User login

Crusted Demodicosis in an Immunocompetent Patient

To the Editor:

Demodicosis is an infection of humans caused by species of the genus of saprophytic mites Demodex (most commonly Demodex brevis and Demodex folliculorum) that feed on the pilosebaceous unit.1Demodex mites are believed to be a commensal species in humans; an increase in mite concentration or mite penetration of the dermis, however, can cause a shift from a commensal to a pathologic form.2 Demodicosis manifests in a variety of forms, including pityriasis folliculorum, rosacealike demodicosis, and demodicosis gravis. The likelihood of colonization increases with age; the mite rarely is observed in children but is found at a rate approaching 100% in the elderly population.3 It is hypothesized that manifestation of disease might be due to a decrease in immune function or an inherited HLA antigen that causes local immunosuppression.4

A 51-year-old man who was otherwise healthy presented to our clinic with a crusting rash on the face of 9 weeks’ duration. The rash began a few days after he demolished a rotting wooden shed in his backyard. Lesions began as pustules on the left cheek, which then developed notable crusting over the next 5 to 7 days and spread to involve the forehead, nose, and right cheek (Figure 1A).

The patient had no underlying immunosuppressive disease; a human immunodeficiency virus screen, complete blood cell count, and tests of hepatic function were all unremarkable. He denied a history of frequent or recurrent sinopulmonary infections, skin infections, or infectious diarrheal illnesses. He had been seen by his primary care physician who had treated him for herpes zoster without improvement.

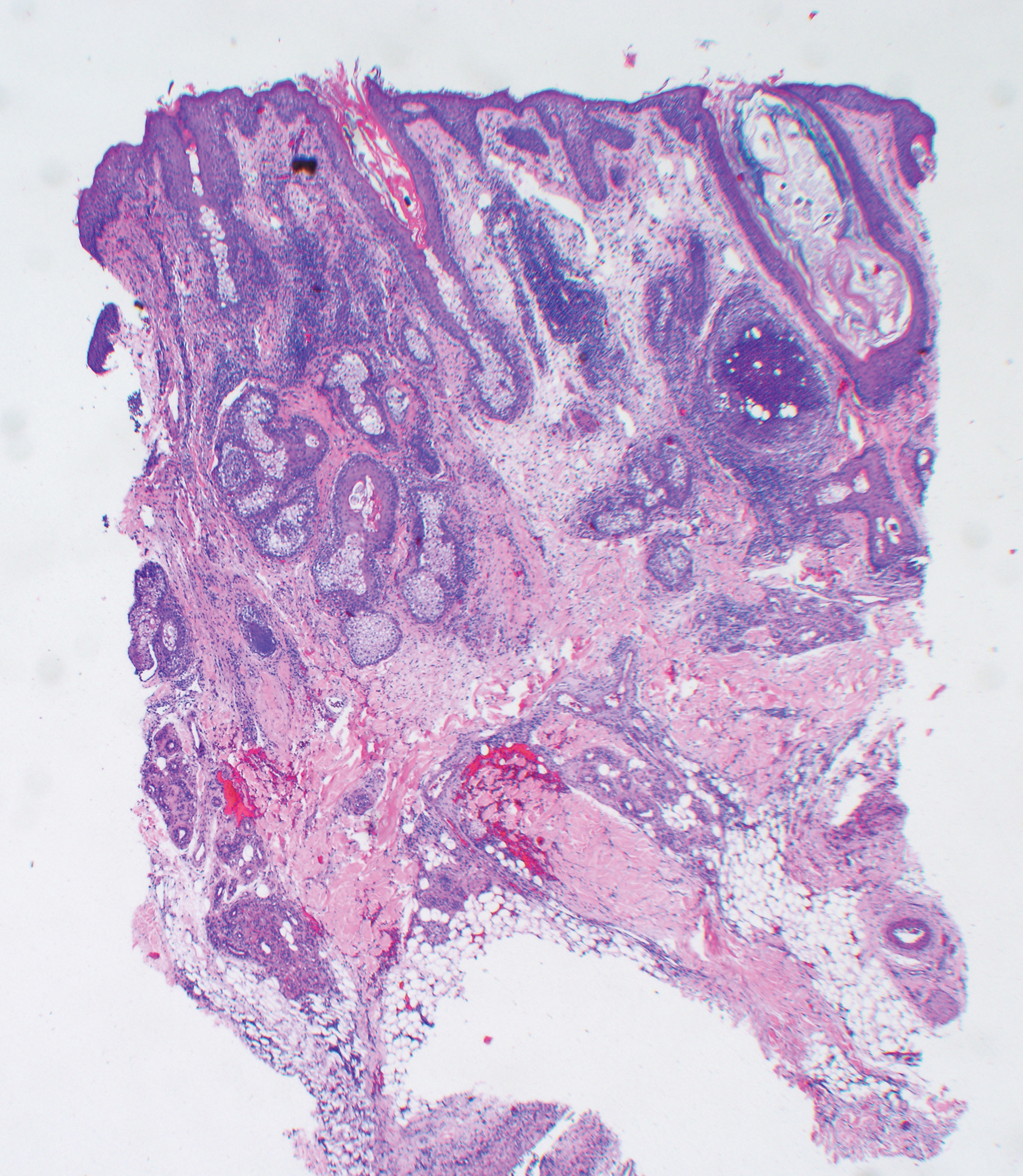

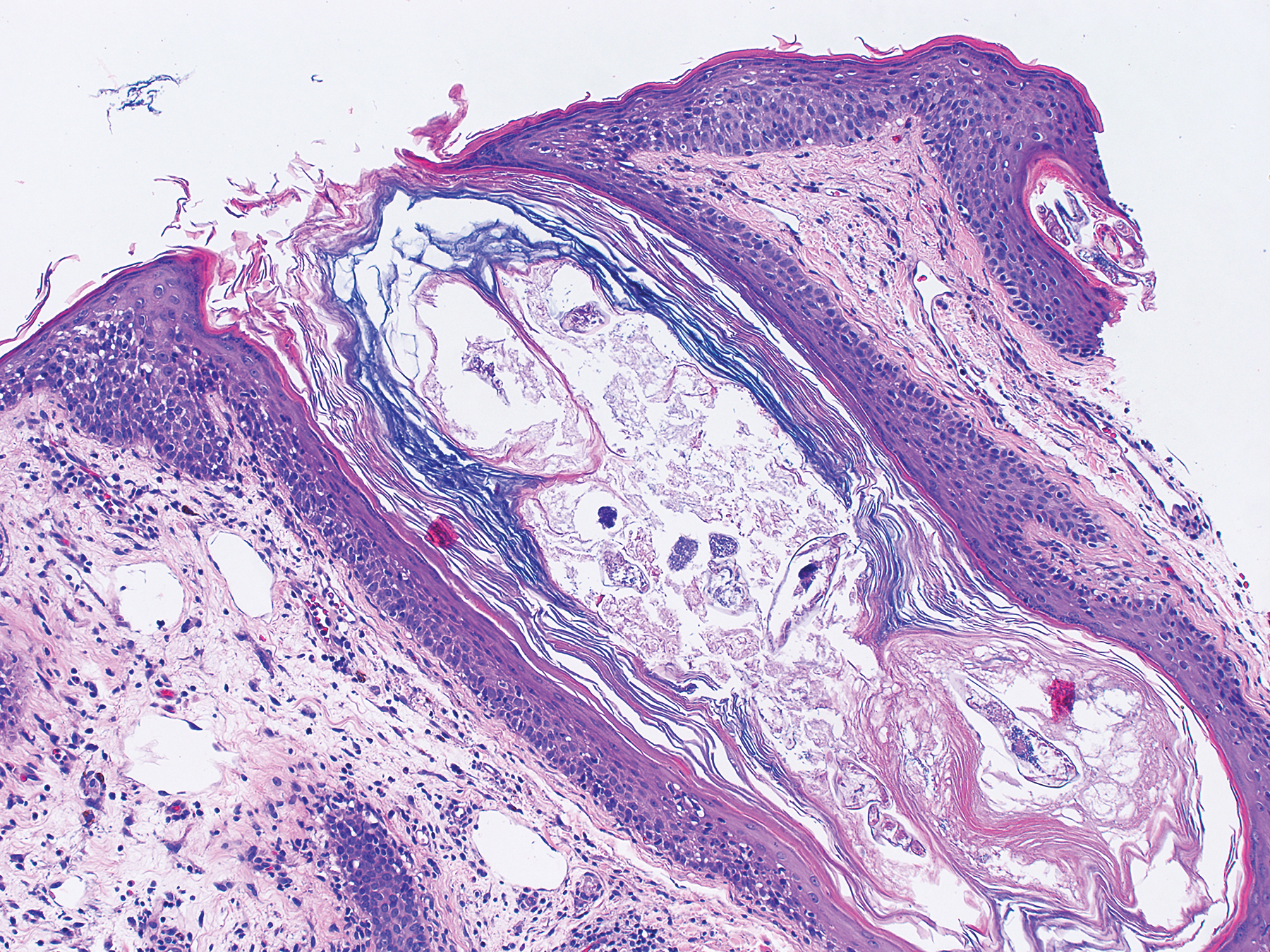

At our initial evaluation, biopsy was performed; specimens were sent for histopathologic analysis and culture. Findings included a dermal neutrophilic inflammation, a dense perivascular and perifollicular lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate with foci of neutrophilic pustules within the follicles (Figure 2), numerous intrafollicular Demodex mites (Figure 3), perifollicular vague noncaseating granuloma, and mild sebaceous hyperplasia. Grocott methenamine-silver stain and acid-fast bacilli stain were negative.

Review of clinical and pathological data yielded a final diagnosis of crusted demodicosis with a background of rosacea. The patient was ultimately treated with a single dose of oral ivermectin 15 mg with a second dose 7 days later in addition to daily application of ivermectin cream 1% to affected areas of his rash. He had notable improvement with this regimen, with complete resolution within 6 weeks (Figure 1B). The patient noted mild recurrence 14 to 21 days after discontinuing topical ivermectin.

The 2 species of Demodex that cause disease in humans each behave distinctively: D folliculorum, with a cigar-shaped body, favors superficial hair follicles; D brevis, a smaller form, burrows deeper into skin where it feeds on the pilosebaceous unit.1 Colonization occurs through direct skin-skin contact that begins as early as infancy and becomes more common with age due to development of sebaceous glands, the main source of nourishment for the mites.2

Demodicosis is classified as primary and secondary. In a prospective study of patients with clinical findings of demodicosis, Akilov et al1 discovered that the 2 forms can be differentiated by skin distribution, seasonality, mite species, and preexisting dermatoses. Primary demodicosis is categorized by sudden onset of symptoms on healthy skin, usually the face. Secondary demodicosis develops progressively in patients with preexisting skin disease, such as rosacea, and can have a broader distribution, involving the face and trunk.2 Clinical manifestations of demodicosis are broad and include pruritic papulopustular, nodulocystic, crusted, and abscesslike lesions.5

Most cases of demodicosis reported in the literature are associated with either local or systemic immunosuppression.6-8 In a case report, an otherwise immunocompetent child developed facial demodicosis after local immunosuppression from chronic use of 2 topical steroid agents.9

Demodex infestation can be diagnosed using a variety of methods, including standardized skin surface biopsy, punch biopsy, and potassium hydroxide analysis. Standardized skin surface biopsy is the preferred method to diagnose demodicosis because it is noninvasive and samples the superficial follicle where Demodex mites typically reside. Diagnosis is made by identifying 5 or more Demodex mites in a low-power field or more than 5 mites per square centimeter in standardized skin surface biopsy.2 Other potential diagnostic tools reported in the literature include dermoscopy and confocal laser scanning microscopy.10,11

There is no standard therapeutic regimen for demodicosis because evidence-based trials regarding the efficacy of treatments are lacking. Oral ivermectin 200 µg/kg in a single dose is considered the preferred treatment; it can be combined with oral erythromycin, topical permethrin, or topical metronidazole.5-7,9

Our case is unique, as crusted demodicosis developed in an immunocompetent adult. Demodicosis usually causes severe eruptions in immunocompromised persons, with only 1 case report detailing a papulopustular rash in an immunocompetent adult.12,13

The pathogenesis of demodicosis remains unclear. Many mechanisms have been hypothesized to play a role in its pathogenesis, including mechanical obstruction of hair follicles, hypersensitivity reaction to Demodex mites, immune dysregulation, and a foreign-body granulomatous reaction to the skeleton of the mite.2,3 Our patient’s particular infestation could have been caused by an exuberant reaction to Demodex; however, it is likely that many factors played a role in his disease process to cause an increase in mite density and subsequent manifestations of disease.

- Akilov OE, Butov YS, Mumcuoglu KY. A clinico-pathological approach to the classification of human demodicosis. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2005;3:607-614.

- Karincaoglu Y, Bayram N, Aycan O, et al. The clinical importance of Demodex folliculorum presenting with nonspecific facial signs and symptoms. J Dermatol. 2004;31:618-626.

- Baima B, Sticherling M. Demodicidosis revisited. Acta Derm Venereol. 2002;82:3-6.

- Noy ML, Hughes S, Bunker CB. Another face of demodicosis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2016;41:958-959.

- Chen W, Plewig G. Human demodicosis: revisit and a proposed classification. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:1219-1225.

- Morrás PG, Santos SP, Imedio IL, et al. Rosacea-like demodicidosis in an immunocompromised child. Pediatr Dermatol. 2003;20:28-30.

- Damian D, Rogers M. Demodex infestation in a child with leukaemia: treatment with ivermectin and permethrin. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:724-726.

- Clyti E, Nacher M, Sainte-Marie D, et al. Ivermectin treatment of three cases of demodecidosis during human immunodeficiency virus infection. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1066-1068.

- Guerrero-González GA, Herz-Ruelas ME, Gómez-Flores M, et al. Crusted demodicosis in an immunocompetent pediatric patient. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2014;2014:458046.

- Friedman P, Sabban EC, Cabo H. Usefulness of dermoscopy in the diagnosis and monitoring treatment of demodicidosis. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2017;7:35-38.

- Harmelin Y, Delaunay P, Erfan N, et al. Interest of confocal laser scanning microscopy for the diagnosis and treatment monitoring of demodicosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:255-257.

- Elston CA, Elston DM. Demodex mites. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32:739-743.

- Kaur T, Jindal N, Bansal R, et al. Facial demodicidosis: a diagnostic challenge. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:72-73.

To the Editor:

Demodicosis is an infection of humans caused by species of the genus of saprophytic mites Demodex (most commonly Demodex brevis and Demodex folliculorum) that feed on the pilosebaceous unit.1Demodex mites are believed to be a commensal species in humans; an increase in mite concentration or mite penetration of the dermis, however, can cause a shift from a commensal to a pathologic form.2 Demodicosis manifests in a variety of forms, including pityriasis folliculorum, rosacealike demodicosis, and demodicosis gravis. The likelihood of colonization increases with age; the mite rarely is observed in children but is found at a rate approaching 100% in the elderly population.3 It is hypothesized that manifestation of disease might be due to a decrease in immune function or an inherited HLA antigen that causes local immunosuppression.4

A 51-year-old man who was otherwise healthy presented to our clinic with a crusting rash on the face of 9 weeks’ duration. The rash began a few days after he demolished a rotting wooden shed in his backyard. Lesions began as pustules on the left cheek, which then developed notable crusting over the next 5 to 7 days and spread to involve the forehead, nose, and right cheek (Figure 1A).

The patient had no underlying immunosuppressive disease; a human immunodeficiency virus screen, complete blood cell count, and tests of hepatic function were all unremarkable. He denied a history of frequent or recurrent sinopulmonary infections, skin infections, or infectious diarrheal illnesses. He had been seen by his primary care physician who had treated him for herpes zoster without improvement.

At our initial evaluation, biopsy was performed; specimens were sent for histopathologic analysis and culture. Findings included a dermal neutrophilic inflammation, a dense perivascular and perifollicular lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate with foci of neutrophilic pustules within the follicles (Figure 2), numerous intrafollicular Demodex mites (Figure 3), perifollicular vague noncaseating granuloma, and mild sebaceous hyperplasia. Grocott methenamine-silver stain and acid-fast bacilli stain were negative.

Review of clinical and pathological data yielded a final diagnosis of crusted demodicosis with a background of rosacea. The patient was ultimately treated with a single dose of oral ivermectin 15 mg with a second dose 7 days later in addition to daily application of ivermectin cream 1% to affected areas of his rash. He had notable improvement with this regimen, with complete resolution within 6 weeks (Figure 1B). The patient noted mild recurrence 14 to 21 days after discontinuing topical ivermectin.

The 2 species of Demodex that cause disease in humans each behave distinctively: D folliculorum, with a cigar-shaped body, favors superficial hair follicles; D brevis, a smaller form, burrows deeper into skin where it feeds on the pilosebaceous unit.1 Colonization occurs through direct skin-skin contact that begins as early as infancy and becomes more common with age due to development of sebaceous glands, the main source of nourishment for the mites.2

Demodicosis is classified as primary and secondary. In a prospective study of patients with clinical findings of demodicosis, Akilov et al1 discovered that the 2 forms can be differentiated by skin distribution, seasonality, mite species, and preexisting dermatoses. Primary demodicosis is categorized by sudden onset of symptoms on healthy skin, usually the face. Secondary demodicosis develops progressively in patients with preexisting skin disease, such as rosacea, and can have a broader distribution, involving the face and trunk.2 Clinical manifestations of demodicosis are broad and include pruritic papulopustular, nodulocystic, crusted, and abscesslike lesions.5

Most cases of demodicosis reported in the literature are associated with either local or systemic immunosuppression.6-8 In a case report, an otherwise immunocompetent child developed facial demodicosis after local immunosuppression from chronic use of 2 topical steroid agents.9

Demodex infestation can be diagnosed using a variety of methods, including standardized skin surface biopsy, punch biopsy, and potassium hydroxide analysis. Standardized skin surface biopsy is the preferred method to diagnose demodicosis because it is noninvasive and samples the superficial follicle where Demodex mites typically reside. Diagnosis is made by identifying 5 or more Demodex mites in a low-power field or more than 5 mites per square centimeter in standardized skin surface biopsy.2 Other potential diagnostic tools reported in the literature include dermoscopy and confocal laser scanning microscopy.10,11

There is no standard therapeutic regimen for demodicosis because evidence-based trials regarding the efficacy of treatments are lacking. Oral ivermectin 200 µg/kg in a single dose is considered the preferred treatment; it can be combined with oral erythromycin, topical permethrin, or topical metronidazole.5-7,9

Our case is unique, as crusted demodicosis developed in an immunocompetent adult. Demodicosis usually causes severe eruptions in immunocompromised persons, with only 1 case report detailing a papulopustular rash in an immunocompetent adult.12,13

The pathogenesis of demodicosis remains unclear. Many mechanisms have been hypothesized to play a role in its pathogenesis, including mechanical obstruction of hair follicles, hypersensitivity reaction to Demodex mites, immune dysregulation, and a foreign-body granulomatous reaction to the skeleton of the mite.2,3 Our patient’s particular infestation could have been caused by an exuberant reaction to Demodex; however, it is likely that many factors played a role in his disease process to cause an increase in mite density and subsequent manifestations of disease.

To the Editor:

Demodicosis is an infection of humans caused by species of the genus of saprophytic mites Demodex (most commonly Demodex brevis and Demodex folliculorum) that feed on the pilosebaceous unit.1Demodex mites are believed to be a commensal species in humans; an increase in mite concentration or mite penetration of the dermis, however, can cause a shift from a commensal to a pathologic form.2 Demodicosis manifests in a variety of forms, including pityriasis folliculorum, rosacealike demodicosis, and demodicosis gravis. The likelihood of colonization increases with age; the mite rarely is observed in children but is found at a rate approaching 100% in the elderly population.3 It is hypothesized that manifestation of disease might be due to a decrease in immune function or an inherited HLA antigen that causes local immunosuppression.4

A 51-year-old man who was otherwise healthy presented to our clinic with a crusting rash on the face of 9 weeks’ duration. The rash began a few days after he demolished a rotting wooden shed in his backyard. Lesions began as pustules on the left cheek, which then developed notable crusting over the next 5 to 7 days and spread to involve the forehead, nose, and right cheek (Figure 1A).

The patient had no underlying immunosuppressive disease; a human immunodeficiency virus screen, complete blood cell count, and tests of hepatic function were all unremarkable. He denied a history of frequent or recurrent sinopulmonary infections, skin infections, or infectious diarrheal illnesses. He had been seen by his primary care physician who had treated him for herpes zoster without improvement.

At our initial evaluation, biopsy was performed; specimens were sent for histopathologic analysis and culture. Findings included a dermal neutrophilic inflammation, a dense perivascular and perifollicular lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate with foci of neutrophilic pustules within the follicles (Figure 2), numerous intrafollicular Demodex mites (Figure 3), perifollicular vague noncaseating granuloma, and mild sebaceous hyperplasia. Grocott methenamine-silver stain and acid-fast bacilli stain were negative.

Review of clinical and pathological data yielded a final diagnosis of crusted demodicosis with a background of rosacea. The patient was ultimately treated with a single dose of oral ivermectin 15 mg with a second dose 7 days later in addition to daily application of ivermectin cream 1% to affected areas of his rash. He had notable improvement with this regimen, with complete resolution within 6 weeks (Figure 1B). The patient noted mild recurrence 14 to 21 days after discontinuing topical ivermectin.

The 2 species of Demodex that cause disease in humans each behave distinctively: D folliculorum, with a cigar-shaped body, favors superficial hair follicles; D brevis, a smaller form, burrows deeper into skin where it feeds on the pilosebaceous unit.1 Colonization occurs through direct skin-skin contact that begins as early as infancy and becomes more common with age due to development of sebaceous glands, the main source of nourishment for the mites.2

Demodicosis is classified as primary and secondary. In a prospective study of patients with clinical findings of demodicosis, Akilov et al1 discovered that the 2 forms can be differentiated by skin distribution, seasonality, mite species, and preexisting dermatoses. Primary demodicosis is categorized by sudden onset of symptoms on healthy skin, usually the face. Secondary demodicosis develops progressively in patients with preexisting skin disease, such as rosacea, and can have a broader distribution, involving the face and trunk.2 Clinical manifestations of demodicosis are broad and include pruritic papulopustular, nodulocystic, crusted, and abscesslike lesions.5

Most cases of demodicosis reported in the literature are associated with either local or systemic immunosuppression.6-8 In a case report, an otherwise immunocompetent child developed facial demodicosis after local immunosuppression from chronic use of 2 topical steroid agents.9

Demodex infestation can be diagnosed using a variety of methods, including standardized skin surface biopsy, punch biopsy, and potassium hydroxide analysis. Standardized skin surface biopsy is the preferred method to diagnose demodicosis because it is noninvasive and samples the superficial follicle where Demodex mites typically reside. Diagnosis is made by identifying 5 or more Demodex mites in a low-power field or more than 5 mites per square centimeter in standardized skin surface biopsy.2 Other potential diagnostic tools reported in the literature include dermoscopy and confocal laser scanning microscopy.10,11

There is no standard therapeutic regimen for demodicosis because evidence-based trials regarding the efficacy of treatments are lacking. Oral ivermectin 200 µg/kg in a single dose is considered the preferred treatment; it can be combined with oral erythromycin, topical permethrin, or topical metronidazole.5-7,9

Our case is unique, as crusted demodicosis developed in an immunocompetent adult. Demodicosis usually causes severe eruptions in immunocompromised persons, with only 1 case report detailing a papulopustular rash in an immunocompetent adult.12,13

The pathogenesis of demodicosis remains unclear. Many mechanisms have been hypothesized to play a role in its pathogenesis, including mechanical obstruction of hair follicles, hypersensitivity reaction to Demodex mites, immune dysregulation, and a foreign-body granulomatous reaction to the skeleton of the mite.2,3 Our patient’s particular infestation could have been caused by an exuberant reaction to Demodex; however, it is likely that many factors played a role in his disease process to cause an increase in mite density and subsequent manifestations of disease.

- Akilov OE, Butov YS, Mumcuoglu KY. A clinico-pathological approach to the classification of human demodicosis. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2005;3:607-614.

- Karincaoglu Y, Bayram N, Aycan O, et al. The clinical importance of Demodex folliculorum presenting with nonspecific facial signs and symptoms. J Dermatol. 2004;31:618-626.

- Baima B, Sticherling M. Demodicidosis revisited. Acta Derm Venereol. 2002;82:3-6.

- Noy ML, Hughes S, Bunker CB. Another face of demodicosis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2016;41:958-959.

- Chen W, Plewig G. Human demodicosis: revisit and a proposed classification. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:1219-1225.

- Morrás PG, Santos SP, Imedio IL, et al. Rosacea-like demodicidosis in an immunocompromised child. Pediatr Dermatol. 2003;20:28-30.

- Damian D, Rogers M. Demodex infestation in a child with leukaemia: treatment with ivermectin and permethrin. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:724-726.

- Clyti E, Nacher M, Sainte-Marie D, et al. Ivermectin treatment of three cases of demodecidosis during human immunodeficiency virus infection. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1066-1068.

- Guerrero-González GA, Herz-Ruelas ME, Gómez-Flores M, et al. Crusted demodicosis in an immunocompetent pediatric patient. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2014;2014:458046.

- Friedman P, Sabban EC, Cabo H. Usefulness of dermoscopy in the diagnosis and monitoring treatment of demodicidosis. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2017;7:35-38.

- Harmelin Y, Delaunay P, Erfan N, et al. Interest of confocal laser scanning microscopy for the diagnosis and treatment monitoring of demodicosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:255-257.

- Elston CA, Elston DM. Demodex mites. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32:739-743.

- Kaur T, Jindal N, Bansal R, et al. Facial demodicidosis: a diagnostic challenge. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:72-73.

- Akilov OE, Butov YS, Mumcuoglu KY. A clinico-pathological approach to the classification of human demodicosis. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2005;3:607-614.

- Karincaoglu Y, Bayram N, Aycan O, et al. The clinical importance of Demodex folliculorum presenting with nonspecific facial signs and symptoms. J Dermatol. 2004;31:618-626.

- Baima B, Sticherling M. Demodicidosis revisited. Acta Derm Venereol. 2002;82:3-6.

- Noy ML, Hughes S, Bunker CB. Another face of demodicosis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2016;41:958-959.

- Chen W, Plewig G. Human demodicosis: revisit and a proposed classification. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:1219-1225.

- Morrás PG, Santos SP, Imedio IL, et al. Rosacea-like demodicidosis in an immunocompromised child. Pediatr Dermatol. 2003;20:28-30.

- Damian D, Rogers M. Demodex infestation in a child with leukaemia: treatment with ivermectin and permethrin. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:724-726.

- Clyti E, Nacher M, Sainte-Marie D, et al. Ivermectin treatment of three cases of demodecidosis during human immunodeficiency virus infection. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1066-1068.

- Guerrero-González GA, Herz-Ruelas ME, Gómez-Flores M, et al. Crusted demodicosis in an immunocompetent pediatric patient. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2014;2014:458046.

- Friedman P, Sabban EC, Cabo H. Usefulness of dermoscopy in the diagnosis and monitoring treatment of demodicidosis. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2017;7:35-38.

- Harmelin Y, Delaunay P, Erfan N, et al. Interest of confocal laser scanning microscopy for the diagnosis and treatment monitoring of demodicosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:255-257.

- Elston CA, Elston DM. Demodex mites. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32:739-743.

- Kaur T, Jindal N, Bansal R, et al. Facial demodicidosis: a diagnostic challenge. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:72-73.

Practice Points

- The Demodex mite, believed to be a commensal species in humans, has the ability to shift to a pathologic form in immunocompromised patients.

- Demodicosis can manifest in a variety of forms including pityriasis folliculorum, rosacealike demodicosis, and demodicosis gravis.

Segmental distribution of nodules on trunk

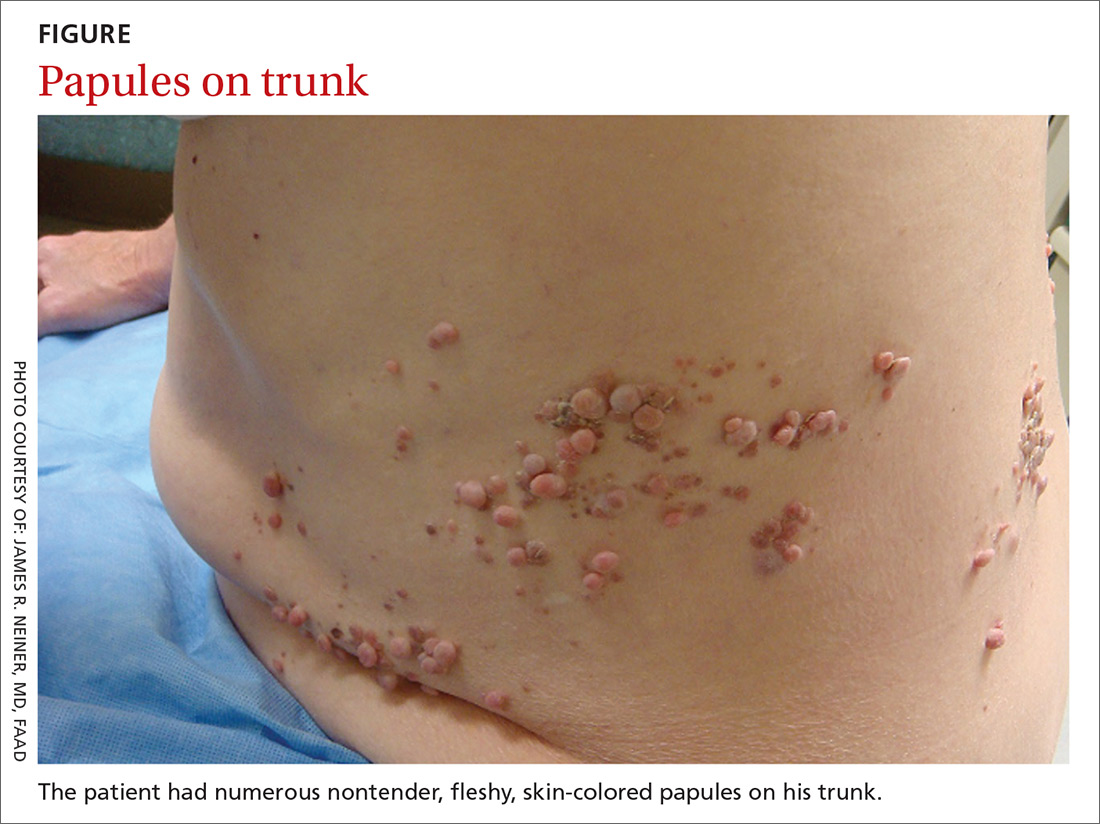

A 70-year-old Caucasian man presented with a longstanding history of numerous nontender, fleshy, skin-colored papules on his trunk, ranging from 3 to 8 mm in size (FIGURE). They were noted incidentally during an examination of unrelated nonhealing lesions on the patient’s left cheek. He said the lesions on his trunk first appeared when he was 28 years old and had continued to grow in size and number. The patient said his son had at least one similar lesion on his upper back, but otherwise there was no family history of these lesions.

A biopsy was performed on one of the nodules.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Segmental neurofibromatosis

Dermatopathologic evaluation of the tissue sample indicated that the lesion was a neurofibroma, and clinical correlation fine-tuned the diagnosis to segmental neurofibromatosis (NF). The diagnosis of segmental NF is clinical with biopsy to confirm the lesions are neurofibromas. Segmental NF is a mosaic form of neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) that results from a postzygotic mutation of the NF1 gene. While NF1 is a relatively common neurocutaneous disorder that occurs with a frequency of one in 3000,1 segmental NF is more rare, with an estimated prevalence of one in 40,000.2

NF1 often follows an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern, although up to 50% of patients with NF1 arise de novo from spontaneous mutations.3 NF1 is characterized by multiple café-au-lait macules, axillary freckling, neurofibromas, and Lisch nodules (pigmented iris hamartomas).

Systemic findings that are associated with NF1 include malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors, optic gliomas, and vasculopathy.3 While patients with segmental NF may exhibit some of these same findings, the distribution of neurofibromas is often limited to one dermatome. Additionally, patients with segmental NF typically do not exhibit extracutaneous lesions, systemic involvement, or a family history of NF.

Rule out these dermatomal lesions

This case highlights a unique pattern of neoplasm development along a dermatome, an area of skin where innervation derives from a single spinal nerve. Symptoms that follow a dermatome often point to a pathology involving the related nerve root.

This differs from Blaschko lines, which form a specific surface pattern that is believed to reflect the migration of embryonic skin cells. Blaschko lines do not follow any known vascular, nervous, or lymphatic structures of the skin. Interestingly, when patients with segmental NF have associated pigmentary lesions, such as café-au-lait macules, these lesions may border Blaschko lines.

Herpes zoster, also known as shingles, is the most common infectious process that presents in a dermatomal pattern. Herpes zoster is caused by reactivation of the varicella-zoster virus, which lies within the dorsal root ganglion of a spinal nerve. This condition commonly results in a dermatomal distribution of vesicles/bullae on an erythematous base.

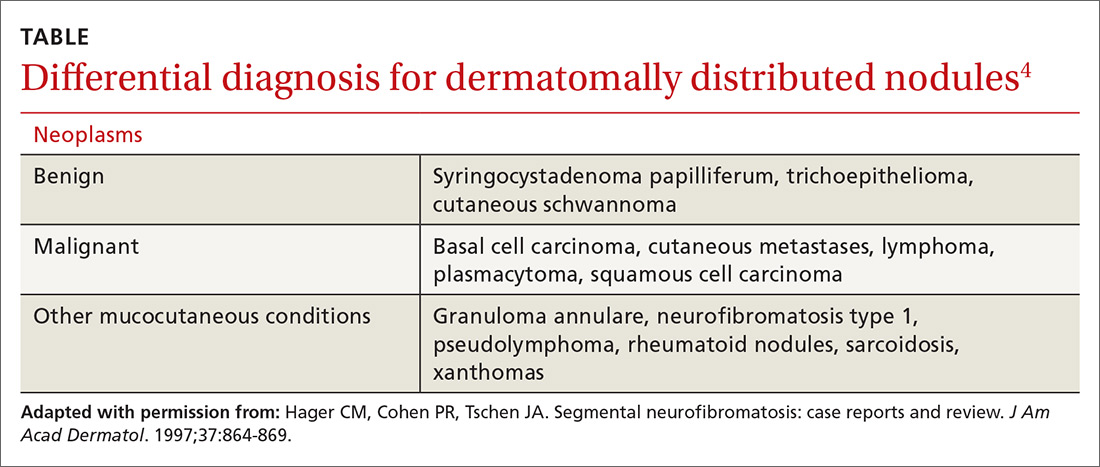

Neoplasms—including common cutaneous malignancies, such as basal cell carcinoma, as well as rare benign cutaneous conditions, such as cutaneous schwannoma, may have a distribution similar to that of segmental NF. A biopsy can help distinguish the diagnosis. See the TABLE4 for a complete differential diagnosis for dermatomally distributed nodules.

Classifying neurofibromatosis

It’s important to classify the type of NF in order to get a better handle on the patient’s prognosis and to facilitate genetic counseling. In particular, the much more common NF1 comes with an increased risk of systemic findings such as malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors, optic gliomas, other gliomas, and leukemia. Few patients with segmental NF, on the other hand, will have these systemic findings.4 Segmental NF treatment typically focuses on symptomatic management or cosmetic concerns.

Our patient did not have any of the systemic complications that occasionally occur with segmental NF as discussed above, so no medical treatment was required. We informed him that the cutaneous and subcutaneous neurofibromas do not require removal unless there is pain, bleeding, disfigurement, or signs of malignant transformation. Our patient was not interested in removal of the nodules for cosmetic reasons, so we recommended follow-up as needed.

CORRESPONDENCE

Thomas M. Beachkofsky, MD, FAAD, San Antonio Uniformed Services Health Education Consortium, Brooke Army Medical Center, 3551 Roger Brooke Dr, Fort Sam Houston, TX 78234; thomas.beachkofsky@us.af.mil.

1. Riccardi VM. Von Recklinghausen neurofibromatosis. N Engl J Med. 1981;305:1617-1627.

2. Ruggieri M, Huson SM. The clinical and diagnostic implications of mosaicism in the neurofibromatoses. Neurology. 2001;56:1433-1443.

3. Jett K, Friedman JM. Clinical and genetic aspects of neurofibromatosis 1. Genet Med. 2010;12:1-11.

4. Hager CM, Cohen PR, Tschen JA. Segmental neurofibromatosis: case reports and review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:864-869.

A 70-year-old Caucasian man presented with a longstanding history of numerous nontender, fleshy, skin-colored papules on his trunk, ranging from 3 to 8 mm in size (FIGURE). They were noted incidentally during an examination of unrelated nonhealing lesions on the patient’s left cheek. He said the lesions on his trunk first appeared when he was 28 years old and had continued to grow in size and number. The patient said his son had at least one similar lesion on his upper back, but otherwise there was no family history of these lesions.

A biopsy was performed on one of the nodules.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Segmental neurofibromatosis

Dermatopathologic evaluation of the tissue sample indicated that the lesion was a neurofibroma, and clinical correlation fine-tuned the diagnosis to segmental neurofibromatosis (NF). The diagnosis of segmental NF is clinical with biopsy to confirm the lesions are neurofibromas. Segmental NF is a mosaic form of neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) that results from a postzygotic mutation of the NF1 gene. While NF1 is a relatively common neurocutaneous disorder that occurs with a frequency of one in 3000,1 segmental NF is more rare, with an estimated prevalence of one in 40,000.2

NF1 often follows an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern, although up to 50% of patients with NF1 arise de novo from spontaneous mutations.3 NF1 is characterized by multiple café-au-lait macules, axillary freckling, neurofibromas, and Lisch nodules (pigmented iris hamartomas).

Systemic findings that are associated with NF1 include malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors, optic gliomas, and vasculopathy.3 While patients with segmental NF may exhibit some of these same findings, the distribution of neurofibromas is often limited to one dermatome. Additionally, patients with segmental NF typically do not exhibit extracutaneous lesions, systemic involvement, or a family history of NF.

Rule out these dermatomal lesions

This case highlights a unique pattern of neoplasm development along a dermatome, an area of skin where innervation derives from a single spinal nerve. Symptoms that follow a dermatome often point to a pathology involving the related nerve root.

This differs from Blaschko lines, which form a specific surface pattern that is believed to reflect the migration of embryonic skin cells. Blaschko lines do not follow any known vascular, nervous, or lymphatic structures of the skin. Interestingly, when patients with segmental NF have associated pigmentary lesions, such as café-au-lait macules, these lesions may border Blaschko lines.

Herpes zoster, also known as shingles, is the most common infectious process that presents in a dermatomal pattern. Herpes zoster is caused by reactivation of the varicella-zoster virus, which lies within the dorsal root ganglion of a spinal nerve. This condition commonly results in a dermatomal distribution of vesicles/bullae on an erythematous base.

Neoplasms—including common cutaneous malignancies, such as basal cell carcinoma, as well as rare benign cutaneous conditions, such as cutaneous schwannoma, may have a distribution similar to that of segmental NF. A biopsy can help distinguish the diagnosis. See the TABLE4 for a complete differential diagnosis for dermatomally distributed nodules.

Classifying neurofibromatosis

It’s important to classify the type of NF in order to get a better handle on the patient’s prognosis and to facilitate genetic counseling. In particular, the much more common NF1 comes with an increased risk of systemic findings such as malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors, optic gliomas, other gliomas, and leukemia. Few patients with segmental NF, on the other hand, will have these systemic findings.4 Segmental NF treatment typically focuses on symptomatic management or cosmetic concerns.

Our patient did not have any of the systemic complications that occasionally occur with segmental NF as discussed above, so no medical treatment was required. We informed him that the cutaneous and subcutaneous neurofibromas do not require removal unless there is pain, bleeding, disfigurement, or signs of malignant transformation. Our patient was not interested in removal of the nodules for cosmetic reasons, so we recommended follow-up as needed.

CORRESPONDENCE

Thomas M. Beachkofsky, MD, FAAD, San Antonio Uniformed Services Health Education Consortium, Brooke Army Medical Center, 3551 Roger Brooke Dr, Fort Sam Houston, TX 78234; thomas.beachkofsky@us.af.mil.

A 70-year-old Caucasian man presented with a longstanding history of numerous nontender, fleshy, skin-colored papules on his trunk, ranging from 3 to 8 mm in size (FIGURE). They were noted incidentally during an examination of unrelated nonhealing lesions on the patient’s left cheek. He said the lesions on his trunk first appeared when he was 28 years old and had continued to grow in size and number. The patient said his son had at least one similar lesion on his upper back, but otherwise there was no family history of these lesions.

A biopsy was performed on one of the nodules.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Segmental neurofibromatosis

Dermatopathologic evaluation of the tissue sample indicated that the lesion was a neurofibroma, and clinical correlation fine-tuned the diagnosis to segmental neurofibromatosis (NF). The diagnosis of segmental NF is clinical with biopsy to confirm the lesions are neurofibromas. Segmental NF is a mosaic form of neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) that results from a postzygotic mutation of the NF1 gene. While NF1 is a relatively common neurocutaneous disorder that occurs with a frequency of one in 3000,1 segmental NF is more rare, with an estimated prevalence of one in 40,000.2

NF1 often follows an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern, although up to 50% of patients with NF1 arise de novo from spontaneous mutations.3 NF1 is characterized by multiple café-au-lait macules, axillary freckling, neurofibromas, and Lisch nodules (pigmented iris hamartomas).

Systemic findings that are associated with NF1 include malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors, optic gliomas, and vasculopathy.3 While patients with segmental NF may exhibit some of these same findings, the distribution of neurofibromas is often limited to one dermatome. Additionally, patients with segmental NF typically do not exhibit extracutaneous lesions, systemic involvement, or a family history of NF.

Rule out these dermatomal lesions

This case highlights a unique pattern of neoplasm development along a dermatome, an area of skin where innervation derives from a single spinal nerve. Symptoms that follow a dermatome often point to a pathology involving the related nerve root.

This differs from Blaschko lines, which form a specific surface pattern that is believed to reflect the migration of embryonic skin cells. Blaschko lines do not follow any known vascular, nervous, or lymphatic structures of the skin. Interestingly, when patients with segmental NF have associated pigmentary lesions, such as café-au-lait macules, these lesions may border Blaschko lines.

Herpes zoster, also known as shingles, is the most common infectious process that presents in a dermatomal pattern. Herpes zoster is caused by reactivation of the varicella-zoster virus, which lies within the dorsal root ganglion of a spinal nerve. This condition commonly results in a dermatomal distribution of vesicles/bullae on an erythematous base.

Neoplasms—including common cutaneous malignancies, such as basal cell carcinoma, as well as rare benign cutaneous conditions, such as cutaneous schwannoma, may have a distribution similar to that of segmental NF. A biopsy can help distinguish the diagnosis. See the TABLE4 for a complete differential diagnosis for dermatomally distributed nodules.

Classifying neurofibromatosis

It’s important to classify the type of NF in order to get a better handle on the patient’s prognosis and to facilitate genetic counseling. In particular, the much more common NF1 comes with an increased risk of systemic findings such as malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors, optic gliomas, other gliomas, and leukemia. Few patients with segmental NF, on the other hand, will have these systemic findings.4 Segmental NF treatment typically focuses on symptomatic management or cosmetic concerns.

Our patient did not have any of the systemic complications that occasionally occur with segmental NF as discussed above, so no medical treatment was required. We informed him that the cutaneous and subcutaneous neurofibromas do not require removal unless there is pain, bleeding, disfigurement, or signs of malignant transformation. Our patient was not interested in removal of the nodules for cosmetic reasons, so we recommended follow-up as needed.

CORRESPONDENCE

Thomas M. Beachkofsky, MD, FAAD, San Antonio Uniformed Services Health Education Consortium, Brooke Army Medical Center, 3551 Roger Brooke Dr, Fort Sam Houston, TX 78234; thomas.beachkofsky@us.af.mil.

1. Riccardi VM. Von Recklinghausen neurofibromatosis. N Engl J Med. 1981;305:1617-1627.

2. Ruggieri M, Huson SM. The clinical and diagnostic implications of mosaicism in the neurofibromatoses. Neurology. 2001;56:1433-1443.

3. Jett K, Friedman JM. Clinical and genetic aspects of neurofibromatosis 1. Genet Med. 2010;12:1-11.

4. Hager CM, Cohen PR, Tschen JA. Segmental neurofibromatosis: case reports and review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:864-869.

1. Riccardi VM. Von Recklinghausen neurofibromatosis. N Engl J Med. 1981;305:1617-1627.

2. Ruggieri M, Huson SM. The clinical and diagnostic implications of mosaicism in the neurofibromatoses. Neurology. 2001;56:1433-1443.

3. Jett K, Friedman JM. Clinical and genetic aspects of neurofibromatosis 1. Genet Med. 2010;12:1-11.

4. Hager CM, Cohen PR, Tschen JA. Segmental neurofibromatosis: case reports and review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:864-869.