User login

Multiple hyperpigmented papules and plaques

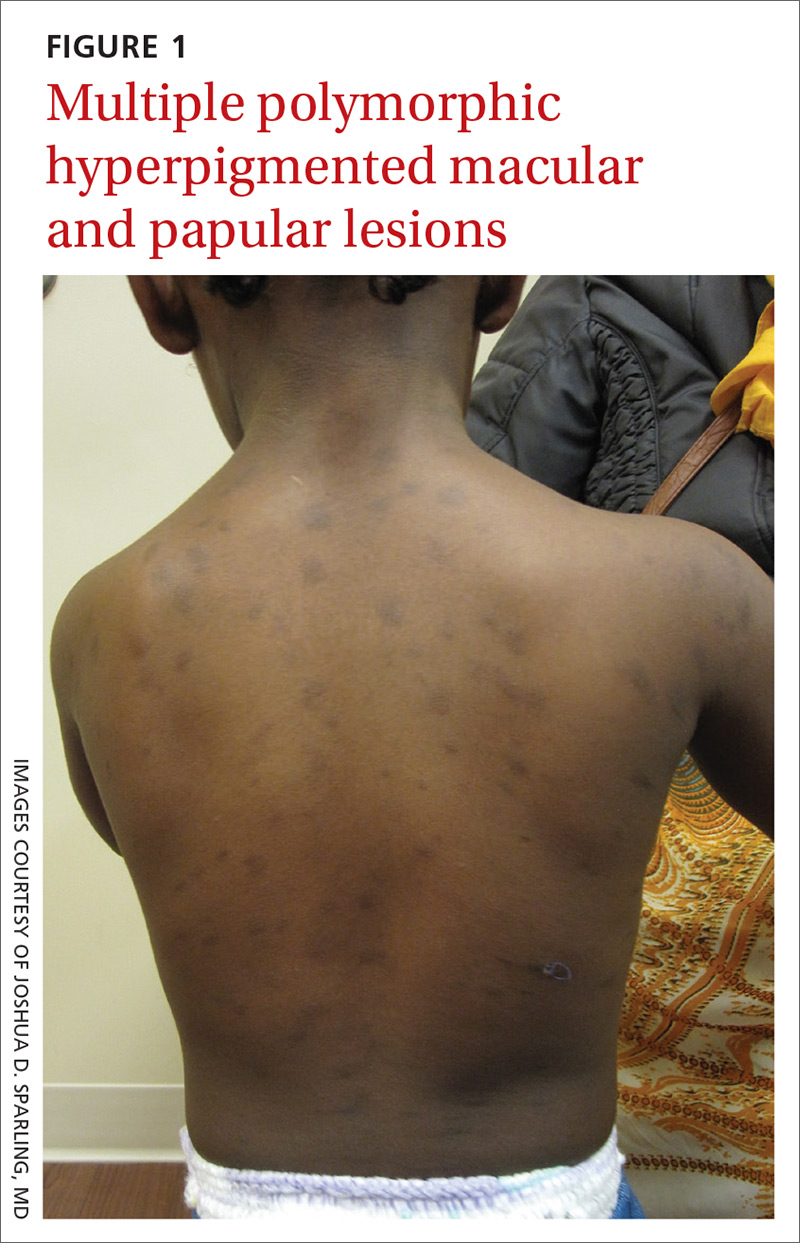

A 2-year-old girl with Fitzpatrick skin type VI who had recently emigrated from Djibouti presented to our dermatology clinic for a rash that appeared when she was 2 months old. The lesions occasionally were pruritic after sun exposure or after crawling outside. There was no associated abdominal pain, diarrhea, flushing, or hypotension. Topical moisturizers were not helpful.

The patient had no known allergies or other notable medical history. Physical examination revealed multiple hyperpigmented, oval-shaped, slightly raised papules and plaques on her torso (FIGURE 1), neck, and arms, and fewer lesions on her face and legs. Darier sign was not appreciated on the initial consult. A 4-mm punch biopsy of the patient’s right middle back was performed at this visit.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Mastocytosis

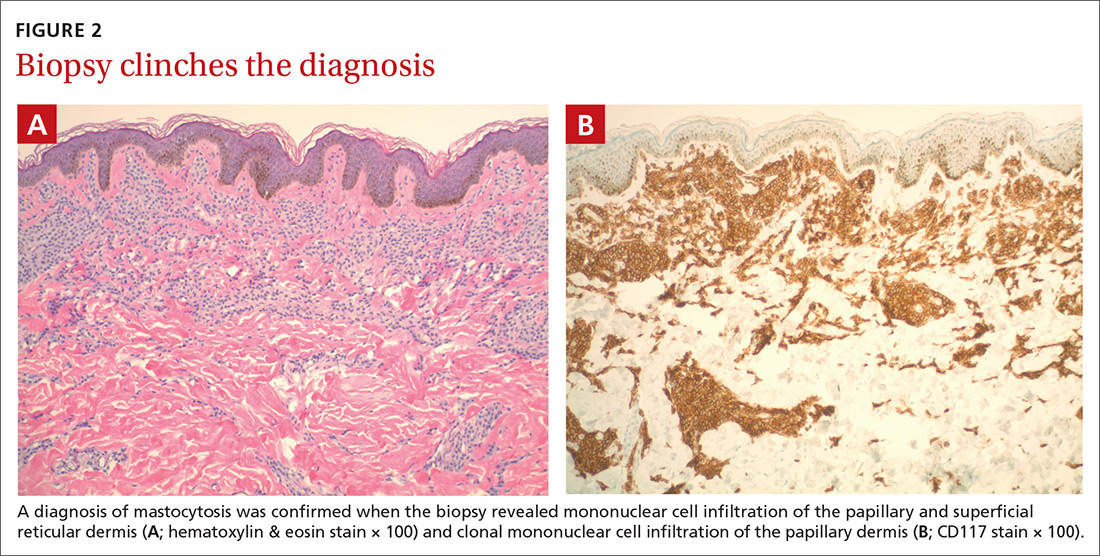

The presence of a hyperpigmented skin lesion that becomes pruritic, raised, and erythematous when rubbed (Darier sign) is the major criterion for the diagnosis of cutaneous mastocytosis.1 Minor criteria include a skin biopsy demonstrating a 4- to 8-fold increase in the number of mast cells within the papillary dermis and the presence of cKIT mutations.1 In this case, the patient’s punch biopsy results came back positive for clonal mast cell infiltration of the papillary dermis (FIGURES 2A and 2B), and her physician elicited a slightly positive Darier sign during a follow-up visit.

Mastocytosis is characterized by pathognomonic proliferation of clonal mast cells with either cutaneous or systemic involvement.1 Mast cell expansion most commonly is found in the skin and bone marrow; however, involvement of the gastrointestinal tract, liver, spleen, and lymph nodes also has been documented.1 Nonhereditary somatic mutations of the cKIT gene have been observed in many studies and may be associated with increased proliferation of clonal mast cells.2

A review of the English-language literature on cutaneous mastocytosis reveals a paucity of reports in darker skin types. However, it is important for clinicians to be able to recognize this disease in all skin types.

Three subcategories. Cutaneous mastocytosis is divided into 3 subcategories: mastocytoma of the skin (1–3 solitary skin lesions), maculopapular cutaneous mastocytosis, also known as urticaria pigmentosa (as seen in our patient; usually ≥ 4 lesions); and diffuse cutaneous mastocytosis (confluent lesions; leathery appearance of skin).1,3,4 Maculopapular cutaneous mastocytosis, which our patient had, classically develops within the first 6 months of life and presents as hyperpigmented macules and papules.

Keep in mind that systemic involvement in cutaneous mastocytosis occasionally occurs and can be associated with anaphylaxis, flushing, headache, dyspnea, nausea, emesis, diarrhea, abdominal pain, and hepatosplenomegaly.2

Continue to: Narrowing down a broad differential diagnosis

Narrowing down a broad differential diagnosis

Our cas a ase was made somewhat challenging by the patient’s darkly pigmented skin color, which made any erythema and other cutaneous signs less visible. The differential was broad and included postinflammatory hyperpigmentation from eczema, multiple congenital nevi, sarcoidosis, leprosy, and cutaneous tuberculosis, all of which can be eliminated by performing a biopsy of the lesion.

Diagnostic criteria include biopsy and laboratory findings

In addition to a skin biopsy, initial assessment in cases of suspected cutaneous mastocytosis should include a complete blood cell count with differential, liver function tests (+/- liver ultrasound), a serum tryptase level, and a peripheral smear. Serum tryptase levels > 20 ng/mL have been shown to correlate with a higher probability of systemic mastocytosis. Higher tryptase levels also correlate with severity of disease in children.5

Treatment focuses on minimizing mast cell degranulation

Due to the relatively benign course of cutaneous mastocytosis, the mainstay of treatment is focused on minimizing mast cell degranulation to control subsequent symptoms. Avoiding precipitating factors such as temperature extremes, external stimulation of lesions, dry skin, infection, and certain medications (eg, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, aspirin, morphine, polymyxin B sulphate, anticholinergics, some systemic anesthetics) that can stimulate mast cell degranulation is encouraged.2 H1 and H2 antihistamines are the first-line treatment for mild to moderate symptoms. In refractory cases, leukotriene receptor antagonists or oral cromolyn sodium may be considered.2

Regular follow-up every 6 to 12 months should be established after diagnosis.1 If symptoms persist into adulthood or concern for disease progression is high, a bone marrow biopsy is recommended.1

Our patient

Our patient’s laboratory results revealed a normal serum tryptase level (3.4 ng/mL; reference range < 11.5 ng/mL) and complete blood cell count. A complete metabolic panel demonstrated elevated and high-normal liver function tests with alanine aminotransferase (ALT) at 111 u/L (reference range, 10–40 u/L) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) at 55 u/L (reference range, 7–56 u/L).

Continue to: As a precaution...

As a precaution and for consideration of further work-up, such as the need for a liver ultrasound, the patient was referred to Pediatric Gastroenterology. The specialist repeated the liver function tests, the results of which were lower (ALT, 42 u/L; AST, 24 u/L); a liver ultrasound was thought to be unnecessary.

Our patient’s otherwise negative review of systems led the specialist to feel confident that no systemic disease was present at the time. These results were discussed with the patient’s parents and counseling about trigger avoidance was provided. The patient was given pediatric-dosed oral and topical H1 antihistamines for symptom relief.

CORRESPONDENCE

Joshua D. Sparling, MD, 6 E Chestnut Street, Ste 340, Augusta, ME 04330; Joshua.Sparling@MaineGeneral.org

1. Hartmann K, Escribano L, Grattan C, et al . Cutaneous manifestations in patients with mastocytosis: consensus report of the European Competence Network on Mastocytosis; the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology; and the European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137:35-45.

2. Abid A, Malone MA, Curci K. Mastocytosis. Prim Care. 2016;43:505-518.

3. Forster A, Hartmann K, Horny HP, et al. Large maculopapular cutaneous lesions are associated with favourable outcome in childhood-onset mastocytosis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136:1581-1590.

4. Tharp MD, Sofen BD. Mastocytosis. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. China: Elsevier; 2018:2103-2104.

5. Carter MC, Clayton ST, Komarow MD, et al. Assessment of clinical findings, tryptase levels and bone marrow histopathology in the management of pediatric mastocytosis. J Allergy Clin

A 2-year-old girl with Fitzpatrick skin type VI who had recently emigrated from Djibouti presented to our dermatology clinic for a rash that appeared when she was 2 months old. The lesions occasionally were pruritic after sun exposure or after crawling outside. There was no associated abdominal pain, diarrhea, flushing, or hypotension. Topical moisturizers were not helpful.

The patient had no known allergies or other notable medical history. Physical examination revealed multiple hyperpigmented, oval-shaped, slightly raised papules and plaques on her torso (FIGURE 1), neck, and arms, and fewer lesions on her face and legs. Darier sign was not appreciated on the initial consult. A 4-mm punch biopsy of the patient’s right middle back was performed at this visit.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Mastocytosis

The presence of a hyperpigmented skin lesion that becomes pruritic, raised, and erythematous when rubbed (Darier sign) is the major criterion for the diagnosis of cutaneous mastocytosis.1 Minor criteria include a skin biopsy demonstrating a 4- to 8-fold increase in the number of mast cells within the papillary dermis and the presence of cKIT mutations.1 In this case, the patient’s punch biopsy results came back positive for clonal mast cell infiltration of the papillary dermis (FIGURES 2A and 2B), and her physician elicited a slightly positive Darier sign during a follow-up visit.

Mastocytosis is characterized by pathognomonic proliferation of clonal mast cells with either cutaneous or systemic involvement.1 Mast cell expansion most commonly is found in the skin and bone marrow; however, involvement of the gastrointestinal tract, liver, spleen, and lymph nodes also has been documented.1 Nonhereditary somatic mutations of the cKIT gene have been observed in many studies and may be associated with increased proliferation of clonal mast cells.2

A review of the English-language literature on cutaneous mastocytosis reveals a paucity of reports in darker skin types. However, it is important for clinicians to be able to recognize this disease in all skin types.

Three subcategories. Cutaneous mastocytosis is divided into 3 subcategories: mastocytoma of the skin (1–3 solitary skin lesions), maculopapular cutaneous mastocytosis, also known as urticaria pigmentosa (as seen in our patient; usually ≥ 4 lesions); and diffuse cutaneous mastocytosis (confluent lesions; leathery appearance of skin).1,3,4 Maculopapular cutaneous mastocytosis, which our patient had, classically develops within the first 6 months of life and presents as hyperpigmented macules and papules.

Keep in mind that systemic involvement in cutaneous mastocytosis occasionally occurs and can be associated with anaphylaxis, flushing, headache, dyspnea, nausea, emesis, diarrhea, abdominal pain, and hepatosplenomegaly.2

Continue to: Narrowing down a broad differential diagnosis

Narrowing down a broad differential diagnosis

Our cas a ase was made somewhat challenging by the patient’s darkly pigmented skin color, which made any erythema and other cutaneous signs less visible. The differential was broad and included postinflammatory hyperpigmentation from eczema, multiple congenital nevi, sarcoidosis, leprosy, and cutaneous tuberculosis, all of which can be eliminated by performing a biopsy of the lesion.

Diagnostic criteria include biopsy and laboratory findings

In addition to a skin biopsy, initial assessment in cases of suspected cutaneous mastocytosis should include a complete blood cell count with differential, liver function tests (+/- liver ultrasound), a serum tryptase level, and a peripheral smear. Serum tryptase levels > 20 ng/mL have been shown to correlate with a higher probability of systemic mastocytosis. Higher tryptase levels also correlate with severity of disease in children.5

Treatment focuses on minimizing mast cell degranulation

Due to the relatively benign course of cutaneous mastocytosis, the mainstay of treatment is focused on minimizing mast cell degranulation to control subsequent symptoms. Avoiding precipitating factors such as temperature extremes, external stimulation of lesions, dry skin, infection, and certain medications (eg, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, aspirin, morphine, polymyxin B sulphate, anticholinergics, some systemic anesthetics) that can stimulate mast cell degranulation is encouraged.2 H1 and H2 antihistamines are the first-line treatment for mild to moderate symptoms. In refractory cases, leukotriene receptor antagonists or oral cromolyn sodium may be considered.2

Regular follow-up every 6 to 12 months should be established after diagnosis.1 If symptoms persist into adulthood or concern for disease progression is high, a bone marrow biopsy is recommended.1

Our patient

Our patient’s laboratory results revealed a normal serum tryptase level (3.4 ng/mL; reference range < 11.5 ng/mL) and complete blood cell count. A complete metabolic panel demonstrated elevated and high-normal liver function tests with alanine aminotransferase (ALT) at 111 u/L (reference range, 10–40 u/L) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) at 55 u/L (reference range, 7–56 u/L).

Continue to: As a precaution...

As a precaution and for consideration of further work-up, such as the need for a liver ultrasound, the patient was referred to Pediatric Gastroenterology. The specialist repeated the liver function tests, the results of which were lower (ALT, 42 u/L; AST, 24 u/L); a liver ultrasound was thought to be unnecessary.

Our patient’s otherwise negative review of systems led the specialist to feel confident that no systemic disease was present at the time. These results were discussed with the patient’s parents and counseling about trigger avoidance was provided. The patient was given pediatric-dosed oral and topical H1 antihistamines for symptom relief.

CORRESPONDENCE

Joshua D. Sparling, MD, 6 E Chestnut Street, Ste 340, Augusta, ME 04330; Joshua.Sparling@MaineGeneral.org

A 2-year-old girl with Fitzpatrick skin type VI who had recently emigrated from Djibouti presented to our dermatology clinic for a rash that appeared when she was 2 months old. The lesions occasionally were pruritic after sun exposure or after crawling outside. There was no associated abdominal pain, diarrhea, flushing, or hypotension. Topical moisturizers were not helpful.

The patient had no known allergies or other notable medical history. Physical examination revealed multiple hyperpigmented, oval-shaped, slightly raised papules and plaques on her torso (FIGURE 1), neck, and arms, and fewer lesions on her face and legs. Darier sign was not appreciated on the initial consult. A 4-mm punch biopsy of the patient’s right middle back was performed at this visit.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Mastocytosis

The presence of a hyperpigmented skin lesion that becomes pruritic, raised, and erythematous when rubbed (Darier sign) is the major criterion for the diagnosis of cutaneous mastocytosis.1 Minor criteria include a skin biopsy demonstrating a 4- to 8-fold increase in the number of mast cells within the papillary dermis and the presence of cKIT mutations.1 In this case, the patient’s punch biopsy results came back positive for clonal mast cell infiltration of the papillary dermis (FIGURES 2A and 2B), and her physician elicited a slightly positive Darier sign during a follow-up visit.

Mastocytosis is characterized by pathognomonic proliferation of clonal mast cells with either cutaneous or systemic involvement.1 Mast cell expansion most commonly is found in the skin and bone marrow; however, involvement of the gastrointestinal tract, liver, spleen, and lymph nodes also has been documented.1 Nonhereditary somatic mutations of the cKIT gene have been observed in many studies and may be associated with increased proliferation of clonal mast cells.2

A review of the English-language literature on cutaneous mastocytosis reveals a paucity of reports in darker skin types. However, it is important for clinicians to be able to recognize this disease in all skin types.

Three subcategories. Cutaneous mastocytosis is divided into 3 subcategories: mastocytoma of the skin (1–3 solitary skin lesions), maculopapular cutaneous mastocytosis, also known as urticaria pigmentosa (as seen in our patient; usually ≥ 4 lesions); and diffuse cutaneous mastocytosis (confluent lesions; leathery appearance of skin).1,3,4 Maculopapular cutaneous mastocytosis, which our patient had, classically develops within the first 6 months of life and presents as hyperpigmented macules and papules.

Keep in mind that systemic involvement in cutaneous mastocytosis occasionally occurs and can be associated with anaphylaxis, flushing, headache, dyspnea, nausea, emesis, diarrhea, abdominal pain, and hepatosplenomegaly.2

Continue to: Narrowing down a broad differential diagnosis

Narrowing down a broad differential diagnosis

Our cas a ase was made somewhat challenging by the patient’s darkly pigmented skin color, which made any erythema and other cutaneous signs less visible. The differential was broad and included postinflammatory hyperpigmentation from eczema, multiple congenital nevi, sarcoidosis, leprosy, and cutaneous tuberculosis, all of which can be eliminated by performing a biopsy of the lesion.

Diagnostic criteria include biopsy and laboratory findings

In addition to a skin biopsy, initial assessment in cases of suspected cutaneous mastocytosis should include a complete blood cell count with differential, liver function tests (+/- liver ultrasound), a serum tryptase level, and a peripheral smear. Serum tryptase levels > 20 ng/mL have been shown to correlate with a higher probability of systemic mastocytosis. Higher tryptase levels also correlate with severity of disease in children.5

Treatment focuses on minimizing mast cell degranulation

Due to the relatively benign course of cutaneous mastocytosis, the mainstay of treatment is focused on minimizing mast cell degranulation to control subsequent symptoms. Avoiding precipitating factors such as temperature extremes, external stimulation of lesions, dry skin, infection, and certain medications (eg, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, aspirin, morphine, polymyxin B sulphate, anticholinergics, some systemic anesthetics) that can stimulate mast cell degranulation is encouraged.2 H1 and H2 antihistamines are the first-line treatment for mild to moderate symptoms. In refractory cases, leukotriene receptor antagonists or oral cromolyn sodium may be considered.2

Regular follow-up every 6 to 12 months should be established after diagnosis.1 If symptoms persist into adulthood or concern for disease progression is high, a bone marrow biopsy is recommended.1

Our patient

Our patient’s laboratory results revealed a normal serum tryptase level (3.4 ng/mL; reference range < 11.5 ng/mL) and complete blood cell count. A complete metabolic panel demonstrated elevated and high-normal liver function tests with alanine aminotransferase (ALT) at 111 u/L (reference range, 10–40 u/L) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) at 55 u/L (reference range, 7–56 u/L).

Continue to: As a precaution...

As a precaution and for consideration of further work-up, such as the need for a liver ultrasound, the patient was referred to Pediatric Gastroenterology. The specialist repeated the liver function tests, the results of which were lower (ALT, 42 u/L; AST, 24 u/L); a liver ultrasound was thought to be unnecessary.

Our patient’s otherwise negative review of systems led the specialist to feel confident that no systemic disease was present at the time. These results were discussed with the patient’s parents and counseling about trigger avoidance was provided. The patient was given pediatric-dosed oral and topical H1 antihistamines for symptom relief.

CORRESPONDENCE

Joshua D. Sparling, MD, 6 E Chestnut Street, Ste 340, Augusta, ME 04330; Joshua.Sparling@MaineGeneral.org

1. Hartmann K, Escribano L, Grattan C, et al . Cutaneous manifestations in patients with mastocytosis: consensus report of the European Competence Network on Mastocytosis; the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology; and the European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137:35-45.

2. Abid A, Malone MA, Curci K. Mastocytosis. Prim Care. 2016;43:505-518.

3. Forster A, Hartmann K, Horny HP, et al. Large maculopapular cutaneous lesions are associated with favourable outcome in childhood-onset mastocytosis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136:1581-1590.

4. Tharp MD, Sofen BD. Mastocytosis. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. China: Elsevier; 2018:2103-2104.

5. Carter MC, Clayton ST, Komarow MD, et al. Assessment of clinical findings, tryptase levels and bone marrow histopathology in the management of pediatric mastocytosis. J Allergy Clin

1. Hartmann K, Escribano L, Grattan C, et al . Cutaneous manifestations in patients with mastocytosis: consensus report of the European Competence Network on Mastocytosis; the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology; and the European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137:35-45.

2. Abid A, Malone MA, Curci K. Mastocytosis. Prim Care. 2016;43:505-518.

3. Forster A, Hartmann K, Horny HP, et al. Large maculopapular cutaneous lesions are associated with favourable outcome in childhood-onset mastocytosis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136:1581-1590.

4. Tharp MD, Sofen BD. Mastocytosis. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. China: Elsevier; 2018:2103-2104.

5. Carter MC, Clayton ST, Komarow MD, et al. Assessment of clinical findings, tryptase levels and bone marrow histopathology in the management of pediatric mastocytosis. J Allergy Clin