, the FDA approved vilazodone for the treatment of major depressive disorder (MDD) (Table 1).

Vilazodone was discovered by Merck KGaA in Germany.1 In February 2001, Merck KGaA licensed vilazodone to GlaxoSmithKline. In April 2003, GlaxoSmithKline returned all rights to Merck KGaA because phase IIb clinical data did not support progression to phase III clinical trials. In September 2004, Genaissance Pharmaceuticals Inc. acquired an exclusive worldwide license from Merck KGaA to develop and commercialize vilazodone for depression treatment.2 Subsequently, Clinical Data Inc. acquired Genaissance Pharmaceuticals Inc., including vilazodone, and proceeded with 2 phase III trials and a large safety trial resulting in FDA approval. In February 2011, Forest Laboratories Inc. acquired Clinical Data Inc. and will launch vilazodone in second quarter of 2011.

Table 1

Vilazodone: Fast facts

| Brand name: Viibryd |

| Class: Serotonin reuptake inhibitor and 5-HT1A receptor partial agonist |

| Indication: Major depressive disorder |

| Approval date: January 24, 2011 |

| Availability date: Second quarter of 2011 |

| Manufacturer: Forest Laboratories Inc. |

| Dosage forms: 10 mg, 20 mg, and 40 mg tablets |

| Starting dose: 10 mg/d |

| Target dose: 40 mg/d |

How it works

Similar to all antidepressants, vilazodone’s mechanism of action is not fully understood, but is thought to be related to its inhibition of serotonin (ie, 5-HT) reuptake and partial agonism of 5-HT1A receptors.3 Vilazodone technically is not a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) because it has greater affinity for the 5-HT1A receptor (0.2nM) than it does for the 5-HT reuptake pump (0.5nM).4

Vilazodone was developed based on the theory that inhibition of 5-HT1A autoreceptor inhibition was responsible for SSRIs’ delayed (approximately 2 weeks) onset of antidepressant efficacy. Briefly, this theory is as follows: In humans, 5-HT1A receptors are primarily presynaptic in the raphe nuclei and postsynaptic 5-HT1A receptors predominate in the neocortex and limbic regions of the brain.5 Presynaptically, 5-HT1A are autoreceptors, ie, serotonin stimulation of these receptors results in inhibition of firing of 5-HT neurons, while postsynaptically they may be involved in downstream serotonergic effects such as sexual function.5 SSRIs are thought to work as antidepressants by increasing 5-HT concentration in the synapse but their initial effect is to turn off 5-HT neuronal firing as a result of increased concentration of 5-HT at the presynaptic 5-HT1A autoreceptor. Subsequently, these 5-HT1A autoreceptors subsensitize such that 5-HT neuronal firing rate returns to normal. The time course for this subsensitization parallels the onset of SSRI antidepressant efficacy. For several years, efforts have been made to antagonize the 5-HT1A presynaptic autoreceptors as a means of potentially shortening SSRIs’ onset of efficacy.6-8

Pharmacokinetics

Vilazodone is absorbed in the gastrointestinal tract and reaches peak concentration at a median of 4 to 5 hours. Its bioavailability increases when taken with food such that Cmax (maximum concentration) is increased by 147% to 160%, and area under the curve is increased by 64% to 85%. Its absolute bioavailability in the presence of food is 72%.4 In systemic circulation, the drug is 96% to 99% protein-bound.3 Vilazodone is eliminated primarily through cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4 metabolism in the liver.3

Terminal half-life of vilazodone is 25 hours. In general, steady state is achieved in 4 to 5 times the half-life at a stable dose. However, dosing guidelines for vilazodone recommend titration over 2 weeks to achieve a target of 40 mg/d. Thus, steady state will not be achieved until the patient has been on the stable target dose for approximately 2.5 weeks.3

Efficacy

Vilazodone’ efficacy for MDD treatment was established in 2 pivotal 8-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, but not active-controlled, trials (Table 2).9-11 Study participants were outpatients age 18 to 65 who met DSM-IV-TR criteria for MDD. Patients were required to have a 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D-17) score >22 and a HAM-D-17 item 1 (depressed mood) score >2.

In the first clinical trial, 410 patients were randomly assigned to vilazodone or placebo. In the vilazodone group, patients were started on 10 mg/d for 1 week, titrated to 20 mg/d for a second week, and then 40 mg/d for the remainder of the study. At week 8, the mean change from baseline on the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS), HAM-D-17, Clinical Global Impression-Improvement scale (CGI-I), Clinical Global Impression-Severity scale (CGI-S), and Hamilton Anxiety scale (HAM-A) was statistically greater with vilazodone than placebo (P <.05).9 Compared with placebo, vilazodone-treated patients showed a statistically significant (P <. 05) improvement in MADRS and HAM-D-17 scores at week 1. Approximately 12% more vilazodone-treated patients achieved response (defined as ≥50% decrease in total score at end of treatment) on the primary efficacy measure, which was MADRS (40.4% vs 28.1%, P=.007), and the 2 secondary efficacy measures, which were HAM-D-17 (44.4% vs 32.7%, P =.011) and CGI-I (48.0 vs 32.7, P =.001). Remission rates (MADRS <10) were not reported in this study, but the authors stated that there was no statistical difference in remission rates between the vilazodone and placebo groups.9