User login

Imaging algorithm may improve stroke treatment selection

SAN DIEGO – A Massachusetts General Hospital neuroimaging algorithm that is used to help in the selection of appropriate treatment for patients with severe ischemic strokes caused by anterior circulation occlusions led to significant improvements in mortality and outcomes and a decrease in the number of stroke interventions after it was implemented at the Cleveland Clinic, according to Dr. Ramon Gilberto Gonzalez.

With a few exceptions, the algorithm does not use perfusion imaging, either by MRI or CT, in the assessment of anterior circulation occlusion (ACO) patients for intravenous tissue plasminogen activator (TPA) or endovascular therapy.

"One of the challenges in imaging stroke is that it is very heterogeneous. You don’t know what is going to show up in your emergency department. It is important to formulate an imaging program that can optimize all the information you get from all patients, whether they need intra-arterial therapy or just watchful waiting. A system is needed that is efficient for all patients, and that is a challenge," Dr. Gonzalez said at the annual meeting of the American Society of Neuroradiology. He is lead author of the paper describing the algorithm and director of the neuroradiology division at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), Boston.

The algorithm was developed from both experience and evidence, Dr. Gonzalez explained. Individual neuroradiology and neurology faculty from MGH presented the best evidence from the literature and clinical experience regarding imaging methods and the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS). Other faculty and fellows who heard the presentations met to weigh the evidence and make recommendations. The methods were rated on such metrics as sensitivity and specificity, value for patient care, usability in the acute setting, work flow, repeatability, reliability, and clinical efficacy.

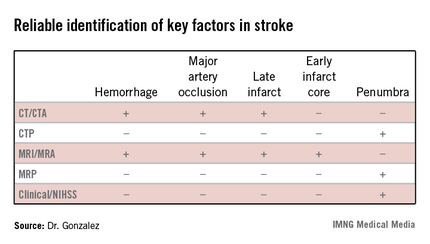

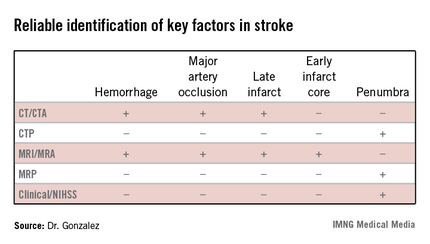

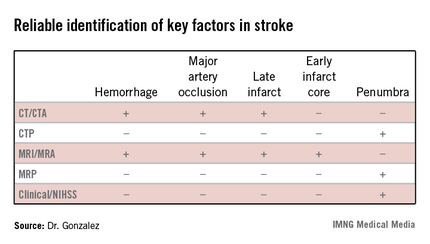

The algorithm reflected how well different imaging methods provided information on key factors in stroke. "In addition to time and hemorrhage, we must consider how much of the brain has already died [the core] and how much of the brain is likely to die if you do not do anything to help" the penumbra. Each imaging method has benefits and weaknesses for different stroke parameters, Dr. Gonzalez said. (See table.) CT/CT angiography (CTA) and MRI/MR angiography (MRA) were found to be useful for demonstrating hemorrhage, major artery occlusion, and late infarct, while only MRI/MRA helped visualize the early infarct core.

In the algorithm, all patients presenting with a stroke syndrome (possible hemorrhage or large infarct) receive a neurological exam, including the NIHSS. "The single most important parameter is the neurological exam," according to Dr. Gonzalez, which he said can determine an overall size of the penumbra and core combined. "The neurologic exam is just as good as CTP [CT perfusion] or MRP [MRI perfusion]."

According to the stroke imaging algorithm (J. Neurointervent. Surg. 2013;5:i7-12), the first imaging study should be a noncontrast CT (NCCT), followed by a CTA if a proximal occlusion is accessible and the patient is eligible for MRI. If the NCCT does not demonstrate a hemorrhage or large hypodensity, and the patient is within the time window, TPA is prepared while the CTA is performed, and the infusion is started. If the patient has a distal internal carotid artery and/or proximal middle cerebral artery occlusion, he will undergo diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI). Patients with DWI lesions less than 70 mL in volume are sent for intra-arterial therapy as long as they meet clinical and medical criteria. "DWI is really the only method we have to determine the core volume with sufficient precision to be able to make good clinical decisions," Dr. Gonzalez said.

Perfusion CT and perfusion MR are not part of the recommended imaging workup, with some exceptions. "For many years, radiologists thought you could substitute DWI with CT perfusion. We came to the conclusion that you cannot," Dr. Gonzalez said. The reviewing panel found that there was no or poor evidence that CTP could be used for early estimation of the infarct core or penumbra, and had no proven role in selecting ACO patients for IV thrombolysis or endovascular therapy. Similarly, they found the evidence indicated that MRP had no proven role in selecting ACO patients for endovascular therapy. Perfusion imaging may be appropriate if patients cannot be scanned by an MRI or are not otherwise eligible for intra-arterial therapy, or if perfusion data are needed for another reason.

After adoption of the algorithm, the number of CT perfusion exams performed at MGH on stroke patients dropped from 40-50 per month to about 10 per month. No discernible effects on the rate of good outcomes (P = .67) or median modified Rankin Scale score (P = .85) were found.

A little more than a year of testing at the Cleveland Clinic showed that the algorithm resulted in a significant reduction in mortality and improvement of modified Rankin Scale scores independent of the treatment received. Interestingly, the number of interventions for stroke decreased by 40% as patient selection through imaging targeted patients more likely to benefit and excluded those not suitable for intra-arterial therapy (Stroke 2012;43:A161).

Dr. Gonzalez reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – A Massachusetts General Hospital neuroimaging algorithm that is used to help in the selection of appropriate treatment for patients with severe ischemic strokes caused by anterior circulation occlusions led to significant improvements in mortality and outcomes and a decrease in the number of stroke interventions after it was implemented at the Cleveland Clinic, according to Dr. Ramon Gilberto Gonzalez.

With a few exceptions, the algorithm does not use perfusion imaging, either by MRI or CT, in the assessment of anterior circulation occlusion (ACO) patients for intravenous tissue plasminogen activator (TPA) or endovascular therapy.

"One of the challenges in imaging stroke is that it is very heterogeneous. You don’t know what is going to show up in your emergency department. It is important to formulate an imaging program that can optimize all the information you get from all patients, whether they need intra-arterial therapy or just watchful waiting. A system is needed that is efficient for all patients, and that is a challenge," Dr. Gonzalez said at the annual meeting of the American Society of Neuroradiology. He is lead author of the paper describing the algorithm and director of the neuroradiology division at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), Boston.

The algorithm was developed from both experience and evidence, Dr. Gonzalez explained. Individual neuroradiology and neurology faculty from MGH presented the best evidence from the literature and clinical experience regarding imaging methods and the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS). Other faculty and fellows who heard the presentations met to weigh the evidence and make recommendations. The methods were rated on such metrics as sensitivity and specificity, value for patient care, usability in the acute setting, work flow, repeatability, reliability, and clinical efficacy.

The algorithm reflected how well different imaging methods provided information on key factors in stroke. "In addition to time and hemorrhage, we must consider how much of the brain has already died [the core] and how much of the brain is likely to die if you do not do anything to help" the penumbra. Each imaging method has benefits and weaknesses for different stroke parameters, Dr. Gonzalez said. (See table.) CT/CT angiography (CTA) and MRI/MR angiography (MRA) were found to be useful for demonstrating hemorrhage, major artery occlusion, and late infarct, while only MRI/MRA helped visualize the early infarct core.

In the algorithm, all patients presenting with a stroke syndrome (possible hemorrhage or large infarct) receive a neurological exam, including the NIHSS. "The single most important parameter is the neurological exam," according to Dr. Gonzalez, which he said can determine an overall size of the penumbra and core combined. "The neurologic exam is just as good as CTP [CT perfusion] or MRP [MRI perfusion]."

According to the stroke imaging algorithm (J. Neurointervent. Surg. 2013;5:i7-12), the first imaging study should be a noncontrast CT (NCCT), followed by a CTA if a proximal occlusion is accessible and the patient is eligible for MRI. If the NCCT does not demonstrate a hemorrhage or large hypodensity, and the patient is within the time window, TPA is prepared while the CTA is performed, and the infusion is started. If the patient has a distal internal carotid artery and/or proximal middle cerebral artery occlusion, he will undergo diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI). Patients with DWI lesions less than 70 mL in volume are sent for intra-arterial therapy as long as they meet clinical and medical criteria. "DWI is really the only method we have to determine the core volume with sufficient precision to be able to make good clinical decisions," Dr. Gonzalez said.

Perfusion CT and perfusion MR are not part of the recommended imaging workup, with some exceptions. "For many years, radiologists thought you could substitute DWI with CT perfusion. We came to the conclusion that you cannot," Dr. Gonzalez said. The reviewing panel found that there was no or poor evidence that CTP could be used for early estimation of the infarct core or penumbra, and had no proven role in selecting ACO patients for IV thrombolysis or endovascular therapy. Similarly, they found the evidence indicated that MRP had no proven role in selecting ACO patients for endovascular therapy. Perfusion imaging may be appropriate if patients cannot be scanned by an MRI or are not otherwise eligible for intra-arterial therapy, or if perfusion data are needed for another reason.

After adoption of the algorithm, the number of CT perfusion exams performed at MGH on stroke patients dropped from 40-50 per month to about 10 per month. No discernible effects on the rate of good outcomes (P = .67) or median modified Rankin Scale score (P = .85) were found.

A little more than a year of testing at the Cleveland Clinic showed that the algorithm resulted in a significant reduction in mortality and improvement of modified Rankin Scale scores independent of the treatment received. Interestingly, the number of interventions for stroke decreased by 40% as patient selection through imaging targeted patients more likely to benefit and excluded those not suitable for intra-arterial therapy (Stroke 2012;43:A161).

Dr. Gonzalez reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – A Massachusetts General Hospital neuroimaging algorithm that is used to help in the selection of appropriate treatment for patients with severe ischemic strokes caused by anterior circulation occlusions led to significant improvements in mortality and outcomes and a decrease in the number of stroke interventions after it was implemented at the Cleveland Clinic, according to Dr. Ramon Gilberto Gonzalez.

With a few exceptions, the algorithm does not use perfusion imaging, either by MRI or CT, in the assessment of anterior circulation occlusion (ACO) patients for intravenous tissue plasminogen activator (TPA) or endovascular therapy.

"One of the challenges in imaging stroke is that it is very heterogeneous. You don’t know what is going to show up in your emergency department. It is important to formulate an imaging program that can optimize all the information you get from all patients, whether they need intra-arterial therapy or just watchful waiting. A system is needed that is efficient for all patients, and that is a challenge," Dr. Gonzalez said at the annual meeting of the American Society of Neuroradiology. He is lead author of the paper describing the algorithm and director of the neuroradiology division at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), Boston.

The algorithm was developed from both experience and evidence, Dr. Gonzalez explained. Individual neuroradiology and neurology faculty from MGH presented the best evidence from the literature and clinical experience regarding imaging methods and the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS). Other faculty and fellows who heard the presentations met to weigh the evidence and make recommendations. The methods were rated on such metrics as sensitivity and specificity, value for patient care, usability in the acute setting, work flow, repeatability, reliability, and clinical efficacy.

The algorithm reflected how well different imaging methods provided information on key factors in stroke. "In addition to time and hemorrhage, we must consider how much of the brain has already died [the core] and how much of the brain is likely to die if you do not do anything to help" the penumbra. Each imaging method has benefits and weaknesses for different stroke parameters, Dr. Gonzalez said. (See table.) CT/CT angiography (CTA) and MRI/MR angiography (MRA) were found to be useful for demonstrating hemorrhage, major artery occlusion, and late infarct, while only MRI/MRA helped visualize the early infarct core.

In the algorithm, all patients presenting with a stroke syndrome (possible hemorrhage or large infarct) receive a neurological exam, including the NIHSS. "The single most important parameter is the neurological exam," according to Dr. Gonzalez, which he said can determine an overall size of the penumbra and core combined. "The neurologic exam is just as good as CTP [CT perfusion] or MRP [MRI perfusion]."

According to the stroke imaging algorithm (J. Neurointervent. Surg. 2013;5:i7-12), the first imaging study should be a noncontrast CT (NCCT), followed by a CTA if a proximal occlusion is accessible and the patient is eligible for MRI. If the NCCT does not demonstrate a hemorrhage or large hypodensity, and the patient is within the time window, TPA is prepared while the CTA is performed, and the infusion is started. If the patient has a distal internal carotid artery and/or proximal middle cerebral artery occlusion, he will undergo diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI). Patients with DWI lesions less than 70 mL in volume are sent for intra-arterial therapy as long as they meet clinical and medical criteria. "DWI is really the only method we have to determine the core volume with sufficient precision to be able to make good clinical decisions," Dr. Gonzalez said.

Perfusion CT and perfusion MR are not part of the recommended imaging workup, with some exceptions. "For many years, radiologists thought you could substitute DWI with CT perfusion. We came to the conclusion that you cannot," Dr. Gonzalez said. The reviewing panel found that there was no or poor evidence that CTP could be used for early estimation of the infarct core or penumbra, and had no proven role in selecting ACO patients for IV thrombolysis or endovascular therapy. Similarly, they found the evidence indicated that MRP had no proven role in selecting ACO patients for endovascular therapy. Perfusion imaging may be appropriate if patients cannot be scanned by an MRI or are not otherwise eligible for intra-arterial therapy, or if perfusion data are needed for another reason.

After adoption of the algorithm, the number of CT perfusion exams performed at MGH on stroke patients dropped from 40-50 per month to about 10 per month. No discernible effects on the rate of good outcomes (P = .67) or median modified Rankin Scale score (P = .85) were found.

A little more than a year of testing at the Cleveland Clinic showed that the algorithm resulted in a significant reduction in mortality and improvement of modified Rankin Scale scores independent of the treatment received. Interestingly, the number of interventions for stroke decreased by 40% as patient selection through imaging targeted patients more likely to benefit and excluded those not suitable for intra-arterial therapy (Stroke 2012;43:A161).

Dr. Gonzalez reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE ASNR ANNUAL MEETING

Transfers may have worse ischemic stroke outcomes

SAN DIEGO – Acute ischemic stroke patients who required transfer to a comprehensive stroke center in order to receive intra-arterial therapy were significantly more likely to have worse functional outcomes at 90 days than were patients who presented directly to such centers in a retrospective analysis of 116 patients.

The poor outcome of the transferred patients was independent of baseline risk factors, stroke severity, time to intra-arterial therapy, and whether the process was a success or the patient had complications, according to Dr. Ali Shaibani, who presented the findings at the annual meeting of the American Society of Neuroradiology.

"The time to intervention is critical for AIS [acute ischemic stroke] patients who are candidates for intra-arterial therapy. Access to endovascular therapy is often limited to comprehensive stroke centers. An increasing number of institutions are transferring AIS patients for therapy. The outcome for this subset of patients who are being transferred has not been studied well," said Dr. Shaibani of the departments of radiology and neurologic surgery at Northwestern University, Chicago.

This retrospective analysis analyzed 116 AIS patients deemed eligible for intra-arterial therapy who were seen at four Chicago-area medical centers. More than half (58.6%) were transferred from outside institutions.

Dr. Shaibani and his colleagues found that transfer patients tended to be younger than nontransfers (59 years vs. 69 years, P = .002) and were less likely to have had a history of prior stroke (3% vs. 22%, P = .002) or cardiac problems (18% vs. 37%, P = .040). Transfer patients had worse National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale scores at baseline (20 vs. 17, P = .005) and were more likely to have internal carotid artery occlusions (45.6% vs. 22.9%, P = .012). No differences between groups were found for THRIVE (Totaled Health Risks in Vascular Events) scores, a clinical scoring system designed to help clinicians predict a patient’s chances of achieving a good outcome after AIS.

At 90 days after intra-arterial therapy, only 16% of transfer patients had a good functional outcome, as defined by a modified Rankin Scale score of 0-2. Significantly more nontransferred patients (60%) had a good outcome (P less than .001). In a multivariate analysis, transfer status was an independent predictor of poor functional outcome (adjusted odds ratio = 0.05; 95% confidence interval, 0.011-0.222), after the findings were adjusted for relevant covariates such as baseline risk factors, stroke severity, time to intra-arterial therapy, or procedural success or complications. No differences between groups were found for median symptom onset to groin puncture times, rates of successful recanalization (defined as thrombolysis in cerebral infarction grade 2b or higher), or the presence of symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage.

Dr. Shaibani said it was not clear what factors were contributing to the findings. He said future work should explore the influence of baseline/final infarct volume, premorbid functional status, and poststroke care.

Dr. Shaibani reported that he had no relevant financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Acute ischemic stroke patients who required transfer to a comprehensive stroke center in order to receive intra-arterial therapy were significantly more likely to have worse functional outcomes at 90 days than were patients who presented directly to such centers in a retrospective analysis of 116 patients.

The poor outcome of the transferred patients was independent of baseline risk factors, stroke severity, time to intra-arterial therapy, and whether the process was a success or the patient had complications, according to Dr. Ali Shaibani, who presented the findings at the annual meeting of the American Society of Neuroradiology.

"The time to intervention is critical for AIS [acute ischemic stroke] patients who are candidates for intra-arterial therapy. Access to endovascular therapy is often limited to comprehensive stroke centers. An increasing number of institutions are transferring AIS patients for therapy. The outcome for this subset of patients who are being transferred has not been studied well," said Dr. Shaibani of the departments of radiology and neurologic surgery at Northwestern University, Chicago.

This retrospective analysis analyzed 116 AIS patients deemed eligible for intra-arterial therapy who were seen at four Chicago-area medical centers. More than half (58.6%) were transferred from outside institutions.

Dr. Shaibani and his colleagues found that transfer patients tended to be younger than nontransfers (59 years vs. 69 years, P = .002) and were less likely to have had a history of prior stroke (3% vs. 22%, P = .002) or cardiac problems (18% vs. 37%, P = .040). Transfer patients had worse National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale scores at baseline (20 vs. 17, P = .005) and were more likely to have internal carotid artery occlusions (45.6% vs. 22.9%, P = .012). No differences between groups were found for THRIVE (Totaled Health Risks in Vascular Events) scores, a clinical scoring system designed to help clinicians predict a patient’s chances of achieving a good outcome after AIS.

At 90 days after intra-arterial therapy, only 16% of transfer patients had a good functional outcome, as defined by a modified Rankin Scale score of 0-2. Significantly more nontransferred patients (60%) had a good outcome (P less than .001). In a multivariate analysis, transfer status was an independent predictor of poor functional outcome (adjusted odds ratio = 0.05; 95% confidence interval, 0.011-0.222), after the findings were adjusted for relevant covariates such as baseline risk factors, stroke severity, time to intra-arterial therapy, or procedural success or complications. No differences between groups were found for median symptom onset to groin puncture times, rates of successful recanalization (defined as thrombolysis in cerebral infarction grade 2b or higher), or the presence of symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage.

Dr. Shaibani said it was not clear what factors were contributing to the findings. He said future work should explore the influence of baseline/final infarct volume, premorbid functional status, and poststroke care.

Dr. Shaibani reported that he had no relevant financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Acute ischemic stroke patients who required transfer to a comprehensive stroke center in order to receive intra-arterial therapy were significantly more likely to have worse functional outcomes at 90 days than were patients who presented directly to such centers in a retrospective analysis of 116 patients.

The poor outcome of the transferred patients was independent of baseline risk factors, stroke severity, time to intra-arterial therapy, and whether the process was a success or the patient had complications, according to Dr. Ali Shaibani, who presented the findings at the annual meeting of the American Society of Neuroradiology.

"The time to intervention is critical for AIS [acute ischemic stroke] patients who are candidates for intra-arterial therapy. Access to endovascular therapy is often limited to comprehensive stroke centers. An increasing number of institutions are transferring AIS patients for therapy. The outcome for this subset of patients who are being transferred has not been studied well," said Dr. Shaibani of the departments of radiology and neurologic surgery at Northwestern University, Chicago.

This retrospective analysis analyzed 116 AIS patients deemed eligible for intra-arterial therapy who were seen at four Chicago-area medical centers. More than half (58.6%) were transferred from outside institutions.

Dr. Shaibani and his colleagues found that transfer patients tended to be younger than nontransfers (59 years vs. 69 years, P = .002) and were less likely to have had a history of prior stroke (3% vs. 22%, P = .002) or cardiac problems (18% vs. 37%, P = .040). Transfer patients had worse National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale scores at baseline (20 vs. 17, P = .005) and were more likely to have internal carotid artery occlusions (45.6% vs. 22.9%, P = .012). No differences between groups were found for THRIVE (Totaled Health Risks in Vascular Events) scores, a clinical scoring system designed to help clinicians predict a patient’s chances of achieving a good outcome after AIS.

At 90 days after intra-arterial therapy, only 16% of transfer patients had a good functional outcome, as defined by a modified Rankin Scale score of 0-2. Significantly more nontransferred patients (60%) had a good outcome (P less than .001). In a multivariate analysis, transfer status was an independent predictor of poor functional outcome (adjusted odds ratio = 0.05; 95% confidence interval, 0.011-0.222), after the findings were adjusted for relevant covariates such as baseline risk factors, stroke severity, time to intra-arterial therapy, or procedural success or complications. No differences between groups were found for median symptom onset to groin puncture times, rates of successful recanalization (defined as thrombolysis in cerebral infarction grade 2b or higher), or the presence of symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage.

Dr. Shaibani said it was not clear what factors were contributing to the findings. He said future work should explore the influence of baseline/final infarct volume, premorbid functional status, and poststroke care.

Dr. Shaibani reported that he had no relevant financial disclosures.

AT THE ASNR ANNUAL MEETING

Major finding: Significantly fewer patients who were transferred from an outside institution to a comprehensive stroke center had good functional outcomes at 90 days than did nontransferred patients (modified Rankin Scale score of 0-2; 16% vs. 60%, respectively), independent of baseline risk factors, stroke severity, time to intra-arterial therapy, and procedural success/complications.

Data source: A retrospective study of 116 patients with acute ischemic stroke who were eligible for intra-arterial therapy.

Disclosures: Dr. Shaibani said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

The rheumatologist's role in the care of the limping child

NEW YORK – A timely diagnosis of a child presenting with a limp is essential because of the wide variety of possible causes, including benign disease such as a mild injury, a chronic disabling disease such as juvenile idiopathic arthritis, or a life-threatening infection or malignancy. It may be up to the pediatric rheumatologist to discriminate among the possible causes of the limp, distinguish pathology from normal, call for the proper consults and tests, as well as manage any identified rheumatic diseases, Dr. Philip J. Kahn said at a meeting sponsored by New York University.

By the time the rheumatologist sees a child presenting with a limp, the child may have already seen a pediatrician, emergency physician, and even an orthopedist.

Dr. Kahn, a pediatric rheumatologist at New York University Langone Medical Center, said he is concerned when a limp is associated, with fever, rash, weakness, joint swelling, and bearing weight. "If the child has fever and severe musculoskeletal pain, even with a normal platelet count, you should think of malignancy."

One of the first questions to ask is "Does it hurt?" A child with an antalgic gait (a gait that has adapted to counter or avoid pain) may refuse to bear weight. In this case, inquire whether the child has walked into the office or hospital or had to be carried. Nonpainful limp is usually insidious in onset, Dr. Kahn said, and may be suggestive of a rheumatic condition, weakness, stiffness, or deformity. Question the child as well as the parent, even though young patients may not be able to verbalize pain, and older children may deny it.

Other important clues about the limp are the time of onset; association with any known event, injury, or time of day; duration of pain (constant pain is suggestive of infection or malignancy); and location of pain (focal or diffuse, bone or joint). The physician should inquire about fever, anorexia, weight loss, or night sweats, which should raise suspicion of malignancy, infection, or rheumatologic problems. If fever is present, determine whether it is continuous, nocturnal, or quotidian (appearing daily, often at the same time). Delayed motor development or regression of achieved milestones, such as when a child who has walked independently suddenly asks to be carried around, may suggest neurologic or rheumatic disease. While a child may deny joint stiffness, a parent may notice the child cannot move easily in the morning or after long car rides or sitting in a classroom (Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 2009;23:625-42). Age is also an important consideration when evaluating the child with a limp.

Because observation is key during the physical exam, Dr. Kahn said to allow time to watch the child move around freely, looking for aberrations in gait. The child should be unclothed, barefoot, and observed during motion and at rest. While palpating the legs, be alert to areas of tenderness, suggestive of contusion, fracture, malignancy, or infection. Joints should be inspected for effusion, warmth, and tenderness, keeping in mind the possibility of referred pain from the hip or back, and range of motion should be assessed. He noted that the Childhood Myositis Assessment Scale (CMAS) can be helpful for assessing weakness (Arthritis Care Res. 2011;63 [Suppl. 11]:S118-57).

"Laboratory and radiographic evaluation will depend on what is discovered from the history and physical," Dr. Kahn said. Initial work-up may include complete/full blood count with differential, routine serum chemistries (including creatinine and liver and muscle enzymes), acute phase reactants (erythrocyte sedimentation rate [ESR] and C-reactive protein), and urinalysis. Testing synovial fluid for white blood cells is appropriate if septic arthritis is suspected, although the test is not highly sensitive or specific. "Elevated ESR in the presence of a normal or low platelet count in a child with musculoskeletal pain, especially if the child is febrile, is concerning for malignancy," he said. Dr. Kahn is somewhat reluctant to order antinuclear antibody testing unless there is a compelling reason because he says parents often panic upon hearing that.

The American College of Radiology in 2012 issued Appropriateness Criteria for evaluating limping children aged 0 to 5 years and selecting an imaging study (J. Am. Coll. Radiol. 2012;9:545-53). The criteria are categorized according to three variants: trauma; no trauma and no sign of infection; or possible presence of infection. With possible infection, imaging protocols are described for patients with localized pain to the hip, localized pain to the nonhip and lower extremity, and nonlocalized pain. Each imaging modality is given an appropriateness rating and an assessment of the relative radiation level. In brief, the criteria suggest that localized radiographs or tibial radiographs are appropriate following trauma. With an atraumatic and noninfectious history, hip ultrasound may be the initial study of choice, followed by radiography if the ultrasound is negative. Ultrasound of the hip allows a quick and accurate diagnosis of joint effusion, and aspiration can differentiate septic arthritis – an emergency situation – from transient synovitis. When long-term infection is suspected, MRI is the study of choice to demonstrate osteomyelitis or soft-tissue abscess.

Dr. Kahn presented a series of case studies, illustrating some key differentiating features that can help make the diagnosis:

• Case 1: A 2.5-year-old girl is carried into the emergency department (ED) after limping for 2 days. She began limping after coming home from the playground. She has no fever, rash, or constitutional features, and appears happy and smiling. Her hips, knees, ankles, and feet are not swollen, warm, or tender. There is tenderness at a point along her right tibia. The diagnosis is toddler’s fracture.

• Case 2: A 2.5-year-old girl is carried into the ED after limping for 2 days. There is no history of trauma, but the pain has become so severe that it awakens her at night. She refuses to walk, has constant pain not controlled by NSAIDS, and is cranky, febrile, tachycardic, and appears sick. She holds her right hip in a FABER (flexion, abduction, and external rotation) position. Her labs are C-reactive protein of 100 mg/L and a white blood cell of 30,000. The diagnosis is septic arthritis, with immediate referral to an orthopedist.

• Case 3: A 2.5-year-old girl walks into the ED after limping for 3 months. She denies having any pain, and her mother says she is lazy. She no longer alternates her feet when ascending steps and has fallen once when descending the stairs. When you examine her, she shows edematous and purple eyelids and a rash over her knuckles, as well as proximal weakness. Her muscle enzymes are elevated. The diagnosis is juvenile dermatomyositis.

• Case 4: A 2.5-year-old girl walks into the ED after limping for 3 months. An active girl, she fell off a slide the previous day and developed a large effusion after scraping her knee. She is smiling and running around the ED. She has no fever, malaise, joint swelling, or nocturnal wakening, although her mother says her limp is worse in the morning but lessens after breakfast. Inflammatory markers are normal and rheumatoid factor is absent. The diagnosis is oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis.

• Case 5: A 2.5-year-old girl walks into the ED after complaining that her legs have bothered her for 3 months. At night, she complains of lower leg pain in both legs and awakes sometimes at night from the pain but seems fine in the morning. No erythema or swollen joints are seen. She has been taken three times to the ED over the last few weeks, but blood tests and x-rays are said to be normal. Fever, rash, or constitutional symptoms are absent. The diagnosis is growing pains.

Dr. Kahn reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

NEW YORK – A timely diagnosis of a child presenting with a limp is essential because of the wide variety of possible causes, including benign disease such as a mild injury, a chronic disabling disease such as juvenile idiopathic arthritis, or a life-threatening infection or malignancy. It may be up to the pediatric rheumatologist to discriminate among the possible causes of the limp, distinguish pathology from normal, call for the proper consults and tests, as well as manage any identified rheumatic diseases, Dr. Philip J. Kahn said at a meeting sponsored by New York University.

By the time the rheumatologist sees a child presenting with a limp, the child may have already seen a pediatrician, emergency physician, and even an orthopedist.

Dr. Kahn, a pediatric rheumatologist at New York University Langone Medical Center, said he is concerned when a limp is associated, with fever, rash, weakness, joint swelling, and bearing weight. "If the child has fever and severe musculoskeletal pain, even with a normal platelet count, you should think of malignancy."

One of the first questions to ask is "Does it hurt?" A child with an antalgic gait (a gait that has adapted to counter or avoid pain) may refuse to bear weight. In this case, inquire whether the child has walked into the office or hospital or had to be carried. Nonpainful limp is usually insidious in onset, Dr. Kahn said, and may be suggestive of a rheumatic condition, weakness, stiffness, or deformity. Question the child as well as the parent, even though young patients may not be able to verbalize pain, and older children may deny it.

Other important clues about the limp are the time of onset; association with any known event, injury, or time of day; duration of pain (constant pain is suggestive of infection or malignancy); and location of pain (focal or diffuse, bone or joint). The physician should inquire about fever, anorexia, weight loss, or night sweats, which should raise suspicion of malignancy, infection, or rheumatologic problems. If fever is present, determine whether it is continuous, nocturnal, or quotidian (appearing daily, often at the same time). Delayed motor development or regression of achieved milestones, such as when a child who has walked independently suddenly asks to be carried around, may suggest neurologic or rheumatic disease. While a child may deny joint stiffness, a parent may notice the child cannot move easily in the morning or after long car rides or sitting in a classroom (Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 2009;23:625-42). Age is also an important consideration when evaluating the child with a limp.

Because observation is key during the physical exam, Dr. Kahn said to allow time to watch the child move around freely, looking for aberrations in gait. The child should be unclothed, barefoot, and observed during motion and at rest. While palpating the legs, be alert to areas of tenderness, suggestive of contusion, fracture, malignancy, or infection. Joints should be inspected for effusion, warmth, and tenderness, keeping in mind the possibility of referred pain from the hip or back, and range of motion should be assessed. He noted that the Childhood Myositis Assessment Scale (CMAS) can be helpful for assessing weakness (Arthritis Care Res. 2011;63 [Suppl. 11]:S118-57).

"Laboratory and radiographic evaluation will depend on what is discovered from the history and physical," Dr. Kahn said. Initial work-up may include complete/full blood count with differential, routine serum chemistries (including creatinine and liver and muscle enzymes), acute phase reactants (erythrocyte sedimentation rate [ESR] and C-reactive protein), and urinalysis. Testing synovial fluid for white blood cells is appropriate if septic arthritis is suspected, although the test is not highly sensitive or specific. "Elevated ESR in the presence of a normal or low platelet count in a child with musculoskeletal pain, especially if the child is febrile, is concerning for malignancy," he said. Dr. Kahn is somewhat reluctant to order antinuclear antibody testing unless there is a compelling reason because he says parents often panic upon hearing that.

The American College of Radiology in 2012 issued Appropriateness Criteria for evaluating limping children aged 0 to 5 years and selecting an imaging study (J. Am. Coll. Radiol. 2012;9:545-53). The criteria are categorized according to three variants: trauma; no trauma and no sign of infection; or possible presence of infection. With possible infection, imaging protocols are described for patients with localized pain to the hip, localized pain to the nonhip and lower extremity, and nonlocalized pain. Each imaging modality is given an appropriateness rating and an assessment of the relative radiation level. In brief, the criteria suggest that localized radiographs or tibial radiographs are appropriate following trauma. With an atraumatic and noninfectious history, hip ultrasound may be the initial study of choice, followed by radiography if the ultrasound is negative. Ultrasound of the hip allows a quick and accurate diagnosis of joint effusion, and aspiration can differentiate septic arthritis – an emergency situation – from transient synovitis. When long-term infection is suspected, MRI is the study of choice to demonstrate osteomyelitis or soft-tissue abscess.

Dr. Kahn presented a series of case studies, illustrating some key differentiating features that can help make the diagnosis:

• Case 1: A 2.5-year-old girl is carried into the emergency department (ED) after limping for 2 days. She began limping after coming home from the playground. She has no fever, rash, or constitutional features, and appears happy and smiling. Her hips, knees, ankles, and feet are not swollen, warm, or tender. There is tenderness at a point along her right tibia. The diagnosis is toddler’s fracture.

• Case 2: A 2.5-year-old girl is carried into the ED after limping for 2 days. There is no history of trauma, but the pain has become so severe that it awakens her at night. She refuses to walk, has constant pain not controlled by NSAIDS, and is cranky, febrile, tachycardic, and appears sick. She holds her right hip in a FABER (flexion, abduction, and external rotation) position. Her labs are C-reactive protein of 100 mg/L and a white blood cell of 30,000. The diagnosis is septic arthritis, with immediate referral to an orthopedist.

• Case 3: A 2.5-year-old girl walks into the ED after limping for 3 months. She denies having any pain, and her mother says she is lazy. She no longer alternates her feet when ascending steps and has fallen once when descending the stairs. When you examine her, she shows edematous and purple eyelids and a rash over her knuckles, as well as proximal weakness. Her muscle enzymes are elevated. The diagnosis is juvenile dermatomyositis.

• Case 4: A 2.5-year-old girl walks into the ED after limping for 3 months. An active girl, she fell off a slide the previous day and developed a large effusion after scraping her knee. She is smiling and running around the ED. She has no fever, malaise, joint swelling, or nocturnal wakening, although her mother says her limp is worse in the morning but lessens after breakfast. Inflammatory markers are normal and rheumatoid factor is absent. The diagnosis is oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis.

• Case 5: A 2.5-year-old girl walks into the ED after complaining that her legs have bothered her for 3 months. At night, she complains of lower leg pain in both legs and awakes sometimes at night from the pain but seems fine in the morning. No erythema or swollen joints are seen. She has been taken three times to the ED over the last few weeks, but blood tests and x-rays are said to be normal. Fever, rash, or constitutional symptoms are absent. The diagnosis is growing pains.

Dr. Kahn reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

NEW YORK – A timely diagnosis of a child presenting with a limp is essential because of the wide variety of possible causes, including benign disease such as a mild injury, a chronic disabling disease such as juvenile idiopathic arthritis, or a life-threatening infection or malignancy. It may be up to the pediatric rheumatologist to discriminate among the possible causes of the limp, distinguish pathology from normal, call for the proper consults and tests, as well as manage any identified rheumatic diseases, Dr. Philip J. Kahn said at a meeting sponsored by New York University.

By the time the rheumatologist sees a child presenting with a limp, the child may have already seen a pediatrician, emergency physician, and even an orthopedist.

Dr. Kahn, a pediatric rheumatologist at New York University Langone Medical Center, said he is concerned when a limp is associated, with fever, rash, weakness, joint swelling, and bearing weight. "If the child has fever and severe musculoskeletal pain, even with a normal platelet count, you should think of malignancy."

One of the first questions to ask is "Does it hurt?" A child with an antalgic gait (a gait that has adapted to counter or avoid pain) may refuse to bear weight. In this case, inquire whether the child has walked into the office or hospital or had to be carried. Nonpainful limp is usually insidious in onset, Dr. Kahn said, and may be suggestive of a rheumatic condition, weakness, stiffness, or deformity. Question the child as well as the parent, even though young patients may not be able to verbalize pain, and older children may deny it.

Other important clues about the limp are the time of onset; association with any known event, injury, or time of day; duration of pain (constant pain is suggestive of infection or malignancy); and location of pain (focal or diffuse, bone or joint). The physician should inquire about fever, anorexia, weight loss, or night sweats, which should raise suspicion of malignancy, infection, or rheumatologic problems. If fever is present, determine whether it is continuous, nocturnal, or quotidian (appearing daily, often at the same time). Delayed motor development or regression of achieved milestones, such as when a child who has walked independently suddenly asks to be carried around, may suggest neurologic or rheumatic disease. While a child may deny joint stiffness, a parent may notice the child cannot move easily in the morning or after long car rides or sitting in a classroom (Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 2009;23:625-42). Age is also an important consideration when evaluating the child with a limp.

Because observation is key during the physical exam, Dr. Kahn said to allow time to watch the child move around freely, looking for aberrations in gait. The child should be unclothed, barefoot, and observed during motion and at rest. While palpating the legs, be alert to areas of tenderness, suggestive of contusion, fracture, malignancy, or infection. Joints should be inspected for effusion, warmth, and tenderness, keeping in mind the possibility of referred pain from the hip or back, and range of motion should be assessed. He noted that the Childhood Myositis Assessment Scale (CMAS) can be helpful for assessing weakness (Arthritis Care Res. 2011;63 [Suppl. 11]:S118-57).

"Laboratory and radiographic evaluation will depend on what is discovered from the history and physical," Dr. Kahn said. Initial work-up may include complete/full blood count with differential, routine serum chemistries (including creatinine and liver and muscle enzymes), acute phase reactants (erythrocyte sedimentation rate [ESR] and C-reactive protein), and urinalysis. Testing synovial fluid for white blood cells is appropriate if septic arthritis is suspected, although the test is not highly sensitive or specific. "Elevated ESR in the presence of a normal or low platelet count in a child with musculoskeletal pain, especially if the child is febrile, is concerning for malignancy," he said. Dr. Kahn is somewhat reluctant to order antinuclear antibody testing unless there is a compelling reason because he says parents often panic upon hearing that.

The American College of Radiology in 2012 issued Appropriateness Criteria for evaluating limping children aged 0 to 5 years and selecting an imaging study (J. Am. Coll. Radiol. 2012;9:545-53). The criteria are categorized according to three variants: trauma; no trauma and no sign of infection; or possible presence of infection. With possible infection, imaging protocols are described for patients with localized pain to the hip, localized pain to the nonhip and lower extremity, and nonlocalized pain. Each imaging modality is given an appropriateness rating and an assessment of the relative radiation level. In brief, the criteria suggest that localized radiographs or tibial radiographs are appropriate following trauma. With an atraumatic and noninfectious history, hip ultrasound may be the initial study of choice, followed by radiography if the ultrasound is negative. Ultrasound of the hip allows a quick and accurate diagnosis of joint effusion, and aspiration can differentiate septic arthritis – an emergency situation – from transient synovitis. When long-term infection is suspected, MRI is the study of choice to demonstrate osteomyelitis or soft-tissue abscess.

Dr. Kahn presented a series of case studies, illustrating some key differentiating features that can help make the diagnosis:

• Case 1: A 2.5-year-old girl is carried into the emergency department (ED) after limping for 2 days. She began limping after coming home from the playground. She has no fever, rash, or constitutional features, and appears happy and smiling. Her hips, knees, ankles, and feet are not swollen, warm, or tender. There is tenderness at a point along her right tibia. The diagnosis is toddler’s fracture.

• Case 2: A 2.5-year-old girl is carried into the ED after limping for 2 days. There is no history of trauma, but the pain has become so severe that it awakens her at night. She refuses to walk, has constant pain not controlled by NSAIDS, and is cranky, febrile, tachycardic, and appears sick. She holds her right hip in a FABER (flexion, abduction, and external rotation) position. Her labs are C-reactive protein of 100 mg/L and a white blood cell of 30,000. The diagnosis is septic arthritis, with immediate referral to an orthopedist.

• Case 3: A 2.5-year-old girl walks into the ED after limping for 3 months. She denies having any pain, and her mother says she is lazy. She no longer alternates her feet when ascending steps and has fallen once when descending the stairs. When you examine her, she shows edematous and purple eyelids and a rash over her knuckles, as well as proximal weakness. Her muscle enzymes are elevated. The diagnosis is juvenile dermatomyositis.

• Case 4: A 2.5-year-old girl walks into the ED after limping for 3 months. An active girl, she fell off a slide the previous day and developed a large effusion after scraping her knee. She is smiling and running around the ED. She has no fever, malaise, joint swelling, or nocturnal wakening, although her mother says her limp is worse in the morning but lessens after breakfast. Inflammatory markers are normal and rheumatoid factor is absent. The diagnosis is oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis.

• Case 5: A 2.5-year-old girl walks into the ED after complaining that her legs have bothered her for 3 months. At night, she complains of lower leg pain in both legs and awakes sometimes at night from the pain but seems fine in the morning. No erythema or swollen joints are seen. She has been taken three times to the ED over the last few weeks, but blood tests and x-rays are said to be normal. Fever, rash, or constitutional symptoms are absent. The diagnosis is growing pains.

Dr. Kahn reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE NYU ANNUAL PEDIATRIC RHEUMATOLOGY UPDATE

Mitral valve bioprosthetic shows 16+ years of durability

NEW YORK – After following more than 400 patients who underwent mitral valve replacement for almost 25 years, French investigators have found that the Carpentier-Edwards Perimount Pericardial prosthetic has an expected durability of more than 16 years, with a low incidence of valve-related complications. The findings were presented by Dr. Thierry Bourguignon as one of the Plenary "Top 10" abstracts at the 2013 Mitral Valve Conclave.

"This is a great study. This very-long-term data has been missing for the Carpentier-Edwards Perimount bioprosthetic," said session moderator Dr. David H. Adams of Mount Sinai Medical Center in New York.

In this prospective study, investigators followed 404 patients who underwent mitral valve replacement between August 1984 and March 2011; 46 of these patients eventually needed a second bioprosthesis. Patients were asked to complete yearly clinical questionnaires and undergo an echocardiographic study. Their mean age was 68 years, but the range was 22-89 years. Almost one-fifth of the group was aged 60 years or younger. The mean follow-up time was 7.2 years, although it ranged from 0 to 24.8 years. Ten patients were lost during follow-up, yielding almost a 98% completion rate. Fifty-seven percent were New York Heart Association (NYHA) class III or IV.

The operative mortality rate was 3.3%. A total of 188 patients had late death (5.8%/valve-year). Forty of the deaths were valve related, including 5 due to thromboembolism, 4 to hemorrhage, 4 to endocarditis, 4 to structural valve dysfunction (SVD), and 23 to sudden death. Valve-related survival was more than 60% at 20 years post surgery. Risk factors affecting late survival were age at implant (hazard ratio, 1.06; P less than .001) and preoperative NYHA class III or IV (HR, 1.86; P less than .001).

"Valve-related events, including endocarditis, thromboembolism, and bleeding, were rare," said Dr. Bourguignon, a cardiovascular surgeon at Trousseau Hospital in Chambray Les Tours, France. There were no cases of valve thrombosis.

Seventy-six patients had an SVD, which was defined by echocardiography as severe mitral regurgitation and/or having a mean gradient of more than 8 mm Hg, even if patients were asymptomatic. Of these, 63 were reoperated and 13 died before reoperation. Three-quarters of the valves failed due to calcification, while 20% had late leaflet tears and 4% had mixed problems.

For the entire group, it took an average of 16.6 years before an SVD occurred, although freedom from SVD differed according to age at surgery. Older patients fared better. After 16.6 years, 75% of those over age 70 were expected to be free from SVD, while the rates were lower for those between 60 and 70 years (52%) and those under age 60 (40%). Older patients were also less likely to need the valve removed due to SVD.

What should a surgeon tell a patient about the risk of needing another operation to replace a failing mitral valve bioprosthetic? Using competing risk analysis, the authors predict that, for example, a 60-year-old patient at time of surgery will have a 20% chance of requiring reoperation due to an SVD after 11.9 years.

"In our experience, the CE Perimount valve is a reliable choice for patients older than 60, depending on the accepted risk of reoperation," said Dr. Bourguignon. Addressing a question from the audience, Dr. Bourguignon suggested that although the 25-year data were not available as yet for aortic valve replacements, preliminary findings indicate aortic valve replacement with bioprosthetics lasts longer than mitral valve replacement. At his hospital, patients under age 60 generally receive mechanical valves.

The conclave was sponsored by the American Association for Thoracic Surgery.

Dr. Bourguignon has a financial relationship with Edwards Lifesciences.

NEW YORK – After following more than 400 patients who underwent mitral valve replacement for almost 25 years, French investigators have found that the Carpentier-Edwards Perimount Pericardial prosthetic has an expected durability of more than 16 years, with a low incidence of valve-related complications. The findings were presented by Dr. Thierry Bourguignon as one of the Plenary "Top 10" abstracts at the 2013 Mitral Valve Conclave.

"This is a great study. This very-long-term data has been missing for the Carpentier-Edwards Perimount bioprosthetic," said session moderator Dr. David H. Adams of Mount Sinai Medical Center in New York.

In this prospective study, investigators followed 404 patients who underwent mitral valve replacement between August 1984 and March 2011; 46 of these patients eventually needed a second bioprosthesis. Patients were asked to complete yearly clinical questionnaires and undergo an echocardiographic study. Their mean age was 68 years, but the range was 22-89 years. Almost one-fifth of the group was aged 60 years or younger. The mean follow-up time was 7.2 years, although it ranged from 0 to 24.8 years. Ten patients were lost during follow-up, yielding almost a 98% completion rate. Fifty-seven percent were New York Heart Association (NYHA) class III or IV.

The operative mortality rate was 3.3%. A total of 188 patients had late death (5.8%/valve-year). Forty of the deaths were valve related, including 5 due to thromboembolism, 4 to hemorrhage, 4 to endocarditis, 4 to structural valve dysfunction (SVD), and 23 to sudden death. Valve-related survival was more than 60% at 20 years post surgery. Risk factors affecting late survival were age at implant (hazard ratio, 1.06; P less than .001) and preoperative NYHA class III or IV (HR, 1.86; P less than .001).

"Valve-related events, including endocarditis, thromboembolism, and bleeding, were rare," said Dr. Bourguignon, a cardiovascular surgeon at Trousseau Hospital in Chambray Les Tours, France. There were no cases of valve thrombosis.

Seventy-six patients had an SVD, which was defined by echocardiography as severe mitral regurgitation and/or having a mean gradient of more than 8 mm Hg, even if patients were asymptomatic. Of these, 63 were reoperated and 13 died before reoperation. Three-quarters of the valves failed due to calcification, while 20% had late leaflet tears and 4% had mixed problems.

For the entire group, it took an average of 16.6 years before an SVD occurred, although freedom from SVD differed according to age at surgery. Older patients fared better. After 16.6 years, 75% of those over age 70 were expected to be free from SVD, while the rates were lower for those between 60 and 70 years (52%) and those under age 60 (40%). Older patients were also less likely to need the valve removed due to SVD.

What should a surgeon tell a patient about the risk of needing another operation to replace a failing mitral valve bioprosthetic? Using competing risk analysis, the authors predict that, for example, a 60-year-old patient at time of surgery will have a 20% chance of requiring reoperation due to an SVD after 11.9 years.

"In our experience, the CE Perimount valve is a reliable choice for patients older than 60, depending on the accepted risk of reoperation," said Dr. Bourguignon. Addressing a question from the audience, Dr. Bourguignon suggested that although the 25-year data were not available as yet for aortic valve replacements, preliminary findings indicate aortic valve replacement with bioprosthetics lasts longer than mitral valve replacement. At his hospital, patients under age 60 generally receive mechanical valves.

The conclave was sponsored by the American Association for Thoracic Surgery.

Dr. Bourguignon has a financial relationship with Edwards Lifesciences.

NEW YORK – After following more than 400 patients who underwent mitral valve replacement for almost 25 years, French investigators have found that the Carpentier-Edwards Perimount Pericardial prosthetic has an expected durability of more than 16 years, with a low incidence of valve-related complications. The findings were presented by Dr. Thierry Bourguignon as one of the Plenary "Top 10" abstracts at the 2013 Mitral Valve Conclave.

"This is a great study. This very-long-term data has been missing for the Carpentier-Edwards Perimount bioprosthetic," said session moderator Dr. David H. Adams of Mount Sinai Medical Center in New York.

In this prospective study, investigators followed 404 patients who underwent mitral valve replacement between August 1984 and March 2011; 46 of these patients eventually needed a second bioprosthesis. Patients were asked to complete yearly clinical questionnaires and undergo an echocardiographic study. Their mean age was 68 years, but the range was 22-89 years. Almost one-fifth of the group was aged 60 years or younger. The mean follow-up time was 7.2 years, although it ranged from 0 to 24.8 years. Ten patients were lost during follow-up, yielding almost a 98% completion rate. Fifty-seven percent were New York Heart Association (NYHA) class III or IV.

The operative mortality rate was 3.3%. A total of 188 patients had late death (5.8%/valve-year). Forty of the deaths were valve related, including 5 due to thromboembolism, 4 to hemorrhage, 4 to endocarditis, 4 to structural valve dysfunction (SVD), and 23 to sudden death. Valve-related survival was more than 60% at 20 years post surgery. Risk factors affecting late survival were age at implant (hazard ratio, 1.06; P less than .001) and preoperative NYHA class III or IV (HR, 1.86; P less than .001).

"Valve-related events, including endocarditis, thromboembolism, and bleeding, were rare," said Dr. Bourguignon, a cardiovascular surgeon at Trousseau Hospital in Chambray Les Tours, France. There were no cases of valve thrombosis.

Seventy-six patients had an SVD, which was defined by echocardiography as severe mitral regurgitation and/or having a mean gradient of more than 8 mm Hg, even if patients were asymptomatic. Of these, 63 were reoperated and 13 died before reoperation. Three-quarters of the valves failed due to calcification, while 20% had late leaflet tears and 4% had mixed problems.

For the entire group, it took an average of 16.6 years before an SVD occurred, although freedom from SVD differed according to age at surgery. Older patients fared better. After 16.6 years, 75% of those over age 70 were expected to be free from SVD, while the rates were lower for those between 60 and 70 years (52%) and those under age 60 (40%). Older patients were also less likely to need the valve removed due to SVD.

What should a surgeon tell a patient about the risk of needing another operation to replace a failing mitral valve bioprosthetic? Using competing risk analysis, the authors predict that, for example, a 60-year-old patient at time of surgery will have a 20% chance of requiring reoperation due to an SVD after 11.9 years.

"In our experience, the CE Perimount valve is a reliable choice for patients older than 60, depending on the accepted risk of reoperation," said Dr. Bourguignon. Addressing a question from the audience, Dr. Bourguignon suggested that although the 25-year data were not available as yet for aortic valve replacements, preliminary findings indicate aortic valve replacement with bioprosthetics lasts longer than mitral valve replacement. At his hospital, patients under age 60 generally receive mechanical valves.

The conclave was sponsored by the American Association for Thoracic Surgery.

Dr. Bourguignon has a financial relationship with Edwards Lifesciences.

AT THE 2013 MITRAL VALVE CONCLAVE

Major finding: The mean durability of the Carpentier-Edwards Perimount Pericardial prosthetic was 16.6 years before a structural valve dysfunction occurred.

Data source: Prospective study of 404 patients who underwent mitral valve replacement using the Perimount prosthetic.

Disclosures: Dr. Bourguignon has a financial relationship with Edwards Lifesciences.

IL-1-beta emerges as key molecule for autoinflammatory diseases

NEW YORK – Evidence has accumulated in recent years that IL-1-beta-mediated inflammation and a dysregulation of the innate immune system is common to many autoinflammatory disorders that involve bouts of seemingly unprovoked recurrent inflammation and no indication of malignancy or infection, according to Dr. Jonathan Samuels.

These findings have opened up new therapeutic targets for these disorders, and some recent clinical studies suggest that investigators are on the right track, said Dr. Samuels, a rheumatologist affiliated with the Center for Musculoskeletal Care at NYU Langone Medical Center, New York.

The term "autoinflammation" was coined in 1999 following the discovery of the genes responsible for Familial Mediterranean Fever (FMF), a disease characterized by recurrent episodes of fever and abdominal pain, along with pleurisy, arthritis, and other symptoms. Patients feel normal between bouts and are unresponsive to corticosteroids. Like other patients with autoinflammatory diseases, FMF patients show no evidence of autoantibodies or antigen-specific T-cell reactivity, suggesting instead disordered regulation of the innate immune system, Dr. Samuels said at a meeting sponsored by New York University.

IL-1 has been identified as one of the most potent proinflammatory cytokines of the innate immune system, and is being recognized as a likely therapeutic target. "Many molecular cascades from various autoinflammatory diseases converge at IL-1, with oversecretion (as in the case of neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disease or NOMID) or uninhibited signaling (as in the case of deficiency of the interleukin-1-receptor antagonist or DIRA)," Dr. Samuels said.

For example, while colchicine has been shown to prevent acute attacks of FMF by 75% and decrease symptoms in 95%, there are no proven alternative therapies for patients with FMF who are resistant or intolerant to colchicine. Dr. Samuels was a coinvestigator of a recent randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled trial in which 14 patients with FMF who were colchicine resistant or intolerant were treated with the IL-1 antagonist rilonacept (2.2 mg/kg, maximum 160 mg) given by weekly subcutaneous injection for two 3-month courses. Rilonacept resulted in a significant reduction in the number of attacks per month (0.77 vs. 2.00, P = .027) and there were more treatment courses without attacks with rilonacept, compared with placebo. Rilonacept did not affect the duration of attacks (Ann. Intern. Med. 2012;157:533-41).

The cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes, commonly known as CAPS, are a group of autosomal dominant autoinflammatory diseases that have been linked to mutations in the same gene. All three cryopyrinopathies have an early onset and present with urticarial rash and fever, although they span a spectrum of severity, according to Dr. Samuels. The mildest form is familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome (FCAS), which involves episodes generally lasting less than 24 hours, and is accompanied by headache and polyarthralgia. Muckle-Wells syndrome lasts 24-48 hours, and may cause deafness, optic disk edema, oligoarthritis, and polyarthralgia, as well as abdominal pain. Patients with NOMID are the most severely affected, with almost-continuous episodes, chronic meningitis, mental retardation, deafness, blindness, epiphyseal/patellar overgrowth, and intermittent chronic arthritis.

All three CAPS syndromes have been shown to respond to anti-IL-1 agents, according to Dr. Samuels. For example, in 2012, researchers from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases found in an open-label cohort study of 26 patients with NOMID that the IL-1 inhibitor anakinra yielded long-term improvements in measures such as global scores of disease activity, pain, CNS inflammation, and hearing for up to 5 years as long as escalating doses were used (Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:2375-86).

Treatment with anakinra also has been beneficial for neonates with DIRA, which involves an autosomal recessive mutation on chromosome 2q that leads to uncontrolled IL-1 binding and causes crusting, erythema, pustulosis, and osteolytic lesions.

"This is a very complex group of disorders," Dr. Samuels said. Diagnosis should take into account ethnicity, inheritance pattern, cytokines, attack duration, treatment response, age of onset, triggers, and amyloid frequency. He referred audience members to a helpful diagnostic algorithm (Cleveland Clinic J. Med. 2012;79:569-81).

Dr. Samuels reported no relevant financial disclosures.

NEW YORK – Evidence has accumulated in recent years that IL-1-beta-mediated inflammation and a dysregulation of the innate immune system is common to many autoinflammatory disorders that involve bouts of seemingly unprovoked recurrent inflammation and no indication of malignancy or infection, according to Dr. Jonathan Samuels.

These findings have opened up new therapeutic targets for these disorders, and some recent clinical studies suggest that investigators are on the right track, said Dr. Samuels, a rheumatologist affiliated with the Center for Musculoskeletal Care at NYU Langone Medical Center, New York.

The term "autoinflammation" was coined in 1999 following the discovery of the genes responsible for Familial Mediterranean Fever (FMF), a disease characterized by recurrent episodes of fever and abdominal pain, along with pleurisy, arthritis, and other symptoms. Patients feel normal between bouts and are unresponsive to corticosteroids. Like other patients with autoinflammatory diseases, FMF patients show no evidence of autoantibodies or antigen-specific T-cell reactivity, suggesting instead disordered regulation of the innate immune system, Dr. Samuels said at a meeting sponsored by New York University.

IL-1 has been identified as one of the most potent proinflammatory cytokines of the innate immune system, and is being recognized as a likely therapeutic target. "Many molecular cascades from various autoinflammatory diseases converge at IL-1, with oversecretion (as in the case of neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disease or NOMID) or uninhibited signaling (as in the case of deficiency of the interleukin-1-receptor antagonist or DIRA)," Dr. Samuels said.

For example, while colchicine has been shown to prevent acute attacks of FMF by 75% and decrease symptoms in 95%, there are no proven alternative therapies for patients with FMF who are resistant or intolerant to colchicine. Dr. Samuels was a coinvestigator of a recent randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled trial in which 14 patients with FMF who were colchicine resistant or intolerant were treated with the IL-1 antagonist rilonacept (2.2 mg/kg, maximum 160 mg) given by weekly subcutaneous injection for two 3-month courses. Rilonacept resulted in a significant reduction in the number of attacks per month (0.77 vs. 2.00, P = .027) and there were more treatment courses without attacks with rilonacept, compared with placebo. Rilonacept did not affect the duration of attacks (Ann. Intern. Med. 2012;157:533-41).

The cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes, commonly known as CAPS, are a group of autosomal dominant autoinflammatory diseases that have been linked to mutations in the same gene. All three cryopyrinopathies have an early onset and present with urticarial rash and fever, although they span a spectrum of severity, according to Dr. Samuels. The mildest form is familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome (FCAS), which involves episodes generally lasting less than 24 hours, and is accompanied by headache and polyarthralgia. Muckle-Wells syndrome lasts 24-48 hours, and may cause deafness, optic disk edema, oligoarthritis, and polyarthralgia, as well as abdominal pain. Patients with NOMID are the most severely affected, with almost-continuous episodes, chronic meningitis, mental retardation, deafness, blindness, epiphyseal/patellar overgrowth, and intermittent chronic arthritis.

All three CAPS syndromes have been shown to respond to anti-IL-1 agents, according to Dr. Samuels. For example, in 2012, researchers from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases found in an open-label cohort study of 26 patients with NOMID that the IL-1 inhibitor anakinra yielded long-term improvements in measures such as global scores of disease activity, pain, CNS inflammation, and hearing for up to 5 years as long as escalating doses were used (Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:2375-86).

Treatment with anakinra also has been beneficial for neonates with DIRA, which involves an autosomal recessive mutation on chromosome 2q that leads to uncontrolled IL-1 binding and causes crusting, erythema, pustulosis, and osteolytic lesions.

"This is a very complex group of disorders," Dr. Samuels said. Diagnosis should take into account ethnicity, inheritance pattern, cytokines, attack duration, treatment response, age of onset, triggers, and amyloid frequency. He referred audience members to a helpful diagnostic algorithm (Cleveland Clinic J. Med. 2012;79:569-81).

Dr. Samuels reported no relevant financial disclosures.

NEW YORK – Evidence has accumulated in recent years that IL-1-beta-mediated inflammation and a dysregulation of the innate immune system is common to many autoinflammatory disorders that involve bouts of seemingly unprovoked recurrent inflammation and no indication of malignancy or infection, according to Dr. Jonathan Samuels.

These findings have opened up new therapeutic targets for these disorders, and some recent clinical studies suggest that investigators are on the right track, said Dr. Samuels, a rheumatologist affiliated with the Center for Musculoskeletal Care at NYU Langone Medical Center, New York.

The term "autoinflammation" was coined in 1999 following the discovery of the genes responsible for Familial Mediterranean Fever (FMF), a disease characterized by recurrent episodes of fever and abdominal pain, along with pleurisy, arthritis, and other symptoms. Patients feel normal between bouts and are unresponsive to corticosteroids. Like other patients with autoinflammatory diseases, FMF patients show no evidence of autoantibodies or antigen-specific T-cell reactivity, suggesting instead disordered regulation of the innate immune system, Dr. Samuels said at a meeting sponsored by New York University.

IL-1 has been identified as one of the most potent proinflammatory cytokines of the innate immune system, and is being recognized as a likely therapeutic target. "Many molecular cascades from various autoinflammatory diseases converge at IL-1, with oversecretion (as in the case of neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disease or NOMID) or uninhibited signaling (as in the case of deficiency of the interleukin-1-receptor antagonist or DIRA)," Dr. Samuels said.

For example, while colchicine has been shown to prevent acute attacks of FMF by 75% and decrease symptoms in 95%, there are no proven alternative therapies for patients with FMF who are resistant or intolerant to colchicine. Dr. Samuels was a coinvestigator of a recent randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled trial in which 14 patients with FMF who were colchicine resistant or intolerant were treated with the IL-1 antagonist rilonacept (2.2 mg/kg, maximum 160 mg) given by weekly subcutaneous injection for two 3-month courses. Rilonacept resulted in a significant reduction in the number of attacks per month (0.77 vs. 2.00, P = .027) and there were more treatment courses without attacks with rilonacept, compared with placebo. Rilonacept did not affect the duration of attacks (Ann. Intern. Med. 2012;157:533-41).

The cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes, commonly known as CAPS, are a group of autosomal dominant autoinflammatory diseases that have been linked to mutations in the same gene. All three cryopyrinopathies have an early onset and present with urticarial rash and fever, although they span a spectrum of severity, according to Dr. Samuels. The mildest form is familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome (FCAS), which involves episodes generally lasting less than 24 hours, and is accompanied by headache and polyarthralgia. Muckle-Wells syndrome lasts 24-48 hours, and may cause deafness, optic disk edema, oligoarthritis, and polyarthralgia, as well as abdominal pain. Patients with NOMID are the most severely affected, with almost-continuous episodes, chronic meningitis, mental retardation, deafness, blindness, epiphyseal/patellar overgrowth, and intermittent chronic arthritis.

All three CAPS syndromes have been shown to respond to anti-IL-1 agents, according to Dr. Samuels. For example, in 2012, researchers from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases found in an open-label cohort study of 26 patients with NOMID that the IL-1 inhibitor anakinra yielded long-term improvements in measures such as global scores of disease activity, pain, CNS inflammation, and hearing for up to 5 years as long as escalating doses were used (Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:2375-86).

Treatment with anakinra also has been beneficial for neonates with DIRA, which involves an autosomal recessive mutation on chromosome 2q that leads to uncontrolled IL-1 binding and causes crusting, erythema, pustulosis, and osteolytic lesions.

"This is a very complex group of disorders," Dr. Samuels said. Diagnosis should take into account ethnicity, inheritance pattern, cytokines, attack duration, treatment response, age of onset, triggers, and amyloid frequency. He referred audience members to a helpful diagnostic algorithm (Cleveland Clinic J. Med. 2012;79:569-81).

Dr. Samuels reported no relevant financial disclosures.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE NYU SEMINAR IN ADVANCED RHEUMATOLOGY

Treat JIA uveitis early, aggressively to avoid vision loss

NEW YORK – Tailoring the frequency of vision screening for children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis is an important step to getting uveitis symptoms treated effectively before permanent morbidity occurs, according to Dr. Sanjay R. Kedhar.

"We know that children with JIA [juvenile idiopathic arthritis] who have chronic inflammation of the eye have a threefold increase in the risk of blindness. We also know that immunosuppressive therapy reduces the risk of blindness by 60%. I believe that physicians should feel the time pressure to identify uveitis in children and treat them aggressively to preserve vision and reduce morbidity," said Dr. Kedhar, an ophthalmologist at The New York (N.Y.) Eye and Ear Infirmary and associate professor of ophthalmology at New York Medical College in Valhalla, N.Y. Uveitis-associated morbidity includes cataracts, glaucoma, band keratopathy, phthisis bulbi, and vision loss.

Uveitis is the third most common cause of blindness in children, and JIA-associated uveitis is the most common cause of uveitis in children. About one in four children with JIA uveitis presents with blindness. Early detection, awareness of risk factors, and prompt and effective treatment can slow or prevent vision loss in children with JIA-associated uveitis, he said at the meeting, sponsored by New York University.

Uveitis associated with JIA most commonly affects the anterior portions of the eye, between the cornea and iris. Symptoms of anterior uveitis include blurred vision, pain, redness, photophobia, floaters, flashing lights, and distorted vision (metamorphopsia). The problem is that symptoms may be absent in children or, alternatively, children may not be able to verbalize what they see. "By the time symptoms are detected in school screening, it may be too late," Dr. Kedhar said.

That is why it is important to make sure children with JIA have regular ophthalmologic examinations as recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics (Pediatrics 2006;117:1843-5). Screening frequency depends upon the presence of risk factors, such as type of arthritis (oligoarticular), age at onset, antinuclear antibody (ANA) seropositivity, and RF seronegativity. Children with JIA who have oligoarticular and polyarticular joint involvement and who are ANA positive and RF negative generally are at highest risk of developing uveitis, with 33%-70% affected.

"These are the kids we have to worry about the most," Dr. Kedhar said. If the joint symptoms appear before 7 years of age, the children should be seen every 3-4 months. Those children who have oligoarticular and polyarticular joint involvement beginning before age 7 but are ANA negative are considered at intermediate risk and should be seen every 6 months. Those who have a systemic onset of disease require screening every 12 months, reflecting the low risk of uveitis in this group.