User login

SHM Chapter innovations: A provider exchange program

The SHM Annual Conference is more than an educational event. It also provides an opportunity to collaborate, network and create innovative ideas to improve the quality of inpatient care.

During the 2019 Annual Conference (HM19) – the last “in-person” Annual Conference before the COVID pandemic – SHM chapter leaders from the New Mexico chapter (Krystle Apodaca) and the Wiregrass chapter (Amith Skandhan), which covers the counties of Southern Alabama and the Panhandle of Florida, met during a networking event.

As we talked, we realized the unique differences and similarities our practice settings shared. We debated the role of clinician wellbeing, quality of medical education, and faculty development on individual hospital medicine group (HMG) practice styles.

Clinician well-being is the prerequisite to the Triple Aim of improving the health of populations, enhancing the patient experience, and reducing the cost of care. Engagement in local SHM chapter activities promotes the efficiency of practice, a culture of wellness, and personal resilience. Each HMG faces similar challenges but approaches to solving them vary. Professional challenges can affect the well-being of individual clinicians. During our discussion we realized that an interinstitutional exchange programs could provide a platform to exchange ideas and establish mentors.

The quality of medical education is directly linked to the quality of faculty development. Improving the quality of medical education requires a multifaceted approach by highly developed faculty. The complex factors affecting medical education and faculty development are further complicated by geographic location, patient characteristics, and professional growth opportunities.

Overcoming these obstacles requires an innovative and collaborative approach. Although faculty exchanges are common in academic medicine, they are not commonly attempted with HMGs. Hospitalists are responsible for a significant part of inpatient training for residents, medical students, and nurse practitioners/physician assistants (NPs/PAs) but their faculty training can vary based on location.

As a young specialty, hospital medicine is still evolving and incorporating NPs/PAs and physician hospitalists in varied practice models. Each HMG addresses common obstacles differently based on their culture and practice styles. As chapter leaders we determined that an exchange program would afford the opportunity for visiting faculty members to experience these differences.

We shared the idea of a chapter-level exchange with SHM’s Chapter Development Committee and obtained chapter development funds to execute the event. We also requested that an SHM national board member visit during the exchange to provide insight and feedback. We researched the characteristics of individual academic HMGs and structured a faculty exchange involving physicians and NPs/PAs. During the exchange program planning, the visiting faculty itinerary was tailored to a well-planned agenda for one week, with separate tracks for physicians and NPs/PAs, giving increased access to their individual peer practice styles. Additionally, the visiting faculty had meetings and discussions with the HMG and hospital leadership, to specifically address the visiting faculty’s institutional challenges.

The overall goal of the exchange program was to promote cross-institutional collaboration, increase engagement, improve medical education through faculty development and improve the quality of care. The focus of the exchange program was to share ideas and innovation, and learn the approaches to unique challenges at each institution. Out of this also grew collaboration and mentoring opportunities.

SHM’s New Mexico chapter is based in Albuquerque, a city in the desert Southwest with an ethnically diverse population of 545,000, The chapter leadership works at the University of New Mexico (UNM), a 553-bed medical center. UNM has a well-established internal medicine residency program, an academic hospitalist program, and an NP/PA fellowship program embedded within the hospital medicine department. At the time of the exchange, the HMG at UNM has 26 physicians and 9 NP/PA’s.

The SHM Wiregrass chapter is located in Dothan, Ala., a town of 80,000 near the Gulf of Mexico. Chapter leadership works at Southeast Health, a tertiary care facility with 420 beds, an affiliated medical school, and an internal medicine residency program. At the time of the exchange, the HMG at SEH has 28 physicians and 5 NP/PA’s.

These are two similarly sized hospital medicine programs, located in different geographic regions, and serving different populations. SHM board member Howard Epstein, MD, SFHM, vice president and chief medical officer of Presbyterian Healthcare Services in Albuquerque, participated on behalf of the Society when SEH faculty visited UNM. Kris Rehm, MD, SFHM, a pediatric hospitalist and the vice chair of outreach medicine at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, came to Dothan during the faculty visit by UNM.

Two SEH faculty members, a physician and an NP, visited the University of New Mexico Hospital for one week. They participated as observers, rounding with the teams and meeting the UNM HMG leadership. The focus of the discussions included faculty education, a curriculum for quality improvement, and ways to address practice challenges. The SEH faculty also presented a QI project from their institution, and established collaborative relationships.

During the second part of the exchange, three UNM faculty members, including one physician and two NPs, visited SEH for one week. During the visit, they observed NP/PA hospitalist team models, discussed innovations, established mentoring relationships with leadership, and discussed QI projects at SEH. Additionally, the visiting UNM faculty participated in Women In Medicine events and participated as judges for a poster competition. They also had an opportunity to explore the rural landscape and visit the beach.

The evaluation process after the exchanges involved interviews, a survey, and the establishment of shared QI projects in mutual areas of challenge. The survey provided feedback, lessons learned from the exchange, and areas to be improved. Collaborative QI projects currently underway as a result of the exchange include paging etiquette, quality of sleep for hospitalized patients, and onboarding of NPs/PAs in HMGs.

This innovation changed our thinking as medical educators by addressing faculty development and medical education via clinician well-being. The physician and NP/PA Faculty Exchange program was an essential and meaningful innovation that resulted in increased SHM member engagement, crossinstitutional collaboration, networking, and mentorship.

This event created opportunities for faculty collaboration and expanded the professional network of participating institutions. The costs of the exchange were minimal given support from SHM. We believe that once the COVID pandemic has ended, this initiative has the potential to expand facilitated exchanges nationally and internationally, enhance faculty development, and improve medical education.

Dr. Apodaca is assistant professor and nurse practitioner hospitalist at the University of New Mexico. She serves as codirector of the UNM APP Hospital Medicine Fellowship and director of the APP Hospital Medicine Team. Dr. Skandhan is a hospitalist and member of the Core Faculty for the Internal Medicine Residency Program at Southeast Health (SEH), Dothan Ala., and an assistant professor at the Alabama College of Osteopathic Medicine. He serves as the medical director/physician liaison for the Clinical Documentation Program at SEH and also as the director for physician integration for Southeast Health Statera Network, an Accountable Care Organization.

The SHM Annual Conference is more than an educational event. It also provides an opportunity to collaborate, network and create innovative ideas to improve the quality of inpatient care.

During the 2019 Annual Conference (HM19) – the last “in-person” Annual Conference before the COVID pandemic – SHM chapter leaders from the New Mexico chapter (Krystle Apodaca) and the Wiregrass chapter (Amith Skandhan), which covers the counties of Southern Alabama and the Panhandle of Florida, met during a networking event.

As we talked, we realized the unique differences and similarities our practice settings shared. We debated the role of clinician wellbeing, quality of medical education, and faculty development on individual hospital medicine group (HMG) practice styles.

Clinician well-being is the prerequisite to the Triple Aim of improving the health of populations, enhancing the patient experience, and reducing the cost of care. Engagement in local SHM chapter activities promotes the efficiency of practice, a culture of wellness, and personal resilience. Each HMG faces similar challenges but approaches to solving them vary. Professional challenges can affect the well-being of individual clinicians. During our discussion we realized that an interinstitutional exchange programs could provide a platform to exchange ideas and establish mentors.

The quality of medical education is directly linked to the quality of faculty development. Improving the quality of medical education requires a multifaceted approach by highly developed faculty. The complex factors affecting medical education and faculty development are further complicated by geographic location, patient characteristics, and professional growth opportunities.

Overcoming these obstacles requires an innovative and collaborative approach. Although faculty exchanges are common in academic medicine, they are not commonly attempted with HMGs. Hospitalists are responsible for a significant part of inpatient training for residents, medical students, and nurse practitioners/physician assistants (NPs/PAs) but their faculty training can vary based on location.

As a young specialty, hospital medicine is still evolving and incorporating NPs/PAs and physician hospitalists in varied practice models. Each HMG addresses common obstacles differently based on their culture and practice styles. As chapter leaders we determined that an exchange program would afford the opportunity for visiting faculty members to experience these differences.

We shared the idea of a chapter-level exchange with SHM’s Chapter Development Committee and obtained chapter development funds to execute the event. We also requested that an SHM national board member visit during the exchange to provide insight and feedback. We researched the characteristics of individual academic HMGs and structured a faculty exchange involving physicians and NPs/PAs. During the exchange program planning, the visiting faculty itinerary was tailored to a well-planned agenda for one week, with separate tracks for physicians and NPs/PAs, giving increased access to their individual peer practice styles. Additionally, the visiting faculty had meetings and discussions with the HMG and hospital leadership, to specifically address the visiting faculty’s institutional challenges.

The overall goal of the exchange program was to promote cross-institutional collaboration, increase engagement, improve medical education through faculty development and improve the quality of care. The focus of the exchange program was to share ideas and innovation, and learn the approaches to unique challenges at each institution. Out of this also grew collaboration and mentoring opportunities.

SHM’s New Mexico chapter is based in Albuquerque, a city in the desert Southwest with an ethnically diverse population of 545,000, The chapter leadership works at the University of New Mexico (UNM), a 553-bed medical center. UNM has a well-established internal medicine residency program, an academic hospitalist program, and an NP/PA fellowship program embedded within the hospital medicine department. At the time of the exchange, the HMG at UNM has 26 physicians and 9 NP/PA’s.

The SHM Wiregrass chapter is located in Dothan, Ala., a town of 80,000 near the Gulf of Mexico. Chapter leadership works at Southeast Health, a tertiary care facility with 420 beds, an affiliated medical school, and an internal medicine residency program. At the time of the exchange, the HMG at SEH has 28 physicians and 5 NP/PA’s.

These are two similarly sized hospital medicine programs, located in different geographic regions, and serving different populations. SHM board member Howard Epstein, MD, SFHM, vice president and chief medical officer of Presbyterian Healthcare Services in Albuquerque, participated on behalf of the Society when SEH faculty visited UNM. Kris Rehm, MD, SFHM, a pediatric hospitalist and the vice chair of outreach medicine at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, came to Dothan during the faculty visit by UNM.

Two SEH faculty members, a physician and an NP, visited the University of New Mexico Hospital for one week. They participated as observers, rounding with the teams and meeting the UNM HMG leadership. The focus of the discussions included faculty education, a curriculum for quality improvement, and ways to address practice challenges. The SEH faculty also presented a QI project from their institution, and established collaborative relationships.

During the second part of the exchange, three UNM faculty members, including one physician and two NPs, visited SEH for one week. During the visit, they observed NP/PA hospitalist team models, discussed innovations, established mentoring relationships with leadership, and discussed QI projects at SEH. Additionally, the visiting UNM faculty participated in Women In Medicine events and participated as judges for a poster competition. They also had an opportunity to explore the rural landscape and visit the beach.

The evaluation process after the exchanges involved interviews, a survey, and the establishment of shared QI projects in mutual areas of challenge. The survey provided feedback, lessons learned from the exchange, and areas to be improved. Collaborative QI projects currently underway as a result of the exchange include paging etiquette, quality of sleep for hospitalized patients, and onboarding of NPs/PAs in HMGs.

This innovation changed our thinking as medical educators by addressing faculty development and medical education via clinician well-being. The physician and NP/PA Faculty Exchange program was an essential and meaningful innovation that resulted in increased SHM member engagement, crossinstitutional collaboration, networking, and mentorship.

This event created opportunities for faculty collaboration and expanded the professional network of participating institutions. The costs of the exchange were minimal given support from SHM. We believe that once the COVID pandemic has ended, this initiative has the potential to expand facilitated exchanges nationally and internationally, enhance faculty development, and improve medical education.

Dr. Apodaca is assistant professor and nurse practitioner hospitalist at the University of New Mexico. She serves as codirector of the UNM APP Hospital Medicine Fellowship and director of the APP Hospital Medicine Team. Dr. Skandhan is a hospitalist and member of the Core Faculty for the Internal Medicine Residency Program at Southeast Health (SEH), Dothan Ala., and an assistant professor at the Alabama College of Osteopathic Medicine. He serves as the medical director/physician liaison for the Clinical Documentation Program at SEH and also as the director for physician integration for Southeast Health Statera Network, an Accountable Care Organization.

The SHM Annual Conference is more than an educational event. It also provides an opportunity to collaborate, network and create innovative ideas to improve the quality of inpatient care.

During the 2019 Annual Conference (HM19) – the last “in-person” Annual Conference before the COVID pandemic – SHM chapter leaders from the New Mexico chapter (Krystle Apodaca) and the Wiregrass chapter (Amith Skandhan), which covers the counties of Southern Alabama and the Panhandle of Florida, met during a networking event.

As we talked, we realized the unique differences and similarities our practice settings shared. We debated the role of clinician wellbeing, quality of medical education, and faculty development on individual hospital medicine group (HMG) practice styles.

Clinician well-being is the prerequisite to the Triple Aim of improving the health of populations, enhancing the patient experience, and reducing the cost of care. Engagement in local SHM chapter activities promotes the efficiency of practice, a culture of wellness, and personal resilience. Each HMG faces similar challenges but approaches to solving them vary. Professional challenges can affect the well-being of individual clinicians. During our discussion we realized that an interinstitutional exchange programs could provide a platform to exchange ideas and establish mentors.

The quality of medical education is directly linked to the quality of faculty development. Improving the quality of medical education requires a multifaceted approach by highly developed faculty. The complex factors affecting medical education and faculty development are further complicated by geographic location, patient characteristics, and professional growth opportunities.

Overcoming these obstacles requires an innovative and collaborative approach. Although faculty exchanges are common in academic medicine, they are not commonly attempted with HMGs. Hospitalists are responsible for a significant part of inpatient training for residents, medical students, and nurse practitioners/physician assistants (NPs/PAs) but their faculty training can vary based on location.

As a young specialty, hospital medicine is still evolving and incorporating NPs/PAs and physician hospitalists in varied practice models. Each HMG addresses common obstacles differently based on their culture and practice styles. As chapter leaders we determined that an exchange program would afford the opportunity for visiting faculty members to experience these differences.

We shared the idea of a chapter-level exchange with SHM’s Chapter Development Committee and obtained chapter development funds to execute the event. We also requested that an SHM national board member visit during the exchange to provide insight and feedback. We researched the characteristics of individual academic HMGs and structured a faculty exchange involving physicians and NPs/PAs. During the exchange program planning, the visiting faculty itinerary was tailored to a well-planned agenda for one week, with separate tracks for physicians and NPs/PAs, giving increased access to their individual peer practice styles. Additionally, the visiting faculty had meetings and discussions with the HMG and hospital leadership, to specifically address the visiting faculty’s institutional challenges.

The overall goal of the exchange program was to promote cross-institutional collaboration, increase engagement, improve medical education through faculty development and improve the quality of care. The focus of the exchange program was to share ideas and innovation, and learn the approaches to unique challenges at each institution. Out of this also grew collaboration and mentoring opportunities.

SHM’s New Mexico chapter is based in Albuquerque, a city in the desert Southwest with an ethnically diverse population of 545,000, The chapter leadership works at the University of New Mexico (UNM), a 553-bed medical center. UNM has a well-established internal medicine residency program, an academic hospitalist program, and an NP/PA fellowship program embedded within the hospital medicine department. At the time of the exchange, the HMG at UNM has 26 physicians and 9 NP/PA’s.

The SHM Wiregrass chapter is located in Dothan, Ala., a town of 80,000 near the Gulf of Mexico. Chapter leadership works at Southeast Health, a tertiary care facility with 420 beds, an affiliated medical school, and an internal medicine residency program. At the time of the exchange, the HMG at SEH has 28 physicians and 5 NP/PA’s.

These are two similarly sized hospital medicine programs, located in different geographic regions, and serving different populations. SHM board member Howard Epstein, MD, SFHM, vice president and chief medical officer of Presbyterian Healthcare Services in Albuquerque, participated on behalf of the Society when SEH faculty visited UNM. Kris Rehm, MD, SFHM, a pediatric hospitalist and the vice chair of outreach medicine at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, came to Dothan during the faculty visit by UNM.

Two SEH faculty members, a physician and an NP, visited the University of New Mexico Hospital for one week. They participated as observers, rounding with the teams and meeting the UNM HMG leadership. The focus of the discussions included faculty education, a curriculum for quality improvement, and ways to address practice challenges. The SEH faculty also presented a QI project from their institution, and established collaborative relationships.

During the second part of the exchange, three UNM faculty members, including one physician and two NPs, visited SEH for one week. During the visit, they observed NP/PA hospitalist team models, discussed innovations, established mentoring relationships with leadership, and discussed QI projects at SEH. Additionally, the visiting UNM faculty participated in Women In Medicine events and participated as judges for a poster competition. They also had an opportunity to explore the rural landscape and visit the beach.

The evaluation process after the exchanges involved interviews, a survey, and the establishment of shared QI projects in mutual areas of challenge. The survey provided feedback, lessons learned from the exchange, and areas to be improved. Collaborative QI projects currently underway as a result of the exchange include paging etiquette, quality of sleep for hospitalized patients, and onboarding of NPs/PAs in HMGs.

This innovation changed our thinking as medical educators by addressing faculty development and medical education via clinician well-being. The physician and NP/PA Faculty Exchange program was an essential and meaningful innovation that resulted in increased SHM member engagement, crossinstitutional collaboration, networking, and mentorship.

This event created opportunities for faculty collaboration and expanded the professional network of participating institutions. The costs of the exchange were minimal given support from SHM. We believe that once the COVID pandemic has ended, this initiative has the potential to expand facilitated exchanges nationally and internationally, enhance faculty development, and improve medical education.

Dr. Apodaca is assistant professor and nurse practitioner hospitalist at the University of New Mexico. She serves as codirector of the UNM APP Hospital Medicine Fellowship and director of the APP Hospital Medicine Team. Dr. Skandhan is a hospitalist and member of the Core Faculty for the Internal Medicine Residency Program at Southeast Health (SEH), Dothan Ala., and an assistant professor at the Alabama College of Osteopathic Medicine. He serves as the medical director/physician liaison for the Clinical Documentation Program at SEH and also as the director for physician integration for Southeast Health Statera Network, an Accountable Care Organization.

What hospitalists need to know about COVID-19

This article last updated 4/8/20. (Disclaimer: The information in this article may not be updated regularly. For more COVID-19 coverage, bookmark our COVID-19 updates page. The editors of The Hospitalist encourage clinicians to also review information on the CDC website and on the AHA website.)

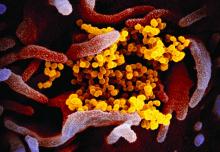

An infectious disease outbreak that began in December 2019 in Wuhan (Hubei Province), China, was found to be caused by the seventh strain of coronavirus, initially called the novel (new) coronavirus. The virus was later labeled as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The disease caused by SARS-CoV-2 is named COVID-19. Until 2019, only six strains of human coronaviruses had previously been identified.

As of April 8, 2020, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, COVID-19 has been detected in at least 209 countries and has spread to every contintent except Antarctica. More than 1,469,245 people have become infected globally, and at least 86,278 have died. Based on the cases detected and tested in the United States through the U.S. public health surveillance systems, we have had 406,693 confirmed cases and 13,089 deaths.

On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization formally declared the COVID-19 outbreak to be a pandemic.

As the number of cases increases in the United States, we hope to provide answers about some common questions regarding COVID-19. The information summarized in this article is obtained and modified from the CDC.

What are the clinical features of COVID-19?

Ranges from asymptomatic infection, a mild disease with nonspecific signs and symptoms of acute respiratory illness, to severe pneumonia with respiratory failure and septic shock.

Who is at risk for COVID-19?

Persons who have had prolonged, unprotected close contact with a patient with symptomatic, confirmed COVID-19, and those with recent travel to China, especially Hubei Province.

Who is at risk for severe disease from COVID-19?

Older adults and persons who have underlying chronic medical conditions, such as immunocompromising conditions.

How is COVID-19 spread?

Person-to-person, mainly through respiratory droplets. SARS-CoV-2 has been isolated from upper respiratory tract specimens and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid.

When is someone infectious?

Incubation period may range from 2 to 14 days. Detection of viral RNA does not necessarily mean that infectious virus is present, as it may be detectable in the upper or lower respiratory tract for weeks after illness onset.

Can someone who has been quarantined for COVID-19 spread the illness to others?

For COVID-19, the period of quarantine is 14 days from the last date of exposure, because 14 days is the longest incubation period seen for similar coronaviruses. Someone who has been released from COVID-19 quarantine is not considered a risk for spreading the virus to others because they have not developed illness during the incubation period.

Can a person test negative and later test positive for COVID-19?

Yes. In the early stages of infection, it is possible the virus will not be detected.

Do patients with confirmed or suspected COVID-19 need to be admitted to the hospital?

Not all patients with COVID-19 require hospital admission. Patients whose clinical presentation warrants inpatient clinical management for supportive medical care should be admitted to the hospital under appropriate isolation precautions. The decision to monitor these patients in the inpatient or outpatient setting should be made on a case-by-case basis.

What should you do if you suspect a patient for COVID-19?

Immediately notify both infection control personnel at your health care facility and your local or state health department. State health departments that have identified a person under investigation (PUI) should immediately contact CDC’s Emergency Operations Center (EOC) at 770-488-7100 and complete a COVID-19 PUI case investigation form.

CDC’s EOC will assist local/state health departments to collect, store, and ship specimens appropriately to CDC, including during after-hours or on weekends/holidays.

What type of isolation is needed for COVID-19?

Airborne Infection Isolation Room (AIIR) using Standard, Contact, and Airborne Precautions with eye protection.

How should health care personnel protect themselves when evaluating a patient who may have COVID-19?

Standard Precautions, Contact Precautions, Airborne Precautions, and use eye protection (e.g., goggles or a face shield).

What face mask do health care workers wear for respiratory protection?

A fit-tested NIOSH-certified disposable N95 filtering facepiece respirator should be worn before entry into the patient room or care area. Disposable respirators should be removed and discarded after exiting the patient’s room or care area and closing the door. Perform hand hygiene after discarding the respirator.

If reusable respirators (e.g., powered air purifying respirator/PAPR) are used, they must be cleaned and disinfected according to manufacturer’s reprocessing instructions prior to re-use.

What should you tell the patient if COVID-19 is suspected or confirmed?

Patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 should be asked to wear a surgical mask as soon as they are identified, to prevent spread to others.

Should any diagnostic or therapeutic interventions be withheld because of concerns about the transmission of COVID-19?

No.

How do you test a patient for SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19?

At this time, diagnostic testing for COVID-19 can be conducted only at CDC.

The CDC recommends collecting and testing multiple clinical specimens from different sites, including two specimen types – lower respiratory and upper respiratory (nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal aspirates or washes, nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swabs, bronchioalveolar lavage, tracheal aspirates, sputum, and serum) using a real-time reverse transcription PCR (rRT-PCR) assay for SARS-CoV-2. Specimens should be collected as soon as possible once a PUI is identified regardless of the time of symptom onset. Turnaround time for the PCR assay testing is about 24-48 hours.

Testing for other respiratory pathogens should not delay specimen shipping to CDC. If a PUI tests positive for another respiratory pathogen, after clinical evaluation and consultation with public health authorities, they may no longer be considered a PUI.

Will existing respiratory virus panels detect SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19?

No.

How is COVID-19 treated?

Symptomatic management. Corticosteroids are not routinely recommended for viral pneumonia or acute respiratory distress syndrome and should be avoided unless they are indicated for another reason (e.g., COPD exacerbation, refractory septic shock following Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines). There are currently no antiviral drugs licensed by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to treat COVID-19.

What is considered ‘close contact’ for health care exposures?

Being within approximately 6 feet (2 meters), of a person with COVID-19 for a prolonged period of time (such as caring for or visiting the patient, or sitting within 6 feet of the patient in a health care waiting area or room); or having unprotected direct contact with infectious secretions or excretions of the patient (e.g., being coughed on, touching used tissues with a bare hand). However, until more is known about transmission risks, it would be reasonable to consider anything longer than a brief (e.g., less than 1-2 minutes) exposure as prolonged.

What happens if the health care personnel (HCP) are exposed to confirmed COVID-19 patients? What’s the protocol for HCP exposed to persons under investigation (PUI) if test results are delayed beyond 48-72 hours?

Management is similar in both these scenarios. CDC categorized exposures as high, medium, low, and no identifiable risk. High- and medium-risk exposures are managed similarly with active monitoring for COVID-19 until 14 days after last potential exposure and exclude from work for 14 days after last exposure. Active monitoring means that the state or local public health authority assumes responsibility for establishing regular communication with potentially exposed people to assess for the presence of fever or respiratory symptoms (e.g., cough, shortness of breath, sore throat). For HCP with high- or medium-risk exposures, CDC recommends this communication occurs at least once each day. For full details, please see www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/guidance-risk-assesment-hcp.html.

Should postexposure prophylaxis be used for people who may have been exposed to COVID-19?

None available.

COVID-19 test results are negative in a symptomatic patient you suspected of COVID-19? What does it mean?

A negative test result for a sample collected while a person has symptoms likely means that the COVID-19 virus is not causing their current illness.

What if your hospital does not have an Airborne Infection Isolation Room (AIIR) for COVID-19 patients?

Transfer the patient to a facility that has an available AIIR. If a transfer is impractical or not medically appropriate, the patient should be cared for in a single-person room and the door should be kept closed. The room should ideally not have an exhaust that is recirculated within the building without high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filtration. Health care personnel should still use gloves, gown, respiratory and eye protection and follow all other recommended infection prevention and control practices when caring for these patients.

What if your hospital does not have enough Airborne Infection Isolation Rooms (AIIR) for COVID-19 patients?

Prioritize patients for AIIR who are symptomatic with severe illness (e.g., those requiring ventilator support).

When can patients with confirmed COVID-19 be discharged from the hospital?

Patients can be discharged from the health care facility whenever clinically indicated. Isolation should be maintained at home if the patient returns home before the time period recommended for discontinuation of hospital transmission-based precautions.

Considerations to discontinue transmission-based precautions include all of the following:

- Resolution of fever, without the use of antipyretic medication.

- Improvement in illness signs and symptoms.

- Negative rRT-PCR results from at least two consecutive sets of paired nasopharyngeal and throat swabs specimens collected at least 24 hours apart (total of four negative specimens – two nasopharyngeal and two throat) from a patient with COVID-19 are needed before discontinuing transmission-based precautions.

Should people be concerned about pets or other animals and COVID-19?

To date, CDC has not received any reports of pets or other animals becoming sick with COVID-19.

Should patients avoid contact with pets or other animals if they are sick with COVID-19?

Patients should restrict contact with pets and other animals while they are sick with COVID-19, just like they would around other people.

Does CDC recommend the use of face masks in the community to prevent COVID-19?

CDC does not recommend that people who are well wear a face mask to protect themselves from respiratory illnesses, including COVID-19. A face mask should be used by people who have COVID-19 and are showing symptoms to protect others from the risk of getting infected.

Should medical waste or general waste from health care facilities treating PUIs and patients with confirmed COVID-19 be handled any differently or need any additional disinfection?

No. CDC’s guidance states that management of laundry, food service utensils, and medical waste should be performed in accordance with routine procedures.

Can people who recover from COVID-19 be infected again?

Unknown. The immune response to COVID-19 is not yet understood.

What is the mortality rate of COVID-19, and how does it compare to the mortality rate of influenza (flu)?

The average 10-year mortality rate for flu, using CDC data, is found to be around 0.1%. Even though this percentage appears to be small, influenza is estimated to be responsible for 30,000 to 40,000 deaths annually in the U.S.

According to statistics released by the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention on Feb. 17, the mortality rate of COVID-19 is estimated to be around 2.3%. This calculation was based on cases reported through Feb. 11, and calcuated by dividing the number of coronavirus-related deaths at the time (1,023) by the number of confirmed cases (44,672) of COVID-19 infection. However, this report has its limitations, since Chinese officials have a vague way of defining who has COVID-19 infection.

The World Health Organization (WHO) currently estimates the mortality rate for COVID-19 to be between 2% and 4%.

Dr. Sitammagari is a co-medical director for quality and assistant professor of internal medicine at Atrium Health, Charlotte, N.C. He is also a physician advisor. He currently serves as treasurer for the NC-Triangle Chapter of the Society of Hospital Medicine and as an editorial board member of The Hospitalist.

Dr. Skandhan is a hospitalist and member of the Core Faculty for the Internal Medicine Residency Program at Southeast Health (SEH), Dothan Ala., and an assistant professor at the Alabama College of Osteopathic Medicine. He serves as the medical director/physician liaison for the Clinical Documentation Program at SEH and also as the director for physician integration for Southeast Health Statera Network, an Accountable Care Organization. Dr. Skandhan was a cofounder of the Wiregrass chapter of SHM and currently serves on the Advisory board. He is also a member of the editorial board of The Hospitalist.

Dr. Dahlin is a second-year internal medicine resident at Southeast Health, Dothan, Ala. She serves as her class representative and is the cochair/resident liaison for the research committee at SEH. Dr. Dahlin also serves as a resident liaison for the Wiregrass chapter of SHM.

This article last updated 4/8/20. (Disclaimer: The information in this article may not be updated regularly. For more COVID-19 coverage, bookmark our COVID-19 updates page. The editors of The Hospitalist encourage clinicians to also review information on the CDC website and on the AHA website.)

An infectious disease outbreak that began in December 2019 in Wuhan (Hubei Province), China, was found to be caused by the seventh strain of coronavirus, initially called the novel (new) coronavirus. The virus was later labeled as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The disease caused by SARS-CoV-2 is named COVID-19. Until 2019, only six strains of human coronaviruses had previously been identified.

As of April 8, 2020, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, COVID-19 has been detected in at least 209 countries and has spread to every contintent except Antarctica. More than 1,469,245 people have become infected globally, and at least 86,278 have died. Based on the cases detected and tested in the United States through the U.S. public health surveillance systems, we have had 406,693 confirmed cases and 13,089 deaths.

On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization formally declared the COVID-19 outbreak to be a pandemic.

As the number of cases increases in the United States, we hope to provide answers about some common questions regarding COVID-19. The information summarized in this article is obtained and modified from the CDC.

What are the clinical features of COVID-19?

Ranges from asymptomatic infection, a mild disease with nonspecific signs and symptoms of acute respiratory illness, to severe pneumonia with respiratory failure and septic shock.

Who is at risk for COVID-19?

Persons who have had prolonged, unprotected close contact with a patient with symptomatic, confirmed COVID-19, and those with recent travel to China, especially Hubei Province.

Who is at risk for severe disease from COVID-19?

Older adults and persons who have underlying chronic medical conditions, such as immunocompromising conditions.

How is COVID-19 spread?

Person-to-person, mainly through respiratory droplets. SARS-CoV-2 has been isolated from upper respiratory tract specimens and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid.

When is someone infectious?

Incubation period may range from 2 to 14 days. Detection of viral RNA does not necessarily mean that infectious virus is present, as it may be detectable in the upper or lower respiratory tract for weeks after illness onset.

Can someone who has been quarantined for COVID-19 spread the illness to others?

For COVID-19, the period of quarantine is 14 days from the last date of exposure, because 14 days is the longest incubation period seen for similar coronaviruses. Someone who has been released from COVID-19 quarantine is not considered a risk for spreading the virus to others because they have not developed illness during the incubation period.

Can a person test negative and later test positive for COVID-19?

Yes. In the early stages of infection, it is possible the virus will not be detected.

Do patients with confirmed or suspected COVID-19 need to be admitted to the hospital?

Not all patients with COVID-19 require hospital admission. Patients whose clinical presentation warrants inpatient clinical management for supportive medical care should be admitted to the hospital under appropriate isolation precautions. The decision to monitor these patients in the inpatient or outpatient setting should be made on a case-by-case basis.

What should you do if you suspect a patient for COVID-19?

Immediately notify both infection control personnel at your health care facility and your local or state health department. State health departments that have identified a person under investigation (PUI) should immediately contact CDC’s Emergency Operations Center (EOC) at 770-488-7100 and complete a COVID-19 PUI case investigation form.

CDC’s EOC will assist local/state health departments to collect, store, and ship specimens appropriately to CDC, including during after-hours or on weekends/holidays.

What type of isolation is needed for COVID-19?

Airborne Infection Isolation Room (AIIR) using Standard, Contact, and Airborne Precautions with eye protection.

How should health care personnel protect themselves when evaluating a patient who may have COVID-19?

Standard Precautions, Contact Precautions, Airborne Precautions, and use eye protection (e.g., goggles or a face shield).

What face mask do health care workers wear for respiratory protection?

A fit-tested NIOSH-certified disposable N95 filtering facepiece respirator should be worn before entry into the patient room or care area. Disposable respirators should be removed and discarded after exiting the patient’s room or care area and closing the door. Perform hand hygiene after discarding the respirator.

If reusable respirators (e.g., powered air purifying respirator/PAPR) are used, they must be cleaned and disinfected according to manufacturer’s reprocessing instructions prior to re-use.

What should you tell the patient if COVID-19 is suspected or confirmed?

Patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 should be asked to wear a surgical mask as soon as they are identified, to prevent spread to others.

Should any diagnostic or therapeutic interventions be withheld because of concerns about the transmission of COVID-19?

No.

How do you test a patient for SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19?

At this time, diagnostic testing for COVID-19 can be conducted only at CDC.

The CDC recommends collecting and testing multiple clinical specimens from different sites, including two specimen types – lower respiratory and upper respiratory (nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal aspirates or washes, nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swabs, bronchioalveolar lavage, tracheal aspirates, sputum, and serum) using a real-time reverse transcription PCR (rRT-PCR) assay for SARS-CoV-2. Specimens should be collected as soon as possible once a PUI is identified regardless of the time of symptom onset. Turnaround time for the PCR assay testing is about 24-48 hours.

Testing for other respiratory pathogens should not delay specimen shipping to CDC. If a PUI tests positive for another respiratory pathogen, after clinical evaluation and consultation with public health authorities, they may no longer be considered a PUI.

Will existing respiratory virus panels detect SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19?

No.

How is COVID-19 treated?

Symptomatic management. Corticosteroids are not routinely recommended for viral pneumonia or acute respiratory distress syndrome and should be avoided unless they are indicated for another reason (e.g., COPD exacerbation, refractory septic shock following Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines). There are currently no antiviral drugs licensed by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to treat COVID-19.

What is considered ‘close contact’ for health care exposures?

Being within approximately 6 feet (2 meters), of a person with COVID-19 for a prolonged period of time (such as caring for or visiting the patient, or sitting within 6 feet of the patient in a health care waiting area or room); or having unprotected direct contact with infectious secretions or excretions of the patient (e.g., being coughed on, touching used tissues with a bare hand). However, until more is known about transmission risks, it would be reasonable to consider anything longer than a brief (e.g., less than 1-2 minutes) exposure as prolonged.

What happens if the health care personnel (HCP) are exposed to confirmed COVID-19 patients? What’s the protocol for HCP exposed to persons under investigation (PUI) if test results are delayed beyond 48-72 hours?

Management is similar in both these scenarios. CDC categorized exposures as high, medium, low, and no identifiable risk. High- and medium-risk exposures are managed similarly with active monitoring for COVID-19 until 14 days after last potential exposure and exclude from work for 14 days after last exposure. Active monitoring means that the state or local public health authority assumes responsibility for establishing regular communication with potentially exposed people to assess for the presence of fever or respiratory symptoms (e.g., cough, shortness of breath, sore throat). For HCP with high- or medium-risk exposures, CDC recommends this communication occurs at least once each day. For full details, please see www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/guidance-risk-assesment-hcp.html.

Should postexposure prophylaxis be used for people who may have been exposed to COVID-19?

None available.

COVID-19 test results are negative in a symptomatic patient you suspected of COVID-19? What does it mean?

A negative test result for a sample collected while a person has symptoms likely means that the COVID-19 virus is not causing their current illness.

What if your hospital does not have an Airborne Infection Isolation Room (AIIR) for COVID-19 patients?

Transfer the patient to a facility that has an available AIIR. If a transfer is impractical or not medically appropriate, the patient should be cared for in a single-person room and the door should be kept closed. The room should ideally not have an exhaust that is recirculated within the building without high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filtration. Health care personnel should still use gloves, gown, respiratory and eye protection and follow all other recommended infection prevention and control practices when caring for these patients.

What if your hospital does not have enough Airborne Infection Isolation Rooms (AIIR) for COVID-19 patients?

Prioritize patients for AIIR who are symptomatic with severe illness (e.g., those requiring ventilator support).

When can patients with confirmed COVID-19 be discharged from the hospital?

Patients can be discharged from the health care facility whenever clinically indicated. Isolation should be maintained at home if the patient returns home before the time period recommended for discontinuation of hospital transmission-based precautions.

Considerations to discontinue transmission-based precautions include all of the following:

- Resolution of fever, without the use of antipyretic medication.

- Improvement in illness signs and symptoms.

- Negative rRT-PCR results from at least two consecutive sets of paired nasopharyngeal and throat swabs specimens collected at least 24 hours apart (total of four negative specimens – two nasopharyngeal and two throat) from a patient with COVID-19 are needed before discontinuing transmission-based precautions.

Should people be concerned about pets or other animals and COVID-19?

To date, CDC has not received any reports of pets or other animals becoming sick with COVID-19.

Should patients avoid contact with pets or other animals if they are sick with COVID-19?

Patients should restrict contact with pets and other animals while they are sick with COVID-19, just like they would around other people.

Does CDC recommend the use of face masks in the community to prevent COVID-19?

CDC does not recommend that people who are well wear a face mask to protect themselves from respiratory illnesses, including COVID-19. A face mask should be used by people who have COVID-19 and are showing symptoms to protect others from the risk of getting infected.

Should medical waste or general waste from health care facilities treating PUIs and patients with confirmed COVID-19 be handled any differently or need any additional disinfection?

No. CDC’s guidance states that management of laundry, food service utensils, and medical waste should be performed in accordance with routine procedures.

Can people who recover from COVID-19 be infected again?

Unknown. The immune response to COVID-19 is not yet understood.

What is the mortality rate of COVID-19, and how does it compare to the mortality rate of influenza (flu)?

The average 10-year mortality rate for flu, using CDC data, is found to be around 0.1%. Even though this percentage appears to be small, influenza is estimated to be responsible for 30,000 to 40,000 deaths annually in the U.S.

According to statistics released by the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention on Feb. 17, the mortality rate of COVID-19 is estimated to be around 2.3%. This calculation was based on cases reported through Feb. 11, and calcuated by dividing the number of coronavirus-related deaths at the time (1,023) by the number of confirmed cases (44,672) of COVID-19 infection. However, this report has its limitations, since Chinese officials have a vague way of defining who has COVID-19 infection.

The World Health Organization (WHO) currently estimates the mortality rate for COVID-19 to be between 2% and 4%.

Dr. Sitammagari is a co-medical director for quality and assistant professor of internal medicine at Atrium Health, Charlotte, N.C. He is also a physician advisor. He currently serves as treasurer for the NC-Triangle Chapter of the Society of Hospital Medicine and as an editorial board member of The Hospitalist.

Dr. Skandhan is a hospitalist and member of the Core Faculty for the Internal Medicine Residency Program at Southeast Health (SEH), Dothan Ala., and an assistant professor at the Alabama College of Osteopathic Medicine. He serves as the medical director/physician liaison for the Clinical Documentation Program at SEH and also as the director for physician integration for Southeast Health Statera Network, an Accountable Care Organization. Dr. Skandhan was a cofounder of the Wiregrass chapter of SHM and currently serves on the Advisory board. He is also a member of the editorial board of The Hospitalist.

Dr. Dahlin is a second-year internal medicine resident at Southeast Health, Dothan, Ala. She serves as her class representative and is the cochair/resident liaison for the research committee at SEH. Dr. Dahlin also serves as a resident liaison for the Wiregrass chapter of SHM.

This article last updated 4/8/20. (Disclaimer: The information in this article may not be updated regularly. For more COVID-19 coverage, bookmark our COVID-19 updates page. The editors of The Hospitalist encourage clinicians to also review information on the CDC website and on the AHA website.)

An infectious disease outbreak that began in December 2019 in Wuhan (Hubei Province), China, was found to be caused by the seventh strain of coronavirus, initially called the novel (new) coronavirus. The virus was later labeled as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The disease caused by SARS-CoV-2 is named COVID-19. Until 2019, only six strains of human coronaviruses had previously been identified.

As of April 8, 2020, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, COVID-19 has been detected in at least 209 countries and has spread to every contintent except Antarctica. More than 1,469,245 people have become infected globally, and at least 86,278 have died. Based on the cases detected and tested in the United States through the U.S. public health surveillance systems, we have had 406,693 confirmed cases and 13,089 deaths.

On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization formally declared the COVID-19 outbreak to be a pandemic.

As the number of cases increases in the United States, we hope to provide answers about some common questions regarding COVID-19. The information summarized in this article is obtained and modified from the CDC.

What are the clinical features of COVID-19?

Ranges from asymptomatic infection, a mild disease with nonspecific signs and symptoms of acute respiratory illness, to severe pneumonia with respiratory failure and septic shock.

Who is at risk for COVID-19?

Persons who have had prolonged, unprotected close contact with a patient with symptomatic, confirmed COVID-19, and those with recent travel to China, especially Hubei Province.

Who is at risk for severe disease from COVID-19?

Older adults and persons who have underlying chronic medical conditions, such as immunocompromising conditions.

How is COVID-19 spread?

Person-to-person, mainly through respiratory droplets. SARS-CoV-2 has been isolated from upper respiratory tract specimens and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid.

When is someone infectious?

Incubation period may range from 2 to 14 days. Detection of viral RNA does not necessarily mean that infectious virus is present, as it may be detectable in the upper or lower respiratory tract for weeks after illness onset.

Can someone who has been quarantined for COVID-19 spread the illness to others?

For COVID-19, the period of quarantine is 14 days from the last date of exposure, because 14 days is the longest incubation period seen for similar coronaviruses. Someone who has been released from COVID-19 quarantine is not considered a risk for spreading the virus to others because they have not developed illness during the incubation period.

Can a person test negative and later test positive for COVID-19?

Yes. In the early stages of infection, it is possible the virus will not be detected.

Do patients with confirmed or suspected COVID-19 need to be admitted to the hospital?

Not all patients with COVID-19 require hospital admission. Patients whose clinical presentation warrants inpatient clinical management for supportive medical care should be admitted to the hospital under appropriate isolation precautions. The decision to monitor these patients in the inpatient or outpatient setting should be made on a case-by-case basis.

What should you do if you suspect a patient for COVID-19?

Immediately notify both infection control personnel at your health care facility and your local or state health department. State health departments that have identified a person under investigation (PUI) should immediately contact CDC’s Emergency Operations Center (EOC) at 770-488-7100 and complete a COVID-19 PUI case investigation form.

CDC’s EOC will assist local/state health departments to collect, store, and ship specimens appropriately to CDC, including during after-hours or on weekends/holidays.

What type of isolation is needed for COVID-19?

Airborne Infection Isolation Room (AIIR) using Standard, Contact, and Airborne Precautions with eye protection.

How should health care personnel protect themselves when evaluating a patient who may have COVID-19?

Standard Precautions, Contact Precautions, Airborne Precautions, and use eye protection (e.g., goggles or a face shield).

What face mask do health care workers wear for respiratory protection?

A fit-tested NIOSH-certified disposable N95 filtering facepiece respirator should be worn before entry into the patient room or care area. Disposable respirators should be removed and discarded after exiting the patient’s room or care area and closing the door. Perform hand hygiene after discarding the respirator.

If reusable respirators (e.g., powered air purifying respirator/PAPR) are used, they must be cleaned and disinfected according to manufacturer’s reprocessing instructions prior to re-use.

What should you tell the patient if COVID-19 is suspected or confirmed?

Patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 should be asked to wear a surgical mask as soon as they are identified, to prevent spread to others.

Should any diagnostic or therapeutic interventions be withheld because of concerns about the transmission of COVID-19?

No.

How do you test a patient for SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19?

At this time, diagnostic testing for COVID-19 can be conducted only at CDC.

The CDC recommends collecting and testing multiple clinical specimens from different sites, including two specimen types – lower respiratory and upper respiratory (nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal aspirates or washes, nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swabs, bronchioalveolar lavage, tracheal aspirates, sputum, and serum) using a real-time reverse transcription PCR (rRT-PCR) assay for SARS-CoV-2. Specimens should be collected as soon as possible once a PUI is identified regardless of the time of symptom onset. Turnaround time for the PCR assay testing is about 24-48 hours.

Testing for other respiratory pathogens should not delay specimen shipping to CDC. If a PUI tests positive for another respiratory pathogen, after clinical evaluation and consultation with public health authorities, they may no longer be considered a PUI.

Will existing respiratory virus panels detect SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19?

No.

How is COVID-19 treated?

Symptomatic management. Corticosteroids are not routinely recommended for viral pneumonia or acute respiratory distress syndrome and should be avoided unless they are indicated for another reason (e.g., COPD exacerbation, refractory septic shock following Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines). There are currently no antiviral drugs licensed by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to treat COVID-19.

What is considered ‘close contact’ for health care exposures?

Being within approximately 6 feet (2 meters), of a person with COVID-19 for a prolonged period of time (such as caring for or visiting the patient, or sitting within 6 feet of the patient in a health care waiting area or room); or having unprotected direct contact with infectious secretions or excretions of the patient (e.g., being coughed on, touching used tissues with a bare hand). However, until more is known about transmission risks, it would be reasonable to consider anything longer than a brief (e.g., less than 1-2 minutes) exposure as prolonged.

What happens if the health care personnel (HCP) are exposed to confirmed COVID-19 patients? What’s the protocol for HCP exposed to persons under investigation (PUI) if test results are delayed beyond 48-72 hours?

Management is similar in both these scenarios. CDC categorized exposures as high, medium, low, and no identifiable risk. High- and medium-risk exposures are managed similarly with active monitoring for COVID-19 until 14 days after last potential exposure and exclude from work for 14 days after last exposure. Active monitoring means that the state or local public health authority assumes responsibility for establishing regular communication with potentially exposed people to assess for the presence of fever or respiratory symptoms (e.g., cough, shortness of breath, sore throat). For HCP with high- or medium-risk exposures, CDC recommends this communication occurs at least once each day. For full details, please see www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/guidance-risk-assesment-hcp.html.

Should postexposure prophylaxis be used for people who may have been exposed to COVID-19?

None available.

COVID-19 test results are negative in a symptomatic patient you suspected of COVID-19? What does it mean?

A negative test result for a sample collected while a person has symptoms likely means that the COVID-19 virus is not causing their current illness.

What if your hospital does not have an Airborne Infection Isolation Room (AIIR) for COVID-19 patients?

Transfer the patient to a facility that has an available AIIR. If a transfer is impractical or not medically appropriate, the patient should be cared for in a single-person room and the door should be kept closed. The room should ideally not have an exhaust that is recirculated within the building without high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filtration. Health care personnel should still use gloves, gown, respiratory and eye protection and follow all other recommended infection prevention and control practices when caring for these patients.

What if your hospital does not have enough Airborne Infection Isolation Rooms (AIIR) for COVID-19 patients?

Prioritize patients for AIIR who are symptomatic with severe illness (e.g., those requiring ventilator support).

When can patients with confirmed COVID-19 be discharged from the hospital?

Patients can be discharged from the health care facility whenever clinically indicated. Isolation should be maintained at home if the patient returns home before the time period recommended for discontinuation of hospital transmission-based precautions.

Considerations to discontinue transmission-based precautions include all of the following:

- Resolution of fever, without the use of antipyretic medication.

- Improvement in illness signs and symptoms.

- Negative rRT-PCR results from at least two consecutive sets of paired nasopharyngeal and throat swabs specimens collected at least 24 hours apart (total of four negative specimens – two nasopharyngeal and two throat) from a patient with COVID-19 are needed before discontinuing transmission-based precautions.

Should people be concerned about pets or other animals and COVID-19?

To date, CDC has not received any reports of pets or other animals becoming sick with COVID-19.

Should patients avoid contact with pets or other animals if they are sick with COVID-19?

Patients should restrict contact with pets and other animals while they are sick with COVID-19, just like they would around other people.

Does CDC recommend the use of face masks in the community to prevent COVID-19?

CDC does not recommend that people who are well wear a face mask to protect themselves from respiratory illnesses, including COVID-19. A face mask should be used by people who have COVID-19 and are showing symptoms to protect others from the risk of getting infected.

Should medical waste or general waste from health care facilities treating PUIs and patients with confirmed COVID-19 be handled any differently or need any additional disinfection?

No. CDC’s guidance states that management of laundry, food service utensils, and medical waste should be performed in accordance with routine procedures.

Can people who recover from COVID-19 be infected again?

Unknown. The immune response to COVID-19 is not yet understood.

What is the mortality rate of COVID-19, and how does it compare to the mortality rate of influenza (flu)?

The average 10-year mortality rate for flu, using CDC data, is found to be around 0.1%. Even though this percentage appears to be small, influenza is estimated to be responsible for 30,000 to 40,000 deaths annually in the U.S.

According to statistics released by the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention on Feb. 17, the mortality rate of COVID-19 is estimated to be around 2.3%. This calculation was based on cases reported through Feb. 11, and calcuated by dividing the number of coronavirus-related deaths at the time (1,023) by the number of confirmed cases (44,672) of COVID-19 infection. However, this report has its limitations, since Chinese officials have a vague way of defining who has COVID-19 infection.

The World Health Organization (WHO) currently estimates the mortality rate for COVID-19 to be between 2% and 4%.

Dr. Sitammagari is a co-medical director for quality and assistant professor of internal medicine at Atrium Health, Charlotte, N.C. He is also a physician advisor. He currently serves as treasurer for the NC-Triangle Chapter of the Society of Hospital Medicine and as an editorial board member of The Hospitalist.

Dr. Skandhan is a hospitalist and member of the Core Faculty for the Internal Medicine Residency Program at Southeast Health (SEH), Dothan Ala., and an assistant professor at the Alabama College of Osteopathic Medicine. He serves as the medical director/physician liaison for the Clinical Documentation Program at SEH and also as the director for physician integration for Southeast Health Statera Network, an Accountable Care Organization. Dr. Skandhan was a cofounder of the Wiregrass chapter of SHM and currently serves on the Advisory board. He is also a member of the editorial board of The Hospitalist.

Dr. Dahlin is a second-year internal medicine resident at Southeast Health, Dothan, Ala. She serves as her class representative and is the cochair/resident liaison for the research committee at SEH. Dr. Dahlin also serves as a resident liaison for the Wiregrass chapter of SHM.