User login

Genitourinary syndrome of menopause: Current and emerging therapies

Genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) is the new terminology to describe symptoms occurring secondary to vulvovaginal atrophy.1 The recent change in terminology originated with a consensus panel comprising the board of directors of the International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health (ISSWSH) and the board of trustees of the North American Menopause Society (NAMS). At a terminology consensus conference in May 2013, these groups determined that the term GSM is medically more accurate and all encompassing than vulvovaginal atrophy. It is also more publicly acceptable.

The symptoms of GSM derive from the hypoestrogenic state most commonly associated with menopause and its effects on the genitourinary tract.2 Vaginal symptoms associated with GSM include vaginal or vulvar dryness, discharge, itching, and dyspareunia.3 Histologically, a loss of superficial epithelial cells in the genitourinary tract leads to thinning of the tissue. There is then a loss of vaginal rugae and elasticity, leading to narrowing and shortening of the vagina.

In addition, the vaginal epithelium becomes much more fragile, which can lead to tears, bleeding, and fissures. There is also a loss of the subcutaneous fat of the labia majora, a change that can result in narrowing of the introitus, fusion of the labia majora, and shrinkage of the clitoral prepuce and urethra. The vaginal pH level becomes more alkaline, which may alter vaginal flora and increase the risk of urogenital infections—specifically, urinary tract infection (UTI). Vaginal secretions, largely transudate, from the vaginal vasculature also decrease over time. These changes lead to significant dyspareunia and impairment of sexual function.

In this article, we survey the therapies available for GSM, focusing first on proven treatments such as local estrogen administration and use of ospemifene (Osphena), and then describing an emerging treatment involving the use of fractional CO2 laser.

How prevalent is GSM?

Approximately half of all postmenopausal women in the United States report atrophy-related symptoms and a significant negative effect on quality of life.4–6 Few women with these symptoms seek medical attention.

The Vaginal Health: Insights, Views, and Attitudes (VIVA) survey found that 80% of women with genital atrophy considered its impact on their lives to be negative, 75% reported negative consequences in their sexual life, 68% reported that it made them feel less sexual, 33% reported negative effects on their marriage or relationship, and 26% reported a negative impact on their self-esteem.7

Another review of the impact of this condition by Nappi and Palacios estimated that, by the year 2025, there will be 1.1 billion women worldwide older than age 50 with specific needs related to GSM.8 Nappi and Palacios cite 4 recent surveys that suggest that health care providers need to be more proactive in helping patients disclose their symptoms. The same can be said of other symptoms of the urinary tract, such as urinary frequency, urgency, and incontinence, as well as pelvic floor relaxation.

A recently published international survey on vaginal atrophy not only depicts the extremely high prevalence of the condition but also describes fairly significant differences in attitudes toward symptoms between countries in Europe and North America.9 Overall, 77% of respondents, who included more than 4,000 menopausal women, believed that women were uncomfortable discussing symptoms of vaginal atrophy.9

Pastore and colleagues, using data from the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI), found the most prevalent urogenital symptoms to be vaginal dryness (27%), vaginal irritation or itching (18.6%), vaginal discharge (11.1%), and dysuria (5.2%).4 Unlike vasomotor symptoms of menopause, which tend to decrease over time, GSM does not spontaneously remit and commonly recurs when hormone therapy—the dominant treatment—is withdrawn.

What can we offer our patients?

Vaginal estrogen

The most common therapy used to manage GSM is estrogen. Most recommendations state that if the primary menopausal symptoms are related to vaginal atrophy, then local estrogen administration should be the primary mode of therapy. The Society of Gynecologic Surgeons Systematic Review Group recently concluded that all commercially available vaginal estrogens effectively can relieve common vulvovaginal atrophy−related symptoms and have additional utility in women with urinary urgency, frequency, stress incontinence, urge incontinence, and recurrent UTIs.10 Although their meta-analysis clearly demonstrated that estrogen therapy improves the symptoms of GSM, investigators acknowledged that a clearer understanding is needed of the exact risk to the endometrium with sustained use of vaginal estrogen, as well as a more precise assessment of changes in serum estradiol levels.10

A recent Cochrane review concluded that all forms of local estrogen appear to be equally effective for symptoms of vaginal atrophy.11 One trial cited in the review found significant adverse effects following administration of cream, compared with tablets, causing uterine bleeding, breast pain, and perineal pain.11

Another trial cited in the Cochrane review found significant endometrial overstimulation following use of cream, compared with the vaginal ring. As a treatment of choice, women appeared to favor the estradiol-releasing vaginal ring for ease of use, comfort of product, and overall satisfaction.11

After the release of the WHI data, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) released a “black box” warning on postmenopausal hormone use in women, which has significantly reduced the use of both local and systemic estrogen in eligible women. NAMS has recommended that the FDA revisit this warning, calling specifically for an independent commission to scrutinize every major WHI paper to determine whether the data justify the conclusions drawn.12

Most data back local estrogen as treatment for GSM

In 2013, the North American Menopause Society (NAMS) issued a position statement noting that the choice of therapy for genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) depends on the severity of symptoms, the efficacy and safety of therapy for the individual patient, and patient preference.1

To date, estrogen therapy is the most effective treatment for moderate to severe GSM, although a direct comparison of estrogen and ospemifene is lacking. Nonhormonal therapies available without a prescription provide sufficient relief for most women with mild symptoms. When low-dose estrogen is administered locally, a progestin is not indicated for women without a uterus—and generally is not indicated for women with an intact uterus. However, endometrial safety has not been studied in clinical trials beyond 1 year. Data are insufficient to confirm the safety of local estrogen in women with breast cancer.

Future research on the use of the fractional CO2 laser, which seems to be a promising emerging therapy, may provide clinicians with another option to treat the common and distressing problem of GSM.

Reference

1. Management of symptomatic vulvovaginal atrophy: 2013 position statement of the North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2013;20(9):888–902.

Ospemifene

This estrogen agonist and antagonist selectively stimulates or inhibits estrogen receptors of different target tissues, making it a selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM). In a study involving 826 postmenopausal women randomly allocated to 30 mg or 60 mg of ospemifene, the 60-mg dose proved to be more effective for improving vulvovaginal atrophy.13 Long-term safety studies revealed that ospemifene 60 mg given daily for 52 weeks was well tolerated and not associated with any endometrial- or breast-related safety issues.13,14 Common adverse effects of ospemifene reported during clinical trials included hot flashes, vaginal discharge, muscle spasms, general discharge, and excessive sweating.12

Vaginal lubricants and moisturizers

Nonestrogen water- or silicone-based vaginal lubricants and moisturizers may alleviate vaginal symptoms related to menopause. These products may be particularly helpful for women who do not wish to use hormone therapies.

Vaginal lubricants are intended to relieve friction and dyspareunia related to vaginal dryness during intercourse, with the ultimate goal of trapping moisture and providing long-term relief of vaginal dryness.

Although data are limited on the efficacy of these products, prospective studies have demonstrated that vaginal moisturizers improve vaginal dryness, pH balance, and elasticity and reduce vaginal itching, irritation, and dyspareunia.

Data are insufficient to support the use of herbal remedies or soy products for the treatment of vaginal symptoms.

An emerging therapy: fractional CO2 laser

In September 2014, the FDA cleared for use the SmartXide2 CO2 laser system (DEKA Medical) for “incision, excision, vaporization and coagulation of body soft tissues” in medical specialties that include gynecology and genitourinary surgery.15 The system, also marketed by Cynosure as the MonaLisa Touch treatment, was not approved specifically for treatment of GSM—and it is important to note that the path to device clearance by the FDA is much less cumbersome than the route to drug approval. As NAMS notes in an article about the fractional CO2 laser, “Device clearance does not require the large, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trials with established efficacy and safety endpoints required for the approval of new drugs.”16 Nevertheless, this laser system appears to be poised to become a new treatment for the symptoms of GSM.

This laser supplies energy with a specific pulse to the vaginal wall to rapidly and superficially ablate the epithelial component of atrophic mucosa, which is characterized by low water content. Ablation is followed by tissue coagulation, stimulated by laser energy penetrating into deeper tissues, triggering the synthesis of new collagen and other components of the ground substance of the matrix.

The supraphysiologic level of heat generated by the CO2 laser induces a rapid and transient heat-shock response that temporarily alters cellular metabolism and activates a small family of proteins referred to as the “heat shock proteins” (HSPs). HSP 70, which is overexpressed following laser treatment, stimulates transforming growthfactor‑beta, triggering an inflammatory response that stimulates fibroblasts, which produce new collagen and extracellular matrix.

The laser has emissions characteristics aligned for the transfer of the energy load to the mucosa while avoiding excessive localized damage. This aspect of its design allows for restoration of the permeability of the connective tissue, enabling the physiologic transfer of various nutrients from capillaries to tissues. When there is a loss of estrogen, as during menopause, vaginal atrophy develops, with the epithelium deteriorating and thinning. The fractional CO2 laser therapy improves the state of the epithelium by restoring epithelial cell trophism.

The vaginal dryness that occurs with atrophy is due to poor blood flow, as well as reduced activity of the fibroblasts in the deeper tissue. The increased lubrication that occurs after treatment is usually a vaginal transudate from blood outflow through the capillaries that supply blood to the vaginal epithelium. The high presence of water molecules increases permeability, allowing easier transport of metabolites and nutrients from capillaries to tissue, as well as the drainage of waste products from tissues to blood and lymph vessels.

With atrophy, the glycogen in the epithelial cells decreases. Because lactobacilli need glycogen to thrive and are responsible for maintaining the acidity of the vagina, the pH level increases. With the restoration of trophism, glycogen levels increase, furthering colonization of vaginal lactobacilli as well as vaginal acidity, reducing the pH level. This effect also may protect against the development of recurrent UTIs.

A look at the data

To date, more than 2,000 women in Italy and more than 10,000 women worldwide with GSM have been treated with fractional CO2 laser therapy, and several peer-reviewed publications have documented its efficacy and safety.17–21

In published studies, however, the populations have been small and the investigations have been mostly short term (12 weeks).17–21

A pilot study reported that a treatment cycle of 3 laser applications significantly improved the most bothersome symptoms of vulvovaginal atrophy and improved scores of vaginal health at 12 weeks’ follow-up in 50 women who had not responded to or were unsatisfied with local estrogen therapy.17 This investigation was followed by 2 additional studies involving another 92 women that specifically addressed the impact of fractional CO2 laser therapy on dyspareunia and female sexual function.19,20 Both studies showed statistically significant improvement in dyspareunia as well as Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) scores. All women in these studies were treated in an office setting with no pretreatment anesthesia. No adverse events were reported.

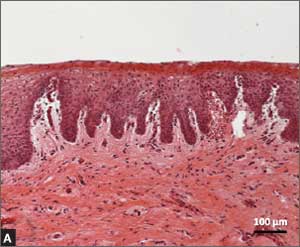

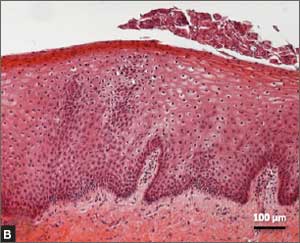

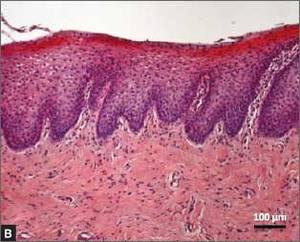

Recently published histology data highlight significant changes 1 month after fractional CO2 laser treatment that included a much thicker epithelium with wide columns of large epithelial cells rich in glycogen.21 Also noted was a significant reorganization of connective tissue, both in the lamina propria and the core of the papillae (FIGURES 1 and 2).

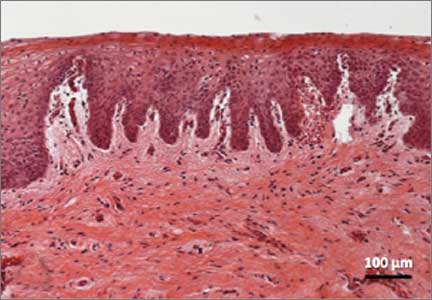

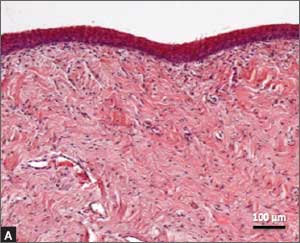

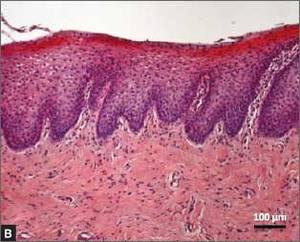

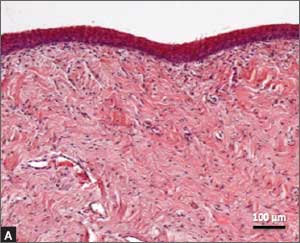

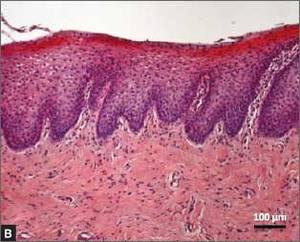

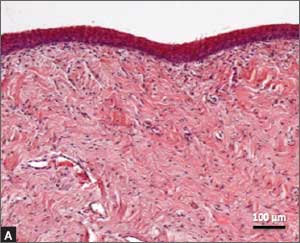

| FIGURE 1: Early-stage vaginal atrophy   |

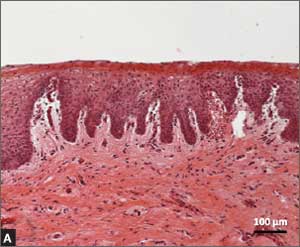

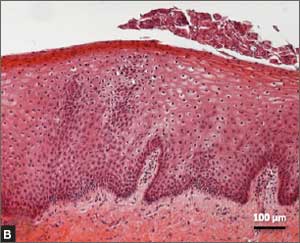

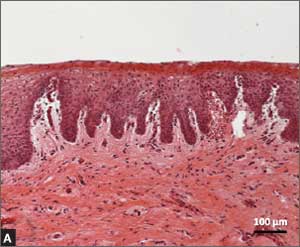

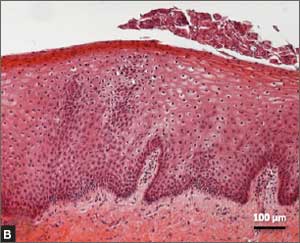

FIGURE 2: Atrophic vaginitis   This histologic preparation of vaginal mucosa sections shows untreated atrophic vaginitis (A) and the same mucosa 1 month after treatment with fractional CO2 laser therapy (B). Reprinted with permission from DEKA M.E.L.A. Srl (Calenzano, Italy) and Professor A. Calligaro, University of Pavia, Italy. |

Caveats

No International Classification of Diseases (ICD) 9 or 10 code has been assigned to the procedure to date, and the cost to the patient ranges from $600 to $1,000 per procedure.16

NAMS position. A review of the technology by NAMS noted the need for large, long-term, randomized, sham-controlled studies “to further evaluate the safety and efficacy of this procedure.”16

NAMS also notes that “lasers have become a very costly option for the treatment of symptomatic [GSM], without a single trial comparing active laser treatment to sham laser treatment and no information on long-term safety. In all published trials to date, only several hundred women have been studied and most studies are only 12 weeks in duration.”16

Not a new concept. The concept of treating skin with a microablative CO2 laser is not new. This laser has been safely used on the skin of the face, neck, and chest to produce new collagen and elastin fibers with remodeling of tissue.22,23

Preliminary data on the use of a fractionated CO2 microablative laser to treat symptoms associated with GSM suggest that the therapy is feasible, effective, and safe in the short term. If these findings are confirmed by larger, longer-term, well-controlled studies, this laser will be an additional safe and effective treatment for this very common and distressing disorder.

Two authors (Mickey Karram, MD, and Eric Sokol, MD) are performing a study of the fractional CO2 laser for treatment of genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) in the United States. To date, 30 women with GSM have been treated with 3 cycles and followed for 3 months. Preliminary data show significant improvement in all symptoms, with all patients treated in an office setting with no pretreatment or posttreatment analgesia required.

The laser settings for treatment included a power of 30 W, a dwell time of 1,000 µs, spacing between 2 adjacent treated spots of 1,000 µs, and a stack parameter for pulses from 1 to 3.

Laser energy is delivered through a specially designed scanner and a vaginal probe. The probe is slowly inserted to the top of the vaginal canal and then gradually withdrawn, treating the vaginal epithelium at increments of almost 1 cm (FIGURE 3). The laser beam projects onto a 45° mirror placed at the tip of the probe, which reflects it at 90°, thereby ensuring that only the vaginal wall is treated, and not the uterine cervix.

A treatment cycle included 3 laser treatments at 6-week intervals. Each treatment lasted 3 to 5 minutes. Initial improvement was noted in most patients, including increased lubrication within 1 week after the first treatment, with further improvement after each session. To date, the positive results have persisted, and all women in the trial now have been followed for 3 months—all have noted improvement in symptoms. They will continue periodic assessment, with a final subjective and objective evaluation 1 year after their first treatment.

Bottom line

Although preliminary studies of the fractional CO2 laser as a treatment for GSM are promising, local estrogen is backed by a large body of reliable data. Ospemifene also has FDA approval for treatment of this disorder.

For women who cannot or will not use a hormone-based therapy, vaginal lubricants and moisturizer may offer at least some relief.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Portman DJ, Gass ML. Genitourinary syndrome of menopause: new terminology for vulvovaginal atrophy from the International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health and the North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2014;21(10):1–6.

- Calleja-Agius J, Brincat MP. Urogenital atrophy. Climacteric. 2009;12(4):279–285.

- Mehta A, Bachmann G. Vulvovaginal complaints. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2008;51(3):549–555.

- Pastore LM, Carter RA, Hulka BS, Wells E. Self-reported urogenital symptoms in postmenopausal women: Women’s Health Initiative. Maturitas. 2004;49(4):292–303.

- Santoro N, Komi J. Prevalence and impact of vaginal symptoms among postmenopausal women. J Sex Med. 2009;6(8):2133–2142.

- Kingsberg SA, Wysocki S, Magnus L, Krychman ML. Vulvar and vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women: findings from the REVIVE (REal Women’s VIews of Treatment Options for Menopausal Vaginal ChangEs) survey. J Sex Med. 2013;10(7):1790–1799.

- Nappi RE, Kokot-Kierepa M. Vaginal Health Insights, Views and Attitudes (VIVA)—results from an international survey. Climacteric. 2012;15(1):36–44.

- Nappi RE, Palacios S. Impact of vulvovaginal atrophy on sexual health and quality of life at postmenopause. Climacteric. 2014;17(1):3–9.

- Nappi RE, Kokot-Kierepa M. Women’s voices in menopause: results from an international survey on vaginal atrophy. Maturitas. 2010;67(3):233–238.

- Rahn DD, Carberry C, Sanses TV, et al. Vaginal estrogen for genitourinary syndrome of menopause: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(6):1147–1156.

- Suckling J, Lethaby A, Kennedy R. Local estrogen for vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;Oct 18(4):CD001500.

- Utian WH. A decade post WHI, menopausal hormone therapy comes full circle—need for independent commission. Climacteric 2012;15(4):320–325.

- Bachmann GA, Komi JO. Ospemifene effectively treats vulvovaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women: results from a pivotal phase 3 study. Ospemifene Study Group. Menopause. 2010;17(3):480–486.

- Wurz GT, Kao CT, Degregorio MW. Safety and efficacy of ospemifene for the treatment of dyspareunia associated with vulvar and vaginal atrophy due to menopause. Clin Interv Aging. 2014;9:1939–1950.

- Letter to Paolo Peruzzi. US Food and Drug Administration; September 5, 2014. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf13/K133895.pdf. Accessed July 8, 2015.

- Krychman ML, Shifren JL, Liu JH, Kingsberg SL, Utian WH. The North American Menopause Society Menopause e-Consult: Laser Treatment Safe for Vulvovaginal Atrophy? The North American Menopause Society (NAMS). 2015;11(3). http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/846960. Accessed July 8, 2015.

- Salvatore S, Nappi RE, Zerbinati N, et al. A 12-week treatment with fractional CO2 laser for vulvovaginal atrophy: a pilot study. Climacteric. 2014;17(4):363–369.

- Salvatore S, Maggiore ULR, Origoni M, et al. Microablative fractional CO2 laser improves dyspareunia related to vulvovaginal atrophy: a pilot study. J Endometriosis Pelvic Pain Disorders. 2014;6(3):121–162.

- Salvatore S, Nappi RE, Parma M, et al. Sexual function after fractional microablative CO2 laser in women with vulvovaginal atrophy. Climacteric. 2015;18(2):219–225.

- Salvatore S, Maggiore LR, Athanasiou S, et al. Histological study on the effects of microablative fractional CO2 laser on atrophic vaginal tissue; an ex vivo study. Menopause. 2015;22(8):845–849.

- Zerbinati N, Serati M, Origoni M, et al. Microscopic and ultrastructural modifications of postmenopausal atrophic vaginal mucosa after fractional carbon dioxide laser treatment. Lasers Med Sci. 2015;30(1):429–436.

- Tierney EP, Hanke CW. Ablative fractionated CO2, laser resurfacing for the neck: prospective study and review of the literature. J Drugs Dermatol. 2009;8(8):723–731.

- Peterson JD, Goldman MP. Rejuvenation of the aging chest: a review and our experience. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37(5):555–571.

Genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) is the new terminology to describe symptoms occurring secondary to vulvovaginal atrophy.1 The recent change in terminology originated with a consensus panel comprising the board of directors of the International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health (ISSWSH) and the board of trustees of the North American Menopause Society (NAMS). At a terminology consensus conference in May 2013, these groups determined that the term GSM is medically more accurate and all encompassing than vulvovaginal atrophy. It is also more publicly acceptable.

The symptoms of GSM derive from the hypoestrogenic state most commonly associated with menopause and its effects on the genitourinary tract.2 Vaginal symptoms associated with GSM include vaginal or vulvar dryness, discharge, itching, and dyspareunia.3 Histologically, a loss of superficial epithelial cells in the genitourinary tract leads to thinning of the tissue. There is then a loss of vaginal rugae and elasticity, leading to narrowing and shortening of the vagina.

In addition, the vaginal epithelium becomes much more fragile, which can lead to tears, bleeding, and fissures. There is also a loss of the subcutaneous fat of the labia majora, a change that can result in narrowing of the introitus, fusion of the labia majora, and shrinkage of the clitoral prepuce and urethra. The vaginal pH level becomes more alkaline, which may alter vaginal flora and increase the risk of urogenital infections—specifically, urinary tract infection (UTI). Vaginal secretions, largely transudate, from the vaginal vasculature also decrease over time. These changes lead to significant dyspareunia and impairment of sexual function.

In this article, we survey the therapies available for GSM, focusing first on proven treatments such as local estrogen administration and use of ospemifene (Osphena), and then describing an emerging treatment involving the use of fractional CO2 laser.

How prevalent is GSM?

Approximately half of all postmenopausal women in the United States report atrophy-related symptoms and a significant negative effect on quality of life.4–6 Few women with these symptoms seek medical attention.

The Vaginal Health: Insights, Views, and Attitudes (VIVA) survey found that 80% of women with genital atrophy considered its impact on their lives to be negative, 75% reported negative consequences in their sexual life, 68% reported that it made them feel less sexual, 33% reported negative effects on their marriage or relationship, and 26% reported a negative impact on their self-esteem.7

Another review of the impact of this condition by Nappi and Palacios estimated that, by the year 2025, there will be 1.1 billion women worldwide older than age 50 with specific needs related to GSM.8 Nappi and Palacios cite 4 recent surveys that suggest that health care providers need to be more proactive in helping patients disclose their symptoms. The same can be said of other symptoms of the urinary tract, such as urinary frequency, urgency, and incontinence, as well as pelvic floor relaxation.

A recently published international survey on vaginal atrophy not only depicts the extremely high prevalence of the condition but also describes fairly significant differences in attitudes toward symptoms between countries in Europe and North America.9 Overall, 77% of respondents, who included more than 4,000 menopausal women, believed that women were uncomfortable discussing symptoms of vaginal atrophy.9

Pastore and colleagues, using data from the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI), found the most prevalent urogenital symptoms to be vaginal dryness (27%), vaginal irritation or itching (18.6%), vaginal discharge (11.1%), and dysuria (5.2%).4 Unlike vasomotor symptoms of menopause, which tend to decrease over time, GSM does not spontaneously remit and commonly recurs when hormone therapy—the dominant treatment—is withdrawn.

What can we offer our patients?

Vaginal estrogen

The most common therapy used to manage GSM is estrogen. Most recommendations state that if the primary menopausal symptoms are related to vaginal atrophy, then local estrogen administration should be the primary mode of therapy. The Society of Gynecologic Surgeons Systematic Review Group recently concluded that all commercially available vaginal estrogens effectively can relieve common vulvovaginal atrophy−related symptoms and have additional utility in women with urinary urgency, frequency, stress incontinence, urge incontinence, and recurrent UTIs.10 Although their meta-analysis clearly demonstrated that estrogen therapy improves the symptoms of GSM, investigators acknowledged that a clearer understanding is needed of the exact risk to the endometrium with sustained use of vaginal estrogen, as well as a more precise assessment of changes in serum estradiol levels.10

A recent Cochrane review concluded that all forms of local estrogen appear to be equally effective for symptoms of vaginal atrophy.11 One trial cited in the review found significant adverse effects following administration of cream, compared with tablets, causing uterine bleeding, breast pain, and perineal pain.11

Another trial cited in the Cochrane review found significant endometrial overstimulation following use of cream, compared with the vaginal ring. As a treatment of choice, women appeared to favor the estradiol-releasing vaginal ring for ease of use, comfort of product, and overall satisfaction.11

After the release of the WHI data, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) released a “black box” warning on postmenopausal hormone use in women, which has significantly reduced the use of both local and systemic estrogen in eligible women. NAMS has recommended that the FDA revisit this warning, calling specifically for an independent commission to scrutinize every major WHI paper to determine whether the data justify the conclusions drawn.12

Most data back local estrogen as treatment for GSM

In 2013, the North American Menopause Society (NAMS) issued a position statement noting that the choice of therapy for genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) depends on the severity of symptoms, the efficacy and safety of therapy for the individual patient, and patient preference.1

To date, estrogen therapy is the most effective treatment for moderate to severe GSM, although a direct comparison of estrogen and ospemifene is lacking. Nonhormonal therapies available without a prescription provide sufficient relief for most women with mild symptoms. When low-dose estrogen is administered locally, a progestin is not indicated for women without a uterus—and generally is not indicated for women with an intact uterus. However, endometrial safety has not been studied in clinical trials beyond 1 year. Data are insufficient to confirm the safety of local estrogen in women with breast cancer.

Future research on the use of the fractional CO2 laser, which seems to be a promising emerging therapy, may provide clinicians with another option to treat the common and distressing problem of GSM.

Reference

1. Management of symptomatic vulvovaginal atrophy: 2013 position statement of the North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2013;20(9):888–902.

Ospemifene

This estrogen agonist and antagonist selectively stimulates or inhibits estrogen receptors of different target tissues, making it a selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM). In a study involving 826 postmenopausal women randomly allocated to 30 mg or 60 mg of ospemifene, the 60-mg dose proved to be more effective for improving vulvovaginal atrophy.13 Long-term safety studies revealed that ospemifene 60 mg given daily for 52 weeks was well tolerated and not associated with any endometrial- or breast-related safety issues.13,14 Common adverse effects of ospemifene reported during clinical trials included hot flashes, vaginal discharge, muscle spasms, general discharge, and excessive sweating.12

Vaginal lubricants and moisturizers

Nonestrogen water- or silicone-based vaginal lubricants and moisturizers may alleviate vaginal symptoms related to menopause. These products may be particularly helpful for women who do not wish to use hormone therapies.

Vaginal lubricants are intended to relieve friction and dyspareunia related to vaginal dryness during intercourse, with the ultimate goal of trapping moisture and providing long-term relief of vaginal dryness.

Although data are limited on the efficacy of these products, prospective studies have demonstrated that vaginal moisturizers improve vaginal dryness, pH balance, and elasticity and reduce vaginal itching, irritation, and dyspareunia.

Data are insufficient to support the use of herbal remedies or soy products for the treatment of vaginal symptoms.

An emerging therapy: fractional CO2 laser

In September 2014, the FDA cleared for use the SmartXide2 CO2 laser system (DEKA Medical) for “incision, excision, vaporization and coagulation of body soft tissues” in medical specialties that include gynecology and genitourinary surgery.15 The system, also marketed by Cynosure as the MonaLisa Touch treatment, was not approved specifically for treatment of GSM—and it is important to note that the path to device clearance by the FDA is much less cumbersome than the route to drug approval. As NAMS notes in an article about the fractional CO2 laser, “Device clearance does not require the large, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trials with established efficacy and safety endpoints required for the approval of new drugs.”16 Nevertheless, this laser system appears to be poised to become a new treatment for the symptoms of GSM.

This laser supplies energy with a specific pulse to the vaginal wall to rapidly and superficially ablate the epithelial component of atrophic mucosa, which is characterized by low water content. Ablation is followed by tissue coagulation, stimulated by laser energy penetrating into deeper tissues, triggering the synthesis of new collagen and other components of the ground substance of the matrix.

The supraphysiologic level of heat generated by the CO2 laser induces a rapid and transient heat-shock response that temporarily alters cellular metabolism and activates a small family of proteins referred to as the “heat shock proteins” (HSPs). HSP 70, which is overexpressed following laser treatment, stimulates transforming growthfactor‑beta, triggering an inflammatory response that stimulates fibroblasts, which produce new collagen and extracellular matrix.

The laser has emissions characteristics aligned for the transfer of the energy load to the mucosa while avoiding excessive localized damage. This aspect of its design allows for restoration of the permeability of the connective tissue, enabling the physiologic transfer of various nutrients from capillaries to tissues. When there is a loss of estrogen, as during menopause, vaginal atrophy develops, with the epithelium deteriorating and thinning. The fractional CO2 laser therapy improves the state of the epithelium by restoring epithelial cell trophism.

The vaginal dryness that occurs with atrophy is due to poor blood flow, as well as reduced activity of the fibroblasts in the deeper tissue. The increased lubrication that occurs after treatment is usually a vaginal transudate from blood outflow through the capillaries that supply blood to the vaginal epithelium. The high presence of water molecules increases permeability, allowing easier transport of metabolites and nutrients from capillaries to tissue, as well as the drainage of waste products from tissues to blood and lymph vessels.

With atrophy, the glycogen in the epithelial cells decreases. Because lactobacilli need glycogen to thrive and are responsible for maintaining the acidity of the vagina, the pH level increases. With the restoration of trophism, glycogen levels increase, furthering colonization of vaginal lactobacilli as well as vaginal acidity, reducing the pH level. This effect also may protect against the development of recurrent UTIs.

A look at the data

To date, more than 2,000 women in Italy and more than 10,000 women worldwide with GSM have been treated with fractional CO2 laser therapy, and several peer-reviewed publications have documented its efficacy and safety.17–21

In published studies, however, the populations have been small and the investigations have been mostly short term (12 weeks).17–21

A pilot study reported that a treatment cycle of 3 laser applications significantly improved the most bothersome symptoms of vulvovaginal atrophy and improved scores of vaginal health at 12 weeks’ follow-up in 50 women who had not responded to or were unsatisfied with local estrogen therapy.17 This investigation was followed by 2 additional studies involving another 92 women that specifically addressed the impact of fractional CO2 laser therapy on dyspareunia and female sexual function.19,20 Both studies showed statistically significant improvement in dyspareunia as well as Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) scores. All women in these studies were treated in an office setting with no pretreatment anesthesia. No adverse events were reported.

Recently published histology data highlight significant changes 1 month after fractional CO2 laser treatment that included a much thicker epithelium with wide columns of large epithelial cells rich in glycogen.21 Also noted was a significant reorganization of connective tissue, both in the lamina propria and the core of the papillae (FIGURES 1 and 2).

| FIGURE 1: Early-stage vaginal atrophy   |

FIGURE 2: Atrophic vaginitis   This histologic preparation of vaginal mucosa sections shows untreated atrophic vaginitis (A) and the same mucosa 1 month after treatment with fractional CO2 laser therapy (B). Reprinted with permission from DEKA M.E.L.A. Srl (Calenzano, Italy) and Professor A. Calligaro, University of Pavia, Italy. |

Caveats

No International Classification of Diseases (ICD) 9 or 10 code has been assigned to the procedure to date, and the cost to the patient ranges from $600 to $1,000 per procedure.16

NAMS position. A review of the technology by NAMS noted the need for large, long-term, randomized, sham-controlled studies “to further evaluate the safety and efficacy of this procedure.”16

NAMS also notes that “lasers have become a very costly option for the treatment of symptomatic [GSM], without a single trial comparing active laser treatment to sham laser treatment and no information on long-term safety. In all published trials to date, only several hundred women have been studied and most studies are only 12 weeks in duration.”16

Not a new concept. The concept of treating skin with a microablative CO2 laser is not new. This laser has been safely used on the skin of the face, neck, and chest to produce new collagen and elastin fibers with remodeling of tissue.22,23

Preliminary data on the use of a fractionated CO2 microablative laser to treat symptoms associated with GSM suggest that the therapy is feasible, effective, and safe in the short term. If these findings are confirmed by larger, longer-term, well-controlled studies, this laser will be an additional safe and effective treatment for this very common and distressing disorder.

Two authors (Mickey Karram, MD, and Eric Sokol, MD) are performing a study of the fractional CO2 laser for treatment of genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) in the United States. To date, 30 women with GSM have been treated with 3 cycles and followed for 3 months. Preliminary data show significant improvement in all symptoms, with all patients treated in an office setting with no pretreatment or posttreatment analgesia required.

The laser settings for treatment included a power of 30 W, a dwell time of 1,000 µs, spacing between 2 adjacent treated spots of 1,000 µs, and a stack parameter for pulses from 1 to 3.

Laser energy is delivered through a specially designed scanner and a vaginal probe. The probe is slowly inserted to the top of the vaginal canal and then gradually withdrawn, treating the vaginal epithelium at increments of almost 1 cm (FIGURE 3). The laser beam projects onto a 45° mirror placed at the tip of the probe, which reflects it at 90°, thereby ensuring that only the vaginal wall is treated, and not the uterine cervix.

A treatment cycle included 3 laser treatments at 6-week intervals. Each treatment lasted 3 to 5 minutes. Initial improvement was noted in most patients, including increased lubrication within 1 week after the first treatment, with further improvement after each session. To date, the positive results have persisted, and all women in the trial now have been followed for 3 months—all have noted improvement in symptoms. They will continue periodic assessment, with a final subjective and objective evaluation 1 year after their first treatment.

Bottom line

Although preliminary studies of the fractional CO2 laser as a treatment for GSM are promising, local estrogen is backed by a large body of reliable data. Ospemifene also has FDA approval for treatment of this disorder.

For women who cannot or will not use a hormone-based therapy, vaginal lubricants and moisturizer may offer at least some relief.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) is the new terminology to describe symptoms occurring secondary to vulvovaginal atrophy.1 The recent change in terminology originated with a consensus panel comprising the board of directors of the International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health (ISSWSH) and the board of trustees of the North American Menopause Society (NAMS). At a terminology consensus conference in May 2013, these groups determined that the term GSM is medically more accurate and all encompassing than vulvovaginal atrophy. It is also more publicly acceptable.

The symptoms of GSM derive from the hypoestrogenic state most commonly associated with menopause and its effects on the genitourinary tract.2 Vaginal symptoms associated with GSM include vaginal or vulvar dryness, discharge, itching, and dyspareunia.3 Histologically, a loss of superficial epithelial cells in the genitourinary tract leads to thinning of the tissue. There is then a loss of vaginal rugae and elasticity, leading to narrowing and shortening of the vagina.

In addition, the vaginal epithelium becomes much more fragile, which can lead to tears, bleeding, and fissures. There is also a loss of the subcutaneous fat of the labia majora, a change that can result in narrowing of the introitus, fusion of the labia majora, and shrinkage of the clitoral prepuce and urethra. The vaginal pH level becomes more alkaline, which may alter vaginal flora and increase the risk of urogenital infections—specifically, urinary tract infection (UTI). Vaginal secretions, largely transudate, from the vaginal vasculature also decrease over time. These changes lead to significant dyspareunia and impairment of sexual function.

In this article, we survey the therapies available for GSM, focusing first on proven treatments such as local estrogen administration and use of ospemifene (Osphena), and then describing an emerging treatment involving the use of fractional CO2 laser.

How prevalent is GSM?

Approximately half of all postmenopausal women in the United States report atrophy-related symptoms and a significant negative effect on quality of life.4–6 Few women with these symptoms seek medical attention.

The Vaginal Health: Insights, Views, and Attitudes (VIVA) survey found that 80% of women with genital atrophy considered its impact on their lives to be negative, 75% reported negative consequences in their sexual life, 68% reported that it made them feel less sexual, 33% reported negative effects on their marriage or relationship, and 26% reported a negative impact on their self-esteem.7

Another review of the impact of this condition by Nappi and Palacios estimated that, by the year 2025, there will be 1.1 billion women worldwide older than age 50 with specific needs related to GSM.8 Nappi and Palacios cite 4 recent surveys that suggest that health care providers need to be more proactive in helping patients disclose their symptoms. The same can be said of other symptoms of the urinary tract, such as urinary frequency, urgency, and incontinence, as well as pelvic floor relaxation.

A recently published international survey on vaginal atrophy not only depicts the extremely high prevalence of the condition but also describes fairly significant differences in attitudes toward symptoms between countries in Europe and North America.9 Overall, 77% of respondents, who included more than 4,000 menopausal women, believed that women were uncomfortable discussing symptoms of vaginal atrophy.9

Pastore and colleagues, using data from the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI), found the most prevalent urogenital symptoms to be vaginal dryness (27%), vaginal irritation or itching (18.6%), vaginal discharge (11.1%), and dysuria (5.2%).4 Unlike vasomotor symptoms of menopause, which tend to decrease over time, GSM does not spontaneously remit and commonly recurs when hormone therapy—the dominant treatment—is withdrawn.

What can we offer our patients?

Vaginal estrogen

The most common therapy used to manage GSM is estrogen. Most recommendations state that if the primary menopausal symptoms are related to vaginal atrophy, then local estrogen administration should be the primary mode of therapy. The Society of Gynecologic Surgeons Systematic Review Group recently concluded that all commercially available vaginal estrogens effectively can relieve common vulvovaginal atrophy−related symptoms and have additional utility in women with urinary urgency, frequency, stress incontinence, urge incontinence, and recurrent UTIs.10 Although their meta-analysis clearly demonstrated that estrogen therapy improves the symptoms of GSM, investigators acknowledged that a clearer understanding is needed of the exact risk to the endometrium with sustained use of vaginal estrogen, as well as a more precise assessment of changes in serum estradiol levels.10

A recent Cochrane review concluded that all forms of local estrogen appear to be equally effective for symptoms of vaginal atrophy.11 One trial cited in the review found significant adverse effects following administration of cream, compared with tablets, causing uterine bleeding, breast pain, and perineal pain.11

Another trial cited in the Cochrane review found significant endometrial overstimulation following use of cream, compared with the vaginal ring. As a treatment of choice, women appeared to favor the estradiol-releasing vaginal ring for ease of use, comfort of product, and overall satisfaction.11

After the release of the WHI data, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) released a “black box” warning on postmenopausal hormone use in women, which has significantly reduced the use of both local and systemic estrogen in eligible women. NAMS has recommended that the FDA revisit this warning, calling specifically for an independent commission to scrutinize every major WHI paper to determine whether the data justify the conclusions drawn.12

Most data back local estrogen as treatment for GSM

In 2013, the North American Menopause Society (NAMS) issued a position statement noting that the choice of therapy for genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) depends on the severity of symptoms, the efficacy and safety of therapy for the individual patient, and patient preference.1

To date, estrogen therapy is the most effective treatment for moderate to severe GSM, although a direct comparison of estrogen and ospemifene is lacking. Nonhormonal therapies available without a prescription provide sufficient relief for most women with mild symptoms. When low-dose estrogen is administered locally, a progestin is not indicated for women without a uterus—and generally is not indicated for women with an intact uterus. However, endometrial safety has not been studied in clinical trials beyond 1 year. Data are insufficient to confirm the safety of local estrogen in women with breast cancer.

Future research on the use of the fractional CO2 laser, which seems to be a promising emerging therapy, may provide clinicians with another option to treat the common and distressing problem of GSM.

Reference

1. Management of symptomatic vulvovaginal atrophy: 2013 position statement of the North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2013;20(9):888–902.

Ospemifene

This estrogen agonist and antagonist selectively stimulates or inhibits estrogen receptors of different target tissues, making it a selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM). In a study involving 826 postmenopausal women randomly allocated to 30 mg or 60 mg of ospemifene, the 60-mg dose proved to be more effective for improving vulvovaginal atrophy.13 Long-term safety studies revealed that ospemifene 60 mg given daily for 52 weeks was well tolerated and not associated with any endometrial- or breast-related safety issues.13,14 Common adverse effects of ospemifene reported during clinical trials included hot flashes, vaginal discharge, muscle spasms, general discharge, and excessive sweating.12

Vaginal lubricants and moisturizers

Nonestrogen water- or silicone-based vaginal lubricants and moisturizers may alleviate vaginal symptoms related to menopause. These products may be particularly helpful for women who do not wish to use hormone therapies.

Vaginal lubricants are intended to relieve friction and dyspareunia related to vaginal dryness during intercourse, with the ultimate goal of trapping moisture and providing long-term relief of vaginal dryness.

Although data are limited on the efficacy of these products, prospective studies have demonstrated that vaginal moisturizers improve vaginal dryness, pH balance, and elasticity and reduce vaginal itching, irritation, and dyspareunia.

Data are insufficient to support the use of herbal remedies or soy products for the treatment of vaginal symptoms.

An emerging therapy: fractional CO2 laser

In September 2014, the FDA cleared for use the SmartXide2 CO2 laser system (DEKA Medical) for “incision, excision, vaporization and coagulation of body soft tissues” in medical specialties that include gynecology and genitourinary surgery.15 The system, also marketed by Cynosure as the MonaLisa Touch treatment, was not approved specifically for treatment of GSM—and it is important to note that the path to device clearance by the FDA is much less cumbersome than the route to drug approval. As NAMS notes in an article about the fractional CO2 laser, “Device clearance does not require the large, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trials with established efficacy and safety endpoints required for the approval of new drugs.”16 Nevertheless, this laser system appears to be poised to become a new treatment for the symptoms of GSM.

This laser supplies energy with a specific pulse to the vaginal wall to rapidly and superficially ablate the epithelial component of atrophic mucosa, which is characterized by low water content. Ablation is followed by tissue coagulation, stimulated by laser energy penetrating into deeper tissues, triggering the synthesis of new collagen and other components of the ground substance of the matrix.

The supraphysiologic level of heat generated by the CO2 laser induces a rapid and transient heat-shock response that temporarily alters cellular metabolism and activates a small family of proteins referred to as the “heat shock proteins” (HSPs). HSP 70, which is overexpressed following laser treatment, stimulates transforming growthfactor‑beta, triggering an inflammatory response that stimulates fibroblasts, which produce new collagen and extracellular matrix.

The laser has emissions characteristics aligned for the transfer of the energy load to the mucosa while avoiding excessive localized damage. This aspect of its design allows for restoration of the permeability of the connective tissue, enabling the physiologic transfer of various nutrients from capillaries to tissues. When there is a loss of estrogen, as during menopause, vaginal atrophy develops, with the epithelium deteriorating and thinning. The fractional CO2 laser therapy improves the state of the epithelium by restoring epithelial cell trophism.

The vaginal dryness that occurs with atrophy is due to poor blood flow, as well as reduced activity of the fibroblasts in the deeper tissue. The increased lubrication that occurs after treatment is usually a vaginal transudate from blood outflow through the capillaries that supply blood to the vaginal epithelium. The high presence of water molecules increases permeability, allowing easier transport of metabolites and nutrients from capillaries to tissue, as well as the drainage of waste products from tissues to blood and lymph vessels.

With atrophy, the glycogen in the epithelial cells decreases. Because lactobacilli need glycogen to thrive and are responsible for maintaining the acidity of the vagina, the pH level increases. With the restoration of trophism, glycogen levels increase, furthering colonization of vaginal lactobacilli as well as vaginal acidity, reducing the pH level. This effect also may protect against the development of recurrent UTIs.

A look at the data

To date, more than 2,000 women in Italy and more than 10,000 women worldwide with GSM have been treated with fractional CO2 laser therapy, and several peer-reviewed publications have documented its efficacy and safety.17–21

In published studies, however, the populations have been small and the investigations have been mostly short term (12 weeks).17–21

A pilot study reported that a treatment cycle of 3 laser applications significantly improved the most bothersome symptoms of vulvovaginal atrophy and improved scores of vaginal health at 12 weeks’ follow-up in 50 women who had not responded to or were unsatisfied with local estrogen therapy.17 This investigation was followed by 2 additional studies involving another 92 women that specifically addressed the impact of fractional CO2 laser therapy on dyspareunia and female sexual function.19,20 Both studies showed statistically significant improvement in dyspareunia as well as Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) scores. All women in these studies were treated in an office setting with no pretreatment anesthesia. No adverse events were reported.

Recently published histology data highlight significant changes 1 month after fractional CO2 laser treatment that included a much thicker epithelium with wide columns of large epithelial cells rich in glycogen.21 Also noted was a significant reorganization of connective tissue, both in the lamina propria and the core of the papillae (FIGURES 1 and 2).

| FIGURE 1: Early-stage vaginal atrophy   |

FIGURE 2: Atrophic vaginitis   This histologic preparation of vaginal mucosa sections shows untreated atrophic vaginitis (A) and the same mucosa 1 month after treatment with fractional CO2 laser therapy (B). Reprinted with permission from DEKA M.E.L.A. Srl (Calenzano, Italy) and Professor A. Calligaro, University of Pavia, Italy. |

Caveats

No International Classification of Diseases (ICD) 9 or 10 code has been assigned to the procedure to date, and the cost to the patient ranges from $600 to $1,000 per procedure.16

NAMS position. A review of the technology by NAMS noted the need for large, long-term, randomized, sham-controlled studies “to further evaluate the safety and efficacy of this procedure.”16

NAMS also notes that “lasers have become a very costly option for the treatment of symptomatic [GSM], without a single trial comparing active laser treatment to sham laser treatment and no information on long-term safety. In all published trials to date, only several hundred women have been studied and most studies are only 12 weeks in duration.”16

Not a new concept. The concept of treating skin with a microablative CO2 laser is not new. This laser has been safely used on the skin of the face, neck, and chest to produce new collagen and elastin fibers with remodeling of tissue.22,23

Preliminary data on the use of a fractionated CO2 microablative laser to treat symptoms associated with GSM suggest that the therapy is feasible, effective, and safe in the short term. If these findings are confirmed by larger, longer-term, well-controlled studies, this laser will be an additional safe and effective treatment for this very common and distressing disorder.

Two authors (Mickey Karram, MD, and Eric Sokol, MD) are performing a study of the fractional CO2 laser for treatment of genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) in the United States. To date, 30 women with GSM have been treated with 3 cycles and followed for 3 months. Preliminary data show significant improvement in all symptoms, with all patients treated in an office setting with no pretreatment or posttreatment analgesia required.

The laser settings for treatment included a power of 30 W, a dwell time of 1,000 µs, spacing between 2 adjacent treated spots of 1,000 µs, and a stack parameter for pulses from 1 to 3.

Laser energy is delivered through a specially designed scanner and a vaginal probe. The probe is slowly inserted to the top of the vaginal canal and then gradually withdrawn, treating the vaginal epithelium at increments of almost 1 cm (FIGURE 3). The laser beam projects onto a 45° mirror placed at the tip of the probe, which reflects it at 90°, thereby ensuring that only the vaginal wall is treated, and not the uterine cervix.

A treatment cycle included 3 laser treatments at 6-week intervals. Each treatment lasted 3 to 5 minutes. Initial improvement was noted in most patients, including increased lubrication within 1 week after the first treatment, with further improvement after each session. To date, the positive results have persisted, and all women in the trial now have been followed for 3 months—all have noted improvement in symptoms. They will continue periodic assessment, with a final subjective and objective evaluation 1 year after their first treatment.

Bottom line

Although preliminary studies of the fractional CO2 laser as a treatment for GSM are promising, local estrogen is backed by a large body of reliable data. Ospemifene also has FDA approval for treatment of this disorder.

For women who cannot or will not use a hormone-based therapy, vaginal lubricants and moisturizer may offer at least some relief.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Portman DJ, Gass ML. Genitourinary syndrome of menopause: new terminology for vulvovaginal atrophy from the International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health and the North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2014;21(10):1–6.

- Calleja-Agius J, Brincat MP. Urogenital atrophy. Climacteric. 2009;12(4):279–285.

- Mehta A, Bachmann G. Vulvovaginal complaints. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2008;51(3):549–555.

- Pastore LM, Carter RA, Hulka BS, Wells E. Self-reported urogenital symptoms in postmenopausal women: Women’s Health Initiative. Maturitas. 2004;49(4):292–303.

- Santoro N, Komi J. Prevalence and impact of vaginal symptoms among postmenopausal women. J Sex Med. 2009;6(8):2133–2142.

- Kingsberg SA, Wysocki S, Magnus L, Krychman ML. Vulvar and vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women: findings from the REVIVE (REal Women’s VIews of Treatment Options for Menopausal Vaginal ChangEs) survey. J Sex Med. 2013;10(7):1790–1799.

- Nappi RE, Kokot-Kierepa M. Vaginal Health Insights, Views and Attitudes (VIVA)—results from an international survey. Climacteric. 2012;15(1):36–44.

- Nappi RE, Palacios S. Impact of vulvovaginal atrophy on sexual health and quality of life at postmenopause. Climacteric. 2014;17(1):3–9.

- Nappi RE, Kokot-Kierepa M. Women’s voices in menopause: results from an international survey on vaginal atrophy. Maturitas. 2010;67(3):233–238.

- Rahn DD, Carberry C, Sanses TV, et al. Vaginal estrogen for genitourinary syndrome of menopause: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(6):1147–1156.

- Suckling J, Lethaby A, Kennedy R. Local estrogen for vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;Oct 18(4):CD001500.

- Utian WH. A decade post WHI, menopausal hormone therapy comes full circle—need for independent commission. Climacteric 2012;15(4):320–325.

- Bachmann GA, Komi JO. Ospemifene effectively treats vulvovaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women: results from a pivotal phase 3 study. Ospemifene Study Group. Menopause. 2010;17(3):480–486.

- Wurz GT, Kao CT, Degregorio MW. Safety and efficacy of ospemifene for the treatment of dyspareunia associated with vulvar and vaginal atrophy due to menopause. Clin Interv Aging. 2014;9:1939–1950.

- Letter to Paolo Peruzzi. US Food and Drug Administration; September 5, 2014. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf13/K133895.pdf. Accessed July 8, 2015.

- Krychman ML, Shifren JL, Liu JH, Kingsberg SL, Utian WH. The North American Menopause Society Menopause e-Consult: Laser Treatment Safe for Vulvovaginal Atrophy? The North American Menopause Society (NAMS). 2015;11(3). http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/846960. Accessed July 8, 2015.

- Salvatore S, Nappi RE, Zerbinati N, et al. A 12-week treatment with fractional CO2 laser for vulvovaginal atrophy: a pilot study. Climacteric. 2014;17(4):363–369.

- Salvatore S, Maggiore ULR, Origoni M, et al. Microablative fractional CO2 laser improves dyspareunia related to vulvovaginal atrophy: a pilot study. J Endometriosis Pelvic Pain Disorders. 2014;6(3):121–162.

- Salvatore S, Nappi RE, Parma M, et al. Sexual function after fractional microablative CO2 laser in women with vulvovaginal atrophy. Climacteric. 2015;18(2):219–225.

- Salvatore S, Maggiore LR, Athanasiou S, et al. Histological study on the effects of microablative fractional CO2 laser on atrophic vaginal tissue; an ex vivo study. Menopause. 2015;22(8):845–849.

- Zerbinati N, Serati M, Origoni M, et al. Microscopic and ultrastructural modifications of postmenopausal atrophic vaginal mucosa after fractional carbon dioxide laser treatment. Lasers Med Sci. 2015;30(1):429–436.

- Tierney EP, Hanke CW. Ablative fractionated CO2, laser resurfacing for the neck: prospective study and review of the literature. J Drugs Dermatol. 2009;8(8):723–731.

- Peterson JD, Goldman MP. Rejuvenation of the aging chest: a review and our experience. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37(5):555–571.

- Portman DJ, Gass ML. Genitourinary syndrome of menopause: new terminology for vulvovaginal atrophy from the International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health and the North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2014;21(10):1–6.

- Calleja-Agius J, Brincat MP. Urogenital atrophy. Climacteric. 2009;12(4):279–285.

- Mehta A, Bachmann G. Vulvovaginal complaints. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2008;51(3):549–555.

- Pastore LM, Carter RA, Hulka BS, Wells E. Self-reported urogenital symptoms in postmenopausal women: Women’s Health Initiative. Maturitas. 2004;49(4):292–303.

- Santoro N, Komi J. Prevalence and impact of vaginal symptoms among postmenopausal women. J Sex Med. 2009;6(8):2133–2142.

- Kingsberg SA, Wysocki S, Magnus L, Krychman ML. Vulvar and vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women: findings from the REVIVE (REal Women’s VIews of Treatment Options for Menopausal Vaginal ChangEs) survey. J Sex Med. 2013;10(7):1790–1799.

- Nappi RE, Kokot-Kierepa M. Vaginal Health Insights, Views and Attitudes (VIVA)—results from an international survey. Climacteric. 2012;15(1):36–44.

- Nappi RE, Palacios S. Impact of vulvovaginal atrophy on sexual health and quality of life at postmenopause. Climacteric. 2014;17(1):3–9.

- Nappi RE, Kokot-Kierepa M. Women’s voices in menopause: results from an international survey on vaginal atrophy. Maturitas. 2010;67(3):233–238.

- Rahn DD, Carberry C, Sanses TV, et al. Vaginal estrogen for genitourinary syndrome of menopause: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(6):1147–1156.

- Suckling J, Lethaby A, Kennedy R. Local estrogen for vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;Oct 18(4):CD001500.

- Utian WH. A decade post WHI, menopausal hormone therapy comes full circle—need for independent commission. Climacteric 2012;15(4):320–325.

- Bachmann GA, Komi JO. Ospemifene effectively treats vulvovaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women: results from a pivotal phase 3 study. Ospemifene Study Group. Menopause. 2010;17(3):480–486.

- Wurz GT, Kao CT, Degregorio MW. Safety and efficacy of ospemifene for the treatment of dyspareunia associated with vulvar and vaginal atrophy due to menopause. Clin Interv Aging. 2014;9:1939–1950.

- Letter to Paolo Peruzzi. US Food and Drug Administration; September 5, 2014. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf13/K133895.pdf. Accessed July 8, 2015.

- Krychman ML, Shifren JL, Liu JH, Kingsberg SL, Utian WH. The North American Menopause Society Menopause e-Consult: Laser Treatment Safe for Vulvovaginal Atrophy? The North American Menopause Society (NAMS). 2015;11(3). http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/846960. Accessed July 8, 2015.

- Salvatore S, Nappi RE, Zerbinati N, et al. A 12-week treatment with fractional CO2 laser for vulvovaginal atrophy: a pilot study. Climacteric. 2014;17(4):363–369.

- Salvatore S, Maggiore ULR, Origoni M, et al. Microablative fractional CO2 laser improves dyspareunia related to vulvovaginal atrophy: a pilot study. J Endometriosis Pelvic Pain Disorders. 2014;6(3):121–162.

- Salvatore S, Nappi RE, Parma M, et al. Sexual function after fractional microablative CO2 laser in women with vulvovaginal atrophy. Climacteric. 2015;18(2):219–225.

- Salvatore S, Maggiore LR, Athanasiou S, et al. Histological study on the effects of microablative fractional CO2 laser on atrophic vaginal tissue; an ex vivo study. Menopause. 2015;22(8):845–849.

- Zerbinati N, Serati M, Origoni M, et al. Microscopic and ultrastructural modifications of postmenopausal atrophic vaginal mucosa after fractional carbon dioxide laser treatment. Lasers Med Sci. 2015;30(1):429–436.

- Tierney EP, Hanke CW. Ablative fractionated CO2, laser resurfacing for the neck: prospective study and review of the literature. J Drugs Dermatol. 2009;8(8):723–731.

- Peterson JD, Goldman MP. Rejuvenation of the aging chest: a review and our experience. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37(5):555–571.

In this article

- What can we offer our patients?

- Fractional CO2 laser: a study in progress

- Bottom line