User login

Supporting Faculty Development in Hospital Medicine: Design and Implementation of a Personalized Structured Mentoring Program

The lack of mentorship in hospital medicine has been previously documented,1-3 but there is scant literature about solutions to the problem.4 In other disciplines, data suggest that the guidance of a mentor has a positive influence on academic productivity and professional satisfaction. Mentored faculty at all levels in their careers are more successful at producing peer-reviewed publications, procuring grant support, and maintaining confidence in their career trajectory.

METHODS

The mentorship program was implemented from October 2015 to June 2016 in the Hospital Medicine Unit (HMU) of the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), a teaching affiliate of Harvard Medical School.

Program Goals, Design, and Development

Participants

Mentees had to be hired at >0.5 full-time equivalent and have 3 years or fewer of hospitalist experience.

Mentor–Mentee Matching

Mentors were paired with 1 or 2 mentees. Participant information such as history of mentorship and areas of interest for mentorship was collected. Two authors matched mentors and mentees to maximize similarities in these areas. Four mentors were paired with 2 mentees each, and 12 mentors were paired with 1 mentee each.

Mentorship Training Sessions

The program provided 3 mentorship-training lunch sessions for both mentees and mentors during the 9-month program. To enrich attendance, mentees were provided coverage for their clinical duties. The initial training session provided an opportunity to meet, articulate expectations and challenges, and develop action plans with individualized goals for the mentoring relationship. The second training session occurred at the midpoint. Pairs considered their mentorship status, evaluated their progress, and discussed strategies for optimizing their experience. At the final training session, participants reflected on their mentoring relationships, identified their extended network of mentoring support, and set expectations regarding whether the mentoring relationship would continue.

Mentorship Meetings

In addition to the training sessions, mentee–mentor pairs were expected to meet a minimum of 2 times during the formal mentorship program. CFD experts performed participant outreach via e-mail to assess progress. Mentees were given dining facility gift cards to support meetings with their mentors.

Program Evaluation

Statistical Analysis

RESULTS

Program Participation and Response Rate

Of the 25 eligible mentees, 16 (64%) participated in the mentorship program. Of the 20 eligible mentors, 12 (60%) participated. One participating mentee and 1 mentor left the institution during the intervention period. Fourteen mentees (response rate: 88%) and 9 mentors (response rate: 75%) completed the preintervention survey. Ten mentees (response rate: 63%) and 8 mentors (response rate: 67%) completed the postintervention survey.

Mentor Characteristics

Mentorship Meetings and the Mentorship Network

All participants attended at least 2 of the 3 trainings. For the mentees who completed the postintervention survey, 9 (90%) met with their mentors 3 or more additional times, and 8 (80%) were connected by their mentor to at least 1 additional faculty mentor.

Perceptions and Overall Satisfaction with Mentorship

Prior to starting the mentoring relationship, 86% of mentees and 78% of mentors anticipated that differing career goals would be a challenge to a successful mentor–mentee relationship. At the end of the program, only 30% of mentees and 38% of mentors felt that such differences were a challenge. Ninety percent of mentees and 88% of mentors were satisfied or very satisfied with their mentorship match. Forty-three percent of mentees felt supported by the HMU prior to the mentorship program, while 90% felt supported after the program. All the mentees agreed that future HMU faculty should participate in a similar program.

Impact of Mentorship on Critical Domains

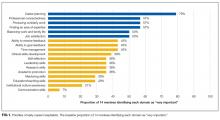

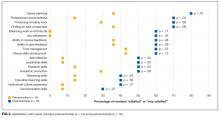

At baseline, the following domains were most commonly rated as very important by mentees: career planning, professional connectedness, producing scholarly work, finding an area of expertise, balancing work and family life, and job satisfaction (Figure 1). There was a significant improvement in composite satisfaction scores after completion of the mentorship program (54.5 ± 6.2 vs 65 ± 14.9, P = 0.02). The influence of the mentorship program on all domains is shown in Figure 2.

DISCUSSION

Our pilot structured mentorship program for junior hospitalists was feasible and led to improved satisfaction in select key career domains. Other mentoring or faculty coaching programs have been studied in several fields of medicine10-12; however, to our knowledge, there have not been published data studying a structured mentorship program for junior faculty in hospital medicine. Our intervention prioritized not only optimizing mentorship matches but also formalizing training sessions led by content experts.

After experiencing a structured mentoring relationship, most mentees felt a greater sense of support, were satisfied with their mentoring experiences, were connected to additional faculty, and had significant improvement in satisfaction in key career domains. Satisfaction with other self-identified “very important” domains, including scholarly activity, finding an area of expertise, job satisfaction, and work and family-life balance, did not significantly improve by the end of the program.

Perceived challenges to mentoring did not persist to the same degree with the implementation of a structured program. This highlights the importance of building mentorship skill sets (such as mentoring across differences and goal setting) through expert-led training sessions and perhaps also the importance of matching based on career goals.

CONCLUSION

Effective and sustainable career development requires mentorship.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank each of the participants in the HMU Mentorship Program and the MGH CFD and Division of General Internal Medicine for supporting this effort.

Disclosure

Funding was provided by the MGH DGIM and CFD. Dr. Regina O’Neill reports the following relevant financial relationship: Massachusetts General Hospital Center for Faculty Development (consultant). All other authors report no other financial or other conflicts of interest to disclose.

1. Harrison R, Hunter AJ, Sharpe B, Auerbach AD. Survey of US academic hospitalist leaders about mentorship and academic activities in hospitalist groups. J Hosp Med. 2011;6:5-9. PubMed

2. Reid MB, Misky GJ, Harrison RA, Sharpe B, Auerbach A, Glasheen JJ. Mentorship, productivity, and promotion among academic hospitalists. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27:23-27. PubMed

3. Wiese J, Centor R. The need for mentors in the odyssey of the academic hospitalist. J Hosp Med. 2011;6:1-2. PubMed

4. Howell E, Kravet S, Kisuule F, Wright SM. An innovative approach to supporting hospitalist physicians towards academic success. J Hosp Med. 2008;3:314-318. PubMed

5. Berk RA, Berg J, Mortimer R, Walton-Moss B, Yeo TP. Measuring the effectiveness of faculty mentoring relationships. Acad Med. 2005;80:66-71. PubMed

6. Jackson VA, Palepu A, Szalacha L, Caswell C, Carr PL, Inui T. “Having the right chemistry”: a qualitative study of mentoring in academic medicine. Acad Med. 2003;78:328-334. PubMed

7. Ramanan RA, Phillips RS, Davis RB, Silen W, Reede JY. Mentoring in medicine: keys to satisfaction. Am J Med. 2002;112:336-341. PubMed

8. Steven A, Oxley J, Fleming WG. Mentoring for NHS doctors: perceived benefits across the personal-professional interface. J R Soc Med. 2008;101:552-557. PubMed

9. Jha AK, Orav EJ, Zheng J, Epstein AM. Patients’ perception of hospital care in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1921-1931. PubMed

10. Pololi LH, Knight SM, Dennis K, Frankel RM. Helping medical school faculty realize their dreams: an innovative, collaborative mentoring program. Acad Med. 2002;77:377-384. PubMed

11. Sambunjak D, Straus SE, Marusic A. Mentoring in academic medicine: a systematic review. JAMA. 2006;296:1103-1115. PubMed

12. Sehgal NL, Sharpe BA, Auerbach AA, Wachter RM. Investing in the future: building an academic hospitalist faculty development program. J Hosp Med. 2011;6:161-166. PubMed

The lack of mentorship in hospital medicine has been previously documented,1-3 but there is scant literature about solutions to the problem.4 In other disciplines, data suggest that the guidance of a mentor has a positive influence on academic productivity and professional satisfaction. Mentored faculty at all levels in their careers are more successful at producing peer-reviewed publications, procuring grant support, and maintaining confidence in their career trajectory.

METHODS

The mentorship program was implemented from October 2015 to June 2016 in the Hospital Medicine Unit (HMU) of the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), a teaching affiliate of Harvard Medical School.

Program Goals, Design, and Development

Participants

Mentees had to be hired at >0.5 full-time equivalent and have 3 years or fewer of hospitalist experience.

Mentor–Mentee Matching

Mentors were paired with 1 or 2 mentees. Participant information such as history of mentorship and areas of interest for mentorship was collected. Two authors matched mentors and mentees to maximize similarities in these areas. Four mentors were paired with 2 mentees each, and 12 mentors were paired with 1 mentee each.

Mentorship Training Sessions

The program provided 3 mentorship-training lunch sessions for both mentees and mentors during the 9-month program. To enrich attendance, mentees were provided coverage for their clinical duties. The initial training session provided an opportunity to meet, articulate expectations and challenges, and develop action plans with individualized goals for the mentoring relationship. The second training session occurred at the midpoint. Pairs considered their mentorship status, evaluated their progress, and discussed strategies for optimizing their experience. At the final training session, participants reflected on their mentoring relationships, identified their extended network of mentoring support, and set expectations regarding whether the mentoring relationship would continue.

Mentorship Meetings

In addition to the training sessions, mentee–mentor pairs were expected to meet a minimum of 2 times during the formal mentorship program. CFD experts performed participant outreach via e-mail to assess progress. Mentees were given dining facility gift cards to support meetings with their mentors.

Program Evaluation

Statistical Analysis

RESULTS

Program Participation and Response Rate

Of the 25 eligible mentees, 16 (64%) participated in the mentorship program. Of the 20 eligible mentors, 12 (60%) participated. One participating mentee and 1 mentor left the institution during the intervention period. Fourteen mentees (response rate: 88%) and 9 mentors (response rate: 75%) completed the preintervention survey. Ten mentees (response rate: 63%) and 8 mentors (response rate: 67%) completed the postintervention survey.

Mentor Characteristics

Mentorship Meetings and the Mentorship Network

All participants attended at least 2 of the 3 trainings. For the mentees who completed the postintervention survey, 9 (90%) met with their mentors 3 or more additional times, and 8 (80%) were connected by their mentor to at least 1 additional faculty mentor.

Perceptions and Overall Satisfaction with Mentorship

Prior to starting the mentoring relationship, 86% of mentees and 78% of mentors anticipated that differing career goals would be a challenge to a successful mentor–mentee relationship. At the end of the program, only 30% of mentees and 38% of mentors felt that such differences were a challenge. Ninety percent of mentees and 88% of mentors were satisfied or very satisfied with their mentorship match. Forty-three percent of mentees felt supported by the HMU prior to the mentorship program, while 90% felt supported after the program. All the mentees agreed that future HMU faculty should participate in a similar program.

Impact of Mentorship on Critical Domains

At baseline, the following domains were most commonly rated as very important by mentees: career planning, professional connectedness, producing scholarly work, finding an area of expertise, balancing work and family life, and job satisfaction (Figure 1). There was a significant improvement in composite satisfaction scores after completion of the mentorship program (54.5 ± 6.2 vs 65 ± 14.9, P = 0.02). The influence of the mentorship program on all domains is shown in Figure 2.

DISCUSSION

Our pilot structured mentorship program for junior hospitalists was feasible and led to improved satisfaction in select key career domains. Other mentoring or faculty coaching programs have been studied in several fields of medicine10-12; however, to our knowledge, there have not been published data studying a structured mentorship program for junior faculty in hospital medicine. Our intervention prioritized not only optimizing mentorship matches but also formalizing training sessions led by content experts.

After experiencing a structured mentoring relationship, most mentees felt a greater sense of support, were satisfied with their mentoring experiences, were connected to additional faculty, and had significant improvement in satisfaction in key career domains. Satisfaction with other self-identified “very important” domains, including scholarly activity, finding an area of expertise, job satisfaction, and work and family-life balance, did not significantly improve by the end of the program.

Perceived challenges to mentoring did not persist to the same degree with the implementation of a structured program. This highlights the importance of building mentorship skill sets (such as mentoring across differences and goal setting) through expert-led training sessions and perhaps also the importance of matching based on career goals.

CONCLUSION

Effective and sustainable career development requires mentorship.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank each of the participants in the HMU Mentorship Program and the MGH CFD and Division of General Internal Medicine for supporting this effort.

Disclosure

Funding was provided by the MGH DGIM and CFD. Dr. Regina O’Neill reports the following relevant financial relationship: Massachusetts General Hospital Center for Faculty Development (consultant). All other authors report no other financial or other conflicts of interest to disclose.

The lack of mentorship in hospital medicine has been previously documented,1-3 but there is scant literature about solutions to the problem.4 In other disciplines, data suggest that the guidance of a mentor has a positive influence on academic productivity and professional satisfaction. Mentored faculty at all levels in their careers are more successful at producing peer-reviewed publications, procuring grant support, and maintaining confidence in their career trajectory.

METHODS

The mentorship program was implemented from October 2015 to June 2016 in the Hospital Medicine Unit (HMU) of the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), a teaching affiliate of Harvard Medical School.

Program Goals, Design, and Development

Participants

Mentees had to be hired at >0.5 full-time equivalent and have 3 years or fewer of hospitalist experience.

Mentor–Mentee Matching

Mentors were paired with 1 or 2 mentees. Participant information such as history of mentorship and areas of interest for mentorship was collected. Two authors matched mentors and mentees to maximize similarities in these areas. Four mentors were paired with 2 mentees each, and 12 mentors were paired with 1 mentee each.

Mentorship Training Sessions

The program provided 3 mentorship-training lunch sessions for both mentees and mentors during the 9-month program. To enrich attendance, mentees were provided coverage for their clinical duties. The initial training session provided an opportunity to meet, articulate expectations and challenges, and develop action plans with individualized goals for the mentoring relationship. The second training session occurred at the midpoint. Pairs considered their mentorship status, evaluated their progress, and discussed strategies for optimizing their experience. At the final training session, participants reflected on their mentoring relationships, identified their extended network of mentoring support, and set expectations regarding whether the mentoring relationship would continue.

Mentorship Meetings

In addition to the training sessions, mentee–mentor pairs were expected to meet a minimum of 2 times during the formal mentorship program. CFD experts performed participant outreach via e-mail to assess progress. Mentees were given dining facility gift cards to support meetings with their mentors.

Program Evaluation

Statistical Analysis

RESULTS

Program Participation and Response Rate

Of the 25 eligible mentees, 16 (64%) participated in the mentorship program. Of the 20 eligible mentors, 12 (60%) participated. One participating mentee and 1 mentor left the institution during the intervention period. Fourteen mentees (response rate: 88%) and 9 mentors (response rate: 75%) completed the preintervention survey. Ten mentees (response rate: 63%) and 8 mentors (response rate: 67%) completed the postintervention survey.

Mentor Characteristics

Mentorship Meetings and the Mentorship Network

All participants attended at least 2 of the 3 trainings. For the mentees who completed the postintervention survey, 9 (90%) met with their mentors 3 or more additional times, and 8 (80%) were connected by their mentor to at least 1 additional faculty mentor.

Perceptions and Overall Satisfaction with Mentorship

Prior to starting the mentoring relationship, 86% of mentees and 78% of mentors anticipated that differing career goals would be a challenge to a successful mentor–mentee relationship. At the end of the program, only 30% of mentees and 38% of mentors felt that such differences were a challenge. Ninety percent of mentees and 88% of mentors were satisfied or very satisfied with their mentorship match. Forty-three percent of mentees felt supported by the HMU prior to the mentorship program, while 90% felt supported after the program. All the mentees agreed that future HMU faculty should participate in a similar program.

Impact of Mentorship on Critical Domains

At baseline, the following domains were most commonly rated as very important by mentees: career planning, professional connectedness, producing scholarly work, finding an area of expertise, balancing work and family life, and job satisfaction (Figure 1). There was a significant improvement in composite satisfaction scores after completion of the mentorship program (54.5 ± 6.2 vs 65 ± 14.9, P = 0.02). The influence of the mentorship program on all domains is shown in Figure 2.

DISCUSSION

Our pilot structured mentorship program for junior hospitalists was feasible and led to improved satisfaction in select key career domains. Other mentoring or faculty coaching programs have been studied in several fields of medicine10-12; however, to our knowledge, there have not been published data studying a structured mentorship program for junior faculty in hospital medicine. Our intervention prioritized not only optimizing mentorship matches but also formalizing training sessions led by content experts.

After experiencing a structured mentoring relationship, most mentees felt a greater sense of support, were satisfied with their mentoring experiences, were connected to additional faculty, and had significant improvement in satisfaction in key career domains. Satisfaction with other self-identified “very important” domains, including scholarly activity, finding an area of expertise, job satisfaction, and work and family-life balance, did not significantly improve by the end of the program.

Perceived challenges to mentoring did not persist to the same degree with the implementation of a structured program. This highlights the importance of building mentorship skill sets (such as mentoring across differences and goal setting) through expert-led training sessions and perhaps also the importance of matching based on career goals.

CONCLUSION

Effective and sustainable career development requires mentorship.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank each of the participants in the HMU Mentorship Program and the MGH CFD and Division of General Internal Medicine for supporting this effort.

Disclosure

Funding was provided by the MGH DGIM and CFD. Dr. Regina O’Neill reports the following relevant financial relationship: Massachusetts General Hospital Center for Faculty Development (consultant). All other authors report no other financial or other conflicts of interest to disclose.

1. Harrison R, Hunter AJ, Sharpe B, Auerbach AD. Survey of US academic hospitalist leaders about mentorship and academic activities in hospitalist groups. J Hosp Med. 2011;6:5-9. PubMed

2. Reid MB, Misky GJ, Harrison RA, Sharpe B, Auerbach A, Glasheen JJ. Mentorship, productivity, and promotion among academic hospitalists. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27:23-27. PubMed

3. Wiese J, Centor R. The need for mentors in the odyssey of the academic hospitalist. J Hosp Med. 2011;6:1-2. PubMed

4. Howell E, Kravet S, Kisuule F, Wright SM. An innovative approach to supporting hospitalist physicians towards academic success. J Hosp Med. 2008;3:314-318. PubMed

5. Berk RA, Berg J, Mortimer R, Walton-Moss B, Yeo TP. Measuring the effectiveness of faculty mentoring relationships. Acad Med. 2005;80:66-71. PubMed

6. Jackson VA, Palepu A, Szalacha L, Caswell C, Carr PL, Inui T. “Having the right chemistry”: a qualitative study of mentoring in academic medicine. Acad Med. 2003;78:328-334. PubMed

7. Ramanan RA, Phillips RS, Davis RB, Silen W, Reede JY. Mentoring in medicine: keys to satisfaction. Am J Med. 2002;112:336-341. PubMed

8. Steven A, Oxley J, Fleming WG. Mentoring for NHS doctors: perceived benefits across the personal-professional interface. J R Soc Med. 2008;101:552-557. PubMed

9. Jha AK, Orav EJ, Zheng J, Epstein AM. Patients’ perception of hospital care in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1921-1931. PubMed

10. Pololi LH, Knight SM, Dennis K, Frankel RM. Helping medical school faculty realize their dreams: an innovative, collaborative mentoring program. Acad Med. 2002;77:377-384. PubMed

11. Sambunjak D, Straus SE, Marusic A. Mentoring in academic medicine: a systematic review. JAMA. 2006;296:1103-1115. PubMed

12. Sehgal NL, Sharpe BA, Auerbach AA, Wachter RM. Investing in the future: building an academic hospitalist faculty development program. J Hosp Med. 2011;6:161-166. PubMed

1. Harrison R, Hunter AJ, Sharpe B, Auerbach AD. Survey of US academic hospitalist leaders about mentorship and academic activities in hospitalist groups. J Hosp Med. 2011;6:5-9. PubMed

2. Reid MB, Misky GJ, Harrison RA, Sharpe B, Auerbach A, Glasheen JJ. Mentorship, productivity, and promotion among academic hospitalists. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27:23-27. PubMed

3. Wiese J, Centor R. The need for mentors in the odyssey of the academic hospitalist. J Hosp Med. 2011;6:1-2. PubMed

4. Howell E, Kravet S, Kisuule F, Wright SM. An innovative approach to supporting hospitalist physicians towards academic success. J Hosp Med. 2008;3:314-318. PubMed

5. Berk RA, Berg J, Mortimer R, Walton-Moss B, Yeo TP. Measuring the effectiveness of faculty mentoring relationships. Acad Med. 2005;80:66-71. PubMed

6. Jackson VA, Palepu A, Szalacha L, Caswell C, Carr PL, Inui T. “Having the right chemistry”: a qualitative study of mentoring in academic medicine. Acad Med. 2003;78:328-334. PubMed

7. Ramanan RA, Phillips RS, Davis RB, Silen W, Reede JY. Mentoring in medicine: keys to satisfaction. Am J Med. 2002;112:336-341. PubMed

8. Steven A, Oxley J, Fleming WG. Mentoring for NHS doctors: perceived benefits across the personal-professional interface. J R Soc Med. 2008;101:552-557. PubMed

9. Jha AK, Orav EJ, Zheng J, Epstein AM. Patients’ perception of hospital care in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1921-1931. PubMed

10. Pololi LH, Knight SM, Dennis K, Frankel RM. Helping medical school faculty realize their dreams: an innovative, collaborative mentoring program. Acad Med. 2002;77:377-384. PubMed

11. Sambunjak D, Straus SE, Marusic A. Mentoring in academic medicine: a systematic review. JAMA. 2006;296:1103-1115. PubMed

12. Sehgal NL, Sharpe BA, Auerbach AA, Wachter RM. Investing in the future: building an academic hospitalist faculty development program. J Hosp Med. 2011;6:161-166. PubMed

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine