User login

#ConsentObtained – Patient Privacy in the Age of Social Media

“I have a rare dermatologic disorder. In medical school, I read a case report about treatment for my disorder. I was surprised to read my history and shocked to see my childhood face staring back at me in the figures section. The case report was written when I was a child and my parents had signed a consent form that stated my case and images could be used for ‘educational purposes.’ My parents were not notified that my images and case were published. While surprised and shocked to read my history and see images of myself in a medical journal, I trusted my privacy was protected because the journal would only be read by medical professionals. Fast-forward to today, I do not know how comfortable I would feel if my images were shared on social media, with the potential to reach viewers outside of the medical community. If I were a parent, I would feel even more uncomfortable with reading my child’s case on social media, let alone viewing an image of my child.”

—A.K.

Social media has become ingrained in our society, including many facets of our professional life. According to a 2019 report from the Pew Research Center, 73% of Americans use social media.1 The PricewaterhouseCoopers Health Institute found 90% of physicians use social media personally, and 65% use it professionally.2

As the Pediatric Hospital Medicine Conference Social Media Cochairs (2015-2019), we managed official profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram. We also crafted and executed the conference’s social media strategy. During that time, we witnessed a substantial increase in the presence of physicians on social media with little available guidance on best practices. Here, we discuss patient privacy challenges with social media as well as solutions to address them.

PATIENT PRIVACY CHALLENGES ON SOCIAL MEDIA

In 2011, Greyson et al surveyed executive directors of all medical and osteopathic boards in the United States for online professionalism violations.3 Online violations of patient confidentiality were reported by over 55% of the 48 boards that responded. Of those, 10% reported more than three violations of patient confidentiality, and no actions were initially taken in 25% of violations. While these violations were not specific to social media, they highlight online patient confidentiality breaches are occurring, even if they are not being disciplined.

Several organizations, including the American Medical Association (AMA), the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), and the American College of Physicians (ACP) have developed social media guidelines.4-6 However, these guidelines are not always followed. Fanti Silva and Colleoni studied surgeons and surgical trainees at a university hospital and found that social media guidelines were unknown to 100% of medical students, 85% of residents, and 78% of attendings.7 They also found that 53% of medical students, 86% of residents, and 32% of attendings were sharing patient information on social media despite hospitals’ privacy policies.

Social media provides forums for physicians to discuss cases and share experiences in hopes of educating others. These posts may include images or videos. Unfortunately, sharing specific clinical information or improperly deidentifying images may lead to the unintentional identification of patients.8 Some information may not be protected by the US Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) Privacy Rule, and may lead to patient identification when shared.9 Despite disguising or omitting demographics, encounter information, or unique characteristics of the presentation, some physicians—not the posting physician—believe patients may still be able to identify their cases.8

Physicians who try to be mindful of patient privacy concerns face challenges with social media platforms themselves. For example, Facebook allows users to create Closed Groups (CGs) in which the group’s “administrators” can grant “admission” to users wishing to join the conversation (eg, Physician Moms Group). These groups are left to govern themselves and comply only with Facebook’s safety standards. The Society of Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons used Facebook’s CGs to create a forum for education, consultation, and collaboration for society members. Group administrators grant admittance only after group members have agreed to HIPAA compliance. Group members may then share deidentified images and videos when discussing cases.10 However, Facebook’s Terms of Service states the company has “a non-exclusive, transferable, sub-licensable, royalty-free, worldwide license to host, use, distribute, modify, run, copy, publicly perform or display, translate, and create derivative works” of the content based on the privacy settings of the individual posting the content.11 Therefore, these CGs may create a false sense of security because many members may assume the content of the CGs are private. Twitter’s Terms of Service are similar to Facebook’s, but state that users should have “obtained, all rights, licenses, consents, permissions, power and/or authority necessary to grant the rights . . . for any Content that is posted.”12 If a patient’s deidentified story is posted on Twitter, the posting physician may be violating Twitter’s Terms of Service by not obtaining the patient’s consent/permission or explicitly stating so in their tweet.

SOLUTIONS

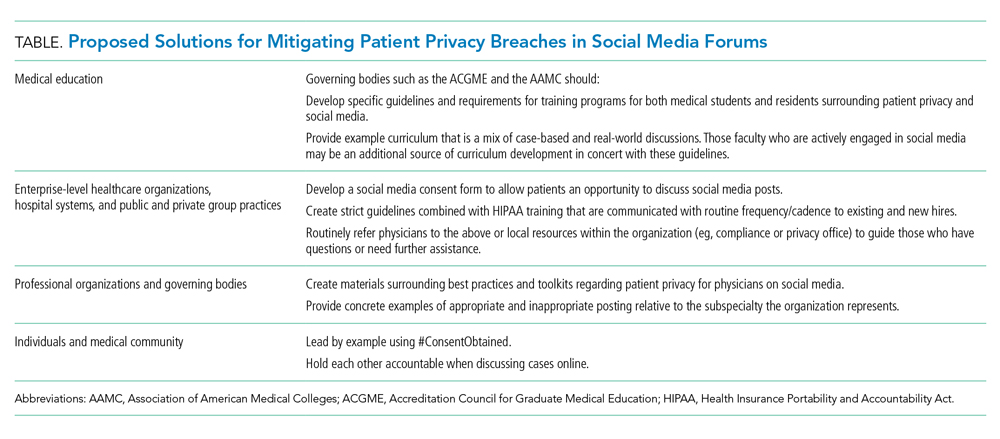

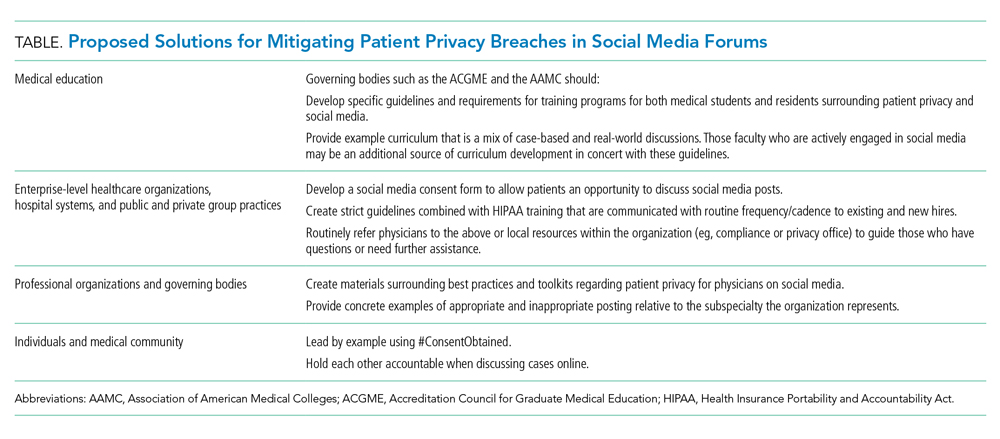

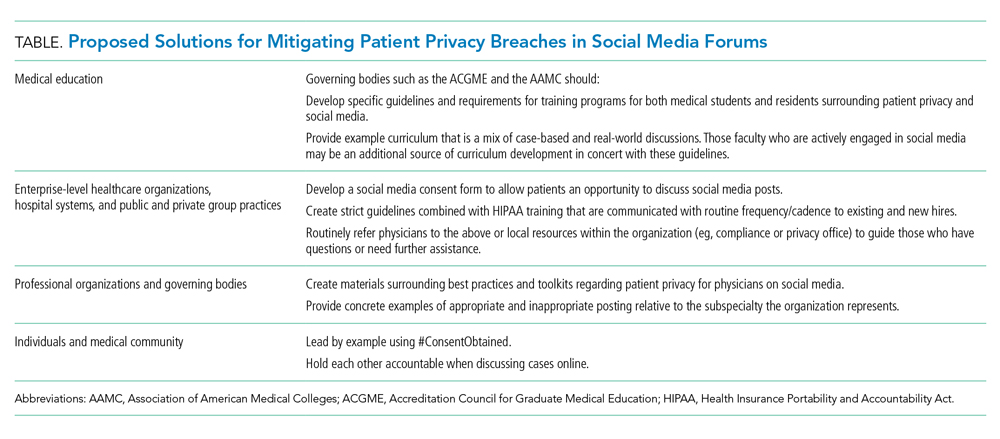

In light of the challenges faced when posting medical cases on social media, we propose several solutions that the medical community should adopt to mitigate and limit any potential breaches to patient privacy. These are summarized in the Table.

Medical Education

Many medical students and residents are active on social media. However, not all are formally educated on appropriate engagement online and social media etiquette. A recent article from the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) highlights how this “curriculum” is missing from many medical schools and residency programs.13 There are plenty of resources outlining how to maintain professionalism on social media in a general sense, but maintaining patient privacy usually is not concretely explored. Consequently, many programs are left to individually provide this education without firm guidance on best practices. We propose that governing organizations for medical education such as the AAMC and Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education have formal requirements, guidelines, and example curriculum on educating trainees on best practices for social media activity.

Health Organization Consent Forms

Healthcare organizations have a responsibility to protect patient privacy. We propose that healthcare organizations should develop independent social media consent forms that address sharing of images, videos, and cases. This separate social media consent form would allow patients/guardians to discuss whether they want their information shared. Some organizations have taken this step and developed consent forms for sharing deidentified posts on HIPAA-compliant CGs.10 However, it is still far from standard of practice for a healthcare organization to develop a separate consent form addressing the educational uses of sharing cases on social media. The Federation of State Medical Board’s (FSMB) Social Media and Electronic Communications policy endorses obtaining “express written consent” from patients.14 The policy states that “the physician must adequately explain the risks . . . for consent to be fully informed.” The FSMB policy also reminds readers that any social media post is permanent, even after it has been deleted.

Professional Organizations

Many professional organizations have acknowledged the growing role of social media in the professional lives of medical providers and have adopted policy statements and guidelines to address social media use. However, these guidelines are quite variable. All professional organizations should take the time to clarify and discuss the nuances of patient privacy on social media in their guidelines. For example, the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology statement warns members that “any public communication about work-related clinical events may violate . . . privacy” and posting of deidentified general events “may be traced, through public vital statistics data, to a specific patient or hospital” directly violating HIPAA.15 In comparison, the AAP and ACP’s social media guidelines and toolkits fall short when discussing how to maintain patient privacy specifically. Within these toolkits and guidelines, there is no explicit guidance or discussion about maintaining patient privacy with the use of case examples or best practices.5,6 As physicians on social media, we should be aware of these variable policy statements and guidelines from our professional organizations. Even further, as active members of our professional organizations, we should call on them to update their guidelines to increase details regarding the nuances of patient privacy.

#ConsentObtained

When a case is posted on social media, it should be the posting physician’s responsibility to clearly state in the initial post that consent was obtained. To simplify the process, we propose the use of the hashtag, #ConsentObtained, to easily identify that assurances were made to protect the patient. Moreover, we encourage our physician colleagues to remind others to explicitly state if consent was obtained if it is not mentioned. The AMA’s code of ethics states that if physicians read posts that they feel are unprofessional, then those physicians “have a responsibility to bring that content to the attention of the individual, so that he or she can remove it and/or take other appropriate actions.”4 Therefore, we encourage all readers of social media posts to ensure that posts include #ConsentObtained or otherwise clearly state that patient permission was obtained. If the hashtag or verbiage is not seen, then it is the reader’s responsibility to contact the posting physician. The AMA’s code of ethics also recommends physicians to “report the matter to appropriate authorities” if the individual posting “does not take appropriate actions.”4 While we realize that verification of consent being obtained may be virtually impossible online, we hope that, as physicians, we hold patient privacy to the highest regard and would never use this hashtag inappropriately. Lastly, it’s important to remember that removing/deleting a post may delete it from the platform, but that post and its contents are not deleted from the internet and may be accessed through another site.

CONCLUSION

Social media has allowed the healthcare community to develop a voice for individuals and communities; it has allowed for collaboration, open discussion, and education. However, it also asks us to reevaluate the professional ethics and rules we have abided for decades with regard to keeping patient health information safe. We must be proactive to develop solutions regarding patient privacy as our social media presence continues to grow.

Disclosure

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

1. Perrin A, Anderson M. Share of U.S. adults using social media, including Facebook, is mostly unchanged since 2018. Pew Research Center. April 10, 2019. Accessed September 9, 2019. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/04/10/share-of-u-s-adults-using-social-media-including-facebook-is-mostly-unchanged-since-2018

2. Modahl M, Tompsett L, Moorhead T. Doctors, Patients, and Social Media.QuantiaMD. September 2011. Accessed September 9, 2019. http://www.quantiamd.com/q-qcp/social_media.pdf

3. Greysen SR, Chretien KC, Kind T, Young A, Gross CP. Physician violations of online professionalism and disciplinary actions: a national survey of state medical boards. JAMA. 2012;307(11):1141-1142. https://.org/10.1001/jama.2012.330

4. Code of Medical Ethics Opinion 2.3.2. American Medical Associaiton. November 14, 2016. Accessed August 18, 2019. https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/ethics/professionalism-use-social-media

5. Social Media Toolkit. American Academy of Pediatrics. Accessed January 14, 2020. https://www.aap.org/en-us/advocacy-and-policy/aap-health-initiatives/Pages/Media-and-Children.aspx

6. Farnan JM, Snyder Sulmasy L, Worster BK, et al. Online medical professionalism: patient and public relationships: policy statement from the American College of Physicians and the Federation of State Medical Boards. Annal Intern Med. 2013;158:620-627. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-158-8-201304160-00100

7. Fanti Silva DA, Colleoni R. Patient’s privacy violation on social media in the surgical area. Am Surg. 2018;84(12):1900-1905.

8. Cifu AS, Vandross AL, Prasad V. Case reports in the age of Twitter. Am J Med. 2019;132(10):e725-e726. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2019.03.044

9. OCR Privacy Brief: Summary of the HIPAA Privacy Rule. Department of Health & Human Services; 2003. Accessed August 18, 2019. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/privacysummary.pdf

10. Bittner JG 4th, Logghe HJ, Kane ED, et al. A Society of Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES) statement on closed social media (Facebook) groups for clinical education and consultation: issues of informed consent, patient privacy, and surgeon protection. Surg Endosc. 2019;33(1):1-7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-018-6569-2

11. Terms of Service. Facebook. 2019. Accessed August 18, 2019. https://www.facebook.com/terms.php

12. Terms of Service. Twitter. 2020. Accessed January 3, 2020. https://twitter.com/en/tos

13. Kalter L. The social media dilemma. Special to AAMC News. Mar 4, 2019. Accessed January 2, 2020. https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/social-media-dilemma

14. Social Media and Electronic Communications; Report and Recommendations of the FSMB Ethics and Professionalism Committee; Adopted as policy by the Federation of State Medical Boards April 2019. Federation of State Medical Boards. Accessed August 18, 2019. http://www.fsmb.org/siteassets/advocacy/policies/social-media-and-electronic-communications.pdf

15. Professional use of digital and social media: ACOG Committee Opinion, Number 791. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134(4):e117-e121. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000003451

“I have a rare dermatologic disorder. In medical school, I read a case report about treatment for my disorder. I was surprised to read my history and shocked to see my childhood face staring back at me in the figures section. The case report was written when I was a child and my parents had signed a consent form that stated my case and images could be used for ‘educational purposes.’ My parents were not notified that my images and case were published. While surprised and shocked to read my history and see images of myself in a medical journal, I trusted my privacy was protected because the journal would only be read by medical professionals. Fast-forward to today, I do not know how comfortable I would feel if my images were shared on social media, with the potential to reach viewers outside of the medical community. If I were a parent, I would feel even more uncomfortable with reading my child’s case on social media, let alone viewing an image of my child.”

—A.K.

Social media has become ingrained in our society, including many facets of our professional life. According to a 2019 report from the Pew Research Center, 73% of Americans use social media.1 The PricewaterhouseCoopers Health Institute found 90% of physicians use social media personally, and 65% use it professionally.2

As the Pediatric Hospital Medicine Conference Social Media Cochairs (2015-2019), we managed official profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram. We also crafted and executed the conference’s social media strategy. During that time, we witnessed a substantial increase in the presence of physicians on social media with little available guidance on best practices. Here, we discuss patient privacy challenges with social media as well as solutions to address them.

PATIENT PRIVACY CHALLENGES ON SOCIAL MEDIA

In 2011, Greyson et al surveyed executive directors of all medical and osteopathic boards in the United States for online professionalism violations.3 Online violations of patient confidentiality were reported by over 55% of the 48 boards that responded. Of those, 10% reported more than three violations of patient confidentiality, and no actions were initially taken in 25% of violations. While these violations were not specific to social media, they highlight online patient confidentiality breaches are occurring, even if they are not being disciplined.

Several organizations, including the American Medical Association (AMA), the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), and the American College of Physicians (ACP) have developed social media guidelines.4-6 However, these guidelines are not always followed. Fanti Silva and Colleoni studied surgeons and surgical trainees at a university hospital and found that social media guidelines were unknown to 100% of medical students, 85% of residents, and 78% of attendings.7 They also found that 53% of medical students, 86% of residents, and 32% of attendings were sharing patient information on social media despite hospitals’ privacy policies.

Social media provides forums for physicians to discuss cases and share experiences in hopes of educating others. These posts may include images or videos. Unfortunately, sharing specific clinical information or improperly deidentifying images may lead to the unintentional identification of patients.8 Some information may not be protected by the US Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) Privacy Rule, and may lead to patient identification when shared.9 Despite disguising or omitting demographics, encounter information, or unique characteristics of the presentation, some physicians—not the posting physician—believe patients may still be able to identify their cases.8

Physicians who try to be mindful of patient privacy concerns face challenges with social media platforms themselves. For example, Facebook allows users to create Closed Groups (CGs) in which the group’s “administrators” can grant “admission” to users wishing to join the conversation (eg, Physician Moms Group). These groups are left to govern themselves and comply only with Facebook’s safety standards. The Society of Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons used Facebook’s CGs to create a forum for education, consultation, and collaboration for society members. Group administrators grant admittance only after group members have agreed to HIPAA compliance. Group members may then share deidentified images and videos when discussing cases.10 However, Facebook’s Terms of Service states the company has “a non-exclusive, transferable, sub-licensable, royalty-free, worldwide license to host, use, distribute, modify, run, copy, publicly perform or display, translate, and create derivative works” of the content based on the privacy settings of the individual posting the content.11 Therefore, these CGs may create a false sense of security because many members may assume the content of the CGs are private. Twitter’s Terms of Service are similar to Facebook’s, but state that users should have “obtained, all rights, licenses, consents, permissions, power and/or authority necessary to grant the rights . . . for any Content that is posted.”12 If a patient’s deidentified story is posted on Twitter, the posting physician may be violating Twitter’s Terms of Service by not obtaining the patient’s consent/permission or explicitly stating so in their tweet.

SOLUTIONS

In light of the challenges faced when posting medical cases on social media, we propose several solutions that the medical community should adopt to mitigate and limit any potential breaches to patient privacy. These are summarized in the Table.

Medical Education

Many medical students and residents are active on social media. However, not all are formally educated on appropriate engagement online and social media etiquette. A recent article from the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) highlights how this “curriculum” is missing from many medical schools and residency programs.13 There are plenty of resources outlining how to maintain professionalism on social media in a general sense, but maintaining patient privacy usually is not concretely explored. Consequently, many programs are left to individually provide this education without firm guidance on best practices. We propose that governing organizations for medical education such as the AAMC and Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education have formal requirements, guidelines, and example curriculum on educating trainees on best practices for social media activity.

Health Organization Consent Forms

Healthcare organizations have a responsibility to protect patient privacy. We propose that healthcare organizations should develop independent social media consent forms that address sharing of images, videos, and cases. This separate social media consent form would allow patients/guardians to discuss whether they want their information shared. Some organizations have taken this step and developed consent forms for sharing deidentified posts on HIPAA-compliant CGs.10 However, it is still far from standard of practice for a healthcare organization to develop a separate consent form addressing the educational uses of sharing cases on social media. The Federation of State Medical Board’s (FSMB) Social Media and Electronic Communications policy endorses obtaining “express written consent” from patients.14 The policy states that “the physician must adequately explain the risks . . . for consent to be fully informed.” The FSMB policy also reminds readers that any social media post is permanent, even after it has been deleted.

Professional Organizations

Many professional organizations have acknowledged the growing role of social media in the professional lives of medical providers and have adopted policy statements and guidelines to address social media use. However, these guidelines are quite variable. All professional organizations should take the time to clarify and discuss the nuances of patient privacy on social media in their guidelines. For example, the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology statement warns members that “any public communication about work-related clinical events may violate . . . privacy” and posting of deidentified general events “may be traced, through public vital statistics data, to a specific patient or hospital” directly violating HIPAA.15 In comparison, the AAP and ACP’s social media guidelines and toolkits fall short when discussing how to maintain patient privacy specifically. Within these toolkits and guidelines, there is no explicit guidance or discussion about maintaining patient privacy with the use of case examples or best practices.5,6 As physicians on social media, we should be aware of these variable policy statements and guidelines from our professional organizations. Even further, as active members of our professional organizations, we should call on them to update their guidelines to increase details regarding the nuances of patient privacy.

#ConsentObtained

When a case is posted on social media, it should be the posting physician’s responsibility to clearly state in the initial post that consent was obtained. To simplify the process, we propose the use of the hashtag, #ConsentObtained, to easily identify that assurances were made to protect the patient. Moreover, we encourage our physician colleagues to remind others to explicitly state if consent was obtained if it is not mentioned. The AMA’s code of ethics states that if physicians read posts that they feel are unprofessional, then those physicians “have a responsibility to bring that content to the attention of the individual, so that he or she can remove it and/or take other appropriate actions.”4 Therefore, we encourage all readers of social media posts to ensure that posts include #ConsentObtained or otherwise clearly state that patient permission was obtained. If the hashtag or verbiage is not seen, then it is the reader’s responsibility to contact the posting physician. The AMA’s code of ethics also recommends physicians to “report the matter to appropriate authorities” if the individual posting “does not take appropriate actions.”4 While we realize that verification of consent being obtained may be virtually impossible online, we hope that, as physicians, we hold patient privacy to the highest regard and would never use this hashtag inappropriately. Lastly, it’s important to remember that removing/deleting a post may delete it from the platform, but that post and its contents are not deleted from the internet and may be accessed through another site.

CONCLUSION

Social media has allowed the healthcare community to develop a voice for individuals and communities; it has allowed for collaboration, open discussion, and education. However, it also asks us to reevaluate the professional ethics and rules we have abided for decades with regard to keeping patient health information safe. We must be proactive to develop solutions regarding patient privacy as our social media presence continues to grow.

Disclosure

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

“I have a rare dermatologic disorder. In medical school, I read a case report about treatment for my disorder. I was surprised to read my history and shocked to see my childhood face staring back at me in the figures section. The case report was written when I was a child and my parents had signed a consent form that stated my case and images could be used for ‘educational purposes.’ My parents were not notified that my images and case were published. While surprised and shocked to read my history and see images of myself in a medical journal, I trusted my privacy was protected because the journal would only be read by medical professionals. Fast-forward to today, I do not know how comfortable I would feel if my images were shared on social media, with the potential to reach viewers outside of the medical community. If I were a parent, I would feel even more uncomfortable with reading my child’s case on social media, let alone viewing an image of my child.”

—A.K.

Social media has become ingrained in our society, including many facets of our professional life. According to a 2019 report from the Pew Research Center, 73% of Americans use social media.1 The PricewaterhouseCoopers Health Institute found 90% of physicians use social media personally, and 65% use it professionally.2

As the Pediatric Hospital Medicine Conference Social Media Cochairs (2015-2019), we managed official profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram. We also crafted and executed the conference’s social media strategy. During that time, we witnessed a substantial increase in the presence of physicians on social media with little available guidance on best practices. Here, we discuss patient privacy challenges with social media as well as solutions to address them.

PATIENT PRIVACY CHALLENGES ON SOCIAL MEDIA

In 2011, Greyson et al surveyed executive directors of all medical and osteopathic boards in the United States for online professionalism violations.3 Online violations of patient confidentiality were reported by over 55% of the 48 boards that responded. Of those, 10% reported more than three violations of patient confidentiality, and no actions were initially taken in 25% of violations. While these violations were not specific to social media, they highlight online patient confidentiality breaches are occurring, even if they are not being disciplined.

Several organizations, including the American Medical Association (AMA), the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), and the American College of Physicians (ACP) have developed social media guidelines.4-6 However, these guidelines are not always followed. Fanti Silva and Colleoni studied surgeons and surgical trainees at a university hospital and found that social media guidelines were unknown to 100% of medical students, 85% of residents, and 78% of attendings.7 They also found that 53% of medical students, 86% of residents, and 32% of attendings were sharing patient information on social media despite hospitals’ privacy policies.

Social media provides forums for physicians to discuss cases and share experiences in hopes of educating others. These posts may include images or videos. Unfortunately, sharing specific clinical information or improperly deidentifying images may lead to the unintentional identification of patients.8 Some information may not be protected by the US Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) Privacy Rule, and may lead to patient identification when shared.9 Despite disguising or omitting demographics, encounter information, or unique characteristics of the presentation, some physicians—not the posting physician—believe patients may still be able to identify their cases.8

Physicians who try to be mindful of patient privacy concerns face challenges with social media platforms themselves. For example, Facebook allows users to create Closed Groups (CGs) in which the group’s “administrators” can grant “admission” to users wishing to join the conversation (eg, Physician Moms Group). These groups are left to govern themselves and comply only with Facebook’s safety standards. The Society of Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons used Facebook’s CGs to create a forum for education, consultation, and collaboration for society members. Group administrators grant admittance only after group members have agreed to HIPAA compliance. Group members may then share deidentified images and videos when discussing cases.10 However, Facebook’s Terms of Service states the company has “a non-exclusive, transferable, sub-licensable, royalty-free, worldwide license to host, use, distribute, modify, run, copy, publicly perform or display, translate, and create derivative works” of the content based on the privacy settings of the individual posting the content.11 Therefore, these CGs may create a false sense of security because many members may assume the content of the CGs are private. Twitter’s Terms of Service are similar to Facebook’s, but state that users should have “obtained, all rights, licenses, consents, permissions, power and/or authority necessary to grant the rights . . . for any Content that is posted.”12 If a patient’s deidentified story is posted on Twitter, the posting physician may be violating Twitter’s Terms of Service by not obtaining the patient’s consent/permission or explicitly stating so in their tweet.

SOLUTIONS

In light of the challenges faced when posting medical cases on social media, we propose several solutions that the medical community should adopt to mitigate and limit any potential breaches to patient privacy. These are summarized in the Table.

Medical Education

Many medical students and residents are active on social media. However, not all are formally educated on appropriate engagement online and social media etiquette. A recent article from the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) highlights how this “curriculum” is missing from many medical schools and residency programs.13 There are plenty of resources outlining how to maintain professionalism on social media in a general sense, but maintaining patient privacy usually is not concretely explored. Consequently, many programs are left to individually provide this education without firm guidance on best practices. We propose that governing organizations for medical education such as the AAMC and Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education have formal requirements, guidelines, and example curriculum on educating trainees on best practices for social media activity.

Health Organization Consent Forms

Healthcare organizations have a responsibility to protect patient privacy. We propose that healthcare organizations should develop independent social media consent forms that address sharing of images, videos, and cases. This separate social media consent form would allow patients/guardians to discuss whether they want their information shared. Some organizations have taken this step and developed consent forms for sharing deidentified posts on HIPAA-compliant CGs.10 However, it is still far from standard of practice for a healthcare organization to develop a separate consent form addressing the educational uses of sharing cases on social media. The Federation of State Medical Board’s (FSMB) Social Media and Electronic Communications policy endorses obtaining “express written consent” from patients.14 The policy states that “the physician must adequately explain the risks . . . for consent to be fully informed.” The FSMB policy also reminds readers that any social media post is permanent, even after it has been deleted.

Professional Organizations

Many professional organizations have acknowledged the growing role of social media in the professional lives of medical providers and have adopted policy statements and guidelines to address social media use. However, these guidelines are quite variable. All professional organizations should take the time to clarify and discuss the nuances of patient privacy on social media in their guidelines. For example, the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology statement warns members that “any public communication about work-related clinical events may violate . . . privacy” and posting of deidentified general events “may be traced, through public vital statistics data, to a specific patient or hospital” directly violating HIPAA.15 In comparison, the AAP and ACP’s social media guidelines and toolkits fall short when discussing how to maintain patient privacy specifically. Within these toolkits and guidelines, there is no explicit guidance or discussion about maintaining patient privacy with the use of case examples or best practices.5,6 As physicians on social media, we should be aware of these variable policy statements and guidelines from our professional organizations. Even further, as active members of our professional organizations, we should call on them to update their guidelines to increase details regarding the nuances of patient privacy.

#ConsentObtained

When a case is posted on social media, it should be the posting physician’s responsibility to clearly state in the initial post that consent was obtained. To simplify the process, we propose the use of the hashtag, #ConsentObtained, to easily identify that assurances were made to protect the patient. Moreover, we encourage our physician colleagues to remind others to explicitly state if consent was obtained if it is not mentioned. The AMA’s code of ethics states that if physicians read posts that they feel are unprofessional, then those physicians “have a responsibility to bring that content to the attention of the individual, so that he or she can remove it and/or take other appropriate actions.”4 Therefore, we encourage all readers of social media posts to ensure that posts include #ConsentObtained or otherwise clearly state that patient permission was obtained. If the hashtag or verbiage is not seen, then it is the reader’s responsibility to contact the posting physician. The AMA’s code of ethics also recommends physicians to “report the matter to appropriate authorities” if the individual posting “does not take appropriate actions.”4 While we realize that verification of consent being obtained may be virtually impossible online, we hope that, as physicians, we hold patient privacy to the highest regard and would never use this hashtag inappropriately. Lastly, it’s important to remember that removing/deleting a post may delete it from the platform, but that post and its contents are not deleted from the internet and may be accessed through another site.

CONCLUSION

Social media has allowed the healthcare community to develop a voice for individuals and communities; it has allowed for collaboration, open discussion, and education. However, it also asks us to reevaluate the professional ethics and rules we have abided for decades with regard to keeping patient health information safe. We must be proactive to develop solutions regarding patient privacy as our social media presence continues to grow.

Disclosure

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

1. Perrin A, Anderson M. Share of U.S. adults using social media, including Facebook, is mostly unchanged since 2018. Pew Research Center. April 10, 2019. Accessed September 9, 2019. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/04/10/share-of-u-s-adults-using-social-media-including-facebook-is-mostly-unchanged-since-2018

2. Modahl M, Tompsett L, Moorhead T. Doctors, Patients, and Social Media.QuantiaMD. September 2011. Accessed September 9, 2019. http://www.quantiamd.com/q-qcp/social_media.pdf

3. Greysen SR, Chretien KC, Kind T, Young A, Gross CP. Physician violations of online professionalism and disciplinary actions: a national survey of state medical boards. JAMA. 2012;307(11):1141-1142. https://.org/10.1001/jama.2012.330

4. Code of Medical Ethics Opinion 2.3.2. American Medical Associaiton. November 14, 2016. Accessed August 18, 2019. https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/ethics/professionalism-use-social-media

5. Social Media Toolkit. American Academy of Pediatrics. Accessed January 14, 2020. https://www.aap.org/en-us/advocacy-and-policy/aap-health-initiatives/Pages/Media-and-Children.aspx

6. Farnan JM, Snyder Sulmasy L, Worster BK, et al. Online medical professionalism: patient and public relationships: policy statement from the American College of Physicians and the Federation of State Medical Boards. Annal Intern Med. 2013;158:620-627. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-158-8-201304160-00100

7. Fanti Silva DA, Colleoni R. Patient’s privacy violation on social media in the surgical area. Am Surg. 2018;84(12):1900-1905.

8. Cifu AS, Vandross AL, Prasad V. Case reports in the age of Twitter. Am J Med. 2019;132(10):e725-e726. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2019.03.044

9. OCR Privacy Brief: Summary of the HIPAA Privacy Rule. Department of Health & Human Services; 2003. Accessed August 18, 2019. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/privacysummary.pdf

10. Bittner JG 4th, Logghe HJ, Kane ED, et al. A Society of Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES) statement on closed social media (Facebook) groups for clinical education and consultation: issues of informed consent, patient privacy, and surgeon protection. Surg Endosc. 2019;33(1):1-7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-018-6569-2

11. Terms of Service. Facebook. 2019. Accessed August 18, 2019. https://www.facebook.com/terms.php

12. Terms of Service. Twitter. 2020. Accessed January 3, 2020. https://twitter.com/en/tos

13. Kalter L. The social media dilemma. Special to AAMC News. Mar 4, 2019. Accessed January 2, 2020. https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/social-media-dilemma

14. Social Media and Electronic Communications; Report and Recommendations of the FSMB Ethics and Professionalism Committee; Adopted as policy by the Federation of State Medical Boards April 2019. Federation of State Medical Boards. Accessed August 18, 2019. http://www.fsmb.org/siteassets/advocacy/policies/social-media-and-electronic-communications.pdf

15. Professional use of digital and social media: ACOG Committee Opinion, Number 791. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134(4):e117-e121. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000003451

1. Perrin A, Anderson M. Share of U.S. adults using social media, including Facebook, is mostly unchanged since 2018. Pew Research Center. April 10, 2019. Accessed September 9, 2019. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/04/10/share-of-u-s-adults-using-social-media-including-facebook-is-mostly-unchanged-since-2018

2. Modahl M, Tompsett L, Moorhead T. Doctors, Patients, and Social Media.QuantiaMD. September 2011. Accessed September 9, 2019. http://www.quantiamd.com/q-qcp/social_media.pdf

3. Greysen SR, Chretien KC, Kind T, Young A, Gross CP. Physician violations of online professionalism and disciplinary actions: a national survey of state medical boards. JAMA. 2012;307(11):1141-1142. https://.org/10.1001/jama.2012.330

4. Code of Medical Ethics Opinion 2.3.2. American Medical Associaiton. November 14, 2016. Accessed August 18, 2019. https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/ethics/professionalism-use-social-media

5. Social Media Toolkit. American Academy of Pediatrics. Accessed January 14, 2020. https://www.aap.org/en-us/advocacy-and-policy/aap-health-initiatives/Pages/Media-and-Children.aspx

6. Farnan JM, Snyder Sulmasy L, Worster BK, et al. Online medical professionalism: patient and public relationships: policy statement from the American College of Physicians and the Federation of State Medical Boards. Annal Intern Med. 2013;158:620-627. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-158-8-201304160-00100

7. Fanti Silva DA, Colleoni R. Patient’s privacy violation on social media in the surgical area. Am Surg. 2018;84(12):1900-1905.

8. Cifu AS, Vandross AL, Prasad V. Case reports in the age of Twitter. Am J Med. 2019;132(10):e725-e726. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2019.03.044

9. OCR Privacy Brief: Summary of the HIPAA Privacy Rule. Department of Health & Human Services; 2003. Accessed August 18, 2019. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/privacysummary.pdf

10. Bittner JG 4th, Logghe HJ, Kane ED, et al. A Society of Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES) statement on closed social media (Facebook) groups for clinical education and consultation: issues of informed consent, patient privacy, and surgeon protection. Surg Endosc. 2019;33(1):1-7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-018-6569-2

11. Terms of Service. Facebook. 2019. Accessed August 18, 2019. https://www.facebook.com/terms.php

12. Terms of Service. Twitter. 2020. Accessed January 3, 2020. https://twitter.com/en/tos

13. Kalter L. The social media dilemma. Special to AAMC News. Mar 4, 2019. Accessed January 2, 2020. https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/social-media-dilemma

14. Social Media and Electronic Communications; Report and Recommendations of the FSMB Ethics and Professionalism Committee; Adopted as policy by the Federation of State Medical Boards April 2019. Federation of State Medical Boards. Accessed August 18, 2019. http://www.fsmb.org/siteassets/advocacy/policies/social-media-and-electronic-communications.pdf

15. Professional use of digital and social media: ACOG Committee Opinion, Number 791. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134(4):e117-e121. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000003451

© 2020 Society of Hospital Medicine

2.02 Core Skills: Communication

Introduction

The ability to communicate effectively is a core skill for all physicians. It is of particular importance for pediatric hospitalists, who may have more limited longitudinal relationships with patients. This skill is pivotal to clinical practice, as it helps to establish rapport and a therapeutic alliance with patients and the family/caregivers. Communication is delivered both verbally and nonverbally, and can be learned and improved with practice, as with any other technical or clinical proficiency. Pediatric hospitalists must demonstrate effective communication in a variety of settings, including direct patient care, interactions with colleagues, and trainee education. The most critical setting for effective communication is at the bedside, where a pediatric hospitalist must communicate key information clearly and efficiently to patients, the family/caregivers, and to the entire healthcare team.

Knowledge

Pediatric hospitalists should be able to:

- Define the components of effective expressive and receptive communication, such as introduction of team members and their roles, avoiding medical jargon, using calm tone, appropriate word choice and body language, and allowing adequate time for patient and family input.

- Identify personal values, biases, and relationships that may influence communication.

- Discuss the benefits of including the family/caregivers and others who are important to the patient in daily decision-making and long-term plan development.

- Describe the importance of listening carefully, followed by effective use of information obtained to form conclusions and guide interventions.

- List examples of common nonlistening behaviors to avoid, such as allowing distractions, asking unrelated questions, jumping to conclusions, interrupting the speaker, and failing to notice the speaker’s nonverbal language.

- Understand the inherent vulnerability patients and the family/caregivers may feel when hospitalized and how this can affect bedside communication with the care team.

- Describe the importance of considering the cultural factors and spiritual beliefs of patients and the family/caregivers when establishing a therapeutic relationship.

- Explain how vulnerabilities, life situations, limitations in activities of daily living, education, language, and other factors should each be considered and addressed when communicating with patients and the family/caregivers.

- Discuss methods to achieve a more favorable interchange when faced with agitated communicators, such as asking for behavior change, paraphrasing to diffuse emotion, pausing the interaction until all parties are able to participate productively, and others.

- Describe practices essential for effective communication of difficult information, including sitting down, expressing empathy, giving patients and the family/caregivers time to ask questions, maintaining a calm demeanor, and choosing a quiet, private location for the discussion.

- Describe components of effective written communication, including timing of clinical documentation, legibility, grammar, accuracy, disagreements in approaches to care, and documentation of clinical changes.

- Explain why effective communication is central to patient safety during handoffs and list evidence-based handoff tools for use within hospitalist groups and with other healthcare providers.

Skills

Pediatric hospitalists should be able to:

- Demonstrate command of a comprehensive array of expressive and receptive communication skills.

- Develop and implement effective plan for daily communication that is family-centered and models best practices in communication, such as sitting down, avoiding jargon, and addressing key patient/family concerns.

- Engage patients and the family/caregivers in shared decision-making regarding the child’s plan of care.

- Coordinate discussions with all clinical care team members (such as nurses, consultants, and others) to ensure a single clear message is given to patients, the family, and all caregivers for the child.

- Demonstrate closed-loop communication to improve patient safety and decrease communication errors.

- Participate in conflict resolution, both within the health care team and between team members and the family/caregivers when indicated.

- Identify when the use of interpreters for patients and the family/caregivers with limited English language proficiency is necessary and effectively integrate interpreters into the communication plan.

- Lead and facilitate a multidisciplinary care conference when applicable.

- Record concise, complete written documents that accurately and succinctly relay key patient information, while meeting expectations of external reviewing agencies and malpractice carriers.

- Develop clear and concise discharge instructions for patients and the family/caregivers.

- Communicate in a timely manner with a child’s primary care provider, incorporating information on the admission reason, hospital course, discharge diagnosis, discharge plan, and follow-up needs and recommendations.

Attitudes

Pediatric hospitalists should be able to:

- Acknowledge the importance of respecting the skills and contributions of all clinical and nonclinical providers involved in the care of patients.

- Realize the responsibility for promoting equitable interactions with patients and the family/caregivers, free from bias related to background, age, language, education level, race, or ethnicity.

- Exemplify professionalism in all communication.

- Seek opportunities to enhance communication skills.

Systems Organization and Improvement

In order to improve efficiency and quality within their organizations, pediatric hospitalists should:

- Collaborate with hospital administrators to improve medical record documentation systems by technical means.

- Lead, support, or assist in the development of hospital and system-wide educational programs to enhance communication skills and decrease communication-related errors.

- Work with hospital administration to establish or evaluate existing patient and family experience metrics to ultimately improve communication at the bedside.

- Lead, coordinate, or participate in activities to support effective communication methods for patients and the family/caregivers with limited English language proficiency.

1. Kahn MW. Etiquette Based Medicine. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(19):1988-1989. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp0801863.

2. Levetown M and the American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Bioethics. Communicating with children and families: from everyday interactions to skill in conveying distressing information. Pediatrics. 2008;121(5). e1441-1460. https://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/121/5/e1441.long. Accessed August 28, 2019.

3. Council on Children with Disabilities and Medical Home Implementation Project Advisory Committee. AAP Policy Statement: Patient- and family-centered care coordination: a framework for integrating care for children and youth across multiple systems. Pediatrics. 2014;133(5): e1451-1460. https://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/133/5/e1451.long. Accessed August 28, 2019.

Introduction

The ability to communicate effectively is a core skill for all physicians. It is of particular importance for pediatric hospitalists, who may have more limited longitudinal relationships with patients. This skill is pivotal to clinical practice, as it helps to establish rapport and a therapeutic alliance with patients and the family/caregivers. Communication is delivered both verbally and nonverbally, and can be learned and improved with practice, as with any other technical or clinical proficiency. Pediatric hospitalists must demonstrate effective communication in a variety of settings, including direct patient care, interactions with colleagues, and trainee education. The most critical setting for effective communication is at the bedside, where a pediatric hospitalist must communicate key information clearly and efficiently to patients, the family/caregivers, and to the entire healthcare team.

Knowledge

Pediatric hospitalists should be able to:

- Define the components of effective expressive and receptive communication, such as introduction of team members and their roles, avoiding medical jargon, using calm tone, appropriate word choice and body language, and allowing adequate time for patient and family input.

- Identify personal values, biases, and relationships that may influence communication.

- Discuss the benefits of including the family/caregivers and others who are important to the patient in daily decision-making and long-term plan development.

- Describe the importance of listening carefully, followed by effective use of information obtained to form conclusions and guide interventions.

- List examples of common nonlistening behaviors to avoid, such as allowing distractions, asking unrelated questions, jumping to conclusions, interrupting the speaker, and failing to notice the speaker’s nonverbal language.

- Understand the inherent vulnerability patients and the family/caregivers may feel when hospitalized and how this can affect bedside communication with the care team.

- Describe the importance of considering the cultural factors and spiritual beliefs of patients and the family/caregivers when establishing a therapeutic relationship.

- Explain how vulnerabilities, life situations, limitations in activities of daily living, education, language, and other factors should each be considered and addressed when communicating with patients and the family/caregivers.

- Discuss methods to achieve a more favorable interchange when faced with agitated communicators, such as asking for behavior change, paraphrasing to diffuse emotion, pausing the interaction until all parties are able to participate productively, and others.

- Describe practices essential for effective communication of difficult information, including sitting down, expressing empathy, giving patients and the family/caregivers time to ask questions, maintaining a calm demeanor, and choosing a quiet, private location for the discussion.

- Describe components of effective written communication, including timing of clinical documentation, legibility, grammar, accuracy, disagreements in approaches to care, and documentation of clinical changes.

- Explain why effective communication is central to patient safety during handoffs and list evidence-based handoff tools for use within hospitalist groups and with other healthcare providers.

Skills

Pediatric hospitalists should be able to:

- Demonstrate command of a comprehensive array of expressive and receptive communication skills.

- Develop and implement effective plan for daily communication that is family-centered and models best practices in communication, such as sitting down, avoiding jargon, and addressing key patient/family concerns.

- Engage patients and the family/caregivers in shared decision-making regarding the child’s plan of care.

- Coordinate discussions with all clinical care team members (such as nurses, consultants, and others) to ensure a single clear message is given to patients, the family, and all caregivers for the child.

- Demonstrate closed-loop communication to improve patient safety and decrease communication errors.

- Participate in conflict resolution, both within the health care team and between team members and the family/caregivers when indicated.

- Identify when the use of interpreters for patients and the family/caregivers with limited English language proficiency is necessary and effectively integrate interpreters into the communication plan.

- Lead and facilitate a multidisciplinary care conference when applicable.

- Record concise, complete written documents that accurately and succinctly relay key patient information, while meeting expectations of external reviewing agencies and malpractice carriers.

- Develop clear and concise discharge instructions for patients and the family/caregivers.

- Communicate in a timely manner with a child’s primary care provider, incorporating information on the admission reason, hospital course, discharge diagnosis, discharge plan, and follow-up needs and recommendations.

Attitudes

Pediatric hospitalists should be able to:

- Acknowledge the importance of respecting the skills and contributions of all clinical and nonclinical providers involved in the care of patients.

- Realize the responsibility for promoting equitable interactions with patients and the family/caregivers, free from bias related to background, age, language, education level, race, or ethnicity.

- Exemplify professionalism in all communication.

- Seek opportunities to enhance communication skills.

Systems Organization and Improvement

In order to improve efficiency and quality within their organizations, pediatric hospitalists should:

- Collaborate with hospital administrators to improve medical record documentation systems by technical means.

- Lead, support, or assist in the development of hospital and system-wide educational programs to enhance communication skills and decrease communication-related errors.

- Work with hospital administration to establish or evaluate existing patient and family experience metrics to ultimately improve communication at the bedside.

- Lead, coordinate, or participate in activities to support effective communication methods for patients and the family/caregivers with limited English language proficiency.

Introduction

The ability to communicate effectively is a core skill for all physicians. It is of particular importance for pediatric hospitalists, who may have more limited longitudinal relationships with patients. This skill is pivotal to clinical practice, as it helps to establish rapport and a therapeutic alliance with patients and the family/caregivers. Communication is delivered both verbally and nonverbally, and can be learned and improved with practice, as with any other technical or clinical proficiency. Pediatric hospitalists must demonstrate effective communication in a variety of settings, including direct patient care, interactions with colleagues, and trainee education. The most critical setting for effective communication is at the bedside, where a pediatric hospitalist must communicate key information clearly and efficiently to patients, the family/caregivers, and to the entire healthcare team.

Knowledge

Pediatric hospitalists should be able to:

- Define the components of effective expressive and receptive communication, such as introduction of team members and their roles, avoiding medical jargon, using calm tone, appropriate word choice and body language, and allowing adequate time for patient and family input.

- Identify personal values, biases, and relationships that may influence communication.

- Discuss the benefits of including the family/caregivers and others who are important to the patient in daily decision-making and long-term plan development.

- Describe the importance of listening carefully, followed by effective use of information obtained to form conclusions and guide interventions.

- List examples of common nonlistening behaviors to avoid, such as allowing distractions, asking unrelated questions, jumping to conclusions, interrupting the speaker, and failing to notice the speaker’s nonverbal language.

- Understand the inherent vulnerability patients and the family/caregivers may feel when hospitalized and how this can affect bedside communication with the care team.

- Describe the importance of considering the cultural factors and spiritual beliefs of patients and the family/caregivers when establishing a therapeutic relationship.

- Explain how vulnerabilities, life situations, limitations in activities of daily living, education, language, and other factors should each be considered and addressed when communicating with patients and the family/caregivers.

- Discuss methods to achieve a more favorable interchange when faced with agitated communicators, such as asking for behavior change, paraphrasing to diffuse emotion, pausing the interaction until all parties are able to participate productively, and others.

- Describe practices essential for effective communication of difficult information, including sitting down, expressing empathy, giving patients and the family/caregivers time to ask questions, maintaining a calm demeanor, and choosing a quiet, private location for the discussion.

- Describe components of effective written communication, including timing of clinical documentation, legibility, grammar, accuracy, disagreements in approaches to care, and documentation of clinical changes.

- Explain why effective communication is central to patient safety during handoffs and list evidence-based handoff tools for use within hospitalist groups and with other healthcare providers.

Skills

Pediatric hospitalists should be able to:

- Demonstrate command of a comprehensive array of expressive and receptive communication skills.

- Develop and implement effective plan for daily communication that is family-centered and models best practices in communication, such as sitting down, avoiding jargon, and addressing key patient/family concerns.

- Engage patients and the family/caregivers in shared decision-making regarding the child’s plan of care.

- Coordinate discussions with all clinical care team members (such as nurses, consultants, and others) to ensure a single clear message is given to patients, the family, and all caregivers for the child.

- Demonstrate closed-loop communication to improve patient safety and decrease communication errors.

- Participate in conflict resolution, both within the health care team and between team members and the family/caregivers when indicated.

- Identify when the use of interpreters for patients and the family/caregivers with limited English language proficiency is necessary and effectively integrate interpreters into the communication plan.

- Lead and facilitate a multidisciplinary care conference when applicable.

- Record concise, complete written documents that accurately and succinctly relay key patient information, while meeting expectations of external reviewing agencies and malpractice carriers.

- Develop clear and concise discharge instructions for patients and the family/caregivers.

- Communicate in a timely manner with a child’s primary care provider, incorporating information on the admission reason, hospital course, discharge diagnosis, discharge plan, and follow-up needs and recommendations.

Attitudes

Pediatric hospitalists should be able to:

- Acknowledge the importance of respecting the skills and contributions of all clinical and nonclinical providers involved in the care of patients.

- Realize the responsibility for promoting equitable interactions with patients and the family/caregivers, free from bias related to background, age, language, education level, race, or ethnicity.

- Exemplify professionalism in all communication.

- Seek opportunities to enhance communication skills.

Systems Organization and Improvement

In order to improve efficiency and quality within their organizations, pediatric hospitalists should:

- Collaborate with hospital administrators to improve medical record documentation systems by technical means.

- Lead, support, or assist in the development of hospital and system-wide educational programs to enhance communication skills and decrease communication-related errors.

- Work with hospital administration to establish or evaluate existing patient and family experience metrics to ultimately improve communication at the bedside.

- Lead, coordinate, or participate in activities to support effective communication methods for patients and the family/caregivers with limited English language proficiency.

1. Kahn MW. Etiquette Based Medicine. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(19):1988-1989. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp0801863.

2. Levetown M and the American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Bioethics. Communicating with children and families: from everyday interactions to skill in conveying distressing information. Pediatrics. 2008;121(5). e1441-1460. https://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/121/5/e1441.long. Accessed August 28, 2019.

3. Council on Children with Disabilities and Medical Home Implementation Project Advisory Committee. AAP Policy Statement: Patient- and family-centered care coordination: a framework for integrating care for children and youth across multiple systems. Pediatrics. 2014;133(5): e1451-1460. https://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/133/5/e1451.long. Accessed August 28, 2019.

1. Kahn MW. Etiquette Based Medicine. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(19):1988-1989. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp0801863.

2. Levetown M and the American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Bioethics. Communicating with children and families: from everyday interactions to skill in conveying distressing information. Pediatrics. 2008;121(5). e1441-1460. https://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/121/5/e1441.long. Accessed August 28, 2019.

3. Council on Children with Disabilities and Medical Home Implementation Project Advisory Committee. AAP Policy Statement: Patient- and family-centered care coordination: a framework for integrating care for children and youth across multiple systems. Pediatrics. 2014;133(5): e1451-1460. https://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/133/5/e1451.long. Accessed August 28, 2019.